User login

Hep C, HIV coinfection tied to higher MI risk with age

, a new analysis suggests.

By contrast, the risk increases by 30% every 10 years among PWH without HCV infection.

“There is other evidence that suggests people with HIV and HCV have a greater burden of negative health outcomes,” senior author Keri N. Althoff, PhD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, said in an interview. “But the magnitude of ‘greater’ was bigger than I expected.”

“Understanding the difference HCV can make in the risk of MI with increasing age among those with – compared to without – HCV is an important step for understanding additional potential benefits of HCV treatment (among PWH),” she said.

The amplified risk with age occurred even though, overall, the association between HCV coinfection and increased risk of type 1 myocardial infarction (T1MI) was not significant, the analysis showed.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

How age counts

Dr. Althoff and colleagues analyzed data from 23,361 PWH aged 40-79 who had initiated antiretroviral therapy between 2000 and 2017. The primary outcome was T1MI.

A total of 4,677 participants (20%) had HCV. Eighty-nine T1MIs occurred among PWH with HCV (1.9%) vs. 314 among PWH without HCV (1.7%). In adjusted analyses, HCV was not associated with increased T1MI risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.98).

However, the risk of T1MI increased with age and was augmented in those with HCV (aHR per 10-year increase in age, 1.85) vs. those without HCV (aHR, 1.30).

Specifically, compared with those without HCV, the estimated T1MI risk was 17% higher among 50- to 59-year-olds with HCV and 77% higher among those 60 and older; neither association was statistically significant, although the authors suggest this probably was because of the smaller number of participants in the older age categories.

Even without HCV, the risk of T1MI increased in participants who had traditional risk factors. The risk was significantly higher among PWH aged 40-49 with diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, protease inhibitor (PI) use, and smoking, whereas among PWH aged 50-59, the T1MI risk was significantly greater among those with hypertension, PI use, and smoking.

Among those aged 60 or older, hypertension and low CD4 counts were associated with a significantly increased T1MI risk.

“Clinicians providing health care to people with HIV should know their patients’ HCV status,” Dr. Althoff said, “and provide support regarding HCV treatment and ways to reduce their cardiovascular risk, including smoking cessation, reaching and maintaining a healthy BMI, and substance use treatment.”

Truly additive?

American Heart Association expert volunteer Nieca Goldberg, MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine at New York University and medical director of Atria NY, said the increased T1MI risk with coinfection “makes sense” because both HIV and HCV are linked to inflammation.

However, she said in an interview, “the fact that the authors didn’t control for other, more traditional heart attack risk factors is a limitation. I would like to see a study that takes other risk factors into consideration to see if HCV is truly additive.”

Meanwhile, like Dr. Althoff, she said, “Clinicians should be taking a careful history that includes chronic infections as well as traditional heart risk factors.”

Additional studies are needed, Dr. Althoff agreed. “There are two paths we are keenly interested in pursuing. The first is understanding how metabolic risk factors for MI change after HCV treatment. We are working on this.”

“Ultimately,” she said, “we want to compare MI risk in people with HIV who had successful HCV treatment to those who have not had successful HCV treatment.”

In their current study, they had nearly 2 decades of follow-up, she noted. “Although we don’t need to wait that long, we would like to have close to a decade of potential follow-up time (since 2016, when sofosbuvir/velpatasvir became available) so that we have a large enough sample size to observe a sufficient number of MIs within the first 5 years after successful HCV treatment.”

No commercial funding or relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new analysis suggests.

By contrast, the risk increases by 30% every 10 years among PWH without HCV infection.

“There is other evidence that suggests people with HIV and HCV have a greater burden of negative health outcomes,” senior author Keri N. Althoff, PhD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, said in an interview. “But the magnitude of ‘greater’ was bigger than I expected.”

“Understanding the difference HCV can make in the risk of MI with increasing age among those with – compared to without – HCV is an important step for understanding additional potential benefits of HCV treatment (among PWH),” she said.

The amplified risk with age occurred even though, overall, the association between HCV coinfection and increased risk of type 1 myocardial infarction (T1MI) was not significant, the analysis showed.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

How age counts

Dr. Althoff and colleagues analyzed data from 23,361 PWH aged 40-79 who had initiated antiretroviral therapy between 2000 and 2017. The primary outcome was T1MI.

A total of 4,677 participants (20%) had HCV. Eighty-nine T1MIs occurred among PWH with HCV (1.9%) vs. 314 among PWH without HCV (1.7%). In adjusted analyses, HCV was not associated with increased T1MI risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.98).

However, the risk of T1MI increased with age and was augmented in those with HCV (aHR per 10-year increase in age, 1.85) vs. those without HCV (aHR, 1.30).

Specifically, compared with those without HCV, the estimated T1MI risk was 17% higher among 50- to 59-year-olds with HCV and 77% higher among those 60 and older; neither association was statistically significant, although the authors suggest this probably was because of the smaller number of participants in the older age categories.

Even without HCV, the risk of T1MI increased in participants who had traditional risk factors. The risk was significantly higher among PWH aged 40-49 with diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, protease inhibitor (PI) use, and smoking, whereas among PWH aged 50-59, the T1MI risk was significantly greater among those with hypertension, PI use, and smoking.

Among those aged 60 or older, hypertension and low CD4 counts were associated with a significantly increased T1MI risk.

“Clinicians providing health care to people with HIV should know their patients’ HCV status,” Dr. Althoff said, “and provide support regarding HCV treatment and ways to reduce their cardiovascular risk, including smoking cessation, reaching and maintaining a healthy BMI, and substance use treatment.”

Truly additive?

American Heart Association expert volunteer Nieca Goldberg, MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine at New York University and medical director of Atria NY, said the increased T1MI risk with coinfection “makes sense” because both HIV and HCV are linked to inflammation.

However, she said in an interview, “the fact that the authors didn’t control for other, more traditional heart attack risk factors is a limitation. I would like to see a study that takes other risk factors into consideration to see if HCV is truly additive.”

Meanwhile, like Dr. Althoff, she said, “Clinicians should be taking a careful history that includes chronic infections as well as traditional heart risk factors.”

Additional studies are needed, Dr. Althoff agreed. “There are two paths we are keenly interested in pursuing. The first is understanding how metabolic risk factors for MI change after HCV treatment. We are working on this.”

“Ultimately,” she said, “we want to compare MI risk in people with HIV who had successful HCV treatment to those who have not had successful HCV treatment.”

In their current study, they had nearly 2 decades of follow-up, she noted. “Although we don’t need to wait that long, we would like to have close to a decade of potential follow-up time (since 2016, when sofosbuvir/velpatasvir became available) so that we have a large enough sample size to observe a sufficient number of MIs within the first 5 years after successful HCV treatment.”

No commercial funding or relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new analysis suggests.

By contrast, the risk increases by 30% every 10 years among PWH without HCV infection.

“There is other evidence that suggests people with HIV and HCV have a greater burden of negative health outcomes,” senior author Keri N. Althoff, PhD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, said in an interview. “But the magnitude of ‘greater’ was bigger than I expected.”

“Understanding the difference HCV can make in the risk of MI with increasing age among those with – compared to without – HCV is an important step for understanding additional potential benefits of HCV treatment (among PWH),” she said.

The amplified risk with age occurred even though, overall, the association between HCV coinfection and increased risk of type 1 myocardial infarction (T1MI) was not significant, the analysis showed.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

How age counts

Dr. Althoff and colleagues analyzed data from 23,361 PWH aged 40-79 who had initiated antiretroviral therapy between 2000 and 2017. The primary outcome was T1MI.

A total of 4,677 participants (20%) had HCV. Eighty-nine T1MIs occurred among PWH with HCV (1.9%) vs. 314 among PWH without HCV (1.7%). In adjusted analyses, HCV was not associated with increased T1MI risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.98).

However, the risk of T1MI increased with age and was augmented in those with HCV (aHR per 10-year increase in age, 1.85) vs. those without HCV (aHR, 1.30).

Specifically, compared with those without HCV, the estimated T1MI risk was 17% higher among 50- to 59-year-olds with HCV and 77% higher among those 60 and older; neither association was statistically significant, although the authors suggest this probably was because of the smaller number of participants in the older age categories.

Even without HCV, the risk of T1MI increased in participants who had traditional risk factors. The risk was significantly higher among PWH aged 40-49 with diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, protease inhibitor (PI) use, and smoking, whereas among PWH aged 50-59, the T1MI risk was significantly greater among those with hypertension, PI use, and smoking.

Among those aged 60 or older, hypertension and low CD4 counts were associated with a significantly increased T1MI risk.

“Clinicians providing health care to people with HIV should know their patients’ HCV status,” Dr. Althoff said, “and provide support regarding HCV treatment and ways to reduce their cardiovascular risk, including smoking cessation, reaching and maintaining a healthy BMI, and substance use treatment.”

Truly additive?

American Heart Association expert volunteer Nieca Goldberg, MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine at New York University and medical director of Atria NY, said the increased T1MI risk with coinfection “makes sense” because both HIV and HCV are linked to inflammation.

However, she said in an interview, “the fact that the authors didn’t control for other, more traditional heart attack risk factors is a limitation. I would like to see a study that takes other risk factors into consideration to see if HCV is truly additive.”

Meanwhile, like Dr. Althoff, she said, “Clinicians should be taking a careful history that includes chronic infections as well as traditional heart risk factors.”

Additional studies are needed, Dr. Althoff agreed. “There are two paths we are keenly interested in pursuing. The first is understanding how metabolic risk factors for MI change after HCV treatment. We are working on this.”

“Ultimately,” she said, “we want to compare MI risk in people with HIV who had successful HCV treatment to those who have not had successful HCV treatment.”

In their current study, they had nearly 2 decades of follow-up, she noted. “Although we don’t need to wait that long, we would like to have close to a decade of potential follow-up time (since 2016, when sofosbuvir/velpatasvir became available) so that we have a large enough sample size to observe a sufficient number of MIs within the first 5 years after successful HCV treatment.”

No commercial funding or relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

New liver stiffness thresholds refine NASH risk stratification

New liver stiffness (LS) thresholds offer accurate prediction of disease progression and clinical outcomes in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis, according to investigators.

These new LS thresholds are more reliable because they are based on high-quality prospective data drawn from four randomized controlled trials, reported lead author Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

“Retrospective studies report that increasing baseline LS by VCTE [vibration-controlled transient elastography] is associated with the risk of disease progression in patients with NAFLD [non-alcoholic fatty liver disease], but prospective data in well-characterized NASH cohorts with biopsy-confirmed advanced fibrosis are limited,” the investigators wrote in Gut. “The optimal LS thresholds for prognostication of fibrosis progression and decompensation are unknown.”

Seeking clarity, Dr. Loomba and colleagues leveraged data from two phase 3 placebo-controlled trials for selonsertib and two phase 2b placebo-controlled trials for simtuzumab.

“While the studies were discontinued prematurely due to lack of efficacy, the prospectively collected data in these well-characterized participants with serial liver biopsies provides a unique opportunity to study the association between baseline LS by VCTE and disease progression,” the investigators wrote.

Across all four studies, bridging fibrosis (F3) was present in 664 participants, while 734 individuals had cirrhosis (F4). In the selonsertib studies, fibrosis was staged at baseline and week 48. The simtuzumab studies measured liver fibrosis at baseline and week 96. Out of the 664 participants with bridging fibrosis, 103 (16%) progressed to cirrhosis. Among the 734 patients with cirrhosis, 27 (4%) experienced liver-related events. Comparing these outcomes with LS data at baseline and throughout the study revealed optimal LS thresholds.

The best threshold for predicting progression from bridging fibrosis to cirrhosis was 16.6 kPa. According to the authors, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of this threshold for progression to cirrhosis were 58%, 76%, 31%, and 91%, respectively. Among patients at or above 16.6 kPa, 31% progressed to cirrhosis, compared with 9.1% of those under that threshold. Furthermore, individuals with a baseline LS at or above 16.6 kPa had nearly four times greater risk of developing cirrhosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.99; 95% CI, 2.66-5.98; P < .0001).

For patients with cirrhosis at baseline, the optimal threshold for predicting liver-related events, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and portal hypertension–related GI bleeding, liver transplantation, or mortality, was 30.7 kPa. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of this threshold for liver-related events were 62%, 87%, 10%, and 99%, respectively, according to the authors. Patients with an LS above this mark were 10 times as likely to experience liver-related events (aHR, 10.13; 95% CI, 4.38-23.41; P < .0001).

Scott L. Friedman, MD, chief of the division of liver diseases and dean for Therapeutic Discovery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, called the study “an important effort” that offers valuable insights for both researchers and practitioners.

“For clinical trials, [these thresholds] really allow for greater refinement or enrichment of patients who are suitable for enrollment in the trial because they’re at a higher risk of clinical problems that might be mitigated if the drug is effective,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “For clinical practice, it might indicate that the patient should either be fast tracked for a clinical trial or, more importantly, maybe needs to be referred for evaluation for a liver transplant. It may also indicate – although they didn’t look at it in this study – that there’s a need to begin or accelerate screening for liver cancer, which becomes an encroaching risk as the fibrosis advances to later stages.”

The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Amgen, Eli Lilly, CohBar, and others. Dr. Friedman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

New liver stiffness (LS) thresholds offer accurate prediction of disease progression and clinical outcomes in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis, according to investigators.

These new LS thresholds are more reliable because they are based on high-quality prospective data drawn from four randomized controlled trials, reported lead author Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

“Retrospective studies report that increasing baseline LS by VCTE [vibration-controlled transient elastography] is associated with the risk of disease progression in patients with NAFLD [non-alcoholic fatty liver disease], but prospective data in well-characterized NASH cohorts with biopsy-confirmed advanced fibrosis are limited,” the investigators wrote in Gut. “The optimal LS thresholds for prognostication of fibrosis progression and decompensation are unknown.”

Seeking clarity, Dr. Loomba and colleagues leveraged data from two phase 3 placebo-controlled trials for selonsertib and two phase 2b placebo-controlled trials for simtuzumab.

“While the studies were discontinued prematurely due to lack of efficacy, the prospectively collected data in these well-characterized participants with serial liver biopsies provides a unique opportunity to study the association between baseline LS by VCTE and disease progression,” the investigators wrote.

Across all four studies, bridging fibrosis (F3) was present in 664 participants, while 734 individuals had cirrhosis (F4). In the selonsertib studies, fibrosis was staged at baseline and week 48. The simtuzumab studies measured liver fibrosis at baseline and week 96. Out of the 664 participants with bridging fibrosis, 103 (16%) progressed to cirrhosis. Among the 734 patients with cirrhosis, 27 (4%) experienced liver-related events. Comparing these outcomes with LS data at baseline and throughout the study revealed optimal LS thresholds.

The best threshold for predicting progression from bridging fibrosis to cirrhosis was 16.6 kPa. According to the authors, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of this threshold for progression to cirrhosis were 58%, 76%, 31%, and 91%, respectively. Among patients at or above 16.6 kPa, 31% progressed to cirrhosis, compared with 9.1% of those under that threshold. Furthermore, individuals with a baseline LS at or above 16.6 kPa had nearly four times greater risk of developing cirrhosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.99; 95% CI, 2.66-5.98; P < .0001).

For patients with cirrhosis at baseline, the optimal threshold for predicting liver-related events, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and portal hypertension–related GI bleeding, liver transplantation, or mortality, was 30.7 kPa. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of this threshold for liver-related events were 62%, 87%, 10%, and 99%, respectively, according to the authors. Patients with an LS above this mark were 10 times as likely to experience liver-related events (aHR, 10.13; 95% CI, 4.38-23.41; P < .0001).

Scott L. Friedman, MD, chief of the division of liver diseases and dean for Therapeutic Discovery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, called the study “an important effort” that offers valuable insights for both researchers and practitioners.

“For clinical trials, [these thresholds] really allow for greater refinement or enrichment of patients who are suitable for enrollment in the trial because they’re at a higher risk of clinical problems that might be mitigated if the drug is effective,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “For clinical practice, it might indicate that the patient should either be fast tracked for a clinical trial or, more importantly, maybe needs to be referred for evaluation for a liver transplant. It may also indicate – although they didn’t look at it in this study – that there’s a need to begin or accelerate screening for liver cancer, which becomes an encroaching risk as the fibrosis advances to later stages.”

The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Amgen, Eli Lilly, CohBar, and others. Dr. Friedman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

New liver stiffness (LS) thresholds offer accurate prediction of disease progression and clinical outcomes in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis, according to investigators.

These new LS thresholds are more reliable because they are based on high-quality prospective data drawn from four randomized controlled trials, reported lead author Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

“Retrospective studies report that increasing baseline LS by VCTE [vibration-controlled transient elastography] is associated with the risk of disease progression in patients with NAFLD [non-alcoholic fatty liver disease], but prospective data in well-characterized NASH cohorts with biopsy-confirmed advanced fibrosis are limited,” the investigators wrote in Gut. “The optimal LS thresholds for prognostication of fibrosis progression and decompensation are unknown.”

Seeking clarity, Dr. Loomba and colleagues leveraged data from two phase 3 placebo-controlled trials for selonsertib and two phase 2b placebo-controlled trials for simtuzumab.

“While the studies were discontinued prematurely due to lack of efficacy, the prospectively collected data in these well-characterized participants with serial liver biopsies provides a unique opportunity to study the association between baseline LS by VCTE and disease progression,” the investigators wrote.

Across all four studies, bridging fibrosis (F3) was present in 664 participants, while 734 individuals had cirrhosis (F4). In the selonsertib studies, fibrosis was staged at baseline and week 48. The simtuzumab studies measured liver fibrosis at baseline and week 96. Out of the 664 participants with bridging fibrosis, 103 (16%) progressed to cirrhosis. Among the 734 patients with cirrhosis, 27 (4%) experienced liver-related events. Comparing these outcomes with LS data at baseline and throughout the study revealed optimal LS thresholds.

The best threshold for predicting progression from bridging fibrosis to cirrhosis was 16.6 kPa. According to the authors, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of this threshold for progression to cirrhosis were 58%, 76%, 31%, and 91%, respectively. Among patients at or above 16.6 kPa, 31% progressed to cirrhosis, compared with 9.1% of those under that threshold. Furthermore, individuals with a baseline LS at or above 16.6 kPa had nearly four times greater risk of developing cirrhosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.99; 95% CI, 2.66-5.98; P < .0001).

For patients with cirrhosis at baseline, the optimal threshold for predicting liver-related events, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and portal hypertension–related GI bleeding, liver transplantation, or mortality, was 30.7 kPa. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of this threshold for liver-related events were 62%, 87%, 10%, and 99%, respectively, according to the authors. Patients with an LS above this mark were 10 times as likely to experience liver-related events (aHR, 10.13; 95% CI, 4.38-23.41; P < .0001).

Scott L. Friedman, MD, chief of the division of liver diseases and dean for Therapeutic Discovery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, called the study “an important effort” that offers valuable insights for both researchers and practitioners.

“For clinical trials, [these thresholds] really allow for greater refinement or enrichment of patients who are suitable for enrollment in the trial because they’re at a higher risk of clinical problems that might be mitigated if the drug is effective,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “For clinical practice, it might indicate that the patient should either be fast tracked for a clinical trial or, more importantly, maybe needs to be referred for evaluation for a liver transplant. It may also indicate – although they didn’t look at it in this study – that there’s a need to begin or accelerate screening for liver cancer, which becomes an encroaching risk as the fibrosis advances to later stages.”

The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Amgen, Eli Lilly, CohBar, and others. Dr. Friedman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM GUT

What barriers delay treatment in patients with hepatitis C?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Race, gender, and other factors are associated with lack of HCV Tx

A retrospective study (N = 894) assessed factors associated with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) initiation.1 Patients who were HCV+ with at least 1 clinical visit during the study period completed a survey of psychological, behavioral, and social life assessments. The final cohort (57% male; 64% ≥ 61 years old) was divided into patients who initiated DAA treatment (n = 690) and those who did not (n = 204).

In an adjusted multivariable analysis, factors associated with lower odds of DAA initiation included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.59 vs White race; 95% CI, 0.36-0.98); perceived difficulty accessing medical care (aOR = 0.48 vs no difficulty; 95% CI, 0.27-0.83); recent intravenous (IV) drug use (aOR = 0.11 vs no use; 95% CI, 0.02-0.54); alcohol use disorder (AUD; aOR = 0.58 vs no AUD; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90); severe depression (aOR = 0.42 vs no depression; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9); recent homelessness (aOR = 0.36 vs no homelessness; 95% CI, 0.14-0.94); and recent incarceration (aOR = 0.34 vs no incarceration; 95% CI, 0.12-0.94).1

A multicenter, observational prospective cohort study (N = 3075) evaluated receipt of HCV treatment for patients co-infected with HCV and HIV.2 The primary outcome was initiation of HCV treatment with DAAs; 1957 patients initiated therapy, while 1118 did not. Significant independent risk factors for noninitiation of treatment included age younger than 50 years, a history of IV drug use, and use of opioid substitution therapy (OST). Other factors included psychiatric comorbidity (odds ratio [OR] = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.27-0.75), incarceration (OR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.43-0.87), and female gender (OR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98). In a multivariate analysis limited to those with a history of IV drug use, both use of OST (aOR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and recent IV drug use (aOR = 0.019; 95% CI, 0.004-0.087) were identified as factors with low odds of treatment implementation.2

A retrospective cohort study (N = 1024) of medical charts examined the barriers to treatment in adults with chronic HCV infection.3 Of the patient population, 208 were treated and 816 were untreated. Patients not receiving DAAs were associated with poor adherence to/loss to follow-up (n = 548; OR = 36.6; 95% CI, 19.6-68.4); significant psychiatric illness (n = 103; OR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.13-3.71); and coinfection with HIV (n = 188; OR = 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5-8.2).3

A German multicenter retrospective case-control study (N = 793) identified factors in patient and physician decisions to initiate treatment for HCV.4 Patients were ≥ 18 years old, confirmed to be HCV+, and had visited their physician at least 1 time during the observation period. A total of 573 patients received treatment and 220 did not. Patients and clinicians of those who chose not to receive treatment completed a survey that collected reasons for not treating. The most prevalent reason for not initiating treatment was patient wish (42%). This was further delineated to reveal that 17.3% attributed their decision to fear of treatment and 13.2% to fear of adverse events. Other factors associated with nontreatment included IV drug use (aOR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.16-0.62); HIV coinfection (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.40); and use of OST (aOR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68). Patient demographics associated with wish not to be treated included older age (20.2% of those ≥ 40 years old vs 6.4% of those < 40 years old; P = .03) and female gender (51.0% of females vs 35.2% of males; P = .019).4

An analysis of a French insurance database (N = 22,545) evaluated the incidence of HCV treatment with DAAs in patients who inject drugs (PWID) with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD).5 All participants (78% male; median age, 49 years) were chronically HCV-infected and covered by national health insurance. Individuals were grouped by AUD status: untreated (n = 5176), treated (n = 3020), and no AUD (n = 14349). After multivariate adjustment, those with untreated AUD had lower uptake of DAAs than those who did not have AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.94) and those with treated AUD (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.94). There were no differences between those with treated AUD and those who did not have AUD. Other factors associated with lower DAA uptake were access to care (aHR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-0.98) and female gender (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.9).5

A 2017 retrospective cohort study evaluated predictors and barriers to follow-up and treatment with DAAs among veterans who were HCV+.6 Patients (94% > 50 years old; 97% male; 48% white) had established HCV care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system. Of those who followed up with at least 1 visit to an HCV specialty clinic (n = 47,165), 29% received DAAs. Factors associated with lack of treatment included race (Black vs White: OR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82; Hispanic vs White: OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97); IV drug use (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80-0.88); AUD (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70-0.77); medical comorbidities (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.66-0.77); and hepatocellular carcinoma (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).6

Continue to: Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

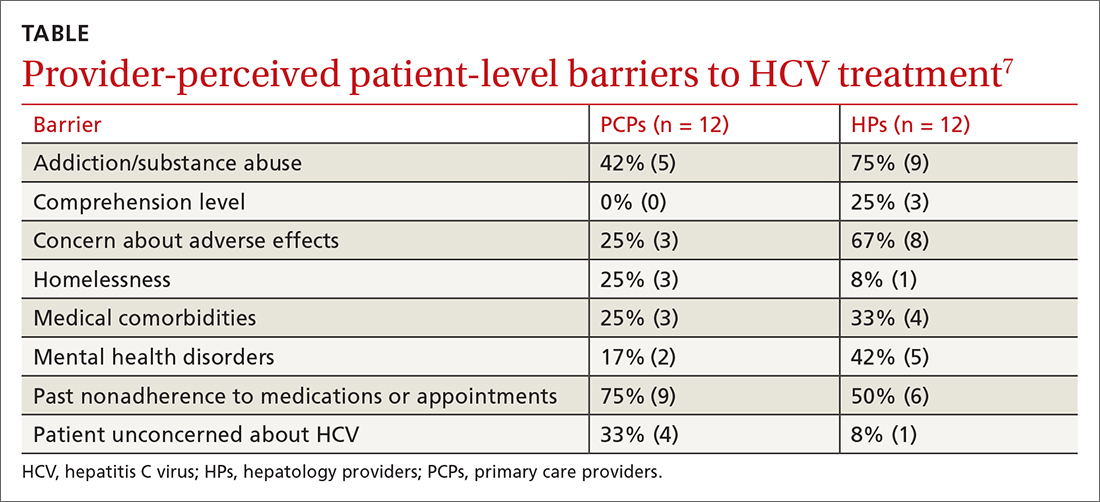

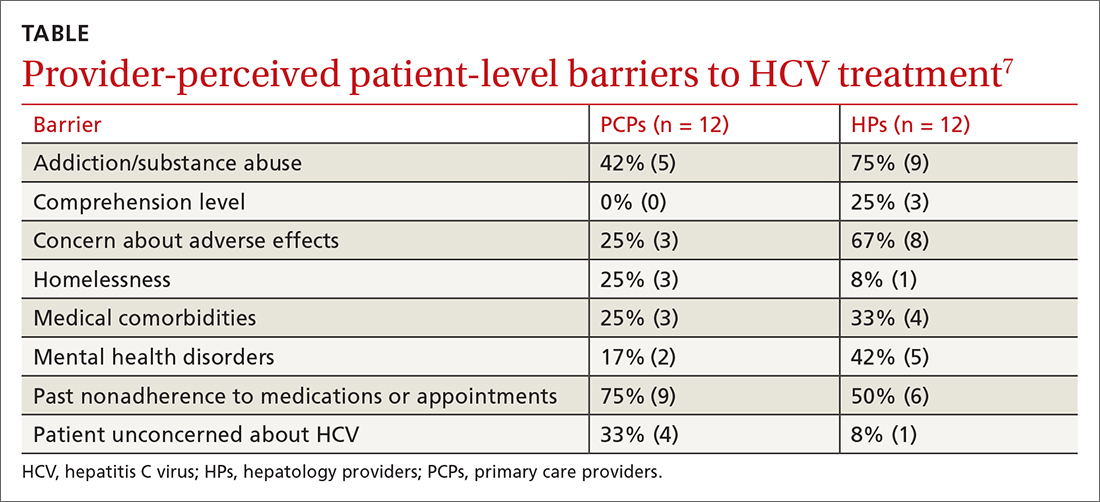

Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

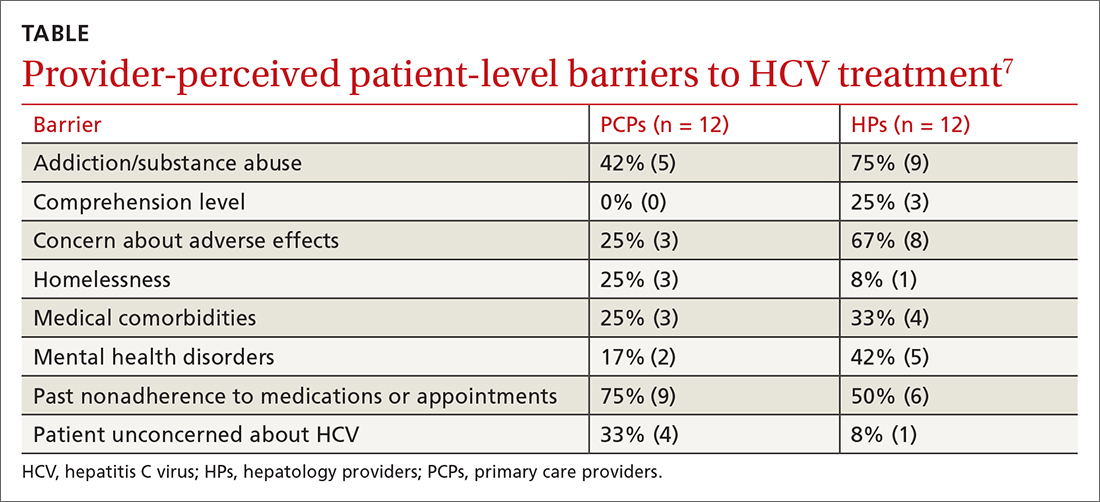

A 2017 prospective qualitative study (N = 24) from a Veterans Affairs health care system analyzed provider-perceived barriers to initiation of and adherence to HCV treatment.7 The analysis focused on differences by provider specialty. Primary care providers (PCPs; n = 12; 17% with > 40 patients with HCV) and hepatology providers (HPs; n = 12; 83% with > 40 patients with HCV) participated in a semi-structured telephone-based interview, providing their perceptions of patient-level barriers to HCV treatment. Eight patient-level barrier themes were identified; these are outlined in the TABLE7 along with data for both PCPs and HPs.

Editor’s takeaway

These 7 cohort studies show us the factors we consider and the reasons we give to not initiate HCV treatment. Some of the factors seem reasonable, but many do not. We might use this list to remind and challenge ourselves to work through barriers to provide the best possible treatment.

1. Spradling PR, Zhong Y, Moorman AC, et al. Psychosocial obstacles to hepatitis C treatment initiation among patients in care: a hitch in the cascade of cure. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:400-411. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1632

2. Rivero-Juarez A, Tellez F, Castano-Carracedo M, et al. Parenteral drug use as the main barrier to hepatitis C treatment uptake in HIV-infected patients. HIV Medicine. 2019;20:359-367. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12715

3. Al-Khazraji A, Patel I, Saleh M, et al. Identifying barriers to the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis. 2020;38:46-52. doi: 10.1159/000501821

4. Buggisch P, Heiken H, Mauss S, et al. Barriers to initiation of hepatitis C virus therapy in Germany: a retrospective, case-controlled study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:3p250833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250833

5. Barré T, Marcellin F, Di Beo V, et al. Untreated alcohol use disorder in people who inject drugs (PWID) in France: a major barrier to HCV treatment uptake (the ANRS-FANTASIO study). Addiction. 2019;115:573-582. doi: 10.1111/add.14820

6. Lin M, Kramer J, White D, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antiviral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:992-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.14328

7. Rogal SS, McCarthy R, Reid A, et al. Primary care and hepatology provider-perceived barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C treatment candidacy and adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1933-1943. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4608-9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Race, gender, and other factors are associated with lack of HCV Tx

A retrospective study (N = 894) assessed factors associated with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) initiation.1 Patients who were HCV+ with at least 1 clinical visit during the study period completed a survey of psychological, behavioral, and social life assessments. The final cohort (57% male; 64% ≥ 61 years old) was divided into patients who initiated DAA treatment (n = 690) and those who did not (n = 204).

In an adjusted multivariable analysis, factors associated with lower odds of DAA initiation included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.59 vs White race; 95% CI, 0.36-0.98); perceived difficulty accessing medical care (aOR = 0.48 vs no difficulty; 95% CI, 0.27-0.83); recent intravenous (IV) drug use (aOR = 0.11 vs no use; 95% CI, 0.02-0.54); alcohol use disorder (AUD; aOR = 0.58 vs no AUD; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90); severe depression (aOR = 0.42 vs no depression; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9); recent homelessness (aOR = 0.36 vs no homelessness; 95% CI, 0.14-0.94); and recent incarceration (aOR = 0.34 vs no incarceration; 95% CI, 0.12-0.94).1

A multicenter, observational prospective cohort study (N = 3075) evaluated receipt of HCV treatment for patients co-infected with HCV and HIV.2 The primary outcome was initiation of HCV treatment with DAAs; 1957 patients initiated therapy, while 1118 did not. Significant independent risk factors for noninitiation of treatment included age younger than 50 years, a history of IV drug use, and use of opioid substitution therapy (OST). Other factors included psychiatric comorbidity (odds ratio [OR] = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.27-0.75), incarceration (OR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.43-0.87), and female gender (OR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98). In a multivariate analysis limited to those with a history of IV drug use, both use of OST (aOR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and recent IV drug use (aOR = 0.019; 95% CI, 0.004-0.087) were identified as factors with low odds of treatment implementation.2

A retrospective cohort study (N = 1024) of medical charts examined the barriers to treatment in adults with chronic HCV infection.3 Of the patient population, 208 were treated and 816 were untreated. Patients not receiving DAAs were associated with poor adherence to/loss to follow-up (n = 548; OR = 36.6; 95% CI, 19.6-68.4); significant psychiatric illness (n = 103; OR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.13-3.71); and coinfection with HIV (n = 188; OR = 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5-8.2).3

A German multicenter retrospective case-control study (N = 793) identified factors in patient and physician decisions to initiate treatment for HCV.4 Patients were ≥ 18 years old, confirmed to be HCV+, and had visited their physician at least 1 time during the observation period. A total of 573 patients received treatment and 220 did not. Patients and clinicians of those who chose not to receive treatment completed a survey that collected reasons for not treating. The most prevalent reason for not initiating treatment was patient wish (42%). This was further delineated to reveal that 17.3% attributed their decision to fear of treatment and 13.2% to fear of adverse events. Other factors associated with nontreatment included IV drug use (aOR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.16-0.62); HIV coinfection (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.40); and use of OST (aOR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68). Patient demographics associated with wish not to be treated included older age (20.2% of those ≥ 40 years old vs 6.4% of those < 40 years old; P = .03) and female gender (51.0% of females vs 35.2% of males; P = .019).4

An analysis of a French insurance database (N = 22,545) evaluated the incidence of HCV treatment with DAAs in patients who inject drugs (PWID) with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD).5 All participants (78% male; median age, 49 years) were chronically HCV-infected and covered by national health insurance. Individuals were grouped by AUD status: untreated (n = 5176), treated (n = 3020), and no AUD (n = 14349). After multivariate adjustment, those with untreated AUD had lower uptake of DAAs than those who did not have AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.94) and those with treated AUD (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.94). There were no differences between those with treated AUD and those who did not have AUD. Other factors associated with lower DAA uptake were access to care (aHR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-0.98) and female gender (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.9).5

A 2017 retrospective cohort study evaluated predictors and barriers to follow-up and treatment with DAAs among veterans who were HCV+.6 Patients (94% > 50 years old; 97% male; 48% white) had established HCV care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system. Of those who followed up with at least 1 visit to an HCV specialty clinic (n = 47,165), 29% received DAAs. Factors associated with lack of treatment included race (Black vs White: OR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82; Hispanic vs White: OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97); IV drug use (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80-0.88); AUD (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70-0.77); medical comorbidities (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.66-0.77); and hepatocellular carcinoma (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).6

Continue to: Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

A 2017 prospective qualitative study (N = 24) from a Veterans Affairs health care system analyzed provider-perceived barriers to initiation of and adherence to HCV treatment.7 The analysis focused on differences by provider specialty. Primary care providers (PCPs; n = 12; 17% with > 40 patients with HCV) and hepatology providers (HPs; n = 12; 83% with > 40 patients with HCV) participated in a semi-structured telephone-based interview, providing their perceptions of patient-level barriers to HCV treatment. Eight patient-level barrier themes were identified; these are outlined in the TABLE7 along with data for both PCPs and HPs.

Editor’s takeaway

These 7 cohort studies show us the factors we consider and the reasons we give to not initiate HCV treatment. Some of the factors seem reasonable, but many do not. We might use this list to remind and challenge ourselves to work through barriers to provide the best possible treatment.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Race, gender, and other factors are associated with lack of HCV Tx

A retrospective study (N = 894) assessed factors associated with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) initiation.1 Patients who were HCV+ with at least 1 clinical visit during the study period completed a survey of psychological, behavioral, and social life assessments. The final cohort (57% male; 64% ≥ 61 years old) was divided into patients who initiated DAA treatment (n = 690) and those who did not (n = 204).

In an adjusted multivariable analysis, factors associated with lower odds of DAA initiation included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.59 vs White race; 95% CI, 0.36-0.98); perceived difficulty accessing medical care (aOR = 0.48 vs no difficulty; 95% CI, 0.27-0.83); recent intravenous (IV) drug use (aOR = 0.11 vs no use; 95% CI, 0.02-0.54); alcohol use disorder (AUD; aOR = 0.58 vs no AUD; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90); severe depression (aOR = 0.42 vs no depression; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9); recent homelessness (aOR = 0.36 vs no homelessness; 95% CI, 0.14-0.94); and recent incarceration (aOR = 0.34 vs no incarceration; 95% CI, 0.12-0.94).1

A multicenter, observational prospective cohort study (N = 3075) evaluated receipt of HCV treatment for patients co-infected with HCV and HIV.2 The primary outcome was initiation of HCV treatment with DAAs; 1957 patients initiated therapy, while 1118 did not. Significant independent risk factors for noninitiation of treatment included age younger than 50 years, a history of IV drug use, and use of opioid substitution therapy (OST). Other factors included psychiatric comorbidity (odds ratio [OR] = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.27-0.75), incarceration (OR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.43-0.87), and female gender (OR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98). In a multivariate analysis limited to those with a history of IV drug use, both use of OST (aOR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and recent IV drug use (aOR = 0.019; 95% CI, 0.004-0.087) were identified as factors with low odds of treatment implementation.2

A retrospective cohort study (N = 1024) of medical charts examined the barriers to treatment in adults with chronic HCV infection.3 Of the patient population, 208 were treated and 816 were untreated. Patients not receiving DAAs were associated with poor adherence to/loss to follow-up (n = 548; OR = 36.6; 95% CI, 19.6-68.4); significant psychiatric illness (n = 103; OR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.13-3.71); and coinfection with HIV (n = 188; OR = 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5-8.2).3

A German multicenter retrospective case-control study (N = 793) identified factors in patient and physician decisions to initiate treatment for HCV.4 Patients were ≥ 18 years old, confirmed to be HCV+, and had visited their physician at least 1 time during the observation period. A total of 573 patients received treatment and 220 did not. Patients and clinicians of those who chose not to receive treatment completed a survey that collected reasons for not treating. The most prevalent reason for not initiating treatment was patient wish (42%). This was further delineated to reveal that 17.3% attributed their decision to fear of treatment and 13.2% to fear of adverse events. Other factors associated with nontreatment included IV drug use (aOR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.16-0.62); HIV coinfection (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.40); and use of OST (aOR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68). Patient demographics associated with wish not to be treated included older age (20.2% of those ≥ 40 years old vs 6.4% of those < 40 years old; P = .03) and female gender (51.0% of females vs 35.2% of males; P = .019).4

An analysis of a French insurance database (N = 22,545) evaluated the incidence of HCV treatment with DAAs in patients who inject drugs (PWID) with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD).5 All participants (78% male; median age, 49 years) were chronically HCV-infected and covered by national health insurance. Individuals were grouped by AUD status: untreated (n = 5176), treated (n = 3020), and no AUD (n = 14349). After multivariate adjustment, those with untreated AUD had lower uptake of DAAs than those who did not have AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.94) and those with treated AUD (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.94). There were no differences between those with treated AUD and those who did not have AUD. Other factors associated with lower DAA uptake were access to care (aHR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-0.98) and female gender (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.9).5

A 2017 retrospective cohort study evaluated predictors and barriers to follow-up and treatment with DAAs among veterans who were HCV+.6 Patients (94% > 50 years old; 97% male; 48% white) had established HCV care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system. Of those who followed up with at least 1 visit to an HCV specialty clinic (n = 47,165), 29% received DAAs. Factors associated with lack of treatment included race (Black vs White: OR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82; Hispanic vs White: OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97); IV drug use (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80-0.88); AUD (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70-0.77); medical comorbidities (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.66-0.77); and hepatocellular carcinoma (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).6

Continue to: Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

A 2017 prospective qualitative study (N = 24) from a Veterans Affairs health care system analyzed provider-perceived barriers to initiation of and adherence to HCV treatment.7 The analysis focused on differences by provider specialty. Primary care providers (PCPs; n = 12; 17% with > 40 patients with HCV) and hepatology providers (HPs; n = 12; 83% with > 40 patients with HCV) participated in a semi-structured telephone-based interview, providing their perceptions of patient-level barriers to HCV treatment. Eight patient-level barrier themes were identified; these are outlined in the TABLE7 along with data for both PCPs and HPs.

Editor’s takeaway

These 7 cohort studies show us the factors we consider and the reasons we give to not initiate HCV treatment. Some of the factors seem reasonable, but many do not. We might use this list to remind and challenge ourselves to work through barriers to provide the best possible treatment.

1. Spradling PR, Zhong Y, Moorman AC, et al. Psychosocial obstacles to hepatitis C treatment initiation among patients in care: a hitch in the cascade of cure. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:400-411. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1632

2. Rivero-Juarez A, Tellez F, Castano-Carracedo M, et al. Parenteral drug use as the main barrier to hepatitis C treatment uptake in HIV-infected patients. HIV Medicine. 2019;20:359-367. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12715

3. Al-Khazraji A, Patel I, Saleh M, et al. Identifying barriers to the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis. 2020;38:46-52. doi: 10.1159/000501821

4. Buggisch P, Heiken H, Mauss S, et al. Barriers to initiation of hepatitis C virus therapy in Germany: a retrospective, case-controlled study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:3p250833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250833

5. Barré T, Marcellin F, Di Beo V, et al. Untreated alcohol use disorder in people who inject drugs (PWID) in France: a major barrier to HCV treatment uptake (the ANRS-FANTASIO study). Addiction. 2019;115:573-582. doi: 10.1111/add.14820

6. Lin M, Kramer J, White D, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antiviral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:992-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.14328

7. Rogal SS, McCarthy R, Reid A, et al. Primary care and hepatology provider-perceived barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C treatment candidacy and adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1933-1943. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4608-9

1. Spradling PR, Zhong Y, Moorman AC, et al. Psychosocial obstacles to hepatitis C treatment initiation among patients in care: a hitch in the cascade of cure. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:400-411. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1632

2. Rivero-Juarez A, Tellez F, Castano-Carracedo M, et al. Parenteral drug use as the main barrier to hepatitis C treatment uptake in HIV-infected patients. HIV Medicine. 2019;20:359-367. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12715

3. Al-Khazraji A, Patel I, Saleh M, et al. Identifying barriers to the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis. 2020;38:46-52. doi: 10.1159/000501821

4. Buggisch P, Heiken H, Mauss S, et al. Barriers to initiation of hepatitis C virus therapy in Germany: a retrospective, case-controlled study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:3p250833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250833

5. Barré T, Marcellin F, Di Beo V, et al. Untreated alcohol use disorder in people who inject drugs (PWID) in France: a major barrier to HCV treatment uptake (the ANRS-FANTASIO study). Addiction. 2019;115:573-582. doi: 10.1111/add.14820

6. Lin M, Kramer J, White D, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antiviral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:992-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.14328

7. Rogal SS, McCarthy R, Reid A, et al. Primary care and hepatology provider-perceived barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C treatment candidacy and adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1933-1943. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4608-9

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Multiple patient-specific and provider-perceived factors delay initiation of treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Patient-specific barriers to initiation of treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) include age, race, gender, economic status, insurance status, and comorbidities such as HIV coinfection, psychiatric illness, and other psychosocial factors.

Provider-perceived patient factors include substance abuse history, older age, psychiatric illness, medical comorbidities, treatment adverse effect risks, and factors that might limit adherence (eg, comprehension level).

Study limitations included problems with generalizability of the populations studied and variability in reporting or interpreting data associated with substance or alcohol use disorders

Living-donor liver transplants linked with substantial survival benefit

Living-donor liver transplant recipients gained an additional 13-17 years of life, compared with patients who remained on the wait list, according to a retrospective case-control study.

The data suggest that the life-years gained are comparable to or greater than those conferred by either other lifesaving procedures or liver transplant from a deceased donor, wrote the researchers, led by Whitney Jackson, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and medical director of living-donor liver transplantation at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

“Despite the acceptance of living-donor liver transplant as a lifesaving procedure for end-stage liver disease, it remains underused in the United States,” the authors wrote in JAMA Surgery. “This study’s findings challenge current perceptions regarding when the survival benefit of a living-donor transplant occurs.”

Dr. Jackson and colleagues conducted a retrospective, secondary analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database for 119,275 U.S. liver transplant candidates and recipients from January 2012 to September 2021. They assessed the survival benefit, life-years saved, and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium levels (MELD-Na) score at which the survival benefit was obtained, compared with those who remained on the wait list.

The research team included 116,455 liver transplant candidates who were 18 and older and assigned to the wait list, as well as 2,820 patients who received a living-donor liver transplant. Patients listed for retransplant or multiorgan transplant were excluded, as were those with prior kidney or liver transplants.

The mean age of the study participants was 55 years, and 63% were men. Overall, 70.2% were White, 15.8% were Hispanic or Latinx, 8.2% were Black or African American, 4.3% were Asian, 0.9% were American Indian or Alaska Native, and 0.2% were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The most common etiologies were alcoholic cirrhosis (23.8%) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (15.9%).

Compared with patients on the wait list, recipients of a living-donor liver transplant were younger, more often women, more educated, and more often White. A greater proportion of transplant recipients had a primary etiology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (19.8%) and cholestatic liver disease (24.1%). At wait list placement, one-third of candidates had a MELD-Na score of 14 or higher.

The research team found a significant survival benefit for patients receiving a living-donor liver transplant based on mortality risk and survival scores. The survival benefit was significant at a MELD-Na score as low as 11, with a 34% decrease(95% confidence interval [CI], 17.4%-52.0%) in mortality compared with the wait list. In addition, mortality risk models confirmed a survival benefit for patients with a MELD-Na score of 11 or higher at 1 year after transplant (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.88; P = .006). At a MELD-Na score of 14-16, mortality decreased by about 50% (aHR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.34-0.66; P < .001).

The probability of death from a living-donor liver transplant for patients with very low MELD-Na scores (between 6 and 10) was greater than that for patients on the wait list for the first 259 days, at which point the risk of death for both groups was equal. At 471 days, the probability of survival in both groups was equal. As the MELD-Na score increased, both the time to equal risk of death and the time to equal survival decreased, demonstrating that the survival benefit occurs much earlier for patients with a higher MELD-Na score.

Analysis of life-years from transplant showed living-donor transplant recipients gained 13-17 life-years compared to those who didn’t receive one.

“Living-donor liver transplantation is a valuable yet underutilized strategy to address the significant organ shortage and long waiting times on the transplant list in the U.S.,” said Renu Dhanasekaran, MD, PhD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Dhanasekaran, who wasn’t involved with this study, also welcomed the finding that living-donor liver transplantation can benefit patients with low MELD-Na scores, even below the expected cutoff at 15. According to the study authors, previous research had suggested benefit would be seen only at MELD-Na 15 and above.

“In my practice, I have several patients whose symptoms are out of proportion to their MELD score, and data like this will convince them and their potential donors to avail a transplant at an earlier stage,” she said.

The findings challenge the current paradigm around the timing of referral for a liver transplant and may have ramifications for allocation policies for deceased donors, the study authors wrote. The data can also help to contextualize risk-benefit discussions for donors and recipients.

“Donating a part of one’s liver to save a patient suffering from end-stage liver disease is an incredible act of selfless love,” Dr. Dhanasekaran said. “I hope strong positive data from studies like this one encourage more donors, patients, and transplant centers to expand the use of [living-donor liver transplant].”

The authors reported no grant support or funding sources for this study. One author disclosed being married to the current chair of the United Network for Organ Sharing’s Liver and Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee. No other conflicts of interest were reported. Dr. Dhanasekaran reported no relevant disclosures.

Living-donor liver transplant recipients gained an additional 13-17 years of life, compared with patients who remained on the wait list, according to a retrospective case-control study.

The data suggest that the life-years gained are comparable to or greater than those conferred by either other lifesaving procedures or liver transplant from a deceased donor, wrote the researchers, led by Whitney Jackson, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and medical director of living-donor liver transplantation at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

“Despite the acceptance of living-donor liver transplant as a lifesaving procedure for end-stage liver disease, it remains underused in the United States,” the authors wrote in JAMA Surgery. “This study’s findings challenge current perceptions regarding when the survival benefit of a living-donor transplant occurs.”

Dr. Jackson and colleagues conducted a retrospective, secondary analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database for 119,275 U.S. liver transplant candidates and recipients from January 2012 to September 2021. They assessed the survival benefit, life-years saved, and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium levels (MELD-Na) score at which the survival benefit was obtained, compared with those who remained on the wait list.

The research team included 116,455 liver transplant candidates who were 18 and older and assigned to the wait list, as well as 2,820 patients who received a living-donor liver transplant. Patients listed for retransplant or multiorgan transplant were excluded, as were those with prior kidney or liver transplants.

The mean age of the study participants was 55 years, and 63% were men. Overall, 70.2% were White, 15.8% were Hispanic or Latinx, 8.2% were Black or African American, 4.3% were Asian, 0.9% were American Indian or Alaska Native, and 0.2% were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The most common etiologies were alcoholic cirrhosis (23.8%) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (15.9%).

Compared with patients on the wait list, recipients of a living-donor liver transplant were younger, more often women, more educated, and more often White. A greater proportion of transplant recipients had a primary etiology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (19.8%) and cholestatic liver disease (24.1%). At wait list placement, one-third of candidates had a MELD-Na score of 14 or higher.

The research team found a significant survival benefit for patients receiving a living-donor liver transplant based on mortality risk and survival scores. The survival benefit was significant at a MELD-Na score as low as 11, with a 34% decrease(95% confidence interval [CI], 17.4%-52.0%) in mortality compared with the wait list. In addition, mortality risk models confirmed a survival benefit for patients with a MELD-Na score of 11 or higher at 1 year after transplant (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.88; P = .006). At a MELD-Na score of 14-16, mortality decreased by about 50% (aHR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.34-0.66; P < .001).

The probability of death from a living-donor liver transplant for patients with very low MELD-Na scores (between 6 and 10) was greater than that for patients on the wait list for the first 259 days, at which point the risk of death for both groups was equal. At 471 days, the probability of survival in both groups was equal. As the MELD-Na score increased, both the time to equal risk of death and the time to equal survival decreased, demonstrating that the survival benefit occurs much earlier for patients with a higher MELD-Na score.

Analysis of life-years from transplant showed living-donor transplant recipients gained 13-17 life-years compared to those who didn’t receive one.

“Living-donor liver transplantation is a valuable yet underutilized strategy to address the significant organ shortage and long waiting times on the transplant list in the U.S.,” said Renu Dhanasekaran, MD, PhD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Dhanasekaran, who wasn’t involved with this study, also welcomed the finding that living-donor liver transplantation can benefit patients with low MELD-Na scores, even below the expected cutoff at 15. According to the study authors, previous research had suggested benefit would be seen only at MELD-Na 15 and above.

“In my practice, I have several patients whose symptoms are out of proportion to their MELD score, and data like this will convince them and their potential donors to avail a transplant at an earlier stage,” she said.

The findings challenge the current paradigm around the timing of referral for a liver transplant and may have ramifications for allocation policies for deceased donors, the study authors wrote. The data can also help to contextualize risk-benefit discussions for donors and recipients.

“Donating a part of one’s liver to save a patient suffering from end-stage liver disease is an incredible act of selfless love,” Dr. Dhanasekaran said. “I hope strong positive data from studies like this one encourage more donors, patients, and transplant centers to expand the use of [living-donor liver transplant].”

The authors reported no grant support or funding sources for this study. One author disclosed being married to the current chair of the United Network for Organ Sharing’s Liver and Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee. No other conflicts of interest were reported. Dr. Dhanasekaran reported no relevant disclosures.

Living-donor liver transplant recipients gained an additional 13-17 years of life, compared with patients who remained on the wait list, according to a retrospective case-control study.

The data suggest that the life-years gained are comparable to or greater than those conferred by either other lifesaving procedures or liver transplant from a deceased donor, wrote the researchers, led by Whitney Jackson, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and medical director of living-donor liver transplantation at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

“Despite the acceptance of living-donor liver transplant as a lifesaving procedure for end-stage liver disease, it remains underused in the United States,” the authors wrote in JAMA Surgery. “This study’s findings challenge current perceptions regarding when the survival benefit of a living-donor transplant occurs.”

Dr. Jackson and colleagues conducted a retrospective, secondary analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database for 119,275 U.S. liver transplant candidates and recipients from January 2012 to September 2021. They assessed the survival benefit, life-years saved, and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease incorporating sodium levels (MELD-Na) score at which the survival benefit was obtained, compared with those who remained on the wait list.

The research team included 116,455 liver transplant candidates who were 18 and older and assigned to the wait list, as well as 2,820 patients who received a living-donor liver transplant. Patients listed for retransplant or multiorgan transplant were excluded, as were those with prior kidney or liver transplants.

The mean age of the study participants was 55 years, and 63% were men. Overall, 70.2% were White, 15.8% were Hispanic or Latinx, 8.2% were Black or African American, 4.3% were Asian, 0.9% were American Indian or Alaska Native, and 0.2% were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The most common etiologies were alcoholic cirrhosis (23.8%) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (15.9%).

Compared with patients on the wait list, recipients of a living-donor liver transplant were younger, more often women, more educated, and more often White. A greater proportion of transplant recipients had a primary etiology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (19.8%) and cholestatic liver disease (24.1%). At wait list placement, one-third of candidates had a MELD-Na score of 14 or higher.

The research team found a significant survival benefit for patients receiving a living-donor liver transplant based on mortality risk and survival scores. The survival benefit was significant at a MELD-Na score as low as 11, with a 34% decrease(95% confidence interval [CI], 17.4%-52.0%) in mortality compared with the wait list. In addition, mortality risk models confirmed a survival benefit for patients with a MELD-Na score of 11 or higher at 1 year after transplant (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.88; P = .006). At a MELD-Na score of 14-16, mortality decreased by about 50% (aHR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.34-0.66; P < .001).

The probability of death from a living-donor liver transplant for patients with very low MELD-Na scores (between 6 and 10) was greater than that for patients on the wait list for the first 259 days, at which point the risk of death for both groups was equal. At 471 days, the probability of survival in both groups was equal. As the MELD-Na score increased, both the time to equal risk of death and the time to equal survival decreased, demonstrating that the survival benefit occurs much earlier for patients with a higher MELD-Na score.

Analysis of life-years from transplant showed living-donor transplant recipients gained 13-17 life-years compared to those who didn’t receive one.

“Living-donor liver transplantation is a valuable yet underutilized strategy to address the significant organ shortage and long waiting times on the transplant list in the U.S.,” said Renu Dhanasekaran, MD, PhD, assistant professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Dhanasekaran, who wasn’t involved with this study, also welcomed the finding that living-donor liver transplantation can benefit patients with low MELD-Na scores, even below the expected cutoff at 15. According to the study authors, previous research had suggested benefit would be seen only at MELD-Na 15 and above.

“In my practice, I have several patients whose symptoms are out of proportion to their MELD score, and data like this will convince them and their potential donors to avail a transplant at an earlier stage,” she said.

The findings challenge the current paradigm around the timing of referral for a liver transplant and may have ramifications for allocation policies for deceased donors, the study authors wrote. The data can also help to contextualize risk-benefit discussions for donors and recipients.

“Donating a part of one’s liver to save a patient suffering from end-stage liver disease is an incredible act of selfless love,” Dr. Dhanasekaran said. “I hope strong positive data from studies like this one encourage more donors, patients, and transplant centers to expand the use of [living-donor liver transplant].”

The authors reported no grant support or funding sources for this study. One author disclosed being married to the current chair of the United Network for Organ Sharing’s Liver and Intestinal Organ Transplantation Committee. No other conflicts of interest were reported. Dr. Dhanasekaran reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Pervasive ‘forever chemical’ linked to liver cancer

The correlation does not prove that PFOS causes this cancer, and more research is needed, but in the meantime, people should limit their exposure to it and others in its class, said Jesse Goodrich, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in environmental medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“If you’re at risk for liver cancer because you have other risk factors, then these chemicals have the potential to kind of send you over the edge,” he told this news organization.

Dr. Goodrich and colleagues published their research online in JHEP Reports.

Dubbed “forever chemicals” because they can take thousands of years to break down, polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) figure in makeup, food packaging, waterproof clothing, nonstick cookware, firefighting foams, and groundwater. They have spread through the atmosphere into rain and can be found in the blood of most Americans. PFOS is one of the most widely used PFAS.

“You can’t really escape them,” Dr. Goodrich said.

Previous research has linked PFAS to infertility, pregnancy complications, learning and behavioral problems in children, immune system issues, and higher cholesterol, as well as other cancers. Some experiments in animals suggested PFAS could cause liver cancer, and others showed a correlation between PFAS serum levels and biomarkers associated with liver cancer. But many of these health effects take a long time to develop.

“It wasn’t until we started to get really highly exposed groups of people that we started, as scientists, to be able to figure out what was going on,” said Dr. Goodrich.

High exposure, increased incidence

To measure the relationship between PFAS exposure and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma more definitively, Dr. Goodrich and colleagues analyzed data from the Multiethnic Cohort Study, a cohort of more than 200,000 people of African, Latin, Native Hawaiian, Japanese, and European ancestry tracked since the early 1990s in California and Hawaii. About 67,000 participants provided blood samples from 2001 to 2007.

From this cohort, the researchers found 50 people who later developed hepatocellular carcinoma. The researchers matched these patients with 50 controls of similar age at blood collection, sex, race, ethnicity, and study area who did not develop the cancer.

They found that people with more than 54.9 mcg/L of PFOS in their blood before any diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma were almost five times more likely to get the cancer (odds ratio 4.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-16.0), which was statistically significant (P = .02).

This level of PFOS corresponds to the 90th percentile found in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

To get some idea of the mechanism by which PFOS might do its damage, the researchers also looked for linkage to levels of metabolites.

They found an overlap among high PFOS levels, hepatocellular carcinoma, and high levels of glucose, butyric acid (a short chain fatty acid), alpha-Ketoisovaleric acid (alpha branched-chain alpha-keto acid), and 7alpha-Hydroxy-3-oxo-4-cholestenoate (a bile acid). These metabolites have been associated in previous studies with metabolic disorders and liver disease.

Similarly, the researchers identified an association among the cancer, PFOS, and alterations in amino acid and glycan biosynthesis pathways.

Risk mitigation

The half-life of PFAS in the human body is about 3-7 years, said Dr. Goodrich.

“There’s not much you can do once they’re in there,” he said. “So, the focus needs to be on preventing the exposure in the first place.”

People can limit exposure by avoiding water contaminated with PFAS or filtering it out, Dr. Goodrich said. He recommended avoiding fish from contaminated waterways and nonstick cookware. The Environmental Protection Agency has more detailed recommendations.

But giving patients individualized recommendations is difficult, said Vincent Chen, MD, MS, a clinical instructor in gastroenterology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study. Most clinicians don’t know their patients’ PFOS levels.

“It’s not that easy to get a test,” Dr. Chen told this news organization.

People can also mitigate their risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma, such as a poor diet, a lack of exercise, and smoking, said Dr. Goodrich.

The researchers found that patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were more likely to be overweight and have diabetes, and PFOS was associated with higher fasting glucose levels. This raises the possibility that PFOS increases the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma by causing diabetes and obesity.

Dr. Goodrich and his colleagues tried to address this question by adjusting for baseline body mass index (BMI) and diabetes diagnosis in their statistical analysis.

After adjusting for BMI, they found that the association between PFOS and hepatocellular carcinoma diminished to a threefold risk (OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 0.78-10.00) and was no longer statistically significant (P = .11).

On the other hand, adjusting for diabetes did not change the significance of the relationship between PFOS and the cancer (OR, 5.7; 95% CI, 1.10-30.00; P = .04).

The sample size was probably too small to adequately tease out this relationship, Dr. Chen said. Still, he said, “I thought it was a very, very important study.”

The levels of PFOS found in the blood of Americans has been declining since the 1999-2000 NHANES, Dr. Chen pointed out. But that’s not as reassuring as it sounds.

“The problem is that if you put a regulation limiting the use of one PFAS, what people can do is just substitute with another PFAS or another molecule, which for all we know could be equally harmful,” Dr. Chen said.

Funding was provided by the Southern California Environmental Health Science Center supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Goodrich and Dr. Chen report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The correlation does not prove that PFOS causes this cancer, and more research is needed, but in the meantime, people should limit their exposure to it and others in its class, said Jesse Goodrich, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in environmental medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“If you’re at risk for liver cancer because you have other risk factors, then these chemicals have the potential to kind of send you over the edge,” he told this news organization.

Dr. Goodrich and colleagues published their research online in JHEP Reports.

Dubbed “forever chemicals” because they can take thousands of years to break down, polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) figure in makeup, food packaging, waterproof clothing, nonstick cookware, firefighting foams, and groundwater. They have spread through the atmosphere into rain and can be found in the blood of most Americans. PFOS is one of the most widely used PFAS.

“You can’t really escape them,” Dr. Goodrich said.

Previous research has linked PFAS to infertility, pregnancy complications, learning and behavioral problems in children, immune system issues, and higher cholesterol, as well as other cancers. Some experiments in animals suggested PFAS could cause liver cancer, and others showed a correlation between PFAS serum levels and biomarkers associated with liver cancer. But many of these health effects take a long time to develop.

“It wasn’t until we started to get really highly exposed groups of people that we started, as scientists, to be able to figure out what was going on,” said Dr. Goodrich.

High exposure, increased incidence

To measure the relationship between PFAS exposure and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma more definitively, Dr. Goodrich and colleagues analyzed data from the Multiethnic Cohort Study, a cohort of more than 200,000 people of African, Latin, Native Hawaiian, Japanese, and European ancestry tracked since the early 1990s in California and Hawaii. About 67,000 participants provided blood samples from 2001 to 2007.

From this cohort, the researchers found 50 people who later developed hepatocellular carcinoma. The researchers matched these patients with 50 controls of similar age at blood collection, sex, race, ethnicity, and study area who did not develop the cancer.

They found that people with more than 54.9 mcg/L of PFOS in their blood before any diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma were almost five times more likely to get the cancer (odds ratio 4.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-16.0), which was statistically significant (P = .02).

This level of PFOS corresponds to the 90th percentile found in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

To get some idea of the mechanism by which PFOS might do its damage, the researchers also looked for linkage to levels of metabolites.

They found an overlap among high PFOS levels, hepatocellular carcinoma, and high levels of glucose, butyric acid (a short chain fatty acid), alpha-Ketoisovaleric acid (alpha branched-chain alpha-keto acid), and 7alpha-Hydroxy-3-oxo-4-cholestenoate (a bile acid). These metabolites have been associated in previous studies with metabolic disorders and liver disease.

Similarly, the researchers identified an association among the cancer, PFOS, and alterations in amino acid and glycan biosynthesis pathways.

Risk mitigation

The half-life of PFAS in the human body is about 3-7 years, said Dr. Goodrich.

“There’s not much you can do once they’re in there,” he said. “So, the focus needs to be on preventing the exposure in the first place.”

People can limit exposure by avoiding water contaminated with PFAS or filtering it out, Dr. Goodrich said. He recommended avoiding fish from contaminated waterways and nonstick cookware. The Environmental Protection Agency has more detailed recommendations.

But giving patients individualized recommendations is difficult, said Vincent Chen, MD, MS, a clinical instructor in gastroenterology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study. Most clinicians don’t know their patients’ PFOS levels.

“It’s not that easy to get a test,” Dr. Chen told this news organization.

People can also mitigate their risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma, such as a poor diet, a lack of exercise, and smoking, said Dr. Goodrich.

The researchers found that patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were more likely to be overweight and have diabetes, and PFOS was associated with higher fasting glucose levels. This raises the possibility that PFOS increases the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma by causing diabetes and obesity.

Dr. Goodrich and his colleagues tried to address this question by adjusting for baseline body mass index (BMI) and diabetes diagnosis in their statistical analysis.

After adjusting for BMI, they found that the association between PFOS and hepatocellular carcinoma diminished to a threefold risk (OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 0.78-10.00) and was no longer statistically significant (P = .11).

On the other hand, adjusting for diabetes did not change the significance of the relationship between PFOS and the cancer (OR, 5.7; 95% CI, 1.10-30.00; P = .04).

The sample size was probably too small to adequately tease out this relationship, Dr. Chen said. Still, he said, “I thought it was a very, very important study.”

The levels of PFOS found in the blood of Americans has been declining since the 1999-2000 NHANES, Dr. Chen pointed out. But that’s not as reassuring as it sounds.

“The problem is that if you put a regulation limiting the use of one PFAS, what people can do is just substitute with another PFAS or another molecule, which for all we know could be equally harmful,” Dr. Chen said.

Funding was provided by the Southern California Environmental Health Science Center supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Goodrich and Dr. Chen report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.