User login

One-week postsurgical interval for voiding trial increases pass rate

Women who underwent vaginal prolapse surgery and did not immediately have a successful voiding trial were seven times more likely to pass their second voiding trial if their follow-up was 7 days after surgery instead of 4 days, according to a study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This information is useful for setting expectations and for counseling patients on when it might be best to repeat a voiding trial in those with transient incomplete bladder emptying on the day of surgery, especially for those who may not live close to their surgeon, or for those who have difficulty traveling to the office,” said Jeffrey S. Schachar, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, N.C., and colleagues. “Despite a higher rate of initial unsuccessful office voiding trials, however, the early group did have significantly fewer days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, as well as total catheterization days,” including self-catheterization.

The researchers note that rates of temporary use of catheters after surgery vary widely, from 12% to 83%, likely because no consensus exists on how long to wait for voiding trials and what constitutes a successful trial.

“It is critical to identify patients with incomplete bladder emptying in order to prevent pain, myogenic and neurogenic damage, ureteral reflux and bladder overdistension that may further impair voiding function,” the authors wrote. “However, extending bladder drainage beyond the necessary recovery period may be associated with higher rates of urinary tract infection (UTI) and patient bother.”

To learn more about the best duration for postoperative catheter use, the researchers enrolled 102 patients before they underwent vaginal prolapse surgery at Wake Forest Baptist Health and Cleveland Clinic Florida from February 2017 to November 2019. The 29 patients with a successful voiding trial within 6 hours after surgery left the study, and 5 others were excluded for needing longer vaginal packing.

The voiding trial involved helping the patient stand to drain the bladder via the catheter, backfilling the bladder with 300 mL of saline solution through the catheter, removing the catheter to give women 1 hour to urinate, and then measuring the postvoid residual with a catheter or ultrasound. At least 100 mL postvoid residual was considered persistent incomplete bladder emptying.

The 60 remaining patients who did not pass the initial voiding trial and opted to remain in the study received a transurethral indwelling catheter and were randomly assigned to return for a second voiding trial either 2-4 days after surgery (depending on day of the week) or 7 days after surgery. The groups were demographically and clinically similar, with predominantly white postmenopausal, non-smoking women with stage II or III multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse.

Women without successful trials could continue with the transurethral catheter or give themselves intermittent catheterizations with a follow-up schedule determined by their surgeon. The researchers then tracked the women for 6 weeks to determine the rate of unsuccessful repeat voiding trials.

Among the women who returned 2-4 days post surgery, 23% had unsuccessful follow-up voiding trials, compared with 3% in the group returning 7 days after surgery (relative risk = 7; P = .02). The researchers calculated that one case of persistent postoperative incomplete bladder emptying was prevented for every five patients who used a catheter for 7 days after surgery.

Kevin A. Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said the study was well done, although the findings were unsurprising. He said the clinical implication is straightforward – to wait a week before doing a second voiding trial.

“I suspect these findings match the clinical experience of many surgeons. It is always good to see a well-done clinical trial on a topic,” Dr Ault said in an interview. “The most notable finding is how this impacts patient counseling. Gynecologists should tell their patients that it will take a week with a catheter when this problem arises.”

“The main limitation is whether this finding can be extrapolated to other gynecological surgeries, such as hysterectomy,” said Dr. Ault, who was not involved in the study. “Urinary retention is likely less common after that surgery, but it is still bothersome to patients.”

Dr. Schachar and associates also reported that patients in the earlier group “used significantly more morphine dose equivalents within 24 hours of the office voiding trial than the late-voiding trial group, which was expected given the proximity to surgery” (3 vs. 0.38; P = .005). However, new postoperative pain medication prescriptions and refills were similar in both groups.

Secondary endpoints included UTI rates, total days with a catheter, and patient experience of discomfort with the catheter. The two groups of women reported similar levels of catheter bother, but there was a nonsignificant difference in UTI rates: 23% in the earlier group, compared with 7% in the later group (P = .07).

The early-voiding trial group had an average 5 days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, compared with a significantly different 7 days in the later group (P = .0007). The early group also had fewer total days with an indwelling transurethral catheter and self-catheterization (6 days), compared with the late group (7 days; P = .0013). No patients had persistent incomplete bladder emptying after 17 days post surgery.

“Being able to adequately predict which patients are more likely to have unsuccessful postoperative voiding trials allows surgeons to better counsel their patients and may guide clinical decisions,” Dr. Schachar and associates said. They acknowledged, however, that their study’s biggest weakness is the small enrollment, which led to larger confidence intervals related to relative risk differences between the groups.

The study did not use external funding. Four of the investigators received grant, research funding, or honoraria from one or many medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The remaining researchers had no disclosures. Dr. Ault said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schachar JS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.001.

Women who underwent vaginal prolapse surgery and did not immediately have a successful voiding trial were seven times more likely to pass their second voiding trial if their follow-up was 7 days after surgery instead of 4 days, according to a study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This information is useful for setting expectations and for counseling patients on when it might be best to repeat a voiding trial in those with transient incomplete bladder emptying on the day of surgery, especially for those who may not live close to their surgeon, or for those who have difficulty traveling to the office,” said Jeffrey S. Schachar, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, N.C., and colleagues. “Despite a higher rate of initial unsuccessful office voiding trials, however, the early group did have significantly fewer days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, as well as total catheterization days,” including self-catheterization.

The researchers note that rates of temporary use of catheters after surgery vary widely, from 12% to 83%, likely because no consensus exists on how long to wait for voiding trials and what constitutes a successful trial.

“It is critical to identify patients with incomplete bladder emptying in order to prevent pain, myogenic and neurogenic damage, ureteral reflux and bladder overdistension that may further impair voiding function,” the authors wrote. “However, extending bladder drainage beyond the necessary recovery period may be associated with higher rates of urinary tract infection (UTI) and patient bother.”

To learn more about the best duration for postoperative catheter use, the researchers enrolled 102 patients before they underwent vaginal prolapse surgery at Wake Forest Baptist Health and Cleveland Clinic Florida from February 2017 to November 2019. The 29 patients with a successful voiding trial within 6 hours after surgery left the study, and 5 others were excluded for needing longer vaginal packing.

The voiding trial involved helping the patient stand to drain the bladder via the catheter, backfilling the bladder with 300 mL of saline solution through the catheter, removing the catheter to give women 1 hour to urinate, and then measuring the postvoid residual with a catheter or ultrasound. At least 100 mL postvoid residual was considered persistent incomplete bladder emptying.

The 60 remaining patients who did not pass the initial voiding trial and opted to remain in the study received a transurethral indwelling catheter and were randomly assigned to return for a second voiding trial either 2-4 days after surgery (depending on day of the week) or 7 days after surgery. The groups were demographically and clinically similar, with predominantly white postmenopausal, non-smoking women with stage II or III multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse.

Women without successful trials could continue with the transurethral catheter or give themselves intermittent catheterizations with a follow-up schedule determined by their surgeon. The researchers then tracked the women for 6 weeks to determine the rate of unsuccessful repeat voiding trials.

Among the women who returned 2-4 days post surgery, 23% had unsuccessful follow-up voiding trials, compared with 3% in the group returning 7 days after surgery (relative risk = 7; P = .02). The researchers calculated that one case of persistent postoperative incomplete bladder emptying was prevented for every five patients who used a catheter for 7 days after surgery.

Kevin A. Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said the study was well done, although the findings were unsurprising. He said the clinical implication is straightforward – to wait a week before doing a second voiding trial.

“I suspect these findings match the clinical experience of many surgeons. It is always good to see a well-done clinical trial on a topic,” Dr Ault said in an interview. “The most notable finding is how this impacts patient counseling. Gynecologists should tell their patients that it will take a week with a catheter when this problem arises.”

“The main limitation is whether this finding can be extrapolated to other gynecological surgeries, such as hysterectomy,” said Dr. Ault, who was not involved in the study. “Urinary retention is likely less common after that surgery, but it is still bothersome to patients.”

Dr. Schachar and associates also reported that patients in the earlier group “used significantly more morphine dose equivalents within 24 hours of the office voiding trial than the late-voiding trial group, which was expected given the proximity to surgery” (3 vs. 0.38; P = .005). However, new postoperative pain medication prescriptions and refills were similar in both groups.

Secondary endpoints included UTI rates, total days with a catheter, and patient experience of discomfort with the catheter. The two groups of women reported similar levels of catheter bother, but there was a nonsignificant difference in UTI rates: 23% in the earlier group, compared with 7% in the later group (P = .07).

The early-voiding trial group had an average 5 days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, compared with a significantly different 7 days in the later group (P = .0007). The early group also had fewer total days with an indwelling transurethral catheter and self-catheterization (6 days), compared with the late group (7 days; P = .0013). No patients had persistent incomplete bladder emptying after 17 days post surgery.

“Being able to adequately predict which patients are more likely to have unsuccessful postoperative voiding trials allows surgeons to better counsel their patients and may guide clinical decisions,” Dr. Schachar and associates said. They acknowledged, however, that their study’s biggest weakness is the small enrollment, which led to larger confidence intervals related to relative risk differences between the groups.

The study did not use external funding. Four of the investigators received grant, research funding, or honoraria from one or many medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The remaining researchers had no disclosures. Dr. Ault said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schachar JS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.001.

Women who underwent vaginal prolapse surgery and did not immediately have a successful voiding trial were seven times more likely to pass their second voiding trial if their follow-up was 7 days after surgery instead of 4 days, according to a study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

“This information is useful for setting expectations and for counseling patients on when it might be best to repeat a voiding trial in those with transient incomplete bladder emptying on the day of surgery, especially for those who may not live close to their surgeon, or for those who have difficulty traveling to the office,” said Jeffrey S. Schachar, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Health in Winston-Salem, N.C., and colleagues. “Despite a higher rate of initial unsuccessful office voiding trials, however, the early group did have significantly fewer days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, as well as total catheterization days,” including self-catheterization.

The researchers note that rates of temporary use of catheters after surgery vary widely, from 12% to 83%, likely because no consensus exists on how long to wait for voiding trials and what constitutes a successful trial.

“It is critical to identify patients with incomplete bladder emptying in order to prevent pain, myogenic and neurogenic damage, ureteral reflux and bladder overdistension that may further impair voiding function,” the authors wrote. “However, extending bladder drainage beyond the necessary recovery period may be associated with higher rates of urinary tract infection (UTI) and patient bother.”

To learn more about the best duration for postoperative catheter use, the researchers enrolled 102 patients before they underwent vaginal prolapse surgery at Wake Forest Baptist Health and Cleveland Clinic Florida from February 2017 to November 2019. The 29 patients with a successful voiding trial within 6 hours after surgery left the study, and 5 others were excluded for needing longer vaginal packing.

The voiding trial involved helping the patient stand to drain the bladder via the catheter, backfilling the bladder with 300 mL of saline solution through the catheter, removing the catheter to give women 1 hour to urinate, and then measuring the postvoid residual with a catheter or ultrasound. At least 100 mL postvoid residual was considered persistent incomplete bladder emptying.

The 60 remaining patients who did not pass the initial voiding trial and opted to remain in the study received a transurethral indwelling catheter and were randomly assigned to return for a second voiding trial either 2-4 days after surgery (depending on day of the week) or 7 days after surgery. The groups were demographically and clinically similar, with predominantly white postmenopausal, non-smoking women with stage II or III multicompartment pelvic organ prolapse.

Women without successful trials could continue with the transurethral catheter or give themselves intermittent catheterizations with a follow-up schedule determined by their surgeon. The researchers then tracked the women for 6 weeks to determine the rate of unsuccessful repeat voiding trials.

Among the women who returned 2-4 days post surgery, 23% had unsuccessful follow-up voiding trials, compared with 3% in the group returning 7 days after surgery (relative risk = 7; P = .02). The researchers calculated that one case of persistent postoperative incomplete bladder emptying was prevented for every five patients who used a catheter for 7 days after surgery.

Kevin A. Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said the study was well done, although the findings were unsurprising. He said the clinical implication is straightforward – to wait a week before doing a second voiding trial.

“I suspect these findings match the clinical experience of many surgeons. It is always good to see a well-done clinical trial on a topic,” Dr Ault said in an interview. “The most notable finding is how this impacts patient counseling. Gynecologists should tell their patients that it will take a week with a catheter when this problem arises.”

“The main limitation is whether this finding can be extrapolated to other gynecological surgeries, such as hysterectomy,” said Dr. Ault, who was not involved in the study. “Urinary retention is likely less common after that surgery, but it is still bothersome to patients.”

Dr. Schachar and associates also reported that patients in the earlier group “used significantly more morphine dose equivalents within 24 hours of the office voiding trial than the late-voiding trial group, which was expected given the proximity to surgery” (3 vs. 0.38; P = .005). However, new postoperative pain medication prescriptions and refills were similar in both groups.

Secondary endpoints included UTI rates, total days with a catheter, and patient experience of discomfort with the catheter. The two groups of women reported similar levels of catheter bother, but there was a nonsignificant difference in UTI rates: 23% in the earlier group, compared with 7% in the later group (P = .07).

The early-voiding trial group had an average 5 days with an indwelling transurethral catheter, compared with a significantly different 7 days in the later group (P = .0007). The early group also had fewer total days with an indwelling transurethral catheter and self-catheterization (6 days), compared with the late group (7 days; P = .0013). No patients had persistent incomplete bladder emptying after 17 days post surgery.

“Being able to adequately predict which patients are more likely to have unsuccessful postoperative voiding trials allows surgeons to better counsel their patients and may guide clinical decisions,” Dr. Schachar and associates said. They acknowledged, however, that their study’s biggest weakness is the small enrollment, which led to larger confidence intervals related to relative risk differences between the groups.

The study did not use external funding. Four of the investigators received grant, research funding, or honoraria from one or many medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The remaining researchers had no disclosures. Dr. Ault said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Schachar JS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.001.

FROM AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Expert clarifies guidance on adolescent polycystic ovary syndrome

A trio of international expert recommendations mainly agree on essentials for the diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents, but some confusion persists, according to Robert L. Rosenfield, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

In a commentary published in the Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, Dr. Rosenfield, who convened one of the three conferences at which guidance was developed, noted that the three recommendations – published by the Pediatric Endocrine Society, the International Consortium of Paediatric Endocrinology, and the International PCOS Network in 2015, 2017, and 2018, respectively – “are fairly dense” and reviews have suggested a lack of agreement. His comments offer perspective and practice suggestions that follow the consensus of the recommendations.

“All the documents agree on the core diagnostic criteria for adolescent PCOS: otherwise unexplained evidence of ovulatory dysfunction, as indicated by menstrual abnormalities based on stage-appropriate standards, and evidence of an androgen excess disorder,” Dr. Rosenfield said.

The main differences among the recommendations from the three groups reflect tension between the value of an early diagnosis and the liabilities of a mistaken diagnosis in the context of attitudes about adolescent contraception. “These are issues not likely to be resolved easily, yet they are matters for every physician to consider in management of each case,” he said.

Dr. Rosenfield emphasized that clinicians must consider PCOS “in the general context of all causes of adolescent menstrual disturbances,” when evaluating a girl within 1-2 years of menarche who presents with a menstrual abnormality, hirsutism, and/or acne that has been resistant to topical treatment.

A key point on which the recommendations differ is whether further assessment is needed if the menstrual abnormality has persisted for 1 year (the 2018 recommendations) or 2 years (the 2015 and 2017 recommendations), Dr. Rosenfield explained. “What the conferees struggled with is differentiating how long after menarche a menstrual abnormality should persist to avoid confusing PCOS with normal immaturity of the menstrual cycle,” known as physiologic adolescent anovulation (PAA). “The degree of certainty is improved only modestly by waiting 2 years rather than 1 year to make a diagnosis.”

However, the three documents agree that girls suspected of having PCOS within the first 1-2 years after menarche should be evaluated at that time, and followed with a diagnosis of “at risk for PCOS” if the early test results are consistent with a PCOS diagnosis, he said.

Another point of difference among the groups is the extent to which hirsutism and acne represent clinical evidence of hyperandrogenism that justifies testing for biochemical hyperandrogenism, Dr. Rosenfield said.

“All three sets of adolescent PCOS recommendations agree that investigation for biochemical hyperandrogenism be initiated by measuring serum total and/or free testosterone by specialty assays with well-defined reference ranges,” he said.

However, “documentation of biochemical hyperandrogenism has been problematic because standard platform assays of testosterone give grossly inaccurate results.”

As said Dr. Rosenfield. Guidelines in the United States favor estrogen-progestin combined oral contraceptives as first-line therapy, while the international guidelines support contraceptives if contraception also is desired; otherwise the 2017 guidelines recommend metformin as a first-line treatment.

“Agreement is uniform that healthy lifestyle management is first-line therapy for management of the associated obesity and metabolic disturbances, i.e., prior to and/or in conjunction with metformin therapy,” he noted.

In general, Dr. Rosenfield acknowledged that front-line clinicians cannot easily evaluate all early postmenarcheal girls for abnormal menstrual cycles. Instead, he advocated a “middle ground” approach between early diagnosis and potentially labeling a girl with a false positive diagnosis.

Postmenarcheal girls who are amenorrheic for 2 months could be assessed for signs of PCOS or pregnancy, and whether she is generally in good health, he said. “However, for example, if she remains amenorrheic for more than 90 days or if two successive periods are more than 2 months apart, laboratory screening would be reasonable.”

PCOS is “a diagnosis of exclusion for which referral to a specialist is advisable” to rule out other conditions such as non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinemia, endogenous Cushing syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, and virilizing tumors, said Dr. Rosenfield.

However, PCOS accounts for most cases of adolescent hyperandrogenism. The symptomatic treatment of early postmenarcheal girls at risk of PCOS is recommended to manage menstrual abnormality, hirsutism, acne, or obesity, and these girls should be reassessed by the time they finish high school after a 3-month treatment withdrawal period, he emphasized.

Dr. Rosenfield had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Rosenfield RL. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 June 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.017.

A trio of international expert recommendations mainly agree on essentials for the diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents, but some confusion persists, according to Robert L. Rosenfield, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

In a commentary published in the Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, Dr. Rosenfield, who convened one of the three conferences at which guidance was developed, noted that the three recommendations – published by the Pediatric Endocrine Society, the International Consortium of Paediatric Endocrinology, and the International PCOS Network in 2015, 2017, and 2018, respectively – “are fairly dense” and reviews have suggested a lack of agreement. His comments offer perspective and practice suggestions that follow the consensus of the recommendations.

“All the documents agree on the core diagnostic criteria for adolescent PCOS: otherwise unexplained evidence of ovulatory dysfunction, as indicated by menstrual abnormalities based on stage-appropriate standards, and evidence of an androgen excess disorder,” Dr. Rosenfield said.

The main differences among the recommendations from the three groups reflect tension between the value of an early diagnosis and the liabilities of a mistaken diagnosis in the context of attitudes about adolescent contraception. “These are issues not likely to be resolved easily, yet they are matters for every physician to consider in management of each case,” he said.

Dr. Rosenfield emphasized that clinicians must consider PCOS “in the general context of all causes of adolescent menstrual disturbances,” when evaluating a girl within 1-2 years of menarche who presents with a menstrual abnormality, hirsutism, and/or acne that has been resistant to topical treatment.

A key point on which the recommendations differ is whether further assessment is needed if the menstrual abnormality has persisted for 1 year (the 2018 recommendations) or 2 years (the 2015 and 2017 recommendations), Dr. Rosenfield explained. “What the conferees struggled with is differentiating how long after menarche a menstrual abnormality should persist to avoid confusing PCOS with normal immaturity of the menstrual cycle,” known as physiologic adolescent anovulation (PAA). “The degree of certainty is improved only modestly by waiting 2 years rather than 1 year to make a diagnosis.”

However, the three documents agree that girls suspected of having PCOS within the first 1-2 years after menarche should be evaluated at that time, and followed with a diagnosis of “at risk for PCOS” if the early test results are consistent with a PCOS diagnosis, he said.

Another point of difference among the groups is the extent to which hirsutism and acne represent clinical evidence of hyperandrogenism that justifies testing for biochemical hyperandrogenism, Dr. Rosenfield said.

“All three sets of adolescent PCOS recommendations agree that investigation for biochemical hyperandrogenism be initiated by measuring serum total and/or free testosterone by specialty assays with well-defined reference ranges,” he said.

However, “documentation of biochemical hyperandrogenism has been problematic because standard platform assays of testosterone give grossly inaccurate results.”

As said Dr. Rosenfield. Guidelines in the United States favor estrogen-progestin combined oral contraceptives as first-line therapy, while the international guidelines support contraceptives if contraception also is desired; otherwise the 2017 guidelines recommend metformin as a first-line treatment.

“Agreement is uniform that healthy lifestyle management is first-line therapy for management of the associated obesity and metabolic disturbances, i.e., prior to and/or in conjunction with metformin therapy,” he noted.

In general, Dr. Rosenfield acknowledged that front-line clinicians cannot easily evaluate all early postmenarcheal girls for abnormal menstrual cycles. Instead, he advocated a “middle ground” approach between early diagnosis and potentially labeling a girl with a false positive diagnosis.

Postmenarcheal girls who are amenorrheic for 2 months could be assessed for signs of PCOS or pregnancy, and whether she is generally in good health, he said. “However, for example, if she remains amenorrheic for more than 90 days or if two successive periods are more than 2 months apart, laboratory screening would be reasonable.”

PCOS is “a diagnosis of exclusion for which referral to a specialist is advisable” to rule out other conditions such as non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinemia, endogenous Cushing syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, and virilizing tumors, said Dr. Rosenfield.

However, PCOS accounts for most cases of adolescent hyperandrogenism. The symptomatic treatment of early postmenarcheal girls at risk of PCOS is recommended to manage menstrual abnormality, hirsutism, acne, or obesity, and these girls should be reassessed by the time they finish high school after a 3-month treatment withdrawal period, he emphasized.

Dr. Rosenfield had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Rosenfield RL. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 June 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.017.

A trio of international expert recommendations mainly agree on essentials for the diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents, but some confusion persists, according to Robert L. Rosenfield, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

In a commentary published in the Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, Dr. Rosenfield, who convened one of the three conferences at which guidance was developed, noted that the three recommendations – published by the Pediatric Endocrine Society, the International Consortium of Paediatric Endocrinology, and the International PCOS Network in 2015, 2017, and 2018, respectively – “are fairly dense” and reviews have suggested a lack of agreement. His comments offer perspective and practice suggestions that follow the consensus of the recommendations.

“All the documents agree on the core diagnostic criteria for adolescent PCOS: otherwise unexplained evidence of ovulatory dysfunction, as indicated by menstrual abnormalities based on stage-appropriate standards, and evidence of an androgen excess disorder,” Dr. Rosenfield said.

The main differences among the recommendations from the three groups reflect tension between the value of an early diagnosis and the liabilities of a mistaken diagnosis in the context of attitudes about adolescent contraception. “These are issues not likely to be resolved easily, yet they are matters for every physician to consider in management of each case,” he said.

Dr. Rosenfield emphasized that clinicians must consider PCOS “in the general context of all causes of adolescent menstrual disturbances,” when evaluating a girl within 1-2 years of menarche who presents with a menstrual abnormality, hirsutism, and/or acne that has been resistant to topical treatment.

A key point on which the recommendations differ is whether further assessment is needed if the menstrual abnormality has persisted for 1 year (the 2018 recommendations) or 2 years (the 2015 and 2017 recommendations), Dr. Rosenfield explained. “What the conferees struggled with is differentiating how long after menarche a menstrual abnormality should persist to avoid confusing PCOS with normal immaturity of the menstrual cycle,” known as physiologic adolescent anovulation (PAA). “The degree of certainty is improved only modestly by waiting 2 years rather than 1 year to make a diagnosis.”

However, the three documents agree that girls suspected of having PCOS within the first 1-2 years after menarche should be evaluated at that time, and followed with a diagnosis of “at risk for PCOS” if the early test results are consistent with a PCOS diagnosis, he said.

Another point of difference among the groups is the extent to which hirsutism and acne represent clinical evidence of hyperandrogenism that justifies testing for biochemical hyperandrogenism, Dr. Rosenfield said.

“All three sets of adolescent PCOS recommendations agree that investigation for biochemical hyperandrogenism be initiated by measuring serum total and/or free testosterone by specialty assays with well-defined reference ranges,” he said.

However, “documentation of biochemical hyperandrogenism has been problematic because standard platform assays of testosterone give grossly inaccurate results.”

As said Dr. Rosenfield. Guidelines in the United States favor estrogen-progestin combined oral contraceptives as first-line therapy, while the international guidelines support contraceptives if contraception also is desired; otherwise the 2017 guidelines recommend metformin as a first-line treatment.

“Agreement is uniform that healthy lifestyle management is first-line therapy for management of the associated obesity and metabolic disturbances, i.e., prior to and/or in conjunction with metformin therapy,” he noted.

In general, Dr. Rosenfield acknowledged that front-line clinicians cannot easily evaluate all early postmenarcheal girls for abnormal menstrual cycles. Instead, he advocated a “middle ground” approach between early diagnosis and potentially labeling a girl with a false positive diagnosis.

Postmenarcheal girls who are amenorrheic for 2 months could be assessed for signs of PCOS or pregnancy, and whether she is generally in good health, he said. “However, for example, if she remains amenorrheic for more than 90 days or if two successive periods are more than 2 months apart, laboratory screening would be reasonable.”

PCOS is “a diagnosis of exclusion for which referral to a specialist is advisable” to rule out other conditions such as non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinemia, endogenous Cushing syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, and virilizing tumors, said Dr. Rosenfield.

However, PCOS accounts for most cases of adolescent hyperandrogenism. The symptomatic treatment of early postmenarcheal girls at risk of PCOS is recommended to manage menstrual abnormality, hirsutism, acne, or obesity, and these girls should be reassessed by the time they finish high school after a 3-month treatment withdrawal period, he emphasized.

Dr. Rosenfield had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Rosenfield RL. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 June 29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.017.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY

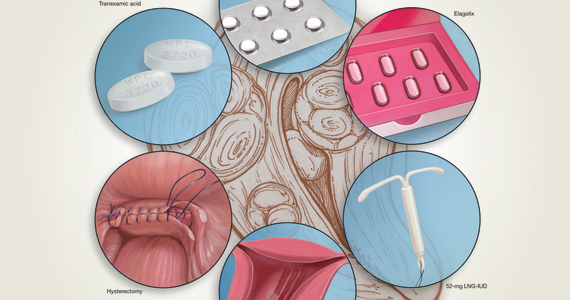

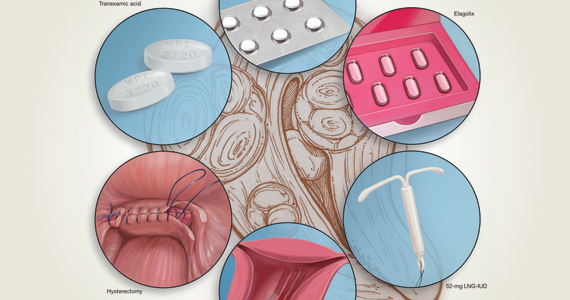

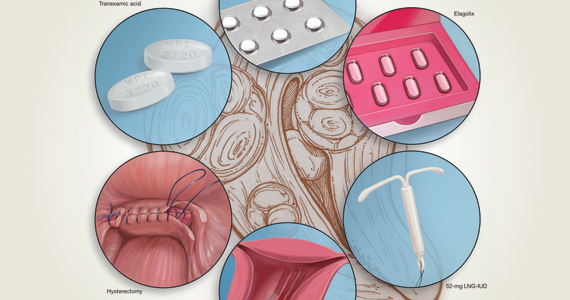

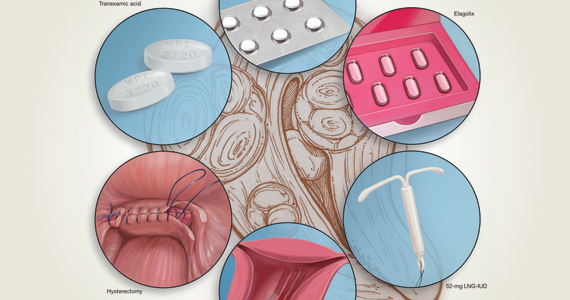

Heavy menstrual bleeding difficult to control in young patients with inherited platelet disorders

Physician consensus and a broadly effective treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding was not found among young patients with inherited platelet function disorders, according to the results of a retrospective chart review reported in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in girls with inherited platelet function disorders (IPFD) can be difficult to control despite ongoing follow-up and treatment changes, reported Christine M. Pennesi, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

They assessed 34 young women and girls (ages 9-25 years) diagnosed with IPFDs referred to gynecology and/or hematology at a tertiary care hospital between 2006 and 2018.

Billing codes were used to determine hormonal or nonhormonal treatments, and outcomes over a 1- to 2-year period were collected. The initial treatment was defined as the first treatment prescribed after referral. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a change in treatment method because of continued bleeding.

The majority (56%) of patients failed initial treatment (n = 19); among all 34 individuals followed in the study, an average of 2.7 total treatments were required.

Six patients (18%) remained uncontrolled despite numerous treatment changes (mean treatment changes, four; range, two to seven), and two patients (6%) remained uncontrolled because of noncompliance with treatment.

Overall, the researchers identified a 18% failure rate of successfully treatment of HMB in young women and girls with IPFDs over a 2-year follow-up period.

Of the 26 women who achieved control of HMB within 2-year follow-up, 54% (n = 14) were on hormonal treatments, 27% (n = 7) on nonhormonal treatments, 12% (n = 3) on combined treatments, and 8% (n = 2) on no treatment at time of control, the authors stated.

“The heterogeneity in treatments that were described in this study, clearly demonstrate that, in selecting treatment methods for HMB in young women, other considerations are often in play. This includes patient preference and need for contraception. Some patients or parents may have personal or religious objections to hormonal methods or worry about hormones in this young age group,” the researchers speculated.

“Appropriate counseling in these patients should include that it would not be unexpected for a patient to need more than one treatment before control of bleeding is achieved. This may help to alleviate the fear of teenagers when continued bleeding occurs after starting their initial treatment,” Dr. Pennesi and colleagues concluded.

One of the authors participated in funded trials and received funding from several pharmaceutical companies. The others reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pennesi CM et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Jun 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.019.

Physician consensus and a broadly effective treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding was not found among young patients with inherited platelet function disorders, according to the results of a retrospective chart review reported in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in girls with inherited platelet function disorders (IPFD) can be difficult to control despite ongoing follow-up and treatment changes, reported Christine M. Pennesi, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

They assessed 34 young women and girls (ages 9-25 years) diagnosed with IPFDs referred to gynecology and/or hematology at a tertiary care hospital between 2006 and 2018.

Billing codes were used to determine hormonal or nonhormonal treatments, and outcomes over a 1- to 2-year period were collected. The initial treatment was defined as the first treatment prescribed after referral. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a change in treatment method because of continued bleeding.

The majority (56%) of patients failed initial treatment (n = 19); among all 34 individuals followed in the study, an average of 2.7 total treatments were required.

Six patients (18%) remained uncontrolled despite numerous treatment changes (mean treatment changes, four; range, two to seven), and two patients (6%) remained uncontrolled because of noncompliance with treatment.

Overall, the researchers identified a 18% failure rate of successfully treatment of HMB in young women and girls with IPFDs over a 2-year follow-up period.

Of the 26 women who achieved control of HMB within 2-year follow-up, 54% (n = 14) were on hormonal treatments, 27% (n = 7) on nonhormonal treatments, 12% (n = 3) on combined treatments, and 8% (n = 2) on no treatment at time of control, the authors stated.

“The heterogeneity in treatments that were described in this study, clearly demonstrate that, in selecting treatment methods for HMB in young women, other considerations are often in play. This includes patient preference and need for contraception. Some patients or parents may have personal or religious objections to hormonal methods or worry about hormones in this young age group,” the researchers speculated.

“Appropriate counseling in these patients should include that it would not be unexpected for a patient to need more than one treatment before control of bleeding is achieved. This may help to alleviate the fear of teenagers when continued bleeding occurs after starting their initial treatment,” Dr. Pennesi and colleagues concluded.

One of the authors participated in funded trials and received funding from several pharmaceutical companies. The others reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pennesi CM et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Jun 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.019.

Physician consensus and a broadly effective treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding was not found among young patients with inherited platelet function disorders, according to the results of a retrospective chart review reported in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in girls with inherited platelet function disorders (IPFD) can be difficult to control despite ongoing follow-up and treatment changes, reported Christine M. Pennesi, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

They assessed 34 young women and girls (ages 9-25 years) diagnosed with IPFDs referred to gynecology and/or hematology at a tertiary care hospital between 2006 and 2018.

Billing codes were used to determine hormonal or nonhormonal treatments, and outcomes over a 1- to 2-year period were collected. The initial treatment was defined as the first treatment prescribed after referral. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a change in treatment method because of continued bleeding.

The majority (56%) of patients failed initial treatment (n = 19); among all 34 individuals followed in the study, an average of 2.7 total treatments were required.

Six patients (18%) remained uncontrolled despite numerous treatment changes (mean treatment changes, four; range, two to seven), and two patients (6%) remained uncontrolled because of noncompliance with treatment.

Overall, the researchers identified a 18% failure rate of successfully treatment of HMB in young women and girls with IPFDs over a 2-year follow-up period.

Of the 26 women who achieved control of HMB within 2-year follow-up, 54% (n = 14) were on hormonal treatments, 27% (n = 7) on nonhormonal treatments, 12% (n = 3) on combined treatments, and 8% (n = 2) on no treatment at time of control, the authors stated.

“The heterogeneity in treatments that were described in this study, clearly demonstrate that, in selecting treatment methods for HMB in young women, other considerations are often in play. This includes patient preference and need for contraception. Some patients or parents may have personal or religious objections to hormonal methods or worry about hormones in this young age group,” the researchers speculated.

“Appropriate counseling in these patients should include that it would not be unexpected for a patient to need more than one treatment before control of bleeding is achieved. This may help to alleviate the fear of teenagers when continued bleeding occurs after starting their initial treatment,” Dr. Pennesi and colleagues concluded.

One of the authors participated in funded trials and received funding from several pharmaceutical companies. The others reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Pennesi CM et al. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Jun 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.06.019.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY

Physician leadership: Racial disparities and racism. Where do we go from here?

The destructive toll COVID-19 has caused worldwide is devastating. In the United States, the disproportionate deaths of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people due to structural racism, amplified by economic adversity, is unacceptable. Meanwhile, the continued murder of Black people by those sworn to protect the public is abhorrent and can no longer be ignored. Black lives matter. These crises have rightly gripped our attention, and should galvanize physicians individually and collectively to use our privileged voices and relative power for justice. We must strive for engaged, passionate, and innovative leadership deliberately aimed toward antiracism and equity.

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the vast inequities in our country. It has highlighted the continued poor outcomes our health and health care systems create for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities. It also has demonstrated clearly that we are all connected—one large community, interdependent yet rife with differential power, privilege, and oppression. We must address these racial disparities—not only in the name of justice and good health for all but also because it is a moral and ethical imperative for us as physicians—and SARS-CoV-2 clearly shows us that it is in the best interest of everyone to do so.

First step: A deep dive look at systemic racism

What is first needed is an examination and acknowledgement by medicine and health care at large of the deeply entrenched roots of systemic and institutional racism in our profession and care systems, and their disproportionate and unjust impact on the health and livelihood of communities of color. The COVID-19 pandemic is only a recent example that highlights the perpetuation of a system that harms people of color. Racism, sexism, gender discrimination, economic and social injustice, religious persecution, and violence against women and children are age-old. We have yet to see health care institutions implement system-wide intersectional and antiracist practices to address them. Mandatory implicit bias training, policies for inclusion and diversity, and position statements are necessary first steps; however, they are not a panacea. They are insufficient to create the bold changes we need. The time for words has long passed. It is time to listen, to hear the cries of anguish and outrage, to examine our privileged position, to embrace change and discomfort, and most importantly to act, and to lead in dismantling the structures around us that perpetuate racial inequity.

How can we, as physicians and leaders, join in action and make an impact?

Dr. Camara Jones, past president of the American Public Health Association, describes 3 levels of racism:

- structural or systemic

- individual or personally mediated

- internalized.

Interventions at each level are important if we are to promote equity in health and health care. This framework can help us think about the following strategic initiatives.

Continue to: 1. Commit to becoming an antiracist and engage in independent study...

1. Commit to becoming antiracist and engage in independent study. This is an important first step as it will form the foundations for interventions—one cannot facilitate change without understanding the matter at hand. This step also may be the most personally challenging step forcing all of us to wrestle with discomfort, sadness, fear, guilt, and a host of other emotional responses. Remember that great change has never been born out of comfort, and the discomfort physicians may experience while unlearning racism and learning antiracism pales in comparison to what communities of color experience daily. We must actively work to unlearn the racist and anti-Black culture that is so deeply woven into every aspect of our existence.

Learn the history that was not given to us as kids in school. Read the brilliant literary works of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx artists and scholars on dismantling racism. Expand our vocabulary and knowledge of core concepts in racism, racial justice, and equity. Examine and reflect on our day-to-day practices. Be vocal in our commitment to antiracism—the time has passed for staying silent. If you are white, facilitate conversations about race with your white colleagues; the inherent power of racism relegates it to an issue that can never be on the table, but it is time to dismantle that power. Learn what acts of meaningful and intentional alliances are and when we need to give up power or privilege to a person of color. We also need to recognize that we as physicians, while leaders in many spaces, are not leaders in the powerful racial justice grassroots movements. We should learn from these movements, follow their lead, and use our privilege to uplift racial justice in our settings.

2. Embrace the current complexities with empathy and humility, finding ways to exercise our civic responsibility to the public with compassion. During the COVID-19 pandemic we have seen the devastation that social isolation, job loss, and illness can create. Suddenly those who could never have imagined themselves without food are waiting hours in their cars for food bank donations or are finding empty shelves in stores. Those who were not safe at home were suddenly imprisoned indefinitely in unsafe situations. Those who were comfortable, well-insured, and healthy are facing an invisible health threat, insecurity, fear, anxiety, and loss. Additionally, our civic institutions are failing. Those of us who always took our right to vote for granted are being forced to stand in hours’-long lines to exercise that right; while those who have been systematically disenfranchised are enduring even greater threats to their constitutional right to exercise their political power, disallowing them to speak for their families and communities and to vote for the justice they deserve. This may be an opportunity to stop blaming victims and recognize the toll that structural and systemic contributions to inequity have created over generations.

3. Meaningfully engage with and advocate for patients. In health and health care, we must begin to engage with the communities we serve and truly listen to their needs, desires, and barriers to care, and respond accordingly. Policies that try to address the social determinants of health without that engagement, and without the acknowledgement of the structural issues that cause them, however well-intentioned, are unlikely to accomplish their goals. We need to advocate as physicians and leaders in our settings for every policy, practice, and procedure to be scrutinized using an antiracist lens. To execute this, we need to:

- ask why clinic and hospital practices are built the way they are and how to make them more reflexive and responsive to individual patient’s needs

- examine what the disproportionate impacts might be on different groups of patients from a systems-level

- be ready to dismantle and/or rebuild something that is exacerbating disparate outcomes and experiences

- advocate for change that is built upon the narratives of patients and their communities.

We should include patients in the creation of hospital policies and guidelines in order to shift power toward them and to be transparent about how the system operates in order to facilitate trust and collaboration that centers patients and communities in the systems created to serve them.

Continue to: 4. Intentionally repair and build trust...

4. Intentionally repair and build trust. To create a safe environment, we must repair what we have broken and earn the trust of communities by uplifting their voices and redistributing our power to them in changing the systems and structures that have, for generations, kept Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people oppressed. Building trust requires first owning our histories of colonization, genocide, and slavery—now turned mass incarceration, debasement, and exploitation—that has existed for centuries. We as physicians need to do an honest examination of how we have eroded the trust of the very communities we care for since our profession’s creation. We need to acknowledge, as a white-dominant profession, the medical experimentation on and exploitation of Black and Brown bodies, and how this formed the foundation for a very valid deep distrust and fear of the medical establishment. We need to recognize how our inherent racial biases continue to feed this distrust, like when we don’t treat patients’ pain adequately or make them feel like we believe and listen to their needs and concerns. We must acknowledge our complicity in perpetuating the racial inequities in health, again highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Increase Black, Indigenous, and Latinx representation in physician and other health care professions’ workforce. Racism impacts not only patients but also our colleagues of color. The lack of racial diversity is a symptom of racism and a representation of the continued exclusion and devaluing of physicians of color. We must recognize this legacy of exclusion and facilitate intentional recruitment, retention, inclusion, and belonging of people of color into our workforce. Tokenism, the act of symbolically including one or few people from underrepresented groups, has been a weapon used by our workforce against physicians of color, resulting in isolation, “othering,” demoralization, and other deleterious impacts. We need to reverse this history and diversify our training programs and workforce to ensure justice in our own community.

6. Design multifaceted interventions. Multilevel problems require multilevel solutions. Interventions targeted solely at one level, while helpful, are unlikely to result in the larger scale changes our society needs to implement if we are to eradicate the impact of racism on health. We have long known that it is not just “preexisting conditions” or “poor” individual behaviors that lead to negative and disparate health outcomes—these are impacted by social and structural determinants much larger and more deleterious than that. It is critically important that we allocate and redistribute resources to create safe and affordable housing; childcare and preschool facilities; healthy, available, and affordable food; equitable and affordable educational opportunities; and a clean environment to support the health of all communities—not only those with the highest tax base. It is imperative that we strive to understand the lives of our fellow human beings who have been subjected to intergenerational social injustices and oppressions that have continued to place them at the margins of society. We need to center the lived experiences of communities of color in the design of multilevel interventions, especially Black and Indigenous communities. While we as physicians cannot individually impact education, economic, or food/environment systems, we can use our power to advocate for providing resources for the patients we care for and can create strategies within the health care system to address these needs in order to achieve optimal health. Robust and equitable social structures are the foundations for health, and ensuring equitable access to them is critical to reducing disparities.

Commit to lead

We must commit to unlearning our internalized racism, rebuilding relationships with communities of color, and engaging in antiracist practices. As a profession dedicated to healing, we have an obligation to be leaders in advocating for these changes, and dismantling the inequitable structure of our health care system.

Our challenge now is to articulate solutions. While antiracism should be informed by the lived experiences of communities of color, the work of antiracism is not their responsibility. In fact, it is the responsibility of our white-dominated systems and institutions to change.

There are some solutions that are easier to enumerate because they have easily measurable outcomes or activities, such as:

- collecting data transparently

- identifying inequities in access, treatment, and care

- conducting rigorous root cause analysis of those barriers to care

- increasing diverse racial and gender representation on decision-making bodies, from board rooms to committees, from leadership teams to research participants

- redistribute power by paving the way for underrepresented colleagues to participate in clinical, administrative, educational, executive, and health policy spaces

- mentoring new leaders who come from marginalized communities.

Every patient deserves our expertise and access to high-quality care. We should review our patient panels to ensure we are taking steps personally to be just and eliminate disparities, and we should monitor the results of those efforts.

Continue to: Be open to solutions that may make us “uncomfortable”...

Be open to solutions that may make us “uncomfortable”

There are other solutions, perhaps those that would be more effective on a larger scale, which may be harder to measure using our traditional ways of inquiry or measurement. Solutions that may create discomfort, anger, or fear for those who have held their power or positions for a long time. We need to begin to engage in developing, cultivating, and valuing innovative strategies that produce equally valid knowledge, evidence, and solutions without engaging in a randomized controlled trial. We need to reinvent the way inquiry, investigation, and implementation are done, and utilize novel, justice-informed strategies that include real-world evidence to produce results that are applicable to all (not just those willing to participate in sponsored trials). Only then will we be able to provide equitable health outcomes for all.

We also must accept responsibility for the past and humbly ask communities to work with us as we struggle to eliminate racism and dehumanization of Black lives by calling out our actions or inaction, recognizing the impact of our privileged status, and stepping down or stepping aside to allow others to lead. Sometimes it is as simple as turning off the Zoom camera so others can talk. By redistributing power and focusing this work upon the narratives of marginalized communities, we can improve our system for everyone. We must lead with action within our practices and systems; become advocates within our communities, institutions, and profession; strategize and organize interventions at both structural and individual levels to first recognize and name—then change—the systems; and unlearn behaviors that perpetuate racism.

Inaction is shirking our responsibility among the medical community

Benign inaction and unintentional acquiescence with “the way things are and have always been” abdicates our responsibility as physicians to improve the health of our patients and our communities. The modern Hippocratic Oath reminds us: “I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.” We have a professional and ethical responsibility to ensure health equity, and thus racial equity. As physicians, as healers, as leaders we must address racial inequities at all levels as we commit to improving the health of our nation. We can no longer stand silent in the face of the violence, brutality, and injustices our patients, friends, family, neighbors, communities, and society as a whole live through daily. It is unjust and inhumane to do so.

To be silent is to be complicit. As Gandhi said so long ago, we must “be the change we wish to see in the world.” And as Ijeoma Olua teaches us, “Anti-racism is the commitment to fight racism wherever you find it, including in yourself. And it’s the only way forward.”

- “So You Want to Talk about Race” Ijeoma Oluo

- “How to Be an Antiracist” Ibram X. Kendi

- “Between the World and Me” Ta-Nehisi Coates

- A conversation on race and privilege (Angela Davis and Jane Elliot) https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=S0jf8D5WHoo

- Uncomfortable conversations with a Black man (Emmanuel Acho) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8jUA7JBkF4

Antiracism – defined as the work of actively opposing racism by advocating for changes in political, economic, and social life. Antiracism tends to be an individualized approach, and set up in opposition to individual racist behaviors and impacts

Black Lives Matter – a political movement to address systemic and state violence against African Americans. Per the Black Lives Matter organizers: “In 2013, three radical Black organizers—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi—created a Black-centered political will and movement building project called BlackLivesMatter. It was in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, George Zimmerman. The project is now a member-led global network of more than 40 chapters. Members organize and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes. Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ humanity, our contributions to this society, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.”

Implicit bias – also known as unconscious or hidden bias, implicit biases are negative associations that people unknowingly hold. They are expressed automatically, without conscious awareness. Many studies have indicated that implicit biases affect individuals’ attitudes and actions, thus creating real-world implications, even though individuals may not even be aware that those biases exist within themselves. Notably, implicit biases have been shown to trump individuals stated commitments to equality and fairness, thereby producing behavior that diverges from the explicit attitudes that many people profess.

Othering – view or treat (a person or group of people) as intrinsically different from and alien to oneself. (From https://lexico.com.)

For a full glossary of terms, visit RacialEquityTools.org (https://www.racialequitytools.org/glossary#anti-black)

The destructive toll COVID-19 has caused worldwide is devastating. In the United States, the disproportionate deaths of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people due to structural racism, amplified by economic adversity, is unacceptable. Meanwhile, the continued murder of Black people by those sworn to protect the public is abhorrent and can no longer be ignored. Black lives matter. These crises have rightly gripped our attention, and should galvanize physicians individually and collectively to use our privileged voices and relative power for justice. We must strive for engaged, passionate, and innovative leadership deliberately aimed toward antiracism and equity.

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the vast inequities in our country. It has highlighted the continued poor outcomes our health and health care systems create for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities. It also has demonstrated clearly that we are all connected—one large community, interdependent yet rife with differential power, privilege, and oppression. We must address these racial disparities—not only in the name of justice and good health for all but also because it is a moral and ethical imperative for us as physicians—and SARS-CoV-2 clearly shows us that it is in the best interest of everyone to do so.

First step: A deep dive look at systemic racism

What is first needed is an examination and acknowledgement by medicine and health care at large of the deeply entrenched roots of systemic and institutional racism in our profession and care systems, and their disproportionate and unjust impact on the health and livelihood of communities of color. The COVID-19 pandemic is only a recent example that highlights the perpetuation of a system that harms people of color. Racism, sexism, gender discrimination, economic and social injustice, religious persecution, and violence against women and children are age-old. We have yet to see health care institutions implement system-wide intersectional and antiracist practices to address them. Mandatory implicit bias training, policies for inclusion and diversity, and position statements are necessary first steps; however, they are not a panacea. They are insufficient to create the bold changes we need. The time for words has long passed. It is time to listen, to hear the cries of anguish and outrage, to examine our privileged position, to embrace change and discomfort, and most importantly to act, and to lead in dismantling the structures around us that perpetuate racial inequity.

How can we, as physicians and leaders, join in action and make an impact?

Dr. Camara Jones, past president of the American Public Health Association, describes 3 levels of racism:

- structural or systemic

- individual or personally mediated

- internalized.

Interventions at each level are important if we are to promote equity in health and health care. This framework can help us think about the following strategic initiatives.

Continue to: 1. Commit to becoming an antiracist and engage in independent study...

1. Commit to becoming antiracist and engage in independent study. This is an important first step as it will form the foundations for interventions—one cannot facilitate change without understanding the matter at hand. This step also may be the most personally challenging step forcing all of us to wrestle with discomfort, sadness, fear, guilt, and a host of other emotional responses. Remember that great change has never been born out of comfort, and the discomfort physicians may experience while unlearning racism and learning antiracism pales in comparison to what communities of color experience daily. We must actively work to unlearn the racist and anti-Black culture that is so deeply woven into every aspect of our existence.

Learn the history that was not given to us as kids in school. Read the brilliant literary works of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx artists and scholars on dismantling racism. Expand our vocabulary and knowledge of core concepts in racism, racial justice, and equity. Examine and reflect on our day-to-day practices. Be vocal in our commitment to antiracism—the time has passed for staying silent. If you are white, facilitate conversations about race with your white colleagues; the inherent power of racism relegates it to an issue that can never be on the table, but it is time to dismantle that power. Learn what acts of meaningful and intentional alliances are and when we need to give up power or privilege to a person of color. We also need to recognize that we as physicians, while leaders in many spaces, are not leaders in the powerful racial justice grassroots movements. We should learn from these movements, follow their lead, and use our privilege to uplift racial justice in our settings.

2. Embrace the current complexities with empathy and humility, finding ways to exercise our civic responsibility to the public with compassion. During the COVID-19 pandemic we have seen the devastation that social isolation, job loss, and illness can create. Suddenly those who could never have imagined themselves without food are waiting hours in their cars for food bank donations or are finding empty shelves in stores. Those who were not safe at home were suddenly imprisoned indefinitely in unsafe situations. Those who were comfortable, well-insured, and healthy are facing an invisible health threat, insecurity, fear, anxiety, and loss. Additionally, our civic institutions are failing. Those of us who always took our right to vote for granted are being forced to stand in hours’-long lines to exercise that right; while those who have been systematically disenfranchised are enduring even greater threats to their constitutional right to exercise their political power, disallowing them to speak for their families and communities and to vote for the justice they deserve. This may be an opportunity to stop blaming victims and recognize the toll that structural and systemic contributions to inequity have created over generations.

3. Meaningfully engage with and advocate for patients. In health and health care, we must begin to engage with the communities we serve and truly listen to their needs, desires, and barriers to care, and respond accordingly. Policies that try to address the social determinants of health without that engagement, and without the acknowledgement of the structural issues that cause them, however well-intentioned, are unlikely to accomplish their goals. We need to advocate as physicians and leaders in our settings for every policy, practice, and procedure to be scrutinized using an antiracist lens. To execute this, we need to:

- ask why clinic and hospital practices are built the way they are and how to make them more reflexive and responsive to individual patient’s needs

- examine what the disproportionate impacts might be on different groups of patients from a systems-level

- be ready to dismantle and/or rebuild something that is exacerbating disparate outcomes and experiences

- advocate for change that is built upon the narratives of patients and their communities.

We should include patients in the creation of hospital policies and guidelines in order to shift power toward them and to be transparent about how the system operates in order to facilitate trust and collaboration that centers patients and communities in the systems created to serve them.

Continue to: 4. Intentionally repair and build trust...

4. Intentionally repair and build trust. To create a safe environment, we must repair what we have broken and earn the trust of communities by uplifting their voices and redistributing our power to them in changing the systems and structures that have, for generations, kept Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people oppressed. Building trust requires first owning our histories of colonization, genocide, and slavery—now turned mass incarceration, debasement, and exploitation—that has existed for centuries. We as physicians need to do an honest examination of how we have eroded the trust of the very communities we care for since our profession’s creation. We need to acknowledge, as a white-dominant profession, the medical experimentation on and exploitation of Black and Brown bodies, and how this formed the foundation for a very valid deep distrust and fear of the medical establishment. We need to recognize how our inherent racial biases continue to feed this distrust, like when we don’t treat patients’ pain adequately or make them feel like we believe and listen to their needs and concerns. We must acknowledge our complicity in perpetuating the racial inequities in health, again highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Increase Black, Indigenous, and Latinx representation in physician and other health care professions’ workforce. Racism impacts not only patients but also our colleagues of color. The lack of racial diversity is a symptom of racism and a representation of the continued exclusion and devaluing of physicians of color. We must recognize this legacy of exclusion and facilitate intentional recruitment, retention, inclusion, and belonging of people of color into our workforce. Tokenism, the act of symbolically including one or few people from underrepresented groups, has been a weapon used by our workforce against physicians of color, resulting in isolation, “othering,” demoralization, and other deleterious impacts. We need to reverse this history and diversify our training programs and workforce to ensure justice in our own community.

6. Design multifaceted interventions. Multilevel problems require multilevel solutions. Interventions targeted solely at one level, while helpful, are unlikely to result in the larger scale changes our society needs to implement if we are to eradicate the impact of racism on health. We have long known that it is not just “preexisting conditions” or “poor” individual behaviors that lead to negative and disparate health outcomes—these are impacted by social and structural determinants much larger and more deleterious than that. It is critically important that we allocate and redistribute resources to create safe and affordable housing; childcare and preschool facilities; healthy, available, and affordable food; equitable and affordable educational opportunities; and a clean environment to support the health of all communities—not only those with the highest tax base. It is imperative that we strive to understand the lives of our fellow human beings who have been subjected to intergenerational social injustices and oppressions that have continued to place them at the margins of society. We need to center the lived experiences of communities of color in the design of multilevel interventions, especially Black and Indigenous communities. While we as physicians cannot individually impact education, economic, or food/environment systems, we can use our power to advocate for providing resources for the patients we care for and can create strategies within the health care system to address these needs in order to achieve optimal health. Robust and equitable social structures are the foundations for health, and ensuring equitable access to them is critical to reducing disparities.

Commit to lead

We must commit to unlearning our internalized racism, rebuilding relationships with communities of color, and engaging in antiracist practices. As a profession dedicated to healing, we have an obligation to be leaders in advocating for these changes, and dismantling the inequitable structure of our health care system.

Our challenge now is to articulate solutions. While antiracism should be informed by the lived experiences of communities of color, the work of antiracism is not their responsibility. In fact, it is the responsibility of our white-dominated systems and institutions to change.

There are some solutions that are easier to enumerate because they have easily measurable outcomes or activities, such as:

- collecting data transparently

- identifying inequities in access, treatment, and care

- conducting rigorous root cause analysis of those barriers to care

- increasing diverse racial and gender representation on decision-making bodies, from board rooms to committees, from leadership teams to research participants

- redistribute power by paving the way for underrepresented colleagues to participate in clinical, administrative, educational, executive, and health policy spaces

- mentoring new leaders who come from marginalized communities.

Every patient deserves our expertise and access to high-quality care. We should review our patient panels to ensure we are taking steps personally to be just and eliminate disparities, and we should monitor the results of those efforts.

Continue to: Be open to solutions that may make us “uncomfortable”...

Be open to solutions that may make us “uncomfortable”

There are other solutions, perhaps those that would be more effective on a larger scale, which may be harder to measure using our traditional ways of inquiry or measurement. Solutions that may create discomfort, anger, or fear for those who have held their power or positions for a long time. We need to begin to engage in developing, cultivating, and valuing innovative strategies that produce equally valid knowledge, evidence, and solutions without engaging in a randomized controlled trial. We need to reinvent the way inquiry, investigation, and implementation are done, and utilize novel, justice-informed strategies that include real-world evidence to produce results that are applicable to all (not just those willing to participate in sponsored trials). Only then will we be able to provide equitable health outcomes for all.

We also must accept responsibility for the past and humbly ask communities to work with us as we struggle to eliminate racism and dehumanization of Black lives by calling out our actions or inaction, recognizing the impact of our privileged status, and stepping down or stepping aside to allow others to lead. Sometimes it is as simple as turning off the Zoom camera so others can talk. By redistributing power and focusing this work upon the narratives of marginalized communities, we can improve our system for everyone. We must lead with action within our practices and systems; become advocates within our communities, institutions, and profession; strategize and organize interventions at both structural and individual levels to first recognize and name—then change—the systems; and unlearn behaviors that perpetuate racism.

Inaction is shirking our responsibility among the medical community

Benign inaction and unintentional acquiescence with “the way things are and have always been” abdicates our responsibility as physicians to improve the health of our patients and our communities. The modern Hippocratic Oath reminds us: “I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.” We have a professional and ethical responsibility to ensure health equity, and thus racial equity. As physicians, as healers, as leaders we must address racial inequities at all levels as we commit to improving the health of our nation. We can no longer stand silent in the face of the violence, brutality, and injustices our patients, friends, family, neighbors, communities, and society as a whole live through daily. It is unjust and inhumane to do so.

To be silent is to be complicit. As Gandhi said so long ago, we must “be the change we wish to see in the world.” And as Ijeoma Olua teaches us, “Anti-racism is the commitment to fight racism wherever you find it, including in yourself. And it’s the only way forward.”

- “So You Want to Talk about Race” Ijeoma Oluo

- “How to Be an Antiracist” Ibram X. Kendi

- “Between the World and Me” Ta-Nehisi Coates

- A conversation on race and privilege (Angela Davis and Jane Elliot) https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=S0jf8D5WHoo

- Uncomfortable conversations with a Black man (Emmanuel Acho) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8jUA7JBkF4

Antiracism – defined as the work of actively opposing racism by advocating for changes in political, economic, and social life. Antiracism tends to be an individualized approach, and set up in opposition to individual racist behaviors and impacts