User login

Emergency gout admission increase is ‘call to arms’

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – The rate of emergency hospital admissions for gout in England has seen a 59% increase over the past decade, while that of rheumatoid arthritis has halved, it was reported at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Over an approximate 10-year period (2006-2017), the incidence rate of unplanned gout admissions increased from 7.9 to 12.5 admissions per 100,000 of the population. This represented an increase from 0.023% to 0.032% of all hospital admissions during the period.

To put that into perspective, unplanned admissions for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), decreased from 8.6 to 4.3 admissions per 100,000 of the population, said Mark D. Russell, MD, a rheumatology registrar at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital in London.

Furthermore, primary care prescriptions for common gout medications have seen a dramatic increase over the same time period in England; allopurinol prescriptions are up 72%, there’s been a 166% increase in colchicine prescriptions, and a 20-fold increase in febuxostat (Uloric) prescriptions since data became available for its in 2010.

“Gout’s very much a treatable condition,” Dr. Russell said, but with 82% of all gout admissions being unplanned, “there’s clearly more to do; this should be a call to arms for rheumatologists to help reduce the in-patient burden of this condition.”

The mean length of hospital stay was estimated at 6.6 days, with the median being 3.2 days. Gout accounted for just under 350,000 hospital bed days from 2006 to 2017, and with the cost of a single gout admission being anything from £850 up to £5,600, it constitutes a significant burden for the country’s National Health Service.

But what can be done? Would a “door-to-needle time campaign” help? So that when patients attend the emergency department they are assessed rapidly and treated accordingly? Dr. Russell queried.

Education could be the key, was the consensus during the discussion following his presentation. Education, and not just of those affected by the condition, but also of the family physicians who seem to have a “knee-jerk reaction” to prescribe medications, and not always appropriately. Even hospital staff may need help in differentiating gout from other emergency presentations, with some admitting patients suspecting infection or wrongly discharging them.

Pharmacist-led gout clinics

Another approach to try to avoid emergency hospital visits could be better management and perhaps setting up specialist gout clinics. Such clinics have already been piloted, and rheumatology pharmacist Jane Whiteman shared her experience of setting up a monthly, pharmacist-led gout clinic in a separate presentation.

Dr. Whiteman, who works at Royal Victoria Hospital, part of the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust in Ireland, presented data on 52 patients who were seen at the clinic between June 2015 and May 2017. The total number of patient visits was 87, with an average of 1.7 visits per patient.

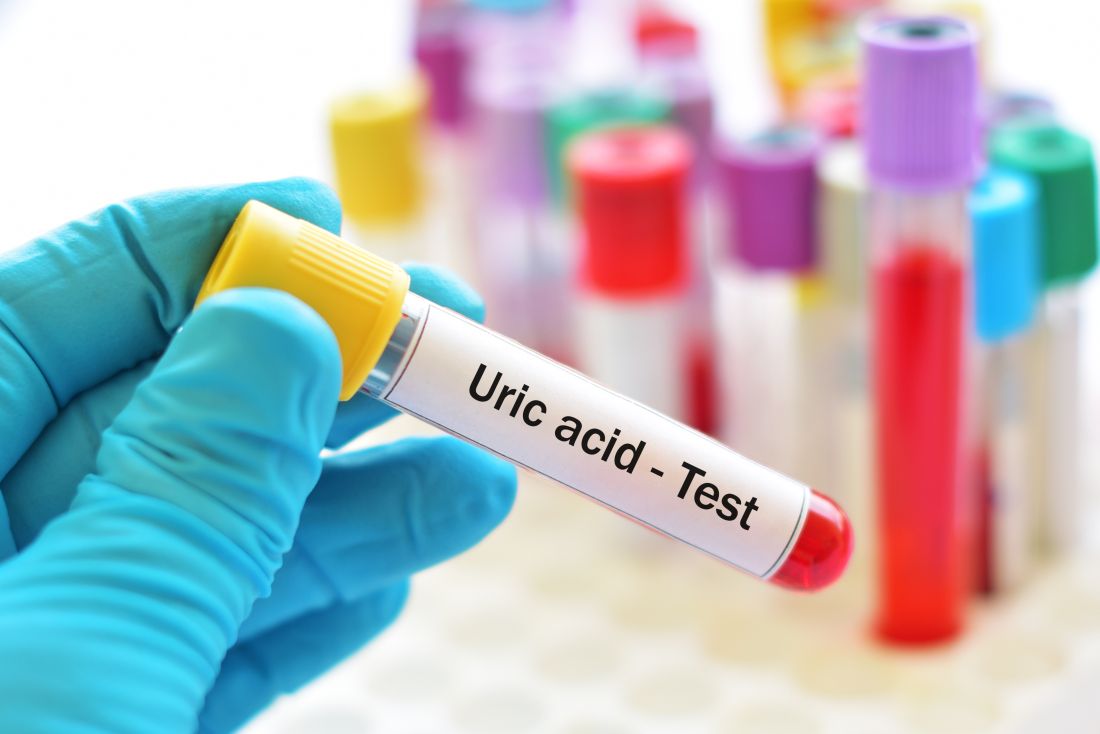

Of 38 patients who were discharged from the clinic, 29 (76%) had met target levels of serum uric acid, which guidelines from the British Society for Rheumatology set at less than 0.3 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) and those from the European League of Rheumatism set at less than 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL).

It is important to reduce serum uric acid levels, Dr. Whiteman explained. “Gout occurs when serum uric acid rises and urate crystals reach their saturation point in the serum and start to crystallize out into the joints and into the tissues,” she said. “It’s a progressive disease that usually starts in one joint, but if the serum uric acid isn’t controlled then it can go on to affect a number of joints,” and cause chronic arthritis, among other potentially serious conditions, and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular and renal disease.

“Studies across the world have shown that gout is not well looked after; patient adherence to treatment is very poor,” Dr. Whiteman said. “Among all the chronic diseases it has the lowest adherence to treatment,” she added, noting that one study showed just one-fifth of patients remained on gout medication at 1 year.

Patient education is an important part of the clinic’s services, as when people are asymptomatic and between bouts of gout, they perhaps do not realize that they still need to take their medication. Education thus needs to include talking about their diet and lifestyle, providing information on medication, and why it is important to keep their serum uric acid levels in check.

After patients’ initial referral to the clinic, they are followed up by the clinic every month until their serum urate levels are below the 0.3 mmol/L target. They can then be discharged and monitored by their family physician.

Postdischarge, Dr. Whiteman and her colleagues found that 22 (76%) of the 29 patients who had met their target levels of serum uric acid later had serum uric acid tested at least once, showing an average level of 0.29 mmol/L at follow-up. This reassuring result occurred perhaps because of a majority of patients (79%) who were still being prescribed, and presumably taking, urate-lowering therapy. Seven patients did not undergo follow-up serum uric acid testing because they had died (one), were in the hospital (one), were not taking medication because they had made diet or lifestyle changes (three), or had their treatment on hold (two).

“I think the gout clinic has been a success; it has addressed barriers to optimal management through education of the patient,” Dr. Whiteman said.

Both presenters had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Russel M et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.186; Whiteman J, et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.215.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – The rate of emergency hospital admissions for gout in England has seen a 59% increase over the past decade, while that of rheumatoid arthritis has halved, it was reported at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Over an approximate 10-year period (2006-2017), the incidence rate of unplanned gout admissions increased from 7.9 to 12.5 admissions per 100,000 of the population. This represented an increase from 0.023% to 0.032% of all hospital admissions during the period.

To put that into perspective, unplanned admissions for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), decreased from 8.6 to 4.3 admissions per 100,000 of the population, said Mark D. Russell, MD, a rheumatology registrar at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital in London.

Furthermore, primary care prescriptions for common gout medications have seen a dramatic increase over the same time period in England; allopurinol prescriptions are up 72%, there’s been a 166% increase in colchicine prescriptions, and a 20-fold increase in febuxostat (Uloric) prescriptions since data became available for its in 2010.

“Gout’s very much a treatable condition,” Dr. Russell said, but with 82% of all gout admissions being unplanned, “there’s clearly more to do; this should be a call to arms for rheumatologists to help reduce the in-patient burden of this condition.”

The mean length of hospital stay was estimated at 6.6 days, with the median being 3.2 days. Gout accounted for just under 350,000 hospital bed days from 2006 to 2017, and with the cost of a single gout admission being anything from £850 up to £5,600, it constitutes a significant burden for the country’s National Health Service.

But what can be done? Would a “door-to-needle time campaign” help? So that when patients attend the emergency department they are assessed rapidly and treated accordingly? Dr. Russell queried.

Education could be the key, was the consensus during the discussion following his presentation. Education, and not just of those affected by the condition, but also of the family physicians who seem to have a “knee-jerk reaction” to prescribe medications, and not always appropriately. Even hospital staff may need help in differentiating gout from other emergency presentations, with some admitting patients suspecting infection or wrongly discharging them.

Pharmacist-led gout clinics

Another approach to try to avoid emergency hospital visits could be better management and perhaps setting up specialist gout clinics. Such clinics have already been piloted, and rheumatology pharmacist Jane Whiteman shared her experience of setting up a monthly, pharmacist-led gout clinic in a separate presentation.

Dr. Whiteman, who works at Royal Victoria Hospital, part of the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust in Ireland, presented data on 52 patients who were seen at the clinic between June 2015 and May 2017. The total number of patient visits was 87, with an average of 1.7 visits per patient.

Of 38 patients who were discharged from the clinic, 29 (76%) had met target levels of serum uric acid, which guidelines from the British Society for Rheumatology set at less than 0.3 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) and those from the European League of Rheumatism set at less than 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL).

It is important to reduce serum uric acid levels, Dr. Whiteman explained. “Gout occurs when serum uric acid rises and urate crystals reach their saturation point in the serum and start to crystallize out into the joints and into the tissues,” she said. “It’s a progressive disease that usually starts in one joint, but if the serum uric acid isn’t controlled then it can go on to affect a number of joints,” and cause chronic arthritis, among other potentially serious conditions, and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular and renal disease.

“Studies across the world have shown that gout is not well looked after; patient adherence to treatment is very poor,” Dr. Whiteman said. “Among all the chronic diseases it has the lowest adherence to treatment,” she added, noting that one study showed just one-fifth of patients remained on gout medication at 1 year.

Patient education is an important part of the clinic’s services, as when people are asymptomatic and between bouts of gout, they perhaps do not realize that they still need to take their medication. Education thus needs to include talking about their diet and lifestyle, providing information on medication, and why it is important to keep their serum uric acid levels in check.

After patients’ initial referral to the clinic, they are followed up by the clinic every month until their serum urate levels are below the 0.3 mmol/L target. They can then be discharged and monitored by their family physician.

Postdischarge, Dr. Whiteman and her colleagues found that 22 (76%) of the 29 patients who had met their target levels of serum uric acid later had serum uric acid tested at least once, showing an average level of 0.29 mmol/L at follow-up. This reassuring result occurred perhaps because of a majority of patients (79%) who were still being prescribed, and presumably taking, urate-lowering therapy. Seven patients did not undergo follow-up serum uric acid testing because they had died (one), were in the hospital (one), were not taking medication because they had made diet or lifestyle changes (three), or had their treatment on hold (two).

“I think the gout clinic has been a success; it has addressed barriers to optimal management through education of the patient,” Dr. Whiteman said.

Both presenters had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Russel M et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.186; Whiteman J, et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.215.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – The rate of emergency hospital admissions for gout in England has seen a 59% increase over the past decade, while that of rheumatoid arthritis has halved, it was reported at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Over an approximate 10-year period (2006-2017), the incidence rate of unplanned gout admissions increased from 7.9 to 12.5 admissions per 100,000 of the population. This represented an increase from 0.023% to 0.032% of all hospital admissions during the period.

To put that into perspective, unplanned admissions for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), decreased from 8.6 to 4.3 admissions per 100,000 of the population, said Mark D. Russell, MD, a rheumatology registrar at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital in London.

Furthermore, primary care prescriptions for common gout medications have seen a dramatic increase over the same time period in England; allopurinol prescriptions are up 72%, there’s been a 166% increase in colchicine prescriptions, and a 20-fold increase in febuxostat (Uloric) prescriptions since data became available for its in 2010.

“Gout’s very much a treatable condition,” Dr. Russell said, but with 82% of all gout admissions being unplanned, “there’s clearly more to do; this should be a call to arms for rheumatologists to help reduce the in-patient burden of this condition.”

The mean length of hospital stay was estimated at 6.6 days, with the median being 3.2 days. Gout accounted for just under 350,000 hospital bed days from 2006 to 2017, and with the cost of a single gout admission being anything from £850 up to £5,600, it constitutes a significant burden for the country’s National Health Service.

But what can be done? Would a “door-to-needle time campaign” help? So that when patients attend the emergency department they are assessed rapidly and treated accordingly? Dr. Russell queried.

Education could be the key, was the consensus during the discussion following his presentation. Education, and not just of those affected by the condition, but also of the family physicians who seem to have a “knee-jerk reaction” to prescribe medications, and not always appropriately. Even hospital staff may need help in differentiating gout from other emergency presentations, with some admitting patients suspecting infection or wrongly discharging them.

Pharmacist-led gout clinics

Another approach to try to avoid emergency hospital visits could be better management and perhaps setting up specialist gout clinics. Such clinics have already been piloted, and rheumatology pharmacist Jane Whiteman shared her experience of setting up a monthly, pharmacist-led gout clinic in a separate presentation.

Dr. Whiteman, who works at Royal Victoria Hospital, part of the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust in Ireland, presented data on 52 patients who were seen at the clinic between June 2015 and May 2017. The total number of patient visits was 87, with an average of 1.7 visits per patient.

Of 38 patients who were discharged from the clinic, 29 (76%) had met target levels of serum uric acid, which guidelines from the British Society for Rheumatology set at less than 0.3 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) and those from the European League of Rheumatism set at less than 0.36 mmol/L (6 mg/dL).

It is important to reduce serum uric acid levels, Dr. Whiteman explained. “Gout occurs when serum uric acid rises and urate crystals reach their saturation point in the serum and start to crystallize out into the joints and into the tissues,” she said. “It’s a progressive disease that usually starts in one joint, but if the serum uric acid isn’t controlled then it can go on to affect a number of joints,” and cause chronic arthritis, among other potentially serious conditions, and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular and renal disease.

“Studies across the world have shown that gout is not well looked after; patient adherence to treatment is very poor,” Dr. Whiteman said. “Among all the chronic diseases it has the lowest adherence to treatment,” she added, noting that one study showed just one-fifth of patients remained on gout medication at 1 year.

Patient education is an important part of the clinic’s services, as when people are asymptomatic and between bouts of gout, they perhaps do not realize that they still need to take their medication. Education thus needs to include talking about their diet and lifestyle, providing information on medication, and why it is important to keep their serum uric acid levels in check.

After patients’ initial referral to the clinic, they are followed up by the clinic every month until their serum urate levels are below the 0.3 mmol/L target. They can then be discharged and monitored by their family physician.

Postdischarge, Dr. Whiteman and her colleagues found that 22 (76%) of the 29 patients who had met their target levels of serum uric acid later had serum uric acid tested at least once, showing an average level of 0.29 mmol/L at follow-up. This reassuring result occurred perhaps because of a majority of patients (79%) who were still being prescribed, and presumably taking, urate-lowering therapy. Seven patients did not undergo follow-up serum uric acid testing because they had died (one), were in the hospital (one), were not taking medication because they had made diet or lifestyle changes (three), or had their treatment on hold (two).

“I think the gout clinic has been a success; it has addressed barriers to optimal management through education of the patient,” Dr. Whiteman said.

Both presenters had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Russel M et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.186; Whiteman J, et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.215.

AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rate of emergency hospital admissions for gout in England increased by 59%, from 7.9 to 12.5 admissions per 100,000 of the population; 76% of patients attending a pharmacist-led gout clinic achieved target serum uric acid levels.

Study details: An analysis of National Health Service data from April 2006 to March 2017 on hospital admissions for gout and primary care prescription data and a separate study of 52 patients attending a pharmacist-led gout clinic.

Disclosures: Both presenters had nothing to disclose.

Sources: Russell M et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.186; Whiteman J et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.215.

Allopurinol dose not escalated enough to reduce mortality

An allopurinol dose escalation strategy for patients with gout was associated with a small increase in all-cause mortality when compared against a static dosing strategy, results of a recent observational study show.

Allopurinol dose escalation was also associated with small, but not statistically significant, increases in cardiovascular- and cancer-related mortality, investigators said in a report published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Dr. Coburn and his colleagues had hypothesized that dose escalation would instead be associated with lower cause-specific cardiovascular and cancer mortality, compared with static dosing, according to the report.

However, a minority of dose-escalated patients achieved serum urate goal. Thus, inadequate escalation may have obscured any potential mortality benefit associated with the treatment strategy, the investigators suggested.

Current guidelines recommend starting gout patients on a low dose of allopurinol (100 mg/day or less) and then titrating up the dose slowly.

“While randomized, controlled trials of urate-lowering therapies have used static dosing strategies, such strategies are suboptimal and should now be considered unethical,” they wrote.

The researchers’ 10-year, observational, active-comparator study included 6,428 U.S. veterans with gout receiving allopurinol according to a dose escalation strategy, and 6,428 matched individuals not treated with an escalation approach.

Dose escalators had significantly increased all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.17). Similar, but not statistically significant, effect sizes were seen for cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.97-1.21) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.88-1.27), the investigators reported.

However, only 10% of dose-escalation patients received allopurinol in doses exceeding 300 mg daily, and only about one-third achieved a serum urate goal of less than 6.0 mg/dL after 2 years, they found.

“Patients receiving urate-lowering therapy dose escalation were only rarely escalated to levels typically required for proper gout control,” the investigators said.

Inadequate dose escalation amounts to “clinical inertia” that limited the ability of the study to show how optimal dose escalation may affect mortality, the investigators said.

“This appears to be particularly relevant since gout patients receiving dose escalation and achieving serum urate goal appeared to have lower cardiovascular mortality in sensitivity analyses,” they noted.

There was a 7% reduction in cardiovascular mortality in a sensitivity analysis limited to dose escalators who achieved goal, though that finding did not reach statistical significance, Dr. Coburn and his coinvestigators reported (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.76-1.14).

“Taken together, these results add to the persistent uncertainty regarding the role of urate-lowering therapy in reducing mortality risk,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Health Professional Research Preceptorship, a University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Fellowship Grant, and the Nebraska Arthritis Outcomes Research Center. No information was provided on author disclosures.

SOURCE: Coburn B et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1002/art.40486.

An allopurinol dose escalation strategy for patients with gout was associated with a small increase in all-cause mortality when compared against a static dosing strategy, results of a recent observational study show.

Allopurinol dose escalation was also associated with small, but not statistically significant, increases in cardiovascular- and cancer-related mortality, investigators said in a report published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Dr. Coburn and his colleagues had hypothesized that dose escalation would instead be associated with lower cause-specific cardiovascular and cancer mortality, compared with static dosing, according to the report.

However, a minority of dose-escalated patients achieved serum urate goal. Thus, inadequate escalation may have obscured any potential mortality benefit associated with the treatment strategy, the investigators suggested.

Current guidelines recommend starting gout patients on a low dose of allopurinol (100 mg/day or less) and then titrating up the dose slowly.

“While randomized, controlled trials of urate-lowering therapies have used static dosing strategies, such strategies are suboptimal and should now be considered unethical,” they wrote.

The researchers’ 10-year, observational, active-comparator study included 6,428 U.S. veterans with gout receiving allopurinol according to a dose escalation strategy, and 6,428 matched individuals not treated with an escalation approach.

Dose escalators had significantly increased all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.17). Similar, but not statistically significant, effect sizes were seen for cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.97-1.21) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.88-1.27), the investigators reported.

However, only 10% of dose-escalation patients received allopurinol in doses exceeding 300 mg daily, and only about one-third achieved a serum urate goal of less than 6.0 mg/dL after 2 years, they found.

“Patients receiving urate-lowering therapy dose escalation were only rarely escalated to levels typically required for proper gout control,” the investigators said.

Inadequate dose escalation amounts to “clinical inertia” that limited the ability of the study to show how optimal dose escalation may affect mortality, the investigators said.

“This appears to be particularly relevant since gout patients receiving dose escalation and achieving serum urate goal appeared to have lower cardiovascular mortality in sensitivity analyses,” they noted.

There was a 7% reduction in cardiovascular mortality in a sensitivity analysis limited to dose escalators who achieved goal, though that finding did not reach statistical significance, Dr. Coburn and his coinvestigators reported (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.76-1.14).

“Taken together, these results add to the persistent uncertainty regarding the role of urate-lowering therapy in reducing mortality risk,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Health Professional Research Preceptorship, a University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Fellowship Grant, and the Nebraska Arthritis Outcomes Research Center. No information was provided on author disclosures.

SOURCE: Coburn B et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1002/art.40486.

An allopurinol dose escalation strategy for patients with gout was associated with a small increase in all-cause mortality when compared against a static dosing strategy, results of a recent observational study show.

Allopurinol dose escalation was also associated with small, but not statistically significant, increases in cardiovascular- and cancer-related mortality, investigators said in a report published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Dr. Coburn and his colleagues had hypothesized that dose escalation would instead be associated with lower cause-specific cardiovascular and cancer mortality, compared with static dosing, according to the report.

However, a minority of dose-escalated patients achieved serum urate goal. Thus, inadequate escalation may have obscured any potential mortality benefit associated with the treatment strategy, the investigators suggested.

Current guidelines recommend starting gout patients on a low dose of allopurinol (100 mg/day or less) and then titrating up the dose slowly.

“While randomized, controlled trials of urate-lowering therapies have used static dosing strategies, such strategies are suboptimal and should now be considered unethical,” they wrote.

The researchers’ 10-year, observational, active-comparator study included 6,428 U.S. veterans with gout receiving allopurinol according to a dose escalation strategy, and 6,428 matched individuals not treated with an escalation approach.

Dose escalators had significantly increased all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.17). Similar, but not statistically significant, effect sizes were seen for cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.97-1.21) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.88-1.27), the investigators reported.

However, only 10% of dose-escalation patients received allopurinol in doses exceeding 300 mg daily, and only about one-third achieved a serum urate goal of less than 6.0 mg/dL after 2 years, they found.

“Patients receiving urate-lowering therapy dose escalation were only rarely escalated to levels typically required for proper gout control,” the investigators said.

Inadequate dose escalation amounts to “clinical inertia” that limited the ability of the study to show how optimal dose escalation may affect mortality, the investigators said.

“This appears to be particularly relevant since gout patients receiving dose escalation and achieving serum urate goal appeared to have lower cardiovascular mortality in sensitivity analyses,” they noted.

There was a 7% reduction in cardiovascular mortality in a sensitivity analysis limited to dose escalators who achieved goal, though that finding did not reach statistical significance, Dr. Coburn and his coinvestigators reported (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.76-1.14).

“Taken together, these results add to the persistent uncertainty regarding the role of urate-lowering therapy in reducing mortality risk,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Health Professional Research Preceptorship, a University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Fellowship Grant, and the Nebraska Arthritis Outcomes Research Center. No information was provided on author disclosures.

SOURCE: Coburn B et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1002/art.40486.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients treated with a dose escalation strategy had a small but statistically significant increase in all-cause mortality, compared with non-escalators (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.17).

Study details: A 10-year observational, active-comparator study of U.S. veterans with gout who initiated allopurinol, including 6,428 dose escalators and 6,428 non-escalators.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a Rheumatology Research Foundation Health Professional Research Preceptorship, a University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Fellowship Grant, and the Nebraska Arthritis Outcomes Research Center. No information was provided on author disclosures.

Source: Coburn B et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Mar 7. doi: 10.1002/art.40486.

Febuxostat increases cardiovascular mortality in CARES trial

ORLANDO – Long-term treatment with febuxostat in gout patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease conferred significantly higher risks of both cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, compared with allopurinol, in the Food and Drug Administration–mandated postmarketing CARES trial, William B. White, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat or Allopurinol in Patients with Gout and Cardiovascular Disease) was a prospective, double-blind, 320-center North American clinical trial in which 6,190 patients were randomized to febuxostat (Uloric) at 40-80 mg once daily or 200-600 mg of allopurinol once daily. The postmarketing safety study was required by the FDA as a condition of marketing approval for febuxostat in light of preapproval evidence suggestive of a possible increased risk of cardiovascular events, explained Dr. White, professor of medicine and chief of the division of hypertension and clinical pharmacology at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

The warning klaxon sounded when investigators scrutinized the individual components of the primary endpoint. They found that the 4.3% cardiovascular death rate in the febuxostat group was significantly higher than the 3.2% rate in the allopurinol group, representing a statistically significant 34% increase in relative risk. The event curves began to separate roughly 30 months into the trial. Moreover, all-cause mortality was also significantly increased in the febuxostat group, by a margin of 7.8% to 6.4%, for a 22% increase in risk.

The increased cardiovascular mortality in the febuxostat group was driven by a higher adjudicated sudden cardiac death rate: 2.7%, compared with 1.8% in the allopurinol group.

In a prespecified per protocol analysis of cardiovascular events occurring while patients were actually on treatment or within 1 month after discontinuation, the key findings remained unchanged: no between-group difference in the primary composite endpoint, but a 49% increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular death in the febuxostat-treated patients.

A hefty 45% of participants stopped taking their assigned drug early. Dr. White said this isn’t unusual; high dropout rates are common in clinical trials of patients with painful conditions. Because of the high lost-to-follow-up rate, however, the investigators hired a private investigator to scour the country looking for missed deaths among enrollees. This turned up an extra 199 deaths. When those were added to the total, all-cause mortality in the febuxostat group was no longer significantly higher than for allopurinol.

The puzzle over nonfatal events

A puzzling key study finding was that except for cardiovascular death, the other components of the primary composite endpoint – that is, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and urgent revascularization due to unstable angina – were all either neutral or numerically favored febuxostat.

“That’s been the biggest challenge in the trial: The nonfatal events didn’t go in the same direction as the fatal events. And we don’t have a real mechanism to explain why,” Dr. White told a panel of discussants.

“I scanned the medical literature over the last 4 decades, and I did not see another prospective, randomized, double-blind trial in which mortality was increased when none of the nonfatal events were increased. The finding is unique. Statistically there is only a 4% chance that the mortality finding is wrong,” the cardiologist said.

The CARES leadership included rheumatologists and nephrologists as well as cardiologists. Dr. White said he and the others were at a loss to come up with an explanation for the findings.

Patients in the febuxostat arm were significantly more likely to achieve serum urate levels below 6 and 5 mg/dL. Their flare rate was 0.68 events per person-year, similar to the 0.63 per person-year rate in the allopurinol group.

Among the pieces of the study puzzle: The majority of cardiovascular deaths occurred in patients who were no longer on therapy, yet investigators could find no evidence of a legacy effect. The mortality risk was 2.3-fold greater with febuxostat than with allopurinol among patients on NSAID therapy, but there was no significant between-group difference among patients not taking NSAIDs. There was a trend for more cardiovascular deaths with febuxostat than allopurinol among patients not on low-dose aspirin. And the cardiovascular mortality was 2.2-fold greater in the febuxostat arm than with allopurinol in patients on colchicine during the study.

Notably, prior to febuxostat’s marketing approval there were extensive studies of the drug’s potential effect on left ventricular function, thrombotic potential, possible arrhythmogenic effects, and impact upon atherosclerosis. Among these investigations was a QT-interval study conducted using febuxostat doses four times higher than the maximum therapeutic dose, which was prescient given the increased sudden cardiac death rate in the subsequent CARES trial. Yet no concerning signals were seen in any of this work, he continued.

“We’re still looking at some correlates that might have an impact. For example, my rheumatologist colleagues feel very strongly that we need to look really extensively at gout flares, even though rates were not that different between the two treatment groups. Gout flares are known to increase oxidative stress and perhaps cause temporary increases in endothelial dysfunction and possibly vasomotor abnormalities,” Dr. White said.

One would think, though, that if gout flares figured in the increase in cardiovascular mortality they would also have been associated with more urgent revascularization for unstable angina, when in fact the rate was actually numerically lower in the febuxostat group, he noted.

Discussant Athena Poppas, MD, director of the Lifespan Cardiovascular Institute at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, said she couldn’t determine how much of the increased cardiovascular mortality in the febuxostat patients was due to the drug and how much resulted from the suboptimal use of guideline-directed medical therapy across both study arms. At baseline, only 60% of study participants – all by definition at high cardiovascular risk – were on aspirin, just under 75% were on lipid-lowering therapy, 58% were on a beta blocker, and 70% were on a renin-angiotensin system blocker, even though the majority of subjects had stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

Implications of findings and FDA’s next steps

Another discussant, C. Noel Bairey Merz, MD, called the CARES findings “curious.” But despite the lack of a plausible mechanistic explanation for the results, she said, the implications are clear.

“I would conclude that because your modified intention-to-treat as well as your per protocol analyses were consistent for the death endpoint, then despite the high dropout rate, that finding is relatively robust and probably should be used to inform policy,” said Dr. Merz, director of the Women’s Heart Center and the Preventive and Rehabilitative Cardiac Center in the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute and professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

At a press conference, Dr. White said the FDA will spend several months poring over the CARES results and that it would be premature to speculate on what action the agency might take on febuxostat. The drug is prescribed far less frequently than allopurinol for the nation’s estimated 8.2 million gout patients.

“I would certainly be concerned about our findings. However, rheumatologists take care of very ill patients and all the drugs they use have morbidity. So if they’re having substantial efficacy and the person has been on febuxostat for 8 years, I suspect they’re going to continue to give that drug to him,” he said.

Simultaneously with Dr. White’s presentation at ACC 2018, the CARES results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710895).

The CARES trial was funded by Takeda. Dr. White reported serving as a consultant to that company and Novartis and receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: White W et al. ACC 18.

ORLANDO – Long-term treatment with febuxostat in gout patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease conferred significantly higher risks of both cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, compared with allopurinol, in the Food and Drug Administration–mandated postmarketing CARES trial, William B. White, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat or Allopurinol in Patients with Gout and Cardiovascular Disease) was a prospective, double-blind, 320-center North American clinical trial in which 6,190 patients were randomized to febuxostat (Uloric) at 40-80 mg once daily or 200-600 mg of allopurinol once daily. The postmarketing safety study was required by the FDA as a condition of marketing approval for febuxostat in light of preapproval evidence suggestive of a possible increased risk of cardiovascular events, explained Dr. White, professor of medicine and chief of the division of hypertension and clinical pharmacology at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

The warning klaxon sounded when investigators scrutinized the individual components of the primary endpoint. They found that the 4.3% cardiovascular death rate in the febuxostat group was significantly higher than the 3.2% rate in the allopurinol group, representing a statistically significant 34% increase in relative risk. The event curves began to separate roughly 30 months into the trial. Moreover, all-cause mortality was also significantly increased in the febuxostat group, by a margin of 7.8% to 6.4%, for a 22% increase in risk.

The increased cardiovascular mortality in the febuxostat group was driven by a higher adjudicated sudden cardiac death rate: 2.7%, compared with 1.8% in the allopurinol group.

In a prespecified per protocol analysis of cardiovascular events occurring while patients were actually on treatment or within 1 month after discontinuation, the key findings remained unchanged: no between-group difference in the primary composite endpoint, but a 49% increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular death in the febuxostat-treated patients.

A hefty 45% of participants stopped taking their assigned drug early. Dr. White said this isn’t unusual; high dropout rates are common in clinical trials of patients with painful conditions. Because of the high lost-to-follow-up rate, however, the investigators hired a private investigator to scour the country looking for missed deaths among enrollees. This turned up an extra 199 deaths. When those were added to the total, all-cause mortality in the febuxostat group was no longer significantly higher than for allopurinol.

The puzzle over nonfatal events

A puzzling key study finding was that except for cardiovascular death, the other components of the primary composite endpoint – that is, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and urgent revascularization due to unstable angina – were all either neutral or numerically favored febuxostat.

“That’s been the biggest challenge in the trial: The nonfatal events didn’t go in the same direction as the fatal events. And we don’t have a real mechanism to explain why,” Dr. White told a panel of discussants.

“I scanned the medical literature over the last 4 decades, and I did not see another prospective, randomized, double-blind trial in which mortality was increased when none of the nonfatal events were increased. The finding is unique. Statistically there is only a 4% chance that the mortality finding is wrong,” the cardiologist said.

The CARES leadership included rheumatologists and nephrologists as well as cardiologists. Dr. White said he and the others were at a loss to come up with an explanation for the findings.

Patients in the febuxostat arm were significantly more likely to achieve serum urate levels below 6 and 5 mg/dL. Their flare rate was 0.68 events per person-year, similar to the 0.63 per person-year rate in the allopurinol group.

Among the pieces of the study puzzle: The majority of cardiovascular deaths occurred in patients who were no longer on therapy, yet investigators could find no evidence of a legacy effect. The mortality risk was 2.3-fold greater with febuxostat than with allopurinol among patients on NSAID therapy, but there was no significant between-group difference among patients not taking NSAIDs. There was a trend for more cardiovascular deaths with febuxostat than allopurinol among patients not on low-dose aspirin. And the cardiovascular mortality was 2.2-fold greater in the febuxostat arm than with allopurinol in patients on colchicine during the study.

Notably, prior to febuxostat’s marketing approval there were extensive studies of the drug’s potential effect on left ventricular function, thrombotic potential, possible arrhythmogenic effects, and impact upon atherosclerosis. Among these investigations was a QT-interval study conducted using febuxostat doses four times higher than the maximum therapeutic dose, which was prescient given the increased sudden cardiac death rate in the subsequent CARES trial. Yet no concerning signals were seen in any of this work, he continued.

“We’re still looking at some correlates that might have an impact. For example, my rheumatologist colleagues feel very strongly that we need to look really extensively at gout flares, even though rates were not that different between the two treatment groups. Gout flares are known to increase oxidative stress and perhaps cause temporary increases in endothelial dysfunction and possibly vasomotor abnormalities,” Dr. White said.

One would think, though, that if gout flares figured in the increase in cardiovascular mortality they would also have been associated with more urgent revascularization for unstable angina, when in fact the rate was actually numerically lower in the febuxostat group, he noted.

Discussant Athena Poppas, MD, director of the Lifespan Cardiovascular Institute at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, said she couldn’t determine how much of the increased cardiovascular mortality in the febuxostat patients was due to the drug and how much resulted from the suboptimal use of guideline-directed medical therapy across both study arms. At baseline, only 60% of study participants – all by definition at high cardiovascular risk – were on aspirin, just under 75% were on lipid-lowering therapy, 58% were on a beta blocker, and 70% were on a renin-angiotensin system blocker, even though the majority of subjects had stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

Implications of findings and FDA’s next steps

Another discussant, C. Noel Bairey Merz, MD, called the CARES findings “curious.” But despite the lack of a plausible mechanistic explanation for the results, she said, the implications are clear.

“I would conclude that because your modified intention-to-treat as well as your per protocol analyses were consistent for the death endpoint, then despite the high dropout rate, that finding is relatively robust and probably should be used to inform policy,” said Dr. Merz, director of the Women’s Heart Center and the Preventive and Rehabilitative Cardiac Center in the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute and professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

At a press conference, Dr. White said the FDA will spend several months poring over the CARES results and that it would be premature to speculate on what action the agency might take on febuxostat. The drug is prescribed far less frequently than allopurinol for the nation’s estimated 8.2 million gout patients.

“I would certainly be concerned about our findings. However, rheumatologists take care of very ill patients and all the drugs they use have morbidity. So if they’re having substantial efficacy and the person has been on febuxostat for 8 years, I suspect they’re going to continue to give that drug to him,” he said.

Simultaneously with Dr. White’s presentation at ACC 2018, the CARES results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710895).

The CARES trial was funded by Takeda. Dr. White reported serving as a consultant to that company and Novartis and receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: White W et al. ACC 18.

ORLANDO – Long-term treatment with febuxostat in gout patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease conferred significantly higher risks of both cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, compared with allopurinol, in the Food and Drug Administration–mandated postmarketing CARES trial, William B. White, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat or Allopurinol in Patients with Gout and Cardiovascular Disease) was a prospective, double-blind, 320-center North American clinical trial in which 6,190 patients were randomized to febuxostat (Uloric) at 40-80 mg once daily or 200-600 mg of allopurinol once daily. The postmarketing safety study was required by the FDA as a condition of marketing approval for febuxostat in light of preapproval evidence suggestive of a possible increased risk of cardiovascular events, explained Dr. White, professor of medicine and chief of the division of hypertension and clinical pharmacology at the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

The warning klaxon sounded when investigators scrutinized the individual components of the primary endpoint. They found that the 4.3% cardiovascular death rate in the febuxostat group was significantly higher than the 3.2% rate in the allopurinol group, representing a statistically significant 34% increase in relative risk. The event curves began to separate roughly 30 months into the trial. Moreover, all-cause mortality was also significantly increased in the febuxostat group, by a margin of 7.8% to 6.4%, for a 22% increase in risk.

The increased cardiovascular mortality in the febuxostat group was driven by a higher adjudicated sudden cardiac death rate: 2.7%, compared with 1.8% in the allopurinol group.

In a prespecified per protocol analysis of cardiovascular events occurring while patients were actually on treatment or within 1 month after discontinuation, the key findings remained unchanged: no between-group difference in the primary composite endpoint, but a 49% increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular death in the febuxostat-treated patients.

A hefty 45% of participants stopped taking their assigned drug early. Dr. White said this isn’t unusual; high dropout rates are common in clinical trials of patients with painful conditions. Because of the high lost-to-follow-up rate, however, the investigators hired a private investigator to scour the country looking for missed deaths among enrollees. This turned up an extra 199 deaths. When those were added to the total, all-cause mortality in the febuxostat group was no longer significantly higher than for allopurinol.

The puzzle over nonfatal events

A puzzling key study finding was that except for cardiovascular death, the other components of the primary composite endpoint – that is, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and urgent revascularization due to unstable angina – were all either neutral or numerically favored febuxostat.

“That’s been the biggest challenge in the trial: The nonfatal events didn’t go in the same direction as the fatal events. And we don’t have a real mechanism to explain why,” Dr. White told a panel of discussants.

“I scanned the medical literature over the last 4 decades, and I did not see another prospective, randomized, double-blind trial in which mortality was increased when none of the nonfatal events were increased. The finding is unique. Statistically there is only a 4% chance that the mortality finding is wrong,” the cardiologist said.

The CARES leadership included rheumatologists and nephrologists as well as cardiologists. Dr. White said he and the others were at a loss to come up with an explanation for the findings.

Patients in the febuxostat arm were significantly more likely to achieve serum urate levels below 6 and 5 mg/dL. Their flare rate was 0.68 events per person-year, similar to the 0.63 per person-year rate in the allopurinol group.

Among the pieces of the study puzzle: The majority of cardiovascular deaths occurred in patients who were no longer on therapy, yet investigators could find no evidence of a legacy effect. The mortality risk was 2.3-fold greater with febuxostat than with allopurinol among patients on NSAID therapy, but there was no significant between-group difference among patients not taking NSAIDs. There was a trend for more cardiovascular deaths with febuxostat than allopurinol among patients not on low-dose aspirin. And the cardiovascular mortality was 2.2-fold greater in the febuxostat arm than with allopurinol in patients on colchicine during the study.

Notably, prior to febuxostat’s marketing approval there were extensive studies of the drug’s potential effect on left ventricular function, thrombotic potential, possible arrhythmogenic effects, and impact upon atherosclerosis. Among these investigations was a QT-interval study conducted using febuxostat doses four times higher than the maximum therapeutic dose, which was prescient given the increased sudden cardiac death rate in the subsequent CARES trial. Yet no concerning signals were seen in any of this work, he continued.

“We’re still looking at some correlates that might have an impact. For example, my rheumatologist colleagues feel very strongly that we need to look really extensively at gout flares, even though rates were not that different between the two treatment groups. Gout flares are known to increase oxidative stress and perhaps cause temporary increases in endothelial dysfunction and possibly vasomotor abnormalities,” Dr. White said.

One would think, though, that if gout flares figured in the increase in cardiovascular mortality they would also have been associated with more urgent revascularization for unstable angina, when in fact the rate was actually numerically lower in the febuxostat group, he noted.

Discussant Athena Poppas, MD, director of the Lifespan Cardiovascular Institute at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, said she couldn’t determine how much of the increased cardiovascular mortality in the febuxostat patients was due to the drug and how much resulted from the suboptimal use of guideline-directed medical therapy across both study arms. At baseline, only 60% of study participants – all by definition at high cardiovascular risk – were on aspirin, just under 75% were on lipid-lowering therapy, 58% were on a beta blocker, and 70% were on a renin-angiotensin system blocker, even though the majority of subjects had stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

Implications of findings and FDA’s next steps

Another discussant, C. Noel Bairey Merz, MD, called the CARES findings “curious.” But despite the lack of a plausible mechanistic explanation for the results, she said, the implications are clear.

“I would conclude that because your modified intention-to-treat as well as your per protocol analyses were consistent for the death endpoint, then despite the high dropout rate, that finding is relatively robust and probably should be used to inform policy,” said Dr. Merz, director of the Women’s Heart Center and the Preventive and Rehabilitative Cardiac Center in the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute and professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

At a press conference, Dr. White said the FDA will spend several months poring over the CARES results and that it would be premature to speculate on what action the agency might take on febuxostat. The drug is prescribed far less frequently than allopurinol for the nation’s estimated 8.2 million gout patients.

“I would certainly be concerned about our findings. However, rheumatologists take care of very ill patients and all the drugs they use have morbidity. So if they’re having substantial efficacy and the person has been on febuxostat for 8 years, I suspect they’re going to continue to give that drug to him,” he said.

Simultaneously with Dr. White’s presentation at ACC 2018, the CARES results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710895).

The CARES trial was funded by Takeda. Dr. White reported serving as a consultant to that company and Novartis and receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: White W et al. ACC 18.

REPORTING FROM ACC 18

Key clinical point: Gout patients on febuxostat were 34% more likely to die of cardiovascular causes than were those on allopurinol.

Major finding: Death due to cardiovascular causes occurred in 4.3% of febuxostat-treated patients and 3.2% assigned to allopurinol.

Study details: This prospective, randomized, double-blind, 320-center clinical trial included nearly 6,200 gout patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease.

Disclosures: The FDA-mandated CARES trial was sponsored by Takeda. The study presenter is a consultant to the company.

Source: White W et al. ACC 18.

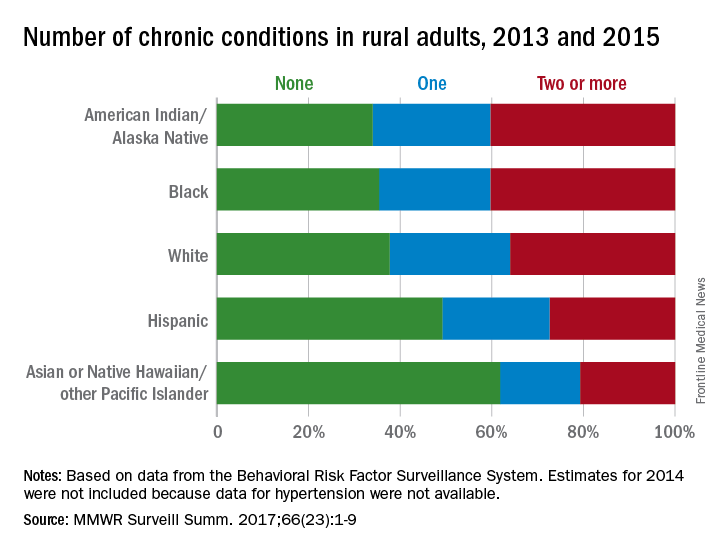

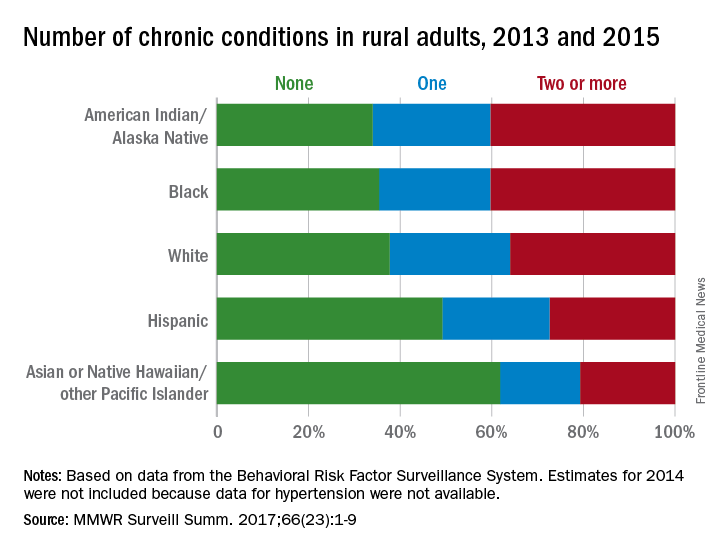

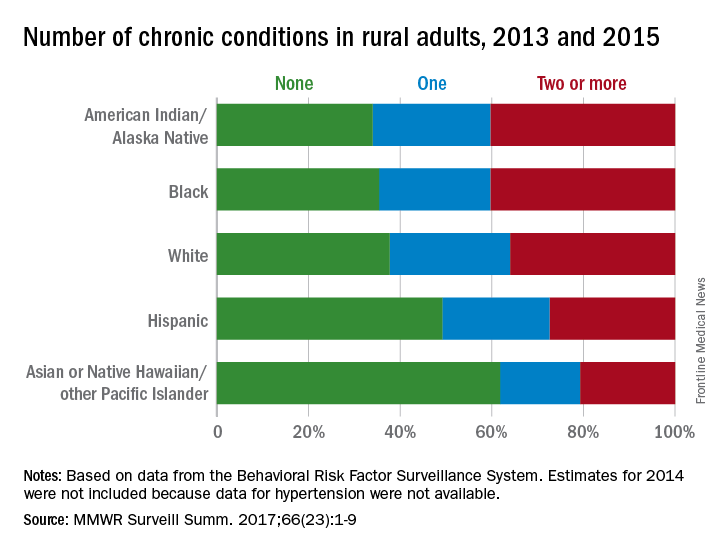

Health disparities in rural America: Chronic conditions

Among rural adults, multiple chronic health conditions are most common in non-Hispanic blacks and American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) and least common among Asians and Native Hawaiians/other Pacific Islanders (NHOPIs), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The order was reversed for adults reporting no chronic conditions: Asians and NHOPIs at 61.8%, Hispanics at 49.2%, whites at 37.8%, blacks at 35.4%, and AI/ANs at 34.0%, the researchers said.

For the chronic health conditions included separately in the report, blacks had the highest rate (45.9%) and Asians and NHOPIs had the lowest rate (15.5%) of obesity; AI/ANs were most likely (23.2%) and Asians and NHOPIs were least likely (5.8%) to report depressive disorder. Other conditions considered in the estimates were myocardial infarction; coronary heart disease; stroke; hypertension; asthma; skin cancer; other types of cancer; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; kidney disease; some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; and diabetes. Estimates for 2014 were not included because data for hypertension were not available, the investigators noted.

Of the 3,143 counties categorized by the National Center for Health Statistics’ Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, a total of 1,325 were considered rural and included 6.1% of the U.S. population, they said.

Among rural adults, multiple chronic health conditions are most common in non-Hispanic blacks and American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) and least common among Asians and Native Hawaiians/other Pacific Islanders (NHOPIs), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The order was reversed for adults reporting no chronic conditions: Asians and NHOPIs at 61.8%, Hispanics at 49.2%, whites at 37.8%, blacks at 35.4%, and AI/ANs at 34.0%, the researchers said.

For the chronic health conditions included separately in the report, blacks had the highest rate (45.9%) and Asians and NHOPIs had the lowest rate (15.5%) of obesity; AI/ANs were most likely (23.2%) and Asians and NHOPIs were least likely (5.8%) to report depressive disorder. Other conditions considered in the estimates were myocardial infarction; coronary heart disease; stroke; hypertension; asthma; skin cancer; other types of cancer; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; kidney disease; some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; and diabetes. Estimates for 2014 were not included because data for hypertension were not available, the investigators noted.

Of the 3,143 counties categorized by the National Center for Health Statistics’ Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, a total of 1,325 were considered rural and included 6.1% of the U.S. population, they said.

Among rural adults, multiple chronic health conditions are most common in non-Hispanic blacks and American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) and least common among Asians and Native Hawaiians/other Pacific Islanders (NHOPIs), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The order was reversed for adults reporting no chronic conditions: Asians and NHOPIs at 61.8%, Hispanics at 49.2%, whites at 37.8%, blacks at 35.4%, and AI/ANs at 34.0%, the researchers said.

For the chronic health conditions included separately in the report, blacks had the highest rate (45.9%) and Asians and NHOPIs had the lowest rate (15.5%) of obesity; AI/ANs were most likely (23.2%) and Asians and NHOPIs were least likely (5.8%) to report depressive disorder. Other conditions considered in the estimates were myocardial infarction; coronary heart disease; stroke; hypertension; asthma; skin cancer; other types of cancer; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; kidney disease; some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia; and diabetes. Estimates for 2014 were not included because data for hypertension were not available, the investigators noted.

Of the 3,143 counties categorized by the National Center for Health Statistics’ Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, a total of 1,325 were considered rural and included 6.1% of the U.S. population, they said.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

Rheumatology 911: Inside the rheumatologic emergency

SAN DIEGO – At first glance, rheumatology may seem like the perfect specialty for physicians who don’t want to be bothered by medical emergencies. But the reality can be more complicated.

As Bharat Kumar, MD, explained to an audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, rheumatologists will at times encounter patients in urgent need of their care due to dire medical conditions. In these situations, he said, there may be no time for careful and cautious diagnostics.

“You have to have an awareness of how you think about things,” advised Dr. Kumar, a rheumatologist/immunologist and clinical assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “During emergencies, you have to rely more on intuition to quickly get at answers.”

Q: When do rheumatologists have to deal with medical emergencies?

A: Rheumatology is considered mostly an outpatient specialty. Most of the time, rheumatologists don’t receive off-hour emergency calls.

But there are conditions in which rheumatologists have to be at the front lines in diagnosing and managing medical emergencies. These range from issues like septic arthritis to scleroderma renal crisis and vasculitis affecting vital organs such as the heart, lungs, and kidneys. These are more common at academic settings, but even rheumatologists in private practice should be aware of these conditions.

Q: How often do rheumatologists come across true emergencies in normal practice?

A: It depends on where the rheumatologist is practicing. In our academic setting, we have to see patients in the hospital several times per week.

Rarer are the emergencies that show up to clinic and require evaluation in the emergency department or hospitalization. Over the past year, that has happened perhaps three times to me.

This is likely much less in the private setting, where patients tend to be less sick and less complicated. But that is no guarantee that an emergency won’t crop up.

Q: What is the scariest emergency situation that you’ve come across?

A: It occurred when I entered a room to see a patient of mine with adult-onset Still’s disease.

She was huddled, shivering, barely answering questions. Her eyes were glazed. Her blood pressure was below 90/60 mm Hg, and her pulse was 130 beats per minute. I was petrified that she was in the midst of a cytokine storm secondary to either hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) or sepsis. Given the high mortality of both, we immediately called our colleagues in the emergency department and sent her for hospitalization. It turned out that she did have HLH, and we had to pursue intensive immunosuppression to abate that cytokine storm.

It was particularly scary because there is no good way to differentiate between the two conditions, apart from going with clinical intuition.

Treating a patient who is potentially septic with immunosuppression is extremely dangerous, and ultimately, we would not have known if our intuition was correct until the infection presented itself.

Fortunately, we were correct. She recovered after 1 week of hospitalization, and we have been following her since then. But it still gives me goosebumps to think, “What if we were wrong?”

Q: Do emergencies in rheumatology tend to appear suddenly or are they more likely to occur because of a long-standing and perhaps untreated condition?

A: While it is true that uncontrolled disease activity can predispose patients to emergencies, other emergencies can occur sporadically and out of the blue.

Many times, an emergency is the first manifestation of disease. The literature is littered with cases of renal crisis being the first manifestation of systemic sclerosis. And internists are often baffled by sudden kidney failure due to previously undiagnosed lupus.

In addition, all rheumatologists have great reverence for septic arthritis and know that it can mimic gout very closely. If a swollen joint is mistaken for gout instead of septic arthritis, this can lead to worsening infection and ultimately, loss of joint function.

Q: What are some potentially dire conditions that may test the diagnostic powers of rheumatologists?

A: Rheumatologists are becoming more aware of HLH. Because it may look clinically indistinguishable from severe infection but needs to be treated with immunosuppression instead of antimicrobial therapy, rheumatologists have to keep it in mind and revisit the diagnosis often in case patients are not improving on the prescribed therapy.

Pulmonary vasculitis is another concerning condition because an otherwise negligible cough can turn into massive pulmonary hemorrhage very quickly.

Q: Do you have tips about dealing with ER doctors, primary doctors and others who may be involved with an emergency?

A: Rheumatologists think differently from other specialists. We are cognitive specialists and think more in the long term. Emergency medicine doctors are more concerned about the short term and how to deal with more immediate issues.

Signposting concerns is essential to optimizing communication. Education of other physicians is also important because more frequently than not, patients with rheumatologic diseases present very differently.

Lastly, there’s a very fine line between advocating for patients and overstepping your bounds as a consultant rheumatologist. Maintaining close collaboration and establishing clear and open lines of communication can prevent this.

Dr. Kumar has no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – At first glance, rheumatology may seem like the perfect specialty for physicians who don’t want to be bothered by medical emergencies. But the reality can be more complicated.

As Bharat Kumar, MD, explained to an audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, rheumatologists will at times encounter patients in urgent need of their care due to dire medical conditions. In these situations, he said, there may be no time for careful and cautious diagnostics.

“You have to have an awareness of how you think about things,” advised Dr. Kumar, a rheumatologist/immunologist and clinical assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “During emergencies, you have to rely more on intuition to quickly get at answers.”

Q: When do rheumatologists have to deal with medical emergencies?

A: Rheumatology is considered mostly an outpatient specialty. Most of the time, rheumatologists don’t receive off-hour emergency calls.

But there are conditions in which rheumatologists have to be at the front lines in diagnosing and managing medical emergencies. These range from issues like septic arthritis to scleroderma renal crisis and vasculitis affecting vital organs such as the heart, lungs, and kidneys. These are more common at academic settings, but even rheumatologists in private practice should be aware of these conditions.

Q: How often do rheumatologists come across true emergencies in normal practice?

A: It depends on where the rheumatologist is practicing. In our academic setting, we have to see patients in the hospital several times per week.

Rarer are the emergencies that show up to clinic and require evaluation in the emergency department or hospitalization. Over the past year, that has happened perhaps three times to me.

This is likely much less in the private setting, where patients tend to be less sick and less complicated. But that is no guarantee that an emergency won’t crop up.

Q: What is the scariest emergency situation that you’ve come across?

A: It occurred when I entered a room to see a patient of mine with adult-onset Still’s disease.

She was huddled, shivering, barely answering questions. Her eyes were glazed. Her blood pressure was below 90/60 mm Hg, and her pulse was 130 beats per minute. I was petrified that she was in the midst of a cytokine storm secondary to either hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) or sepsis. Given the high mortality of both, we immediately called our colleagues in the emergency department and sent her for hospitalization. It turned out that she did have HLH, and we had to pursue intensive immunosuppression to abate that cytokine storm.

It was particularly scary because there is no good way to differentiate between the two conditions, apart from going with clinical intuition.

Treating a patient who is potentially septic with immunosuppression is extremely dangerous, and ultimately, we would not have known if our intuition was correct until the infection presented itself.

Fortunately, we were correct. She recovered after 1 week of hospitalization, and we have been following her since then. But it still gives me goosebumps to think, “What if we were wrong?”

Q: Do emergencies in rheumatology tend to appear suddenly or are they more likely to occur because of a long-standing and perhaps untreated condition?

A: While it is true that uncontrolled disease activity can predispose patients to emergencies, other emergencies can occur sporadically and out of the blue.

Many times, an emergency is the first manifestation of disease. The literature is littered with cases of renal crisis being the first manifestation of systemic sclerosis. And internists are often baffled by sudden kidney failure due to previously undiagnosed lupus.

In addition, all rheumatologists have great reverence for septic arthritis and know that it can mimic gout very closely. If a swollen joint is mistaken for gout instead of septic arthritis, this can lead to worsening infection and ultimately, loss of joint function.

Q: What are some potentially dire conditions that may test the diagnostic powers of rheumatologists?

A: Rheumatologists are becoming more aware of HLH. Because it may look clinically indistinguishable from severe infection but needs to be treated with immunosuppression instead of antimicrobial therapy, rheumatologists have to keep it in mind and revisit the diagnosis often in case patients are not improving on the prescribed therapy.

Pulmonary vasculitis is another concerning condition because an otherwise negligible cough can turn into massive pulmonary hemorrhage very quickly.

Q: Do you have tips about dealing with ER doctors, primary doctors and others who may be involved with an emergency?

A: Rheumatologists think differently from other specialists. We are cognitive specialists and think more in the long term. Emergency medicine doctors are more concerned about the short term and how to deal with more immediate issues.

Signposting concerns is essential to optimizing communication. Education of other physicians is also important because more frequently than not, patients with rheumatologic diseases present very differently.

Lastly, there’s a very fine line between advocating for patients and overstepping your bounds as a consultant rheumatologist. Maintaining close collaboration and establishing clear and open lines of communication can prevent this.

Dr. Kumar has no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – At first glance, rheumatology may seem like the perfect specialty for physicians who don’t want to be bothered by medical emergencies. But the reality can be more complicated.

As Bharat Kumar, MD, explained to an audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, rheumatologists will at times encounter patients in urgent need of their care due to dire medical conditions. In these situations, he said, there may be no time for careful and cautious diagnostics.

“You have to have an awareness of how you think about things,” advised Dr. Kumar, a rheumatologist/immunologist and clinical assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “During emergencies, you have to rely more on intuition to quickly get at answers.”

Q: When do rheumatologists have to deal with medical emergencies?

A: Rheumatology is considered mostly an outpatient specialty. Most of the time, rheumatologists don’t receive off-hour emergency calls.

But there are conditions in which rheumatologists have to be at the front lines in diagnosing and managing medical emergencies. These range from issues like septic arthritis to scleroderma renal crisis and vasculitis affecting vital organs such as the heart, lungs, and kidneys. These are more common at academic settings, but even rheumatologists in private practice should be aware of these conditions.

Q: How often do rheumatologists come across true emergencies in normal practice?

A: It depends on where the rheumatologist is practicing. In our academic setting, we have to see patients in the hospital several times per week.

Rarer are the emergencies that show up to clinic and require evaluation in the emergency department or hospitalization. Over the past year, that has happened perhaps three times to me.

This is likely much less in the private setting, where patients tend to be less sick and less complicated. But that is no guarantee that an emergency won’t crop up.

Q: What is the scariest emergency situation that you’ve come across?

A: It occurred when I entered a room to see a patient of mine with adult-onset Still’s disease.

She was huddled, shivering, barely answering questions. Her eyes were glazed. Her blood pressure was below 90/60 mm Hg, and her pulse was 130 beats per minute. I was petrified that she was in the midst of a cytokine storm secondary to either hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) or sepsis. Given the high mortality of both, we immediately called our colleagues in the emergency department and sent her for hospitalization. It turned out that she did have HLH, and we had to pursue intensive immunosuppression to abate that cytokine storm.

It was particularly scary because there is no good way to differentiate between the two conditions, apart from going with clinical intuition.

Treating a patient who is potentially septic with immunosuppression is extremely dangerous, and ultimately, we would not have known if our intuition was correct until the infection presented itself.

Fortunately, we were correct. She recovered after 1 week of hospitalization, and we have been following her since then. But it still gives me goosebumps to think, “What if we were wrong?”

Q: Do emergencies in rheumatology tend to appear suddenly or are they more likely to occur because of a long-standing and perhaps untreated condition?

A: While it is true that uncontrolled disease activity can predispose patients to emergencies, other emergencies can occur sporadically and out of the blue.

Many times, an emergency is the first manifestation of disease. The literature is littered with cases of renal crisis being the first manifestation of systemic sclerosis. And internists are often baffled by sudden kidney failure due to previously undiagnosed lupus.

In addition, all rheumatologists have great reverence for septic arthritis and know that it can mimic gout very closely. If a swollen joint is mistaken for gout instead of septic arthritis, this can lead to worsening infection and ultimately, loss of joint function.

Q: What are some potentially dire conditions that may test the diagnostic powers of rheumatologists?

A: Rheumatologists are becoming more aware of HLH. Because it may look clinically indistinguishable from severe infection but needs to be treated with immunosuppression instead of antimicrobial therapy, rheumatologists have to keep it in mind and revisit the diagnosis often in case patients are not improving on the prescribed therapy.

Pulmonary vasculitis is another concerning condition because an otherwise negligible cough can turn into massive pulmonary hemorrhage very quickly.

Q: Do you have tips about dealing with ER doctors, primary doctors and others who may be involved with an emergency?

A: Rheumatologists think differently from other specialists. We are cognitive specialists and think more in the long term. Emergency medicine doctors are more concerned about the short term and how to deal with more immediate issues.

Signposting concerns is essential to optimizing communication. Education of other physicians is also important because more frequently than not, patients with rheumatologic diseases present very differently.

Lastly, there’s a very fine line between advocating for patients and overstepping your bounds as a consultant rheumatologist. Maintaining close collaboration and establishing clear and open lines of communication can prevent this.

Dr. Kumar has no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACR 2017

Higher water intake linked to less hyperuricemia in gout

SAN DIEGO – While more hydration seems to improve gout, there’s little research into the connection between the two. Now, a new study suggests a strong link between low water consumption and hyperuricemia, a possible sign that boosting water intake will help some gout patients.

While it’s too early to confirm a clinically relevant connection, “there is a statistically significant inverse association between water consumption and high uric acid levels,” said Patricia Kachur, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at the University of Central Florida, Ocala (Fla.) Regional Medical Center. Dr. Kachur, who spoke about the findings in an interview, is lead author of a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

An abstract presented at the 2009 ACR annual meeting reported fewer gout attacks (adjusted odds ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.90) in 535 gout patients who reported drinking more than eight glasses of water over a 24-hour period, compared with those who drank one or fewer.

For the new study, Dr. Kachur and her colleagues examined findings from 539 participants with gout (but not chronic kidney disease) out of 17,321 individuals who took part in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2009 to 2014.

Of the 539 participants, 39% were defined as having hyperuricemia (6.0 mg/dL or greater), with the rest having a low or normal level. Those with hyperuricemia were significantly more likely to be male and have obesity and hypertension.

The investigators defined high water intake as three or more liters of water per day for men and 2.2 or more liters for women. Of the 539 participants, 116 (22%) had high water intake.

The researchers found a lower risk of developing hyperuricemia in those with higher water intake, compared with those with lower intake (adjusted OR, 0.421; 95% CI, 0.262-0.679; P = .0007).

“These findings do not say anything about water and gout – not yet anyway,” Dr. Kachur said. “Rather there is a possibility that outpatient water intake has an association with lower uric acid levels in people afflicted by gout even after considering multiple other factors such as gender, race, BMI, age, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.”

Indeed, she and her colleagues decided against publishing the results of their 2009 study “because there is a major challenge in interpreting these data.”

“Given that people only consume a finite amount of liquids each day, is it that consuming more water is beneficial or that drinking less of ‘bad’ fluids (for example, sodas, sugar-sweetened juices) is beneficial? We were not able to disentangle this issue,” she explained.

Still, she said, there are explanations about why water intake could be beneficial for gout. “Intravascular volume depletion increases the concentration of serum urate, and increased serum urate beyond the saturation threshold can result in crystallization,” she said. “With heat-related dehydration, there may also be metabolic acidosis and/or electrolyte abnormalities that can lead to decreased urate secretion in renal tubules, and an acidic pH can decrease solubility of serum urate.”

Dr. Neogi does encourage appropriate gout patients to make sure they drink enough water, especially if it is hot. She cowrote a 2014 study that linked gout flares to high temperatures and extremes of humidity, which can lead to dehydration (Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Aug 15;180[4]:372-7).