User login

Ultraprocessed foods tied to faster rate of cognitive decline

Results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil), which included more than 10,000 people aged 35 and older, showed that higher intake of UPF was significantly associated with a faster rate of decline in executive and global cognitive function.

“These findings show that lifestyle choices, particularly high intake of ultraprocessed foods, can influence our cognitive health many years later,” coinvestigator Natalia Goncalves, PhD, University of São Paulo, Brazil, said in an interview.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

The study’s findings were presented in August at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2022 and were reported by this news organization at that time.

High sugar, salt, fat

The new results align with another recent study linking a diet high in UPFs to an increased risk for dementia.

UPFs are highly manipulated, are packed with added ingredients, including sugar, fat, and salt, and are low in protein and fiber. Examples of UPFs are soft drinks, chips, chocolate, candy, ice cream, sweetened breakfast cereals, packaged soups, chicken nuggets, hot dogs, and fries.

The ELSA-Brasil study comprised 10,775 adults (mean age, 50.6 years at baseline; 55% women; 53% White) who were evaluated in three waves approximately 4 years apart from 2008 to 2017.

Information on diet was obtained via food frequency questionnaires and included details regarding consumption of unprocessed foods, minimally processed foods, and UPFs.

Participants were grouped according to UPF consumption quartiles (lowest to highest). Cognitive performance was evaluated by use of a standardized battery of tests.

During median follow-up of 8 years, people who consumed more than 20% of daily calories from UPFs (quartiles 2-4) experienced a 28% faster rate of decline in global cognition (beta = –0.004; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.006 to –0.001; P = .003) and a 25% faster rate of decline in executive function (beta = –0.003, 95% CI, –0.005 to 0.000; P = .01) compared to peers in quartile 1 who consumed less than 20% of daily calories from UPFs.

The researchers did not investigate individual groups of UPFs.

However, Dr. Goncalves noted that some studies have linked the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages with lower cognitive performance, lower brain volume, and poorer memory performance. Another group of ultraprocessed foods, processed meats, has been associated with increased all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Other limitations include the fact that self-reported diet habits were assessed only at baseline using a food frequency questionnaire that was not designed to assess the degree of processing.

While analyses were adjusted for several sociodemographic and clinical confounders, the researchers said they could not exclude the possibility of residual confounding.

Also, since neuroimaging is not available in the ELSA-Brasil study, they were not able to investigate potential mechanisms that could explain the association between higher UPF consumption and cognitive decline.

Despite these limitations, the researchers said their findings suggest that “limiting UPF consumption, particularly in middle-aged adults, may be an efficient form to prevent cognitive decline.”

Weighing the evidence

Several experts weighed in on the results in a statement from the UK nonprofit organization, Science Media Centre.

Kevin McConway, PhD, with Open University, Milton Keynes, England, said it’s important to note that the study suggests “an association, a correlation, and that doesn’t necessarily mean that the cognitive decline was caused by eating more ultra-processed foods.”

He also noted that some types of cognitive decline that are associated with aging occurred in participants in all four quartiles, which were defined by the percentage of their daily energy that came from consuming UPFs.

“That’s hardly surprising – it’s a sad fact of life that pretty well all of us gradually lose some of our cognitive functions as we go through middle and older age,” Dr. McConway said.

“The study doesn’t establish that differences in speed of cognitive decline are caused by ultra-processed food consumption anyway. That’s because it’s an observational study. If the consumption of ultra-processed food causes the differences in rate of cognitive decline, then eating less of it might slow cognitive decline, but if the cause is something else, then that won’t happen,” Dr. McConway added.

Gunter Kuhnle, PhD, professor of nutrition and food science, University of Reading, England, noted that UPFs have become a “fashionable term to explain associations between diet and ill health, and many studies have attempted to show associations.

“Most studies have been observational and had a key limitation: It is very difficult to determine ultra-processed food intake using methods that are not designed to do so, and so authors need to make a lot of assumptions. Bread and meat products are often classed as ‘ultra-processed,’ even though this is often wrong,” Dr. Kuhnle noted.

“The same applies to this study – the method used to measure ultra-processed food intake was not designed for that task and relied on assumptions. This makes it virtually impossible to draw any conclusions,” Dr. Kuhnle said.

Duane Mellor, PhD, RD, RNutr, registered dietitian and senior teaching fellow, Aston University, Birmingham, England, said the study does not change how we should try to eat to maintain good brain function and cognition.

“We should try to eat less foods which are high in added sugar, salt, and fat, which would include many of the foods classified as being ultra-processed, while eating more in terms of both quantity and variety of vegetables, fruit, nuts, seeds, and pulses, which are known to be beneficial for both our cognitive and overall health,” Dr. Mellor said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development. The authors as well as Dr. McConway, Dr. Mellor, and Dr. Kuhnle have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil), which included more than 10,000 people aged 35 and older, showed that higher intake of UPF was significantly associated with a faster rate of decline in executive and global cognitive function.

“These findings show that lifestyle choices, particularly high intake of ultraprocessed foods, can influence our cognitive health many years later,” coinvestigator Natalia Goncalves, PhD, University of São Paulo, Brazil, said in an interview.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

The study’s findings were presented in August at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2022 and were reported by this news organization at that time.

High sugar, salt, fat

The new results align with another recent study linking a diet high in UPFs to an increased risk for dementia.

UPFs are highly manipulated, are packed with added ingredients, including sugar, fat, and salt, and are low in protein and fiber. Examples of UPFs are soft drinks, chips, chocolate, candy, ice cream, sweetened breakfast cereals, packaged soups, chicken nuggets, hot dogs, and fries.

The ELSA-Brasil study comprised 10,775 adults (mean age, 50.6 years at baseline; 55% women; 53% White) who were evaluated in three waves approximately 4 years apart from 2008 to 2017.

Information on diet was obtained via food frequency questionnaires and included details regarding consumption of unprocessed foods, minimally processed foods, and UPFs.

Participants were grouped according to UPF consumption quartiles (lowest to highest). Cognitive performance was evaluated by use of a standardized battery of tests.

During median follow-up of 8 years, people who consumed more than 20% of daily calories from UPFs (quartiles 2-4) experienced a 28% faster rate of decline in global cognition (beta = –0.004; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.006 to –0.001; P = .003) and a 25% faster rate of decline in executive function (beta = –0.003, 95% CI, –0.005 to 0.000; P = .01) compared to peers in quartile 1 who consumed less than 20% of daily calories from UPFs.

The researchers did not investigate individual groups of UPFs.

However, Dr. Goncalves noted that some studies have linked the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages with lower cognitive performance, lower brain volume, and poorer memory performance. Another group of ultraprocessed foods, processed meats, has been associated with increased all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Other limitations include the fact that self-reported diet habits were assessed only at baseline using a food frequency questionnaire that was not designed to assess the degree of processing.

While analyses were adjusted for several sociodemographic and clinical confounders, the researchers said they could not exclude the possibility of residual confounding.

Also, since neuroimaging is not available in the ELSA-Brasil study, they were not able to investigate potential mechanisms that could explain the association between higher UPF consumption and cognitive decline.

Despite these limitations, the researchers said their findings suggest that “limiting UPF consumption, particularly in middle-aged adults, may be an efficient form to prevent cognitive decline.”

Weighing the evidence

Several experts weighed in on the results in a statement from the UK nonprofit organization, Science Media Centre.

Kevin McConway, PhD, with Open University, Milton Keynes, England, said it’s important to note that the study suggests “an association, a correlation, and that doesn’t necessarily mean that the cognitive decline was caused by eating more ultra-processed foods.”

He also noted that some types of cognitive decline that are associated with aging occurred in participants in all four quartiles, which were defined by the percentage of their daily energy that came from consuming UPFs.

“That’s hardly surprising – it’s a sad fact of life that pretty well all of us gradually lose some of our cognitive functions as we go through middle and older age,” Dr. McConway said.

“The study doesn’t establish that differences in speed of cognitive decline are caused by ultra-processed food consumption anyway. That’s because it’s an observational study. If the consumption of ultra-processed food causes the differences in rate of cognitive decline, then eating less of it might slow cognitive decline, but if the cause is something else, then that won’t happen,” Dr. McConway added.

Gunter Kuhnle, PhD, professor of nutrition and food science, University of Reading, England, noted that UPFs have become a “fashionable term to explain associations between diet and ill health, and many studies have attempted to show associations.

“Most studies have been observational and had a key limitation: It is very difficult to determine ultra-processed food intake using methods that are not designed to do so, and so authors need to make a lot of assumptions. Bread and meat products are often classed as ‘ultra-processed,’ even though this is often wrong,” Dr. Kuhnle noted.

“The same applies to this study – the method used to measure ultra-processed food intake was not designed for that task and relied on assumptions. This makes it virtually impossible to draw any conclusions,” Dr. Kuhnle said.

Duane Mellor, PhD, RD, RNutr, registered dietitian and senior teaching fellow, Aston University, Birmingham, England, said the study does not change how we should try to eat to maintain good brain function and cognition.

“We should try to eat less foods which are high in added sugar, salt, and fat, which would include many of the foods classified as being ultra-processed, while eating more in terms of both quantity and variety of vegetables, fruit, nuts, seeds, and pulses, which are known to be beneficial for both our cognitive and overall health,” Dr. Mellor said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development. The authors as well as Dr. McConway, Dr. Mellor, and Dr. Kuhnle have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil), which included more than 10,000 people aged 35 and older, showed that higher intake of UPF was significantly associated with a faster rate of decline in executive and global cognitive function.

“These findings show that lifestyle choices, particularly high intake of ultraprocessed foods, can influence our cognitive health many years later,” coinvestigator Natalia Goncalves, PhD, University of São Paulo, Brazil, said in an interview.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

The study’s findings were presented in August at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2022 and were reported by this news organization at that time.

High sugar, salt, fat

The new results align with another recent study linking a diet high in UPFs to an increased risk for dementia.

UPFs are highly manipulated, are packed with added ingredients, including sugar, fat, and salt, and are low in protein and fiber. Examples of UPFs are soft drinks, chips, chocolate, candy, ice cream, sweetened breakfast cereals, packaged soups, chicken nuggets, hot dogs, and fries.

The ELSA-Brasil study comprised 10,775 adults (mean age, 50.6 years at baseline; 55% women; 53% White) who were evaluated in three waves approximately 4 years apart from 2008 to 2017.

Information on diet was obtained via food frequency questionnaires and included details regarding consumption of unprocessed foods, minimally processed foods, and UPFs.

Participants were grouped according to UPF consumption quartiles (lowest to highest). Cognitive performance was evaluated by use of a standardized battery of tests.

During median follow-up of 8 years, people who consumed more than 20% of daily calories from UPFs (quartiles 2-4) experienced a 28% faster rate of decline in global cognition (beta = –0.004; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.006 to –0.001; P = .003) and a 25% faster rate of decline in executive function (beta = –0.003, 95% CI, –0.005 to 0.000; P = .01) compared to peers in quartile 1 who consumed less than 20% of daily calories from UPFs.

The researchers did not investigate individual groups of UPFs.

However, Dr. Goncalves noted that some studies have linked the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages with lower cognitive performance, lower brain volume, and poorer memory performance. Another group of ultraprocessed foods, processed meats, has been associated with increased all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Other limitations include the fact that self-reported diet habits were assessed only at baseline using a food frequency questionnaire that was not designed to assess the degree of processing.

While analyses were adjusted for several sociodemographic and clinical confounders, the researchers said they could not exclude the possibility of residual confounding.

Also, since neuroimaging is not available in the ELSA-Brasil study, they were not able to investigate potential mechanisms that could explain the association between higher UPF consumption and cognitive decline.

Despite these limitations, the researchers said their findings suggest that “limiting UPF consumption, particularly in middle-aged adults, may be an efficient form to prevent cognitive decline.”

Weighing the evidence

Several experts weighed in on the results in a statement from the UK nonprofit organization, Science Media Centre.

Kevin McConway, PhD, with Open University, Milton Keynes, England, said it’s important to note that the study suggests “an association, a correlation, and that doesn’t necessarily mean that the cognitive decline was caused by eating more ultra-processed foods.”

He also noted that some types of cognitive decline that are associated with aging occurred in participants in all four quartiles, which were defined by the percentage of their daily energy that came from consuming UPFs.

“That’s hardly surprising – it’s a sad fact of life that pretty well all of us gradually lose some of our cognitive functions as we go through middle and older age,” Dr. McConway said.

“The study doesn’t establish that differences in speed of cognitive decline are caused by ultra-processed food consumption anyway. That’s because it’s an observational study. If the consumption of ultra-processed food causes the differences in rate of cognitive decline, then eating less of it might slow cognitive decline, but if the cause is something else, then that won’t happen,” Dr. McConway added.

Gunter Kuhnle, PhD, professor of nutrition and food science, University of Reading, England, noted that UPFs have become a “fashionable term to explain associations between diet and ill health, and many studies have attempted to show associations.

“Most studies have been observational and had a key limitation: It is very difficult to determine ultra-processed food intake using methods that are not designed to do so, and so authors need to make a lot of assumptions. Bread and meat products are often classed as ‘ultra-processed,’ even though this is often wrong,” Dr. Kuhnle noted.

“The same applies to this study – the method used to measure ultra-processed food intake was not designed for that task and relied on assumptions. This makes it virtually impossible to draw any conclusions,” Dr. Kuhnle said.

Duane Mellor, PhD, RD, RNutr, registered dietitian and senior teaching fellow, Aston University, Birmingham, England, said the study does not change how we should try to eat to maintain good brain function and cognition.

“We should try to eat less foods which are high in added sugar, salt, and fat, which would include many of the foods classified as being ultra-processed, while eating more in terms of both quantity and variety of vegetables, fruit, nuts, seeds, and pulses, which are known to be beneficial for both our cognitive and overall health,” Dr. Mellor said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development. The authors as well as Dr. McConway, Dr. Mellor, and Dr. Kuhnle have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Confirmed: Amyloid, tau levels rise years before Alzheimer’s onset

“Our results confirm accelerated biomarker changes during preclinical AD and highlight the important role of amyloid levels in tau accelerations,” the investigators note.

“These data may suggest that there is a short therapeutic window for slowing AD pathogenesis prior to the emergence of clinical symptoms – and that this window may occur after amyloid accumulation begins but before amyloid has substantial impacts on tau accumulation,” study investigator Corinne Pettigrew, PhD, department of neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

Novel long-term CSF data

The study builds on previous research by examining changes in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers over longer periods than had been done previously, particularly among largely middle-aged and cognitively normal at baseline individuals.

The researchers examined changes in amyloid beta (Aβ) 42/Aβ40, phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau181), and total tau (t-tau) in CSF over an average of 10.7 years (and up to 23 years) among 278 individuals who were largely middle-aged persons who were cognitively normal at baseline.

“To our knowledge, no prior study among initially cognitively normal, primarily middle-aged individuals has described CSF AD biomarker changes over this duration of follow-up,” the researchers write.

During follow-up, 94 individuals who initially had normal cognition developed mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Lower baseline levels of amyloid were associated with greater increases in tau (more strongly in men than women), while accelerations in tau were more closely linked to onset of MCI, the researchers report.

Among individuals who developed MCI, biomarker levels were more abnormal and tau increased to a greater extent prior to the onset of MCI symptoms, they found.

Clear impact of APOE4

The findings also suggest that among APOE4 carriers, amyloid onset occurs at an earlier age and rates of amyloid positivity are higher, but there are no differences in rates of change in amyloid over time.

“APOE4 genetic status was not related to changes in CSF beta-amyloid after accounting for the fact that APOE4 carriers have higher rates of amyloid positivity,” said Dr. Pettigrew.

“These findings suggest that APOE4 genetic status shifts the age of onset of amyloid accumulation (with APOE4 carriers having an earlier age of onset compared to non-carriers), but that APOE4 is not related to rates of change in CSF beta-amyloid over time,” she added.

“Thus, cognitively normal APOE4 carriers may be in more advanced preclinical AD stages at younger ages than individuals who are not APOE4 carriers, which is likely relevant for optimizing clinical trial recruitment strategies,” she said.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Pettigrew has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The original article contains a complete list of author disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Our results confirm accelerated biomarker changes during preclinical AD and highlight the important role of amyloid levels in tau accelerations,” the investigators note.

“These data may suggest that there is a short therapeutic window for slowing AD pathogenesis prior to the emergence of clinical symptoms – and that this window may occur after amyloid accumulation begins but before amyloid has substantial impacts on tau accumulation,” study investigator Corinne Pettigrew, PhD, department of neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

Novel long-term CSF data

The study builds on previous research by examining changes in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers over longer periods than had been done previously, particularly among largely middle-aged and cognitively normal at baseline individuals.

The researchers examined changes in amyloid beta (Aβ) 42/Aβ40, phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau181), and total tau (t-tau) in CSF over an average of 10.7 years (and up to 23 years) among 278 individuals who were largely middle-aged persons who were cognitively normal at baseline.

“To our knowledge, no prior study among initially cognitively normal, primarily middle-aged individuals has described CSF AD biomarker changes over this duration of follow-up,” the researchers write.

During follow-up, 94 individuals who initially had normal cognition developed mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Lower baseline levels of amyloid were associated with greater increases in tau (more strongly in men than women), while accelerations in tau were more closely linked to onset of MCI, the researchers report.

Among individuals who developed MCI, biomarker levels were more abnormal and tau increased to a greater extent prior to the onset of MCI symptoms, they found.

Clear impact of APOE4

The findings also suggest that among APOE4 carriers, amyloid onset occurs at an earlier age and rates of amyloid positivity are higher, but there are no differences in rates of change in amyloid over time.

“APOE4 genetic status was not related to changes in CSF beta-amyloid after accounting for the fact that APOE4 carriers have higher rates of amyloid positivity,” said Dr. Pettigrew.

“These findings suggest that APOE4 genetic status shifts the age of onset of amyloid accumulation (with APOE4 carriers having an earlier age of onset compared to non-carriers), but that APOE4 is not related to rates of change in CSF beta-amyloid over time,” she added.

“Thus, cognitively normal APOE4 carriers may be in more advanced preclinical AD stages at younger ages than individuals who are not APOE4 carriers, which is likely relevant for optimizing clinical trial recruitment strategies,” she said.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Pettigrew has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The original article contains a complete list of author disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Our results confirm accelerated biomarker changes during preclinical AD and highlight the important role of amyloid levels in tau accelerations,” the investigators note.

“These data may suggest that there is a short therapeutic window for slowing AD pathogenesis prior to the emergence of clinical symptoms – and that this window may occur after amyloid accumulation begins but before amyloid has substantial impacts on tau accumulation,” study investigator Corinne Pettigrew, PhD, department of neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

Novel long-term CSF data

The study builds on previous research by examining changes in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers over longer periods than had been done previously, particularly among largely middle-aged and cognitively normal at baseline individuals.

The researchers examined changes in amyloid beta (Aβ) 42/Aβ40, phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau181), and total tau (t-tau) in CSF over an average of 10.7 years (and up to 23 years) among 278 individuals who were largely middle-aged persons who were cognitively normal at baseline.

“To our knowledge, no prior study among initially cognitively normal, primarily middle-aged individuals has described CSF AD biomarker changes over this duration of follow-up,” the researchers write.

During follow-up, 94 individuals who initially had normal cognition developed mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Lower baseline levels of amyloid were associated with greater increases in tau (more strongly in men than women), while accelerations in tau were more closely linked to onset of MCI, the researchers report.

Among individuals who developed MCI, biomarker levels were more abnormal and tau increased to a greater extent prior to the onset of MCI symptoms, they found.

Clear impact of APOE4

The findings also suggest that among APOE4 carriers, amyloid onset occurs at an earlier age and rates of amyloid positivity are higher, but there are no differences in rates of change in amyloid over time.

“APOE4 genetic status was not related to changes in CSF beta-amyloid after accounting for the fact that APOE4 carriers have higher rates of amyloid positivity,” said Dr. Pettigrew.

“These findings suggest that APOE4 genetic status shifts the age of onset of amyloid accumulation (with APOE4 carriers having an earlier age of onset compared to non-carriers), but that APOE4 is not related to rates of change in CSF beta-amyloid over time,” she added.

“Thus, cognitively normal APOE4 carriers may be in more advanced preclinical AD stages at younger ages than individuals who are not APOE4 carriers, which is likely relevant for optimizing clinical trial recruitment strategies,” she said.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Pettigrew has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The original article contains a complete list of author disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ALZHEIMER’S AND DEMENTIA

Resilience and mind-body interventions in late-life depression

Resilience has been defined as the ability to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity, acute stress, or trauma.1 Originally conceived as an inborn trait characteristic, resilience is now conceptualized as a dynamic, multidimensional capacity influenced by the interactions between internal factors (eg, personality, cognitive capacity, physical health) and environmental resources (eg, social status, financial stability).2,3 Resilience in older adults (typically defined as age ≥65) can improve the prognosis and outcomes for physical and mental conditions.4 The construct is closely aligned with “successful aging” and can be fostered in older adults, leading to improved physical and mental health and well-being.5

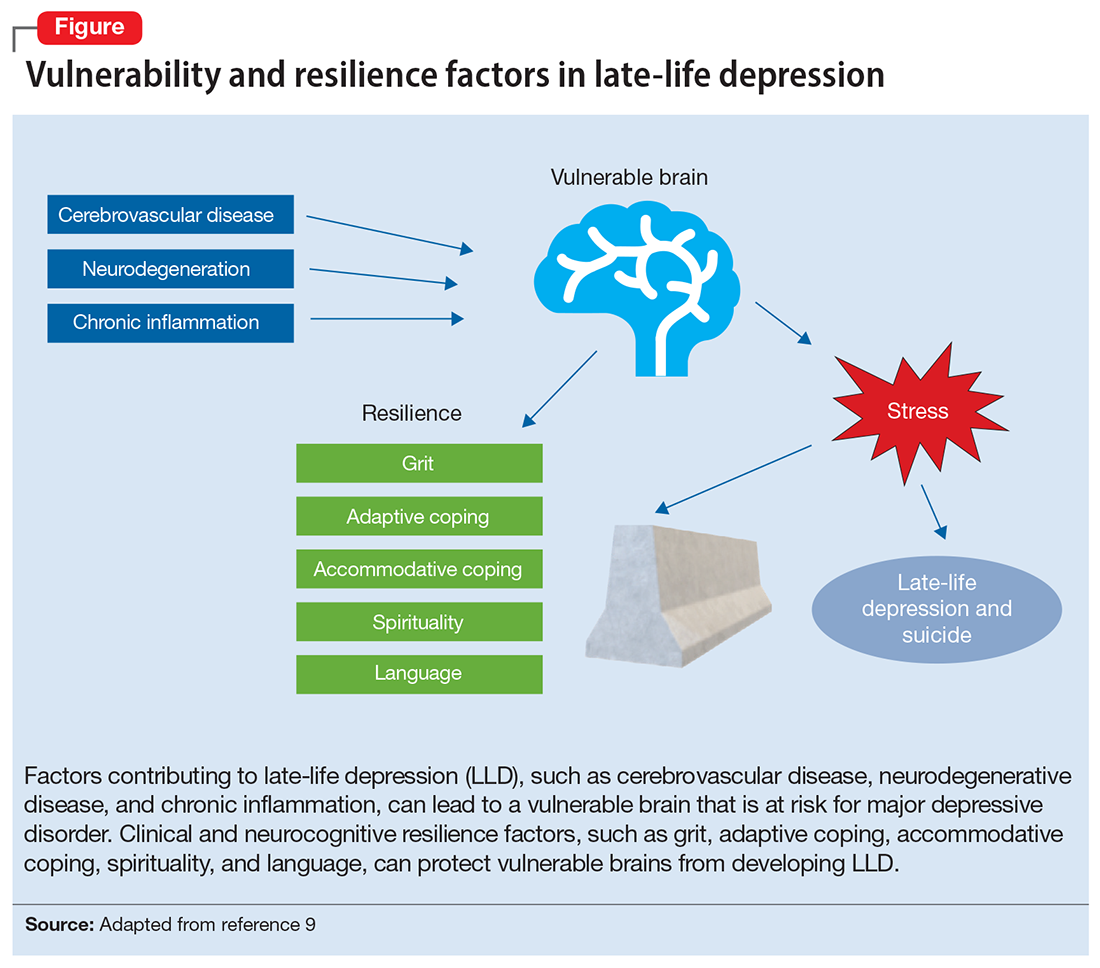

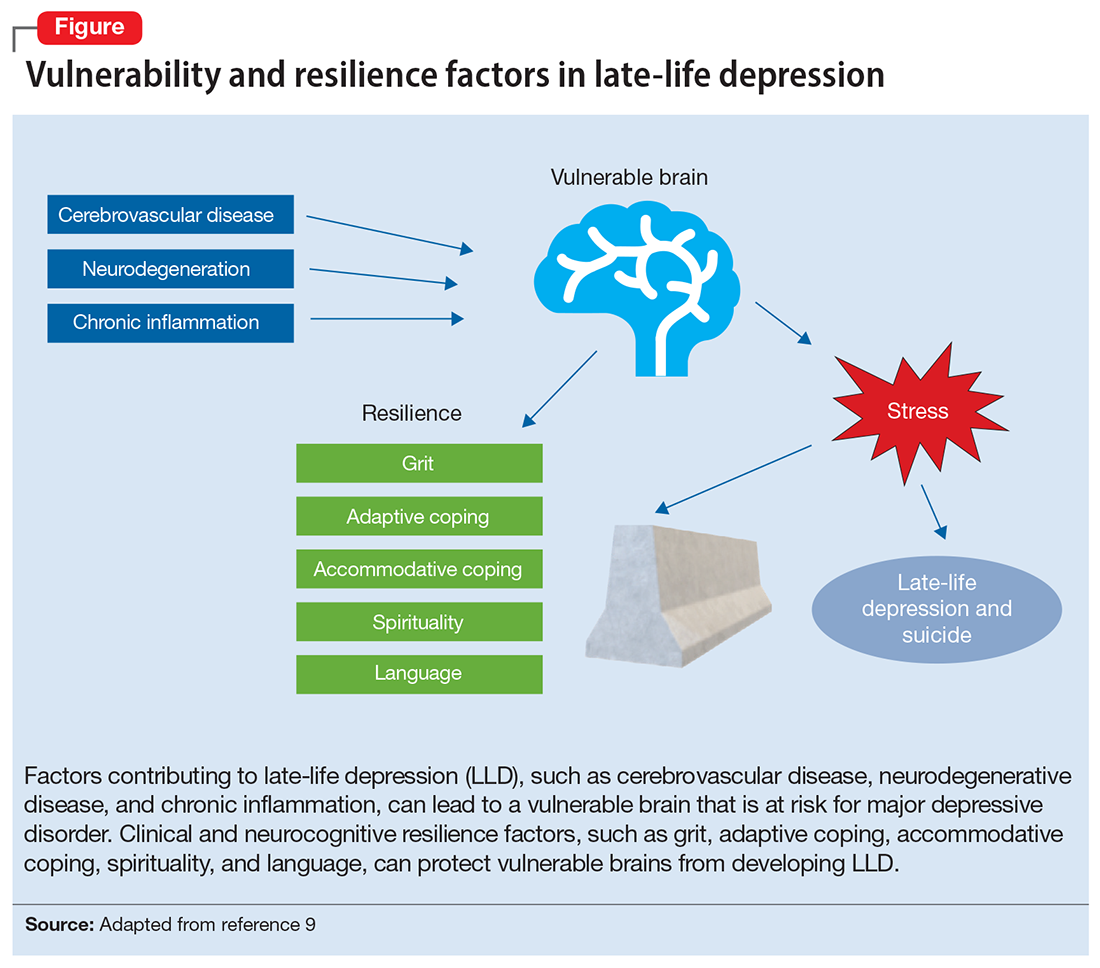

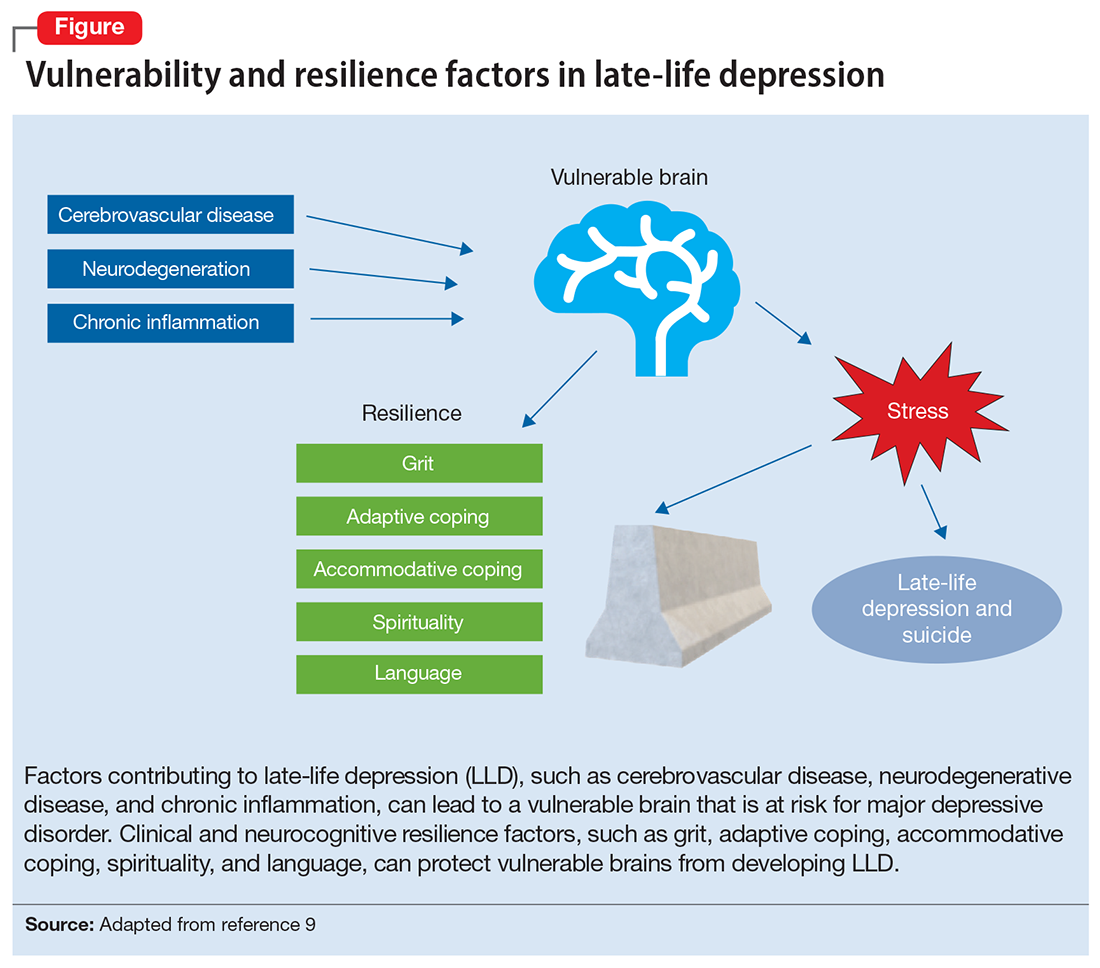

While initially resilience was conceptualized as the opposite of depressive states, recent research has identified resilience in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD) as the net effects of various psychosocial and biological variables that decrease the risk of onset, relapse, or depressive illness severity and increase the probability or speed of recovery.6 Late-life depression (LLD) in adults age >65 is a common and debilitating disease, often leading to decreased psychological well-being, increased cognitive decline, and excess mortality.7,8 LLD is associated with several factors, such as cerebrovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease, and inflammation, all of which could contribute to brain vulnerability and an increased risk of depression.9 Physical and cognitive engagement, physical activity, and high brain reserve have been shown to confer resilience to affective and cognitive changes in older adults, despite brain vulnerability.9

The greatest levels of resilience have been observed in individuals in their fifth decade of life and later,4,10 with high levels of resilience significantly contributing to longevity5; however, little is known about which factors contribute to heterogeneity in resilience characteristics and outcomes.4 Furthermore, the concept of resilience continues to raise numerous questions, including:

- how resilience should be measured or defined

- what factors promote or deter the development of resilience

- the effects of resilience on various health and psychological outcomes

- which interventions are effective in enhancing resilience in older adults.4

In this article, we describe resilience in older adults with LLD, its clinical and neurocognitive correlates, and underlying neurobiological and immunological biomarkers. We also examine resilience-building interventions, such as mind-body therapies (MBTs), that have been shown to enhance resilience by promoting positive perceptions of difficult experiences and challenges.

Clinical and neurocognitive correlates of resilience

Resilience varies substantially among older adults with LLD as well as across the lifespan of an individual.11 Identifying clinical components and predictors of resilience may usefully inform the development and testing of interventions to prevent and treat LLD.11 One tool widely used to measure resilience—the self-report Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)12— has been found to have clinically relevant characteristics.1,11 Using data from 337 older adults with LLD, Laird et al11 performed an exploratory factor analysis of the CD-RISC and found a 4-factor model:

- grit

- adaptive coping self-efficacy

- accommodative coping self-efficacy

- spirituality.1,11

Having a strong sense of purpose and not being easily discouraged by failure were items characteristic of grit.1,11 The preference to take the lead in problem-solving was typical of items loading on adaptive coping self-efficacy, while accommodative coping self-efficacy measured flexibility, cognitive reframing, a sense of humor, and acceptance in the face of uncontrollable stress.1,11 Finally, the belief that “things happen for a reason” and that “sometimes fate or God can help me” are characteristics of spirituality. 1,11 Using a multivariate model, the greatest variance in total resilience scores was explained by less depression, less apathy, higher quality of life, non-White race, and, somewhat counterintuitively, greater medical comorbidity.1,11 Thus, interventions designed to help older adults cultivate grit, active coping, accommodative coping, and spirituality may enhance resilience in LLD.

Resilience may also be positively associated with cognitive functioning and could be neuroprotective in LLD.13 Laird et al13 investigated associations between baseline resilience and several domains of neurocognitive functioning in 288 older adults with LLD. Several positive associations were found between measured language performance and total resilience, active coping, and accommodative coping.13 Additionally, total resilience and accommodative coping were significantly associated with a lower self-reported frequency of forgetfulness, a subjective measure of memory used in this study.13 Together, these results suggest that interventions targeting language might be useful to improve coping in LLD.13 Another interesting finding was that the resilience subdomain of spirituality was negatively associated with memory, language, and executive functioning performance.13 A distinction must be made between religious attendance (eg, regular attendance at religious institutions) vs religious beliefs, which may account for the previously reported associations between spirituality and improved cognition.13

Continue to: Self-reported resilience...

Self-reported resilience may also predict greater responsivity to antidepressant medication in patients with LLD.14 Older adults with LLD and greater self-reported baseline resilience were more likely to experience improvement or remission from depression with antidepressant treatment.14 This is congruent with conceptualizations of resilience as “the ability to adapt to and recover from stress.”14,15 Of the 4 identified resilience factors (grit, adaptive coping, accommodative coping, and spirituality), it appears that accommodative coping predicts LLD treatment response and remission.14 The unique ability to accommodate is associated with better mental health outcomes in the face of uncontrollable stress.14,16-18 Older adults appear to engage in more accommodative coping due to frequent uncontrollable stress and aging-related physiological changes (eg, sleep changes, chronic pain, declining cognition). This could make accommodative coping especially important in this population.14,19

The Figure, adapted from Weisenbach et al,9 exhibits factors that contribute to LLD, including cerebrovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and chronic inflammation, all of which can lead to a vulnerable aging brain that is at higher risk for depression, particularly within the context of stress. Clinical and neurocognitive factors associated with resilience can help buffer vulnerable brains from developing depression.

Neurobiological biomarkers of resilience in

Gross anatomical indicators: Findings from neuroimaging

The neurobiology underlying psychological resilience involves brain networks associated with stress response, negative affect, and emotional control.19 Increased amygdala reactivity and amygdala frontal connectivity are often implicated in neurobiological models of resilience.20 Leaver et al20 correlated psychological resilience measures with amygdala function in 48 depressed vs nondepressed individuals using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Specifically, they targeted the basolateral, centromedial, and superficial nuclei groups of the amygdala while comparing the 2 groups based on resilience scores (CD-RISC), depressive symptom severity, and depression status.20 A significant correlation was identified between resilience and connectivity between the superficial group of amygdala nuclei and the ventral default mode network (VDMN).20 High levels of psychological resilience were associated with lower basal amygdala activity and decreased connectivity between amygdala nuclei and the VDMN.20 Additionally, lower depressive symptoms were associated with higher connectivity between the amygdalae and the dorsal frontal networks.20 These results suggest a complex relationship between amygdala activity, dorsal frontal regions, resilience, and LLD.20

Vlasova et al21 further addressed the multifactorial character of psychological resilience. The associations between the 4 factors of resilience and the regional integrity of white matter in older adults with LLD were examined using diffusion-weighted MRI.21 Grit was found to be associated with greater white matter integrity in the genu of the corpus callosum and cingulum bundle in LLD.21 There was also a positive association between grit and fractional anisotropy (FA) in the callosal region connecting the prefrontal cortex and FA in the cingulum fibers.21 However, results regarding the FA in the cingulum fibers did not survive correction for multiple comparisons and should be considered with caution, pending further research.21

Continue to: Stress response biomarkers of resilience

Stress response biomarkers of resilience

Stress response biomarkers include endocrine, immune, and inflammatory indices. Stress has been identified as a factor in inflammatory responses. Stress-related overstimulation of the HPA axis may increase the risk of LLD.22 Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between increased levels of peripheral proinflammatory cytokines and depressive symptoms in older adults.23 Interleukin-6 (IL-6) has been increasingly linked with depressive symptoms and poor memory performance in older adults.9 There also appears to be an interaction of inflammatory and vascular processes predisposing to LLD, as increased levels of IL-6 and C-reactive protein have been associated with higher white matter pathology.9 Additionally, proinflammatory cytokines impact monoamine neurotransmitter pathways, leading to a reduction in tryptophan and serotonin synthesis, disruption of glucocorticoid receptors, and a decrease in hippocampal neurotrophic support.9 Alexopoulos et al24 further explain that a prolonged CNS immune response can affect emotional and cognitive network functions related to LLD and has a role in the etiology of depressive symptoms in older adults.

Cardiovascular comorbidity and autonomic nervous system dysfunction

Many studies have revealed evidence of a bidirectional association between cardiovascular disease and depression.25 Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) is an underlying mechanism that could explain the link between cardiovascular risk and MDD via heart rate variability (HRV), though research examining age-related capacities provide conflicting data.25,26 HRV is a surrogate index of resting cardiac vagal outflow that represents the ability of the ANS to adapt to psychological, social, and physical environmental changes.27 Higher overall HRV is associated with greater self-regulating capacity, including behavioral, cognitive, and emotional control.28 Additionally, higher HRV may serve as a biomarker of resilience to the development of stress-related disorders such as MDD. Recent studies have shown an overall reduction in HRV in older adults with LLD.29 When high- and low-frequency HRV were investigated separately, only low-frequency HRV was significantly reduced in patients with depression.29 One explanation is that older adults with depression have impaired or reduced baroreflex sensitivity and gain, which is often associated with an increased risk of mortality following cardiac events.30 More research is needed to examine the complex processes required to better characterize the correlation between resilience in cardiovascular disease and autonomic dysfunction.

The Box6,31,32 describes the relationship between markers of cellular health and resilience.

Box

Among the biomarkers of resilience, telomere length and telomerase activity serve as biomarkers of biological aging that can differ from the chronological age and mark successful anti-aging, stress-reducing strategies.31 Telomerase, the cellular enzyme that regulates the health of cells when they reproduce (preserving the telomeres, repetitive DNA strands at the ends of chromosomes), is associated with overall cell health and cellular biological age.31 When telomerase is reduced, the telomeres in a cell are clipped, causing the cells to age more rapidly as the telomeres get shorter through the process of cellular reproduction.31 Psychological stress may play a significant role in telomerase production and subsequent telomere length.32 Lavretsky et al32 evaluated the effect of brief daily yogic meditation on depressive symptoms and immune cell telomerase activity in a family of dementia caregivers with mild depressive symptoms. Brief daily meditation practice led to significant lower levels of depressive symptoms that was accompanied by an increase in telomerase activity, suggesting improvement in stress-induced cellular aging.6,32

Mind-body therapies

There is increasing interest in improving older adults’ physical and emotional well-being while promoting resilience through stress-reducing lifestyle interventions such as MBTs.33 Because MBTs are often considered a natural and safer option compared to conventional medicine, these interventions are rapidly gaining popularity in the United States.33,34 According to a 2017 National Health Survey, there were 5% to 10% increases in the use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractic care from 2012 to 2017, with growing evidence supporting MBTs as minimally invasive, cost-effective approaches for managing stress and neurocognitive disorders.35 In contrast to pharmacologic approaches, MBTs can be used to train individuals to self-regulate in the face of adversity and stress, thus increasing their resilience.

MBTs can be divided into mindful movement exercises and meditative practices. Mindful movement exercises include yoga, tai chi, and qigong. Meditative practices that do not include movement include progressive relaxation, mindfulness, meditation, and acceptance therapies. On average, both mindful movement exercise (eg, yoga) and multicomponent mindfulness-based interventions (eg, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction [MBSR], and mindfulness-based relapse prevention) can be as effective as other active treatments for psychiatric disorders such as MDD, anxiety, and substance use disorders.36,37 MBSR specifically has been shown to increase empathy, self-control, self-compassion, relationship quality, mindfulness, and spirituality as well as decrease rumination in healthy older adults.38 This suggests that MBSR can help strengthen the 4 factors of resilience.

Continue to: Research has also begun...

Research has also begun to evaluate the neurobiological mechanisms by which meditative therapies enhance resilience in mental health disorders, and several promising mechanistic domains (neural, hormonal, immune, cellular, and cardiovascular) have been identified.39 The physical yoga discipline includes asanas (postures), pranayama (breathing techniques), and dhyana (meditation). With the inclusion of mindfulness training, yoga involves the practice of meditation as well as the dynamic combination of proprioceptive and interoceptive awareness, resulting in both attention and profound focus.40 Dedicated yoga practice allows an individual to develop skills to withdraw the senses (pratyahara), concentrate the mind (dharana), and establish unwavering awareness (dhyana).41 The physical and cognitive benefits associated with yoga and mindfulness may be due to mechanisms including pranayama and activation of the parasympathetic nervous system; meditative or contemplative practices; increased body perception; stronger functional connectivity within the basal ganglia; or neuroplastic effects of increased grey matter volume and amygdala with regional enlargement.41 The new learning aspect of yoga practice may contribute to enhancing or improving various aspects of cognition, although the mechanisms are yet to be clarified.

Continued research in this area will promote the integration of MBTs into mainstream clinical practice and help alleviate the increased chronic health burden of an aging population. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, public interest in improving resilience and mental health42 can be supported by MBTs that can improve coping with the stress of the pandemic and enhance critical organ function (eg, lungs, heart, brain).43,44 As a result of these limitations, many resources and health care services have used telehealth and virtual platforms to adapt to these challenges and continue offering MBTs.45

Enhancing resilience to improve clinical outcomes

Increasing our understanding of clinical, neurocognitive, and neurobiological markers of resilience in older adults with and without depression could inform the development of interventions that treat and prevent mood and cognitive disorders of aging. Furthermore, stress reduction, decreased inflammation, and improved emotional regulation may have direct neuroplastic effects on the brain, leading to greater resilience. Complementary use of MBTs combined with standard antidepressant treatment may allow for additional improvement in clinical outcomes of LLD, including resilience, quality of life, general health, and cognitive function. Additional research testing the efficacy of those interventions designed to improve resilience in older adults with mood and mental disorders is needed.

Bottom Line

Identifying the clinical, neurocognitive, and neurobiological biomarkers of resilience in late-life depression could aid in the development of targeted interventions that treat and prevent mood and cognitive disorders of aging. Mind-body interventions can help boost resilience and improve outcomes in geriatric patients with mood and cognitive disorders.

Related Resources

- Lavretsky H. Resilience and Aging: Research and Practice. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014.

- Lavretsky H, Sajatovic M, Reynolds CF, eds. Complementary and Integrative Therapies for Mental Health and Aging. Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Eyre HA, Berk M, Lavretsky H, et al, eds. Convergence Mental Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach to Innovation. Oxford University Press; 2021.

- UCLA Jane & Terry Semel Institute for Neuroscience & Human Behavior. Late-life Depression, Stress, and Wellness Research Program. https://www.semel.ucla.edu/latelife

1. Reynolds CF. Promoting resilience, reducing depression in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(2):169-171.

2. Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2011;21(2):152-169.

3. Southwick SM, Charney DS. The science of resilience: implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. Science. 2012;338(6103):79-82.

4. Dunn LB, Predescu I. Resilience: a rich concept in need of research comment on: “Neurocognitive correlates of resilience in late-life depression” (by Laird et al.). Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(1):18-20.

5. Harmell AL, Kamat R, Jeste DV, et al. Resilience-building interventions for successful and positive aging. In: Lavretsky H, Sajatovic M, Reynolds C III, eds. Complementary and Integrative Therapies for Mental Health and Aging. Oxford University Press; 2015:305-316.

6. Laird KT, Krause B, Funes C, et al. Psychobiological factors of resilience and depression in late life. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):88.

7. Byers AL, Yaffe K. Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(6):323-331.

8. Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD, Stump TE, et al. Mortality, symptoms, and functional impairment in late-life depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(11):746-752.

9. Weisenbach SL, Kumar A. Current understanding of the neurobiology and longitudinal course of geriatric depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(9):463.

10. Southwick SM, Litz BT, Charney D, et al. Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan. Cambridge University Press; 2011.

11. Laird KT, Lavretsky H, Paholpak P, et al. Clinical correlates of resilience factors in geriatric depression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(2):193-202.

12. Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82.

13. Laird KT, Lavretsky H, Wu P, et al. Neurocognitive correlates of resilience in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(1):12-17.

14. Laird KT, Lavretsky H, St Cyr N, et al. Resilience predicts remission in antidepressant treatment of geriatric depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(12):1596-1603.

15. Waugh CE, Koster EH. A resilience framework for promoting stable remission from depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;41:49-60.

16. Boerner K. Adaptation to disability among middle-aged and older adults: the role of assimilative and accommodative coping. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(1):P35-P42.

17. Zakowski SG, Hall MH, Klein LC, et al. Appraised control, coping, and stress in a community sample: a test of the goodness-of-fit hypothesis. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(3):158-165.

18. Cheng C, Lau HB, Chan MP. Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(6):1582-1607.

19. Stokes SA, Gordon SE. Common stressors experienced by the well elderly. Clinical implications. J Gerontol Nurs. 2003;29(5):38-46.

20. Leaver AM, Yang H, Siddarth P, et al. Resilience and amygdala function in older healthy and depressed adults. J Affect Disord. 2018;237:27-34.

21. Vlasova RM, Siddarth P, Krause B, et al. Resilience and white matter integrity in geriatric depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(8):874-883.

22. Chopra K, Kumar B, Kuhad A. Pathobiological targets of depression. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15(4):379-400.

23. Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, Carrascón L, O’Brien JT, et al. Peripheral inflammatory parameters in late-life depression: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12):2022.

24. Alexopoulos GS, Morimoto SS. The inflammation hypothesis in geriatric depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(11):1109-1118.

25. Carney RM, Freedland KE, Sheline YI, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: a review for cardiologists. Clin Cardiol. 1997;20(3):196-200.

26. Carney RM, Freedland KE, Steinmeyer BC, et al. Nighttime heart rate predicts response to depression treatment in patients with coronary heart disease. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:165-171.

27. Appelhans BM, Luecken LJ. Heart rate variability as an index of regulated emotional responding. Rev Gen Psych. 2006;10(3):229-240.

28. Holzman JB, Bridgett DJ. Heart rate variability indices as bio-markers of top-down self-regulatory mechanisms: a meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;74(Pt A):233-255.

29. Brown L, Karmakar C, Gray R, et al. Heart rate variability alterations in late life depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:456-466.

30. La Rovere MT, Bigger JT Jr, Marcus FI, et al. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Lancet. 1998;351(1901):478-484.

31. Chakravarti D, LaBella KA, DePinho RA. Telomeres: history, health, and hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2021;184(2):306-322.

32. Lavretsky H, Epel ES, Siddarth P, et al. A pilot study of yogic meditation for family dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms: effects on mental health, cognition, and telomerase activity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):57-65.

33. Siddiqui MJ, Min CS, Verma RK, et al. Role of complementary and alternative medicine in geriatric care: a mini review. Pharmacogn Rev. 2014;8(16):81-87.

34. Nguyen SA, Lavretsky H. Emerging complementary and integrative therapies for geriatric mental health. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):447-470.

35. Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Black LI, et al. Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among U.S. adults aged 18 and over. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;(325):1-8.

36. Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):739-749.

37. Ramadas E, de Lima MP, Caetano T, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based relapse prevention in individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2021;11(10):133.

38. Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(5):593-600.

39. Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96110.

40. Chobe S, Chobe M, Metri K, et al. Impact of yoga on cognition and mental health among elderly: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2020;52:102421.

41. Brunner D, Abramovitch A, Etherton J. A yoga program for cognitive enhancement. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182366.

42. Dai J, Sang X, Menhas R, et al. The influence of COVID-19 pandemic on physical health-psychological health, physical activity, and overall well-being: the mediating role of emotional regulation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:667461.

43. Grolli RE, Mingoti MED, Bertollo AG, et al. Impact of COVID-19 in the mental health in elderly: psychological and biological updates. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58(5):1905-1916.

44. Johansson A, Mohamed MS, Moulin TC, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a comprehensive literature review and discussion of mechanisms. J Neuroimmunol. 2021;358:577658.

45. Pandya SP. Older women and wellbeing through the pandemic: examining the effect of daily online yoga lessons. Health Care Women Int. 2021;42(11):1255-1278.

Resilience has been defined as the ability to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity, acute stress, or trauma.1 Originally conceived as an inborn trait characteristic, resilience is now conceptualized as a dynamic, multidimensional capacity influenced by the interactions between internal factors (eg, personality, cognitive capacity, physical health) and environmental resources (eg, social status, financial stability).2,3 Resilience in older adults (typically defined as age ≥65) can improve the prognosis and outcomes for physical and mental conditions.4 The construct is closely aligned with “successful aging” and can be fostered in older adults, leading to improved physical and mental health and well-being.5

While initially resilience was conceptualized as the opposite of depressive states, recent research has identified resilience in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD) as the net effects of various psychosocial and biological variables that decrease the risk of onset, relapse, or depressive illness severity and increase the probability or speed of recovery.6 Late-life depression (LLD) in adults age >65 is a common and debilitating disease, often leading to decreased psychological well-being, increased cognitive decline, and excess mortality.7,8 LLD is associated with several factors, such as cerebrovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease, and inflammation, all of which could contribute to brain vulnerability and an increased risk of depression.9 Physical and cognitive engagement, physical activity, and high brain reserve have been shown to confer resilience to affective and cognitive changes in older adults, despite brain vulnerability.9

The greatest levels of resilience have been observed in individuals in their fifth decade of life and later,4,10 with high levels of resilience significantly contributing to longevity5; however, little is known about which factors contribute to heterogeneity in resilience characteristics and outcomes.4 Furthermore, the concept of resilience continues to raise numerous questions, including:

- how resilience should be measured or defined

- what factors promote or deter the development of resilience

- the effects of resilience on various health and psychological outcomes

- which interventions are effective in enhancing resilience in older adults.4

In this article, we describe resilience in older adults with LLD, its clinical and neurocognitive correlates, and underlying neurobiological and immunological biomarkers. We also examine resilience-building interventions, such as mind-body therapies (MBTs), that have been shown to enhance resilience by promoting positive perceptions of difficult experiences and challenges.

Clinical and neurocognitive correlates of resilience

Resilience varies substantially among older adults with LLD as well as across the lifespan of an individual.11 Identifying clinical components and predictors of resilience may usefully inform the development and testing of interventions to prevent and treat LLD.11 One tool widely used to measure resilience—the self-report Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)12— has been found to have clinically relevant characteristics.1,11 Using data from 337 older adults with LLD, Laird et al11 performed an exploratory factor analysis of the CD-RISC and found a 4-factor model:

- grit

- adaptive coping self-efficacy

- accommodative coping self-efficacy

- spirituality.1,11

Having a strong sense of purpose and not being easily discouraged by failure were items characteristic of grit.1,11 The preference to take the lead in problem-solving was typical of items loading on adaptive coping self-efficacy, while accommodative coping self-efficacy measured flexibility, cognitive reframing, a sense of humor, and acceptance in the face of uncontrollable stress.1,11 Finally, the belief that “things happen for a reason” and that “sometimes fate or God can help me” are characteristics of spirituality. 1,11 Using a multivariate model, the greatest variance in total resilience scores was explained by less depression, less apathy, higher quality of life, non-White race, and, somewhat counterintuitively, greater medical comorbidity.1,11 Thus, interventions designed to help older adults cultivate grit, active coping, accommodative coping, and spirituality may enhance resilience in LLD.

Resilience may also be positively associated with cognitive functioning and could be neuroprotective in LLD.13 Laird et al13 investigated associations between baseline resilience and several domains of neurocognitive functioning in 288 older adults with LLD. Several positive associations were found between measured language performance and total resilience, active coping, and accommodative coping.13 Additionally, total resilience and accommodative coping were significantly associated with a lower self-reported frequency of forgetfulness, a subjective measure of memory used in this study.13 Together, these results suggest that interventions targeting language might be useful to improve coping in LLD.13 Another interesting finding was that the resilience subdomain of spirituality was negatively associated with memory, language, and executive functioning performance.13 A distinction must be made between religious attendance (eg, regular attendance at religious institutions) vs religious beliefs, which may account for the previously reported associations between spirituality and improved cognition.13

Continue to: Self-reported resilience...

Self-reported resilience may also predict greater responsivity to antidepressant medication in patients with LLD.14 Older adults with LLD and greater self-reported baseline resilience were more likely to experience improvement or remission from depression with antidepressant treatment.14 This is congruent with conceptualizations of resilience as “the ability to adapt to and recover from stress.”14,15 Of the 4 identified resilience factors (grit, adaptive coping, accommodative coping, and spirituality), it appears that accommodative coping predicts LLD treatment response and remission.14 The unique ability to accommodate is associated with better mental health outcomes in the face of uncontrollable stress.14,16-18 Older adults appear to engage in more accommodative coping due to frequent uncontrollable stress and aging-related physiological changes (eg, sleep changes, chronic pain, declining cognition). This could make accommodative coping especially important in this population.14,19

The Figure, adapted from Weisenbach et al,9 exhibits factors that contribute to LLD, including cerebrovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and chronic inflammation, all of which can lead to a vulnerable aging brain that is at higher risk for depression, particularly within the context of stress. Clinical and neurocognitive factors associated with resilience can help buffer vulnerable brains from developing depression.

Neurobiological biomarkers of resilience in

Gross anatomical indicators: Findings from neuroimaging

The neurobiology underlying psychological resilience involves brain networks associated with stress response, negative affect, and emotional control.19 Increased amygdala reactivity and amygdala frontal connectivity are often implicated in neurobiological models of resilience.20 Leaver et al20 correlated psychological resilience measures with amygdala function in 48 depressed vs nondepressed individuals using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Specifically, they targeted the basolateral, centromedial, and superficial nuclei groups of the amygdala while comparing the 2 groups based on resilience scores (CD-RISC), depressive symptom severity, and depression status.20 A significant correlation was identified between resilience and connectivity between the superficial group of amygdala nuclei and the ventral default mode network (VDMN).20 High levels of psychological resilience were associated with lower basal amygdala activity and decreased connectivity between amygdala nuclei and the VDMN.20 Additionally, lower depressive symptoms were associated with higher connectivity between the amygdalae and the dorsal frontal networks.20 These results suggest a complex relationship between amygdala activity, dorsal frontal regions, resilience, and LLD.20

Vlasova et al21 further addressed the multifactorial character of psychological resilience. The associations between the 4 factors of resilience and the regional integrity of white matter in older adults with LLD were examined using diffusion-weighted MRI.21 Grit was found to be associated with greater white matter integrity in the genu of the corpus callosum and cingulum bundle in LLD.21 There was also a positive association between grit and fractional anisotropy (FA) in the callosal region connecting the prefrontal cortex and FA in the cingulum fibers.21 However, results regarding the FA in the cingulum fibers did not survive correction for multiple comparisons and should be considered with caution, pending further research.21

Continue to: Stress response biomarkers of resilience

Stress response biomarkers of resilience

Stress response biomarkers include endocrine, immune, and inflammatory indices. Stress has been identified as a factor in inflammatory responses. Stress-related overstimulation of the HPA axis may increase the risk of LLD.22 Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between increased levels of peripheral proinflammatory cytokines and depressive symptoms in older adults.23 Interleukin-6 (IL-6) has been increasingly linked with depressive symptoms and poor memory performance in older adults.9 There also appears to be an interaction of inflammatory and vascular processes predisposing to LLD, as increased levels of IL-6 and C-reactive protein have been associated with higher white matter pathology.9 Additionally, proinflammatory cytokines impact monoamine neurotransmitter pathways, leading to a reduction in tryptophan and serotonin synthesis, disruption of glucocorticoid receptors, and a decrease in hippocampal neurotrophic support.9 Alexopoulos et al24 further explain that a prolonged CNS immune response can affect emotional and cognitive network functions related to LLD and has a role in the etiology of depressive symptoms in older adults.

Cardiovascular comorbidity and autonomic nervous system dysfunction

Many studies have revealed evidence of a bidirectional association between cardiovascular disease and depression.25 Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) is an underlying mechanism that could explain the link between cardiovascular risk and MDD via heart rate variability (HRV), though research examining age-related capacities provide conflicting data.25,26 HRV is a surrogate index of resting cardiac vagal outflow that represents the ability of the ANS to adapt to psychological, social, and physical environmental changes.27 Higher overall HRV is associated with greater self-regulating capacity, including behavioral, cognitive, and emotional control.28 Additionally, higher HRV may serve as a biomarker of resilience to the development of stress-related disorders such as MDD. Recent studies have shown an overall reduction in HRV in older adults with LLD.29 When high- and low-frequency HRV were investigated separately, only low-frequency HRV was significantly reduced in patients with depression.29 One explanation is that older adults with depression have impaired or reduced baroreflex sensitivity and gain, which is often associated with an increased risk of mortality following cardiac events.30 More research is needed to examine the complex processes required to better characterize the correlation between resilience in cardiovascular disease and autonomic dysfunction.

The Box6,31,32 describes the relationship between markers of cellular health and resilience.

Box

Among the biomarkers of resilience, telomere length and telomerase activity serve as biomarkers of biological aging that can differ from the chronological age and mark successful anti-aging, stress-reducing strategies.31 Telomerase, the cellular enzyme that regulates the health of cells when they reproduce (preserving the telomeres, repetitive DNA strands at the ends of chromosomes), is associated with overall cell health and cellular biological age.31 When telomerase is reduced, the telomeres in a cell are clipped, causing the cells to age more rapidly as the telomeres get shorter through the process of cellular reproduction.31 Psychological stress may play a significant role in telomerase production and subsequent telomere length.32 Lavretsky et al32 evaluated the effect of brief daily yogic meditation on depressive symptoms and immune cell telomerase activity in a family of dementia caregivers with mild depressive symptoms. Brief daily meditation practice led to significant lower levels of depressive symptoms that was accompanied by an increase in telomerase activity, suggesting improvement in stress-induced cellular aging.6,32

Mind-body therapies

There is increasing interest in improving older adults’ physical and emotional well-being while promoting resilience through stress-reducing lifestyle interventions such as MBTs.33 Because MBTs are often considered a natural and safer option compared to conventional medicine, these interventions are rapidly gaining popularity in the United States.33,34 According to a 2017 National Health Survey, there were 5% to 10% increases in the use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractic care from 2012 to 2017, with growing evidence supporting MBTs as minimally invasive, cost-effective approaches for managing stress and neurocognitive disorders.35 In contrast to pharmacologic approaches, MBTs can be used to train individuals to self-regulate in the face of adversity and stress, thus increasing their resilience.

MBTs can be divided into mindful movement exercises and meditative practices. Mindful movement exercises include yoga, tai chi, and qigong. Meditative practices that do not include movement include progressive relaxation, mindfulness, meditation, and acceptance therapies. On average, both mindful movement exercise (eg, yoga) and multicomponent mindfulness-based interventions (eg, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction [MBSR], and mindfulness-based relapse prevention) can be as effective as other active treatments for psychiatric disorders such as MDD, anxiety, and substance use disorders.36,37 MBSR specifically has been shown to increase empathy, self-control, self-compassion, relationship quality, mindfulness, and spirituality as well as decrease rumination in healthy older adults.38 This suggests that MBSR can help strengthen the 4 factors of resilience.

Continue to: Research has also begun...

Research has also begun to evaluate the neurobiological mechanisms by which meditative therapies enhance resilience in mental health disorders, and several promising mechanistic domains (neural, hormonal, immune, cellular, and cardiovascular) have been identified.39 The physical yoga discipline includes asanas (postures), pranayama (breathing techniques), and dhyana (meditation). With the inclusion of mindfulness training, yoga involves the practice of meditation as well as the dynamic combination of proprioceptive and interoceptive awareness, resulting in both attention and profound focus.40 Dedicated yoga practice allows an individual to develop skills to withdraw the senses (pratyahara), concentrate the mind (dharana), and establish unwavering awareness (dhyana).41 The physical and cognitive benefits associated with yoga and mindfulness may be due to mechanisms including pranayama and activation of the parasympathetic nervous system; meditative or contemplative practices; increased body perception; stronger functional connectivity within the basal ganglia; or neuroplastic effects of increased grey matter volume and amygdala with regional enlargement.41 The new learning aspect of yoga practice may contribute to enhancing or improving various aspects of cognition, although the mechanisms are yet to be clarified.

Continued research in this area will promote the integration of MBTs into mainstream clinical practice and help alleviate the increased chronic health burden of an aging population. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, public interest in improving resilience and mental health42 can be supported by MBTs that can improve coping with the stress of the pandemic and enhance critical organ function (eg, lungs, heart, brain).43,44 As a result of these limitations, many resources and health care services have used telehealth and virtual platforms to adapt to these challenges and continue offering MBTs.45

Enhancing resilience to improve clinical outcomes

Increasing our understanding of clinical, neurocognitive, and neurobiological markers of resilience in older adults with and without depression could inform the development of interventions that treat and prevent mood and cognitive disorders of aging. Furthermore, stress reduction, decreased inflammation, and improved emotional regulation may have direct neuroplastic effects on the brain, leading to greater resilience. Complementary use of MBTs combined with standard antidepressant treatment may allow for additional improvement in clinical outcomes of LLD, including resilience, quality of life, general health, and cognitive function. Additional research testing the efficacy of those interventions designed to improve resilience in older adults with mood and mental disorders is needed.

Bottom Line

Identifying the clinical, neurocognitive, and neurobiological biomarkers of resilience in late-life depression could aid in the development of targeted interventions that treat and prevent mood and cognitive disorders of aging. Mind-body interventions can help boost resilience and improve outcomes in geriatric patients with mood and cognitive disorders.

Related Resources

- Lavretsky H. Resilience and Aging: Research and Practice. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014.

- Lavretsky H, Sajatovic M, Reynolds CF, eds. Complementary and Integrative Therapies for Mental Health and Aging. Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Eyre HA, Berk M, Lavretsky H, et al, eds. Convergence Mental Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach to Innovation. Oxford University Press; 2021.

- UCLA Jane & Terry Semel Institute for Neuroscience & Human Behavior. Late-life Depression, Stress, and Wellness Research Program. https://www.semel.ucla.edu/latelife

Resilience has been defined as the ability to adapt and thrive in the face of adversity, acute stress, or trauma.1 Originally conceived as an inborn trait characteristic, resilience is now conceptualized as a dynamic, multidimensional capacity influenced by the interactions between internal factors (eg, personality, cognitive capacity, physical health) and environmental resources (eg, social status, financial stability).2,3 Resilience in older adults (typically defined as age ≥65) can improve the prognosis and outcomes for physical and mental conditions.4 The construct is closely aligned with “successful aging” and can be fostered in older adults, leading to improved physical and mental health and well-being.5

While initially resilience was conceptualized as the opposite of depressive states, recent research has identified resilience in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD) as the net effects of various psychosocial and biological variables that decrease the risk of onset, relapse, or depressive illness severity and increase the probability or speed of recovery.6 Late-life depression (LLD) in adults age >65 is a common and debilitating disease, often leading to decreased psychological well-being, increased cognitive decline, and excess mortality.7,8 LLD is associated with several factors, such as cerebrovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease, and inflammation, all of which could contribute to brain vulnerability and an increased risk of depression.9 Physical and cognitive engagement, physical activity, and high brain reserve have been shown to confer resilience to affective and cognitive changes in older adults, despite brain vulnerability.9

The greatest levels of resilience have been observed in individuals in their fifth decade of life and later,4,10 with high levels of resilience significantly contributing to longevity5; however, little is known about which factors contribute to heterogeneity in resilience characteristics and outcomes.4 Furthermore, the concept of resilience continues to raise numerous questions, including:

- how resilience should be measured or defined

- what factors promote or deter the development of resilience

- the effects of resilience on various health and psychological outcomes

- which interventions are effective in enhancing resilience in older adults.4

In this article, we describe resilience in older adults with LLD, its clinical and neurocognitive correlates, and underlying neurobiological and immunological biomarkers. We also examine resilience-building interventions, such as mind-body therapies (MBTs), that have been shown to enhance resilience by promoting positive perceptions of difficult experiences and challenges.

Clinical and neurocognitive correlates of resilience

Resilience varies substantially among older adults with LLD as well as across the lifespan of an individual.11 Identifying clinical components and predictors of resilience may usefully inform the development and testing of interventions to prevent and treat LLD.11 One tool widely used to measure resilience—the self-report Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)12— has been found to have clinically relevant characteristics.1,11 Using data from 337 older adults with LLD, Laird et al11 performed an exploratory factor analysis of the CD-RISC and found a 4-factor model:

- grit

- adaptive coping self-efficacy

- accommodative coping self-efficacy

- spirituality.1,11

Having a strong sense of purpose and not being easily discouraged by failure were items characteristic of grit.1,11 The preference to take the lead in problem-solving was typical of items loading on adaptive coping self-efficacy, while accommodative coping self-efficacy measured flexibility, cognitive reframing, a sense of humor, and acceptance in the face of uncontrollable stress.1,11 Finally, the belief that “things happen for a reason” and that “sometimes fate or God can help me” are characteristics of spirituality. 1,11 Using a multivariate model, the greatest variance in total resilience scores was explained by less depression, less apathy, higher quality of life, non-White race, and, somewhat counterintuitively, greater medical comorbidity.1,11 Thus, interventions designed to help older adults cultivate grit, active coping, accommodative coping, and spirituality may enhance resilience in LLD.

Resilience may also be positively associated with cognitive functioning and could be neuroprotective in LLD.13 Laird et al13 investigated associations between baseline resilience and several domains of neurocognitive functioning in 288 older adults with LLD. Several positive associations were found between measured language performance and total resilience, active coping, and accommodative coping.13 Additionally, total resilience and accommodative coping were significantly associated with a lower self-reported frequency of forgetfulness, a subjective measure of memory used in this study.13 Together, these results suggest that interventions targeting language might be useful to improve coping in LLD.13 Another interesting finding was that the resilience subdomain of spirituality was negatively associated with memory, language, and executive functioning performance.13 A distinction must be made between religious attendance (eg, regular attendance at religious institutions) vs religious beliefs, which may account for the previously reported associations between spirituality and improved cognition.13

Continue to: Self-reported resilience...