User login

Recreational cannabis use: Pleasures and pitfalls

Clinicians may be encountering more cannabis users than before, and may be encountering users with complications hitherto unseen. Several trends may explain this phenomenon: the legal status of cannabis is changing, cannabis today is more potent than in the past, and enthusiasts are conjuring new ways to enjoy this substance.

This article discusses the history, pharmacology, and potential complications of cannabis use.

A LONG AND TANGLED HISTORY

Cannabis is a broad term that refers to the cannabis plant and its preparations, such as marijuana and hashish, as well as to a family of more than 60 bioactive substances called cannabinoids. It is the most commonly used illegal drug in the world, with an estimated 160 million users. Each year, about 2.4 million people in the United States use it for the first time.1,2

Cannabis has been used throughout the world for recreational and spiritual purposes for nearly 5,000 years, beginning with the fabled Celestial Emperors of China. The tangled history of cannabis in America began in the 17th century, when farmers were required by law to grow it as a fiber crop. It later found its way into the US Pharmacopeia for a wide range of indications. During the long prelude to Prohibition in the latter half of the 19th century, the US government became increasingly suspicious of mind-altering substances and began restricting its prescription in 1934, culminating in its designation by the US Food and Drug Administration as a schedule I controlled substance in 1970.

Investigation into the potential medical uses for the different chemicals within cannabis is ongoing, as is debate over its changing legality and usefulness to society. The apparent cognitive dissonance surrounding the use and advocacy of medical marijuana is beyond the scope of this review,3 which will instead restrict itself to what is known of the cannabinoids and to the recreational use of cannabis.

THC IS THE PRINCIPAL PSYCHOACTIVE MOLECULE

Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), first isolated in 1964, was identified as the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis in 2002.4

Two G-protein–linked cannabinoid receptors cloned in the 1990s—CB1 and CB2—were found to be a part of a system of endocannabinoid receptors present throughout the body, from the brain to the immune system to the vas deferens.5 Both receptors inhibit cellular excitation by activating inwardly rectifying potassium channels. These receptors are mostly absent in the brainstem, which may explain why cannabis use rarely causes life-threatening autonomic dysfunction. Although the intoxicating effects of marijuana are mediated by CB1 receptors, the specific mechanisms underlying the cannabis “high” are unclear.6

CANNABINOIDS ARE LIPID-SOLUBLE

The rate of absorption of cannabinoids depends on the route of administration and the type of cannabis product used. When cannabis products are smoked, up to 35% of THC is available, and the average time to peak serum concentration is 8 minutes.7 The peak concentration depends on the dose.

On the other hand, when cannabis products (eg, nabilone, dronabinol) are ingested, absorption is unpredictable because THC is unstable in gastric acid and undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver, which reduces the drug’s bioavailability. Up to 20% of an ingested dose of THC is absorbed, and the time to peak serum concentration averages between 2 and 4 hours. Consequently, many users prefer to smoke cannabis as a means to control the desired effects.

Cannabinoids are lipid-soluble. They accumulate in fatty tissue in a biphasic pattern, initially moving into highly vascularized tissue such as the liver before accumulating in less well-vascularized tissue such as fat. They are then slowly released from fatty tissue as the fat turns over. THC itself has a volume of distribution of about 2.5 to 3.5 L/kg. It crosses the placenta and enters breast milk.8

THC is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, primarily by the enzymes CYP2C9 and CYP3A4. Its primary metabolite, 11-hydroxy-delta-9 THC, is also active, but subsequent metabolism produces many other inactive metabolites. THC is eliminated in feces and urine, and its half-life ranges from 2 to nearly 60 hours.8

A LITTLE ABOUT PLANTS AND STREET NAMES

The plant from which THC and nearly a hundred other chemicals, including cannabinoids, are derived has been called many things over the years:

Hemp is a tall fibrous plant grown for rope and fabric that was used as legal tender in early America. In the mid-19th century, there were over 16 million acres of hemp plantations. Hemp contains very low THC concentrations.

Cannabis is an annual flowering herb that is predominantly diecious (ie, there are male and female plants). After a centuries-long debate among taxonomists, the two principal species are considered to be C sativa and C indica, although today many cannabis cultivars are grown by a great number of breeding enthusiasts.

Concentrations of THC vary widely among cannabis cultivars, ranging historically from around 5% to today’s highly selectively bred species containing more than 30%. Concentrations in seized cannabis have been measured as high as 37%, although the average is around 11%.9 This concentration is defined by the percent of THC per dried mass of plant material tested, usually via gas chromatography.

Hashish is a solid or resinous preparation of the trichomes, or glandular hairs, that grow on the cannabis plant, chiefly on its flowers. Various methods to separate the trichomes from the rest of the plant result in a powder called kief that is then compressed into blocks or bricks. THC concentrations as high as 66% have been measured in nondomestic sources of hashish.9

Hash oil is a further purification, produced by using solvents to dissolve the resin and by filtering out remaining plant material. Evaporating the solvent produces hash oil, sometimes called butane hash oil or honey oil. This process has recently led to an increasing number of home explosions, as people attempt to make the product themselves but do not take suitable precautions when using flammable solvents such as butane. THC concentrations as high as 81% have been measured in nondomestic sources of hash oil.9

Other names for hash oil are dab, wax, and budder. Cannabis enthusiasts refer to the use of hash oil as dabbing, which involves heating a small amount (dab) of the product using a variety of paraphernalia and inhaling the vapor.

IT’S ALL ABOUT GETTING HIGH

For recreational users, the experience has always been about being intoxicated—getting high. The psychological effects range broadly from positive to negative and vary both within and between users, depending on the dose and route of administration. Additional factors that influence the psychological effects include the social and physical settings of drug use and even the user’s expectations. One user’s high is another user’s acute toxic effect.

Although subjective reports of the cannabis experience vary greatly, it typically begins with a feeling of dizziness or lightheadedness followed by a relaxed calm and a feeling of being somewhat “disconnected.” There is a quickening of the sense of humor, described by some as a fatuous euphoria; often there is silly giggling. Awareness of the senses and of music may be increased. Appetite increases, and time seems to pass quickly. Eventually, the user becomes drowsy and experiences decreased attention and difficulty maintaining a coherent conversation. Slowed reaction time and decreased psychomotor activity may also occur. The user may drift into daydreams and eventually fall asleep.

Common negative acute effects of getting high can include mild to severe anxiety and feeling tense or agitated. Clumsiness, headache, and confusion are also possible. Lingering effects the following day may include dry mouth, dry eyes, fatigue, slowed thinking, and slowed recall.6

ACUTE PHYSICAL EFFECTS

Acute physical effects of cannabis use include a rapid onset of increased airway conductance, decreased intraocular pressure, and conjunctival injection. A single cannabis cigarette can also induce cardiovascular effects including a dose-dependent increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Chronic users, however, can experience a decreased heart rate, lower blood pressure, and postural hypotension.

In a personal communication, colleagues in Colorado—where recreational use of cannabis was legalized in 2012—described a sharp increase (from virtually none) in the number of adults presenting to the emergency department with cannabis intoxication since 2012. Their patients experienced palpitations, light-headedness, and severe ataxia lasting as long as 12 hours, possibly reflecting the greater potency of current cannabis products. Most of these patients required only supportive care.

Other acute adverse cardiovascular reactions that have been reported include atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and a fivefold increased risk of myocardial infarction in the 60 minutes following cannabis use, which subsequently drops sharply to baseline levels.10 Investigations into the cardiovascular effects of cannabis are often complicated by concurrent use of other drugs such as tobacco or cocaine. Possible mechanisms of injury include alterations in coronary microcirculation or slowed coronary flow. In fact, one author found that cannabis users with a history of myocardial infarction had a risk of death 4.2 times higher than users with no history of myocardial infarction.11,12

In children, acute toxicity has been reported from a variety of exposures to cannabis and hashish, including a report of an increase in pediatric cannabis exposures following the changes in Colorado state laws.13 Most of these patients had altered mental status ranging from drowsiness to coma; one report describes a child who experienced a first-time seizure. These patients unfortunately often underwent extensive evaluations such as brain imaging and lumbar puncture, and mechanical ventilation to protect the airway. Earlier consideration of cannabis exposure in these patients might have limited unnecessary testing. Supportive care is usually all that is needed, and most of these patients fully recover.13–17

CHRONIC EFFECTS

Cannabinoids cause a variety of adverse effects, but the ultimate risk these changes pose to human health has been difficult to calculate. Long-term studies are confounded by possible inaccuracies of patient self-reporting of cannabis use, poor control of covariates, and disparate methodologies.

For more than a century, cannabis use has been reported to cause both acute psychotic symptoms and persistent psychotic disorders.18 But the strength of this relationship is modest. Cannabis is more likely a component cause that, in addition to other factors (eg, specific genetic polymorphisms), contributes to the risk of schizophrenia. Individuals with prodromal symptoms and those who have experienced discrete episodes of psychosis related to cannabis use should be discouraged from using cannabis and cannabinoids.19–21

Mounting evidence implicates chronic cannabis use as a cause of long-term medical problems including chronic bronchitis,22 elevated rates of myocardial infarction and dysrhythmias,11 bone loss,23 and cancers at eight different sites including the lung, head, and neck.24 In view of these chronic effects, healthcare providers should caution their patients about cannabis use, as we do about other drugs such as tobacco.

WITHDRAWAL SYNDROME RECOGNIZED

Until recently, neither clinicians nor users recognized a withdrawal syndrome associated with chronic use of cannabis, probably because this syndrome is not as severe as withdrawal from other controlled substances such as opioids or sedative-hypnotics. A number of studies, however, have reported subtle cannabis withdrawal symptoms that are similar to those associated with tobacco withdrawal.

As such, the fifth and latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)25 characterized withdrawal from cannabis use in 2013. The DSM-5 criteria require cessation of heavy or prolonged use of cannabis (ie, daily or almost daily over a period of at least a few months) and three or more of the following withdrawal symptoms:

- Irritability and anger

- Nervousness

- Sleep difficulty or insomnia

- Decreased appetite or weight loss

- Restlessness

- Depressed mood

- Physical symptoms causing discomfort.

Medical treatment of cannabis withdrawal has included a range of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and alpha-2-adrenergic agonists, all of which have limited success.26 Symptoms of cannabis withdrawal tend to be most intense soon after cessation and decline over the next few weeks.27

CANNABINOID HYPEREMESIS SYNDROME

First reported in 2004,28 cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is a recurrent disorder, the pathophysiology of which is poorly understood. It has three phases.

The first phase is a prodrome that may last months or years and is characterized by morning nausea, fear of vomiting, and abdominal discomfort. During this phase, the patient maintains normal eating patterns and may well increase his or her cannabis use due to its well-known antiemetic effects.

The second phase is the hyperemetic phase, characterized by intense, incapacitating emesis with episodes of vomiting throughout the day. These symptoms can be relieved only with frequent hot baths, a feature that distinguishes cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome from other vomiting syndromes. Hot-water bathing is reported to be a compulsive but learned behavior in which the patient learns that only hot water will provide relief. The extent of relief depends on the temperature of the water—the hotter, the better. Symptoms recur as the water cools.28 Patients often present to the emergency department repeatedly with recurrent symptoms and may remain misdiagnosed or subjected to repeated extensive evaluation including laboratory testing and imaging, which are usually not revealing. If the patient has not been accurately diagnosed, there may be reported weight loss of at least 5 kg.

The third phase, recovery, may take several months to complete, possibly because of the prolonged terminal elimination time of cannabinoids. Complete cessation of cannabis use, including synthetic cannabinoids, is usually necessary.29

Diagnostic criteria for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome have been suggested, based on a retrospective case series that included 98 patients.30 The most common features of these affected patients were:

- Severe cyclical vomiting, predominantly in the morning

- Resolution of symptoms with cessation of cannabis use

- Symptomatic relief with hot showers or baths

- Abdominal pain

- At least weekly use of cannabis.

Interestingly, long-term cannabis use has been cited as a critical identifying feature of these patients, with the duration of cannabis use ranging from 10 to 16 years.31,32 Other reports show greater variability in duration of cannabis use before the onset of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. In the large study noted above,30 32% of users reported their duration of cannabis use to be less than 1 year, rendering this criterion less useful.

How can cannabis both cause and prevent vomiting?

The body controls nausea and vomiting via complex circuitry in the brain and gut that involves many neurotransmitters (eg, dopamine, serotonin, substance P) that interact with receptors such as CB1, 5-HT1–4, alpha adrenergic receptors, and mu receptors. Interestingly, cannabis use has antiemetic properties mediated by CB1 with a still unclear additional role of CB2 receptors. Data point to the existence of an underlying antiemetic tone mediated by the endocannabinoid system.

Unfortunately, the mechanism by which cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome occurs is unknown and represents a paradoxical effect against the otherwise antiemetic effects of cannabis. Several theories have been proposed, including delayed gastric emptying, although only a third of patients demonstrated this on scintigraphy in one study.30 Other theories include disturbance of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, a buildup of highly lipophilic THC in the brain, and a down-regulation of cannabinoid receptors that results from chronic exposure.30 Given that this syndrome has been recognized only relatively recently, one author has suggested the cause may be recent horticultural developments.5

Treating cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is difficult

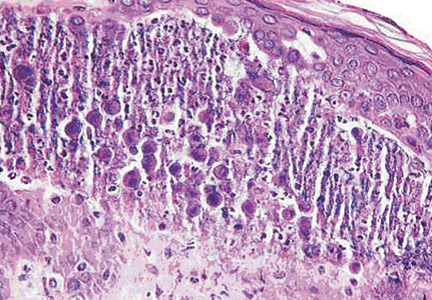

Treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is notoriously difficult, with many authors reporting resistance to the usual first-line antiemetic drugs. Generally, treatment should include hydration and acid-suppression therapy because endoscopic evaluation of several patients has revealed varying degrees of esophagitis and gastritis.29

Antiemetic therapy should target receptors known to mediate nausea and vomiting. In some cases, antiemetic drugs are more effective when used in combination. Agents include the serotonergic receptor antagonists ondansetron and granisetron, the dopamine antagonists prochlorperazine and metoclopramide, and even haloperidol.33,34 Benzodiazepines may be effective by causing sedation, anxiolysis, and depression of the vomiting center.34,35 Two antihistamines—dimenhydrinate and diphenhydramine—have antiemetic effects, perhaps by inhibiting acetylcholine.34

Aprepitant is a neurokinin-1 antagonist that inhibits the action of substance P. When combined with a corticosteroid and a serotonin antagonist, it relieves nausea and vomiting in chemotherapy patients.34,36

Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone are potent antiemetics thought to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis.34

Capsaicin cream applied to the abdomen has also been reported to relieve symptoms, possibly through an interaction between the TRPv1 receptor and the endocannabinoid system.37,38

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Cannabinoids are detectable in plasma and urine, with urine testing being more common.

Common laboratory methods include the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT) and radioimmunoassay. Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry is the most specific assay; it is used for confirmation and is the reference method.

EMIT is a qualitative urine test that detects 9-carboxy-THC as well as other THC metabolites. These urine tests detect all metabolites, and the result is reported as positive if the total concentration is greater than or equal to a prespecified threshold level, such as 20 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL. A positive test does not denote intoxication, nor does the test identify the source of THC (eg, cannabis, dronabinol, butane hash oil). EMIT does not detect nabilone. The National Institute on Drug Abuse guidelines for urine testing specify a test threshold concentration of 50 ng/mL for screening and 15 ng/mL for confirmation.

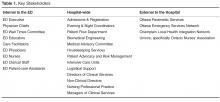

Many factors affect the detection of THC metabolites and their presence and duration in urine: dose, duration of use, route of exposure, hydration status, urine volume and concentration, and urine pH. THC metabolites have been detected in urine using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for up to 7 days after smoking one marijuana cigarette.7 Chronic users have also been reported to have positive urine EMIT tests for up to 46 days after cannabis cessation.39 Detection may be further complicated in chronic users: in one study, users produced both negative and positive specimens over 24 days, suggesting that diet and exercise may influence clearance.40 Also, many factors are known to produce false-positive and false-negative results for these immunoassays (Table 1).39,41

In the United States, penalties for driving under the influence of cannabis vary from state to state, and laws specify plasma testing for quantitative analysis. Some states use a threshold of 5 ng/mL in plasma to imply driving under the influence, whereas others use any detectable amount. Currently, there are no generally accepted guidelines for storage and testing of blood samples, despite the known instability of analytes.42

Saliva, hair, and sweat can also be used for cannabinoid testing. Saliva is easy to collect, can be tested for metabolites to rule out passive cannabis exposure, and can be positive for up to 1 day after exposure. Calculating a blood or plasma concentration from a saliva sample is not possible, however.

Hair testing can also rule out passive exposure, but THC binds very little to melanin, resulting in very low concentrations requiring sensitive tests, such as gas chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.

Only one device is commercially available for sweat testing; further work is needed to elucidate sweat excretion pharmacokinetics and the limitations of the collection devices.43

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT IS GENERALLY SUPPORTIVE

Historically, clinical toxicity from recreational cannabis use is rarely serious or severe and generally responds to supportive care. Reports of cannabis exposure to poison centers are one-tenth of those reported for ethanol exposures annually.44 Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal is not recommended, even for orally administered cannabis, since the risks outweigh the expected benefits. Agitation or anxiety may be treated with benzodiazepines as needed. There is no antidote for cannabis toxicity. The ever-increasing availability of high-concentration THC preparations may prompt more aggressive supportive measures in the future.

SYNTHETIC MARIJUANA ALTERNATIVES

Available since the early 2000s, herbal marijuana alternatives are legally sold as incense or potpourri and are often labeled “not for human consumption.” They are known by such brand names as K2 and Spice and contain blends of herbs adulterated with synthetic cannabinoid chemicals developed by researchers exploring the receptor-ligand binding of the endocannabinoid system.

Clinical effects, generally psychiatric, include paranoia, anxiety, agitation, delusions, and psychosis. There are also reports of patients who arrive with sympathomimetic toxicity, some of whom develop bradycardia and hypotension, and some who progress to acute renal failure, seizures, and death. Detection of these products is difficult as they do not react on EMIT testing for THC metabolites and require either gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.45–48

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2008 World Drug Report. www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2008/WDR_2008_eng_web.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). Public policy statement on medical marijuana. www.asam.org/docs/publicy-policy-statements/1medical-marijuana-4-10.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2002; 54:161–202.

- Sharkey KA, Darmani NA, Parker LA. Regulation of nausea and vomiting by cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 722:134–146.

- Iversen L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain 2003; 126:1252–1270.

- Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. J Anal Toxicol 1992; 16:276–282.

- Grotenhermen F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42:327–360.

- Mehmedic Z, Chandra S, Slade D, et al. Potency trends of Δ9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated cannabis preparations from 1993 to 2008. J Forensic Sci 2010; 55:1209–1217.

- Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation 2001; 103:2805–2809.

- Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. An exploratory prospective study of marijuana use and mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008; 155:465–470.

- Thomas G, Kloner RA, Rezkalla S. Adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular effects of marijuana inhalation: what cardiologists need to know. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:187–190.

- Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr 2013; 167:630–633.

- Carstairs SD, Fujinaka MK, Keeney GE, Ly BT. Prolonged coma in a child due to hashish ingestion with quantitation of THC metabolites in urine. J Emerg Med 2011; 41:e69–e71.

- Le Garrec S, Dauger S, Sachs P. Cannabis poisoning in children. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40:1394–1395.

- Ragab AR, Al-Mazroua MK. Passive cannabis smoking resulting in coma in a 16-month old infant. J Clin Case Rep 2012;2:237.

- Robinson K. Beyond resinable doubt? J Clin Forensic Med 2005;12:164–166.

- Burns JK. Pathways from cannabis to psychosis: a review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry 2013;4:128.

- Di Forti M, Sallis H, Allegri F, et al. Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull 2014; 40:1509–1517.

- Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2007; 370:319–328.

- Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D'Souza DC. Impact of cannabis use on the development of psychotic disorders. Curr Addict Rep 2014;1:115–128.

- Aldington S, Williams M, Nowitz M, et al. Effects of cannabis on pulmonary structure, function and symptoms. Thorax 2007; 62:1058–1063.

- George KL, Saltman LH, Stein GS, Lian JB, Zurier RB. Ajulemic acid, a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid acid, suppresses osteoclastogenesis in mononuclear precursor cells and induces apoptosis in mature osteoclast-like cells. J Cell Physiol 2008; 214:714–720.

- Reece AS. Chronic toxicology of cannabis. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009; 47:517–524.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Allsop DJ, Copeland J, Lintzeris N, et al. Nabiximols as an agonist replacement therapy during cannabis withdrawal: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71:281–291.

- Hesse M, Thylstrup B. Time-course of the DSM-5 cannabis withdrawal symptoms in poly-substance abusers. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13:258.

- Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, Twartz JC. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut 2004; 53:1566–1570.

- Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2011; 4:241–249.

- Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, Szostek JH. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: a case series of 98 patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87:114–119.

- Soriano-Co M, Batke M, Cappell MS. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: a report of eight cases in the United States. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55:3113–3119.

- Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, Jelley MJ. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J 2011; 104:659–664.

- Hickey JL, Witsil JC, Mycyk MB. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2013; 31:1003.e5–1003.e6.

- Perwitasari DA, Gelderblom H, Atthobari J, et al. Anti-emetic drugs in oncology: pharmacology and individualization by pharmacogenetics. Int J Clin Pharm 2011; 33:33–43.

- Cox B, Chhabra A, Adler M, Simmons J, Randlett D. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: case report of a paradoxical reaction with heavy marijuana use. Case Rep Med 2012; 2012:757696.

- Sakurai M, Mori T, Kato J, et al. Efficacy of aprepitant in preventing nausea and vomiting due to high-dose melphalan-based conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol 2014; 99:457–462.

- Lapoint J. Case series of patients treated for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome with capsaicin cream. Clin Tox 2014; 52:707. Abstract #53.

- Biary R, Oh A, Lapoint J, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Howland MA. Topical capsaicin cream used as a therapy for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Clin Tox 2014; 52:787. Abstract #232.

- Moeller KE, Lee KC, Kissack JC. Urine drug screening: practical guide for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83:66–76.

- Lowe RH, Abraham TT, Darwin WD, Herning R, Cadet JL, Huestis MA. Extended urinary delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol excretion in chronic cannabis users precludes use as a biomarker of new drug exposure. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009; 105:24–32.

- Paul BD, Jacobs A. Effects of oxidizing adulterants on detection of 11-nor-delta9-THC-9-carboxylic acid in urine. J Anal Toxicol 2002; 26:460–463.

- Schwope DM, Karschner EL, Gorelick DA, Huestis MA. Identification of recent cannabis use: whole-blood and plasma free and glucuronidated cannabinoid pharmacokinetics following controlled smoked cannabis administration. Clin Chem 2011; 57:1406-1414.

- Huestis MA, Smith ML. Cannabinoid pharmacokinetics and disposition in alternative matrices. In: Pertwee R, ed. Handbook of Cannabis. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2014:296–316.

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013; 51:949–1229.

- Rosenbaum CD, Carreiro SP, Babu KM. Here today, gone tomorrow…and back again? A review of herbal marijuana alternatives (K2, Spice), synthetic cathinones (bath salts), kratom, Salvia divinorum, methoxetamine, and piperazines. J Med Toxicol 2012; 8:15–32.

- Gurney SMR, Scott KS, Kacinko SL, Presley BC, Logan BK. Pharmacology, toxicology, and adverse effects of synthetic cannabinoid drugs. Forensic Sci Rev 2014; 26:53–78.

- McKeever RG, Vearrier D, Jacobs D, LaSala G, Okaneku J, Greenberg MI. K2-not the spice of life; synthetic cannabinoids and ST elevation myocardial infarction: a case report. J Med Toxicol 2015; 11:129–131.

- Schneir AB, Baumbacher T. Convulsions associated with the use of a synthetic cannabinoid product. J Med Toxicol 2012; 8:62–64.

Clinicians may be encountering more cannabis users than before, and may be encountering users with complications hitherto unseen. Several trends may explain this phenomenon: the legal status of cannabis is changing, cannabis today is more potent than in the past, and enthusiasts are conjuring new ways to enjoy this substance.

This article discusses the history, pharmacology, and potential complications of cannabis use.

A LONG AND TANGLED HISTORY

Cannabis is a broad term that refers to the cannabis plant and its preparations, such as marijuana and hashish, as well as to a family of more than 60 bioactive substances called cannabinoids. It is the most commonly used illegal drug in the world, with an estimated 160 million users. Each year, about 2.4 million people in the United States use it for the first time.1,2

Cannabis has been used throughout the world for recreational and spiritual purposes for nearly 5,000 years, beginning with the fabled Celestial Emperors of China. The tangled history of cannabis in America began in the 17th century, when farmers were required by law to grow it as a fiber crop. It later found its way into the US Pharmacopeia for a wide range of indications. During the long prelude to Prohibition in the latter half of the 19th century, the US government became increasingly suspicious of mind-altering substances and began restricting its prescription in 1934, culminating in its designation by the US Food and Drug Administration as a schedule I controlled substance in 1970.

Investigation into the potential medical uses for the different chemicals within cannabis is ongoing, as is debate over its changing legality and usefulness to society. The apparent cognitive dissonance surrounding the use and advocacy of medical marijuana is beyond the scope of this review,3 which will instead restrict itself to what is known of the cannabinoids and to the recreational use of cannabis.

THC IS THE PRINCIPAL PSYCHOACTIVE MOLECULE

Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), first isolated in 1964, was identified as the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis in 2002.4

Two G-protein–linked cannabinoid receptors cloned in the 1990s—CB1 and CB2—were found to be a part of a system of endocannabinoid receptors present throughout the body, from the brain to the immune system to the vas deferens.5 Both receptors inhibit cellular excitation by activating inwardly rectifying potassium channels. These receptors are mostly absent in the brainstem, which may explain why cannabis use rarely causes life-threatening autonomic dysfunction. Although the intoxicating effects of marijuana are mediated by CB1 receptors, the specific mechanisms underlying the cannabis “high” are unclear.6

CANNABINOIDS ARE LIPID-SOLUBLE

The rate of absorption of cannabinoids depends on the route of administration and the type of cannabis product used. When cannabis products are smoked, up to 35% of THC is available, and the average time to peak serum concentration is 8 minutes.7 The peak concentration depends on the dose.

On the other hand, when cannabis products (eg, nabilone, dronabinol) are ingested, absorption is unpredictable because THC is unstable in gastric acid and undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver, which reduces the drug’s bioavailability. Up to 20% of an ingested dose of THC is absorbed, and the time to peak serum concentration averages between 2 and 4 hours. Consequently, many users prefer to smoke cannabis as a means to control the desired effects.

Cannabinoids are lipid-soluble. They accumulate in fatty tissue in a biphasic pattern, initially moving into highly vascularized tissue such as the liver before accumulating in less well-vascularized tissue such as fat. They are then slowly released from fatty tissue as the fat turns over. THC itself has a volume of distribution of about 2.5 to 3.5 L/kg. It crosses the placenta and enters breast milk.8

THC is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, primarily by the enzymes CYP2C9 and CYP3A4. Its primary metabolite, 11-hydroxy-delta-9 THC, is also active, but subsequent metabolism produces many other inactive metabolites. THC is eliminated in feces and urine, and its half-life ranges from 2 to nearly 60 hours.8

A LITTLE ABOUT PLANTS AND STREET NAMES

The plant from which THC and nearly a hundred other chemicals, including cannabinoids, are derived has been called many things over the years:

Hemp is a tall fibrous plant grown for rope and fabric that was used as legal tender in early America. In the mid-19th century, there were over 16 million acres of hemp plantations. Hemp contains very low THC concentrations.

Cannabis is an annual flowering herb that is predominantly diecious (ie, there are male and female plants). After a centuries-long debate among taxonomists, the two principal species are considered to be C sativa and C indica, although today many cannabis cultivars are grown by a great number of breeding enthusiasts.

Concentrations of THC vary widely among cannabis cultivars, ranging historically from around 5% to today’s highly selectively bred species containing more than 30%. Concentrations in seized cannabis have been measured as high as 37%, although the average is around 11%.9 This concentration is defined by the percent of THC per dried mass of plant material tested, usually via gas chromatography.

Hashish is a solid or resinous preparation of the trichomes, or glandular hairs, that grow on the cannabis plant, chiefly on its flowers. Various methods to separate the trichomes from the rest of the plant result in a powder called kief that is then compressed into blocks or bricks. THC concentrations as high as 66% have been measured in nondomestic sources of hashish.9

Hash oil is a further purification, produced by using solvents to dissolve the resin and by filtering out remaining plant material. Evaporating the solvent produces hash oil, sometimes called butane hash oil or honey oil. This process has recently led to an increasing number of home explosions, as people attempt to make the product themselves but do not take suitable precautions when using flammable solvents such as butane. THC concentrations as high as 81% have been measured in nondomestic sources of hash oil.9

Other names for hash oil are dab, wax, and budder. Cannabis enthusiasts refer to the use of hash oil as dabbing, which involves heating a small amount (dab) of the product using a variety of paraphernalia and inhaling the vapor.

IT’S ALL ABOUT GETTING HIGH

For recreational users, the experience has always been about being intoxicated—getting high. The psychological effects range broadly from positive to negative and vary both within and between users, depending on the dose and route of administration. Additional factors that influence the psychological effects include the social and physical settings of drug use and even the user’s expectations. One user’s high is another user’s acute toxic effect.

Although subjective reports of the cannabis experience vary greatly, it typically begins with a feeling of dizziness or lightheadedness followed by a relaxed calm and a feeling of being somewhat “disconnected.” There is a quickening of the sense of humor, described by some as a fatuous euphoria; often there is silly giggling. Awareness of the senses and of music may be increased. Appetite increases, and time seems to pass quickly. Eventually, the user becomes drowsy and experiences decreased attention and difficulty maintaining a coherent conversation. Slowed reaction time and decreased psychomotor activity may also occur. The user may drift into daydreams and eventually fall asleep.

Common negative acute effects of getting high can include mild to severe anxiety and feeling tense or agitated. Clumsiness, headache, and confusion are also possible. Lingering effects the following day may include dry mouth, dry eyes, fatigue, slowed thinking, and slowed recall.6

ACUTE PHYSICAL EFFECTS

Acute physical effects of cannabis use include a rapid onset of increased airway conductance, decreased intraocular pressure, and conjunctival injection. A single cannabis cigarette can also induce cardiovascular effects including a dose-dependent increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Chronic users, however, can experience a decreased heart rate, lower blood pressure, and postural hypotension.

In a personal communication, colleagues in Colorado—where recreational use of cannabis was legalized in 2012—described a sharp increase (from virtually none) in the number of adults presenting to the emergency department with cannabis intoxication since 2012. Their patients experienced palpitations, light-headedness, and severe ataxia lasting as long as 12 hours, possibly reflecting the greater potency of current cannabis products. Most of these patients required only supportive care.

Other acute adverse cardiovascular reactions that have been reported include atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and a fivefold increased risk of myocardial infarction in the 60 minutes following cannabis use, which subsequently drops sharply to baseline levels.10 Investigations into the cardiovascular effects of cannabis are often complicated by concurrent use of other drugs such as tobacco or cocaine. Possible mechanisms of injury include alterations in coronary microcirculation or slowed coronary flow. In fact, one author found that cannabis users with a history of myocardial infarction had a risk of death 4.2 times higher than users with no history of myocardial infarction.11,12

In children, acute toxicity has been reported from a variety of exposures to cannabis and hashish, including a report of an increase in pediatric cannabis exposures following the changes in Colorado state laws.13 Most of these patients had altered mental status ranging from drowsiness to coma; one report describes a child who experienced a first-time seizure. These patients unfortunately often underwent extensive evaluations such as brain imaging and lumbar puncture, and mechanical ventilation to protect the airway. Earlier consideration of cannabis exposure in these patients might have limited unnecessary testing. Supportive care is usually all that is needed, and most of these patients fully recover.13–17

CHRONIC EFFECTS

Cannabinoids cause a variety of adverse effects, but the ultimate risk these changes pose to human health has been difficult to calculate. Long-term studies are confounded by possible inaccuracies of patient self-reporting of cannabis use, poor control of covariates, and disparate methodologies.

For more than a century, cannabis use has been reported to cause both acute psychotic symptoms and persistent psychotic disorders.18 But the strength of this relationship is modest. Cannabis is more likely a component cause that, in addition to other factors (eg, specific genetic polymorphisms), contributes to the risk of schizophrenia. Individuals with prodromal symptoms and those who have experienced discrete episodes of psychosis related to cannabis use should be discouraged from using cannabis and cannabinoids.19–21

Mounting evidence implicates chronic cannabis use as a cause of long-term medical problems including chronic bronchitis,22 elevated rates of myocardial infarction and dysrhythmias,11 bone loss,23 and cancers at eight different sites including the lung, head, and neck.24 In view of these chronic effects, healthcare providers should caution their patients about cannabis use, as we do about other drugs such as tobacco.

WITHDRAWAL SYNDROME RECOGNIZED

Until recently, neither clinicians nor users recognized a withdrawal syndrome associated with chronic use of cannabis, probably because this syndrome is not as severe as withdrawal from other controlled substances such as opioids or sedative-hypnotics. A number of studies, however, have reported subtle cannabis withdrawal symptoms that are similar to those associated with tobacco withdrawal.

As such, the fifth and latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)25 characterized withdrawal from cannabis use in 2013. The DSM-5 criteria require cessation of heavy or prolonged use of cannabis (ie, daily or almost daily over a period of at least a few months) and three or more of the following withdrawal symptoms:

- Irritability and anger

- Nervousness

- Sleep difficulty or insomnia

- Decreased appetite or weight loss

- Restlessness

- Depressed mood

- Physical symptoms causing discomfort.

Medical treatment of cannabis withdrawal has included a range of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and alpha-2-adrenergic agonists, all of which have limited success.26 Symptoms of cannabis withdrawal tend to be most intense soon after cessation and decline over the next few weeks.27

CANNABINOID HYPEREMESIS SYNDROME

First reported in 2004,28 cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is a recurrent disorder, the pathophysiology of which is poorly understood. It has three phases.

The first phase is a prodrome that may last months or years and is characterized by morning nausea, fear of vomiting, and abdominal discomfort. During this phase, the patient maintains normal eating patterns and may well increase his or her cannabis use due to its well-known antiemetic effects.

The second phase is the hyperemetic phase, characterized by intense, incapacitating emesis with episodes of vomiting throughout the day. These symptoms can be relieved only with frequent hot baths, a feature that distinguishes cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome from other vomiting syndromes. Hot-water bathing is reported to be a compulsive but learned behavior in which the patient learns that only hot water will provide relief. The extent of relief depends on the temperature of the water—the hotter, the better. Symptoms recur as the water cools.28 Patients often present to the emergency department repeatedly with recurrent symptoms and may remain misdiagnosed or subjected to repeated extensive evaluation including laboratory testing and imaging, which are usually not revealing. If the patient has not been accurately diagnosed, there may be reported weight loss of at least 5 kg.

The third phase, recovery, may take several months to complete, possibly because of the prolonged terminal elimination time of cannabinoids. Complete cessation of cannabis use, including synthetic cannabinoids, is usually necessary.29

Diagnostic criteria for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome have been suggested, based on a retrospective case series that included 98 patients.30 The most common features of these affected patients were:

- Severe cyclical vomiting, predominantly in the morning

- Resolution of symptoms with cessation of cannabis use

- Symptomatic relief with hot showers or baths

- Abdominal pain

- At least weekly use of cannabis.

Interestingly, long-term cannabis use has been cited as a critical identifying feature of these patients, with the duration of cannabis use ranging from 10 to 16 years.31,32 Other reports show greater variability in duration of cannabis use before the onset of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. In the large study noted above,30 32% of users reported their duration of cannabis use to be less than 1 year, rendering this criterion less useful.

How can cannabis both cause and prevent vomiting?

The body controls nausea and vomiting via complex circuitry in the brain and gut that involves many neurotransmitters (eg, dopamine, serotonin, substance P) that interact with receptors such as CB1, 5-HT1–4, alpha adrenergic receptors, and mu receptors. Interestingly, cannabis use has antiemetic properties mediated by CB1 with a still unclear additional role of CB2 receptors. Data point to the existence of an underlying antiemetic tone mediated by the endocannabinoid system.

Unfortunately, the mechanism by which cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome occurs is unknown and represents a paradoxical effect against the otherwise antiemetic effects of cannabis. Several theories have been proposed, including delayed gastric emptying, although only a third of patients demonstrated this on scintigraphy in one study.30 Other theories include disturbance of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, a buildup of highly lipophilic THC in the brain, and a down-regulation of cannabinoid receptors that results from chronic exposure.30 Given that this syndrome has been recognized only relatively recently, one author has suggested the cause may be recent horticultural developments.5

Treating cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is difficult

Treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is notoriously difficult, with many authors reporting resistance to the usual first-line antiemetic drugs. Generally, treatment should include hydration and acid-suppression therapy because endoscopic evaluation of several patients has revealed varying degrees of esophagitis and gastritis.29

Antiemetic therapy should target receptors known to mediate nausea and vomiting. In some cases, antiemetic drugs are more effective when used in combination. Agents include the serotonergic receptor antagonists ondansetron and granisetron, the dopamine antagonists prochlorperazine and metoclopramide, and even haloperidol.33,34 Benzodiazepines may be effective by causing sedation, anxiolysis, and depression of the vomiting center.34,35 Two antihistamines—dimenhydrinate and diphenhydramine—have antiemetic effects, perhaps by inhibiting acetylcholine.34

Aprepitant is a neurokinin-1 antagonist that inhibits the action of substance P. When combined with a corticosteroid and a serotonin antagonist, it relieves nausea and vomiting in chemotherapy patients.34,36

Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone are potent antiemetics thought to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis.34

Capsaicin cream applied to the abdomen has also been reported to relieve symptoms, possibly through an interaction between the TRPv1 receptor and the endocannabinoid system.37,38

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Cannabinoids are detectable in plasma and urine, with urine testing being more common.

Common laboratory methods include the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT) and radioimmunoassay. Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry is the most specific assay; it is used for confirmation and is the reference method.

EMIT is a qualitative urine test that detects 9-carboxy-THC as well as other THC metabolites. These urine tests detect all metabolites, and the result is reported as positive if the total concentration is greater than or equal to a prespecified threshold level, such as 20 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL. A positive test does not denote intoxication, nor does the test identify the source of THC (eg, cannabis, dronabinol, butane hash oil). EMIT does not detect nabilone. The National Institute on Drug Abuse guidelines for urine testing specify a test threshold concentration of 50 ng/mL for screening and 15 ng/mL for confirmation.

Many factors affect the detection of THC metabolites and their presence and duration in urine: dose, duration of use, route of exposure, hydration status, urine volume and concentration, and urine pH. THC metabolites have been detected in urine using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for up to 7 days after smoking one marijuana cigarette.7 Chronic users have also been reported to have positive urine EMIT tests for up to 46 days after cannabis cessation.39 Detection may be further complicated in chronic users: in one study, users produced both negative and positive specimens over 24 days, suggesting that diet and exercise may influence clearance.40 Also, many factors are known to produce false-positive and false-negative results for these immunoassays (Table 1).39,41

In the United States, penalties for driving under the influence of cannabis vary from state to state, and laws specify plasma testing for quantitative analysis. Some states use a threshold of 5 ng/mL in plasma to imply driving under the influence, whereas others use any detectable amount. Currently, there are no generally accepted guidelines for storage and testing of blood samples, despite the known instability of analytes.42

Saliva, hair, and sweat can also be used for cannabinoid testing. Saliva is easy to collect, can be tested for metabolites to rule out passive cannabis exposure, and can be positive for up to 1 day after exposure. Calculating a blood or plasma concentration from a saliva sample is not possible, however.

Hair testing can also rule out passive exposure, but THC binds very little to melanin, resulting in very low concentrations requiring sensitive tests, such as gas chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.

Only one device is commercially available for sweat testing; further work is needed to elucidate sweat excretion pharmacokinetics and the limitations of the collection devices.43

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT IS GENERALLY SUPPORTIVE

Historically, clinical toxicity from recreational cannabis use is rarely serious or severe and generally responds to supportive care. Reports of cannabis exposure to poison centers are one-tenth of those reported for ethanol exposures annually.44 Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal is not recommended, even for orally administered cannabis, since the risks outweigh the expected benefits. Agitation or anxiety may be treated with benzodiazepines as needed. There is no antidote for cannabis toxicity. The ever-increasing availability of high-concentration THC preparations may prompt more aggressive supportive measures in the future.

SYNTHETIC MARIJUANA ALTERNATIVES

Available since the early 2000s, herbal marijuana alternatives are legally sold as incense or potpourri and are often labeled “not for human consumption.” They are known by such brand names as K2 and Spice and contain blends of herbs adulterated with synthetic cannabinoid chemicals developed by researchers exploring the receptor-ligand binding of the endocannabinoid system.

Clinical effects, generally psychiatric, include paranoia, anxiety, agitation, delusions, and psychosis. There are also reports of patients who arrive with sympathomimetic toxicity, some of whom develop bradycardia and hypotension, and some who progress to acute renal failure, seizures, and death. Detection of these products is difficult as they do not react on EMIT testing for THC metabolites and require either gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.45–48

Clinicians may be encountering more cannabis users than before, and may be encountering users with complications hitherto unseen. Several trends may explain this phenomenon: the legal status of cannabis is changing, cannabis today is more potent than in the past, and enthusiasts are conjuring new ways to enjoy this substance.

This article discusses the history, pharmacology, and potential complications of cannabis use.

A LONG AND TANGLED HISTORY

Cannabis is a broad term that refers to the cannabis plant and its preparations, such as marijuana and hashish, as well as to a family of more than 60 bioactive substances called cannabinoids. It is the most commonly used illegal drug in the world, with an estimated 160 million users. Each year, about 2.4 million people in the United States use it for the first time.1,2

Cannabis has been used throughout the world for recreational and spiritual purposes for nearly 5,000 years, beginning with the fabled Celestial Emperors of China. The tangled history of cannabis in America began in the 17th century, when farmers were required by law to grow it as a fiber crop. It later found its way into the US Pharmacopeia for a wide range of indications. During the long prelude to Prohibition in the latter half of the 19th century, the US government became increasingly suspicious of mind-altering substances and began restricting its prescription in 1934, culminating in its designation by the US Food and Drug Administration as a schedule I controlled substance in 1970.

Investigation into the potential medical uses for the different chemicals within cannabis is ongoing, as is debate over its changing legality and usefulness to society. The apparent cognitive dissonance surrounding the use and advocacy of medical marijuana is beyond the scope of this review,3 which will instead restrict itself to what is known of the cannabinoids and to the recreational use of cannabis.

THC IS THE PRINCIPAL PSYCHOACTIVE MOLECULE

Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), first isolated in 1964, was identified as the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis in 2002.4

Two G-protein–linked cannabinoid receptors cloned in the 1990s—CB1 and CB2—were found to be a part of a system of endocannabinoid receptors present throughout the body, from the brain to the immune system to the vas deferens.5 Both receptors inhibit cellular excitation by activating inwardly rectifying potassium channels. These receptors are mostly absent in the brainstem, which may explain why cannabis use rarely causes life-threatening autonomic dysfunction. Although the intoxicating effects of marijuana are mediated by CB1 receptors, the specific mechanisms underlying the cannabis “high” are unclear.6

CANNABINOIDS ARE LIPID-SOLUBLE

The rate of absorption of cannabinoids depends on the route of administration and the type of cannabis product used. When cannabis products are smoked, up to 35% of THC is available, and the average time to peak serum concentration is 8 minutes.7 The peak concentration depends on the dose.

On the other hand, when cannabis products (eg, nabilone, dronabinol) are ingested, absorption is unpredictable because THC is unstable in gastric acid and undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver, which reduces the drug’s bioavailability. Up to 20% of an ingested dose of THC is absorbed, and the time to peak serum concentration averages between 2 and 4 hours. Consequently, many users prefer to smoke cannabis as a means to control the desired effects.

Cannabinoids are lipid-soluble. They accumulate in fatty tissue in a biphasic pattern, initially moving into highly vascularized tissue such as the liver before accumulating in less well-vascularized tissue such as fat. They are then slowly released from fatty tissue as the fat turns over. THC itself has a volume of distribution of about 2.5 to 3.5 L/kg. It crosses the placenta and enters breast milk.8

THC is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, primarily by the enzymes CYP2C9 and CYP3A4. Its primary metabolite, 11-hydroxy-delta-9 THC, is also active, but subsequent metabolism produces many other inactive metabolites. THC is eliminated in feces and urine, and its half-life ranges from 2 to nearly 60 hours.8

A LITTLE ABOUT PLANTS AND STREET NAMES

The plant from which THC and nearly a hundred other chemicals, including cannabinoids, are derived has been called many things over the years:

Hemp is a tall fibrous plant grown for rope and fabric that was used as legal tender in early America. In the mid-19th century, there were over 16 million acres of hemp plantations. Hemp contains very low THC concentrations.

Cannabis is an annual flowering herb that is predominantly diecious (ie, there are male and female plants). After a centuries-long debate among taxonomists, the two principal species are considered to be C sativa and C indica, although today many cannabis cultivars are grown by a great number of breeding enthusiasts.

Concentrations of THC vary widely among cannabis cultivars, ranging historically from around 5% to today’s highly selectively bred species containing more than 30%. Concentrations in seized cannabis have been measured as high as 37%, although the average is around 11%.9 This concentration is defined by the percent of THC per dried mass of plant material tested, usually via gas chromatography.

Hashish is a solid or resinous preparation of the trichomes, or glandular hairs, that grow on the cannabis plant, chiefly on its flowers. Various methods to separate the trichomes from the rest of the plant result in a powder called kief that is then compressed into blocks or bricks. THC concentrations as high as 66% have been measured in nondomestic sources of hashish.9

Hash oil is a further purification, produced by using solvents to dissolve the resin and by filtering out remaining plant material. Evaporating the solvent produces hash oil, sometimes called butane hash oil or honey oil. This process has recently led to an increasing number of home explosions, as people attempt to make the product themselves but do not take suitable precautions when using flammable solvents such as butane. THC concentrations as high as 81% have been measured in nondomestic sources of hash oil.9

Other names for hash oil are dab, wax, and budder. Cannabis enthusiasts refer to the use of hash oil as dabbing, which involves heating a small amount (dab) of the product using a variety of paraphernalia and inhaling the vapor.

IT’S ALL ABOUT GETTING HIGH

For recreational users, the experience has always been about being intoxicated—getting high. The psychological effects range broadly from positive to negative and vary both within and between users, depending on the dose and route of administration. Additional factors that influence the psychological effects include the social and physical settings of drug use and even the user’s expectations. One user’s high is another user’s acute toxic effect.

Although subjective reports of the cannabis experience vary greatly, it typically begins with a feeling of dizziness or lightheadedness followed by a relaxed calm and a feeling of being somewhat “disconnected.” There is a quickening of the sense of humor, described by some as a fatuous euphoria; often there is silly giggling. Awareness of the senses and of music may be increased. Appetite increases, and time seems to pass quickly. Eventually, the user becomes drowsy and experiences decreased attention and difficulty maintaining a coherent conversation. Slowed reaction time and decreased psychomotor activity may also occur. The user may drift into daydreams and eventually fall asleep.

Common negative acute effects of getting high can include mild to severe anxiety and feeling tense or agitated. Clumsiness, headache, and confusion are also possible. Lingering effects the following day may include dry mouth, dry eyes, fatigue, slowed thinking, and slowed recall.6

ACUTE PHYSICAL EFFECTS

Acute physical effects of cannabis use include a rapid onset of increased airway conductance, decreased intraocular pressure, and conjunctival injection. A single cannabis cigarette can also induce cardiovascular effects including a dose-dependent increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Chronic users, however, can experience a decreased heart rate, lower blood pressure, and postural hypotension.

In a personal communication, colleagues in Colorado—where recreational use of cannabis was legalized in 2012—described a sharp increase (from virtually none) in the number of adults presenting to the emergency department with cannabis intoxication since 2012. Their patients experienced palpitations, light-headedness, and severe ataxia lasting as long as 12 hours, possibly reflecting the greater potency of current cannabis products. Most of these patients required only supportive care.

Other acute adverse cardiovascular reactions that have been reported include atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, and a fivefold increased risk of myocardial infarction in the 60 minutes following cannabis use, which subsequently drops sharply to baseline levels.10 Investigations into the cardiovascular effects of cannabis are often complicated by concurrent use of other drugs such as tobacco or cocaine. Possible mechanisms of injury include alterations in coronary microcirculation or slowed coronary flow. In fact, one author found that cannabis users with a history of myocardial infarction had a risk of death 4.2 times higher than users with no history of myocardial infarction.11,12

In children, acute toxicity has been reported from a variety of exposures to cannabis and hashish, including a report of an increase in pediatric cannabis exposures following the changes in Colorado state laws.13 Most of these patients had altered mental status ranging from drowsiness to coma; one report describes a child who experienced a first-time seizure. These patients unfortunately often underwent extensive evaluations such as brain imaging and lumbar puncture, and mechanical ventilation to protect the airway. Earlier consideration of cannabis exposure in these patients might have limited unnecessary testing. Supportive care is usually all that is needed, and most of these patients fully recover.13–17

CHRONIC EFFECTS

Cannabinoids cause a variety of adverse effects, but the ultimate risk these changes pose to human health has been difficult to calculate. Long-term studies are confounded by possible inaccuracies of patient self-reporting of cannabis use, poor control of covariates, and disparate methodologies.

For more than a century, cannabis use has been reported to cause both acute psychotic symptoms and persistent psychotic disorders.18 But the strength of this relationship is modest. Cannabis is more likely a component cause that, in addition to other factors (eg, specific genetic polymorphisms), contributes to the risk of schizophrenia. Individuals with prodromal symptoms and those who have experienced discrete episodes of psychosis related to cannabis use should be discouraged from using cannabis and cannabinoids.19–21

Mounting evidence implicates chronic cannabis use as a cause of long-term medical problems including chronic bronchitis,22 elevated rates of myocardial infarction and dysrhythmias,11 bone loss,23 and cancers at eight different sites including the lung, head, and neck.24 In view of these chronic effects, healthcare providers should caution their patients about cannabis use, as we do about other drugs such as tobacco.

WITHDRAWAL SYNDROME RECOGNIZED

Until recently, neither clinicians nor users recognized a withdrawal syndrome associated with chronic use of cannabis, probably because this syndrome is not as severe as withdrawal from other controlled substances such as opioids or sedative-hypnotics. A number of studies, however, have reported subtle cannabis withdrawal symptoms that are similar to those associated with tobacco withdrawal.

As such, the fifth and latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)25 characterized withdrawal from cannabis use in 2013. The DSM-5 criteria require cessation of heavy or prolonged use of cannabis (ie, daily or almost daily over a period of at least a few months) and three or more of the following withdrawal symptoms:

- Irritability and anger

- Nervousness

- Sleep difficulty or insomnia

- Decreased appetite or weight loss

- Restlessness

- Depressed mood

- Physical symptoms causing discomfort.

Medical treatment of cannabis withdrawal has included a range of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and alpha-2-adrenergic agonists, all of which have limited success.26 Symptoms of cannabis withdrawal tend to be most intense soon after cessation and decline over the next few weeks.27

CANNABINOID HYPEREMESIS SYNDROME

First reported in 2004,28 cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is a recurrent disorder, the pathophysiology of which is poorly understood. It has three phases.

The first phase is a prodrome that may last months or years and is characterized by morning nausea, fear of vomiting, and abdominal discomfort. During this phase, the patient maintains normal eating patterns and may well increase his or her cannabis use due to its well-known antiemetic effects.

The second phase is the hyperemetic phase, characterized by intense, incapacitating emesis with episodes of vomiting throughout the day. These symptoms can be relieved only with frequent hot baths, a feature that distinguishes cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome from other vomiting syndromes. Hot-water bathing is reported to be a compulsive but learned behavior in which the patient learns that only hot water will provide relief. The extent of relief depends on the temperature of the water—the hotter, the better. Symptoms recur as the water cools.28 Patients often present to the emergency department repeatedly with recurrent symptoms and may remain misdiagnosed or subjected to repeated extensive evaluation including laboratory testing and imaging, which are usually not revealing. If the patient has not been accurately diagnosed, there may be reported weight loss of at least 5 kg.

The third phase, recovery, may take several months to complete, possibly because of the prolonged terminal elimination time of cannabinoids. Complete cessation of cannabis use, including synthetic cannabinoids, is usually necessary.29

Diagnostic criteria for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome have been suggested, based on a retrospective case series that included 98 patients.30 The most common features of these affected patients were:

- Severe cyclical vomiting, predominantly in the morning

- Resolution of symptoms with cessation of cannabis use

- Symptomatic relief with hot showers or baths

- Abdominal pain

- At least weekly use of cannabis.

Interestingly, long-term cannabis use has been cited as a critical identifying feature of these patients, with the duration of cannabis use ranging from 10 to 16 years.31,32 Other reports show greater variability in duration of cannabis use before the onset of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. In the large study noted above,30 32% of users reported their duration of cannabis use to be less than 1 year, rendering this criterion less useful.

How can cannabis both cause and prevent vomiting?

The body controls nausea and vomiting via complex circuitry in the brain and gut that involves many neurotransmitters (eg, dopamine, serotonin, substance P) that interact with receptors such as CB1, 5-HT1–4, alpha adrenergic receptors, and mu receptors. Interestingly, cannabis use has antiemetic properties mediated by CB1 with a still unclear additional role of CB2 receptors. Data point to the existence of an underlying antiemetic tone mediated by the endocannabinoid system.

Unfortunately, the mechanism by which cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome occurs is unknown and represents a paradoxical effect against the otherwise antiemetic effects of cannabis. Several theories have been proposed, including delayed gastric emptying, although only a third of patients demonstrated this on scintigraphy in one study.30 Other theories include disturbance of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, a buildup of highly lipophilic THC in the brain, and a down-regulation of cannabinoid receptors that results from chronic exposure.30 Given that this syndrome has been recognized only relatively recently, one author has suggested the cause may be recent horticultural developments.5

Treating cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is difficult

Treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is notoriously difficult, with many authors reporting resistance to the usual first-line antiemetic drugs. Generally, treatment should include hydration and acid-suppression therapy because endoscopic evaluation of several patients has revealed varying degrees of esophagitis and gastritis.29

Antiemetic therapy should target receptors known to mediate nausea and vomiting. In some cases, antiemetic drugs are more effective when used in combination. Agents include the serotonergic receptor antagonists ondansetron and granisetron, the dopamine antagonists prochlorperazine and metoclopramide, and even haloperidol.33,34 Benzodiazepines may be effective by causing sedation, anxiolysis, and depression of the vomiting center.34,35 Two antihistamines—dimenhydrinate and diphenhydramine—have antiemetic effects, perhaps by inhibiting acetylcholine.34

Aprepitant is a neurokinin-1 antagonist that inhibits the action of substance P. When combined with a corticosteroid and a serotonin antagonist, it relieves nausea and vomiting in chemotherapy patients.34,36

Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone are potent antiemetics thought to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis.34

Capsaicin cream applied to the abdomen has also been reported to relieve symptoms, possibly through an interaction between the TRPv1 receptor and the endocannabinoid system.37,38

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Cannabinoids are detectable in plasma and urine, with urine testing being more common.

Common laboratory methods include the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT) and radioimmunoassay. Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry is the most specific assay; it is used for confirmation and is the reference method.

EMIT is a qualitative urine test that detects 9-carboxy-THC as well as other THC metabolites. These urine tests detect all metabolites, and the result is reported as positive if the total concentration is greater than or equal to a prespecified threshold level, such as 20 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL. A positive test does not denote intoxication, nor does the test identify the source of THC (eg, cannabis, dronabinol, butane hash oil). EMIT does not detect nabilone. The National Institute on Drug Abuse guidelines for urine testing specify a test threshold concentration of 50 ng/mL for screening and 15 ng/mL for confirmation.

Many factors affect the detection of THC metabolites and their presence and duration in urine: dose, duration of use, route of exposure, hydration status, urine volume and concentration, and urine pH. THC metabolites have been detected in urine using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for up to 7 days after smoking one marijuana cigarette.7 Chronic users have also been reported to have positive urine EMIT tests for up to 46 days after cannabis cessation.39 Detection may be further complicated in chronic users: in one study, users produced both negative and positive specimens over 24 days, suggesting that diet and exercise may influence clearance.40 Also, many factors are known to produce false-positive and false-negative results for these immunoassays (Table 1).39,41

In the United States, penalties for driving under the influence of cannabis vary from state to state, and laws specify plasma testing for quantitative analysis. Some states use a threshold of 5 ng/mL in plasma to imply driving under the influence, whereas others use any detectable amount. Currently, there are no generally accepted guidelines for storage and testing of blood samples, despite the known instability of analytes.42

Saliva, hair, and sweat can also be used for cannabinoid testing. Saliva is easy to collect, can be tested for metabolites to rule out passive cannabis exposure, and can be positive for up to 1 day after exposure. Calculating a blood or plasma concentration from a saliva sample is not possible, however.

Hair testing can also rule out passive exposure, but THC binds very little to melanin, resulting in very low concentrations requiring sensitive tests, such as gas chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.

Only one device is commercially available for sweat testing; further work is needed to elucidate sweat excretion pharmacokinetics and the limitations of the collection devices.43

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT IS GENERALLY SUPPORTIVE

Historically, clinical toxicity from recreational cannabis use is rarely serious or severe and generally responds to supportive care. Reports of cannabis exposure to poison centers are one-tenth of those reported for ethanol exposures annually.44 Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal is not recommended, even for orally administered cannabis, since the risks outweigh the expected benefits. Agitation or anxiety may be treated with benzodiazepines as needed. There is no antidote for cannabis toxicity. The ever-increasing availability of high-concentration THC preparations may prompt more aggressive supportive measures in the future.

SYNTHETIC MARIJUANA ALTERNATIVES

Available since the early 2000s, herbal marijuana alternatives are legally sold as incense or potpourri and are often labeled “not for human consumption.” They are known by such brand names as K2 and Spice and contain blends of herbs adulterated with synthetic cannabinoid chemicals developed by researchers exploring the receptor-ligand binding of the endocannabinoid system.

Clinical effects, generally psychiatric, include paranoia, anxiety, agitation, delusions, and psychosis. There are also reports of patients who arrive with sympathomimetic toxicity, some of whom develop bradycardia and hypotension, and some who progress to acute renal failure, seizures, and death. Detection of these products is difficult as they do not react on EMIT testing for THC metabolites and require either gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.45–48

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2008 World Drug Report. www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2008/WDR_2008_eng_web.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). Public policy statement on medical marijuana. www.asam.org/docs/publicy-policy-statements/1medical-marijuana-4-10.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2002; 54:161–202.

- Sharkey KA, Darmani NA, Parker LA. Regulation of nausea and vomiting by cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 722:134–146.

- Iversen L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain 2003; 126:1252–1270.

- Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. J Anal Toxicol 1992; 16:276–282.

- Grotenhermen F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42:327–360.

- Mehmedic Z, Chandra S, Slade D, et al. Potency trends of Δ9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated cannabis preparations from 1993 to 2008. J Forensic Sci 2010; 55:1209–1217.

- Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation 2001; 103:2805–2809.

- Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. An exploratory prospective study of marijuana use and mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008; 155:465–470.

- Thomas G, Kloner RA, Rezkalla S. Adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular effects of marijuana inhalation: what cardiologists need to know. Am J Cardiol 2014; 113:187–190.

- Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr 2013; 167:630–633.

- Carstairs SD, Fujinaka MK, Keeney GE, Ly BT. Prolonged coma in a child due to hashish ingestion with quantitation of THC metabolites in urine. J Emerg Med 2011; 41:e69–e71.

- Le Garrec S, Dauger S, Sachs P. Cannabis poisoning in children. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40:1394–1395.

- Ragab AR, Al-Mazroua MK. Passive cannabis smoking resulting in coma in a 16-month old infant. J Clin Case Rep 2012;2:237.

- Robinson K. Beyond resinable doubt? J Clin Forensic Med 2005;12:164–166.

- Burns JK. Pathways from cannabis to psychosis: a review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry 2013;4:128.