User login

Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis in Acutely Ill Veterans With Respiratory Disease

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is an important public health concern. Deep venous thrombosis is estimated to affect 10% to 20% of medical (nonsurgical) patients, 15% to 40% of stroke patients, and 10% to 80% of critical care patients who are not prophylaxed.1 Venous thromboembolism is associated with significant resource utilization, long-term sequelae, recurrent events, and sudden death.2

The current guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians recommend use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis as the preferred strategy for nonsurgical (or medical) patients (IB, formerly IA, recommendation) and for critically ill patients (2C recommendation) at low risk for bleeding.1,3 Mechanical (or nonpharmacologic) thromboprophylaxis (eg, intermittent pneumatic compression) is an alternative for those at increased risk for bleeding (2C recommendation).3 Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in high-risk patients, similar to those studied in randomized controlled clinical trials, reduces the occurrence of symptomatic DVT by 34 events per 1,000 patients treated.3 However, data are conflicting regarding mortality benefit.4,5

Related: Trends in Venous Thromboembolism

The Joint Commission adopted any thromboprophylaxis (measure includes pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic strategies) as a core discretionary measure in the ORYX (National Quality Hospital Measures) program. The ORYX measurements are intended to support Joint Commission-accredited organizations in institutional quality improvement efforts. The thromboprophylaxis core measure became effective May 2009 and remains as an option for hospitals to meet the 4 core measure set accreditation requirement. A top-performing hospital should provide this measure to applicable patients ≥ 95% of the time, according to the Joint Commission.6 The Joint Commission does not encourage use of any risk assessment model (RAM), such as the Padua Prediction Score to preferentially select high-risk medical patients.3

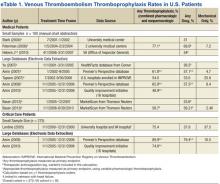

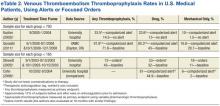

A disparity exists between thromboprophylaxis recommendations and practices in the nonsurgical patient, even when electronic prompts or alerts are available (eTables 1 and 2). In the U.S., pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is administered to 23.6% to 81.1% of medical patients and 37.9% to 79.4% of critical care patients.7-21 In most cases, these rates are liberal estimates, because they include patients who are already on therapeutic anticoagulation or may have received only 1 prophylactic dose during hospitalization.8-11,13-20 When studies exclude patients receiving therapeutic (or treatment doses) anti-coagulation, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates are substantially lower, typically 31% to 33% for medical patients and 37.9% for critical care patients.7,12,21 Furthermore, when studies examine appropriateness of thromboprophylaxis (eg, within the first 2 days of hospitalization or at the correct dose, correct time, or predefined duration), calculations are often less robust.10,11,13,14,22,23

The VHA uses thromboprophylaxis of surgical patients as an external peer review (EPR) performance measure (PM). With the great attention to this national measure, Altom and colleagues reported 89.9% of surgeries adhered.24 Before 2015, VTE thromboprophylaxis EPR PM did not exist. However, the VHA has initiated efforts to assure that providers are adherent to the new indications, which include VTE prophylaxis and treatment.

There is little published literature evaluating VHA performance.Quraishi and colleagues reported a pharmacologic prophylaxis rate of 63% in nonsurgical patients at a single VAMC, facilitated by the use of an admission VTE order set. Unfortunately, their estimate allowed inclusion of 5% of patients receiving treatment doses of anticoagulation and failed to provide any estimates on regimen appropriateness (eg, correct dose, correct time, or correct duration).18 Lentine and colleagues documented a pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate of 48% for a subset of veteran critical care patients who were not already receiving indicated therapeutic anticoagulants.21

Veterans have poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource use than do nonveterans; therefore, it is postulated that veterans can derive clinical benefit from improved attention to thromboprophylaxis benchmarking, performance improvement, and potentially, implementation of electronic alerts or reminder tools.25 Nationally, VHA has no formal inpatient reminder tools to trigger use of thromboprophylaxis for high-risk medical patients, although individual health care systems may have created alerts or tools. Some studies demonstrated that order sets and electronic tools are helpful, whereas others demonstrated potential for harm.17-20,26,27

For any hospitalization at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS), the only electronic prompt to order VTE thromboprophylaxis occurs when the admission order set is completed. But the prompt can be readily bypassed if the quick admission orders are selected. Although no further electronic prompts in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) are invoked following admission, the authors hypothesized that the rate of VTE thromboprophylaxis, specifically pharmacologic, in a subset of veterans with respiratory disease will be higher than the usual published rates.

Purpose and Relevance

This study’s primary aim was to assess the rate of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in veterans with pulmonary disease who were admitted for a nonsurgical stay. The 2 secondary aims were to determine whether thromboprophylaxis was appropriate and to characterize whether differences exist for pharmacologic prophylaxis according to level of care (medical critical care unit [CCU] vs acute care medical ward).

Related: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Total Joint Replacement: Rivaroxaban Update

This analysis emphasizes pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis instead of the combined endpoint of pharmacologic plus nonpharmacologic thromboprophylaxis traditionally used and will supplement the limited literature in 2 understudied cohorts: (1) nonsurgical veteran patients, specifically where advanced computerized thromboprophylaxis alerts are not in use; and (2) patients with the VTE risk factor of respiratory disease.1,7-9,12,13,15,16,18,21

Study Design

This observational study used retrospectively collected data. The data were extracted electronically from the VISN 9 data warehouse by a Decision Support Services analyst and manually validated by an investigator using the CPRS. Prior to initiation of research activities, the VHA Institutional Review Board and the Research and Development Committee at the facility level approved the study.

Sampling

Patients assigned to the treating specialties of medicine and medical critical care during fiscal years 2006 to 2008, admitted for ≥ 24 hours, and discharged with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, or acute, severe respiratory disease (eg, patients requiring mechanical ventilation) were eligible for inclusion. The authors also elected to include patients with asthma, because this diagnosis commonly overlaps with COPD and reflects real-world clinical practice and diagnostic challenges.28 Pneumonia and other infectious pulmonary conditions were not a qualifying diagnosis for study inclusion.

Patients were excluded if aged > 79 years, because it is difficult to maintain de-identification in a small sample of inpatients in this age category. Unfortunately, octogenarians have the highest rate of VTE per 100,000 population and would gain substantial benefit from prophylaxis.29 Similar to other VHA and non-VHA investigators, this study excluded patients who were prescribed therapeutic anticoagulation.7,12,21,30 The authors believe continuation of therapeutic (or treatment) anticoagulation does not measure a clinical decision to use pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, and any interruption of therapeutic anticoagulation suggests that prophylactic anticoagulation is not warranted.

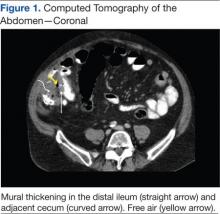

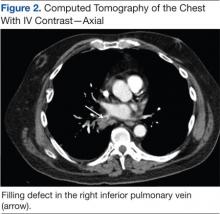

Related: Pulmonary Vein Thrombosis Associated With Metastatic Carcinoma

Additionally, patients were excluded if length of stay (LOS) exceeded 14 days, if known or potential contraindications to thromboprophylaxis existed, or if laboratory data that were needed to assess for contraindications were missing from the electronic data set. Known or potential contraindications included active hemorrhage, hemorrhage within the past 3 months, recent administration of packed red blood cells, bacterial endocarditis, known coagulopathy, recent or current heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or a potential coagulopathy (International Normalized Ratio > 1.5, platelets < 50,000, or an activated partial thromboplastin time > 41 sec).

Contraindications were conservative in construct and were similar to the exclusion-based VTE checklist for the nonsurgical patient.31 The authors did not examine the electronic data set for the contraindication of epidural or spinal anesthesia, because neither is commonly used in the medical ward or medical CCU. The authors also did not exclude patients with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 10 mL/min (a relative contraindication to VTE thromboprophylaxis), although these patients may be at an increased risk for bleeding complications.32

Endpoints and Measures

The primary endpoint of this study was the rate of any pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (eg, ≥ 1 doses), similar to the endpoint selected by other investigators.7-9,12,13,15,16 Secondary endpoints included VTE protected time period on thromboprophylaxis, therapeutic appropriateness ratio for heparin and enoxaparin doses combined, and pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates according to level and location of care.

Sample Size

Although data have been forthcoming, at the time of study inception no studies documented the rate of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis alone (defined as use of ≥ 1 dose of a pharmacologic agent) in patients with the VTE risk factor of respiratory disease.15,23 However, an average combined pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate of 48.8% was determined from available studies.11,14 Although this percentage is an overestimate of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates alone, this value was used to determine a sample size for the cohort.

About 122 subjects would be needed to provide 80% power and a significance level of < 0.05 to assess the hypothesis that pharmacologic prophylaxis rates at TVHS would exceed 60%. Additionally calculated was the sample size necessary to find a 20% expected difference in thromboprophylaxis rates according to location of care (eg, medical ward vs medical CCU), the secondary endpoint. This sample size was calculated to be 180 subjects, or 90 patients in each arm, to provide 80% power and a significance level (2-tailed alpha) of < 0.05. Subsequently, up to 130 patients from each location of care were randomly selected for study inclusion.

Data Analysis

A chi square test was used to compare groups on categorical variables. SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis.

Results

A sample of 3,762 hospitalizations for veterans with COPD, asthma, or acute, severe respiratory disease who received inpatient care in the medical ward or medical CCU were extracted from the data warehouse.

Electronic Data Set

An investigator reviewed the electronic data set, and exclusion criteria that could be ascertained electronically were applied. The primary reasons for exclusion were age (18.4%), potential coagulopathy (14.5%), recent transfusion (14.6%), use of therapeutic anticoagulation (11%), or an extended LOS (7%). Less common reasons for exclusion were coagulation disorders (1.4%), heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (1.2%), recent hemorrhage (1.1%), or missing baseline laboratory values (3.2%). Subsequently, the potential sample of subjects declined to 1,018 (27%) hospitalizations. Of the remaining hospitalizations, 46 and 972 were medical CCU and nonsurgical (medical) inpatients, respectively.

In line with the sampling plan, 130 (13.4%) medical ward hospitalizations were selected using a random number generator. As the ICU sample was smaller than anticipated, the convenience sample of all 46 hospitalizations was used.

Manual Chart Abstraction

Manual chart abstraction (n = 176) clarified physician/provider decision making (eg, some patients were not appropriate for thromboprophylaxis due to upcoming invasive procedures), medical history that could not be extracted by ICD-9 coding (eg, recent non-VHA admissions for medical conditions that were contraindications to prophylaxis), and anticoagulation dosing. These exclusions led to an additional 52 (29.5%) excluded hospitalizations. Reasons for manual exclusion included recent bleeding or at high risk for bleeding (18, 34.6%), incorrect classification as nonsurgical or elective admission (5, 9.6%), no diagnosis of lung disease (21, 40.4%), invasive procedures planned (4, 7.7%), treatment anticoagulant doses selected (4, 7.7%), or patient transferred to a non-VA medical facility due to acuity level (1, 1.9%). One patient was excluded for multiple reasons.

Baseline Demographics

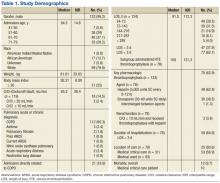

The sample was an elderly, male (98%), white (79.8%) cohort (Table 1). No patients were aged < 40 years. Racial information was missing for 5.6% of the patients. The chief pulmonary diagnosis was COPD, and few patients had new onset, acute, severe respiratory disease (3.2%) prompting admission, because pneumonia was not included as a qualifying diagnosis. Median body mass index (BMI) was 26.31. The median LOS was 3.8 days for the overall cohort and 4.1 days for those receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, although for the latter group a larger proportion of patients were hospitalized for < 3 days. Renal function, according to endpoint definitions, was for using enoxaparin as the appropriate strategy for thromboprophylaxis for the majority (97.5%) of hospitalizations.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

Of those receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, heparin was prescribed most often (62.8%). One patient received both heparin and enoxaparin during a single hospitalization.

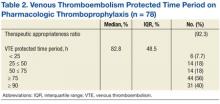

Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was more common in the medical CCU subgroup (80.6%) compared with the nonsurgical patient (56.9%). Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was used in 62.9% of patients (n = 124). However, the therapeutic appropriateness ratio was reduced to 58% of the entire sample (n = 124), because 6 patients of the cohort receiving thromboprophylaxis (n = 78) were prescribed suboptimal doses: Specifically, 1 patient was underdosed and 1 overdosed when prescribed enoxaparin (2, 2.6%). Four patients (5.1%) received underdoses of heparin, based on institutional guidance. For those prescribed pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, the VTE protected time period ratio was 82.8% (Table 2). Overall inpatient mortality rate was low (12, 9.7%). Most deceased patients were managed in the medical CCU (10, 83.3%) and did receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (10, 83.3%).

Discussion

This study demonstrated moderate rates of VTE pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, because 62.9% of nonsurgical patients with respiratory disease who were hospitalized for various reasons were prophylaxed with either SC heparin or enoxaparin. This rate represents active clinical decision making, because there was no indication to prescribe anticoagulation at therapeutic doses. As expected, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was more common in the critical care subgroup (80.6%) compared with the nonsurgical patients (56.9%). Although the study did not meet the intended sample size for this subgroup analysis, results were statistically significant for location of care (P = .014) and may be beneficial for future study design by other investigators.

As early studies of nonsurgical and critical care patients document ≤ 40% of patients receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, this study’s performance seems better.7,12,21 Recently, VHA investigators Quraishi and colleagues seemed to document similar findings. Although 63% of medical patients at the Dayton VAMC in Ohio received appropriate pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, this value must be tempered by the proportion of subjects receiving therapeutic anticoagulation (5.4%).18

Similar to this study’s results, recent studies of nonveterans document pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates of 41% to 51.8%, 41% to 65.9%, and 74.6% to 89.9% in patients with respiratory disease, nonsurgical patients, and critical care patients, respectively. Although findings seem similar to this study’s results, adjustments in estimates again must be made, because these estimates included patients on therapeutic anticoagulation.12,14-16 This study’s results found that 58% of the patient cohort met the therapeutic appropriateness ratio, because they were administered pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis and received correct doses at indicated dosing intervals.

Because stringent exclusion criteria that minimized use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in patients at risk for bleeding were applied, a higher rate of use was expected. This difference between expected and actual rates likely occurred because patient care is individualized and not all factors can be readily assessed in an observational study using retrospective data.

Additionally, for patients who remain ambulatory or have an invasive procedure, thromboprophylaxis may be appropriately delayed past the first 24-hour window of therapy or even temporarily interrupted. Subsequently, the measure of thromboprophylaxis initiation within the first 24 to 48 hours of admission was not elected. Instead, an alternative endpoint of VTE protected time period on thromboprophylaxis was selected. When thromboprophylaxis was used, the median period of protection was 83% of the time period hospitalized for this subgroup. Standardizing to a 7-day period, a VTE protected time period of 83% is coverage for 5.81 days. This would support the Joint Commission ORYX measure that allows for the receipt of thromboprophylaxis within 48 hours of admission to be counted as a success.6

Unfortunately, the authors did not assess whether mechanical thromboprophylaxis was provided to the remaining one-third of patients not receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. As a result, the complete data set is lacking, which would document whether the Joint Commission measure of ≥ 95% of the time was achieved. Therefore, the claim that TVHS is a top performing hospital for this ORYX measure cannot be made.

Although this study demonstrated a low mortality rate, this rate was not selected as a measure of interest, since one meta-analysis has demonstrated no mortality benefit from VTE thromboprophylaxis.4 Although in-hospital mortality may be an appropriate measure for critical care patients, most of the study patients did not meet this criterion.21 Last, mortality should be assessed no earlier than 30 days from admission.17 Subsequently, statistical assessment and conclusions from this measure are not relevant.

Limitations

A number of limitations hindered the generalizability of the results. This was an observational study using retrospectively collected data. The sample was narrowed to those with chronic respiratory disease, which has been less studied and typically examined in concert with acute processes, such as pneumonia. The demographic was primarily white males. The BMI of subjects enrolled in this study (26 kg/m2) was lower than the BMI of nonveteran subjects with COPD (28.6 kg/m2), nonveteran subjects with COPD and VTE (29 kg/m2), or veteran nonsurgical patients receiving thromboprophylaxis (29 kg/m2).18,34,35

The exclusion criteria resulted in a 73% reduction in the cohort and severely limited the number of medical critical care patients included. However, the problem of a small cohort was anticipated.

Other researchers conducting a prospective VHA thromboprophylaxis study found only 7.6% of veterans screened were eligible for enrollment, although 25% of subjects were anticipated by chart review. Two of the 3 primary reasons for trial exclusion were indication for therapeutic anticoagulation and contraindications to heparin (other than thrombocytopenia), and these were also primary reasons for exclusion in this study.30 Subsequently, the cohort appropriate for thromboprophylaxis in VHA seems relatively small.

Additionally, mobility is difficult to judge in a chart review. Day-to-day clinical assessments of mobility lead to individualization of care, including delayed initiation and timely termination of thromboprophylaxis. It is also possible that a significant portion of the patients had mechanical thromboprophylaxis, because they may have had an unrecognized risk factor for bleeding or patient preferences were considered. Last, some veterans may have classified as palliative care, and VTE prophylaxis may have been omitted for comfort care purposes.32

This study was not designed to evaluate the Padua Prediction Score, which categorizes risk and ration-alizes use of thromboprophylaxis for nonsurgical patients.3 This tool eliminates many of the established risk factors for VTE, including COPD, which was a qualifying diagnosis for inclusion in this study.1 It is not clear how the Padua Prediction Score would categorize the inpatient veteran population. Veterans clearly have poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource use compared with the general patient population.25

Veterans with COPD have a higher comorbid illness burden than that of veterans without COPD.36 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with VTE development, and when VTE develops in patients with COPD, mortality is greater than that of patients without COPD.37,38 VTE mortality may be related to an increased likelihood of fatal pulmonary embolism.39 Therefore, the authors recommend that VHA conduct studies to examine the Padua Prediction Score and potentially other RAMs that include COPD subjects, to determine what tool should be used in VHA.32

The authors also recommend that VHA evaluate how to improve thromboprophylaxis care with time-based studies. Since manual extraction to determine study inclusion was a time-consuming process, this time frame likely was a barrier to physician implementation of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. Therefore an electronic tool that serves as a daily reminder for subjects calculated as high risk for VTE but low risk for bleeding may improve clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Overall, about one-third of patients did not receive potentially indicated pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis on the medical wards. Use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in medical CCU patients was robust (80%). Doses and dosing intervals were appropriate for > 90% of patients, and therapy clearly was started early and continued for much of the at-risk period, as the VTE protected time period exceeded 80%. Although computerized tools were limited, the authors feel their modest pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate is related to the facility’s teaching hospital affiliation or the provider mix, because TVHS is one of the largest VA cardiology centers in the U.S.7,8,13

As it was challenging and time consuming to locate eligible subjects, it may also prove difficult for the admitting physician to have the same luxury of time to look for specific at-risk diagnoses in the medical record and evaluate for exclusions to therapy. If electronic alerts and reminder tools were included in clinical pharmacy inpatient templates, the authors believe the frequency of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis would further improve in the facility. Also, the authors encourage VHA researchers to further evaluate VTE prophylaxis RAM, the role of daily electronic reminders, and tools to calculate VTE and bleeding risk.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to James Minnis, PharmD, BCPS, and April Ungar, PharmD, BCPS, for their contributions to the study design. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Geerts WH, Bergquist D, Pineo G, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(suppl 6):381S-453S.

2. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al; on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(1):e6-e245.

3. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e195S-e226S.

4. Wein L, Wein S, Haas SJ, Shaw J, Krum H. Pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1476-1486.

5. Ruiz EM, Utrilla GB, Alvarez JL, Perrin RS. Effectiveness and safety of thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin in medical inpatients. Thromb Res. 2011;128(5):440-445.

6. The Joint Commission. Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. http://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality _measures.aspx. The Joint Commission Website. Accessed March 5, 2015.

7. Stark JE, Kilzer WJ. Venous thromboembolic prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(1):36-40.

8. Peterman CM, Kolansky DM, Spinler SA. Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients: An observational study. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(8):1086-1090.

9. Herbers J, Zarter S. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):E21-E25.

10. Yu HT, Dylan ML, Lin J, Dubois RW. Hospitals’ compliance with prophylaxis guidelines for venous thromboembolism. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64(1):69-76.

11. Amin A, Stemkowski S, Lin J, Yang G. Thromboprophylaxis rates in US medical centers: Success or failure? J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(8):1610-1616.

12. Tapson VF, Decousus H, Pini M, et al; IMPROVE Investigators. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: Findings from the International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism. Chest. 2007;132(3):936-945.

13. Amin AN, Stemkowski S, Lin J, Yang G. Inpatient thromboprophylaxis use in U.S. hospitals: Adherence to the Seventh American College of Chest Physician’s recommendations for at-risk medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E15-E21.

14. Amin A, Spyropoulos AC, Dobesh P, et al. Are hospitals delivering appropriate VTE prevention? The venous thromboembolism study to assess the rate of thromboprophylaxis (VTE Start). J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;29(3):326-339.

15. Baser O, Liu X, Phatak H, Wang L, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and clinical consequences in medically ill patients. Am J Ther. 2013:20(2):132-142.

16. Baser O, Sengupta N, Dysinger A, Wang L. Thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical inpatients: Effect on outcomes and costs. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(6):294-302.

17. Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):969-977.

18. Quraishi MB, Mathew R, Lowes A, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and the impact of standardized guidelines: Is a computer-based approach enough? J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2011;18(11):505-512.

19. Stinnett JM, Pendleton R, Skordos L, Wheeler M, Rodgers GM. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medically ill patients and the development of strategies to improve prophylaxis rates. Am J Hematol. 2005;78(3):167-172.

20. Cohn SL, Adekile A, Mahabir V. Improved use of thromboprophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis following an educational intervention. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):331-338.

21. Lentine KL, Flavin KE, Gould MK. Variability in the use of thromboprophylaxis and outcomes in critically ill medical patients. Am J Med. 2005;118(12):1373-1380.

22. Pendergraft T, Liu X, Edelsberg J, Phatak H, et al. Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medically ill patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(1):75-82.

23. Rothberg MB, Lahti M, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical patients at US hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):489-494.

24. Altom LK, Deierhoi RJ, Grams J, et al. Association between Surgical Care Improvement Program venous thromboembolism measures and postoperative events. Am J Surg. 2012;204(5):591-597.

25. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21): 3252-3257.

26. Pham DQ, Pham AQ, Ullah E, McFarlane SI, Payne R. Short communication: Evaluating the appropriateness of thromboprophylaxis in an acute care setting using a computerised reminder, through order-entry system. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(1):134-137.

27. Khanna R, Vittinghoff E, Maselli J, Auerbach A. Unintended consequences of a standard admission order set on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27(3):318-324.

28. Barr RG, Celli VR, Mannino DM, et al. Comorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPD. Am J Med. 2009;122(4):348-355.

29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism in adult hospitalizations – United States, 2007-2009. (MMWR) Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(22):401-404.

30. Lederle FA, Sacks JN, Fiore L, et al. The prophylaxis of medical patients for thromboembolism pilot study. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):54-59.

31. Dobromirski M, Cohen AT. How I manage venous thromboembolism risk in hospitalized medical patients. Blood. 2012;120(8):1562-1569.

32. Polich AL, Etherton GM, Knezevich JT, Rousek JB, Masek CM, Hallbeck MS. Can eliminating risk stratification improve medical residents’ adherence to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis? Acad Med. 2011;86(12):1518-1524.

33. King CS, Holley AB, Jackson JL, Shorr AF, Moores LK. Twice vs three times daily heparin dosing for thromboembolism prophylaxis in the general medical population: A metaanalysis. Chest. 2007;131(2):507-516.

34. Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ, Kroll A, Goldberg RJ, Emery C, Spencer FA. Venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2012;125(10):1010-1018.

35. Niewoehner DE, Lokhnygina Y, Rice K, et al. Risk indexes for exacerbations and hospitalizations due to COPD. Chest. 2007;131(1):20-28.

36. Sharafkhaneh A. Peterson NJ, Yu HJ, Dalal AA, Johnson ML, Hanania NA. Burden of COPD in a government health care system: A retrospective observational study using data from the US Veterans Affairs population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:125-132.

37. Shetty R, Seddighzadeh A, Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and deep venous thrombosis: a prevalent combination. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;26(1):35-40.

38. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Duff A, Kelley MA. Pulmonary embolism and mortality in patients with COPD. Chest. 1996;110(5):1212-1219.

39. Huerta C, Johansson S, Wallander MA, García Rodríguez LA. Risk factors and short-term mortality of venous thromboembolism diagnosed in the primary care setting in the United Kingdom. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(9):935-943.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is an important public health concern. Deep venous thrombosis is estimated to affect 10% to 20% of medical (nonsurgical) patients, 15% to 40% of stroke patients, and 10% to 80% of critical care patients who are not prophylaxed.1 Venous thromboembolism is associated with significant resource utilization, long-term sequelae, recurrent events, and sudden death.2

The current guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians recommend use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis as the preferred strategy for nonsurgical (or medical) patients (IB, formerly IA, recommendation) and for critically ill patients (2C recommendation) at low risk for bleeding.1,3 Mechanical (or nonpharmacologic) thromboprophylaxis (eg, intermittent pneumatic compression) is an alternative for those at increased risk for bleeding (2C recommendation).3 Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in high-risk patients, similar to those studied in randomized controlled clinical trials, reduces the occurrence of symptomatic DVT by 34 events per 1,000 patients treated.3 However, data are conflicting regarding mortality benefit.4,5

Related: Trends in Venous Thromboembolism

The Joint Commission adopted any thromboprophylaxis (measure includes pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic strategies) as a core discretionary measure in the ORYX (National Quality Hospital Measures) program. The ORYX measurements are intended to support Joint Commission-accredited organizations in institutional quality improvement efforts. The thromboprophylaxis core measure became effective May 2009 and remains as an option for hospitals to meet the 4 core measure set accreditation requirement. A top-performing hospital should provide this measure to applicable patients ≥ 95% of the time, according to the Joint Commission.6 The Joint Commission does not encourage use of any risk assessment model (RAM), such as the Padua Prediction Score to preferentially select high-risk medical patients.3

A disparity exists between thromboprophylaxis recommendations and practices in the nonsurgical patient, even when electronic prompts or alerts are available (eTables 1 and 2). In the U.S., pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is administered to 23.6% to 81.1% of medical patients and 37.9% to 79.4% of critical care patients.7-21 In most cases, these rates are liberal estimates, because they include patients who are already on therapeutic anticoagulation or may have received only 1 prophylactic dose during hospitalization.8-11,13-20 When studies exclude patients receiving therapeutic (or treatment doses) anti-coagulation, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates are substantially lower, typically 31% to 33% for medical patients and 37.9% for critical care patients.7,12,21 Furthermore, when studies examine appropriateness of thromboprophylaxis (eg, within the first 2 days of hospitalization or at the correct dose, correct time, or predefined duration), calculations are often less robust.10,11,13,14,22,23

The VHA uses thromboprophylaxis of surgical patients as an external peer review (EPR) performance measure (PM). With the great attention to this national measure, Altom and colleagues reported 89.9% of surgeries adhered.24 Before 2015, VTE thromboprophylaxis EPR PM did not exist. However, the VHA has initiated efforts to assure that providers are adherent to the new indications, which include VTE prophylaxis and treatment.

There is little published literature evaluating VHA performance.Quraishi and colleagues reported a pharmacologic prophylaxis rate of 63% in nonsurgical patients at a single VAMC, facilitated by the use of an admission VTE order set. Unfortunately, their estimate allowed inclusion of 5% of patients receiving treatment doses of anticoagulation and failed to provide any estimates on regimen appropriateness (eg, correct dose, correct time, or correct duration).18 Lentine and colleagues documented a pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate of 48% for a subset of veteran critical care patients who were not already receiving indicated therapeutic anticoagulants.21

Veterans have poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource use than do nonveterans; therefore, it is postulated that veterans can derive clinical benefit from improved attention to thromboprophylaxis benchmarking, performance improvement, and potentially, implementation of electronic alerts or reminder tools.25 Nationally, VHA has no formal inpatient reminder tools to trigger use of thromboprophylaxis for high-risk medical patients, although individual health care systems may have created alerts or tools. Some studies demonstrated that order sets and electronic tools are helpful, whereas others demonstrated potential for harm.17-20,26,27

For any hospitalization at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS), the only electronic prompt to order VTE thromboprophylaxis occurs when the admission order set is completed. But the prompt can be readily bypassed if the quick admission orders are selected. Although no further electronic prompts in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) are invoked following admission, the authors hypothesized that the rate of VTE thromboprophylaxis, specifically pharmacologic, in a subset of veterans with respiratory disease will be higher than the usual published rates.

Purpose and Relevance

This study’s primary aim was to assess the rate of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in veterans with pulmonary disease who were admitted for a nonsurgical stay. The 2 secondary aims were to determine whether thromboprophylaxis was appropriate and to characterize whether differences exist for pharmacologic prophylaxis according to level of care (medical critical care unit [CCU] vs acute care medical ward).

Related: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Total Joint Replacement: Rivaroxaban Update

This analysis emphasizes pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis instead of the combined endpoint of pharmacologic plus nonpharmacologic thromboprophylaxis traditionally used and will supplement the limited literature in 2 understudied cohorts: (1) nonsurgical veteran patients, specifically where advanced computerized thromboprophylaxis alerts are not in use; and (2) patients with the VTE risk factor of respiratory disease.1,7-9,12,13,15,16,18,21

Study Design

This observational study used retrospectively collected data. The data were extracted electronically from the VISN 9 data warehouse by a Decision Support Services analyst and manually validated by an investigator using the CPRS. Prior to initiation of research activities, the VHA Institutional Review Board and the Research and Development Committee at the facility level approved the study.

Sampling

Patients assigned to the treating specialties of medicine and medical critical care during fiscal years 2006 to 2008, admitted for ≥ 24 hours, and discharged with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, or acute, severe respiratory disease (eg, patients requiring mechanical ventilation) were eligible for inclusion. The authors also elected to include patients with asthma, because this diagnosis commonly overlaps with COPD and reflects real-world clinical practice and diagnostic challenges.28 Pneumonia and other infectious pulmonary conditions were not a qualifying diagnosis for study inclusion.

Patients were excluded if aged > 79 years, because it is difficult to maintain de-identification in a small sample of inpatients in this age category. Unfortunately, octogenarians have the highest rate of VTE per 100,000 population and would gain substantial benefit from prophylaxis.29 Similar to other VHA and non-VHA investigators, this study excluded patients who were prescribed therapeutic anticoagulation.7,12,21,30 The authors believe continuation of therapeutic (or treatment) anticoagulation does not measure a clinical decision to use pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, and any interruption of therapeutic anticoagulation suggests that prophylactic anticoagulation is not warranted.

Related: Pulmonary Vein Thrombosis Associated With Metastatic Carcinoma

Additionally, patients were excluded if length of stay (LOS) exceeded 14 days, if known or potential contraindications to thromboprophylaxis existed, or if laboratory data that were needed to assess for contraindications were missing from the electronic data set. Known or potential contraindications included active hemorrhage, hemorrhage within the past 3 months, recent administration of packed red blood cells, bacterial endocarditis, known coagulopathy, recent or current heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or a potential coagulopathy (International Normalized Ratio > 1.5, platelets < 50,000, or an activated partial thromboplastin time > 41 sec).

Contraindications were conservative in construct and were similar to the exclusion-based VTE checklist for the nonsurgical patient.31 The authors did not examine the electronic data set for the contraindication of epidural or spinal anesthesia, because neither is commonly used in the medical ward or medical CCU. The authors also did not exclude patients with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 10 mL/min (a relative contraindication to VTE thromboprophylaxis), although these patients may be at an increased risk for bleeding complications.32

Endpoints and Measures

The primary endpoint of this study was the rate of any pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (eg, ≥ 1 doses), similar to the endpoint selected by other investigators.7-9,12,13,15,16 Secondary endpoints included VTE protected time period on thromboprophylaxis, therapeutic appropriateness ratio for heparin and enoxaparin doses combined, and pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates according to level and location of care.

Sample Size

Although data have been forthcoming, at the time of study inception no studies documented the rate of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis alone (defined as use of ≥ 1 dose of a pharmacologic agent) in patients with the VTE risk factor of respiratory disease.15,23 However, an average combined pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate of 48.8% was determined from available studies.11,14 Although this percentage is an overestimate of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates alone, this value was used to determine a sample size for the cohort.

About 122 subjects would be needed to provide 80% power and a significance level of < 0.05 to assess the hypothesis that pharmacologic prophylaxis rates at TVHS would exceed 60%. Additionally calculated was the sample size necessary to find a 20% expected difference in thromboprophylaxis rates according to location of care (eg, medical ward vs medical CCU), the secondary endpoint. This sample size was calculated to be 180 subjects, or 90 patients in each arm, to provide 80% power and a significance level (2-tailed alpha) of < 0.05. Subsequently, up to 130 patients from each location of care were randomly selected for study inclusion.

Data Analysis

A chi square test was used to compare groups on categorical variables. SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis.

Results

A sample of 3,762 hospitalizations for veterans with COPD, asthma, or acute, severe respiratory disease who received inpatient care in the medical ward or medical CCU were extracted from the data warehouse.

Electronic Data Set

An investigator reviewed the electronic data set, and exclusion criteria that could be ascertained electronically were applied. The primary reasons for exclusion were age (18.4%), potential coagulopathy (14.5%), recent transfusion (14.6%), use of therapeutic anticoagulation (11%), or an extended LOS (7%). Less common reasons for exclusion were coagulation disorders (1.4%), heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (1.2%), recent hemorrhage (1.1%), or missing baseline laboratory values (3.2%). Subsequently, the potential sample of subjects declined to 1,018 (27%) hospitalizations. Of the remaining hospitalizations, 46 and 972 were medical CCU and nonsurgical (medical) inpatients, respectively.

In line with the sampling plan, 130 (13.4%) medical ward hospitalizations were selected using a random number generator. As the ICU sample was smaller than anticipated, the convenience sample of all 46 hospitalizations was used.

Manual Chart Abstraction

Manual chart abstraction (n = 176) clarified physician/provider decision making (eg, some patients were not appropriate for thromboprophylaxis due to upcoming invasive procedures), medical history that could not be extracted by ICD-9 coding (eg, recent non-VHA admissions for medical conditions that were contraindications to prophylaxis), and anticoagulation dosing. These exclusions led to an additional 52 (29.5%) excluded hospitalizations. Reasons for manual exclusion included recent bleeding or at high risk for bleeding (18, 34.6%), incorrect classification as nonsurgical or elective admission (5, 9.6%), no diagnosis of lung disease (21, 40.4%), invasive procedures planned (4, 7.7%), treatment anticoagulant doses selected (4, 7.7%), or patient transferred to a non-VA medical facility due to acuity level (1, 1.9%). One patient was excluded for multiple reasons.

Baseline Demographics

The sample was an elderly, male (98%), white (79.8%) cohort (Table 1). No patients were aged < 40 years. Racial information was missing for 5.6% of the patients. The chief pulmonary diagnosis was COPD, and few patients had new onset, acute, severe respiratory disease (3.2%) prompting admission, because pneumonia was not included as a qualifying diagnosis. Median body mass index (BMI) was 26.31. The median LOS was 3.8 days for the overall cohort and 4.1 days for those receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, although for the latter group a larger proportion of patients were hospitalized for < 3 days. Renal function, according to endpoint definitions, was for using enoxaparin as the appropriate strategy for thromboprophylaxis for the majority (97.5%) of hospitalizations.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

Of those receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, heparin was prescribed most often (62.8%). One patient received both heparin and enoxaparin during a single hospitalization.

Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was more common in the medical CCU subgroup (80.6%) compared with the nonsurgical patient (56.9%). Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was used in 62.9% of patients (n = 124). However, the therapeutic appropriateness ratio was reduced to 58% of the entire sample (n = 124), because 6 patients of the cohort receiving thromboprophylaxis (n = 78) were prescribed suboptimal doses: Specifically, 1 patient was underdosed and 1 overdosed when prescribed enoxaparin (2, 2.6%). Four patients (5.1%) received underdoses of heparin, based on institutional guidance. For those prescribed pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, the VTE protected time period ratio was 82.8% (Table 2). Overall inpatient mortality rate was low (12, 9.7%). Most deceased patients were managed in the medical CCU (10, 83.3%) and did receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (10, 83.3%).

Discussion

This study demonstrated moderate rates of VTE pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, because 62.9% of nonsurgical patients with respiratory disease who were hospitalized for various reasons were prophylaxed with either SC heparin or enoxaparin. This rate represents active clinical decision making, because there was no indication to prescribe anticoagulation at therapeutic doses. As expected, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was more common in the critical care subgroup (80.6%) compared with the nonsurgical patients (56.9%). Although the study did not meet the intended sample size for this subgroup analysis, results were statistically significant for location of care (P = .014) and may be beneficial for future study design by other investigators.

As early studies of nonsurgical and critical care patients document ≤ 40% of patients receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, this study’s performance seems better.7,12,21 Recently, VHA investigators Quraishi and colleagues seemed to document similar findings. Although 63% of medical patients at the Dayton VAMC in Ohio received appropriate pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, this value must be tempered by the proportion of subjects receiving therapeutic anticoagulation (5.4%).18

Similar to this study’s results, recent studies of nonveterans document pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates of 41% to 51.8%, 41% to 65.9%, and 74.6% to 89.9% in patients with respiratory disease, nonsurgical patients, and critical care patients, respectively. Although findings seem similar to this study’s results, adjustments in estimates again must be made, because these estimates included patients on therapeutic anticoagulation.12,14-16 This study’s results found that 58% of the patient cohort met the therapeutic appropriateness ratio, because they were administered pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis and received correct doses at indicated dosing intervals.

Because stringent exclusion criteria that minimized use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in patients at risk for bleeding were applied, a higher rate of use was expected. This difference between expected and actual rates likely occurred because patient care is individualized and not all factors can be readily assessed in an observational study using retrospective data.

Additionally, for patients who remain ambulatory or have an invasive procedure, thromboprophylaxis may be appropriately delayed past the first 24-hour window of therapy or even temporarily interrupted. Subsequently, the measure of thromboprophylaxis initiation within the first 24 to 48 hours of admission was not elected. Instead, an alternative endpoint of VTE protected time period on thromboprophylaxis was selected. When thromboprophylaxis was used, the median period of protection was 83% of the time period hospitalized for this subgroup. Standardizing to a 7-day period, a VTE protected time period of 83% is coverage for 5.81 days. This would support the Joint Commission ORYX measure that allows for the receipt of thromboprophylaxis within 48 hours of admission to be counted as a success.6

Unfortunately, the authors did not assess whether mechanical thromboprophylaxis was provided to the remaining one-third of patients not receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. As a result, the complete data set is lacking, which would document whether the Joint Commission measure of ≥ 95% of the time was achieved. Therefore, the claim that TVHS is a top performing hospital for this ORYX measure cannot be made.

Although this study demonstrated a low mortality rate, this rate was not selected as a measure of interest, since one meta-analysis has demonstrated no mortality benefit from VTE thromboprophylaxis.4 Although in-hospital mortality may be an appropriate measure for critical care patients, most of the study patients did not meet this criterion.21 Last, mortality should be assessed no earlier than 30 days from admission.17 Subsequently, statistical assessment and conclusions from this measure are not relevant.

Limitations

A number of limitations hindered the generalizability of the results. This was an observational study using retrospectively collected data. The sample was narrowed to those with chronic respiratory disease, which has been less studied and typically examined in concert with acute processes, such as pneumonia. The demographic was primarily white males. The BMI of subjects enrolled in this study (26 kg/m2) was lower than the BMI of nonveteran subjects with COPD (28.6 kg/m2), nonveteran subjects with COPD and VTE (29 kg/m2), or veteran nonsurgical patients receiving thromboprophylaxis (29 kg/m2).18,34,35

The exclusion criteria resulted in a 73% reduction in the cohort and severely limited the number of medical critical care patients included. However, the problem of a small cohort was anticipated.

Other researchers conducting a prospective VHA thromboprophylaxis study found only 7.6% of veterans screened were eligible for enrollment, although 25% of subjects were anticipated by chart review. Two of the 3 primary reasons for trial exclusion were indication for therapeutic anticoagulation and contraindications to heparin (other than thrombocytopenia), and these were also primary reasons for exclusion in this study.30 Subsequently, the cohort appropriate for thromboprophylaxis in VHA seems relatively small.

Additionally, mobility is difficult to judge in a chart review. Day-to-day clinical assessments of mobility lead to individualization of care, including delayed initiation and timely termination of thromboprophylaxis. It is also possible that a significant portion of the patients had mechanical thromboprophylaxis, because they may have had an unrecognized risk factor for bleeding or patient preferences were considered. Last, some veterans may have classified as palliative care, and VTE prophylaxis may have been omitted for comfort care purposes.32

This study was not designed to evaluate the Padua Prediction Score, which categorizes risk and ration-alizes use of thromboprophylaxis for nonsurgical patients.3 This tool eliminates many of the established risk factors for VTE, including COPD, which was a qualifying diagnosis for inclusion in this study.1 It is not clear how the Padua Prediction Score would categorize the inpatient veteran population. Veterans clearly have poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource use compared with the general patient population.25

Veterans with COPD have a higher comorbid illness burden than that of veterans without COPD.36 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with VTE development, and when VTE develops in patients with COPD, mortality is greater than that of patients without COPD.37,38 VTE mortality may be related to an increased likelihood of fatal pulmonary embolism.39 Therefore, the authors recommend that VHA conduct studies to examine the Padua Prediction Score and potentially other RAMs that include COPD subjects, to determine what tool should be used in VHA.32

The authors also recommend that VHA evaluate how to improve thromboprophylaxis care with time-based studies. Since manual extraction to determine study inclusion was a time-consuming process, this time frame likely was a barrier to physician implementation of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. Therefore an electronic tool that serves as a daily reminder for subjects calculated as high risk for VTE but low risk for bleeding may improve clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Overall, about one-third of patients did not receive potentially indicated pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis on the medical wards. Use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in medical CCU patients was robust (80%). Doses and dosing intervals were appropriate for > 90% of patients, and therapy clearly was started early and continued for much of the at-risk period, as the VTE protected time period exceeded 80%. Although computerized tools were limited, the authors feel their modest pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate is related to the facility’s teaching hospital affiliation or the provider mix, because TVHS is one of the largest VA cardiology centers in the U.S.7,8,13

As it was challenging and time consuming to locate eligible subjects, it may also prove difficult for the admitting physician to have the same luxury of time to look for specific at-risk diagnoses in the medical record and evaluate for exclusions to therapy. If electronic alerts and reminder tools were included in clinical pharmacy inpatient templates, the authors believe the frequency of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis would further improve in the facility. Also, the authors encourage VHA researchers to further evaluate VTE prophylaxis RAM, the role of daily electronic reminders, and tools to calculate VTE and bleeding risk.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to James Minnis, PharmD, BCPS, and April Ungar, PharmD, BCPS, for their contributions to the study design. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, is an important public health concern. Deep venous thrombosis is estimated to affect 10% to 20% of medical (nonsurgical) patients, 15% to 40% of stroke patients, and 10% to 80% of critical care patients who are not prophylaxed.1 Venous thromboembolism is associated with significant resource utilization, long-term sequelae, recurrent events, and sudden death.2

The current guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians recommend use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis as the preferred strategy for nonsurgical (or medical) patients (IB, formerly IA, recommendation) and for critically ill patients (2C recommendation) at low risk for bleeding.1,3 Mechanical (or nonpharmacologic) thromboprophylaxis (eg, intermittent pneumatic compression) is an alternative for those at increased risk for bleeding (2C recommendation).3 Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in high-risk patients, similar to those studied in randomized controlled clinical trials, reduces the occurrence of symptomatic DVT by 34 events per 1,000 patients treated.3 However, data are conflicting regarding mortality benefit.4,5

Related: Trends in Venous Thromboembolism

The Joint Commission adopted any thromboprophylaxis (measure includes pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic strategies) as a core discretionary measure in the ORYX (National Quality Hospital Measures) program. The ORYX measurements are intended to support Joint Commission-accredited organizations in institutional quality improvement efforts. The thromboprophylaxis core measure became effective May 2009 and remains as an option for hospitals to meet the 4 core measure set accreditation requirement. A top-performing hospital should provide this measure to applicable patients ≥ 95% of the time, according to the Joint Commission.6 The Joint Commission does not encourage use of any risk assessment model (RAM), such as the Padua Prediction Score to preferentially select high-risk medical patients.3

A disparity exists between thromboprophylaxis recommendations and practices in the nonsurgical patient, even when electronic prompts or alerts are available (eTables 1 and 2). In the U.S., pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is administered to 23.6% to 81.1% of medical patients and 37.9% to 79.4% of critical care patients.7-21 In most cases, these rates are liberal estimates, because they include patients who are already on therapeutic anticoagulation or may have received only 1 prophylactic dose during hospitalization.8-11,13-20 When studies exclude patients receiving therapeutic (or treatment doses) anti-coagulation, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates are substantially lower, typically 31% to 33% for medical patients and 37.9% for critical care patients.7,12,21 Furthermore, when studies examine appropriateness of thromboprophylaxis (eg, within the first 2 days of hospitalization or at the correct dose, correct time, or predefined duration), calculations are often less robust.10,11,13,14,22,23

The VHA uses thromboprophylaxis of surgical patients as an external peer review (EPR) performance measure (PM). With the great attention to this national measure, Altom and colleagues reported 89.9% of surgeries adhered.24 Before 2015, VTE thromboprophylaxis EPR PM did not exist. However, the VHA has initiated efforts to assure that providers are adherent to the new indications, which include VTE prophylaxis and treatment.

There is little published literature evaluating VHA performance.Quraishi and colleagues reported a pharmacologic prophylaxis rate of 63% in nonsurgical patients at a single VAMC, facilitated by the use of an admission VTE order set. Unfortunately, their estimate allowed inclusion of 5% of patients receiving treatment doses of anticoagulation and failed to provide any estimates on regimen appropriateness (eg, correct dose, correct time, or correct duration).18 Lentine and colleagues documented a pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate of 48% for a subset of veteran critical care patients who were not already receiving indicated therapeutic anticoagulants.21

Veterans have poorer health status, more medical conditions, and higher medical resource use than do nonveterans; therefore, it is postulated that veterans can derive clinical benefit from improved attention to thromboprophylaxis benchmarking, performance improvement, and potentially, implementation of electronic alerts or reminder tools.25 Nationally, VHA has no formal inpatient reminder tools to trigger use of thromboprophylaxis for high-risk medical patients, although individual health care systems may have created alerts or tools. Some studies demonstrated that order sets and electronic tools are helpful, whereas others demonstrated potential for harm.17-20,26,27

For any hospitalization at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS), the only electronic prompt to order VTE thromboprophylaxis occurs when the admission order set is completed. But the prompt can be readily bypassed if the quick admission orders are selected. Although no further electronic prompts in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) are invoked following admission, the authors hypothesized that the rate of VTE thromboprophylaxis, specifically pharmacologic, in a subset of veterans with respiratory disease will be higher than the usual published rates.

Purpose and Relevance

This study’s primary aim was to assess the rate of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in veterans with pulmonary disease who were admitted for a nonsurgical stay. The 2 secondary aims were to determine whether thromboprophylaxis was appropriate and to characterize whether differences exist for pharmacologic prophylaxis according to level of care (medical critical care unit [CCU] vs acute care medical ward).

Related: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Total Joint Replacement: Rivaroxaban Update

This analysis emphasizes pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis instead of the combined endpoint of pharmacologic plus nonpharmacologic thromboprophylaxis traditionally used and will supplement the limited literature in 2 understudied cohorts: (1) nonsurgical veteran patients, specifically where advanced computerized thromboprophylaxis alerts are not in use; and (2) patients with the VTE risk factor of respiratory disease.1,7-9,12,13,15,16,18,21

Study Design

This observational study used retrospectively collected data. The data were extracted electronically from the VISN 9 data warehouse by a Decision Support Services analyst and manually validated by an investigator using the CPRS. Prior to initiation of research activities, the VHA Institutional Review Board and the Research and Development Committee at the facility level approved the study.

Sampling

Patients assigned to the treating specialties of medicine and medical critical care during fiscal years 2006 to 2008, admitted for ≥ 24 hours, and discharged with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, or acute, severe respiratory disease (eg, patients requiring mechanical ventilation) were eligible for inclusion. The authors also elected to include patients with asthma, because this diagnosis commonly overlaps with COPD and reflects real-world clinical practice and diagnostic challenges.28 Pneumonia and other infectious pulmonary conditions were not a qualifying diagnosis for study inclusion.

Patients were excluded if aged > 79 years, because it is difficult to maintain de-identification in a small sample of inpatients in this age category. Unfortunately, octogenarians have the highest rate of VTE per 100,000 population and would gain substantial benefit from prophylaxis.29 Similar to other VHA and non-VHA investigators, this study excluded patients who were prescribed therapeutic anticoagulation.7,12,21,30 The authors believe continuation of therapeutic (or treatment) anticoagulation does not measure a clinical decision to use pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, and any interruption of therapeutic anticoagulation suggests that prophylactic anticoagulation is not warranted.

Related: Pulmonary Vein Thrombosis Associated With Metastatic Carcinoma

Additionally, patients were excluded if length of stay (LOS) exceeded 14 days, if known or potential contraindications to thromboprophylaxis existed, or if laboratory data that were needed to assess for contraindications were missing from the electronic data set. Known or potential contraindications included active hemorrhage, hemorrhage within the past 3 months, recent administration of packed red blood cells, bacterial endocarditis, known coagulopathy, recent or current heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or a potential coagulopathy (International Normalized Ratio > 1.5, platelets < 50,000, or an activated partial thromboplastin time > 41 sec).

Contraindications were conservative in construct and were similar to the exclusion-based VTE checklist for the nonsurgical patient.31 The authors did not examine the electronic data set for the contraindication of epidural or spinal anesthesia, because neither is commonly used in the medical ward or medical CCU. The authors also did not exclude patients with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 10 mL/min (a relative contraindication to VTE thromboprophylaxis), although these patients may be at an increased risk for bleeding complications.32

Endpoints and Measures

The primary endpoint of this study was the rate of any pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (eg, ≥ 1 doses), similar to the endpoint selected by other investigators.7-9,12,13,15,16 Secondary endpoints included VTE protected time period on thromboprophylaxis, therapeutic appropriateness ratio for heparin and enoxaparin doses combined, and pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates according to level and location of care.

Sample Size

Although data have been forthcoming, at the time of study inception no studies documented the rate of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis alone (defined as use of ≥ 1 dose of a pharmacologic agent) in patients with the VTE risk factor of respiratory disease.15,23 However, an average combined pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rate of 48.8% was determined from available studies.11,14 Although this percentage is an overestimate of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates alone, this value was used to determine a sample size for the cohort.

About 122 subjects would be needed to provide 80% power and a significance level of < 0.05 to assess the hypothesis that pharmacologic prophylaxis rates at TVHS would exceed 60%. Additionally calculated was the sample size necessary to find a 20% expected difference in thromboprophylaxis rates according to location of care (eg, medical ward vs medical CCU), the secondary endpoint. This sample size was calculated to be 180 subjects, or 90 patients in each arm, to provide 80% power and a significance level (2-tailed alpha) of < 0.05. Subsequently, up to 130 patients from each location of care were randomly selected for study inclusion.

Data Analysis

A chi square test was used to compare groups on categorical variables. SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis.

Results

A sample of 3,762 hospitalizations for veterans with COPD, asthma, or acute, severe respiratory disease who received inpatient care in the medical ward or medical CCU were extracted from the data warehouse.

Electronic Data Set

An investigator reviewed the electronic data set, and exclusion criteria that could be ascertained electronically were applied. The primary reasons for exclusion were age (18.4%), potential coagulopathy (14.5%), recent transfusion (14.6%), use of therapeutic anticoagulation (11%), or an extended LOS (7%). Less common reasons for exclusion were coagulation disorders (1.4%), heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (1.2%), recent hemorrhage (1.1%), or missing baseline laboratory values (3.2%). Subsequently, the potential sample of subjects declined to 1,018 (27%) hospitalizations. Of the remaining hospitalizations, 46 and 972 were medical CCU and nonsurgical (medical) inpatients, respectively.

In line with the sampling plan, 130 (13.4%) medical ward hospitalizations were selected using a random number generator. As the ICU sample was smaller than anticipated, the convenience sample of all 46 hospitalizations was used.

Manual Chart Abstraction

Manual chart abstraction (n = 176) clarified physician/provider decision making (eg, some patients were not appropriate for thromboprophylaxis due to upcoming invasive procedures), medical history that could not be extracted by ICD-9 coding (eg, recent non-VHA admissions for medical conditions that were contraindications to prophylaxis), and anticoagulation dosing. These exclusions led to an additional 52 (29.5%) excluded hospitalizations. Reasons for manual exclusion included recent bleeding or at high risk for bleeding (18, 34.6%), incorrect classification as nonsurgical or elective admission (5, 9.6%), no diagnosis of lung disease (21, 40.4%), invasive procedures planned (4, 7.7%), treatment anticoagulant doses selected (4, 7.7%), or patient transferred to a non-VA medical facility due to acuity level (1, 1.9%). One patient was excluded for multiple reasons.

Baseline Demographics

The sample was an elderly, male (98%), white (79.8%) cohort (Table 1). No patients were aged < 40 years. Racial information was missing for 5.6% of the patients. The chief pulmonary diagnosis was COPD, and few patients had new onset, acute, severe respiratory disease (3.2%) prompting admission, because pneumonia was not included as a qualifying diagnosis. Median body mass index (BMI) was 26.31. The median LOS was 3.8 days for the overall cohort and 4.1 days for those receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, although for the latter group a larger proportion of patients were hospitalized for < 3 days. Renal function, according to endpoint definitions, was for using enoxaparin as the appropriate strategy for thromboprophylaxis for the majority (97.5%) of hospitalizations.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

Of those receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, heparin was prescribed most often (62.8%). One patient received both heparin and enoxaparin during a single hospitalization.

Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was more common in the medical CCU subgroup (80.6%) compared with the nonsurgical patient (56.9%). Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was used in 62.9% of patients (n = 124). However, the therapeutic appropriateness ratio was reduced to 58% of the entire sample (n = 124), because 6 patients of the cohort receiving thromboprophylaxis (n = 78) were prescribed suboptimal doses: Specifically, 1 patient was underdosed and 1 overdosed when prescribed enoxaparin (2, 2.6%). Four patients (5.1%) received underdoses of heparin, based on institutional guidance. For those prescribed pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, the VTE protected time period ratio was 82.8% (Table 2). Overall inpatient mortality rate was low (12, 9.7%). Most deceased patients were managed in the medical CCU (10, 83.3%) and did receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (10, 83.3%).

Discussion

This study demonstrated moderate rates of VTE pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, because 62.9% of nonsurgical patients with respiratory disease who were hospitalized for various reasons were prophylaxed with either SC heparin or enoxaparin. This rate represents active clinical decision making, because there was no indication to prescribe anticoagulation at therapeutic doses. As expected, pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was more common in the critical care subgroup (80.6%) compared with the nonsurgical patients (56.9%). Although the study did not meet the intended sample size for this subgroup analysis, results were statistically significant for location of care (P = .014) and may be beneficial for future study design by other investigators.

As early studies of nonsurgical and critical care patients document ≤ 40% of patients receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, this study’s performance seems better.7,12,21 Recently, VHA investigators Quraishi and colleagues seemed to document similar findings. Although 63% of medical patients at the Dayton VAMC in Ohio received appropriate pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, this value must be tempered by the proportion of subjects receiving therapeutic anticoagulation (5.4%).18

Similar to this study’s results, recent studies of nonveterans document pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis rates of 41% to 51.8%, 41% to 65.9%, and 74.6% to 89.9% in patients with respiratory disease, nonsurgical patients, and critical care patients, respectively. Although findings seem similar to this study’s results, adjustments in estimates again must be made, because these estimates included patients on therapeutic anticoagulation.12,14-16 This study’s results found that 58% of the patient cohort met the therapeutic appropriateness ratio, because they were administered pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis and received correct doses at indicated dosing intervals.

Because stringent exclusion criteria that minimized use of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in patients at risk for bleeding were applied, a higher rate of use was expected. This difference between expected and actual rates likely occurred because patient care is individualized and not all factors can be readily assessed in an observational study using retrospective data.

Additionally, for patients who remain ambulatory or have an invasive procedure, thromboprophylaxis may be appropriately delayed past the first 24-hour window of therapy or even temporarily interrupted. Subsequently, the measure of thromboprophylaxis initiation within the first 24 to 48 hours of admission was not elected. Instead, an alternative endpoint of VTE protected time period on thromboprophylaxis was selected. When thromboprophylaxis was used, the median period of protection was 83% of the time period hospitalized for this subgroup. Standardizing to a 7-day period, a VTE protected time period of 83% is coverage for 5.81 days. This would support the Joint Commission ORYX measure that allows for the receipt of thromboprophylaxis within 48 hours of admission to be counted as a success.6

Unfortunately, the authors did not assess whether mechanical thromboprophylaxis was provided to the remaining one-third of patients not receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. As a result, the complete data set is lacking, which would document whether the Joint Commission measure of ≥ 95% of the time was achieved. Therefore, the claim that TVHS is a top performing hospital for this ORYX measure cannot be made.

Although this study demonstrated a low mortality rate, this rate was not selected as a measure of interest, since one meta-analysis has demonstrated no mortality benefit from VTE thromboprophylaxis.4 Although in-hospital mortality may be an appropriate measure for critical care patients, most of the study patients did not meet this criterion.21 Last, mortality should be assessed no earlier than 30 days from admission.17 Subsequently, statistical assessment and conclusions from this measure are not relevant.

Limitations

A number of limitations hindered the generalizability of the results. This was an observational study using retrospectively collected data. The sample was narrowed to those with chronic respiratory disease, which has been less studied and typically examined in concert with acute processes, such as pneumonia. The demographic was primarily white males. The BMI of subjects enrolled in this study (26 kg/m2) was lower than the BMI of nonveteran subjects with COPD (28.6 kg/m2), nonveteran subjects with COPD and VTE (29 kg/m2), or veteran nonsurgical patients receiving thromboprophylaxis (29 kg/m2).18,34,35

The exclusion criteria resulted in a 73% reduction in the cohort and severely limited the number of medical critical care patients included. However, the problem of a small cohort was anticipated.

Other researchers conducting a prospective VHA thromboprophylaxis study found only 7.6% of veterans screened were eligible for enrollment, although 25% of subjects were anticipated by chart review. Two of the 3 primary reasons for trial exclusion were indication for therapeutic anticoagulation and contraindications to heparin (other than thrombocytopenia), and these were also primary reasons for exclusion in this study.30 Subsequently, the cohort appropriate for thromboprophylaxis in VHA seems relatively small.

Additionally, mobility is difficult to judge in a chart review. Day-to-day clinical assessments of mobility lead to individualization of care, including delayed initiation and timely termination of thromboprophylaxis. It is also possible that a significant portion of the patients had mechanical thromboprophylaxis, because they may have had an unrecognized risk factor for bleeding or patient preferences were considered. Last, some veterans may have classified as palliative care, and VTE prophylaxis may have been omitted for comfort care purposes.32