User login

Thyroid hormones predict psychotic depression in MDD patients

Thyroid dysfunction is common among major depressive disorder (MDD) patients, but its relationship with the psychotic depression (PD) subtype has not been well studied, wrote Pu Peng, of The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China, and colleagues.

Given the significant negative consequences of PD in MDD, including comorbid psychosis, suicidal attempts, and worse prognosis, more ways to identify PD risk factors in MDD are needed, they said. Previous research suggests a role for thyroid hormones in the pathophysiology of PD, but data on specific associations are limited, they noted.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the authors recruited 1,718 adults aged 18-60 years with MDD who were treated at a single center. The median age was 34 years, 66% were female, and 10% were identified with PD.

Clinical symptoms were identified using the positive subscale of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS-P), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA), and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD). The median PANSS-P score was 7. The researchers measured serum levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), anti-thyroglobulin (TgAb), and thyroid peroxidases antibody (TPOAb). Subclinical hyperthyroidism (SCH) was defined as TSH levels greater than 8.0 uIU/L and FT4 within normal values.

Overall, the prevalence of SCH, abnormal TgAb, TPOAb, FT3, and FT4 were 13%, 17%, 25%, <0.1%, and 0.3%, respectively. Serum TSH levels, TgAb levels, and TPOAb levels were significantly higher in PD patients than in non-PD patients. No differences appeared in FT3 and FT4 levels between the two groups.

In a multivariate analysis, subclinical hypothyroidism was associated with a ninefold increased risk of PD (odds ratio, 9.32) as were abnormal TPOAb (OR, 1.89) and abnormal TgAb (OR, 2.09).

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, and the inclusion of participants from only a single center in China, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted.

In addition, “It should be noted that the association between thyroid hormones and PD was small to moderate and the underlying mechanism remained unexplored,” they said. Other limitations include the use of only 17 of the 20 HAMD items and the lack of data on the relationship between anxiety and depressive features and thyroid dysfunction, they wrote.

More research is needed to confirm the findings in other populations, however; the results suggest that regular thyroid function tests may help with early detection of PD in MDD patients, they concluded.

The study was funded by the CAS Pioneer Hundred Talents Program and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Thyroid dysfunction is common among major depressive disorder (MDD) patients, but its relationship with the psychotic depression (PD) subtype has not been well studied, wrote Pu Peng, of The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China, and colleagues.

Given the significant negative consequences of PD in MDD, including comorbid psychosis, suicidal attempts, and worse prognosis, more ways to identify PD risk factors in MDD are needed, they said. Previous research suggests a role for thyroid hormones in the pathophysiology of PD, but data on specific associations are limited, they noted.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the authors recruited 1,718 adults aged 18-60 years with MDD who were treated at a single center. The median age was 34 years, 66% were female, and 10% were identified with PD.

Clinical symptoms were identified using the positive subscale of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS-P), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA), and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD). The median PANSS-P score was 7. The researchers measured serum levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), anti-thyroglobulin (TgAb), and thyroid peroxidases antibody (TPOAb). Subclinical hyperthyroidism (SCH) was defined as TSH levels greater than 8.0 uIU/L and FT4 within normal values.

Overall, the prevalence of SCH, abnormal TgAb, TPOAb, FT3, and FT4 were 13%, 17%, 25%, <0.1%, and 0.3%, respectively. Serum TSH levels, TgAb levels, and TPOAb levels were significantly higher in PD patients than in non-PD patients. No differences appeared in FT3 and FT4 levels between the two groups.

In a multivariate analysis, subclinical hypothyroidism was associated with a ninefold increased risk of PD (odds ratio, 9.32) as were abnormal TPOAb (OR, 1.89) and abnormal TgAb (OR, 2.09).

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, and the inclusion of participants from only a single center in China, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted.

In addition, “It should be noted that the association between thyroid hormones and PD was small to moderate and the underlying mechanism remained unexplored,” they said. Other limitations include the use of only 17 of the 20 HAMD items and the lack of data on the relationship between anxiety and depressive features and thyroid dysfunction, they wrote.

More research is needed to confirm the findings in other populations, however; the results suggest that regular thyroid function tests may help with early detection of PD in MDD patients, they concluded.

The study was funded by the CAS Pioneer Hundred Talents Program and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Thyroid dysfunction is common among major depressive disorder (MDD) patients, but its relationship with the psychotic depression (PD) subtype has not been well studied, wrote Pu Peng, of The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China, and colleagues.

Given the significant negative consequences of PD in MDD, including comorbid psychosis, suicidal attempts, and worse prognosis, more ways to identify PD risk factors in MDD are needed, they said. Previous research suggests a role for thyroid hormones in the pathophysiology of PD, but data on specific associations are limited, they noted.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the authors recruited 1,718 adults aged 18-60 years with MDD who were treated at a single center. The median age was 34 years, 66% were female, and 10% were identified with PD.

Clinical symptoms were identified using the positive subscale of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS-P), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA), and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD). The median PANSS-P score was 7. The researchers measured serum levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), anti-thyroglobulin (TgAb), and thyroid peroxidases antibody (TPOAb). Subclinical hyperthyroidism (SCH) was defined as TSH levels greater than 8.0 uIU/L and FT4 within normal values.

Overall, the prevalence of SCH, abnormal TgAb, TPOAb, FT3, and FT4 were 13%, 17%, 25%, <0.1%, and 0.3%, respectively. Serum TSH levels, TgAb levels, and TPOAb levels were significantly higher in PD patients than in non-PD patients. No differences appeared in FT3 and FT4 levels between the two groups.

In a multivariate analysis, subclinical hypothyroidism was associated with a ninefold increased risk of PD (odds ratio, 9.32) as were abnormal TPOAb (OR, 1.89) and abnormal TgAb (OR, 2.09).

The findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design, and the inclusion of participants from only a single center in China, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted.

In addition, “It should be noted that the association between thyroid hormones and PD was small to moderate and the underlying mechanism remained unexplored,” they said. Other limitations include the use of only 17 of the 20 HAMD items and the lack of data on the relationship between anxiety and depressive features and thyroid dysfunction, they wrote.

More research is needed to confirm the findings in other populations, however; the results suggest that regular thyroid function tests may help with early detection of PD in MDD patients, they concluded.

The study was funded by the CAS Pioneer Hundred Talents Program and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

Beyond the psychedelic effect: Ayahuasca as antidepressant

Ayahuasca is a psychoactive beverage that has long been used by indigenous people in South America in religious ceremonies and tribal rituals. In recent years, the beverage has emerged as a strong candidate for implementation into psychiatric care, particularly for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Studies have shown that taking ayahuasca is associated with an improvement of depressive symptoms. In a study published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, a team of researchers from Brazil’s Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) describe an experimental ayahuasca session. They found that

Nicole Leite Galvão-Coelho, PhD, professor of physiology and behavior at UFRN, is one of the authors of that study. She is also a researcher at the NICM Health Research Institute at Western Sydney University. Dr. Galvão-Coelho spoke with this news organization about her team’s work.

A total of 72 people volunteered to participate in the study. There were 28 patients, all of whom were experiencing a moderate to severe depressive episode at screening. In addition, they had been diagnosed with treatment-resistant depression and had not achieved remission after at least two treatments with antidepressant medications of different classes. These patients had been experiencing depression for about 10.71 ± 9.72 years. The other 44 volunteers were healthy control participants. All the participants – both in the patient group and the control group – were naive to any classic serotonergic psychedelic such as ayahuasca.

In each group, half received ayahuasca, and the other half received a placebo. The dosing session was performed at UFRN’s Onofre Lopes University Hospital and lasted about 8 hours.

All volunteers underwent a full clinical mental health evaluation and medical history. Blood and saliva samples were collected at baseline, approximately 4 hours before the dosing session, and 2 days after the dosing session. During the dosing session, saliva samples were collected at 1 hour 40 minutes, 2 hours 40 minutes, and 4 hours after ayahuasca intake.

The study showed that some acute measures assessed during ayahuasca dosing moderated the improvements in major depressive disorder (MDD) biomarkers 2 days after the session in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Larger acute decreases of depressive symptoms moderated higher levels of SC in those patients, while lower acute changes in SC levels were related to higher BDNF levels in patients with a larger clinical response.

The UFRN research team has been investigating the potential antidepressant effects of ayahuasca for approximately 12 years. According to Dr. Galvão-Coelho, the work reported in the most recent article – one in a series of articles that they wrote – provides a step forward as a pioneering psychedelic field study assessing the biological changes of MDD molecular biomarkers. “There have indeed been observational studies and open-label clinical studies. We were the first team, though, to conduct placebo-controlled clinical studies with ayahuasca in patients with treatment-resistant depression,” she explained. She noted that the work was carried out in partnership with Dráulio Barros de Araújo, PhD, a professor at UFRN’s Brain Institute, as well as with a multidisciplinary team of researchers in Brazil and Australia.

Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that in an earlier study, the UFRN researchers observed that a single dose of ayahuasca led to long-lasting behavioral and physiologic improvements in an animal (marmoset) model. In another study, there was improvement in depression severity for patients with treatment-resistant depression 7 days after taking ayahuasca.

As for biomarkers, Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that there is a long history of research on cortisol (the “stress hormone”) with respect to patients with depressive symptoms, given the link between chronic stress and depressive disorders. “In our patients with treatment-resistant depression, we found that before being dosed with ayahuasca, they presented hypocortisolemia,” she said. She noted that low levels of cortisol are as harmful to one’s health as high levels. According to her, the goal should be to sustain moderate levels. “In other studies, we’ve shown that patients with more recent, less chronic depression have high cortisol levels, but after a little while, the [adrenal] glands get overworked, which seems to lead to a situation where they’re not producing all those important hormones. That’s why chronic conditions of depression are marked by low levels of cortisol. But,” she pointed out, “after patients with treatment-resistant depression take ayahuasca, we no longer see hypocortisolemia.”

Another biomarker analyzed by the research team, the protein BDNF, has the capacity to induce neuroplasticity. Indeed, Dr. Galvão-Coelho mentioned a theory that antidepressant drugs work when they increase levels of this protein, which would stimulate new connections in the brain.

Because several earlier studies indicated that other psychedelic substances would promote an increase in BDNF, the UFRN researchers decided to explore the potential effects of ayahuasca on this biomarker. “We observed that there was actually an increase in serum BDNF, and the patients who showed the greatest increase [of this marker] had a more significant reduction in depressive symptoms,” Dr. Galvão-Coelho explained.

Considering all the previous findings, the team wondered whether acute parameters recorded during an ayahuasca dosing session could in some way modulate the responses of certain key MDD molecular biomarkers. They then conducted their study that was published last December.

Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that the results of that study show that acute emotional and physiologic effects of ayahuasca seem to be relevant to an improvement of key MDD molecular biomarkers (namely, SC and BDNF). She also noted that the results revealed that larger reductions of depressive symptoms during the dosing session significantly moderated higher levels of SC in patients 2 days after ayahuasca intake. In the case of BDNF, the positive correlation between clinical response and day-2 BDNF levels only occurred for patients who experienced small increases of cortisol during the experimental session. These were individuals who did not have such an intense response to stress and who felt more at ease during the session.

The findings showed which factors that arise during the psychedelic state induced by ayahuasca modulate biological response associated with the antidepressant action of these substances in patients with major depression. “We realized, for example, that to bring about a sense of comfort and trust, to get a good acute response, the dosing session had to be extremely well thought out. That seemed to be relevant to the results on the other days,” Dr. Galvão-Coelho explained.

For her, there was another takeaway from the research: New antidepressant treatments should be complemented by a more comprehensive view of the case at hand. “We have to think about the patient’s overall improvement – including, therefore, the improvement of biomarkers – and not focus solely on the clinical symptoms.”

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese Edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ayahuasca is a psychoactive beverage that has long been used by indigenous people in South America in religious ceremonies and tribal rituals. In recent years, the beverage has emerged as a strong candidate for implementation into psychiatric care, particularly for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Studies have shown that taking ayahuasca is associated with an improvement of depressive symptoms. In a study published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, a team of researchers from Brazil’s Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) describe an experimental ayahuasca session. They found that

Nicole Leite Galvão-Coelho, PhD, professor of physiology and behavior at UFRN, is one of the authors of that study. She is also a researcher at the NICM Health Research Institute at Western Sydney University. Dr. Galvão-Coelho spoke with this news organization about her team’s work.

A total of 72 people volunteered to participate in the study. There were 28 patients, all of whom were experiencing a moderate to severe depressive episode at screening. In addition, they had been diagnosed with treatment-resistant depression and had not achieved remission after at least two treatments with antidepressant medications of different classes. These patients had been experiencing depression for about 10.71 ± 9.72 years. The other 44 volunteers were healthy control participants. All the participants – both in the patient group and the control group – were naive to any classic serotonergic psychedelic such as ayahuasca.

In each group, half received ayahuasca, and the other half received a placebo. The dosing session was performed at UFRN’s Onofre Lopes University Hospital and lasted about 8 hours.

All volunteers underwent a full clinical mental health evaluation and medical history. Blood and saliva samples were collected at baseline, approximately 4 hours before the dosing session, and 2 days after the dosing session. During the dosing session, saliva samples were collected at 1 hour 40 minutes, 2 hours 40 minutes, and 4 hours after ayahuasca intake.

The study showed that some acute measures assessed during ayahuasca dosing moderated the improvements in major depressive disorder (MDD) biomarkers 2 days after the session in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Larger acute decreases of depressive symptoms moderated higher levels of SC in those patients, while lower acute changes in SC levels were related to higher BDNF levels in patients with a larger clinical response.

The UFRN research team has been investigating the potential antidepressant effects of ayahuasca for approximately 12 years. According to Dr. Galvão-Coelho, the work reported in the most recent article – one in a series of articles that they wrote – provides a step forward as a pioneering psychedelic field study assessing the biological changes of MDD molecular biomarkers. “There have indeed been observational studies and open-label clinical studies. We were the first team, though, to conduct placebo-controlled clinical studies with ayahuasca in patients with treatment-resistant depression,” she explained. She noted that the work was carried out in partnership with Dráulio Barros de Araújo, PhD, a professor at UFRN’s Brain Institute, as well as with a multidisciplinary team of researchers in Brazil and Australia.

Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that in an earlier study, the UFRN researchers observed that a single dose of ayahuasca led to long-lasting behavioral and physiologic improvements in an animal (marmoset) model. In another study, there was improvement in depression severity for patients with treatment-resistant depression 7 days after taking ayahuasca.

As for biomarkers, Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that there is a long history of research on cortisol (the “stress hormone”) with respect to patients with depressive symptoms, given the link between chronic stress and depressive disorders. “In our patients with treatment-resistant depression, we found that before being dosed with ayahuasca, they presented hypocortisolemia,” she said. She noted that low levels of cortisol are as harmful to one’s health as high levels. According to her, the goal should be to sustain moderate levels. “In other studies, we’ve shown that patients with more recent, less chronic depression have high cortisol levels, but after a little while, the [adrenal] glands get overworked, which seems to lead to a situation where they’re not producing all those important hormones. That’s why chronic conditions of depression are marked by low levels of cortisol. But,” she pointed out, “after patients with treatment-resistant depression take ayahuasca, we no longer see hypocortisolemia.”

Another biomarker analyzed by the research team, the protein BDNF, has the capacity to induce neuroplasticity. Indeed, Dr. Galvão-Coelho mentioned a theory that antidepressant drugs work when they increase levels of this protein, which would stimulate new connections in the brain.

Because several earlier studies indicated that other psychedelic substances would promote an increase in BDNF, the UFRN researchers decided to explore the potential effects of ayahuasca on this biomarker. “We observed that there was actually an increase in serum BDNF, and the patients who showed the greatest increase [of this marker] had a more significant reduction in depressive symptoms,” Dr. Galvão-Coelho explained.

Considering all the previous findings, the team wondered whether acute parameters recorded during an ayahuasca dosing session could in some way modulate the responses of certain key MDD molecular biomarkers. They then conducted their study that was published last December.

Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that the results of that study show that acute emotional and physiologic effects of ayahuasca seem to be relevant to an improvement of key MDD molecular biomarkers (namely, SC and BDNF). She also noted that the results revealed that larger reductions of depressive symptoms during the dosing session significantly moderated higher levels of SC in patients 2 days after ayahuasca intake. In the case of BDNF, the positive correlation between clinical response and day-2 BDNF levels only occurred for patients who experienced small increases of cortisol during the experimental session. These were individuals who did not have such an intense response to stress and who felt more at ease during the session.

The findings showed which factors that arise during the psychedelic state induced by ayahuasca modulate biological response associated with the antidepressant action of these substances in patients with major depression. “We realized, for example, that to bring about a sense of comfort and trust, to get a good acute response, the dosing session had to be extremely well thought out. That seemed to be relevant to the results on the other days,” Dr. Galvão-Coelho explained.

For her, there was another takeaway from the research: New antidepressant treatments should be complemented by a more comprehensive view of the case at hand. “We have to think about the patient’s overall improvement – including, therefore, the improvement of biomarkers – and not focus solely on the clinical symptoms.”

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese Edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ayahuasca is a psychoactive beverage that has long been used by indigenous people in South America in religious ceremonies and tribal rituals. In recent years, the beverage has emerged as a strong candidate for implementation into psychiatric care, particularly for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Studies have shown that taking ayahuasca is associated with an improvement of depressive symptoms. In a study published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, a team of researchers from Brazil’s Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) describe an experimental ayahuasca session. They found that

Nicole Leite Galvão-Coelho, PhD, professor of physiology and behavior at UFRN, is one of the authors of that study. She is also a researcher at the NICM Health Research Institute at Western Sydney University. Dr. Galvão-Coelho spoke with this news organization about her team’s work.

A total of 72 people volunteered to participate in the study. There were 28 patients, all of whom were experiencing a moderate to severe depressive episode at screening. In addition, they had been diagnosed with treatment-resistant depression and had not achieved remission after at least two treatments with antidepressant medications of different classes. These patients had been experiencing depression for about 10.71 ± 9.72 years. The other 44 volunteers were healthy control participants. All the participants – both in the patient group and the control group – were naive to any classic serotonergic psychedelic such as ayahuasca.

In each group, half received ayahuasca, and the other half received a placebo. The dosing session was performed at UFRN’s Onofre Lopes University Hospital and lasted about 8 hours.

All volunteers underwent a full clinical mental health evaluation and medical history. Blood and saliva samples were collected at baseline, approximately 4 hours before the dosing session, and 2 days after the dosing session. During the dosing session, saliva samples were collected at 1 hour 40 minutes, 2 hours 40 minutes, and 4 hours after ayahuasca intake.

The study showed that some acute measures assessed during ayahuasca dosing moderated the improvements in major depressive disorder (MDD) biomarkers 2 days after the session in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Larger acute decreases of depressive symptoms moderated higher levels of SC in those patients, while lower acute changes in SC levels were related to higher BDNF levels in patients with a larger clinical response.

The UFRN research team has been investigating the potential antidepressant effects of ayahuasca for approximately 12 years. According to Dr. Galvão-Coelho, the work reported in the most recent article – one in a series of articles that they wrote – provides a step forward as a pioneering psychedelic field study assessing the biological changes of MDD molecular biomarkers. “There have indeed been observational studies and open-label clinical studies. We were the first team, though, to conduct placebo-controlled clinical studies with ayahuasca in patients with treatment-resistant depression,” she explained. She noted that the work was carried out in partnership with Dráulio Barros de Araújo, PhD, a professor at UFRN’s Brain Institute, as well as with a multidisciplinary team of researchers in Brazil and Australia.

Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that in an earlier study, the UFRN researchers observed that a single dose of ayahuasca led to long-lasting behavioral and physiologic improvements in an animal (marmoset) model. In another study, there was improvement in depression severity for patients with treatment-resistant depression 7 days after taking ayahuasca.

As for biomarkers, Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that there is a long history of research on cortisol (the “stress hormone”) with respect to patients with depressive symptoms, given the link between chronic stress and depressive disorders. “In our patients with treatment-resistant depression, we found that before being dosed with ayahuasca, they presented hypocortisolemia,” she said. She noted that low levels of cortisol are as harmful to one’s health as high levels. According to her, the goal should be to sustain moderate levels. “In other studies, we’ve shown that patients with more recent, less chronic depression have high cortisol levels, but after a little while, the [adrenal] glands get overworked, which seems to lead to a situation where they’re not producing all those important hormones. That’s why chronic conditions of depression are marked by low levels of cortisol. But,” she pointed out, “after patients with treatment-resistant depression take ayahuasca, we no longer see hypocortisolemia.”

Another biomarker analyzed by the research team, the protein BDNF, has the capacity to induce neuroplasticity. Indeed, Dr. Galvão-Coelho mentioned a theory that antidepressant drugs work when they increase levels of this protein, which would stimulate new connections in the brain.

Because several earlier studies indicated that other psychedelic substances would promote an increase in BDNF, the UFRN researchers decided to explore the potential effects of ayahuasca on this biomarker. “We observed that there was actually an increase in serum BDNF, and the patients who showed the greatest increase [of this marker] had a more significant reduction in depressive symptoms,” Dr. Galvão-Coelho explained.

Considering all the previous findings, the team wondered whether acute parameters recorded during an ayahuasca dosing session could in some way modulate the responses of certain key MDD molecular biomarkers. They then conducted their study that was published last December.

Dr. Galvão-Coelho said that the results of that study show that acute emotional and physiologic effects of ayahuasca seem to be relevant to an improvement of key MDD molecular biomarkers (namely, SC and BDNF). She also noted that the results revealed that larger reductions of depressive symptoms during the dosing session significantly moderated higher levels of SC in patients 2 days after ayahuasca intake. In the case of BDNF, the positive correlation between clinical response and day-2 BDNF levels only occurred for patients who experienced small increases of cortisol during the experimental session. These were individuals who did not have such an intense response to stress and who felt more at ease during the session.

The findings showed which factors that arise during the psychedelic state induced by ayahuasca modulate biological response associated with the antidepressant action of these substances in patients with major depression. “We realized, for example, that to bring about a sense of comfort and trust, to get a good acute response, the dosing session had to be extremely well thought out. That seemed to be relevant to the results on the other days,” Dr. Galvão-Coelho explained.

For her, there was another takeaway from the research: New antidepressant treatments should be complemented by a more comprehensive view of the case at hand. “We have to think about the patient’s overall improvement – including, therefore, the improvement of biomarkers – and not focus solely on the clinical symptoms.”

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese Edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN PSYCHIATRY

Statin disappoints for treatment-resistant depression

The randomized clinical trial findings contradict earlier, smaller studies in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) that suggested statins may reduce symptoms.

“Given the promising results from preliminary trials of statins in MDD, I was surprised that simvastatin did not separate from placebo in our trial,” lead author M. Ishrat Husain, MBBS, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and scientific head of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“I believe that our findings suggest that statins are not effective augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant depression,” Dr. Husain said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Disappointing results

The double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was conducted in five centers in Pakistan and included 150 patients with major depressive episode whose symptoms did not improve after treatment with at least two antidepressants.

In addition to their prescribed antidepressants, participants received 20 mg/day of simvastatin (n = 77) or placebo (n = 73).

At 12 weeks, both groups reported improvements in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total scores, but there was no significant difference between groups. The estimated mean difference for simvastatin vs. placebo was −0.61 (P = .7).

Researchers found similar results when they compared scores from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.

“Much like several other studies in mood disorders, our study results were impacted by a large placebo response,” Dr. Husain said.

The lack of inclusion of any participants under the age of 18 and the single-country cohort were limitations of the trial. Although it is possible that could have affected the outcome, Dr. Husain said it isn’t likely.

It is also unlikely that a different statin would yield different results, he added.

“Simvastatin was selected as it is believed to be most brain penetrant of the statins given its lipophilicity,” Dr. Husain said. “Clinical trials of other statins in major depressive disorder in other settings and populations have also been congruent with our results.”

The study was funded by NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London. Dr. Husain reports having received grants from Compass Pathways, holds stock options in Mindset, and previously served on the Board of Trustees of the Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning. Disclosures for the other investigators are fully listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The randomized clinical trial findings contradict earlier, smaller studies in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) that suggested statins may reduce symptoms.

“Given the promising results from preliminary trials of statins in MDD, I was surprised that simvastatin did not separate from placebo in our trial,” lead author M. Ishrat Husain, MBBS, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and scientific head of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“I believe that our findings suggest that statins are not effective augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant depression,” Dr. Husain said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Disappointing results

The double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was conducted in five centers in Pakistan and included 150 patients with major depressive episode whose symptoms did not improve after treatment with at least two antidepressants.

In addition to their prescribed antidepressants, participants received 20 mg/day of simvastatin (n = 77) or placebo (n = 73).

At 12 weeks, both groups reported improvements in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total scores, but there was no significant difference between groups. The estimated mean difference for simvastatin vs. placebo was −0.61 (P = .7).

Researchers found similar results when they compared scores from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.

“Much like several other studies in mood disorders, our study results were impacted by a large placebo response,” Dr. Husain said.

The lack of inclusion of any participants under the age of 18 and the single-country cohort were limitations of the trial. Although it is possible that could have affected the outcome, Dr. Husain said it isn’t likely.

It is also unlikely that a different statin would yield different results, he added.

“Simvastatin was selected as it is believed to be most brain penetrant of the statins given its lipophilicity,” Dr. Husain said. “Clinical trials of other statins in major depressive disorder in other settings and populations have also been congruent with our results.”

The study was funded by NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London. Dr. Husain reports having received grants from Compass Pathways, holds stock options in Mindset, and previously served on the Board of Trustees of the Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning. Disclosures for the other investigators are fully listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The randomized clinical trial findings contradict earlier, smaller studies in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) that suggested statins may reduce symptoms.

“Given the promising results from preliminary trials of statins in MDD, I was surprised that simvastatin did not separate from placebo in our trial,” lead author M. Ishrat Husain, MBBS, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and scientific head of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“I believe that our findings suggest that statins are not effective augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant depression,” Dr. Husain said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Disappointing results

The double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was conducted in five centers in Pakistan and included 150 patients with major depressive episode whose symptoms did not improve after treatment with at least two antidepressants.

In addition to their prescribed antidepressants, participants received 20 mg/day of simvastatin (n = 77) or placebo (n = 73).

At 12 weeks, both groups reported improvements in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total scores, but there was no significant difference between groups. The estimated mean difference for simvastatin vs. placebo was −0.61 (P = .7).

Researchers found similar results when they compared scores from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.

“Much like several other studies in mood disorders, our study results were impacted by a large placebo response,” Dr. Husain said.

The lack of inclusion of any participants under the age of 18 and the single-country cohort were limitations of the trial. Although it is possible that could have affected the outcome, Dr. Husain said it isn’t likely.

It is also unlikely that a different statin would yield different results, he added.

“Simvastatin was selected as it is believed to be most brain penetrant of the statins given its lipophilicity,” Dr. Husain said. “Clinical trials of other statins in major depressive disorder in other settings and populations have also been congruent with our results.”

The study was funded by NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London. Dr. Husain reports having received grants from Compass Pathways, holds stock options in Mindset, and previously served on the Board of Trustees of the Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning. Disclosures for the other investigators are fully listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Iron deficiency in psychiatric patients

Nutritional deficiencies are one of the many causes of or contributors to symptoms in patients with psychiatric disorders. In this article, we discuss the prevalence of iron deficiency and its link to poor mental health, and how proper treatment may improve psychiatric symptoms. We also offer suggestions for how and when to test for and treat iron deficiency in psychiatric patients.

A common condition

Iron deficiency is the most common mineral deficiency in the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 25% of the global population is anemic and nearly one-half of those cases are the result of iron deficiency.1 While the WHO has published guidelines defining iron deficiency as it relates to ferritin levels (<15 ug/L in adults and <12 ug/L in children), this estimate might be low.2,3 Mei et al2 found that hemoglobin and soluble transferrin receptors can be used to determine iron-deficient erythropoiesis, which indicates a physiological definition of iron deficiency. According to a study of children and nonpregnant women by Mei et al,2 children with ferritin levels <20 ug/L and women with ferritin levels <25 ug/L should be considered iron-deficient. If replicated, this study suggests the prevalence of iron deficiency is higher than currently estimated.2 Overall, an estimated 1.2 billion people worldwide have iron-deficiency anemia.4 Additionally, patients can be iron deficient without being anemic, a condition thought to be at least twice as common.4

Essential for brain function

Research shows the importance of iron to proper brain function.5 Iron deficiency in pregnant women is associated with significant neuropsychological impairments in neonates. Rodent studies have demonstrated the importance of iron and the effects of iron deficiency on the hippocampus, corpus striatum, and production of monoamines.5 Specifically, iron is a necessary cofactor in the enzymes tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase, which produce serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. In rodent studies, monoamine deficits secondary to iron deficiency persist into adulthood even with iron supplementation, which highlights the importance of preventing iron deficiency during pregnancy and early life.5 While most research has focused on the impact of iron deficiency in infancy and early childhood, iron deficiency has an ongoing impact into adulthood, even if treated.6

Iron deficiency and psychiatric symptoms

Current research suggests an association between iron deficiency or low ferritin levels and psychiatric disorders, specifically depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. In a web survey of 11,876 adults, Hidese et al7 found an association between a self-reported history of iron deficiency anemia and a self-reported history of depression. Another study of 528 municipal employees found an association between low serum ferritin concentrations and a high prevalence of depressive symptoms among men; no statistically significant association was detected in women.8 In an analysis of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database from 2000 to 2012, Lee et al9 found a statistically significant increased risk of anxiety disorders, depression, sleep disorders, and psychotic disorders in patients with iron deficiency anemia after controlling for multiple confounders. Xu et al10 used quantitative susceptibility mapping to assess the iron status in certain regions of the brain of 30 patients with first-episode psychosis. They found lower levels of iron in the bilateral substantia nigra, left red nucleus, and left thalamus compared to healthy controls.10 Kim et al11 found an association between iron deficiency and more severe negative symptoms in 121 patients with first-episode psychosis, which supports the hypothesis that iron deficiency may alter dopamine transmission in the brain.

Iron deficiency has been associated with psychopathology across the lifespan. In a population-based study in Taiwan, Chen et al12 found an association between iron deficiency anemia and psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents, including mood disorders, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and developmental disorders. At the other end of the age spectrum, in a survey of 1,875 older adults in England, Stewart et al13 found an association between low ferritin levels (<45 ng/mL) and depressive symptoms after adjusting for demographic factors and overall health status.

In addition to specific psychiatric disorders and symptoms, iron deficiency is often associated with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue.14 Fatigue is a symptom of numerous psychiatric disorders and is included in the DSM diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.15

Iron supplementation might improve psychiatric symptoms

Some evidence suggests that using iron supplementation to treat iron deficiency can improve psychiatric symptoms. In a 2013 systematic literature review of 10 studies, Greig et al16 found a link between low iron status and poor cognition, poor mental health scores, and fatigue among women of childbearing age. In this review, 7 studies demonstrated improvement in cognition and 3 demonstrated improvement in mental health with iron supplementation.16 In a 2021 prospective study, 19 children and adolescents age 6 to 15 who had serum ferritin levels <30 ng/mL were treated with oral iron supplementation for 12 weeks.17 Participants showed significant improvements in sleep quality, depressive symptoms, and general mood as assessed via the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaires, respectively.17 A randomized controlled trial of 219 female soldiers who were given iron supplementation or placebo for 8 weeks during basic combat training found that compared to placebo, iron supplementation led to improvements in mood as measured by the POMS questionnaire.18 Lastly, in a 2016 observational study of 412 adult psychiatric patients, Kassir19 found most patients (81%) had iron deficiency, defined as a transferrin saturation coefficient <30% or serum ferritin <100 ng/mL. Although these cutoffs are not considered standard and thus may have overrepresented the percentage of patients considered iron-deficient, more than one-half of patients considered iron-deficient in this study experienced a reduction or elimination of psychiatric symptoms following treatment with iron supplementation and/or psychotropic medications.19

Continue to: Individuals with iron deficiency...

Individuals with iron deficiency without anemia also may see improvement in psychiatric symptoms with iron treatment. In a 2018 systematic review, Houston et al20 evaluated iron supplementation in 1,170 adults who were iron-deficient but not anemic. They found that in these patients, fatigue significantly improved but physical capacity did not.20 Additionally, 2 other studies found iron treatment improved fatigue in nonanemic women.21,22 In a 2016 systematic review, Pratt et al23 concluded, “There is emerging evidence that … nonanemic iron deficiency … is a disease in its own right, deserving of further research in the development of strategies for detection and treatment.” Al-Naseem et al24 suggested severity distinguishes iron deficiency with and without anemia.

Your role in assessing and treating iron deficiency

Testing for and treating iron deficiency generally is not a part of routine psychiatric practice. This might be due to apathy given the pervasiveness of iron deficiency, a belief that iron deficiency should be managed by primary care physicians, or a lack of familiarity with how to treat it and the benefits of such treatment for psychiatric patients. However, assessing for and treating iron deficiency in psychiatric patients is important, especially for individuals who are highly susceptible to inadequate iron levels. People at risk for iron deficiency include pregnant women, infants, young children, women with heavy menstrual bleeding, frequent blood donors, patients with cancer, individuals who have gastrointestinal (GI) surgeries or disorders, and those with heart failure.25

Assessment. Iron status can be assessed through an iron studies panel. Because a patient can have iron deficiency without anemia, a complete blood count (CBC) alone does not suffice.26 The iron panel includes serum iron, serum ferritin, serum transferrin or total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and calculated transferrin saturation (TSAT), which is the ratio of serum iron to TIBC.

Iron deficiency is diagnosed if ferritin is <30 ng/mL, regardless of the hemoglobin concentration or underlying condition, and confirmed by a low TSAT.26 In most guidelines, the cutoff value for TSAT for iron deficiency is <20%. Because the TSAT can be influenced by iron supplements or iron-rich foods, wait several hours to obtain blood after a patient takes an oral iron supplement or eats iron-rich foods. If desired, clinicians can use either ferritin or TSAT alone to diagnose iron deficiency. However, because ferritin can be falsely normal in inflammatory conditions such as obesity and infection, a TSAT may be needed to confirm iron deficiency if there is a high clinical suspicion despite a normal ferritin level.26

Treatment. If iron deficiency is confirmed, instruct your patient to follow up with their primary care physician or the appropriate specialist to evaluate for any underlying etiologies.

Continue to: Iron deficiency should be treated...

Iron deficiency should be treated with supplementation because diet alone is insufficient for replenishing iron stores. Iron replacement can be oral or IV. Oral replacement is effective, safe, inexpensive, easy to obtain, and easy to administer.27 Oral replacement is recommended for adults whose anemia is not severe or who do not have a comorbid condition such as pregnancy, inflammatory bowel conditions, gastric surgery, or chronic kidney disease. When anemia is severe or a patient has one of these comorbid conditions, IV is the preferred method of replacement.27 In these cases, defer treatment to the patient’s primary care physician or specialist.

There are no clear recommendations on the amount of iron per dose to prescribe.27 The maximum amount of oral iron that can be absorbed is approximately 25 mg/d of elemental iron. A 325 mg ferrous sulfate tablet contains 65 mg of elemental iron, of which approximately 25 mg is absorbed and utilized.27

Emerging evidence suggests that excessive iron dosing may reduce iron absorption and increase adverse effects. In a study of 54 nonanemic young women with iron deficiency who were given iron supplementation, Moretti et al28 found that a large oral dose of iron taken in the morning increased hepcidin, which decreased the absorption of iron taken later for up to 48 hours. They found that 40 to 80 mg of elemental iron given on alternate days may maximize the fractional iron absorbed, increase dosage efficacy, reduce GI exposure to unabsorbed iron, and improve patients’ ability to tolerate iron supplementation.28

Adverse effects from iron supplements occur in up to 70% of patients.27 These can include metallic taste, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, diarrhea, epigastric pain, constipation, and dark stools.27 Using a liquid form may help reduce adverse effects because it can be more easily titrated.27 Tell patients to avoid enteric-coated or sustained-release iron capsules because these are poorly absorbed. Be cautious when prescribing iron supplementation to older adults because these patients tend to have more adverse effects, especially constipation, as well as reduced absorption, and may ultimately need IV treatment. Iron should not be taken with food, calcium supplements, antacids, coffee, tea, or milk.27

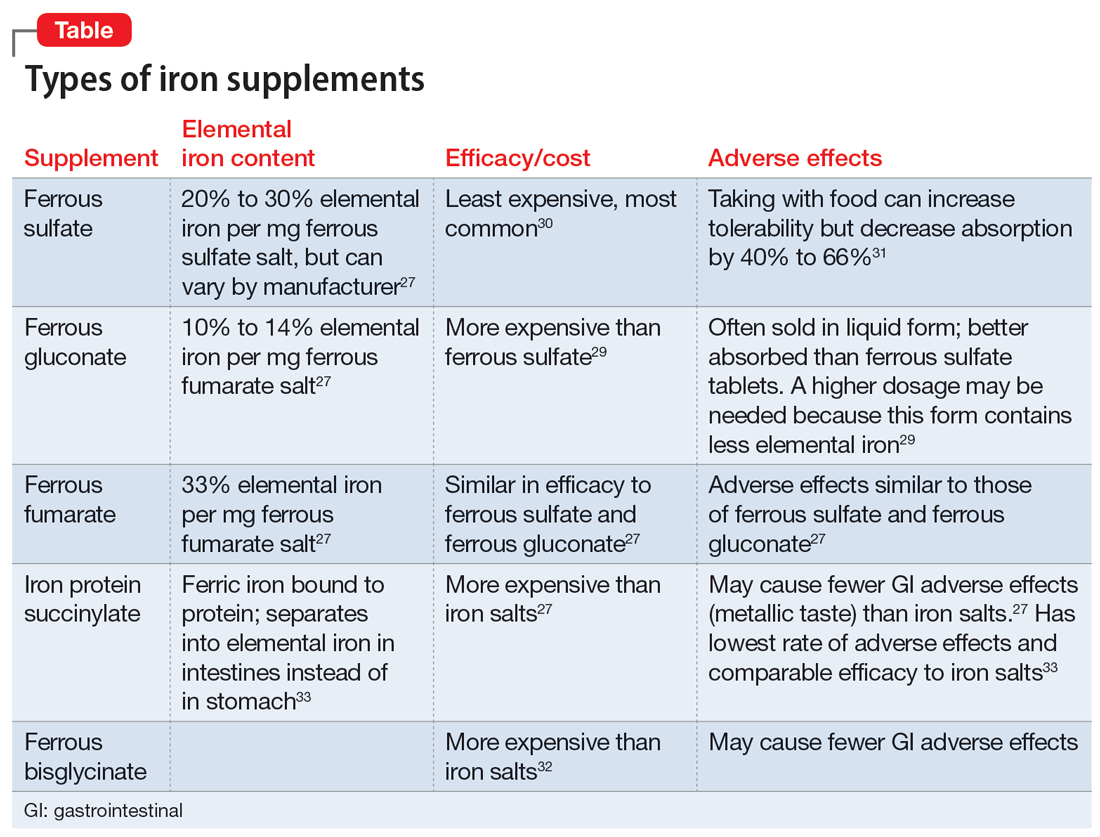

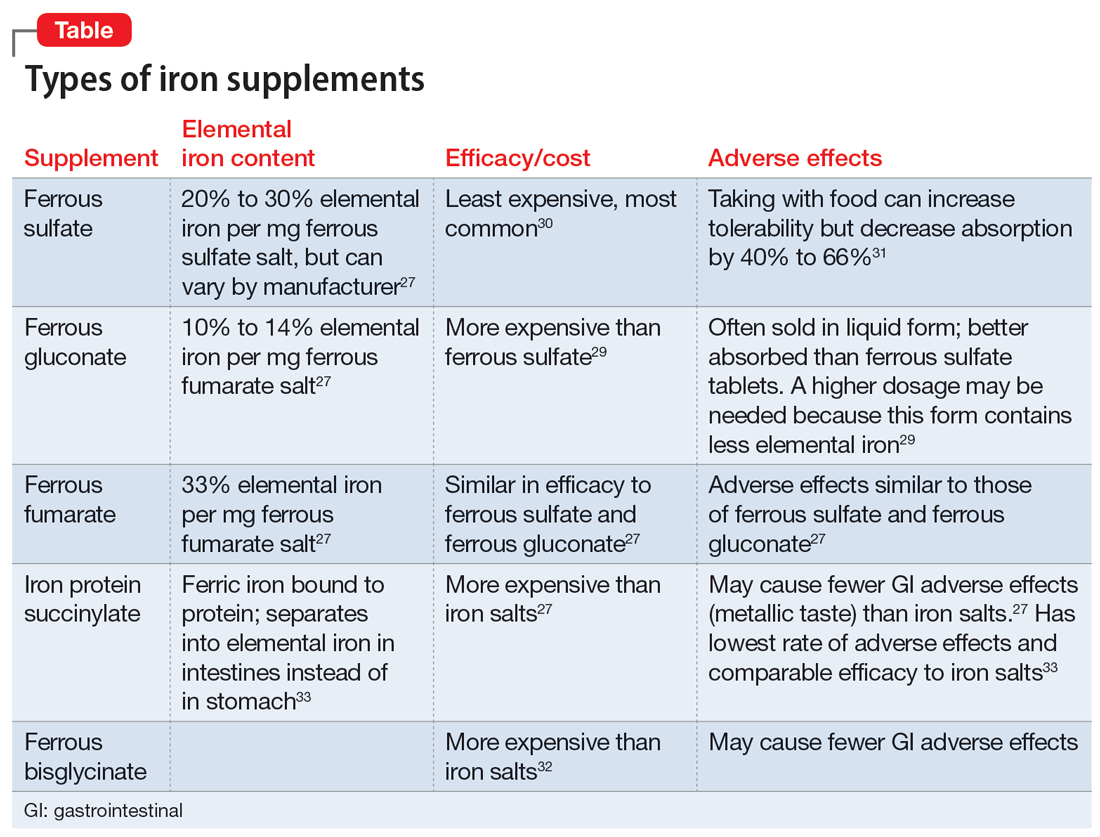

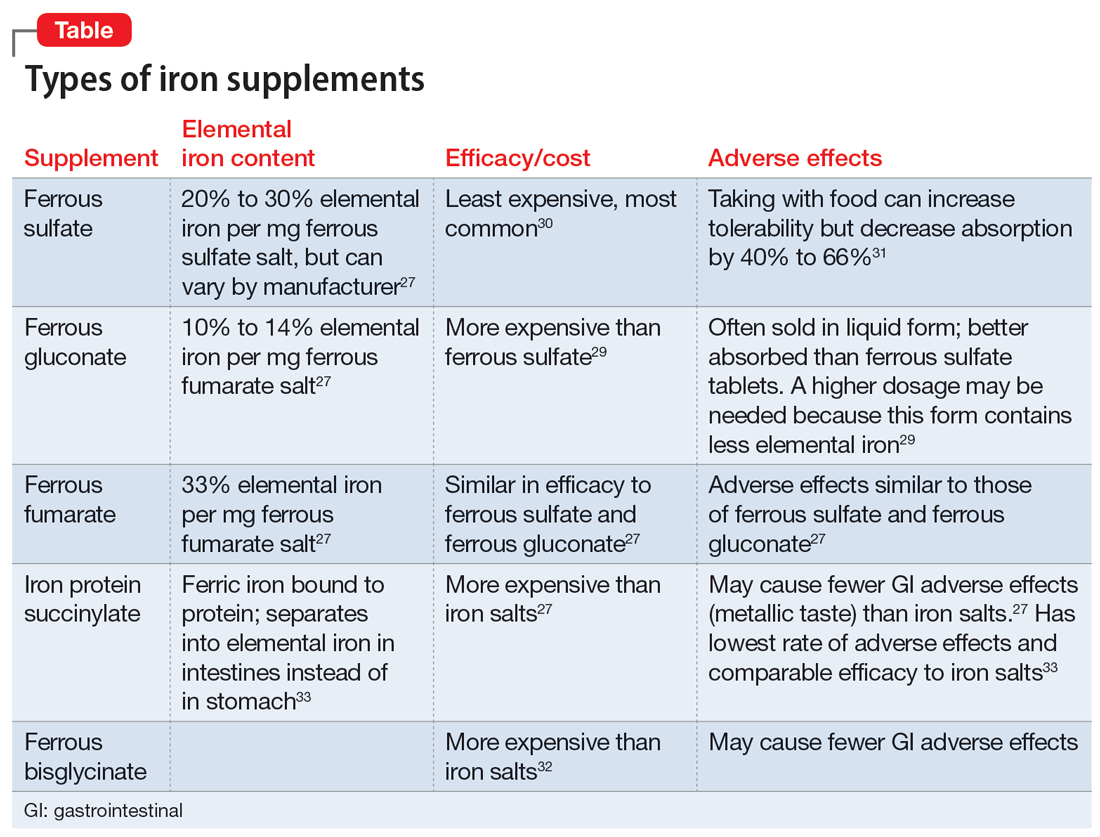

The amount of iron present, cost, and adverse effects vary by supplement. The Table27,29-33 provides more information on available forms of iron. Many forms of iron supplementation are available over-the-counter, and most are equally effective.27 Advise patients to use iron products that have been tested by an independent company, such as ConsumerLab.com. Such companies evaluate products to see if they contain the amount of iron listed on the product’s label; for contamination with lead, cadmium, or arsenic; and for the product’s ability to break apart for absorption.34

Six to 8 weeks of treatment with oral iron supplementation may be necessary before anemia is fully resolved, and it may take up to 6 months for iron stores to be repleted.27 If a patient cannot tolerate an iron supplement, reducing the dose or taking it with meals may help prevent adverse effects, but also will reduce absorption. Auerbach27 recommends assessing tolerability and rechecking the patient’s CBC 2 weeks after starting oral iron replacement, while also checking hemoglobin and the reticulocyte count to see if the patient is responding to treatment. An analysis of 5 studies found that a hemoglobin measurement on Day 14 that shows an increase ≥1.0 g/dL from baseline predicts longer-term and sustained treatment response to continued oral therapy.35 There is no clear consensus for target ferritin levels, but we suggest aiming for a ferritin level >100 ug/L based on recommendations for the treatment of restless legs syndrome.36 We recommend ongoing monitoring every 4 to 6 weeks.

Bottom Line

Iron deficiency is common and can cause or contribute to psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Consider screening patients for iron deficiency and treating it with oral supplementation in individuals without any comorbidities, or referring them to their primary care physician or specialist.

Related Resources

- Berthou C, Iliou JP, Barba D. Iron, neuro-bioavailability and depression. EJHaem. 2021;3(1):263-275.

1. McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, et al. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(4):444-454.

2. Mei Z, Addo OY, Jefferds ME, et al. Physiologically based serum ferritin thresholds for iron deficiency in children and non-pregnant women: a US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) serial cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(8):e572-e582.

3. Snozek CLH, Spears GM, Porco AB, et al. Updated ferritin reference intervals for the Roche Elecsys® immunoassay. Clin Biochem. 2021;87:100-103. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2020.11.006

4. Camaschella C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019;133(1):30-39. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-05-815944

5. Lozoff B, Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13(3):158-165.

6. Shah HE, Bhawnani N, Ethirajulu A, et al. Iron deficiency-induced changes in the hippocampus, corpus striatum, and monoamines levels that lead to anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and psychotic disorders. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e18138.

7. Hidese S, Saito K, Asano S, et al. Association between iron-deficiency anemia and depression: a web-based Japanese investigation. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(7):513-521.

8. Yi S, Nanri A, Poudel-Tandukar K, et al. Association between serum ferritin concentrations and depressive symptoms in Japanese municipal employees. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189(3):368-372.

9. Lee HS, Chao HH, Huang WT, et al. Psychiatric disorders risk in patients with iron deficiency anemia and association with iron supplementation medications: a nationwide database analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):216.

10. Xu M, Guo Y, Cheng J, et al. Brain iron assessment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia using quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;31:102736.

11. Kim SW, Stewart R, Park WY, et al. Latent iron deficiency as a marker of negative symptoms in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1707.

12. Chen MH, Su TP, Chen YS, et al. Association between psychiatric disorders and iron deficiency anemia among children and adolescents: a nationwide population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:161.

13. Stewart R, Hirani V. Relationship between depressive symptoms, anemia, and iron status in older residents from a national survey population. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(2):208-213.

14. Hanif N. Anwer F. Chronic iron deficiency. Updated September 10, 2022. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560876/

15.

16. Greig AJ, Patterson AJ, Collins CE, et al. Iron deficiency, cognition, mental health and fatigue in women of childbearing age: a systematic review. J Nutr Sci. 2013;2:e14.

17. Mikami K, Akama F, Kimoto K, et al. Iron supplementation for hypoferritinemia-related psychological symptoms in children and adolescents. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89(2):203-211.

18. McClung JP, Karl JP, Cable SJ, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of iron supplementation in female soldiers during military training: effects on iron status, physical performance, and mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):124-131.

19. Kassir A. Iron deficiency: a diagnostic and therapeutic perspective in psychiatry. Article in French. Encephale. 2017;43(1):85-89.

20. Houston BL, Hurrie D, Graham J, et al. Efficacy of iron supplementation on fatigue and physical capacity in non-anaemic iron-deficient adults: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019240. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019240

21. Krayenbuehl PA, Battegay E, Breymann C, et al. Intravenous iron for the treatment of fatigue in nonanemic, premenopausal women with low serum ferritin concentration. Blood. 2011;118(12):3222-3227. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-04-346304

22. Vaucher P, Druais PL, Waldvogel S, et al. Effect of iron supplementation on fatigue in nonanemic menstruating women with low ferritin: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2012;184(11):1247-1254. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110950

23. Pratt JJ, Khan KS. Non-anaemic iron deficiency - a disease looking for recognition of diagnosis: a systematic review. Eur J Haematol. 2016;96(6):618-628. doi:10.1111/ejh.12645

24. Al-Naseem A, Sallam A, Choudhury S, et al. Iron deficiency without anaemia: a diagnosis that matters. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(2):107-113. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2020-0582

25. National Institute of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Iron. Fact sheet for health professionals. Updated April 5, 2022. Accessed January 31, 2023. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iron-HealthProfessional/

26. Auerbach M. Causes and diagnosis of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in adults. UpToDate. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/causes-and-diagnosis-of-iron-deficiency-and-iron-deficiency-anemia-in-adults

27. Auerbach M. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia in adults. UpToDate. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-iron-deficiency-anemia-in-adults

28. Moretti D, Goede JS, Zeder C, et al. Oral iron supplements increase hepcidin and decrease iron absorption from daily or twice-daily doses in iron-depleted young women. Blood. 2015;126(17):1981-1989.

29. Cooperman T. Iron supplements review (iron pills, liquids and chews). ConsumerLab.com. Published January 31, 2022. Updated December 19, 2022. Accessed January 31, 2023. https://www.consumerlab.com/reviews/iron-supplements-review/iron/

30. Okam MM, Koch TA, Tran MH. Iron deficiency anemia treatment response to oral iron therapy: a pooled analysis of five randomized controlled trials. Haematologica. 2016;101(1):e6-e7.

31. Silber MH. Management of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults. UpToDate. Accessed July 10, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-restless-legs-syndrome-and-periodic-limb-movement-disorder-in-adults

32. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The nutrition source: iron. Accessed January 31, 2023. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/iron/

33. Little DR. Ambulatory management of common forms of anemia. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(6):1598-1604.

34. Blood modifiers. In: Drug Facts and Comparisons. Facts and Comparisons. 1998:238-257.

35. Cancelo-Hidalgo MJ, Castelo-Branco C, Palacios S, et al. Tolerability of different oral iron supplements: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(4):291-303.

36. Francés AM, Martínez-Bujanda JL. Efficacy and tolerability of oral iron protein succinylate: a systematic review of three decades of research. Curr Med Res Opinion. 2020;36(4):613-623. doi:10.1080/03007995.2020.1716702

Nutritional deficiencies are one of the many causes of or contributors to symptoms in patients with psychiatric disorders. In this article, we discuss the prevalence of iron deficiency and its link to poor mental health, and how proper treatment may improve psychiatric symptoms. We also offer suggestions for how and when to test for and treat iron deficiency in psychiatric patients.

A common condition

Iron deficiency is the most common mineral deficiency in the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 25% of the global population is anemic and nearly one-half of those cases are the result of iron deficiency.1 While the WHO has published guidelines defining iron deficiency as it relates to ferritin levels (<15 ug/L in adults and <12 ug/L in children), this estimate might be low.2,3 Mei et al2 found that hemoglobin and soluble transferrin receptors can be used to determine iron-deficient erythropoiesis, which indicates a physiological definition of iron deficiency. According to a study of children and nonpregnant women by Mei et al,2 children with ferritin levels <20 ug/L and women with ferritin levels <25 ug/L should be considered iron-deficient. If replicated, this study suggests the prevalence of iron deficiency is higher than currently estimated.2 Overall, an estimated 1.2 billion people worldwide have iron-deficiency anemia.4 Additionally, patients can be iron deficient without being anemic, a condition thought to be at least twice as common.4

Essential for brain function

Research shows the importance of iron to proper brain function.5 Iron deficiency in pregnant women is associated with significant neuropsychological impairments in neonates. Rodent studies have demonstrated the importance of iron and the effects of iron deficiency on the hippocampus, corpus striatum, and production of monoamines.5 Specifically, iron is a necessary cofactor in the enzymes tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase, which produce serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. In rodent studies, monoamine deficits secondary to iron deficiency persist into adulthood even with iron supplementation, which highlights the importance of preventing iron deficiency during pregnancy and early life.5 While most research has focused on the impact of iron deficiency in infancy and early childhood, iron deficiency has an ongoing impact into adulthood, even if treated.6

Iron deficiency and psychiatric symptoms

Current research suggests an association between iron deficiency or low ferritin levels and psychiatric disorders, specifically depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. In a web survey of 11,876 adults, Hidese et al7 found an association between a self-reported history of iron deficiency anemia and a self-reported history of depression. Another study of 528 municipal employees found an association between low serum ferritin concentrations and a high prevalence of depressive symptoms among men; no statistically significant association was detected in women.8 In an analysis of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database from 2000 to 2012, Lee et al9 found a statistically significant increased risk of anxiety disorders, depression, sleep disorders, and psychotic disorders in patients with iron deficiency anemia after controlling for multiple confounders. Xu et al10 used quantitative susceptibility mapping to assess the iron status in certain regions of the brain of 30 patients with first-episode psychosis. They found lower levels of iron in the bilateral substantia nigra, left red nucleus, and left thalamus compared to healthy controls.10 Kim et al11 found an association between iron deficiency and more severe negative symptoms in 121 patients with first-episode psychosis, which supports the hypothesis that iron deficiency may alter dopamine transmission in the brain.

Iron deficiency has been associated with psychopathology across the lifespan. In a population-based study in Taiwan, Chen et al12 found an association between iron deficiency anemia and psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents, including mood disorders, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and developmental disorders. At the other end of the age spectrum, in a survey of 1,875 older adults in England, Stewart et al13 found an association between low ferritin levels (<45 ng/mL) and depressive symptoms after adjusting for demographic factors and overall health status.

In addition to specific psychiatric disorders and symptoms, iron deficiency is often associated with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue.14 Fatigue is a symptom of numerous psychiatric disorders and is included in the DSM diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.15

Iron supplementation might improve psychiatric symptoms

Some evidence suggests that using iron supplementation to treat iron deficiency can improve psychiatric symptoms. In a 2013 systematic literature review of 10 studies, Greig et al16 found a link between low iron status and poor cognition, poor mental health scores, and fatigue among women of childbearing age. In this review, 7 studies demonstrated improvement in cognition and 3 demonstrated improvement in mental health with iron supplementation.16 In a 2021 prospective study, 19 children and adolescents age 6 to 15 who had serum ferritin levels <30 ng/mL were treated with oral iron supplementation for 12 weeks.17 Participants showed significant improvements in sleep quality, depressive symptoms, and general mood as assessed via the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaires, respectively.17 A randomized controlled trial of 219 female soldiers who were given iron supplementation or placebo for 8 weeks during basic combat training found that compared to placebo, iron supplementation led to improvements in mood as measured by the POMS questionnaire.18 Lastly, in a 2016 observational study of 412 adult psychiatric patients, Kassir19 found most patients (81%) had iron deficiency, defined as a transferrin saturation coefficient <30% or serum ferritin <100 ng/mL. Although these cutoffs are not considered standard and thus may have overrepresented the percentage of patients considered iron-deficient, more than one-half of patients considered iron-deficient in this study experienced a reduction or elimination of psychiatric symptoms following treatment with iron supplementation and/or psychotropic medications.19

Continue to: Individuals with iron deficiency...

Individuals with iron deficiency without anemia also may see improvement in psychiatric symptoms with iron treatment. In a 2018 systematic review, Houston et al20 evaluated iron supplementation in 1,170 adults who were iron-deficient but not anemic. They found that in these patients, fatigue significantly improved but physical capacity did not.20 Additionally, 2 other studies found iron treatment improved fatigue in nonanemic women.21,22 In a 2016 systematic review, Pratt et al23 concluded, “There is emerging evidence that … nonanemic iron deficiency … is a disease in its own right, deserving of further research in the development of strategies for detection and treatment.” Al-Naseem et al24 suggested severity distinguishes iron deficiency with and without anemia.

Your role in assessing and treating iron deficiency

Testing for and treating iron deficiency generally is not a part of routine psychiatric practice. This might be due to apathy given the pervasiveness of iron deficiency, a belief that iron deficiency should be managed by primary care physicians, or a lack of familiarity with how to treat it and the benefits of such treatment for psychiatric patients. However, assessing for and treating iron deficiency in psychiatric patients is important, especially for individuals who are highly susceptible to inadequate iron levels. People at risk for iron deficiency include pregnant women, infants, young children, women with heavy menstrual bleeding, frequent blood donors, patients with cancer, individuals who have gastrointestinal (GI) surgeries or disorders, and those with heart failure.25

Assessment. Iron status can be assessed through an iron studies panel. Because a patient can have iron deficiency without anemia, a complete blood count (CBC) alone does not suffice.26 The iron panel includes serum iron, serum ferritin, serum transferrin or total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and calculated transferrin saturation (TSAT), which is the ratio of serum iron to TIBC.

Iron deficiency is diagnosed if ferritin is <30 ng/mL, regardless of the hemoglobin concentration or underlying condition, and confirmed by a low TSAT.26 In most guidelines, the cutoff value for TSAT for iron deficiency is <20%. Because the TSAT can be influenced by iron supplements or iron-rich foods, wait several hours to obtain blood after a patient takes an oral iron supplement or eats iron-rich foods. If desired, clinicians can use either ferritin or TSAT alone to diagnose iron deficiency. However, because ferritin can be falsely normal in inflammatory conditions such as obesity and infection, a TSAT may be needed to confirm iron deficiency if there is a high clinical suspicion despite a normal ferritin level.26

Treatment. If iron deficiency is confirmed, instruct your patient to follow up with their primary care physician or the appropriate specialist to evaluate for any underlying etiologies.

Continue to: Iron deficiency should be treated...

Iron deficiency should be treated with supplementation because diet alone is insufficient for replenishing iron stores. Iron replacement can be oral or IV. Oral replacement is effective, safe, inexpensive, easy to obtain, and easy to administer.27 Oral replacement is recommended for adults whose anemia is not severe or who do not have a comorbid condition such as pregnancy, inflammatory bowel conditions, gastric surgery, or chronic kidney disease. When anemia is severe or a patient has one of these comorbid conditions, IV is the preferred method of replacement.27 In these cases, defer treatment to the patient’s primary care physician or specialist.

There are no clear recommendations on the amount of iron per dose to prescribe.27 The maximum amount of oral iron that can be absorbed is approximately 25 mg/d of elemental iron. A 325 mg ferrous sulfate tablet contains 65 mg of elemental iron, of which approximately 25 mg is absorbed and utilized.27

Emerging evidence suggests that excessive iron dosing may reduce iron absorption and increase adverse effects. In a study of 54 nonanemic young women with iron deficiency who were given iron supplementation, Moretti et al28 found that a large oral dose of iron taken in the morning increased hepcidin, which decreased the absorption of iron taken later for up to 48 hours. They found that 40 to 80 mg of elemental iron given on alternate days may maximize the fractional iron absorbed, increase dosage efficacy, reduce GI exposure to unabsorbed iron, and improve patients’ ability to tolerate iron supplementation.28

Adverse effects from iron supplements occur in up to 70% of patients.27 These can include metallic taste, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, diarrhea, epigastric pain, constipation, and dark stools.27 Using a liquid form may help reduce adverse effects because it can be more easily titrated.27 Tell patients to avoid enteric-coated or sustained-release iron capsules because these are poorly absorbed. Be cautious when prescribing iron supplementation to older adults because these patients tend to have more adverse effects, especially constipation, as well as reduced absorption, and may ultimately need IV treatment. Iron should not be taken with food, calcium supplements, antacids, coffee, tea, or milk.27

The amount of iron present, cost, and adverse effects vary by supplement. The Table27,29-33 provides more information on available forms of iron. Many forms of iron supplementation are available over-the-counter, and most are equally effective.27 Advise patients to use iron products that have been tested by an independent company, such as ConsumerLab.com. Such companies evaluate products to see if they contain the amount of iron listed on the product’s label; for contamination with lead, cadmium, or arsenic; and for the product’s ability to break apart for absorption.34

Six to 8 weeks of treatment with oral iron supplementation may be necessary before anemia is fully resolved, and it may take up to 6 months for iron stores to be repleted.27 If a patient cannot tolerate an iron supplement, reducing the dose or taking it with meals may help prevent adverse effects, but also will reduce absorption. Auerbach27 recommends assessing tolerability and rechecking the patient’s CBC 2 weeks after starting oral iron replacement, while also checking hemoglobin and the reticulocyte count to see if the patient is responding to treatment. An analysis of 5 studies found that a hemoglobin measurement on Day 14 that shows an increase ≥1.0 g/dL from baseline predicts longer-term and sustained treatment response to continued oral therapy.35 There is no clear consensus for target ferritin levels, but we suggest aiming for a ferritin level >100 ug/L based on recommendations for the treatment of restless legs syndrome.36 We recommend ongoing monitoring every 4 to 6 weeks.

Bottom Line

Iron deficiency is common and can cause or contribute to psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Consider screening patients for iron deficiency and treating it with oral supplementation in individuals without any comorbidities, or referring them to their primary care physician or specialist.

Related Resources

- Berthou C, Iliou JP, Barba D. Iron, neuro-bioavailability and depression. EJHaem. 2021;3(1):263-275.

Nutritional deficiencies are one of the many causes of or contributors to symptoms in patients with psychiatric disorders. In this article, we discuss the prevalence of iron deficiency and its link to poor mental health, and how proper treatment may improve psychiatric symptoms. We also offer suggestions for how and when to test for and treat iron deficiency in psychiatric patients.

A common condition

Iron deficiency is the most common mineral deficiency in the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 25% of the global population is anemic and nearly one-half of those cases are the result of iron deficiency.1 While the WHO has published guidelines defining iron deficiency as it relates to ferritin levels (<15 ug/L in adults and <12 ug/L in children), this estimate might be low.2,3 Mei et al2 found that hemoglobin and soluble transferrin receptors can be used to determine iron-deficient erythropoiesis, which indicates a physiological definition of iron deficiency. According to a study of children and nonpregnant women by Mei et al,2 children with ferritin levels <20 ug/L and women with ferritin levels <25 ug/L should be considered iron-deficient. If replicated, this study suggests the prevalence of iron deficiency is higher than currently estimated.2 Overall, an estimated 1.2 billion people worldwide have iron-deficiency anemia.4 Additionally, patients can be iron deficient without being anemic, a condition thought to be at least twice as common.4

Essential for brain function

Research shows the importance of iron to proper brain function.5 Iron deficiency in pregnant women is associated with significant neuropsychological impairments in neonates. Rodent studies have demonstrated the importance of iron and the effects of iron deficiency on the hippocampus, corpus striatum, and production of monoamines.5 Specifically, iron is a necessary cofactor in the enzymes tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase, which produce serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. In rodent studies, monoamine deficits secondary to iron deficiency persist into adulthood even with iron supplementation, which highlights the importance of preventing iron deficiency during pregnancy and early life.5 While most research has focused on the impact of iron deficiency in infancy and early childhood, iron deficiency has an ongoing impact into adulthood, even if treated.6

Iron deficiency and psychiatric symptoms

Current research suggests an association between iron deficiency or low ferritin levels and psychiatric disorders, specifically depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia. In a web survey of 11,876 adults, Hidese et al7 found an association between a self-reported history of iron deficiency anemia and a self-reported history of depression. Another study of 528 municipal employees found an association between low serum ferritin concentrations and a high prevalence of depressive symptoms among men; no statistically significant association was detected in women.8 In an analysis of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database from 2000 to 2012, Lee et al9 found a statistically significant increased risk of anxiety disorders, depression, sleep disorders, and psychotic disorders in patients with iron deficiency anemia after controlling for multiple confounders. Xu et al10 used quantitative susceptibility mapping to assess the iron status in certain regions of the brain of 30 patients with first-episode psychosis. They found lower levels of iron in the bilateral substantia nigra, left red nucleus, and left thalamus compared to healthy controls.10 Kim et al11 found an association between iron deficiency and more severe negative symptoms in 121 patients with first-episode psychosis, which supports the hypothesis that iron deficiency may alter dopamine transmission in the brain.

Iron deficiency has been associated with psychopathology across the lifespan. In a population-based study in Taiwan, Chen et al12 found an association between iron deficiency anemia and psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents, including mood disorders, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and developmental disorders. At the other end of the age spectrum, in a survey of 1,875 older adults in England, Stewart et al13 found an association between low ferritin levels (<45 ng/mL) and depressive symptoms after adjusting for demographic factors and overall health status.

In addition to specific psychiatric disorders and symptoms, iron deficiency is often associated with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue.14 Fatigue is a symptom of numerous psychiatric disorders and is included in the DSM diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.15

Iron supplementation might improve psychiatric symptoms