User login

Troponin I: Powerful all-cause mortality risk marker in COPD

PARIS – High relative even after researchers adjusted for all major cardiovascular and COPD prognostic indicators, according to a late-breaker presentation at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Troponin I is detectable in the plasma of most patients with COPD, but relative increases in troponin I correlate with greater relative increases in most cardiovascular and COPD risk factors, according to Benjamin Waschki, MD, Pulmonary Research Institute, LungenClinic, Grosshansdorf, Germany.

The relationship between increased troponin I and increased all-cause mortality was observed in an on-going prospective multicenter cohort of COPD patients followed at 31 centers in Germany. The cohort is called COSYCONET and it began in 2010. The current analysis evaluated 2,020 COPD patients without regard to stage of disease.

There were 136 deaths over the course of follow-up. Without adjustment, the hazard ratio (HR) for death was more than twofold higher in the highest quartile of troponin I (equal to or greater than 6.6 ng/mL), when compared with the lowest (under 2.5 ng/mL) (HR, 2.42; P less than .001). Graphically, the mortality curves for each of the quartiles began to separate at about 12 months, widening in a stepwise manner for greater likelihood of death from the lowest to highest quartiles.

The risk of death from any cause remained elevated for the highest relative to lowest troponin I quartiles after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors and after adjusting for COPD severity. Again, there was a distinct stepwise separation of the mortality curves for each higher troponin quartile,

Of particular importance, troponin I remained predictive beyond the BODE index, which is a currently employed prognostic mortality predictor in COPD, according to Dr. Waschki. When defining elevated troponin as greater than 6 ng/ML and a high BODE score as greater than 4, mortality was higher for those with a high BODE and low troponin than a high troponin and low BODE, (P less than .001), but a high troponin I was associated with a higher risk of mortality when BODE was low (P less than .001). Moreover, when both troponin I and BODE were elevated, all-cause mortality was more than doubled, relative to those without either risk factor (HR, 2.56; P = .003), Dr. Waschki reported.

After researchers adjusted for major cardiovascular risk factors, such as history of MI and renal impairment, and for major COPD risk factors, such as 6-minute walk test and BODE index, those in the highest quartile had a more than 50% greater risk of death relative to those in the lower quartile over the 3 years of follow-up (HR, 1.69; P = .007), according to Dr. Waschki.

Although troponin I is best known for its diagnostic role in MI, it is now being evaluated as a risk stratifier for many chronic diseases, such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease, explained Dr. Waschki in providing background for this study. He reported that many groups are looking at this as a marker of risk in a variety of chronic diseases.

In fact, a group working independently published a study in COPD just weeks before the ERS Congress that was complementary to those presented by Dr. Waschki. In this study, the goal was to evaluate troponin I as a predictor of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death (Adamson PD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1126-37). Performed as a subgroup analysis of 1,599 COPD patients participating in a large treatment trial, there was an almost fourfold increase in the risk of cardiovascular events (HR, 3.7; P = .012) when those in the highest quintile of troponin I (greater than 7.7 ng/ML) were compared with those in the lowest quintile (less than 2.3 ng/mL).

When compared for cardiovascular death, the highest quintile, relative to the lowest quintile, had a more than 20-fold increased risk of cardiovascular death (HR 20.1; P = .005). In the Adamson et al. study, which evaluated inhaled therapies for COPD, treatment response had no impact on troponin I levels or on the risk of cardiovascular events or death.

Based on this study and his own data, Dr. Waschki believes troponin I, which is readily ordered laboratory value, appears to be a useful tool for identifying COPD patients at high risk of death.

“The major message is that after adjusting for all known COPD and cardiovascular risk factors, troponin I remains a significant independent predictor of mortality,” he said.

Dr. Waschki reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

PARIS – High relative even after researchers adjusted for all major cardiovascular and COPD prognostic indicators, according to a late-breaker presentation at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Troponin I is detectable in the plasma of most patients with COPD, but relative increases in troponin I correlate with greater relative increases in most cardiovascular and COPD risk factors, according to Benjamin Waschki, MD, Pulmonary Research Institute, LungenClinic, Grosshansdorf, Germany.

The relationship between increased troponin I and increased all-cause mortality was observed in an on-going prospective multicenter cohort of COPD patients followed at 31 centers in Germany. The cohort is called COSYCONET and it began in 2010. The current analysis evaluated 2,020 COPD patients without regard to stage of disease.

There were 136 deaths over the course of follow-up. Without adjustment, the hazard ratio (HR) for death was more than twofold higher in the highest quartile of troponin I (equal to or greater than 6.6 ng/mL), when compared with the lowest (under 2.5 ng/mL) (HR, 2.42; P less than .001). Graphically, the mortality curves for each of the quartiles began to separate at about 12 months, widening in a stepwise manner for greater likelihood of death from the lowest to highest quartiles.

The risk of death from any cause remained elevated for the highest relative to lowest troponin I quartiles after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors and after adjusting for COPD severity. Again, there was a distinct stepwise separation of the mortality curves for each higher troponin quartile,

Of particular importance, troponin I remained predictive beyond the BODE index, which is a currently employed prognostic mortality predictor in COPD, according to Dr. Waschki. When defining elevated troponin as greater than 6 ng/ML and a high BODE score as greater than 4, mortality was higher for those with a high BODE and low troponin than a high troponin and low BODE, (P less than .001), but a high troponin I was associated with a higher risk of mortality when BODE was low (P less than .001). Moreover, when both troponin I and BODE were elevated, all-cause mortality was more than doubled, relative to those without either risk factor (HR, 2.56; P = .003), Dr. Waschki reported.

After researchers adjusted for major cardiovascular risk factors, such as history of MI and renal impairment, and for major COPD risk factors, such as 6-minute walk test and BODE index, those in the highest quartile had a more than 50% greater risk of death relative to those in the lower quartile over the 3 years of follow-up (HR, 1.69; P = .007), according to Dr. Waschki.

Although troponin I is best known for its diagnostic role in MI, it is now being evaluated as a risk stratifier for many chronic diseases, such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease, explained Dr. Waschki in providing background for this study. He reported that many groups are looking at this as a marker of risk in a variety of chronic diseases.

In fact, a group working independently published a study in COPD just weeks before the ERS Congress that was complementary to those presented by Dr. Waschki. In this study, the goal was to evaluate troponin I as a predictor of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death (Adamson PD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1126-37). Performed as a subgroup analysis of 1,599 COPD patients participating in a large treatment trial, there was an almost fourfold increase in the risk of cardiovascular events (HR, 3.7; P = .012) when those in the highest quintile of troponin I (greater than 7.7 ng/ML) were compared with those in the lowest quintile (less than 2.3 ng/mL).

When compared for cardiovascular death, the highest quintile, relative to the lowest quintile, had a more than 20-fold increased risk of cardiovascular death (HR 20.1; P = .005). In the Adamson et al. study, which evaluated inhaled therapies for COPD, treatment response had no impact on troponin I levels or on the risk of cardiovascular events or death.

Based on this study and his own data, Dr. Waschki believes troponin I, which is readily ordered laboratory value, appears to be a useful tool for identifying COPD patients at high risk of death.

“The major message is that after adjusting for all known COPD and cardiovascular risk factors, troponin I remains a significant independent predictor of mortality,” he said.

Dr. Waschki reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

PARIS – High relative even after researchers adjusted for all major cardiovascular and COPD prognostic indicators, according to a late-breaker presentation at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Troponin I is detectable in the plasma of most patients with COPD, but relative increases in troponin I correlate with greater relative increases in most cardiovascular and COPD risk factors, according to Benjamin Waschki, MD, Pulmonary Research Institute, LungenClinic, Grosshansdorf, Germany.

The relationship between increased troponin I and increased all-cause mortality was observed in an on-going prospective multicenter cohort of COPD patients followed at 31 centers in Germany. The cohort is called COSYCONET and it began in 2010. The current analysis evaluated 2,020 COPD patients without regard to stage of disease.

There were 136 deaths over the course of follow-up. Without adjustment, the hazard ratio (HR) for death was more than twofold higher in the highest quartile of troponin I (equal to or greater than 6.6 ng/mL), when compared with the lowest (under 2.5 ng/mL) (HR, 2.42; P less than .001). Graphically, the mortality curves for each of the quartiles began to separate at about 12 months, widening in a stepwise manner for greater likelihood of death from the lowest to highest quartiles.

The risk of death from any cause remained elevated for the highest relative to lowest troponin I quartiles after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors and after adjusting for COPD severity. Again, there was a distinct stepwise separation of the mortality curves for each higher troponin quartile,

Of particular importance, troponin I remained predictive beyond the BODE index, which is a currently employed prognostic mortality predictor in COPD, according to Dr. Waschki. When defining elevated troponin as greater than 6 ng/ML and a high BODE score as greater than 4, mortality was higher for those with a high BODE and low troponin than a high troponin and low BODE, (P less than .001), but a high troponin I was associated with a higher risk of mortality when BODE was low (P less than .001). Moreover, when both troponin I and BODE were elevated, all-cause mortality was more than doubled, relative to those without either risk factor (HR, 2.56; P = .003), Dr. Waschki reported.

After researchers adjusted for major cardiovascular risk factors, such as history of MI and renal impairment, and for major COPD risk factors, such as 6-minute walk test and BODE index, those in the highest quartile had a more than 50% greater risk of death relative to those in the lower quartile over the 3 years of follow-up (HR, 1.69; P = .007), according to Dr. Waschki.

Although troponin I is best known for its diagnostic role in MI, it is now being evaluated as a risk stratifier for many chronic diseases, such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease, explained Dr. Waschki in providing background for this study. He reported that many groups are looking at this as a marker of risk in a variety of chronic diseases.

In fact, a group working independently published a study in COPD just weeks before the ERS Congress that was complementary to those presented by Dr. Waschki. In this study, the goal was to evaluate troponin I as a predictor of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular death (Adamson PD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1126-37). Performed as a subgroup analysis of 1,599 COPD patients participating in a large treatment trial, there was an almost fourfold increase in the risk of cardiovascular events (HR, 3.7; P = .012) when those in the highest quintile of troponin I (greater than 7.7 ng/ML) were compared with those in the lowest quintile (less than 2.3 ng/mL).

When compared for cardiovascular death, the highest quintile, relative to the lowest quintile, had a more than 20-fold increased risk of cardiovascular death (HR 20.1; P = .005). In the Adamson et al. study, which evaluated inhaled therapies for COPD, treatment response had no impact on troponin I levels or on the risk of cardiovascular events or death.

Based on this study and his own data, Dr. Waschki believes troponin I, which is readily ordered laboratory value, appears to be a useful tool for identifying COPD patients at high risk of death.

“The major message is that after adjusting for all known COPD and cardiovascular risk factors, troponin I remains a significant independent predictor of mortality,” he said.

Dr. Waschki reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM ERS CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: Elevated troponin I identifies COPD patients with increased mortality risk independent of all other clinical risk markers.

Major finding: With high troponin I levels, all-cause mortality was increased 69% after researchers adjusted for other risk markers.

Study details: Analysis drawn from on-going multicenter cohort study

Disclosures: Dr. Waschki reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Azithromycin for COPD exacerbations may reduce treatment failure

PARIS – In patients with a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (provided improvement in a variety of outcomes at 90 days, including risk of death, according to a placebo-controlled trial presented as a late-breaker at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

In patients with COPD, “azithromycin initiated in the acute setting and continued for 3 months appears to be safe and potentially effective,” reported Wim Janssens, MD, PhD, division of respiratory medicine, University Hospital, Leuven, Belgium.

The phrase “potentially effective” was used because the primary endpoint, which was time to treatment failure, fell just short of statistical significance (P = .053), but the rate of treatment failures, which was a coprimary endpoint (P = .04), and all of the secondary endpoints, including mortality at 90 days (P = .027), need for treatment intensification (P = .02) and need for an intensive care unit (ICU) admission (P = .003), were significantly lower in the group receiving azithromycin rather than placebo.

In a previous trial, chronic azithromycin therapy on top of usual care in patients frequently hospitalized for COPD was associated with a reduction in the risk of exacerbations and an improvement in quality of life (N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-98). However, Dr. Janssens explained that this strategy is not commonly used because it was associated with a variety of adverse events, not least of which was QTc prolongation.

The study at the meeting, called the BACE trial, was designed to test whether azithromycin could be employed in a more targeted approach to control exacerbations. In the study, 301 COPD patients hospitalized with an acute exacerbation were randomized within 48 hours of admission to azithromycin or placebo. For the first 3 days, azithromycin was administered in a 500-mg dose. Thereafter, the dose was 250 mg every second day. Treatment was stopped at 90 days.

The primary outcome was time to treatment failure, a novel composite endpoint of any of three events: the need for treatment intensification, the need for step-up hospital care (either ICU admission or hospital readmission), or death by any cause. The two treatment arms were also compared for safety, including QTc prolongation.

The treatment failure rates were 49% in the azithromycin arm and 60% in the placebo arm, producing a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.73. Although this outcome fell short of significance, Dr. Janssens suggested that benefits over the 90 days of treatment are supported by the secondary outcomes. However, he also cautioned that most relative advantages for azithromycin over placebo were found to dissipate over time.

“The maximum separation between the azithromycin and placebo arms [for the primary outcome] occurred at 120 days or 30 days after the medication was stopped,” Dr. Janssens reported. After this point, the two arms converged and eventually overlapped.

However, the acute benefits appeared to be substantial. For example, average hospital stay over the 90-day treatment period was reduced from 40 to 10 days (P = .0061), and the ICU days fell from 11 days to 3 days in the azithromycin relative to the placebo group. According to Dr. Janssens, the difference in hospital stay carries “important health economic potential that deserves further attention.”

Of the three QTc events that occurred during the course of the study, one was observed in the placebo group. There was no significant difference in this or other adverse events, according to Dr. Janssens.

It is notable that the design for the BACE trial called for 500 patients. When enrollment was slow, the design was changed on the basis of power calculations indicating that 300 patients would be sufficient to demonstrate a difference. It is unclear whether a larger study would have permitted the difference in the primary endpoint to advance from a trend.

Dr. Janssens reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

PARIS – In patients with a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (provided improvement in a variety of outcomes at 90 days, including risk of death, according to a placebo-controlled trial presented as a late-breaker at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

In patients with COPD, “azithromycin initiated in the acute setting and continued for 3 months appears to be safe and potentially effective,” reported Wim Janssens, MD, PhD, division of respiratory medicine, University Hospital, Leuven, Belgium.

The phrase “potentially effective” was used because the primary endpoint, which was time to treatment failure, fell just short of statistical significance (P = .053), but the rate of treatment failures, which was a coprimary endpoint (P = .04), and all of the secondary endpoints, including mortality at 90 days (P = .027), need for treatment intensification (P = .02) and need for an intensive care unit (ICU) admission (P = .003), were significantly lower in the group receiving azithromycin rather than placebo.

In a previous trial, chronic azithromycin therapy on top of usual care in patients frequently hospitalized for COPD was associated with a reduction in the risk of exacerbations and an improvement in quality of life (N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-98). However, Dr. Janssens explained that this strategy is not commonly used because it was associated with a variety of adverse events, not least of which was QTc prolongation.

The study at the meeting, called the BACE trial, was designed to test whether azithromycin could be employed in a more targeted approach to control exacerbations. In the study, 301 COPD patients hospitalized with an acute exacerbation were randomized within 48 hours of admission to azithromycin or placebo. For the first 3 days, azithromycin was administered in a 500-mg dose. Thereafter, the dose was 250 mg every second day. Treatment was stopped at 90 days.

The primary outcome was time to treatment failure, a novel composite endpoint of any of three events: the need for treatment intensification, the need for step-up hospital care (either ICU admission or hospital readmission), or death by any cause. The two treatment arms were also compared for safety, including QTc prolongation.

The treatment failure rates were 49% in the azithromycin arm and 60% in the placebo arm, producing a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.73. Although this outcome fell short of significance, Dr. Janssens suggested that benefits over the 90 days of treatment are supported by the secondary outcomes. However, he also cautioned that most relative advantages for azithromycin over placebo were found to dissipate over time.

“The maximum separation between the azithromycin and placebo arms [for the primary outcome] occurred at 120 days or 30 days after the medication was stopped,” Dr. Janssens reported. After this point, the two arms converged and eventually overlapped.

However, the acute benefits appeared to be substantial. For example, average hospital stay over the 90-day treatment period was reduced from 40 to 10 days (P = .0061), and the ICU days fell from 11 days to 3 days in the azithromycin relative to the placebo group. According to Dr. Janssens, the difference in hospital stay carries “important health economic potential that deserves further attention.”

Of the three QTc events that occurred during the course of the study, one was observed in the placebo group. There was no significant difference in this or other adverse events, according to Dr. Janssens.

It is notable that the design for the BACE trial called for 500 patients. When enrollment was slow, the design was changed on the basis of power calculations indicating that 300 patients would be sufficient to demonstrate a difference. It is unclear whether a larger study would have permitted the difference in the primary endpoint to advance from a trend.

Dr. Janssens reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

PARIS – In patients with a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (provided improvement in a variety of outcomes at 90 days, including risk of death, according to a placebo-controlled trial presented as a late-breaker at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

In patients with COPD, “azithromycin initiated in the acute setting and continued for 3 months appears to be safe and potentially effective,” reported Wim Janssens, MD, PhD, division of respiratory medicine, University Hospital, Leuven, Belgium.

The phrase “potentially effective” was used because the primary endpoint, which was time to treatment failure, fell just short of statistical significance (P = .053), but the rate of treatment failures, which was a coprimary endpoint (P = .04), and all of the secondary endpoints, including mortality at 90 days (P = .027), need for treatment intensification (P = .02) and need for an intensive care unit (ICU) admission (P = .003), were significantly lower in the group receiving azithromycin rather than placebo.

In a previous trial, chronic azithromycin therapy on top of usual care in patients frequently hospitalized for COPD was associated with a reduction in the risk of exacerbations and an improvement in quality of life (N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-98). However, Dr. Janssens explained that this strategy is not commonly used because it was associated with a variety of adverse events, not least of which was QTc prolongation.

The study at the meeting, called the BACE trial, was designed to test whether azithromycin could be employed in a more targeted approach to control exacerbations. In the study, 301 COPD patients hospitalized with an acute exacerbation were randomized within 48 hours of admission to azithromycin or placebo. For the first 3 days, azithromycin was administered in a 500-mg dose. Thereafter, the dose was 250 mg every second day. Treatment was stopped at 90 days.

The primary outcome was time to treatment failure, a novel composite endpoint of any of three events: the need for treatment intensification, the need for step-up hospital care (either ICU admission or hospital readmission), or death by any cause. The two treatment arms were also compared for safety, including QTc prolongation.

The treatment failure rates were 49% in the azithromycin arm and 60% in the placebo arm, producing a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.73. Although this outcome fell short of significance, Dr. Janssens suggested that benefits over the 90 days of treatment are supported by the secondary outcomes. However, he also cautioned that most relative advantages for azithromycin over placebo were found to dissipate over time.

“The maximum separation between the azithromycin and placebo arms [for the primary outcome] occurred at 120 days or 30 days after the medication was stopped,” Dr. Janssens reported. After this point, the two arms converged and eventually overlapped.

However, the acute benefits appeared to be substantial. For example, average hospital stay over the 90-day treatment period was reduced from 40 to 10 days (P = .0061), and the ICU days fell from 11 days to 3 days in the azithromycin relative to the placebo group. According to Dr. Janssens, the difference in hospital stay carries “important health economic potential that deserves further attention.”

Of the three QTc events that occurred during the course of the study, one was observed in the placebo group. There was no significant difference in this or other adverse events, according to Dr. Janssens.

It is notable that the design for the BACE trial called for 500 patients. When enrollment was slow, the design was changed on the basis of power calculations indicating that 300 patients would be sufficient to demonstrate a difference. It is unclear whether a larger study would have permitted the difference in the primary endpoint to advance from a trend.

Dr. Janssens reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

REPORTING FROM THE ERS CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: Initiating azithromycin in patients with COPD exacerbation at the time of hospitalization improves short-term outcomes.

Major finding: Relative to placebo, azithromycin provided a borderline reduction in treatment failure (P = .053) while reducing mortality (P = .027).

Study details: Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Janssens reports no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Increased COPD mortality with secondhand smoke exposure in childhood

Prolonged exposure to in adulthood, new research has found.

With data from 70,900 never-smoking men and women, most aged 50 years or over, in the Cancer Prevention Study–II Nutrition Cohort, researchers examined associations between childhood and adult secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of death during adulthood from all causes, heart disease, stroke, and COPD. Participants were followed from enrollment in 1992-1993 to 2016-2017.

In a paper published in the September issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, they reported that individuals who had lived with a smoker throughout childhood (16-18 years) had a 31% higher risk of dying from COPD, compared with individuals not exposed to secondhand smoke during childhood (95% confidence interval 1.05-1.65, P = .06). Any exposure to secondhand smoke in childhood – defined as one or more hours of exposure per week – was associated with a 21% higher risk of COPD mortality.

“It is established that SHS [secondhand smoke] exposure in childhood can result in asthma, chronic wheezing, respiratory infections, and decreased lung function and growth in children,” wrote W. Ryan Diver, a cancer epidemiologist, and his colleagues from the Epidemiology Research Program at the American Cancer Society. “These respiratory illnesses in early life are associated with worse lung function in adolescence and adulthood, as indicated by a lower forced expiratory volume in a 1 second plateau, and ultimately diagnosis of COPD.”

The researchers did not see a significant association between childhood secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of death from ischemic heart disease or stroke in adulthood. But the authors said that there was compelling evidence that secondhand smoke exposure during childhood contributed to increased arterial stiffness, autonomic dysfunction, and other vascular effects, which had led to the hypothesis that such exposure might influence the risk of heart disease and stroke mortality in adulthood. They suggested that this effect might have been more apparent in generations born in the 1950s and 1960s, where both parents were likely to smoke at home, as opposed to just one parent, which would have meant higher levels of exposure to secondhand smoke.

Adult exposure to secondhand smoke showed a significant dose-response relationship with overall mortality. Those exposed for 10 or more hours a week showed a 9% higher risk of death from all causes (95% CI 1.04-1.14, P less than .0001), as well as a significant 27% higher risk of death from ischemic heart disease.

Any exposure to secondhand smoke in adulthood was associated with a 14% higher risk of stroke, with a trend of increasing risk with increasing exposure.

The researchers also saw a significant association between secondhand smoke exposure and COPD mortality, but only in adults who reported being exposed both outside and inside the home.

The authors noted that the most recent Surgeon General’s report found that the evidence on secondhand smoke and increased risk of death from COPD was “suggestive but not sufficient,” and further research was needed.

“The associations observed with both childhood exposure to SHS and adult exposure to SHS add to the mounting data relating SHS to COPD,” they wrote.

One limitation of the study was that it relied on self-report, which in the case of childhood exposure would have required some participants to recall at least 3 decades back. It also did not capture whether it was the mother or father who smoked, which meant the authors could not account for possible effects of smoking during pregnancy.

The investigators noted that “more than 50 years after the publication of the first Surgeon General report on smoking and health, these findings suggest that researchers and scientists still do not fully understand the long-term health consequences of smoking, particularly, the potential delayed effects of childhood SHS exposure in later adulthood.” Despite this, the authors said the findings “provide further support for implementation of smoke-free air laws, smoke-free home policies, and clinical interventions to reduce SHS exposure.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Diver WR et al. Am J Prev Med 2018;55[3]:345-52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.005.

Prolonged exposure to in adulthood, new research has found.

With data from 70,900 never-smoking men and women, most aged 50 years or over, in the Cancer Prevention Study–II Nutrition Cohort, researchers examined associations between childhood and adult secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of death during adulthood from all causes, heart disease, stroke, and COPD. Participants were followed from enrollment in 1992-1993 to 2016-2017.

In a paper published in the September issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, they reported that individuals who had lived with a smoker throughout childhood (16-18 years) had a 31% higher risk of dying from COPD, compared with individuals not exposed to secondhand smoke during childhood (95% confidence interval 1.05-1.65, P = .06). Any exposure to secondhand smoke in childhood – defined as one or more hours of exposure per week – was associated with a 21% higher risk of COPD mortality.

“It is established that SHS [secondhand smoke] exposure in childhood can result in asthma, chronic wheezing, respiratory infections, and decreased lung function and growth in children,” wrote W. Ryan Diver, a cancer epidemiologist, and his colleagues from the Epidemiology Research Program at the American Cancer Society. “These respiratory illnesses in early life are associated with worse lung function in adolescence and adulthood, as indicated by a lower forced expiratory volume in a 1 second plateau, and ultimately diagnosis of COPD.”

The researchers did not see a significant association between childhood secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of death from ischemic heart disease or stroke in adulthood. But the authors said that there was compelling evidence that secondhand smoke exposure during childhood contributed to increased arterial stiffness, autonomic dysfunction, and other vascular effects, which had led to the hypothesis that such exposure might influence the risk of heart disease and stroke mortality in adulthood. They suggested that this effect might have been more apparent in generations born in the 1950s and 1960s, where both parents were likely to smoke at home, as opposed to just one parent, which would have meant higher levels of exposure to secondhand smoke.

Adult exposure to secondhand smoke showed a significant dose-response relationship with overall mortality. Those exposed for 10 or more hours a week showed a 9% higher risk of death from all causes (95% CI 1.04-1.14, P less than .0001), as well as a significant 27% higher risk of death from ischemic heart disease.

Any exposure to secondhand smoke in adulthood was associated with a 14% higher risk of stroke, with a trend of increasing risk with increasing exposure.

The researchers also saw a significant association between secondhand smoke exposure and COPD mortality, but only in adults who reported being exposed both outside and inside the home.

The authors noted that the most recent Surgeon General’s report found that the evidence on secondhand smoke and increased risk of death from COPD was “suggestive but not sufficient,” and further research was needed.

“The associations observed with both childhood exposure to SHS and adult exposure to SHS add to the mounting data relating SHS to COPD,” they wrote.

One limitation of the study was that it relied on self-report, which in the case of childhood exposure would have required some participants to recall at least 3 decades back. It also did not capture whether it was the mother or father who smoked, which meant the authors could not account for possible effects of smoking during pregnancy.

The investigators noted that “more than 50 years after the publication of the first Surgeon General report on smoking and health, these findings suggest that researchers and scientists still do not fully understand the long-term health consequences of smoking, particularly, the potential delayed effects of childhood SHS exposure in later adulthood.” Despite this, the authors said the findings “provide further support for implementation of smoke-free air laws, smoke-free home policies, and clinical interventions to reduce SHS exposure.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Diver WR et al. Am J Prev Med 2018;55[3]:345-52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.005.

Prolonged exposure to in adulthood, new research has found.

With data from 70,900 never-smoking men and women, most aged 50 years or over, in the Cancer Prevention Study–II Nutrition Cohort, researchers examined associations between childhood and adult secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of death during adulthood from all causes, heart disease, stroke, and COPD. Participants were followed from enrollment in 1992-1993 to 2016-2017.

In a paper published in the September issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, they reported that individuals who had lived with a smoker throughout childhood (16-18 years) had a 31% higher risk of dying from COPD, compared with individuals not exposed to secondhand smoke during childhood (95% confidence interval 1.05-1.65, P = .06). Any exposure to secondhand smoke in childhood – defined as one or more hours of exposure per week – was associated with a 21% higher risk of COPD mortality.

“It is established that SHS [secondhand smoke] exposure in childhood can result in asthma, chronic wheezing, respiratory infections, and decreased lung function and growth in children,” wrote W. Ryan Diver, a cancer epidemiologist, and his colleagues from the Epidemiology Research Program at the American Cancer Society. “These respiratory illnesses in early life are associated with worse lung function in adolescence and adulthood, as indicated by a lower forced expiratory volume in a 1 second plateau, and ultimately diagnosis of COPD.”

The researchers did not see a significant association between childhood secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of death from ischemic heart disease or stroke in adulthood. But the authors said that there was compelling evidence that secondhand smoke exposure during childhood contributed to increased arterial stiffness, autonomic dysfunction, and other vascular effects, which had led to the hypothesis that such exposure might influence the risk of heart disease and stroke mortality in adulthood. They suggested that this effect might have been more apparent in generations born in the 1950s and 1960s, where both parents were likely to smoke at home, as opposed to just one parent, which would have meant higher levels of exposure to secondhand smoke.

Adult exposure to secondhand smoke showed a significant dose-response relationship with overall mortality. Those exposed for 10 or more hours a week showed a 9% higher risk of death from all causes (95% CI 1.04-1.14, P less than .0001), as well as a significant 27% higher risk of death from ischemic heart disease.

Any exposure to secondhand smoke in adulthood was associated with a 14% higher risk of stroke, with a trend of increasing risk with increasing exposure.

The researchers also saw a significant association between secondhand smoke exposure and COPD mortality, but only in adults who reported being exposed both outside and inside the home.

The authors noted that the most recent Surgeon General’s report found that the evidence on secondhand smoke and increased risk of death from COPD was “suggestive but not sufficient,” and further research was needed.

“The associations observed with both childhood exposure to SHS and adult exposure to SHS add to the mounting data relating SHS to COPD,” they wrote.

One limitation of the study was that it relied on self-report, which in the case of childhood exposure would have required some participants to recall at least 3 decades back. It also did not capture whether it was the mother or father who smoked, which meant the authors could not account for possible effects of smoking during pregnancy.

The investigators noted that “more than 50 years after the publication of the first Surgeon General report on smoking and health, these findings suggest that researchers and scientists still do not fully understand the long-term health consequences of smoking, particularly, the potential delayed effects of childhood SHS exposure in later adulthood.” Despite this, the authors said the findings “provide further support for implementation of smoke-free air laws, smoke-free home policies, and clinical interventions to reduce SHS exposure.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Diver WR et al. Am J Prev Med 2018;55[3]:345-52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.005.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Childhood secondhand smoke exposure is linked to increased COPD mortality in adulthood.

Major finding: Adults who were exposed to secondhand smoke throughout childhood have a 31% higher risk of COPD mortality than do those not exposed.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 70,900 never-smoking men and women enrolled in the Cancer Prevention Study–II Nutrition Cohort.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Diver W et al. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55[3]:345-52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.005.

Declining lung function linked to heart failure, stroke

Rapid declines in spirometric measures of lung function were associated with higher risks of cardiovascular disease, according to a recent analysis of a large, prospective cohort study.

Rapid declines in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were associated with increased incidence of heart failure, stroke, and death in the analysis of the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study.

The risk of incident heart failure among FEV1 rapid decliners was particularly high, with a fourfold increase within 12 months. That suggests clinicians should carefully consider incipient heart failure in patients with rapid changes in FEV1, investigators reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Rapid declines in forced vital capacity (FVC) were also associated with higher incidences of heart failure and death in the analysis by Odilson M. Silvestre, MD, of the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

The analysis included a total of 10,351 ARIC participants with a mean follow-up of 17 years. All had undergone spirometry at the first study visit between 1987 and 1989, and on the second visit between 1990 and 1992.

One-quarter of participants were classified as FEV1 rapid decliners, defined by an FEV1 decrease of at least 1.9% per year. Likewise, one-quarter of participants were classified as FVC rapid decliners, based on an FVC decrease of at least 2.1%.

Rapid decline in FEV1 was associated with a higher risk of incident heart failure (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.33; P = .010), and was most prognostic in the first year of follow-up (HR, 4.22; 95% CI, 1.34-13.26; P = .01), investigators said.

Rapid decline in FVC was likewise associated with a greater heart failure risk (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.12-1.44; P less than .001).

Increased heart failure risk persisted after excluding patients with incident coronary heart disease in both the FEV1 and FVC rapid decliners, the investigators said.

A rapid decline in FEV1 was also associated with a higher stroke risk (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.04-1.50; P = .015).

FEV1 rapid decliners had a higher overall rate of incident cardiovascular disease than those without rapid decline, even after adjustment for baseline variables such as age, sex, race, body mass index, and heart rate (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04-1.26; P = .004), and FVC rapid decliners likewise had a 19% greater risk of the composite endpoint (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32; P less than .001).

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, and other sources supported the study. Dr. Silvestre reported having no relevant conflicts.

SOURCE: Silvestre OM et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1109-22.

Cardiologists and pulmonologists should closely collaborate to better identify the relationship between lung function decline and early cardiovascular disease detection, said the authors of an editorial accompanying the study.

Improved collaboration would help manage these conditions, stopping early disease progression and preventing overt cardiovascular disease, wrote Daniel A. Duprez, MD, PhD, and David R. Jacobs Jr., PhD.

“The resulting symptomatic and prognostic benefits outweigh those attainable by treating either condition alone,” noted Dr. Duprez and Dr. Jacobs.

The study by Dr. Silvestre and coauthors showed that rapid declines in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) among participants in the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study were associated with a higher incidence of composite cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and total death.

The association between FEV1 and new heart failure was substantially impacted by 22 heart failure events occurring in the first year, with a hazard ratio of 4.22 for predicting those cases, the editorial authors noted.

“We suggest that this association with early cases could be the result of reversed causality, reflecting heart failure undiagnosed at the second spirometry test,” they explained (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72[10]:1123-5).

Dr. Duprez is with the cardiovascular division of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Dr. Jacobs is with the division of epidemiology and community health at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Duprez and Dr. Jacobs reported they had no relevant disclosures.

Cardiologists and pulmonologists should closely collaborate to better identify the relationship between lung function decline and early cardiovascular disease detection, said the authors of an editorial accompanying the study.

Improved collaboration would help manage these conditions, stopping early disease progression and preventing overt cardiovascular disease, wrote Daniel A. Duprez, MD, PhD, and David R. Jacobs Jr., PhD.

“The resulting symptomatic and prognostic benefits outweigh those attainable by treating either condition alone,” noted Dr. Duprez and Dr. Jacobs.

The study by Dr. Silvestre and coauthors showed that rapid declines in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) among participants in the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study were associated with a higher incidence of composite cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and total death.

The association between FEV1 and new heart failure was substantially impacted by 22 heart failure events occurring in the first year, with a hazard ratio of 4.22 for predicting those cases, the editorial authors noted.

“We suggest that this association with early cases could be the result of reversed causality, reflecting heart failure undiagnosed at the second spirometry test,” they explained (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72[10]:1123-5).

Dr. Duprez is with the cardiovascular division of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Dr. Jacobs is with the division of epidemiology and community health at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Duprez and Dr. Jacobs reported they had no relevant disclosures.

Cardiologists and pulmonologists should closely collaborate to better identify the relationship between lung function decline and early cardiovascular disease detection, said the authors of an editorial accompanying the study.

Improved collaboration would help manage these conditions, stopping early disease progression and preventing overt cardiovascular disease, wrote Daniel A. Duprez, MD, PhD, and David R. Jacobs Jr., PhD.

“The resulting symptomatic and prognostic benefits outweigh those attainable by treating either condition alone,” noted Dr. Duprez and Dr. Jacobs.

The study by Dr. Silvestre and coauthors showed that rapid declines in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) among participants in the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study were associated with a higher incidence of composite cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and total death.

The association between FEV1 and new heart failure was substantially impacted by 22 heart failure events occurring in the first year, with a hazard ratio of 4.22 for predicting those cases, the editorial authors noted.

“We suggest that this association with early cases could be the result of reversed causality, reflecting heart failure undiagnosed at the second spirometry test,” they explained (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72[10]:1123-5).

Dr. Duprez is with the cardiovascular division of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Dr. Jacobs is with the division of epidemiology and community health at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Dr. Duprez and Dr. Jacobs reported they had no relevant disclosures.

Rapid declines in spirometric measures of lung function were associated with higher risks of cardiovascular disease, according to a recent analysis of a large, prospective cohort study.

Rapid declines in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were associated with increased incidence of heart failure, stroke, and death in the analysis of the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study.

The risk of incident heart failure among FEV1 rapid decliners was particularly high, with a fourfold increase within 12 months. That suggests clinicians should carefully consider incipient heart failure in patients with rapid changes in FEV1, investigators reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Rapid declines in forced vital capacity (FVC) were also associated with higher incidences of heart failure and death in the analysis by Odilson M. Silvestre, MD, of the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

The analysis included a total of 10,351 ARIC participants with a mean follow-up of 17 years. All had undergone spirometry at the first study visit between 1987 and 1989, and on the second visit between 1990 and 1992.

One-quarter of participants were classified as FEV1 rapid decliners, defined by an FEV1 decrease of at least 1.9% per year. Likewise, one-quarter of participants were classified as FVC rapid decliners, based on an FVC decrease of at least 2.1%.

Rapid decline in FEV1 was associated with a higher risk of incident heart failure (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.33; P = .010), and was most prognostic in the first year of follow-up (HR, 4.22; 95% CI, 1.34-13.26; P = .01), investigators said.

Rapid decline in FVC was likewise associated with a greater heart failure risk (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.12-1.44; P less than .001).

Increased heart failure risk persisted after excluding patients with incident coronary heart disease in both the FEV1 and FVC rapid decliners, the investigators said.

A rapid decline in FEV1 was also associated with a higher stroke risk (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.04-1.50; P = .015).

FEV1 rapid decliners had a higher overall rate of incident cardiovascular disease than those without rapid decline, even after adjustment for baseline variables such as age, sex, race, body mass index, and heart rate (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04-1.26; P = .004), and FVC rapid decliners likewise had a 19% greater risk of the composite endpoint (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32; P less than .001).

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, and other sources supported the study. Dr. Silvestre reported having no relevant conflicts.

SOURCE: Silvestre OM et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1109-22.

Rapid declines in spirometric measures of lung function were associated with higher risks of cardiovascular disease, according to a recent analysis of a large, prospective cohort study.

Rapid declines in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were associated with increased incidence of heart failure, stroke, and death in the analysis of the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study.

The risk of incident heart failure among FEV1 rapid decliners was particularly high, with a fourfold increase within 12 months. That suggests clinicians should carefully consider incipient heart failure in patients with rapid changes in FEV1, investigators reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Rapid declines in forced vital capacity (FVC) were also associated with higher incidences of heart failure and death in the analysis by Odilson M. Silvestre, MD, of the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

The analysis included a total of 10,351 ARIC participants with a mean follow-up of 17 years. All had undergone spirometry at the first study visit between 1987 and 1989, and on the second visit between 1990 and 1992.

One-quarter of participants were classified as FEV1 rapid decliners, defined by an FEV1 decrease of at least 1.9% per year. Likewise, one-quarter of participants were classified as FVC rapid decliners, based on an FVC decrease of at least 2.1%.

Rapid decline in FEV1 was associated with a higher risk of incident heart failure (hazard ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.33; P = .010), and was most prognostic in the first year of follow-up (HR, 4.22; 95% CI, 1.34-13.26; P = .01), investigators said.

Rapid decline in FVC was likewise associated with a greater heart failure risk (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.12-1.44; P less than .001).

Increased heart failure risk persisted after excluding patients with incident coronary heart disease in both the FEV1 and FVC rapid decliners, the investigators said.

A rapid decline in FEV1 was also associated with a higher stroke risk (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.04-1.50; P = .015).

FEV1 rapid decliners had a higher overall rate of incident cardiovascular disease than those without rapid decline, even after adjustment for baseline variables such as age, sex, race, body mass index, and heart rate (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04-1.26; P = .004), and FVC rapid decliners likewise had a 19% greater risk of the composite endpoint (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32; P less than .001).

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, and other sources supported the study. Dr. Silvestre reported having no relevant conflicts.

SOURCE: Silvestre OM et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1109-22.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point: Rapid declines in spirometric measures of lung function were associated with higher risks of heart failure, among other adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Major finding: Rapid decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second was associated with higher risk of incident heart failure (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.33; P = .010), and was most prognostic in the first year of follow-up (HR, 4.22; 95% CI, 1.34-13.26; P = .01).

Study details: An analysis including a total of 10,351 participants in a large, prospective cohort study with a mean follow-up of 17 years.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, and other sources supported the study. Dr. Silvestre reported having no relevant conflicts.

Source: Silvestre OM et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1109-22.

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin levels linked to cardiovascular outcomes in COPD patients

, according to a post-hoc analysis of a clinical trial.

An increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events and cardiovascular death was seen in COPD patients in the highest quintile of plasma cardiac troponin concentrations at baseline, results of the analysis show.

The findings highlight the potential utility of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin in both clinical trials and clinical practice, according to researcher Nicholas L. Mills, MD, PhD, BHF/University Centre for Cardiovascular Science, The University of Edinburgh, Scotland, and co-investigators.

“Recognizing the risk associated with increased troponin concentrations might encourage clinicians to address cardiovascular risk due to lifestyle choices, and make patients more likely to engage with these recommendations,” Dr. Mills and co-authors wrote in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Improved risk stratification may also help clinicians more appropriately target the use of preventive medications in COPD patients, they added in the report.

The analysis by Dr. Mills and colleagues was based on assessment of cardiac troponin I concentrations for patients in SUMMIT, a randomized trial assessing inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta agonists in COPD patients with ele-vated cardiovascular risk.

A total of 1,599 patients in the SUMMIT trial had a baseline cardiac troponin I assessment, and 1,258 had a follow-up assessment at 3 months following randomization.

Compared with those in the lowest quintile, patients in the highest quintile of baseline plasma cardiac troponin concentrations had an increased risk of a cardiovascular composite event, even after adjusting for confounding variables (hazard ratio, 3.67; 95% confidence interval, 1.33-10.13; P = .012)..

Increased risk of cardiovascular death was also seen in the highest quintile as compared with the lowest quintile (HR, 20.06; 95% CI, 2.44-165.15; P = .005), investigators said.

There was no difference in risk of COPD exacerbations between the highest and lowest quintiles, they added.

At 3 months, there were no differences in troponin concentrations related to COPD treatment, consistent with previous observations in the SUMMIT trial that treatment did not impact the cardiovascular composite endpoint, investigators said.

However, patients with a plasma troponin of 5 ng/L or greater recorded at either the baseline or 3-month assessment had an increased rate of the composite cardiovascular endpoint and a “markedly increased” risk of cardiovascular death, they wrote.

The research was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and a Butler British Heart Foundation Senior Clinical Research Fellowship received by Dr. Mills. Disclosures reported by Dr. Mills included consultancy, research grants, and speaker fees from Abbott Diagnostics, Roche, and Singulex. Study co-authors reported disclosures related to GlaxoSmithKline, Veramed Limited, AstraZeneca, Zambon, Bayer, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Adamson PD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1126-37.

The current study data are “robust” and suggest a strong association between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin values and cardiovascular event risk in these COPD patients, according to authors of an editorial.

The study also showed that a change in high-sensitivity cardiac troponin at 3 months is associated with increased risk, noted editorial authors Allan S. Jaffe, MD, and H. Ari Jaffe, MD.

“Most of these events probably represent acceleration of atherosclerosis, given the effects of smoking on atherosclerotic disease and its progression,” the authors said in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

However, study authors could have more extensively addressed how to use that information to improve the care of COPD patients at elevated cardiovascular event risk, they added.

A “pilot algorithm” that could be used to apply this biomarker analysis in clinical practice was proposed in an editorial accompanying the research report.

They suggest repeating high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements to reduce variability, as well as repeating samples at 3 months to detect changes that could signal increased risk.

“In addition, one should avoid decisions based on small differences,” they wrote.

Allan S. Jaffe, MD, is with the department of cardiovascular medicine and the department of laboratory medicine and pathology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reported serving as a consultant for Beckman, Abbott, Siemens, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Becton Dickinson, Quindel, and Novartis. H. Ari Jaffe, MD, is with the department of medicine, pulmonary division at University of Illinois at Chicago, Jesse Brown VA Medicine Center, Chicago. He reported he has no relationships to disclose relevant to the contents of the editorial.

The current study data are “robust” and suggest a strong association between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin values and cardiovascular event risk in these COPD patients, according to authors of an editorial.

The study also showed that a change in high-sensitivity cardiac troponin at 3 months is associated with increased risk, noted editorial authors Allan S. Jaffe, MD, and H. Ari Jaffe, MD.

“Most of these events probably represent acceleration of atherosclerosis, given the effects of smoking on atherosclerotic disease and its progression,” the authors said in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

However, study authors could have more extensively addressed how to use that information to improve the care of COPD patients at elevated cardiovascular event risk, they added.

A “pilot algorithm” that could be used to apply this biomarker analysis in clinical practice was proposed in an editorial accompanying the research report.

They suggest repeating high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements to reduce variability, as well as repeating samples at 3 months to detect changes that could signal increased risk.

“In addition, one should avoid decisions based on small differences,” they wrote.

Allan S. Jaffe, MD, is with the department of cardiovascular medicine and the department of laboratory medicine and pathology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reported serving as a consultant for Beckman, Abbott, Siemens, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Becton Dickinson, Quindel, and Novartis. H. Ari Jaffe, MD, is with the department of medicine, pulmonary division at University of Illinois at Chicago, Jesse Brown VA Medicine Center, Chicago. He reported he has no relationships to disclose relevant to the contents of the editorial.

The current study data are “robust” and suggest a strong association between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin values and cardiovascular event risk in these COPD patients, according to authors of an editorial.

The study also showed that a change in high-sensitivity cardiac troponin at 3 months is associated with increased risk, noted editorial authors Allan S. Jaffe, MD, and H. Ari Jaffe, MD.

“Most of these events probably represent acceleration of atherosclerosis, given the effects of smoking on atherosclerotic disease and its progression,” the authors said in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

However, study authors could have more extensively addressed how to use that information to improve the care of COPD patients at elevated cardiovascular event risk, they added.

A “pilot algorithm” that could be used to apply this biomarker analysis in clinical practice was proposed in an editorial accompanying the research report.

They suggest repeating high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements to reduce variability, as well as repeating samples at 3 months to detect changes that could signal increased risk.

“In addition, one should avoid decisions based on small differences,” they wrote.

Allan S. Jaffe, MD, is with the department of cardiovascular medicine and the department of laboratory medicine and pathology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reported serving as a consultant for Beckman, Abbott, Siemens, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Becton Dickinson, Quindel, and Novartis. H. Ari Jaffe, MD, is with the department of medicine, pulmonary division at University of Illinois at Chicago, Jesse Brown VA Medicine Center, Chicago. He reported he has no relationships to disclose relevant to the contents of the editorial.

, according to a post-hoc analysis of a clinical trial.

An increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events and cardiovascular death was seen in COPD patients in the highest quintile of plasma cardiac troponin concentrations at baseline, results of the analysis show.

The findings highlight the potential utility of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin in both clinical trials and clinical practice, according to researcher Nicholas L. Mills, MD, PhD, BHF/University Centre for Cardiovascular Science, The University of Edinburgh, Scotland, and co-investigators.

“Recognizing the risk associated with increased troponin concentrations might encourage clinicians to address cardiovascular risk due to lifestyle choices, and make patients more likely to engage with these recommendations,” Dr. Mills and co-authors wrote in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Improved risk stratification may also help clinicians more appropriately target the use of preventive medications in COPD patients, they added in the report.

The analysis by Dr. Mills and colleagues was based on assessment of cardiac troponin I concentrations for patients in SUMMIT, a randomized trial assessing inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta agonists in COPD patients with ele-vated cardiovascular risk.

A total of 1,599 patients in the SUMMIT trial had a baseline cardiac troponin I assessment, and 1,258 had a follow-up assessment at 3 months following randomization.

Compared with those in the lowest quintile, patients in the highest quintile of baseline plasma cardiac troponin concentrations had an increased risk of a cardiovascular composite event, even after adjusting for confounding variables (hazard ratio, 3.67; 95% confidence interval, 1.33-10.13; P = .012)..

Increased risk of cardiovascular death was also seen in the highest quintile as compared with the lowest quintile (HR, 20.06; 95% CI, 2.44-165.15; P = .005), investigators said.

There was no difference in risk of COPD exacerbations between the highest and lowest quintiles, they added.

At 3 months, there were no differences in troponin concentrations related to COPD treatment, consistent with previous observations in the SUMMIT trial that treatment did not impact the cardiovascular composite endpoint, investigators said.

However, patients with a plasma troponin of 5 ng/L or greater recorded at either the baseline or 3-month assessment had an increased rate of the composite cardiovascular endpoint and a “markedly increased” risk of cardiovascular death, they wrote.

The research was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and a Butler British Heart Foundation Senior Clinical Research Fellowship received by Dr. Mills. Disclosures reported by Dr. Mills included consultancy, research grants, and speaker fees from Abbott Diagnostics, Roche, and Singulex. Study co-authors reported disclosures related to GlaxoSmithKline, Veramed Limited, AstraZeneca, Zambon, Bayer, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Adamson PD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1126-37.

, according to a post-hoc analysis of a clinical trial.

An increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events and cardiovascular death was seen in COPD patients in the highest quintile of plasma cardiac troponin concentrations at baseline, results of the analysis show.

The findings highlight the potential utility of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin in both clinical trials and clinical practice, according to researcher Nicholas L. Mills, MD, PhD, BHF/University Centre for Cardiovascular Science, The University of Edinburgh, Scotland, and co-investigators.

“Recognizing the risk associated with increased troponin concentrations might encourage clinicians to address cardiovascular risk due to lifestyle choices, and make patients more likely to engage with these recommendations,” Dr. Mills and co-authors wrote in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Improved risk stratification may also help clinicians more appropriately target the use of preventive medications in COPD patients, they added in the report.

The analysis by Dr. Mills and colleagues was based on assessment of cardiac troponin I concentrations for patients in SUMMIT, a randomized trial assessing inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta agonists in COPD patients with ele-vated cardiovascular risk.

A total of 1,599 patients in the SUMMIT trial had a baseline cardiac troponin I assessment, and 1,258 had a follow-up assessment at 3 months following randomization.

Compared with those in the lowest quintile, patients in the highest quintile of baseline plasma cardiac troponin concentrations had an increased risk of a cardiovascular composite event, even after adjusting for confounding variables (hazard ratio, 3.67; 95% confidence interval, 1.33-10.13; P = .012)..

Increased risk of cardiovascular death was also seen in the highest quintile as compared with the lowest quintile (HR, 20.06; 95% CI, 2.44-165.15; P = .005), investigators said.

There was no difference in risk of COPD exacerbations between the highest and lowest quintiles, they added.

At 3 months, there were no differences in troponin concentrations related to COPD treatment, consistent with previous observations in the SUMMIT trial that treatment did not impact the cardiovascular composite endpoint, investigators said.

However, patients with a plasma troponin of 5 ng/L or greater recorded at either the baseline or 3-month assessment had an increased rate of the composite cardiovascular endpoint and a “markedly increased” risk of cardiovascular death, they wrote.

The research was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and a Butler British Heart Foundation Senior Clinical Research Fellowship received by Dr. Mills. Disclosures reported by Dr. Mills included consultancy, research grants, and speaker fees from Abbott Diagnostics, Roche, and Singulex. Study co-authors reported disclosures related to GlaxoSmithKline, Veramed Limited, AstraZeneca, Zambon, Bayer, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Adamson PD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1126-37.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point: In patients with COPD and heightened cardiovascular risk, high levels of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin were strongly associated with risk of cardiovascular outcomes.

Major finding: Compared to those in the lowest quintile, patients in the highest quintile of baseline plasma cardiac troponin concentrations had an increased risk of a cardiovascular composite event (hazard ratio, 3.67; 95% CI, 1.33-10.13; P = 0.012).

Study details: Post-hoc analysis of 1,599 patients in the SUMMIT trial who had a baseline cardiac troponin I assessment and 1,258 who had a 3-month follow-up assessment.

Disclosures: The study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline and a Butler British Heart Foundation Senior Clinical Research Fellowship. Authors reported disclosures related to GlaxoSmithKline, Veramed Limited, Abbott Diagnostics, Roche, Singulex, AstraZeneca, Zambon, Bayer, Novartis, and others.

Source: Adamson PD et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 4;72(10):1126-37.

Long-acting beta2 agonists don’t impact cardiovascular risk factors

Neither heart rate nor blood pressure worsened under long-term use of , according to a post hoc pooled analysis published in Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

The study was conducted by Stefan Andreas, MD, department of cardiology and pneumology, University Medical Centre Göttingen, and Lung Clinic Immenhausen, Germany. The analysis evaluated data from four studies and included a total of 3,104 patients with moderate to very severe COPD, which was defined as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 2-4. Patients were randomized to either once-daily olodaterol (5 or 10 mcg), twice-daily formoterol (12 mcg), or placebo. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured before and after dosing at baseline and at four time points during the study: 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 48 weeks.

At all time points, the increases seen in the placebo group were greater than seen in the treatment groups; both systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed either slight decreases from or similarities with those seen at baseline, depending on time point. Furthermore, short-term effects were seen around dosing, from before administration to after, although these changes were quantitatively small.

One limitation of the study is that it couldn’t include patients with unstable COPD because of safety reasons; this prevents the findings from being more broadly generalizable.

“These findings, in a large COPD database, speak against the potential negative cardiovascular effects of olodaterol, as well as those of formoterol,” the researchers concluded.

They reported personal fees from various industry entities, such as Novartis, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. Some also reported receiving personal fees from or working for Boehringer Ingelheim, which funded the work.

SOURCE: Andreas S et al. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2018.08.002.

Neither heart rate nor blood pressure worsened under long-term use of , according to a post hoc pooled analysis published in Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

The study was conducted by Stefan Andreas, MD, department of cardiology and pneumology, University Medical Centre Göttingen, and Lung Clinic Immenhausen, Germany. The analysis evaluated data from four studies and included a total of 3,104 patients with moderate to very severe COPD, which was defined as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 2-4. Patients were randomized to either once-daily olodaterol (5 or 10 mcg), twice-daily formoterol (12 mcg), or placebo. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured before and after dosing at baseline and at four time points during the study: 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 48 weeks.

At all time points, the increases seen in the placebo group were greater than seen in the treatment groups; both systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed either slight decreases from or similarities with those seen at baseline, depending on time point. Furthermore, short-term effects were seen around dosing, from before administration to after, although these changes were quantitatively small.

One limitation of the study is that it couldn’t include patients with unstable COPD because of safety reasons; this prevents the findings from being more broadly generalizable.

“These findings, in a large COPD database, speak against the potential negative cardiovascular effects of olodaterol, as well as those of formoterol,” the researchers concluded.

They reported personal fees from various industry entities, such as Novartis, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. Some also reported receiving personal fees from or working for Boehringer Ingelheim, which funded the work.

SOURCE: Andreas S et al. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2018.08.002.

Neither heart rate nor blood pressure worsened under long-term use of , according to a post hoc pooled analysis published in Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

The study was conducted by Stefan Andreas, MD, department of cardiology and pneumology, University Medical Centre Göttingen, and Lung Clinic Immenhausen, Germany. The analysis evaluated data from four studies and included a total of 3,104 patients with moderate to very severe COPD, which was defined as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 2-4. Patients were randomized to either once-daily olodaterol (5 or 10 mcg), twice-daily formoterol (12 mcg), or placebo. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured before and after dosing at baseline and at four time points during the study: 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 48 weeks.

At all time points, the increases seen in the placebo group were greater than seen in the treatment groups; both systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed either slight decreases from or similarities with those seen at baseline, depending on time point. Furthermore, short-term effects were seen around dosing, from before administration to after, although these changes were quantitatively small.

One limitation of the study is that it couldn’t include patients with unstable COPD because of safety reasons; this prevents the findings from being more broadly generalizable.

“These findings, in a large COPD database, speak against the potential negative cardiovascular effects of olodaterol, as well as those of formoterol,” the researchers concluded.

They reported personal fees from various industry entities, such as Novartis, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. Some also reported receiving personal fees from or working for Boehringer Ingelheim, which funded the work.

SOURCE: Andreas S et al. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2018.08.002.

FROM PULMONARY PHARMACOLOGY & THERAPEUTICS

Key clinical point: Olodaterol and formoterol had a minimal impact on cardiovascular factors.

Major finding: Patients who were randomized to once-daily olodaterol (5 or 10 mcg), twice-daily formoterol (12 mcg), or placebo showed little change in heart rate and blood pressure at 6, 12, 24, or 48 weeks.

Study details: Post hoc pooled analysis from four studies comprising a total of 3,104 patients with moderate to very severe COPD.

Disclosures: Investigators reported personal fees from various industry entities, such as Novartis, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. Some also reported receiving personal fees from or working for Boehringer Ingelheim.

Source: Andreas S et al. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2018.08.002.

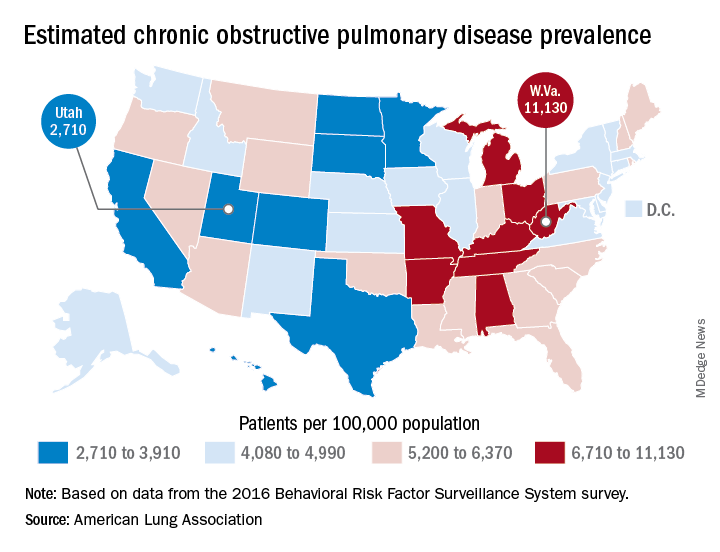

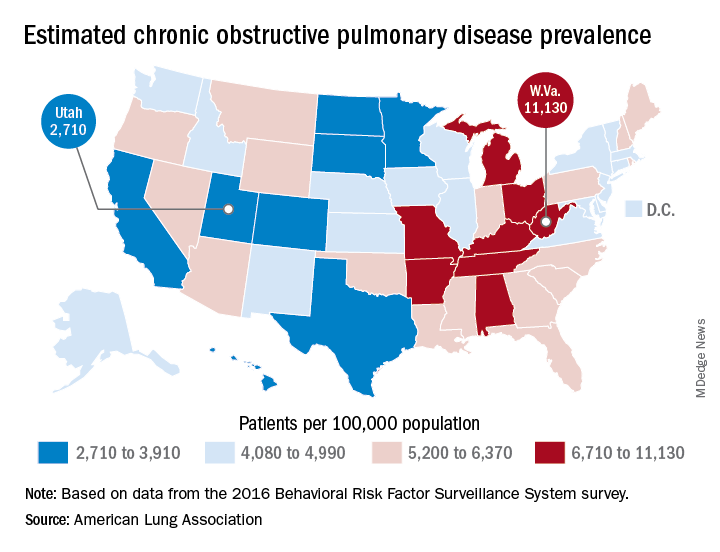

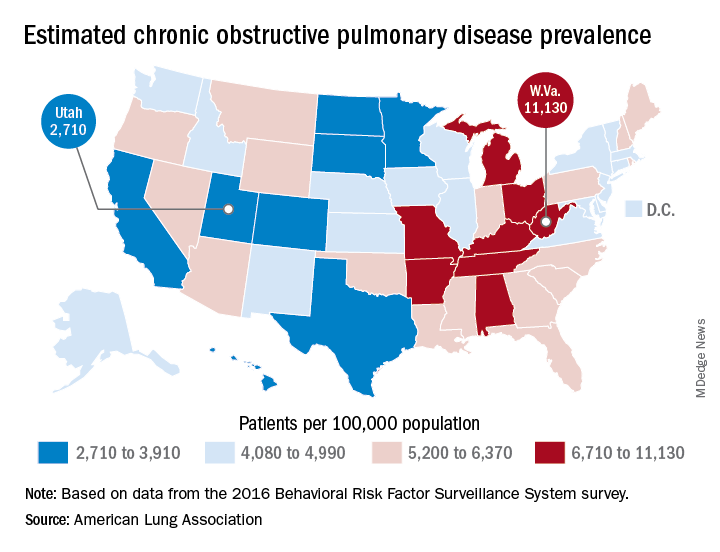

COPD opposites: Utah and West Virginia

New estimates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may have Utah residents breathing a sigh of relief. West Virginians, not so much.

The Beehive State has the lowest prevalence of COPD in the country at 2,710 per 100,000 population, while the Mountain State tops the charts at 11,130 per 100,000, according to estimates from the American Lung Association. (Crude rates were calculated by MDedge News using the ALA’s estimates for total persons with COPD in each state and Census Bureau estimates for population.)

Other states with freer-breathing residents include Minnesota, which was just behind Utah with an estimated rate of 3,000 per 100,000 population, Hawaii (3,182), Colorado (3,334), and California (3,409). West Virginia’s rate, however, seems to be an outlier. The state with the next-highest rate, Kentucky, has a calculated prevalence of 8,890 per 100,000 population, followed by Tennessee at 7,880, Alabama at 7,400, and Arkansas at 7,330, using the ALA’s estimates, which were based on data from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.

New estimates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may have Utah residents breathing a sigh of relief. West Virginians, not so much.

The Beehive State has the lowest prevalence of COPD in the country at 2,710 per 100,000 population, while the Mountain State tops the charts at 11,130 per 100,000, according to estimates from the American Lung Association. (Crude rates were calculated by MDedge News using the ALA’s estimates for total persons with COPD in each state and Census Bureau estimates for population.)

Other states with freer-breathing residents include Minnesota, which was just behind Utah with an estimated rate of 3,000 per 100,000 population, Hawaii (3,182), Colorado (3,334), and California (3,409). West Virginia’s rate, however, seems to be an outlier. The state with the next-highest rate, Kentucky, has a calculated prevalence of 8,890 per 100,000 population, followed by Tennessee at 7,880, Alabama at 7,400, and Arkansas at 7,330, using the ALA’s estimates, which were based on data from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.