User login

No increased complication risk with delaying resection for LARC

CHICAGO – Delaying surgery after neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer for up to 12 weeks does not seem to impact complication rates compared to surgery at 8 weeks or earlier, findings that run counter to results from a major European clinical trial reported in 2016, investigators reported at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“There’s an increasing trend toward delayed surgery beyond eight to 12 weeks after neoadjuvant therapy (NT) for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC),” said Campbell Roxburgh, FRCS, PhD, of the University of Glasgow in Scotland. “Although we saw an increase in all complications in patients who had surgery beyond 12 weeks, there were no increases in surgical site complications, grade 3-5 complications, or anastomotic leaks. Before 12 weeks we did not observe increases in any type of complication where surgery was performed prior to or after 8 weeks.”

The study involved 798 patients who had received NT for LARC from June 2009 to March 2014 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. The vast majority – 76% (607) – had rectal resection within 16 weeks of completing NT. Among them, 52% (317) had surgery 5-8 weeks after NT, 38% (229) had surgery at 8-12 weeks post-NT, and 10% (61) had surgery 12-16 weeks after completing NT. Those who had surgery beyond 16 weeks mostly had it deferred because they were undergoing nonoperative management in the case of complete clinical response to treatment or had a comorbidity that prevented earlier surgery, Dr. Roxburgh said.

The complication rate was 42.3% among the patients who had surgery up to 16 weeks after NT, Dr. Roxburgh said. The most common complication was surgical site infection (SSI) in 16.6% (101), followed by a grade 3-5 complication in 10.5% (64) and anastomotic leak in 6.4% (39). Overall complication rates among the two groups that had surgery within 12 weeks were not statistically different from the overall complication rate, Dr. Roxburgh said: 42.5% (138) in the 5- to 8-week group; and 36.7% (84) in the 8- to 12-week group. The 12- to16-week group had a complication rate of 56% (34, P = .022).

Dr. Roxburgh noted that the idea of delaying surgery beyond 8 weeks after NT has been a subject of debate, and that these findings run counter to those reported in the GRECCAR-6 trial (J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3773-80). That study compared groups that had surgery for rectal cancer at 7 and 11 weeks after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and found that those in the 11-week group had higher rates of complications.

Dr. Roxburgh also reported on an analysis of the 12- to 16-week subgroup that found the highest complication rates were among those who had low anterior resection (53% vs. 41% in the 5- to 8-week group and 31% in the 8- to 12-week population), and patients who had a poor treatment response (no T-downstaging, 66% vs. 44% and 33%, respectively). Age, pretreatment and posttreatment TNM stages, surgical approach (open or minimally invasive), and year of treatment did not factor in complication rates in the subgroup analysis, Dr. Roxburgh noted.

The univariate regression analysis determined a trend toward increased rates of all complications in the 12- to 16-week group (P = .081). But the multivariate analysis did not find timing of surgery to be an independent risk factor for all complications, Dr. Roxburgh said. “We believe other factors, including tumor location, the type of NT, operative approach, and treatment response, however, were more important on multivariate analysis,” he said. For example, open surgery had an odds ratio of 1.7 (P = .004).

During the discussion, Dr. Roxburgh was asked what would be the optimal timing for resection after NT in LARC. “I would recommend posttreatment assessment with MRI and proctoscopy between 8 to 12 weeks and in the case of residual tumor or incomplete response to treatment, scheduling surgery at that time,” he said.

Dr. Roxburgh and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Roxburgh C, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium Abstract No. 3.

CHICAGO – Delaying surgery after neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer for up to 12 weeks does not seem to impact complication rates compared to surgery at 8 weeks or earlier, findings that run counter to results from a major European clinical trial reported in 2016, investigators reported at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“There’s an increasing trend toward delayed surgery beyond eight to 12 weeks after neoadjuvant therapy (NT) for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC),” said Campbell Roxburgh, FRCS, PhD, of the University of Glasgow in Scotland. “Although we saw an increase in all complications in patients who had surgery beyond 12 weeks, there were no increases in surgical site complications, grade 3-5 complications, or anastomotic leaks. Before 12 weeks we did not observe increases in any type of complication where surgery was performed prior to or after 8 weeks.”

The study involved 798 patients who had received NT for LARC from June 2009 to March 2014 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. The vast majority – 76% (607) – had rectal resection within 16 weeks of completing NT. Among them, 52% (317) had surgery 5-8 weeks after NT, 38% (229) had surgery at 8-12 weeks post-NT, and 10% (61) had surgery 12-16 weeks after completing NT. Those who had surgery beyond 16 weeks mostly had it deferred because they were undergoing nonoperative management in the case of complete clinical response to treatment or had a comorbidity that prevented earlier surgery, Dr. Roxburgh said.

The complication rate was 42.3% among the patients who had surgery up to 16 weeks after NT, Dr. Roxburgh said. The most common complication was surgical site infection (SSI) in 16.6% (101), followed by a grade 3-5 complication in 10.5% (64) and anastomotic leak in 6.4% (39). Overall complication rates among the two groups that had surgery within 12 weeks were not statistically different from the overall complication rate, Dr. Roxburgh said: 42.5% (138) in the 5- to 8-week group; and 36.7% (84) in the 8- to 12-week group. The 12- to16-week group had a complication rate of 56% (34, P = .022).

Dr. Roxburgh noted that the idea of delaying surgery beyond 8 weeks after NT has been a subject of debate, and that these findings run counter to those reported in the GRECCAR-6 trial (J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3773-80). That study compared groups that had surgery for rectal cancer at 7 and 11 weeks after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and found that those in the 11-week group had higher rates of complications.

Dr. Roxburgh also reported on an analysis of the 12- to 16-week subgroup that found the highest complication rates were among those who had low anterior resection (53% vs. 41% in the 5- to 8-week group and 31% in the 8- to 12-week population), and patients who had a poor treatment response (no T-downstaging, 66% vs. 44% and 33%, respectively). Age, pretreatment and posttreatment TNM stages, surgical approach (open or minimally invasive), and year of treatment did not factor in complication rates in the subgroup analysis, Dr. Roxburgh noted.

The univariate regression analysis determined a trend toward increased rates of all complications in the 12- to 16-week group (P = .081). But the multivariate analysis did not find timing of surgery to be an independent risk factor for all complications, Dr. Roxburgh said. “We believe other factors, including tumor location, the type of NT, operative approach, and treatment response, however, were more important on multivariate analysis,” he said. For example, open surgery had an odds ratio of 1.7 (P = .004).

During the discussion, Dr. Roxburgh was asked what would be the optimal timing for resection after NT in LARC. “I would recommend posttreatment assessment with MRI and proctoscopy between 8 to 12 weeks and in the case of residual tumor or incomplete response to treatment, scheduling surgery at that time,” he said.

Dr. Roxburgh and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Roxburgh C, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium Abstract No. 3.

CHICAGO – Delaying surgery after neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer for up to 12 weeks does not seem to impact complication rates compared to surgery at 8 weeks or earlier, findings that run counter to results from a major European clinical trial reported in 2016, investigators reported at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“There’s an increasing trend toward delayed surgery beyond eight to 12 weeks after neoadjuvant therapy (NT) for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC),” said Campbell Roxburgh, FRCS, PhD, of the University of Glasgow in Scotland. “Although we saw an increase in all complications in patients who had surgery beyond 12 weeks, there were no increases in surgical site complications, grade 3-5 complications, or anastomotic leaks. Before 12 weeks we did not observe increases in any type of complication where surgery was performed prior to or after 8 weeks.”

The study involved 798 patients who had received NT for LARC from June 2009 to March 2014 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. The vast majority – 76% (607) – had rectal resection within 16 weeks of completing NT. Among them, 52% (317) had surgery 5-8 weeks after NT, 38% (229) had surgery at 8-12 weeks post-NT, and 10% (61) had surgery 12-16 weeks after completing NT. Those who had surgery beyond 16 weeks mostly had it deferred because they were undergoing nonoperative management in the case of complete clinical response to treatment or had a comorbidity that prevented earlier surgery, Dr. Roxburgh said.

The complication rate was 42.3% among the patients who had surgery up to 16 weeks after NT, Dr. Roxburgh said. The most common complication was surgical site infection (SSI) in 16.6% (101), followed by a grade 3-5 complication in 10.5% (64) and anastomotic leak in 6.4% (39). Overall complication rates among the two groups that had surgery within 12 weeks were not statistically different from the overall complication rate, Dr. Roxburgh said: 42.5% (138) in the 5- to 8-week group; and 36.7% (84) in the 8- to 12-week group. The 12- to16-week group had a complication rate of 56% (34, P = .022).

Dr. Roxburgh noted that the idea of delaying surgery beyond 8 weeks after NT has been a subject of debate, and that these findings run counter to those reported in the GRECCAR-6 trial (J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3773-80). That study compared groups that had surgery for rectal cancer at 7 and 11 weeks after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and found that those in the 11-week group had higher rates of complications.

Dr. Roxburgh also reported on an analysis of the 12- to 16-week subgroup that found the highest complication rates were among those who had low anterior resection (53% vs. 41% in the 5- to 8-week group and 31% in the 8- to 12-week population), and patients who had a poor treatment response (no T-downstaging, 66% vs. 44% and 33%, respectively). Age, pretreatment and posttreatment TNM stages, surgical approach (open or minimally invasive), and year of treatment did not factor in complication rates in the subgroup analysis, Dr. Roxburgh noted.

The univariate regression analysis determined a trend toward increased rates of all complications in the 12- to 16-week group (P = .081). But the multivariate analysis did not find timing of surgery to be an independent risk factor for all complications, Dr. Roxburgh said. “We believe other factors, including tumor location, the type of NT, operative approach, and treatment response, however, were more important on multivariate analysis,” he said. For example, open surgery had an odds ratio of 1.7 (P = .004).

During the discussion, Dr. Roxburgh was asked what would be the optimal timing for resection after NT in LARC. “I would recommend posttreatment assessment with MRI and proctoscopy between 8 to 12 weeks and in the case of residual tumor or incomplete response to treatment, scheduling surgery at that time,” he said.

Dr. Roxburgh and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Roxburgh C, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium Abstract No. 3.

REPORTING FROM SSO 2018

Key clinical point: Timing of surgery for rectal cancer within 12 weeks of neoadjuvant therapy does not influence complications.

Major finding: Complication rates in early and later surgery groups were 44% and 38%.

Study details: Institutional cohort of 607 patients who had rectal resection within 16 weeks of completing NT between June 2009 and March 2015.

Disclosure: Dr. Roxburgh and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Roxburgh C, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium Abstract No. 3.

Tumor Lysis Syndrome in Colon Cancer

Clinicians at Centro Hospitalar do Porto in Portugal reported on the case to highlight risk factors for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). After 3 cycles of folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), the patient developed nausea, mild asthenia, tremors, and hyperkalemia that did not respond to standard measures. The differential diagnosis included dehydration, hypotension, exposure to nephrotoxic drugs, and obstructive uropathy, as well as TLS. The patient was diagnosed with acute kidney injury and TLS.

Tumor lysis syndrome is common after the beginning of antineoplastic treatments. As massive amounts of tumor cells are killed, intracellular electrolytes and metabolites flood into the bloodstream. If the metabolites exceed the renal clearance threshold, serious complications ensue, including cardiac arrhythmias or seizures and death. Mortality rates related to TLS in solid tumors can be as high as 35%, the clinicians say. Acute kidney injury during chemotherapy should raise warning flags about TLS, they add, particularly because prompt diagnosis is crucial for short-term outcomes.

The patient was admitted immediately to the intensive care unit with the main aim of preventing severe cardiac events and reversing crystal nephropathy. Adding targeted therapy might have worsened the TLS, so the clinicians opted for high-risk prophylaxis. They advise having rasburicase readily available for treating TLS to degrade urate crystals and reverse nephropathy, reducing the need for renal replacement therapy. However, the clinicians caution that rasburicase and allopurinol (another option) are not free of toxicity.

After a reevaluation computer tomography scan showed that the hepatomegaly was reduced with smaller liver metastases, the clinicians switched the patient to low-risk prophylaxis. The TLS did not recur.

Chemosensitivity, which raises the risk of TLS, is low in colon cancer, the clinicians say. High tumor burden and high proliferation rates seem to be better predictors for TLS.

Source:

Gouveia HS, Lopes SO, Faria AL. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. pii: bcr-2017-223474.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223474.

Clinicians at Centro Hospitalar do Porto in Portugal reported on the case to highlight risk factors for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). After 3 cycles of folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), the patient developed nausea, mild asthenia, tremors, and hyperkalemia that did not respond to standard measures. The differential diagnosis included dehydration, hypotension, exposure to nephrotoxic drugs, and obstructive uropathy, as well as TLS. The patient was diagnosed with acute kidney injury and TLS.

Tumor lysis syndrome is common after the beginning of antineoplastic treatments. As massive amounts of tumor cells are killed, intracellular electrolytes and metabolites flood into the bloodstream. If the metabolites exceed the renal clearance threshold, serious complications ensue, including cardiac arrhythmias or seizures and death. Mortality rates related to TLS in solid tumors can be as high as 35%, the clinicians say. Acute kidney injury during chemotherapy should raise warning flags about TLS, they add, particularly because prompt diagnosis is crucial for short-term outcomes.

The patient was admitted immediately to the intensive care unit with the main aim of preventing severe cardiac events and reversing crystal nephropathy. Adding targeted therapy might have worsened the TLS, so the clinicians opted for high-risk prophylaxis. They advise having rasburicase readily available for treating TLS to degrade urate crystals and reverse nephropathy, reducing the need for renal replacement therapy. However, the clinicians caution that rasburicase and allopurinol (another option) are not free of toxicity.

After a reevaluation computer tomography scan showed that the hepatomegaly was reduced with smaller liver metastases, the clinicians switched the patient to low-risk prophylaxis. The TLS did not recur.

Chemosensitivity, which raises the risk of TLS, is low in colon cancer, the clinicians say. High tumor burden and high proliferation rates seem to be better predictors for TLS.

Source:

Gouveia HS, Lopes SO, Faria AL. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. pii: bcr-2017-223474.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223474.

Clinicians at Centro Hospitalar do Porto in Portugal reported on the case to highlight risk factors for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). After 3 cycles of folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), the patient developed nausea, mild asthenia, tremors, and hyperkalemia that did not respond to standard measures. The differential diagnosis included dehydration, hypotension, exposure to nephrotoxic drugs, and obstructive uropathy, as well as TLS. The patient was diagnosed with acute kidney injury and TLS.

Tumor lysis syndrome is common after the beginning of antineoplastic treatments. As massive amounts of tumor cells are killed, intracellular electrolytes and metabolites flood into the bloodstream. If the metabolites exceed the renal clearance threshold, serious complications ensue, including cardiac arrhythmias or seizures and death. Mortality rates related to TLS in solid tumors can be as high as 35%, the clinicians say. Acute kidney injury during chemotherapy should raise warning flags about TLS, they add, particularly because prompt diagnosis is crucial for short-term outcomes.

The patient was admitted immediately to the intensive care unit with the main aim of preventing severe cardiac events and reversing crystal nephropathy. Adding targeted therapy might have worsened the TLS, so the clinicians opted for high-risk prophylaxis. They advise having rasburicase readily available for treating TLS to degrade urate crystals and reverse nephropathy, reducing the need for renal replacement therapy. However, the clinicians caution that rasburicase and allopurinol (another option) are not free of toxicity.

After a reevaluation computer tomography scan showed that the hepatomegaly was reduced with smaller liver metastases, the clinicians switched the patient to low-risk prophylaxis. The TLS did not recur.

Chemosensitivity, which raises the risk of TLS, is low in colon cancer, the clinicians say. High tumor burden and high proliferation rates seem to be better predictors for TLS.

Source:

Gouveia HS, Lopes SO, Faria AL. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. pii: bcr-2017-223474.

doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223474.

Accuracy of colon cancer lymph node sampling influenced by location

CHICAGO – Clinical guidelines recommend , but those guidelines may need to be revised to take into account which side the cancer is on to accurately stage a subset of patients with colon cancer, according to results of a prospective, multicenter clinical trial presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

Ahmed Dehal, MD, of John Wayne Canter Institute in Santa Monica, Calif., presented results of the trial that compared nodal staging in right-sided vs. left-sided colon cancer in two cohorts with T3N0 colon cancer who had at least one lymph node examined: a group of 370 patients from the randomized, multicenter prospective trial; and a sampling of 153,945 patients in the National Cancer Database (NCDB). The latter was used to validate findings in the trial group.

The probability of achieving true nodal negativity when 12 lymph nodes were examined was 64% for left and 68% for right colon cancer in the trial group and 72% and 77% in the NCDB cohort, Dr. Dehal said.

The analysis also examined how many nodes would need to be sampled to achieve probabilities of 85%, 90% and 95% true nodal negativity. This analysis found the numbers were consistently lower for right- vs. left-sided disease, Dr. Dehal said. For example, in the trial cohort, 27 lymph nodes would need be sampled in right-sided disease to achieve 85% probability vs. 31 in left-sided. In the NCDB cohort, those numbers were 21 and 25, respectively.

“The current threshold for adequate nodal sampling does not reliably predict the true nodal negativity in this subgroup of patients,” Dr. Dehal said. “In both cohorts – the trial and NCDB – more lymph nodes are needed to predict the true nodal negativity in patients with left compared to right colon cancer.”

These findings may help to inform revisions to existing clinical guidelines, Dr. Dehal said.

“Current guidelines regarding the minimum number of nodes needed to accurately stage patients with node-negative T3 colon cancer may need to be reevaluated given that the decision to give those patients chemotherapy is largely based on the nodal status,” he said. “More studies are needed to improve our understanding of the impact of sidedness on nodal staging in the colon cancer.”

Dr. Dehal and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dehal A et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium. Abstract #23: Accuracy of nodal staging is influenced by sidedness in colon cancer: Results of a multicenter prospective trial.

*CORRECTION, 4/4/2018; a previous version of this story misidentified the cancer type

CHICAGO – Clinical guidelines recommend , but those guidelines may need to be revised to take into account which side the cancer is on to accurately stage a subset of patients with colon cancer, according to results of a prospective, multicenter clinical trial presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

Ahmed Dehal, MD, of John Wayne Canter Institute in Santa Monica, Calif., presented results of the trial that compared nodal staging in right-sided vs. left-sided colon cancer in two cohorts with T3N0 colon cancer who had at least one lymph node examined: a group of 370 patients from the randomized, multicenter prospective trial; and a sampling of 153,945 patients in the National Cancer Database (NCDB). The latter was used to validate findings in the trial group.

The probability of achieving true nodal negativity when 12 lymph nodes were examined was 64% for left and 68% for right colon cancer in the trial group and 72% and 77% in the NCDB cohort, Dr. Dehal said.

The analysis also examined how many nodes would need to be sampled to achieve probabilities of 85%, 90% and 95% true nodal negativity. This analysis found the numbers were consistently lower for right- vs. left-sided disease, Dr. Dehal said. For example, in the trial cohort, 27 lymph nodes would need be sampled in right-sided disease to achieve 85% probability vs. 31 in left-sided. In the NCDB cohort, those numbers were 21 and 25, respectively.

“The current threshold for adequate nodal sampling does not reliably predict the true nodal negativity in this subgroup of patients,” Dr. Dehal said. “In both cohorts – the trial and NCDB – more lymph nodes are needed to predict the true nodal negativity in patients with left compared to right colon cancer.”

These findings may help to inform revisions to existing clinical guidelines, Dr. Dehal said.

“Current guidelines regarding the minimum number of nodes needed to accurately stage patients with node-negative T3 colon cancer may need to be reevaluated given that the decision to give those patients chemotherapy is largely based on the nodal status,” he said. “More studies are needed to improve our understanding of the impact of sidedness on nodal staging in the colon cancer.”

Dr. Dehal and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dehal A et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium. Abstract #23: Accuracy of nodal staging is influenced by sidedness in colon cancer: Results of a multicenter prospective trial.

*CORRECTION, 4/4/2018; a previous version of this story misidentified the cancer type

CHICAGO – Clinical guidelines recommend , but those guidelines may need to be revised to take into account which side the cancer is on to accurately stage a subset of patients with colon cancer, according to results of a prospective, multicenter clinical trial presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

Ahmed Dehal, MD, of John Wayne Canter Institute in Santa Monica, Calif., presented results of the trial that compared nodal staging in right-sided vs. left-sided colon cancer in two cohorts with T3N0 colon cancer who had at least one lymph node examined: a group of 370 patients from the randomized, multicenter prospective trial; and a sampling of 153,945 patients in the National Cancer Database (NCDB). The latter was used to validate findings in the trial group.

The probability of achieving true nodal negativity when 12 lymph nodes were examined was 64% for left and 68% for right colon cancer in the trial group and 72% and 77% in the NCDB cohort, Dr. Dehal said.

The analysis also examined how many nodes would need to be sampled to achieve probabilities of 85%, 90% and 95% true nodal negativity. This analysis found the numbers were consistently lower for right- vs. left-sided disease, Dr. Dehal said. For example, in the trial cohort, 27 lymph nodes would need be sampled in right-sided disease to achieve 85% probability vs. 31 in left-sided. In the NCDB cohort, those numbers were 21 and 25, respectively.

“The current threshold for adequate nodal sampling does not reliably predict the true nodal negativity in this subgroup of patients,” Dr. Dehal said. “In both cohorts – the trial and NCDB – more lymph nodes are needed to predict the true nodal negativity in patients with left compared to right colon cancer.”

These findings may help to inform revisions to existing clinical guidelines, Dr. Dehal said.

“Current guidelines regarding the minimum number of nodes needed to accurately stage patients with node-negative T3 colon cancer may need to be reevaluated given that the decision to give those patients chemotherapy is largely based on the nodal status,” he said. “More studies are needed to improve our understanding of the impact of sidedness on nodal staging in the colon cancer.”

Dr. Dehal and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dehal A et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium. Abstract #23: Accuracy of nodal staging is influenced by sidedness in colon cancer: Results of a multicenter prospective trial.

*CORRECTION, 4/4/2018; a previous version of this story misidentified the cancer type

REPORTING FROM SSO 2018

Key clinical point: Sidedness influences the number of lymph nodes needed to predict true nodal negativity in colon cancer.

Major finding: Probability of true nodal negativity when 12 lymph nodes were examined was 64% for left and 68% for right colon cancer.

Study details: Randomized, multicenter trial of ultrastaging in colon cancer in 370 patients and National Cancer Database sampling of 153,945 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Dehal and his coauthors report having no financial disclosures.

Source: Dehal A et al. Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium, Abstract 23: Accuracy of nodal staging is influenced by sidedness in colon cancer: Results of a multicenter prospective trial.

VIDEO: Organ-sparing resection techniques should be way of the future

BOSTON – Organ-sparing resection techniques that remove lesions from the esophagus, stomach, and colon are being developed, Amrita Sethi, MD, said in a video interview at the 2018 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

Dr. Sethi, an assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said these techniques improve patient outcomes by maintaining organ integrity, whereas older techniques often led to removal of large amounts of tissue around lesions. And while organ-sparing techniques reduce recovery time and hospital stays, training and reimbursement for these procedures remain problematic. As much as new endoscopic package devices are needed from industry to make these procedures easier, automated or artificial intelligence is needed to help make the decisions on when these techniques are applicable. Reimbursement structures are needed so that these procedures make financial sense, she noted.

We live in a health care system now, Dr. Sethi said, in which benign polyps of the colon are being sent for surgical resection when what is really needed is referral for more advanced endoscopic treatment. This is a matter of training, and perhaps showing through comparative trials that organ-sparing techniques cost less and improve patient outcomes.

BOSTON – Organ-sparing resection techniques that remove lesions from the esophagus, stomach, and colon are being developed, Amrita Sethi, MD, said in a video interview at the 2018 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

Dr. Sethi, an assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said these techniques improve patient outcomes by maintaining organ integrity, whereas older techniques often led to removal of large amounts of tissue around lesions. And while organ-sparing techniques reduce recovery time and hospital stays, training and reimbursement for these procedures remain problematic. As much as new endoscopic package devices are needed from industry to make these procedures easier, automated or artificial intelligence is needed to help make the decisions on when these techniques are applicable. Reimbursement structures are needed so that these procedures make financial sense, she noted.

We live in a health care system now, Dr. Sethi said, in which benign polyps of the colon are being sent for surgical resection when what is really needed is referral for more advanced endoscopic treatment. This is a matter of training, and perhaps showing through comparative trials that organ-sparing techniques cost less and improve patient outcomes.

BOSTON – Organ-sparing resection techniques that remove lesions from the esophagus, stomach, and colon are being developed, Amrita Sethi, MD, said in a video interview at the 2018 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

Dr. Sethi, an assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said these techniques improve patient outcomes by maintaining organ integrity, whereas older techniques often led to removal of large amounts of tissue around lesions. And while organ-sparing techniques reduce recovery time and hospital stays, training and reimbursement for these procedures remain problematic. As much as new endoscopic package devices are needed from industry to make these procedures easier, automated or artificial intelligence is needed to help make the decisions on when these techniques are applicable. Reimbursement structures are needed so that these procedures make financial sense, she noted.

We live in a health care system now, Dr. Sethi said, in which benign polyps of the colon are being sent for surgical resection when what is really needed is referral for more advanced endoscopic treatment. This is a matter of training, and perhaps showing through comparative trials that organ-sparing techniques cost less and improve patient outcomes.

REPORTING FROM 2018 AGA TECH SUMMIT

Nonendoscopic nonmalignant polyp surgery increasing despite greater risk

Rate of nonendoscopic surgeries for nonmalignant colorectal polyps significantly increased from 5.9 to 9.4 per 100,000 people from 2000 to 2014, according to a study in Gastroenterology.

These surgeries are not only associated with a much higher risk to patients than endoscopic procedures, but they are significantly less cost effective, confusing investigators as to the cause of the increase.

“The literature to date is clear that endoscopic resection is the preferred management of nonmalignant colorectal polyps,” Anne Peery, MD, gastroenterologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and colleagues explained. “Among patients who have surgery for a nonmalignant colorectal polyp, 14% will have at least one major short-term postoperative event.”

Data from 1,230,458 surgeries conducted during 2000-2014 and recorded in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatients Sample were included in this study. Patients who underwent a nonendoscopic procedure for nonmalignant polyps were predominantly non-Hispanic white, covered by Medicare, from the highest household income range, and an average age of 66 years.

While non-Hispanic white patients had the highest overall rate increase by ethnicity, rising from 5.6 to 10.5 per 100,000 population, rates in non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients also rose significantly, increasing from 3.5 to 5.8 per 100,000 population, and from 1.1 to 3.7 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Regionally, rates of surgery were higher in the Midwest (10.8 per 100,000) and the South (10.6 per 100,000) than in the Northeast (7.8 per 100,000) and West (7.5 per 100,000). Incidence rates rose equally during the study period for both men and women.

Large urban teaching hospitals were found to have the largest rate increase when data were stratified by teaching status, a finding which caught Dr. Peery and fellow investigators by surprise.

“We had hypothesized that surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps would be both uncommon and declining in teaching hospitals where providers are more likely to be familiar with current guidelines and to have access to endoscopic mucosal resection,” wrote the investigators. “Instead, we found that surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps is both common and significantly increasing in teaching hospitals.”

The investigators first hypothesized the increased rate in teaching hospitals could be due to a higher concentration of case referrals to these high-volume centers, following a trend of centralizing cancer procedures. However, there has been no other sign that colon and rectal cancer procedures are following this trend.

Another option considered by Dr. Peery and her colleagues was that increased procedures may stem from a rise in colorectal cancer screening; however, the data indicate screenings did not change from 2010 to 2015, leaving investigators with few final guesses to go on.

“It is also conceivable that increasing production pressure and inadequate reimbursement for endoscopic mucosal resection may persuade endoscopists to refer patients with complex nonmalignant colorectal polyps for surgery,” said Dr. Peery and fellow investigators. “Finally, there is the issue of risk ... for endoscopists without additional training in advanced endoscopic resection, these risks may be perceived as too great, especially when they have the option of referring for a surgical resection.”

There is a possibility that the incidence of surgery was over- or underestimated, as investigators were using ICD-9 codes to identify cases, and patients with diverticulitis were also excluded, which may have affected results.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peery A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.003.

In this comprehensive analysis, Peery et al. found a rising incidence of surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps despite relatively stable colorectal cancer screening rates and with decreasing incidence of colorectal cancer surgery.

In a separate study, the authors found that 14% of patients who underwent surgical resection of nonmalignant colorectal polyps had a major postoperative event. Other population-based studies have reported similar incidence of surgical complications.

This report thus raises concern for inappropriate surgical referral. While reimbursement models may play a role, many factors are involved with surgical referral. Complex polypectomy, often using endoscopic mucosal resection techniques to remove large polyps, is associated with higher rates of bleeding, perforation, and incomplete resection, compared with standard polypectomies. The decision to refer to surgery or to attempt endoscopic resection is based on provider experience and polyp characteristics, including suspicion for malignancy. Current literature suggests that surgical removal is recommended less frequently by specialists in complex polypectomy, compared with nonspecialists.

Given this study’s findings, health systems should consider including surgical referral rates in their quality measures. Thus, high-quality endoscopy centers would ensure that complex polyps are appropriately characterized and initially managed by endoscopists experienced in complex polypectomy. This is especially important with the increasing repertoire of endoscopic alternatives to surgery that we can offer our patients.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an an assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no conflicts.

In this comprehensive analysis, Peery et al. found a rising incidence of surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps despite relatively stable colorectal cancer screening rates and with decreasing incidence of colorectal cancer surgery.

In a separate study, the authors found that 14% of patients who underwent surgical resection of nonmalignant colorectal polyps had a major postoperative event. Other population-based studies have reported similar incidence of surgical complications.

This report thus raises concern for inappropriate surgical referral. While reimbursement models may play a role, many factors are involved with surgical referral. Complex polypectomy, often using endoscopic mucosal resection techniques to remove large polyps, is associated with higher rates of bleeding, perforation, and incomplete resection, compared with standard polypectomies. The decision to refer to surgery or to attempt endoscopic resection is based on provider experience and polyp characteristics, including suspicion for malignancy. Current literature suggests that surgical removal is recommended less frequently by specialists in complex polypectomy, compared with nonspecialists.

Given this study’s findings, health systems should consider including surgical referral rates in their quality measures. Thus, high-quality endoscopy centers would ensure that complex polyps are appropriately characterized and initially managed by endoscopists experienced in complex polypectomy. This is especially important with the increasing repertoire of endoscopic alternatives to surgery that we can offer our patients.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an an assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no conflicts.

In this comprehensive analysis, Peery et al. found a rising incidence of surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps despite relatively stable colorectal cancer screening rates and with decreasing incidence of colorectal cancer surgery.

In a separate study, the authors found that 14% of patients who underwent surgical resection of nonmalignant colorectal polyps had a major postoperative event. Other population-based studies have reported similar incidence of surgical complications.

This report thus raises concern for inappropriate surgical referral. While reimbursement models may play a role, many factors are involved with surgical referral. Complex polypectomy, often using endoscopic mucosal resection techniques to remove large polyps, is associated with higher rates of bleeding, perforation, and incomplete resection, compared with standard polypectomies. The decision to refer to surgery or to attempt endoscopic resection is based on provider experience and polyp characteristics, including suspicion for malignancy. Current literature suggests that surgical removal is recommended less frequently by specialists in complex polypectomy, compared with nonspecialists.

Given this study’s findings, health systems should consider including surgical referral rates in their quality measures. Thus, high-quality endoscopy centers would ensure that complex polyps are appropriately characterized and initially managed by endoscopists experienced in complex polypectomy. This is especially important with the increasing repertoire of endoscopic alternatives to surgery that we can offer our patients.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an an assistant professor, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no conflicts.

Rate of nonendoscopic surgeries for nonmalignant colorectal polyps significantly increased from 5.9 to 9.4 per 100,000 people from 2000 to 2014, according to a study in Gastroenterology.

These surgeries are not only associated with a much higher risk to patients than endoscopic procedures, but they are significantly less cost effective, confusing investigators as to the cause of the increase.

“The literature to date is clear that endoscopic resection is the preferred management of nonmalignant colorectal polyps,” Anne Peery, MD, gastroenterologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and colleagues explained. “Among patients who have surgery for a nonmalignant colorectal polyp, 14% will have at least one major short-term postoperative event.”

Data from 1,230,458 surgeries conducted during 2000-2014 and recorded in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatients Sample were included in this study. Patients who underwent a nonendoscopic procedure for nonmalignant polyps were predominantly non-Hispanic white, covered by Medicare, from the highest household income range, and an average age of 66 years.

While non-Hispanic white patients had the highest overall rate increase by ethnicity, rising from 5.6 to 10.5 per 100,000 population, rates in non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients also rose significantly, increasing from 3.5 to 5.8 per 100,000 population, and from 1.1 to 3.7 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Regionally, rates of surgery were higher in the Midwest (10.8 per 100,000) and the South (10.6 per 100,000) than in the Northeast (7.8 per 100,000) and West (7.5 per 100,000). Incidence rates rose equally during the study period for both men and women.

Large urban teaching hospitals were found to have the largest rate increase when data were stratified by teaching status, a finding which caught Dr. Peery and fellow investigators by surprise.

“We had hypothesized that surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps would be both uncommon and declining in teaching hospitals where providers are more likely to be familiar with current guidelines and to have access to endoscopic mucosal resection,” wrote the investigators. “Instead, we found that surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps is both common and significantly increasing in teaching hospitals.”

The investigators first hypothesized the increased rate in teaching hospitals could be due to a higher concentration of case referrals to these high-volume centers, following a trend of centralizing cancer procedures. However, there has been no other sign that colon and rectal cancer procedures are following this trend.

Another option considered by Dr. Peery and her colleagues was that increased procedures may stem from a rise in colorectal cancer screening; however, the data indicate screenings did not change from 2010 to 2015, leaving investigators with few final guesses to go on.

“It is also conceivable that increasing production pressure and inadequate reimbursement for endoscopic mucosal resection may persuade endoscopists to refer patients with complex nonmalignant colorectal polyps for surgery,” said Dr. Peery and fellow investigators. “Finally, there is the issue of risk ... for endoscopists without additional training in advanced endoscopic resection, these risks may be perceived as too great, especially when they have the option of referring for a surgical resection.”

There is a possibility that the incidence of surgery was over- or underestimated, as investigators were using ICD-9 codes to identify cases, and patients with diverticulitis were also excluded, which may have affected results.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peery A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.003.

Rate of nonendoscopic surgeries for nonmalignant colorectal polyps significantly increased from 5.9 to 9.4 per 100,000 people from 2000 to 2014, according to a study in Gastroenterology.

These surgeries are not only associated with a much higher risk to patients than endoscopic procedures, but they are significantly less cost effective, confusing investigators as to the cause of the increase.

“The literature to date is clear that endoscopic resection is the preferred management of nonmalignant colorectal polyps,” Anne Peery, MD, gastroenterologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and colleagues explained. “Among patients who have surgery for a nonmalignant colorectal polyp, 14% will have at least one major short-term postoperative event.”

Data from 1,230,458 surgeries conducted during 2000-2014 and recorded in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatients Sample were included in this study. Patients who underwent a nonendoscopic procedure for nonmalignant polyps were predominantly non-Hispanic white, covered by Medicare, from the highest household income range, and an average age of 66 years.

While non-Hispanic white patients had the highest overall rate increase by ethnicity, rising from 5.6 to 10.5 per 100,000 population, rates in non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients also rose significantly, increasing from 3.5 to 5.8 per 100,000 population, and from 1.1 to 3.7 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Regionally, rates of surgery were higher in the Midwest (10.8 per 100,000) and the South (10.6 per 100,000) than in the Northeast (7.8 per 100,000) and West (7.5 per 100,000). Incidence rates rose equally during the study period for both men and women.

Large urban teaching hospitals were found to have the largest rate increase when data were stratified by teaching status, a finding which caught Dr. Peery and fellow investigators by surprise.

“We had hypothesized that surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps would be both uncommon and declining in teaching hospitals where providers are more likely to be familiar with current guidelines and to have access to endoscopic mucosal resection,” wrote the investigators. “Instead, we found that surgery for nonmalignant colorectal polyps is both common and significantly increasing in teaching hospitals.”

The investigators first hypothesized the increased rate in teaching hospitals could be due to a higher concentration of case referrals to these high-volume centers, following a trend of centralizing cancer procedures. However, there has been no other sign that colon and rectal cancer procedures are following this trend.

Another option considered by Dr. Peery and her colleagues was that increased procedures may stem from a rise in colorectal cancer screening; however, the data indicate screenings did not change from 2010 to 2015, leaving investigators with few final guesses to go on.

“It is also conceivable that increasing production pressure and inadequate reimbursement for endoscopic mucosal resection may persuade endoscopists to refer patients with complex nonmalignant colorectal polyps for surgery,” said Dr. Peery and fellow investigators. “Finally, there is the issue of risk ... for endoscopists without additional training in advanced endoscopic resection, these risks may be perceived as too great, especially when they have the option of referring for a surgical resection.”

There is a possibility that the incidence of surgery was over- or underestimated, as investigators were using ICD-9 codes to identify cases, and patients with diverticulitis were also excluded, which may have affected results.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Peery A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.003.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Surgical resections for nonmalignant colorectal polyps are increasing while safer endoscopic procedures are available.

Major finding: Incidence rate of surgery for nonmalignant polyps has increased from 5.9 to 9.4 per 100,000 adults from 2000 to 2014.

Study details: A retrospective study of 1,230,458 surgeries recorded in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample from 2000 to 2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Peery A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.003.

Strategies to reduce colorectal surgery complications

LAS VEGAS – Colorectal surgery is rife with potential complications, but there are steps that surgeons can take to improve outcomes, and factors to consider to reduce complications. These strategies and considerations were the focus of a talk by Matthew G. Mutch, MD, at the Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Prehabilitation

The approach to improve outcomes can begin with prehabilitation – preparing the patient for the difficult process of surgery. “If somebody is going to fight a 15-round heavyweight bout, they train for 6 or 8 weeks before a fight. Why not bring that concept to surgery?” said Dr. Mutch, chief of colon and rectal surgery at the Washington University, St. Louis.

Prehabilitation can include lifestyle changes, such as quitting smoking, but can also incorporate aerobic and/or resistance exercise, dietary counseling and protein supplementation, anxiety reduction, and medical education to prepare the patient for the challenges ahead. “Preoperatively, we try to identify factors to see if we can make meaningful lifestyle changes, because that’s really the grassroots level where a lot of this [improvement in outcomes] is going to occur,” said Dr. Mutch.

Frailty

Frailty is a factor driving complications in colorectal surgery. A meta-analysis of 20 studies showed that frailty and prefrailty were associated with worse all-cause mortality during follow-up among older cancer patients. More striking, it showed that frail patients were nearly five times more likely to be intolerant of cancer treatment (odds ratio, 4.86) and more likely to experience postoperative complications (30-day hazard ratio, 3.19) (Ann Oncol. 2015;26[6]:1091-1101).

Hemoglobin A1c

Dr. Mutch went on to discuss hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels as a risk factor in colorectal surgery. HbA1c levels higher than 6 are associated with worse outcomes, but tight postoperative control is associated with hypoglycemia. “What you want to do is set that patient up before surgery. HbA1c has a half-life of about a month, so if you start modifying their risk factors 4-6 weeks before you get them into surgery, by 1 month you can see a 50% reduction, and at 2 months a 75% reduction. If you do these things in a preoperative setting it makes a difference,” said Dr. Mutch.

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation is another key strategy. Two weeks of cessation should lead to a decline in coughing, but a minimum of 4 weeks is needed to significantly reduce overall complications. Lifestyle changes need to be long term. “These are not measures that you’re going to do over a short period of time, and then when surgery is over throw it out the window,” said Dr. Mutch.

Anastomotic leak

Another factor is the detection of anastomotic leak, which can be challenging because its definitions vary significantly, and its causes can be multifactorial. Studies show that predictions of anastomotic leak are not especially successful, Dr. Mutch said, but routine leak testing improves outcomes. In a study of left-side anastomoses in Washington State, hospitals that performed leak tests had lower leak rates at least 90% of the time (OR, 0.23), and hospitals that later implemented leak tests experienced a significant reduction (Arch Surg. 2012:147[4]:345-51).

Venous thromboembolic events

Venous thromboembolic events (VTE), are the leading cause of operative mortality in colorectal surgery patients. This complication can be greatly reduced with prophylaxis, but requires screening for risk factors. Major surgery raises the risk of deep vein thrombosis in 20% of all hospitalized patients to 40%-80%, depending on the surgery type. “We have a lot of room to improve,” said Dr. Mutch.

Timing

One factor that may have an impact on complications appears to be timing of surgery, at least at Washington University, where Dr. Mutch practices. The institution found that patients who had surgery the same day they were admitted had a 2.5% VTE risk, compared with 11% in patients who had surgery 5 or more days after admission.

Postop ambulation

Postsurgical ambulation was another critical complication factor. Dr. Mutch cited a study showing that ambulation on the day after surgery was associated with a 1% VTE risk, compared to 6.9% in patients who waited until day 2.

Dr. Mutch had no disclosures. Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Colorectal surgery is rife with potential complications, but there are steps that surgeons can take to improve outcomes, and factors to consider to reduce complications. These strategies and considerations were the focus of a talk by Matthew G. Mutch, MD, at the Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Prehabilitation

The approach to improve outcomes can begin with prehabilitation – preparing the patient for the difficult process of surgery. “If somebody is going to fight a 15-round heavyweight bout, they train for 6 or 8 weeks before a fight. Why not bring that concept to surgery?” said Dr. Mutch, chief of colon and rectal surgery at the Washington University, St. Louis.

Prehabilitation can include lifestyle changes, such as quitting smoking, but can also incorporate aerobic and/or resistance exercise, dietary counseling and protein supplementation, anxiety reduction, and medical education to prepare the patient for the challenges ahead. “Preoperatively, we try to identify factors to see if we can make meaningful lifestyle changes, because that’s really the grassroots level where a lot of this [improvement in outcomes] is going to occur,” said Dr. Mutch.

Frailty

Frailty is a factor driving complications in colorectal surgery. A meta-analysis of 20 studies showed that frailty and prefrailty were associated with worse all-cause mortality during follow-up among older cancer patients. More striking, it showed that frail patients were nearly five times more likely to be intolerant of cancer treatment (odds ratio, 4.86) and more likely to experience postoperative complications (30-day hazard ratio, 3.19) (Ann Oncol. 2015;26[6]:1091-1101).

Hemoglobin A1c

Dr. Mutch went on to discuss hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels as a risk factor in colorectal surgery. HbA1c levels higher than 6 are associated with worse outcomes, but tight postoperative control is associated with hypoglycemia. “What you want to do is set that patient up before surgery. HbA1c has a half-life of about a month, so if you start modifying their risk factors 4-6 weeks before you get them into surgery, by 1 month you can see a 50% reduction, and at 2 months a 75% reduction. If you do these things in a preoperative setting it makes a difference,” said Dr. Mutch.

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation is another key strategy. Two weeks of cessation should lead to a decline in coughing, but a minimum of 4 weeks is needed to significantly reduce overall complications. Lifestyle changes need to be long term. “These are not measures that you’re going to do over a short period of time, and then when surgery is over throw it out the window,” said Dr. Mutch.

Anastomotic leak

Another factor is the detection of anastomotic leak, which can be challenging because its definitions vary significantly, and its causes can be multifactorial. Studies show that predictions of anastomotic leak are not especially successful, Dr. Mutch said, but routine leak testing improves outcomes. In a study of left-side anastomoses in Washington State, hospitals that performed leak tests had lower leak rates at least 90% of the time (OR, 0.23), and hospitals that later implemented leak tests experienced a significant reduction (Arch Surg. 2012:147[4]:345-51).

Venous thromboembolic events

Venous thromboembolic events (VTE), are the leading cause of operative mortality in colorectal surgery patients. This complication can be greatly reduced with prophylaxis, but requires screening for risk factors. Major surgery raises the risk of deep vein thrombosis in 20% of all hospitalized patients to 40%-80%, depending on the surgery type. “We have a lot of room to improve,” said Dr. Mutch.

Timing

One factor that may have an impact on complications appears to be timing of surgery, at least at Washington University, where Dr. Mutch practices. The institution found that patients who had surgery the same day they were admitted had a 2.5% VTE risk, compared with 11% in patients who had surgery 5 or more days after admission.

Postop ambulation

Postsurgical ambulation was another critical complication factor. Dr. Mutch cited a study showing that ambulation on the day after surgery was associated with a 1% VTE risk, compared to 6.9% in patients who waited until day 2.

Dr. Mutch had no disclosures. Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Colorectal surgery is rife with potential complications, but there are steps that surgeons can take to improve outcomes, and factors to consider to reduce complications. These strategies and considerations were the focus of a talk by Matthew G. Mutch, MD, at the Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Prehabilitation

The approach to improve outcomes can begin with prehabilitation – preparing the patient for the difficult process of surgery. “If somebody is going to fight a 15-round heavyweight bout, they train for 6 or 8 weeks before a fight. Why not bring that concept to surgery?” said Dr. Mutch, chief of colon and rectal surgery at the Washington University, St. Louis.

Prehabilitation can include lifestyle changes, such as quitting smoking, but can also incorporate aerobic and/or resistance exercise, dietary counseling and protein supplementation, anxiety reduction, and medical education to prepare the patient for the challenges ahead. “Preoperatively, we try to identify factors to see if we can make meaningful lifestyle changes, because that’s really the grassroots level where a lot of this [improvement in outcomes] is going to occur,” said Dr. Mutch.

Frailty

Frailty is a factor driving complications in colorectal surgery. A meta-analysis of 20 studies showed that frailty and prefrailty were associated with worse all-cause mortality during follow-up among older cancer patients. More striking, it showed that frail patients were nearly five times more likely to be intolerant of cancer treatment (odds ratio, 4.86) and more likely to experience postoperative complications (30-day hazard ratio, 3.19) (Ann Oncol. 2015;26[6]:1091-1101).

Hemoglobin A1c

Dr. Mutch went on to discuss hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels as a risk factor in colorectal surgery. HbA1c levels higher than 6 are associated with worse outcomes, but tight postoperative control is associated with hypoglycemia. “What you want to do is set that patient up before surgery. HbA1c has a half-life of about a month, so if you start modifying their risk factors 4-6 weeks before you get them into surgery, by 1 month you can see a 50% reduction, and at 2 months a 75% reduction. If you do these things in a preoperative setting it makes a difference,” said Dr. Mutch.

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation is another key strategy. Two weeks of cessation should lead to a decline in coughing, but a minimum of 4 weeks is needed to significantly reduce overall complications. Lifestyle changes need to be long term. “These are not measures that you’re going to do over a short period of time, and then when surgery is over throw it out the window,” said Dr. Mutch.

Anastomotic leak

Another factor is the detection of anastomotic leak, which can be challenging because its definitions vary significantly, and its causes can be multifactorial. Studies show that predictions of anastomotic leak are not especially successful, Dr. Mutch said, but routine leak testing improves outcomes. In a study of left-side anastomoses in Washington State, hospitals that performed leak tests had lower leak rates at least 90% of the time (OR, 0.23), and hospitals that later implemented leak tests experienced a significant reduction (Arch Surg. 2012:147[4]:345-51).

Venous thromboembolic events

Venous thromboembolic events (VTE), are the leading cause of operative mortality in colorectal surgery patients. This complication can be greatly reduced with prophylaxis, but requires screening for risk factors. Major surgery raises the risk of deep vein thrombosis in 20% of all hospitalized patients to 40%-80%, depending on the surgery type. “We have a lot of room to improve,” said Dr. Mutch.

Timing

One factor that may have an impact on complications appears to be timing of surgery, at least at Washington University, where Dr. Mutch practices. The institution found that patients who had surgery the same day they were admitted had a 2.5% VTE risk, compared with 11% in patients who had surgery 5 or more days after admission.

Postop ambulation

Postsurgical ambulation was another critical complication factor. Dr. Mutch cited a study showing that ambulation on the day after surgery was associated with a 1% VTE risk, compared to 6.9% in patients who waited until day 2.

Dr. Mutch had no disclosures. Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM MISS

A Nationwide Survey and Needs Assessment of Colonoscopy Quality Assurance Programs

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is an important concern for the VA, and colonoscopy is one primary screening, surveillance, and diagnostic modality used. The observed reductions in CRC incidence and mortality over the past decade largely have been attributed to the widespread use of CRC screening options.1,2 Colonoscopy quality is critical to CRC prevention in veterans. However, endoscopy skills to detect and remove colorectal polyps using colonoscopy vary in practice.3-5

Quality benchmarks, linked to patient outcomes, have been established by specialty societies and proposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as reportable quality metrics.6 Colonoscopy quality metrics have been shown to be associated with patient outcomes, such as the risk of developing CRC after colonoscopy. The adenoma detection rate (ADR), defined as the proportion of average-risk screening colonoscopies in which 1 or more adenomas are detected, has the strongest association to interval or “missed” CRC after screening colonoscopy and has been linked to a risk for fatal CRC despite colonoscopy.3

In a landmark study of 314,872 examinations performed by 136 gastroenterologists, the ADR ranged from 7.4% to 52.5%.3 Among patients with ADRs in the highest quintile compared with patients in the lowest, the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for any interval cancer was 0.52 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39-0.69) and for fatal interval cancers was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.22-0.65).3 Another pooled analysis from 8 surveillance studies that followed more than 800 participants with adenoma(s) after a baseline colonoscopy showed 52% of incident cancers as probable missed lesions, 19% as possibly related to incomplete resection of an earlier, noninvasive lesion, and only 24% as probable new lesions.7 These interval cancers highlight the current imperfections of colonoscopy and the focus on measurement and reporting of quality indicators for colonoscopy.8-12

According to VHA Directive 1015, in December 2014, colonoscopy quality should be monitored as part of an ongoing quality assurance program.13 A recent report from the VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) highlighted colonoscopy-quality deficiencies.14 The OIG report strongly recommended that the “Acting Under Secretary for Health require standardized documentation of quality indicators based on professional society guidelines and published literature.”14However, no currently standardized and readily available VHA resource measures, reports, and ensures colonoscopy quality.

The authors hypothesized that colonoscopy quality assurance programs vary widely across VHA sites. The objective of this survey was to assess the measurement and reporting practices for colonoscopy quality and identify both strengths and areas for improvement to facilitate implementation of quality assurance programs across the VA health care system.

Methods

The authors performed an online survey of VA sites to assess current colonoscopy quality assurance practices. The institutional review boards (IRBs) at the University of Utah and VA Salt Lake City Health Care System and University of California, San Francisco and San Francisco VA Health Care System classified the study as a quality improvement project that did not qualify for human subjects’ research requiring IRB review.

The authors iteratively developed and refined the questionnaire with a survey methodologist and 2 clinical domain experts. The National Program Director for Gastroenterology, and the National Gastroenterology Field Advisory Committee reviewed the survey content and pretested the survey instrument prior to final data collection. The National Program Office for Gastroenterology provided an e-mail list of all known VA gastroenterology section chiefs. The authors administered the final survey via e-mail, using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Vanderbilt University Medical Center) platform beginning January 9, 2017.15

A follow-up reminder e-mail was sent to nonresponders after 2 weeks. After this second invitation, sites were contacted by telephone to verify that the correct contact information had been captured. Subsequently, 50 contacts were updated if e-mails bounced back or the correct contact was obtained. Points of contact received a total of 3 reminder e-mails until the final closeout of the survey on March 28, 2017; 65 of 89 (73%) of the original contacts completed the survey vs 31 of 50 (62%) of the updated contacts.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the responses were calculated to determine the overall proportion of VA sites measuring colonoscopy quality metrics and identification of areas in need of quality improvement. The response rate for the survey was defined as the total number of responses obtained as a proportion of the total number of points of contact. This corresponds to the American Association of Public Opinion Research’s RR1, or minimum response rate, formula.16 All categoric responses are presented as proportions. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE12.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 139 points of contact invited, 96 completed the survey (response rate of 69.0%), representing 93 VA facilities (of 141 possible facilities) in 44 different states. Three sites had 2 responses. Sites used various and often a combination of methods to measure quality (Table 1).

A majority of sites’ (63.5%) quality reports represented individual provider data, whereas fewer provided quality reports for physician groups (22.9%) or for the entire facility (40.6%). Provider quality information was de-identified in 43.8% of reporting sites’ quality reports and identifiable in 37.5% of reporting sites’ quality reports. A majority of sites (74.0%) reported that the local gastroenterology section chief or quality manager has access to the quality reports. Fewer sites reported providing data to individual endoscopists (44.8% for personal and peer data and 32.3% for personal data only). One site (1%) responded that quality reports were available for public access. Survey respondents also were asked to provide the estimated time (hours required per month) to collect the data for quality metrics. Of 75 respondents providing data for this question, 28 (29.2%) and 17 (17.7%), estimated between 1 to 5 and 6 to 10 hours per month, respectively. Ten sites estimated spending between 11 to 20 hours, and 7 sites estimated spending more than 20 hours per month collecting quality metrics. A total of 13 respondents (13.5%) stated uncertainty about the time burden.

As shown in the Figure, numerous quality metrics were collected across sites with more than 80% of sites collecting information on bowel preparation quality (88.5%), cecal intubation rate (87.5%), and complications (83.3%). A majority of sites also reported collecting data on appropriateness of surveillance intervals (62.5%), colonoscopy withdrawal times (62.5%), and ADRs (61.5%). Seven sites (7.3%) did not collect quality metrics.

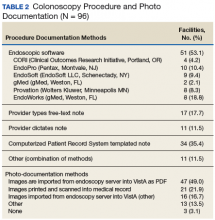

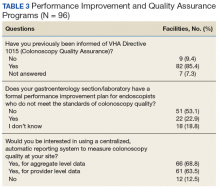

Information also was collected on colonoscopy procedure documentation to inform future efforts at standardization. A small majority (53.1%) of sites reported using endoscopic software to generate colonoscopy procedure documentation. Within these sites, 6 different types of endoscopic note writing software were used to generate procedure notes (Table 2).

Most sites (85.4%) were aware of VHA Directive 1015 recommendations for colonoscopy quality assurance programs. A significant majority (89.5%) of respondents also indicated interest in a centralized automatic reporting system to measure and report colonoscopy quality in some form, either with aggregate data, provider data, or both (Table 3).

Discussion

This survey on colonoscopy quality assurance programs is the first assessment of the VHA’s efforts to measure and report colonoscopy quality indicators. The findings indicated that the majority of VA sites are measuring and reporting at least some measures of colonoscopy quality. However, the programs are significantly variable in terms of methods used to collect quality metrics, specific quality measures obtained, and how quality is reported.

The authors’ work is novel in that this is the first report of the status of colonoscopy quality assurance programs in a large U.S. health care system. The VA health care system is the largest integrated health system in the U.S., serving more than 9 million veterans annually. This survey’s high response rate further strengthens the findings. Specifically, the survey found that VA sites are making a strong concerted effort to measure and report colonoscopy quality. However, there is significant variability in documentation, measurement, and reporting practices. Moreover, the majority of VA sites do not have formal performance improvement plans in place for endoscopists who do not meet thresholds for colonoscopy quality.

Screening colonoscopy for CRC offers known mortality benefits to patients.1,17-19 Significant prior work has described and validated the importance of colonoscopy quality metrics, including bowel preparation quality, cecal intubation rate, and ADR and their association with interval colorectal cancer and death.20-23 Gastroenterology professional societies, including the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, have recommended and endorsed measurement and reporting of colonoscopy metrics.24 There is general agreement among endoscopists that colonoscopy quality is an important aspect of performing the procedure.

The lack of formal performance improvement programs is a key finding of this survey. Recent studies have shown that improvements in quality metrics, such as the ADR, by individual endoscopists result in reductions in interval colorectal cancer and death.25 Kahi and colleagues previously showed that providing a quarterly report card improves colonoscopy quality.26 Keswani and colleagues studied a combination of a report card and implementation of standards of practice with resultant improvement in colonoscopy quality.27 Most recently, in a large prospective cohort study of individuals who underwent a screening colonoscopy, 294 of the screening endoscopists received annual feedback and quality benchmark indicators to improve colonoscopy performance.25 The majority of the endoscopists (74.5%) increased their annual ADR category over the study period. Moreover, patients examined by endoscopists who reached or maintained the highest ADR quintile (> 24.6%) had significantly lower risk of interval CRC and death. The lack of formal performance improvement programs across the VHA is concerning but reveals a significant opportunity to improve veteran health outcomes on a large scale.

This study’s findings also highlight the intense resources necessary to measure and report colonoscopy quality. The ability to measure and report quality metrics requires having adequate documentation and data to obtain quality metrics. Administrative databases from electronic health records offer some potential for routine monitoring of quality metrics.28 However, most administrative databases, including the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), contain administrative billing codes (ICD and CPT) linked to limited patient data, including demographics and structured medical record data. The actual data required for quality reporting of important metrics (bowel preparation quality, cecal intubation rates, and ADRs) are usually found in clinical text notes or endoscopic note documentation and not available as structured data. Due to this issue, the majority of VA sites (79.2%) are using manual chart review to collect quality metric data, resulting in widely variable estimates on time burden. A minority of sites in this study (39.6%) reported using automated endoscopic software reporting capability that can help with the time burden. However, even in the VA, an integrated health system, a wide variety of software brands, documentation practices, and photo documentation was found.

Future endoscopy budget and purchase decisions for the individual VA sites should take into account how new technology and software can more easily facilitate accurate quality reporting. A specific policy recommendation would be for the VA to consider a uniform endoscopic note writer for procedure notes. Pathology data, which is necessary for the calculation of ADR, also should be available as structured data in the CDW to more easily measure colonoscopy quality. Continuous measurement and reporting of quality also requires ongoing information technology infrastructure and quality control of the measurement process.

Limitations

This survey was a cross-section of VA sites’ points of contact regarding colonoscopy quality assurance programs, so the results are descriptive in nature. However, the instrument was carefully developed, using both subject matter and survey method expertise. The questionnaire also was refined through pretesting prior to data collection. The initial contact list was found to have errors, and the list had to be updated after launching the survey. Updated information for most of the contacts was available.

Another limitation was the inability to survey nongastroenterologist-run endoscopy centers, because many centers use surgeons or other nongastroenterology providers. The authors speculate that quality monitoring may be less likely to be present at these facilities as they may not be aware of the gastroenterology professional society recommendations. The authors did not require or insist that all questions be answered, so some data were missing from sites. However, 93.7% of respondents completed the entire survey.

Conclusion

The authors have described the status of colonoscopy quality assurance programs across the VA health care system. Many sites are making robust efforts to measure and report quality especially of process measures. However, there are significant time and manual workforce efforts required, and this work is likely associated with the variability in programs. Importantly, ADR, which is the quality metric that has been most strongly associated with risk of colon cancer mortality, is not being measured by 38% of sites.

These results reinforce a critical need for a centralized, automated quality reporting infrastructure to standardize colonoscopy quality reporting, reduce workload, and ensure veterans receive high-quality colonoscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support and feedback of the National Gastroenterology Program Field Advisory Committee for survey development and testing. The authors coordinated the survey through the Salt Lake City Specialty Care Center of Innovation in partnership with the National Gastroenterology Program Office and the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative: Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, Measurement Science Program, QUE15-283. The work also was partially supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award UL1TR001067 and Merit Review Award 1 I01 HX001574-01A1 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development.

1. Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2467.