User login

Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection may be an option for colorectal lesions

without increasing procedure time or risk of adverse events, based on a recent head-to-head trial conducted in Japan.

UEMR was associated with higher R0 and en bloc resection rates than was conventional EMR (CEMR) when used for intermediate-size colorectal lesions, reported lead author Takeshi Yamashina, MD, of Osaka (Japan) International Cancer Institute, and colleagues. The study was the first multicenter, randomized trial to demonstrate the superiority of UEMR over CEMR, they noted.

Although CEMR is a well-established method of removing sessile colorectal lesions, those larger than 10 mm can be difficult to resect en bloc, which contributes to a local recurrence rate exceeding 15% when alternative, piecemeal resection is performed, the investigators explained in Gastroenterology

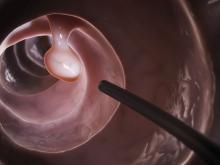

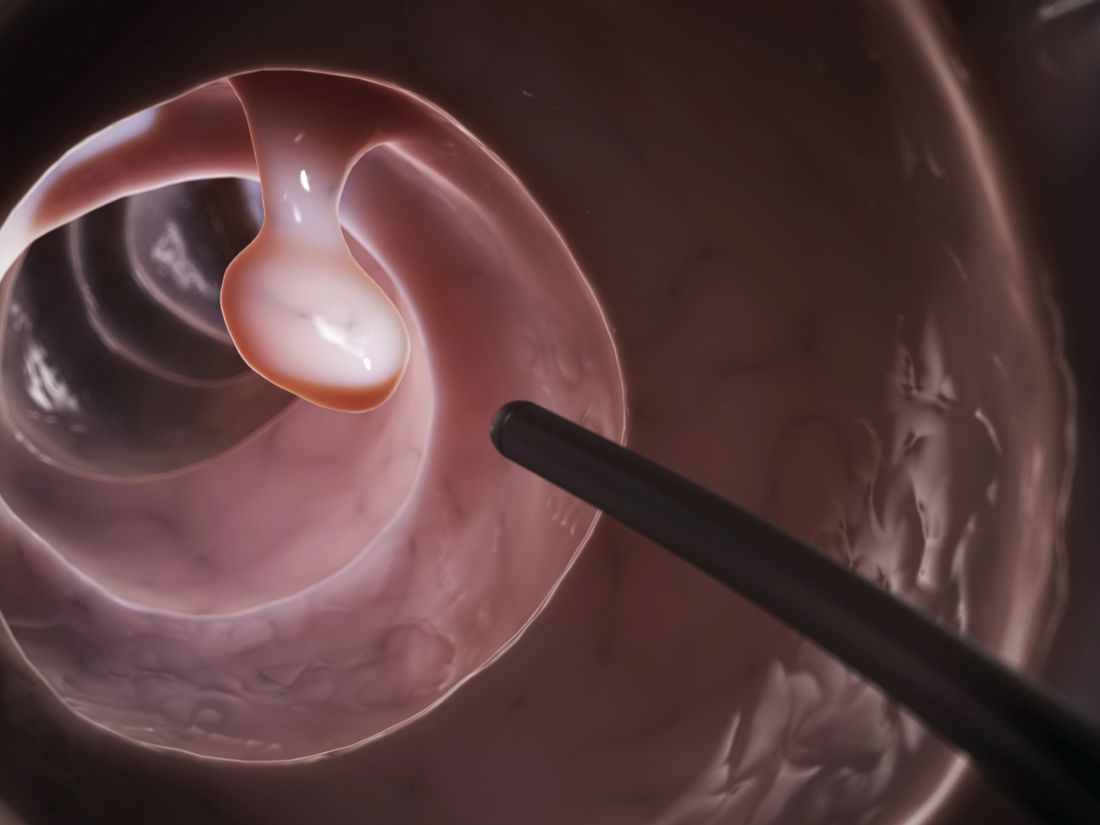

Recently, UEMR has emerged as “an alternative to CEMR and is reported to be effective for removing flat or large colorectal polyps,” the investigators wrote. “With UEMR, the bowel lumen is filled with water instead of air/CO2, and the lesion is captured and resected with a snare without submucosal injection of normal saline.”

To find out if UEMR offers better results than CEMR, the investigators recruited 211 patients with 214 colorectal lesions at five centers in Japan. Patients were aged at least 20 years and had mucosal lesions of 10-20 mm in diameter. Based on macroscopic appearance, pit pattern classification with magnifying chromoendoscopy, or narrow-band imaging, lesions were classified as adenoma, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, or intramucosal adenocarcinoma. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the UEMR or CEMR group, and just prior to the procedure, operators were informed of the allocated treatment. Ten expert operators were involved, each with at least 10 years of experience, in addition to 18 nonexpert operators with less than 10 years of experience. The primary endpoint was the difference in R0 resection rate between the two groups, with R0 defined as en bloc resection with histologically negative margins. Secondary endpoints were en bloc resection rate, adverse events, and procedure time.

The results showed a clear win for UEMR, with an R0 rate of 69%, compared with 50% for CEMR (P = .011), and an en bloc resection rate that followed the same trend (89% vs. 75%; P = .007). Neither median procedure times nor number of adverse events were significantly different between groups.

Subset analysis showed that UEMR was best suited for lesions at least 15 mm in diameter, although the investigators pointed out the superior R0 resection rate with UEMR held steady regardless of lesion morphology, size, location, or operator experience level.

The investigators suggested that the findings give reason to amend some existing recommendations. “Although the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinical Guidelines suggest hot-snare polypectomy with submucosal injection for removing sessile polyps 10-19 mm in size, we found that UEMR was more effective than CEMR, in terms of better R0 and en bloc resection rates,” they wrote. “Hence, we think that UEMR will become an alternative to CEMR. It could fill the gap for removing polyps 9 mm [or larger] (indication for removal by cold-snare polypectomy) and [smaller than] 20 mm (indication for ESD removal).”

During the discussion, the investigators explained that UEMR achieves better outcomes primarily by improving access to lesions. Water immersion causes lesions to float upright into the lumen, while keeping the muscularis propria circular behind the submucosa, which allows for easier snaring and decreases risk of perforation. Furthermore, the investigators noted, water immersion limits flexure angulation, luminal distension, and loop formation, all of which improve maneuverability and visibility.

Still, UEMR may take some operator adjustment, the investigators added, going on to provide some pointers. “In practice, we think it is important to fill the entire lumen only with fluid, so we always deflate the lumen completely and then fill it with fluid,” they wrote. “[When the lumen is filled], it is not necessary to change the patient’s position during the UEMR procedure.”

“Also, in cases with unclear endoscopic vision, endoscopists are familiar with air insufflation but, during UEMR, it is better to infuse the fluid to expand the lumen and maintain a good endoscopic view. Therefore, for the beginner, we recommend that the air insufflation button of the endoscopy machine be switched off.”

Additional tips included using saline instead of distilled water, and employing thin, soft snares.

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yamashina T et al. Gastro. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.005.

without increasing procedure time or risk of adverse events, based on a recent head-to-head trial conducted in Japan.

UEMR was associated with higher R0 and en bloc resection rates than was conventional EMR (CEMR) when used for intermediate-size colorectal lesions, reported lead author Takeshi Yamashina, MD, of Osaka (Japan) International Cancer Institute, and colleagues. The study was the first multicenter, randomized trial to demonstrate the superiority of UEMR over CEMR, they noted.

Although CEMR is a well-established method of removing sessile colorectal lesions, those larger than 10 mm can be difficult to resect en bloc, which contributes to a local recurrence rate exceeding 15% when alternative, piecemeal resection is performed, the investigators explained in Gastroenterology

Recently, UEMR has emerged as “an alternative to CEMR and is reported to be effective for removing flat or large colorectal polyps,” the investigators wrote. “With UEMR, the bowel lumen is filled with water instead of air/CO2, and the lesion is captured and resected with a snare without submucosal injection of normal saline.”

To find out if UEMR offers better results than CEMR, the investigators recruited 211 patients with 214 colorectal lesions at five centers in Japan. Patients were aged at least 20 years and had mucosal lesions of 10-20 mm in diameter. Based on macroscopic appearance, pit pattern classification with magnifying chromoendoscopy, or narrow-band imaging, lesions were classified as adenoma, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, or intramucosal adenocarcinoma. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the UEMR or CEMR group, and just prior to the procedure, operators were informed of the allocated treatment. Ten expert operators were involved, each with at least 10 years of experience, in addition to 18 nonexpert operators with less than 10 years of experience. The primary endpoint was the difference in R0 resection rate between the two groups, with R0 defined as en bloc resection with histologically negative margins. Secondary endpoints were en bloc resection rate, adverse events, and procedure time.

The results showed a clear win for UEMR, with an R0 rate of 69%, compared with 50% for CEMR (P = .011), and an en bloc resection rate that followed the same trend (89% vs. 75%; P = .007). Neither median procedure times nor number of adverse events were significantly different between groups.

Subset analysis showed that UEMR was best suited for lesions at least 15 mm in diameter, although the investigators pointed out the superior R0 resection rate with UEMR held steady regardless of lesion morphology, size, location, or operator experience level.

The investigators suggested that the findings give reason to amend some existing recommendations. “Although the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinical Guidelines suggest hot-snare polypectomy with submucosal injection for removing sessile polyps 10-19 mm in size, we found that UEMR was more effective than CEMR, in terms of better R0 and en bloc resection rates,” they wrote. “Hence, we think that UEMR will become an alternative to CEMR. It could fill the gap for removing polyps 9 mm [or larger] (indication for removal by cold-snare polypectomy) and [smaller than] 20 mm (indication for ESD removal).”

During the discussion, the investigators explained that UEMR achieves better outcomes primarily by improving access to lesions. Water immersion causes lesions to float upright into the lumen, while keeping the muscularis propria circular behind the submucosa, which allows for easier snaring and decreases risk of perforation. Furthermore, the investigators noted, water immersion limits flexure angulation, luminal distension, and loop formation, all of which improve maneuverability and visibility.

Still, UEMR may take some operator adjustment, the investigators added, going on to provide some pointers. “In practice, we think it is important to fill the entire lumen only with fluid, so we always deflate the lumen completely and then fill it with fluid,” they wrote. “[When the lumen is filled], it is not necessary to change the patient’s position during the UEMR procedure.”

“Also, in cases with unclear endoscopic vision, endoscopists are familiar with air insufflation but, during UEMR, it is better to infuse the fluid to expand the lumen and maintain a good endoscopic view. Therefore, for the beginner, we recommend that the air insufflation button of the endoscopy machine be switched off.”

Additional tips included using saline instead of distilled water, and employing thin, soft snares.

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yamashina T et al. Gastro. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.005.

without increasing procedure time or risk of adverse events, based on a recent head-to-head trial conducted in Japan.

UEMR was associated with higher R0 and en bloc resection rates than was conventional EMR (CEMR) when used for intermediate-size colorectal lesions, reported lead author Takeshi Yamashina, MD, of Osaka (Japan) International Cancer Institute, and colleagues. The study was the first multicenter, randomized trial to demonstrate the superiority of UEMR over CEMR, they noted.

Although CEMR is a well-established method of removing sessile colorectal lesions, those larger than 10 mm can be difficult to resect en bloc, which contributes to a local recurrence rate exceeding 15% when alternative, piecemeal resection is performed, the investigators explained in Gastroenterology

Recently, UEMR has emerged as “an alternative to CEMR and is reported to be effective for removing flat or large colorectal polyps,” the investigators wrote. “With UEMR, the bowel lumen is filled with water instead of air/CO2, and the lesion is captured and resected with a snare without submucosal injection of normal saline.”

To find out if UEMR offers better results than CEMR, the investigators recruited 211 patients with 214 colorectal lesions at five centers in Japan. Patients were aged at least 20 years and had mucosal lesions of 10-20 mm in diameter. Based on macroscopic appearance, pit pattern classification with magnifying chromoendoscopy, or narrow-band imaging, lesions were classified as adenoma, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, or intramucosal adenocarcinoma. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the UEMR or CEMR group, and just prior to the procedure, operators were informed of the allocated treatment. Ten expert operators were involved, each with at least 10 years of experience, in addition to 18 nonexpert operators with less than 10 years of experience. The primary endpoint was the difference in R0 resection rate between the two groups, with R0 defined as en bloc resection with histologically negative margins. Secondary endpoints were en bloc resection rate, adverse events, and procedure time.

The results showed a clear win for UEMR, with an R0 rate of 69%, compared with 50% for CEMR (P = .011), and an en bloc resection rate that followed the same trend (89% vs. 75%; P = .007). Neither median procedure times nor number of adverse events were significantly different between groups.

Subset analysis showed that UEMR was best suited for lesions at least 15 mm in diameter, although the investigators pointed out the superior R0 resection rate with UEMR held steady regardless of lesion morphology, size, location, or operator experience level.

The investigators suggested that the findings give reason to amend some existing recommendations. “Although the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinical Guidelines suggest hot-snare polypectomy with submucosal injection for removing sessile polyps 10-19 mm in size, we found that UEMR was more effective than CEMR, in terms of better R0 and en bloc resection rates,” they wrote. “Hence, we think that UEMR will become an alternative to CEMR. It could fill the gap for removing polyps 9 mm [or larger] (indication for removal by cold-snare polypectomy) and [smaller than] 20 mm (indication for ESD removal).”

During the discussion, the investigators explained that UEMR achieves better outcomes primarily by improving access to lesions. Water immersion causes lesions to float upright into the lumen, while keeping the muscularis propria circular behind the submucosa, which allows for easier snaring and decreases risk of perforation. Furthermore, the investigators noted, water immersion limits flexure angulation, luminal distension, and loop formation, all of which improve maneuverability and visibility.

Still, UEMR may take some operator adjustment, the investigators added, going on to provide some pointers. “In practice, we think it is important to fill the entire lumen only with fluid, so we always deflate the lumen completely and then fill it with fluid,” they wrote. “[When the lumen is filled], it is not necessary to change the patient’s position during the UEMR procedure.”

“Also, in cases with unclear endoscopic vision, endoscopists are familiar with air insufflation but, during UEMR, it is better to infuse the fluid to expand the lumen and maintain a good endoscopic view. Therefore, for the beginner, we recommend that the air insufflation button of the endoscopy machine be switched off.”

Additional tips included using saline instead of distilled water, and employing thin, soft snares.

The investigators reported no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Yamashina T et al. Gastro. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.005.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Unrelated Death After Colorectal Cancer Screening: Implications for Improving Colonoscopy Referrals

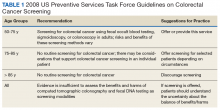

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks among the most common causes of cancer and cancer-related death in the US. The US Multi-Society Task Force (USMSTF) on Colorectal Cancer thus strongly endorsed using several available screening options.1 The published guidelines largely rely on age to define the target population (Table 1). For average-risk individuals, national and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) guidelines currently recommend CRC screening in individuals aged between 50 and 75 years with a life expectancy of > 5 years.1

Although case-control studies also point to a potential benefit in persons aged > 75 years,2,3 the USMSTF cited less convincing evidence and suggested an individualized approach that should consider relative cancer risk and comorbidity burden. Such an approach is supported by modeling studies, which suggest reduced benefit and increased risk of screening with increasing age. The reduced benefit also is significantly affected by comorbidity and relative cancer risk.4 The VHA has successfully implemented CRC screening, capturing the majority of eligible patients based on age criteria. A recent survey showed that more than three-quarters of veterans between age 50 and 75 years had undergone some screening test for CRC as part of routine preventive care. Colonoscopy clearly emerged as the dominant modality chosen for CRC screening and accounted for nearly 84% of these screening tests.5 Consistent with these data, a case-control study confirmed that the widespread implementation of colonoscopy as CRC screening method reduced cancer-related mortality in veterans for cases of left but not right-sided colon cancer.6

With calls to expand the age range of CRC screening beyond aged 75 years, we decided to assess survival rates of a cohort of veterans who underwent a screening or surveillance colonoscopy between 2008 and 2014.7 The goals were to characterize the portion of the cohort that had died, the time between a screening colonoscopy and death, the portion of deaths that were aged ≥ 80 years, and the causes of the deaths. In addition, we focused on a subgroup of the cohort, defined by death within 2 years after the index colonoscopy, to identify predictors of early death that were independent of age.

Methods

We queried the endoscopy reporting system (EndoWorks; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) for all colonoscopies performed by 2 of 14 physicians at the George Wahlen VA Medical Center (GWVAMC) in Salt Lake City, Utah, who performed endoscopic procedures between January 1, 2008 and December 1, 2014. These physicians had focused their clinical practice exclusively on elective outpatient colonoscopies and accounted for 37.4% of the examinations at GWVAMC during the study period. All colonoscopy requests were triaged and assigned based on availability of open and appropriate procedure time slots without direct physician-specific referral, thus reducing the chance of skewing results. The reports were filtered through a text search to focus on examinations that listed screening or surveillance as indication. The central patient electronic health record was then reviewed to extract basic demographic data, survival status (as of August 1, 2018), and survival time in years after the index or subsequent colonoscopy. For deceased veterans, the age at the time of death, cause of death, and comorbidities were queried.

This study compared cases and control across the study. Cases were persons who clearly died early (defined as > 2 years following the index examination). They were matched with controls who lived for ≥ 5 years after their colonoscopy. These periods were selected because the USMSTF recommended that CRC screening or surveillance colonoscopy should be discontinued in persons with a life expectancy of < 5 years, and most study patients underwent their index procedure ≥ 5 years before August 2018. Cases and controls underwent a colonoscopy in the same year and were matched for age, sex, and presence of underlying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For cases and controls, we identified the ordering health care provider specialty, (ie, primary care, gastroenterology, or other).

In addition, we reviewed the encounter linked to the order and abstracted relevant comorbidities listed at that time, noted the use of anticoagulants, opioid analgesics, and benzodiazepines. The comorbidity burden was quantified using the Charlson Comorbidity Index.8 In addition, we denoted the presence of psychiatric problems (eg, anxiety, depression, bipolar disease, psychosis, substance abuse), the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation (AF) or other cardiac arrhythmias, and whether the patient had previously been treated for a malignancy that was in apparent clinical remission. Finally, we searched for routine laboratory tests at the time of this visit or, when not obtained, within 6 months of the encounter, and abstracted serum creatinine, hemoglobin (Hgb), platelet number, serum protein, and albumin. In clinical practice, cutoff values of test results are often more helpful in decision making. We, therefore, dichotomized results for Hgb (cutoff: 10 g/dL), creatinine (cutoff: 2 mg/dL), and albumin (cutoff: 3.2 mg/dL).

Descriptive and analytical statistics were obtained with Stata Version 14.1 (College Station, TX). Unless indicated otherwise, continuous data are shown as mean with 95% CIs. For dichotomous data, we used percentages with their 95% CIs. Analytic statistics were performed with the t test for continuous variables and the 2-tailed test for proportions. A P < .05 was considered a significant difference. To determine independent predictors of early death, we performed a logistic regression analysis with results being expressed as odds ratio with 95% CIs. Survival status was chosen as a dependent variable, and we entered variables that significantly correlated with survival in the bivariate analysis as independent variables.

The study was designed and conducted as a quality improvement project to assess colonoscopy performance and outcomes with the Salt Lake City Specialty Care Center of Innovation (COI), one of 5 regional COIs with an operational mission to improve health care access, utilization, and quality. Our work related to colonoscopy and access within the COI region, including Salt Lake City, has been reviewed and acknowledged by the GWVAMC Institutional Review Board as quality improvement. Andrew Gawron has an operational appointment in the GWVAMC COI, which is part of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) central office initiative established in 2015. The COIs are charged with identifying best practices within the VA and applying those practices throughout the COI region. This local project to identify practice patterns and outcomes locally was sponsored by the GWVAMC COI with a focus to generate information to improve colonoscopy referral quality in patients at Salt Lake City and inform regional and national efforts in this domain.

Results

During the study period, 4,879 veterans (96.9% male) underwent at least 1 colonoscopy for screening or surveillance by 1 of the 2 providers. A total of 306 persons (6.3%) were aged > 80 years. The indication for surveillance colonoscopies included IBD in 78 (1.6%) veterans 2 of whom were women. The mean (SD) follow-up period between the index colonoscopy and study closure or death was 7.4 years (1.7). During the study time, 1,439 persons underwent a repeat examination for surveillance. The percentage of veterans with at least 1 additional colonoscopy after the index test was significantly higher in patients with known IBD compared with those without IBD (78.2% vs 28.7%; P < .01).

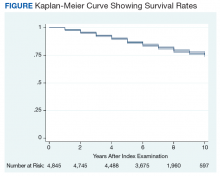

Between the index colonoscopy and August 2018, 974 patients (20.0%) died (Figure). The mean (SD) time between the colonoscopy and recorded year of death was 4.4 years (4.1). The fraction of women in the cohort that died (n = 18) was lower compared with 132 for the group of persons still alive (1.8% vs 3.4%; P < .05). The fraction of veterans with IBD who died by August 2018 did not differ from that of patients with IBD in the cohort of individuals who survived (19.2% vs 20.0%; P = .87). The cohort of veterans who died before study closure included 107 persons who were aged > 80 years at the time of their index colonoscopy, which is significantly more than in the cohort of persons still alive (11.0% vs 5.1%; P < .01).

Cause of Death

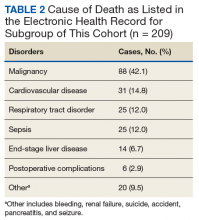

In 209 of the 974 (21.5%) veteran deaths a cause was recorded. Malignancies accounted for 88 of the deaths (42.1%), and CRCs were responsible for 14 (6.7%) deaths (Table 2). In 8 of these patients, the cancer had been identified at an advanced stage, not allowing for curative therapy. One patient had been asked to return for a repeat test as residual fecal matter did not allow proper visualization. He died 1 year later due to complications of sepsis after colonic perforation caused by a proximal colon cancer. Five patients underwent surgery with curative intent but suffered recurrences. In addition to malignancies, advanced diseases, such as cardiovascular, bronchopulmonary illnesses, and infections, were other commonly listed causes of death.

We also abstracted comorbidities that were known at the time of death or the most recent encounter within the VHA system. Hypertension was most commonly listed (549) followed by a current or prior diagnosis of malignancies (355) and diabetes mellitus (DM) (Table 3). Prostate cancer was the most commonly diagnosed malignancy (80), 17 of whom had a second malignancy. CRC accounted for 54 of the malignancies, 1 of which developed in a patient with long-standing ulcerative colitis, 2 were a manifestation of a known hereditary cancer syndrome (Lynch syndrome), and the remaining 51 cases were various cancers without known predisposition. The diagnosis of CRC was made during the study period in 29 veterans. In the remaining 25 patients, the colonoscopy was performed as a surveillance examination after previous surgery for CRC.

Potential Predictors of Early Death

To better define potential predictors of early death, we focused on the 258 persons (5.3%) who died within 2 years after the index procedure and paired them with matched controls. One patient underwent a colonoscopy for surveillance of previously treated cancer and was excluded due to very advanced age, as no matched control could be identified. The mean (SD) age of this male-predominant cohort was 68.2 (9.6) vs 67.9 (9.4) years for cases and controls, respectively. At the time of referral for the test, 29 persons (11.3%) were aged > 80 years, which is significantly more than seen for the overall cohort with 306 (6.3%; P < .001). While primary care providers accounted for most referrals in cases (85.2%) and controls (93.0%), the fraction of veterans referred by gastroenterologists or other specialty care providers was significantly higher in the case group compared with that in the controls (14.8% vs 7.0%; P < .05).

In our age-matched analysis, we examined other potential factors that could influence survival. The burden of comorbid conditions summarized in the Charlson Comorbidity Index significantly correlated with survival status (Table 4). As this composite index does not include psychiatric conditions, we separately examined the impact of anxiety, depression, bipolar disease, psychotic disorders, and substance abuse. The diagnoses of depression and substance use disorders (SUDs) were associated with higher rates of early death. Considering concerns about SUDs, we also assessed the association between prescription for opioids or benzodiazepines and survival status, which showed a marginal correlation. Anticoagulant use, a likely surrogate for cardiovascular disorders, were more commonly listed in the cases than they were in the controls.

Looking at specific comorbid conditions, significant problems affecting key organ systems from heart to lung, liver, kidneys, or brain (dementia) were all predictors of poor outcome. Similarly, DM with secondary complication correlated with early death after the index procedure. In contrast, a history of prior myocardial infarction, prior cancer treatment without evidence of persistent or recurrent disease, or prior peptic ulcer disease did not differ between cases and controls. Focusing on routine blood tests, we noted marginal, but statistically different results for Hgb, serum creatinine, and albumin in cases compared with controls.

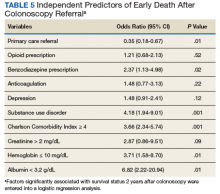

Next we performed a logistic regression to identify independent predictors of survival status. The referring provider specialty, Charlson Comorbidity Index, the diagnosis of a SUD, current benzodiazepine use, and significant anemia or hypoalbuminemia independently predicted death within 2 years of the index examination (Table 5). Considering the composite nature of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, we separately examined the relative importance of different comorbid conditions using a logistic regression analysis. Consistent with the univariate analyses, a known malignancy; severe liver, lung, or kidney disease; and DM with secondary complications were associated with poor outcome. Only arrhythmias other than AF were independent marginal predictors of early death, whereas other variables related to cardiac performance did not reach the level of significance (Table 6). As was true for our analysis examining the composite comorbidity index, the diagnosis of a SUD remained significant as a predictor of death within 2 years of the index colonoscopy.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis followed patients for a mean time of 7 years after a colonoscopy for CRC screening or polyp surveillance. We noted a high rate of all-cause mortality, with 20% of the cohort dying within the period studied. Malignancies, cardiovascular diseases, and advanced lung diseases were most commonly listed causes of death. As expected, CRC was among the 3 most common malignancies and was the cause of death in 6.7% of the group with sufficiently detailed information. While these results fall within the expected range for the mortality related to CRC,9 the results do not allow us to assess the impact of screening, which has been shown to decrease cancer-related mortality in veterans.6 This was limited because the sample size was too small to assess the impact of screening and the cause of death was ascertained for a small percentage of the sample.

Although our findings are limited to a subset of patients seen in a single center, they suggest the importance of appropriate eligibility criteria for screening tests, as also defined in national guidelines.1 As a key anchoring point that describes the target population, age contributed to the rate of relatively early death after the index procedure. Consistent with previously published data, we saw a significant impact of comorbid diseases.10,11 However, our findings go beyond prior reports and show the important impact of psychiatric disease burden, most important the role of SUDs. The predictive value of a summary score, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index, supports the idea of a cumulative impact, with an increasing disease burden decreasing life expectancy.10-14 It is important to consider the ongoing impact of such coexisting illnesses. Our analysis shows, the mere history of prior problems did not independently predict survival status in our cohort.

Although age is the key anchoring point that defines the target population for CRC screening programs, the benefit of earlier cancer detection or, in the context of colonoscopy with polypectomy, cancer prevention comes with a delay. Thus, cancer risk, procedural risk, and life expectancy should all be weighed when discussing and deciding on the appropriateness of CRC screening. When we disregard inherited cancer syndromes, CRC is clearly a disease of the second half of life with the incidence increasing with age.15 However, other disease burdens rise, which may affects the risk of screening and treatment should cancer be found.

Using our understanding of disease development, researchers have introduced the concept of time to benefit or lag time to help decisions about screening strategies. The period defines the likely time for a precursor or early form of cancer potentially detected by screening to manifest as a clinically relevant lesion. This lag time becomes an especially important consideration in screening of older and/or chronically ill adults with life expectancies that may be close to or even less than the time to benefit.16 Modeling studies suggest that 1,000 flexible sigmoidoscopy screenings are needed to prevent 1 cancer that would manifest about 10 years after the index examination.17,18 The mean life expectancy of a healthy person aged 75 years exceeds 10 years but drops with comorbidity burden. Consistent with these considerations, an analysis of Medicare claims data concluded that individuals with ≥ 3 significant comorbidities do not derive any benefit from screening colonoscopy.14 Looking at the impact of comorbidities, mathematical models concluded that colorectal cancer screening should not be continued in persons with moderate or severe comorbid conditions aged 66 years and 72 years, respectively.19 In contrast, modeling results suggest a benefit of continued screening up to and even above the age of 80 years if persons have an increased cancer risk and if there are no confounding comorbidities.4

Life expectancy and time to benefit describe probabilities. Although such probabilities are relevant in public policy decision, providers and patients may struggle with probabilistic thinking when faced with decisions that involve probabilities of individual health care vs population health care. Both are concerned about the seemingly gloomy or pessimistic undertone of discussing life expectancy and the inherent uncertainty of prognostic tools.20,21 Prior research indicates that this reluctance translates into clinical practice. When faced with vignettes, most clinicians would offer CRC screening to healthy persons aged 80 years with rates falling when the description included a significant comorbid burden; however, more than 40% would still consider screening in octogenarians with poor health.22

Consistent with these responses to theoretical scenarios, CRC screening of veterans dropped with age but was still continued in persons with significant comorbidity.23 Large studies of the veteran population suggest that about 10% of veterans aged > 70 years have chronic medical problems that limit their life expectancy to < 5 years; nonetheless, more than 40% of this cohort underwent colonoscopies for CRC screening.24,25 Interestingly, more illness burden and more clinical encounters translated into more screening examinations in older sick veterans compared with that of the cohort of healthier older persons, suggesting an impact of clinical reminders and the key role of age as the main anchoring variable.23

Ongoing screening despite limited or even no benefit is not unique to CRC. Using validated tools, Pollock and colleagues showed comparable screening rates for breast and prostate cancer when they examined cohorts at either high or low risk of early mortality.26 Similar results have been reported in veterans with about one-third of elderly males with poor life expectancy still undergoing prostate cancer screening.27 Interestingly, inappropriate screening is more common in nonacademic centers and influenced by provider characteristics: nurse practitioner, physician assistants, older attending physicians and male physicians were more likely to order such tests.27,28

Limitations

In this study, we examined a cohort of veterans enrolled in CRC screening within a single institution and obtained survival data for a mean follow-up of > 7 years. We also restricted our study to patients undergoing examinations that explicitly listed screening as indication or polyp surveillance for the test. However, inclusion was based on the indication listed in the report, which may differ from the intent of the ordering provider. Reporting systems often come with default settings, which may skew data. Comorbidities for the entire cohort of veterans who died within the time frame of the study were extracted from the chart without controlling for time-dependent changes, which may more appropriately describe the comorbidity burden at the time of the test. Using a case-control design, we addressed this potential caveat and included only illnesses recorded in the encounter linked to the colonoscopy order. Despite these limitations, our results highlight the importance to more effectively define and target appropriate candidates for CRC screening.

Conclusion

This study shows that age is a simple but not sufficiently accurate criterion to define potential candidates for CRC screening. As automated reminders often prompt discussions about and referral to screening examinations, we should develop algorithms that estimate the individual cancer risk and/or integrate an automatically calculated comorbidity index with these alerts or insert such a tool into order-sets. In addition, providers and patients need to be educated about the rationale and need for a more comprehensive approach to CRC screening that considers anticipated life expectancy. On an individual and health system level, our goal should be to reduce overall mortality rather than only cancer-specific death rates.

1. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323.

2. Kahi CJ, Myers LJ, Slaven JE, et al. Lower endoscopy reduces colorectal cancer incidence in older individuals. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):718-725.e3.

3. Wang YR, Cangemi JR, Loftus EV Jr, Picco MF. Decreased risk of colorectal cancer after colonoscopy in patients 76-85 years old in the United States. Digestion. 2016;93(2):132-138.

4. van Hees F, Saini SD, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. Personalizing colonoscopy screening for elderly individuals based on screening history, cancer risk, and comorbidity status could increase cost effectiveness. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1425-1437.

5. May FP, Yano EM, Provenzale D, Steers NW, Washington DL. The association between primary source of healthcare coverage and colorectal cancer screening among US veterans. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(8):1923-1932.

6. Kahi CJ, Pohl H, Myers LJ, Mobarek D, Robertson DJ, Imperiale TF. Colonoscopy and colorectal cancer mortality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System: a case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(7):481-488.

7. Holt PR, Kozuch P, Mewar S. Colon cancer and the elderly: from screening to treatment in management of GI disease in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23(6):889-907.

8. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245-1251.

9. Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(19):1365-1371.

10. Lee TA, Shields AE, Vogeli C, et al. Mortality rate in veterans with multiple chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(suppl 3):403-407.

11. Nguyen-Nielsen M, Norgaard M, Jacobsen JB, et al. Comorbidity and survival of Danish prostate cancer patients from 2000-2011: a population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5(suppl 1):47-55.

12. Jang SH, Chea JW, Lee KB. Charlson comorbidity index using administrative database in incident PD patients. Clin Nephrol. 2010;73(3):204-209.

13. Fried L, Bernardini J, Piraino B. Charlson comorbidity index as a predictor of outcomes in incident peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37(2):337-342.

14. Gross CP, Soulos PR, Ross JS, et al. Assessing the impact of screening colonoscopy on mortality in the medicare population. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1441-1449.

15. Chouhan V, Mansoor E, Parasa S, Cooper GS. Rates of prevalent colorectal cancer occurrence in persons 75 years of age and older: a population-based national study. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(7):1929-1936.

16. Lee SJ, Kim CM. Individualizing prevention for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(2):229-234.

17. Tang V, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, et al. Time to benefit for colorectal cancer screening: survival meta-analysis of flexible sigmoidoscopy trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1662.

18. Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, et al. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441.

19. Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Gulati R, Mariotto AB, et al. Personalizing age of cancer screening cessation based on comorbid conditions: model estimates of harms and benefits. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(2):104-112.

20. Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL II, Cayea D, Pollack CE, Feeser S, Boyd C. Primary care practitioners’ views on incorporating long-term prognosis in the care of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):671-678.

21. Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1121-1128.

22. Lewis CL, Esserman D, DeLeon C, Pignone MP, Pathman DE, Golin C. Physician decision making for colorectal cancer screening in the elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1202-1217.

23. Saini SD, Vijan S, Schoenfeld P, Powell AA, Moser S, Kerr EA. Role of quality measurement in inappropriate use of screening for colorectal cancer: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1247.

24. Walter LC, Lindquist K, Nugent S, et al. Impact of age and comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening among older veterans. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(7):465-473.

25. Powell AA, Saini SD, Breitenstein MK, et al. Rates and correlates of potentially inappropriate colorectal cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):732-741.

26. Pollack CE, Blackford AL, Schoenborn NL, Boyd CM, Peairs KS, DuGoff EH. Comparing prognostic tools for cancer screening: considerations for clinical practice and performance assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(5):1032-1038.

27. So C, Kirby KA, Mehta K, et al. Medical center characteristics associated with PSA screening in elderly veterans with limited life expectancy. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(6):653-660.

28. Tang VL, Shi Y, Fung K, et al. Clinician factors associated with prostate-specific antigen screening in older veterans with limited life expectancy. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):654-661.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks among the most common causes of cancer and cancer-related death in the US. The US Multi-Society Task Force (USMSTF) on Colorectal Cancer thus strongly endorsed using several available screening options.1 The published guidelines largely rely on age to define the target population (Table 1). For average-risk individuals, national and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) guidelines currently recommend CRC screening in individuals aged between 50 and 75 years with a life expectancy of > 5 years.1

Although case-control studies also point to a potential benefit in persons aged > 75 years,2,3 the USMSTF cited less convincing evidence and suggested an individualized approach that should consider relative cancer risk and comorbidity burden. Such an approach is supported by modeling studies, which suggest reduced benefit and increased risk of screening with increasing age. The reduced benefit also is significantly affected by comorbidity and relative cancer risk.4 The VHA has successfully implemented CRC screening, capturing the majority of eligible patients based on age criteria. A recent survey showed that more than three-quarters of veterans between age 50 and 75 years had undergone some screening test for CRC as part of routine preventive care. Colonoscopy clearly emerged as the dominant modality chosen for CRC screening and accounted for nearly 84% of these screening tests.5 Consistent with these data, a case-control study confirmed that the widespread implementation of colonoscopy as CRC screening method reduced cancer-related mortality in veterans for cases of left but not right-sided colon cancer.6

With calls to expand the age range of CRC screening beyond aged 75 years, we decided to assess survival rates of a cohort of veterans who underwent a screening or surveillance colonoscopy between 2008 and 2014.7 The goals were to characterize the portion of the cohort that had died, the time between a screening colonoscopy and death, the portion of deaths that were aged ≥ 80 years, and the causes of the deaths. In addition, we focused on a subgroup of the cohort, defined by death within 2 years after the index colonoscopy, to identify predictors of early death that were independent of age.

Methods

We queried the endoscopy reporting system (EndoWorks; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) for all colonoscopies performed by 2 of 14 physicians at the George Wahlen VA Medical Center (GWVAMC) in Salt Lake City, Utah, who performed endoscopic procedures between January 1, 2008 and December 1, 2014. These physicians had focused their clinical practice exclusively on elective outpatient colonoscopies and accounted for 37.4% of the examinations at GWVAMC during the study period. All colonoscopy requests were triaged and assigned based on availability of open and appropriate procedure time slots without direct physician-specific referral, thus reducing the chance of skewing results. The reports were filtered through a text search to focus on examinations that listed screening or surveillance as indication. The central patient electronic health record was then reviewed to extract basic demographic data, survival status (as of August 1, 2018), and survival time in years after the index or subsequent colonoscopy. For deceased veterans, the age at the time of death, cause of death, and comorbidities were queried.

This study compared cases and control across the study. Cases were persons who clearly died early (defined as > 2 years following the index examination). They were matched with controls who lived for ≥ 5 years after their colonoscopy. These periods were selected because the USMSTF recommended that CRC screening or surveillance colonoscopy should be discontinued in persons with a life expectancy of < 5 years, and most study patients underwent their index procedure ≥ 5 years before August 2018. Cases and controls underwent a colonoscopy in the same year and were matched for age, sex, and presence of underlying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For cases and controls, we identified the ordering health care provider specialty, (ie, primary care, gastroenterology, or other).

In addition, we reviewed the encounter linked to the order and abstracted relevant comorbidities listed at that time, noted the use of anticoagulants, opioid analgesics, and benzodiazepines. The comorbidity burden was quantified using the Charlson Comorbidity Index.8 In addition, we denoted the presence of psychiatric problems (eg, anxiety, depression, bipolar disease, psychosis, substance abuse), the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation (AF) or other cardiac arrhythmias, and whether the patient had previously been treated for a malignancy that was in apparent clinical remission. Finally, we searched for routine laboratory tests at the time of this visit or, when not obtained, within 6 months of the encounter, and abstracted serum creatinine, hemoglobin (Hgb), platelet number, serum protein, and albumin. In clinical practice, cutoff values of test results are often more helpful in decision making. We, therefore, dichotomized results for Hgb (cutoff: 10 g/dL), creatinine (cutoff: 2 mg/dL), and albumin (cutoff: 3.2 mg/dL).

Descriptive and analytical statistics were obtained with Stata Version 14.1 (College Station, TX). Unless indicated otherwise, continuous data are shown as mean with 95% CIs. For dichotomous data, we used percentages with their 95% CIs. Analytic statistics were performed with the t test for continuous variables and the 2-tailed test for proportions. A P < .05 was considered a significant difference. To determine independent predictors of early death, we performed a logistic regression analysis with results being expressed as odds ratio with 95% CIs. Survival status was chosen as a dependent variable, and we entered variables that significantly correlated with survival in the bivariate analysis as independent variables.

The study was designed and conducted as a quality improvement project to assess colonoscopy performance and outcomes with the Salt Lake City Specialty Care Center of Innovation (COI), one of 5 regional COIs with an operational mission to improve health care access, utilization, and quality. Our work related to colonoscopy and access within the COI region, including Salt Lake City, has been reviewed and acknowledged by the GWVAMC Institutional Review Board as quality improvement. Andrew Gawron has an operational appointment in the GWVAMC COI, which is part of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) central office initiative established in 2015. The COIs are charged with identifying best practices within the VA and applying those practices throughout the COI region. This local project to identify practice patterns and outcomes locally was sponsored by the GWVAMC COI with a focus to generate information to improve colonoscopy referral quality in patients at Salt Lake City and inform regional and national efforts in this domain.

Results

During the study period, 4,879 veterans (96.9% male) underwent at least 1 colonoscopy for screening or surveillance by 1 of the 2 providers. A total of 306 persons (6.3%) were aged > 80 years. The indication for surveillance colonoscopies included IBD in 78 (1.6%) veterans 2 of whom were women. The mean (SD) follow-up period between the index colonoscopy and study closure or death was 7.4 years (1.7). During the study time, 1,439 persons underwent a repeat examination for surveillance. The percentage of veterans with at least 1 additional colonoscopy after the index test was significantly higher in patients with known IBD compared with those without IBD (78.2% vs 28.7%; P < .01).

Between the index colonoscopy and August 2018, 974 patients (20.0%) died (Figure). The mean (SD) time between the colonoscopy and recorded year of death was 4.4 years (4.1). The fraction of women in the cohort that died (n = 18) was lower compared with 132 for the group of persons still alive (1.8% vs 3.4%; P < .05). The fraction of veterans with IBD who died by August 2018 did not differ from that of patients with IBD in the cohort of individuals who survived (19.2% vs 20.0%; P = .87). The cohort of veterans who died before study closure included 107 persons who were aged > 80 years at the time of their index colonoscopy, which is significantly more than in the cohort of persons still alive (11.0% vs 5.1%; P < .01).

Cause of Death

In 209 of the 974 (21.5%) veteran deaths a cause was recorded. Malignancies accounted for 88 of the deaths (42.1%), and CRCs were responsible for 14 (6.7%) deaths (Table 2). In 8 of these patients, the cancer had been identified at an advanced stage, not allowing for curative therapy. One patient had been asked to return for a repeat test as residual fecal matter did not allow proper visualization. He died 1 year later due to complications of sepsis after colonic perforation caused by a proximal colon cancer. Five patients underwent surgery with curative intent but suffered recurrences. In addition to malignancies, advanced diseases, such as cardiovascular, bronchopulmonary illnesses, and infections, were other commonly listed causes of death.

We also abstracted comorbidities that were known at the time of death or the most recent encounter within the VHA system. Hypertension was most commonly listed (549) followed by a current or prior diagnosis of malignancies (355) and diabetes mellitus (DM) (Table 3). Prostate cancer was the most commonly diagnosed malignancy (80), 17 of whom had a second malignancy. CRC accounted for 54 of the malignancies, 1 of which developed in a patient with long-standing ulcerative colitis, 2 were a manifestation of a known hereditary cancer syndrome (Lynch syndrome), and the remaining 51 cases were various cancers without known predisposition. The diagnosis of CRC was made during the study period in 29 veterans. In the remaining 25 patients, the colonoscopy was performed as a surveillance examination after previous surgery for CRC.

Potential Predictors of Early Death

To better define potential predictors of early death, we focused on the 258 persons (5.3%) who died within 2 years after the index procedure and paired them with matched controls. One patient underwent a colonoscopy for surveillance of previously treated cancer and was excluded due to very advanced age, as no matched control could be identified. The mean (SD) age of this male-predominant cohort was 68.2 (9.6) vs 67.9 (9.4) years for cases and controls, respectively. At the time of referral for the test, 29 persons (11.3%) were aged > 80 years, which is significantly more than seen for the overall cohort with 306 (6.3%; P < .001). While primary care providers accounted for most referrals in cases (85.2%) and controls (93.0%), the fraction of veterans referred by gastroenterologists or other specialty care providers was significantly higher in the case group compared with that in the controls (14.8% vs 7.0%; P < .05).

In our age-matched analysis, we examined other potential factors that could influence survival. The burden of comorbid conditions summarized in the Charlson Comorbidity Index significantly correlated with survival status (Table 4). As this composite index does not include psychiatric conditions, we separately examined the impact of anxiety, depression, bipolar disease, psychotic disorders, and substance abuse. The diagnoses of depression and substance use disorders (SUDs) were associated with higher rates of early death. Considering concerns about SUDs, we also assessed the association between prescription for opioids or benzodiazepines and survival status, which showed a marginal correlation. Anticoagulant use, a likely surrogate for cardiovascular disorders, were more commonly listed in the cases than they were in the controls.

Looking at specific comorbid conditions, significant problems affecting key organ systems from heart to lung, liver, kidneys, or brain (dementia) were all predictors of poor outcome. Similarly, DM with secondary complication correlated with early death after the index procedure. In contrast, a history of prior myocardial infarction, prior cancer treatment without evidence of persistent or recurrent disease, or prior peptic ulcer disease did not differ between cases and controls. Focusing on routine blood tests, we noted marginal, but statistically different results for Hgb, serum creatinine, and albumin in cases compared with controls.

Next we performed a logistic regression to identify independent predictors of survival status. The referring provider specialty, Charlson Comorbidity Index, the diagnosis of a SUD, current benzodiazepine use, and significant anemia or hypoalbuminemia independently predicted death within 2 years of the index examination (Table 5). Considering the composite nature of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, we separately examined the relative importance of different comorbid conditions using a logistic regression analysis. Consistent with the univariate analyses, a known malignancy; severe liver, lung, or kidney disease; and DM with secondary complications were associated with poor outcome. Only arrhythmias other than AF were independent marginal predictors of early death, whereas other variables related to cardiac performance did not reach the level of significance (Table 6). As was true for our analysis examining the composite comorbidity index, the diagnosis of a SUD remained significant as a predictor of death within 2 years of the index colonoscopy.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis followed patients for a mean time of 7 years after a colonoscopy for CRC screening or polyp surveillance. We noted a high rate of all-cause mortality, with 20% of the cohort dying within the period studied. Malignancies, cardiovascular diseases, and advanced lung diseases were most commonly listed causes of death. As expected, CRC was among the 3 most common malignancies and was the cause of death in 6.7% of the group with sufficiently detailed information. While these results fall within the expected range for the mortality related to CRC,9 the results do not allow us to assess the impact of screening, which has been shown to decrease cancer-related mortality in veterans.6 This was limited because the sample size was too small to assess the impact of screening and the cause of death was ascertained for a small percentage of the sample.

Although our findings are limited to a subset of patients seen in a single center, they suggest the importance of appropriate eligibility criteria for screening tests, as also defined in national guidelines.1 As a key anchoring point that describes the target population, age contributed to the rate of relatively early death after the index procedure. Consistent with previously published data, we saw a significant impact of comorbid diseases.10,11 However, our findings go beyond prior reports and show the important impact of psychiatric disease burden, most important the role of SUDs. The predictive value of a summary score, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index, supports the idea of a cumulative impact, with an increasing disease burden decreasing life expectancy.10-14 It is important to consider the ongoing impact of such coexisting illnesses. Our analysis shows, the mere history of prior problems did not independently predict survival status in our cohort.

Although age is the key anchoring point that defines the target population for CRC screening programs, the benefit of earlier cancer detection or, in the context of colonoscopy with polypectomy, cancer prevention comes with a delay. Thus, cancer risk, procedural risk, and life expectancy should all be weighed when discussing and deciding on the appropriateness of CRC screening. When we disregard inherited cancer syndromes, CRC is clearly a disease of the second half of life with the incidence increasing with age.15 However, other disease burdens rise, which may affects the risk of screening and treatment should cancer be found.

Using our understanding of disease development, researchers have introduced the concept of time to benefit or lag time to help decisions about screening strategies. The period defines the likely time for a precursor or early form of cancer potentially detected by screening to manifest as a clinically relevant lesion. This lag time becomes an especially important consideration in screening of older and/or chronically ill adults with life expectancies that may be close to or even less than the time to benefit.16 Modeling studies suggest that 1,000 flexible sigmoidoscopy screenings are needed to prevent 1 cancer that would manifest about 10 years after the index examination.17,18 The mean life expectancy of a healthy person aged 75 years exceeds 10 years but drops with comorbidity burden. Consistent with these considerations, an analysis of Medicare claims data concluded that individuals with ≥ 3 significant comorbidities do not derive any benefit from screening colonoscopy.14 Looking at the impact of comorbidities, mathematical models concluded that colorectal cancer screening should not be continued in persons with moderate or severe comorbid conditions aged 66 years and 72 years, respectively.19 In contrast, modeling results suggest a benefit of continued screening up to and even above the age of 80 years if persons have an increased cancer risk and if there are no confounding comorbidities.4

Life expectancy and time to benefit describe probabilities. Although such probabilities are relevant in public policy decision, providers and patients may struggle with probabilistic thinking when faced with decisions that involve probabilities of individual health care vs population health care. Both are concerned about the seemingly gloomy or pessimistic undertone of discussing life expectancy and the inherent uncertainty of prognostic tools.20,21 Prior research indicates that this reluctance translates into clinical practice. When faced with vignettes, most clinicians would offer CRC screening to healthy persons aged 80 years with rates falling when the description included a significant comorbid burden; however, more than 40% would still consider screening in octogenarians with poor health.22

Consistent with these responses to theoretical scenarios, CRC screening of veterans dropped with age but was still continued in persons with significant comorbidity.23 Large studies of the veteran population suggest that about 10% of veterans aged > 70 years have chronic medical problems that limit their life expectancy to < 5 years; nonetheless, more than 40% of this cohort underwent colonoscopies for CRC screening.24,25 Interestingly, more illness burden and more clinical encounters translated into more screening examinations in older sick veterans compared with that of the cohort of healthier older persons, suggesting an impact of clinical reminders and the key role of age as the main anchoring variable.23

Ongoing screening despite limited or even no benefit is not unique to CRC. Using validated tools, Pollock and colleagues showed comparable screening rates for breast and prostate cancer when they examined cohorts at either high or low risk of early mortality.26 Similar results have been reported in veterans with about one-third of elderly males with poor life expectancy still undergoing prostate cancer screening.27 Interestingly, inappropriate screening is more common in nonacademic centers and influenced by provider characteristics: nurse practitioner, physician assistants, older attending physicians and male physicians were more likely to order such tests.27,28

Limitations

In this study, we examined a cohort of veterans enrolled in CRC screening within a single institution and obtained survival data for a mean follow-up of > 7 years. We also restricted our study to patients undergoing examinations that explicitly listed screening as indication or polyp surveillance for the test. However, inclusion was based on the indication listed in the report, which may differ from the intent of the ordering provider. Reporting systems often come with default settings, which may skew data. Comorbidities for the entire cohort of veterans who died within the time frame of the study were extracted from the chart without controlling for time-dependent changes, which may more appropriately describe the comorbidity burden at the time of the test. Using a case-control design, we addressed this potential caveat and included only illnesses recorded in the encounter linked to the colonoscopy order. Despite these limitations, our results highlight the importance to more effectively define and target appropriate candidates for CRC screening.

Conclusion

This study shows that age is a simple but not sufficiently accurate criterion to define potential candidates for CRC screening. As automated reminders often prompt discussions about and referral to screening examinations, we should develop algorithms that estimate the individual cancer risk and/or integrate an automatically calculated comorbidity index with these alerts or insert such a tool into order-sets. In addition, providers and patients need to be educated about the rationale and need for a more comprehensive approach to CRC screening that considers anticipated life expectancy. On an individual and health system level, our goal should be to reduce overall mortality rather than only cancer-specific death rates.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks among the most common causes of cancer and cancer-related death in the US. The US Multi-Society Task Force (USMSTF) on Colorectal Cancer thus strongly endorsed using several available screening options.1 The published guidelines largely rely on age to define the target population (Table 1). For average-risk individuals, national and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) guidelines currently recommend CRC screening in individuals aged between 50 and 75 years with a life expectancy of > 5 years.1

Although case-control studies also point to a potential benefit in persons aged > 75 years,2,3 the USMSTF cited less convincing evidence and suggested an individualized approach that should consider relative cancer risk and comorbidity burden. Such an approach is supported by modeling studies, which suggest reduced benefit and increased risk of screening with increasing age. The reduced benefit also is significantly affected by comorbidity and relative cancer risk.4 The VHA has successfully implemented CRC screening, capturing the majority of eligible patients based on age criteria. A recent survey showed that more than three-quarters of veterans between age 50 and 75 years had undergone some screening test for CRC as part of routine preventive care. Colonoscopy clearly emerged as the dominant modality chosen for CRC screening and accounted for nearly 84% of these screening tests.5 Consistent with these data, a case-control study confirmed that the widespread implementation of colonoscopy as CRC screening method reduced cancer-related mortality in veterans for cases of left but not right-sided colon cancer.6

With calls to expand the age range of CRC screening beyond aged 75 years, we decided to assess survival rates of a cohort of veterans who underwent a screening or surveillance colonoscopy between 2008 and 2014.7 The goals were to characterize the portion of the cohort that had died, the time between a screening colonoscopy and death, the portion of deaths that were aged ≥ 80 years, and the causes of the deaths. In addition, we focused on a subgroup of the cohort, defined by death within 2 years after the index colonoscopy, to identify predictors of early death that were independent of age.

Methods

We queried the endoscopy reporting system (EndoWorks; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) for all colonoscopies performed by 2 of 14 physicians at the George Wahlen VA Medical Center (GWVAMC) in Salt Lake City, Utah, who performed endoscopic procedures between January 1, 2008 and December 1, 2014. These physicians had focused their clinical practice exclusively on elective outpatient colonoscopies and accounted for 37.4% of the examinations at GWVAMC during the study period. All colonoscopy requests were triaged and assigned based on availability of open and appropriate procedure time slots without direct physician-specific referral, thus reducing the chance of skewing results. The reports were filtered through a text search to focus on examinations that listed screening or surveillance as indication. The central patient electronic health record was then reviewed to extract basic demographic data, survival status (as of August 1, 2018), and survival time in years after the index or subsequent colonoscopy. For deceased veterans, the age at the time of death, cause of death, and comorbidities were queried.

This study compared cases and control across the study. Cases were persons who clearly died early (defined as > 2 years following the index examination). They were matched with controls who lived for ≥ 5 years after their colonoscopy. These periods were selected because the USMSTF recommended that CRC screening or surveillance colonoscopy should be discontinued in persons with a life expectancy of < 5 years, and most study patients underwent their index procedure ≥ 5 years before August 2018. Cases and controls underwent a colonoscopy in the same year and were matched for age, sex, and presence of underlying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For cases and controls, we identified the ordering health care provider specialty, (ie, primary care, gastroenterology, or other).

In addition, we reviewed the encounter linked to the order and abstracted relevant comorbidities listed at that time, noted the use of anticoagulants, opioid analgesics, and benzodiazepines. The comorbidity burden was quantified using the Charlson Comorbidity Index.8 In addition, we denoted the presence of psychiatric problems (eg, anxiety, depression, bipolar disease, psychosis, substance abuse), the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation (AF) or other cardiac arrhythmias, and whether the patient had previously been treated for a malignancy that was in apparent clinical remission. Finally, we searched for routine laboratory tests at the time of this visit or, when not obtained, within 6 months of the encounter, and abstracted serum creatinine, hemoglobin (Hgb), platelet number, serum protein, and albumin. In clinical practice, cutoff values of test results are often more helpful in decision making. We, therefore, dichotomized results for Hgb (cutoff: 10 g/dL), creatinine (cutoff: 2 mg/dL), and albumin (cutoff: 3.2 mg/dL).

Descriptive and analytical statistics were obtained with Stata Version 14.1 (College Station, TX). Unless indicated otherwise, continuous data are shown as mean with 95% CIs. For dichotomous data, we used percentages with their 95% CIs. Analytic statistics were performed with the t test for continuous variables and the 2-tailed test for proportions. A P < .05 was considered a significant difference. To determine independent predictors of early death, we performed a logistic regression analysis with results being expressed as odds ratio with 95% CIs. Survival status was chosen as a dependent variable, and we entered variables that significantly correlated with survival in the bivariate analysis as independent variables.

The study was designed and conducted as a quality improvement project to assess colonoscopy performance and outcomes with the Salt Lake City Specialty Care Center of Innovation (COI), one of 5 regional COIs with an operational mission to improve health care access, utilization, and quality. Our work related to colonoscopy and access within the COI region, including Salt Lake City, has been reviewed and acknowledged by the GWVAMC Institutional Review Board as quality improvement. Andrew Gawron has an operational appointment in the GWVAMC COI, which is part of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) central office initiative established in 2015. The COIs are charged with identifying best practices within the VA and applying those practices throughout the COI region. This local project to identify practice patterns and outcomes locally was sponsored by the GWVAMC COI with a focus to generate information to improve colonoscopy referral quality in patients at Salt Lake City and inform regional and national efforts in this domain.

Results

During the study period, 4,879 veterans (96.9% male) underwent at least 1 colonoscopy for screening or surveillance by 1 of the 2 providers. A total of 306 persons (6.3%) were aged > 80 years. The indication for surveillance colonoscopies included IBD in 78 (1.6%) veterans 2 of whom were women. The mean (SD) follow-up period between the index colonoscopy and study closure or death was 7.4 years (1.7). During the study time, 1,439 persons underwent a repeat examination for surveillance. The percentage of veterans with at least 1 additional colonoscopy after the index test was significantly higher in patients with known IBD compared with those without IBD (78.2% vs 28.7%; P < .01).

Between the index colonoscopy and August 2018, 974 patients (20.0%) died (Figure). The mean (SD) time between the colonoscopy and recorded year of death was 4.4 years (4.1). The fraction of women in the cohort that died (n = 18) was lower compared with 132 for the group of persons still alive (1.8% vs 3.4%; P < .05). The fraction of veterans with IBD who died by August 2018 did not differ from that of patients with IBD in the cohort of individuals who survived (19.2% vs 20.0%; P = .87). The cohort of veterans who died before study closure included 107 persons who were aged > 80 years at the time of their index colonoscopy, which is significantly more than in the cohort of persons still alive (11.0% vs 5.1%; P < .01).

Cause of Death

In 209 of the 974 (21.5%) veteran deaths a cause was recorded. Malignancies accounted for 88 of the deaths (42.1%), and CRCs were responsible for 14 (6.7%) deaths (Table 2). In 8 of these patients, the cancer had been identified at an advanced stage, not allowing for curative therapy. One patient had been asked to return for a repeat test as residual fecal matter did not allow proper visualization. He died 1 year later due to complications of sepsis after colonic perforation caused by a proximal colon cancer. Five patients underwent surgery with curative intent but suffered recurrences. In addition to malignancies, advanced diseases, such as cardiovascular, bronchopulmonary illnesses, and infections, were other commonly listed causes of death.

We also abstracted comorbidities that were known at the time of death or the most recent encounter within the VHA system. Hypertension was most commonly listed (549) followed by a current or prior diagnosis of malignancies (355) and diabetes mellitus (DM) (Table 3). Prostate cancer was the most commonly diagnosed malignancy (80), 17 of whom had a second malignancy. CRC accounted for 54 of the malignancies, 1 of which developed in a patient with long-standing ulcerative colitis, 2 were a manifestation of a known hereditary cancer syndrome (Lynch syndrome), and the remaining 51 cases were various cancers without known predisposition. The diagnosis of CRC was made during the study period in 29 veterans. In the remaining 25 patients, the colonoscopy was performed as a surveillance examination after previous surgery for CRC.

Potential Predictors of Early Death

To better define potential predictors of early death, we focused on the 258 persons (5.3%) who died within 2 years after the index procedure and paired them with matched controls. One patient underwent a colonoscopy for surveillance of previously treated cancer and was excluded due to very advanced age, as no matched control could be identified. The mean (SD) age of this male-predominant cohort was 68.2 (9.6) vs 67.9 (9.4) years for cases and controls, respectively. At the time of referral for the test, 29 persons (11.3%) were aged > 80 years, which is significantly more than seen for the overall cohort with 306 (6.3%; P < .001). While primary care providers accounted for most referrals in cases (85.2%) and controls (93.0%), the fraction of veterans referred by gastroenterologists or other specialty care providers was significantly higher in the case group compared with that in the controls (14.8% vs 7.0%; P < .05).

In our age-matched analysis, we examined other potential factors that could influence survival. The burden of comorbid conditions summarized in the Charlson Comorbidity Index significantly correlated with survival status (Table 4). As this composite index does not include psychiatric conditions, we separately examined the impact of anxiety, depression, bipolar disease, psychotic disorders, and substance abuse. The diagnoses of depression and substance use disorders (SUDs) were associated with higher rates of early death. Considering concerns about SUDs, we also assessed the association between prescription for opioids or benzodiazepines and survival status, which showed a marginal correlation. Anticoagulant use, a likely surrogate for cardiovascular disorders, were more commonly listed in the cases than they were in the controls.

Looking at specific comorbid conditions, significant problems affecting key organ systems from heart to lung, liver, kidneys, or brain (dementia) were all predictors of poor outcome. Similarly, DM with secondary complication correlated with early death after the index procedure. In contrast, a history of prior myocardial infarction, prior cancer treatment without evidence of persistent or recurrent disease, or prior peptic ulcer disease did not differ between cases and controls. Focusing on routine blood tests, we noted marginal, but statistically different results for Hgb, serum creatinine, and albumin in cases compared with controls.

Next we performed a logistic regression to identify independent predictors of survival status. The referring provider specialty, Charlson Comorbidity Index, the diagnosis of a SUD, current benzodiazepine use, and significant anemia or hypoalbuminemia independently predicted death within 2 years of the index examination (Table 5). Considering the composite nature of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, we separately examined the relative importance of different comorbid conditions using a logistic regression analysis. Consistent with the univariate analyses, a known malignancy; severe liver, lung, or kidney disease; and DM with secondary complications were associated with poor outcome. Only arrhythmias other than AF were independent marginal predictors of early death, whereas other variables related to cardiac performance did not reach the level of significance (Table 6). As was true for our analysis examining the composite comorbidity index, the diagnosis of a SUD remained significant as a predictor of death within 2 years of the index colonoscopy.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis followed patients for a mean time of 7 years after a colonoscopy for CRC screening or polyp surveillance. We noted a high rate of all-cause mortality, with 20% of the cohort dying within the period studied. Malignancies, cardiovascular diseases, and advanced lung diseases were most commonly listed causes of death. As expected, CRC was among the 3 most common malignancies and was the cause of death in 6.7% of the group with sufficiently detailed information. While these results fall within the expected range for the mortality related to CRC,9 the results do not allow us to assess the impact of screening, which has been shown to decrease cancer-related mortality in veterans.6 This was limited because the sample size was too small to assess the impact of screening and the cause of death was ascertained for a small percentage of the sample.

Although our findings are limited to a subset of patients seen in a single center, they suggest the importance of appropriate eligibility criteria for screening tests, as also defined in national guidelines.1 As a key anchoring point that describes the target population, age contributed to the rate of relatively early death after the index procedure. Consistent with previously published data, we saw a significant impact of comorbid diseases.10,11 However, our findings go beyond prior reports and show the important impact of psychiatric disease burden, most important the role of SUDs. The predictive value of a summary score, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index, supports the idea of a cumulative impact, with an increasing disease burden decreasing life expectancy.10-14 It is important to consider the ongoing impact of such coexisting illnesses. Our analysis shows, the mere history of prior problems did not independently predict survival status in our cohort.

Although age is the key anchoring point that defines the target population for CRC screening programs, the benefit of earlier cancer detection or, in the context of colonoscopy with polypectomy, cancer prevention comes with a delay. Thus, cancer risk, procedural risk, and life expectancy should all be weighed when discussing and deciding on the appropriateness of CRC screening. When we disregard inherited cancer syndromes, CRC is clearly a disease of the second half of life with the incidence increasing with age.15 However, other disease burdens rise, which may affects the risk of screening and treatment should cancer be found.