User login

Study: CMV doesn’t lower risk of relapse, death

Small studies have suggested that early cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation may protect against leukemia relapse and even death after hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

However, a new study, based on data from about 9500 patients, suggests otherwise.

Results showed no association between CMV reactivation and relapse but suggested CMV reactivation increases the risk of non-relapse mortality.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“The original purpose of the study was to confirm that CMV infection may prevent leukemia relapse, prevent death, and become a major therapeutic tool for improving patient survival rates,” said study author Pierre Teira, MD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

“However, we found the exact opposite. Our results clearly show that . . . the virus not only does not prevent leukemia relapse [it] also remains a major factor associated with the risk of death. Monitoring of CMV after transplantation remains a priority for patients.”

For this study, Dr Teira and his colleagues analyzed data from 9469 patients who received a transplant between 2003 and 2010.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=5310), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL, n=1883), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=1079), or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=1197).

The median time to initial CMV reactivation was 41 days (range, 1-362 days).

The researchers found no significant association between CMV reactivation and disease relapse for AML (P=0.60), ALL (P=0.08), CML (P=0.94), or MDS (P=0.58).

However, CMV reactivation was associated with a significantly higher risk of nonrelapse mortality for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0004), and MDS (P=0.0002).

Therefore, CMV reactivation was associated with significantly lower overall survival for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0005), and MDS (P=0.003).

“Deaths due to uncontrolled CMV reactivation are virtually zero in this study, so uncontrolled CMV reactivation is not what reduces survival rates after transplantation,” Dr Teira noted. “The link between this common virus and increased risk of death remains a biological mystery.”

One possible explanation is that CMV decreases the ability of the patient’s immune system to fight against other types of infection. This is supported by the fact that death rates from infections other than CMV are higher in patients infected with CMV or patients whose donors were.

For researchers, the next step is therefore to verify whether the latest generation of anti-CMV treatments can prevent both reactivation of the virus and weakening of the patient’s immune system against other types of infection in the presence of CMV infection.

“CMV has a complex impact on the outcomes for transplant patients, and, each year, more than 30,000 patients around the world receive bone marrow transplants from donors,” Dr Teira said.

“It is therefore essential for future research to better understand the role played by CMV after bone marrow transplantation and improve the chances of success of the transplant. This will help to better choose the right donor for the right patient.” ![]()

Small studies have suggested that early cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation may protect against leukemia relapse and even death after hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

However, a new study, based on data from about 9500 patients, suggests otherwise.

Results showed no association between CMV reactivation and relapse but suggested CMV reactivation increases the risk of non-relapse mortality.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“The original purpose of the study was to confirm that CMV infection may prevent leukemia relapse, prevent death, and become a major therapeutic tool for improving patient survival rates,” said study author Pierre Teira, MD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

“However, we found the exact opposite. Our results clearly show that . . . the virus not only does not prevent leukemia relapse [it] also remains a major factor associated with the risk of death. Monitoring of CMV after transplantation remains a priority for patients.”

For this study, Dr Teira and his colleagues analyzed data from 9469 patients who received a transplant between 2003 and 2010.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=5310), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL, n=1883), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=1079), or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=1197).

The median time to initial CMV reactivation was 41 days (range, 1-362 days).

The researchers found no significant association between CMV reactivation and disease relapse for AML (P=0.60), ALL (P=0.08), CML (P=0.94), or MDS (P=0.58).

However, CMV reactivation was associated with a significantly higher risk of nonrelapse mortality for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0004), and MDS (P=0.0002).

Therefore, CMV reactivation was associated with significantly lower overall survival for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0005), and MDS (P=0.003).

“Deaths due to uncontrolled CMV reactivation are virtually zero in this study, so uncontrolled CMV reactivation is not what reduces survival rates after transplantation,” Dr Teira noted. “The link between this common virus and increased risk of death remains a biological mystery.”

One possible explanation is that CMV decreases the ability of the patient’s immune system to fight against other types of infection. This is supported by the fact that death rates from infections other than CMV are higher in patients infected with CMV or patients whose donors were.

For researchers, the next step is therefore to verify whether the latest generation of anti-CMV treatments can prevent both reactivation of the virus and weakening of the patient’s immune system against other types of infection in the presence of CMV infection.

“CMV has a complex impact on the outcomes for transplant patients, and, each year, more than 30,000 patients around the world receive bone marrow transplants from donors,” Dr Teira said.

“It is therefore essential for future research to better understand the role played by CMV after bone marrow transplantation and improve the chances of success of the transplant. This will help to better choose the right donor for the right patient.” ![]()

Small studies have suggested that early cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation may protect against leukemia relapse and even death after hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

However, a new study, based on data from about 9500 patients, suggests otherwise.

Results showed no association between CMV reactivation and relapse but suggested CMV reactivation increases the risk of non-relapse mortality.

Researchers reported these findings in Blood.

“The original purpose of the study was to confirm that CMV infection may prevent leukemia relapse, prevent death, and become a major therapeutic tool for improving patient survival rates,” said study author Pierre Teira, MD, of the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

“However, we found the exact opposite. Our results clearly show that . . . the virus not only does not prevent leukemia relapse [it] also remains a major factor associated with the risk of death. Monitoring of CMV after transplantation remains a priority for patients.”

For this study, Dr Teira and his colleagues analyzed data from 9469 patients who received a transplant between 2003 and 2010.

The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=5310), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL, n=1883), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n=1079), or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=1197).

The median time to initial CMV reactivation was 41 days (range, 1-362 days).

The researchers found no significant association between CMV reactivation and disease relapse for AML (P=0.60), ALL (P=0.08), CML (P=0.94), or MDS (P=0.58).

However, CMV reactivation was associated with a significantly higher risk of nonrelapse mortality for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0004), and MDS (P=0.0002).

Therefore, CMV reactivation was associated with significantly lower overall survival for AML (P<0.0001), ALL (P<0.0001), CML (P=0.0005), and MDS (P=0.003).

“Deaths due to uncontrolled CMV reactivation are virtually zero in this study, so uncontrolled CMV reactivation is not what reduces survival rates after transplantation,” Dr Teira noted. “The link between this common virus and increased risk of death remains a biological mystery.”

One possible explanation is that CMV decreases the ability of the patient’s immune system to fight against other types of infection. This is supported by the fact that death rates from infections other than CMV are higher in patients infected with CMV or patients whose donors were.

For researchers, the next step is therefore to verify whether the latest generation of anti-CMV treatments can prevent both reactivation of the virus and weakening of the patient’s immune system against other types of infection in the presence of CMV infection.

“CMV has a complex impact on the outcomes for transplant patients, and, each year, more than 30,000 patients around the world receive bone marrow transplants from donors,” Dr Teira said.

“It is therefore essential for future research to better understand the role played by CMV after bone marrow transplantation and improve the chances of success of the transplant. This will help to better choose the right donor for the right patient.” ![]()

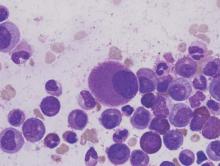

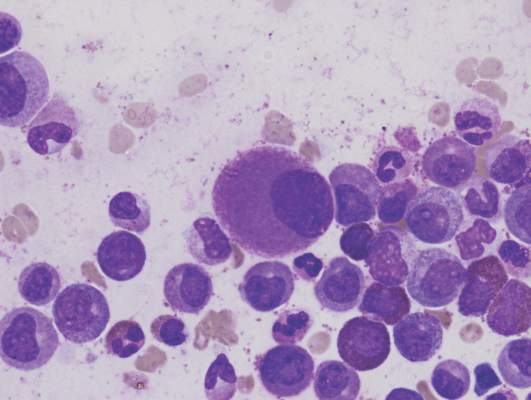

Team describes method of targeting LSCs in BC-CML

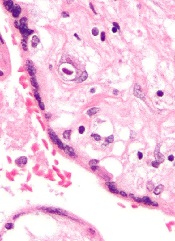

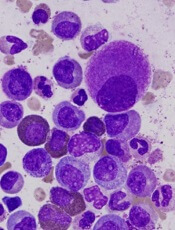

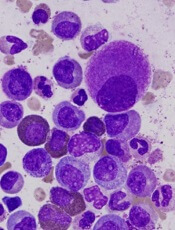

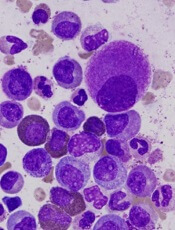

Photo courtesy of

UC San Diego Health

New research has revealed a method of targeting leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (BC-CML).

For this study, investigators used human cells and mouse models to define the role of ADAR1, an RNA editing enzyme, in BC-CML.

The team discovered how ADAR1 promotes LSC generation and identified a small molecule that can disrupt this process to fight BC-CML.

Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues described this work in Cell Stem Cell.

“In this study, we showed that cancer stem cells co-opt an RNA editing system to clone themselves,” Dr Jamieson said. “What’s more, we found a method to dial it down.”

The investigators knew that ADAR1 can edit the sequence of microRNAs. By swapping out just one microRNA building block for another, ADAR1 alters the carefully orchestrated system cells use to control which genes are turned on or off at which times.

ADAR1 is also known to promote cancer progression and resistance to therapy. But Dr Jamieson’s team wanted to determine ADAR1’s role in governing LSCs.

The investigators conducted experiments with human BC-CML cells and mouse models of BC-CML. And they found that increased JAK2 signaling and BCR-ABL1 amplification activate ADAR1 in BC-CML cells. Then, hyper-ADAR1 editing slows down microRNAs known as let-7.

Ultimately, this activity increases cellular regeneration, turning white blood cell precursors into LSCs. And LSCs promote BC-CML.

After learning how the ADAR1 system works, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues looked for a way to stop it.

By inhibiting ADAR1 with a small-molecule compound known as 8-Aza, the investigators were able to counter ADAR1’s effect on LSC self-renewal and restore let-7.

Treatment with 8-Aza reduced self-renewal of BC-CML cells by approximately 40%, when compared to untreated cells.

“Based on this research, we believe that detecting ADAR1 activity will be important for predicting cancer progression,” Dr Jamieson said.

“In addition, inhibiting this enzyme represents a unique therapeutic vulnerability in cancer stem cells with active inflammatory signaling that may respond to pharmacologic inhibitors of inflammation sensitivity or selective ADAR1 inhibitors that are currently being developed.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of

UC San Diego Health

New research has revealed a method of targeting leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (BC-CML).

For this study, investigators used human cells and mouse models to define the role of ADAR1, an RNA editing enzyme, in BC-CML.

The team discovered how ADAR1 promotes LSC generation and identified a small molecule that can disrupt this process to fight BC-CML.

Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues described this work in Cell Stem Cell.

“In this study, we showed that cancer stem cells co-opt an RNA editing system to clone themselves,” Dr Jamieson said. “What’s more, we found a method to dial it down.”

The investigators knew that ADAR1 can edit the sequence of microRNAs. By swapping out just one microRNA building block for another, ADAR1 alters the carefully orchestrated system cells use to control which genes are turned on or off at which times.

ADAR1 is also known to promote cancer progression and resistance to therapy. But Dr Jamieson’s team wanted to determine ADAR1’s role in governing LSCs.

The investigators conducted experiments with human BC-CML cells and mouse models of BC-CML. And they found that increased JAK2 signaling and BCR-ABL1 amplification activate ADAR1 in BC-CML cells. Then, hyper-ADAR1 editing slows down microRNAs known as let-7.

Ultimately, this activity increases cellular regeneration, turning white blood cell precursors into LSCs. And LSCs promote BC-CML.

After learning how the ADAR1 system works, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues looked for a way to stop it.

By inhibiting ADAR1 with a small-molecule compound known as 8-Aza, the investigators were able to counter ADAR1’s effect on LSC self-renewal and restore let-7.

Treatment with 8-Aza reduced self-renewal of BC-CML cells by approximately 40%, when compared to untreated cells.

“Based on this research, we believe that detecting ADAR1 activity will be important for predicting cancer progression,” Dr Jamieson said.

“In addition, inhibiting this enzyme represents a unique therapeutic vulnerability in cancer stem cells with active inflammatory signaling that may respond to pharmacologic inhibitors of inflammation sensitivity or selective ADAR1 inhibitors that are currently being developed.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of

UC San Diego Health

New research has revealed a method of targeting leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia (BC-CML).

For this study, investigators used human cells and mouse models to define the role of ADAR1, an RNA editing enzyme, in BC-CML.

The team discovered how ADAR1 promotes LSC generation and identified a small molecule that can disrupt this process to fight BC-CML.

Catriona Jamieson, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues described this work in Cell Stem Cell.

“In this study, we showed that cancer stem cells co-opt an RNA editing system to clone themselves,” Dr Jamieson said. “What’s more, we found a method to dial it down.”

The investigators knew that ADAR1 can edit the sequence of microRNAs. By swapping out just one microRNA building block for another, ADAR1 alters the carefully orchestrated system cells use to control which genes are turned on or off at which times.

ADAR1 is also known to promote cancer progression and resistance to therapy. But Dr Jamieson’s team wanted to determine ADAR1’s role in governing LSCs.

The investigators conducted experiments with human BC-CML cells and mouse models of BC-CML. And they found that increased JAK2 signaling and BCR-ABL1 amplification activate ADAR1 in BC-CML cells. Then, hyper-ADAR1 editing slows down microRNAs known as let-7.

Ultimately, this activity increases cellular regeneration, turning white blood cell precursors into LSCs. And LSCs promote BC-CML.

After learning how the ADAR1 system works, Dr Jamieson and her colleagues looked for a way to stop it.

By inhibiting ADAR1 with a small-molecule compound known as 8-Aza, the investigators were able to counter ADAR1’s effect on LSC self-renewal and restore let-7.

Treatment with 8-Aza reduced self-renewal of BC-CML cells by approximately 40%, when compared to untreated cells.

“Based on this research, we believe that detecting ADAR1 activity will be important for predicting cancer progression,” Dr Jamieson said.

“In addition, inhibiting this enzyme represents a unique therapeutic vulnerability in cancer stem cells with active inflammatory signaling that may respond to pharmacologic inhibitors of inflammation sensitivity or selective ADAR1 inhibitors that are currently being developed.” ![]()

Stopping TKI therapy can be safe, study suggests

COPENHAGEN—Results of a large study suggest that stopping treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can be safe for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in deep molecular response (MR4).

Six months after patients stopped receiving a TKI, the relapse-free survival was 62%. At 12 months, it was 56%.

Havinga longer duration of TKI treatment and a longer duration of deep molecular response were both associated with a higher likelihood of relapse-free survival.

These results, from the EURO-SKI trial, were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S145*) by Johan Richter, MD, PhD, of Skåne University Hospital in Lund, Sweden.

The goal of the EURO-SKI study was to define prognostic markers to increase the proportion of patients in durable deep molecular response after stopping TKI treatment.

The trial included 760 adults with chronic phase CML who were on TKI treatment for at least 3 years. Patients were either on their first TKI or on their second TKI due to toxicity with their first. (None had failed TKI treatment.)

Patients had been in MR4 (BCR/ABL <0.01%) for at least a year, which was confirmed by 3 consecutive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results during the last 12 months. The final MR4 confirmation was performed in a EUTOS standardized laboratory.

After the final MR4 confirmation, patients stopped TKI treatment. They underwent real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) every 4 weeks for the first 6 months and every 6 weeks for the next 6 months. In years 2 and 3, they underwent RQ-PCR every third month.

The patients had a median age at diagnosis of 52 (range, 11.2-85.5) and a median age at TKI stop of 60.3 (range, 19.5-89.9). The median duration of TKI therapy was 7.6 years (range, 3.0-14.2), and the median duration of MR4 before TKI stop was 4.7 years (range, 1.0-13.3).

Most patients had received imatinib (n=710) as first-line TKI treatment, though some received nilotinib (n=35) or dasatinib (n=14). The type of first-line TKI was unknown in 1 patient. Second-line TKI treatment included imatinib (n=7), nilotinib (n=47), and dasatinib (n=57).

Relapse, survival, and safety

Six months after stopping TKI treatment, the cumulative incidence of molecular relapse was 37%. It was 43% at 12 months, 47% at 24 months, and 50% at 36 months.

In all, 347 patients had a molecular relapse. Seventy-two patients had BCR/ABL >1%, and 11 lost their complete cytogenetic response. None of the patients progressed to accelerated phase or blast crisis.

Among patients who restarted TKI treatment, the median time to restart was 4.1 months. Fourteen patients restarted treatment without a loss of major molecular response.

Dr Richter noted that the study is still ongoing, but, thus far, more than 80% of patients who restarted TKI therapy have achieved MR4 again.

The molecular relapse-free survival was 62% at 6 months after TKI stop, 56% at 12 months, 52% at 24 months, and 49% at 36 months.

There were 9 on-trial deaths, none of which were related to CML. Five patients died while in remission.

Previous studies revealed a TKI withdrawal syndrome that consists of (mostly transient) musculoskeletal pain or discomfort. In this study, 30.9% of patients (n=235) reported musculoskeletal symptoms, 226 with grade 1-2 events and 9 with grade 3 events.

Prognostic factors

The researchers performed prognostic modeling in 448 patients who previously received imatinib. Univariate analysis revealed no significant association between molecular relapse-free survival at 6 months and age, gender, depth of molecular response, Sokal score, EURO score, EUTOS score, or ELTS score.

However, TKI treatment duration and MR4 duration were both significantly (P<0.001) associated with major molecular response status at 6 months.

The odds ratio for treatment duration was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.08-1.25), which means that an additional year of imatinib treatment increases a patient’s odds of staying in major molecular response at 6 months by 16%.

The odds ratio for MR4 duration was also 1.16 (95% CI, 1.076-1.253), which means that an additional year in MR4 before TKI stop increases a patient’s odds of staying in major molecular response at 6 months by 16%.

Dr Richter noted that treatment duration and MR4 duration were highly correlated, which prevented a significant multiple model including both variables. He said the researchers will conduct further analyses to overcome the correlation between the 2 variables and determine an optimal cutoff for MR4 duration.

The team also plans to collect more data on pretreatment with interferon, as there is reason to suspect it has an influence on major molecular response duration after TKI discontinuation. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

COPENHAGEN—Results of a large study suggest that stopping treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can be safe for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in deep molecular response (MR4).

Six months after patients stopped receiving a TKI, the relapse-free survival was 62%. At 12 months, it was 56%.

Havinga longer duration of TKI treatment and a longer duration of deep molecular response were both associated with a higher likelihood of relapse-free survival.

These results, from the EURO-SKI trial, were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S145*) by Johan Richter, MD, PhD, of Skåne University Hospital in Lund, Sweden.

The goal of the EURO-SKI study was to define prognostic markers to increase the proportion of patients in durable deep molecular response after stopping TKI treatment.

The trial included 760 adults with chronic phase CML who were on TKI treatment for at least 3 years. Patients were either on their first TKI or on their second TKI due to toxicity with their first. (None had failed TKI treatment.)

Patients had been in MR4 (BCR/ABL <0.01%) for at least a year, which was confirmed by 3 consecutive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results during the last 12 months. The final MR4 confirmation was performed in a EUTOS standardized laboratory.

After the final MR4 confirmation, patients stopped TKI treatment. They underwent real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) every 4 weeks for the first 6 months and every 6 weeks for the next 6 months. In years 2 and 3, they underwent RQ-PCR every third month.

The patients had a median age at diagnosis of 52 (range, 11.2-85.5) and a median age at TKI stop of 60.3 (range, 19.5-89.9). The median duration of TKI therapy was 7.6 years (range, 3.0-14.2), and the median duration of MR4 before TKI stop was 4.7 years (range, 1.0-13.3).

Most patients had received imatinib (n=710) as first-line TKI treatment, though some received nilotinib (n=35) or dasatinib (n=14). The type of first-line TKI was unknown in 1 patient. Second-line TKI treatment included imatinib (n=7), nilotinib (n=47), and dasatinib (n=57).

Relapse, survival, and safety

Six months after stopping TKI treatment, the cumulative incidence of molecular relapse was 37%. It was 43% at 12 months, 47% at 24 months, and 50% at 36 months.

In all, 347 patients had a molecular relapse. Seventy-two patients had BCR/ABL >1%, and 11 lost their complete cytogenetic response. None of the patients progressed to accelerated phase or blast crisis.

Among patients who restarted TKI treatment, the median time to restart was 4.1 months. Fourteen patients restarted treatment without a loss of major molecular response.

Dr Richter noted that the study is still ongoing, but, thus far, more than 80% of patients who restarted TKI therapy have achieved MR4 again.

The molecular relapse-free survival was 62% at 6 months after TKI stop, 56% at 12 months, 52% at 24 months, and 49% at 36 months.

There were 9 on-trial deaths, none of which were related to CML. Five patients died while in remission.

Previous studies revealed a TKI withdrawal syndrome that consists of (mostly transient) musculoskeletal pain or discomfort. In this study, 30.9% of patients (n=235) reported musculoskeletal symptoms, 226 with grade 1-2 events and 9 with grade 3 events.

Prognostic factors

The researchers performed prognostic modeling in 448 patients who previously received imatinib. Univariate analysis revealed no significant association between molecular relapse-free survival at 6 months and age, gender, depth of molecular response, Sokal score, EURO score, EUTOS score, or ELTS score.

However, TKI treatment duration and MR4 duration were both significantly (P<0.001) associated with major molecular response status at 6 months.

The odds ratio for treatment duration was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.08-1.25), which means that an additional year of imatinib treatment increases a patient’s odds of staying in major molecular response at 6 months by 16%.

The odds ratio for MR4 duration was also 1.16 (95% CI, 1.076-1.253), which means that an additional year in MR4 before TKI stop increases a patient’s odds of staying in major molecular response at 6 months by 16%.

Dr Richter noted that treatment duration and MR4 duration were highly correlated, which prevented a significant multiple model including both variables. He said the researchers will conduct further analyses to overcome the correlation between the 2 variables and determine an optimal cutoff for MR4 duration.

The team also plans to collect more data on pretreatment with interferon, as there is reason to suspect it has an influence on major molecular response duration after TKI discontinuation. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

COPENHAGEN—Results of a large study suggest that stopping treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can be safe for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in deep molecular response (MR4).

Six months after patients stopped receiving a TKI, the relapse-free survival was 62%. At 12 months, it was 56%.

Havinga longer duration of TKI treatment and a longer duration of deep molecular response were both associated with a higher likelihood of relapse-free survival.

These results, from the EURO-SKI trial, were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract S145*) by Johan Richter, MD, PhD, of Skåne University Hospital in Lund, Sweden.

The goal of the EURO-SKI study was to define prognostic markers to increase the proportion of patients in durable deep molecular response after stopping TKI treatment.

The trial included 760 adults with chronic phase CML who were on TKI treatment for at least 3 years. Patients were either on their first TKI or on their second TKI due to toxicity with their first. (None had failed TKI treatment.)

Patients had been in MR4 (BCR/ABL <0.01%) for at least a year, which was confirmed by 3 consecutive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results during the last 12 months. The final MR4 confirmation was performed in a EUTOS standardized laboratory.

After the final MR4 confirmation, patients stopped TKI treatment. They underwent real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) every 4 weeks for the first 6 months and every 6 weeks for the next 6 months. In years 2 and 3, they underwent RQ-PCR every third month.

The patients had a median age at diagnosis of 52 (range, 11.2-85.5) and a median age at TKI stop of 60.3 (range, 19.5-89.9). The median duration of TKI therapy was 7.6 years (range, 3.0-14.2), and the median duration of MR4 before TKI stop was 4.7 years (range, 1.0-13.3).

Most patients had received imatinib (n=710) as first-line TKI treatment, though some received nilotinib (n=35) or dasatinib (n=14). The type of first-line TKI was unknown in 1 patient. Second-line TKI treatment included imatinib (n=7), nilotinib (n=47), and dasatinib (n=57).

Relapse, survival, and safety

Six months after stopping TKI treatment, the cumulative incidence of molecular relapse was 37%. It was 43% at 12 months, 47% at 24 months, and 50% at 36 months.

In all, 347 patients had a molecular relapse. Seventy-two patients had BCR/ABL >1%, and 11 lost their complete cytogenetic response. None of the patients progressed to accelerated phase or blast crisis.

Among patients who restarted TKI treatment, the median time to restart was 4.1 months. Fourteen patients restarted treatment without a loss of major molecular response.

Dr Richter noted that the study is still ongoing, but, thus far, more than 80% of patients who restarted TKI therapy have achieved MR4 again.

The molecular relapse-free survival was 62% at 6 months after TKI stop, 56% at 12 months, 52% at 24 months, and 49% at 36 months.

There were 9 on-trial deaths, none of which were related to CML. Five patients died while in remission.

Previous studies revealed a TKI withdrawal syndrome that consists of (mostly transient) musculoskeletal pain or discomfort. In this study, 30.9% of patients (n=235) reported musculoskeletal symptoms, 226 with grade 1-2 events and 9 with grade 3 events.

Prognostic factors

The researchers performed prognostic modeling in 448 patients who previously received imatinib. Univariate analysis revealed no significant association between molecular relapse-free survival at 6 months and age, gender, depth of molecular response, Sokal score, EURO score, EUTOS score, or ELTS score.

However, TKI treatment duration and MR4 duration were both significantly (P<0.001) associated with major molecular response status at 6 months.

The odds ratio for treatment duration was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.08-1.25), which means that an additional year of imatinib treatment increases a patient’s odds of staying in major molecular response at 6 months by 16%.

The odds ratio for MR4 duration was also 1.16 (95% CI, 1.076-1.253), which means that an additional year in MR4 before TKI stop increases a patient’s odds of staying in major molecular response at 6 months by 16%.

Dr Richter noted that treatment duration and MR4 duration were highly correlated, which prevented a significant multiple model including both variables. He said the researchers will conduct further analyses to overcome the correlation between the 2 variables and determine an optimal cutoff for MR4 duration.

The team also plans to collect more data on pretreatment with interferon, as there is reason to suspect it has an influence on major molecular response duration after TKI discontinuation. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data presented at the meeting.

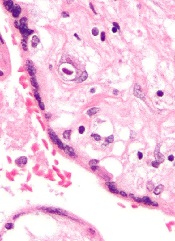

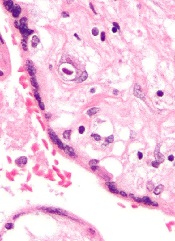

How CML cells respond to stress

Image by Difu Wu

Researchers have used a tiny force probe to compare how healthy hematopoietic cells and cancerous ones respond to stress.

They found that cells harvested from the bone marrow of 5 patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) appeared much stiffer than comparable samples taken from 5 healthy volunteers.

In addition, the researchers were able to identify areas of localized brittle failure events in the CML cells.

“What makes this work so exciting to us is not simply seeing a difference between the stiffness of healthy and cancerous cells but observing that the cancerous cells also lost their dynamic ductility and behaved as more breakable objects,” said study author Françoise Argoul, PhD, of the French National Centre for Research (CNRS) in Lyon, France.

Dr Argoul and her colleagues described this work in Physical Biology.

The researchers believe the mechanical signatures obtained by squeezing or deforming cells could potentially assist physicians in determining the presence of CML and other hematologic malignancies.

The mechanical data might also provide clues as to how long the cells have been affected by the cancer.

“We would like to construct a hematopoietic cancer cell chart where the loss of cell mechanical functions could be graded, depending on the leukemia and its stage of evolution,” Dr Argoul said.

Thinking about how the technique might be applied in a hospital setting, she added that biopsy needles could, in principle, be adapted to allow local sensing of internal soft tissue structures.

However, before the researchers can even progress to testing cells inside the body and preparing for clinical trials, they must first build up sufficient information from their measurements on isolated cells under a range of conditions in the lab. ![]()

Image by Difu Wu

Researchers have used a tiny force probe to compare how healthy hematopoietic cells and cancerous ones respond to stress.

They found that cells harvested from the bone marrow of 5 patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) appeared much stiffer than comparable samples taken from 5 healthy volunteers.

In addition, the researchers were able to identify areas of localized brittle failure events in the CML cells.

“What makes this work so exciting to us is not simply seeing a difference between the stiffness of healthy and cancerous cells but observing that the cancerous cells also lost their dynamic ductility and behaved as more breakable objects,” said study author Françoise Argoul, PhD, of the French National Centre for Research (CNRS) in Lyon, France.

Dr Argoul and her colleagues described this work in Physical Biology.

The researchers believe the mechanical signatures obtained by squeezing or deforming cells could potentially assist physicians in determining the presence of CML and other hematologic malignancies.

The mechanical data might also provide clues as to how long the cells have been affected by the cancer.

“We would like to construct a hematopoietic cancer cell chart where the loss of cell mechanical functions could be graded, depending on the leukemia and its stage of evolution,” Dr Argoul said.

Thinking about how the technique might be applied in a hospital setting, she added that biopsy needles could, in principle, be adapted to allow local sensing of internal soft tissue structures.

However, before the researchers can even progress to testing cells inside the body and preparing for clinical trials, they must first build up sufficient information from their measurements on isolated cells under a range of conditions in the lab. ![]()

Image by Difu Wu

Researchers have used a tiny force probe to compare how healthy hematopoietic cells and cancerous ones respond to stress.

They found that cells harvested from the bone marrow of 5 patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) appeared much stiffer than comparable samples taken from 5 healthy volunteers.

In addition, the researchers were able to identify areas of localized brittle failure events in the CML cells.

“What makes this work so exciting to us is not simply seeing a difference between the stiffness of healthy and cancerous cells but observing that the cancerous cells also lost their dynamic ductility and behaved as more breakable objects,” said study author Françoise Argoul, PhD, of the French National Centre for Research (CNRS) in Lyon, France.

Dr Argoul and her colleagues described this work in Physical Biology.

The researchers believe the mechanical signatures obtained by squeezing or deforming cells could potentially assist physicians in determining the presence of CML and other hematologic malignancies.

The mechanical data might also provide clues as to how long the cells have been affected by the cancer.

“We would like to construct a hematopoietic cancer cell chart where the loss of cell mechanical functions could be graded, depending on the leukemia and its stage of evolution,” Dr Argoul said.

Thinking about how the technique might be applied in a hospital setting, she added that biopsy needles could, in principle, be adapted to allow local sensing of internal soft tissue structures.

However, before the researchers can even progress to testing cells inside the body and preparing for clinical trials, they must first build up sufficient information from their measurements on isolated cells under a range of conditions in the lab. ![]()

Hold that TKI – When it’s safe to stop in CML

COPENHAGEN – A year after stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, more than half of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in a large clinical trial remained in deep molecular remission.

Among 750 patients with CML in remission for at least 1 year before study entry, 62% retained a treatment response 6 months after stopping a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) such as imatinib (Gleevec) and 56% retained responses 1 year after being off their drugs, reported Dr. Johan Richter of Lund (Sweden) University at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

“About 6 years of therapy [with imatinib] would be optimal for therapy prior to a stop attempt,” he said at a briefing prior to the presentation of data at the congress.

Although in clinical practice patients with CML may remain on a TKI indefinitely, results from small clinical trials have suggested that in 40%-60% of patients with deep molecular responses (MR4.0 or better), TKIs can be safely stopped, Dr. Richter noted.

To get a better handle on when it might be safe to stop a TKI and under what conditions, EURO-SKI investigators enrolled 868 adults with CML in chronic phase from 11 countries, 750 of whom had complete data for the analysis.

In all, 94% of patients had received imatinib in the first line, 2% received dasatinib (Sprycel), and 4% had received nilotinib (Tasigna). Of this group, 115 had switched to a second-line agent due to intolerance of the first-line drug.

The median time from diagnosis was 7.7 years. The median duration of therapy was 7.6 years, and the median duration of MR4 before stopping was 4.7 years.

As noted, among 750 patients assessable for molecular relapse–free survival, 62% remained in remission at 6 months after stopping the TKI, as did 56% at 12 months, 52% at 24 months, and 49% at 36 months.

For patients who resumed therapy, the median time to restart was 4.1 months.

To see whether they could identify any factors prognostic for relapse after stopping a TKI, the investigators used data on 448 patients in the study who were treated with imatinib.

In univariate analysis there was no significant association between molecular relapse–free survival at 6 months and either age, gender, depth of molecular response, or any standard risk scores.

The only significant predictors of molecular remission status at 6 months were duration of imatinib therapy and duration of molecular response before stopping.

The odds ratio for treatment duration was 1.16, indicating that each additional year of imatinib treatment is associated with a 16% increase in the likelihood that a patient would remain in deep molecular remission 6 months after stopping.

The investigators used the minimal P value approach to determine the cutoff of approximately 6 years, based on a molecular relapse–free survival at 6 months of 65.5% for patients who remained on imatinib for more than 5.8 years, compared with 42.6% for those who were on it for 5.8 years or less.

Although the study is ongoing, to date more than 80% of patients who had a loss of deep molecular remission after stopping their TKI regained the remission after resuming therapy, Dr. Richter said.

Dr. Richter said in an interview that longer follow-up will be needed to confirm their findings, and that patients who were sensitive to TKIs prior to stopping therapy remained sensitive when restarting, suggesting that treatment interruption does not increase the likelihood of drug resistance.

Coprincipal investigator Dr. Francois-Xavier Mahon of Bordeaux University in France, noted that in the STIM (Stop Imatinib)–1 and –2 trials, the estimated annual savings to the French health care system were 20 million euros ($22.6 million).

COPENHAGEN – A year after stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, more than half of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in a large clinical trial remained in deep molecular remission.

Among 750 patients with CML in remission for at least 1 year before study entry, 62% retained a treatment response 6 months after stopping a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) such as imatinib (Gleevec) and 56% retained responses 1 year after being off their drugs, reported Dr. Johan Richter of Lund (Sweden) University at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

“About 6 years of therapy [with imatinib] would be optimal for therapy prior to a stop attempt,” he said at a briefing prior to the presentation of data at the congress.

Although in clinical practice patients with CML may remain on a TKI indefinitely, results from small clinical trials have suggested that in 40%-60% of patients with deep molecular responses (MR4.0 or better), TKIs can be safely stopped, Dr. Richter noted.

To get a better handle on when it might be safe to stop a TKI and under what conditions, EURO-SKI investigators enrolled 868 adults with CML in chronic phase from 11 countries, 750 of whom had complete data for the analysis.

In all, 94% of patients had received imatinib in the first line, 2% received dasatinib (Sprycel), and 4% had received nilotinib (Tasigna). Of this group, 115 had switched to a second-line agent due to intolerance of the first-line drug.

The median time from diagnosis was 7.7 years. The median duration of therapy was 7.6 years, and the median duration of MR4 before stopping was 4.7 years.

As noted, among 750 patients assessable for molecular relapse–free survival, 62% remained in remission at 6 months after stopping the TKI, as did 56% at 12 months, 52% at 24 months, and 49% at 36 months.

For patients who resumed therapy, the median time to restart was 4.1 months.

To see whether they could identify any factors prognostic for relapse after stopping a TKI, the investigators used data on 448 patients in the study who were treated with imatinib.

In univariate analysis there was no significant association between molecular relapse–free survival at 6 months and either age, gender, depth of molecular response, or any standard risk scores.

The only significant predictors of molecular remission status at 6 months were duration of imatinib therapy and duration of molecular response before stopping.

The odds ratio for treatment duration was 1.16, indicating that each additional year of imatinib treatment is associated with a 16% increase in the likelihood that a patient would remain in deep molecular remission 6 months after stopping.

The investigators used the minimal P value approach to determine the cutoff of approximately 6 years, based on a molecular relapse–free survival at 6 months of 65.5% for patients who remained on imatinib for more than 5.8 years, compared with 42.6% for those who were on it for 5.8 years or less.

Although the study is ongoing, to date more than 80% of patients who had a loss of deep molecular remission after stopping their TKI regained the remission after resuming therapy, Dr. Richter said.

Dr. Richter said in an interview that longer follow-up will be needed to confirm their findings, and that patients who were sensitive to TKIs prior to stopping therapy remained sensitive when restarting, suggesting that treatment interruption does not increase the likelihood of drug resistance.

Coprincipal investigator Dr. Francois-Xavier Mahon of Bordeaux University in France, noted that in the STIM (Stop Imatinib)–1 and –2 trials, the estimated annual savings to the French health care system were 20 million euros ($22.6 million).

COPENHAGEN – A year after stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, more than half of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in a large clinical trial remained in deep molecular remission.

Among 750 patients with CML in remission for at least 1 year before study entry, 62% retained a treatment response 6 months after stopping a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) such as imatinib (Gleevec) and 56% retained responses 1 year after being off their drugs, reported Dr. Johan Richter of Lund (Sweden) University at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

“About 6 years of therapy [with imatinib] would be optimal for therapy prior to a stop attempt,” he said at a briefing prior to the presentation of data at the congress.

Although in clinical practice patients with CML may remain on a TKI indefinitely, results from small clinical trials have suggested that in 40%-60% of patients with deep molecular responses (MR4.0 or better), TKIs can be safely stopped, Dr. Richter noted.

To get a better handle on when it might be safe to stop a TKI and under what conditions, EURO-SKI investigators enrolled 868 adults with CML in chronic phase from 11 countries, 750 of whom had complete data for the analysis.

In all, 94% of patients had received imatinib in the first line, 2% received dasatinib (Sprycel), and 4% had received nilotinib (Tasigna). Of this group, 115 had switched to a second-line agent due to intolerance of the first-line drug.

The median time from diagnosis was 7.7 years. The median duration of therapy was 7.6 years, and the median duration of MR4 before stopping was 4.7 years.

As noted, among 750 patients assessable for molecular relapse–free survival, 62% remained in remission at 6 months after stopping the TKI, as did 56% at 12 months, 52% at 24 months, and 49% at 36 months.

For patients who resumed therapy, the median time to restart was 4.1 months.

To see whether they could identify any factors prognostic for relapse after stopping a TKI, the investigators used data on 448 patients in the study who were treated with imatinib.

In univariate analysis there was no significant association between molecular relapse–free survival at 6 months and either age, gender, depth of molecular response, or any standard risk scores.

The only significant predictors of molecular remission status at 6 months were duration of imatinib therapy and duration of molecular response before stopping.

The odds ratio for treatment duration was 1.16, indicating that each additional year of imatinib treatment is associated with a 16% increase in the likelihood that a patient would remain in deep molecular remission 6 months after stopping.

The investigators used the minimal P value approach to determine the cutoff of approximately 6 years, based on a molecular relapse–free survival at 6 months of 65.5% for patients who remained on imatinib for more than 5.8 years, compared with 42.6% for those who were on it for 5.8 years or less.

Although the study is ongoing, to date more than 80% of patients who had a loss of deep molecular remission after stopping their TKI regained the remission after resuming therapy, Dr. Richter said.

Dr. Richter said in an interview that longer follow-up will be needed to confirm their findings, and that patients who were sensitive to TKIs prior to stopping therapy remained sensitive when restarting, suggesting that treatment interruption does not increase the likelihood of drug resistance.

Coprincipal investigator Dr. Francois-Xavier Mahon of Bordeaux University in France, noted that in the STIM (Stop Imatinib)–1 and –2 trials, the estimated annual savings to the French health care system were 20 million euros ($22.6 million).

AT THE EHA CONGRESS

Key clinical point:.Tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy can be safely stopped and resumed in many patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Major finding: After stopping a TKI, 62% of patients retained a treatment response at 6 months, and 56% retained a response at 1 year.

Data source: Study of therapeutic interruption in 750 adults in deep molecular remission for at least 1 year on TKI therapy.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the European LeukemiaNet. Dr. Richter has previously disclosed consultancy and equity ownership with Cantargia. Dr. Mahon has previously disclosed being on the scientific advisory board and receiving honoraria from Novartis Oncology and BMS, and serving as consultant to those companies and to Pfizer.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors may boost cardiac risk in chronic myeloid leukemia

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who received tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) had 1.7 times the rate of arterial or venous vascular events of population-based controls in a large retrospective cohort study.

In addition, second-generation TKIs were associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction than was first-generation imatinib, Dr. Torsten Dahlén of Karolinska University Hospital Solna, Stockholm, and his associates reported. Although absolute numbers of cardiovascular events were low, physicians “should be aware of these risk factors when initiating TKI therapy in patients with CML,” the authors wrote in a study published online June 13 in the Annals of Internal Medicine .

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have “revolutionized” the prognosis of CML and are generally well tolerated, the researchers noted. But case reports and follow-up studies of clinical trial participants have raised concerns about cardiovascular toxicities with second-generation TKIs, such as nilotinib, they added.

To further study the issue, the investigators compared 896 patients in Sweden who were diagnosed with CML between 2002 and 2012 with 4,438 age- and sex-matched controls from the national population register. By crosschecking both groups against a national patient database, the investigators calculated rates of venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular ischemia, and other arterial thromboses (Ann. Intern. Med. 2016 Jun 13. doi: 10.7326/M15-2306).

A total of 846 CML patients (94%) received a TKI during a median of 4.2 years of follow-up, the investigators reported. First-line therapy usually consisted of imatinib (89%), followed by nilotinib (9%) and dasatinib (1%).

The TKI cohort had 78 arterial and venous events during 3,969 person-years of follow-up, compared with 250 events during 21,917 person-years of follow-up for controls, for a statistically significant incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.2). Individual IRRs for arterial and venous events also reached statistical significance at 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1-2.1) and 2.0 (95% CI, 1.2-3.3), respectively. Deep venous thrombosis and myocardial infarction accounted for most of the excess risk, with IRRs of 2.2 (95% CI, 1.1-4.4) and 1.9 (95% CI, 1.3-2.7), respectively.

When investigators looked only at the TKI cohort, they found that the rates of arterial thromboembolic events were highest for nilotinib (29 events per 1,000 person-years), followed by dasatinib (19 events per 1,000 person-years) and imatinib (13 events per 1,000 person-years). Nilotinib also was associated with a substantially higher rate of all arterial and venous events (42/1,000 person-years) than dasatinib (20/1,000 person-years) and imatinib (16/1,000 person-years).

Furthermore, nilotinib and dasatinib were associated with higher rates of myocardial infarctions (29 and 19 per 1,000 person-years, respectively) and cerebrovascular ischemic events (11 and 4 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively) than was imatinib (8 events per 1,000 person-years and 4 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively). However, the absolute numbers of events were too small to allow for statistical comparisons, the researchers said.

“The observed increase in thrombotic events may be related to CML itself, the treatment administered, or both,” they noted, but “the prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with CML before diagnosis was similar to that of the control population, [which] might indicate a treatment-related association.”

Among the 31 patients on TKIs who had a myocardial infarction, 26 (84%) had been previously diagnosed with at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease, including diabetes (19%), atrial fibrillation (26%), angina pectoris (39%), hypertension (55%), and hyperlipidemia (23%).

Most patients who received nilotinib or dasatinib had previously received imatinib, meaning that they could have had more advanced disease that increased their risk of adverse events, according to the researchers.

“The small number of events also leads us to exercise caution in drawing any strong conclusions,” they added. “Future data from the Swedish CML register will provide more robust evidence regarding the risks of individual drugs as exposure time increases.”

The researchers received no funding for the work. Dr. Dahlén disclosed grant support from Merck outside the submitted work. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Ariad, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, and Squibb.

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who received tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) had 1.7 times the rate of arterial or venous vascular events of population-based controls in a large retrospective cohort study.

In addition, second-generation TKIs were associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction than was first-generation imatinib, Dr. Torsten Dahlén of Karolinska University Hospital Solna, Stockholm, and his associates reported. Although absolute numbers of cardiovascular events were low, physicians “should be aware of these risk factors when initiating TKI therapy in patients with CML,” the authors wrote in a study published online June 13 in the Annals of Internal Medicine .

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have “revolutionized” the prognosis of CML and are generally well tolerated, the researchers noted. But case reports and follow-up studies of clinical trial participants have raised concerns about cardiovascular toxicities with second-generation TKIs, such as nilotinib, they added.

To further study the issue, the investigators compared 896 patients in Sweden who were diagnosed with CML between 2002 and 2012 with 4,438 age- and sex-matched controls from the national population register. By crosschecking both groups against a national patient database, the investigators calculated rates of venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular ischemia, and other arterial thromboses (Ann. Intern. Med. 2016 Jun 13. doi: 10.7326/M15-2306).

A total of 846 CML patients (94%) received a TKI during a median of 4.2 years of follow-up, the investigators reported. First-line therapy usually consisted of imatinib (89%), followed by nilotinib (9%) and dasatinib (1%).

The TKI cohort had 78 arterial and venous events during 3,969 person-years of follow-up, compared with 250 events during 21,917 person-years of follow-up for controls, for a statistically significant incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.2). Individual IRRs for arterial and venous events also reached statistical significance at 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1-2.1) and 2.0 (95% CI, 1.2-3.3), respectively. Deep venous thrombosis and myocardial infarction accounted for most of the excess risk, with IRRs of 2.2 (95% CI, 1.1-4.4) and 1.9 (95% CI, 1.3-2.7), respectively.

When investigators looked only at the TKI cohort, they found that the rates of arterial thromboembolic events were highest for nilotinib (29 events per 1,000 person-years), followed by dasatinib (19 events per 1,000 person-years) and imatinib (13 events per 1,000 person-years). Nilotinib also was associated with a substantially higher rate of all arterial and venous events (42/1,000 person-years) than dasatinib (20/1,000 person-years) and imatinib (16/1,000 person-years).

Furthermore, nilotinib and dasatinib were associated with higher rates of myocardial infarctions (29 and 19 per 1,000 person-years, respectively) and cerebrovascular ischemic events (11 and 4 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively) than was imatinib (8 events per 1,000 person-years and 4 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively). However, the absolute numbers of events were too small to allow for statistical comparisons, the researchers said.

“The observed increase in thrombotic events may be related to CML itself, the treatment administered, or both,” they noted, but “the prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with CML before diagnosis was similar to that of the control population, [which] might indicate a treatment-related association.”

Among the 31 patients on TKIs who had a myocardial infarction, 26 (84%) had been previously diagnosed with at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease, including diabetes (19%), atrial fibrillation (26%), angina pectoris (39%), hypertension (55%), and hyperlipidemia (23%).

Most patients who received nilotinib or dasatinib had previously received imatinib, meaning that they could have had more advanced disease that increased their risk of adverse events, according to the researchers.

“The small number of events also leads us to exercise caution in drawing any strong conclusions,” they added. “Future data from the Swedish CML register will provide more robust evidence regarding the risks of individual drugs as exposure time increases.”

The researchers received no funding for the work. Dr. Dahlén disclosed grant support from Merck outside the submitted work. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Ariad, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, and Squibb.

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who received tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) had 1.7 times the rate of arterial or venous vascular events of population-based controls in a large retrospective cohort study.

In addition, second-generation TKIs were associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction than was first-generation imatinib, Dr. Torsten Dahlén of Karolinska University Hospital Solna, Stockholm, and his associates reported. Although absolute numbers of cardiovascular events were low, physicians “should be aware of these risk factors when initiating TKI therapy in patients with CML,” the authors wrote in a study published online June 13 in the Annals of Internal Medicine .

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have “revolutionized” the prognosis of CML and are generally well tolerated, the researchers noted. But case reports and follow-up studies of clinical trial participants have raised concerns about cardiovascular toxicities with second-generation TKIs, such as nilotinib, they added.

To further study the issue, the investigators compared 896 patients in Sweden who were diagnosed with CML between 2002 and 2012 with 4,438 age- and sex-matched controls from the national population register. By crosschecking both groups against a national patient database, the investigators calculated rates of venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular ischemia, and other arterial thromboses (Ann. Intern. Med. 2016 Jun 13. doi: 10.7326/M15-2306).

A total of 846 CML patients (94%) received a TKI during a median of 4.2 years of follow-up, the investigators reported. First-line therapy usually consisted of imatinib (89%), followed by nilotinib (9%) and dasatinib (1%).

The TKI cohort had 78 arterial and venous events during 3,969 person-years of follow-up, compared with 250 events during 21,917 person-years of follow-up for controls, for a statistically significant incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.2). Individual IRRs for arterial and venous events also reached statistical significance at 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1-2.1) and 2.0 (95% CI, 1.2-3.3), respectively. Deep venous thrombosis and myocardial infarction accounted for most of the excess risk, with IRRs of 2.2 (95% CI, 1.1-4.4) and 1.9 (95% CI, 1.3-2.7), respectively.

When investigators looked only at the TKI cohort, they found that the rates of arterial thromboembolic events were highest for nilotinib (29 events per 1,000 person-years), followed by dasatinib (19 events per 1,000 person-years) and imatinib (13 events per 1,000 person-years). Nilotinib also was associated with a substantially higher rate of all arterial and venous events (42/1,000 person-years) than dasatinib (20/1,000 person-years) and imatinib (16/1,000 person-years).

Furthermore, nilotinib and dasatinib were associated with higher rates of myocardial infarctions (29 and 19 per 1,000 person-years, respectively) and cerebrovascular ischemic events (11 and 4 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively) than was imatinib (8 events per 1,000 person-years and 4 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively). However, the absolute numbers of events were too small to allow for statistical comparisons, the researchers said.

“The observed increase in thrombotic events may be related to CML itself, the treatment administered, or both,” they noted, but “the prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with CML before diagnosis was similar to that of the control population, [which] might indicate a treatment-related association.”

Among the 31 patients on TKIs who had a myocardial infarction, 26 (84%) had been previously diagnosed with at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease, including diabetes (19%), atrial fibrillation (26%), angina pectoris (39%), hypertension (55%), and hyperlipidemia (23%).

Most patients who received nilotinib or dasatinib had previously received imatinib, meaning that they could have had more advanced disease that increased their risk of adverse events, according to the researchers.

“The small number of events also leads us to exercise caution in drawing any strong conclusions,” they added. “Future data from the Swedish CML register will provide more robust evidence regarding the risks of individual drugs as exposure time increases.”

The researchers received no funding for the work. Dr. Dahlén disclosed grant support from Merck outside the submitted work. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Ariad, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, and Squibb.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors were associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events among chronic myeloid leukemia patients.

Major finding: These patients had 1.7 times the rate of arterial or venous events, compared with the general population (95% confidence interval, 1.3-2.2).

Data source: A retrospective, registry-based cohort study of 896 patients with CML and 4,438 population-based controls matched by age and sex.

Disclosures: The researchers received no funding for the work. Dr. Dahlén disclosed grant support from Merck outside the submitted work. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Ariad, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, and Squibb.

Most CML patients who stop nilotinib stay in remission

© ASCO/Matt Herp

CHICAGO—Nearly 60% of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients who switch to nilotinib from imatinib maintain treatment-free remission for 48 weeks after stopping treatment, according to a new study, ENESTop, presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7054).

Treatment-free remission (TFR)—stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy after achieving a sustained deep molecular response—is an emerging treatment goal for patients with CML in chronic phase (CML-CP).

Results from Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials–Complete Molecular Response (ENESTcmr) demonstrated that patients on long-term imatinib who had not achieved MR4.5 were more likely to achieve this response by switching to nilotinib than by remaining on imatinib.

“This suggests that, compared with remaining on imatinib, switching to nilotinib may enable more of these patients to reach a molecular response level required for attempting to achieve TFR in clinical trials,” said lead author Timothy Hughes, MD, of University of Adelaide in Australia.

ENESTop is the first study, providing the largest set of prospective TFR data to date, to specifically assess TFR in patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response after switching from imatinib to nilotinib.

The trial evaluated 126 patients who were able to achieve a sustained deep molecular response with nilotinib, but not with prior imatinib therapy.

The study met its primary endpoint of the proportion of patients without confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of major molecular response (MMR) within 48 weeks of nilotinib discontinuation in the TFR phase.

Some 57.9% patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response following at least three years of nilotinib therapy maintained a molecular response 48 weeks after stopping treatment.

Of the 51 patients with confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of MMR who restarted nilotinib, 98.0% regained at least MMR, with 94.1% regaining MR4.0 and 92.2% regaining MR4.5.

By weeks 12 and 13 of treatment reinitiation with nilotinib, half of retreated patients already achieved MR4.0 and MR4.5, respectively.

One patient entered the treatment reinitiation phase, but did not regain MMR by 20 weeks and discontinued the study.

“MR4.5 achieved following the switch from imatinib to nilotinib,” Dr Hughes said, “was durable in most patients; more than three quarters of enrolled patients were eligible to enter the TFR phase.”

No new safety signals were observed, Dr Hughes said. Consistent with reports in imatinib-treated patients, the rates of all grade musculoskeletal pain were 42.1% in the first year of the TFR phase versus 14.3% while still taking nilotinib in the consolidation phase.

Dr Hughes said the results suggest “TFR can be maintained in the majority of patients who achieve a sustained deep molecular response with nilotinib following switch from imatinib.”

He continued, “The results from ENESTop, together with those from ENESTcmr, show that a higher proportion of patients switching to nilotinib achieve MR 4.5, suggesting that a higher proportion of patients switching to nilotinib will achieve TFR compared with patients continuing on imatinib.”

Novartis is the sponsor of ENESTop and the manufacturer of imatinib (Gleevec) and nilotinib (Tasigna). Dr Hughes disclosed that he has received honoraria and research funding from Novartis. ![]()

© ASCO/Matt Herp

CHICAGO—Nearly 60% of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients who switch to nilotinib from imatinib maintain treatment-free remission for 48 weeks after stopping treatment, according to a new study, ENESTop, presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7054).

Treatment-free remission (TFR)—stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy after achieving a sustained deep molecular response—is an emerging treatment goal for patients with CML in chronic phase (CML-CP).

Results from Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials–Complete Molecular Response (ENESTcmr) demonstrated that patients on long-term imatinib who had not achieved MR4.5 were more likely to achieve this response by switching to nilotinib than by remaining on imatinib.

“This suggests that, compared with remaining on imatinib, switching to nilotinib may enable more of these patients to reach a molecular response level required for attempting to achieve TFR in clinical trials,” said lead author Timothy Hughes, MD, of University of Adelaide in Australia.

ENESTop is the first study, providing the largest set of prospective TFR data to date, to specifically assess TFR in patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response after switching from imatinib to nilotinib.

The trial evaluated 126 patients who were able to achieve a sustained deep molecular response with nilotinib, but not with prior imatinib therapy.

The study met its primary endpoint of the proportion of patients without confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of major molecular response (MMR) within 48 weeks of nilotinib discontinuation in the TFR phase.

Some 57.9% patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response following at least three years of nilotinib therapy maintained a molecular response 48 weeks after stopping treatment.

Of the 51 patients with confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of MMR who restarted nilotinib, 98.0% regained at least MMR, with 94.1% regaining MR4.0 and 92.2% regaining MR4.5.

By weeks 12 and 13 of treatment reinitiation with nilotinib, half of retreated patients already achieved MR4.0 and MR4.5, respectively.

One patient entered the treatment reinitiation phase, but did not regain MMR by 20 weeks and discontinued the study.

“MR4.5 achieved following the switch from imatinib to nilotinib,” Dr Hughes said, “was durable in most patients; more than three quarters of enrolled patients were eligible to enter the TFR phase.”

No new safety signals were observed, Dr Hughes said. Consistent with reports in imatinib-treated patients, the rates of all grade musculoskeletal pain were 42.1% in the first year of the TFR phase versus 14.3% while still taking nilotinib in the consolidation phase.

Dr Hughes said the results suggest “TFR can be maintained in the majority of patients who achieve a sustained deep molecular response with nilotinib following switch from imatinib.”

He continued, “The results from ENESTop, together with those from ENESTcmr, show that a higher proportion of patients switching to nilotinib achieve MR 4.5, suggesting that a higher proportion of patients switching to nilotinib will achieve TFR compared with patients continuing on imatinib.”

Novartis is the sponsor of ENESTop and the manufacturer of imatinib (Gleevec) and nilotinib (Tasigna). Dr Hughes disclosed that he has received honoraria and research funding from Novartis. ![]()

© ASCO/Matt Herp

CHICAGO—Nearly 60% of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients who switch to nilotinib from imatinib maintain treatment-free remission for 48 weeks after stopping treatment, according to a new study, ENESTop, presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 7054).

Treatment-free remission (TFR)—stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy after achieving a sustained deep molecular response—is an emerging treatment goal for patients with CML in chronic phase (CML-CP).

Results from Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials–Complete Molecular Response (ENESTcmr) demonstrated that patients on long-term imatinib who had not achieved MR4.5 were more likely to achieve this response by switching to nilotinib than by remaining on imatinib.

“This suggests that, compared with remaining on imatinib, switching to nilotinib may enable more of these patients to reach a molecular response level required for attempting to achieve TFR in clinical trials,” said lead author Timothy Hughes, MD, of University of Adelaide in Australia.

ENESTop is the first study, providing the largest set of prospective TFR data to date, to specifically assess TFR in patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response after switching from imatinib to nilotinib.

The trial evaluated 126 patients who were able to achieve a sustained deep molecular response with nilotinib, but not with prior imatinib therapy.

The study met its primary endpoint of the proportion of patients without confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of major molecular response (MMR) within 48 weeks of nilotinib discontinuation in the TFR phase.

Some 57.9% patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response following at least three years of nilotinib therapy maintained a molecular response 48 weeks after stopping treatment.

Of the 51 patients with confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of MMR who restarted nilotinib, 98.0% regained at least MMR, with 94.1% regaining MR4.0 and 92.2% regaining MR4.5.

By weeks 12 and 13 of treatment reinitiation with nilotinib, half of retreated patients already achieved MR4.0 and MR4.5, respectively.

One patient entered the treatment reinitiation phase, but did not regain MMR by 20 weeks and discontinued the study.

“MR4.5 achieved following the switch from imatinib to nilotinib,” Dr Hughes said, “was durable in most patients; more than three quarters of enrolled patients were eligible to enter the TFR phase.”

No new safety signals were observed, Dr Hughes said. Consistent with reports in imatinib-treated patients, the rates of all grade musculoskeletal pain were 42.1% in the first year of the TFR phase versus 14.3% while still taking nilotinib in the consolidation phase.

Dr Hughes said the results suggest “TFR can be maintained in the majority of patients who achieve a sustained deep molecular response with nilotinib following switch from imatinib.”

He continued, “The results from ENESTop, together with those from ENESTcmr, show that a higher proportion of patients switching to nilotinib achieve MR 4.5, suggesting that a higher proportion of patients switching to nilotinib will achieve TFR compared with patients continuing on imatinib.”

Novartis is the sponsor of ENESTop and the manufacturer of imatinib (Gleevec) and nilotinib (Tasigna). Dr Hughes disclosed that he has received honoraria and research funding from Novartis. ![]()

Dr. Matt Kalaycio’s top 10 hematologic oncology abstracts for ASCO 2016

Hematology News’ Editor-in-Chief Matt Kalaycio selected the following as his “top 10” picks for hematologic oncology abstracts at ASCO 2016:

Abstract 7000: Final results of a phase III randomized trial of CPX-351 versus 7+3 in older patients with newly diagnosed high risk (secondary) AML

Comment: When any treatment appears to improve survival, compared with 7+3 for AML, all must take notice.

Abstract 7001: Treatment-free remission (TFR) in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with frontline nilotinib: Results from the ENESTFreedom study

Comment: About 50% of the CML patients treated with frontline nilotinib are eventually able to stop the drug and successfully stay off of it. That means more patients in treatment-free remission, compared with those initially treated with imatinib.

Link to abstract 7001

Abstract 7007: Phase Ib/2 study of venetoclax with low-dose cytarabine in treatment-naive patients age ≥ 65 with acute myelogenous leukemia

Abstract 7009: Results of a phase 1b study of venetoclax plus decitabine or azacitidine in untreated acute myeloid leukemia patients ≥ 65 years ineligible for standard induction therapy

Comment: The response rates in these older AML patients are remarkable and challenge results typically seen with 7+3 in a younger population.

Link to abstract 7007 and 7009

Abstract 7501: A prospective, multicenter, randomized study of anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab (moga) vs investigator’s choice (IC) in the treatment of patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory (R/R) adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL)

Comment: The response rate to mogamulizumab was outstanding in the largest randomized clinical trial thus far conducted for this cancer. Although rare in the USA, ATL is more common in Asia.

Link to abstract 7501

Abstract 7507: Effect of bortezomib on complete remission (CR) rate when added to bendamustine-rituximab (BR) in previously untreated high-risk (HR) follicular lymphoma (FL): A randomized phase II trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2408)

Comment: This interesting observation of improved complete remission needs longer follow-up.

Link to abstract 7507

Abstract 7519: Venetoclax activity in CLL patients who have relapsed after or are refractory to ibrutinib or idelalisib

Comment: This study has implications for practice. Venetoclax elicits a 50%-60% response rate after patients with CLL progress during treatment with B-cell receptor pathway inhibitors.

Link to abstract 7519

Abstract 7521: Acalabrutinib, a second-generation bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitor, in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Comment: This next-generation variation on ibrutinib was associated with a 96% overall response rate with fewer adverse effects such as atrial fibrillation.

Link to abstract 7521

Abstract 8000: Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) versus novel agent-based therapy for multiple myeloma (MM): A randomized phase 3 study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN02/HO95 MM trial)

Comment: Other trials are underway to address the role of upfront ASCT for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. While the last word on this issue has yet to be written, ASCT remains the standard of care for MM patients after induction.

Link to abstract 8000

LBA4: Phase III randomized controlled study of daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (DVd) versus bortezomib and dexamethasone (Vd) in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): CASTOR study

Comment: As predicted by most, the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib-based therapy increases response rates, compared with bortezomib-based alone. Efficacy is becoming less of a concern with myeloma treatment than is economics..

Look for the full, final text of this abstract to be posted online at 7:30 AM (EDT) on Sunday, June 5.

Hematology News’ Editor-in-Chief Matt Kalaycio selected the following as his “top 10” picks for hematologic oncology abstracts at ASCO 2016:

Abstract 7000: Final results of a phase III randomized trial of CPX-351 versus 7+3 in older patients with newly diagnosed high risk (secondary) AML

Comment: When any treatment appears to improve survival, compared with 7+3 for AML, all must take notice.

Abstract 7001: Treatment-free remission (TFR) in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with frontline nilotinib: Results from the ENESTFreedom study

Comment: About 50% of the CML patients treated with frontline nilotinib are eventually able to stop the drug and successfully stay off of it. That means more patients in treatment-free remission, compared with those initially treated with imatinib.

Link to abstract 7001

Abstract 7007: Phase Ib/2 study of venetoclax with low-dose cytarabine in treatment-naive patients age ≥ 65 with acute myelogenous leukemia