User login

VP Biden to AACR: Help me help you

Stronger teamwork among researchers, sharing data, and realignment of incentives for scientific breakthroughs, in addition to more funding, are key steps needed to advance cancer research, Vice President Joe Biden said during the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

During a plenary speech to close the meeting, Vice President Biden praised the dedication of current cancer researchers and pledged to break down the walls that prevent them from achieving more progress in the field.

“I made a commitment that I will – as I gain this information and knowledge – I will eliminate the barriers that get in your way, get in the way of science and research and development,” he said. “I had to ... learn from all of you how we can proceed, how we can break down silos, how we can accommodate more rapidly the efforts you’re making.”

Vice President Biden, who is leading a new $1 billion initiative to eliminate cancer called “Moonshot,” outlined the top obstacles to cancer research he has garnered from recent visits with renowned cancer scientists and research leaders around the world. This includes a lack of unity among researchers, poor rewards for novel research, and limited data sharing, he said.

“The way the system now is set up, researchers are not incentivized to share their data,” Vice President Biden said, acknowledging that some medical experts are against the idea. “But every expert I’ve spoken to said you need to share these data to move this process rapidly.”

Involving patients earlier in clinical trials design is also a primary focus, he said. Patients should understand more about trials and be more open to signing up.

He noted the “incredible” research currently being conducted by various entities, such as AACR’s Project Genie, Orion Foundation, and The Parker Institute. Mr. Biden stressed however, that such efforts are too isolated.

“It raises [the] question: ‘Why is all this being done separately?’ ” Vice President Biden said. “Why is so much money being spent when if it’s aggregated, everyone acknowledges, the answers would come more quickly?”

Incentives for new research and the way in which funding is alloted must also be redesigned, he stressed. Today, it takes too long for researchers to get projects approved by the government and funding dispersed. He acknowledged the difficulty researchers face in obtaining grants and the fact that those who think “outside the box” are less likely to receive funding.

“It seems to me that we slow down our best minds by making them spend years in the lab before they can get their own grants and, when they do, they spend a third of their time writing a grant that takes months to be approved and awarded,” he said. “It’s like asking Derek Jeter to take several years off to sell bonds to build Yankee stadium.”

The Vice President did not purport to have all the answers, and asked those at the AARC meeting to provide feedback on his suggestions.

“The question I’d ask you to contemplate, because I’d like you to communicate with us, is, ‘Does it require realigning incentives; changing behaviors to take advantage of this inflection point? Does it require sharing more knowledge, treatment, and understanding? Or does that slow the process up?’ ”

He added,“I hope you all know it, but you’re one of the most valuable resources that our great country has, those of you sitting in this room. So ask your institutions, your colleagues, your mentors, your administrators: How can we move your ideas faster together in the interest of patients?”

The Vice President’s Moonshot initiative was announced during President Obama’s 2016 State of the Union Address. The effort includes a new Cancer Moonshot Task Force that will focus on federal investments, targeted incentives, private sector efforts from industry and philanthropy, patient engagement initiatives, and other mechanisms to support cancer research and enable progress in treatment and care, according to the White House. As part of the plan, the President’s fiscal 2017 budget proposes $755 million in mandatory funds for new cancer-related research activities at the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. The initiative also includes increased investments by the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs in cancer research, including through funding centers of excellence focused on specific cancers and conducting longitudinal studies to determine risk factors and enhance treatment.

On Twitter @legal_med

Stronger teamwork among researchers, sharing data, and realignment of incentives for scientific breakthroughs, in addition to more funding, are key steps needed to advance cancer research, Vice President Joe Biden said during the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

During a plenary speech to close the meeting, Vice President Biden praised the dedication of current cancer researchers and pledged to break down the walls that prevent them from achieving more progress in the field.

“I made a commitment that I will – as I gain this information and knowledge – I will eliminate the barriers that get in your way, get in the way of science and research and development,” he said. “I had to ... learn from all of you how we can proceed, how we can break down silos, how we can accommodate more rapidly the efforts you’re making.”

Vice President Biden, who is leading a new $1 billion initiative to eliminate cancer called “Moonshot,” outlined the top obstacles to cancer research he has garnered from recent visits with renowned cancer scientists and research leaders around the world. This includes a lack of unity among researchers, poor rewards for novel research, and limited data sharing, he said.

“The way the system now is set up, researchers are not incentivized to share their data,” Vice President Biden said, acknowledging that some medical experts are against the idea. “But every expert I’ve spoken to said you need to share these data to move this process rapidly.”

Involving patients earlier in clinical trials design is also a primary focus, he said. Patients should understand more about trials and be more open to signing up.

He noted the “incredible” research currently being conducted by various entities, such as AACR’s Project Genie, Orion Foundation, and The Parker Institute. Mr. Biden stressed however, that such efforts are too isolated.

“It raises [the] question: ‘Why is all this being done separately?’ ” Vice President Biden said. “Why is so much money being spent when if it’s aggregated, everyone acknowledges, the answers would come more quickly?”

Incentives for new research and the way in which funding is alloted must also be redesigned, he stressed. Today, it takes too long for researchers to get projects approved by the government and funding dispersed. He acknowledged the difficulty researchers face in obtaining grants and the fact that those who think “outside the box” are less likely to receive funding.

“It seems to me that we slow down our best minds by making them spend years in the lab before they can get their own grants and, when they do, they spend a third of their time writing a grant that takes months to be approved and awarded,” he said. “It’s like asking Derek Jeter to take several years off to sell bonds to build Yankee stadium.”

The Vice President did not purport to have all the answers, and asked those at the AARC meeting to provide feedback on his suggestions.

“The question I’d ask you to contemplate, because I’d like you to communicate with us, is, ‘Does it require realigning incentives; changing behaviors to take advantage of this inflection point? Does it require sharing more knowledge, treatment, and understanding? Or does that slow the process up?’ ”

He added,“I hope you all know it, but you’re one of the most valuable resources that our great country has, those of you sitting in this room. So ask your institutions, your colleagues, your mentors, your administrators: How can we move your ideas faster together in the interest of patients?”

The Vice President’s Moonshot initiative was announced during President Obama’s 2016 State of the Union Address. The effort includes a new Cancer Moonshot Task Force that will focus on federal investments, targeted incentives, private sector efforts from industry and philanthropy, patient engagement initiatives, and other mechanisms to support cancer research and enable progress in treatment and care, according to the White House. As part of the plan, the President’s fiscal 2017 budget proposes $755 million in mandatory funds for new cancer-related research activities at the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. The initiative also includes increased investments by the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs in cancer research, including through funding centers of excellence focused on specific cancers and conducting longitudinal studies to determine risk factors and enhance treatment.

On Twitter @legal_med

Stronger teamwork among researchers, sharing data, and realignment of incentives for scientific breakthroughs, in addition to more funding, are key steps needed to advance cancer research, Vice President Joe Biden said during the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

During a plenary speech to close the meeting, Vice President Biden praised the dedication of current cancer researchers and pledged to break down the walls that prevent them from achieving more progress in the field.

“I made a commitment that I will – as I gain this information and knowledge – I will eliminate the barriers that get in your way, get in the way of science and research and development,” he said. “I had to ... learn from all of you how we can proceed, how we can break down silos, how we can accommodate more rapidly the efforts you’re making.”

Vice President Biden, who is leading a new $1 billion initiative to eliminate cancer called “Moonshot,” outlined the top obstacles to cancer research he has garnered from recent visits with renowned cancer scientists and research leaders around the world. This includes a lack of unity among researchers, poor rewards for novel research, and limited data sharing, he said.

“The way the system now is set up, researchers are not incentivized to share their data,” Vice President Biden said, acknowledging that some medical experts are against the idea. “But every expert I’ve spoken to said you need to share these data to move this process rapidly.”

Involving patients earlier in clinical trials design is also a primary focus, he said. Patients should understand more about trials and be more open to signing up.

He noted the “incredible” research currently being conducted by various entities, such as AACR’s Project Genie, Orion Foundation, and The Parker Institute. Mr. Biden stressed however, that such efforts are too isolated.

“It raises [the] question: ‘Why is all this being done separately?’ ” Vice President Biden said. “Why is so much money being spent when if it’s aggregated, everyone acknowledges, the answers would come more quickly?”

Incentives for new research and the way in which funding is alloted must also be redesigned, he stressed. Today, it takes too long for researchers to get projects approved by the government and funding dispersed. He acknowledged the difficulty researchers face in obtaining grants and the fact that those who think “outside the box” are less likely to receive funding.

“It seems to me that we slow down our best minds by making them spend years in the lab before they can get their own grants and, when they do, they spend a third of their time writing a grant that takes months to be approved and awarded,” he said. “It’s like asking Derek Jeter to take several years off to sell bonds to build Yankee stadium.”

The Vice President did not purport to have all the answers, and asked those at the AARC meeting to provide feedback on his suggestions.

“The question I’d ask you to contemplate, because I’d like you to communicate with us, is, ‘Does it require realigning incentives; changing behaviors to take advantage of this inflection point? Does it require sharing more knowledge, treatment, and understanding? Or does that slow the process up?’ ”

He added,“I hope you all know it, but you’re one of the most valuable resources that our great country has, those of you sitting in this room. So ask your institutions, your colleagues, your mentors, your administrators: How can we move your ideas faster together in the interest of patients?”

The Vice President’s Moonshot initiative was announced during President Obama’s 2016 State of the Union Address. The effort includes a new Cancer Moonshot Task Force that will focus on federal investments, targeted incentives, private sector efforts from industry and philanthropy, patient engagement initiatives, and other mechanisms to support cancer research and enable progress in treatment and care, according to the White House. As part of the plan, the President’s fiscal 2017 budget proposes $755 million in mandatory funds for new cancer-related research activities at the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. The initiative also includes increased investments by the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs in cancer research, including through funding centers of excellence focused on specific cancers and conducting longitudinal studies to determine risk factors and enhance treatment.

On Twitter @legal_med

FROM THE AACR ANNUAL MEETING

Model used to estimate CSCs in CML

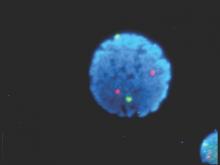

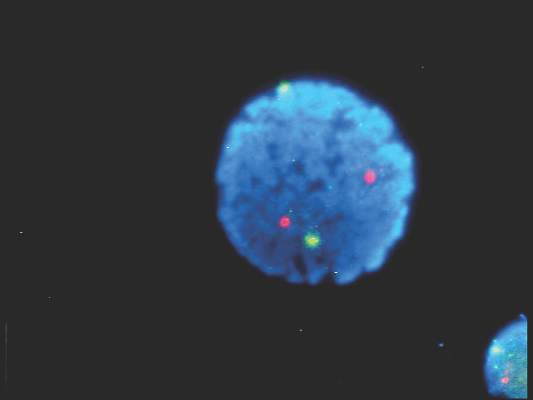

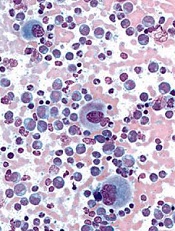

Image from UC San Diego

Scientists say they have developed a model that can be used to calculate the proportion of cancer stem cells (CSCs) present over the course of treatment.

The model is designed to enable estimation of CSC fractions from longitudinal measurements of tumor burden.

The scientists tested the model in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and found evidence to suggest the proportion of CSCs increases

substantially during extended treatment.

The team believes the model could eventually be used to help doctors predict tumor development and help them select suitable treatments for cancer patients.

“Cancer stem cells not only promote the growth of a tumor, they can also be resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy,” said Philipp Altrock, PhD, of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“If we can estimate the number of cancer stem cells at diagnosis and over the course of treatment, the treatment can be tailored accordingly.”

Dr Altrock and his colleagues discussed this possibility in Cancer Research.

The team first explained that their model incorporates tumor dynamics and tumor burden information. They said tumor expansion and regression curves can be leveraged to estimate the proportion of CSCs in individual patients at baseline and during therapy.

To test their model, the scientists used 2 independent cohorts of CML patients. The team evaluated the growth and decline of CML over the course of treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib.

Based on the change of disease burden during treatment, the model calculated the proportion of CSCs.

Results suggested the proportion of CSCs in CML patients increases 100-fold after a year of treatment with imatinib. And that proportion continues to increase up to 1000-fold after 5 years of treatment.

The scientists noted that this model is parameter-free, so it can be applied to different types of cancer. However, they said further development is required before the model can be used in clinical practice. ![]()

Image from UC San Diego

Scientists say they have developed a model that can be used to calculate the proportion of cancer stem cells (CSCs) present over the course of treatment.

The model is designed to enable estimation of CSC fractions from longitudinal measurements of tumor burden.

The scientists tested the model in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and found evidence to suggest the proportion of CSCs increases

substantially during extended treatment.

The team believes the model could eventually be used to help doctors predict tumor development and help them select suitable treatments for cancer patients.

“Cancer stem cells not only promote the growth of a tumor, they can also be resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy,” said Philipp Altrock, PhD, of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“If we can estimate the number of cancer stem cells at diagnosis and over the course of treatment, the treatment can be tailored accordingly.”

Dr Altrock and his colleagues discussed this possibility in Cancer Research.

The team first explained that their model incorporates tumor dynamics and tumor burden information. They said tumor expansion and regression curves can be leveraged to estimate the proportion of CSCs in individual patients at baseline and during therapy.

To test their model, the scientists used 2 independent cohorts of CML patients. The team evaluated the growth and decline of CML over the course of treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib.

Based on the change of disease burden during treatment, the model calculated the proportion of CSCs.

Results suggested the proportion of CSCs in CML patients increases 100-fold after a year of treatment with imatinib. And that proportion continues to increase up to 1000-fold after 5 years of treatment.

The scientists noted that this model is parameter-free, so it can be applied to different types of cancer. However, they said further development is required before the model can be used in clinical practice. ![]()

Image from UC San Diego

Scientists say they have developed a model that can be used to calculate the proportion of cancer stem cells (CSCs) present over the course of treatment.

The model is designed to enable estimation of CSC fractions from longitudinal measurements of tumor burden.

The scientists tested the model in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and found evidence to suggest the proportion of CSCs increases

substantially during extended treatment.

The team believes the model could eventually be used to help doctors predict tumor development and help them select suitable treatments for cancer patients.

“Cancer stem cells not only promote the growth of a tumor, they can also be resistant to radiotherapy and chemotherapy,” said Philipp Altrock, PhD, of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“If we can estimate the number of cancer stem cells at diagnosis and over the course of treatment, the treatment can be tailored accordingly.”

Dr Altrock and his colleagues discussed this possibility in Cancer Research.

The team first explained that their model incorporates tumor dynamics and tumor burden information. They said tumor expansion and regression curves can be leveraged to estimate the proportion of CSCs in individual patients at baseline and during therapy.

To test their model, the scientists used 2 independent cohorts of CML patients. The team evaluated the growth and decline of CML over the course of treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib.

Based on the change of disease burden during treatment, the model calculated the proportion of CSCs.

Results suggested the proportion of CSCs in CML patients increases 100-fold after a year of treatment with imatinib. And that proportion continues to increase up to 1000-fold after 5 years of treatment.

The scientists noted that this model is parameter-free, so it can be applied to different types of cancer. However, they said further development is required before the model can be used in clinical practice. ![]()

Targeted corticosteroids cut GVHD incidence

Short-term low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis reduces the incidence of graft-vs.-host disease in patients who undergo allogeneic haploidentical stem-cell transplantation to treat hematologic neoplasms, according to a report published online April 18 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The key to selecting patients most likely to benefit from the corticosteroid therapy is to identify those at high risk for graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) using two biomarkers: high levels of CD56bright natural killer cells in allogeneic grafts or high CD4:CD8 ratios in bone marrow grafts, according to Dr. Ying-Jun Chang of Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, and associates.

The investigators performed an open-label trial involving 228 patients aged 15-60 years treated at a single medical center during an 18-month period for acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, or other hematologic neoplasms. Using the two biomarkers, the patients were categorized as either high or low risk for developing GVHD. They were randomly assigned to three study groups: 72 high-risk patients who received short-term low-dose corticosteroids, 73 high-risk patients who received usual care, and 83 low-risk patients who received usual care.

The cumulative 100-day incidence of acute grade-II to grade-IV GVHD was significantly lower in the high-risk patients who received prophylaxis (21%) than in the high-risk patients who did not receive prophylaxis (48%). In fact, corticosteroids decreased the rate of GVHD so that it was comparable with that in the low-risk patients (26%), Dr. Chang and associates said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63l.8817).

Moreover, in the high-risk patients the median interval until GVHD developed was 25 days for those who took corticosteroids, compared with only 15 days for those who did not. Median times to myeloid recovery and platelet recovery were significantly shorter for high-risk patients who received corticosteroids than for either of the other study groups. However, 3-year overall survival and leukemia-free survival were comparable among the three study groups.

The short-term low-dose regimen of corticosteroids did not raise the rate of adverse events, including infection, which suggests that it is preferable to standard corticosteroid regimens in this patient population. The incidences of cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder, hemorrhagic cystitis, bacteremia, and invasive fungal infections were comparable among the three study groups. Of note, the incidences of osteonecrosis of the femoral head and secondary hypertension were significantly lower among high-risk patients who received corticosteroid prophylaxis than among those who did not.

“These results provide the first test, to our knowledge, of a novel risk-stratification-directed prophylaxis strategy that effectively prevented acute GVHD among patients who were at high risk for GVHD, without unnecessarily exposing patients who were at low risk to excessive toxicity from additional immunosuppressive agents,” Dr. Chang and associates said.

Despite the encouraging results of Chang et al, it would be premature to routinely use corticosteroid prophylaxis to prevent GVHD until further studies are completed.

This study wasn’t sufficiently powered to determine whether corticosteroids reduced treatment-specific mortality or improved overall survival. Future studies must examine these end points, as well as relapse rates, before this method of prophylaxis is widely adopted.

Dr. Edwin P. Alyea is at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Alyea made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Chang’s report (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.0902).

Despite the encouraging results of Chang et al, it would be premature to routinely use corticosteroid prophylaxis to prevent GVHD until further studies are completed.

This study wasn’t sufficiently powered to determine whether corticosteroids reduced treatment-specific mortality or improved overall survival. Future studies must examine these end points, as well as relapse rates, before this method of prophylaxis is widely adopted.

Dr. Edwin P. Alyea is at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Alyea made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Chang’s report (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.0902).

Despite the encouraging results of Chang et al, it would be premature to routinely use corticosteroid prophylaxis to prevent GVHD until further studies are completed.

This study wasn’t sufficiently powered to determine whether corticosteroids reduced treatment-specific mortality or improved overall survival. Future studies must examine these end points, as well as relapse rates, before this method of prophylaxis is widely adopted.

Dr. Edwin P. Alyea is at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Alyea made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Chang’s report (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.0902).

Short-term low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis reduces the incidence of graft-vs.-host disease in patients who undergo allogeneic haploidentical stem-cell transplantation to treat hematologic neoplasms, according to a report published online April 18 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The key to selecting patients most likely to benefit from the corticosteroid therapy is to identify those at high risk for graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) using two biomarkers: high levels of CD56bright natural killer cells in allogeneic grafts or high CD4:CD8 ratios in bone marrow grafts, according to Dr. Ying-Jun Chang of Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, and associates.

The investigators performed an open-label trial involving 228 patients aged 15-60 years treated at a single medical center during an 18-month period for acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, or other hematologic neoplasms. Using the two biomarkers, the patients were categorized as either high or low risk for developing GVHD. They were randomly assigned to three study groups: 72 high-risk patients who received short-term low-dose corticosteroids, 73 high-risk patients who received usual care, and 83 low-risk patients who received usual care.

The cumulative 100-day incidence of acute grade-II to grade-IV GVHD was significantly lower in the high-risk patients who received prophylaxis (21%) than in the high-risk patients who did not receive prophylaxis (48%). In fact, corticosteroids decreased the rate of GVHD so that it was comparable with that in the low-risk patients (26%), Dr. Chang and associates said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63l.8817).

Moreover, in the high-risk patients the median interval until GVHD developed was 25 days for those who took corticosteroids, compared with only 15 days for those who did not. Median times to myeloid recovery and platelet recovery were significantly shorter for high-risk patients who received corticosteroids than for either of the other study groups. However, 3-year overall survival and leukemia-free survival were comparable among the three study groups.

The short-term low-dose regimen of corticosteroids did not raise the rate of adverse events, including infection, which suggests that it is preferable to standard corticosteroid regimens in this patient population. The incidences of cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder, hemorrhagic cystitis, bacteremia, and invasive fungal infections were comparable among the three study groups. Of note, the incidences of osteonecrosis of the femoral head and secondary hypertension were significantly lower among high-risk patients who received corticosteroid prophylaxis than among those who did not.

“These results provide the first test, to our knowledge, of a novel risk-stratification-directed prophylaxis strategy that effectively prevented acute GVHD among patients who were at high risk for GVHD, without unnecessarily exposing patients who were at low risk to excessive toxicity from additional immunosuppressive agents,” Dr. Chang and associates said.

Short-term low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis reduces the incidence of graft-vs.-host disease in patients who undergo allogeneic haploidentical stem-cell transplantation to treat hematologic neoplasms, according to a report published online April 18 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The key to selecting patients most likely to benefit from the corticosteroid therapy is to identify those at high risk for graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) using two biomarkers: high levels of CD56bright natural killer cells in allogeneic grafts or high CD4:CD8 ratios in bone marrow grafts, according to Dr. Ying-Jun Chang of Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, and associates.

The investigators performed an open-label trial involving 228 patients aged 15-60 years treated at a single medical center during an 18-month period for acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, or other hematologic neoplasms. Using the two biomarkers, the patients were categorized as either high or low risk for developing GVHD. They were randomly assigned to three study groups: 72 high-risk patients who received short-term low-dose corticosteroids, 73 high-risk patients who received usual care, and 83 low-risk patients who received usual care.

The cumulative 100-day incidence of acute grade-II to grade-IV GVHD was significantly lower in the high-risk patients who received prophylaxis (21%) than in the high-risk patients who did not receive prophylaxis (48%). In fact, corticosteroids decreased the rate of GVHD so that it was comparable with that in the low-risk patients (26%), Dr. Chang and associates said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63l.8817).

Moreover, in the high-risk patients the median interval until GVHD developed was 25 days for those who took corticosteroids, compared with only 15 days for those who did not. Median times to myeloid recovery and platelet recovery were significantly shorter for high-risk patients who received corticosteroids than for either of the other study groups. However, 3-year overall survival and leukemia-free survival were comparable among the three study groups.

The short-term low-dose regimen of corticosteroids did not raise the rate of adverse events, including infection, which suggests that it is preferable to standard corticosteroid regimens in this patient population. The incidences of cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder, hemorrhagic cystitis, bacteremia, and invasive fungal infections were comparable among the three study groups. Of note, the incidences of osteonecrosis of the femoral head and secondary hypertension were significantly lower among high-risk patients who received corticosteroid prophylaxis than among those who did not.

“These results provide the first test, to our knowledge, of a novel risk-stratification-directed prophylaxis strategy that effectively prevented acute GVHD among patients who were at high risk for GVHD, without unnecessarily exposing patients who were at low risk to excessive toxicity from additional immunosuppressive agents,” Dr. Chang and associates said.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Short-term low-dose corticosteroid prophylaxis reduces the incidence of the GVHD in patients who undergo haploidentical stem-cell transplantation to treat hematologic neoplasms.

Major finding: The 100-day incidence of acute GVHD was significantly lower in the high-risk patients who received corticosteroid prophylaxis (21%) than in the high-risk patients who did not (48%).

Data source: An open-label randomized controlled trial involving 228 Chinese patients who underwent stem-cell transplantation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Beijing Committee of Science and Technology, the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Dr. Chang and associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

TKI trial leaves questions unanswered

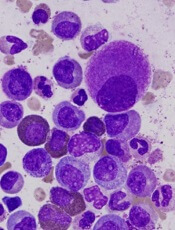

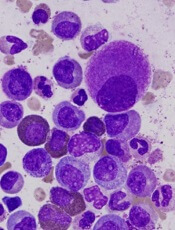

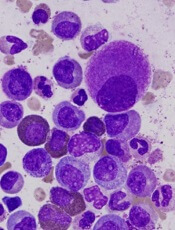

Image by Difu Wu

The phase 3 EPIC trial, a comparison of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), has left some questions unanswered.

The trial did not determine whether the third-generation TKI ponatinib is more effective than the first-generation TKI imatinib for patients with previously untreated chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The study was terminated early due to safety concerns associated with ponatinib, so the primary endpoint could only be analyzed in a small number of patients.

Results in these patients showed no significant difference in that endpoint—major molecular response (MMR) at 12 months—between the imatinib and ponatinib arms.

Results in the entire study cohort suggested that, overall, ponatinib was more toxic than imatinib. In particular, ponatinib produced more arterial occlusive events.

However, the trial’s investigators have questioned whether reducing the dose of ponatinib might change that.

Jeffrey H. Lipton, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and his colleagues reported results from the EPIC trial in The Lancet Oncology. The trial was supported by Ariad Pharmaceuticals.

Problems with ponatinib

Ponatinib was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2012 to treat adults with CML or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia that is resistant to or intolerant of other TKIs.

In October 2013, follow-up results from the phase 2 PACE trial suggested ponatinib can increase a patient’s risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events. So all trials of the drug were placed on partial clinical hold, with the exception of the EPIC trial, which was terminated.

That November, the FDA suspended sales and marketing of ponatinib, pending results of a safety evaluation. In December, the agency decided ponatinib could return to the market if new safety measures were implemented. In January 2014, ponatinib was put back on the market in the US.

EPIC trial

The trial enrolled 307 patients with newly diagnosed, chronic-phase CML. Patients were randomized to receive ponatinib at 45 mg (n=155) or imatinib at 400 mg (n=152) once daily until progression, unacceptable toxicity, or other criteria for withdrawal were met.

The median age was 55 (range, 18-89) in the ponatinib arm and 52 (range, 18-86) in the imatinib arm. Most patients were male—63% and 61%, respectively—and most had an ECOG performance status of 0—75% and 78%, respectively.

Patients were randomized between August 14, 2012, and October 9, 2013, and the trial was terminated on October 17, 2013.

Because of the early termination, only 10 patients in the ponatinib arm and 13 in the imatinib arm were evaluable for the primary endpoint—MMR at 12 months. Eighty percent (8/10) of the evaluable patients in the ponatinib arm and 38% (5/13) of those in the imatinib arm achieved an MMR at 12 months (P=0.074).

The investigators also evaluated the incidence of MMR at any time in patients with any post-baseline molecular response assessment. This time, the incidence of MMR was significantly higher in the ponatinib arm than the imatinib arm—41% (61/149) and 18% (25/142), respectively (P<0.0001).

All of the patients were evaluable for safety—154 in the ponatinib arm and 152 in the imatinib arm.

Arterial occlusive events occurred in 7% (n=11) of patients in the ponatinib arm and 2% (n=3) in the imatinib arm (P=0.052). These events were considered serious in 6% (n=10) and 1% (n=1), respectively (P=0.010).

Common grade 3/4 adverse events—in the ponatinib and imatinib arms, respectively—were increased lipase (14% vs 2%), thrombocytopenia (12% vs 7%), rash (6% vs 1%), and neutropenia (3% vs 8%).

Serious adverse events that occurred in 3 or more patients in the ponatinib arm were pancreatitis (n=5), atrial fibrillation (n=3), and thrombocytopenia (n=3). There were no serious adverse events that occurred in 3 or more patients in the imatinib arm.

Dr Lipton and his colleagues said the premature termination of the EPIC trial restricts the interpretation of its results, but the available data provide some insight into the activity and safety of ponatinib in previously untreated CML.

The investigators also noted that data from this trial and the clinical development program for ponatinib suggest that lowering doses of the drug could improve its vascular safety profile and, therefore, the benefit-risk balance.

Two ongoing trials (NCT02467270 and NCT02627677) may provide more insight. Both are investigating starting doses of ponatinib at 15 mg or 30 mg. ![]()

Image by Difu Wu

The phase 3 EPIC trial, a comparison of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), has left some questions unanswered.

The trial did not determine whether the third-generation TKI ponatinib is more effective than the first-generation TKI imatinib for patients with previously untreated chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The study was terminated early due to safety concerns associated with ponatinib, so the primary endpoint could only be analyzed in a small number of patients.

Results in these patients showed no significant difference in that endpoint—major molecular response (MMR) at 12 months—between the imatinib and ponatinib arms.

Results in the entire study cohort suggested that, overall, ponatinib was more toxic than imatinib. In particular, ponatinib produced more arterial occlusive events.

However, the trial’s investigators have questioned whether reducing the dose of ponatinib might change that.

Jeffrey H. Lipton, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and his colleagues reported results from the EPIC trial in The Lancet Oncology. The trial was supported by Ariad Pharmaceuticals.

Problems with ponatinib

Ponatinib was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2012 to treat adults with CML or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia that is resistant to or intolerant of other TKIs.

In October 2013, follow-up results from the phase 2 PACE trial suggested ponatinib can increase a patient’s risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events. So all trials of the drug were placed on partial clinical hold, with the exception of the EPIC trial, which was terminated.

That November, the FDA suspended sales and marketing of ponatinib, pending results of a safety evaluation. In December, the agency decided ponatinib could return to the market if new safety measures were implemented. In January 2014, ponatinib was put back on the market in the US.

EPIC trial

The trial enrolled 307 patients with newly diagnosed, chronic-phase CML. Patients were randomized to receive ponatinib at 45 mg (n=155) or imatinib at 400 mg (n=152) once daily until progression, unacceptable toxicity, or other criteria for withdrawal were met.

The median age was 55 (range, 18-89) in the ponatinib arm and 52 (range, 18-86) in the imatinib arm. Most patients were male—63% and 61%, respectively—and most had an ECOG performance status of 0—75% and 78%, respectively.

Patients were randomized between August 14, 2012, and October 9, 2013, and the trial was terminated on October 17, 2013.

Because of the early termination, only 10 patients in the ponatinib arm and 13 in the imatinib arm were evaluable for the primary endpoint—MMR at 12 months. Eighty percent (8/10) of the evaluable patients in the ponatinib arm and 38% (5/13) of those in the imatinib arm achieved an MMR at 12 months (P=0.074).

The investigators also evaluated the incidence of MMR at any time in patients with any post-baseline molecular response assessment. This time, the incidence of MMR was significantly higher in the ponatinib arm than the imatinib arm—41% (61/149) and 18% (25/142), respectively (P<0.0001).

All of the patients were evaluable for safety—154 in the ponatinib arm and 152 in the imatinib arm.

Arterial occlusive events occurred in 7% (n=11) of patients in the ponatinib arm and 2% (n=3) in the imatinib arm (P=0.052). These events were considered serious in 6% (n=10) and 1% (n=1), respectively (P=0.010).

Common grade 3/4 adverse events—in the ponatinib and imatinib arms, respectively—were increased lipase (14% vs 2%), thrombocytopenia (12% vs 7%), rash (6% vs 1%), and neutropenia (3% vs 8%).

Serious adverse events that occurred in 3 or more patients in the ponatinib arm were pancreatitis (n=5), atrial fibrillation (n=3), and thrombocytopenia (n=3). There were no serious adverse events that occurred in 3 or more patients in the imatinib arm.

Dr Lipton and his colleagues said the premature termination of the EPIC trial restricts the interpretation of its results, but the available data provide some insight into the activity and safety of ponatinib in previously untreated CML.

The investigators also noted that data from this trial and the clinical development program for ponatinib suggest that lowering doses of the drug could improve its vascular safety profile and, therefore, the benefit-risk balance.

Two ongoing trials (NCT02467270 and NCT02627677) may provide more insight. Both are investigating starting doses of ponatinib at 15 mg or 30 mg. ![]()

Image by Difu Wu

The phase 3 EPIC trial, a comparison of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), has left some questions unanswered.

The trial did not determine whether the third-generation TKI ponatinib is more effective than the first-generation TKI imatinib for patients with previously untreated chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The study was terminated early due to safety concerns associated with ponatinib, so the primary endpoint could only be analyzed in a small number of patients.

Results in these patients showed no significant difference in that endpoint—major molecular response (MMR) at 12 months—between the imatinib and ponatinib arms.

Results in the entire study cohort suggested that, overall, ponatinib was more toxic than imatinib. In particular, ponatinib produced more arterial occlusive events.

However, the trial’s investigators have questioned whether reducing the dose of ponatinib might change that.

Jeffrey H. Lipton, MD, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and his colleagues reported results from the EPIC trial in The Lancet Oncology. The trial was supported by Ariad Pharmaceuticals.

Problems with ponatinib

Ponatinib was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2012 to treat adults with CML or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia that is resistant to or intolerant of other TKIs.

In October 2013, follow-up results from the phase 2 PACE trial suggested ponatinib can increase a patient’s risk of arterial and venous thrombotic events. So all trials of the drug were placed on partial clinical hold, with the exception of the EPIC trial, which was terminated.

That November, the FDA suspended sales and marketing of ponatinib, pending results of a safety evaluation. In December, the agency decided ponatinib could return to the market if new safety measures were implemented. In January 2014, ponatinib was put back on the market in the US.

EPIC trial

The trial enrolled 307 patients with newly diagnosed, chronic-phase CML. Patients were randomized to receive ponatinib at 45 mg (n=155) or imatinib at 400 mg (n=152) once daily until progression, unacceptable toxicity, or other criteria for withdrawal were met.

The median age was 55 (range, 18-89) in the ponatinib arm and 52 (range, 18-86) in the imatinib arm. Most patients were male—63% and 61%, respectively—and most had an ECOG performance status of 0—75% and 78%, respectively.

Patients were randomized between August 14, 2012, and October 9, 2013, and the trial was terminated on October 17, 2013.

Because of the early termination, only 10 patients in the ponatinib arm and 13 in the imatinib arm were evaluable for the primary endpoint—MMR at 12 months. Eighty percent (8/10) of the evaluable patients in the ponatinib arm and 38% (5/13) of those in the imatinib arm achieved an MMR at 12 months (P=0.074).

The investigators also evaluated the incidence of MMR at any time in patients with any post-baseline molecular response assessment. This time, the incidence of MMR was significantly higher in the ponatinib arm than the imatinib arm—41% (61/149) and 18% (25/142), respectively (P<0.0001).

All of the patients were evaluable for safety—154 in the ponatinib arm and 152 in the imatinib arm.

Arterial occlusive events occurred in 7% (n=11) of patients in the ponatinib arm and 2% (n=3) in the imatinib arm (P=0.052). These events were considered serious in 6% (n=10) and 1% (n=1), respectively (P=0.010).

Common grade 3/4 adverse events—in the ponatinib and imatinib arms, respectively—were increased lipase (14% vs 2%), thrombocytopenia (12% vs 7%), rash (6% vs 1%), and neutropenia (3% vs 8%).

Serious adverse events that occurred in 3 or more patients in the ponatinib arm were pancreatitis (n=5), atrial fibrillation (n=3), and thrombocytopenia (n=3). There were no serious adverse events that occurred in 3 or more patients in the imatinib arm.

Dr Lipton and his colleagues said the premature termination of the EPIC trial restricts the interpretation of its results, but the available data provide some insight into the activity and safety of ponatinib in previously untreated CML.

The investigators also noted that data from this trial and the clinical development program for ponatinib suggest that lowering doses of the drug could improve its vascular safety profile and, therefore, the benefit-risk balance.

Two ongoing trials (NCT02467270 and NCT02627677) may provide more insight. Both are investigating starting doses of ponatinib at 15 mg or 30 mg. ![]()

In newly diagnosed CLL, mutation tests are advised

Patients with newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia should standardly undergo immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region gene (IGHV) mutation status and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) tests, based on the results of a meta-analysis published in Blood.

“This change will help define the minimal standard initial prognostic evaluation for patients with CLL and help facilitate use of the powerful, recently developed, integrated prognostic indices, all of which are dependent on these 2 variables,” wrote Dr. Sameer A. Parikh of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and associates.

IGHV and FISH have prognostic value independent of clinical stage in patients with newly diagnosed and previously untreated CLL, they said (Blood. 2016;127[14]:1752-60). Better understanding of the patient’s risk of disease progression at diagnosis can guide counseling and follow-up intervals, and could potentially influence the decision to treat high-risk patients on early intervention protocols.

IGHV and FISH also appear to provide additional information on progression-free and overall survival.

The researchers cautioned, however, that the results of these tests should not be used to initiate CLL-specific therapy. Only patients who meet indications for therapy based on the 2008 International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia guidelines should receive treatment.

Further, they noted, the median age of patients included in studies that they analyzed was 64 years; the median age of patients with CLL is 72 years. The prognostic abilities of IGHV mutation and FISH may differ in these older individuals with CLL.

The researchers analyzed 31 studies that met the criteria for inclusion – full-length publications that included at least 200 patients and reported on the prognostic value of IGHV and/or FISH for predicting progression-free or overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed CLL.

They found that the median progression-free survival (range, about 1-5 years) was significantly shorter for patients with unmutated IGHV genes, than was the median progression-free survival (range, about 9-19 years) for those with mutated IGHV genes. Similarly, the median overall survival was significantly shorter for patients with unmutated IGHV (range, about 3-10 years) than for those with mutated IGHV (range, about 18-26 years).

For patients with high-risk FISH (including del17p13 and del11q23), the median progression-free survival was significantly shorter (range, about 0.1-5 years) than for those with low/intermediate-risk FISH (including del13q, normal, and trisomy 12; range, about 1.5-22 years). Median overall survival also significantly differed, ranging from about 3-10 years for patients with high-risk FISH and from about 7.5-20.5 years for those with low/intermediate-risk FISH.

In multivariable analyses, the hazard ratio for high-risk FISH ranged from 1.3 to 4.7 for progression-free survival and from 0.9 to 8.2 for overall survival. In studies reporting the results of multivariable analysis, high-risk FISH remained an independent predictor of progression-free survival in 8 of 17 studies and of overall survival in 10 of 14 studies, including in 10 of 13 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of IGHV.

In multivariable analyses, IGHV remained an independent predictor of progression-free survival in 15 of 18 studies, including 12 of 15 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of FISH. IGHV remained an independent predictor of overall survival in 11 of 15 studies reporting the results of multivariable analysis, including 10 of 14 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of FISH.

Patients with newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia should standardly undergo immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region gene (IGHV) mutation status and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) tests, based on the results of a meta-analysis published in Blood.

“This change will help define the minimal standard initial prognostic evaluation for patients with CLL and help facilitate use of the powerful, recently developed, integrated prognostic indices, all of which are dependent on these 2 variables,” wrote Dr. Sameer A. Parikh of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and associates.

IGHV and FISH have prognostic value independent of clinical stage in patients with newly diagnosed and previously untreated CLL, they said (Blood. 2016;127[14]:1752-60). Better understanding of the patient’s risk of disease progression at diagnosis can guide counseling and follow-up intervals, and could potentially influence the decision to treat high-risk patients on early intervention protocols.

IGHV and FISH also appear to provide additional information on progression-free and overall survival.

The researchers cautioned, however, that the results of these tests should not be used to initiate CLL-specific therapy. Only patients who meet indications for therapy based on the 2008 International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia guidelines should receive treatment.

Further, they noted, the median age of patients included in studies that they analyzed was 64 years; the median age of patients with CLL is 72 years. The prognostic abilities of IGHV mutation and FISH may differ in these older individuals with CLL.

The researchers analyzed 31 studies that met the criteria for inclusion – full-length publications that included at least 200 patients and reported on the prognostic value of IGHV and/or FISH for predicting progression-free or overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed CLL.

They found that the median progression-free survival (range, about 1-5 years) was significantly shorter for patients with unmutated IGHV genes, than was the median progression-free survival (range, about 9-19 years) for those with mutated IGHV genes. Similarly, the median overall survival was significantly shorter for patients with unmutated IGHV (range, about 3-10 years) than for those with mutated IGHV (range, about 18-26 years).

For patients with high-risk FISH (including del17p13 and del11q23), the median progression-free survival was significantly shorter (range, about 0.1-5 years) than for those with low/intermediate-risk FISH (including del13q, normal, and trisomy 12; range, about 1.5-22 years). Median overall survival also significantly differed, ranging from about 3-10 years for patients with high-risk FISH and from about 7.5-20.5 years for those with low/intermediate-risk FISH.

In multivariable analyses, the hazard ratio for high-risk FISH ranged from 1.3 to 4.7 for progression-free survival and from 0.9 to 8.2 for overall survival. In studies reporting the results of multivariable analysis, high-risk FISH remained an independent predictor of progression-free survival in 8 of 17 studies and of overall survival in 10 of 14 studies, including in 10 of 13 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of IGHV.

In multivariable analyses, IGHV remained an independent predictor of progression-free survival in 15 of 18 studies, including 12 of 15 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of FISH. IGHV remained an independent predictor of overall survival in 11 of 15 studies reporting the results of multivariable analysis, including 10 of 14 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of FISH.

Patients with newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia should standardly undergo immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region gene (IGHV) mutation status and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) tests, based on the results of a meta-analysis published in Blood.

“This change will help define the minimal standard initial prognostic evaluation for patients with CLL and help facilitate use of the powerful, recently developed, integrated prognostic indices, all of which are dependent on these 2 variables,” wrote Dr. Sameer A. Parikh of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and associates.

IGHV and FISH have prognostic value independent of clinical stage in patients with newly diagnosed and previously untreated CLL, they said (Blood. 2016;127[14]:1752-60). Better understanding of the patient’s risk of disease progression at diagnosis can guide counseling and follow-up intervals, and could potentially influence the decision to treat high-risk patients on early intervention protocols.

IGHV and FISH also appear to provide additional information on progression-free and overall survival.

The researchers cautioned, however, that the results of these tests should not be used to initiate CLL-specific therapy. Only patients who meet indications for therapy based on the 2008 International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia guidelines should receive treatment.

Further, they noted, the median age of patients included in studies that they analyzed was 64 years; the median age of patients with CLL is 72 years. The prognostic abilities of IGHV mutation and FISH may differ in these older individuals with CLL.

The researchers analyzed 31 studies that met the criteria for inclusion – full-length publications that included at least 200 patients and reported on the prognostic value of IGHV and/or FISH for predicting progression-free or overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed CLL.

They found that the median progression-free survival (range, about 1-5 years) was significantly shorter for patients with unmutated IGHV genes, than was the median progression-free survival (range, about 9-19 years) for those with mutated IGHV genes. Similarly, the median overall survival was significantly shorter for patients with unmutated IGHV (range, about 3-10 years) than for those with mutated IGHV (range, about 18-26 years).

For patients with high-risk FISH (including del17p13 and del11q23), the median progression-free survival was significantly shorter (range, about 0.1-5 years) than for those with low/intermediate-risk FISH (including del13q, normal, and trisomy 12; range, about 1.5-22 years). Median overall survival also significantly differed, ranging from about 3-10 years for patients with high-risk FISH and from about 7.5-20.5 years for those with low/intermediate-risk FISH.

In multivariable analyses, the hazard ratio for high-risk FISH ranged from 1.3 to 4.7 for progression-free survival and from 0.9 to 8.2 for overall survival. In studies reporting the results of multivariable analysis, high-risk FISH remained an independent predictor of progression-free survival in 8 of 17 studies and of overall survival in 10 of 14 studies, including in 10 of 13 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of IGHV.

In multivariable analyses, IGHV remained an independent predictor of progression-free survival in 15 of 18 studies, including 12 of 15 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of FISH. IGHV remained an independent predictor of overall survival in 11 of 15 studies reporting the results of multivariable analysis, including 10 of 14 studies adjusting for the prognostic impact of FISH.

FROM BLOOD

Feds advance cancer moonshot with expert panel, outline of goals

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

FROM NEJM

Cyclophosphamide nets low rate of chronic GVHD after mobilized blood cell transplantation

High-dose cyclophosphamide is safe and effective when given as prophylaxis for chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) to patients who have undergone transplantation of mobilized blood cells, finds a phase 2 trial reported in Blood.

Investigators led by Dr. Marco Mielcarek, medical director of the Adult Blood and Marrow Transplant Program and an oncologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, enrolled in the trial 43 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies.

The patients underwent myeloablative conditioning followed by transplantation with growth factor–mobilized blood cells from related or unrelated donors, and were given high-dose cyclophosphamide on two early posttransplantation days.

Main results showed that the cumulative 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD was 16%, less than half of the roughly 35% seen historically with conventional immunosuppression.

Moreover, cyclophosphamide did not appear to compromise engraftment or control of the underlying malignancy. Only a single patient, one with an HLA-mismatched donor, had failure of primary engraftment; after amendment of the protocol to require HLA matching, there were no additional cases. Just 17% of patients experienced a recurrence of their malignancy by 2 years.

Taken together, the findings suggest that high-dose cyclophosphamide—as combined with two myeloablative conditioning options (to accommodate different malignancies) and with posttransplantation cyclosporine (to reduce the risk of acute GVHD)—may eliminate most of the drawbacks to using mobilized blood cells for transplantation, according to the investigators.

“If these findings are confirmed in future studies, HLA-matched mobilized blood cell transplantation may gain even greater acceptance and further replace marrow as a source of stem cells for most indications,” they maintain.

The patients studied had a median age of 43 years, and slightly more than half were in remission without minimal residual disease.

Blood cells were mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Overall, 28% of patients received grafts from related donors, while 72% received grafts from unrelated donors.

For pretransplant conditioning, patients received fludarabine and targeted busulfan, or total body irradiation with use of a minimum dose of 12 Gy.

The patients were given cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg per day on days 3 and 4 after transplantation. This was followed by cyclosporine starting on day 5.

The cumulative 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD as defined by National Institutes of Health criteria (i.e., that requiring systemic immunosuppressive therapy)—the trial’s primary endpoint—was 16%, which fell just short of the goal of 15% the investigators were aiming for (Blood. 2016;127:1502-8). Analyses failed to identify any predictors of this outcome.

Although the estimated cumulative incidence of grade 2 acute GVHD was high, at 77%, none of the patients developed grade 3 or 4 acute GVHD, according to the investigators, who disclosed that they had no competing financial interests.

The single patient who experienced failure of primary engraftment had familial myelodysplastic syndrome and had received a graft from an HLA A-antigen–mismatched unrelated donor.

The 2-year cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality was 14%, and the 2-year cumulative incidence of recurrent malignancy was 17%. Projected overall survival was 70%.

Among the 42 patients having at least a year of follow-up, 50% were alive and free of relapse without any systemic immunosuppression at 1 year after transplantation.

High-dose cyclophosphamide is safe and effective when given as prophylaxis for chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) to patients who have undergone transplantation of mobilized blood cells, finds a phase 2 trial reported in Blood.

Investigators led by Dr. Marco Mielcarek, medical director of the Adult Blood and Marrow Transplant Program and an oncologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, enrolled in the trial 43 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies.

The patients underwent myeloablative conditioning followed by transplantation with growth factor–mobilized blood cells from related or unrelated donors, and were given high-dose cyclophosphamide on two early posttransplantation days.

Main results showed that the cumulative 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD was 16%, less than half of the roughly 35% seen historically with conventional immunosuppression.

Moreover, cyclophosphamide did not appear to compromise engraftment or control of the underlying malignancy. Only a single patient, one with an HLA-mismatched donor, had failure of primary engraftment; after amendment of the protocol to require HLA matching, there were no additional cases. Just 17% of patients experienced a recurrence of their malignancy by 2 years.

Taken together, the findings suggest that high-dose cyclophosphamide—as combined with two myeloablative conditioning options (to accommodate different malignancies) and with posttransplantation cyclosporine (to reduce the risk of acute GVHD)—may eliminate most of the drawbacks to using mobilized blood cells for transplantation, according to the investigators.

“If these findings are confirmed in future studies, HLA-matched mobilized blood cell transplantation may gain even greater acceptance and further replace marrow as a source of stem cells for most indications,” they maintain.

The patients studied had a median age of 43 years, and slightly more than half were in remission without minimal residual disease.

Blood cells were mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Overall, 28% of patients received grafts from related donors, while 72% received grafts from unrelated donors.

For pretransplant conditioning, patients received fludarabine and targeted busulfan, or total body irradiation with use of a minimum dose of 12 Gy.

The patients were given cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg per day on days 3 and 4 after transplantation. This was followed by cyclosporine starting on day 5.

The cumulative 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD as defined by National Institutes of Health criteria (i.e., that requiring systemic immunosuppressive therapy)—the trial’s primary endpoint—was 16%, which fell just short of the goal of 15% the investigators were aiming for (Blood. 2016;127:1502-8). Analyses failed to identify any predictors of this outcome.

Although the estimated cumulative incidence of grade 2 acute GVHD was high, at 77%, none of the patients developed grade 3 or 4 acute GVHD, according to the investigators, who disclosed that they had no competing financial interests.

The single patient who experienced failure of primary engraftment had familial myelodysplastic syndrome and had received a graft from an HLA A-antigen–mismatched unrelated donor.

The 2-year cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality was 14%, and the 2-year cumulative incidence of recurrent malignancy was 17%. Projected overall survival was 70%.

Among the 42 patients having at least a year of follow-up, 50% were alive and free of relapse without any systemic immunosuppression at 1 year after transplantation.

High-dose cyclophosphamide is safe and effective when given as prophylaxis for chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) to patients who have undergone transplantation of mobilized blood cells, finds a phase 2 trial reported in Blood.

Investigators led by Dr. Marco Mielcarek, medical director of the Adult Blood and Marrow Transplant Program and an oncologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, enrolled in the trial 43 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies.

The patients underwent myeloablative conditioning followed by transplantation with growth factor–mobilized blood cells from related or unrelated donors, and were given high-dose cyclophosphamide on two early posttransplantation days.

Main results showed that the cumulative 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD was 16%, less than half of the roughly 35% seen historically with conventional immunosuppression.

Moreover, cyclophosphamide did not appear to compromise engraftment or control of the underlying malignancy. Only a single patient, one with an HLA-mismatched donor, had failure of primary engraftment; after amendment of the protocol to require HLA matching, there were no additional cases. Just 17% of patients experienced a recurrence of their malignancy by 2 years.

Taken together, the findings suggest that high-dose cyclophosphamide—as combined with two myeloablative conditioning options (to accommodate different malignancies) and with posttransplantation cyclosporine (to reduce the risk of acute GVHD)—may eliminate most of the drawbacks to using mobilized blood cells for transplantation, according to the investigators.

“If these findings are confirmed in future studies, HLA-matched mobilized blood cell transplantation may gain even greater acceptance and further replace marrow as a source of stem cells for most indications,” they maintain.

The patients studied had a median age of 43 years, and slightly more than half were in remission without minimal residual disease.

Blood cells were mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Overall, 28% of patients received grafts from related donors, while 72% received grafts from unrelated donors.

For pretransplant conditioning, patients received fludarabine and targeted busulfan, or total body irradiation with use of a minimum dose of 12 Gy.

The patients were given cyclophosphamide at 50 mg/kg per day on days 3 and 4 after transplantation. This was followed by cyclosporine starting on day 5.

The cumulative 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD as defined by National Institutes of Health criteria (i.e., that requiring systemic immunosuppressive therapy)—the trial’s primary endpoint—was 16%, which fell just short of the goal of 15% the investigators were aiming for (Blood. 2016;127:1502-8). Analyses failed to identify any predictors of this outcome.

Although the estimated cumulative incidence of grade 2 acute GVHD was high, at 77%, none of the patients developed grade 3 or 4 acute GVHD, according to the investigators, who disclosed that they had no competing financial interests.

The single patient who experienced failure of primary engraftment had familial myelodysplastic syndrome and had received a graft from an HLA A-antigen–mismatched unrelated donor.

The 2-year cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality was 14%, and the 2-year cumulative incidence of recurrent malignancy was 17%. Projected overall survival was 70%.

Among the 42 patients having at least a year of follow-up, 50% were alive and free of relapse without any systemic immunosuppression at 1 year after transplantation.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: High-dose posttransplant cyclophosphamide is safe and effective for reducing the risk of chronic GVHD after mobilized blood cell transplantation.

Major finding: The cumulative 1-year incidence of chronic GVHD requiring immunosuppressive therapy was 16%.

Data source: A single-arm trial among 43 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies undergoing growth factor–mobilized blood cell transplantation.

Disclosures: The authors disclosed that they have no competing financial interests.

High costs limit CML patients’ access to TKIs

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A new study suggests that cost-sharing policies in the US create a barrier to the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Researchers examined Medicare claims data and found that “Part D” (prescription drug plan) co-insurance policies for “specialty drugs” seem to be reducing or delaying the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in patients with CML.

The team reported these findings in the American Journal of Managed Care.

“High out-of-pocket costs for specialty drugs appear to pose a very real barrier to treatment,” said study author Jalpa A. Doshi, PhD, of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

While there is no standard definition for specialty drugs, the term typically refers to medications requiring special handling, administration, or monitoring. Most are aimed at treating chronic or life-threatening diseases.

Although specialty drugs typically tend to offer significant medical advances over non-specialty drugs, they are correspondingly more expensive. In 2014, such drugs accounted for less than 1% of prescriptions in the US but nearly a third of total prescription spending.

While insurers have been imposing higher cost-sharing requirements as part of their efforts to manage specialty drug spending, there has been limited information about the corresponding impact on patients.

“[I]t was particularly important to examine the extent to which the aggressive cost-sharing policies for specialty drugs seen under Medicare Part D, which are increasingly making their way into the private insurance market, adversely impact access to these treatments even for a condition like cancer,” Dr Doshi said.

So she and her colleagues examined the impact of specialty drug cost-sharing under the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit on patients with CML. The team analyzed Medicare data on patients who were newly diagnosed with CML to examine whether and how quickly they initiated TKI treatment.

The researchers compared patients who were eligible for low-income subsidies and therefore faced nominal out-of-pocket costs to patients who faced average out-of-pocket costs of $2600 or more for their first 30-day TKI prescription fill.

Results showed that patients in the high-cost group were significantly less likely than the low-cost group to have a Part D claim for a TKI prescription within 6 months of their CML diagnosis. The rates were 45.3% and 66.9%, respectively (P<0.001).

Patients in the high cost-sharing group also took twice as long, on average, to initiate TKI treatment. The mean time to fill a TKI prescription was 50.9 days in the high-cost group and 23.7 days in the low-cost group (P<0.001).

“Medicare Part D was created to increase access to prescription drug treatment among beneficiaries, but our data suggest that current policies are interfering with that goal when it comes to specialty drugs,” Dr Doshi said.

She added that making Part D out-of-pocket costs more consistent and limiting them to more reasonable sums would help mitigate this negative impact.

Dr Doshi and her colleagues are now pursuing further studies of the impact of Part D cost-sharing policies in different disease areas. They hope to gain a better understanding of changes in drug access and of the long-range clinical outcomes and costs associated with any delays or interruptions in treatment.

“We need to know if the current aggressive cost-sharing arrangements have adverse long-term impacts on health and perhaps, paradoxically, increase overall spending due to complications of poorly controlled disease,” Dr Doshi said. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A new study suggests that cost-sharing policies in the US create a barrier to the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).