User login

New anticancer drugs linked to increased costs, life expectancy

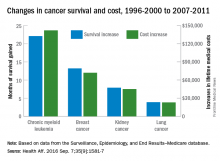

New anticancer drugs are often expensive and have been accompanied by large increases in the cost of medical treatment, but they also are associated with gains in life expectancy, according to an analysis of Medicare data published online.

Investigators looked at four different types of cancer – breast, kidney, lung, and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) – over two time periods: 1996-2000 and 2007-2011. Patients treated for CML during 2007-2011 had the largest increases in both average lifetime medical cost ($142,000) and months of life gained (22.1) over those treated during 1996-2000, reported David H. Howard, PhD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and his associates.

Breast cancer patients had the next-largest increases: 13.2 months of life expectancy and $72,000 in lifetime medical cost for those who received physician-administered intravenous drugs. For breast cancer patients who received only oral drugs, the increases were 2 months of life and $9,000 in lifetime cost, they noted.

Patients with kidney cancer had an average life-expectancy increase of 7.9 months and a cost increase of $45,000, but those estimates don’t fully reflect the effect of several oral drugs that were introduced after 2007 but did not come into widespread use during the entire study period, Dr. Howard and his associates noted (Health Aff. 2016 Sep 7;35[9]:1581-7).

Lung cancer patients experienced the smallest changes between the two time periods, with an increase in life expectancy of 3.9 months for those who received physician-administered anticancer drugs and a lifetime medical cost increase of $23,000. Patients with lung cancer who did not receive such drugs had increases of 0.7 months of life expectancy and $4,000 in lifetime medical costs.

The researchers used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database, and all costs are adjusted to 2012 dollars. Data collection was supported by the California Department of Health and funding for the study was provided by Pfizer. Three of Dr. Howard’s five coinvestigators are Pfizer employees.

New anticancer drugs are often expensive and have been accompanied by large increases in the cost of medical treatment, but they also are associated with gains in life expectancy, according to an analysis of Medicare data published online.

Investigators looked at four different types of cancer – breast, kidney, lung, and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) – over two time periods: 1996-2000 and 2007-2011. Patients treated for CML during 2007-2011 had the largest increases in both average lifetime medical cost ($142,000) and months of life gained (22.1) over those treated during 1996-2000, reported David H. Howard, PhD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and his associates.

Breast cancer patients had the next-largest increases: 13.2 months of life expectancy and $72,000 in lifetime medical cost for those who received physician-administered intravenous drugs. For breast cancer patients who received only oral drugs, the increases were 2 months of life and $9,000 in lifetime cost, they noted.

Patients with kidney cancer had an average life-expectancy increase of 7.9 months and a cost increase of $45,000, but those estimates don’t fully reflect the effect of several oral drugs that were introduced after 2007 but did not come into widespread use during the entire study period, Dr. Howard and his associates noted (Health Aff. 2016 Sep 7;35[9]:1581-7).

Lung cancer patients experienced the smallest changes between the two time periods, with an increase in life expectancy of 3.9 months for those who received physician-administered anticancer drugs and a lifetime medical cost increase of $23,000. Patients with lung cancer who did not receive such drugs had increases of 0.7 months of life expectancy and $4,000 in lifetime medical costs.

The researchers used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database, and all costs are adjusted to 2012 dollars. Data collection was supported by the California Department of Health and funding for the study was provided by Pfizer. Three of Dr. Howard’s five coinvestigators are Pfizer employees.

New anticancer drugs are often expensive and have been accompanied by large increases in the cost of medical treatment, but they also are associated with gains in life expectancy, according to an analysis of Medicare data published online.

Investigators looked at four different types of cancer – breast, kidney, lung, and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) – over two time periods: 1996-2000 and 2007-2011. Patients treated for CML during 2007-2011 had the largest increases in both average lifetime medical cost ($142,000) and months of life gained (22.1) over those treated during 1996-2000, reported David H. Howard, PhD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and his associates.

Breast cancer patients had the next-largest increases: 13.2 months of life expectancy and $72,000 in lifetime medical cost for those who received physician-administered intravenous drugs. For breast cancer patients who received only oral drugs, the increases were 2 months of life and $9,000 in lifetime cost, they noted.

Patients with kidney cancer had an average life-expectancy increase of 7.9 months and a cost increase of $45,000, but those estimates don’t fully reflect the effect of several oral drugs that were introduced after 2007 but did not come into widespread use during the entire study period, Dr. Howard and his associates noted (Health Aff. 2016 Sep 7;35[9]:1581-7).

Lung cancer patients experienced the smallest changes between the two time periods, with an increase in life expectancy of 3.9 months for those who received physician-administered anticancer drugs and a lifetime medical cost increase of $23,000. Patients with lung cancer who did not receive such drugs had increases of 0.7 months of life expectancy and $4,000 in lifetime medical costs.

The researchers used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database, and all costs are adjusted to 2012 dollars. Data collection was supported by the California Department of Health and funding for the study was provided by Pfizer. Three of Dr. Howard’s five coinvestigators are Pfizer employees.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Combo could provide cure for CML, team says

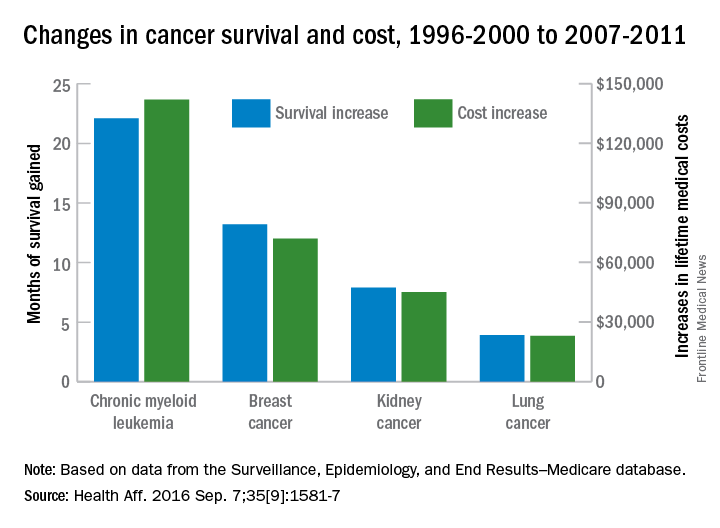

Preclinical research suggests that combining a BCL2 inhibitor with a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) can eradicate leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

In mouse models of CML, combining the TKI nilotinib with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax enhanced antileukemic activity and decreased numbers of long-term LSCs.

The 2-drug combination exhibited similar activity in samples from patients with blast crisis CML.

“Our results demonstrate that . . . employing combined blockade of BCL-2 and BCR-ABL has the potential for curing CML and significantly improving outcomes for patients with blast crisis, and, as such, warrants clinical testing,” said Michael Andreeff, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues reported these results in Science Translational Medicine. The study was funded by National Institutes of Health, the Paul and Mary Haas Chair in Genetics, and Abbvie Inc., the company developing venetoclax.

The researchers noted that, although BCR-ABL TKIs have proven effective against CML, they rarely eliminate CML stem cells.

“It is believed that TKIs do not eliminate residual stem cells because they are not dependent on BCR-ABL signaling,” said study author Bing Carter, PhD, also of MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Hence, cures of CML with TKIs are rare.”

Dr Carter has worked for several years on eliminating residual CML stem cells, which could mean CML patients would no longer require long-term treatment with TKIs. Based on the current study, she and her colleagues believe that combining a TKI with a BCL-2 inhibitor may be a solution.

The researchers found that targeting both BCL-2 and BCR-ABL with venetoclax and nilotinib, respectively, exerted “potent antileukemic activity” and prolonged survival in BCR-ABL transgenic mice.

After stopping treatment, the median survival was 34.5 days for control mice, 70 days for mice treated with nilotinib alone (P=0.2146), 115 days for mice treated with venetoclax alone (P=0.0079), and 168 days for mice treated with nilotinib and venetoclax in combination (P=0.0002).

Subsequent experiments in mice showed that nilotinib alone did not significantly affect the frequency of long-term LSCs, although venetoclax alone did. Treatment with both drugs reduced the frequency of long-term LSCs even more than venetoclax alone.

Finally, the researchers tested venetoclax, nilotinib, and the combination in cells from 6 patients with blast crisis CML, all of whom had failed treatment with at least 1 TKI.

The team found that venetoclax and nilotinib had a synergistic apoptotic effect on bulk and stem/progenitor CML cells.

The researchers said these results suggest that combined inhibition of BCL-2 and BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase has the potential to significantly improve the depth of response and cure rates of chronic phase and blast crisis CML.

“This combination strategy may also apply to other malignancies that depend on kinase signaling for progression and maintenance,” Dr Andreeff added. ![]()

Preclinical research suggests that combining a BCL2 inhibitor with a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) can eradicate leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

In mouse models of CML, combining the TKI nilotinib with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax enhanced antileukemic activity and decreased numbers of long-term LSCs.

The 2-drug combination exhibited similar activity in samples from patients with blast crisis CML.

“Our results demonstrate that . . . employing combined blockade of BCL-2 and BCR-ABL has the potential for curing CML and significantly improving outcomes for patients with blast crisis, and, as such, warrants clinical testing,” said Michael Andreeff, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues reported these results in Science Translational Medicine. The study was funded by National Institutes of Health, the Paul and Mary Haas Chair in Genetics, and Abbvie Inc., the company developing venetoclax.

The researchers noted that, although BCR-ABL TKIs have proven effective against CML, they rarely eliminate CML stem cells.

“It is believed that TKIs do not eliminate residual stem cells because they are not dependent on BCR-ABL signaling,” said study author Bing Carter, PhD, also of MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Hence, cures of CML with TKIs are rare.”

Dr Carter has worked for several years on eliminating residual CML stem cells, which could mean CML patients would no longer require long-term treatment with TKIs. Based on the current study, she and her colleagues believe that combining a TKI with a BCL-2 inhibitor may be a solution.

The researchers found that targeting both BCL-2 and BCR-ABL with venetoclax and nilotinib, respectively, exerted “potent antileukemic activity” and prolonged survival in BCR-ABL transgenic mice.

After stopping treatment, the median survival was 34.5 days for control mice, 70 days for mice treated with nilotinib alone (P=0.2146), 115 days for mice treated with venetoclax alone (P=0.0079), and 168 days for mice treated with nilotinib and venetoclax in combination (P=0.0002).

Subsequent experiments in mice showed that nilotinib alone did not significantly affect the frequency of long-term LSCs, although venetoclax alone did. Treatment with both drugs reduced the frequency of long-term LSCs even more than venetoclax alone.

Finally, the researchers tested venetoclax, nilotinib, and the combination in cells from 6 patients with blast crisis CML, all of whom had failed treatment with at least 1 TKI.

The team found that venetoclax and nilotinib had a synergistic apoptotic effect on bulk and stem/progenitor CML cells.

The researchers said these results suggest that combined inhibition of BCL-2 and BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase has the potential to significantly improve the depth of response and cure rates of chronic phase and blast crisis CML.

“This combination strategy may also apply to other malignancies that depend on kinase signaling for progression and maintenance,” Dr Andreeff added. ![]()

Preclinical research suggests that combining a BCL2 inhibitor with a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) can eradicate leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

In mouse models of CML, combining the TKI nilotinib with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax enhanced antileukemic activity and decreased numbers of long-term LSCs.

The 2-drug combination exhibited similar activity in samples from patients with blast crisis CML.

“Our results demonstrate that . . . employing combined blockade of BCL-2 and BCR-ABL has the potential for curing CML and significantly improving outcomes for patients with blast crisis, and, as such, warrants clinical testing,” said Michael Andreeff, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Dr Andreeff and his colleagues reported these results in Science Translational Medicine. The study was funded by National Institutes of Health, the Paul and Mary Haas Chair in Genetics, and Abbvie Inc., the company developing venetoclax.

The researchers noted that, although BCR-ABL TKIs have proven effective against CML, they rarely eliminate CML stem cells.

“It is believed that TKIs do not eliminate residual stem cells because they are not dependent on BCR-ABL signaling,” said study author Bing Carter, PhD, also of MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Hence, cures of CML with TKIs are rare.”

Dr Carter has worked for several years on eliminating residual CML stem cells, which could mean CML patients would no longer require long-term treatment with TKIs. Based on the current study, she and her colleagues believe that combining a TKI with a BCL-2 inhibitor may be a solution.

The researchers found that targeting both BCL-2 and BCR-ABL with venetoclax and nilotinib, respectively, exerted “potent antileukemic activity” and prolonged survival in BCR-ABL transgenic mice.

After stopping treatment, the median survival was 34.5 days for control mice, 70 days for mice treated with nilotinib alone (P=0.2146), 115 days for mice treated with venetoclax alone (P=0.0079), and 168 days for mice treated with nilotinib and venetoclax in combination (P=0.0002).

Subsequent experiments in mice showed that nilotinib alone did not significantly affect the frequency of long-term LSCs, although venetoclax alone did. Treatment with both drugs reduced the frequency of long-term LSCs even more than venetoclax alone.

Finally, the researchers tested venetoclax, nilotinib, and the combination in cells from 6 patients with blast crisis CML, all of whom had failed treatment with at least 1 TKI.

The team found that venetoclax and nilotinib had a synergistic apoptotic effect on bulk and stem/progenitor CML cells.

The researchers said these results suggest that combined inhibition of BCL-2 and BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase has the potential to significantly improve the depth of response and cure rates of chronic phase and blast crisis CML.

“This combination strategy may also apply to other malignancies that depend on kinase signaling for progression and maintenance,” Dr Andreeff added. ![]()

NICE approves bosutinib for routine NHS use

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending that bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), be made available through the National Health Service (NHS).

This means patients will no longer have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain bosutinib.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

NICE previously considered making bosutinib available through the NHS in 2013 but decided the drug was not cost-effective. So bosutinib was made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib. ![]()

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending that bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), be made available through the National Health Service (NHS).

This means patients will no longer have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain bosutinib.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

NICE previously considered making bosutinib available through the NHS in 2013 but decided the drug was not cost-effective. So bosutinib was made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib. ![]()

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final guidance recommending that bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), be made available through the National Health Service (NHS).

This means patients will no longer have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain bosutinib.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

NICE previously considered making bosutinib available through the NHS in 2013 but decided the drug was not cost-effective. So bosutinib was made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib. ![]()

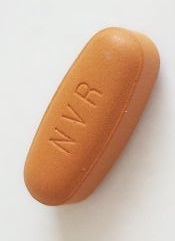

Teva launches generic imatinib tablets in US

Photo by Steven Harbour

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. has announced the US launch of imatinib mesylate, the generic equivalent of Novartis’s Gleevec®, in 100 mg and 400 mg tablets.

In the US, imatinib is approved to treat newly diagnosed Philadelphia-chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase, blast crisis, and accelerated phase, as well as Ph+

chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after failure of interferon-alpha therapy.

Imatinib is also approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia, adults with myelodysplastic syndromes or myeloproliferative neoplasms associated with platelet-derived growth factor receptor gene re-arrangements, and adults with aggressive systemic mastocytosis without the D816V c-Kit mutation or with unknown c-Kit mutational status.

In addition, imatinib is approved to treat adults with hypereosinophilic syndrome and/or chronic eosinophilic leukemia (regardless of whether they have the FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion kinase) and adults with unresectable, recurrent, and/or metastatic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

Finally, the drug is approved as an adjuvant treatment following complete gross resection of Kit (CD117)-positive gastrointestinal stromal tumors in adults.

For more details on imatinib, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo by Steven Harbour

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. has announced the US launch of imatinib mesylate, the generic equivalent of Novartis’s Gleevec®, in 100 mg and 400 mg tablets.

In the US, imatinib is approved to treat newly diagnosed Philadelphia-chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase, blast crisis, and accelerated phase, as well as Ph+

chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after failure of interferon-alpha therapy.

Imatinib is also approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia, adults with myelodysplastic syndromes or myeloproliferative neoplasms associated with platelet-derived growth factor receptor gene re-arrangements, and adults with aggressive systemic mastocytosis without the D816V c-Kit mutation or with unknown c-Kit mutational status.

In addition, imatinib is approved to treat adults with hypereosinophilic syndrome and/or chronic eosinophilic leukemia (regardless of whether they have the FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion kinase) and adults with unresectable, recurrent, and/or metastatic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

Finally, the drug is approved as an adjuvant treatment following complete gross resection of Kit (CD117)-positive gastrointestinal stromal tumors in adults.

For more details on imatinib, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo by Steven Harbour

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. has announced the US launch of imatinib mesylate, the generic equivalent of Novartis’s Gleevec®, in 100 mg and 400 mg tablets.

In the US, imatinib is approved to treat newly diagnosed Philadelphia-chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase, blast crisis, and accelerated phase, as well as Ph+

chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after failure of interferon-alpha therapy.

Imatinib is also approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia, adults with myelodysplastic syndromes or myeloproliferative neoplasms associated with platelet-derived growth factor receptor gene re-arrangements, and adults with aggressive systemic mastocytosis without the D816V c-Kit mutation or with unknown c-Kit mutational status.

In addition, imatinib is approved to treat adults with hypereosinophilic syndrome and/or chronic eosinophilic leukemia (regardless of whether they have the FIP1L1-PDGFRα fusion kinase) and adults with unresectable, recurrent, and/or metastatic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

Finally, the drug is approved as an adjuvant treatment following complete gross resection of Kit (CD117)-positive gastrointestinal stromal tumors in adults.

For more details on imatinib, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

FDA clears kit for monitoring molecular response in CML

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted premarket clearance for the QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit, a tool used to monitor molecular response (MR) in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The product is a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-based in vitro diagnostic test that quantifies BCR-ABL1 and ABL1 transcripts in total RNA from the whole blood of t(9;22)-positive CML patients expressing e13a2 and/or e14a2 fusion transcripts.

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit is not designed to diagnose CML or monitor rare transcripts resulting from t(9;22).

The kit was cleared to run on the Applied Biosystems® 7500 Fast DX Real-Time PCR Instrument. Results are reported in International Scale (IS) values.

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit was subjected to analytic and clinical review through the FDA’s de novo 510(k) premarket review pathway and secured clearance with a limit of detection of MR 4.7/0.002% IS (4.7 log molecular reduction from 100% IS).

The limit of detection was determined using real human RNA, not human-derived cell lines, ensuring that the assay reproducibly detects BCR-ABL1 RNA in at least 95% of patients at MR 4.7.

“In evaluating the QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit, we confirmed the high level of sensitivity achieved for human clinical samples measured in our laboratory at MR 4.7 (0.002% IS),” said Y. Lynn. Wang, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“The configuration of the assay—multiplexed, single-lot reagents, efficient workflow, and direct IS reporting—provided the robustness, sensitivity, and data quality we believe to be unprecedented in the market today. The high level of sensitivity will contribute to the assessment of the depth and duration of clinical response to [tyrosine kinase inhibitors] and experimental therapies.”

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit is now available for order in the US and Europe. The kit is a product of Asuragen, Inc. ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted premarket clearance for the QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit, a tool used to monitor molecular response (MR) in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The product is a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-based in vitro diagnostic test that quantifies BCR-ABL1 and ABL1 transcripts in total RNA from the whole blood of t(9;22)-positive CML patients expressing e13a2 and/or e14a2 fusion transcripts.

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit is not designed to diagnose CML or monitor rare transcripts resulting from t(9;22).

The kit was cleared to run on the Applied Biosystems® 7500 Fast DX Real-Time PCR Instrument. Results are reported in International Scale (IS) values.

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit was subjected to analytic and clinical review through the FDA’s de novo 510(k) premarket review pathway and secured clearance with a limit of detection of MR 4.7/0.002% IS (4.7 log molecular reduction from 100% IS).

The limit of detection was determined using real human RNA, not human-derived cell lines, ensuring that the assay reproducibly detects BCR-ABL1 RNA in at least 95% of patients at MR 4.7.

“In evaluating the QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit, we confirmed the high level of sensitivity achieved for human clinical samples measured in our laboratory at MR 4.7 (0.002% IS),” said Y. Lynn. Wang, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“The configuration of the assay—multiplexed, single-lot reagents, efficient workflow, and direct IS reporting—provided the robustness, sensitivity, and data quality we believe to be unprecedented in the market today. The high level of sensitivity will contribute to the assessment of the depth and duration of clinical response to [tyrosine kinase inhibitors] and experimental therapies.”

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit is now available for order in the US and Europe. The kit is a product of Asuragen, Inc. ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted premarket clearance for the QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit, a tool used to monitor molecular response (MR) in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The product is a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)-based in vitro diagnostic test that quantifies BCR-ABL1 and ABL1 transcripts in total RNA from the whole blood of t(9;22)-positive CML patients expressing e13a2 and/or e14a2 fusion transcripts.

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit is not designed to diagnose CML or monitor rare transcripts resulting from t(9;22).

The kit was cleared to run on the Applied Biosystems® 7500 Fast DX Real-Time PCR Instrument. Results are reported in International Scale (IS) values.

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit was subjected to analytic and clinical review through the FDA’s de novo 510(k) premarket review pathway and secured clearance with a limit of detection of MR 4.7/0.002% IS (4.7 log molecular reduction from 100% IS).

The limit of detection was determined using real human RNA, not human-derived cell lines, ensuring that the assay reproducibly detects BCR-ABL1 RNA in at least 95% of patients at MR 4.7.

“In evaluating the QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit, we confirmed the high level of sensitivity achieved for human clinical samples measured in our laboratory at MR 4.7 (0.002% IS),” said Y. Lynn. Wang, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“The configuration of the assay—multiplexed, single-lot reagents, efficient workflow, and direct IS reporting—provided the robustness, sensitivity, and data quality we believe to be unprecedented in the market today. The high level of sensitivity will contribute to the assessment of the depth and duration of clinical response to [tyrosine kinase inhibitors] and experimental therapies.”

The QuantideX® qPCR BCR-ABL IS Kit is now available for order in the US and Europe. The kit is a product of Asuragen, Inc. ![]()

Study may explain how LSCs evade treatment

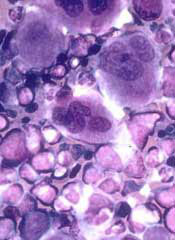

Image by Robert Paulson

New research suggests leukemia stem cells (LSCs) can “hide” in gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) and transform the tissue so they can survive treatment.

Experiments in a mouse model of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) showed that LSCs are enriched in GAT.

While there, the LSCs create a microenvironment that supports leukemic growth and resistance to treatment, and expression of the fatty acid transporter CD36 makes LSCs particularly resistant.

Craig Jordan, PhD, of University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed their findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers began by examining cancer cells found in GAT from mice with blast crisis CML. Rather than containing the expected mix of regular leukemia cells and LSCs, the tissue was enriched for LSCs.

And these GAT-resident LSCs used a different energy source than LSCs in the bone marrow microenvironment. The GAT-resident LSCs powered their survival and growth with fatty acids, manufacturing energy by the process of fatty acid oxidization.

In fact, the GAT-resident LSCs actively signaled fat to undergo lipolysis, which released fatty acids into the microenvironment.

“The basic biology was fascinating,” Dr Jordan said. “The tumor adapted the local environment to suit itself.”

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that CD36 played a role. CD36+ LSCs were enriched in GAT, were more likely to migrate to GAT than to bone marrow, and were protected from treatment by GAT.

The researchers tested the effects of several drugs (cytarabine, doxorubicin, etoposide, SN-38, irinotecan, and dasatinib) on CD36+ LSCs, CD36- LSCs, and bulk leukemia cells ex vivo.

Both CD36+ and CD36- LSCs were more resistant to treatment than bulk leukemia cells, but CD36+ LSCs were preferentially drug-resistant.

The researchers observed similar results in leukemic mice and found evidence to suggest that CD36 plays a similar role in patients with blast crisis CML and those with acute myeloid leukemia. ![]()

Image by Robert Paulson

New research suggests leukemia stem cells (LSCs) can “hide” in gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) and transform the tissue so they can survive treatment.

Experiments in a mouse model of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) showed that LSCs are enriched in GAT.

While there, the LSCs create a microenvironment that supports leukemic growth and resistance to treatment, and expression of the fatty acid transporter CD36 makes LSCs particularly resistant.

Craig Jordan, PhD, of University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed their findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers began by examining cancer cells found in GAT from mice with blast crisis CML. Rather than containing the expected mix of regular leukemia cells and LSCs, the tissue was enriched for LSCs.

And these GAT-resident LSCs used a different energy source than LSCs in the bone marrow microenvironment. The GAT-resident LSCs powered their survival and growth with fatty acids, manufacturing energy by the process of fatty acid oxidization.

In fact, the GAT-resident LSCs actively signaled fat to undergo lipolysis, which released fatty acids into the microenvironment.

“The basic biology was fascinating,” Dr Jordan said. “The tumor adapted the local environment to suit itself.”

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that CD36 played a role. CD36+ LSCs were enriched in GAT, were more likely to migrate to GAT than to bone marrow, and were protected from treatment by GAT.

The researchers tested the effects of several drugs (cytarabine, doxorubicin, etoposide, SN-38, irinotecan, and dasatinib) on CD36+ LSCs, CD36- LSCs, and bulk leukemia cells ex vivo.

Both CD36+ and CD36- LSCs were more resistant to treatment than bulk leukemia cells, but CD36+ LSCs were preferentially drug-resistant.

The researchers observed similar results in leukemic mice and found evidence to suggest that CD36 plays a similar role in patients with blast crisis CML and those with acute myeloid leukemia. ![]()

Image by Robert Paulson

New research suggests leukemia stem cells (LSCs) can “hide” in gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) and transform the tissue so they can survive treatment.

Experiments in a mouse model of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) showed that LSCs are enriched in GAT.

While there, the LSCs create a microenvironment that supports leukemic growth and resistance to treatment, and expression of the fatty acid transporter CD36 makes LSCs particularly resistant.

Craig Jordan, PhD, of University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues conducted this research and detailed their findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers began by examining cancer cells found in GAT from mice with blast crisis CML. Rather than containing the expected mix of regular leukemia cells and LSCs, the tissue was enriched for LSCs.

And these GAT-resident LSCs used a different energy source than LSCs in the bone marrow microenvironment. The GAT-resident LSCs powered their survival and growth with fatty acids, manufacturing energy by the process of fatty acid oxidization.

In fact, the GAT-resident LSCs actively signaled fat to undergo lipolysis, which released fatty acids into the microenvironment.

“The basic biology was fascinating,” Dr Jordan said. “The tumor adapted the local environment to suit itself.”

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that CD36 played a role. CD36+ LSCs were enriched in GAT, were more likely to migrate to GAT than to bone marrow, and were protected from treatment by GAT.

The researchers tested the effects of several drugs (cytarabine, doxorubicin, etoposide, SN-38, irinotecan, and dasatinib) on CD36+ LSCs, CD36- LSCs, and bulk leukemia cells ex vivo.

Both CD36+ and CD36- LSCs were more resistant to treatment than bulk leukemia cells, but CD36+ LSCs were preferentially drug-resistant.

The researchers observed similar results in leukemic mice and found evidence to suggest that CD36 plays a similar role in patients with blast crisis CML and those with acute myeloid leukemia. ![]()

Treatment-free remissions achieved in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia

Treatment-free remission attempts are safe and are achievable in most patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in chronic phase, Timothy P. Hughes, MD, and his colleagues in the international ENESTop trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The conclusion is based on follow-up data on 126 patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response (MR4.5) after switching from imatinib (Gleevec) to nilotinib (Tasigna) and discontinued nilotinib. So far, these are the largest prospective treatment-free remission data set in a population of patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response after switching from imatinib to nilotinib, Dr. Hughes, head of hematology at the University of Adelaide and his colleagues wrote in a poster presentation.

The ENESTop study is a single-arm, phase II study. Patients eligible for the study started treatment with imatinib when they were first diagnosed with CML, then switched to nilotinib for at least 2 years with the combined time on the drugs of at least 3 years and small amounts of leukemia cells remaining after the nilotinib treatment.

For the consolidation phase of the study, patients continued their nilotinib therapy for 1 year. Patients without confirmed loss of MR4.5 after 1 year were eligible to stop nilotinib. RQ-PCR (reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction) was monitored every 12 weeks in the consolidation phase of the study and every 4 weeks during first 48 weeks of treatment-free remission. Nilotinib was restarted if patients had confirmed loss of deep molecular response (MR4 [consecutive BCR-ABL1IS greater than 0.01%]) or loss of major molecular response ([MMR] BCR-ABL1IS greater than 0.1%).

Of the 163 patients in the consolidation phase of the study, 126 entered treatment-free remission. Their median duration of tyrosine kinase inhibitor use prior to treatment-free remission was nearly 88 months, with a 53-month median duration of nilotinib therapy. At data cut-off, with median follow up of 50 weeks, 58% of the 126 patients were still in treatment-free remission at 48 weeks.

During treatment-free remission, 18 patients had confirmed loss of MR4 and 34 lost MMR. One patient had atypical transcript and came off the study. All but one of the 52 patients reinitiated nilotinib; 50 (98%) regained at least MMR by data cut-off, 48 (94%) regained MR4, and 47 (92%) regained MR4.5. One patient switched to another tyrosine kinase inhibitor at 22 weeks after restarting therapy.

Of those who restarted therapy, the median time was 12 weeks to regain MR4 and was 13 weeks to regain MR4.5. No new safety findings were observed on treatment.

The study is sponsored by Novartis, the maker of nilotinib (Tasigna). Dr. Hughes receives research support and honoraria from, and is a consultant or advisor to Novartis as well as Ariad and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Treatment-free remission attempts are safe and are achievable in most patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in chronic phase, Timothy P. Hughes, MD, and his colleagues in the international ENESTop trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The conclusion is based on follow-up data on 126 patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response (MR4.5) after switching from imatinib (Gleevec) to nilotinib (Tasigna) and discontinued nilotinib. So far, these are the largest prospective treatment-free remission data set in a population of patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response after switching from imatinib to nilotinib, Dr. Hughes, head of hematology at the University of Adelaide and his colleagues wrote in a poster presentation.

The ENESTop study is a single-arm, phase II study. Patients eligible for the study started treatment with imatinib when they were first diagnosed with CML, then switched to nilotinib for at least 2 years with the combined time on the drugs of at least 3 years and small amounts of leukemia cells remaining after the nilotinib treatment.

For the consolidation phase of the study, patients continued their nilotinib therapy for 1 year. Patients without confirmed loss of MR4.5 after 1 year were eligible to stop nilotinib. RQ-PCR (reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction) was monitored every 12 weeks in the consolidation phase of the study and every 4 weeks during first 48 weeks of treatment-free remission. Nilotinib was restarted if patients had confirmed loss of deep molecular response (MR4 [consecutive BCR-ABL1IS greater than 0.01%]) or loss of major molecular response ([MMR] BCR-ABL1IS greater than 0.1%).

Of the 163 patients in the consolidation phase of the study, 126 entered treatment-free remission. Their median duration of tyrosine kinase inhibitor use prior to treatment-free remission was nearly 88 months, with a 53-month median duration of nilotinib therapy. At data cut-off, with median follow up of 50 weeks, 58% of the 126 patients were still in treatment-free remission at 48 weeks.

During treatment-free remission, 18 patients had confirmed loss of MR4 and 34 lost MMR. One patient had atypical transcript and came off the study. All but one of the 52 patients reinitiated nilotinib; 50 (98%) regained at least MMR by data cut-off, 48 (94%) regained MR4, and 47 (92%) regained MR4.5. One patient switched to another tyrosine kinase inhibitor at 22 weeks after restarting therapy.

Of those who restarted therapy, the median time was 12 weeks to regain MR4 and was 13 weeks to regain MR4.5. No new safety findings were observed on treatment.

The study is sponsored by Novartis, the maker of nilotinib (Tasigna). Dr. Hughes receives research support and honoraria from, and is a consultant or advisor to Novartis as well as Ariad and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Treatment-free remission attempts are safe and are achievable in most patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in chronic phase, Timothy P. Hughes, MD, and his colleagues in the international ENESTop trial reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The conclusion is based on follow-up data on 126 patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response (MR4.5) after switching from imatinib (Gleevec) to nilotinib (Tasigna) and discontinued nilotinib. So far, these are the largest prospective treatment-free remission data set in a population of patients who achieved a sustained deep molecular response after switching from imatinib to nilotinib, Dr. Hughes, head of hematology at the University of Adelaide and his colleagues wrote in a poster presentation.

The ENESTop study is a single-arm, phase II study. Patients eligible for the study started treatment with imatinib when they were first diagnosed with CML, then switched to nilotinib for at least 2 years with the combined time on the drugs of at least 3 years and small amounts of leukemia cells remaining after the nilotinib treatment.

For the consolidation phase of the study, patients continued their nilotinib therapy for 1 year. Patients without confirmed loss of MR4.5 after 1 year were eligible to stop nilotinib. RQ-PCR (reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction) was monitored every 12 weeks in the consolidation phase of the study and every 4 weeks during first 48 weeks of treatment-free remission. Nilotinib was restarted if patients had confirmed loss of deep molecular response (MR4 [consecutive BCR-ABL1IS greater than 0.01%]) or loss of major molecular response ([MMR] BCR-ABL1IS greater than 0.1%).

Of the 163 patients in the consolidation phase of the study, 126 entered treatment-free remission. Their median duration of tyrosine kinase inhibitor use prior to treatment-free remission was nearly 88 months, with a 53-month median duration of nilotinib therapy. At data cut-off, with median follow up of 50 weeks, 58% of the 126 patients were still in treatment-free remission at 48 weeks.

During treatment-free remission, 18 patients had confirmed loss of MR4 and 34 lost MMR. One patient had atypical transcript and came off the study. All but one of the 52 patients reinitiated nilotinib; 50 (98%) regained at least MMR by data cut-off, 48 (94%) regained MR4, and 47 (92%) regained MR4.5. One patient switched to another tyrosine kinase inhibitor at 22 weeks after restarting therapy.

Of those who restarted therapy, the median time was 12 weeks to regain MR4 and was 13 weeks to regain MR4.5. No new safety findings were observed on treatment.

The study is sponsored by Novartis, the maker of nilotinib (Tasigna). Dr. Hughes receives research support and honoraria from, and is a consultant or advisor to Novartis as well as Ariad and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Treatment-free remission attempts are safe and are achievable in most patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase.

Major finding: At data cut-off, with median follow-up of 50 weeks, 58% of the 126 patients who entered the treatment-free stage of the study were still in treatment-free remission at 48 weeks.

Data source: The ENESTop study is a single-arm, phase II study that included 163 patients.

Disclosures: The study is sponsored by Novartis, the maker of nilotinib (Tasigna). Dr. Hughes receives research support and honoraria from, and is a consultant or advisor to Novartis as well as Ariad and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Cancer cell lines predict drug response, study shows

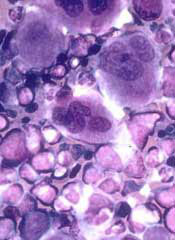

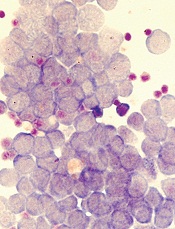

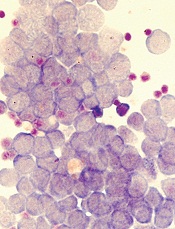

Image from PNAS

A study published in Cell has shown that patient-derived cancer cell lines harbor most of the same genetic changes found in patients’ tumors and could therefore be used to learn how cancers are likely to respond to new drugs.

Researchers believe this discovery could help advance personalized cancer medicine by leading to results that help doctors predict the best available drugs or the most suitable clinical trials for each individual patient.

“We need better ways to figure out which groups of patients are more likely to respond to a new drug before we run complex and expensive clinical trials,” said study author Ultan McDermott, MD, PhD, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“Our research shows that cancer cell lines do capture the molecular alterations found in tumors and so can be predictive of how a tumor will respond to a drug. This means the cell lines could tell us much more about how a tumor is likely to respond to a new drug before we try to test it in patients. We hope this information will ultimately help in the design of clinical trials that target those patients with the greatest likelihood of benefiting from treatment.”

The researchers said this is the first systematic, large-scale study to combine molecular data from patients, cancer cell lines, and drug sensitivity.

For the study, the team looked at genetic mutations known to cause cancer in more than 11,000 patient samples of 29 different cancer types, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

The researchers built a catalogue of the genetic changes that cause cancer in patients and mapped these alterations onto 1000 cancer cell lines. Next, they tested the cell lines for sensitivity to 265 different cancer drugs to understand which of these changes affect sensitivity.

This revealed that the majority of molecular abnormalities found in patients’ cancers are also found in cancer cells in the laboratory.

The work also showed that many of the molecular abnormalities detected in the thousands of patient samples can, both individually and in combination, have a strong effect on whether a particular drug affects a cancer cell’s survival.

The results suggest cancer cell lines could be better exploited to learn which drugs offer the most effective treatment to which patients.

“If a cell line has the same genetic features as a patient’s tumor, and that cell line responded to a specific drug, we can focus new research on this finding,” said study author Francesco Iorio, PhD, of the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This could ultimately help assign cancer patients into more precise groups based on how likely they are to respond to therapy. This resource can really help cancer research. Most importantly, it can be used to create tools for doctors to select a clinical trial which is most promising for their cancer patient. That is still a way off, but we are heading in the right direction.” ![]()

Image from PNAS

A study published in Cell has shown that patient-derived cancer cell lines harbor most of the same genetic changes found in patients’ tumors and could therefore be used to learn how cancers are likely to respond to new drugs.

Researchers believe this discovery could help advance personalized cancer medicine by leading to results that help doctors predict the best available drugs or the most suitable clinical trials for each individual patient.

“We need better ways to figure out which groups of patients are more likely to respond to a new drug before we run complex and expensive clinical trials,” said study author Ultan McDermott, MD, PhD, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“Our research shows that cancer cell lines do capture the molecular alterations found in tumors and so can be predictive of how a tumor will respond to a drug. This means the cell lines could tell us much more about how a tumor is likely to respond to a new drug before we try to test it in patients. We hope this information will ultimately help in the design of clinical trials that target those patients with the greatest likelihood of benefiting from treatment.”

The researchers said this is the first systematic, large-scale study to combine molecular data from patients, cancer cell lines, and drug sensitivity.

For the study, the team looked at genetic mutations known to cause cancer in more than 11,000 patient samples of 29 different cancer types, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

The researchers built a catalogue of the genetic changes that cause cancer in patients and mapped these alterations onto 1000 cancer cell lines. Next, they tested the cell lines for sensitivity to 265 different cancer drugs to understand which of these changes affect sensitivity.

This revealed that the majority of molecular abnormalities found in patients’ cancers are also found in cancer cells in the laboratory.

The work also showed that many of the molecular abnormalities detected in the thousands of patient samples can, both individually and in combination, have a strong effect on whether a particular drug affects a cancer cell’s survival.

The results suggest cancer cell lines could be better exploited to learn which drugs offer the most effective treatment to which patients.

“If a cell line has the same genetic features as a patient’s tumor, and that cell line responded to a specific drug, we can focus new research on this finding,” said study author Francesco Iorio, PhD, of the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This could ultimately help assign cancer patients into more precise groups based on how likely they are to respond to therapy. This resource can really help cancer research. Most importantly, it can be used to create tools for doctors to select a clinical trial which is most promising for their cancer patient. That is still a way off, but we are heading in the right direction.” ![]()

Image from PNAS

A study published in Cell has shown that patient-derived cancer cell lines harbor most of the same genetic changes found in patients’ tumors and could therefore be used to learn how cancers are likely to respond to new drugs.

Researchers believe this discovery could help advance personalized cancer medicine by leading to results that help doctors predict the best available drugs or the most suitable clinical trials for each individual patient.

“We need better ways to figure out which groups of patients are more likely to respond to a new drug before we run complex and expensive clinical trials,” said study author Ultan McDermott, MD, PhD, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“Our research shows that cancer cell lines do capture the molecular alterations found in tumors and so can be predictive of how a tumor will respond to a drug. This means the cell lines could tell us much more about how a tumor is likely to respond to a new drug before we try to test it in patients. We hope this information will ultimately help in the design of clinical trials that target those patients with the greatest likelihood of benefiting from treatment.”

The researchers said this is the first systematic, large-scale study to combine molecular data from patients, cancer cell lines, and drug sensitivity.

For the study, the team looked at genetic mutations known to cause cancer in more than 11,000 patient samples of 29 different cancer types, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

The researchers built a catalogue of the genetic changes that cause cancer in patients and mapped these alterations onto 1000 cancer cell lines. Next, they tested the cell lines for sensitivity to 265 different cancer drugs to understand which of these changes affect sensitivity.

This revealed that the majority of molecular abnormalities found in patients’ cancers are also found in cancer cells in the laboratory.

The work also showed that many of the molecular abnormalities detected in the thousands of patient samples can, both individually and in combination, have a strong effect on whether a particular drug affects a cancer cell’s survival.

The results suggest cancer cell lines could be better exploited to learn which drugs offer the most effective treatment to which patients.

“If a cell line has the same genetic features as a patient’s tumor, and that cell line responded to a specific drug, we can focus new research on this finding,” said study author Francesco Iorio, PhD, of the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This could ultimately help assign cancer patients into more precise groups based on how likely they are to respond to therapy. This resource can really help cancer research. Most importantly, it can be used to create tools for doctors to select a clinical trial which is most promising for their cancer patient. That is still a way off, but we are heading in the right direction.” ![]()

NICE recommends approval for bosutinib

Photo courtesy of CDC

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final draft guidance recommending approval for bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

NICE is recommending that bosutinib be made available through normal National Health Service (NHS) funding channels so patients don’t have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain it.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib.

“People with this type of chronic myeloid leukemia, who haven’t responded to first- and second-line treatment or who experience severe side effects, have few or no treatment options left,” said Carole Longson, director of the Centre for Health Technology Evaluation at NICE.

“New patients who need this drug can be reassured that bosutinib should be made available for routine use within the NHS.”

The current list price of bosutinib is £45,000 per patient per year. However, the NHS has been offered a discount by Pfizer, the drug’s manufacturer.

NICE previously looked at bosutinib in 2013 but did not recommend the drug for use on the NHS at that time, saying the drug was not cost-effective. Bosutinib was then made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

“The company positively engaged with our CDF reconsideration process and demonstrated that their drug can be cost-effective, which resulted in a positive recommendation,” Longson said. “This decision, when implemented, frees up funding in the CDF, which can be spent on other new and innovative cancer treatments.”

NICE’s final draft guidance is now with consultees who have the opportunity to appeal against the decision or notify NICE of any factual errors. The appeal period will close at 5 pm on July 21, 2016.

Until the final decision is published, bosutinib will still be available to new and existing patients through the old CDF. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final draft guidance recommending approval for bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

NICE is recommending that bosutinib be made available through normal National Health Service (NHS) funding channels so patients don’t have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain it.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib.

“People with this type of chronic myeloid leukemia, who haven’t responded to first- and second-line treatment or who experience severe side effects, have few or no treatment options left,” said Carole Longson, director of the Centre for Health Technology Evaluation at NICE.

“New patients who need this drug can be reassured that bosutinib should be made available for routine use within the NHS.”

The current list price of bosutinib is £45,000 per patient per year. However, the NHS has been offered a discount by Pfizer, the drug’s manufacturer.

NICE previously looked at bosutinib in 2013 but did not recommend the drug for use on the NHS at that time, saying the drug was not cost-effective. Bosutinib was then made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

“The company positively engaged with our CDF reconsideration process and demonstrated that their drug can be cost-effective, which resulted in a positive recommendation,” Longson said. “This decision, when implemented, frees up funding in the CDF, which can be spent on other new and innovative cancer treatments.”

NICE’s final draft guidance is now with consultees who have the opportunity to appeal against the decision or notify NICE of any factual errors. The appeal period will close at 5 pm on July 21, 2016.

Until the final decision is published, bosutinib will still be available to new and existing patients through the old CDF. ![]()

Photo courtesy of CDC

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a final draft guidance recommending approval for bosutinib (Bosulif), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

NICE is recommending that bosutinib be made available through normal National Health Service (NHS) funding channels so patients don’t have to apply to the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) to obtain it.

The CDF is money the government sets aside to pay for cancer drugs that haven’t been approved by NICE and aren’t available within the NHS in England.

Following the decision to reform the CDF earlier this year, NICE began to reappraise all drugs currently in the CDF in April. Bosutinib is the first drug to be looked at through this reconsideration process.

Bosutinib has conditional approval from the European Commission to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase, but only if those patients have previously received one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are not considered eligible for treatment with imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib.

“People with this type of chronic myeloid leukemia, who haven’t responded to first- and second-line treatment or who experience severe side effects, have few or no treatment options left,” said Carole Longson, director of the Centre for Health Technology Evaluation at NICE.

“New patients who need this drug can be reassured that bosutinib should be made available for routine use within the NHS.”

The current list price of bosutinib is £45,000 per patient per year. However, the NHS has been offered a discount by Pfizer, the drug’s manufacturer.

NICE previously looked at bosutinib in 2013 but did not recommend the drug for use on the NHS at that time, saying the drug was not cost-effective. Bosutinib was then made available to patients via the CDF.

As part of the reappraisal process, Pfizer offered a discount for bosutinib. Taking this discount into consideration, as well as the limited treatment options for CML patients, NICE decided bosutinib is cost-effective.

“The company positively engaged with our CDF reconsideration process and demonstrated that their drug can be cost-effective, which resulted in a positive recommendation,” Longson said. “This decision, when implemented, frees up funding in the CDF, which can be spent on other new and innovative cancer treatments.”

NICE’s final draft guidance is now with consultees who have the opportunity to appeal against the decision or notify NICE of any factual errors. The appeal period will close at 5 pm on July 21, 2016.

Until the final decision is published, bosutinib will still be available to new and existing patients through the old CDF.

Drugs produce comparable results in CP-CML

Long-term results from the DASISION trial suggest that dasatinib and imatinib produce similar outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CP-CML).

Although patients who received dasatinib experienced faster and deeper molecular responses than patients who received imatinib, the overall survival and progression-free survival rates were similar between the treatment arms.

Overall, adverse events (AEs) were similar between the arms as well.

Researchers said these results suggest that dasatinib should continue to be considered an option for patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML.

The team reported the results of this study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The research was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The trial enrolled 519 patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML. They were randomized to receive dasatinib at 100 mg once daily (n=259) or imatinib at 400 mg once daily (n=260). Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the arms.

At 5 years of follow-up, 61% of patients in the dasatinib arm and 63% of patients in the imatinib arm remained on treatment.

Response and survival

The cumulative 5-year rate of major molecular response was 76% in the dasatinib arm and 64% in the imatinib arm (P=0.0022). The rates of MR4.5 were 42% and 33%, respectively (P=0.0251).

The estimated 5-year overall survival was 91% in the dasatinib arm and 90% in the imatinib arm (hazard ratio=1.01; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.73).

The estimated 5-year progression-free survival was 85% and 86%, respectively (hazard ratio=1.06; 95% CI, 0.68 to 1.66).

Safety

In both treatment arms, most AEs were grade 1 or 2. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 15% of patients in the dasatinib arm and 11% of patients in the imatinib arm.

Rates of grade 3/4 hematologic AEs tended to be higher in the dasatinib arm than the imatinib arm.

But the rates of most drug-related, nonhematologic AEs were lower in the dasatinib arm than the imatinib arm or were comparable between the arms.

The exception was drug-related pleural effusion, which was more common with dasatinib (28%) than with imatinib (0.8%).

Drug-related AEs were largely manageable, although they led to treatment discontinuation in 16% of dasatinib-treated patients and 7% of imatinib-treated patients.

By 5 years, 26 patients (10%) in each treatment arm had died. Nine patients in the dasatinib arm died of disease progression, as did 17 patients in the imatinib arm.

Long-term results from the DASISION trial suggest that dasatinib and imatinib produce similar outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CP-CML).

Although patients who received dasatinib experienced faster and deeper molecular responses than patients who received imatinib, the overall survival and progression-free survival rates were similar between the treatment arms.

Overall, adverse events (AEs) were similar between the arms as well.

Researchers said these results suggest that dasatinib should continue to be considered an option for patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML.

The team reported the results of this study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The research was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The trial enrolled 519 patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML. They were randomized to receive dasatinib at 100 mg once daily (n=259) or imatinib at 400 mg once daily (n=260). Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the arms.

At 5 years of follow-up, 61% of patients in the dasatinib arm and 63% of patients in the imatinib arm remained on treatment.

Response and survival

The cumulative 5-year rate of major molecular response was 76% in the dasatinib arm and 64% in the imatinib arm (P=0.0022). The rates of MR4.5 were 42% and 33%, respectively (P=0.0251).

The estimated 5-year overall survival was 91% in the dasatinib arm and 90% in the imatinib arm (hazard ratio=1.01; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.73).

The estimated 5-year progression-free survival was 85% and 86%, respectively (hazard ratio=1.06; 95% CI, 0.68 to 1.66).

Safety

In both treatment arms, most AEs were grade 1 or 2. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 15% of patients in the dasatinib arm and 11% of patients in the imatinib arm.

Rates of grade 3/4 hematologic AEs tended to be higher in the dasatinib arm than the imatinib arm.

But the rates of most drug-related, nonhematologic AEs were lower in the dasatinib arm than the imatinib arm or were comparable between the arms.

The exception was drug-related pleural effusion, which was more common with dasatinib (28%) than with imatinib (0.8%).

Drug-related AEs were largely manageable, although they led to treatment discontinuation in 16% of dasatinib-treated patients and 7% of imatinib-treated patients.

By 5 years, 26 patients (10%) in each treatment arm had died. Nine patients in the dasatinib arm died of disease progression, as did 17 patients in the imatinib arm.

Long-term results from the DASISION trial suggest that dasatinib and imatinib produce similar outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CP-CML).

Although patients who received dasatinib experienced faster and deeper molecular responses than patients who received imatinib, the overall survival and progression-free survival rates were similar between the treatment arms.

Overall, adverse events (AEs) were similar between the arms as well.

Researchers said these results suggest that dasatinib should continue to be considered an option for patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML.

The team reported the results of this study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The research was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The trial enrolled 519 patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML. They were randomized to receive dasatinib at 100 mg once daily (n=259) or imatinib at 400 mg once daily (n=260). Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the arms.

At 5 years of follow-up, 61% of patients in the dasatinib arm and 63% of patients in the imatinib arm remained on treatment.

Response and survival

The cumulative 5-year rate of major molecular response was 76% in the dasatinib arm and 64% in the imatinib arm (P=0.0022). The rates of MR4.5 were 42% and 33%, respectively (P=0.0251).

The estimated 5-year overall survival was 91% in the dasatinib arm and 90% in the imatinib arm (hazard ratio=1.01; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.73).

The estimated 5-year progression-free survival was 85% and 86%, respectively (hazard ratio=1.06; 95% CI, 0.68 to 1.66).

Safety

In both treatment arms, most AEs were grade 1 or 2. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 15% of patients in the dasatinib arm and 11% of patients in the imatinib arm.

Rates of grade 3/4 hematologic AEs tended to be higher in the dasatinib arm than the imatinib arm.

But the rates of most drug-related, nonhematologic AEs were lower in the dasatinib arm than the imatinib arm or were comparable between the arms.

The exception was drug-related pleural effusion, which was more common with dasatinib (28%) than with imatinib (0.8%).

Drug-related AEs were largely manageable, although they led to treatment discontinuation in 16% of dasatinib-treated patients and 7% of imatinib-treated patients.

By 5 years, 26 patients (10%) in each treatment arm had died. Nine patients in the dasatinib arm died of disease progression, as did 17 patients in the imatinib arm.