User login

Studies address ibrutinib bleeding risk in patients with CLL receiving Mohs surgery

Patients receiving , new research shows.

“Our cohort of CLL patients on ibrutinib had a two-times greater risk of bleeding complications relative to those on anticoagulants and a nearly 40-times greater risk of bleeding complications relative to those patients on no anticoagulants or CLL therapy,” Kelsey E. Hirotsu, MD, first author of one of two studies on the issue presented at the American College of Mohs Surgery annual meeting, told this news organization.

“It was definitely surprising to see this doubled risk with ibrutinib relative to anticoagulants, and certainly highlights the clinically relevant increased bleeding risk in patients on ibrutinib,” said Dr. Hirotsu, a Mohs micrographic surgery fellow in the department of dermatology, University of California, San Diego (UCSD).

With CLL associated with an increased risk for aggressive skin cancers, particularly squamous cell carcinoma, Mohs surgeons may commonly find themselves treating patients with these unique considerations. Surgical treatment of those cancers can be complicated not only because of potential underlying thrombocytopenia, which occurs in about 5% of untreated CLL patients, but also because of the increased risk for bleeding that is associated with the use of the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib, commonly used for CLL.

While the nature of the increased bleeding-related complications among patients with CLL undergoing Mohs surgery has been documented in some case reports, evidence from larger studies has been lacking.

In one of the studies presented at the ACMS meeting, Dr. Hirotsu and her colleagues evaluated data on patients with CLL who underwent at least one Mohs surgery procedure at UCSD Dermatologic Surgery over 10 years. Of the 362 Mohs cases among 98 patients with CLL, 32 cases had at least one complication. Patients on anticoagulants, including antiplatelet agents, Coumadin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), not surprisingly, had higher rates of complications, particularly bleeding.

However, those treated with ibrutinib had the highest rates of complications among all of the patients (40.6%), with all of their complications involving bleeding-related events. In comparison, the complication rates, for instance, of patients treated with antiplatelets were 21.9%; Coumadin, 6.2%; and DOACs, 15.6%.

The incidence of bleeding-related complications among the cases in the ibrutinib-treated patients was 30.2% compared with 13.2% among those on blood thinners and no CLL therapy (relative risk [RR], 2.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.85-5.11; P = .11). “Although not statistically significant, these results could trend toward significance with larger sample sizes,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

The risk for bleeding among patients on ibrutinib compared with patients on no medications, however, was significant, with a relative risk of 39.0 (95% CI, 2.35-646; P = .011).

Of note, among 12 patients on ibrutinib who experienced bleeding complications, 7 had previously undergone Mohs surgeries when they were not taking ibrutinib and no bleeding complications had occurred in those procedures. “This may further implicate ibrutinib as a cause of the bleeding-related complications,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

In investigating the role of thrombocytopenia at the time of Mohs surgery, the authors found that, among ibrutinib-treated patients who had no complications, 30% had thrombocytopenia, compared with 70% of those who did have bleeding while on ibrutinib at the time of surgery.

“It was interesting that thrombocytopenia is more common in ibrutinib patients with bleeding-related complications, but further research needs to be done to determine the clinical relevance and possible management implications,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

In a separate study presented at the meeting, 37 patients treated with ibrutinib for CLL while undergoing cutaneous surgery that included Mohs surgery and excisions had a significantly increased bleeding complication rate compared with a control group of 64 age- and sex-matched patients with CLL undergoing cutaneous surgery: 6 of 75 procedures (8%) versus 1 of 115 procedures (0.9%; P = .02).

Those with bleeding complications while on ibrutinib were all male, older (mean age, 82.7 vs. 73.0; P = .01), and had lower mean platelet counts (104 K/mcL vs. 150.5 K/mcL; P = .03).

There were no significant differences between the case and control groups in terms of anatomic site, type of procedure (Mohs versus excision), tumor diagnosis, lesion size, or type of reconstruction, while the control group was more likely to be on aspirin or other anticoagulants (P < .0001).

In an interview, senior author Nahid Y. Vidal, MD, a Mohs surgeon and dermatologic oncologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that “the take-home message is that patients on ibrutinib should be considered higher risk for bleeding events, regardless of whether they are having a simpler surgery [excision] or more involved skin surgery procedure [Mohs with flap].”

Holding treatment

To offset the bleeding risk, Dr. Vidal notes that holding the treatment is considered safe and that the manufacturer recommends holding ibrutinib for at least 3-7 days pre- and post surgery, “depending on type of surgery and risk of bleeding.”

“In our institution, with the hematologist/oncologist’s input, we hold ibrutinib for 5 days preop and 3 days post op, and have not had bleed complications in these patients,” she said, noting that there were no bleeding events in the patients in the study when ibrutinib was held.

Likewise, Dr. Hirotsu noted that at her center at UCSD, patients on ibrutinib are asked during the preop call to hold treatment for 3 days before and after Mohs surgery – but are advised to discuss the decision with their hematologist/oncologist for approval.

The measure isn’t always successful in preventing bleeding, however, as seen in a case study describing two patients who experienced bleeding complications following Mohs surgery despite being taken off ibrutinib 3 days prior to the procedure.

The senior author of that study, Kira Minkis, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, Weill Cornell/New York Presbyterian, New York, told this news organization that her team concluded that in those cases ibrutinib perhaps should have been held longer than 3 days.

“In some cases, especially if the Mohs surgery is a large procedure with a more advanced reconstruction, such as a large flap, it might be more prudent to continue it longer than 3 days,” Dr. Minkis said. She noted that the high bleeding risk observed in the studies at ACMS was notable – but not unexpected.

“I’m not that surprised because if you look at the hematologic literature, the risk is indeed pretty significant, so it makes sense that it would also occur with Mohs surgeries,” she said.

She underscored that a 3-day hold of ibrutinib should be considered the minimum, “and in some cases, it should be held up to 7 days prior to surgery, depending on the specific surgery,” with the important caveat of consulting with the patient’s hematology team.

“Multidisciplinary decision-making is necessary for these cases, and the interruption of therapy should always be discussed with their hematology team,” she added. That said, Dr. Minkis noted that “I’ve never had a hematologist who had any concerns for withholding ibrutinib even for a week around the time of a surgery.”

Dr. Hirotsu, Dr. Vidal, and Dr. Minkis reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients receiving , new research shows.

“Our cohort of CLL patients on ibrutinib had a two-times greater risk of bleeding complications relative to those on anticoagulants and a nearly 40-times greater risk of bleeding complications relative to those patients on no anticoagulants or CLL therapy,” Kelsey E. Hirotsu, MD, first author of one of two studies on the issue presented at the American College of Mohs Surgery annual meeting, told this news organization.

“It was definitely surprising to see this doubled risk with ibrutinib relative to anticoagulants, and certainly highlights the clinically relevant increased bleeding risk in patients on ibrutinib,” said Dr. Hirotsu, a Mohs micrographic surgery fellow in the department of dermatology, University of California, San Diego (UCSD).

With CLL associated with an increased risk for aggressive skin cancers, particularly squamous cell carcinoma, Mohs surgeons may commonly find themselves treating patients with these unique considerations. Surgical treatment of those cancers can be complicated not only because of potential underlying thrombocytopenia, which occurs in about 5% of untreated CLL patients, but also because of the increased risk for bleeding that is associated with the use of the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib, commonly used for CLL.

While the nature of the increased bleeding-related complications among patients with CLL undergoing Mohs surgery has been documented in some case reports, evidence from larger studies has been lacking.

In one of the studies presented at the ACMS meeting, Dr. Hirotsu and her colleagues evaluated data on patients with CLL who underwent at least one Mohs surgery procedure at UCSD Dermatologic Surgery over 10 years. Of the 362 Mohs cases among 98 patients with CLL, 32 cases had at least one complication. Patients on anticoagulants, including antiplatelet agents, Coumadin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), not surprisingly, had higher rates of complications, particularly bleeding.

However, those treated with ibrutinib had the highest rates of complications among all of the patients (40.6%), with all of their complications involving bleeding-related events. In comparison, the complication rates, for instance, of patients treated with antiplatelets were 21.9%; Coumadin, 6.2%; and DOACs, 15.6%.

The incidence of bleeding-related complications among the cases in the ibrutinib-treated patients was 30.2% compared with 13.2% among those on blood thinners and no CLL therapy (relative risk [RR], 2.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.85-5.11; P = .11). “Although not statistically significant, these results could trend toward significance with larger sample sizes,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

The risk for bleeding among patients on ibrutinib compared with patients on no medications, however, was significant, with a relative risk of 39.0 (95% CI, 2.35-646; P = .011).

Of note, among 12 patients on ibrutinib who experienced bleeding complications, 7 had previously undergone Mohs surgeries when they were not taking ibrutinib and no bleeding complications had occurred in those procedures. “This may further implicate ibrutinib as a cause of the bleeding-related complications,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

In investigating the role of thrombocytopenia at the time of Mohs surgery, the authors found that, among ibrutinib-treated patients who had no complications, 30% had thrombocytopenia, compared with 70% of those who did have bleeding while on ibrutinib at the time of surgery.

“It was interesting that thrombocytopenia is more common in ibrutinib patients with bleeding-related complications, but further research needs to be done to determine the clinical relevance and possible management implications,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

In a separate study presented at the meeting, 37 patients treated with ibrutinib for CLL while undergoing cutaneous surgery that included Mohs surgery and excisions had a significantly increased bleeding complication rate compared with a control group of 64 age- and sex-matched patients with CLL undergoing cutaneous surgery: 6 of 75 procedures (8%) versus 1 of 115 procedures (0.9%; P = .02).

Those with bleeding complications while on ibrutinib were all male, older (mean age, 82.7 vs. 73.0; P = .01), and had lower mean platelet counts (104 K/mcL vs. 150.5 K/mcL; P = .03).

There were no significant differences between the case and control groups in terms of anatomic site, type of procedure (Mohs versus excision), tumor diagnosis, lesion size, or type of reconstruction, while the control group was more likely to be on aspirin or other anticoagulants (P < .0001).

In an interview, senior author Nahid Y. Vidal, MD, a Mohs surgeon and dermatologic oncologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that “the take-home message is that patients on ibrutinib should be considered higher risk for bleeding events, regardless of whether they are having a simpler surgery [excision] or more involved skin surgery procedure [Mohs with flap].”

Holding treatment

To offset the bleeding risk, Dr. Vidal notes that holding the treatment is considered safe and that the manufacturer recommends holding ibrutinib for at least 3-7 days pre- and post surgery, “depending on type of surgery and risk of bleeding.”

“In our institution, with the hematologist/oncologist’s input, we hold ibrutinib for 5 days preop and 3 days post op, and have not had bleed complications in these patients,” she said, noting that there were no bleeding events in the patients in the study when ibrutinib was held.

Likewise, Dr. Hirotsu noted that at her center at UCSD, patients on ibrutinib are asked during the preop call to hold treatment for 3 days before and after Mohs surgery – but are advised to discuss the decision with their hematologist/oncologist for approval.

The measure isn’t always successful in preventing bleeding, however, as seen in a case study describing two patients who experienced bleeding complications following Mohs surgery despite being taken off ibrutinib 3 days prior to the procedure.

The senior author of that study, Kira Minkis, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, Weill Cornell/New York Presbyterian, New York, told this news organization that her team concluded that in those cases ibrutinib perhaps should have been held longer than 3 days.

“In some cases, especially if the Mohs surgery is a large procedure with a more advanced reconstruction, such as a large flap, it might be more prudent to continue it longer than 3 days,” Dr. Minkis said. She noted that the high bleeding risk observed in the studies at ACMS was notable – but not unexpected.

“I’m not that surprised because if you look at the hematologic literature, the risk is indeed pretty significant, so it makes sense that it would also occur with Mohs surgeries,” she said.

She underscored that a 3-day hold of ibrutinib should be considered the minimum, “and in some cases, it should be held up to 7 days prior to surgery, depending on the specific surgery,” with the important caveat of consulting with the patient’s hematology team.

“Multidisciplinary decision-making is necessary for these cases, and the interruption of therapy should always be discussed with their hematology team,” she added. That said, Dr. Minkis noted that “I’ve never had a hematologist who had any concerns for withholding ibrutinib even for a week around the time of a surgery.”

Dr. Hirotsu, Dr. Vidal, and Dr. Minkis reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients receiving , new research shows.

“Our cohort of CLL patients on ibrutinib had a two-times greater risk of bleeding complications relative to those on anticoagulants and a nearly 40-times greater risk of bleeding complications relative to those patients on no anticoagulants or CLL therapy,” Kelsey E. Hirotsu, MD, first author of one of two studies on the issue presented at the American College of Mohs Surgery annual meeting, told this news organization.

“It was definitely surprising to see this doubled risk with ibrutinib relative to anticoagulants, and certainly highlights the clinically relevant increased bleeding risk in patients on ibrutinib,” said Dr. Hirotsu, a Mohs micrographic surgery fellow in the department of dermatology, University of California, San Diego (UCSD).

With CLL associated with an increased risk for aggressive skin cancers, particularly squamous cell carcinoma, Mohs surgeons may commonly find themselves treating patients with these unique considerations. Surgical treatment of those cancers can be complicated not only because of potential underlying thrombocytopenia, which occurs in about 5% of untreated CLL patients, but also because of the increased risk for bleeding that is associated with the use of the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib, commonly used for CLL.

While the nature of the increased bleeding-related complications among patients with CLL undergoing Mohs surgery has been documented in some case reports, evidence from larger studies has been lacking.

In one of the studies presented at the ACMS meeting, Dr. Hirotsu and her colleagues evaluated data on patients with CLL who underwent at least one Mohs surgery procedure at UCSD Dermatologic Surgery over 10 years. Of the 362 Mohs cases among 98 patients with CLL, 32 cases had at least one complication. Patients on anticoagulants, including antiplatelet agents, Coumadin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), not surprisingly, had higher rates of complications, particularly bleeding.

However, those treated with ibrutinib had the highest rates of complications among all of the patients (40.6%), with all of their complications involving bleeding-related events. In comparison, the complication rates, for instance, of patients treated with antiplatelets were 21.9%; Coumadin, 6.2%; and DOACs, 15.6%.

The incidence of bleeding-related complications among the cases in the ibrutinib-treated patients was 30.2% compared with 13.2% among those on blood thinners and no CLL therapy (relative risk [RR], 2.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.85-5.11; P = .11). “Although not statistically significant, these results could trend toward significance with larger sample sizes,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

The risk for bleeding among patients on ibrutinib compared with patients on no medications, however, was significant, with a relative risk of 39.0 (95% CI, 2.35-646; P = .011).

Of note, among 12 patients on ibrutinib who experienced bleeding complications, 7 had previously undergone Mohs surgeries when they were not taking ibrutinib and no bleeding complications had occurred in those procedures. “This may further implicate ibrutinib as a cause of the bleeding-related complications,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

In investigating the role of thrombocytopenia at the time of Mohs surgery, the authors found that, among ibrutinib-treated patients who had no complications, 30% had thrombocytopenia, compared with 70% of those who did have bleeding while on ibrutinib at the time of surgery.

“It was interesting that thrombocytopenia is more common in ibrutinib patients with bleeding-related complications, but further research needs to be done to determine the clinical relevance and possible management implications,” Dr. Hirotsu said.

In a separate study presented at the meeting, 37 patients treated with ibrutinib for CLL while undergoing cutaneous surgery that included Mohs surgery and excisions had a significantly increased bleeding complication rate compared with a control group of 64 age- and sex-matched patients with CLL undergoing cutaneous surgery: 6 of 75 procedures (8%) versus 1 of 115 procedures (0.9%; P = .02).

Those with bleeding complications while on ibrutinib were all male, older (mean age, 82.7 vs. 73.0; P = .01), and had lower mean platelet counts (104 K/mcL vs. 150.5 K/mcL; P = .03).

There were no significant differences between the case and control groups in terms of anatomic site, type of procedure (Mohs versus excision), tumor diagnosis, lesion size, or type of reconstruction, while the control group was more likely to be on aspirin or other anticoagulants (P < .0001).

In an interview, senior author Nahid Y. Vidal, MD, a Mohs surgeon and dermatologic oncologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that “the take-home message is that patients on ibrutinib should be considered higher risk for bleeding events, regardless of whether they are having a simpler surgery [excision] or more involved skin surgery procedure [Mohs with flap].”

Holding treatment

To offset the bleeding risk, Dr. Vidal notes that holding the treatment is considered safe and that the manufacturer recommends holding ibrutinib for at least 3-7 days pre- and post surgery, “depending on type of surgery and risk of bleeding.”

“In our institution, with the hematologist/oncologist’s input, we hold ibrutinib for 5 days preop and 3 days post op, and have not had bleed complications in these patients,” she said, noting that there were no bleeding events in the patients in the study when ibrutinib was held.

Likewise, Dr. Hirotsu noted that at her center at UCSD, patients on ibrutinib are asked during the preop call to hold treatment for 3 days before and after Mohs surgery – but are advised to discuss the decision with their hematologist/oncologist for approval.

The measure isn’t always successful in preventing bleeding, however, as seen in a case study describing two patients who experienced bleeding complications following Mohs surgery despite being taken off ibrutinib 3 days prior to the procedure.

The senior author of that study, Kira Minkis, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, Weill Cornell/New York Presbyterian, New York, told this news organization that her team concluded that in those cases ibrutinib perhaps should have been held longer than 3 days.

“In some cases, especially if the Mohs surgery is a large procedure with a more advanced reconstruction, such as a large flap, it might be more prudent to continue it longer than 3 days,” Dr. Minkis said. She noted that the high bleeding risk observed in the studies at ACMS was notable – but not unexpected.

“I’m not that surprised because if you look at the hematologic literature, the risk is indeed pretty significant, so it makes sense that it would also occur with Mohs surgeries,” she said.

She underscored that a 3-day hold of ibrutinib should be considered the minimum, “and in some cases, it should be held up to 7 days prior to surgery, depending on the specific surgery,” with the important caveat of consulting with the patient’s hematology team.

“Multidisciplinary decision-making is necessary for these cases, and the interruption of therapy should always be discussed with their hematology team,” she added. That said, Dr. Minkis noted that “I’ve never had a hematologist who had any concerns for withholding ibrutinib even for a week around the time of a surgery.”

Dr. Hirotsu, Dr. Vidal, and Dr. Minkis reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Phase-3 study: Leukemia patients live longer with ibrutinib

“This trial led to the first-line approval of ibrutinib for CLL patients,” lead author Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “It is important to follow these patients long-term to understand the expected duration of response/disease control and to monitor for late toxicity,” he said “The data are useful in guiding clinicians who treat CLL and patients being treated with single agent BTK inhibitors,” he noted.

In the initial RESONATE-2, a phase 3, open-label study, 269 adults aged 65 years and older who were previously untreated for CLL or small lymphocytic leukemia were randomized to ibrutinib or the standard of care, chlorambucil. Patients received 420 mg of ibrutinib once daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity (136 patients) or up to 12 cycles of 0.5-0.8 mg/kg of chlorambucil (133 patients).

The long-term outcome data were published in Blood Advances.

Overall, at a median of 83 months’ follow-up, progression-free survival was significantly higher for ibrutinib patients than for chlorambucil patients (hazard ratio 0.154).

At 7 years, progression-free survival was 59% in the ibrutinib group vs. 9% in the chlorambucil group.

Notably, progression-free survival benefits with ibrutinib also were higher for patients with high-risk genomic features, identified as del(11q) and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region gene (IGHV).

Complete data were available for 54 patients with del(11q) and 118 with unmutated IGHV. In this subset of patients, progression-free survival rates at 7 years were significantly higher for those treated with ibrutinib vs. chlorambucil who had del(11q) or unmutated IGHV (52% vs. 0% and 58% vs. 2%, respectively).

Approximately 42% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib remained on the therapy at up to 8 years, with a median follow-up of 7.4 years. Overall survival at 7 years was 78% for ibrutinib; overall survival data were not collected for chlorambucil for patients with progressive disease after the median of 5 years, as these patients were eligible to switch to ibrutinib in a long-term extension study or exit the study.

Adverse events prompted reduction of ibrutinib in 30 patients and dose holding for at least 7 days in 79 patients. However, dose modification resolved or improved the adverse events in 85% of the patients with held doses and 90% of those with reduced doses.

The overall prevalence of adverse events was similar to previous follow-up data at 5 years. No new safety signals were observed during the longer study period. The rate of treatment discontinuation because of adverse events was highest in the first year.

“We have been surprised at how long the remissions have lasted with ibrutinib,” said Dr. Barr. “Even with up to 8 years of follow-up, we have yet to reach the median progression free-survival,” he noted.

“These data, in combination with other data sets, highlight the impact that ibrutinib and other BTK inhibitors have had in treating CLL,” said Dr. Barr. “Patients are living longer and avoiding the side effects of chemotherapy in the era of novel agent use,” he said.

However, research gaps remain, Dr. Barr noted. “We need to continue following these patients over time given the length of the remissions. Additionally, we need to continue investigating novel combinations,” he said. Such studies will help us understand the benefit of fixed durations regimens compared to single agent BTK inhibitors,” he emphasized.

Safety and efficacy remain promising

“Ibrutinib was approved for the treatment of CLL, but only in the relapsed setting,” Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, said in an interview. “This trial was important because it led to the approval of ibrutinib in the front-line setting, making it the first, and at the time, only, small molecule that could be used upfront,” said Dr. O’Brien, who was not involved with the study.

“The initial results were certainly not surprising, as given the efficacy of ibrutinib in the relapsed setting, it seemed likely that it would produce a longer PFS than chlorambucil,” said Dr. O’Brien. “What may not have been expected though, is the incredible durability of these responses with ibrutinib,” she noted.

The clinical implications of the long-term data are that ibrutinib is producing “very durable remissions with continuous therapy,” Dr. O’Brien said. “There are no late safety signals and most side effects diminish with time. However, hypertension and atrial fibrillation continue to occur, so continued monitoring of blood pressure in these patients is important,” she emphasized.

Minor, but annoying, side effects are not infrequent early on with ibrutinib and may present a barrier to use for some patients, Dr. O’Brien said. “Some side effects may be overcome with temporary pauses of drug or dose reduction,” she noted. However, “it is important for patients to be aware that most of these side effects will completely abate with time,” she added.

“The main limitation of this trial was that the comparison was to a rather weak chemotherapy agent, albeit it one frequently used in older patients, particularly in Europe,” said Dr. O’Brien. “Nevertheless, two subsequent trials comparing ibrutinib (with or without rituximab) with either BR [bendamustine/rituximab] or FCR [fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab] showed a longer PFS with ibrutinib, as compared to that seen with either chemoimmunotherapy regimen,” she said.

The study was supported by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Dr. Barr collaborated with sponsor AbbVie on the study design, and disclosed relationships with companies including AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, MEI Pharma, Merck, Morphosys, Pharmacyclics LLC (an AbbVie company), Seattle Genetics, and TG Therapeutics. Dr. O’Brien had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

“This trial led to the first-line approval of ibrutinib for CLL patients,” lead author Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “It is important to follow these patients long-term to understand the expected duration of response/disease control and to monitor for late toxicity,” he said “The data are useful in guiding clinicians who treat CLL and patients being treated with single agent BTK inhibitors,” he noted.

In the initial RESONATE-2, a phase 3, open-label study, 269 adults aged 65 years and older who were previously untreated for CLL or small lymphocytic leukemia were randomized to ibrutinib or the standard of care, chlorambucil. Patients received 420 mg of ibrutinib once daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity (136 patients) or up to 12 cycles of 0.5-0.8 mg/kg of chlorambucil (133 patients).

The long-term outcome data were published in Blood Advances.

Overall, at a median of 83 months’ follow-up, progression-free survival was significantly higher for ibrutinib patients than for chlorambucil patients (hazard ratio 0.154).

At 7 years, progression-free survival was 59% in the ibrutinib group vs. 9% in the chlorambucil group.

Notably, progression-free survival benefits with ibrutinib also were higher for patients with high-risk genomic features, identified as del(11q) and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region gene (IGHV).

Complete data were available for 54 patients with del(11q) and 118 with unmutated IGHV. In this subset of patients, progression-free survival rates at 7 years were significantly higher for those treated with ibrutinib vs. chlorambucil who had del(11q) or unmutated IGHV (52% vs. 0% and 58% vs. 2%, respectively).

Approximately 42% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib remained on the therapy at up to 8 years, with a median follow-up of 7.4 years. Overall survival at 7 years was 78% for ibrutinib; overall survival data were not collected for chlorambucil for patients with progressive disease after the median of 5 years, as these patients were eligible to switch to ibrutinib in a long-term extension study or exit the study.

Adverse events prompted reduction of ibrutinib in 30 patients and dose holding for at least 7 days in 79 patients. However, dose modification resolved or improved the adverse events in 85% of the patients with held doses and 90% of those with reduced doses.

The overall prevalence of adverse events was similar to previous follow-up data at 5 years. No new safety signals were observed during the longer study period. The rate of treatment discontinuation because of adverse events was highest in the first year.

“We have been surprised at how long the remissions have lasted with ibrutinib,” said Dr. Barr. “Even with up to 8 years of follow-up, we have yet to reach the median progression free-survival,” he noted.

“These data, in combination with other data sets, highlight the impact that ibrutinib and other BTK inhibitors have had in treating CLL,” said Dr. Barr. “Patients are living longer and avoiding the side effects of chemotherapy in the era of novel agent use,” he said.

However, research gaps remain, Dr. Barr noted. “We need to continue following these patients over time given the length of the remissions. Additionally, we need to continue investigating novel combinations,” he said. Such studies will help us understand the benefit of fixed durations regimens compared to single agent BTK inhibitors,” he emphasized.

Safety and efficacy remain promising

“Ibrutinib was approved for the treatment of CLL, but only in the relapsed setting,” Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, said in an interview. “This trial was important because it led to the approval of ibrutinib in the front-line setting, making it the first, and at the time, only, small molecule that could be used upfront,” said Dr. O’Brien, who was not involved with the study.

“The initial results were certainly not surprising, as given the efficacy of ibrutinib in the relapsed setting, it seemed likely that it would produce a longer PFS than chlorambucil,” said Dr. O’Brien. “What may not have been expected though, is the incredible durability of these responses with ibrutinib,” she noted.

The clinical implications of the long-term data are that ibrutinib is producing “very durable remissions with continuous therapy,” Dr. O’Brien said. “There are no late safety signals and most side effects diminish with time. However, hypertension and atrial fibrillation continue to occur, so continued monitoring of blood pressure in these patients is important,” she emphasized.

Minor, but annoying, side effects are not infrequent early on with ibrutinib and may present a barrier to use for some patients, Dr. O’Brien said. “Some side effects may be overcome with temporary pauses of drug or dose reduction,” she noted. However, “it is important for patients to be aware that most of these side effects will completely abate with time,” she added.

“The main limitation of this trial was that the comparison was to a rather weak chemotherapy agent, albeit it one frequently used in older patients, particularly in Europe,” said Dr. O’Brien. “Nevertheless, two subsequent trials comparing ibrutinib (with or without rituximab) with either BR [bendamustine/rituximab] or FCR [fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab] showed a longer PFS with ibrutinib, as compared to that seen with either chemoimmunotherapy regimen,” she said.

The study was supported by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Dr. Barr collaborated with sponsor AbbVie on the study design, and disclosed relationships with companies including AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, MEI Pharma, Merck, Morphosys, Pharmacyclics LLC (an AbbVie company), Seattle Genetics, and TG Therapeutics. Dr. O’Brien had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

“This trial led to the first-line approval of ibrutinib for CLL patients,” lead author Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “It is important to follow these patients long-term to understand the expected duration of response/disease control and to monitor for late toxicity,” he said “The data are useful in guiding clinicians who treat CLL and patients being treated with single agent BTK inhibitors,” he noted.

In the initial RESONATE-2, a phase 3, open-label study, 269 adults aged 65 years and older who were previously untreated for CLL or small lymphocytic leukemia were randomized to ibrutinib or the standard of care, chlorambucil. Patients received 420 mg of ibrutinib once daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity (136 patients) or up to 12 cycles of 0.5-0.8 mg/kg of chlorambucil (133 patients).

The long-term outcome data were published in Blood Advances.

Overall, at a median of 83 months’ follow-up, progression-free survival was significantly higher for ibrutinib patients than for chlorambucil patients (hazard ratio 0.154).

At 7 years, progression-free survival was 59% in the ibrutinib group vs. 9% in the chlorambucil group.

Notably, progression-free survival benefits with ibrutinib also were higher for patients with high-risk genomic features, identified as del(11q) and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region gene (IGHV).

Complete data were available for 54 patients with del(11q) and 118 with unmutated IGHV. In this subset of patients, progression-free survival rates at 7 years were significantly higher for those treated with ibrutinib vs. chlorambucil who had del(11q) or unmutated IGHV (52% vs. 0% and 58% vs. 2%, respectively).

Approximately 42% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib remained on the therapy at up to 8 years, with a median follow-up of 7.4 years. Overall survival at 7 years was 78% for ibrutinib; overall survival data were not collected for chlorambucil for patients with progressive disease after the median of 5 years, as these patients were eligible to switch to ibrutinib in a long-term extension study or exit the study.

Adverse events prompted reduction of ibrutinib in 30 patients and dose holding for at least 7 days in 79 patients. However, dose modification resolved or improved the adverse events in 85% of the patients with held doses and 90% of those with reduced doses.

The overall prevalence of adverse events was similar to previous follow-up data at 5 years. No new safety signals were observed during the longer study period. The rate of treatment discontinuation because of adverse events was highest in the first year.

“We have been surprised at how long the remissions have lasted with ibrutinib,” said Dr. Barr. “Even with up to 8 years of follow-up, we have yet to reach the median progression free-survival,” he noted.

“These data, in combination with other data sets, highlight the impact that ibrutinib and other BTK inhibitors have had in treating CLL,” said Dr. Barr. “Patients are living longer and avoiding the side effects of chemotherapy in the era of novel agent use,” he said.

However, research gaps remain, Dr. Barr noted. “We need to continue following these patients over time given the length of the remissions. Additionally, we need to continue investigating novel combinations,” he said. Such studies will help us understand the benefit of fixed durations regimens compared to single agent BTK inhibitors,” he emphasized.

Safety and efficacy remain promising

“Ibrutinib was approved for the treatment of CLL, but only in the relapsed setting,” Susan M. O’Brien, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, said in an interview. “This trial was important because it led to the approval of ibrutinib in the front-line setting, making it the first, and at the time, only, small molecule that could be used upfront,” said Dr. O’Brien, who was not involved with the study.

“The initial results were certainly not surprising, as given the efficacy of ibrutinib in the relapsed setting, it seemed likely that it would produce a longer PFS than chlorambucil,” said Dr. O’Brien. “What may not have been expected though, is the incredible durability of these responses with ibrutinib,” she noted.

The clinical implications of the long-term data are that ibrutinib is producing “very durable remissions with continuous therapy,” Dr. O’Brien said. “There are no late safety signals and most side effects diminish with time. However, hypertension and atrial fibrillation continue to occur, so continued monitoring of blood pressure in these patients is important,” she emphasized.

Minor, but annoying, side effects are not infrequent early on with ibrutinib and may present a barrier to use for some patients, Dr. O’Brien said. “Some side effects may be overcome with temporary pauses of drug or dose reduction,” she noted. However, “it is important for patients to be aware that most of these side effects will completely abate with time,” she added.

“The main limitation of this trial was that the comparison was to a rather weak chemotherapy agent, albeit it one frequently used in older patients, particularly in Europe,” said Dr. O’Brien. “Nevertheless, two subsequent trials comparing ibrutinib (with or without rituximab) with either BR [bendamustine/rituximab] or FCR [fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab] showed a longer PFS with ibrutinib, as compared to that seen with either chemoimmunotherapy regimen,” she said.

The study was supported by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Dr. Barr collaborated with sponsor AbbVie on the study design, and disclosed relationships with companies including AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, MEI Pharma, Merck, Morphosys, Pharmacyclics LLC (an AbbVie company), Seattle Genetics, and TG Therapeutics. Dr. O’Brien had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM BLOOD ADVANCES

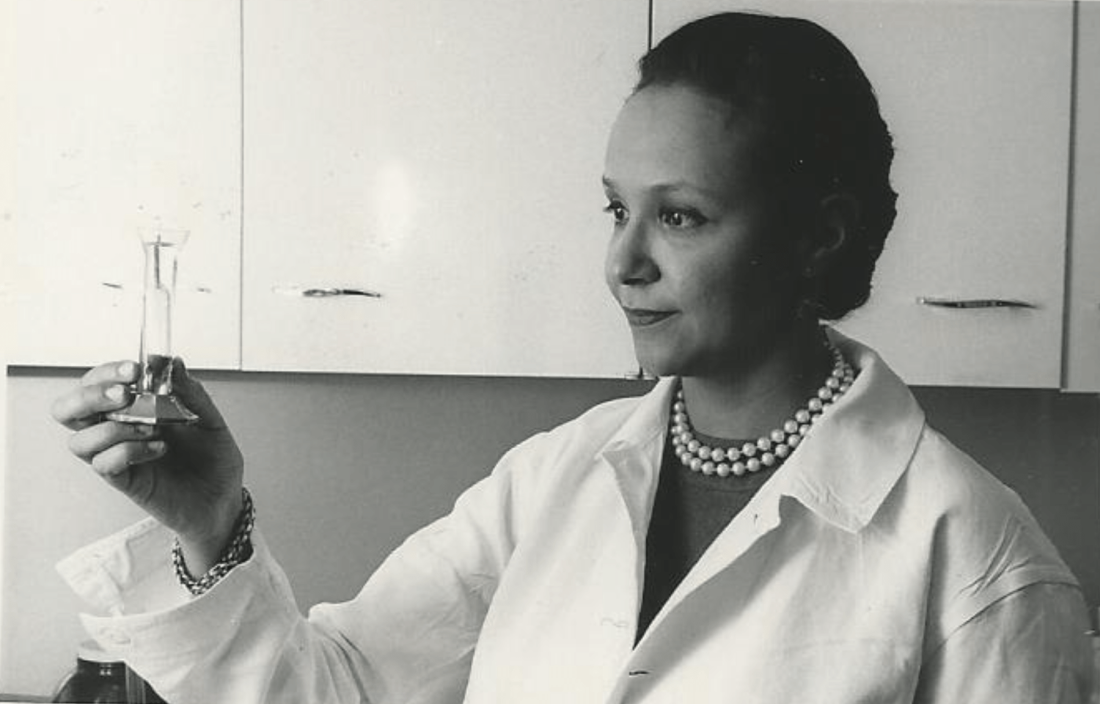

Third-generation Black woman physician makes cancer research history

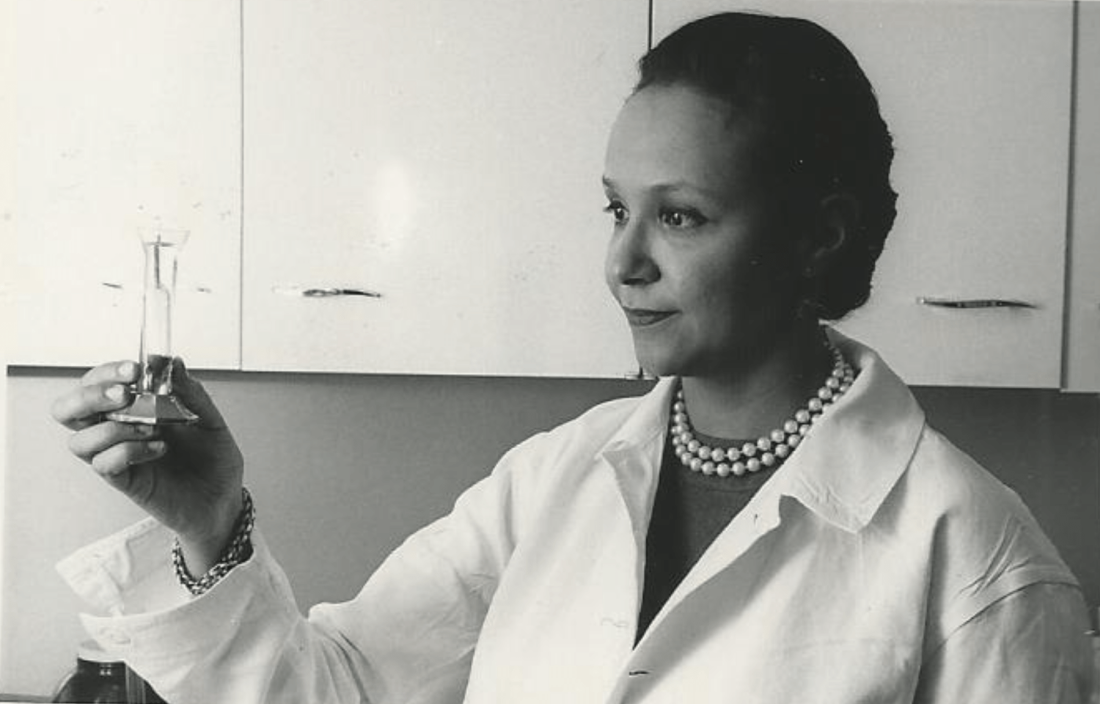

When Jane Cooke Wright, MD, entered the medical profession in 1945, the notion that toxic drugs could target tumors struck many physicians and patients as outlandish. How could one poison be weaponized against another poison – a cancerous tumor – without creating more havoc? Let alone a combination of two or more chemicals?

Dr. Wright’s story would be extraordinary enough if she’d looked like most of her colleagues, but this surgeon and researcher stood apart. An African American woman at a time when medicine and science – like politics and law – were almost entirely the domain of White men, Dr. Wright had determination in her blood. Her father, once honored by a crowd of dignitaries that included a First Lady, persevered despite his horrific encounters with racism. She shared her father’s commitment to progress and added her own personal twists. She balanced elegance and beauty with scientific savvy, fierce ambition, and a refusal to be defined by anything other than her accomplishments.

“She didn’t focus on race, not at all,” her daughter Alison Jones, PhD, a psychologist in East Lansing, Mich., said in an interview. “Wherever she was, she wanted to be the best, not the best Black person. It was not about how she performed in a category, and she would get upset if someone said she was good as a Black physician.”

On the road to being the best, Dr. Jones said, her mother set a goal of curing cancer. National Cancer Research Month is a fitting opportunity to look back on a scientist dedicated to bringing humanity closer to that elusive achievement.

Medical legacy blazed in toil and trauma

A strong case could be made that Dr. Jane C. Wright and her father Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, are the most accomplished father-and-daughter team in all of medicine.

The elder Dr. Wright, son of a formerly enslaved man turned physician and a stepson of the first African American to graduate from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., himself graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1915. He earned a Purple Heart while serving in World War I, then went on to become the first Black surgeon to join the staff at Harlem Hospital.

Dr. Wright, who had witnessed mob violence and the aftermath of a lynching as a young man, became a supporter of the Harlem Renaissance and a prominent advocate for civil rights and integration. He served as chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and was only the second Black member of the American College of Surgeons.

According to the 2009 book “Black Genius: Inspirational Portraits of African American Leaders,” he successfully treated the rare but devastating venereal disease lymphogranuloma venereum with a new antibiotic developed by his former colleague Yellapragada SubbaRow, MD. Dr. Wright even tried the drug himself, “as a lot of doctors in the olden days did,” according to another of his daughters, the late Barbara Wright Pierce, MD, who was quoted in “Black Genius.” She, too, was a physician.

In 1948, Dr. Jane C. Wright joined her father at Harlem Hospital’s Cancer Research Foundation. There the duo explored the cancer-fighting possibilities of a nitrogen mustard–like chemical agent that had been known since World War I to kill white blood cells. Ironically, Dr. Louis Wright himself suffered lifelong health problems because of an attack from the poisonous gas phosgene during his wartime service.

“Remissions were observed in patients with sarcoma, Hodgkin disease, and chronic myelogenous leukemia, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma,” reported a 2013 obituary in the journal Oncology of the younger Dr. Wright. “They also performed early research into the clinical efficacy and toxicity of folic acid antagonists, documenting responses in 93 patients with various forms of incurable blood cancers and solid tumors.”

This research appears in a study that was authored by three Dr. Wrights – Dr. Louis T. Wright and his daughters Jane and Barbara.

“The elder Dr. Wright died in 1952, just months after 1,000 people – including Eleanor Roosevelt – honored him at a dinner to dedicate a Harlem Hospital library named after him. He was 61.

Scientific savvy mixed with modesty and elegance

After her father’s death, Dr. Janet C. Wright became director of the hospital’s cancer foundation. From the 1950s to the 1970s, she “worked out ways to use pieces of a patient’s own tumor, removed by surgery and grown in a nutrient culture medium in the laboratory, as a ‘guinea pig for testing drugs,’ ” according to the 1991 book “Black Scientists.” Previously, researchers had focused on mice as test subjects.

This approach also allowed Dr. Wright to determine if specific drugs such as methotrexate, a folic acid antagonist, would help specific patients. “She was looking for predictive activity for chemotherapeutic efficacy in vitro at a time when no one had good predictive tests,” wrote James F. Holland, MD, the late Mount Sinai School of Medicine oncologist, who was quoted in Dr. Wright’s 2013 Oncology obituary.

“Her strict attention to detail and concern for her patients helped determine effective dosing levels and establish treatment guidelines,” the Oncology obituary reported. “She treated patients that other physicians had given up on, and she was among the first small cadre of researchers to carefully test the effects of drugs against cancer in a clinical trial setting.”

Dr. Wright also focused on developing ways to administer chemotherapy, such using a catheter to reach difficult-to-access organs like the spleen without surgery, according to “Black Scientists.”

Along with her work, Dr. Wright’s appearance set her apart. According to “Black Genius,” a newspaper columnist dubbed her one of the 10 most beautiful Back woman in America, and Ebony Magazine in 1966 honored her as one of the best-dressed women in America. It featured a photograph of her in a stunning ivory and yellow brocade gown, noting that she was “in private life Mrs. David J. Jones.” (She’d married the Harvard University Law School graduate in 1946.)

Dr. Wright had a sense of modesty despite her accomplishments, according to her daughter Alison Jones. She even downplayed her own mental powers in a newspaper interview. “I know I’m a member of two minority groups,” she told The New York Post in 1967, “but I don’t think of myself that way. Sure, a woman has to try twice as hard. But – racial prejudice? I’ve met very little of it. It could be I met it – and wasn’t intelligent enough to recognize it.”

Sharp-eyed readers might have glimpsed her modesty nearly 2 decades later. In a 1984 article for the Journal of the National Medical Association, a society of African American physicians, she wrote about the past, present, and future of chemotherapy without noting her own prominent role in its development.

‘Global medical pioneer’ cofounds ASCO – and more

In the 1960s, Dr. Wright joined the influential President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke and was named associate dean at New York Medical College, her alma mater, a first for a black woman at a prominent U.S. medical school. Even more importantly, Dr. Wright was the sole woman among seven physicians who founded the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago in 1964. She served as ASCO’s first Secretary-Treasurer and was honored as its longest surviving founder when she passed away 9 years ago.

“Jane Wright had the vision to see that oncology was an important separate discipline within medicine with far-reaching implications for research and discovery,” Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, oncologist Sandra M. Swain, MD, a former president of the ASCO and author of the 2013 Oncology obituary of Dr. Wright, said in an interview. “It is truly remarkable that, as a woman and an African American woman, she had a seat at the very small table for the formation of such an important group.”

As her friend and fellow oncologist Edith Mitchell, MD, said in a eulogy, “Dr. Wright led delegations of oncologists to China and the Soviet Union, and countries in Africa and Eastern Europe. She led medical teams providing medical and cancer care and education to other nurses and physicians in Ghana in 1957 and Kenya in 1961. From 1973 to 1984, she served as vice-president of the African Research and Medical foundation.”

Dr. Wright also raised two daughters. A 1968 Ebony article devoted to her career and family declared that neither of her teenagers was interested in medical careers. Their perspectives shifted, however – as had Dr. Wright’s. An undergraduate at Smith College, Dr. Wright majored in art, swam on the varsity team, and had a special affinity for German language studies before she switched to premed.

Like their mother, Dr. Wright’s daughters also changed paths, and they ultimately became the fourth generation of their family to enter the medical field. Dr. Alison Jones, the psychologist, currently works in a prison, while Jane Jones, MD, became a clinical psychiatrist. She’s now retired and lives in Guttenberg, N.J.

Both fondly remember their mother as a supportive force who insisted on excellence. “There couldn’t be any excuses for you not getting where you wanted to go,” Dr. Jane Jones recalled in an interview.

Nevertheless, Dr. Wright was still keenly aware of society’s limits. “She told me I had to be a doctor or lawyer,” Dr. Alison Jones said, “because that’s how you need to survive when you’re Black in America.”

Dr. Wright passed away in 2013 at age 93. “Dr. Jane C. Wright truly has made contributions that have changed the practice of medicine,” noted her friend Dr. Mitchell, an oncologist and a retired brigadier general with the U.S. Air Force who now teaches at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. “A true pioneer. A concerned mentor. A renowned researcher. A global teacher. A global medical pioneer. A talented researcher, beloved sister, wife, and mother, and a beautiful, kind, and loving human being.”

When Jane Cooke Wright, MD, entered the medical profession in 1945, the notion that toxic drugs could target tumors struck many physicians and patients as outlandish. How could one poison be weaponized against another poison – a cancerous tumor – without creating more havoc? Let alone a combination of two or more chemicals?

Dr. Wright’s story would be extraordinary enough if she’d looked like most of her colleagues, but this surgeon and researcher stood apart. An African American woman at a time when medicine and science – like politics and law – were almost entirely the domain of White men, Dr. Wright had determination in her blood. Her father, once honored by a crowd of dignitaries that included a First Lady, persevered despite his horrific encounters with racism. She shared her father’s commitment to progress and added her own personal twists. She balanced elegance and beauty with scientific savvy, fierce ambition, and a refusal to be defined by anything other than her accomplishments.

“She didn’t focus on race, not at all,” her daughter Alison Jones, PhD, a psychologist in East Lansing, Mich., said in an interview. “Wherever she was, she wanted to be the best, not the best Black person. It was not about how she performed in a category, and she would get upset if someone said she was good as a Black physician.”

On the road to being the best, Dr. Jones said, her mother set a goal of curing cancer. National Cancer Research Month is a fitting opportunity to look back on a scientist dedicated to bringing humanity closer to that elusive achievement.

Medical legacy blazed in toil and trauma

A strong case could be made that Dr. Jane C. Wright and her father Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, are the most accomplished father-and-daughter team in all of medicine.

The elder Dr. Wright, son of a formerly enslaved man turned physician and a stepson of the first African American to graduate from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., himself graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1915. He earned a Purple Heart while serving in World War I, then went on to become the first Black surgeon to join the staff at Harlem Hospital.

Dr. Wright, who had witnessed mob violence and the aftermath of a lynching as a young man, became a supporter of the Harlem Renaissance and a prominent advocate for civil rights and integration. He served as chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and was only the second Black member of the American College of Surgeons.

According to the 2009 book “Black Genius: Inspirational Portraits of African American Leaders,” he successfully treated the rare but devastating venereal disease lymphogranuloma venereum with a new antibiotic developed by his former colleague Yellapragada SubbaRow, MD. Dr. Wright even tried the drug himself, “as a lot of doctors in the olden days did,” according to another of his daughters, the late Barbara Wright Pierce, MD, who was quoted in “Black Genius.” She, too, was a physician.

In 1948, Dr. Jane C. Wright joined her father at Harlem Hospital’s Cancer Research Foundation. There the duo explored the cancer-fighting possibilities of a nitrogen mustard–like chemical agent that had been known since World War I to kill white blood cells. Ironically, Dr. Louis Wright himself suffered lifelong health problems because of an attack from the poisonous gas phosgene during his wartime service.

“Remissions were observed in patients with sarcoma, Hodgkin disease, and chronic myelogenous leukemia, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma,” reported a 2013 obituary in the journal Oncology of the younger Dr. Wright. “They also performed early research into the clinical efficacy and toxicity of folic acid antagonists, documenting responses in 93 patients with various forms of incurable blood cancers and solid tumors.”

This research appears in a study that was authored by three Dr. Wrights – Dr. Louis T. Wright and his daughters Jane and Barbara.

“The elder Dr. Wright died in 1952, just months after 1,000 people – including Eleanor Roosevelt – honored him at a dinner to dedicate a Harlem Hospital library named after him. He was 61.

Scientific savvy mixed with modesty and elegance

After her father’s death, Dr. Janet C. Wright became director of the hospital’s cancer foundation. From the 1950s to the 1970s, she “worked out ways to use pieces of a patient’s own tumor, removed by surgery and grown in a nutrient culture medium in the laboratory, as a ‘guinea pig for testing drugs,’ ” according to the 1991 book “Black Scientists.” Previously, researchers had focused on mice as test subjects.

This approach also allowed Dr. Wright to determine if specific drugs such as methotrexate, a folic acid antagonist, would help specific patients. “She was looking for predictive activity for chemotherapeutic efficacy in vitro at a time when no one had good predictive tests,” wrote James F. Holland, MD, the late Mount Sinai School of Medicine oncologist, who was quoted in Dr. Wright’s 2013 Oncology obituary.

“Her strict attention to detail and concern for her patients helped determine effective dosing levels and establish treatment guidelines,” the Oncology obituary reported. “She treated patients that other physicians had given up on, and she was among the first small cadre of researchers to carefully test the effects of drugs against cancer in a clinical trial setting.”

Dr. Wright also focused on developing ways to administer chemotherapy, such using a catheter to reach difficult-to-access organs like the spleen without surgery, according to “Black Scientists.”

Along with her work, Dr. Wright’s appearance set her apart. According to “Black Genius,” a newspaper columnist dubbed her one of the 10 most beautiful Back woman in America, and Ebony Magazine in 1966 honored her as one of the best-dressed women in America. It featured a photograph of her in a stunning ivory and yellow brocade gown, noting that she was “in private life Mrs. David J. Jones.” (She’d married the Harvard University Law School graduate in 1946.)

Dr. Wright had a sense of modesty despite her accomplishments, according to her daughter Alison Jones. She even downplayed her own mental powers in a newspaper interview. “I know I’m a member of two minority groups,” she told The New York Post in 1967, “but I don’t think of myself that way. Sure, a woman has to try twice as hard. But – racial prejudice? I’ve met very little of it. It could be I met it – and wasn’t intelligent enough to recognize it.”

Sharp-eyed readers might have glimpsed her modesty nearly 2 decades later. In a 1984 article for the Journal of the National Medical Association, a society of African American physicians, she wrote about the past, present, and future of chemotherapy without noting her own prominent role in its development.

‘Global medical pioneer’ cofounds ASCO – and more

In the 1960s, Dr. Wright joined the influential President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke and was named associate dean at New York Medical College, her alma mater, a first for a black woman at a prominent U.S. medical school. Even more importantly, Dr. Wright was the sole woman among seven physicians who founded the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago in 1964. She served as ASCO’s first Secretary-Treasurer and was honored as its longest surviving founder when she passed away 9 years ago.

“Jane Wright had the vision to see that oncology was an important separate discipline within medicine with far-reaching implications for research and discovery,” Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, oncologist Sandra M. Swain, MD, a former president of the ASCO and author of the 2013 Oncology obituary of Dr. Wright, said in an interview. “It is truly remarkable that, as a woman and an African American woman, she had a seat at the very small table for the formation of such an important group.”

As her friend and fellow oncologist Edith Mitchell, MD, said in a eulogy, “Dr. Wright led delegations of oncologists to China and the Soviet Union, and countries in Africa and Eastern Europe. She led medical teams providing medical and cancer care and education to other nurses and physicians in Ghana in 1957 and Kenya in 1961. From 1973 to 1984, she served as vice-president of the African Research and Medical foundation.”

Dr. Wright also raised two daughters. A 1968 Ebony article devoted to her career and family declared that neither of her teenagers was interested in medical careers. Their perspectives shifted, however – as had Dr. Wright’s. An undergraduate at Smith College, Dr. Wright majored in art, swam on the varsity team, and had a special affinity for German language studies before she switched to premed.

Like their mother, Dr. Wright’s daughters also changed paths, and they ultimately became the fourth generation of their family to enter the medical field. Dr. Alison Jones, the psychologist, currently works in a prison, while Jane Jones, MD, became a clinical psychiatrist. She’s now retired and lives in Guttenberg, N.J.

Both fondly remember their mother as a supportive force who insisted on excellence. “There couldn’t be any excuses for you not getting where you wanted to go,” Dr. Jane Jones recalled in an interview.

Nevertheless, Dr. Wright was still keenly aware of society’s limits. “She told me I had to be a doctor or lawyer,” Dr. Alison Jones said, “because that’s how you need to survive when you’re Black in America.”

Dr. Wright passed away in 2013 at age 93. “Dr. Jane C. Wright truly has made contributions that have changed the practice of medicine,” noted her friend Dr. Mitchell, an oncologist and a retired brigadier general with the U.S. Air Force who now teaches at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. “A true pioneer. A concerned mentor. A renowned researcher. A global teacher. A global medical pioneer. A talented researcher, beloved sister, wife, and mother, and a beautiful, kind, and loving human being.”

When Jane Cooke Wright, MD, entered the medical profession in 1945, the notion that toxic drugs could target tumors struck many physicians and patients as outlandish. How could one poison be weaponized against another poison – a cancerous tumor – without creating more havoc? Let alone a combination of two or more chemicals?

Dr. Wright’s story would be extraordinary enough if she’d looked like most of her colleagues, but this surgeon and researcher stood apart. An African American woman at a time when medicine and science – like politics and law – were almost entirely the domain of White men, Dr. Wright had determination in her blood. Her father, once honored by a crowd of dignitaries that included a First Lady, persevered despite his horrific encounters with racism. She shared her father’s commitment to progress and added her own personal twists. She balanced elegance and beauty with scientific savvy, fierce ambition, and a refusal to be defined by anything other than her accomplishments.

“She didn’t focus on race, not at all,” her daughter Alison Jones, PhD, a psychologist in East Lansing, Mich., said in an interview. “Wherever she was, she wanted to be the best, not the best Black person. It was not about how she performed in a category, and she would get upset if someone said she was good as a Black physician.”

On the road to being the best, Dr. Jones said, her mother set a goal of curing cancer. National Cancer Research Month is a fitting opportunity to look back on a scientist dedicated to bringing humanity closer to that elusive achievement.

Medical legacy blazed in toil and trauma

A strong case could be made that Dr. Jane C. Wright and her father Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, are the most accomplished father-and-daughter team in all of medicine.

The elder Dr. Wright, son of a formerly enslaved man turned physician and a stepson of the first African American to graduate from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., himself graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1915. He earned a Purple Heart while serving in World War I, then went on to become the first Black surgeon to join the staff at Harlem Hospital.

Dr. Wright, who had witnessed mob violence and the aftermath of a lynching as a young man, became a supporter of the Harlem Renaissance and a prominent advocate for civil rights and integration. He served as chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and was only the second Black member of the American College of Surgeons.

According to the 2009 book “Black Genius: Inspirational Portraits of African American Leaders,” he successfully treated the rare but devastating venereal disease lymphogranuloma venereum with a new antibiotic developed by his former colleague Yellapragada SubbaRow, MD. Dr. Wright even tried the drug himself, “as a lot of doctors in the olden days did,” according to another of his daughters, the late Barbara Wright Pierce, MD, who was quoted in “Black Genius.” She, too, was a physician.

In 1948, Dr. Jane C. Wright joined her father at Harlem Hospital’s Cancer Research Foundation. There the duo explored the cancer-fighting possibilities of a nitrogen mustard–like chemical agent that had been known since World War I to kill white blood cells. Ironically, Dr. Louis Wright himself suffered lifelong health problems because of an attack from the poisonous gas phosgene during his wartime service.

“Remissions were observed in patients with sarcoma, Hodgkin disease, and chronic myelogenous leukemia, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma,” reported a 2013 obituary in the journal Oncology of the younger Dr. Wright. “They also performed early research into the clinical efficacy and toxicity of folic acid antagonists, documenting responses in 93 patients with various forms of incurable blood cancers and solid tumors.”

This research appears in a study that was authored by three Dr. Wrights – Dr. Louis T. Wright and his daughters Jane and Barbara.

“The elder Dr. Wright died in 1952, just months after 1,000 people – including Eleanor Roosevelt – honored him at a dinner to dedicate a Harlem Hospital library named after him. He was 61.

Scientific savvy mixed with modesty and elegance

After her father’s death, Dr. Janet C. Wright became director of the hospital’s cancer foundation. From the 1950s to the 1970s, she “worked out ways to use pieces of a patient’s own tumor, removed by surgery and grown in a nutrient culture medium in the laboratory, as a ‘guinea pig for testing drugs,’ ” according to the 1991 book “Black Scientists.” Previously, researchers had focused on mice as test subjects.

This approach also allowed Dr. Wright to determine if specific drugs such as methotrexate, a folic acid antagonist, would help specific patients. “She was looking for predictive activity for chemotherapeutic efficacy in vitro at a time when no one had good predictive tests,” wrote James F. Holland, MD, the late Mount Sinai School of Medicine oncologist, who was quoted in Dr. Wright’s 2013 Oncology obituary.

“Her strict attention to detail and concern for her patients helped determine effective dosing levels and establish treatment guidelines,” the Oncology obituary reported. “She treated patients that other physicians had given up on, and she was among the first small cadre of researchers to carefully test the effects of drugs against cancer in a clinical trial setting.”

Dr. Wright also focused on developing ways to administer chemotherapy, such using a catheter to reach difficult-to-access organs like the spleen without surgery, according to “Black Scientists.”

Along with her work, Dr. Wright’s appearance set her apart. According to “Black Genius,” a newspaper columnist dubbed her one of the 10 most beautiful Back woman in America, and Ebony Magazine in 1966 honored her as one of the best-dressed women in America. It featured a photograph of her in a stunning ivory and yellow brocade gown, noting that she was “in private life Mrs. David J. Jones.” (She’d married the Harvard University Law School graduate in 1946.)

Dr. Wright had a sense of modesty despite her accomplishments, according to her daughter Alison Jones. She even downplayed her own mental powers in a newspaper interview. “I know I’m a member of two minority groups,” she told The New York Post in 1967, “but I don’t think of myself that way. Sure, a woman has to try twice as hard. But – racial prejudice? I’ve met very little of it. It could be I met it – and wasn’t intelligent enough to recognize it.”

Sharp-eyed readers might have glimpsed her modesty nearly 2 decades later. In a 1984 article for the Journal of the National Medical Association, a society of African American physicians, she wrote about the past, present, and future of chemotherapy without noting her own prominent role in its development.

‘Global medical pioneer’ cofounds ASCO – and more

In the 1960s, Dr. Wright joined the influential President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke and was named associate dean at New York Medical College, her alma mater, a first for a black woman at a prominent U.S. medical school. Even more importantly, Dr. Wright was the sole woman among seven physicians who founded the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago in 1964. She served as ASCO’s first Secretary-Treasurer and was honored as its longest surviving founder when she passed away 9 years ago.

“Jane Wright had the vision to see that oncology was an important separate discipline within medicine with far-reaching implications for research and discovery,” Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, oncologist Sandra M. Swain, MD, a former president of the ASCO and author of the 2013 Oncology obituary of Dr. Wright, said in an interview. “It is truly remarkable that, as a woman and an African American woman, she had a seat at the very small table for the formation of such an important group.”

As her friend and fellow oncologist Edith Mitchell, MD, said in a eulogy, “Dr. Wright led delegations of oncologists to China and the Soviet Union, and countries in Africa and Eastern Europe. She led medical teams providing medical and cancer care and education to other nurses and physicians in Ghana in 1957 and Kenya in 1961. From 1973 to 1984, she served as vice-president of the African Research and Medical foundation.”

Dr. Wright also raised two daughters. A 1968 Ebony article devoted to her career and family declared that neither of her teenagers was interested in medical careers. Their perspectives shifted, however – as had Dr. Wright’s. An undergraduate at Smith College, Dr. Wright majored in art, swam on the varsity team, and had a special affinity for German language studies before she switched to premed.

Like their mother, Dr. Wright’s daughters also changed paths, and they ultimately became the fourth generation of their family to enter the medical field. Dr. Alison Jones, the psychologist, currently works in a prison, while Jane Jones, MD, became a clinical psychiatrist. She’s now retired and lives in Guttenberg, N.J.

Both fondly remember their mother as a supportive force who insisted on excellence. “There couldn’t be any excuses for you not getting where you wanted to go,” Dr. Jane Jones recalled in an interview.

Nevertheless, Dr. Wright was still keenly aware of society’s limits. “She told me I had to be a doctor or lawyer,” Dr. Alison Jones said, “because that’s how you need to survive when you’re Black in America.”

Dr. Wright passed away in 2013 at age 93. “Dr. Jane C. Wright truly has made contributions that have changed the practice of medicine,” noted her friend Dr. Mitchell, an oncologist and a retired brigadier general with the U.S. Air Force who now teaches at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. “A true pioneer. A concerned mentor. A renowned researcher. A global teacher. A global medical pioneer. A talented researcher, beloved sister, wife, and mother, and a beautiful, kind, and loving human being.”

Ex–hospital porter a neglected giant of cancer research

We have a half-forgotten Indian immigrant to thank – a hospital night porter turned biochemist –for revolutionizing treatment of leukemia, the once deadly childhood scourge that is still the most common pediatric cancer.

Dr. Yellapragada SubbaRow has been called the “father of chemotherapy” for developing methotrexate, a powerful, inexpensive therapy for leukemia and other diseases, and he is celebrated for additional scientific achievements. Yet Dr. SubbaRow’s life was marked more by struggle than glory.

Born poor in southeastern India, he nearly succumbed to a tropical disease that killed two older brothers, and he didn’t focus on schoolwork until his father died. Later, prejudice dogged his years as an immigrant to the United States, and a blood clot took his life at the age of 53.

Scientifically, however, Dr. SubbaRow (pronounced sue-buh-rao) triumphed, despite mammoth challenges and a lack of recognition that persists to this day. National Cancer Research Month is a fitting time to look back on his extraordinary life and work and pay tribute to his accomplishments.

‘Yella,’ folic acid, and a paradigm shift

No one appreciates Dr. SubbaRow more than a cadre of Indian-born physicians who have kept his legacy alive in journal articles, presentations, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning book. Among them is author and oncologist Siddhartha Mukherjee, MD, who chronicled Dr. SubbaRow’s achievements in his New York Times No. 1 bestseller, “The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer.”

As Dr. Mukherjee wrote, Dr. SubbaRow was a “pioneer in many ways, a physician turned cellular physiologist, a chemist who had accidentally wandered into biology.” (Per Indian tradition, SubbaRow is the doctor’s first name, and Yellapragada is his surname, but medical literature uses SubbaRow as his cognomen, with some variations in spelling. Dr. Mukherjee wrote that his friends called him “Yella.”)

Dr. SubbaRow came to the United States in 1923, after enduring a difficult childhood and young adulthood. He’d survived bouts of religious fervor, childhood rebellion (including a bid to run away from home and become a banana trader), and a failed arranged marriage. His wife bore him a child who died in infancy. He left it all behind.

In Boston, medical officials rejected his degree. Broke, he worked for a time as a night porter at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, changing sheets and cleaning urinals. To a poor but proud high-caste Indian Brahmin, the culture shock of carrying out these tasks must have been especially jarring.

Dr. SubbaRow went on to earn a diploma from Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, and became a junior faculty member. As a foreigner, Dr. Mukherjee wrote, Dr. SubbaRow was a “reclusive, nocturnal, heavily accented vegetarian,” so different from his colleagues that advancement seemed impossible. Despite his pioneering biochemistry work, Harvard later declined to offer Dr. SubbaRow a tenured faculty position.

By the early 1940s, he took a job at an upstate New York pharmaceutical company called Lederle Labs (later purchased by Pfizer). At Lederle, Dr. SubbaRow strove to synthesize the vitamin known as folic acid. He ended up creating a kind of antivitamin, a lookalike that acted like folic acid but only succeeded in gumming up the works in receptors. But what good would it do to stop the body from absorbing folic acid? Plenty, it turned out.

Discoveries pile up, but credit and fame prove elusive

Dr. SubbaRow was no stranger to producing landmark biological work. He’d previously codiscovered phosphocreatine and ATP, which are crucial to muscular contractions. However, “in 1935, he had to disown the extent of his role in the discovery of the color test related to phosphorus, instead giving the credit to his co-author, who was being considered for promotion to a full professorship at Harvard,” wrote author Gerald Posner in his 2020 book, “Pharma: Greed, Lies and the Poisoning of America.”

Houston-area oncologist Kirtan Nautiyal, MD, who paid tribute to Dr. SubbaRow in a 2018 article, contended that “with his Indian instinct for self-effacement, he had irreparably sabotaged his own career.”

Dr. SubbaRow and his team also developed “the first effective treatment of filariasis, which causes elephantiasis of the lower limbs and genitals in millions of people, mainly in tropical countries,” Dr. Nautiyal wrote. “Later in the decade, his antibiotic program generated polymyxin, the first effective treatment against the class of bacteria called Gram negatives, and aureomycin, the first “broad-spectrum’ antibiotic.” (Aureomycin is also the first tetracycline antibiotic.)

Dr. SubbaRow’s discovery of a folic acid antagonist would again go largely unheralded. But first came the realization that folic acid made childhood leukemia worse, not better, and the prospect that this process could potentially be reversed.

Rise of methotrexate and fall of leukemia

In Boston, Sidney Farber, MD, a Boston pathologist, was desperate to help Robert Sandler, a 2-year-old leukemia patient. Dr. Farber contacted his ex-colleague Dr. SubbaRow to request a supply of aminopterin, an early version of methotrexate that Dr. SubbaRow and his team had developed. Dr. Farber injected Robert with the substance and within 3 days, the toddler’s white blood count started falling – fast. He stopped bleeding, resumed eating, and once again seemed almost identical to his twin brother, as Dr. Mukherjee wrote in his book.

Leukemia had never gone into remission before. Unfortunately, the treatment only worked temporarily. Robert, like other children treated with the drug, relapsed and died within months. But Dr. Farber “saw a door open” – a chemical, a kind of chemotherapy, that could turn back cancer. In the case of folic acid antagonists, they do so by stopping cancer cells from replicating.

Methotrexate, a related agent synthesized by Dr. SubbaRow, would become a mainstay of leukemia treatment and begin to produce long-term remission from acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 1970, when combination chemotherapy was developed.

Other cancers fell to methotrexate treatment. “Previous assumptions that cancer was nearly always fatal were revised, and the field of medical oncology (treatment of cancer with chemotherapy), which had not previously existed, was formally established in 1971,” according to the National Cancer Institute’s history of methotrexate. This account does not mention Dr. SubbaRow.

Death takes the doctor, but his legacy remains

In biographies, as well as his own words, Dr. SubbaRow comes across as a prickly, hard-driving workaholic who had little interest in intimate human connections. “It is not good to ask in every letter when I will be back,” he wrote to his wife back in India, before cutting off ties completely in the early 1930s. “I will come as early as possible. ... I do not want to write anything more.”

It seems, as his biographer S.P.K. Gupta noted, that “he was quite determined that the time allotted to him on Earth should be completely devoted to finding cures for ailments that plagued mankind.”

Still, Dr. SubbaRow’s research team was devoted to him, and he had plenty of reasons to be bitter, such as the prejudice and isolation he encountered in the United States and earlier, in British-run India. According to Mr. Posner’s book, even as a young medical student, Dr. SubbaRow heeded the call of Indian independence activist Mohandas Gandhi. He “refused the British surgical gown given him at school and instead donned a traditional and simple cotton Khadi. That act of defiance cost SubbaRow the college degree that was necessary for him to get into the State Medical College.”