User login

FDA panel rejects vernakalant bid for AFib cardioversion indication

for cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib).

It was the second time before an FDA advisory panel for vernakalant (Brinavess, Correvio International Sàrl), which the agency had declined to approve in 2008 due to safety concerns. That time, however, its advisors had given the agency a decidedly positive recommendation.

Since then, registry data collected for the drug’s resubmission seemed only to raise further safety issues, especially evidence that a single infusion may cause severe hypotension and suppress left ventricular function.

Some members of the Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee (CRDAC), including a number who voted against approval, expressed hopes for further research aimed at identifying specific AFib patient groups who might safely benefit from vernakalant.

Of note, the drug has long been available for AFib cardioversion in Europe, where there are a number of other pharmacologic options, and was recently approved in Canada.

“We do recognize there’s a significant clinical need here,” observed Paul M. Ridker, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, a CRDAC panelist.

The results of the safety study that Correvio presented to the panel were “pretty marginal,” Dr. Ridker said. Given the negative safety signals and the available cardioversion alternatives, he questioned whether vernakalant represented a “substantial advance versus just another option. Right now, I’m not convinced it’s a substantial advance.”

FDA representatives were skeptical about vernakalant when they walked into the meeting room, as noted in briefing documents they had circulated beforehand. The drug’s safety experience under consideration included one case of ventricular arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock in a treated patient without apparent structural heart disease, who subsequently died. That case was much discussed throughout the meeting.

In its resubmission of vernakalant to regulators, Correvio also pointed to a significant unmet need for AFib cardioversion options in the United States, given the few alternatives.

For example, ibutilide is FDA-approved for recent-onset AFib or atrial flutter; but as the company and panelists noted, the drug isn’t often used for that indication. Patients with recent-onset AFib are often put on rate-control meds without cardioversion. Or clinicians may resort to electrical cardioversion, which can be logistically cumbersome and require anesthesia and generally a hospital stay.

Oral or intravenous amiodarone and oral dofetilide, flecainide, and propafenone are guideline-recommended but not actually FDA-approved for recent-onset AFib, the company noted.

Correvio made its “pre-infusion checklist” a core feature of its case. It was designed to guide selection of patients for vernakalant cardioversion based on contraindications such as a systolic blood pressure under 100 mm Hg, severe heart failure, aortic stenosis, severe bradycardia or heart block, or a prolonged QT interval.

In his presentation to the panel, FDA medical officer Preston Dunnmon, MD, said the safety results from the SPECTRUM registry, another main pillar of support for the vernakalant resubmission, “are not reassuring.”

As reasons, Dr. Dunnmon cited likely patient-selection bias and its high proportion of patients who were not prospectively enrolled; 21% were retrospectively entered from records.

Moreover, “the proposed preinfusion checklist will not reliably predict which subjects will experience serious cardiovascular adverse events with vernakalant,” he said.

“Vernakalant has induced harm that cannot be reliably predicted, prevented, or in some cases, treated. In contrast to vernakalant, electrical cardioversion and ibutilide pharmacologic cardioversion can cause adverse events, but these are transient and treatable,” he said.

Many on the panel agreed. “I thought the totality of evidence supported the hypothesis that this drug has a potential for a fatal side effect in a disease that you can live with, potentially, and that there are other treatments for,” said Julia B. Lewis, MD, Vanderbilt Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., who chaired the CRDAC panel.

“The drug clearly converts atrial fibrillation, although it’s only transient,” observed John H. Alexander, MD, MHSc, Duke University, Durham, N.C., one of the two panelists who voted to recommend approval of vernakalant.

“And, there clearly is a serious safety signal in some populations of patients,” he agreed. “However, I was more reassured by the SPECTRUM data.” There is likely to be a low-risk group of patients for whom vernakalant could represent an important option that “outweighs the relatively low risk of serious complications,” Dr. Alexander said.

“So more work needs to be done to clarify who are the low risk patients where it would be favorable.”

Panelist Matthew Needleman, MD, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., also voted in favor of approval.

“We’ve all known patients with normal ejection fractions who keep coming in with symptomatic atrial fib, want to get out of it quickly, and get back to their lives. So having an option like this I think would be good for a very select group of patients,” Dr. Needleman said.

But the preinfusion checklist and other potential ways to select low-risk patients for vernakalant could potentially backfire, warned John M. Mandrola, MD, Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., from the panel.

The FDA representatives had presented evidence that the drug can seriously depress ventricular function, and that the lower cardiac output is what leads to hypotension, he elaborated in an interview after the meeting.

If the checklist is used to exclude hemodynamically unstable patients from receiving vernakalant, he said, “Then you’re really giving this drug to relatively healthy patients for convenience, to decrease hospitalization or the hospital stay.”

The signal for substantial harm, Dr. Mandrola said, has to be balanced against that modest benefit.

Moreover, those in whom the drug doesn’t work may be left in a worse situation, he proposed. Only about half of patients are successfully converted on vernakalant, the company and FDA data suggested. The other half of patients who don’t achieve sinus rhythm on the drug still must face the significant hazards of depressed ejection fraction and hypotension, a high price to pay for an unsuccessful treatment.

Dr. Mandrola is Chief Cardiology Correspondent for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology; his disclosure statement states no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

for cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib).

It was the second time before an FDA advisory panel for vernakalant (Brinavess, Correvio International Sàrl), which the agency had declined to approve in 2008 due to safety concerns. That time, however, its advisors had given the agency a decidedly positive recommendation.

Since then, registry data collected for the drug’s resubmission seemed only to raise further safety issues, especially evidence that a single infusion may cause severe hypotension and suppress left ventricular function.

Some members of the Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee (CRDAC), including a number who voted against approval, expressed hopes for further research aimed at identifying specific AFib patient groups who might safely benefit from vernakalant.

Of note, the drug has long been available for AFib cardioversion in Europe, where there are a number of other pharmacologic options, and was recently approved in Canada.

“We do recognize there’s a significant clinical need here,” observed Paul M. Ridker, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, a CRDAC panelist.

The results of the safety study that Correvio presented to the panel were “pretty marginal,” Dr. Ridker said. Given the negative safety signals and the available cardioversion alternatives, he questioned whether vernakalant represented a “substantial advance versus just another option. Right now, I’m not convinced it’s a substantial advance.”

FDA representatives were skeptical about vernakalant when they walked into the meeting room, as noted in briefing documents they had circulated beforehand. The drug’s safety experience under consideration included one case of ventricular arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock in a treated patient without apparent structural heart disease, who subsequently died. That case was much discussed throughout the meeting.

In its resubmission of vernakalant to regulators, Correvio also pointed to a significant unmet need for AFib cardioversion options in the United States, given the few alternatives.

For example, ibutilide is FDA-approved for recent-onset AFib or atrial flutter; but as the company and panelists noted, the drug isn’t often used for that indication. Patients with recent-onset AFib are often put on rate-control meds without cardioversion. Or clinicians may resort to electrical cardioversion, which can be logistically cumbersome and require anesthesia and generally a hospital stay.

Oral or intravenous amiodarone and oral dofetilide, flecainide, and propafenone are guideline-recommended but not actually FDA-approved for recent-onset AFib, the company noted.

Correvio made its “pre-infusion checklist” a core feature of its case. It was designed to guide selection of patients for vernakalant cardioversion based on contraindications such as a systolic blood pressure under 100 mm Hg, severe heart failure, aortic stenosis, severe bradycardia or heart block, or a prolonged QT interval.

In his presentation to the panel, FDA medical officer Preston Dunnmon, MD, said the safety results from the SPECTRUM registry, another main pillar of support for the vernakalant resubmission, “are not reassuring.”

As reasons, Dr. Dunnmon cited likely patient-selection bias and its high proportion of patients who were not prospectively enrolled; 21% were retrospectively entered from records.

Moreover, “the proposed preinfusion checklist will not reliably predict which subjects will experience serious cardiovascular adverse events with vernakalant,” he said.

“Vernakalant has induced harm that cannot be reliably predicted, prevented, or in some cases, treated. In contrast to vernakalant, electrical cardioversion and ibutilide pharmacologic cardioversion can cause adverse events, but these are transient and treatable,” he said.

Many on the panel agreed. “I thought the totality of evidence supported the hypothesis that this drug has a potential for a fatal side effect in a disease that you can live with, potentially, and that there are other treatments for,” said Julia B. Lewis, MD, Vanderbilt Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., who chaired the CRDAC panel.

“The drug clearly converts atrial fibrillation, although it’s only transient,” observed John H. Alexander, MD, MHSc, Duke University, Durham, N.C., one of the two panelists who voted to recommend approval of vernakalant.

“And, there clearly is a serious safety signal in some populations of patients,” he agreed. “However, I was more reassured by the SPECTRUM data.” There is likely to be a low-risk group of patients for whom vernakalant could represent an important option that “outweighs the relatively low risk of serious complications,” Dr. Alexander said.

“So more work needs to be done to clarify who are the low risk patients where it would be favorable.”

Panelist Matthew Needleman, MD, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., also voted in favor of approval.

“We’ve all known patients with normal ejection fractions who keep coming in with symptomatic atrial fib, want to get out of it quickly, and get back to their lives. So having an option like this I think would be good for a very select group of patients,” Dr. Needleman said.

But the preinfusion checklist and other potential ways to select low-risk patients for vernakalant could potentially backfire, warned John M. Mandrola, MD, Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., from the panel.

The FDA representatives had presented evidence that the drug can seriously depress ventricular function, and that the lower cardiac output is what leads to hypotension, he elaborated in an interview after the meeting.

If the checklist is used to exclude hemodynamically unstable patients from receiving vernakalant, he said, “Then you’re really giving this drug to relatively healthy patients for convenience, to decrease hospitalization or the hospital stay.”

The signal for substantial harm, Dr. Mandrola said, has to be balanced against that modest benefit.

Moreover, those in whom the drug doesn’t work may be left in a worse situation, he proposed. Only about half of patients are successfully converted on vernakalant, the company and FDA data suggested. The other half of patients who don’t achieve sinus rhythm on the drug still must face the significant hazards of depressed ejection fraction and hypotension, a high price to pay for an unsuccessful treatment.

Dr. Mandrola is Chief Cardiology Correspondent for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology; his disclosure statement states no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

for cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib).

It was the second time before an FDA advisory panel for vernakalant (Brinavess, Correvio International Sàrl), which the agency had declined to approve in 2008 due to safety concerns. That time, however, its advisors had given the agency a decidedly positive recommendation.

Since then, registry data collected for the drug’s resubmission seemed only to raise further safety issues, especially evidence that a single infusion may cause severe hypotension and suppress left ventricular function.

Some members of the Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee (CRDAC), including a number who voted against approval, expressed hopes for further research aimed at identifying specific AFib patient groups who might safely benefit from vernakalant.

Of note, the drug has long been available for AFib cardioversion in Europe, where there are a number of other pharmacologic options, and was recently approved in Canada.

“We do recognize there’s a significant clinical need here,” observed Paul M. Ridker, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, a CRDAC panelist.

The results of the safety study that Correvio presented to the panel were “pretty marginal,” Dr. Ridker said. Given the negative safety signals and the available cardioversion alternatives, he questioned whether vernakalant represented a “substantial advance versus just another option. Right now, I’m not convinced it’s a substantial advance.”

FDA representatives were skeptical about vernakalant when they walked into the meeting room, as noted in briefing documents they had circulated beforehand. The drug’s safety experience under consideration included one case of ventricular arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock in a treated patient without apparent structural heart disease, who subsequently died. That case was much discussed throughout the meeting.

In its resubmission of vernakalant to regulators, Correvio also pointed to a significant unmet need for AFib cardioversion options in the United States, given the few alternatives.

For example, ibutilide is FDA-approved for recent-onset AFib or atrial flutter; but as the company and panelists noted, the drug isn’t often used for that indication. Patients with recent-onset AFib are often put on rate-control meds without cardioversion. Or clinicians may resort to electrical cardioversion, which can be logistically cumbersome and require anesthesia and generally a hospital stay.

Oral or intravenous amiodarone and oral dofetilide, flecainide, and propafenone are guideline-recommended but not actually FDA-approved for recent-onset AFib, the company noted.

Correvio made its “pre-infusion checklist” a core feature of its case. It was designed to guide selection of patients for vernakalant cardioversion based on contraindications such as a systolic blood pressure under 100 mm Hg, severe heart failure, aortic stenosis, severe bradycardia or heart block, or a prolonged QT interval.

In his presentation to the panel, FDA medical officer Preston Dunnmon, MD, said the safety results from the SPECTRUM registry, another main pillar of support for the vernakalant resubmission, “are not reassuring.”

As reasons, Dr. Dunnmon cited likely patient-selection bias and its high proportion of patients who were not prospectively enrolled; 21% were retrospectively entered from records.

Moreover, “the proposed preinfusion checklist will not reliably predict which subjects will experience serious cardiovascular adverse events with vernakalant,” he said.

“Vernakalant has induced harm that cannot be reliably predicted, prevented, or in some cases, treated. In contrast to vernakalant, electrical cardioversion and ibutilide pharmacologic cardioversion can cause adverse events, but these are transient and treatable,” he said.

Many on the panel agreed. “I thought the totality of evidence supported the hypothesis that this drug has a potential for a fatal side effect in a disease that you can live with, potentially, and that there are other treatments for,” said Julia B. Lewis, MD, Vanderbilt Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., who chaired the CRDAC panel.

“The drug clearly converts atrial fibrillation, although it’s only transient,” observed John H. Alexander, MD, MHSc, Duke University, Durham, N.C., one of the two panelists who voted to recommend approval of vernakalant.

“And, there clearly is a serious safety signal in some populations of patients,” he agreed. “However, I was more reassured by the SPECTRUM data.” There is likely to be a low-risk group of patients for whom vernakalant could represent an important option that “outweighs the relatively low risk of serious complications,” Dr. Alexander said.

“So more work needs to be done to clarify who are the low risk patients where it would be favorable.”

Panelist Matthew Needleman, MD, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., also voted in favor of approval.

“We’ve all known patients with normal ejection fractions who keep coming in with symptomatic atrial fib, want to get out of it quickly, and get back to their lives. So having an option like this I think would be good for a very select group of patients,” Dr. Needleman said.

But the preinfusion checklist and other potential ways to select low-risk patients for vernakalant could potentially backfire, warned John M. Mandrola, MD, Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., from the panel.

The FDA representatives had presented evidence that the drug can seriously depress ventricular function, and that the lower cardiac output is what leads to hypotension, he elaborated in an interview after the meeting.

If the checklist is used to exclude hemodynamically unstable patients from receiving vernakalant, he said, “Then you’re really giving this drug to relatively healthy patients for convenience, to decrease hospitalization or the hospital stay.”

The signal for substantial harm, Dr. Mandrola said, has to be balanced against that modest benefit.

Moreover, those in whom the drug doesn’t work may be left in a worse situation, he proposed. Only about half of patients are successfully converted on vernakalant, the company and FDA data suggested. The other half of patients who don’t achieve sinus rhythm on the drug still must face the significant hazards of depressed ejection fraction and hypotension, a high price to pay for an unsuccessful treatment.

Dr. Mandrola is Chief Cardiology Correspondent for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology; his disclosure statement states no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic test stratified AFib patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc scores

PHILADELPHIA – A 32-gene screening test for stroke risk identified a subgroup of atrial fibrillation (AFib) patients with an elevated rate of ischemic strokes despite having a low stroke risk by conventional criteria by their CHA2DS2-VASc score in a post-hoc analysis of more than 11,000 patients enrolled in a recent drug trial.

Overall, AFib patients in the highest tertile for genetic risk based on a 32 gene-loci test had a 31% increase rate of ischemic stroke during a median 2.8 years of follow-up compared with patients in the tertile with the lowest risk based on the 32-loci screen, Nicholas A. Marston, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. This suggested that the genetic test had roughly the same association with an increased stroke risk as several components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, such as female sex, an age of 65-74 years old, or having heart failure as a comorbidity, each of which links with an increased risk for ischemic stroke of about 31%-38%, Dr. Marston noted.

The genetic test produced even sharper discrimination among the patients with the lowest stroke risk as measured by their CHA2DS2-VASc score (Circulation. 2012 Aug 14;126[7]: 860-5). Among the slightly more than 3,000 patients in the study with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of three or less, those in the subgroup with the highest risk by the 32-loci screen had a stroke rate during follow-up that was 76% higher than those in the low or intermediate tertile for their genetic score. Among the 796 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of just 1 or 2, those who also fell into the highest level of risk on the 32-loci screen had a stroke rate 3.5-fold higher than those with a similar CHA2DS2-VASc score but in the low and intermediate tertiles by the 32-loci screen.

The additional risk prediction provided by the 32-loci test was statistically significant in the analysis of the 3,071 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or less after adjustment for age, sex, ancestry, and the individual components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which includes factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure, said Dr. Marston, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The 3.5-fold elevation among patients with a high genetic-risk score in the cohort of 796 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 or 2 just missed statistical significance (P = .06), possibly because the number of patients in the analysis was relatively low. Future research should explore the predictive value of the genetic risk score in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1, the “group where therapeutic decisions could be altered” depending on the genetic risk score, he explained.

Dr. Marston and his associates used data collected in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) trial, which was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of the direct-acting oral anticoagulant edoxaban in patients with AFib (New Engl J Med. 2013 Nov 28; 369[21]: 2091-2104). The 32-loci panel to measure a person’s genetic risk for stroke came from a 2018 report by a multinational team of researchers (Nature Genetics. 2018 Apr;50[4]: 524-37). The new analysis applied this 32-loci genetic test panel to 11.164 unrelated AFib patients with European ancestry from the ENGAGE AF-TIMIT 48 database. They divided this cohort into tertiles based on having a low, intermediate, or high stroke risk as assessed by the 32-loci genetic test. The analysis focused on patients enrolled in the trial who had European ancestry because the 32-loci screening test relied predominantly on data collected from people with this genetic background, Dr. Marston said.

SOURCE: Marston NA et al. AHA 2019, Abstract 336.

PHILADELPHIA – A 32-gene screening test for stroke risk identified a subgroup of atrial fibrillation (AFib) patients with an elevated rate of ischemic strokes despite having a low stroke risk by conventional criteria by their CHA2DS2-VASc score in a post-hoc analysis of more than 11,000 patients enrolled in a recent drug trial.

Overall, AFib patients in the highest tertile for genetic risk based on a 32 gene-loci test had a 31% increase rate of ischemic stroke during a median 2.8 years of follow-up compared with patients in the tertile with the lowest risk based on the 32-loci screen, Nicholas A. Marston, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. This suggested that the genetic test had roughly the same association with an increased stroke risk as several components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, such as female sex, an age of 65-74 years old, or having heart failure as a comorbidity, each of which links with an increased risk for ischemic stroke of about 31%-38%, Dr. Marston noted.

The genetic test produced even sharper discrimination among the patients with the lowest stroke risk as measured by their CHA2DS2-VASc score (Circulation. 2012 Aug 14;126[7]: 860-5). Among the slightly more than 3,000 patients in the study with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of three or less, those in the subgroup with the highest risk by the 32-loci screen had a stroke rate during follow-up that was 76% higher than those in the low or intermediate tertile for their genetic score. Among the 796 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of just 1 or 2, those who also fell into the highest level of risk on the 32-loci screen had a stroke rate 3.5-fold higher than those with a similar CHA2DS2-VASc score but in the low and intermediate tertiles by the 32-loci screen.

The additional risk prediction provided by the 32-loci test was statistically significant in the analysis of the 3,071 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or less after adjustment for age, sex, ancestry, and the individual components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which includes factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure, said Dr. Marston, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The 3.5-fold elevation among patients with a high genetic-risk score in the cohort of 796 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 or 2 just missed statistical significance (P = .06), possibly because the number of patients in the analysis was relatively low. Future research should explore the predictive value of the genetic risk score in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1, the “group where therapeutic decisions could be altered” depending on the genetic risk score, he explained.

Dr. Marston and his associates used data collected in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) trial, which was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of the direct-acting oral anticoagulant edoxaban in patients with AFib (New Engl J Med. 2013 Nov 28; 369[21]: 2091-2104). The 32-loci panel to measure a person’s genetic risk for stroke came from a 2018 report by a multinational team of researchers (Nature Genetics. 2018 Apr;50[4]: 524-37). The new analysis applied this 32-loci genetic test panel to 11.164 unrelated AFib patients with European ancestry from the ENGAGE AF-TIMIT 48 database. They divided this cohort into tertiles based on having a low, intermediate, or high stroke risk as assessed by the 32-loci genetic test. The analysis focused on patients enrolled in the trial who had European ancestry because the 32-loci screening test relied predominantly on data collected from people with this genetic background, Dr. Marston said.

SOURCE: Marston NA et al. AHA 2019, Abstract 336.

PHILADELPHIA – A 32-gene screening test for stroke risk identified a subgroup of atrial fibrillation (AFib) patients with an elevated rate of ischemic strokes despite having a low stroke risk by conventional criteria by their CHA2DS2-VASc score in a post-hoc analysis of more than 11,000 patients enrolled in a recent drug trial.

Overall, AFib patients in the highest tertile for genetic risk based on a 32 gene-loci test had a 31% increase rate of ischemic stroke during a median 2.8 years of follow-up compared with patients in the tertile with the lowest risk based on the 32-loci screen, Nicholas A. Marston, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions. This suggested that the genetic test had roughly the same association with an increased stroke risk as several components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, such as female sex, an age of 65-74 years old, or having heart failure as a comorbidity, each of which links with an increased risk for ischemic stroke of about 31%-38%, Dr. Marston noted.

The genetic test produced even sharper discrimination among the patients with the lowest stroke risk as measured by their CHA2DS2-VASc score (Circulation. 2012 Aug 14;126[7]: 860-5). Among the slightly more than 3,000 patients in the study with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of three or less, those in the subgroup with the highest risk by the 32-loci screen had a stroke rate during follow-up that was 76% higher than those in the low or intermediate tertile for their genetic score. Among the 796 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of just 1 or 2, those who also fell into the highest level of risk on the 32-loci screen had a stroke rate 3.5-fold higher than those with a similar CHA2DS2-VASc score but in the low and intermediate tertiles by the 32-loci screen.

The additional risk prediction provided by the 32-loci test was statistically significant in the analysis of the 3,071 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or less after adjustment for age, sex, ancestry, and the individual components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which includes factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure, said Dr. Marston, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The 3.5-fold elevation among patients with a high genetic-risk score in the cohort of 796 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 or 2 just missed statistical significance (P = .06), possibly because the number of patients in the analysis was relatively low. Future research should explore the predictive value of the genetic risk score in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1, the “group where therapeutic decisions could be altered” depending on the genetic risk score, he explained.

Dr. Marston and his associates used data collected in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48) trial, which was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of the direct-acting oral anticoagulant edoxaban in patients with AFib (New Engl J Med. 2013 Nov 28; 369[21]: 2091-2104). The 32-loci panel to measure a person’s genetic risk for stroke came from a 2018 report by a multinational team of researchers (Nature Genetics. 2018 Apr;50[4]: 524-37). The new analysis applied this 32-loci genetic test panel to 11.164 unrelated AFib patients with European ancestry from the ENGAGE AF-TIMIT 48 database. They divided this cohort into tertiles based on having a low, intermediate, or high stroke risk as assessed by the 32-loci genetic test. The analysis focused on patients enrolled in the trial who had European ancestry because the 32-loci screening test relied predominantly on data collected from people with this genetic background, Dr. Marston said.

SOURCE: Marston NA et al. AHA 2019, Abstract 336.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

Uncertain generalizability limits AFib ablation in HFrEF

Despite several reports of dramatic efficacy and reasonable safety using catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AFib) in patients with heart failure, many clinicians, including many heart failure specialists, remain skeptical about whether existing evidence supports using ablation routinely in selected heart failure patients.

Though concerns vary, one core stumbling block is inadequate confidence that the ablation outcomes reported from studies represent the benefit that the average American heart failure patient might expect to receive from ablation done outside of a study. A related issue is whether atrial fibrillation ablation in patients with heart failure is cost effective, especially at sites that did not participate in the published studies.

The first part of this article discussed the building evidence that radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AFib) can produce striking reductions in all-cause mortality of nearly 50%, and a greater than one-third cut in cardiovascular hospitalizations in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), according to one recent meta-analysis (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019 Sep;12[9]:e007414). A key question about the implications of these findings is their generalizability.

“Experience is an issue, and I agree that not every operator should do it. A common perception is that ablation doesn’t work, but that mindset is changing,” said Luigi Di Biase, MD, director of arrhythmia services at Montefiore Medical Center and professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. He noted that some apparent ablations failures happen because the treatment is used too late. “Ablation will fail if it is done too late. Think about using ablation earlier,” he advised. “The earlier you ablate, the earlier you reduce the AFib burden and the sooner the patient benefits. Ablation is a cost-effective, first-line strategy for younger patients with paroxysmal AFib. The unanswered question is whether it is cost effective for patients who have both AFib and heart failure. It may be, because in addition to the mortality benefit, there are likely savings from a lower rate of hospitalizations. A clearer picture should emerge from the cost-effectiveness analysis of CASTLE-AF.”

CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation Versus Standard Conventional Therapy in Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Atrial Fibrillation), which randomized patients with heart failure and AFib to ablation or medical management (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27), is one of the highest-profile studies reported so far showing AFib ablation’s efficacy in patients with heart failure. However, it has drawn skepticism over its generalizability because of its long enrollment period of 8 years despite running at 33 worldwide sites, and by its winnowing of 3,013 patients assessed down to the 398 actually enrolled and 363 randomized and included in the efficacy analysis.

“CASTLE-HF showed a remarkable benefit. The problem was that it took years and years to enroll the patients,” commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a heart failure specialist and chief science and medical officer of the American Heart Association in Dallas.

At the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in September 2019, French researchers reported data that supported the generalizability of the CASTLE-AF findings. The study used data collected from 252,395 patients in the French national hospital-discharge database during 2010-2018 who had diagnoses of both heart failure and AFib. Among these patients, 1,384 underwent catheter ablation and the remaining 251,011 were managed without ablation.

During a median follow-up of 537 days (about 1.5 years), the incidence of both all-cause death and heart failure hospitalization were both significantly lower in the ablated patients. The ablated patients were also much younger and were more often men, but both groups had several prevalent comorbidities at roughly similar rates. To better match the groups, the French researchers ran both a multivariate analysis, and then an even more intensively adjusting propensity-score analysis that compared the ablated patients with 1,384 closely matched patients from the nonablated group. Both analyses showed substantial incremental benefit from ablation. In the propensity score–matched analysis, ablation was linked with a relative 66% cut in all-cause death, and a relative 71% reduction in heart failure hospitalizations, compared with the patients who did not undergo ablation, reported Arnaud Bisson, MD, a cardiologist at the University of Tours (France).

Another recent assessment of the generalizability of the AFib ablation trial findings used data from nearly 184,000 U.S. patients treated for AFib during 2009-2016 in an administrative database, including more than 12,000 treated with ablation. This analysis did not take into account the coexistence of heart failure. After propensity-score matching of the ablated patients with a similar subgroup of those managed medically, the results showed a 25% relative cut in the combined primary endpoint used in the CABANA (Catheter Ablation vs. Anti-Arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation Trial) study (JAMA. 2019 Mar 15;321[134]:1261-74). Among the 74% of ablated patients who met the enrollment criteria for CABANA, the primary endpoint reduction was even greater, a 30% drop relative to matched patients who did not undergo ablation (Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 21;40[16]:1257-64).

“Professional societies are working to clarify best practices for procedural volume, outcomes, etc.,” said Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and a CABANA coinvestigator. “There are some data on ablation cost effectiveness, and they generally favor” positive cost efficacy, with more analyses now in progress,” he noted in an interview.

Many unanswered questions remain about AFib in heart failure patients and how aggressively to use ablation to treat it. Most of the data so far have come from patients with HFrEF, and so most experts consider AFib ablation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) a big unknown, although nearly 80% of the heart failure patients enrolled in CABANA (the largest randomized trial of AFib ablation with more than 2,200 patients) had left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or greater, which translates into HFpEF. Another gray area is how to think about asymptomatic (also called subclinical) AFib and whether that warrants ablation in heart failure patients. The presence or absence of symptoms is a major consideration because the traditional indication for ablation has been to reduce or eliminate symptoms like palpitations, a step that can substantially improve patients’ quality of life as well as their left ventricular function. The indication to ablate asymptomatic AFib for the purpose of improving survival and reducing hospitalizations is the new and controversial concept. Yet it has been embraced by some heart failure physicians.

“Whether or not AFib is symptomatic doesn’t matter” in a heart failure patient, said Maria Rosa Costanzo, MD, a heart failure physician at Edward Heart Hospital in Naperville, Ill. “A patient with AFib doesn’t get the atrial contribution to cardiac output. When we look deeper, a patient with ‘asymptomatic’ AFib often has symptoms, such as new fatigue or obstructive sleep apnea, so when you see a patient with asymptomatic AFib look for sleep apnea, a trigger for AFib,” Dr. Costanzo advised. “Sleep apnea, AFib, and heart failure form a triad” that often clusters in patients, and the three conditions interact in a vicious circle of reinforcing comorbidities, she said in an interview.

The cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia community clearly realizes that catheter ablation of AFib, in patients with or without heart failure, has many unaddressed questions about who should administer it and who should undergo it. In March 2019, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute held a workshop on AFib ablation. “Numerous knowledge gaps remain” about the best way to use ablation, said a summary of the workshop (Circulation. 2019 Nov 20;doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042706). Among the research needs highlighted by the workshop was “more definitive studies ... to delineate the impact of AFib ablation on outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.” The workshop recommended establishing a national U.S. registry for AFib ablations with a reliable source of funding, as well as “establishing the cause-effect relationship between ventricular dysfunction and AFib, and the potential moderating role of atrial structure and function.” The workshop also raised the possibility of sham-controlled assessments of AFib ablation, while conceding that enrollment into such trials would probably be very challenging.

The upshot is that, even while ablation advocates agree on the need for more study, clinicians are using AFib ablation on a growing number of heart failure patients (as well as on growing numbers of patients with AFib but without heart failure), with a focus on treating those who “have refractory symptoms or evidence of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy,” said Dr. Piccini. Extending that to a first-line, class I indication for heart failure patients seems to need more data, and also needs clinicians to collectively raise their comfort level with the ablation concept. If results from additional studies now underway support the dramatic efficacy and reasonable safety that’s already been seen with ablation, then increased comfort should follow.

CABANA received funding from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. CASTLE-AF was funded by Biotronik. Dr. Di Biase, Dr. Jessup, and Dr. Bisson had no disclosures. Dr. Piccini has been a consultant to Allergan, Biotronik, Medtronic, Phillips, and Sanofi Aventis; he has received research funding from Abbott, ARCA, Boston Scientific, Gilead, and Johnson & Johnson; and he had a financial relationship with GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Costanzo has been a consultant to Abbott.

This is part 2 of a 2-part story. See part 1 here.

Despite several reports of dramatic efficacy and reasonable safety using catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AFib) in patients with heart failure, many clinicians, including many heart failure specialists, remain skeptical about whether existing evidence supports using ablation routinely in selected heart failure patients.

Though concerns vary, one core stumbling block is inadequate confidence that the ablation outcomes reported from studies represent the benefit that the average American heart failure patient might expect to receive from ablation done outside of a study. A related issue is whether atrial fibrillation ablation in patients with heart failure is cost effective, especially at sites that did not participate in the published studies.

The first part of this article discussed the building evidence that radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AFib) can produce striking reductions in all-cause mortality of nearly 50%, and a greater than one-third cut in cardiovascular hospitalizations in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), according to one recent meta-analysis (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019 Sep;12[9]:e007414). A key question about the implications of these findings is their generalizability.

“Experience is an issue, and I agree that not every operator should do it. A common perception is that ablation doesn’t work, but that mindset is changing,” said Luigi Di Biase, MD, director of arrhythmia services at Montefiore Medical Center and professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. He noted that some apparent ablations failures happen because the treatment is used too late. “Ablation will fail if it is done too late. Think about using ablation earlier,” he advised. “The earlier you ablate, the earlier you reduce the AFib burden and the sooner the patient benefits. Ablation is a cost-effective, first-line strategy for younger patients with paroxysmal AFib. The unanswered question is whether it is cost effective for patients who have both AFib and heart failure. It may be, because in addition to the mortality benefit, there are likely savings from a lower rate of hospitalizations. A clearer picture should emerge from the cost-effectiveness analysis of CASTLE-AF.”

CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation Versus Standard Conventional Therapy in Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Atrial Fibrillation), which randomized patients with heart failure and AFib to ablation or medical management (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27), is one of the highest-profile studies reported so far showing AFib ablation’s efficacy in patients with heart failure. However, it has drawn skepticism over its generalizability because of its long enrollment period of 8 years despite running at 33 worldwide sites, and by its winnowing of 3,013 patients assessed down to the 398 actually enrolled and 363 randomized and included in the efficacy analysis.

“CASTLE-HF showed a remarkable benefit. The problem was that it took years and years to enroll the patients,” commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a heart failure specialist and chief science and medical officer of the American Heart Association in Dallas.

At the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in September 2019, French researchers reported data that supported the generalizability of the CASTLE-AF findings. The study used data collected from 252,395 patients in the French national hospital-discharge database during 2010-2018 who had diagnoses of both heart failure and AFib. Among these patients, 1,384 underwent catheter ablation and the remaining 251,011 were managed without ablation.

During a median follow-up of 537 days (about 1.5 years), the incidence of both all-cause death and heart failure hospitalization were both significantly lower in the ablated patients. The ablated patients were also much younger and were more often men, but both groups had several prevalent comorbidities at roughly similar rates. To better match the groups, the French researchers ran both a multivariate analysis, and then an even more intensively adjusting propensity-score analysis that compared the ablated patients with 1,384 closely matched patients from the nonablated group. Both analyses showed substantial incremental benefit from ablation. In the propensity score–matched analysis, ablation was linked with a relative 66% cut in all-cause death, and a relative 71% reduction in heart failure hospitalizations, compared with the patients who did not undergo ablation, reported Arnaud Bisson, MD, a cardiologist at the University of Tours (France).

Another recent assessment of the generalizability of the AFib ablation trial findings used data from nearly 184,000 U.S. patients treated for AFib during 2009-2016 in an administrative database, including more than 12,000 treated with ablation. This analysis did not take into account the coexistence of heart failure. After propensity-score matching of the ablated patients with a similar subgroup of those managed medically, the results showed a 25% relative cut in the combined primary endpoint used in the CABANA (Catheter Ablation vs. Anti-Arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation Trial) study (JAMA. 2019 Mar 15;321[134]:1261-74). Among the 74% of ablated patients who met the enrollment criteria for CABANA, the primary endpoint reduction was even greater, a 30% drop relative to matched patients who did not undergo ablation (Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 21;40[16]:1257-64).

“Professional societies are working to clarify best practices for procedural volume, outcomes, etc.,” said Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and a CABANA coinvestigator. “There are some data on ablation cost effectiveness, and they generally favor” positive cost efficacy, with more analyses now in progress,” he noted in an interview.

Many unanswered questions remain about AFib in heart failure patients and how aggressively to use ablation to treat it. Most of the data so far have come from patients with HFrEF, and so most experts consider AFib ablation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) a big unknown, although nearly 80% of the heart failure patients enrolled in CABANA (the largest randomized trial of AFib ablation with more than 2,200 patients) had left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or greater, which translates into HFpEF. Another gray area is how to think about asymptomatic (also called subclinical) AFib and whether that warrants ablation in heart failure patients. The presence or absence of symptoms is a major consideration because the traditional indication for ablation has been to reduce or eliminate symptoms like palpitations, a step that can substantially improve patients’ quality of life as well as their left ventricular function. The indication to ablate asymptomatic AFib for the purpose of improving survival and reducing hospitalizations is the new and controversial concept. Yet it has been embraced by some heart failure physicians.

“Whether or not AFib is symptomatic doesn’t matter” in a heart failure patient, said Maria Rosa Costanzo, MD, a heart failure physician at Edward Heart Hospital in Naperville, Ill. “A patient with AFib doesn’t get the atrial contribution to cardiac output. When we look deeper, a patient with ‘asymptomatic’ AFib often has symptoms, such as new fatigue or obstructive sleep apnea, so when you see a patient with asymptomatic AFib look for sleep apnea, a trigger for AFib,” Dr. Costanzo advised. “Sleep apnea, AFib, and heart failure form a triad” that often clusters in patients, and the three conditions interact in a vicious circle of reinforcing comorbidities, she said in an interview.

The cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia community clearly realizes that catheter ablation of AFib, in patients with or without heart failure, has many unaddressed questions about who should administer it and who should undergo it. In March 2019, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute held a workshop on AFib ablation. “Numerous knowledge gaps remain” about the best way to use ablation, said a summary of the workshop (Circulation. 2019 Nov 20;doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042706). Among the research needs highlighted by the workshop was “more definitive studies ... to delineate the impact of AFib ablation on outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.” The workshop recommended establishing a national U.S. registry for AFib ablations with a reliable source of funding, as well as “establishing the cause-effect relationship between ventricular dysfunction and AFib, and the potential moderating role of atrial structure and function.” The workshop also raised the possibility of sham-controlled assessments of AFib ablation, while conceding that enrollment into such trials would probably be very challenging.

The upshot is that, even while ablation advocates agree on the need for more study, clinicians are using AFib ablation on a growing number of heart failure patients (as well as on growing numbers of patients with AFib but without heart failure), with a focus on treating those who “have refractory symptoms or evidence of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy,” said Dr. Piccini. Extending that to a first-line, class I indication for heart failure patients seems to need more data, and also needs clinicians to collectively raise their comfort level with the ablation concept. If results from additional studies now underway support the dramatic efficacy and reasonable safety that’s already been seen with ablation, then increased comfort should follow.

CABANA received funding from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. CASTLE-AF was funded by Biotronik. Dr. Di Biase, Dr. Jessup, and Dr. Bisson had no disclosures. Dr. Piccini has been a consultant to Allergan, Biotronik, Medtronic, Phillips, and Sanofi Aventis; he has received research funding from Abbott, ARCA, Boston Scientific, Gilead, and Johnson & Johnson; and he had a financial relationship with GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Costanzo has been a consultant to Abbott.

This is part 2 of a 2-part story. See part 1 here.

Despite several reports of dramatic efficacy and reasonable safety using catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AFib) in patients with heart failure, many clinicians, including many heart failure specialists, remain skeptical about whether existing evidence supports using ablation routinely in selected heart failure patients.

Though concerns vary, one core stumbling block is inadequate confidence that the ablation outcomes reported from studies represent the benefit that the average American heart failure patient might expect to receive from ablation done outside of a study. A related issue is whether atrial fibrillation ablation in patients with heart failure is cost effective, especially at sites that did not participate in the published studies.

The first part of this article discussed the building evidence that radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AFib) can produce striking reductions in all-cause mortality of nearly 50%, and a greater than one-third cut in cardiovascular hospitalizations in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), according to one recent meta-analysis (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019 Sep;12[9]:e007414). A key question about the implications of these findings is their generalizability.

“Experience is an issue, and I agree that not every operator should do it. A common perception is that ablation doesn’t work, but that mindset is changing,” said Luigi Di Biase, MD, director of arrhythmia services at Montefiore Medical Center and professor of medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. He noted that some apparent ablations failures happen because the treatment is used too late. “Ablation will fail if it is done too late. Think about using ablation earlier,” he advised. “The earlier you ablate, the earlier you reduce the AFib burden and the sooner the patient benefits. Ablation is a cost-effective, first-line strategy for younger patients with paroxysmal AFib. The unanswered question is whether it is cost effective for patients who have both AFib and heart failure. It may be, because in addition to the mortality benefit, there are likely savings from a lower rate of hospitalizations. A clearer picture should emerge from the cost-effectiveness analysis of CASTLE-AF.”

CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation Versus Standard Conventional Therapy in Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Atrial Fibrillation), which randomized patients with heart failure and AFib to ablation or medical management (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27), is one of the highest-profile studies reported so far showing AFib ablation’s efficacy in patients with heart failure. However, it has drawn skepticism over its generalizability because of its long enrollment period of 8 years despite running at 33 worldwide sites, and by its winnowing of 3,013 patients assessed down to the 398 actually enrolled and 363 randomized and included in the efficacy analysis.

“CASTLE-HF showed a remarkable benefit. The problem was that it took years and years to enroll the patients,” commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a heart failure specialist and chief science and medical officer of the American Heart Association in Dallas.

At the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in September 2019, French researchers reported data that supported the generalizability of the CASTLE-AF findings. The study used data collected from 252,395 patients in the French national hospital-discharge database during 2010-2018 who had diagnoses of both heart failure and AFib. Among these patients, 1,384 underwent catheter ablation and the remaining 251,011 were managed without ablation.

During a median follow-up of 537 days (about 1.5 years), the incidence of both all-cause death and heart failure hospitalization were both significantly lower in the ablated patients. The ablated patients were also much younger and were more often men, but both groups had several prevalent comorbidities at roughly similar rates. To better match the groups, the French researchers ran both a multivariate analysis, and then an even more intensively adjusting propensity-score analysis that compared the ablated patients with 1,384 closely matched patients from the nonablated group. Both analyses showed substantial incremental benefit from ablation. In the propensity score–matched analysis, ablation was linked with a relative 66% cut in all-cause death, and a relative 71% reduction in heart failure hospitalizations, compared with the patients who did not undergo ablation, reported Arnaud Bisson, MD, a cardiologist at the University of Tours (France).

Another recent assessment of the generalizability of the AFib ablation trial findings used data from nearly 184,000 U.S. patients treated for AFib during 2009-2016 in an administrative database, including more than 12,000 treated with ablation. This analysis did not take into account the coexistence of heart failure. After propensity-score matching of the ablated patients with a similar subgroup of those managed medically, the results showed a 25% relative cut in the combined primary endpoint used in the CABANA (Catheter Ablation vs. Anti-Arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation Trial) study (JAMA. 2019 Mar 15;321[134]:1261-74). Among the 74% of ablated patients who met the enrollment criteria for CABANA, the primary endpoint reduction was even greater, a 30% drop relative to matched patients who did not undergo ablation (Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 21;40[16]:1257-64).

“Professional societies are working to clarify best practices for procedural volume, outcomes, etc.,” said Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and a CABANA coinvestigator. “There are some data on ablation cost effectiveness, and they generally favor” positive cost efficacy, with more analyses now in progress,” he noted in an interview.

Many unanswered questions remain about AFib in heart failure patients and how aggressively to use ablation to treat it. Most of the data so far have come from patients with HFrEF, and so most experts consider AFib ablation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) a big unknown, although nearly 80% of the heart failure patients enrolled in CABANA (the largest randomized trial of AFib ablation with more than 2,200 patients) had left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or greater, which translates into HFpEF. Another gray area is how to think about asymptomatic (also called subclinical) AFib and whether that warrants ablation in heart failure patients. The presence or absence of symptoms is a major consideration because the traditional indication for ablation has been to reduce or eliminate symptoms like palpitations, a step that can substantially improve patients’ quality of life as well as their left ventricular function. The indication to ablate asymptomatic AFib for the purpose of improving survival and reducing hospitalizations is the new and controversial concept. Yet it has been embraced by some heart failure physicians.

“Whether or not AFib is symptomatic doesn’t matter” in a heart failure patient, said Maria Rosa Costanzo, MD, a heart failure physician at Edward Heart Hospital in Naperville, Ill. “A patient with AFib doesn’t get the atrial contribution to cardiac output. When we look deeper, a patient with ‘asymptomatic’ AFib often has symptoms, such as new fatigue or obstructive sleep apnea, so when you see a patient with asymptomatic AFib look for sleep apnea, a trigger for AFib,” Dr. Costanzo advised. “Sleep apnea, AFib, and heart failure form a triad” that often clusters in patients, and the three conditions interact in a vicious circle of reinforcing comorbidities, she said in an interview.

The cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia community clearly realizes that catheter ablation of AFib, in patients with or without heart failure, has many unaddressed questions about who should administer it and who should undergo it. In March 2019, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute held a workshop on AFib ablation. “Numerous knowledge gaps remain” about the best way to use ablation, said a summary of the workshop (Circulation. 2019 Nov 20;doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042706). Among the research needs highlighted by the workshop was “more definitive studies ... to delineate the impact of AFib ablation on outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.” The workshop recommended establishing a national U.S. registry for AFib ablations with a reliable source of funding, as well as “establishing the cause-effect relationship between ventricular dysfunction and AFib, and the potential moderating role of atrial structure and function.” The workshop also raised the possibility of sham-controlled assessments of AFib ablation, while conceding that enrollment into such trials would probably be very challenging.

The upshot is that, even while ablation advocates agree on the need for more study, clinicians are using AFib ablation on a growing number of heart failure patients (as well as on growing numbers of patients with AFib but without heart failure), with a focus on treating those who “have refractory symptoms or evidence of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy,” said Dr. Piccini. Extending that to a first-line, class I indication for heart failure patients seems to need more data, and also needs clinicians to collectively raise their comfort level with the ablation concept. If results from additional studies now underway support the dramatic efficacy and reasonable safety that’s already been seen with ablation, then increased comfort should follow.

CABANA received funding from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. CASTLE-AF was funded by Biotronik. Dr. Di Biase, Dr. Jessup, and Dr. Bisson had no disclosures. Dr. Piccini has been a consultant to Allergan, Biotronik, Medtronic, Phillips, and Sanofi Aventis; he has received research funding from Abbott, ARCA, Boston Scientific, Gilead, and Johnson & Johnson; and he had a financial relationship with GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Costanzo has been a consultant to Abbott.

This is part 2 of a 2-part story. See part 1 here.

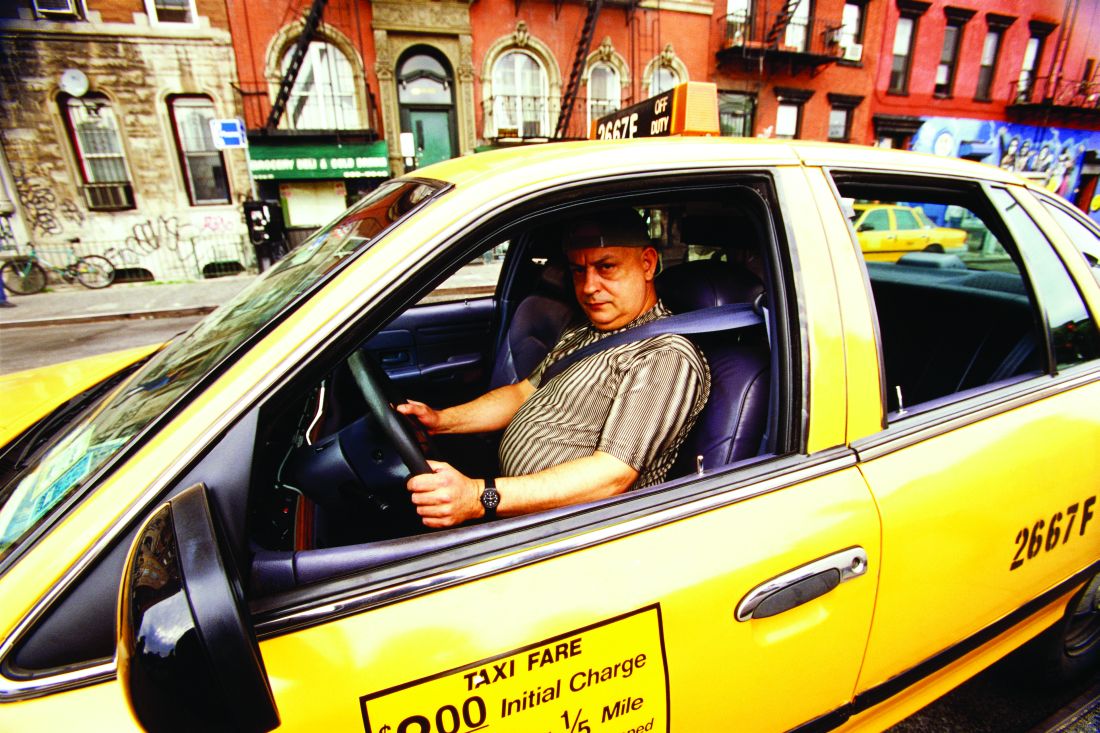

Cardiac arrests peak with pollution in Japan

PHILADELPHIA – Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests spike with daily counts of emissions-related particulate matter – a key contributor to urban smog – and particularly affect men and people older than age 75, according to results of a nationwide Japanese study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Short-term exposure to particulate pollutants is a potential trigger for cardiac-origin, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest [OHCA] onset in Japan,” said Sunao Kojima, MD, a professor at Kawasaki Medical School in Kurashiki, Japan.

The study used the All-Japan Utstein Registry of OHCA throughout all 47 prefectures in Japan. The analysis then applied prefecture-specific estimates of PM2.5 – particulate matter that measures 2.5 mcm in average diameter – using a time-stratified, case-crossover design. By comparison, PM2.5 is about 1/40th the diameter of human hair (approximately 100 mcm) and about 1/12th that of cedar pollen (30 mcm).

“Increased OHCAs incidence correlated with the average increase in PM2.5 concentrations over those observed 1 day before cardiac arrest,” Dr. Kojima said.

What’s noteworthy about the Utstein registry, Dr. Kojima said, is that emergency medical service personnel in Japan are not authorized to terminate resuscitation efforts, so most OHCA patients are transported to the nearest hospital and are thus counted in the registry.

From a total count of 1.4 million EMS-assessed OHCAs from 2005 through 2016, the study focused on 103,189 bystander-witnessed events from April 2011 through 2016. The analysis further divided that population into three groups: those presenting with initial ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia (20,848); those without initial VF/pulseless VT (80,110); and those with initial cardiac rhythm of unknown origin (2,231).

“The pathways linking PM2.5 exposure with OHCA remain unknown, but several mechanisms have been suspected,” Dr. Kojima said. “A major mechanism is thought to be associated with oxidative stress and systemic inflammation.”

The average daily concentration for PM2.5 was 13.9/m3 across all of Japan, Dr. Kojima said, with the highest concentrations in western Japan (16.3/m3). A 10-mcg/m3 increase in the average PM2.5 concentrations on the day of OHCA from the previous day (lag 0-1) was associated with a 1.6% increase in OHCAs (95% confidence interval, 0.1-3.1%), he said.

“Increased PM2.5 concentrations were closely associated with OHCA incidence, even when adjusted for other pollutants, such as ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and lag 0-1,” Dr. Kojima said.

The incidence for PM2.5-related OHCA was higher for people age 75 and older and for men, during the warm season and in the central region. In the central region, the incidence increased around 6% for every 10-mcg/m3 day-to-day increase in the average PM2.5 compared to less than 1% increases in the eastern and western regions, Dr. Kojima said.

PM2.5 levels also seemed to influence outcomes depending on the origin of the OHCA, he said. Patients with VF/pulseless VT and pulseless electrical activity had better outcomes than did those with asystole. Increased PM2.5 levels were linked with lower rates of restoration of spontaneous circulation, 1-month survival, and 1-month survival with minimal neurological impairment, he said. Patients who had chest-compression-only CPR seemed to do significantly better than did those who had chest compression with rescue breathing, he said.

“There may be room for further discussion regarding the impact of performing rescue breathing in CPR and the consequent effects of short-term PM2.5 exposure on patients with cardiac origin,” he said.

Dr. Kojima has no financial relationships to disclose. The study received funding from the Japan Ministry of the Environment, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and Foundation for Total Health Promotion, Japan.

SOURCE: Kojima S. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.F1.

PHILADELPHIA – Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests spike with daily counts of emissions-related particulate matter – a key contributor to urban smog – and particularly affect men and people older than age 75, according to results of a nationwide Japanese study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Short-term exposure to particulate pollutants is a potential trigger for cardiac-origin, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest [OHCA] onset in Japan,” said Sunao Kojima, MD, a professor at Kawasaki Medical School in Kurashiki, Japan.

The study used the All-Japan Utstein Registry of OHCA throughout all 47 prefectures in Japan. The analysis then applied prefecture-specific estimates of PM2.5 – particulate matter that measures 2.5 mcm in average diameter – using a time-stratified, case-crossover design. By comparison, PM2.5 is about 1/40th the diameter of human hair (approximately 100 mcm) and about 1/12th that of cedar pollen (30 mcm).

“Increased OHCAs incidence correlated with the average increase in PM2.5 concentrations over those observed 1 day before cardiac arrest,” Dr. Kojima said.

What’s noteworthy about the Utstein registry, Dr. Kojima said, is that emergency medical service personnel in Japan are not authorized to terminate resuscitation efforts, so most OHCA patients are transported to the nearest hospital and are thus counted in the registry.

From a total count of 1.4 million EMS-assessed OHCAs from 2005 through 2016, the study focused on 103,189 bystander-witnessed events from April 2011 through 2016. The analysis further divided that population into three groups: those presenting with initial ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia (20,848); those without initial VF/pulseless VT (80,110); and those with initial cardiac rhythm of unknown origin (2,231).

“The pathways linking PM2.5 exposure with OHCA remain unknown, but several mechanisms have been suspected,” Dr. Kojima said. “A major mechanism is thought to be associated with oxidative stress and systemic inflammation.”

The average daily concentration for PM2.5 was 13.9/m3 across all of Japan, Dr. Kojima said, with the highest concentrations in western Japan (16.3/m3). A 10-mcg/m3 increase in the average PM2.5 concentrations on the day of OHCA from the previous day (lag 0-1) was associated with a 1.6% increase in OHCAs (95% confidence interval, 0.1-3.1%), he said.

“Increased PM2.5 concentrations were closely associated with OHCA incidence, even when adjusted for other pollutants, such as ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and lag 0-1,” Dr. Kojima said.

The incidence for PM2.5-related OHCA was higher for people age 75 and older and for men, during the warm season and in the central region. In the central region, the incidence increased around 6% for every 10-mcg/m3 day-to-day increase in the average PM2.5 compared to less than 1% increases in the eastern and western regions, Dr. Kojima said.

PM2.5 levels also seemed to influence outcomes depending on the origin of the OHCA, he said. Patients with VF/pulseless VT and pulseless electrical activity had better outcomes than did those with asystole. Increased PM2.5 levels were linked with lower rates of restoration of spontaneous circulation, 1-month survival, and 1-month survival with minimal neurological impairment, he said. Patients who had chest-compression-only CPR seemed to do significantly better than did those who had chest compression with rescue breathing, he said.

“There may be room for further discussion regarding the impact of performing rescue breathing in CPR and the consequent effects of short-term PM2.5 exposure on patients with cardiac origin,” he said.

Dr. Kojima has no financial relationships to disclose. The study received funding from the Japan Ministry of the Environment, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and Foundation for Total Health Promotion, Japan.

SOURCE: Kojima S. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.F1.

PHILADELPHIA – Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests spike with daily counts of emissions-related particulate matter – a key contributor to urban smog – and particularly affect men and people older than age 75, according to results of a nationwide Japanese study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Short-term exposure to particulate pollutants is a potential trigger for cardiac-origin, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest [OHCA] onset in Japan,” said Sunao Kojima, MD, a professor at Kawasaki Medical School in Kurashiki, Japan.

The study used the All-Japan Utstein Registry of OHCA throughout all 47 prefectures in Japan. The analysis then applied prefecture-specific estimates of PM2.5 – particulate matter that measures 2.5 mcm in average diameter – using a time-stratified, case-crossover design. By comparison, PM2.5 is about 1/40th the diameter of human hair (approximately 100 mcm) and about 1/12th that of cedar pollen (30 mcm).

“Increased OHCAs incidence correlated with the average increase in PM2.5 concentrations over those observed 1 day before cardiac arrest,” Dr. Kojima said.

What’s noteworthy about the Utstein registry, Dr. Kojima said, is that emergency medical service personnel in Japan are not authorized to terminate resuscitation efforts, so most OHCA patients are transported to the nearest hospital and are thus counted in the registry.

From a total count of 1.4 million EMS-assessed OHCAs from 2005 through 2016, the study focused on 103,189 bystander-witnessed events from April 2011 through 2016. The analysis further divided that population into three groups: those presenting with initial ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia (20,848); those without initial VF/pulseless VT (80,110); and those with initial cardiac rhythm of unknown origin (2,231).

“The pathways linking PM2.5 exposure with OHCA remain unknown, but several mechanisms have been suspected,” Dr. Kojima said. “A major mechanism is thought to be associated with oxidative stress and systemic inflammation.”

The average daily concentration for PM2.5 was 13.9/m3 across all of Japan, Dr. Kojima said, with the highest concentrations in western Japan (16.3/m3). A 10-mcg/m3 increase in the average PM2.5 concentrations on the day of OHCA from the previous day (lag 0-1) was associated with a 1.6% increase in OHCAs (95% confidence interval, 0.1-3.1%), he said.

“Increased PM2.5 concentrations were closely associated with OHCA incidence, even when adjusted for other pollutants, such as ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and lag 0-1,” Dr. Kojima said.

The incidence for PM2.5-related OHCA was higher for people age 75 and older and for men, during the warm season and in the central region. In the central region, the incidence increased around 6% for every 10-mcg/m3 day-to-day increase in the average PM2.5 compared to less than 1% increases in the eastern and western regions, Dr. Kojima said.

PM2.5 levels also seemed to influence outcomes depending on the origin of the OHCA, he said. Patients with VF/pulseless VT and pulseless electrical activity had better outcomes than did those with asystole. Increased PM2.5 levels were linked with lower rates of restoration of spontaneous circulation, 1-month survival, and 1-month survival with minimal neurological impairment, he said. Patients who had chest-compression-only CPR seemed to do significantly better than did those who had chest compression with rescue breathing, he said.

“There may be room for further discussion regarding the impact of performing rescue breathing in CPR and the consequent effects of short-term PM2.5 exposure on patients with cardiac origin,” he said.

Dr. Kojima has no financial relationships to disclose. The study received funding from the Japan Ministry of the Environment, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and Foundation for Total Health Promotion, Japan.

SOURCE: Kojima S. AHA 2019, Session FS.AOS.F1.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

Evidence builds for AFib ablation’s efficacy in heart failure

Roughly a third of patients with heart failure also have atrial fibrillation, a comorbid combination notorious for working synergistically to worsen a patient’s quality of life and life expectancy.

During the past year, radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with both conditions has gathered steam as a way to intervene in at least selected patients, driven by study results that featured attention-grabbing reductions in death and cardiovascular hospitalizations.

The evidence favoring catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation (AFib) in patients with heart failure, particularly patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), ramped up in 2019, spurred largely by a subgroup analysis from the CABANA trial, the largest randomized comparison by far of AFib ablation with antiarrhythmic drug treatment with 2,204 patients.

The past few months also featured release of two meta-analyses that took the CABANA results into account plus findings from about a dozen earlier randomized studies. Both meta-analyses, as well as the heart failure analysis from CABANA, all point in one direction, as stated in the conclusion of one of the meta-analyses: “In patients with AFib, catheter ablation is associated with all-cause mortality benefit, compared with medical therapy, that is driven by patients with AFib and HFrEF. Catheter ablation is safe and reduces cardiovascular hospitalizations and recurrences of atrial arrhythmias” both in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AFib,” wrote Stavros Stavrakis, MD, and his associates in their systematic review of 18 randomized, controlled trials of catheter ablation of AFib in a total of 4,464 patients with or without heart failure (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019 Sep;12[9]: e007414).

Despite these new data and analyses, clinicians seem to have very mixed reactions. Some call for an upgraded recommendation by professional societies that would support more aggressive use of AFib ablation in heart failure patients, and the anecdotal impressions of people who manage these patients are that ablation procedures have recently increased. But others advise caution, and note that in their opinion the efficacy data remain preliminary; the procedure has safety, logistical, and economic concerns; and questions remain about the ability of all active ablation programs to consistently deliver the results seen in published trials.

The meta-analysis led by Dr. Stavrakis showed that catheter ablation of AFib cut all-cause mortality during follow-up by a statistically significant 31%, compared with medical therapy, in all patients regardless of their heart failure status. But in patients with HFrEF, the reduction was 48%, along with a 38% cut in cardiovascular hospitalizations. In contrast, patients without heart failure who underwent AFib ablation showed no significant change in their all-cause mortality, compared with medical management of these patients.

“Based both on our meta-analysis and the CABANA data, patients with AFib most likely to benefit from ablation are patients younger than 65 and those with heart failure,” summed up Dr. Stavrakis, a cardiac electrophysiologist at the Heart Rhythm Institute of the University of Oklahoma in Oklahoma City.

The second meta-analysis, which initially appeared in July, analyzed data from 11 randomized trials of catheter ablations compared with anti-arrhythmic medical therapy for rate or rhythm control with in a total of 3,598 patients who all had heart failure, again including the patients enrolled in the CABANA study. The results showed a significant 49% relative drop in all cause mortality with ablation compared with medical treatment, and a statistically significant 56% cut in hospitalizations, as well as a significant, nearly 7% average, absolute improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction, plus benefits for preventing arrhythmia recurrence and improving quality of life (Eur Heart J. 2019 Jul 11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz443).