User login

Some household pets found to be colonized with S. aureus

SAN DIEGO – In households of children with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, pet dogs and cats often were colonized with S. aureus. In addition, the S. aureus strains colonizing the pets were likely to be concordant with those found on humans and/or their environmental surfaces within the household.

Those are key findings from a study that set out to determine the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus colonization of pets in the context of their human contacts and household environments, in households of children with community-associated MRSA infections.

“S. aureus is a significant pathogen in both health care and community settings and causes a spectrum of infections ranging from superficial skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) to invasive, life-threatening infections,” Ryley M. Thompson said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Due to the enormous clinical and economic burden posed by S. aureus, transmission prevention is essential.”

According to traditional dogma, “humans are the source of S. aureus for their pets and … pets are not a natural reservoir for S. aureus,” said Mr. Thompson, a clinical research study assistant in the Clinical and Translational Research Laboratory of Dr. Stephanie Fritz in the department of pediatrics at Washington University, St. Louis. “This is supported by the fact that pets often clear colonization without antimicrobial treatment. Risk factors for pet colonization include veterinary health care contact, contact with children, and using their mouths to interact with their environment. To date, directionality of S. aureus transmission between humans and pets is unclear.”

Between 2012 and 2015, the researchers enrolled 100 households of children with active or recent community-associated MRSA SSTIs who had been treated at St. Louis Children’s Hospital or other pediatric practices in the area. Over the course of 1 year, five study visits were conducted in each of the patient’s homes. Every 3 months, cultures were obtained from index patients and their household contacts, indoor dogs and cats, and 21 household environmental surfaces. The index patients and household contacts were swabbed at their axillae, nares, and inguinal folds; indoor dogs and cats were swabbed at their nares and dorsal fur; and household surfaces thought to be frequently touched by multiple household members were swabbed, such as TV remote controls, refrigerator door handles, and toilet seats. Researchers also administered a detailed survey to evaluate health, hygiene, and activities that may be associated with S. aureus infection transmission.

Molecular typing of all S. aureus strains was performed by repetitive-sequence polymerase chain reaction to determine strain relatedness, and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) characterization was performed by multiplex PCR.

Of 100 households, 49 had a total of 89 pets: 63 dogs and 26 cats. Of the 63 dogs, 13 (21%) were colonized with S. aureus (9 with MRSA) and 2 of 26 cats (8%) were colonized with MRSA. Eleven isolates were SCCmec type IV (MRSA), one was type II (MRSA), and two were type III (MRSA). At baseline, the researchers recovered 16 S. aureus isolates from 15 pets: 13 from the nares and 3 from pet dorsal fur.

One dog was colonized at both sites with concordant strains. In the three households that had two colonized pets, one household had two colonized dogs with matching strain types, the second had two dogs with nonmatching strain types, and the third had a dog and a cat with nonmatching strain types, Mr. Thompson reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Pet characteristics significantly associated with S. aureus colonization at study enrollment were older age (P = .04) and advanced number of years living in the home (P = .03), but sleeping in the same bed as a household member was not (P =. 96).

Molecular analysis revealed that the primary caretaker for 10 of the 15 colonized pets (67%) also was colonized with S. aureus, and 70% of these strains were concordant with the pet strain. In addition, seven of eight humans (88%) who shared a bed with a colonized pet also were colonized with S. aureus, and 43% of these strains were concordant with the pet strain.

Mr. Thompson also presented the longitudinal molecular epidemiology results in pets. In this analysis, 37 of the 89 pets were colonized with S. aureus at some point over the period of 12 months. Of these, 24 were colonized just once, while 13 were colonized at more than one of the samplings over time. Among these 13, two (15%) had concordant strains at all samplings, five (39%) had concordant and discordant strains, and six (46%) had discordant strains over the longitudinal study period.

Mr. Thompson and his associates intend to complete enrollment and analysis of 150 households in a 2-year longitudinal study. After this, he said, “we will be able to determine the directionality of human-pet S. aureus transmission as well as define the role of pets in S. aureus household transmission dynamics.”

The study was funded by the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – In households of children with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, pet dogs and cats often were colonized with S. aureus. In addition, the S. aureus strains colonizing the pets were likely to be concordant with those found on humans and/or their environmental surfaces within the household.

Those are key findings from a study that set out to determine the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus colonization of pets in the context of their human contacts and household environments, in households of children with community-associated MRSA infections.

“S. aureus is a significant pathogen in both health care and community settings and causes a spectrum of infections ranging from superficial skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) to invasive, life-threatening infections,” Ryley M. Thompson said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Due to the enormous clinical and economic burden posed by S. aureus, transmission prevention is essential.”

According to traditional dogma, “humans are the source of S. aureus for their pets and … pets are not a natural reservoir for S. aureus,” said Mr. Thompson, a clinical research study assistant in the Clinical and Translational Research Laboratory of Dr. Stephanie Fritz in the department of pediatrics at Washington University, St. Louis. “This is supported by the fact that pets often clear colonization without antimicrobial treatment. Risk factors for pet colonization include veterinary health care contact, contact with children, and using their mouths to interact with their environment. To date, directionality of S. aureus transmission between humans and pets is unclear.”

Between 2012 and 2015, the researchers enrolled 100 households of children with active or recent community-associated MRSA SSTIs who had been treated at St. Louis Children’s Hospital or other pediatric practices in the area. Over the course of 1 year, five study visits were conducted in each of the patient’s homes. Every 3 months, cultures were obtained from index patients and their household contacts, indoor dogs and cats, and 21 household environmental surfaces. The index patients and household contacts were swabbed at their axillae, nares, and inguinal folds; indoor dogs and cats were swabbed at their nares and dorsal fur; and household surfaces thought to be frequently touched by multiple household members were swabbed, such as TV remote controls, refrigerator door handles, and toilet seats. Researchers also administered a detailed survey to evaluate health, hygiene, and activities that may be associated with S. aureus infection transmission.

Molecular typing of all S. aureus strains was performed by repetitive-sequence polymerase chain reaction to determine strain relatedness, and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) characterization was performed by multiplex PCR.

Of 100 households, 49 had a total of 89 pets: 63 dogs and 26 cats. Of the 63 dogs, 13 (21%) were colonized with S. aureus (9 with MRSA) and 2 of 26 cats (8%) were colonized with MRSA. Eleven isolates were SCCmec type IV (MRSA), one was type II (MRSA), and two were type III (MRSA). At baseline, the researchers recovered 16 S. aureus isolates from 15 pets: 13 from the nares and 3 from pet dorsal fur.

One dog was colonized at both sites with concordant strains. In the three households that had two colonized pets, one household had two colonized dogs with matching strain types, the second had two dogs with nonmatching strain types, and the third had a dog and a cat with nonmatching strain types, Mr. Thompson reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Pet characteristics significantly associated with S. aureus colonization at study enrollment were older age (P = .04) and advanced number of years living in the home (P = .03), but sleeping in the same bed as a household member was not (P =. 96).

Molecular analysis revealed that the primary caretaker for 10 of the 15 colonized pets (67%) also was colonized with S. aureus, and 70% of these strains were concordant with the pet strain. In addition, seven of eight humans (88%) who shared a bed with a colonized pet also were colonized with S. aureus, and 43% of these strains were concordant with the pet strain.

Mr. Thompson also presented the longitudinal molecular epidemiology results in pets. In this analysis, 37 of the 89 pets were colonized with S. aureus at some point over the period of 12 months. Of these, 24 were colonized just once, while 13 were colonized at more than one of the samplings over time. Among these 13, two (15%) had concordant strains at all samplings, five (39%) had concordant and discordant strains, and six (46%) had discordant strains over the longitudinal study period.

Mr. Thompson and his associates intend to complete enrollment and analysis of 150 households in a 2-year longitudinal study. After this, he said, “we will be able to determine the directionality of human-pet S. aureus transmission as well as define the role of pets in S. aureus household transmission dynamics.”

The study was funded by the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – In households of children with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, pet dogs and cats often were colonized with S. aureus. In addition, the S. aureus strains colonizing the pets were likely to be concordant with those found on humans and/or their environmental surfaces within the household.

Those are key findings from a study that set out to determine the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus colonization of pets in the context of their human contacts and household environments, in households of children with community-associated MRSA infections.

“S. aureus is a significant pathogen in both health care and community settings and causes a spectrum of infections ranging from superficial skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) to invasive, life-threatening infections,” Ryley M. Thompson said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Due to the enormous clinical and economic burden posed by S. aureus, transmission prevention is essential.”

According to traditional dogma, “humans are the source of S. aureus for their pets and … pets are not a natural reservoir for S. aureus,” said Mr. Thompson, a clinical research study assistant in the Clinical and Translational Research Laboratory of Dr. Stephanie Fritz in the department of pediatrics at Washington University, St. Louis. “This is supported by the fact that pets often clear colonization without antimicrobial treatment. Risk factors for pet colonization include veterinary health care contact, contact with children, and using their mouths to interact with their environment. To date, directionality of S. aureus transmission between humans and pets is unclear.”

Between 2012 and 2015, the researchers enrolled 100 households of children with active or recent community-associated MRSA SSTIs who had been treated at St. Louis Children’s Hospital or other pediatric practices in the area. Over the course of 1 year, five study visits were conducted in each of the patient’s homes. Every 3 months, cultures were obtained from index patients and their household contacts, indoor dogs and cats, and 21 household environmental surfaces. The index patients and household contacts were swabbed at their axillae, nares, and inguinal folds; indoor dogs and cats were swabbed at their nares and dorsal fur; and household surfaces thought to be frequently touched by multiple household members were swabbed, such as TV remote controls, refrigerator door handles, and toilet seats. Researchers also administered a detailed survey to evaluate health, hygiene, and activities that may be associated with S. aureus infection transmission.

Molecular typing of all S. aureus strains was performed by repetitive-sequence polymerase chain reaction to determine strain relatedness, and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) characterization was performed by multiplex PCR.

Of 100 households, 49 had a total of 89 pets: 63 dogs and 26 cats. Of the 63 dogs, 13 (21%) were colonized with S. aureus (9 with MRSA) and 2 of 26 cats (8%) were colonized with MRSA. Eleven isolates were SCCmec type IV (MRSA), one was type II (MRSA), and two were type III (MRSA). At baseline, the researchers recovered 16 S. aureus isolates from 15 pets: 13 from the nares and 3 from pet dorsal fur.

One dog was colonized at both sites with concordant strains. In the three households that had two colonized pets, one household had two colonized dogs with matching strain types, the second had two dogs with nonmatching strain types, and the third had a dog and a cat with nonmatching strain types, Mr. Thompson reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Pet characteristics significantly associated with S. aureus colonization at study enrollment were older age (P = .04) and advanced number of years living in the home (P = .03), but sleeping in the same bed as a household member was not (P =. 96).

Molecular analysis revealed that the primary caretaker for 10 of the 15 colonized pets (67%) also was colonized with S. aureus, and 70% of these strains were concordant with the pet strain. In addition, seven of eight humans (88%) who shared a bed with a colonized pet also were colonized with S. aureus, and 43% of these strains were concordant with the pet strain.

Mr. Thompson also presented the longitudinal molecular epidemiology results in pets. In this analysis, 37 of the 89 pets were colonized with S. aureus at some point over the period of 12 months. Of these, 24 were colonized just once, while 13 were colonized at more than one of the samplings over time. Among these 13, two (15%) had concordant strains at all samplings, five (39%) had concordant and discordant strains, and six (46%) had discordant strains over the longitudinal study period.

Mr. Thompson and his associates intend to complete enrollment and analysis of 150 households in a 2-year longitudinal study. After this, he said, “we will be able to determine the directionality of human-pet S. aureus transmission as well as define the role of pets in S. aureus household transmission dynamics.”

The study was funded by the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: In homes of children with MRSA infection, pet dogs and cats were often colonized with S. aureus.

Major finding: Of the 63 dogs, 13 (21%) were colonized with S. aureus (9 with MRSA) and 2 of 26 cats (8%) were colonized with MRSA.

Data source: An analysis of 100 households of children with active or recent community-associated MRSA superficial skin and soft tissue infections who had been treated at St. Louis Children’s Hospital or other pediatric practices in the area between 2012 and 2015.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Software picked up HAI clusters faster than hospitals

SAN DIEGO – An automated outbreak detection system was popular among infection preventionists and detected pathogenic clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves, researchers said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“The vast majority of hospitals were very pleased to expand surveillance beyond multidrug-resistant organisms, and most thought this system would improve their ability to detect outbreaks and streamline their work,” said Dr. Meghan Baker of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

Patients in acute-care hospitals acquired almost 782,000 healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in 2011, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Traditionally, infection preventionists at these hospitals look for HAIs by identifying temporal or spatial clusters of “a limited number of prespecified pathogens,” Dr. Baker said. But some real clusters do not meet these empirical rules, leading to more cases and potentially severe consequences for patients. Automated HAI outbreak detection systems can help, but not if they constantly trigger false alarms or, conversely, are so specific that they miss outbreaks.

Using the Premier SafetySurveillor infection control tool and free statistical software, Dr. Baker and her associates analyzed 83 years of historical microbiology data from 44 hospitals. The system signaled for any cluster involving at least three cases, even if cases occurred by chance less than once a year, she said. The researchers compared the results with outbreak data submitted by a convenience sample of hospitals that used their usual surveillance methods.

The automated approach identified 230 clusters. Most were detected based on antimicrobial resistance, but others shared the same ward or specialty service and some produced more than one signal. Clusters most often involved Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella, but most organisms were not under routine surveillance. As a result, 89% of clusters detected by the automated tool were not detected by hospitals using their usual methods, she emphasized. “Some were not real breaks, as determined later by genetic typing,” she added. “Most real clusters were [methicillin-resistant S. aureus], Clostridium difficile, and some were resistant gram-negative rods.”

When surveyed, 76% of infection preventionists said the automated tool moderately or greatly improved their ability to detect outbreaks, Dr. Baker reported. They would have wanted notification about 81% of the clusters, and considered 47% to be moderately or highly concerning. Notably, 51% of clusters expanded after detection.

“If these had been detected in real time, it would have been possible to intervene and possibly curtail the outbreak,” and 237 (42%) of 559 infections might have been avoided if these interventions were successful, she said.

Dr. Baker and her associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

SAN DIEGO – An automated outbreak detection system was popular among infection preventionists and detected pathogenic clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves, researchers said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“The vast majority of hospitals were very pleased to expand surveillance beyond multidrug-resistant organisms, and most thought this system would improve their ability to detect outbreaks and streamline their work,” said Dr. Meghan Baker of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

Patients in acute-care hospitals acquired almost 782,000 healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in 2011, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Traditionally, infection preventionists at these hospitals look for HAIs by identifying temporal or spatial clusters of “a limited number of prespecified pathogens,” Dr. Baker said. But some real clusters do not meet these empirical rules, leading to more cases and potentially severe consequences for patients. Automated HAI outbreak detection systems can help, but not if they constantly trigger false alarms or, conversely, are so specific that they miss outbreaks.

Using the Premier SafetySurveillor infection control tool and free statistical software, Dr. Baker and her associates analyzed 83 years of historical microbiology data from 44 hospitals. The system signaled for any cluster involving at least three cases, even if cases occurred by chance less than once a year, she said. The researchers compared the results with outbreak data submitted by a convenience sample of hospitals that used their usual surveillance methods.

The automated approach identified 230 clusters. Most were detected based on antimicrobial resistance, but others shared the same ward or specialty service and some produced more than one signal. Clusters most often involved Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella, but most organisms were not under routine surveillance. As a result, 89% of clusters detected by the automated tool were not detected by hospitals using their usual methods, she emphasized. “Some were not real breaks, as determined later by genetic typing,” she added. “Most real clusters were [methicillin-resistant S. aureus], Clostridium difficile, and some were resistant gram-negative rods.”

When surveyed, 76% of infection preventionists said the automated tool moderately or greatly improved their ability to detect outbreaks, Dr. Baker reported. They would have wanted notification about 81% of the clusters, and considered 47% to be moderately or highly concerning. Notably, 51% of clusters expanded after detection.

“If these had been detected in real time, it would have been possible to intervene and possibly curtail the outbreak,” and 237 (42%) of 559 infections might have been avoided if these interventions were successful, she said.

Dr. Baker and her associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

SAN DIEGO – An automated outbreak detection system was popular among infection preventionists and detected pathogenic clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves, researchers said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“The vast majority of hospitals were very pleased to expand surveillance beyond multidrug-resistant organisms, and most thought this system would improve their ability to detect outbreaks and streamline their work,” said Dr. Meghan Baker of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

Patients in acute-care hospitals acquired almost 782,000 healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in 2011, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Traditionally, infection preventionists at these hospitals look for HAIs by identifying temporal or spatial clusters of “a limited number of prespecified pathogens,” Dr. Baker said. But some real clusters do not meet these empirical rules, leading to more cases and potentially severe consequences for patients. Automated HAI outbreak detection systems can help, but not if they constantly trigger false alarms or, conversely, are so specific that they miss outbreaks.

Using the Premier SafetySurveillor infection control tool and free statistical software, Dr. Baker and her associates analyzed 83 years of historical microbiology data from 44 hospitals. The system signaled for any cluster involving at least three cases, even if cases occurred by chance less than once a year, she said. The researchers compared the results with outbreak data submitted by a convenience sample of hospitals that used their usual surveillance methods.

The automated approach identified 230 clusters. Most were detected based on antimicrobial resistance, but others shared the same ward or specialty service and some produced more than one signal. Clusters most often involved Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella, but most organisms were not under routine surveillance. As a result, 89% of clusters detected by the automated tool were not detected by hospitals using their usual methods, she emphasized. “Some were not real breaks, as determined later by genetic typing,” she added. “Most real clusters were [methicillin-resistant S. aureus], Clostridium difficile, and some were resistant gram-negative rods.”

When surveyed, 76% of infection preventionists said the automated tool moderately or greatly improved their ability to detect outbreaks, Dr. Baker reported. They would have wanted notification about 81% of the clusters, and considered 47% to be moderately or highly concerning. Notably, 51% of clusters expanded after detection.

“If these had been detected in real time, it would have been possible to intervene and possibly curtail the outbreak,” and 237 (42%) of 559 infections might have been avoided if these interventions were successful, she said.

Dr. Baker and her associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: An automated outbreak detection system can augment traditional methods for detecting pathogenic clusters.

Major finding: The software tool identified clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves.

Data source: Comparison of an automated outbreak detection tool with usual hospital surveillance methods, and surveys of infection preventionists.

Disclosures: Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

Decline in antibiotic effectiveness could harm surgical, chemotherapy patients

An increase of surgical site infections (SSIs) stemming from pathogens resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis could result in thousands of infection-related deaths in surgical and chemotherapy patients, according to a new study published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 31 published meta-analyses of randomized or quasi–randomized controlled trials were included in the study by Dr. Ramanan Laxminarayan of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in Washington, and his associates. The researchers surveyed the 10 most common surgeries in which antibiotic prophylaxis provides the greatest benefit. The infection rate in surgical patients receiving prophylaxis was 4.2%, and was 11.1% in patients who did not receive prophylaxis. Relative risk reduction for infection was least in cancer chemotherapy at 35% and greatest in pacemaker implantation at 86%.

Between 38.7% and 50.9% of SSIs and 26.8% of infections after chemotherapy are caused by antibiotic-resistant pathogens. A decrease in prophylaxis effectiveness of 10% would cause 40,000 additional infections and 2,100 additional deaths, while a decrease in effectiveness of 70% would cause 280,000 additional infections and 15,000 additional deaths.

The authors say more data are needed to establish how antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations should be modified in the context of increasing rates of resistance.

In a related comment, Dr. Joshua Wolf from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, said, “To improve stewardship outcomes, we need more research that focuses on understanding impediments to appropriate antibiotic prescribing, strategies that target these impediments, resources to implement the strategies, and leadership that understands the urgency and complexity of the task. In view of the lack of progress so far, mandatory implementation of these steps could be necessary to achieve notable change.”

Find the full study in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00270-4).

An increase of surgical site infections (SSIs) stemming from pathogens resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis could result in thousands of infection-related deaths in surgical and chemotherapy patients, according to a new study published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 31 published meta-analyses of randomized or quasi–randomized controlled trials were included in the study by Dr. Ramanan Laxminarayan of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in Washington, and his associates. The researchers surveyed the 10 most common surgeries in which antibiotic prophylaxis provides the greatest benefit. The infection rate in surgical patients receiving prophylaxis was 4.2%, and was 11.1% in patients who did not receive prophylaxis. Relative risk reduction for infection was least in cancer chemotherapy at 35% and greatest in pacemaker implantation at 86%.

Between 38.7% and 50.9% of SSIs and 26.8% of infections after chemotherapy are caused by antibiotic-resistant pathogens. A decrease in prophylaxis effectiveness of 10% would cause 40,000 additional infections and 2,100 additional deaths, while a decrease in effectiveness of 70% would cause 280,000 additional infections and 15,000 additional deaths.

The authors say more data are needed to establish how antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations should be modified in the context of increasing rates of resistance.

In a related comment, Dr. Joshua Wolf from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, said, “To improve stewardship outcomes, we need more research that focuses on understanding impediments to appropriate antibiotic prescribing, strategies that target these impediments, resources to implement the strategies, and leadership that understands the urgency and complexity of the task. In view of the lack of progress so far, mandatory implementation of these steps could be necessary to achieve notable change.”

Find the full study in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00270-4).

An increase of surgical site infections (SSIs) stemming from pathogens resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis could result in thousands of infection-related deaths in surgical and chemotherapy patients, according to a new study published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

A total of 31 published meta-analyses of randomized or quasi–randomized controlled trials were included in the study by Dr. Ramanan Laxminarayan of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in Washington, and his associates. The researchers surveyed the 10 most common surgeries in which antibiotic prophylaxis provides the greatest benefit. The infection rate in surgical patients receiving prophylaxis was 4.2%, and was 11.1% in patients who did not receive prophylaxis. Relative risk reduction for infection was least in cancer chemotherapy at 35% and greatest in pacemaker implantation at 86%.

Between 38.7% and 50.9% of SSIs and 26.8% of infections after chemotherapy are caused by antibiotic-resistant pathogens. A decrease in prophylaxis effectiveness of 10% would cause 40,000 additional infections and 2,100 additional deaths, while a decrease in effectiveness of 70% would cause 280,000 additional infections and 15,000 additional deaths.

The authors say more data are needed to establish how antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations should be modified in the context of increasing rates of resistance.

In a related comment, Dr. Joshua Wolf from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, said, “To improve stewardship outcomes, we need more research that focuses on understanding impediments to appropriate antibiotic prescribing, strategies that target these impediments, resources to implement the strategies, and leadership that understands the urgency and complexity of the task. In view of the lack of progress so far, mandatory implementation of these steps could be necessary to achieve notable change.”

Find the full study in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00270-4).

Carbapenem resistance on the rise in children

The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in children is low but has increased significantly since 1999, particularly among isolates from intensive care units and from blood and lower respiratory tract cultures, new data suggest.

Analysis of 316,253 Enterobacteriaceae isolates reported to 300 U.S. laboratories participating in the Surveillance Network-USA database between 1999 and 2012 showed 0.08% of isolates were carbapenem resistant, with the most common resistant isolates being Enterobacter species isolated from urinary sources and from the inpatient non-ICU setting.

“Unlike for adults, where increases were greater than for children, we did not find that the increase in CRE in children appeared to be related to residence in long-term care facilities, because only 0.1% of CRE isolates came from this setting,” wrote Dr. Latania K. Logan, director of pediatric infectious diseases at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and her coauthors.

The study, published Oct. 14 in Emerging Infectious Diseases, showed a significant overall increase from 0% to 0.47% in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae over the 12-year study period; among ICU isolates, the prevalence increased from 0% to 4.5% over the same period.

Many of the carbapenem-resistant isolates also were resistant to other antimicrobial drugs, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin, and nearly half (48.3%) were resistant to more than three antimicrobial drug classes (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Oct 14. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150548).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Children’s Foundation, the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. No conflicts of interest were declared.

The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in children is low but has increased significantly since 1999, particularly among isolates from intensive care units and from blood and lower respiratory tract cultures, new data suggest.

Analysis of 316,253 Enterobacteriaceae isolates reported to 300 U.S. laboratories participating in the Surveillance Network-USA database between 1999 and 2012 showed 0.08% of isolates were carbapenem resistant, with the most common resistant isolates being Enterobacter species isolated from urinary sources and from the inpatient non-ICU setting.

“Unlike for adults, where increases were greater than for children, we did not find that the increase in CRE in children appeared to be related to residence in long-term care facilities, because only 0.1% of CRE isolates came from this setting,” wrote Dr. Latania K. Logan, director of pediatric infectious diseases at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and her coauthors.

The study, published Oct. 14 in Emerging Infectious Diseases, showed a significant overall increase from 0% to 0.47% in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae over the 12-year study period; among ICU isolates, the prevalence increased from 0% to 4.5% over the same period.

Many of the carbapenem-resistant isolates also were resistant to other antimicrobial drugs, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin, and nearly half (48.3%) were resistant to more than three antimicrobial drug classes (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Oct 14. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150548).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Children’s Foundation, the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. No conflicts of interest were declared.

The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in children is low but has increased significantly since 1999, particularly among isolates from intensive care units and from blood and lower respiratory tract cultures, new data suggest.

Analysis of 316,253 Enterobacteriaceae isolates reported to 300 U.S. laboratories participating in the Surveillance Network-USA database between 1999 and 2012 showed 0.08% of isolates were carbapenem resistant, with the most common resistant isolates being Enterobacter species isolated from urinary sources and from the inpatient non-ICU setting.

“Unlike for adults, where increases were greater than for children, we did not find that the increase in CRE in children appeared to be related to residence in long-term care facilities, because only 0.1% of CRE isolates came from this setting,” wrote Dr. Latania K. Logan, director of pediatric infectious diseases at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and her coauthors.

The study, published Oct. 14 in Emerging Infectious Diseases, showed a significant overall increase from 0% to 0.47% in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae over the 12-year study period; among ICU isolates, the prevalence increased from 0% to 4.5% over the same period.

Many of the carbapenem-resistant isolates also were resistant to other antimicrobial drugs, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin, and nearly half (48.3%) were resistant to more than three antimicrobial drug classes (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Oct 14. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150548).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Children’s Foundation, the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in children has increased significantly since 1999.

Major finding: The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates increased from 0% to 0.47% during 1999-2012.

Data source: Analysis of 316,253 Enterobacteriaceae isolates reported to 300 U.S. laboratories.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Children’s Foundation, the Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Health Grand Challenges Program at Princeton University. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Hospitals report inadequate duodenoscope reprocessing practices

SAN DIEGO – Less than a third of hospitals reprocessed duodenoscopes adequately to prevent potential transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and other pathogens, investigators reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Moreover, only a third of facilities had conducted active surveillance for multidrug-resistant infections related to use of their duodenoscopes in the past year, reported Susan Beekmann of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “These findings suggest that endemic bacterial transmission associated with duodenoscopy may occur and may go unrecognized,” said Ms. Beekmann, program coordinator for EIN at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City.

Duodenoscopes, which are used in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), became a hot topic earlier this year after causing outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration has acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the CDC and the FDA have recommended specific reprocessing and surveillance steps to reduce the chances that the scopes transmit serious infections.

To understand how hospitals were actually reprocessing and culturing the scopes at the time CDC released its guidance, Ms. Beekmann and her colleagues electronically surveyed 740 hospital epidemiologists through IDSA-EIN. They received responses from 378 physicians (52%), of which half said their facilities used duodenoscopes, Ms. Beekmann reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Only 55 (29%) of these respondents said their facilities reprocessed duodenoscopes to an extent that the IDSA researchers defined as adequate – that is, manual reprocessing with high-level disinfection, either alone or in combination with other options, Ms. Beekmann said. Furthermore, only a third of facilities had cultured their duodenoscopes or done any other surveillance for bacterial transmission after duodenoscopy in the past year, even though most said they reviewed their reprocessing policies and procedures more often than once a year.

Respondents also described widely varying methodologies for sampling and culturing, Ms. Beekmann said. “Although we did not ask about them, ten respondents mentioned ATP bioluminescence assays,” she added. Based on the findings, better reprocessing technologies and consistent, real-time strategies to monitor the effectiveness of scope reprocessing are “urgent patient safety needs,” she and her colleagues concluded.

Ms. Beekmann and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Less than a third of hospitals reprocessed duodenoscopes adequately to prevent potential transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and other pathogens, investigators reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Moreover, only a third of facilities had conducted active surveillance for multidrug-resistant infections related to use of their duodenoscopes in the past year, reported Susan Beekmann of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “These findings suggest that endemic bacterial transmission associated with duodenoscopy may occur and may go unrecognized,” said Ms. Beekmann, program coordinator for EIN at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City.

Duodenoscopes, which are used in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), became a hot topic earlier this year after causing outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration has acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the CDC and the FDA have recommended specific reprocessing and surveillance steps to reduce the chances that the scopes transmit serious infections.

To understand how hospitals were actually reprocessing and culturing the scopes at the time CDC released its guidance, Ms. Beekmann and her colleagues electronically surveyed 740 hospital epidemiologists through IDSA-EIN. They received responses from 378 physicians (52%), of which half said their facilities used duodenoscopes, Ms. Beekmann reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Only 55 (29%) of these respondents said their facilities reprocessed duodenoscopes to an extent that the IDSA researchers defined as adequate – that is, manual reprocessing with high-level disinfection, either alone or in combination with other options, Ms. Beekmann said. Furthermore, only a third of facilities had cultured their duodenoscopes or done any other surveillance for bacterial transmission after duodenoscopy in the past year, even though most said they reviewed their reprocessing policies and procedures more often than once a year.

Respondents also described widely varying methodologies for sampling and culturing, Ms. Beekmann said. “Although we did not ask about them, ten respondents mentioned ATP bioluminescence assays,” she added. Based on the findings, better reprocessing technologies and consistent, real-time strategies to monitor the effectiveness of scope reprocessing are “urgent patient safety needs,” she and her colleagues concluded.

Ms. Beekmann and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Less than a third of hospitals reprocessed duodenoscopes adequately to prevent potential transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and other pathogens, investigators reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Moreover, only a third of facilities had conducted active surveillance for multidrug-resistant infections related to use of their duodenoscopes in the past year, reported Susan Beekmann of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “These findings suggest that endemic bacterial transmission associated with duodenoscopy may occur and may go unrecognized,” said Ms. Beekmann, program coordinator for EIN at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City.

Duodenoscopes, which are used in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), became a hot topic earlier this year after causing outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration has acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the CDC and the FDA have recommended specific reprocessing and surveillance steps to reduce the chances that the scopes transmit serious infections.

To understand how hospitals were actually reprocessing and culturing the scopes at the time CDC released its guidance, Ms. Beekmann and her colleagues electronically surveyed 740 hospital epidemiologists through IDSA-EIN. They received responses from 378 physicians (52%), of which half said their facilities used duodenoscopes, Ms. Beekmann reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Only 55 (29%) of these respondents said their facilities reprocessed duodenoscopes to an extent that the IDSA researchers defined as adequate – that is, manual reprocessing with high-level disinfection, either alone or in combination with other options, Ms. Beekmann said. Furthermore, only a third of facilities had cultured their duodenoscopes or done any other surveillance for bacterial transmission after duodenoscopy in the past year, even though most said they reviewed their reprocessing policies and procedures more often than once a year.

Respondents also described widely varying methodologies for sampling and culturing, Ms. Beekmann said. “Although we did not ask about them, ten respondents mentioned ATP bioluminescence assays,” she added. Based on the findings, better reprocessing technologies and consistent, real-time strategies to monitor the effectiveness of scope reprocessing are “urgent patient safety needs,” she and her colleagues concluded.

Ms. Beekmann and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Most hospitals did not reprocess duodenoscopes in a way that the Infectious Diseases Society of America considers adequate.

Major finding: Only 29% of facilities followed the minimum adequate practices.

Data source: A cross-sectional electronic survey of 378 physician members of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Disclosures: Susan Beekmann reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Old drug is new treatment for chronic prostatitis

SAN DIEGO – Oral fosfomycin, a drug used for more than 4 decades to treat urinary tract infections in women, has gained a new life as a promising treatment for chronic prostatitis.

In the largest patient series reported to date, a 6-week course of fosfomycin resulted in an 85% clinical cure rate in 20 men with chronic prostatitis due to multidrug-resistant pathogens, Dr. Ilias Karaiskos reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

This is a most welcome development because chronic prostatitis is a common condition and Escherichia coli – the number-one pathogen – is becoming increasingly resistant to fluoroquinolones, long considered the first-line therapy. The quinolone resistance issue is of particular concern because most other antibiotics lack the pharmacokinetics required to penetrate the prostate gland, explained Dr. Karaiskos of Hygeia General Hospital in Athens.

A recent study by other investigators showing that fosfomycin penetrates the prostate and achieves potentially therapeutic levels (Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Feb;58[4]:e101-5) inspired Dr. Karaiskos and coworkers to conduct their open 20-patient trial. Participants averaged 2.25 prior episodes of prostatitis.

Urine cultures showed that the most common pathogen was indeed E. coli, and that 15 of the 20 strains were resistant to fluoroquinolones. Most strains were also resistant to minocycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, all strains were sensitive to fosfomycin (Monurol).

Dosing of fosfomycin in the study was 3 g once daily for the first week, then 3 g every 48 hours for the next 5 weeks.

Seventeen of 20 patients experienced clinical cure, defined as resolution of all symptoms plus absence of any evidence of inflammation upon follow-up imaging of the prostate by transrectal ultrasound or MRI upon treatment completion after 6 weeks of fosfomycin. Two patients failed to respond, and one discontinued treatment due to diarrhea.

Diarrhea was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event, affecting 5 of 20 patients. In most instances, diarrhea subsided when the dosing intervals were extended.

Further studies are needed to clarify the best fosfomycin dosing regimen for chronic prostatitis, Dr. Karaiskos said. For uncomplicated urinary tract infections the drug is typically given in a single megadose.

Dr. Karaiskos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Oral fosfomycin, a drug used for more than 4 decades to treat urinary tract infections in women, has gained a new life as a promising treatment for chronic prostatitis.

In the largest patient series reported to date, a 6-week course of fosfomycin resulted in an 85% clinical cure rate in 20 men with chronic prostatitis due to multidrug-resistant pathogens, Dr. Ilias Karaiskos reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

This is a most welcome development because chronic prostatitis is a common condition and Escherichia coli – the number-one pathogen – is becoming increasingly resistant to fluoroquinolones, long considered the first-line therapy. The quinolone resistance issue is of particular concern because most other antibiotics lack the pharmacokinetics required to penetrate the prostate gland, explained Dr. Karaiskos of Hygeia General Hospital in Athens.

A recent study by other investigators showing that fosfomycin penetrates the prostate and achieves potentially therapeutic levels (Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Feb;58[4]:e101-5) inspired Dr. Karaiskos and coworkers to conduct their open 20-patient trial. Participants averaged 2.25 prior episodes of prostatitis.

Urine cultures showed that the most common pathogen was indeed E. coli, and that 15 of the 20 strains were resistant to fluoroquinolones. Most strains were also resistant to minocycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, all strains were sensitive to fosfomycin (Monurol).

Dosing of fosfomycin in the study was 3 g once daily for the first week, then 3 g every 48 hours for the next 5 weeks.

Seventeen of 20 patients experienced clinical cure, defined as resolution of all symptoms plus absence of any evidence of inflammation upon follow-up imaging of the prostate by transrectal ultrasound or MRI upon treatment completion after 6 weeks of fosfomycin. Two patients failed to respond, and one discontinued treatment due to diarrhea.

Diarrhea was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event, affecting 5 of 20 patients. In most instances, diarrhea subsided when the dosing intervals were extended.

Further studies are needed to clarify the best fosfomycin dosing regimen for chronic prostatitis, Dr. Karaiskos said. For uncomplicated urinary tract infections the drug is typically given in a single megadose.

Dr. Karaiskos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – Oral fosfomycin, a drug used for more than 4 decades to treat urinary tract infections in women, has gained a new life as a promising treatment for chronic prostatitis.

In the largest patient series reported to date, a 6-week course of fosfomycin resulted in an 85% clinical cure rate in 20 men with chronic prostatitis due to multidrug-resistant pathogens, Dr. Ilias Karaiskos reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

This is a most welcome development because chronic prostatitis is a common condition and Escherichia coli – the number-one pathogen – is becoming increasingly resistant to fluoroquinolones, long considered the first-line therapy. The quinolone resistance issue is of particular concern because most other antibiotics lack the pharmacokinetics required to penetrate the prostate gland, explained Dr. Karaiskos of Hygeia General Hospital in Athens.

A recent study by other investigators showing that fosfomycin penetrates the prostate and achieves potentially therapeutic levels (Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Feb;58[4]:e101-5) inspired Dr. Karaiskos and coworkers to conduct their open 20-patient trial. Participants averaged 2.25 prior episodes of prostatitis.

Urine cultures showed that the most common pathogen was indeed E. coli, and that 15 of the 20 strains were resistant to fluoroquinolones. Most strains were also resistant to minocycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, all strains were sensitive to fosfomycin (Monurol).

Dosing of fosfomycin in the study was 3 g once daily for the first week, then 3 g every 48 hours for the next 5 weeks.

Seventeen of 20 patients experienced clinical cure, defined as resolution of all symptoms plus absence of any evidence of inflammation upon follow-up imaging of the prostate by transrectal ultrasound or MRI upon treatment completion after 6 weeks of fosfomycin. Two patients failed to respond, and one discontinued treatment due to diarrhea.

Diarrhea was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event, affecting 5 of 20 patients. In most instances, diarrhea subsided when the dosing intervals were extended.

Further studies are needed to clarify the best fosfomycin dosing regimen for chronic prostatitis, Dr. Karaiskos said. For uncomplicated urinary tract infections the drug is typically given in a single megadose.

Dr. Karaiskos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

AT ICAAC 2015

Key clinical point: Oral fosfomycin is an effective alternative to fluoroquinolones in chronic prostatitis patients.

Major finding: Six weeks of oral fosfomycin resulted in an 85% clinical cure rate in 20 men with multidrug-resistant chronic prostatitis.

Data source: This was an open-label, uncontrolled study.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted free of commercial support.

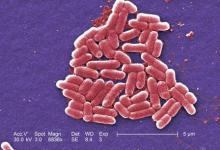

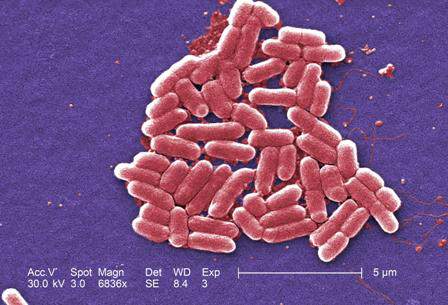

Some 4% of healthy U.S. children carry antibiotic-resistant E. coli isolates

SAN DIEGO – Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli infection carriage was present in 4.2% of healthy children who underwent stool testing, especially in young children and in those with a household member who traveled internationally within the last year.

Those are key findings from a multicenter study which set out to examine the epidemiology of antibiotic-resistant E. coli colonization in healthy children.

“Overall, the results suggest that there is circulation and spread of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli infection at the community and global level,” Dr. Shamim M. Islam said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Dr. Islam of the department of pediatrics at the State University of New York at Buffalo characterized the management of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase infections as “particularly complicated in children given limited antibiotic options. ESBL [Extended spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing Enterobacteriaceae infections are steadily rising, including in the community setting.”

As part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network acute gastroenteritis project, the researchers enrolled 520 healthy children ranging in age from 14 days to 11 years during well-child visits in Oakland, Calif.; Kansas City, Mo.; and Nashville, Tenn., between December of 2013 and March of 2015. Dr. Islam and his associates administered a four-question survey to parents of the children, including questions about recent antibiotic use in the child and travel and hospitalization history of all members of their household. They collected stool samples from the children and used chromogenic commercial media technology to screen for ESBL-producing bacteria, and also performed confirmatory testing.

Dr. Islam reported that third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli was present in 4.2% of overall stools, with a range from 3.4% to 5.1% among the three study sites. It was found to be more prevalent in children younger than age 5, compared with those aged 5 and older (4.9% vs. 1.7%, respectively; P = .21).

At the Oakland site, 50% of children carrying third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli isolates had a household member who traveled internationally in the past year, compared with 11% of noncarriers (P = .05), while international travel at the other two sites was low. Combined results from those two sites indicated that 18.2% of children carrying third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli isolates had a household member who traveled internationally in the past year, compared with 6.1% of noncarriers (P = .07).

Going forward, the researchers are planning to conduct further genetic and molecular characterization of the isolates they found with mutliplex pCR and whole-genome sequencing. “We’re going to continue surveillance of bacterial carriage at our current three sites for another year to try and expand our risk factor analysis to include more dietary risk factors and more antibiotic exposure,” Dr. Islam said.

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli infection carriage was present in 4.2% of healthy children who underwent stool testing, especially in young children and in those with a household member who traveled internationally within the last year.

Those are key findings from a multicenter study which set out to examine the epidemiology of antibiotic-resistant E. coli colonization in healthy children.

“Overall, the results suggest that there is circulation and spread of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli infection at the community and global level,” Dr. Shamim M. Islam said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Dr. Islam of the department of pediatrics at the State University of New York at Buffalo characterized the management of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase infections as “particularly complicated in children given limited antibiotic options. ESBL [Extended spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing Enterobacteriaceae infections are steadily rising, including in the community setting.”

As part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network acute gastroenteritis project, the researchers enrolled 520 healthy children ranging in age from 14 days to 11 years during well-child visits in Oakland, Calif.; Kansas City, Mo.; and Nashville, Tenn., between December of 2013 and March of 2015. Dr. Islam and his associates administered a four-question survey to parents of the children, including questions about recent antibiotic use in the child and travel and hospitalization history of all members of their household. They collected stool samples from the children and used chromogenic commercial media technology to screen for ESBL-producing bacteria, and also performed confirmatory testing.

Dr. Islam reported that third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli was present in 4.2% of overall stools, with a range from 3.4% to 5.1% among the three study sites. It was found to be more prevalent in children younger than age 5, compared with those aged 5 and older (4.9% vs. 1.7%, respectively; P = .21).

At the Oakland site, 50% of children carrying third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli isolates had a household member who traveled internationally in the past year, compared with 11% of noncarriers (P = .05), while international travel at the other two sites was low. Combined results from those two sites indicated that 18.2% of children carrying third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli isolates had a household member who traveled internationally in the past year, compared with 6.1% of noncarriers (P = .07).

Going forward, the researchers are planning to conduct further genetic and molecular characterization of the isolates they found with mutliplex pCR and whole-genome sequencing. “We’re going to continue surveillance of bacterial carriage at our current three sites for another year to try and expand our risk factor analysis to include more dietary risk factors and more antibiotic exposure,” Dr. Islam said.

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli infection carriage was present in 4.2% of healthy children who underwent stool testing, especially in young children and in those with a household member who traveled internationally within the last year.

Those are key findings from a multicenter study which set out to examine the epidemiology of antibiotic-resistant E. coli colonization in healthy children.

“Overall, the results suggest that there is circulation and spread of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli infection at the community and global level,” Dr. Shamim M. Islam said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Dr. Islam of the department of pediatrics at the State University of New York at Buffalo characterized the management of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase infections as “particularly complicated in children given limited antibiotic options. ESBL [Extended spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing Enterobacteriaceae infections are steadily rising, including in the community setting.”

As part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s New Vaccine Surveillance Network acute gastroenteritis project, the researchers enrolled 520 healthy children ranging in age from 14 days to 11 years during well-child visits in Oakland, Calif.; Kansas City, Mo.; and Nashville, Tenn., between December of 2013 and March of 2015. Dr. Islam and his associates administered a four-question survey to parents of the children, including questions about recent antibiotic use in the child and travel and hospitalization history of all members of their household. They collected stool samples from the children and used chromogenic commercial media technology to screen for ESBL-producing bacteria, and also performed confirmatory testing.

Dr. Islam reported that third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli was present in 4.2% of overall stools, with a range from 3.4% to 5.1% among the three study sites. It was found to be more prevalent in children younger than age 5, compared with those aged 5 and older (4.9% vs. 1.7%, respectively; P = .21).

At the Oakland site, 50% of children carrying third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli isolates had a household member who traveled internationally in the past year, compared with 11% of noncarriers (P = .05), while international travel at the other two sites was low. Combined results from those two sites indicated that 18.2% of children carrying third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli isolates had a household member who traveled internationally in the past year, compared with 6.1% of noncarriers (P = .07).

Going forward, the researchers are planning to conduct further genetic and molecular characterization of the isolates they found with mutliplex pCR and whole-genome sequencing. “We’re going to continue surveillance of bacterial carriage at our current three sites for another year to try and expand our risk factor analysis to include more dietary risk factors and more antibiotic exposure,” Dr. Islam said.

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: About 4% of healthy children in the United States harbor antibitotic-resistant E. coli.

Major finding: Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli was present in 4.2% of overall stools, with a range from 3.4% to 5.1%.

Data source: An analysis of stool samples obtained from 520 healthy children during well-child visits in three different centers in the United States.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Take steps now to keep gram-negative resistance at bay

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Results mixed in hospital efforts to tackle antimicrobial resistance

SAN DIEGO – Canadian hospitals are making progress in reducing the rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, but the rates of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian hospitals increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Those are among the key findings from a large national analysis known as CANWARD that were presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. “What it’s telling us is that some of the things that we’re doing on the antimicrobial resistance side are working,” lead study author George G. Zhanel, Pharm.D., professor of microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, said in an interview. “But it also tells us that some of these pathogens like [vancomycin-resistant enterococci] and [extended-spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing E. coli continue to go up. So there is some good news and some bad news, but it tells us that it’s not all just doom and gloom. Some progress has been made, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Conducted annually, CANWARD is a national health surveillance study that assesses pathogens causing infections in Canadian hospitals and their patterns of antimicrobial resistance. For the current analysis, Dr. Zhanel and his associates collected 36,607 isolates from patients in tertiary care hospitals in Canada from January 2007 to December 2014. They used Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing on more than 45 marketed and investigational agents.

Slightly more than half of the patients (55%) were male, and 87% were over age 18. The most common pathogens were E. coli (19.7%), methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA; 16.4%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.7%), S. pneumoniae (6.5%), K. pneumoniae (6.1%), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA; 4.7%), Enterococcus species (4.0%), and Hemophilus influenzae (4.0%). Susceptibility rates for E. coli were 99.9% for meropenem and tigecycline, 99.7% for ertapenem, 97.7% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 92.5% for ceftriaxone, 90.4% for gentamicin, 77.2% for ciprofloxacin, and 73.0% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Susceptibility rates for P. aeruginosa were 94.2% for colistin, 84.3% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 83.3% for ceftazidime, 81.2% for meropenem, 77.6% for gentamicin, and 74.1% for ciprofloxacin. Susceptibility rates for MRSA were 100% for linezolid and telavancin, 99.9% for daptomycin, 99.4% for tigecycline, 99.1% for vancomycin, and 93.3% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. The rates of resistant organisms between 2007 and 2014 increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing E. coli (from 3.4% to 11.6%) and K. pneumoniae (from 1.5% to 6.5%), as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (from 1.8% to 7.0%), while rates of MRSA significantly declined (from 26.1% to 20.2%).

“The biggest surprise to me is that the hospital-acquired genotype of MRSA is going down,” Dr. Zhanel commented. “The community-acquired genotype is still going up, but the hospital-acquired [genotype] has plummeted in hospitals.”

He noted that CANWARD data suggest that antimicrobial resistance “is not confined to one part of the hospital. We have resistance happening in medical wards, ICUs, and hospital emergency rooms. We consistently find that resistance is highest in the ICU and by far the lowest in the ER. With clinics we find that it’s a variable scenario.”

The study was supported in part by Abbott, Achaogen, Affinium, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Cerexa/Forest, Cubist, Galderma Laboratories, Merck, Paladin Labs, Pfizer/Wyeth, Sunovion, and the Medicines Co. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Canadian hospitals are making progress in reducing the rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, but the rates of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian hospitals increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Those are among the key findings from a large national analysis known as CANWARD that were presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. “What it’s telling us is that some of the things that we’re doing on the antimicrobial resistance side are working,” lead study author George G. Zhanel, Pharm.D., professor of microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, said in an interview. “But it also tells us that some of these pathogens like [vancomycin-resistant enterococci] and [extended-spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing E. coli continue to go up. So there is some good news and some bad news, but it tells us that it’s not all just doom and gloom. Some progress has been made, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Conducted annually, CANWARD is a national health surveillance study that assesses pathogens causing infections in Canadian hospitals and their patterns of antimicrobial resistance. For the current analysis, Dr. Zhanel and his associates collected 36,607 isolates from patients in tertiary care hospitals in Canada from January 2007 to December 2014. They used Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing on more than 45 marketed and investigational agents.

Slightly more than half of the patients (55%) were male, and 87% were over age 18. The most common pathogens were E. coli (19.7%), methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA; 16.4%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.7%), S. pneumoniae (6.5%), K. pneumoniae (6.1%), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA; 4.7%), Enterococcus species (4.0%), and Hemophilus influenzae (4.0%). Susceptibility rates for E. coli were 99.9% for meropenem and tigecycline, 99.7% for ertapenem, 97.7% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 92.5% for ceftriaxone, 90.4% for gentamicin, 77.2% for ciprofloxacin, and 73.0% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Susceptibility rates for P. aeruginosa were 94.2% for colistin, 84.3% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 83.3% for ceftazidime, 81.2% for meropenem, 77.6% for gentamicin, and 74.1% for ciprofloxacin. Susceptibility rates for MRSA were 100% for linezolid and telavancin, 99.9% for daptomycin, 99.4% for tigecycline, 99.1% for vancomycin, and 93.3% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. The rates of resistant organisms between 2007 and 2014 increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing E. coli (from 3.4% to 11.6%) and K. pneumoniae (from 1.5% to 6.5%), as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (from 1.8% to 7.0%), while rates of MRSA significantly declined (from 26.1% to 20.2%).

“The biggest surprise to me is that the hospital-acquired genotype of MRSA is going down,” Dr. Zhanel commented. “The community-acquired genotype is still going up, but the hospital-acquired [genotype] has plummeted in hospitals.”

He noted that CANWARD data suggest that antimicrobial resistance “is not confined to one part of the hospital. We have resistance happening in medical wards, ICUs, and hospital emergency rooms. We consistently find that resistance is highest in the ICU and by far the lowest in the ER. With clinics we find that it’s a variable scenario.”

The study was supported in part by Abbott, Achaogen, Affinium, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Cerexa/Forest, Cubist, Galderma Laboratories, Merck, Paladin Labs, Pfizer/Wyeth, Sunovion, and the Medicines Co. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Canadian hospitals are making progress in reducing the rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, but the rates of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian hospitals increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci.