User login

ADHD med may reduce apathy in Alzheimer’s disease

Methylphenidate is safe and effective for treating apathy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), new research suggests.

Results from a phase 3 randomized trial showed that, after 6 months of treatment, mean score on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) apathy subscale decreased by 4.5 points for patients who received methylphenidate vs. a decrease of 3.1 points for those who received placebo.

In addition, the safety profile showed no significant between-group differences.

“Methylphenidate offers a treatment approach providing a modest but potentially clinically significant benefit for patients and caregivers,” said the investigators, led by Jacobo E. Mintzer, MD, MBA, professor of health studies at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

The findings were published online Sept. 27 in JAMA Neurology.

Common problem

Apathy, which is common among patients with AD, is associated with increased risk for mortality, financial burden, and caregiver burden. No treatment has proved effective for apathy in this population.

Two trials of methylphenidate, a catecholaminergic agent, have provided preliminary evidence of efficacy. Findings from the Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate trial (ADMET) suggested the drug was associated with improved cognition and few adverse events. However, both trials had small patient populations and short durations.

The current investigators conducted ADMET 2, a 6-month, phase 3 trial, to investigate methylphenidate further. They recruited 200 patients (mean age, 76 years; 66% men; 90% White) at nine clinical centers that specialized in dementia care in the United States and one in Canada.

Eligible patients had a diagnosis of possible or probable AD and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 10 and 28. They also had clinically significant apathy for at least 4 weeks and an available caregiver who spent more than 10 hours a week with the patient.

The researchers randomly assigned patients to receive methylphenidate (n = 99) or placebo (n = 101). For 3 days, participants in the active group received 10 mg/day of methylphenidate. After that point, they received 20 mg/day of methylphenidate for the rest of the study.

Patients in both treatment groups were given the same number of identical-appearing capsules each day.

In-person follow-up visits took place monthly for 6 months. Participants also were contacted by telephone at days 15, 45, and 75 after treatment assignment.

Participants underwent cognitive testing at baseline and at 2, 4, and 6 months. The battery of tests included the MMSE, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised Digit Span.

The trial’s two primary outcomes were mean change in NPI apathy score from baseline to 6 months and the odds of an improved rating on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGIC) between baseline and 6 months.

Significant change on either outcome was to be considered a signal of effective treatment.

Treatment-specific benefit

Ten patients in the methylphenidate group and seven in the placebo group withdrew during the study.

Mean baseline score on the NPI apathy subscale was 8.0 vs. 7.6, respectively.

In an adjusted, longitudinal model, mean between-group difference in change in NPI apathy score at 6 months was –1.25 (P = .002). The mean NPI apathy score decreased by 4.5 points in the methylphenidate group vs. 3.1 points in the placebo group.

The largest change in apathy score occurred during the first 2 months of treatment. At 6 months, 27% of the methylphenidate group vs. 14% of the placebo group had an NPI apathy score of 0.

In addition, 43.8% of the methylphenidate group had improvement on the ADCS-CGIC compared with 35.2% of the placebo group. The odds ratio (OR) for improvement on ADCS-CGIC for methylphenidate vs. placebo was 1.90 (P = .07).

There was also a strong association between score improvement on the NPI apathy subscale and improvement on the ADCS-CGIC subscale (OR, 2.95; P = .002).

“It is important to note that there were no group differences in any of the cognitive measures, suggesting that the effect of the treatment is specific to the treatment of apathy and not a secondary effect of improvement in cognition,” the researchers wrote.

In all, 17 serious adverse events occurred in the methylphenidate group and 10 occurred in the placebo group. However, all events were found to be hospitalizations for events not related to treatment.

‘Enduring effect’

Commenting on the findings, Jeffrey L. Cummings, MD, ScD, professor of brain sciences at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, noted that the reduction in NPI apathy subscale score of more than 50% was clinically meaningful.

A more robust outcome on the ADCS-CGIC would have been desirable, he added, although that instrument is not designed specifically for apathy.

Methylphenidate’s effect on apathy observed at 2 months and remaining stable throughout the study makes it appear to be “an enduring effect, and not something that the patient accommodates to,” said Dr. Cummings, who was not involved with the research. Such a change may manifest itself in a patient’s greater willingness to help voluntarily with housework or to suggest going for a walk, he noted.

“These are not dramatic changes in cognition, of course, but they are changes in initiative and that is very important,” Dr. Cummings said. Decreased apathy also may improve quality of life for the patient’s caregiver, he added.

Overall, the findings raise the question of whether the Food and Drug Administration should recognize apathy as an indication for which drugs can be approved, said Dr. Cummings.

“For me, that would be the next major step in this line of investigation,” he concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mintzer has served as an adviser to Praxis Bioresearch and Cerevel Therapeutics on matters unrelated to this study. Dr. Cummings is the author of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory but does not receive payments for it from academic trials such as ADMET 2.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Methylphenidate is safe and effective for treating apathy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), new research suggests.

Results from a phase 3 randomized trial showed that, after 6 months of treatment, mean score on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) apathy subscale decreased by 4.5 points for patients who received methylphenidate vs. a decrease of 3.1 points for those who received placebo.

In addition, the safety profile showed no significant between-group differences.

“Methylphenidate offers a treatment approach providing a modest but potentially clinically significant benefit for patients and caregivers,” said the investigators, led by Jacobo E. Mintzer, MD, MBA, professor of health studies at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

The findings were published online Sept. 27 in JAMA Neurology.

Common problem

Apathy, which is common among patients with AD, is associated with increased risk for mortality, financial burden, and caregiver burden. No treatment has proved effective for apathy in this population.

Two trials of methylphenidate, a catecholaminergic agent, have provided preliminary evidence of efficacy. Findings from the Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate trial (ADMET) suggested the drug was associated with improved cognition and few adverse events. However, both trials had small patient populations and short durations.

The current investigators conducted ADMET 2, a 6-month, phase 3 trial, to investigate methylphenidate further. They recruited 200 patients (mean age, 76 years; 66% men; 90% White) at nine clinical centers that specialized in dementia care in the United States and one in Canada.

Eligible patients had a diagnosis of possible or probable AD and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 10 and 28. They also had clinically significant apathy for at least 4 weeks and an available caregiver who spent more than 10 hours a week with the patient.

The researchers randomly assigned patients to receive methylphenidate (n = 99) or placebo (n = 101). For 3 days, participants in the active group received 10 mg/day of methylphenidate. After that point, they received 20 mg/day of methylphenidate for the rest of the study.

Patients in both treatment groups were given the same number of identical-appearing capsules each day.

In-person follow-up visits took place monthly for 6 months. Participants also were contacted by telephone at days 15, 45, and 75 after treatment assignment.

Participants underwent cognitive testing at baseline and at 2, 4, and 6 months. The battery of tests included the MMSE, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised Digit Span.

The trial’s two primary outcomes were mean change in NPI apathy score from baseline to 6 months and the odds of an improved rating on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGIC) between baseline and 6 months.

Significant change on either outcome was to be considered a signal of effective treatment.

Treatment-specific benefit

Ten patients in the methylphenidate group and seven in the placebo group withdrew during the study.

Mean baseline score on the NPI apathy subscale was 8.0 vs. 7.6, respectively.

In an adjusted, longitudinal model, mean between-group difference in change in NPI apathy score at 6 months was –1.25 (P = .002). The mean NPI apathy score decreased by 4.5 points in the methylphenidate group vs. 3.1 points in the placebo group.

The largest change in apathy score occurred during the first 2 months of treatment. At 6 months, 27% of the methylphenidate group vs. 14% of the placebo group had an NPI apathy score of 0.

In addition, 43.8% of the methylphenidate group had improvement on the ADCS-CGIC compared with 35.2% of the placebo group. The odds ratio (OR) for improvement on ADCS-CGIC for methylphenidate vs. placebo was 1.90 (P = .07).

There was also a strong association between score improvement on the NPI apathy subscale and improvement on the ADCS-CGIC subscale (OR, 2.95; P = .002).

“It is important to note that there were no group differences in any of the cognitive measures, suggesting that the effect of the treatment is specific to the treatment of apathy and not a secondary effect of improvement in cognition,” the researchers wrote.

In all, 17 serious adverse events occurred in the methylphenidate group and 10 occurred in the placebo group. However, all events were found to be hospitalizations for events not related to treatment.

‘Enduring effect’

Commenting on the findings, Jeffrey L. Cummings, MD, ScD, professor of brain sciences at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, noted that the reduction in NPI apathy subscale score of more than 50% was clinically meaningful.

A more robust outcome on the ADCS-CGIC would have been desirable, he added, although that instrument is not designed specifically for apathy.

Methylphenidate’s effect on apathy observed at 2 months and remaining stable throughout the study makes it appear to be “an enduring effect, and not something that the patient accommodates to,” said Dr. Cummings, who was not involved with the research. Such a change may manifest itself in a patient’s greater willingness to help voluntarily with housework or to suggest going for a walk, he noted.

“These are not dramatic changes in cognition, of course, but they are changes in initiative and that is very important,” Dr. Cummings said. Decreased apathy also may improve quality of life for the patient’s caregiver, he added.

Overall, the findings raise the question of whether the Food and Drug Administration should recognize apathy as an indication for which drugs can be approved, said Dr. Cummings.

“For me, that would be the next major step in this line of investigation,” he concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mintzer has served as an adviser to Praxis Bioresearch and Cerevel Therapeutics on matters unrelated to this study. Dr. Cummings is the author of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory but does not receive payments for it from academic trials such as ADMET 2.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Methylphenidate is safe and effective for treating apathy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), new research suggests.

Results from a phase 3 randomized trial showed that, after 6 months of treatment, mean score on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) apathy subscale decreased by 4.5 points for patients who received methylphenidate vs. a decrease of 3.1 points for those who received placebo.

In addition, the safety profile showed no significant between-group differences.

“Methylphenidate offers a treatment approach providing a modest but potentially clinically significant benefit for patients and caregivers,” said the investigators, led by Jacobo E. Mintzer, MD, MBA, professor of health studies at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

The findings were published online Sept. 27 in JAMA Neurology.

Common problem

Apathy, which is common among patients with AD, is associated with increased risk for mortality, financial burden, and caregiver burden. No treatment has proved effective for apathy in this population.

Two trials of methylphenidate, a catecholaminergic agent, have provided preliminary evidence of efficacy. Findings from the Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate trial (ADMET) suggested the drug was associated with improved cognition and few adverse events. However, both trials had small patient populations and short durations.

The current investigators conducted ADMET 2, a 6-month, phase 3 trial, to investigate methylphenidate further. They recruited 200 patients (mean age, 76 years; 66% men; 90% White) at nine clinical centers that specialized in dementia care in the United States and one in Canada.

Eligible patients had a diagnosis of possible or probable AD and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 10 and 28. They also had clinically significant apathy for at least 4 weeks and an available caregiver who spent more than 10 hours a week with the patient.

The researchers randomly assigned patients to receive methylphenidate (n = 99) or placebo (n = 101). For 3 days, participants in the active group received 10 mg/day of methylphenidate. After that point, they received 20 mg/day of methylphenidate for the rest of the study.

Patients in both treatment groups were given the same number of identical-appearing capsules each day.

In-person follow-up visits took place monthly for 6 months. Participants also were contacted by telephone at days 15, 45, and 75 after treatment assignment.

Participants underwent cognitive testing at baseline and at 2, 4, and 6 months. The battery of tests included the MMSE, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised Digit Span.

The trial’s two primary outcomes were mean change in NPI apathy score from baseline to 6 months and the odds of an improved rating on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGIC) between baseline and 6 months.

Significant change on either outcome was to be considered a signal of effective treatment.

Treatment-specific benefit

Ten patients in the methylphenidate group and seven in the placebo group withdrew during the study.

Mean baseline score on the NPI apathy subscale was 8.0 vs. 7.6, respectively.

In an adjusted, longitudinal model, mean between-group difference in change in NPI apathy score at 6 months was –1.25 (P = .002). The mean NPI apathy score decreased by 4.5 points in the methylphenidate group vs. 3.1 points in the placebo group.

The largest change in apathy score occurred during the first 2 months of treatment. At 6 months, 27% of the methylphenidate group vs. 14% of the placebo group had an NPI apathy score of 0.

In addition, 43.8% of the methylphenidate group had improvement on the ADCS-CGIC compared with 35.2% of the placebo group. The odds ratio (OR) for improvement on ADCS-CGIC for methylphenidate vs. placebo was 1.90 (P = .07).

There was also a strong association between score improvement on the NPI apathy subscale and improvement on the ADCS-CGIC subscale (OR, 2.95; P = .002).

“It is important to note that there were no group differences in any of the cognitive measures, suggesting that the effect of the treatment is specific to the treatment of apathy and not a secondary effect of improvement in cognition,” the researchers wrote.

In all, 17 serious adverse events occurred in the methylphenidate group and 10 occurred in the placebo group. However, all events were found to be hospitalizations for events not related to treatment.

‘Enduring effect’

Commenting on the findings, Jeffrey L. Cummings, MD, ScD, professor of brain sciences at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, noted that the reduction in NPI apathy subscale score of more than 50% was clinically meaningful.

A more robust outcome on the ADCS-CGIC would have been desirable, he added, although that instrument is not designed specifically for apathy.

Methylphenidate’s effect on apathy observed at 2 months and remaining stable throughout the study makes it appear to be “an enduring effect, and not something that the patient accommodates to,” said Dr. Cummings, who was not involved with the research. Such a change may manifest itself in a patient’s greater willingness to help voluntarily with housework or to suggest going for a walk, he noted.

“These are not dramatic changes in cognition, of course, but they are changes in initiative and that is very important,” Dr. Cummings said. Decreased apathy also may improve quality of life for the patient’s caregiver, he added.

Overall, the findings raise the question of whether the Food and Drug Administration should recognize apathy as an indication for which drugs can be approved, said Dr. Cummings.

“For me, that would be the next major step in this line of investigation,” he concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mintzer has served as an adviser to Praxis Bioresearch and Cerevel Therapeutics on matters unrelated to this study. Dr. Cummings is the author of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory but does not receive payments for it from academic trials such as ADMET 2.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent altered mental status

CASE Sluggish, weak, and incoherent

Mr. O, age 24, who has a history of schizophrenia and obesity, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status (AMS). His mother reports that he has been sluggish, weak, incoherent, had no appetite, and that on the day before admission, he was drinking excessive amounts of water and urinating every 10 minutes.

HISTORY Multiple ineffective antipsychotics

Mr. O was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 21 and struggled with medication adherence, which resulted in multiple hospitalizations for stabilization. Trials of haloperidol, risperidone, paliperidone palmitate, and valproic acid had been ineffective. At the time of admission, his psychotropic medication regimen is fluphenazine decanoate, 25 mg injection every 2 weeks; clozapine, 50 mg/d; lithium carbonate, 300 mg twice a day; benztropine, 2 mg every night; and trazodone, 50 mg every night.

EVALUATION Fever, tachycardia, and diabetic ketoacidosis

Upon arrival to the ED, Mr. O is obtunded, unable to follow commands, and does not respond to painful stimuli. On physical exam, he has a fever of 38.4°C (reference range 35.1°C to 37.9°C); tachycardia with a heart rate of 142 beats per minute (bpm) (reference range 60 to 100); tachypnea with a respiratory rate of 35 breaths per minute (reference range 12 to 20); a blood pressure of 116/76 mmHg (reference range 90/60 to 130/80); and hypoxemia with an oxygen saturation of 90% on room air (reference range 94% to 100%).

Mr. O is admitted to the hospital and his laboratory workup indicates diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), with a glucose of 1,700 mg/dL; anion gap of 30 (reference range 4 to 12 mmol/L); pH 7.04 (reference range 7.32 to 7.42); serum bicarbonate 6 (reference range 20 to 24 mEq/L); beta-hydroxybutyrate 11.04 (reference range 0 to 0.27 mmol/L); urine ketones, serum osmolality 407 (reference range 280 to 300 mOsm/kg); and an elevated white blood cell count of 18.4 (reference range 4.5 to 11.0 × 109/L). A CT scan of the head is negative for acute pathology.

Initially, all psychotropic medications are held. On Day 3 of hospitalization, psychiatry is consulted and clozapine, 50 mg/d; lithium, 300 mg/d; and benztropine, 1 mg at night, are restarted; however, fluphenazine decanoate and trazodone are held. The team recommends IV haloperidol, 2 mg as needed for agitation; however, it is never administered.

Imaging rules out deep vein thrombosis, cardiac dysfunction, and stroke, but a CT chest scan is notable for bilateral lung infiltrates, which suggests aspiration pneumonia.

Mr. O is diagnosed with diabetes, complicated by DKA, and is treated in the intensive care unit (ICU). Despite resolution of the DKA, he remains altered with fever and tachycardia.

Continue to: On Day 6 of hospitalization...

On Day 6 of hospitalization, Mr. O continues to be tachycardic and obtunded with nuchal rigidity. The team decides to transfer Mr. O to another hospital for a higher level of care and continued workup of his persistent AMS.

Immediately upon arrival at the second hospital, infectious disease and neurology teams are consulted for further evaluation. Mr. O’s AMS continues despite no clear signs of infection or other neurologic insults.

[polldaddy:10930631]

The authors’ observations

Based on Mr. O’s psychiatric history and laboratory results, the first medical team concluded his initial AMS was likely secondary to DKA; however, the AMS continued after the DKA resolved. At the second hospital, Mr. O’s treatment team continued to dig for answers.

EVALUATION Exploring the differential diagnosis

At the second hospital, Mr. O is admitted to the ICU with fever (37.8°C), tachycardia (120 bpm), tachypnea, withdrawal from painful stimuli, decreased reflexes, and muscle rigidity, including clenched jaw. The differential diagnoses include meningitis, sepsis from aspiration pneumonia, severe metabolic encephalopathy with prolonged recovery, central pontine myelinolysis, anoxic brain injury, and subclinical seizures.

Empiric vancomycin, 1.75 g every 12 hours; ceftriaxone, 2 g/d; and acyclovir, 900 mg every 8 hours are started for meningoencephalitis, and all psychotropic medications are discontinued. Case reports have documented a relationship between hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) and malignant hyperthermia in rare cases1; however, HHS is ruled out based on Mr. O’s laboratory results.A lumbar puncture and imaging rules out CNS infection. Antibiotic treatment is narrowed to ampicillin-sulbactam due to Mr. O’s prior CT chest showing concern for aspiration pneumonia. An MRI of the brain rules out central pontine myelinolysis, acute stroke, and anoxic brain injury, and an EEG shows nonspecific encephalopathy. On Day 10 of hospitalization, a neurologic exam shows flaccid paralysis and bilateral clonus, and Mr. O is mute. On Day 14 of hospitalization, his fever resolves, and his blood cultures are negative. On Day 15 of hospitalization, Mr. O’s creatine kinase (CK) level is elevated at 1,308 U/L (reference range 26 to 192 U/L), suggesting rhabdomyolysis.

Continue to: Given the neurologic exam findings...

Given the neurologic exam findings, and the limited evidence of infection, the differential diagnosis for Mr. O’s AMS is broadened to include catatonia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), serotonin syndrome, and autoimmune encephalitis. The psychiatry team evaluates Mr. O for catatonia. He scores 14 on the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale, with findings of immobility/stupor, mutism, staring, autonomic instability, and withdrawal indicating the presence of catatonia.2

The authors’ observations

When Mr. O was transferred to the second hospital, the primary concern was to rule out meningitis due to his unstable vitals, obtunded mental state, and nuchal rigidity. A comprehensive infectious workup, including lumbar puncture, was imperative because infection can not only lead to AMS, but also precipitate episodes of DKA. Mr. O’s persistently abnormal vital signs indicated an underlying process may have been missed by focusing on treating DKA.

TREATMENT Finally, the diagnosis is established

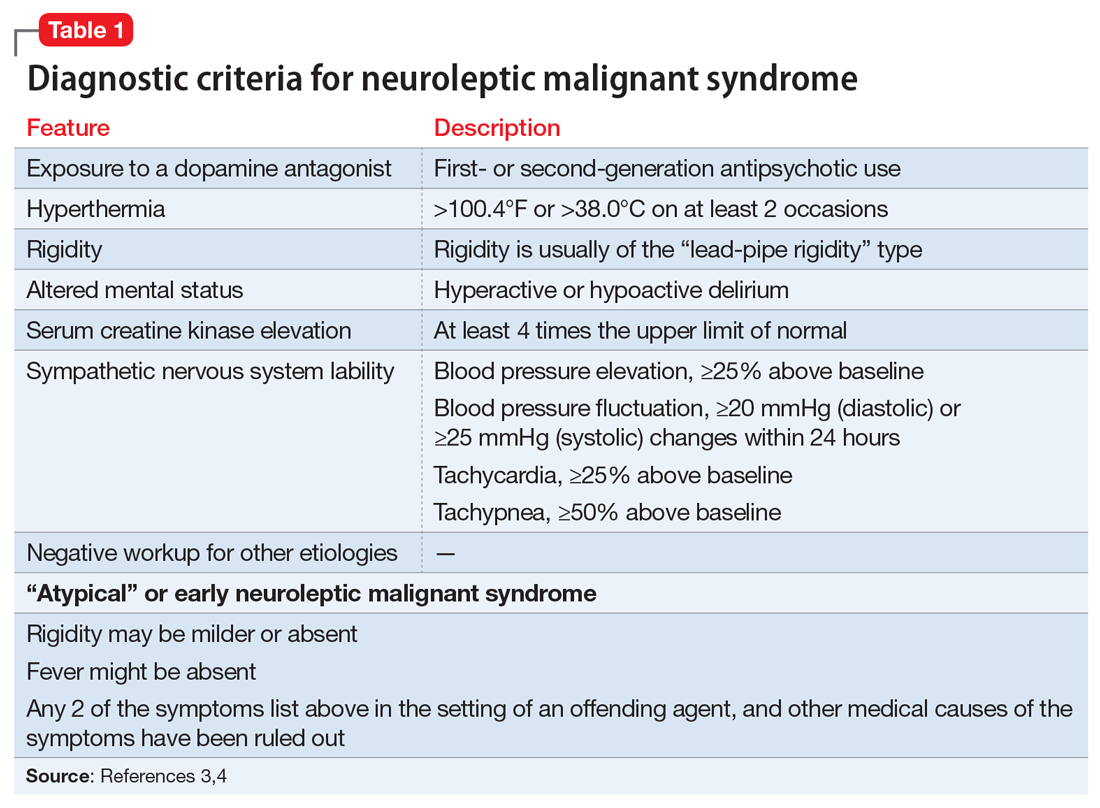

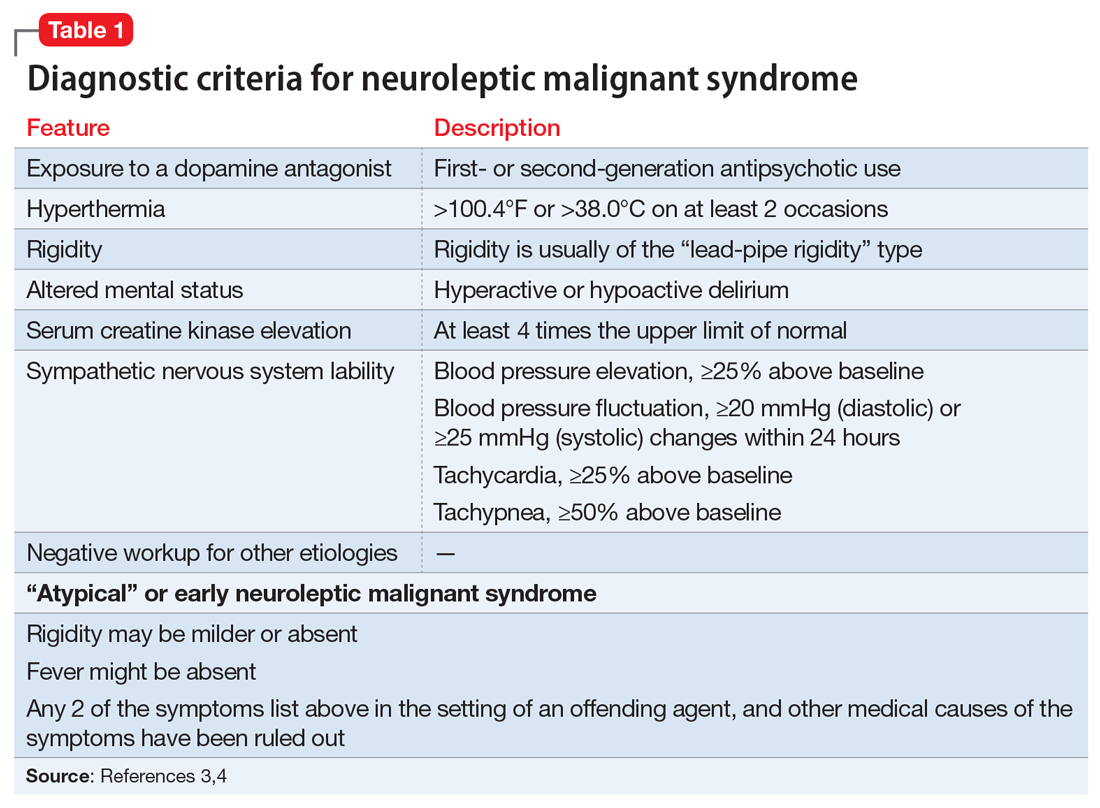

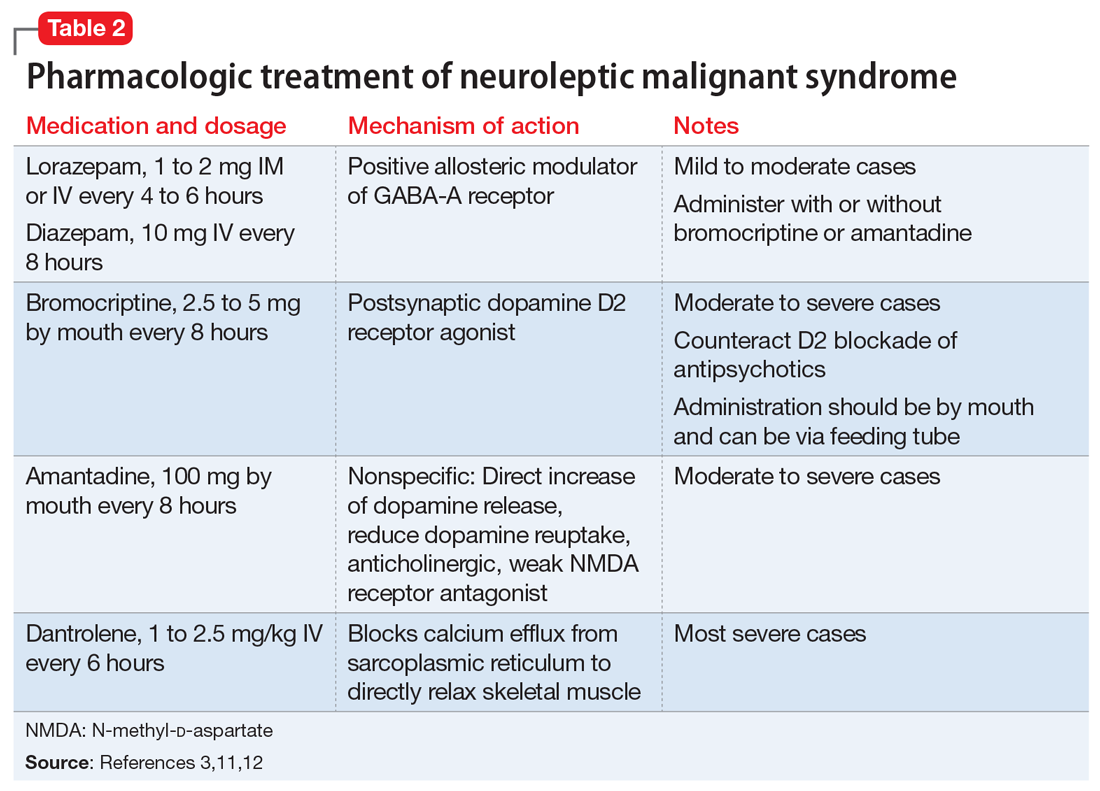

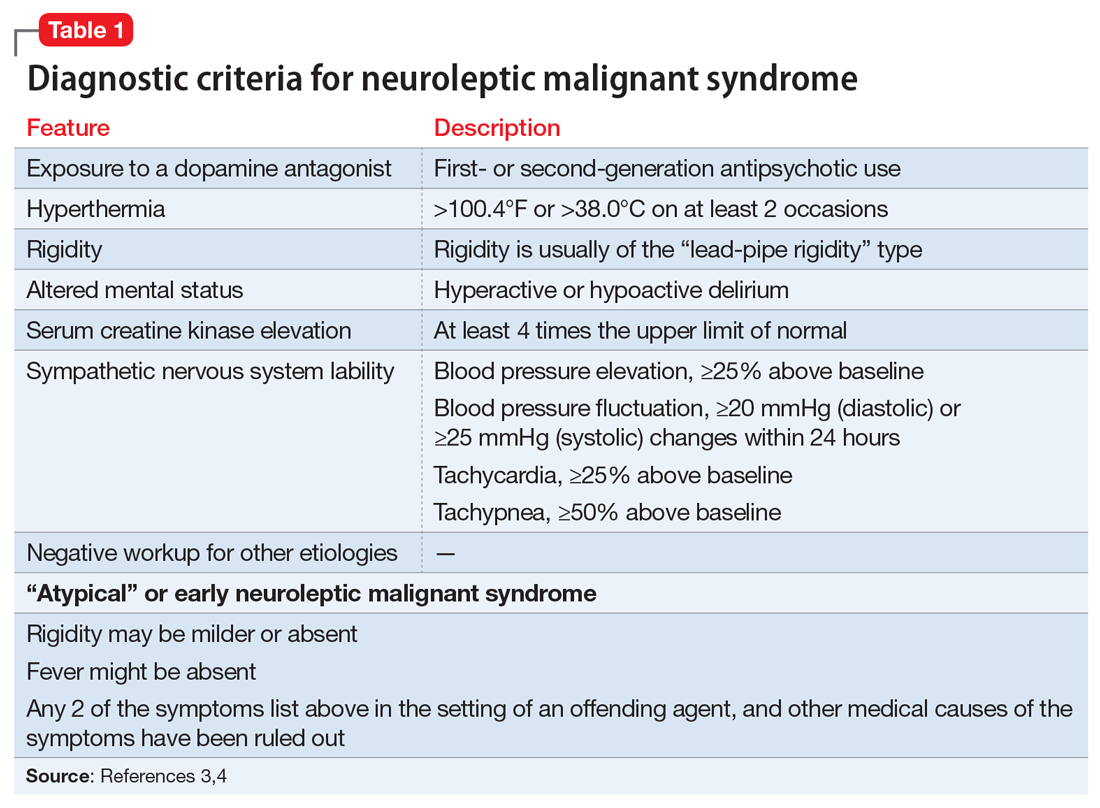

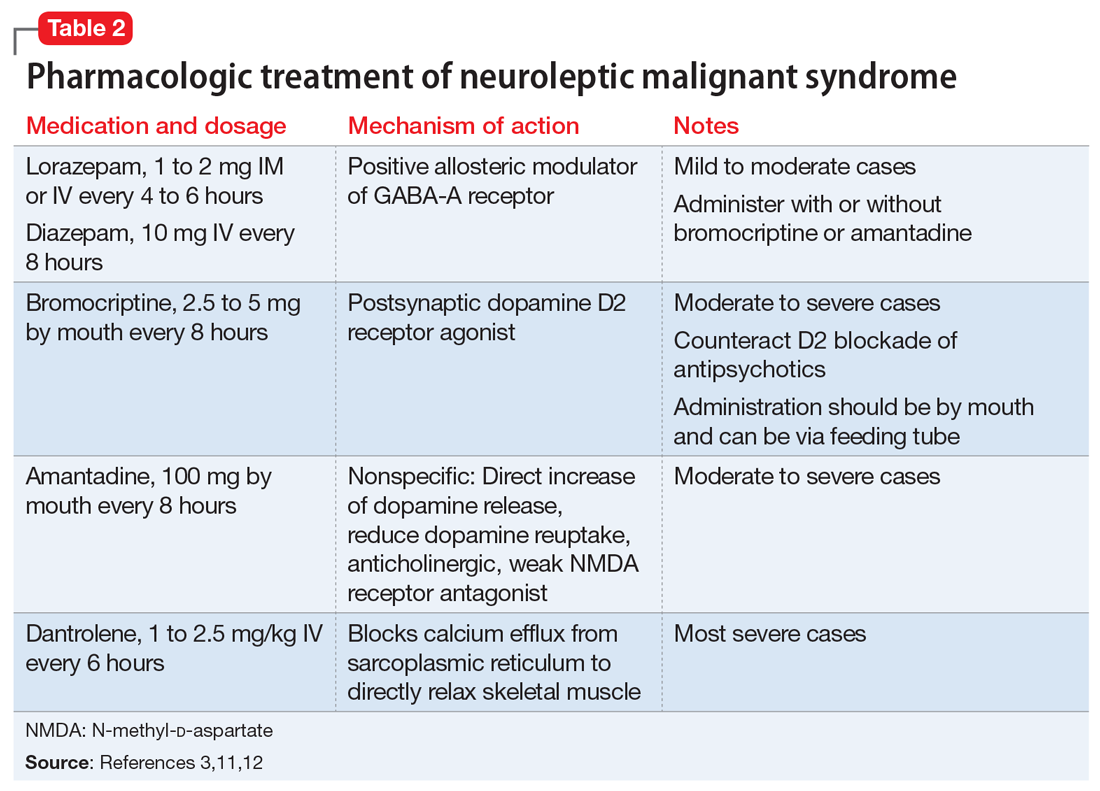

A lorazepam challenge is performed, and Mr. O receives 4 mg of lorazepam over 24 hours with little change in his catatonia symptoms. Given his persistent fever, tachycardia, and an elevated CK levels in the context of recent exposure to antipsychotic medications, Mr. O is diagnosed with NMS (Table 13,4 ) and is started on bromocriptine, 5 mg 3 times daily.

[polldaddy:10930632]

The authors’ observations

Mr. O’s complicated medical state—starting with DKA, halting the use of antipsychotic medications, and the suspicion of catatonia due to his history of schizophrenia—all distracted from the ultimate diagnosis of NMS as the cause of his enduring AMS and autonomic instability. Catatonia and NMS have overlapping symptomatology, including rigidity, autonomic instability, and stupor, which make the diagnosis of either condition complicated. A positive lorazepam test to diagnose catatonia is defined as a marked reduction in catatonia symptoms (typically a 50% reduction) as measured on a standardized rating scale.5 However, a negative lorazepam challenge does not definitely rule out catatonia because some cases are resistant to benzodiazepines.6

NMS risk factors relevant in this case include male sex, young age, acute medical illness, dehydration, and exposure to multiple psychotropic medications, including 2 antipsychotics, clozapine and fluphenazine.7 DKA is especially pertinent due to its acute onset and cause of significant dehydration. NMS can occur at any point of antipsychotic exposure, although the risk is highest during the initial weeks of treatment and during dosage changes. Unfortunately, Mr. O’s treatment team was unable to determine whether his medication had been recently changed, so it is not known what role this may have played in the development of NMS. Although first-generation antipsychotics are considered more likely to cause NMS, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) dominate the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and these medications also can cause NMS.8 As occurred in this case, long-acting injectable antipsychotics can be easily forgotten when not administered in the hospital, and their presence in the body persists for weeks. For example, the half-life of fluphenazine decanoate is approximately 10 days, and the half-life of haloperidol decanoate is 21 days.9

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement with bromocriptine

OUTCOME Improvement with bromocriptine

After 4 days of bromocriptine, 5 mg 3 times daily, Mr. O is more alert, able to say “hello,” and can follow 1-step commands. By Day 26 of hospitalization, his CK levels decrease to 296 U/L, his CSF autoimmune panel is negative, and he is able to participate in physical therapy. After failing multiple swallow tests, Mr. O requires a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. He is discharged from the hospital to a long-term acute care facility with the plan to taper bromocriptine and restart a psychotropic regimen with his outpatient psychiatrist. At the time of discharge, he is able to sit at the edge of the bed independently, state his name, and respond to questions with multiple-word answers.

[polldaddy:10930633]

The authors’ observations

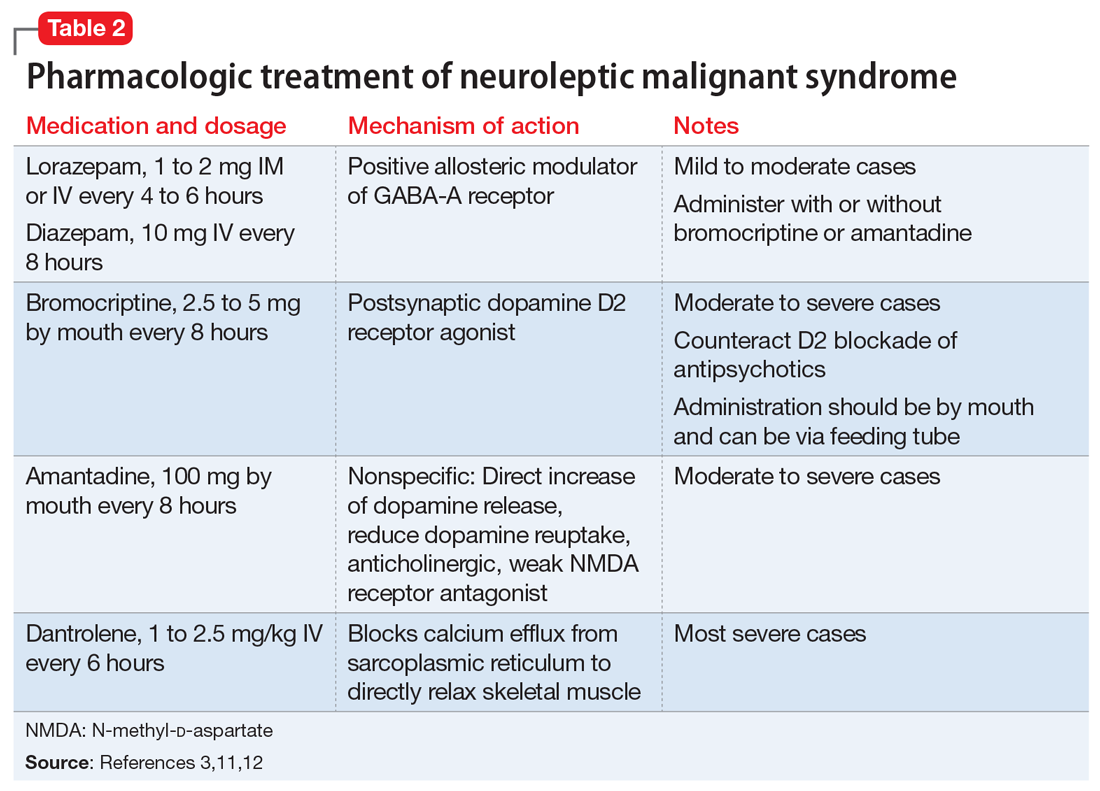

The most common pharmacologic treatments for NMS are dantrolene, bromocriptine, benzodiazepines (lorazepam or diazepam), and amantadine.3 Mild cases of NMS should be treated with discontinuation of all antipsychotics, supportive care, and benzodiazepines.3 Bromocriptine or amantadine are more appropriate for moderate cases and dantrolene for severe cases of NMS.3 All antipsychotics should be discontinued while a patient is experiencing an episode of NMS; however, once the NMS has resolved, clinicians must thoroughly evaluate the risks and benefits of restarting antipsychotic medication. After a patient has experienced an episode of NMS, clinicians generally should avoid prescribing the agent(s) that caused NMS and long-acting injections, and slowly titrate a low-potency SGA such as quetiapine.10Table 23,11,12 outlines the pharmacologic treatment of NMS.

Bottom Line

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) should always be part of the differential diagnosis in patients with mental illness and altered mental status. The risk of NMS is especially high in patients with acute medical illness and exposure to antipsychotic medications.

Related Resource

- Turner AH, Kim JJ, McCarron RM. Differentiating serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):30-36.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Amantadine • Gocovri

Ampicillin-sulbactam • Unasyn

Aripiprazole • Abilify Maintena

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Cycloset, Parlodel

Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dantrolene • Dantrium

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate sodium • Depakote

Trazodone • Oleptro

Vancomycin • Vancocin

1. Zeitler P, Haqq A, Rosenbloom A, et al. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome in children: pathophysiological considerations and suggested guidelines for treatment. J Pediatr. 2011;158(1):9-14.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.048

2. Francis A. Catatonia: diagnosis, classification, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):180-185. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0113-y

3. Pileggi DJ, Cook AM. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):973-981. doi:10.1177/1060028016657553

4. Gurrera RJ, Caroff SN, Cohen A, et al. An international consensus study of neuroleptic malignant syndrome diagnostic criteria using the Delphi method. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1222-1228. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06438

5. Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:181. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00181

6. Daniels J. Catatonia: clinical aspects and neurobiological correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21(4):371-380. doi:10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.371

7. Bhanushali MJ, Tuite PJ. The evaluation and management of patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(2):389-411. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2003.12.006

8. Tse L, Barr AM, Scarapicchia V, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review from a clinically oriented perspective. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(3):395-406. doi:10.2174/1570159x13999150424113345

9. Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39-59. doi:10.1007/s40263-020-00779-5

10. Strawn JR, Keck PE Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.870

11. Griffin CE 3rd, Kaye AM, Bueno FR, et al. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system-mediated effects. Ochsner J. 2013;13(2):214-223.

12. Reulbach U, Dütsch C, Biermann T, et al. Managing an effective treatment for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R4. doi:10.1186/cc5148

CASE Sluggish, weak, and incoherent

Mr. O, age 24, who has a history of schizophrenia and obesity, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status (AMS). His mother reports that he has been sluggish, weak, incoherent, had no appetite, and that on the day before admission, he was drinking excessive amounts of water and urinating every 10 minutes.

HISTORY Multiple ineffective antipsychotics

Mr. O was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 21 and struggled with medication adherence, which resulted in multiple hospitalizations for stabilization. Trials of haloperidol, risperidone, paliperidone palmitate, and valproic acid had been ineffective. At the time of admission, his psychotropic medication regimen is fluphenazine decanoate, 25 mg injection every 2 weeks; clozapine, 50 mg/d; lithium carbonate, 300 mg twice a day; benztropine, 2 mg every night; and trazodone, 50 mg every night.

EVALUATION Fever, tachycardia, and diabetic ketoacidosis

Upon arrival to the ED, Mr. O is obtunded, unable to follow commands, and does not respond to painful stimuli. On physical exam, he has a fever of 38.4°C (reference range 35.1°C to 37.9°C); tachycardia with a heart rate of 142 beats per minute (bpm) (reference range 60 to 100); tachypnea with a respiratory rate of 35 breaths per minute (reference range 12 to 20); a blood pressure of 116/76 mmHg (reference range 90/60 to 130/80); and hypoxemia with an oxygen saturation of 90% on room air (reference range 94% to 100%).

Mr. O is admitted to the hospital and his laboratory workup indicates diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), with a glucose of 1,700 mg/dL; anion gap of 30 (reference range 4 to 12 mmol/L); pH 7.04 (reference range 7.32 to 7.42); serum bicarbonate 6 (reference range 20 to 24 mEq/L); beta-hydroxybutyrate 11.04 (reference range 0 to 0.27 mmol/L); urine ketones, serum osmolality 407 (reference range 280 to 300 mOsm/kg); and an elevated white blood cell count of 18.4 (reference range 4.5 to 11.0 × 109/L). A CT scan of the head is negative for acute pathology.

Initially, all psychotropic medications are held. On Day 3 of hospitalization, psychiatry is consulted and clozapine, 50 mg/d; lithium, 300 mg/d; and benztropine, 1 mg at night, are restarted; however, fluphenazine decanoate and trazodone are held. The team recommends IV haloperidol, 2 mg as needed for agitation; however, it is never administered.

Imaging rules out deep vein thrombosis, cardiac dysfunction, and stroke, but a CT chest scan is notable for bilateral lung infiltrates, which suggests aspiration pneumonia.

Mr. O is diagnosed with diabetes, complicated by DKA, and is treated in the intensive care unit (ICU). Despite resolution of the DKA, he remains altered with fever and tachycardia.

Continue to: On Day 6 of hospitalization...

On Day 6 of hospitalization, Mr. O continues to be tachycardic and obtunded with nuchal rigidity. The team decides to transfer Mr. O to another hospital for a higher level of care and continued workup of his persistent AMS.

Immediately upon arrival at the second hospital, infectious disease and neurology teams are consulted for further evaluation. Mr. O’s AMS continues despite no clear signs of infection or other neurologic insults.

[polldaddy:10930631]

The authors’ observations

Based on Mr. O’s psychiatric history and laboratory results, the first medical team concluded his initial AMS was likely secondary to DKA; however, the AMS continued after the DKA resolved. At the second hospital, Mr. O’s treatment team continued to dig for answers.

EVALUATION Exploring the differential diagnosis

At the second hospital, Mr. O is admitted to the ICU with fever (37.8°C), tachycardia (120 bpm), tachypnea, withdrawal from painful stimuli, decreased reflexes, and muscle rigidity, including clenched jaw. The differential diagnoses include meningitis, sepsis from aspiration pneumonia, severe metabolic encephalopathy with prolonged recovery, central pontine myelinolysis, anoxic brain injury, and subclinical seizures.

Empiric vancomycin, 1.75 g every 12 hours; ceftriaxone, 2 g/d; and acyclovir, 900 mg every 8 hours are started for meningoencephalitis, and all psychotropic medications are discontinued. Case reports have documented a relationship between hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) and malignant hyperthermia in rare cases1; however, HHS is ruled out based on Mr. O’s laboratory results.A lumbar puncture and imaging rules out CNS infection. Antibiotic treatment is narrowed to ampicillin-sulbactam due to Mr. O’s prior CT chest showing concern for aspiration pneumonia. An MRI of the brain rules out central pontine myelinolysis, acute stroke, and anoxic brain injury, and an EEG shows nonspecific encephalopathy. On Day 10 of hospitalization, a neurologic exam shows flaccid paralysis and bilateral clonus, and Mr. O is mute. On Day 14 of hospitalization, his fever resolves, and his blood cultures are negative. On Day 15 of hospitalization, Mr. O’s creatine kinase (CK) level is elevated at 1,308 U/L (reference range 26 to 192 U/L), suggesting rhabdomyolysis.

Continue to: Given the neurologic exam findings...

Given the neurologic exam findings, and the limited evidence of infection, the differential diagnosis for Mr. O’s AMS is broadened to include catatonia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), serotonin syndrome, and autoimmune encephalitis. The psychiatry team evaluates Mr. O for catatonia. He scores 14 on the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale, with findings of immobility/stupor, mutism, staring, autonomic instability, and withdrawal indicating the presence of catatonia.2

The authors’ observations

When Mr. O was transferred to the second hospital, the primary concern was to rule out meningitis due to his unstable vitals, obtunded mental state, and nuchal rigidity. A comprehensive infectious workup, including lumbar puncture, was imperative because infection can not only lead to AMS, but also precipitate episodes of DKA. Mr. O’s persistently abnormal vital signs indicated an underlying process may have been missed by focusing on treating DKA.

TREATMENT Finally, the diagnosis is established

A lorazepam challenge is performed, and Mr. O receives 4 mg of lorazepam over 24 hours with little change in his catatonia symptoms. Given his persistent fever, tachycardia, and an elevated CK levels in the context of recent exposure to antipsychotic medications, Mr. O is diagnosed with NMS (Table 13,4 ) and is started on bromocriptine, 5 mg 3 times daily.

[polldaddy:10930632]

The authors’ observations

Mr. O’s complicated medical state—starting with DKA, halting the use of antipsychotic medications, and the suspicion of catatonia due to his history of schizophrenia—all distracted from the ultimate diagnosis of NMS as the cause of his enduring AMS and autonomic instability. Catatonia and NMS have overlapping symptomatology, including rigidity, autonomic instability, and stupor, which make the diagnosis of either condition complicated. A positive lorazepam test to diagnose catatonia is defined as a marked reduction in catatonia symptoms (typically a 50% reduction) as measured on a standardized rating scale.5 However, a negative lorazepam challenge does not definitely rule out catatonia because some cases are resistant to benzodiazepines.6

NMS risk factors relevant in this case include male sex, young age, acute medical illness, dehydration, and exposure to multiple psychotropic medications, including 2 antipsychotics, clozapine and fluphenazine.7 DKA is especially pertinent due to its acute onset and cause of significant dehydration. NMS can occur at any point of antipsychotic exposure, although the risk is highest during the initial weeks of treatment and during dosage changes. Unfortunately, Mr. O’s treatment team was unable to determine whether his medication had been recently changed, so it is not known what role this may have played in the development of NMS. Although first-generation antipsychotics are considered more likely to cause NMS, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) dominate the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and these medications also can cause NMS.8 As occurred in this case, long-acting injectable antipsychotics can be easily forgotten when not administered in the hospital, and their presence in the body persists for weeks. For example, the half-life of fluphenazine decanoate is approximately 10 days, and the half-life of haloperidol decanoate is 21 days.9

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement with bromocriptine

OUTCOME Improvement with bromocriptine

After 4 days of bromocriptine, 5 mg 3 times daily, Mr. O is more alert, able to say “hello,” and can follow 1-step commands. By Day 26 of hospitalization, his CK levels decrease to 296 U/L, his CSF autoimmune panel is negative, and he is able to participate in physical therapy. After failing multiple swallow tests, Mr. O requires a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. He is discharged from the hospital to a long-term acute care facility with the plan to taper bromocriptine and restart a psychotropic regimen with his outpatient psychiatrist. At the time of discharge, he is able to sit at the edge of the bed independently, state his name, and respond to questions with multiple-word answers.

[polldaddy:10930633]

The authors’ observations

The most common pharmacologic treatments for NMS are dantrolene, bromocriptine, benzodiazepines (lorazepam or diazepam), and amantadine.3 Mild cases of NMS should be treated with discontinuation of all antipsychotics, supportive care, and benzodiazepines.3 Bromocriptine or amantadine are more appropriate for moderate cases and dantrolene for severe cases of NMS.3 All antipsychotics should be discontinued while a patient is experiencing an episode of NMS; however, once the NMS has resolved, clinicians must thoroughly evaluate the risks and benefits of restarting antipsychotic medication. After a patient has experienced an episode of NMS, clinicians generally should avoid prescribing the agent(s) that caused NMS and long-acting injections, and slowly titrate a low-potency SGA such as quetiapine.10Table 23,11,12 outlines the pharmacologic treatment of NMS.

Bottom Line

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) should always be part of the differential diagnosis in patients with mental illness and altered mental status. The risk of NMS is especially high in patients with acute medical illness and exposure to antipsychotic medications.

Related Resource

- Turner AH, Kim JJ, McCarron RM. Differentiating serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):30-36.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Amantadine • Gocovri

Ampicillin-sulbactam • Unasyn

Aripiprazole • Abilify Maintena

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Cycloset, Parlodel

Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dantrolene • Dantrium

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate sodium • Depakote

Trazodone • Oleptro

Vancomycin • Vancocin

CASE Sluggish, weak, and incoherent

Mr. O, age 24, who has a history of schizophrenia and obesity, presents to the emergency department (ED) for altered mental status (AMS). His mother reports that he has been sluggish, weak, incoherent, had no appetite, and that on the day before admission, he was drinking excessive amounts of water and urinating every 10 minutes.

HISTORY Multiple ineffective antipsychotics

Mr. O was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 21 and struggled with medication adherence, which resulted in multiple hospitalizations for stabilization. Trials of haloperidol, risperidone, paliperidone palmitate, and valproic acid had been ineffective. At the time of admission, his psychotropic medication regimen is fluphenazine decanoate, 25 mg injection every 2 weeks; clozapine, 50 mg/d; lithium carbonate, 300 mg twice a day; benztropine, 2 mg every night; and trazodone, 50 mg every night.

EVALUATION Fever, tachycardia, and diabetic ketoacidosis

Upon arrival to the ED, Mr. O is obtunded, unable to follow commands, and does not respond to painful stimuli. On physical exam, he has a fever of 38.4°C (reference range 35.1°C to 37.9°C); tachycardia with a heart rate of 142 beats per minute (bpm) (reference range 60 to 100); tachypnea with a respiratory rate of 35 breaths per minute (reference range 12 to 20); a blood pressure of 116/76 mmHg (reference range 90/60 to 130/80); and hypoxemia with an oxygen saturation of 90% on room air (reference range 94% to 100%).

Mr. O is admitted to the hospital and his laboratory workup indicates diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), with a glucose of 1,700 mg/dL; anion gap of 30 (reference range 4 to 12 mmol/L); pH 7.04 (reference range 7.32 to 7.42); serum bicarbonate 6 (reference range 20 to 24 mEq/L); beta-hydroxybutyrate 11.04 (reference range 0 to 0.27 mmol/L); urine ketones, serum osmolality 407 (reference range 280 to 300 mOsm/kg); and an elevated white blood cell count of 18.4 (reference range 4.5 to 11.0 × 109/L). A CT scan of the head is negative for acute pathology.

Initially, all psychotropic medications are held. On Day 3 of hospitalization, psychiatry is consulted and clozapine, 50 mg/d; lithium, 300 mg/d; and benztropine, 1 mg at night, are restarted; however, fluphenazine decanoate and trazodone are held. The team recommends IV haloperidol, 2 mg as needed for agitation; however, it is never administered.

Imaging rules out deep vein thrombosis, cardiac dysfunction, and stroke, but a CT chest scan is notable for bilateral lung infiltrates, which suggests aspiration pneumonia.

Mr. O is diagnosed with diabetes, complicated by DKA, and is treated in the intensive care unit (ICU). Despite resolution of the DKA, he remains altered with fever and tachycardia.

Continue to: On Day 6 of hospitalization...

On Day 6 of hospitalization, Mr. O continues to be tachycardic and obtunded with nuchal rigidity. The team decides to transfer Mr. O to another hospital for a higher level of care and continued workup of his persistent AMS.

Immediately upon arrival at the second hospital, infectious disease and neurology teams are consulted for further evaluation. Mr. O’s AMS continues despite no clear signs of infection or other neurologic insults.

[polldaddy:10930631]

The authors’ observations

Based on Mr. O’s psychiatric history and laboratory results, the first medical team concluded his initial AMS was likely secondary to DKA; however, the AMS continued after the DKA resolved. At the second hospital, Mr. O’s treatment team continued to dig for answers.

EVALUATION Exploring the differential diagnosis

At the second hospital, Mr. O is admitted to the ICU with fever (37.8°C), tachycardia (120 bpm), tachypnea, withdrawal from painful stimuli, decreased reflexes, and muscle rigidity, including clenched jaw. The differential diagnoses include meningitis, sepsis from aspiration pneumonia, severe metabolic encephalopathy with prolonged recovery, central pontine myelinolysis, anoxic brain injury, and subclinical seizures.

Empiric vancomycin, 1.75 g every 12 hours; ceftriaxone, 2 g/d; and acyclovir, 900 mg every 8 hours are started for meningoencephalitis, and all psychotropic medications are discontinued. Case reports have documented a relationship between hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) and malignant hyperthermia in rare cases1; however, HHS is ruled out based on Mr. O’s laboratory results.A lumbar puncture and imaging rules out CNS infection. Antibiotic treatment is narrowed to ampicillin-sulbactam due to Mr. O’s prior CT chest showing concern for aspiration pneumonia. An MRI of the brain rules out central pontine myelinolysis, acute stroke, and anoxic brain injury, and an EEG shows nonspecific encephalopathy. On Day 10 of hospitalization, a neurologic exam shows flaccid paralysis and bilateral clonus, and Mr. O is mute. On Day 14 of hospitalization, his fever resolves, and his blood cultures are negative. On Day 15 of hospitalization, Mr. O’s creatine kinase (CK) level is elevated at 1,308 U/L (reference range 26 to 192 U/L), suggesting rhabdomyolysis.

Continue to: Given the neurologic exam findings...

Given the neurologic exam findings, and the limited evidence of infection, the differential diagnosis for Mr. O’s AMS is broadened to include catatonia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), serotonin syndrome, and autoimmune encephalitis. The psychiatry team evaluates Mr. O for catatonia. He scores 14 on the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale, with findings of immobility/stupor, mutism, staring, autonomic instability, and withdrawal indicating the presence of catatonia.2

The authors’ observations

When Mr. O was transferred to the second hospital, the primary concern was to rule out meningitis due to his unstable vitals, obtunded mental state, and nuchal rigidity. A comprehensive infectious workup, including lumbar puncture, was imperative because infection can not only lead to AMS, but also precipitate episodes of DKA. Mr. O’s persistently abnormal vital signs indicated an underlying process may have been missed by focusing on treating DKA.

TREATMENT Finally, the diagnosis is established

A lorazepam challenge is performed, and Mr. O receives 4 mg of lorazepam over 24 hours with little change in his catatonia symptoms. Given his persistent fever, tachycardia, and an elevated CK levels in the context of recent exposure to antipsychotic medications, Mr. O is diagnosed with NMS (Table 13,4 ) and is started on bromocriptine, 5 mg 3 times daily.

[polldaddy:10930632]

The authors’ observations

Mr. O’s complicated medical state—starting with DKA, halting the use of antipsychotic medications, and the suspicion of catatonia due to his history of schizophrenia—all distracted from the ultimate diagnosis of NMS as the cause of his enduring AMS and autonomic instability. Catatonia and NMS have overlapping symptomatology, including rigidity, autonomic instability, and stupor, which make the diagnosis of either condition complicated. A positive lorazepam test to diagnose catatonia is defined as a marked reduction in catatonia symptoms (typically a 50% reduction) as measured on a standardized rating scale.5 However, a negative lorazepam challenge does not definitely rule out catatonia because some cases are resistant to benzodiazepines.6

NMS risk factors relevant in this case include male sex, young age, acute medical illness, dehydration, and exposure to multiple psychotropic medications, including 2 antipsychotics, clozapine and fluphenazine.7 DKA is especially pertinent due to its acute onset and cause of significant dehydration. NMS can occur at any point of antipsychotic exposure, although the risk is highest during the initial weeks of treatment and during dosage changes. Unfortunately, Mr. O’s treatment team was unable to determine whether his medication had been recently changed, so it is not known what role this may have played in the development of NMS. Although first-generation antipsychotics are considered more likely to cause NMS, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) dominate the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and these medications also can cause NMS.8 As occurred in this case, long-acting injectable antipsychotics can be easily forgotten when not administered in the hospital, and their presence in the body persists for weeks. For example, the half-life of fluphenazine decanoate is approximately 10 days, and the half-life of haloperidol decanoate is 21 days.9

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement with bromocriptine

OUTCOME Improvement with bromocriptine

After 4 days of bromocriptine, 5 mg 3 times daily, Mr. O is more alert, able to say “hello,” and can follow 1-step commands. By Day 26 of hospitalization, his CK levels decrease to 296 U/L, his CSF autoimmune panel is negative, and he is able to participate in physical therapy. After failing multiple swallow tests, Mr. O requires a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. He is discharged from the hospital to a long-term acute care facility with the plan to taper bromocriptine and restart a psychotropic regimen with his outpatient psychiatrist. At the time of discharge, he is able to sit at the edge of the bed independently, state his name, and respond to questions with multiple-word answers.

[polldaddy:10930633]

The authors’ observations

The most common pharmacologic treatments for NMS are dantrolene, bromocriptine, benzodiazepines (lorazepam or diazepam), and amantadine.3 Mild cases of NMS should be treated with discontinuation of all antipsychotics, supportive care, and benzodiazepines.3 Bromocriptine or amantadine are more appropriate for moderate cases and dantrolene for severe cases of NMS.3 All antipsychotics should be discontinued while a patient is experiencing an episode of NMS; however, once the NMS has resolved, clinicians must thoroughly evaluate the risks and benefits of restarting antipsychotic medication. After a patient has experienced an episode of NMS, clinicians generally should avoid prescribing the agent(s) that caused NMS and long-acting injections, and slowly titrate a low-potency SGA such as quetiapine.10Table 23,11,12 outlines the pharmacologic treatment of NMS.

Bottom Line

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) should always be part of the differential diagnosis in patients with mental illness and altered mental status. The risk of NMS is especially high in patients with acute medical illness and exposure to antipsychotic medications.

Related Resource

- Turner AH, Kim JJ, McCarron RM. Differentiating serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):30-36.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Amantadine • Gocovri

Ampicillin-sulbactam • Unasyn

Aripiprazole • Abilify Maintena

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Cycloset, Parlodel

Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Dantrolene • Dantrium

Diazepam • Valium

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate sodium • Depakote

Trazodone • Oleptro

Vancomycin • Vancocin

1. Zeitler P, Haqq A, Rosenbloom A, et al. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome in children: pathophysiological considerations and suggested guidelines for treatment. J Pediatr. 2011;158(1):9-14.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.048

2. Francis A. Catatonia: diagnosis, classification, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):180-185. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0113-y

3. Pileggi DJ, Cook AM. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):973-981. doi:10.1177/1060028016657553

4. Gurrera RJ, Caroff SN, Cohen A, et al. An international consensus study of neuroleptic malignant syndrome diagnostic criteria using the Delphi method. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1222-1228. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06438

5. Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:181. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00181

6. Daniels J. Catatonia: clinical aspects and neurobiological correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21(4):371-380. doi:10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.371

7. Bhanushali MJ, Tuite PJ. The evaluation and management of patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(2):389-411. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2003.12.006

8. Tse L, Barr AM, Scarapicchia V, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review from a clinically oriented perspective. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(3):395-406. doi:10.2174/1570159x13999150424113345

9. Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39-59. doi:10.1007/s40263-020-00779-5

10. Strawn JR, Keck PE Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.870

11. Griffin CE 3rd, Kaye AM, Bueno FR, et al. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system-mediated effects. Ochsner J. 2013;13(2):214-223.

12. Reulbach U, Dütsch C, Biermann T, et al. Managing an effective treatment for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R4. doi:10.1186/cc5148

1. Zeitler P, Haqq A, Rosenbloom A, et al. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome in children: pathophysiological considerations and suggested guidelines for treatment. J Pediatr. 2011;158(1):9-14.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.048

2. Francis A. Catatonia: diagnosis, classification, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):180-185. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0113-y

3. Pileggi DJ, Cook AM. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):973-981. doi:10.1177/1060028016657553

4. Gurrera RJ, Caroff SN, Cohen A, et al. An international consensus study of neuroleptic malignant syndrome diagnostic criteria using the Delphi method. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1222-1228. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06438

5. Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:181. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00181

6. Daniels J. Catatonia: clinical aspects and neurobiological correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21(4):371-380. doi:10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.371

7. Bhanushali MJ, Tuite PJ. The evaluation and management of patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(2):389-411. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2003.12.006

8. Tse L, Barr AM, Scarapicchia V, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review from a clinically oriented perspective. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(3):395-406. doi:10.2174/1570159x13999150424113345

9. Correll CU, Kim E, Sliwa JK, et al. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for schizophrenia: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(1):39-59. doi:10.1007/s40263-020-00779-5

10. Strawn JR, Keck PE Jr, Caroff SN. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):870-876. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.870

11. Griffin CE 3rd, Kaye AM, Bueno FR, et al. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system-mediated effects. Ochsner J. 2013;13(2):214-223.

12. Reulbach U, Dütsch C, Biermann T, et al. Managing an effective treatment for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R4. doi:10.1186/cc5148

MIND diet preserves cognition, new data show

Adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, new data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) show.

“The MIND diet was associated with better cognitive functions independently of brain pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that diet may contribute to cognitive resilience, which ultimately indicates that it is never too late for dementia prevention,” lead author Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, with the Rush Institute of Healthy Aging at Rush University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The study was published online Sept. 14, 2021, in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Impact on brain pathology

“While previous investigations determined that the MIND diet is associated with a slower cognitive decline, the current study furthered the diet and brain health evidence by assessing the impact of brain pathology in the diet-cognition relationship,” Dr. Dhana said.

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died in 2020 of cancer at age 64. A hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, the MIND diet includes green leafy vegetables, fish, nuts, berries, beans, and whole grains and limits consumption of fried and fast foods, sweets, and pastries.

The current study focused on 569 older adults who died while participating in the MAP study, which began in 1997. Participants in the study were mostly White and were without known dementia. All of the participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations. They also agreed to undergo brain autopsy after death.

Beginning in 2004, participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires, which were used to calculate a MIND diet score based on how often the participants ate specific foods.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to examine associations of the MIND diet, dementia-related brain pathologies, and global cognition near the time of death. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, apo E4, late-life cognitive activities, and total energy intake.

(beta, 0.119; P = .003).

Notably, the researchers said, neither the strength nor the significance of association changed markedly when AD pathology and other brain pathologies were included in the model (beta, 0.111; P = .003).

The relationship between better adherence to the MIND diet and better cognition remained significant when the analysis was restricted to individuals without mild cognitive impairment at baseline (beta, 0.121; P = .005) as well as to persons in whom a postmortem diagnosis of AD was made on the basis of NIA-Reagan consensus recommendations (beta, 0.114; P = .023).

The limitations of the study include the reliance on self-reported diet information and a sample made up of mostly White volunteers who agreed to annual evaluations and postmortem organ donation, thus limiting generalizability.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design with annual assessment of cognitive function using standardized tests and collection of the dietary information using validated questionnaires. Also, the neuropathologic evaluations were performed by examiners blinded to clinical data.

“Diet changes can impact cognitive functioning and risk of dementia, for better or worse. There are fairly simple diet and lifestyle changes a person could make that may help to slow cognitive decline with aging and contribute to brain health,” Dr. Dhana said in a news release.

Builds resilience

Weighing in on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this “interesting study sheds light on the impact of nutrition on cognitive function.

“The findings add to the growing literature that lifestyle factors – like access to a heart-healthy diet – may help the brain be more resilient to disease-specific changes,” Snyder said in an interview.

“The Alzheimer’s Association’s US POINTER study is investigating how lifestyle interventions, including nutrition guidance, like the MIND diet, may impact a person’s risk of cognitive decline. An ancillary study of the US POINTER will include brain imaging to investigate how these lifestyle interventions impact the biology of the brain,” Dr. Snyder noted.

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dhana and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, new data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) show.

“The MIND diet was associated with better cognitive functions independently of brain pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that diet may contribute to cognitive resilience, which ultimately indicates that it is never too late for dementia prevention,” lead author Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, with the Rush Institute of Healthy Aging at Rush University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The study was published online Sept. 14, 2021, in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Impact on brain pathology

“While previous investigations determined that the MIND diet is associated with a slower cognitive decline, the current study furthered the diet and brain health evidence by assessing the impact of brain pathology in the diet-cognition relationship,” Dr. Dhana said.

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died in 2020 of cancer at age 64. A hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, the MIND diet includes green leafy vegetables, fish, nuts, berries, beans, and whole grains and limits consumption of fried and fast foods, sweets, and pastries.

The current study focused on 569 older adults who died while participating in the MAP study, which began in 1997. Participants in the study were mostly White and were without known dementia. All of the participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations. They also agreed to undergo brain autopsy after death.

Beginning in 2004, participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires, which were used to calculate a MIND diet score based on how often the participants ate specific foods.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to examine associations of the MIND diet, dementia-related brain pathologies, and global cognition near the time of death. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, apo E4, late-life cognitive activities, and total energy intake.

(beta, 0.119; P = .003).

Notably, the researchers said, neither the strength nor the significance of association changed markedly when AD pathology and other brain pathologies were included in the model (beta, 0.111; P = .003).

The relationship between better adherence to the MIND diet and better cognition remained significant when the analysis was restricted to individuals without mild cognitive impairment at baseline (beta, 0.121; P = .005) as well as to persons in whom a postmortem diagnosis of AD was made on the basis of NIA-Reagan consensus recommendations (beta, 0.114; P = .023).

The limitations of the study include the reliance on self-reported diet information and a sample made up of mostly White volunteers who agreed to annual evaluations and postmortem organ donation, thus limiting generalizability.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design with annual assessment of cognitive function using standardized tests and collection of the dietary information using validated questionnaires. Also, the neuropathologic evaluations were performed by examiners blinded to clinical data.

“Diet changes can impact cognitive functioning and risk of dementia, for better or worse. There are fairly simple diet and lifestyle changes a person could make that may help to slow cognitive decline with aging and contribute to brain health,” Dr. Dhana said in a news release.

Builds resilience

Weighing in on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this “interesting study sheds light on the impact of nutrition on cognitive function.

“The findings add to the growing literature that lifestyle factors – like access to a heart-healthy diet – may help the brain be more resilient to disease-specific changes,” Snyder said in an interview.

“The Alzheimer’s Association’s US POINTER study is investigating how lifestyle interventions, including nutrition guidance, like the MIND diet, may impact a person’s risk of cognitive decline. An ancillary study of the US POINTER will include brain imaging to investigate how these lifestyle interventions impact the biology of the brain,” Dr. Snyder noted.

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dhana and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adherence to the MIND diet can improve memory and thinking skills of older adults, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, new data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) show.

“The MIND diet was associated with better cognitive functions independently of brain pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that diet may contribute to cognitive resilience, which ultimately indicates that it is never too late for dementia prevention,” lead author Klodian Dhana, MD, PhD, with the Rush Institute of Healthy Aging at Rush University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The study was published online Sept. 14, 2021, in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Impact on brain pathology

“While previous investigations determined that the MIND diet is associated with a slower cognitive decline, the current study furthered the diet and brain health evidence by assessing the impact of brain pathology in the diet-cognition relationship,” Dr. Dhana said.

The MIND diet was pioneered by the late Martha Clare Morris, ScD, a Rush nutritional epidemiologist, who died in 2020 of cancer at age 64. A hybrid of the Mediterranean and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, the MIND diet includes green leafy vegetables, fish, nuts, berries, beans, and whole grains and limits consumption of fried and fast foods, sweets, and pastries.

The current study focused on 569 older adults who died while participating in the MAP study, which began in 1997. Participants in the study were mostly White and were without known dementia. All of the participants agreed to undergo annual clinical evaluations. They also agreed to undergo brain autopsy after death.

Beginning in 2004, participants completed annual food frequency questionnaires, which were used to calculate a MIND diet score based on how often the participants ate specific foods.

The researchers used a series of regression analyses to examine associations of the MIND diet, dementia-related brain pathologies, and global cognition near the time of death. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, apo E4, late-life cognitive activities, and total energy intake.

(beta, 0.119; P = .003).

Notably, the researchers said, neither the strength nor the significance of association changed markedly when AD pathology and other brain pathologies were included in the model (beta, 0.111; P = .003).

The relationship between better adherence to the MIND diet and better cognition remained significant when the analysis was restricted to individuals without mild cognitive impairment at baseline (beta, 0.121; P = .005) as well as to persons in whom a postmortem diagnosis of AD was made on the basis of NIA-Reagan consensus recommendations (beta, 0.114; P = .023).

The limitations of the study include the reliance on self-reported diet information and a sample made up of mostly White volunteers who agreed to annual evaluations and postmortem organ donation, thus limiting generalizability.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design with annual assessment of cognitive function using standardized tests and collection of the dietary information using validated questionnaires. Also, the neuropathologic evaluations were performed by examiners blinded to clinical data.

“Diet changes can impact cognitive functioning and risk of dementia, for better or worse. There are fairly simple diet and lifestyle changes a person could make that may help to slow cognitive decline with aging and contribute to brain health,” Dr. Dhana said in a news release.

Builds resilience

Weighing in on the study, Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association, said this “interesting study sheds light on the impact of nutrition on cognitive function.

“The findings add to the growing literature that lifestyle factors – like access to a heart-healthy diet – may help the brain be more resilient to disease-specific changes,” Snyder said in an interview.

“The Alzheimer’s Association’s US POINTER study is investigating how lifestyle interventions, including nutrition guidance, like the MIND diet, may impact a person’s risk of cognitive decline. An ancillary study of the US POINTER will include brain imaging to investigate how these lifestyle interventions impact the biology of the brain,” Dr. Snyder noted.

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dhana and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sexual assault in women tied to increased stroke, dementia risk

Traumatic experiences, especially sexual assault, may put women at greater risk for poor brain health.

In the Ms Brain study, middle-aged women with trauma exposure had a greater volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) than those without trauma. In addition, the differences persisted even after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

WMHs are “an important indicator of small vessel disease in the brain and have been linked to future stroke risk, dementia risk, and mortality,” lead investigator Rebecca Thurston, PhD, from the University of Pittsburgh, told this news organization.

“What I take from this is, really, that sexual assault has implications for women’s health, far beyond exclusively mental health outcomes, but also for their cardiovascular health, as we have shown in other work and for their stroke and dementia risk as we are seeing in the present work,” Dr. Thurston added.

The study was presented at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., and has been accepted for publication in the journal Brain Imaging and Behavior.

Beyond the usual suspects

As part of the study, 145 women (mean age, 59 years) free of clinical cardiovascular disease, stroke, or dementia provided their medical history, including history of traumatic experiences, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder and underwent magnetic resonance brain imaging for WMHs.

More than two-thirds (68%) of the women reported at least one trauma, most commonly sexual assault (23%).

In multivariate analysis, women with trauma exposure had greater WMH volume than women without trauma (P = .01), with sexual assault most strongly associated with greater WMH volume (P = .02).

The associations persisted after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

“A history of sexual assault was particularly related to white matter hyperintensities in the parietal lobe, and these kinds of white matter hyperintensities have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease in a fairly pronounced way,” Dr. Thurston said.

“When we think about risk factors for stroke, dementia, we need to think beyond exclusively our usual suspects and also think about women [who experienced] psychological trauma and experienced sexual assault in particular. So ask about it and consider it part of your screening regimen,” she added.

‘Burgeoning’ literature

Commenting on the findings, Charles Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, and director of its Institute for Early Life Adversity Research, said the research adds to the “burgeoning literature on the long term neurobiological consequences of trauma and more specifically, sexual abuse, on brain imaging measures.”

“Our group and others reported several years ago that patients with mood disorders, more specifically bipolar disorder and major depression, had higher rates of WMH than matched controls. Those older studies did not control for a history of early life adversity such as childhood maltreatment,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

“In addition to this finding of increased WMH in subjects exposed to trauma is a very large literature documenting other central nervous system (CNS) changes in this population, including cortical thinning in certain brain areas and clearly an emerging finding that different forms of childhood maltreatment are associated with quite distinct structural brain alterations in adulthood,” he noted.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thurston and Dr. Nemeroff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traumatic experiences, especially sexual assault, may put women at greater risk for poor brain health.

In the Ms Brain study, middle-aged women with trauma exposure had a greater volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) than those without trauma. In addition, the differences persisted even after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

WMHs are “an important indicator of small vessel disease in the brain and have been linked to future stroke risk, dementia risk, and mortality,” lead investigator Rebecca Thurston, PhD, from the University of Pittsburgh, told this news organization.

“What I take from this is, really, that sexual assault has implications for women’s health, far beyond exclusively mental health outcomes, but also for their cardiovascular health, as we have shown in other work and for their stroke and dementia risk as we are seeing in the present work,” Dr. Thurston added.

The study was presented at the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., and has been accepted for publication in the journal Brain Imaging and Behavior.

Beyond the usual suspects

As part of the study, 145 women (mean age, 59 years) free of clinical cardiovascular disease, stroke, or dementia provided their medical history, including history of traumatic experiences, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder and underwent magnetic resonance brain imaging for WMHs.

More than two-thirds (68%) of the women reported at least one trauma, most commonly sexual assault (23%).

In multivariate analysis, women with trauma exposure had greater WMH volume than women without trauma (P = .01), with sexual assault most strongly associated with greater WMH volume (P = .02).

The associations persisted after adjusting for depressive or post-traumatic stress symptoms.

“A history of sexual assault was particularly related to white matter hyperintensities in the parietal lobe, and these kinds of white matter hyperintensities have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease in a fairly pronounced way,” Dr. Thurston said.