User login

Choline and prevention of prevalent mental illnesses

Advocating on behalf of the power of prevention in psychiatry has been my life’s work. I ran a world-class community mental health center with a strong wellness component; have taught, researched, written, and spoken extensively about the importance of prevention; and have incorporated preventive ideas into my current clinical practice.

I would like to think that I have been one of the forces that helped start a new movement called “positive psychiatry,” the idea that mental health must encompass more than the reduction or elimination of psychiatric illness. In the new book edited by American Psychiatric Association Past-President Dilip V. Jeste, MD, and Barton W. Palmer, PhD, called “Positive Psychiatry” (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2015), I contributed a chapter on the psychosocial factors tied to positive outcomes. In addition, I am part of a group of psychiatrists and researchers affiliated with the World Psychiatric Association who are starting an interest group focusing on positive psychiatry.

Recently, because of the prevalence of neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE) (the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 version of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders) in my community, I have begun to tout this problem as a major public health issue. When we formulated the Institute of Medicine’s 2009 Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities report, we did not include the problem of fetal alcohol exposure – and this was an unfortunate oversight.

However, this area of interest had not yet fully developed, and nearly 8 years later, there have been some confluent developments regarding potential prevention of this problem. They both involve choline.

First, we know that when women drink while pregnant, the alcohol they consume rids their bodies of choline, a nutrient the fetus needs for proper cell construction, neurogenesis, and neurodevelopment. Accordingly, several scientists are exploring using choline both pre- and postnatally to see if the defects on ND-PAE can be ameliorated or prevented. All of the research in this area is new, but it looks very promising.

Recently, I had the good fortune to present an idea during the Andrea Delgado Memorial Lecture at the Black Psychiatrists of America transcultural conference in the Bahamas. I also spoke at a mini-plenary at the 32nd Annual Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Policy Symposium in Atlanta. The core of the presentations were not too deep (to paraphrase a line Morgan Freeman used on Jack Nicholson in the movie “The Bucket List” – ‘I have seen bathtubs that are deeper’), but I think it explicated an essential idea. Jessie Aujla, a 4th-year medical student, and I explored the content of choline in the 25 top prenatal vitamins and found none of them contained the 450-mg daily recommended dose of choline advised by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. In fact, only two contain 50 mg; six others contain less than 30 mg; and the other 17 have no choline whatsoever (this study is in press at the Journal of Family Medicine and Prevention). So we are advocating that the prenatal vitamin manufacturers increase the choline content of their prenatal vitamins, because although women may be getting some choline from their food diets, we found one large study illustrating that 90% of pregnant women are choline deficient.

The other area of interest regarding choline as a preventive agent for mental illness is work published by researchers at the University of Colorado Denver. This research group is proposing that choline may prevent the development of autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizophrenia by an epigenetic mechanism involving a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. This makes perfectly good sense clinically among those of us who are treating patients with ND-PAE. Some of us are starting to think of ND-PAE as a choline deficiency disorder and see symptoms that are extremely similar to autism, ADHD, and schizophrenia in such patients. Many patients with ND-PAE are misdiagnosed with these disorders. Accordingly, there appears to be some common ground between ideas aimed at preventing fetal alcohol exposure and those aimed at preventing autism, ADHD, and schizophrenia – specifically, ensuring that pregnant women get an adequate supply of choline.

There is certainly a great need to do more research to nail down these two potential preventive actions. But until that research is done, it seems to me that the least we can do is to advocate for a position that the manufacturers of prenatal vitamins at least include the daily recommended dose of choline (450 mg/day) pregnant women need per the findings of the Institute of Medicine’s Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline, published in 1998.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; clinical psychiatrist emeritus, department of psychiatry, at the University of Illinois at Chicago; former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

Advocating on behalf of the power of prevention in psychiatry has been my life’s work. I ran a world-class community mental health center with a strong wellness component; have taught, researched, written, and spoken extensively about the importance of prevention; and have incorporated preventive ideas into my current clinical practice.

I would like to think that I have been one of the forces that helped start a new movement called “positive psychiatry,” the idea that mental health must encompass more than the reduction or elimination of psychiatric illness. In the new book edited by American Psychiatric Association Past-President Dilip V. Jeste, MD, and Barton W. Palmer, PhD, called “Positive Psychiatry” (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2015), I contributed a chapter on the psychosocial factors tied to positive outcomes. In addition, I am part of a group of psychiatrists and researchers affiliated with the World Psychiatric Association who are starting an interest group focusing on positive psychiatry.

Recently, because of the prevalence of neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE) (the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 version of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders) in my community, I have begun to tout this problem as a major public health issue. When we formulated the Institute of Medicine’s 2009 Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities report, we did not include the problem of fetal alcohol exposure – and this was an unfortunate oversight.

However, this area of interest had not yet fully developed, and nearly 8 years later, there have been some confluent developments regarding potential prevention of this problem. They both involve choline.

First, we know that when women drink while pregnant, the alcohol they consume rids their bodies of choline, a nutrient the fetus needs for proper cell construction, neurogenesis, and neurodevelopment. Accordingly, several scientists are exploring using choline both pre- and postnatally to see if the defects on ND-PAE can be ameliorated or prevented. All of the research in this area is new, but it looks very promising.

Recently, I had the good fortune to present an idea during the Andrea Delgado Memorial Lecture at the Black Psychiatrists of America transcultural conference in the Bahamas. I also spoke at a mini-plenary at the 32nd Annual Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Policy Symposium in Atlanta. The core of the presentations were not too deep (to paraphrase a line Morgan Freeman used on Jack Nicholson in the movie “The Bucket List” – ‘I have seen bathtubs that are deeper’), but I think it explicated an essential idea. Jessie Aujla, a 4th-year medical student, and I explored the content of choline in the 25 top prenatal vitamins and found none of them contained the 450-mg daily recommended dose of choline advised by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. In fact, only two contain 50 mg; six others contain less than 30 mg; and the other 17 have no choline whatsoever (this study is in press at the Journal of Family Medicine and Prevention). So we are advocating that the prenatal vitamin manufacturers increase the choline content of their prenatal vitamins, because although women may be getting some choline from their food diets, we found one large study illustrating that 90% of pregnant women are choline deficient.

The other area of interest regarding choline as a preventive agent for mental illness is work published by researchers at the University of Colorado Denver. This research group is proposing that choline may prevent the development of autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizophrenia by an epigenetic mechanism involving a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. This makes perfectly good sense clinically among those of us who are treating patients with ND-PAE. Some of us are starting to think of ND-PAE as a choline deficiency disorder and see symptoms that are extremely similar to autism, ADHD, and schizophrenia in such patients. Many patients with ND-PAE are misdiagnosed with these disorders. Accordingly, there appears to be some common ground between ideas aimed at preventing fetal alcohol exposure and those aimed at preventing autism, ADHD, and schizophrenia – specifically, ensuring that pregnant women get an adequate supply of choline.

There is certainly a great need to do more research to nail down these two potential preventive actions. But until that research is done, it seems to me that the least we can do is to advocate for a position that the manufacturers of prenatal vitamins at least include the daily recommended dose of choline (450 mg/day) pregnant women need per the findings of the Institute of Medicine’s Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline, published in 1998.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; clinical psychiatrist emeritus, department of psychiatry, at the University of Illinois at Chicago; former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

Advocating on behalf of the power of prevention in psychiatry has been my life’s work. I ran a world-class community mental health center with a strong wellness component; have taught, researched, written, and spoken extensively about the importance of prevention; and have incorporated preventive ideas into my current clinical practice.

I would like to think that I have been one of the forces that helped start a new movement called “positive psychiatry,” the idea that mental health must encompass more than the reduction or elimination of psychiatric illness. In the new book edited by American Psychiatric Association Past-President Dilip V. Jeste, MD, and Barton W. Palmer, PhD, called “Positive Psychiatry” (Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2015), I contributed a chapter on the psychosocial factors tied to positive outcomes. In addition, I am part of a group of psychiatrists and researchers affiliated with the World Psychiatric Association who are starting an interest group focusing on positive psychiatry.

Recently, because of the prevalence of neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE) (the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 version of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders) in my community, I have begun to tout this problem as a major public health issue. When we formulated the Institute of Medicine’s 2009 Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities report, we did not include the problem of fetal alcohol exposure – and this was an unfortunate oversight.

However, this area of interest had not yet fully developed, and nearly 8 years later, there have been some confluent developments regarding potential prevention of this problem. They both involve choline.

First, we know that when women drink while pregnant, the alcohol they consume rids their bodies of choline, a nutrient the fetus needs for proper cell construction, neurogenesis, and neurodevelopment. Accordingly, several scientists are exploring using choline both pre- and postnatally to see if the defects on ND-PAE can be ameliorated or prevented. All of the research in this area is new, but it looks very promising.

Recently, I had the good fortune to present an idea during the Andrea Delgado Memorial Lecture at the Black Psychiatrists of America transcultural conference in the Bahamas. I also spoke at a mini-plenary at the 32nd Annual Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Policy Symposium in Atlanta. The core of the presentations were not too deep (to paraphrase a line Morgan Freeman used on Jack Nicholson in the movie “The Bucket List” – ‘I have seen bathtubs that are deeper’), but I think it explicated an essential idea. Jessie Aujla, a 4th-year medical student, and I explored the content of choline in the 25 top prenatal vitamins and found none of them contained the 450-mg daily recommended dose of choline advised by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. In fact, only two contain 50 mg; six others contain less than 30 mg; and the other 17 have no choline whatsoever (this study is in press at the Journal of Family Medicine and Prevention). So we are advocating that the prenatal vitamin manufacturers increase the choline content of their prenatal vitamins, because although women may be getting some choline from their food diets, we found one large study illustrating that 90% of pregnant women are choline deficient.

The other area of interest regarding choline as a preventive agent for mental illness is work published by researchers at the University of Colorado Denver. This research group is proposing that choline may prevent the development of autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizophrenia by an epigenetic mechanism involving a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. This makes perfectly good sense clinically among those of us who are treating patients with ND-PAE. Some of us are starting to think of ND-PAE as a choline deficiency disorder and see symptoms that are extremely similar to autism, ADHD, and schizophrenia in such patients. Many patients with ND-PAE are misdiagnosed with these disorders. Accordingly, there appears to be some common ground between ideas aimed at preventing fetal alcohol exposure and those aimed at preventing autism, ADHD, and schizophrenia – specifically, ensuring that pregnant women get an adequate supply of choline.

There is certainly a great need to do more research to nail down these two potential preventive actions. But until that research is done, it seems to me that the least we can do is to advocate for a position that the manufacturers of prenatal vitamins at least include the daily recommended dose of choline (450 mg/day) pregnant women need per the findings of the Institute of Medicine’s Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline, published in 1998.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; clinical psychiatrist emeritus, department of psychiatry, at the University of Illinois at Chicago; former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

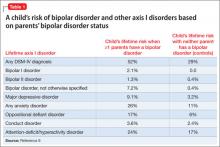

Differentiating ADHD and bipolar disorder

Preschool ADHD diagnoses plateaued after 2011 AAP guideline

The introduction of the 2011 American Academy of Pediatrics practice guidelines on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder was associated with a leveling off in the number of diagnoses in preschool children.

“In the preguideline period, the trajectory of ADHD diagnosis increased slightly but significantly across practices,” Alexander G. Fiks, MD, from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and his coinvestigators wrote. “However, the rate of ADHD diagnosis no longer increased significantly after guideline release.”

They found that the rate of ADHD diagnoses was 0.7% before the release of the 2011 guidelines and 0.9% after, while the rate of stimulant prescriptions remained constant at 0.4% across the entire study period (Pediatrics. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2025).

While the levels of stimulants prescribed remained the same across the period of the analysis, the proportion of children diagnosed with ADHD who were prescribed stimulants had already been in significant decline before the release of the guidelines. After the guidelines, this rate also plateaued, signifying that before – but not after – the guidelines, children were becoming less likely to be prescribed stimulant medication following an ADHD diagnosis.

Commenting on the change in diagnostic and prescribing patterns, the investigators noted that the primary goal of practice guidelines was to standardize care.

“In the case of preschool ADHD, such standardization might have resulted in an increasing trajectory in diagnosis of preschool children if pediatric clinicians had not previously been evaluating ADHD when an evaluation was warranted,” they wrote. “Alternatively, a decrease in diagnosis could have occurred if clinicians were applying more rigorous standards to the diagnosis and therefore excluding certain children who might have previously been diagnosed or no change if a combination of these two patterns was occurring or if there was no change in the standard used.”

They suggested that the observation of a decreasing likelihood of stimulant prescriptions for ADHD before the guidelines may have been driven by the results of the 2006 Preschool ADHD Treatment Study, which showed a lower effect size of stimulant medication in preschool-aged children, compared with school-aged children.

“Alternatively, findings may have resulted from a decrease in the severity of preschool children diagnosed with ADHD as the proportion of all preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD increased,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Dr. Fiks reported receiving a research grant from Pfizer for work on ADHD unrelated to this study. The other investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

It is encouraging for those of us who worked on crafting the revised guidelines to find some evidence about the impact of those recommendations. However, as the investigators point out, although they were able to find out that, in preschool-aged children with ADHD, recommended criteria for the use of stimulant medications, specifically methylphenidate, did not result in an increase in its use in this age group, the frequency of behavioral parent training, the first-line recommended treatment, could not be determined.

In addition, to address the issue that was the focus of this study, examining the implementation of evidence into practice, there needs to be greater standardization of assessment and treatment modalities so that we can better examine the outcomes of changes in treatment. Studies of prevalence and treatments of children with ADHD have indicated wide variations across the country. Clarifying those differences will require the improved ability to examine the various factors responsible for these variations, particularly across the systems of care that go beyond just medication use.

Mark L. Wolraich, MD, is from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2928). He reported having no financial disclosures.

It is encouraging for those of us who worked on crafting the revised guidelines to find some evidence about the impact of those recommendations. However, as the investigators point out, although they were able to find out that, in preschool-aged children with ADHD, recommended criteria for the use of stimulant medications, specifically methylphenidate, did not result in an increase in its use in this age group, the frequency of behavioral parent training, the first-line recommended treatment, could not be determined.

In addition, to address the issue that was the focus of this study, examining the implementation of evidence into practice, there needs to be greater standardization of assessment and treatment modalities so that we can better examine the outcomes of changes in treatment. Studies of prevalence and treatments of children with ADHD have indicated wide variations across the country. Clarifying those differences will require the improved ability to examine the various factors responsible for these variations, particularly across the systems of care that go beyond just medication use.

Mark L. Wolraich, MD, is from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2928). He reported having no financial disclosures.

It is encouraging for those of us who worked on crafting the revised guidelines to find some evidence about the impact of those recommendations. However, as the investigators point out, although they were able to find out that, in preschool-aged children with ADHD, recommended criteria for the use of stimulant medications, specifically methylphenidate, did not result in an increase in its use in this age group, the frequency of behavioral parent training, the first-line recommended treatment, could not be determined.

In addition, to address the issue that was the focus of this study, examining the implementation of evidence into practice, there needs to be greater standardization of assessment and treatment modalities so that we can better examine the outcomes of changes in treatment. Studies of prevalence and treatments of children with ADHD have indicated wide variations across the country. Clarifying those differences will require the improved ability to examine the various factors responsible for these variations, particularly across the systems of care that go beyond just medication use.

Mark L. Wolraich, MD, is from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2928). He reported having no financial disclosures.

The introduction of the 2011 American Academy of Pediatrics practice guidelines on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder was associated with a leveling off in the number of diagnoses in preschool children.

“In the preguideline period, the trajectory of ADHD diagnosis increased slightly but significantly across practices,” Alexander G. Fiks, MD, from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and his coinvestigators wrote. “However, the rate of ADHD diagnosis no longer increased significantly after guideline release.”

They found that the rate of ADHD diagnoses was 0.7% before the release of the 2011 guidelines and 0.9% after, while the rate of stimulant prescriptions remained constant at 0.4% across the entire study period (Pediatrics. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2025).

While the levels of stimulants prescribed remained the same across the period of the analysis, the proportion of children diagnosed with ADHD who were prescribed stimulants had already been in significant decline before the release of the guidelines. After the guidelines, this rate also plateaued, signifying that before – but not after – the guidelines, children were becoming less likely to be prescribed stimulant medication following an ADHD diagnosis.

Commenting on the change in diagnostic and prescribing patterns, the investigators noted that the primary goal of practice guidelines was to standardize care.

“In the case of preschool ADHD, such standardization might have resulted in an increasing trajectory in diagnosis of preschool children if pediatric clinicians had not previously been evaluating ADHD when an evaluation was warranted,” they wrote. “Alternatively, a decrease in diagnosis could have occurred if clinicians were applying more rigorous standards to the diagnosis and therefore excluding certain children who might have previously been diagnosed or no change if a combination of these two patterns was occurring or if there was no change in the standard used.”

They suggested that the observation of a decreasing likelihood of stimulant prescriptions for ADHD before the guidelines may have been driven by the results of the 2006 Preschool ADHD Treatment Study, which showed a lower effect size of stimulant medication in preschool-aged children, compared with school-aged children.

“Alternatively, findings may have resulted from a decrease in the severity of preschool children diagnosed with ADHD as the proportion of all preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD increased,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Dr. Fiks reported receiving a research grant from Pfizer for work on ADHD unrelated to this study. The other investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

The introduction of the 2011 American Academy of Pediatrics practice guidelines on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder was associated with a leveling off in the number of diagnoses in preschool children.

“In the preguideline period, the trajectory of ADHD diagnosis increased slightly but significantly across practices,” Alexander G. Fiks, MD, from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and his coinvestigators wrote. “However, the rate of ADHD diagnosis no longer increased significantly after guideline release.”

They found that the rate of ADHD diagnoses was 0.7% before the release of the 2011 guidelines and 0.9% after, while the rate of stimulant prescriptions remained constant at 0.4% across the entire study period (Pediatrics. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2025).

While the levels of stimulants prescribed remained the same across the period of the analysis, the proportion of children diagnosed with ADHD who were prescribed stimulants had already been in significant decline before the release of the guidelines. After the guidelines, this rate also plateaued, signifying that before – but not after – the guidelines, children were becoming less likely to be prescribed stimulant medication following an ADHD diagnosis.

Commenting on the change in diagnostic and prescribing patterns, the investigators noted that the primary goal of practice guidelines was to standardize care.

“In the case of preschool ADHD, such standardization might have resulted in an increasing trajectory in diagnosis of preschool children if pediatric clinicians had not previously been evaluating ADHD when an evaluation was warranted,” they wrote. “Alternatively, a decrease in diagnosis could have occurred if clinicians were applying more rigorous standards to the diagnosis and therefore excluding certain children who might have previously been diagnosed or no change if a combination of these two patterns was occurring or if there was no change in the standard used.”

They suggested that the observation of a decreasing likelihood of stimulant prescriptions for ADHD before the guidelines may have been driven by the results of the 2006 Preschool ADHD Treatment Study, which showed a lower effect size of stimulant medication in preschool-aged children, compared with school-aged children.

“Alternatively, findings may have resulted from a decrease in the severity of preschool children diagnosed with ADHD as the proportion of all preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD increased,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Dr. Fiks reported receiving a research grant from Pfizer for work on ADHD unrelated to this study. The other investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rate of ADHD diagnoses was 0.7% before the guidelines and 0.9% after, while stimulant prescriptions remained constant at 0.4% across the study period.

Data source: An analysis of electronic health record data from 143,881 children across 63 primary care practice from January 2008 to July 2014.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Dr. Fiks reported receiving a research grant from Pfizer for work on ADHD unrelated to this study. The other investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Special Edition: Focus on ADHD

ADHD symptoms are stable, then a sudden relapse

CASE

Sudden deterioration

R, age 11, has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), combined type, and oppositional defiant disorder, which has been stable for more than a year on extended-release (ER) methylphenidate (brand name: Concerta), 54 mg/d (1.2 mg/kg). With combined pharmacotherapy and behavioral management, his symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity improved at school and at home. He shows some academic gains as evidenced by improved achievement at school.

Over 2 months, R experiences a substantial deterioration in behavioral and academic performance. Along with core symptoms of ADHD, he begins to exhibit physical and verbal aggression. A report from school states that R has been using obscene language and destroying property, and has had episodes of provoked aggression toward his peers. His grades drop and he receives 2 school suspensions because of aggressive behavior.

What could be causing R’s ADHD symptoms to reemerge?

a) nonadherence to treatment

b) substance abuse

c) medication change

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

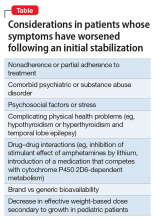

Worsening of psychiatric symptoms in a stable patient is relatively common. Many factors can contribute to patient destabilization. Treatment nonadherence is a leading cause, along with psychosocial stressors and substance use (Table).

EVALUATION

Adherence confirmed

R is hyperactive and distracted during his visit, a clear deterioration from his baseline status. R is oppositional and defiant toward his mother during the session, but shows good social skills when communicating with the physician.

R’s mother reports that her son seldom forgets to take his medication, and she ensures that he is swallowing the pill, rather than chewing it. Data from the prescription drug-monitoring program show that the family is filling the prescriptions regularly. The ER methylphenidate dosage is raised to 72 mg/d. The clinicians provide psychoeducation about adherence to a medication regimen to R and his family. Also, his parents and teachers receive Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for ADHD to assess the symptoms in different settings.

At a follow-up visit a week later, R’s mother reports that her son continues to have problems in school and at home. The Vanderbilt scales reveal that R is having clinically significant problems with attention, hyperactivity, impulse control, and oppositional behavior.

A urine drug screen is ordered to rule out the possibility of a sudden deterioration of ADHD symptoms secondary to substance use disorder. To ensure compliance, we recommend that R take his medication at the school nurse’s office in the morning.

A week later

Although R takes his medication at school, he continues to show core symptoms of ADHD without improvement. The urine drug screen is negative. A physical examination does not reveal any medical illness. The treatment team calls the pharmacist to obtain a complete list of medications R is taking, who confirms that he is only receiving ER methylphenidate, 72 mg/d. The pharmacist also notes that R’s medication was switched from the brand-name drug to a generic 3 months ago because of a change in insurance coverage. This change coincided with the reemergence of his ADHD symptoms.

R’s mother reports that the new pills do not look like the old ones even before the dosage was raised. A new brand-necessary prescription is sent to the pharmacy. With the brand-name medication, R’s symptoms quickly improve, and remain improved when the dosage is decreased to the previous dosage of 54 mg/d.

With osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) and outer coating of ER methylphenidate, how much drug is released immediately vs slow release?

a) 22% immediate release and 78% slow release

b) 78% immediate release and 22% slow release

c) 50% immediate release and 50% slow release

The authors’ observations

Generic substitution of a brand medication can result in worsening of symptoms and increased adverse effects. Possible bioequivalence issues can lead to failure of drug therapy.1

In 2013, the FDA determined that 2 specific generic formulations of ER methylphenidate do not have therapeutic equivalency to the brand-name medication, Concerta. The FDA stated, “Based on an analysis of data, FDA has concerns about whether or not two approved generic versions of Concerta tablets (methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release tablets), used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults and children, are therapeutically equiv

In an apparent confirmation of the FDA’s concerns, a case series of children and adolescents with ADHD observed that almost all of the patients showed symptom improvement when they switched from a non-OROS formulation to an OROS preparation at the same dosage.3

The OROS preparation is thought to provide more predictable medication delivery over an extended period of time (Figure). A patient taking an ER formulation without OROS might lose this benefit, which could lead to symptom destabilization, even if the patient is taking the medication as instructed.

Brand vs generic

Under FDA regulations, companies seeking approval for generic formulations of approved drugs must demonstrate that their products are the same as the brand-name drug in terms of:

- active ingredients

- strength

- dosage form

- route of administration

- packaging label.

In addition, the pharmaceutical company must demonstrate that the generic form is absorbed and distributed to the part of the body at which it has its effect at acceptably similar levels to the brand-name drug. All medications—new or generic, in clinical trials or approved, prescription or over-the-counter—must be manufactured under controlled conditions that assure product quality.

However, some studies have disputed this equivalency. In 1 study, patients with schizophrenia receiving generic olanzapine had lower serum concentration than patients with schizophrenia taking equivalent dosages of brand-name olanzapine.4 Similarly, studies comparing generic and brand-name venlafaxine showed significant differences in peak plasma concentration (Cmax)between generic and brand-name compounds.5

The FDA has considered upgrading the manufacturers’ warnings about the risk of generic medications, but has delayed the decision to 2017.6

FDA’s approval process for generic drugs

To receive approval of a generic formulation in the United States, the FDA requires that the generic drug should be compared with the corresponding brand-name drug in small crossover trials involving at least 24 to 36 healthy volunteers.

Bioequivalence is then established based on assessments of the rate of absorption (Cmax and area under the plasma concentration-time curve [AUC]). The FDA’s criteria are designed to achieve 90% confidence that the ratios of the test-to-reference log-transformed mean values for AUC and Cmax are within the interval of 80% to 125%. The FDA accepts −20% to 25% variation in Cmax and AUC in products that are considered bioequivalent. This is much less stringent than its −5% to 5% standard used for brand-name products. The FDA publishes a list of generic drugs that have been certified as bioequivalent, known as the “Orange Book.”5

Considerations when substituting generic medication

Because of the growing number of generic formulations of the same medication, generic–generic switches are becoming more commonplace. Theoretically, any 2 generic versions of the same medication can have a variation of up to 40% in AUC and Cmax. Generic medications are tested in healthy human controls through single-dose studies, which raises concerns about their applicability to the entire patient population.

Bioequivalence. It is a matter of debate whether bioequivalence translates to therapeutic equivalency. For medications with a narrow therapeutic index, the FDA has accepted that these 2 phenomena are not necessarily linked. With the exception of a few medications, including lithium and some anticonvulsants such as divalproex sodium and carbamazepine, serum level of the medications usually does not predict clinical response.

Inert ingredients. Generic medications can include inert ingredients (excipients) that are different from those in their branded counterparts. Some of these inactive ingredients can cause adverse effects. A study comparing paroxetine mesylate and paroxetine hydrochloride showed differences in bioequivalence and clinical efficacy.7

In some cases, brand-to-generic substitution can thwart clinical progress in a stable patient. This small change in the medication could destabilize the patient’s condition, which, in turn, may lead to unnecessary and significant social and financial burdens on the patient’s family, school, community, and the health care system.

Recommendations

In the event of a change in clinical response, clinicians first should evaluate adherence and explore other factors, such as biological, psychological, medical, and social issues. Adherence can be adversely affected by a change in the physical characteristics of the pill. Prescribers should remain cognizant of brand–generic and generic–generic switches. It may be reasonable to adjust the dosage of the new generic medication to address changes in clinical effectiveness.

If these strategies are ineffective, consider switching to a brand-name medication. Write “Dispense As Written” on the prescription to ensure delivery of the branded medication or a specific generic version of the medication.

An insurance company might require prior authorization to approve payment for the brand medication. To save time, use electronic forms or fax for communicating with the insurance company. Adding references to FDA statements and research papers, along with the patient’s history and presentations, would be prudent to demonstrate doubts about efficacy of the generic medication.

1. Atif M, Azeem M, Sarwar MR. Potential problems and recommendations regarding substitution of generic antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review of literature. Springerplus. 2016;5:182. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1824-2.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Methylphenidate hydrochloride extended release tablets (generic Concerta) made by Mallinckrodt and Kudco. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm422568.htm. Updated November 13, 2014. Accessed August 29, 2016.

3. Lally MD, Kral MC, Boan AD. Not all generic Concerta is created equal: comparison of OROS versus non-OROS for the treatment of ADHD [published online October 14, 2015]. Clin Pediatr (Phila). doi:10.1177/0009922815611647.

4. Italiano DD, Bruno A, Santoro V, et al. Generic olanzapine substitution in patients with schizophrenia: assessment of serum concentrations and therapeutic response after switching. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(6):827-830.

5. Borgheini GG. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25(6):1578-1592.

6. Thomas K. F.D.A. delays rule on generic drug labels. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/20/business/fda-delays-rule-on-generic-drug-labels.html. Published May 19, 2016. Accessed August 29, 2016.

7. Pae CU, Misra A, Ham BJ, et al. Paroxetine mesylate: comparable to paroxetine hydrochloride? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(2):185-193

CASE

Sudden deterioration

R, age 11, has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), combined type, and oppositional defiant disorder, which has been stable for more than a year on extended-release (ER) methylphenidate (brand name: Concerta), 54 mg/d (1.2 mg/kg). With combined pharmacotherapy and behavioral management, his symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity improved at school and at home. He shows some academic gains as evidenced by improved achievement at school.

Over 2 months, R experiences a substantial deterioration in behavioral and academic performance. Along with core symptoms of ADHD, he begins to exhibit physical and verbal aggression. A report from school states that R has been using obscene language and destroying property, and has had episodes of provoked aggression toward his peers. His grades drop and he receives 2 school suspensions because of aggressive behavior.

What could be causing R’s ADHD symptoms to reemerge?

a) nonadherence to treatment

b) substance abuse

c) medication change

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Worsening of psychiatric symptoms in a stable patient is relatively common. Many factors can contribute to patient destabilization. Treatment nonadherence is a leading cause, along with psychosocial stressors and substance use (Table).

EVALUATION

Adherence confirmed

R is hyperactive and distracted during his visit, a clear deterioration from his baseline status. R is oppositional and defiant toward his mother during the session, but shows good social skills when communicating with the physician.

R’s mother reports that her son seldom forgets to take his medication, and she ensures that he is swallowing the pill, rather than chewing it. Data from the prescription drug-monitoring program show that the family is filling the prescriptions regularly. The ER methylphenidate dosage is raised to 72 mg/d. The clinicians provide psychoeducation about adherence to a medication regimen to R and his family. Also, his parents and teachers receive Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for ADHD to assess the symptoms in different settings.

At a follow-up visit a week later, R’s mother reports that her son continues to have problems in school and at home. The Vanderbilt scales reveal that R is having clinically significant problems with attention, hyperactivity, impulse control, and oppositional behavior.

A urine drug screen is ordered to rule out the possibility of a sudden deterioration of ADHD symptoms secondary to substance use disorder. To ensure compliance, we recommend that R take his medication at the school nurse’s office in the morning.

A week later

Although R takes his medication at school, he continues to show core symptoms of ADHD without improvement. The urine drug screen is negative. A physical examination does not reveal any medical illness. The treatment team calls the pharmacist to obtain a complete list of medications R is taking, who confirms that he is only receiving ER methylphenidate, 72 mg/d. The pharmacist also notes that R’s medication was switched from the brand-name drug to a generic 3 months ago because of a change in insurance coverage. This change coincided with the reemergence of his ADHD symptoms.

R’s mother reports that the new pills do not look like the old ones even before the dosage was raised. A new brand-necessary prescription is sent to the pharmacy. With the brand-name medication, R’s symptoms quickly improve, and remain improved when the dosage is decreased to the previous dosage of 54 mg/d.

With osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) and outer coating of ER methylphenidate, how much drug is released immediately vs slow release?

a) 22% immediate release and 78% slow release

b) 78% immediate release and 22% slow release

c) 50% immediate release and 50% slow release

The authors’ observations

Generic substitution of a brand medication can result in worsening of symptoms and increased adverse effects. Possible bioequivalence issues can lead to failure of drug therapy.1

In 2013, the FDA determined that 2 specific generic formulations of ER methylphenidate do not have therapeutic equivalency to the brand-name medication, Concerta. The FDA stated, “Based on an analysis of data, FDA has concerns about whether or not two approved generic versions of Concerta tablets (methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release tablets), used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults and children, are therapeutically equiv

In an apparent confirmation of the FDA’s concerns, a case series of children and adolescents with ADHD observed that almost all of the patients showed symptom improvement when they switched from a non-OROS formulation to an OROS preparation at the same dosage.3

The OROS preparation is thought to provide more predictable medication delivery over an extended period of time (Figure). A patient taking an ER formulation without OROS might lose this benefit, which could lead to symptom destabilization, even if the patient is taking the medication as instructed.

Brand vs generic

Under FDA regulations, companies seeking approval for generic formulations of approved drugs must demonstrate that their products are the same as the brand-name drug in terms of:

- active ingredients

- strength

- dosage form

- route of administration

- packaging label.

In addition, the pharmaceutical company must demonstrate that the generic form is absorbed and distributed to the part of the body at which it has its effect at acceptably similar levels to the brand-name drug. All medications—new or generic, in clinical trials or approved, prescription or over-the-counter—must be manufactured under controlled conditions that assure product quality.

However, some studies have disputed this equivalency. In 1 study, patients with schizophrenia receiving generic olanzapine had lower serum concentration than patients with schizophrenia taking equivalent dosages of brand-name olanzapine.4 Similarly, studies comparing generic and brand-name venlafaxine showed significant differences in peak plasma concentration (Cmax)between generic and brand-name compounds.5

The FDA has considered upgrading the manufacturers’ warnings about the risk of generic medications, but has delayed the decision to 2017.6

FDA’s approval process for generic drugs

To receive approval of a generic formulation in the United States, the FDA requires that the generic drug should be compared with the corresponding brand-name drug in small crossover trials involving at least 24 to 36 healthy volunteers.

Bioequivalence is then established based on assessments of the rate of absorption (Cmax and area under the plasma concentration-time curve [AUC]). The FDA’s criteria are designed to achieve 90% confidence that the ratios of the test-to-reference log-transformed mean values for AUC and Cmax are within the interval of 80% to 125%. The FDA accepts −20% to 25% variation in Cmax and AUC in products that are considered bioequivalent. This is much less stringent than its −5% to 5% standard used for brand-name products. The FDA publishes a list of generic drugs that have been certified as bioequivalent, known as the “Orange Book.”5

Considerations when substituting generic medication

Because of the growing number of generic formulations of the same medication, generic–generic switches are becoming more commonplace. Theoretically, any 2 generic versions of the same medication can have a variation of up to 40% in AUC and Cmax. Generic medications are tested in healthy human controls through single-dose studies, which raises concerns about their applicability to the entire patient population.

Bioequivalence. It is a matter of debate whether bioequivalence translates to therapeutic equivalency. For medications with a narrow therapeutic index, the FDA has accepted that these 2 phenomena are not necessarily linked. With the exception of a few medications, including lithium and some anticonvulsants such as divalproex sodium and carbamazepine, serum level of the medications usually does not predict clinical response.

Inert ingredients. Generic medications can include inert ingredients (excipients) that are different from those in their branded counterparts. Some of these inactive ingredients can cause adverse effects. A study comparing paroxetine mesylate and paroxetine hydrochloride showed differences in bioequivalence and clinical efficacy.7

In some cases, brand-to-generic substitution can thwart clinical progress in a stable patient. This small change in the medication could destabilize the patient’s condition, which, in turn, may lead to unnecessary and significant social and financial burdens on the patient’s family, school, community, and the health care system.

Recommendations

In the event of a change in clinical response, clinicians first should evaluate adherence and explore other factors, such as biological, psychological, medical, and social issues. Adherence can be adversely affected by a change in the physical characteristics of the pill. Prescribers should remain cognizant of brand–generic and generic–generic switches. It may be reasonable to adjust the dosage of the new generic medication to address changes in clinical effectiveness.

If these strategies are ineffective, consider switching to a brand-name medication. Write “Dispense As Written” on the prescription to ensure delivery of the branded medication or a specific generic version of the medication.

An insurance company might require prior authorization to approve payment for the brand medication. To save time, use electronic forms or fax for communicating with the insurance company. Adding references to FDA statements and research papers, along with the patient’s history and presentations, would be prudent to demonstrate doubts about efficacy of the generic medication.

CASE

Sudden deterioration

R, age 11, has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), combined type, and oppositional defiant disorder, which has been stable for more than a year on extended-release (ER) methylphenidate (brand name: Concerta), 54 mg/d (1.2 mg/kg). With combined pharmacotherapy and behavioral management, his symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity improved at school and at home. He shows some academic gains as evidenced by improved achievement at school.

Over 2 months, R experiences a substantial deterioration in behavioral and academic performance. Along with core symptoms of ADHD, he begins to exhibit physical and verbal aggression. A report from school states that R has been using obscene language and destroying property, and has had episodes of provoked aggression toward his peers. His grades drop and he receives 2 school suspensions because of aggressive behavior.

What could be causing R’s ADHD symptoms to reemerge?

a) nonadherence to treatment

b) substance abuse

c) medication change

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Worsening of psychiatric symptoms in a stable patient is relatively common. Many factors can contribute to patient destabilization. Treatment nonadherence is a leading cause, along with psychosocial stressors and substance use (Table).

EVALUATION

Adherence confirmed

R is hyperactive and distracted during his visit, a clear deterioration from his baseline status. R is oppositional and defiant toward his mother during the session, but shows good social skills when communicating with the physician.

R’s mother reports that her son seldom forgets to take his medication, and she ensures that he is swallowing the pill, rather than chewing it. Data from the prescription drug-monitoring program show that the family is filling the prescriptions regularly. The ER methylphenidate dosage is raised to 72 mg/d. The clinicians provide psychoeducation about adherence to a medication regimen to R and his family. Also, his parents and teachers receive Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for ADHD to assess the symptoms in different settings.

At a follow-up visit a week later, R’s mother reports that her son continues to have problems in school and at home. The Vanderbilt scales reveal that R is having clinically significant problems with attention, hyperactivity, impulse control, and oppositional behavior.

A urine drug screen is ordered to rule out the possibility of a sudden deterioration of ADHD symptoms secondary to substance use disorder. To ensure compliance, we recommend that R take his medication at the school nurse’s office in the morning.

A week later

Although R takes his medication at school, he continues to show core symptoms of ADHD without improvement. The urine drug screen is negative. A physical examination does not reveal any medical illness. The treatment team calls the pharmacist to obtain a complete list of medications R is taking, who confirms that he is only receiving ER methylphenidate, 72 mg/d. The pharmacist also notes that R’s medication was switched from the brand-name drug to a generic 3 months ago because of a change in insurance coverage. This change coincided with the reemergence of his ADHD symptoms.

R’s mother reports that the new pills do not look like the old ones even before the dosage was raised. A new brand-necessary prescription is sent to the pharmacy. With the brand-name medication, R’s symptoms quickly improve, and remain improved when the dosage is decreased to the previous dosage of 54 mg/d.

With osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) and outer coating of ER methylphenidate, how much drug is released immediately vs slow release?

a) 22% immediate release and 78% slow release

b) 78% immediate release and 22% slow release

c) 50% immediate release and 50% slow release

The authors’ observations

Generic substitution of a brand medication can result in worsening of symptoms and increased adverse effects. Possible bioequivalence issues can lead to failure of drug therapy.1

In 2013, the FDA determined that 2 specific generic formulations of ER methylphenidate do not have therapeutic equivalency to the brand-name medication, Concerta. The FDA stated, “Based on an analysis of data, FDA has concerns about whether or not two approved generic versions of Concerta tablets (methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release tablets), used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults and children, are therapeutically equiv

In an apparent confirmation of the FDA’s concerns, a case series of children and adolescents with ADHD observed that almost all of the patients showed symptom improvement when they switched from a non-OROS formulation to an OROS preparation at the same dosage.3

The OROS preparation is thought to provide more predictable medication delivery over an extended period of time (Figure). A patient taking an ER formulation without OROS might lose this benefit, which could lead to symptom destabilization, even if the patient is taking the medication as instructed.

Brand vs generic

Under FDA regulations, companies seeking approval for generic formulations of approved drugs must demonstrate that their products are the same as the brand-name drug in terms of:

- active ingredients

- strength

- dosage form

- route of administration

- packaging label.

In addition, the pharmaceutical company must demonstrate that the generic form is absorbed and distributed to the part of the body at which it has its effect at acceptably similar levels to the brand-name drug. All medications—new or generic, in clinical trials or approved, prescription or over-the-counter—must be manufactured under controlled conditions that assure product quality.

However, some studies have disputed this equivalency. In 1 study, patients with schizophrenia receiving generic olanzapine had lower serum concentration than patients with schizophrenia taking equivalent dosages of brand-name olanzapine.4 Similarly, studies comparing generic and brand-name venlafaxine showed significant differences in peak plasma concentration (Cmax)between generic and brand-name compounds.5

The FDA has considered upgrading the manufacturers’ warnings about the risk of generic medications, but has delayed the decision to 2017.6

FDA’s approval process for generic drugs

To receive approval of a generic formulation in the United States, the FDA requires that the generic drug should be compared with the corresponding brand-name drug in small crossover trials involving at least 24 to 36 healthy volunteers.

Bioequivalence is then established based on assessments of the rate of absorption (Cmax and area under the plasma concentration-time curve [AUC]). The FDA’s criteria are designed to achieve 90% confidence that the ratios of the test-to-reference log-transformed mean values for AUC and Cmax are within the interval of 80% to 125%. The FDA accepts −20% to 25% variation in Cmax and AUC in products that are considered bioequivalent. This is much less stringent than its −5% to 5% standard used for brand-name products. The FDA publishes a list of generic drugs that have been certified as bioequivalent, known as the “Orange Book.”5

Considerations when substituting generic medication

Because of the growing number of generic formulations of the same medication, generic–generic switches are becoming more commonplace. Theoretically, any 2 generic versions of the same medication can have a variation of up to 40% in AUC and Cmax. Generic medications are tested in healthy human controls through single-dose studies, which raises concerns about their applicability to the entire patient population.

Bioequivalence. It is a matter of debate whether bioequivalence translates to therapeutic equivalency. For medications with a narrow therapeutic index, the FDA has accepted that these 2 phenomena are not necessarily linked. With the exception of a few medications, including lithium and some anticonvulsants such as divalproex sodium and carbamazepine, serum level of the medications usually does not predict clinical response.

Inert ingredients. Generic medications can include inert ingredients (excipients) that are different from those in their branded counterparts. Some of these inactive ingredients can cause adverse effects. A study comparing paroxetine mesylate and paroxetine hydrochloride showed differences in bioequivalence and clinical efficacy.7

In some cases, brand-to-generic substitution can thwart clinical progress in a stable patient. This small change in the medication could destabilize the patient’s condition, which, in turn, may lead to unnecessary and significant social and financial burdens on the patient’s family, school, community, and the health care system.

Recommendations

In the event of a change in clinical response, clinicians first should evaluate adherence and explore other factors, such as biological, psychological, medical, and social issues. Adherence can be adversely affected by a change in the physical characteristics of the pill. Prescribers should remain cognizant of brand–generic and generic–generic switches. It may be reasonable to adjust the dosage of the new generic medication to address changes in clinical effectiveness.

If these strategies are ineffective, consider switching to a brand-name medication. Write “Dispense As Written” on the prescription to ensure delivery of the branded medication or a specific generic version of the medication.

An insurance company might require prior authorization to approve payment for the brand medication. To save time, use electronic forms or fax for communicating with the insurance company. Adding references to FDA statements and research papers, along with the patient’s history and presentations, would be prudent to demonstrate doubts about efficacy of the generic medication.

1. Atif M, Azeem M, Sarwar MR. Potential problems and recommendations regarding substitution of generic antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review of literature. Springerplus. 2016;5:182. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1824-2.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Methylphenidate hydrochloride extended release tablets (generic Concerta) made by Mallinckrodt and Kudco. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm422568.htm. Updated November 13, 2014. Accessed August 29, 2016.

3. Lally MD, Kral MC, Boan AD. Not all generic Concerta is created equal: comparison of OROS versus non-OROS for the treatment of ADHD [published online October 14, 2015]. Clin Pediatr (Phila). doi:10.1177/0009922815611647.

4. Italiano DD, Bruno A, Santoro V, et al. Generic olanzapine substitution in patients with schizophrenia: assessment of serum concentrations and therapeutic response after switching. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(6):827-830.

5. Borgheini GG. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25(6):1578-1592.

6. Thomas K. F.D.A. delays rule on generic drug labels. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/20/business/fda-delays-rule-on-generic-drug-labels.html. Published May 19, 2016. Accessed August 29, 2016.

7. Pae CU, Misra A, Ham BJ, et al. Paroxetine mesylate: comparable to paroxetine hydrochloride? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(2):185-193

1. Atif M, Azeem M, Sarwar MR. Potential problems and recommendations regarding substitution of generic antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review of literature. Springerplus. 2016;5:182. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1824-2.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Methylphenidate hydrochloride extended release tablets (generic Concerta) made by Mallinckrodt and Kudco. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm422568.htm. Updated November 13, 2014. Accessed August 29, 2016.

3. Lally MD, Kral MC, Boan AD. Not all generic Concerta is created equal: comparison of OROS versus non-OROS for the treatment of ADHD [published online October 14, 2015]. Clin Pediatr (Phila). doi:10.1177/0009922815611647.

4. Italiano DD, Bruno A, Santoro V, et al. Generic olanzapine substitution in patients with schizophrenia: assessment of serum concentrations and therapeutic response after switching. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(6):827-830.

5. Borgheini GG. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25(6):1578-1592.

6. Thomas K. F.D.A. delays rule on generic drug labels. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/20/business/fda-delays-rule-on-generic-drug-labels.html. Published May 19, 2016. Accessed August 29, 2016.

7. Pae CU, Misra A, Ham BJ, et al. Paroxetine mesylate: comparable to paroxetine hydrochloride? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(2):185-193

Hunting for ‘Woozles’ in the Hundred Acre Wood of ADHD

One fine winter’s day when Piglet was brushing away the snow

in front of his house he happened to look up, and there was

Winnie-the-Pooh. Pooh was walking round and round in a circle,

thinking of something else…

So begins the 1926 Winnie-the-Pooh story.1 In this chapter, the well-meaning yellow bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, has found strange tracks in the snow, which he believes belong to a “Woozle.” Pooh follows the tracks, not realizing that he’s walking in a circle. As such, he begins to notice that the tracks have multiplied, which he interprets as evidence of several Woozles.

This “Woozle Effect” has been well described in research settings and is believed to have resulted in conclusions that are not supported by or are inconsistent with the original data, which are then propagated through successive citations, resulting in a scientific “urban legend.”2

Throughout my training from medical school, through fellowship, and during my tenure as a faculty member, I have found myself, at times, searching for Woozles and often have joined my colleagues on these hunts. Herein, I would like to share with you 3 Woozles that have resulted in current false dogmas related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and stimulant psychopharmacology.

Stimulants worsen anxiety

FDA-required labeling for stimulants includes strong language noting that these drugs are “contraindicated in marked anxiety, tension, and agitation, since the drug may aggravate these symptoms.”3 However, data from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses consistently have failed to demonstrate this effect. Moreover, sequenced treatment trials involving adolescents with anxiety disorders and co-occurring ADHD suggest that stimulants actually could reduce anxiety symptoms.

A recent meta-analysis4 that evaluated nearly 2 dozen studies involving approximately 3,000 pediatric patients with ADHD reported that stimulant treatment was associated with a decreased relative risk of anxiety (relative risk: 0.86). The study also observed a dose-response relationship between stimulant dosage and anxiety (Figure, page 6).4 Although the authors note that it is possible that some individuals might experience increased anxiety with stimulants, many patients could show improvement in anxiety symptoms when treated with stimulants, and the authors also advise us, as clinicians, to “consider re-challenging children with ADHD who report … anxiety with psychostimulants, as these symptoms are much more likely to be coincidental rather than caused by psychostimulants.”4

More evidence of a lack of stimulant-induced anxiety comes from a large randomized controlled trial of pediatric patients (age 6 to 17) who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD and a co-occurring anxiety disorder who were treated with methylphenidate (open-label) and then randomized to fluvoxamine or placebo for treatment of anxiety symptoms.5 However, in this trial >80% of the 32 medication-naïve youth improved after stimulant treatment to the point that they no longer had anxiety symptoms severe enough to be eligible for randomization to adjunctive fluvoxamine or placebo.

Stimulants are contraindicated in patients with tic disorders

The package inserts for most stimulant medications warn clinicians that stimulants are “contraindicated in patients with motor tics or with a family history or diagnosis of Tourette’s syndrome.” This is particularly concerning, especially because of the medicolegal implications of the term “contraindicated” and given that as many as 1 in 5 pediatric patients with ADHD have a tic disorder.6 Therefore, labels that list motor tics as a contraindication to stimulant use potentially eliminate the choice of stimulant pharmacotherapy—the most effective treatment for ADHD—for a large number of patients.

When hunting for the Woozle that linked stimulants and tics and led to this language in the package insert, it is worthwhile to review a recent meta-analysis of 22 studies (involving nearly 2,400 youths with ADHD) that suggested new-onset tics or worsening of tics to be present in 5.7% of patients receiving stimulants and in 6.5% of patients receiving placebo. In addition, in this meta-analysis the class of stimulant, dosage, treatment duration, or patient age did not seem to be associated with onset or worsening of tics.7

Polypharmacy represents a therapeutic failure and is not evidence-based

Although treatment guidelines generally have discouraged combination therapy for treating ADHD, there are—on the basis of efficacy—insufficient data to support this prohibition. Moreover, over the last decade, several studies have suggested benefits for combining ADHD medications that have complimentary mechanisms. In this regard, 2 extended-release formulations of α2 agonists have received FDA approval for as adjunctive treatments in pediatric patients with ADHD (extended-release guanfacine and extended-release clonidine). However, despite these FDA indications as adjunctive treatments, many clinicians remain concerned about combination therapy.

Several months ago, a large, 8-week, National Institutes of Health–sponsored trial shed more light on the use of α2agonist + stimulant combinations. Patients age 7 to 17 (N = 179) were randomized to (1) guanfacine + d-methylphenidate, (2) guanfacine monotherapy, or (3) d-methylphenidate monotherapy.8 In addition to clinical outcomes, the authors evaluated the effects of the medication on background cortical activity. Of interest, monotherapies differed between one another and the combination treatment in their effects on cortical activity. Guanfacine decreased alpha band power and methylphenidate administration was associated with an increase in frontal/central beta power, while combination treatment dampened theta band power and was associated with specific, focal increases in beta power.8 These results, although preliminary, suggest not only that medication results in changes in cortical activity that correlate with symptomatic improvement, but that combination treatment may be associated with a distinct cortical activity pattern that is more than the summation of the effects of the monotherapies. Moreover, these data raise the possibility that this synergistic effect on cortical activity may subtend—or at least—relate to the synergistic clinical effects of the 2 medications.

‘Think it over, think it under’

Having discussed several important Woozles that have inhabited the Hundred Acre Wood of ADHD for decades, it is important to remember there are countless Woozles in the larger “Thousand Acre Wood” of psychiatry and medicine. As we evaluate evidence for our interventions, whether psychopharmacologic or psychotherapeutic, we will do w

1. Milne AA. Winnie-the-Pooh. London, United Kingdom: Methuen & Co. Ltd.; 1926.

2. Strauss MA. Processes Explaining the concealment and distortion of evidence on gender symmetry in partner violence. Eur J Crim Pol Res. 1980;74:227-232.

3. Ritalin LA [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; 2015.

4. Coughlin CG, Cohen SC, Mulqueen JM, et al. Meta-analysis: reduced risk of anxiety with psychostimulant treatment in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(8):611-617.

5. Abikoff H, McGough J, Vitiello B, et al; RUPP ADHD/Anxiety Study Group. Sequential pharmacotherapy for children with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity and anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(5):418-427.

6. Bloch MH, Panza KE, Landeros-Weisenberger A, et al. Meta-analysis: treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbid tic disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):884-893.

7. Cohen SC, Mulqueen JM, Ferracioli-Oda E, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of tics associated with psychostimulant use in randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(9):728-736.

8. Loo SK, Bilder RM, Cho AL, et al. Effects of d-methylphenidate, guanfacine, and their combination on electroencephalogram resting state spectral power in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(8):674-682.e1.

One fine winter’s day when Piglet was brushing away the snow

in front of his house he happened to look up, and there was

Winnie-the-Pooh. Pooh was walking round and round in a circle,

thinking of something else…

So begins the 1926 Winnie-the-Pooh story.1 In this chapter, the well-meaning yellow bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, has found strange tracks in the snow, which he believes belong to a “Woozle.” Pooh follows the tracks, not realizing that he’s walking in a circle. As such, he begins to notice that the tracks have multiplied, which he interprets as evidence of several Woozles.

This “Woozle Effect” has been well described in research settings and is believed to have resulted in conclusions that are not supported by or are inconsistent with the original data, which are then propagated through successive citations, resulting in a scientific “urban legend.”2

Throughout my training from medical school, through fellowship, and during my tenure as a faculty member, I have found myself, at times, searching for Woozles and often have joined my colleagues on these hunts. Herein, I would like to share with you 3 Woozles that have resulted in current false dogmas related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and stimulant psychopharmacology.

Stimulants worsen anxiety

FDA-required labeling for stimulants includes strong language noting that these drugs are “contraindicated in marked anxiety, tension, and agitation, since the drug may aggravate these symptoms.”3 However, data from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses consistently have failed to demonstrate this effect. Moreover, sequenced treatment trials involving adolescents with anxiety disorders and co-occurring ADHD suggest that stimulants actually could reduce anxiety symptoms.

A recent meta-analysis4 that evaluated nearly 2 dozen studies involving approximately 3,000 pediatric patients with ADHD reported that stimulant treatment was associated with a decreased relative risk of anxiety (relative risk: 0.86). The study also observed a dose-response relationship between stimulant dosage and anxiety (Figure, page 6).4 Although the authors note that it is possible that some individuals might experience increased anxiety with stimulants, many patients could show improvement in anxiety symptoms when treated with stimulants, and the authors also advise us, as clinicians, to “consider re-challenging children with ADHD who report … anxiety with psychostimulants, as these symptoms are much more likely to be coincidental rather than caused by psychostimulants.”4

More evidence of a lack of stimulant-induced anxiety comes from a large randomized controlled trial of pediatric patients (age 6 to 17) who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD and a co-occurring anxiety disorder who were treated with methylphenidate (open-label) and then randomized to fluvoxamine or placebo for treatment of anxiety symptoms.5 However, in this trial >80% of the 32 medication-naïve youth improved after stimulant treatment to the point that they no longer had anxiety symptoms severe enough to be eligible for randomization to adjunctive fluvoxamine or placebo.

Stimulants are contraindicated in patients with tic disorders

The package inserts for most stimulant medications warn clinicians that stimulants are “contraindicated in patients with motor tics or with a family history or diagnosis of Tourette’s syndrome.” This is particularly concerning, especially because of the medicolegal implications of the term “contraindicated” and given that as many as 1 in 5 pediatric patients with ADHD have a tic disorder.6 Therefore, labels that list motor tics as a contraindication to stimulant use potentially eliminate the choice of stimulant pharmacotherapy—the most effective treatment for ADHD—for a large number of patients.

When hunting for the Woozle that linked stimulants and tics and led to this language in the package insert, it is worthwhile to review a recent meta-analysis of 22 studies (involving nearly 2,400 youths with ADHD) that suggested new-onset tics or worsening of tics to be present in 5.7% of patients receiving stimulants and in 6.5% of patients receiving placebo. In addition, in this meta-analysis the class of stimulant, dosage, treatment duration, or patient age did not seem to be associated with onset or worsening of tics.7

Polypharmacy represents a therapeutic failure and is not evidence-based

Although treatment guidelines generally have discouraged combination therapy for treating ADHD, there are—on the basis of efficacy—insufficient data to support this prohibition. Moreover, over the last decade, several studies have suggested benefits for combining ADHD medications that have complimentary mechanisms. In this regard, 2 extended-release formulations of α2 agonists have received FDA approval for as adjunctive treatments in pediatric patients with ADHD (extended-release guanfacine and extended-release clonidine). However, despite these FDA indications as adjunctive treatments, many clinicians remain concerned about combination therapy.

Several months ago, a large, 8-week, National Institutes of Health–sponsored trial shed more light on the use of α2agonist + stimulant combinations. Patients age 7 to 17 (N = 179) were randomized to (1) guanfacine + d-methylphenidate, (2) guanfacine monotherapy, or (3) d-methylphenidate monotherapy.8 In addition to clinical outcomes, the authors evaluated the effects of the medication on background cortical activity. Of interest, monotherapies differed between one another and the combination treatment in their effects on cortical activity. Guanfacine decreased alpha band power and methylphenidate administration was associated with an increase in frontal/central beta power, while combination treatment dampened theta band power and was associated with specific, focal increases in beta power.8 These results, although preliminary, suggest not only that medication results in changes in cortical activity that correlate with symptomatic improvement, but that combination treatment may be associated with a distinct cortical activity pattern that is more than the summation of the effects of the monotherapies. Moreover, these data raise the possibility that this synergistic effect on cortical activity may subtend—or at least—relate to the synergistic clinical effects of the 2 medications.

‘Think it over, think it under’

Having discussed several important Woozles that have inhabited the Hundred Acre Wood of ADHD for decades, it is important to remember there are countless Woozles in the larger “Thousand Acre Wood” of psychiatry and medicine. As we evaluate evidence for our interventions, whether psychopharmacologic or psychotherapeutic, we will do w

One fine winter’s day when Piglet was brushing away the snow

in front of his house he happened to look up, and there was

Winnie-the-Pooh. Pooh was walking round and round in a circle,

thinking of something else…

So begins the 1926 Winnie-the-Pooh story.1 In this chapter, the well-meaning yellow bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, has found strange tracks in the snow, which he believes belong to a “Woozle.” Pooh follows the tracks, not realizing that he’s walking in a circle. As such, he begins to notice that the tracks have multiplied, which he interprets as evidence of several Woozles.