User login

Shift from Productivity to Value-Based Compensation Gains Momentum

At the 2011 SHM annual meeting in Dallas, I served on an expert panel that reviewed the latest hospitalist survey data. Included in this review were the latest compensation and productivity figures. As the session concluded, I was satisfied that the panel had discussed important information in an accessible way; however, the keynote speaker who followed us to address an entirely different topic began his talk by pointing out that the data we had reviewed, including things like wRVUs, would very soon have little to do with compensation for any physician, regardless of specialty. He implied, quite persuasively, that we were pretty old school to be talking about wRVUs and compensation based on productivity; everyone should be prepared for and embrace compensation based on value, not production.

I hear a similar sentiment reasonably often. And I agree, but I think many make the mistake of oversimplifying the issue.

Physician Value-Based Payment

Measurement of physician performance using costs, quality, and outcomes has already begun and will influence Medicare payments to doctors beginning in 2015 for large groups (>100 providers with any mix of specialties billing under the same tax ID number) and in 2017 for smaller groups.

If Medicare is moving away from payment based on wRVUs, likely followed soon by other payors, then hospitalist compensation should do the same. But I don’t think that changes the potential role of compensation based on productivity.

Compensation Should Include Performance and Productivity Metrics

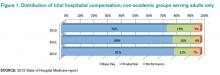

Survey data show a move from an essentially fixed annual compensation early in our field to an inclusion of components tied to performance several years before the introduction of the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier program. Data from SHM’s 2010, 2011, and 2012 State of Hospital Medicine reports (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) show that a small, but probably increasing, part of compensation has been tied to performance on things like patient satisfaction and core measures (see “Distribution of Total Hospitalist Compensation,” below). Note that the percentages in the chart refer to the fraction of total compensation dollars allocated to each domain and not the portion of hospitalists who have compensation tied to each domain.

Over the same three years, the percentage of compensation tied to productivity has been decreasing overall, while “private groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on productivity, and hospital-employed groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on performance.”

Matching Performance Compensation to Medicare’s Value-Based Modifier

It makes sense for physician compensation to generally mirror Medicare and other payor professional fee reimbursement formulas. But, in that regard, hospitalists are ahead of the market already, because the portion of dollars allocated to performance (value) in hospitalist compensation plans already exceeds the 2% or less portion of Medicare reimbursement that is influenced by performance.

Medicare will steadily increase the portion of reimbursement allocated to performance (value) and decrease the part tied solely to wRVUs. So it makes sense that hospitalist compensation plans should do the same. Who knows, within the next 5-10 years, hospitalists, and potentially doctors in all specialties, might see 20% to 50% of their compensation tied to performance. I think that might be a good thing, as long as we can come up with effective measures of performance and value—not an easy thing to do in any business or industry.

Future Role of Productivity Compensation

I don’t think all the talk about value-based reimbursement means we should abandon the idea of connecting a portion of compensation to productivity. The first two practice management columns I wrote for The Hospitalist appeared in May 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/252413/The_Sweet_Spot.html) and June 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/246297.html) and recommended tying a meaningful portion of compensation to individual hospitalist productivity, and I think it still makes sense to do so.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

In any business or industry, financial performance is connected to the amount of product produced and its value. In the future, both metrics will determine reimbursement for even the highest performing healthcare providers. The new emphasis on value won’t ever make it unnecessary to produce at a reasonable level.

Unquestionably, there are many high-performing hospitalist practices with little or no productivity component in the compensation formula. So it isn’t an absolute sine qua non for success. But I think many practices dismiss it as a viable option when it might solve problems and liberate individuals in the group to exercise some autonomy in finding their own sweet spot between workload and compensation.

It will be interesting to see if future surveys show that the portion of dollars tied to hospitalist productivity continues to decrease, despite what I see as its potential benefits.

At the 2011 SHM annual meeting in Dallas, I served on an expert panel that reviewed the latest hospitalist survey data. Included in this review were the latest compensation and productivity figures. As the session concluded, I was satisfied that the panel had discussed important information in an accessible way; however, the keynote speaker who followed us to address an entirely different topic began his talk by pointing out that the data we had reviewed, including things like wRVUs, would very soon have little to do with compensation for any physician, regardless of specialty. He implied, quite persuasively, that we were pretty old school to be talking about wRVUs and compensation based on productivity; everyone should be prepared for and embrace compensation based on value, not production.

I hear a similar sentiment reasonably often. And I agree, but I think many make the mistake of oversimplifying the issue.

Physician Value-Based Payment

Measurement of physician performance using costs, quality, and outcomes has already begun and will influence Medicare payments to doctors beginning in 2015 for large groups (>100 providers with any mix of specialties billing under the same tax ID number) and in 2017 for smaller groups.

If Medicare is moving away from payment based on wRVUs, likely followed soon by other payors, then hospitalist compensation should do the same. But I don’t think that changes the potential role of compensation based on productivity.

Compensation Should Include Performance and Productivity Metrics

Survey data show a move from an essentially fixed annual compensation early in our field to an inclusion of components tied to performance several years before the introduction of the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier program. Data from SHM’s 2010, 2011, and 2012 State of Hospital Medicine reports (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) show that a small, but probably increasing, part of compensation has been tied to performance on things like patient satisfaction and core measures (see “Distribution of Total Hospitalist Compensation,” below). Note that the percentages in the chart refer to the fraction of total compensation dollars allocated to each domain and not the portion of hospitalists who have compensation tied to each domain.

Over the same three years, the percentage of compensation tied to productivity has been decreasing overall, while “private groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on productivity, and hospital-employed groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on performance.”

Matching Performance Compensation to Medicare’s Value-Based Modifier

It makes sense for physician compensation to generally mirror Medicare and other payor professional fee reimbursement formulas. But, in that regard, hospitalists are ahead of the market already, because the portion of dollars allocated to performance (value) in hospitalist compensation plans already exceeds the 2% or less portion of Medicare reimbursement that is influenced by performance.

Medicare will steadily increase the portion of reimbursement allocated to performance (value) and decrease the part tied solely to wRVUs. So it makes sense that hospitalist compensation plans should do the same. Who knows, within the next 5-10 years, hospitalists, and potentially doctors in all specialties, might see 20% to 50% of their compensation tied to performance. I think that might be a good thing, as long as we can come up with effective measures of performance and value—not an easy thing to do in any business or industry.

Future Role of Productivity Compensation

I don’t think all the talk about value-based reimbursement means we should abandon the idea of connecting a portion of compensation to productivity. The first two practice management columns I wrote for The Hospitalist appeared in May 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/252413/The_Sweet_Spot.html) and June 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/246297.html) and recommended tying a meaningful portion of compensation to individual hospitalist productivity, and I think it still makes sense to do so.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

In any business or industry, financial performance is connected to the amount of product produced and its value. In the future, both metrics will determine reimbursement for even the highest performing healthcare providers. The new emphasis on value won’t ever make it unnecessary to produce at a reasonable level.

Unquestionably, there are many high-performing hospitalist practices with little or no productivity component in the compensation formula. So it isn’t an absolute sine qua non for success. But I think many practices dismiss it as a viable option when it might solve problems and liberate individuals in the group to exercise some autonomy in finding their own sweet spot between workload and compensation.

It will be interesting to see if future surveys show that the portion of dollars tied to hospitalist productivity continues to decrease, despite what I see as its potential benefits.

At the 2011 SHM annual meeting in Dallas, I served on an expert panel that reviewed the latest hospitalist survey data. Included in this review were the latest compensation and productivity figures. As the session concluded, I was satisfied that the panel had discussed important information in an accessible way; however, the keynote speaker who followed us to address an entirely different topic began his talk by pointing out that the data we had reviewed, including things like wRVUs, would very soon have little to do with compensation for any physician, regardless of specialty. He implied, quite persuasively, that we were pretty old school to be talking about wRVUs and compensation based on productivity; everyone should be prepared for and embrace compensation based on value, not production.

I hear a similar sentiment reasonably often. And I agree, but I think many make the mistake of oversimplifying the issue.

Physician Value-Based Payment

Measurement of physician performance using costs, quality, and outcomes has already begun and will influence Medicare payments to doctors beginning in 2015 for large groups (>100 providers with any mix of specialties billing under the same tax ID number) and in 2017 for smaller groups.

If Medicare is moving away from payment based on wRVUs, likely followed soon by other payors, then hospitalist compensation should do the same. But I don’t think that changes the potential role of compensation based on productivity.

Compensation Should Include Performance and Productivity Metrics

Survey data show a move from an essentially fixed annual compensation early in our field to an inclusion of components tied to performance several years before the introduction of the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier program. Data from SHM’s 2010, 2011, and 2012 State of Hospital Medicine reports (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) show that a small, but probably increasing, part of compensation has been tied to performance on things like patient satisfaction and core measures (see “Distribution of Total Hospitalist Compensation,” below). Note that the percentages in the chart refer to the fraction of total compensation dollars allocated to each domain and not the portion of hospitalists who have compensation tied to each domain.

Over the same three years, the percentage of compensation tied to productivity has been decreasing overall, while “private groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on productivity, and hospital-employed groups are more likely to pay a higher proportion of compensation based on performance.”

Matching Performance Compensation to Medicare’s Value-Based Modifier

It makes sense for physician compensation to generally mirror Medicare and other payor professional fee reimbursement formulas. But, in that regard, hospitalists are ahead of the market already, because the portion of dollars allocated to performance (value) in hospitalist compensation plans already exceeds the 2% or less portion of Medicare reimbursement that is influenced by performance.

Medicare will steadily increase the portion of reimbursement allocated to performance (value) and decrease the part tied solely to wRVUs. So it makes sense that hospitalist compensation plans should do the same. Who knows, within the next 5-10 years, hospitalists, and potentially doctors in all specialties, might see 20% to 50% of their compensation tied to performance. I think that might be a good thing, as long as we can come up with effective measures of performance and value—not an easy thing to do in any business or industry.

Future Role of Productivity Compensation

I don’t think all the talk about value-based reimbursement means we should abandon the idea of connecting a portion of compensation to productivity. The first two practice management columns I wrote for The Hospitalist appeared in May 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/252413/The_Sweet_Spot.html) and June 2006 (www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/246297.html) and recommended tying a meaningful portion of compensation to individual hospitalist productivity, and I think it still makes sense to do so.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

In any business or industry, financial performance is connected to the amount of product produced and its value. In the future, both metrics will determine reimbursement for even the highest performing healthcare providers. The new emphasis on value won’t ever make it unnecessary to produce at a reasonable level.

Unquestionably, there are many high-performing hospitalist practices with little or no productivity component in the compensation formula. So it isn’t an absolute sine qua non for success. But I think many practices dismiss it as a viable option when it might solve problems and liberate individuals in the group to exercise some autonomy in finding their own sweet spot between workload and compensation.

It will be interesting to see if future surveys show that the portion of dollars tied to hospitalist productivity continues to decrease, despite what I see as its potential benefits.

How Many Americans Will Remain Uninsured?

The question of whether health insurance equals healthcare access is complicated in the roughly two dozen states that have chosen not to expand Medicaid—an option granted by the U.S. Supreme Court in its June 2012 decision that upheld the law’s main tenets. Even with the federal government paying the full cost for the first three years (decreasing to 90% by 2020), some states have argued that the economic burden will be too great.

According to a recent analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation, roughly five million uninsured adults may now fall into a “coverage gap” as a result. In essence, they will earn too much to be covered under the highly variable Medicaid caps established by individual states but too little to receive any federal tax credits to help pay for insurance in the exchanges. With limited options, the report suggests, they are likely to remain uninsured.

Safety net hospitals also may be squeezed between conflicting state and federal Medicaid priorities. During the initial Affordable Care Act (ACA) negotiations, hospitals agreed to $155 billion in cuts over 10 years, including sharp reductions in Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, in anticipation of seeing a significant decrease in uninsured patients. Despite lower DSH payments, the hospitals expected to recoup the money through more Medicaid or private insurance reimbursements.

"The Medicaid expansion being optional throws a kink in all of that,” says Leighton Ku, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Health Policy Research at George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services in Washington, D.C.

The ongoing open enrollment in insurance exchanges will make up part of the total. But in states that are not expanding Medicaid, the number of newly insured patients may not compensate for the DSH reductions. Robert Berenson, MD, a senior fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Institute, a nonpartisan think tank focused on social and economic policy, says the resulting net loss could put some hospitals under additional financial strain.

"There will be pressure within the states from hospitals and from the business community to expand Medicaid because, otherwise, they’re bearing the burden of it,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

The question of whether health insurance equals healthcare access is complicated in the roughly two dozen states that have chosen not to expand Medicaid—an option granted by the U.S. Supreme Court in its June 2012 decision that upheld the law’s main tenets. Even with the federal government paying the full cost for the first three years (decreasing to 90% by 2020), some states have argued that the economic burden will be too great.

According to a recent analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation, roughly five million uninsured adults may now fall into a “coverage gap” as a result. In essence, they will earn too much to be covered under the highly variable Medicaid caps established by individual states but too little to receive any federal tax credits to help pay for insurance in the exchanges. With limited options, the report suggests, they are likely to remain uninsured.

Safety net hospitals also may be squeezed between conflicting state and federal Medicaid priorities. During the initial Affordable Care Act (ACA) negotiations, hospitals agreed to $155 billion in cuts over 10 years, including sharp reductions in Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, in anticipation of seeing a significant decrease in uninsured patients. Despite lower DSH payments, the hospitals expected to recoup the money through more Medicaid or private insurance reimbursements.

"The Medicaid expansion being optional throws a kink in all of that,” says Leighton Ku, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Health Policy Research at George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services in Washington, D.C.

The ongoing open enrollment in insurance exchanges will make up part of the total. But in states that are not expanding Medicaid, the number of newly insured patients may not compensate for the DSH reductions. Robert Berenson, MD, a senior fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Institute, a nonpartisan think tank focused on social and economic policy, says the resulting net loss could put some hospitals under additional financial strain.

"There will be pressure within the states from hospitals and from the business community to expand Medicaid because, otherwise, they’re bearing the burden of it,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

The question of whether health insurance equals healthcare access is complicated in the roughly two dozen states that have chosen not to expand Medicaid—an option granted by the U.S. Supreme Court in its June 2012 decision that upheld the law’s main tenets. Even with the federal government paying the full cost for the first three years (decreasing to 90% by 2020), some states have argued that the economic burden will be too great.

According to a recent analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation, roughly five million uninsured adults may now fall into a “coverage gap” as a result. In essence, they will earn too much to be covered under the highly variable Medicaid caps established by individual states but too little to receive any federal tax credits to help pay for insurance in the exchanges. With limited options, the report suggests, they are likely to remain uninsured.

Safety net hospitals also may be squeezed between conflicting state and federal Medicaid priorities. During the initial Affordable Care Act (ACA) negotiations, hospitals agreed to $155 billion in cuts over 10 years, including sharp reductions in Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, in anticipation of seeing a significant decrease in uninsured patients. Despite lower DSH payments, the hospitals expected to recoup the money through more Medicaid or private insurance reimbursements.

"The Medicaid expansion being optional throws a kink in all of that,” says Leighton Ku, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Health Policy Research at George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services in Washington, D.C.

The ongoing open enrollment in insurance exchanges will make up part of the total. But in states that are not expanding Medicaid, the number of newly insured patients may not compensate for the DSH reductions. Robert Berenson, MD, a senior fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Institute, a nonpartisan think tank focused on social and economic policy, says the resulting net loss could put some hospitals under additional financial strain.

"There will be pressure within the states from hospitals and from the business community to expand Medicaid because, otherwise, they’re bearing the burden of it,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Hospitalist Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, Says Obamacare Might Impact Patient Access, Physician Workload

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Lenchus

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Lenchus

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Lenchus

Hospitalist Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, Discusses How the ACA Might Accelerate the Drive Toward ACO-style of Care

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Hilger

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Hilger

Click here to listen to more of our interview with Dr. Hilger

SHM Helps Hospitals Comply With Two-Midnight Rule for Patient Admissions

As many hospitalists are probably acutely aware, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is putting a new rule into effect that will greatly impact how inpatient admission decisions are made. The rule, known as the “two-midnight rule,” states that if the admitting practitioner admits a Medicare beneficiary as an inpatient with the reasonable expectation that the beneficiary will require care that “crosses two midnights” and this decision is justified in the medical record, Medicare Part A payment is “generally appropriate.”

While there are multiple caveats, exceptions, and details, this rule can be simply articulated: If the admitting physician feels a patient will be in the hospital for a period longer than two midnights and the medical record supports this determination, the patient is an inpatient. Stays expected to be shorter than two midnights should be under observation status.

This new policy is an attempt to respond both to hospital calls for more guidance about when a beneficiary is appropriately treated as an inpatient—and paid by Medicare—and concerns about increasingly long hospital stays under observation status. Most hospitalists wrestle with status determination issues on a daily basis.

SHM is aware of the struggle and has been advocating on behalf of hospitalists to help shape observation status and the two-midnight rule. When the rule was first proposed, SHM voiced serious concerns about its utility and how it was unlikely to solve the overall confusion surrounding inpatient status determinations. Nevertheless, CMS finalized the rule as an attempt to begin addressing the problem.

Faced with an increasingly loud chorus of providers and hospitals concerned about the implementation of the new policy, CMS agreed to delay full enforcement from the original date of Oct. 1, 2013, until March 31, 2014.

During the delayed enforcement period, hospitals will be expected to begin implementing the two-midnight rule, and auditors will be giving hospitals non-punitive feedback on their application of the policy. To accomplish this, CMS is instructing Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) to review a sample of 10 to 25 inpatient hospital claims spanning less than two midnights after admission for each hospital. This probe sample will be used to assist hospitals with implementing the new requirements correctly. To give an additional level of comfort during this adjustment period, CMS has announced that it will not conduct post-payment patient status reviews for claims with dates of admission Oct. 1, 2013, through March 31, 2014.

Unfortunately, beyond the vague guidance CMS has offered thus far, there is no foolproof guide to establishing new hospital admissions policies that comply with the rule. As a result, there likely will be wide variation among hospitals.

To assist in sorting out the confusion, SHM will be hosting a webinar this month with case studies from several hospitals. The focus will be on the internal processes each hospital is using to implement the rule and how they were developed. Sharing and learning from national implementation experiences is a valuable way for hospitalists to gain new perspectives and to bring those experiences to their home institutions when considering their own roles in meeting the new admissions criteria head on.

For more information about the webinar and to register, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org today.

Josh Boswell is SHM’s senior manager of government relations.

As many hospitalists are probably acutely aware, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is putting a new rule into effect that will greatly impact how inpatient admission decisions are made. The rule, known as the “two-midnight rule,” states that if the admitting practitioner admits a Medicare beneficiary as an inpatient with the reasonable expectation that the beneficiary will require care that “crosses two midnights” and this decision is justified in the medical record, Medicare Part A payment is “generally appropriate.”

While there are multiple caveats, exceptions, and details, this rule can be simply articulated: If the admitting physician feels a patient will be in the hospital for a period longer than two midnights and the medical record supports this determination, the patient is an inpatient. Stays expected to be shorter than two midnights should be under observation status.

This new policy is an attempt to respond both to hospital calls for more guidance about when a beneficiary is appropriately treated as an inpatient—and paid by Medicare—and concerns about increasingly long hospital stays under observation status. Most hospitalists wrestle with status determination issues on a daily basis.

SHM is aware of the struggle and has been advocating on behalf of hospitalists to help shape observation status and the two-midnight rule. When the rule was first proposed, SHM voiced serious concerns about its utility and how it was unlikely to solve the overall confusion surrounding inpatient status determinations. Nevertheless, CMS finalized the rule as an attempt to begin addressing the problem.

Faced with an increasingly loud chorus of providers and hospitals concerned about the implementation of the new policy, CMS agreed to delay full enforcement from the original date of Oct. 1, 2013, until March 31, 2014.

During the delayed enforcement period, hospitals will be expected to begin implementing the two-midnight rule, and auditors will be giving hospitals non-punitive feedback on their application of the policy. To accomplish this, CMS is instructing Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) to review a sample of 10 to 25 inpatient hospital claims spanning less than two midnights after admission for each hospital. This probe sample will be used to assist hospitals with implementing the new requirements correctly. To give an additional level of comfort during this adjustment period, CMS has announced that it will not conduct post-payment patient status reviews for claims with dates of admission Oct. 1, 2013, through March 31, 2014.

Unfortunately, beyond the vague guidance CMS has offered thus far, there is no foolproof guide to establishing new hospital admissions policies that comply with the rule. As a result, there likely will be wide variation among hospitals.

To assist in sorting out the confusion, SHM will be hosting a webinar this month with case studies from several hospitals. The focus will be on the internal processes each hospital is using to implement the rule and how they were developed. Sharing and learning from national implementation experiences is a valuable way for hospitalists to gain new perspectives and to bring those experiences to their home institutions when considering their own roles in meeting the new admissions criteria head on.

For more information about the webinar and to register, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org today.

Josh Boswell is SHM’s senior manager of government relations.

As many hospitalists are probably acutely aware, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is putting a new rule into effect that will greatly impact how inpatient admission decisions are made. The rule, known as the “two-midnight rule,” states that if the admitting practitioner admits a Medicare beneficiary as an inpatient with the reasonable expectation that the beneficiary will require care that “crosses two midnights” and this decision is justified in the medical record, Medicare Part A payment is “generally appropriate.”

While there are multiple caveats, exceptions, and details, this rule can be simply articulated: If the admitting physician feels a patient will be in the hospital for a period longer than two midnights and the medical record supports this determination, the patient is an inpatient. Stays expected to be shorter than two midnights should be under observation status.

This new policy is an attempt to respond both to hospital calls for more guidance about when a beneficiary is appropriately treated as an inpatient—and paid by Medicare—and concerns about increasingly long hospital stays under observation status. Most hospitalists wrestle with status determination issues on a daily basis.

SHM is aware of the struggle and has been advocating on behalf of hospitalists to help shape observation status and the two-midnight rule. When the rule was first proposed, SHM voiced serious concerns about its utility and how it was unlikely to solve the overall confusion surrounding inpatient status determinations. Nevertheless, CMS finalized the rule as an attempt to begin addressing the problem.

Faced with an increasingly loud chorus of providers and hospitals concerned about the implementation of the new policy, CMS agreed to delay full enforcement from the original date of Oct. 1, 2013, until March 31, 2014.

During the delayed enforcement period, hospitals will be expected to begin implementing the two-midnight rule, and auditors will be giving hospitals non-punitive feedback on their application of the policy. To accomplish this, CMS is instructing Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) to review a sample of 10 to 25 inpatient hospital claims spanning less than two midnights after admission for each hospital. This probe sample will be used to assist hospitals with implementing the new requirements correctly. To give an additional level of comfort during this adjustment period, CMS has announced that it will not conduct post-payment patient status reviews for claims with dates of admission Oct. 1, 2013, through March 31, 2014.

Unfortunately, beyond the vague guidance CMS has offered thus far, there is no foolproof guide to establishing new hospital admissions policies that comply with the rule. As a result, there likely will be wide variation among hospitals.

To assist in sorting out the confusion, SHM will be hosting a webinar this month with case studies from several hospitals. The focus will be on the internal processes each hospital is using to implement the rule and how they were developed. Sharing and learning from national implementation experiences is a valuable way for hospitalists to gain new perspectives and to bring those experiences to their home institutions when considering their own roles in meeting the new admissions criteria head on.

For more information about the webinar and to register, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org today.

Josh Boswell is SHM’s senior manager of government relations.

Affordable Care Act Latest in Half-Century of Healthcare Reform

Initial Efforts

1965

• President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Social Security Act, which authorizes both Medicare and Medicaid; the law is widely labeled the biggest healthcare reform of the past century.

1993

• President Bill Clinton attempts to craft universal healthcare legislation that includes both individual and employer mandates. He appoints his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, as chair of the White House Task Force on Health Reform. The President’s Health Security Act ultimately fails in Congress.

1997

• State Children’s Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP) authorized by Congress, covering low-income children in families above Medicaid eligibility levels.

2006

• Massachusetts (followed by Vermont in 2011) passes legislation that expands healthcare coverage to nearly all state residents; the Massachusetts law is later deemed a template for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)

March 23, 2010

• President Obama signs the ACA into law. Among the law’s early provisions: Medicare beneficiaries who reach the Part D drug coverage gap begin receiving $250 rebates, and the IRS begins allowing tax credits to small employers that offer health insurance to their employees.

July 1, 2010

• Federal government begins enrolling patients with pre-existing conditions in a temporary Pre-Existing Condition Insurance Plan (PCIP).

• Healthcare.gov website debuts.

• IRS begins assessing 10% tax on indoor tanning.

Sep. 23, 2010

• Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) launches with 21-member board of directors.

• For new insurance plans or those renewed on or after this date, parents are allowed to keep adult children on their health policies until they turn 26 (many private plans voluntarily offered this option earlier).

• HHS bans insurers from imposing lifetime coverage limits and from denying health coverage to children with pre-existing conditions or excluding specific conditions from coverage.

• HHS requires new and renewing health plans to eliminate cost sharing for certain preventive services recommended by U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Sep. 30, 2010

• U.S. Comptroller General appoints 15 members to National Health Care Workforce Commission (commission does not secure funding).

December 30, 2010

• Medicare debuts first phase of Physician Compare website.

Jan. 1, 2011

• CMS begins closing Medicare Part D drug coverage gap.

• Medicare begins paying 10% bonus for primary care services (funded through 2015).

• Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation debuts, with a focus on testing new payment and care delivery systems.

March 23, 2011

• HHS begins providing grants to individual states to help set up health insurance exchanges.

July 1, 2011

• CMS stops paying for Medicaid services related to specific hospital-acquired infections.

Oct. 1, 2011

• Fifteen-member Independent Payment Advisory Board is formally established (but no members are nominated). The IPAB is charged with issuing legislative recommendations to lower Medicare spending growth, but only if projected costs exceed a certain threshold.

Jan. 1, 2012

• CMS launches Medicaid bundled-payment demonstration and Accountable Care Organization (ACO) incentive program.

• CMS reduces Medicare Advantage rebates but offers bonuses to high-quality plans.

Aug. 1, 2012

• HHS requires most new and renewing health plans to eliminate cost sharing for women’s preventive health services, including contraception.

Oct. 1, 2012

• CMS begins its Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program in Medicare, starting with a 1% withholding in FY2013.

• CMS begins reducing Medicare payments based on excess hospital readmissions, starting with a 1% penalty in FY2013.

Jan. 1, 2013

• CMS starts five-year bundled payment pilot program for Medicare, covering 10 conditions.

• CMS increases Medicaid payments for primary care services to 100% of Medicare’s rate (funded for two years).

• IRS increases Medicare tax rate to 2.35% on individuals earning more than $200,000 and on married couples earning more than $250,000; also imposes 3.8% tax on unearned income among high-income taxpayers.

• IRS begins assessing excise tax of 2.3% on sale of taxable medical devices.

Jan. 2, 2013

• Sequestration results in across-the-board cuts of 2% in Medicare reimbursements.

July 1, 2013

• DHS officially launches Consumer Operated and Oriented Plan (CO-OP) to encourage growth of nonprofit health insurers (roughly $2 billion in loans given to co-ops in 23 states by end of 2012).

Oct. 1, 2013

• Open enrollment begins for state- and federal government-run health insurance exchanges and expanded Medicaid; the rollout is marred by multiple computer glitches.

• CMS lowers Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments by 75%, starting in FY2014 but plans to supplement these payments based on each hospital’s share of uncompensated care.

• CMS lowers Medicaid DSH payments by $22 billion over 10 years, beginning with $500 million reduction in FY2014.

Jan. 1, 2014

• Coverage begins through health insurance exchanges. Individuals and families with incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level can receive subsidies to help pay for premiums.

• Voluntary Medicaid expansions expected to take place in roughly half of all states, for individuals up to 138% of the federal poverty level.

• Insurers banned from imposing annual limits on coverage, from restricting coverage due to pre-existing conditions, and from basing premiums on gender.

• Insurers required to cover 10 “essential health benefits,” including medication and maternity care.

March 31, 2014

• Open enrollment closes for health insurance exchanges; under the “individual mandate,” people who qualify but don’t buy insurance by this date will be penalized up to 1% of income (penalty increases in subsequent years).

Oct. 1, 2014

• CMS imposes 1% reduction in payments to hospitals with excess hospital-acquired conditions (FY2015).

• CMS imposes penalties on hospitals that haven’t met electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use requirements.

Jan. 1, 2015

• Employer Shared Responsibility Payment, or the “employer mandate,” begins (delayed from Jan. 1, 2014). With a few exceptions, employers with more than 50 employees must offer coverage or pay a fine.

• CMS begins imposing fines based on doctors who didn’t meet Physician Quality Reporting System requirements during 2013, with an initial 1.5% penalty that rises to 2% in 2016.

Jan. 1, 2018

• High-cost, or so-called “Cadillac,” insurance plans—those with premiums over $10,200 for individuals or $27,500 for family coverage—will be assessed an excise tax.

Sources: Healthcare.gov, Commonwealth Fund, Kaiser Family Foundation, American Medical Association, Greater New York Hospital Association.

Initial Efforts

1965

• President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Social Security Act, which authorizes both Medicare and Medicaid; the law is widely labeled the biggest healthcare reform of the past century.

1993

• President Bill Clinton attempts to craft universal healthcare legislation that includes both individual and employer mandates. He appoints his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, as chair of the White House Task Force on Health Reform. The President’s Health Security Act ultimately fails in Congress.

1997

• State Children’s Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP) authorized by Congress, covering low-income children in families above Medicaid eligibility levels.

2006

• Massachusetts (followed by Vermont in 2011) passes legislation that expands healthcare coverage to nearly all state residents; the Massachusetts law is later deemed a template for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)

March 23, 2010

• President Obama signs the ACA into law. Among the law’s early provisions: Medicare beneficiaries who reach the Part D drug coverage gap begin receiving $250 rebates, and the IRS begins allowing tax credits to small employers that offer health insurance to their employees.

July 1, 2010

• Federal government begins enrolling patients with pre-existing conditions in a temporary Pre-Existing Condition Insurance Plan (PCIP).

• Healthcare.gov website debuts.

• IRS begins assessing 10% tax on indoor tanning.

Sep. 23, 2010

• Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) launches with 21-member board of directors.

• For new insurance plans or those renewed on or after this date, parents are allowed to keep adult children on their health policies until they turn 26 (many private plans voluntarily offered this option earlier).

• HHS bans insurers from imposing lifetime coverage limits and from denying health coverage to children with pre-existing conditions or excluding specific conditions from coverage.

• HHS requires new and renewing health plans to eliminate cost sharing for certain preventive services recommended by U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Sep. 30, 2010

• U.S. Comptroller General appoints 15 members to National Health Care Workforce Commission (commission does not secure funding).

December 30, 2010

• Medicare debuts first phase of Physician Compare website.

Jan. 1, 2011

• CMS begins closing Medicare Part D drug coverage gap.

• Medicare begins paying 10% bonus for primary care services (funded through 2015).

• Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation debuts, with a focus on testing new payment and care delivery systems.

March 23, 2011

• HHS begins providing grants to individual states to help set up health insurance exchanges.

July 1, 2011

• CMS stops paying for Medicaid services related to specific hospital-acquired infections.

Oct. 1, 2011

• Fifteen-member Independent Payment Advisory Board is formally established (but no members are nominated). The IPAB is charged with issuing legislative recommendations to lower Medicare spending growth, but only if projected costs exceed a certain threshold.

Jan. 1, 2012

• CMS launches Medicaid bundled-payment demonstration and Accountable Care Organization (ACO) incentive program.

• CMS reduces Medicare Advantage rebates but offers bonuses to high-quality plans.

Aug. 1, 2012

• HHS requires most new and renewing health plans to eliminate cost sharing for women’s preventive health services, including contraception.

Oct. 1, 2012

• CMS begins its Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program in Medicare, starting with a 1% withholding in FY2013.

• CMS begins reducing Medicare payments based on excess hospital readmissions, starting with a 1% penalty in FY2013.

Jan. 1, 2013

• CMS starts five-year bundled payment pilot program for Medicare, covering 10 conditions.

• CMS increases Medicaid payments for primary care services to 100% of Medicare’s rate (funded for two years).

• IRS increases Medicare tax rate to 2.35% on individuals earning more than $200,000 and on married couples earning more than $250,000; also imposes 3.8% tax on unearned income among high-income taxpayers.

• IRS begins assessing excise tax of 2.3% on sale of taxable medical devices.

Jan. 2, 2013

• Sequestration results in across-the-board cuts of 2% in Medicare reimbursements.

July 1, 2013

• DHS officially launches Consumer Operated and Oriented Plan (CO-OP) to encourage growth of nonprofit health insurers (roughly $2 billion in loans given to co-ops in 23 states by end of 2012).

Oct. 1, 2013

• Open enrollment begins for state- and federal government-run health insurance exchanges and expanded Medicaid; the rollout is marred by multiple computer glitches.

• CMS lowers Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments by 75%, starting in FY2014 but plans to supplement these payments based on each hospital’s share of uncompensated care.

• CMS lowers Medicaid DSH payments by $22 billion over 10 years, beginning with $500 million reduction in FY2014.

Jan. 1, 2014

• Coverage begins through health insurance exchanges. Individuals and families with incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level can receive subsidies to help pay for premiums.

• Voluntary Medicaid expansions expected to take place in roughly half of all states, for individuals up to 138% of the federal poverty level.

• Insurers banned from imposing annual limits on coverage, from restricting coverage due to pre-existing conditions, and from basing premiums on gender.

• Insurers required to cover 10 “essential health benefits,” including medication and maternity care.

March 31, 2014

• Open enrollment closes for health insurance exchanges; under the “individual mandate,” people who qualify but don’t buy insurance by this date will be penalized up to 1% of income (penalty increases in subsequent years).

Oct. 1, 2014

• CMS imposes 1% reduction in payments to hospitals with excess hospital-acquired conditions (FY2015).

• CMS imposes penalties on hospitals that haven’t met electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use requirements.

Jan. 1, 2015

• Employer Shared Responsibility Payment, or the “employer mandate,” begins (delayed from Jan. 1, 2014). With a few exceptions, employers with more than 50 employees must offer coverage or pay a fine.

• CMS begins imposing fines based on doctors who didn’t meet Physician Quality Reporting System requirements during 2013, with an initial 1.5% penalty that rises to 2% in 2016.

Jan. 1, 2018

• High-cost, or so-called “Cadillac,” insurance plans—those with premiums over $10,200 for individuals or $27,500 for family coverage—will be assessed an excise tax.

Sources: Healthcare.gov, Commonwealth Fund, Kaiser Family Foundation, American Medical Association, Greater New York Hospital Association.

Initial Efforts

1965

• President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Social Security Act, which authorizes both Medicare and Medicaid; the law is widely labeled the biggest healthcare reform of the past century.

1993

• President Bill Clinton attempts to craft universal healthcare legislation that includes both individual and employer mandates. He appoints his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, as chair of the White House Task Force on Health Reform. The President’s Health Security Act ultimately fails in Congress.

1997

• State Children’s Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP) authorized by Congress, covering low-income children in families above Medicaid eligibility levels.

2006

• Massachusetts (followed by Vermont in 2011) passes legislation that expands healthcare coverage to nearly all state residents; the Massachusetts law is later deemed a template for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)

March 23, 2010

• President Obama signs the ACA into law. Among the law’s early provisions: Medicare beneficiaries who reach the Part D drug coverage gap begin receiving $250 rebates, and the IRS begins allowing tax credits to small employers that offer health insurance to their employees.

July 1, 2010

• Federal government begins enrolling patients with pre-existing conditions in a temporary Pre-Existing Condition Insurance Plan (PCIP).

• Healthcare.gov website debuts.

• IRS begins assessing 10% tax on indoor tanning.

Sep. 23, 2010

• Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) launches with 21-member board of directors.

• For new insurance plans or those renewed on or after this date, parents are allowed to keep adult children on their health policies until they turn 26 (many private plans voluntarily offered this option earlier).

• HHS bans insurers from imposing lifetime coverage limits and from denying health coverage to children with pre-existing conditions or excluding specific conditions from coverage.

• HHS requires new and renewing health plans to eliminate cost sharing for certain preventive services recommended by U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Sep. 30, 2010

• U.S. Comptroller General appoints 15 members to National Health Care Workforce Commission (commission does not secure funding).

December 30, 2010

• Medicare debuts first phase of Physician Compare website.

Jan. 1, 2011

• CMS begins closing Medicare Part D drug coverage gap.

• Medicare begins paying 10% bonus for primary care services (funded through 2015).

• Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation debuts, with a focus on testing new payment and care delivery systems.

March 23, 2011

• HHS begins providing grants to individual states to help set up health insurance exchanges.

July 1, 2011

• CMS stops paying for Medicaid services related to specific hospital-acquired infections.

Oct. 1, 2011

• Fifteen-member Independent Payment Advisory Board is formally established (but no members are nominated). The IPAB is charged with issuing legislative recommendations to lower Medicare spending growth, but only if projected costs exceed a certain threshold.

Jan. 1, 2012

• CMS launches Medicaid bundled-payment demonstration and Accountable Care Organization (ACO) incentive program.

• CMS reduces Medicare Advantage rebates but offers bonuses to high-quality plans.

Aug. 1, 2012

• HHS requires most new and renewing health plans to eliminate cost sharing for women’s preventive health services, including contraception.

Oct. 1, 2012

• CMS begins its Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program in Medicare, starting with a 1% withholding in FY2013.

• CMS begins reducing Medicare payments based on excess hospital readmissions, starting with a 1% penalty in FY2013.

Jan. 1, 2013

• CMS starts five-year bundled payment pilot program for Medicare, covering 10 conditions.

• CMS increases Medicaid payments for primary care services to 100% of Medicare’s rate (funded for two years).

• IRS increases Medicare tax rate to 2.35% on individuals earning more than $200,000 and on married couples earning more than $250,000; also imposes 3.8% tax on unearned income among high-income taxpayers.

• IRS begins assessing excise tax of 2.3% on sale of taxable medical devices.

Jan. 2, 2013

• Sequestration results in across-the-board cuts of 2% in Medicare reimbursements.

July 1, 2013

• DHS officially launches Consumer Operated and Oriented Plan (CO-OP) to encourage growth of nonprofit health insurers (roughly $2 billion in loans given to co-ops in 23 states by end of 2012).

Oct. 1, 2013

• Open enrollment begins for state- and federal government-run health insurance exchanges and expanded Medicaid; the rollout is marred by multiple computer glitches.

• CMS lowers Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments by 75%, starting in FY2014 but plans to supplement these payments based on each hospital’s share of uncompensated care.

• CMS lowers Medicaid DSH payments by $22 billion over 10 years, beginning with $500 million reduction in FY2014.

Jan. 1, 2014

• Coverage begins through health insurance exchanges. Individuals and families with incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level can receive subsidies to help pay for premiums.

• Voluntary Medicaid expansions expected to take place in roughly half of all states, for individuals up to 138% of the federal poverty level.

• Insurers banned from imposing annual limits on coverage, from restricting coverage due to pre-existing conditions, and from basing premiums on gender.

• Insurers required to cover 10 “essential health benefits,” including medication and maternity care.

March 31, 2014

• Open enrollment closes for health insurance exchanges; under the “individual mandate,” people who qualify but don’t buy insurance by this date will be penalized up to 1% of income (penalty increases in subsequent years).

Oct. 1, 2014

• CMS imposes 1% reduction in payments to hospitals with excess hospital-acquired conditions (FY2015).

• CMS imposes penalties on hospitals that haven’t met electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use requirements.

Jan. 1, 2015

• Employer Shared Responsibility Payment, or the “employer mandate,” begins (delayed from Jan. 1, 2014). With a few exceptions, employers with more than 50 employees must offer coverage or pay a fine.

• CMS begins imposing fines based on doctors who didn’t meet Physician Quality Reporting System requirements during 2013, with an initial 1.5% penalty that rises to 2% in 2016.

Jan. 1, 2018

• High-cost, or so-called “Cadillac,” insurance plans—those with premiums over $10,200 for individuals or $27,500 for family coverage—will be assessed an excise tax.

Sources: Healthcare.gov, Commonwealth Fund, Kaiser Family Foundation, American Medical Association, Greater New York Hospital Association.

Six Interventions To Radically Improve the U.S. Healthcare System

We talk a lot about value in healthcare these days. Most everyone in healthcare knows the infamous quality/cost equation: the lower the cost and the higher the quality, the higher the value. Seems like a pretty straightforward equation; there aren’t even any coefficients, factorials, exponents, or square roots. Just two simple terms: quality and cost. How complicated could that possibly be?

The problem with the value equation is not its complexity on paper but the reinforcing barriers in our healthcare system that have made it impossible to improve the value equation on a large scale. Despite millions of hard-working, well-intentioned people in the healthcare industry, quality continues to be variable at best, and cost continues to rise. Healthcare currently consumes nearly 18% of the U.S. gross domestic product, threatening other aspects of the American economy, notably education and other federally subsidized programs.

A series of articles published between The New England Journal of Medicine and the Harvard Business Review aims to discover and suggest solutions to the issues currently ailing the U.S. healthcare system.1 The first installment focused on how to improve value on a large scale. The authors discuss the major barriers to realizing the value equation, along with some propositions for overcoming these barriers on a large scale.2 Although all six barriers are extremely difficult to surmount, the authors argue that because they are all mutually reinforcing in the current state, all will need to be addressed swiftly, tenaciously, and simultaneously.

Outlined here is a summary of the proposed interventions, and how these can and will affect hospitalists.

1

Providers need to organize themselves around what patients need, instead of around what providers do and how they are reimbursed. This will entail a shift from individual, discrete services to comprehensive, patient-focused care of medical conditions. The authors term these “Integrated Practice Units (IPU),” in which an entire team of providers organize themselves around the patient’s disease and provide comprehensive care across the range of the severity of the disease and the locations in which that disease is best served.

For hospitalists, working in multidisciplinary teams will come as second nature, but this also will require hospitalists to enhance the flexibility with which they see the patients and provide services exactly as the patients need, rather than based on arbitrary schedules and conveniences. Many hospitalists are already involved in comprehensive specialty care of high-volume surgical conditions, such as total hip and total knee patients, who usually come with a relatively predictable set of co-morbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, rheumatologic disease, or sickle cell anemia. The literature has clearly established the fact that high-volume specialty care centers can and do deliver higher value care (higher quality at lower cost), compared to lower volume, less “well-oiled” centers.

2

Providers need transparent and readily available information on quality and cost to move the value equation. As we all know, you can’t improve what you don’t measure. Hospitalists need to work collaboratively with their hospital systems to collect and widely report on quality and cost metrics for the patients they serve. These quality metrics should not only focus on those process and outcome measures that must currently be reported (internally or externally); hospitalists should seek out the metrics that really matter to patients, such as achieving functional status (ambulating, eating, being pain free), shortening recovery time (getting back to work, playing with the grandchildren), and sustaining recovery for as long as possible (relapse, readmission, reoperation).

Hospitalists should embrace the transparency of these metrics and encourage attribution of the metrics to individual providers or provider groups. Metric transparency stimulates rapid improvements and fosters goal alignment. Measurement and reporting of cost is absolutely essential in moving the value equation. Hospitalists should advocate for widespread transparency of the costs of tests, products, supplies, and manpower, and these should be freely and openly shared with patients and their families, to engage them in discussions about value.

3

Reimbursement for services should reflect the actual cost of the service and should be bundled. Many hospitalists are likely already involved in some demonstration projects around bundled payments for care across a continuum. Many CMS demonstration projects have focused on high-volume, predictable conditions (total hip arthroplasty, for instance) or high-volume, less predictable but costly conditions (such as congestive heart failure or COPD). Some large employers also are contracting with high volume hospitals to perform semi-elective procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafting, and sending their employees out of state to these centers of excellence. Most hospitalists are already at least conceptually comfortable with being held accountable for the cost and quality of certain patient types, including reducing unnecessary variation and spending and avoiding preventable complications.

4

Care should be integrated into a smaller number of large delivery systems, instead of a large number of small, “do-it-all” systems. These large systems have to actually work for the good of the patients, integrating their care and not just providing duplicate services in each location. Each center should be able to deliver excellent care in some conditions, not adequate care in all conditions. The more complicated, complex care should be delivered in tertiary care centers, and the more predictable, less heterogeneous care conditions should be addressed in lower-cost, community settings. Integrated systems can direct the right patients to the right location, to enhance both quality and cost.

5

On a related thread, healthcare systems need to focus patients on getting the right care in the right location and teach them to be less concerned about geography. In the days when hospital length of stays were routinely in the double digits, patients naturally opted to receive any and all care in a location close to their home and family. But now that hospital stays are generally in single digits, proximity to home is less important than good value of care, and healthcare systems need to steer patients to the best care delivery site, even if it is not near their homes. Some large employers have started reimbursing patients and their families for the cost associated with traveling to the correct site of care. With the availability of easy, low-cost travel options, this can and should be feasible for most patients and their families.

6

Information technology systems need to enable patient-centered care. Although this seemed to be the premise of EHRs, in reality, most have focused on enhancing billing, revenue, and documentation, rather than closely tracking the health, wellness, outcomes, and cost of individual patients throughout the care continuum. In the healthcare system of the future, the patient-centered EHR has to be readily accessible to all care providers, as well as to the patients themselves; it has to be easy to input and extract data; and it has to use common definitions for data.

Hospitalists would welcome such EHRs and should work tirelessly to achieve them within the healthcare system.

Conclusion

Although no single suggestion is wholly unappealing to the field of hospital medicine, accomplishing all of these quickly and simultaneously will be extremely challenging. It will take tremendous leadership and a bit of faith in the end goal. But the status quo is not an option, and current healthcare spending threatens the American Dream. Hospitalists can—and should—be pivotal in leading, or at least cooperating in, the achievement of this future-state, high-value healthcare system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

We talk a lot about value in healthcare these days. Most everyone in healthcare knows the infamous quality/cost equation: the lower the cost and the higher the quality, the higher the value. Seems like a pretty straightforward equation; there aren’t even any coefficients, factorials, exponents, or square roots. Just two simple terms: quality and cost. How complicated could that possibly be?

The problem with the value equation is not its complexity on paper but the reinforcing barriers in our healthcare system that have made it impossible to improve the value equation on a large scale. Despite millions of hard-working, well-intentioned people in the healthcare industry, quality continues to be variable at best, and cost continues to rise. Healthcare currently consumes nearly 18% of the U.S. gross domestic product, threatening other aspects of the American economy, notably education and other federally subsidized programs.

A series of articles published between The New England Journal of Medicine and the Harvard Business Review aims to discover and suggest solutions to the issues currently ailing the U.S. healthcare system.1 The first installment focused on how to improve value on a large scale. The authors discuss the major barriers to realizing the value equation, along with some propositions for overcoming these barriers on a large scale.2 Although all six barriers are extremely difficult to surmount, the authors argue that because they are all mutually reinforcing in the current state, all will need to be addressed swiftly, tenaciously, and simultaneously.

Outlined here is a summary of the proposed interventions, and how these can and will affect hospitalists.

1

Providers need to organize themselves around what patients need, instead of around what providers do and how they are reimbursed. This will entail a shift from individual, discrete services to comprehensive, patient-focused care of medical conditions. The authors term these “Integrated Practice Units (IPU),” in which an entire team of providers organize themselves around the patient’s disease and provide comprehensive care across the range of the severity of the disease and the locations in which that disease is best served.

For hospitalists, working in multidisciplinary teams will come as second nature, but this also will require hospitalists to enhance the flexibility with which they see the patients and provide services exactly as the patients need, rather than based on arbitrary schedules and conveniences. Many hospitalists are already involved in comprehensive specialty care of high-volume surgical conditions, such as total hip and total knee patients, who usually come with a relatively predictable set of co-morbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, rheumatologic disease, or sickle cell anemia. The literature has clearly established the fact that high-volume specialty care centers can and do deliver higher value care (higher quality at lower cost), compared to lower volume, less “well-oiled” centers.

2

Providers need transparent and readily available information on quality and cost to move the value equation. As we all know, you can’t improve what you don’t measure. Hospitalists need to work collaboratively with their hospital systems to collect and widely report on quality and cost metrics for the patients they serve. These quality metrics should not only focus on those process and outcome measures that must currently be reported (internally or externally); hospitalists should seek out the metrics that really matter to patients, such as achieving functional status (ambulating, eating, being pain free), shortening recovery time (getting back to work, playing with the grandchildren), and sustaining recovery for as long as possible (relapse, readmission, reoperation).

Hospitalists should embrace the transparency of these metrics and encourage attribution of the metrics to individual providers or provider groups. Metric transparency stimulates rapid improvements and fosters goal alignment. Measurement and reporting of cost is absolutely essential in moving the value equation. Hospitalists should advocate for widespread transparency of the costs of tests, products, supplies, and manpower, and these should be freely and openly shared with patients and their families, to engage them in discussions about value.

3

Reimbursement for services should reflect the actual cost of the service and should be bundled. Many hospitalists are likely already involved in some demonstration projects around bundled payments for care across a continuum. Many CMS demonstration projects have focused on high-volume, predictable conditions (total hip arthroplasty, for instance) or high-volume, less predictable but costly conditions (such as congestive heart failure or COPD). Some large employers also are contracting with high volume hospitals to perform semi-elective procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafting, and sending their employees out of state to these centers of excellence. Most hospitalists are already at least conceptually comfortable with being held accountable for the cost and quality of certain patient types, including reducing unnecessary variation and spending and avoiding preventable complications.

4

Care should be integrated into a smaller number of large delivery systems, instead of a large number of small, “do-it-all” systems. These large systems have to actually work for the good of the patients, integrating their care and not just providing duplicate services in each location. Each center should be able to deliver excellent care in some conditions, not adequate care in all conditions. The more complicated, complex care should be delivered in tertiary care centers, and the more predictable, less heterogeneous care conditions should be addressed in lower-cost, community settings. Integrated systems can direct the right patients to the right location, to enhance both quality and cost.

5

On a related thread, healthcare systems need to focus patients on getting the right care in the right location and teach them to be less concerned about geography. In the days when hospital length of stays were routinely in the double digits, patients naturally opted to receive any and all care in a location close to their home and family. But now that hospital stays are generally in single digits, proximity to home is less important than good value of care, and healthcare systems need to steer patients to the best care delivery site, even if it is not near their homes. Some large employers have started reimbursing patients and their families for the cost associated with traveling to the correct site of care. With the availability of easy, low-cost travel options, this can and should be feasible for most patients and their families.

6

Information technology systems need to enable patient-centered care. Although this seemed to be the premise of EHRs, in reality, most have focused on enhancing billing, revenue, and documentation, rather than closely tracking the health, wellness, outcomes, and cost of individual patients throughout the care continuum. In the healthcare system of the future, the patient-centered EHR has to be readily accessible to all care providers, as well as to the patients themselves; it has to be easy to input and extract data; and it has to use common definitions for data.

Hospitalists would welcome such EHRs and should work tirelessly to achieve them within the healthcare system.

Conclusion

Although no single suggestion is wholly unappealing to the field of hospital medicine, accomplishing all of these quickly and simultaneously will be extremely challenging. It will take tremendous leadership and a bit of faith in the end goal. But the status quo is not an option, and current healthcare spending threatens the American Dream. Hospitalists can—and should—be pivotal in leading, or at least cooperating in, the achievement of this future-state, high-value healthcare system.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

We talk a lot about value in healthcare these days. Most everyone in healthcare knows the infamous quality/cost equation: the lower the cost and the higher the quality, the higher the value. Seems like a pretty straightforward equation; there aren’t even any coefficients, factorials, exponents, or square roots. Just two simple terms: quality and cost. How complicated could that possibly be?

The problem with the value equation is not its complexity on paper but the reinforcing barriers in our healthcare system that have made it impossible to improve the value equation on a large scale. Despite millions of hard-working, well-intentioned people in the healthcare industry, quality continues to be variable at best, and cost continues to rise. Healthcare currently consumes nearly 18% of the U.S. gross domestic product, threatening other aspects of the American economy, notably education and other federally subsidized programs.

A series of articles published between The New England Journal of Medicine and the Harvard Business Review aims to discover and suggest solutions to the issues currently ailing the U.S. healthcare system.1 The first installment focused on how to improve value on a large scale. The authors discuss the major barriers to realizing the value equation, along with some propositions for overcoming these barriers on a large scale.2 Although all six barriers are extremely difficult to surmount, the authors argue that because they are all mutually reinforcing in the current state, all will need to be addressed swiftly, tenaciously, and simultaneously.

Outlined here is a summary of the proposed interventions, and how these can and will affect hospitalists.

1

Providers need to organize themselves around what patients need, instead of around what providers do and how they are reimbursed. This will entail a shift from individual, discrete services to comprehensive, patient-focused care of medical conditions. The authors term these “Integrated Practice Units (IPU),” in which an entire team of providers organize themselves around the patient’s disease and provide comprehensive care across the range of the severity of the disease and the locations in which that disease is best served.

For hospitalists, working in multidisciplinary teams will come as second nature, but this also will require hospitalists to enhance the flexibility with which they see the patients and provide services exactly as the patients need, rather than based on arbitrary schedules and conveniences. Many hospitalists are already involved in comprehensive specialty care of high-volume surgical conditions, such as total hip and total knee patients, who usually come with a relatively predictable set of co-morbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, rheumatologic disease, or sickle cell anemia. The literature has clearly established the fact that high-volume specialty care centers can and do deliver higher value care (higher quality at lower cost), compared to lower volume, less “well-oiled” centers.

2

Providers need transparent and readily available information on quality and cost to move the value equation. As we all know, you can’t improve what you don’t measure. Hospitalists need to work collaboratively with their hospital systems to collect and widely report on quality and cost metrics for the patients they serve. These quality metrics should not only focus on those process and outcome measures that must currently be reported (internally or externally); hospitalists should seek out the metrics that really matter to patients, such as achieving functional status (ambulating, eating, being pain free), shortening recovery time (getting back to work, playing with the grandchildren), and sustaining recovery for as long as possible (relapse, readmission, reoperation).

Hospitalists should embrace the transparency of these metrics and encourage attribution of the metrics to individual providers or provider groups. Metric transparency stimulates rapid improvements and fosters goal alignment. Measurement and reporting of cost is absolutely essential in moving the value equation. Hospitalists should advocate for widespread transparency of the costs of tests, products, supplies, and manpower, and these should be freely and openly shared with patients and their families, to engage them in discussions about value.

3

Reimbursement for services should reflect the actual cost of the service and should be bundled. Many hospitalists are likely already involved in some demonstration projects around bundled payments for care across a continuum. Many CMS demonstration projects have focused on high-volume, predictable conditions (total hip arthroplasty, for instance) or high-volume, less predictable but costly conditions (such as congestive heart failure or COPD). Some large employers also are contracting with high volume hospitals to perform semi-elective procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafting, and sending their employees out of state to these centers of excellence. Most hospitalists are already at least conceptually comfortable with being held accountable for the cost and quality of certain patient types, including reducing unnecessary variation and spending and avoiding preventable complications.

4

Care should be integrated into a smaller number of large delivery systems, instead of a large number of small, “do-it-all” systems. These large systems have to actually work for the good of the patients, integrating their care and not just providing duplicate services in each location. Each center should be able to deliver excellent care in some conditions, not adequate care in all conditions. The more complicated, complex care should be delivered in tertiary care centers, and the more predictable, less heterogeneous care conditions should be addressed in lower-cost, community settings. Integrated systems can direct the right patients to the right location, to enhance both quality and cost.

5

On a related thread, healthcare systems need to focus patients on getting the right care in the right location and teach them to be less concerned about geography. In the days when hospital length of stays were routinely in the double digits, patients naturally opted to receive any and all care in a location close to their home and family. But now that hospital stays are generally in single digits, proximity to home is less important than good value of care, and healthcare systems need to steer patients to the best care delivery site, even if it is not near their homes. Some large employers have started reimbursing patients and their families for the cost associated with traveling to the correct site of care. With the availability of easy, low-cost travel options, this can and should be feasible for most patients and their families.

6