User login

Implementation of a Pharmacist-Led Culture and Susceptibility Review System in Urgent Care and Outpatient Settings

Increasing antibiotic resistance is an urgent threat to public health and establishing a review service for antibiotics could alleviate this problem. As use of antibiotics escalates, the risk of resistance becomes increasingly important. Each year, approximately 269 million antibiotics are dispensed and at least 30% are prescribed inappropriately.1 In addition to inappropriate prescribing, increased antibiotic resistance can be caused by patients not completing an antibiotic course as recommended or inherent bacterial mutations. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year approximately 3 million individuals contract an antibiotic-resistant infection.2 By 2050, it is projected that drug-resistant conditions could cause 300 million deaths and might be as disastrous to the economy as the 2008 global financial crisis.3 Ensuring appropriate use of antibiotic therapy through antimicrobial stewardship can help combat this significant public health issue.

Antimicrobial stewardship promotes appropriate use of antimicrobials to improve patient outcomes, reduce health care costs, and decrease antimicrobial resistance. One study found that nearly 50% of patients discharged from the emergency department with antibiotics required therapy modification after culture and susceptibility results were returned.4 Both the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) support incorporating a clinical pharmacist into culture reviews.3 Several institutions have implemented a pharmacist-led culture review service to improve antibiotic usage, which has shown positive results. A retrospective case-control study at University of Rochester Medical Center showed reduced time to positive culture review and to patient or health care provider (HCP) notification when emergency medicine pharmacists were involved in culture review.5 A retrospective study at Carolinas Medical Center-Northeast showed 12% decreased readmission rate using pharmacist-implemented culture review compared with HCP review.6 Results from previous studies showed an overall improvement in patient safety through decreased use of inappropriate agents and reduced time on inappropriate antibiotic therapy.

Establishing a pharmacist-led culture review service at the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center (CVVAMC) in Dublin, Georgia, could decrease the time to review of positive culture results, time to patient or HCP notification, and readmission rates. CVVAMC provides outpatient primary care services to about 30,000 veterans in the central and southern regions of Georgia. Our facility has executed an antimicrobial stewardship program based on guidelines published in 2016 by IDSA and SHEA to guide optimal use of antibiotics. Clinical pharmacists play an active role in antimicrobial stewardship throughout the facility. Clinical responsibilities of the antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist include assessing therapy for inappropriate dual anaerobic coverage, evaluating inpatient culture results within 48 hours, dosing and monitoring antibiotic therapy, including vancomycin and aminoglycosides, and implementing IV to by-mouth conversions for appropriate patients. HCPs involved with antimicrobial stewardship could order an array of tests to assess a veteran’s condition, including cultures, when an infection is suspected.

Culture results take about 3 to 5 days, then HCPs evaluate the result to ensure current antibiotic therapy is appropriate. Patients might not receive timely follow-up because HCPs often have many laboratory alerts to sift through every day, and a protocol is not in place for pharmacists to adjust outpatient antimicrobial regimens based on culture results. Before implementing this project, there was no outpatient service for pharmacists to impact culture and susceptibility review. This project was initiated because a lead physician identified difficulty reviewing culture and susceptibility results. HCPs often work on rotating schedules, and there was a concern about possible delay in follow-up of results if a HCP was not scheduled to work for a period of time.

The purpose of this project was to implement an outpatient, pharmacist-managed culture and susceptibility review service to improve patient outcomes, including decreasing and preventing inappropriate antibiotic use. The primary objective was to design and implement a pharmacist-led review service to intervene in cases of mismatched antibiotic bacteria combinations. Secondary objectives included identifying most common culture types and organisms encountered and intervened on at our facility.

Quality Improvement Project

This quality improvement project was approved by the CVVAMC Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. Members of the medical review board signed a care coordination agreement between pharmacy and outpatient HCPs to permit pharmacist interventions involving optimization of antibiotic therapy. This agreement allowed pharmacists to make changes to existing antimicrobial regimens within their scope of practice (SOP) without requiring discussion with HCPs. A protocol was also developed to guide pharmacist modification of antimicrobial therapy based on current antimicrobial guidelines.7 This protocol was based on commonly isolated organisms and local resistance patterns and provided guidance for antibiotic treatment based on culture type (ie, skin and soft tissue infection, urine, etc). Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) note templates were also developed for interventions performed, and patient follow-up after antibiotic regimens were completed (eAppendix 1

Program Inclusion

Veterans were included in this project if they presented to primary care or urgent care clinics for therapy; had positive culture and sensitivity results; and were prescribed an empiric antibiotic. Veterans were not eligible for this project if they were not receiving antibiotic therapy, with or without pending or resulted culture results shown in CPRS.

Implementation

Data gathered through a CPRS dashboard from August 2019 to February 2020 identified patients with pending or completed culture results in urgent care and primary care settings (eAppendix 4). The dashboard was created specifically for this project to show patient details that included initial antibiotic(s) prescribed and preliminary and final culture results. After a mismatched combination was identified, pharmacists contacted patients and assessed symptoms. If a patient was still symptomatic, the pharmacist changed the antibiotic regimen and educated the patient about this change. The pharmacist documented an intervention note in CPRS and added the HCP as a signer so he or she would be aware of the change. The clinical pharmacist followed up after regimens were complete. At this time, the pharmacist assessed patients to ensure the medication was taken as directed (eg, number of days of therapy, how many tablets per day, etc), to discuss any reported adverse effects, and to assess resolution of symptoms. If a patient still had symptoms, the pharmacist contacted the patient’s primary care provider. If the veteran could not be contacted after 3 consecutive attempts via phone, a certified letter was mailed. If patients were asymptomatic at the time of the call, the pharmacist documented the lack of symptoms and added the HCP as a signer for awareness purposes. HCPs continued to practice as usual while this service was implemented.

Observations

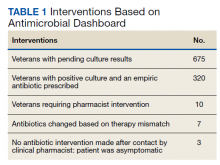

Using the culture and susceptibility dashboard, the pharmacist identified 675 patients as having a pending culture (Table 1). Among these patients, 320 results were positive, and were taking antibiotics empirically. Out of the 320 patients who met inclusion criteria, 10 required pharmacist intervention. After contacting the veterans, 7 required regimen changes because their current antibiotic was not susceptible to the isolated organism. Three additional patients were contacted because of a mismatch between the empiric antibiotic and culture result. Antibiotic therapy was not modified because these patients were asymptomatic at the time the clinical pharmacist contacted them. These patient cases were discussed with the HCP before documenting the intervention to prevent initiation of unwarranted antibiotics.

Most of the modified antimicrobial regimens were found in urine cultures from symptomatic patients (Table 2). Of the 7 patients requiring therapy change because of a mismatch antibiotic–bacteria combination, 4 were empirically prescribed fluoroquinolones, 2 received levofloxacin, and 2 were prescribed ciprofloxacin. According to the most recent antibiogram at our facility, some organisms are resistant to fluoroquinolones, specifically Proteus mirabilis (P mirabilis) and Escherichia coli (E coli). These pathogens were the cause of urinary tract infections in 3 of 4 patients with fluoroquinolone prescriptions.

Through the CPRS dashboard, the pharmacist inadvertently identified 4 patients with positive culture results who were not on antibiotic therapy. These patients were contacted by telephone, and antibiotics were initiated for symptomatic patients after consultation with the HCP. The primary culture type intervened on was urine in 12 of 14 cases (86%). The other 2 culture types included oropharynx culture (7%) positive for an acute bacterial respiratory tract infection caused by group C Streptococcus and a stool culture (7%) positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P aeruginosa). E coli (36%) was isolated in 5 cases and was the most commonly isolated organism. P

Discussion

This project was an innovative antimicrobial stewardship endeavor that helped initiate antibiotic interventions quickly and improve patient outcomes. The antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist independently performed interventions for patients without requiring HCP consultation, therefore decreasing HCP burden and possibly reducing time to assessment of culture results.

Limitations

The study results were limited due to its small sample size of antimicrobial interventions. The clinical pharmacist did not contact the patient when the antibiotic prescribed empirically by the HCP was appropriate for the isolated organism. Among the patients contacted, 3 were asymptomatic, did not require further antibiotic therapy, and no intervention was made. Provider education was deemed successful because HCPs did not request further information about the service. However, not all HCPs were provided education because of different shifts and inability to attend educational sessions. Closely working with lead physicians within the facility provided an alternate method for information dissemination.

The care coordination agreement allowed the pharmacist to make changes if patients had a current prescription for an antibiotic. In addition to the changes to antibiotics, this project improved HCP awareness of culture results even in cases of symptomatic patients who were not prescribed therapy. When this occurred, the pharmacist contacted the patient to assess symptoms and then notified the HCP if the patient was symptomatic.

Future Directions

Future endeavors regarding this project include modifying the scope of the service to allow pharmacists to prescribe antibiotics for patients with positive cultures and symptoms without empiric antibiotics in addition to continuing to modify empiric therapy. Additionally, improving dashboard efficiency through changes to include only isolated antibiotic mismatches rather than all antibiotics prescribed and all available cultures would reduce the pharmacists’ time commitment. Expanding to other parts of the medical center, including long-term care facilities and other outpatient clinics, would allow this service to reach more veterans. Integrating this service throughout the medical center will require continued HCP education and modifying care coordination agreements to include these facilities.

On a typical day, 60 to 90 minutes were spent navigating the dashboard and implementing this service. The CPRS dashboard should be modified to streamline patients identified to decrease the daily time commitment. Re-education of HCPs about resistance rates of fluoroquinolones and empirically prescribing these agents also will be completed based on empiric antibiotic interventions made with these agents throughout this project. Discussing HCP viewpoints on this service would be beneficial to ensure HCP satisfaction.

Conclusions

This pharmacy service and antimicrobial stewardship program reduced time patients were on inappropriate antibiotics. Pharmacists reviewed the dashboard daily under the scope of this project, which expedited needed changes and decreased provider burden because pharmacists were able to make changes without interrupting HCPs’ daily tasks, including patient care.

This program may also reduce readmissions. Patients who were still symptomatic were contacted could be given revised medication regimens without the patient returning to the facility for follow-up treatment. An interesting conclusion not included in the current scope of this service was possible reduced time to therapy initiation in cases of positive cultures and symptomatic patients without antibiotic therapy. If this occurred on the dashboard, patient’s symptoms could be assessed, and if symptoms were ongoing, the pharmacist contacted the HCP with a recommended antimicrobial therapy. In these cases, we were able to mail the antibiotic quickly, and many times, on the same day as this intervention through overnight mail. Implementation of a pharmacist-led antimicrobial review service has provided positive results overall for CVVAMC.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of the facilities at the Carl Vinson VA Medical Center.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic use in outpatient settings, 2017: progress and opportunities. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/outpatient.html

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html

3. Jonas OB, Irwin A, Berthe FCJ, Le Gall FG, Marquez PV. Drug-resistant infections: a threat to our economic future. March 2017. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/323311493396993758/final-report

4. Davis LC, Covey RB, Weston JS, Hu BBY, Laine GA. Pharmacist-driven antimicrobial optimization in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(5)(suppl 1):S49-S56. doi:10.2146/sp150036

5. Baker SN, Acquisto NM, Ashley ED, Fairbanks RJ, Beamish SE, Haas CE. Pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program for patients discharged from the emergency department. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25(2):190-194. doi:10.1177/0897190011420160

6 Randolph TC, Parker A, Meyer L, Zeina R. Effect of a pharmacist-managed culture review process on antimicrobial therapy in an emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(10):916-919. doi:10.2146/ajhp090552

7. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines 2019. Accessed August 24, 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/practice-guidelines/#/+/0/date_na_dt/desc

Increasing antibiotic resistance is an urgent threat to public health and establishing a review service for antibiotics could alleviate this problem. As use of antibiotics escalates, the risk of resistance becomes increasingly important. Each year, approximately 269 million antibiotics are dispensed and at least 30% are prescribed inappropriately.1 In addition to inappropriate prescribing, increased antibiotic resistance can be caused by patients not completing an antibiotic course as recommended or inherent bacterial mutations. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year approximately 3 million individuals contract an antibiotic-resistant infection.2 By 2050, it is projected that drug-resistant conditions could cause 300 million deaths and might be as disastrous to the economy as the 2008 global financial crisis.3 Ensuring appropriate use of antibiotic therapy through antimicrobial stewardship can help combat this significant public health issue.

Antimicrobial stewardship promotes appropriate use of antimicrobials to improve patient outcomes, reduce health care costs, and decrease antimicrobial resistance. One study found that nearly 50% of patients discharged from the emergency department with antibiotics required therapy modification after culture and susceptibility results were returned.4 Both the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) support incorporating a clinical pharmacist into culture reviews.3 Several institutions have implemented a pharmacist-led culture review service to improve antibiotic usage, which has shown positive results. A retrospective case-control study at University of Rochester Medical Center showed reduced time to positive culture review and to patient or health care provider (HCP) notification when emergency medicine pharmacists were involved in culture review.5 A retrospective study at Carolinas Medical Center-Northeast showed 12% decreased readmission rate using pharmacist-implemented culture review compared with HCP review.6 Results from previous studies showed an overall improvement in patient safety through decreased use of inappropriate agents and reduced time on inappropriate antibiotic therapy.

Establishing a pharmacist-led culture review service at the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center (CVVAMC) in Dublin, Georgia, could decrease the time to review of positive culture results, time to patient or HCP notification, and readmission rates. CVVAMC provides outpatient primary care services to about 30,000 veterans in the central and southern regions of Georgia. Our facility has executed an antimicrobial stewardship program based on guidelines published in 2016 by IDSA and SHEA to guide optimal use of antibiotics. Clinical pharmacists play an active role in antimicrobial stewardship throughout the facility. Clinical responsibilities of the antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist include assessing therapy for inappropriate dual anaerobic coverage, evaluating inpatient culture results within 48 hours, dosing and monitoring antibiotic therapy, including vancomycin and aminoglycosides, and implementing IV to by-mouth conversions for appropriate patients. HCPs involved with antimicrobial stewardship could order an array of tests to assess a veteran’s condition, including cultures, when an infection is suspected.

Culture results take about 3 to 5 days, then HCPs evaluate the result to ensure current antibiotic therapy is appropriate. Patients might not receive timely follow-up because HCPs often have many laboratory alerts to sift through every day, and a protocol is not in place for pharmacists to adjust outpatient antimicrobial regimens based on culture results. Before implementing this project, there was no outpatient service for pharmacists to impact culture and susceptibility review. This project was initiated because a lead physician identified difficulty reviewing culture and susceptibility results. HCPs often work on rotating schedules, and there was a concern about possible delay in follow-up of results if a HCP was not scheduled to work for a period of time.

The purpose of this project was to implement an outpatient, pharmacist-managed culture and susceptibility review service to improve patient outcomes, including decreasing and preventing inappropriate antibiotic use. The primary objective was to design and implement a pharmacist-led review service to intervene in cases of mismatched antibiotic bacteria combinations. Secondary objectives included identifying most common culture types and organisms encountered and intervened on at our facility.

Quality Improvement Project

This quality improvement project was approved by the CVVAMC Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. Members of the medical review board signed a care coordination agreement between pharmacy and outpatient HCPs to permit pharmacist interventions involving optimization of antibiotic therapy. This agreement allowed pharmacists to make changes to existing antimicrobial regimens within their scope of practice (SOP) without requiring discussion with HCPs. A protocol was also developed to guide pharmacist modification of antimicrobial therapy based on current antimicrobial guidelines.7 This protocol was based on commonly isolated organisms and local resistance patterns and provided guidance for antibiotic treatment based on culture type (ie, skin and soft tissue infection, urine, etc). Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) note templates were also developed for interventions performed, and patient follow-up after antibiotic regimens were completed (eAppendix 1

Program Inclusion

Veterans were included in this project if they presented to primary care or urgent care clinics for therapy; had positive culture and sensitivity results; and were prescribed an empiric antibiotic. Veterans were not eligible for this project if they were not receiving antibiotic therapy, with or without pending or resulted culture results shown in CPRS.

Implementation

Data gathered through a CPRS dashboard from August 2019 to February 2020 identified patients with pending or completed culture results in urgent care and primary care settings (eAppendix 4). The dashboard was created specifically for this project to show patient details that included initial antibiotic(s) prescribed and preliminary and final culture results. After a mismatched combination was identified, pharmacists contacted patients and assessed symptoms. If a patient was still symptomatic, the pharmacist changed the antibiotic regimen and educated the patient about this change. The pharmacist documented an intervention note in CPRS and added the HCP as a signer so he or she would be aware of the change. The clinical pharmacist followed up after regimens were complete. At this time, the pharmacist assessed patients to ensure the medication was taken as directed (eg, number of days of therapy, how many tablets per day, etc), to discuss any reported adverse effects, and to assess resolution of symptoms. If a patient still had symptoms, the pharmacist contacted the patient’s primary care provider. If the veteran could not be contacted after 3 consecutive attempts via phone, a certified letter was mailed. If patients were asymptomatic at the time of the call, the pharmacist documented the lack of symptoms and added the HCP as a signer for awareness purposes. HCPs continued to practice as usual while this service was implemented.

Observations

Using the culture and susceptibility dashboard, the pharmacist identified 675 patients as having a pending culture (Table 1). Among these patients, 320 results were positive, and were taking antibiotics empirically. Out of the 320 patients who met inclusion criteria, 10 required pharmacist intervention. After contacting the veterans, 7 required regimen changes because their current antibiotic was not susceptible to the isolated organism. Three additional patients were contacted because of a mismatch between the empiric antibiotic and culture result. Antibiotic therapy was not modified because these patients were asymptomatic at the time the clinical pharmacist contacted them. These patient cases were discussed with the HCP before documenting the intervention to prevent initiation of unwarranted antibiotics.

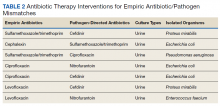

Most of the modified antimicrobial regimens were found in urine cultures from symptomatic patients (Table 2). Of the 7 patients requiring therapy change because of a mismatch antibiotic–bacteria combination, 4 were empirically prescribed fluoroquinolones, 2 received levofloxacin, and 2 were prescribed ciprofloxacin. According to the most recent antibiogram at our facility, some organisms are resistant to fluoroquinolones, specifically Proteus mirabilis (P mirabilis) and Escherichia coli (E coli). These pathogens were the cause of urinary tract infections in 3 of 4 patients with fluoroquinolone prescriptions.

Through the CPRS dashboard, the pharmacist inadvertently identified 4 patients with positive culture results who were not on antibiotic therapy. These patients were contacted by telephone, and antibiotics were initiated for symptomatic patients after consultation with the HCP. The primary culture type intervened on was urine in 12 of 14 cases (86%). The other 2 culture types included oropharynx culture (7%) positive for an acute bacterial respiratory tract infection caused by group C Streptococcus and a stool culture (7%) positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P aeruginosa). E coli (36%) was isolated in 5 cases and was the most commonly isolated organism. P

Discussion

This project was an innovative antimicrobial stewardship endeavor that helped initiate antibiotic interventions quickly and improve patient outcomes. The antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist independently performed interventions for patients without requiring HCP consultation, therefore decreasing HCP burden and possibly reducing time to assessment of culture results.

Limitations

The study results were limited due to its small sample size of antimicrobial interventions. The clinical pharmacist did not contact the patient when the antibiotic prescribed empirically by the HCP was appropriate for the isolated organism. Among the patients contacted, 3 were asymptomatic, did not require further antibiotic therapy, and no intervention was made. Provider education was deemed successful because HCPs did not request further information about the service. However, not all HCPs were provided education because of different shifts and inability to attend educational sessions. Closely working with lead physicians within the facility provided an alternate method for information dissemination.

The care coordination agreement allowed the pharmacist to make changes if patients had a current prescription for an antibiotic. In addition to the changes to antibiotics, this project improved HCP awareness of culture results even in cases of symptomatic patients who were not prescribed therapy. When this occurred, the pharmacist contacted the patient to assess symptoms and then notified the HCP if the patient was symptomatic.

Future Directions

Future endeavors regarding this project include modifying the scope of the service to allow pharmacists to prescribe antibiotics for patients with positive cultures and symptoms without empiric antibiotics in addition to continuing to modify empiric therapy. Additionally, improving dashboard efficiency through changes to include only isolated antibiotic mismatches rather than all antibiotics prescribed and all available cultures would reduce the pharmacists’ time commitment. Expanding to other parts of the medical center, including long-term care facilities and other outpatient clinics, would allow this service to reach more veterans. Integrating this service throughout the medical center will require continued HCP education and modifying care coordination agreements to include these facilities.

On a typical day, 60 to 90 minutes were spent navigating the dashboard and implementing this service. The CPRS dashboard should be modified to streamline patients identified to decrease the daily time commitment. Re-education of HCPs about resistance rates of fluoroquinolones and empirically prescribing these agents also will be completed based on empiric antibiotic interventions made with these agents throughout this project. Discussing HCP viewpoints on this service would be beneficial to ensure HCP satisfaction.

Conclusions

This pharmacy service and antimicrobial stewardship program reduced time patients were on inappropriate antibiotics. Pharmacists reviewed the dashboard daily under the scope of this project, which expedited needed changes and decreased provider burden because pharmacists were able to make changes without interrupting HCPs’ daily tasks, including patient care.

This program may also reduce readmissions. Patients who were still symptomatic were contacted could be given revised medication regimens without the patient returning to the facility for follow-up treatment. An interesting conclusion not included in the current scope of this service was possible reduced time to therapy initiation in cases of positive cultures and symptomatic patients without antibiotic therapy. If this occurred on the dashboard, patient’s symptoms could be assessed, and if symptoms were ongoing, the pharmacist contacted the HCP with a recommended antimicrobial therapy. In these cases, we were able to mail the antibiotic quickly, and many times, on the same day as this intervention through overnight mail. Implementation of a pharmacist-led antimicrobial review service has provided positive results overall for CVVAMC.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of the facilities at the Carl Vinson VA Medical Center.

Increasing antibiotic resistance is an urgent threat to public health and establishing a review service for antibiotics could alleviate this problem. As use of antibiotics escalates, the risk of resistance becomes increasingly important. Each year, approximately 269 million antibiotics are dispensed and at least 30% are prescribed inappropriately.1 In addition to inappropriate prescribing, increased antibiotic resistance can be caused by patients not completing an antibiotic course as recommended or inherent bacterial mutations. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year approximately 3 million individuals contract an antibiotic-resistant infection.2 By 2050, it is projected that drug-resistant conditions could cause 300 million deaths and might be as disastrous to the economy as the 2008 global financial crisis.3 Ensuring appropriate use of antibiotic therapy through antimicrobial stewardship can help combat this significant public health issue.

Antimicrobial stewardship promotes appropriate use of antimicrobials to improve patient outcomes, reduce health care costs, and decrease antimicrobial resistance. One study found that nearly 50% of patients discharged from the emergency department with antibiotics required therapy modification after culture and susceptibility results were returned.4 Both the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) support incorporating a clinical pharmacist into culture reviews.3 Several institutions have implemented a pharmacist-led culture review service to improve antibiotic usage, which has shown positive results. A retrospective case-control study at University of Rochester Medical Center showed reduced time to positive culture review and to patient or health care provider (HCP) notification when emergency medicine pharmacists were involved in culture review.5 A retrospective study at Carolinas Medical Center-Northeast showed 12% decreased readmission rate using pharmacist-implemented culture review compared with HCP review.6 Results from previous studies showed an overall improvement in patient safety through decreased use of inappropriate agents and reduced time on inappropriate antibiotic therapy.

Establishing a pharmacist-led culture review service at the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center (CVVAMC) in Dublin, Georgia, could decrease the time to review of positive culture results, time to patient or HCP notification, and readmission rates. CVVAMC provides outpatient primary care services to about 30,000 veterans in the central and southern regions of Georgia. Our facility has executed an antimicrobial stewardship program based on guidelines published in 2016 by IDSA and SHEA to guide optimal use of antibiotics. Clinical pharmacists play an active role in antimicrobial stewardship throughout the facility. Clinical responsibilities of the antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist include assessing therapy for inappropriate dual anaerobic coverage, evaluating inpatient culture results within 48 hours, dosing and monitoring antibiotic therapy, including vancomycin and aminoglycosides, and implementing IV to by-mouth conversions for appropriate patients. HCPs involved with antimicrobial stewardship could order an array of tests to assess a veteran’s condition, including cultures, when an infection is suspected.

Culture results take about 3 to 5 days, then HCPs evaluate the result to ensure current antibiotic therapy is appropriate. Patients might not receive timely follow-up because HCPs often have many laboratory alerts to sift through every day, and a protocol is not in place for pharmacists to adjust outpatient antimicrobial regimens based on culture results. Before implementing this project, there was no outpatient service for pharmacists to impact culture and susceptibility review. This project was initiated because a lead physician identified difficulty reviewing culture and susceptibility results. HCPs often work on rotating schedules, and there was a concern about possible delay in follow-up of results if a HCP was not scheduled to work for a period of time.

The purpose of this project was to implement an outpatient, pharmacist-managed culture and susceptibility review service to improve patient outcomes, including decreasing and preventing inappropriate antibiotic use. The primary objective was to design and implement a pharmacist-led review service to intervene in cases of mismatched antibiotic bacteria combinations. Secondary objectives included identifying most common culture types and organisms encountered and intervened on at our facility.

Quality Improvement Project

This quality improvement project was approved by the CVVAMC Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. Members of the medical review board signed a care coordination agreement between pharmacy and outpatient HCPs to permit pharmacist interventions involving optimization of antibiotic therapy. This agreement allowed pharmacists to make changes to existing antimicrobial regimens within their scope of practice (SOP) without requiring discussion with HCPs. A protocol was also developed to guide pharmacist modification of antimicrobial therapy based on current antimicrobial guidelines.7 This protocol was based on commonly isolated organisms and local resistance patterns and provided guidance for antibiotic treatment based on culture type (ie, skin and soft tissue infection, urine, etc). Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) note templates were also developed for interventions performed, and patient follow-up after antibiotic regimens were completed (eAppendix 1

Program Inclusion

Veterans were included in this project if they presented to primary care or urgent care clinics for therapy; had positive culture and sensitivity results; and were prescribed an empiric antibiotic. Veterans were not eligible for this project if they were not receiving antibiotic therapy, with or without pending or resulted culture results shown in CPRS.

Implementation

Data gathered through a CPRS dashboard from August 2019 to February 2020 identified patients with pending or completed culture results in urgent care and primary care settings (eAppendix 4). The dashboard was created specifically for this project to show patient details that included initial antibiotic(s) prescribed and preliminary and final culture results. After a mismatched combination was identified, pharmacists contacted patients and assessed symptoms. If a patient was still symptomatic, the pharmacist changed the antibiotic regimen and educated the patient about this change. The pharmacist documented an intervention note in CPRS and added the HCP as a signer so he or she would be aware of the change. The clinical pharmacist followed up after regimens were complete. At this time, the pharmacist assessed patients to ensure the medication was taken as directed (eg, number of days of therapy, how many tablets per day, etc), to discuss any reported adverse effects, and to assess resolution of symptoms. If a patient still had symptoms, the pharmacist contacted the patient’s primary care provider. If the veteran could not be contacted after 3 consecutive attempts via phone, a certified letter was mailed. If patients were asymptomatic at the time of the call, the pharmacist documented the lack of symptoms and added the HCP as a signer for awareness purposes. HCPs continued to practice as usual while this service was implemented.

Observations

Using the culture and susceptibility dashboard, the pharmacist identified 675 patients as having a pending culture (Table 1). Among these patients, 320 results were positive, and were taking antibiotics empirically. Out of the 320 patients who met inclusion criteria, 10 required pharmacist intervention. After contacting the veterans, 7 required regimen changes because their current antibiotic was not susceptible to the isolated organism. Three additional patients were contacted because of a mismatch between the empiric antibiotic and culture result. Antibiotic therapy was not modified because these patients were asymptomatic at the time the clinical pharmacist contacted them. These patient cases were discussed with the HCP before documenting the intervention to prevent initiation of unwarranted antibiotics.

Most of the modified antimicrobial regimens were found in urine cultures from symptomatic patients (Table 2). Of the 7 patients requiring therapy change because of a mismatch antibiotic–bacteria combination, 4 were empirically prescribed fluoroquinolones, 2 received levofloxacin, and 2 were prescribed ciprofloxacin. According to the most recent antibiogram at our facility, some organisms are resistant to fluoroquinolones, specifically Proteus mirabilis (P mirabilis) and Escherichia coli (E coli). These pathogens were the cause of urinary tract infections in 3 of 4 patients with fluoroquinolone prescriptions.

Through the CPRS dashboard, the pharmacist inadvertently identified 4 patients with positive culture results who were not on antibiotic therapy. These patients were contacted by telephone, and antibiotics were initiated for symptomatic patients after consultation with the HCP. The primary culture type intervened on was urine in 12 of 14 cases (86%). The other 2 culture types included oropharynx culture (7%) positive for an acute bacterial respiratory tract infection caused by group C Streptococcus and a stool culture (7%) positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P aeruginosa). E coli (36%) was isolated in 5 cases and was the most commonly isolated organism. P

Discussion

This project was an innovative antimicrobial stewardship endeavor that helped initiate antibiotic interventions quickly and improve patient outcomes. The antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist independently performed interventions for patients without requiring HCP consultation, therefore decreasing HCP burden and possibly reducing time to assessment of culture results.

Limitations

The study results were limited due to its small sample size of antimicrobial interventions. The clinical pharmacist did not contact the patient when the antibiotic prescribed empirically by the HCP was appropriate for the isolated organism. Among the patients contacted, 3 were asymptomatic, did not require further antibiotic therapy, and no intervention was made. Provider education was deemed successful because HCPs did not request further information about the service. However, not all HCPs were provided education because of different shifts and inability to attend educational sessions. Closely working with lead physicians within the facility provided an alternate method for information dissemination.

The care coordination agreement allowed the pharmacist to make changes if patients had a current prescription for an antibiotic. In addition to the changes to antibiotics, this project improved HCP awareness of culture results even in cases of symptomatic patients who were not prescribed therapy. When this occurred, the pharmacist contacted the patient to assess symptoms and then notified the HCP if the patient was symptomatic.

Future Directions

Future endeavors regarding this project include modifying the scope of the service to allow pharmacists to prescribe antibiotics for patients with positive cultures and symptoms without empiric antibiotics in addition to continuing to modify empiric therapy. Additionally, improving dashboard efficiency through changes to include only isolated antibiotic mismatches rather than all antibiotics prescribed and all available cultures would reduce the pharmacists’ time commitment. Expanding to other parts of the medical center, including long-term care facilities and other outpatient clinics, would allow this service to reach more veterans. Integrating this service throughout the medical center will require continued HCP education and modifying care coordination agreements to include these facilities.

On a typical day, 60 to 90 minutes were spent navigating the dashboard and implementing this service. The CPRS dashboard should be modified to streamline patients identified to decrease the daily time commitment. Re-education of HCPs about resistance rates of fluoroquinolones and empirically prescribing these agents also will be completed based on empiric antibiotic interventions made with these agents throughout this project. Discussing HCP viewpoints on this service would be beneficial to ensure HCP satisfaction.

Conclusions

This pharmacy service and antimicrobial stewardship program reduced time patients were on inappropriate antibiotics. Pharmacists reviewed the dashboard daily under the scope of this project, which expedited needed changes and decreased provider burden because pharmacists were able to make changes without interrupting HCPs’ daily tasks, including patient care.

This program may also reduce readmissions. Patients who were still symptomatic were contacted could be given revised medication regimens without the patient returning to the facility for follow-up treatment. An interesting conclusion not included in the current scope of this service was possible reduced time to therapy initiation in cases of positive cultures and symptomatic patients without antibiotic therapy. If this occurred on the dashboard, patient’s symptoms could be assessed, and if symptoms were ongoing, the pharmacist contacted the HCP with a recommended antimicrobial therapy. In these cases, we were able to mail the antibiotic quickly, and many times, on the same day as this intervention through overnight mail. Implementation of a pharmacist-led antimicrobial review service has provided positive results overall for CVVAMC.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of the facilities at the Carl Vinson VA Medical Center.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic use in outpatient settings, 2017: progress and opportunities. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/outpatient.html

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html

3. Jonas OB, Irwin A, Berthe FCJ, Le Gall FG, Marquez PV. Drug-resistant infections: a threat to our economic future. March 2017. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/323311493396993758/final-report

4. Davis LC, Covey RB, Weston JS, Hu BBY, Laine GA. Pharmacist-driven antimicrobial optimization in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(5)(suppl 1):S49-S56. doi:10.2146/sp150036

5. Baker SN, Acquisto NM, Ashley ED, Fairbanks RJ, Beamish SE, Haas CE. Pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program for patients discharged from the emergency department. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25(2):190-194. doi:10.1177/0897190011420160

6 Randolph TC, Parker A, Meyer L, Zeina R. Effect of a pharmacist-managed culture review process on antimicrobial therapy in an emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(10):916-919. doi:10.2146/ajhp090552

7. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines 2019. Accessed August 24, 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/practice-guidelines/#/+/0/date_na_dt/desc

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic use in outpatient settings, 2017: progress and opportunities. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/outpatient.html

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html

3. Jonas OB, Irwin A, Berthe FCJ, Le Gall FG, Marquez PV. Drug-resistant infections: a threat to our economic future. March 2017. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/323311493396993758/final-report

4. Davis LC, Covey RB, Weston JS, Hu BBY, Laine GA. Pharmacist-driven antimicrobial optimization in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(5)(suppl 1):S49-S56. doi:10.2146/sp150036

5. Baker SN, Acquisto NM, Ashley ED, Fairbanks RJ, Beamish SE, Haas CE. Pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program for patients discharged from the emergency department. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25(2):190-194. doi:10.1177/0897190011420160

6 Randolph TC, Parker A, Meyer L, Zeina R. Effect of a pharmacist-managed culture review process on antimicrobial therapy in an emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(10):916-919. doi:10.2146/ajhp090552

7. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines 2019. Accessed August 24, 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/practice-guidelines/#/+/0/date_na_dt/desc

The Expansion of Associated Health Training in the VA

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest health care delivery system in the United States, comprising 1293 sites of care, including 171 medical centers.1 One of the 4 statutory missions of the VA is to train health care professionals (HCPs) to meet the needs of the VA and the nation.2 Through partnerships with more than 1800 accredited colleges, universities, and training programs, the VA provides training annually to nearly 118,000 health professions trainees (HPTs) across a variety of health care professions, and all of whom provide direct clinical care to veterans.3

In the VA, the Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) is charged with overseeing health professions training and the VA’s partnership with medical and associated health (AH) professions schools, which was first codified in Policy Memorandum No. 2 in 1946.4,5 Given the scope and breadth of health professions education offered through the VA, OAA is in a unique position to address health care shortage areas as well as influence the educational standards for certain professions.

Many of these health care professions fall under the rubric of AH, which include mental health (MH) specialties, rehabilitative specialties, and others. These professions are critical to address in the expanding world of health care in the United States with its increased specialization and emphasis on coordination of care with interprofessional teams. During the 2019/2020 academic year, the VA provided clinical training to approximately 21,000 AH HPTs from > 40 professions with just over 20% receiving financial support through the OAA. Of the HPTs who train at VA without compensation, most spend shorter amounts of time in clinical rotations in the VA, are in pregraduate-degree education programs where payment for clinical rotations is not expected and may not be eligible for hire immediately on completion of their clinical training experience. The 17 funded professions have been strategically selected by the OAA to ensure a robust pipeline of HCPs to meet the needs of veterans and the nation.

To meet the demands of AH professionals (AHPs), the OAA implemented targeted expansion over the past 10 years. While not exhaustive, this paper describes several expansion efforts based on VA special initiatives, including enhancing clinical access in rural settings and shifting toward postgraduate-degree training and specialization. By aligning expansion with VA priorities as well as trends in health care more broadly, the OAA can ensure that there is a supply of well-trained AHPs who have developed the requisite competencies to contribute to our nation’s health care needs. Further, expansion can help train and recruit health professionals who can be hired into VA positions ready to care for the complex needs of veterans.

Associated Health Professionals

Overseen by the OAA, AH expansion is designed to address the specific needs of the VA and the US health care system. Data from the VA Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) shows that the VA employment of AHPs has grown from 87,351 AHPs hired in fiscal year (FY) 2010 to 119,120 as of April 2020. This represents an average yearly growth rate of 3.4% and a total growth rate of 36%. The Bureau of Labor Statistics predictions for 2019/2029 suggest that certain AHPs are expected to have a 10-year growth rates of 20% or more to meet the changing health care needs of patients especially as the population ages; the growth rates for many AHPs far surpasses that of physicians, which is anticipated to be 4% (Table).6,7 The VA WMC expects an additional 52,283 AHPs will be hired by the VA by FY 2030 based on the 10-year average growth rate (Kali Clark, Veterans Health Administration Workforce Management and Consulting Office, email communication, May 28, 2020).

One of the driving forces behind the growth rate is the move toward using AHPs to supplement health care for a variety of health conditions.8,9 Examples include the integration of rehabilitation professionals, alternative care professionals (eg, massage therapists, practitioners who offer training in yoga and meditation), chiropractors, MH professionals, and pharmacists in the treatment of chronic pain, the use of a wider range of professionals in the treatment of MH conditions, and the integration of MH professionals into traditional medical settings, such as primary care. This intentional move to a more well-integrated model of interprofessional care is apparent in many other health care systems throughout the United States. Within the VA, this shift may be most evident through the introduction of the Whole Health model of care. The Whole Health model of care uses an interprofessional team to assess and care for veterans, using a personalized health plan addressing medical and MH conditions as well as behavioral, social, or spiritual concerns.10 The Whole Health model of care provides veterans with access to a variety of health care services, including but not limited to MH services, spiritual interventions, exercise-based programs, yoga, meditation, and nutrition counseling.

The OAA and AH education division have focused expansion to meet the increased need for MH and rehabilitation providers, to enhance interprofessional education, and to emphasize postgraduate-degree clinical training. This focus reflects the trends seen in health care training broadly throughout the nation and the intentional pivot is a model of these trends and a model for how to intentionally address these trends. Specific to the VA, focused expansion plans have allowed OAA to address VA strategic initiatives such as pain management and caring for rural veterans.

Funded Training Positions

As a result of recent AH expansion efforts, there has been a 33% increase in stipend-funded positions during the past 10 years, a rate that directly corresponds with the growth of AHPs in the VA. Recent AH expansion efforts can contribute to a particularly positive impact in highly rural and underserved areas where recruiting providers remains challenging.

The OAA launched the Mental Health Education Expansion (MHEE) initiative in 2012, which has now added 782 funded training slots across 10 health professions, 8 of which are psychology, pharmacy, chaplaincy, professional MH counseling, marriage and family therapy (MFT), social work (SW), occupational therapy (OT), and physician assistant (PA). Through the MHEE initiative, the VA has established funded internships for licensed professional mental health counselors and marriage and family therapists, as these professions are targeted for expanding the overall MH workforce in the VA. The OAA currently funds more than 50 total HPT positions for these 2 professions with an aim of increasing their recruitment to the VA MH workforce over the next decade. The MHEE is aligned with specified VA priorities to train a future VA workforce prepared for interprofessional collaboration and clinical care in an increasingly integrated and complex environment. This expansion effort also aligns with an increasing understanding of the importance of addressing the MH needs of our nation by ensuring there is an adequate supply of competent, well-trained clinicians entering the workforce.

The OAA has created and expanded residencies and fellowships in multiple rehabilitation professions, including chiropractic, physical therapy (PT), and OT. With the increased focus on the management of chronic pain in the nation combined with a specific emphasis on this clinical need in the VA, chiropractors have been deemed essential HCPs. In 2014, the VA established 5 chiropractic residency programs while partnering with the Council on Chiropractic Education to develop accreditation standards for residency training. OAA’s efforts have yielded 5 accredited residency programs, the first in the United States. In 2020, the VA doubled the number of available chiropractic residency programs, and future expansion is anticipated. Since 2010, PT residencies have expanded from 1 to 28 programs (42 funded positions) across 4 board certification specialties: cardiovascular-pulmonary, geriatric, neurologic, and orthopedic. Similarly, the VA was one of the first organizations to achieve accreditation for OT fellowships; there are currently 5 accredited OT fellowship programs across 3 areas of practice: assistive technology, MH, and physical rehabilitation. The VA OT fellowship program focused on assistive technology is the only program in the United States at this time.

Interprofessional Education

As one of the primary focus areas for AH expansion, interprofessional education (IPE) has been recognized as increasingly important for the provision of health care and the development of HPT programs. IPE can develop professionals who appreciate the roles of diverse professions and can use teamwork to enhance clinical outcomes for patients.11 There also are a growing number of professional organizations supporting the Interprofessional Education Collaborative with many representing AHPs.12 Collaboration across HCPs is an important way of reducing health care costs by enhancing clinical outcomes, communication, and teamwork.13-16 The VA and the nation’s health care system benefit from the by-products of interprofessional collaboration through investment in targeted training programs. In each phase of the AH expansion, special consideration was given to applicant programs offering unique and innovative clinical and educational experiences consistent with the promotion of interprofessional care. In doing so, increased numbers of AH HPTs have engaged in team-based clinical care.

Pain Management Pharmacy

The efforts of AH to align expansion with high-priority agency-wide efforts has resulted in the growth of pharmacy residency positions focused on pain management. Pharmacy postgraduate year (PGY) 2 residencies focusing on opioid reduction are an example of VA efforts to improve response to managing chronic pain and the long-term risks from opioid use during this national public health crisis.17 These residency programs focus on strategies to reduce the use of opioid medications in the clinical setting and teaching effective clinical interventions for reducing the rates of opioid addiction in veterans while still recognizing the need to identify and treat chronic pain. Before expansion efforts in 2018, there were 6 pharmacy residency programs focused on opioid use reduction in the VA, 8 pharmacy PGY2 residency positions were added in academic year 2019/2020, an additional 5 positions are being added in academic year 2021/2022 with the explicit goal of managing patients with high-risk chronic pain.

Rural Health

The lack of MH providers in rural areas has received much attention and is particularly important in the VA because veterans are more likely to live in less populated areas.18 The VA mandate to address this population was codified by the creation of the Office of Rural Health in 2006 via 38 USC § 7308.19Creating health professions training programs in rural settings provides HPTs the opportunity to learn professional competencies and train with faculty knowledgeable about this population—all of which provide a comprehensive training experience and serve as a recruitment pathway to hire HPTs into staff positions at these sites.19

When MHEE was initiated, not all regions of the country had funded VA psychology training programs, and this geographic gap in psychology training was a contributing factor to recruitment difficulties for psychologists in rural areas. As a result, the request for proposal process in the OAA highlighted and incentivized rurality when considering funding for new training programs. The OAA defined rurality as the number of patients served by the proposed health care facility who lived in a rural or highly rural zip code according to VA Support Service Center Capital Assets data.20 As a result, VA psychology doctoral internships expanded to be available in all states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. MH training programs were started in the highly rural states of Montana and Wyoming. These expansion efforts promise to be an essential component to addressing the gaps in coverage in rural settings as noted in recent research.21

Pregraduate to Postgraduate Programs

The OAA AH education division supports a significant number of pregraduate-degree and postgraduate-degree training. Some professions, such as psychology, pharmacy, SW, PT, speech pathology, OT, and nutrition/dietetics receive funding at both levels of training. More recent, the OAA has started to move funding from pregraduate to postgraduate-degree positions, specifically within professions where pregraduate funding is uncommon for both federal and nonfederal training positions. The effort is designed to better align stipend-paid training programs with the VA Professional Qualification Standards and the final level of training required for employment in the VA.22This means that HPTs receive stipend support during the highest level of their clinical training before degree conferral, eligibility for VA employment, or while participating in a postgraduate-degree residency or fellowship.

Additionally, this shift in focus and the resulting internal assessment of professions has allowed the OAA to fund more specialized training opportunities, which sometimes go beyond what is required by accrediting bodies or for recruitment into VA positions. For example, the OAA is supporting SW fellowship programs and PA residency positions to allow for greater specialization within these professions; the accrediting agencies for both professions have recently finalized their accreditation standards, and the OAA played a role in moving these standards forward.

While postgraduate residencies and fellowships are not required for all AH HPTs or for employment in the VA, there is a shift in some professions to encourage postgraduate training in advanced competencies in specialized areas. Participation in a residency or fellowship training program affords HPTs additional time and diverse clinical experiences to acquire clinical skills, all while under the supervision of a highly trained practitioner. This additional training also allows for a longitudinal assessment of the HPT to ensure an alignment of the HPTs’ knowledge, abilities, and skills with the expectation should they pursue VA employment.

In academic year 2019/2020, the OAA AH education division in conjunction with the PA national program office transitioned the entirety of the PA pregraduate-degree student positions (415 funded positions) to residency positions, increasing residency positions from 19 to 32 funded positions. This shift in emphasis for funding did not negatively impact the total number of pregraduate PA students receiving training in the VA and has created a pipeline of residency graduates who are ready to enter VA staff positions. To date, the VA has 14 PA residency programs across 3 specialties: emergency medicine (EM), MH, and primary care/geriatrics. Of these tracks, the VA offers 5 EM and 4 MH residencies that position graduates to be eligible for specialty certification. The National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants established Certificates of Added Qualifications (CAQ) to recognize and document specialty knowledge, skills, and experience. The VA MH residency programs have been established to align with the CAQ expectations, and residents immediately qualify to take the CAQ examination after the completion of training.

Currently, the same process to move pregraduate to postgraduate funding is being implemented for PT and OT. Within the PT profession, there is increased momentum toward residency and fellowship training programs to respond to the changing complexity of the health care systemand reduce the need of complex care to be provided by non-VA providers in the community.23 Both PT and OT have entered the initial phases of transitioning to residency or fellowship-funded positions. The OAA is partnering with these professions to move positions to postgraduate degree within the next 3 years with a commensurate increase in funding. The initial data indicate that 80% of graduated VA PT residents are board-certification eligible, and 89% of those who are eligible passed the examination on their first attempt.

Since 2013, the VA psychology training also has realized a growth in postgraduate-degree residencies. Psychology residency positions have increased 99% to 453 funded positions. This growth represents increased specialization in neuropsychology, geropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and health psychology. Additionally, postgraduate residencies meet most jurisdictional requirements for postdoctoral supervised experience and better prepare HPTs to enter specialty staff positions that are necessary to care for aging veterans.

Additional professions are being targeted for postgraduate-degree training programs, including dietetics and speech pathology, to align with upcoming changes in the qualification standards for employment. While the process to transition positions to postgraduate-degree training programs can take 3 to 5 years, the outcomes are expected to result in better prepared HPTs who can fill staff vacancies in the VA.

Conclusions

Through its funding and oversight of numerous professions, the OAA is uniquely situated to adapt its portfolio to meet the needs of the VA and the nation. Over the past 10 years, the OAA has expanded its total number of HPT positions to enhance interprofessional care, respond to the VA’s strategic initiatives, address the care needs of rural veterans, and shift positions to postgraduate training programs. The OAA’s investment in high-quality training programs builds a strong health care workforce ready to meet the needs of an increasingly complex and integrated health care environment.

The OAA anticipates future expansion, especially related to promoting rural training opportunities and shifting to postgraduate training programs as a means of promoting advanced health care and health system competencies while continuing to align with workforce projections. Furthermore, while there are data on the percentage of VA staff who participated in OAA training program through the VA All Employee Survey (AES), the range for AH professions is wide. For example, about 37% of rehabilitative staff reported participating in an OAA training program, and 72% of VA psychologists reported having an OAA training experience. To maximize the hiring of HPTs, OAA will continue its partnership with WMC to enact programs aimed at streamlining the hiring process so that veterans have access to HCPs who are specifically trained to work with them.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Providing health care for veterans. Updated April 23, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veterans’ Benefits. 38 USC §7301 and §7302 (1991). Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2018-title38/pdf/USCODE-2018-title38-partV-chap73-subchapI-sec7302.pdf

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Health professions education: academic year 2019-2020. Published 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics_2020.pdf

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VHA Office of Academic Affiliations. VA Policy Memorandum # 2. Policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. Published January 30, 1946. Accessed October 13, 2020. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Mission of the office of academic affiliations. Updated September 24, 2019. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.va.gov/oaa/oaa_mission.asp

6. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Office of Occupational Statistics and Employment Projections Occupational Outlook Handbook. Healthcare occupations. Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home.htm

7. Windmill IM, Freeman BA. Demand for audiology services: 30-yr projections and impact on academic programs. J Am Acad Audiol. 2013;24(5):407-416. doi:10.3766/jaaa.24.5.7

8. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce. HRSA health workforce: behavioral health workforce projections, 2017-2030. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/bh-workforce-projections-fact-sheet.pdf

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data brief, No. 325. Use of yoga, meditation, and chiropractors among US adults aged 18 and over. Published November 2018. Accessed September 24, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db325-h.pdf

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration Whole Health. Updated July 6, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

11. Clark KM. Interprofessional education: making our way out of the silos. Respir Care. 2018;63(5): 637-639. doi:10.4187/respcare.06234

12. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. What is interprofessional education (IPE)? Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/about-us

13. Nester J. The importance of interprofessional practice and education in the era of accountable care. N C Med J. 2016;77(2):128-132. doi.10.18043/ncm.77.2.128

14.. Hardin L, Kilian A, Murphy E. Bundled payments for care improvement: preparing for the medical diagnosis-related groups. J Nurs Adm. 2017;47(6): 313-319. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000492

15. Guraya SY, Barr H. The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34(2):125-184. doi:10.1016/j.kjms.2017.12.009

16. Ateah CA, Snow W, Wenter P, et al. Stereotyping as a barrier to collaboration: does interprofessional education make a difference? Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(2):208-213. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.004

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Managing Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. Published May 7, 1991. Updated February 2017. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. VHA office of rural health. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov19. Curran V, Rourke J. The role of medical education in the recruitment and retention of rural physicians. Med Teach. 2004;26(3):265-272. doi:10.1080/0142159042000192055

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Support Service Center Capital Assets. Updated December 1, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.data.va.gov/dataset/VHA-Support-Service-Center-Capital-Assets-VSSC-/2fr5-sktm

21. Domino ME, Lin CC, Morrisey JP, et al. Training psychologists for rural practice: exploring opportunities and constraints. J Rural Health. 2019;35(1):35-41. doi:10.1111/jrh.12299

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Directive 5005: Staffing. Published March 4, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vapubs/viewPublication.asp?Pub_ID=1140&FType=2

23. Furze JA, Freeman BA. Physical therapy and fellowship education: reflections on the past, present, and future. Phys Ther. 2016;96(7):949-960. doi:10.2522/ptj.20150473

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest health care delivery system in the United States, comprising 1293 sites of care, including 171 medical centers.1 One of the 4 statutory missions of the VA is to train health care professionals (HCPs) to meet the needs of the VA and the nation.2 Through partnerships with more than 1800 accredited colleges, universities, and training programs, the VA provides training annually to nearly 118,000 health professions trainees (HPTs) across a variety of health care professions, and all of whom provide direct clinical care to veterans.3

In the VA, the Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) is charged with overseeing health professions training and the VA’s partnership with medical and associated health (AH) professions schools, which was first codified in Policy Memorandum No. 2 in 1946.4,5 Given the scope and breadth of health professions education offered through the VA, OAA is in a unique position to address health care shortage areas as well as influence the educational standards for certain professions.

Many of these health care professions fall under the rubric of AH, which include mental health (MH) specialties, rehabilitative specialties, and others. These professions are critical to address in the expanding world of health care in the United States with its increased specialization and emphasis on coordination of care with interprofessional teams. During the 2019/2020 academic year, the VA provided clinical training to approximately 21,000 AH HPTs from > 40 professions with just over 20% receiving financial support through the OAA. Of the HPTs who train at VA without compensation, most spend shorter amounts of time in clinical rotations in the VA, are in pregraduate-degree education programs where payment for clinical rotations is not expected and may not be eligible for hire immediately on completion of their clinical training experience. The 17 funded professions have been strategically selected by the OAA to ensure a robust pipeline of HCPs to meet the needs of veterans and the nation.

To meet the demands of AH professionals (AHPs), the OAA implemented targeted expansion over the past 10 years. While not exhaustive, this paper describes several expansion efforts based on VA special initiatives, including enhancing clinical access in rural settings and shifting toward postgraduate-degree training and specialization. By aligning expansion with VA priorities as well as trends in health care more broadly, the OAA can ensure that there is a supply of well-trained AHPs who have developed the requisite competencies to contribute to our nation’s health care needs. Further, expansion can help train and recruit health professionals who can be hired into VA positions ready to care for the complex needs of veterans.

Associated Health Professionals

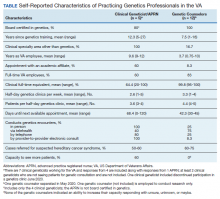

Overseen by the OAA, AH expansion is designed to address the specific needs of the VA and the US health care system. Data from the VA Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) shows that the VA employment of AHPs has grown from 87,351 AHPs hired in fiscal year (FY) 2010 to 119,120 as of April 2020. This represents an average yearly growth rate of 3.4% and a total growth rate of 36%. The Bureau of Labor Statistics predictions for 2019/2029 suggest that certain AHPs are expected to have a 10-year growth rates of 20% or more to meet the changing health care needs of patients especially as the population ages; the growth rates for many AHPs far surpasses that of physicians, which is anticipated to be 4% (Table).6,7 The VA WMC expects an additional 52,283 AHPs will be hired by the VA by FY 2030 based on the 10-year average growth rate (Kali Clark, Veterans Health Administration Workforce Management and Consulting Office, email communication, May 28, 2020).

One of the driving forces behind the growth rate is the move toward using AHPs to supplement health care for a variety of health conditions.8,9 Examples include the integration of rehabilitation professionals, alternative care professionals (eg, massage therapists, practitioners who offer training in yoga and meditation), chiropractors, MH professionals, and pharmacists in the treatment of chronic pain, the use of a wider range of professionals in the treatment of MH conditions, and the integration of MH professionals into traditional medical settings, such as primary care. This intentional move to a more well-integrated model of interprofessional care is apparent in many other health care systems throughout the United States. Within the VA, this shift may be most evident through the introduction of the Whole Health model of care. The Whole Health model of care uses an interprofessional team to assess and care for veterans, using a personalized health plan addressing medical and MH conditions as well as behavioral, social, or spiritual concerns.10 The Whole Health model of care provides veterans with access to a variety of health care services, including but not limited to MH services, spiritual interventions, exercise-based programs, yoga, meditation, and nutrition counseling.

The OAA and AH education division have focused expansion to meet the increased need for MH and rehabilitation providers, to enhance interprofessional education, and to emphasize postgraduate-degree clinical training. This focus reflects the trends seen in health care training broadly throughout the nation and the intentional pivot is a model of these trends and a model for how to intentionally address these trends. Specific to the VA, focused expansion plans have allowed OAA to address VA strategic initiatives such as pain management and caring for rural veterans.

Funded Training Positions

As a result of recent AH expansion efforts, there has been a 33% increase in stipend-funded positions during the past 10 years, a rate that directly corresponds with the growth of AHPs in the VA. Recent AH expansion efforts can contribute to a particularly positive impact in highly rural and underserved areas where recruiting providers remains challenging.

The OAA launched the Mental Health Education Expansion (MHEE) initiative in 2012, which has now added 782 funded training slots across 10 health professions, 8 of which are psychology, pharmacy, chaplaincy, professional MH counseling, marriage and family therapy (MFT), social work (SW), occupational therapy (OT), and physician assistant (PA). Through the MHEE initiative, the VA has established funded internships for licensed professional mental health counselors and marriage and family therapists, as these professions are targeted for expanding the overall MH workforce in the VA. The OAA currently funds more than 50 total HPT positions for these 2 professions with an aim of increasing their recruitment to the VA MH workforce over the next decade. The MHEE is aligned with specified VA priorities to train a future VA workforce prepared for interprofessional collaboration and clinical care in an increasingly integrated and complex environment. This expansion effort also aligns with an increasing understanding of the importance of addressing the MH needs of our nation by ensuring there is an adequate supply of competent, well-trained clinicians entering the workforce.

The OAA has created and expanded residencies and fellowships in multiple rehabilitation professions, including chiropractic, physical therapy (PT), and OT. With the increased focus on the management of chronic pain in the nation combined with a specific emphasis on this clinical need in the VA, chiropractors have been deemed essential HCPs. In 2014, the VA established 5 chiropractic residency programs while partnering with the Council on Chiropractic Education to develop accreditation standards for residency training. OAA’s efforts have yielded 5 accredited residency programs, the first in the United States. In 2020, the VA doubled the number of available chiropractic residency programs, and future expansion is anticipated. Since 2010, PT residencies have expanded from 1 to 28 programs (42 funded positions) across 4 board certification specialties: cardiovascular-pulmonary, geriatric, neurologic, and orthopedic. Similarly, the VA was one of the first organizations to achieve accreditation for OT fellowships; there are currently 5 accredited OT fellowship programs across 3 areas of practice: assistive technology, MH, and physical rehabilitation. The VA OT fellowship program focused on assistive technology is the only program in the United States at this time.

Interprofessional Education