User login

Effect of Pharmacist Interventions on Hospital Readmissions for Home-Based Primary Care Veterans

Following hospital discharge, patients are often in a vulnerable state due to new medical diagnoses, changes in medications, lack of understanding, and concerns for medical costs. In addition, the discharge process is complex and encompasses decisions regarding the postdischarge site of care, conveying patient instructions, and obtaining supplies and medications. There are several disciplines involved in the transitions of care process that are all essential for ensuring a successful transition and reducing the risk of hospital readmissions. Pharmacists play an integral role in the process.

When pharmacists are provided the opportunity to make therapeutic interventions, medication errors and hospital readmissions decrease and quality of life improves.1 Studies have shown that many older patients return home from the hospital with a limited understanding of their discharge instructions and oftentimes are unable to recall their discharge diagnoses and treatment plan, leaving opportunities for error when patients transition from one level of care to another.2,3 Additionally, high-quality transitional care is especially important for older adults with multiple comorbidities and complex therapeutic regimens as well as for their families and caregivers.4 To prevent hospital readmissions, pharmacists and other health care professionals (HCPs) should work diligently to prevent gaps in care as patients transition between settings. Common factors that lead to increased readmissions include premature discharge, inadequate follow-up, therapeutic errors, and medication-related problems. Furthermore, unintended hospital readmissions are common within the first 30 days following hospital discharge and lead to increased health care costs.2 For these reasons, many health care institutions have developed comprehensive models to improve the discharge process, decrease hospital readmissions, and reduce incidence of adverse events in general medical patients and high-risk populations.5

A study evaluating 693 hospital discharges found that 27.6% of patients were recommended for outpatient workups; however only 9% were actually completed.6 Due to lack of communication regarding discharge summaries, primary care practitioners (PCPs) were unaware of the need for outpatient workups; thus, these patients were lost to follow-up, and appropriate care was not received. Future studies should focus on interventions to improve the quality and dissemination of discharge information to PCPs.6 Fosnight and colleagues assessed a new transitions process focusing on the role of pharmacists. They evaluated medication reconciliations performed and discussed medication adherence barriers, medication recommendations, and time spent performing the interventions.7 After patients received a pharmacy intervention, Fosnight and colleagues reported that readmission rates decreased from 21.0% to 15.3% and mean length of stay decreased from 5.3 to 4.4 days. They also observed greater improvements in patients who received the full pharmacy intervention vs those receiving only parts of the intervention. This study concluded that adding a comprehensive pharmacy intervention to transitions of care resulted in an average of nearly 10 medication recommendations per patient, improved length of stay, and reduced readmission rates. After a review of similar studies, we concluded that a comprehensive discharge model is imperative to improve patient outcomes, along with HCP monitoring of the process to ensure appropriate follow-up.8

At Michael E. DeBakey Veteran Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, 30-day readmissions data were reviewed for veterans 6 months before and 12 months after enrollment in the Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) service. HBPC is an in-home health care service provided to home-bound veterans with complex health care needs or when routine clinic-based care is not feasible. HBPC programs may differ among various US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. Currently, there are 9 HBPC teams at MEDVAMC and nearly 540 veterans are enrolled in the program. HBPC teams typically consist of PCPs, pharmacists, nurses, psychologists, occupational/physical therapists, social workers, medical support assistants, and dietitians.

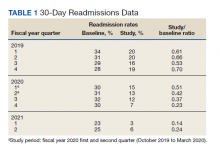

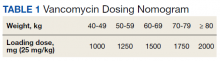

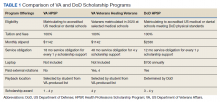

Readmissions data are reviewed quarterly by fiscal year (FY) (Table 1). In FY 2019 quarter (Q) 2, the readmission rate before HBPC enrollment was 31% and decreased to 20% after enrollment. In FY 2019 Q3, the readmission rate was 29% before enrollment and decreased to 16% afterward. In FY 2019 Q4, the readmission rate before HBPC enrollment was 28% and decreased to 19% afterward. Although the readmission rates appeared to be decreasing overall, improvements were needed to decrease these rates further and to ensure readmissions were not rising as there was a slight increase in Q4. After reviewing these data, the HBPC service implemented a streamlined hospital discharge process to lower readmission rates and improve patient outcomes.

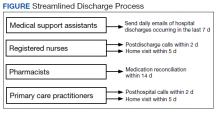

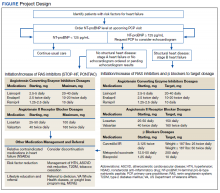

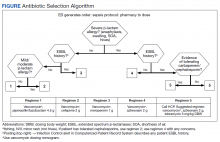

HBPC at MEDVAMC incorporates a team-based approach and the new streamlined discharge process implemented in 2019 highlights the role of each team member (Figure). Medical support assistants send daily emails of hospital discharges occurring in the last 7 days. Registered nurses are responsible for postdischarge calls within 2 days and home visits within 5 days. Pharmacists perform medication reconciliation within 14 days of discharge, review and/or educate on new medications, and change medications. The PCP is responsible for posthospital calls within 2 days and conducts a home visit within 5 days. Because HBPC programs vary among VA medical centers, the streamlined discharge process discussed may be applicable only to MEDVAMC. The primary objective of this quality improvement project was to identify specific pharmacist interventions to improve the HBPC discharge process and improve hospital readmission rates.

Methods

We conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act quality improvement project. The first step was to conduct a review of veterans enrolled in HBPC at MEDVAMC.9 Patients included were enrolled in HBPC at MEDVAMC from October 2019 to March 2020 (FY 2020 Q1 and Q2). The Computerized Patient Record System was used to access the patients’ electronic health records. Patient information collected included race, age, sex, admission diagnosis, date of discharge, HBPC pharmacist name, PCP notification on the discharge summary, and 30-day readmission rates. Unplanned return to the hospital within 30 days, which was counted as a readmission, was defined as any admission for acute clinical events that required urgent hospital management.10

Next, we identified specific pharmacist interventions, including medication reconciliation completed by an HBPC pharmacist postdischarge; mean time to contact patients postdischarge; correct medications and supplies on discharge; incorrect dose; incorrect medication frequency or route of administration; therapeutic duplications; discontinuation of medications; additional drug therapy recommendations; laboratory test recommendations; maintenance medications not restarted or omitted; new medication education; and medication or formulation changes.

In the third step, we reviewed discharge summaries and clinical pharmacy notes to collect pharmacist intervention data. These data were analyzed to develop a standardized discharge process. Descriptive statistics were used to represent the results of the study.

Results

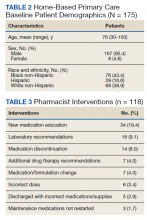

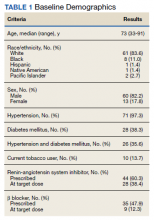

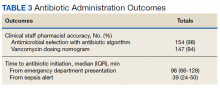

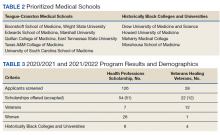

Medication reconciliation was completed postdischarge by an HBPC pharmacist in 118 of 175 study patients (67.4%). The mean age of patients was 76 years, about 95% were male (Table 2). There was a wide variety of admission diagnoses but sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease were most common. The PCP was notified on the discharge note for 68 (38.9%) patients. The mean time for HBPC pharmacists to contact patients postdischarge was about 3 days, which was much less than the 14 days allowed in the streamlined discharge process.

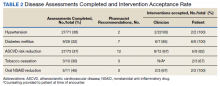

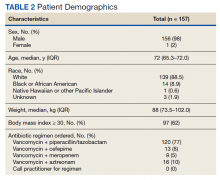

Pharmacists made the following interventions during medication reconciliation: New medication education was provided for 34 (19.4%) patients and was the largest intervention completed by HBPC pharmacists. Laboratory tests were recommended for 16 (9.1%) patients, medications were discontinued in 14 (8.0%) patients, and additional drug therapy recommendations were made for 7 (4.0%) patients. Medication or formulation changes were completed in 7 (4.0%) patients, incorrect doses were identified in 6 (3.4%) patients, 5 (2.9%) patients were not discharged with the correct medications or supplies, maintenance medications were not restarted in 3 (1.7%) patients, and there were no therapeutic duplications identified. In total, there were 92 (77.9%) patients with interventions compared with the 118 medication reconciliations completed (Table 3).

Process Improvement

As this was a new streamlined discharge process, it was important to assess the progress of the pharmacist role over time. We evaluated the number of medication reconciliations completed by quarter to determine whether more interventions were completed as the streamlined discharge process was being fully implemented. In FY 2020 Q1, medication reconciliation was completed by an HBPC pharmacist at a rate of 35%, and in FY 2020 Q2, at a rate of 65%.

In addition to assessing interventions completed by an HBPC pharmacist, we noted how many medication reconciliations were completed by an inpatient pharmacist as this may have impacted the results of this study. Of the 175 patients in this study, 49 (28%) received a medication reconciliation by an inpatient clinical pharmacy specialist before discharge. Last, when reviewing the readmissions data for the study period, it was evident that the streamlined discharge process was improving. In FY 2020 Q1, the readmissions rate prior to HBPC enrollment was 30% and decreased to 15% after and in FY 2020 Q2 was 31% before and decreased to 13% after HBPC enrollment. Before the study period in FY 2019 Q4, the readmissions rate after HBPC enrollment was 19%. Therefore, the readmissions rate decreased from 19% before the study period to 13% by the end of the study period.

Discussion

A comparison of the readmissions data from FYs 2019, 2020, and 2021 revealed that the newly implemented discharge process at MEDVAMC had been more effective.

There were 92 interventions made during the study period, which is about 78% of all medication reconciliations completed. Medication doses were changed based on patients’ renal function. Additional laboratory tests were recommended after discharge to ensure safety of therapy. Medications were discontinued if inappropriate or if patients were no longer on them to simplify their medication list and limit polypharmacy. New medication education was provided, including drug name, dose, route of administration, time of administration, frequency, indication, mechanism of action, adverse effect profile, monitoring parameters, and more. The HBPC pharmacists were able to make suitable interventions in a timely fashion as the average time to contact patients postdischarge was 3 days.

Areas for Improvement

The PCP was notified on the discharge note only in 68 (38.9%) patients. This could lead to gaps in care if other mechanisms are not in place to notify the PCP of the patient’s discharge. For this reason, it is imperative not only to implement a streamlined discharge process, but to review it and determine methods for continued improvement.9 The streamlined discharge process implemented by the HBPC team highlights when each team member should contact the patient postdischarge. However, it may be beneficial for each team member to have a list of vital information that should be communicated to the patient postdischarge and to other HCPs. For pharmacists, a standardized discharge note template may aid in the consistency of the medication reconciliation process postdischarge and may also increase interventions from pharmacists. For example, only some HBPC pharmacists inserted a new medication template in their discharge follow-up note. In addition, 23 (13.1%) patients were unreachable, and although a complete medication reconciliation was not feasible, a standardized note to review inpatient and outpatient medications along with the discharge plan may still serve as an asset for HCPs.

As the HBPC team continues to improve the discharge process, it is also important to highlight roles of the inpatient team who may assist with a smoother transition. For example, discharge summaries should be clear, complete, and concise, incorporating key elements from the hospital visit. Methods of communication on discharge should be efficient and understood by both inpatient and outpatient teams. Patients’ health literacy status should be considered when providing discharge instructions. Finally, patients should have a clear understanding of who is included in their primary care team should any questions arise. The potential interventions for HCPs highlighted in this study are critical for preventing adverse outcomes, improving patients’ quality of life, and decreasing hospital readmissions. However, implementing the streamlined discharge process was only step 1. Areas of improvement still exist to provide exceptional patient care.

Our goal is to increase pharmacist-led medication reconciliation after discharge to ≥ 80%. This will be assessed monthly after providing education to the HBPC team regarding the study results. The second goal is to maintain hospital readmission rates to ≤ 10%, which will be assessed with each quarterly review.

Strengths and Limitations

This study was one of the first to evaluate the impact of pharmacist intervention on improving patient outcomes in HBPC veterans. Additionally, only 1 investigator conducted the data collection, which decreased the opportunity for errors.

A notable limitation of this study is that the discharge processes may not be able to be duplicated in other HBPC settings due to variability in programs. Additionally, as this was a new discharge process, there were a few aspects that needed to be worked out in the beginning as it was established. Furthermore, this study did not clarify whether a medication reconciliation was conducted by a physician or nurse after discharge; therefore, this study cannot conclude that the medication interventions were solely attributed to pharmacists. Also this study did not assess readmissions for recurrent events only, which may have impacted the results in a different way from the current results that assessed readmission rates for any hospitalization. Other limitations include the retrospective study design at a single center.

Conclusions

This study outlines several opportunities for interventions to improve patient outcomes and aid in decreasing hospital readmission rates. Using the results from this study, education has been provided for the HBPC Service and its readmission committee. Additionally, the safety concerns identified have been addressed with inpatient and outpatient pharmacy leadership to improve the practices in both settings, prevent delays in patient care, and avoid future adverse outcomes. This project highlights the advantages of having pharmacists involved in transitions of care and demonstrates the benefit of HBPC pharmacists’ role in the streamlined discharge process. This project will be reviewed biannually to further improve the discharge process and quality of care for our veterans.

1. Coleman EA, Chugh A, Williams MV, et al. Understanding and execution of discharge instructions. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(5):383-391. doi:10.1177/1062860612472931

2. Hume AL, Kirwin J, Bieber HL, et al. Improving care transitions: current practice and future opportunities for pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(11):e326-e337. doi:10.1002/phar.1215

3. Milfred-LaForest SK, Gee JA, Pugacz AM, et al. Heart failure transitions of care: a pharmacist-led post discharge pilot experience. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60(2):249-258. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2017.08.005

4. Naylor M, Keating SA. Transitional care: moving patients from one care setting to another. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(suppl 9):58-63. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336420.34946.3a

5. Rennke S, Nguyen OK, Shoeb MH, Magan Y, Wachter RM, Ranji SR. Hospital-initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5, pt 2):433-440. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00011

6. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1305-1311. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

7. Fosnight S, King P, Ewald J, et al. Effects of pharmacy interventions at transitions of care on patient outcomes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(12):943-949. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa081

8. Shull MT, Braitman LE, Stites SD, DeLuca A, Hauser D. Effects of a pharmacist-driven intervention program on hospital readmissions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(9):e221-e230. doi:10.2146/ajhp170287

9. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. February 2015. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html10. Horwitz L, Partovian C, Lin Z, et al. Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. Hospital-wide (all-condition) 30-day risk-standardized readmission measure. Updated August 20 2011. Accessed June 2, 2022. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/mms/downloads/mmshospital-wideall-conditionreadmissionrate.pdf

Following hospital discharge, patients are often in a vulnerable state due to new medical diagnoses, changes in medications, lack of understanding, and concerns for medical costs. In addition, the discharge process is complex and encompasses decisions regarding the postdischarge site of care, conveying patient instructions, and obtaining supplies and medications. There are several disciplines involved in the transitions of care process that are all essential for ensuring a successful transition and reducing the risk of hospital readmissions. Pharmacists play an integral role in the process.

When pharmacists are provided the opportunity to make therapeutic interventions, medication errors and hospital readmissions decrease and quality of life improves.1 Studies have shown that many older patients return home from the hospital with a limited understanding of their discharge instructions and oftentimes are unable to recall their discharge diagnoses and treatment plan, leaving opportunities for error when patients transition from one level of care to another.2,3 Additionally, high-quality transitional care is especially important for older adults with multiple comorbidities and complex therapeutic regimens as well as for their families and caregivers.4 To prevent hospital readmissions, pharmacists and other health care professionals (HCPs) should work diligently to prevent gaps in care as patients transition between settings. Common factors that lead to increased readmissions include premature discharge, inadequate follow-up, therapeutic errors, and medication-related problems. Furthermore, unintended hospital readmissions are common within the first 30 days following hospital discharge and lead to increased health care costs.2 For these reasons, many health care institutions have developed comprehensive models to improve the discharge process, decrease hospital readmissions, and reduce incidence of adverse events in general medical patients and high-risk populations.5

A study evaluating 693 hospital discharges found that 27.6% of patients were recommended for outpatient workups; however only 9% were actually completed.6 Due to lack of communication regarding discharge summaries, primary care practitioners (PCPs) were unaware of the need for outpatient workups; thus, these patients were lost to follow-up, and appropriate care was not received. Future studies should focus on interventions to improve the quality and dissemination of discharge information to PCPs.6 Fosnight and colleagues assessed a new transitions process focusing on the role of pharmacists. They evaluated medication reconciliations performed and discussed medication adherence barriers, medication recommendations, and time spent performing the interventions.7 After patients received a pharmacy intervention, Fosnight and colleagues reported that readmission rates decreased from 21.0% to 15.3% and mean length of stay decreased from 5.3 to 4.4 days. They also observed greater improvements in patients who received the full pharmacy intervention vs those receiving only parts of the intervention. This study concluded that adding a comprehensive pharmacy intervention to transitions of care resulted in an average of nearly 10 medication recommendations per patient, improved length of stay, and reduced readmission rates. After a review of similar studies, we concluded that a comprehensive discharge model is imperative to improve patient outcomes, along with HCP monitoring of the process to ensure appropriate follow-up.8

At Michael E. DeBakey Veteran Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, 30-day readmissions data were reviewed for veterans 6 months before and 12 months after enrollment in the Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) service. HBPC is an in-home health care service provided to home-bound veterans with complex health care needs or when routine clinic-based care is not feasible. HBPC programs may differ among various US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. Currently, there are 9 HBPC teams at MEDVAMC and nearly 540 veterans are enrolled in the program. HBPC teams typically consist of PCPs, pharmacists, nurses, psychologists, occupational/physical therapists, social workers, medical support assistants, and dietitians.

Readmissions data are reviewed quarterly by fiscal year (FY) (Table 1). In FY 2019 quarter (Q) 2, the readmission rate before HBPC enrollment was 31% and decreased to 20% after enrollment. In FY 2019 Q3, the readmission rate was 29% before enrollment and decreased to 16% afterward. In FY 2019 Q4, the readmission rate before HBPC enrollment was 28% and decreased to 19% afterward. Although the readmission rates appeared to be decreasing overall, improvements were needed to decrease these rates further and to ensure readmissions were not rising as there was a slight increase in Q4. After reviewing these data, the HBPC service implemented a streamlined hospital discharge process to lower readmission rates and improve patient outcomes.

HBPC at MEDVAMC incorporates a team-based approach and the new streamlined discharge process implemented in 2019 highlights the role of each team member (Figure). Medical support assistants send daily emails of hospital discharges occurring in the last 7 days. Registered nurses are responsible for postdischarge calls within 2 days and home visits within 5 days. Pharmacists perform medication reconciliation within 14 days of discharge, review and/or educate on new medications, and change medications. The PCP is responsible for posthospital calls within 2 days and conducts a home visit within 5 days. Because HBPC programs vary among VA medical centers, the streamlined discharge process discussed may be applicable only to MEDVAMC. The primary objective of this quality improvement project was to identify specific pharmacist interventions to improve the HBPC discharge process and improve hospital readmission rates.

Methods

We conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act quality improvement project. The first step was to conduct a review of veterans enrolled in HBPC at MEDVAMC.9 Patients included were enrolled in HBPC at MEDVAMC from October 2019 to March 2020 (FY 2020 Q1 and Q2). The Computerized Patient Record System was used to access the patients’ electronic health records. Patient information collected included race, age, sex, admission diagnosis, date of discharge, HBPC pharmacist name, PCP notification on the discharge summary, and 30-day readmission rates. Unplanned return to the hospital within 30 days, which was counted as a readmission, was defined as any admission for acute clinical events that required urgent hospital management.10

Next, we identified specific pharmacist interventions, including medication reconciliation completed by an HBPC pharmacist postdischarge; mean time to contact patients postdischarge; correct medications and supplies on discharge; incorrect dose; incorrect medication frequency or route of administration; therapeutic duplications; discontinuation of medications; additional drug therapy recommendations; laboratory test recommendations; maintenance medications not restarted or omitted; new medication education; and medication or formulation changes.

In the third step, we reviewed discharge summaries and clinical pharmacy notes to collect pharmacist intervention data. These data were analyzed to develop a standardized discharge process. Descriptive statistics were used to represent the results of the study.

Results

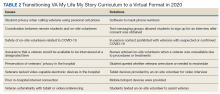

Medication reconciliation was completed postdischarge by an HBPC pharmacist in 118 of 175 study patients (67.4%). The mean age of patients was 76 years, about 95% were male (Table 2). There was a wide variety of admission diagnoses but sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease were most common. The PCP was notified on the discharge note for 68 (38.9%) patients. The mean time for HBPC pharmacists to contact patients postdischarge was about 3 days, which was much less than the 14 days allowed in the streamlined discharge process.

Pharmacists made the following interventions during medication reconciliation: New medication education was provided for 34 (19.4%) patients and was the largest intervention completed by HBPC pharmacists. Laboratory tests were recommended for 16 (9.1%) patients, medications were discontinued in 14 (8.0%) patients, and additional drug therapy recommendations were made for 7 (4.0%) patients. Medication or formulation changes were completed in 7 (4.0%) patients, incorrect doses were identified in 6 (3.4%) patients, 5 (2.9%) patients were not discharged with the correct medications or supplies, maintenance medications were not restarted in 3 (1.7%) patients, and there were no therapeutic duplications identified. In total, there were 92 (77.9%) patients with interventions compared with the 118 medication reconciliations completed (Table 3).

Process Improvement

As this was a new streamlined discharge process, it was important to assess the progress of the pharmacist role over time. We evaluated the number of medication reconciliations completed by quarter to determine whether more interventions were completed as the streamlined discharge process was being fully implemented. In FY 2020 Q1, medication reconciliation was completed by an HBPC pharmacist at a rate of 35%, and in FY 2020 Q2, at a rate of 65%.

In addition to assessing interventions completed by an HBPC pharmacist, we noted how many medication reconciliations were completed by an inpatient pharmacist as this may have impacted the results of this study. Of the 175 patients in this study, 49 (28%) received a medication reconciliation by an inpatient clinical pharmacy specialist before discharge. Last, when reviewing the readmissions data for the study period, it was evident that the streamlined discharge process was improving. In FY 2020 Q1, the readmissions rate prior to HBPC enrollment was 30% and decreased to 15% after and in FY 2020 Q2 was 31% before and decreased to 13% after HBPC enrollment. Before the study period in FY 2019 Q4, the readmissions rate after HBPC enrollment was 19%. Therefore, the readmissions rate decreased from 19% before the study period to 13% by the end of the study period.

Discussion

A comparison of the readmissions data from FYs 2019, 2020, and 2021 revealed that the newly implemented discharge process at MEDVAMC had been more effective.

There were 92 interventions made during the study period, which is about 78% of all medication reconciliations completed. Medication doses were changed based on patients’ renal function. Additional laboratory tests were recommended after discharge to ensure safety of therapy. Medications were discontinued if inappropriate or if patients were no longer on them to simplify their medication list and limit polypharmacy. New medication education was provided, including drug name, dose, route of administration, time of administration, frequency, indication, mechanism of action, adverse effect profile, monitoring parameters, and more. The HBPC pharmacists were able to make suitable interventions in a timely fashion as the average time to contact patients postdischarge was 3 days.

Areas for Improvement

The PCP was notified on the discharge note only in 68 (38.9%) patients. This could lead to gaps in care if other mechanisms are not in place to notify the PCP of the patient’s discharge. For this reason, it is imperative not only to implement a streamlined discharge process, but to review it and determine methods for continued improvement.9 The streamlined discharge process implemented by the HBPC team highlights when each team member should contact the patient postdischarge. However, it may be beneficial for each team member to have a list of vital information that should be communicated to the patient postdischarge and to other HCPs. For pharmacists, a standardized discharge note template may aid in the consistency of the medication reconciliation process postdischarge and may also increase interventions from pharmacists. For example, only some HBPC pharmacists inserted a new medication template in their discharge follow-up note. In addition, 23 (13.1%) patients were unreachable, and although a complete medication reconciliation was not feasible, a standardized note to review inpatient and outpatient medications along with the discharge plan may still serve as an asset for HCPs.

As the HBPC team continues to improve the discharge process, it is also important to highlight roles of the inpatient team who may assist with a smoother transition. For example, discharge summaries should be clear, complete, and concise, incorporating key elements from the hospital visit. Methods of communication on discharge should be efficient and understood by both inpatient and outpatient teams. Patients’ health literacy status should be considered when providing discharge instructions. Finally, patients should have a clear understanding of who is included in their primary care team should any questions arise. The potential interventions for HCPs highlighted in this study are critical for preventing adverse outcomes, improving patients’ quality of life, and decreasing hospital readmissions. However, implementing the streamlined discharge process was only step 1. Areas of improvement still exist to provide exceptional patient care.

Our goal is to increase pharmacist-led medication reconciliation after discharge to ≥ 80%. This will be assessed monthly after providing education to the HBPC team regarding the study results. The second goal is to maintain hospital readmission rates to ≤ 10%, which will be assessed with each quarterly review.

Strengths and Limitations

This study was one of the first to evaluate the impact of pharmacist intervention on improving patient outcomes in HBPC veterans. Additionally, only 1 investigator conducted the data collection, which decreased the opportunity for errors.

A notable limitation of this study is that the discharge processes may not be able to be duplicated in other HBPC settings due to variability in programs. Additionally, as this was a new discharge process, there were a few aspects that needed to be worked out in the beginning as it was established. Furthermore, this study did not clarify whether a medication reconciliation was conducted by a physician or nurse after discharge; therefore, this study cannot conclude that the medication interventions were solely attributed to pharmacists. Also this study did not assess readmissions for recurrent events only, which may have impacted the results in a different way from the current results that assessed readmission rates for any hospitalization. Other limitations include the retrospective study design at a single center.

Conclusions

This study outlines several opportunities for interventions to improve patient outcomes and aid in decreasing hospital readmission rates. Using the results from this study, education has been provided for the HBPC Service and its readmission committee. Additionally, the safety concerns identified have been addressed with inpatient and outpatient pharmacy leadership to improve the practices in both settings, prevent delays in patient care, and avoid future adverse outcomes. This project highlights the advantages of having pharmacists involved in transitions of care and demonstrates the benefit of HBPC pharmacists’ role in the streamlined discharge process. This project will be reviewed biannually to further improve the discharge process and quality of care for our veterans.

Following hospital discharge, patients are often in a vulnerable state due to new medical diagnoses, changes in medications, lack of understanding, and concerns for medical costs. In addition, the discharge process is complex and encompasses decisions regarding the postdischarge site of care, conveying patient instructions, and obtaining supplies and medications. There are several disciplines involved in the transitions of care process that are all essential for ensuring a successful transition and reducing the risk of hospital readmissions. Pharmacists play an integral role in the process.

When pharmacists are provided the opportunity to make therapeutic interventions, medication errors and hospital readmissions decrease and quality of life improves.1 Studies have shown that many older patients return home from the hospital with a limited understanding of their discharge instructions and oftentimes are unable to recall their discharge diagnoses and treatment plan, leaving opportunities for error when patients transition from one level of care to another.2,3 Additionally, high-quality transitional care is especially important for older adults with multiple comorbidities and complex therapeutic regimens as well as for their families and caregivers.4 To prevent hospital readmissions, pharmacists and other health care professionals (HCPs) should work diligently to prevent gaps in care as patients transition between settings. Common factors that lead to increased readmissions include premature discharge, inadequate follow-up, therapeutic errors, and medication-related problems. Furthermore, unintended hospital readmissions are common within the first 30 days following hospital discharge and lead to increased health care costs.2 For these reasons, many health care institutions have developed comprehensive models to improve the discharge process, decrease hospital readmissions, and reduce incidence of adverse events in general medical patients and high-risk populations.5

A study evaluating 693 hospital discharges found that 27.6% of patients were recommended for outpatient workups; however only 9% were actually completed.6 Due to lack of communication regarding discharge summaries, primary care practitioners (PCPs) were unaware of the need for outpatient workups; thus, these patients were lost to follow-up, and appropriate care was not received. Future studies should focus on interventions to improve the quality and dissemination of discharge information to PCPs.6 Fosnight and colleagues assessed a new transitions process focusing on the role of pharmacists. They evaluated medication reconciliations performed and discussed medication adherence barriers, medication recommendations, and time spent performing the interventions.7 After patients received a pharmacy intervention, Fosnight and colleagues reported that readmission rates decreased from 21.0% to 15.3% and mean length of stay decreased from 5.3 to 4.4 days. They also observed greater improvements in patients who received the full pharmacy intervention vs those receiving only parts of the intervention. This study concluded that adding a comprehensive pharmacy intervention to transitions of care resulted in an average of nearly 10 medication recommendations per patient, improved length of stay, and reduced readmission rates. After a review of similar studies, we concluded that a comprehensive discharge model is imperative to improve patient outcomes, along with HCP monitoring of the process to ensure appropriate follow-up.8

At Michael E. DeBakey Veteran Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, 30-day readmissions data were reviewed for veterans 6 months before and 12 months after enrollment in the Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) service. HBPC is an in-home health care service provided to home-bound veterans with complex health care needs or when routine clinic-based care is not feasible. HBPC programs may differ among various US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. Currently, there are 9 HBPC teams at MEDVAMC and nearly 540 veterans are enrolled in the program. HBPC teams typically consist of PCPs, pharmacists, nurses, psychologists, occupational/physical therapists, social workers, medical support assistants, and dietitians.

Readmissions data are reviewed quarterly by fiscal year (FY) (Table 1). In FY 2019 quarter (Q) 2, the readmission rate before HBPC enrollment was 31% and decreased to 20% after enrollment. In FY 2019 Q3, the readmission rate was 29% before enrollment and decreased to 16% afterward. In FY 2019 Q4, the readmission rate before HBPC enrollment was 28% and decreased to 19% afterward. Although the readmission rates appeared to be decreasing overall, improvements were needed to decrease these rates further and to ensure readmissions were not rising as there was a slight increase in Q4. After reviewing these data, the HBPC service implemented a streamlined hospital discharge process to lower readmission rates and improve patient outcomes.

HBPC at MEDVAMC incorporates a team-based approach and the new streamlined discharge process implemented in 2019 highlights the role of each team member (Figure). Medical support assistants send daily emails of hospital discharges occurring in the last 7 days. Registered nurses are responsible for postdischarge calls within 2 days and home visits within 5 days. Pharmacists perform medication reconciliation within 14 days of discharge, review and/or educate on new medications, and change medications. The PCP is responsible for posthospital calls within 2 days and conducts a home visit within 5 days. Because HBPC programs vary among VA medical centers, the streamlined discharge process discussed may be applicable only to MEDVAMC. The primary objective of this quality improvement project was to identify specific pharmacist interventions to improve the HBPC discharge process and improve hospital readmission rates.

Methods

We conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act quality improvement project. The first step was to conduct a review of veterans enrolled in HBPC at MEDVAMC.9 Patients included were enrolled in HBPC at MEDVAMC from October 2019 to March 2020 (FY 2020 Q1 and Q2). The Computerized Patient Record System was used to access the patients’ electronic health records. Patient information collected included race, age, sex, admission diagnosis, date of discharge, HBPC pharmacist name, PCP notification on the discharge summary, and 30-day readmission rates. Unplanned return to the hospital within 30 days, which was counted as a readmission, was defined as any admission for acute clinical events that required urgent hospital management.10

Next, we identified specific pharmacist interventions, including medication reconciliation completed by an HBPC pharmacist postdischarge; mean time to contact patients postdischarge; correct medications and supplies on discharge; incorrect dose; incorrect medication frequency or route of administration; therapeutic duplications; discontinuation of medications; additional drug therapy recommendations; laboratory test recommendations; maintenance medications not restarted or omitted; new medication education; and medication or formulation changes.

In the third step, we reviewed discharge summaries and clinical pharmacy notes to collect pharmacist intervention data. These data were analyzed to develop a standardized discharge process. Descriptive statistics were used to represent the results of the study.

Results

Medication reconciliation was completed postdischarge by an HBPC pharmacist in 118 of 175 study patients (67.4%). The mean age of patients was 76 years, about 95% were male (Table 2). There was a wide variety of admission diagnoses but sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease were most common. The PCP was notified on the discharge note for 68 (38.9%) patients. The mean time for HBPC pharmacists to contact patients postdischarge was about 3 days, which was much less than the 14 days allowed in the streamlined discharge process.

Pharmacists made the following interventions during medication reconciliation: New medication education was provided for 34 (19.4%) patients and was the largest intervention completed by HBPC pharmacists. Laboratory tests were recommended for 16 (9.1%) patients, medications were discontinued in 14 (8.0%) patients, and additional drug therapy recommendations were made for 7 (4.0%) patients. Medication or formulation changes were completed in 7 (4.0%) patients, incorrect doses were identified in 6 (3.4%) patients, 5 (2.9%) patients were not discharged with the correct medications or supplies, maintenance medications were not restarted in 3 (1.7%) patients, and there were no therapeutic duplications identified. In total, there were 92 (77.9%) patients with interventions compared with the 118 medication reconciliations completed (Table 3).

Process Improvement

As this was a new streamlined discharge process, it was important to assess the progress of the pharmacist role over time. We evaluated the number of medication reconciliations completed by quarter to determine whether more interventions were completed as the streamlined discharge process was being fully implemented. In FY 2020 Q1, medication reconciliation was completed by an HBPC pharmacist at a rate of 35%, and in FY 2020 Q2, at a rate of 65%.

In addition to assessing interventions completed by an HBPC pharmacist, we noted how many medication reconciliations were completed by an inpatient pharmacist as this may have impacted the results of this study. Of the 175 patients in this study, 49 (28%) received a medication reconciliation by an inpatient clinical pharmacy specialist before discharge. Last, when reviewing the readmissions data for the study period, it was evident that the streamlined discharge process was improving. In FY 2020 Q1, the readmissions rate prior to HBPC enrollment was 30% and decreased to 15% after and in FY 2020 Q2 was 31% before and decreased to 13% after HBPC enrollment. Before the study period in FY 2019 Q4, the readmissions rate after HBPC enrollment was 19%. Therefore, the readmissions rate decreased from 19% before the study period to 13% by the end of the study period.

Discussion

A comparison of the readmissions data from FYs 2019, 2020, and 2021 revealed that the newly implemented discharge process at MEDVAMC had been more effective.

There were 92 interventions made during the study period, which is about 78% of all medication reconciliations completed. Medication doses were changed based on patients’ renal function. Additional laboratory tests were recommended after discharge to ensure safety of therapy. Medications were discontinued if inappropriate or if patients were no longer on them to simplify their medication list and limit polypharmacy. New medication education was provided, including drug name, dose, route of administration, time of administration, frequency, indication, mechanism of action, adverse effect profile, monitoring parameters, and more. The HBPC pharmacists were able to make suitable interventions in a timely fashion as the average time to contact patients postdischarge was 3 days.

Areas for Improvement

The PCP was notified on the discharge note only in 68 (38.9%) patients. This could lead to gaps in care if other mechanisms are not in place to notify the PCP of the patient’s discharge. For this reason, it is imperative not only to implement a streamlined discharge process, but to review it and determine methods for continued improvement.9 The streamlined discharge process implemented by the HBPC team highlights when each team member should contact the patient postdischarge. However, it may be beneficial for each team member to have a list of vital information that should be communicated to the patient postdischarge and to other HCPs. For pharmacists, a standardized discharge note template may aid in the consistency of the medication reconciliation process postdischarge and may also increase interventions from pharmacists. For example, only some HBPC pharmacists inserted a new medication template in their discharge follow-up note. In addition, 23 (13.1%) patients were unreachable, and although a complete medication reconciliation was not feasible, a standardized note to review inpatient and outpatient medications along with the discharge plan may still serve as an asset for HCPs.

As the HBPC team continues to improve the discharge process, it is also important to highlight roles of the inpatient team who may assist with a smoother transition. For example, discharge summaries should be clear, complete, and concise, incorporating key elements from the hospital visit. Methods of communication on discharge should be efficient and understood by both inpatient and outpatient teams. Patients’ health literacy status should be considered when providing discharge instructions. Finally, patients should have a clear understanding of who is included in their primary care team should any questions arise. The potential interventions for HCPs highlighted in this study are critical for preventing adverse outcomes, improving patients’ quality of life, and decreasing hospital readmissions. However, implementing the streamlined discharge process was only step 1. Areas of improvement still exist to provide exceptional patient care.

Our goal is to increase pharmacist-led medication reconciliation after discharge to ≥ 80%. This will be assessed monthly after providing education to the HBPC team regarding the study results. The second goal is to maintain hospital readmission rates to ≤ 10%, which will be assessed with each quarterly review.

Strengths and Limitations

This study was one of the first to evaluate the impact of pharmacist intervention on improving patient outcomes in HBPC veterans. Additionally, only 1 investigator conducted the data collection, which decreased the opportunity for errors.

A notable limitation of this study is that the discharge processes may not be able to be duplicated in other HBPC settings due to variability in programs. Additionally, as this was a new discharge process, there were a few aspects that needed to be worked out in the beginning as it was established. Furthermore, this study did not clarify whether a medication reconciliation was conducted by a physician or nurse after discharge; therefore, this study cannot conclude that the medication interventions were solely attributed to pharmacists. Also this study did not assess readmissions for recurrent events only, which may have impacted the results in a different way from the current results that assessed readmission rates for any hospitalization. Other limitations include the retrospective study design at a single center.

Conclusions

This study outlines several opportunities for interventions to improve patient outcomes and aid in decreasing hospital readmission rates. Using the results from this study, education has been provided for the HBPC Service and its readmission committee. Additionally, the safety concerns identified have been addressed with inpatient and outpatient pharmacy leadership to improve the practices in both settings, prevent delays in patient care, and avoid future adverse outcomes. This project highlights the advantages of having pharmacists involved in transitions of care and demonstrates the benefit of HBPC pharmacists’ role in the streamlined discharge process. This project will be reviewed biannually to further improve the discharge process and quality of care for our veterans.

1. Coleman EA, Chugh A, Williams MV, et al. Understanding and execution of discharge instructions. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(5):383-391. doi:10.1177/1062860612472931

2. Hume AL, Kirwin J, Bieber HL, et al. Improving care transitions: current practice and future opportunities for pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(11):e326-e337. doi:10.1002/phar.1215

3. Milfred-LaForest SK, Gee JA, Pugacz AM, et al. Heart failure transitions of care: a pharmacist-led post discharge pilot experience. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60(2):249-258. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2017.08.005

4. Naylor M, Keating SA. Transitional care: moving patients from one care setting to another. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(suppl 9):58-63. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336420.34946.3a

5. Rennke S, Nguyen OK, Shoeb MH, Magan Y, Wachter RM, Ranji SR. Hospital-initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5, pt 2):433-440. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00011

6. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1305-1311. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

7. Fosnight S, King P, Ewald J, et al. Effects of pharmacy interventions at transitions of care on patient outcomes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(12):943-949. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa081

8. Shull MT, Braitman LE, Stites SD, DeLuca A, Hauser D. Effects of a pharmacist-driven intervention program on hospital readmissions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(9):e221-e230. doi:10.2146/ajhp170287

9. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. February 2015. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html10. Horwitz L, Partovian C, Lin Z, et al. Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. Hospital-wide (all-condition) 30-day risk-standardized readmission measure. Updated August 20 2011. Accessed June 2, 2022. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/mms/downloads/mmshospital-wideall-conditionreadmissionrate.pdf

1. Coleman EA, Chugh A, Williams MV, et al. Understanding and execution of discharge instructions. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(5):383-391. doi:10.1177/1062860612472931

2. Hume AL, Kirwin J, Bieber HL, et al. Improving care transitions: current practice and future opportunities for pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(11):e326-e337. doi:10.1002/phar.1215

3. Milfred-LaForest SK, Gee JA, Pugacz AM, et al. Heart failure transitions of care: a pharmacist-led post discharge pilot experience. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60(2):249-258. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2017.08.005

4. Naylor M, Keating SA. Transitional care: moving patients from one care setting to another. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(suppl 9):58-63. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336420.34946.3a

5. Rennke S, Nguyen OK, Shoeb MH, Magan Y, Wachter RM, Ranji SR. Hospital-initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5, pt 2):433-440. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00011

6. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1305-1311. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

7. Fosnight S, King P, Ewald J, et al. Effects of pharmacy interventions at transitions of care on patient outcomes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(12):943-949. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa081

8. Shull MT, Braitman LE, Stites SD, DeLuca A, Hauser D. Effects of a pharmacist-driven intervention program on hospital readmissions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(9):e221-e230. doi:10.2146/ajhp170287

9. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. February 2015. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html10. Horwitz L, Partovian C, Lin Z, et al. Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. Hospital-wide (all-condition) 30-day risk-standardized readmission measure. Updated August 20 2011. Accessed June 2, 2022. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/mms/downloads/mmshospital-wideall-conditionreadmissionrate.pdf

A Learning Health System Approach to Long COVID Care

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA)—along with systems across the world—has spent the past 2 years continuously adapting to meet the emerging needs of persons infected with COVID-19. With the development of effective vaccines and global efforts to mitigate transmission, attention has now shifted to long COVID care as the need for further outpatient health care becomes increasingly apparent.1,2

Background

Multiple terms describe the lingering, multisystem sequelae of COVID-19 that last longer than 4 weeks: long COVID, postacute COVID-19 syndrome, post-COVID condition, postacute sequalae of COVID-19, and COVID long hauler.1,3 Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cough, sleep disorders, brain fog or cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, pain, and changes in taste or smell that impact a person’s functioning.4,5 The multisystem nature of the postacute course of COVID-19 necessitates an interdisciplinary approach to devise comprehensive and individualized care plans.6-9 Research is needed to better understand this postacute state (eg, prevalence, underlying effects, characteristics of those who experience long COVID) to establish and evaluate cost-effective treatment approaches.

Many patients who are experiencing symptoms beyond the acute course of COVID-19 have been referred to general outpatient clinics or home health, which may lack the capacity and knowledge of this novel disease to effectively manage complex long COVID cases.2,3 To address this growing need, clinicians and leadership across a variety of disciplines and settings in the VHA created a community of practice (CoP) to create a mechanism for cross-facility communication, identify gaps in long COVID care and research, and cocreate knowledge on best practices for care delivery.

In this spirit, we are embracing a learning health system (LHS) approach that uses rapid-cycle methods to integrate data and real-world experience to iteratively evaluate and adapt models of long COVID care.10 Our clinically identified and data-driven objective is to provide high value health care to patients with long COVID sequalae by creating a framework to learn about this novel condition and develop innovative care models. This article provides an overview of our emerging LHS approach to the study of long COVID care that is fostering innovation and adaptability within the VHA. We describe 3 aspects of our engagement approach central to LHS: the ongoing development of a long COVID CoP dedicated to iteratively informing the bidirectional cycle of data from practice to research, results of a broad environmental scan of VHA long COVID care, and results of a survey administered to CoP members to inform ongoing needs of the community and identify early successful outcomes from participation.

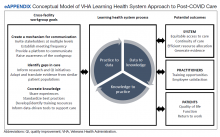

Learning Health System Approach

The VHA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States serving more than 9 million veterans.11 Since 2017, the VHA has articulated a vision to become an LHS that informs and improves patient-centered care through practice-based and data-driven research (eAppendix).12 During the early COVID-19 pandemic, an LHS approach in the VHA was critical to rapidly establishing a data infrastructure for disease surveillance, coordinating data-driven solutions, leveraging use of technology, collaborating across the globe to identify best practices, and implementing systematic responses (eg, policies, workforce adjustments).

Our long COVID CoP was developed as clinical observations and ongoing conversations with stakeholders (eg, veterans, health care practitioners [HCPs], leadership) identified a need to effectively identify and treat the growing number of veterans with long COVID. This clinical issue is compounded by the limited but emerging evidence on the clinical presentation of prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, treatment, and subsequent care pathways. The VHA’s efforts and lessons learned within the lens of an LHS are applicable to other systems confronting the complex identification and management of patients with persistent and encumbering long COVID symptoms. The VHA is building upon the LHS approach to proactively prepare for and address future clinical or public health challenges that require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient/family centeredness.11

Community of Practice

As of January 25, 2022, our workgroup consisted of 128 VHA employees representing 29 VHA medical centers. Members of the multidisciplinary workgroup have diverse backgrounds with HCPs from primary care (eg, physicians, nurse practitioners), rehabilitation (eg, physical therapists), specialty care (eg, pulmonologists, physiatrists), mental health (eg, psychologists), and complementary and integrated health/Whole Health services (eg, practitoners of services such as yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, acupuncture). Members also include clinical, operations, and research leadership at local, regional, and national VHA levels. Our first objective as a large, diverse group was to establish shared goals, which included: (1) determining efficient communication pathways; (2) identifying gaps in care or research; and (3) cocreating knowledge to provide solutions to identified gaps.

Communication Mechanisms

Our first goal was to create an efficient mechanism for cross-facility communication. The initial CoP was formed in April 2021 and the first virtual meeting focused on reaching a consensus regarding the best way to communicate and proceed. We agreed to convene weekly at a consistent time, created a standard agenda template, and elected a lead facilitator of meeting proceedings. In addition, a member of the CoP recorded and took extensive meeting notes, which were later distributed to the entire CoP to accommodate varying schedules and ability to attend live meetings. Approximately 20 to 30 participants attend the meetings in real-time.

To consolidate working documents, information, and resources in one location, we created a platform to communicate via a Microsoft Teams channel. All CoP members are given access to the folders and allowed to add to the growing library of resources. Resources include clinical assessment and note templates for electronic documentation of care, site-specific process maps, relevant literature on screening and interventions identified by practice members, and meeting notes along with the recordings. A chat feature alerts CoP members to questions posed by other members. Any resources or information shared on the chat discussion are curated by CoP leaders to disseminate to all members. Importantly, this platform allowed us to communicate efficiently within the VHA organization by creating a centralized space for documents and the ability to correspond with all or select members of the CoP. Additional VHA employees can easily be referred and request access.

To increase awareness of the CoP, expand reach, and diversify perspectives, every participant was encouraged to invite colleagues and stakeholders with interest or experience in long COVID care to join. While patients are not included in this CoP, we are working closely with the VHA user experience workgroup (many members overlap) that is gathering patient and caregiver perspectives on their COVID-19 experience and long COVID care. Concurrently, CoP members and leadership facilitate communication and set up formal collaborations with other non-VHA health care systems to create an intersystem network of collaboration for long COVID care. This approach further enhances the speed at which we can work together to share lessons learned and stay up-to-date on emerging evidence surrounding long COVID care.

Identifying Gaps in Care and Research

Our second goal was to identify gaps in care or knowledge to inform future research and quality improvement initiatives, while also creating a foundation to cocreate knowledge about safe, effective care management of the novel long COVID sequelae. To translate knowledge, we must first identify and understand the gaps between the current, best available evidence and current care practices or policies impacting that delivery.13 As such, the structured meeting agenda and facilitated meeting discussions focused on understanding current clinical decision making and the evidence base. We shared VHA evidence synthesis reports and living rapid reviews on complications following COVID-19 illness (ie, major organ damage and posthospitalization health care use) that provided an objective evidence base on common long COVID complications.14,15

Since long COVID is a novel condition, we drew from literature in similar patient populations and translated that information in the context of our current knowledge of this unique syndrome. For example, we discussed the predominant and persistent symptom of fatigue post-COVID.5 In particular, the CoP discussed challenges in identifying and treating post-COVID fatigue, which is often a vague symptom with multiple or interacting etiologies that require a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach. As such, we reviewed, adapted, and translated identification and treatment strategies from the literature on chronic fatigue syndrome to patients with post-COVID syndrome.16,17 We continue to work collaboratively and engage the appropriate stakeholders to provide input on the gaps to prioritize targeting.

Cocreate Knowledge

Our third goal was to cocreate knowledge regarding the care of patients with long COVID. To accomplish this, our structured meetings and communication pathways invited members to share experiences on the who (delivers and receives care), what (type of care or HCPs), when (identification of post-COVID and access), and how (eg, telehealth) of care to patients post-COVID. As part of the workgroup, we identified and shared resources on standardized, facility-level practices to reduce variability across the VHA system. These resources included intake/assessment forms, care processes, and batteries of tests/measures used for screening and assessment. The knowledge obtained from outside the CoP and cocreated within is being used to inform data-driven tools to support and evaluate care for patients with long COVID. As such, members of the workgroup are in the formative stages of participating in quality improvement innovation pilots to test technologies and processes designed to improve and validate long COVID care pathways. These technologies include screening tools, clinical decision support tools, and population health management technologies. In addition, we are developing a formal collaboration with the VHA Office of Research and Development to create standardized intake forms across VHA long COVID clinics to facilitate both clinical monitoring and research.

Surveys

The US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office collaborated with our workgroup to draft an initial set of survey questions designed to understand how each VHA facility defines, identifies, and provides care to veterans experiencing post-COVID sequalae. The 41-question survey was distributed through regional directors and chief medical officers at 139 VHA facilities in August 2021. One hundred nineteen responses (86%) were received. Sixteen facilities indicated they had established programs and 26 facilities were considering a program. Our CoP had representation from the 16 facilities with established programs indicating the deep and well-connected nature of our grassroots efforts to bring together stakeholders to learn as part of a CoP.

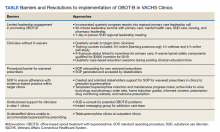

A separate, follow-up survey generated responses from 18 facilities and identified the need to capture evolving innovations and to develop smaller workstreams (eg, best practices, electronic documentation templates, pathway for referrals, veteran engagement, outcome measures). The survey not only exposed ongoing challenges to providing long COVID care, but importantly, outlined the ways in which CoP members were leveraging community knowledge and resources to inform innovations and processes of care changes at their specific sites. Fourteen of 18 facilities with long COVID programs in place explicitly identified the CoP as a resource they have found most beneficial when employing such innovations. Specific innovations reported included changes in care delivery, engagement in active outreach with veterans and local facility, and infrastructure development to sustain local long COVID clinics (Table).

Future Directions

Our CoP strives to contribute to an evidence base for long COVID care. At the system level, the CoP has the potential to impact access and continuity of care by identifying appropriate processes and ensuring that VHA patients receive outreach and an opportunity for post-COVID care. Comprehensive care requires input from HCP, clinical leadership, and operations levels. In this sense, our CoP provides an opportunity for diverse stakeholders to come together, discuss barriers to screening and delivering post-COVID care, and create an action plan to remove or lessen such barriers.18 Part of the process to remove barriers is to identify and support efficient resource allocation. Our CoP has worked to address issues in resource allocation (eg, space, personnel) for post-COVID care. For example, one facility is currently implementing interdisciplinary virtual post-COVID care. Another facility identified and restructured working assignments for psychologists who served in different capacities throughout the system to fill the need within the long COVID team.

At the HCP level, the CoP is currently developing workshops, media campaigns, written clinical resources, skills training, publications, and webinars/seminars with continuing medical education credits.19 The CoP may also provide learning and growth opportunities, such as clinical or VHA operational fellowships and research grants.

We are still in the formative stages of post-COVID care and future efforts will explore patient-centered outcomes. We are drawing on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidance for evaluating patients with long COVID symptoms and examining the feasibility within VHA, as well as patient perspectives on post-COVID sequalae, to ensure we are selecting assessments that measure patient-centered constructs.18

Conclusions

A VHA-wide LHS approach is identifying issues related to the identification, delivery, and evaluation of long COVID care. This long COVID CoP has developed an infrastructure for communication, identified gaps in care, and cocreated knowledge related to best current practices for post-COVID care. This work is contributing to systemwide LHS efforts dedicated to creating a culture of quality care and innovation and is a process that is transferrable to other areas of care in the VHA, as well as other health care systems. The LHS approach continues to be highly relevant as we persist through the COVID-19 pandemic and reimagine a postpandemic world.

Acknowledg

We thank all the members of the Veterans Health Administration long COVID Community of Practice who participate in the meetings and contribute to the sharing and spread of knowledge.

1. Sivan M, Halpin S, Hollingworth L, Snook N, Hickman K, Clifton I. Development of an integrated rehabilitation pathway for individuals recovering from COVID-19 in the community. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(8):jrm00089. doi:10.2340/16501977-2727

2. Understanding the long-term health effects of COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100586. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100586

3. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. Published online August 11, 2020:m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026

4. Iwua CJ, Iwu CD, Wiysonge CS. The occurrence of long COVID: a rapid review. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.65.27366

5. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

6. Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(8):1613-1620. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x

7. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

8. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259-264. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9

9. Ayoubkhani D, Bermingham C, Pouwels KB, et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. BMJ. 2022;377:e069676. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-069676

10. Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine, Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, eds. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. doi:10.17226/11903

11. Romanelli RJ, Azar KMJ, Sudat S, Hung D, Frosch DL, Pressman AR. Learning health system in crisis: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):171-176. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.10.004

12. Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

13. Kitson A, Straus SE. The knowledge-to-action cycle: identifying the gaps. CMAJ. 2010;182(2):E73-77. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081231

14. Greer N, Bart B, Billington C, et al. COVID-19 post-acute care major organ damage: a living rapid review. Updated September 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid-organ-damage.pdf

15. Sharpe JA, Burke C, Gordon AM, et al. COVID-19 post-hospitalization health care utilization: a living review. Updated February 2022. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid19-post-hosp.pdf

16. Bested AC, Marshall LM. Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30(4):223-249. doi:10.1515/reveh-2015-0026

17. Yancey JR, Thomas SM. Chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(8):741-746.

18. Kotter JP, Cohen DS. Change Leadership The Kotter Collection. Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

19. Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102-111. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA)—along with systems across the world—has spent the past 2 years continuously adapting to meet the emerging needs of persons infected with COVID-19. With the development of effective vaccines and global efforts to mitigate transmission, attention has now shifted to long COVID care as the need for further outpatient health care becomes increasingly apparent.1,2

Background

Multiple terms describe the lingering, multisystem sequelae of COVID-19 that last longer than 4 weeks: long COVID, postacute COVID-19 syndrome, post-COVID condition, postacute sequalae of COVID-19, and COVID long hauler.1,3 Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cough, sleep disorders, brain fog or cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, pain, and changes in taste or smell that impact a person’s functioning.4,5 The multisystem nature of the postacute course of COVID-19 necessitates an interdisciplinary approach to devise comprehensive and individualized care plans.6-9 Research is needed to better understand this postacute state (eg, prevalence, underlying effects, characteristics of those who experience long COVID) to establish and evaluate cost-effective treatment approaches.

Many patients who are experiencing symptoms beyond the acute course of COVID-19 have been referred to general outpatient clinics or home health, which may lack the capacity and knowledge of this novel disease to effectively manage complex long COVID cases.2,3 To address this growing need, clinicians and leadership across a variety of disciplines and settings in the VHA created a community of practice (CoP) to create a mechanism for cross-facility communication, identify gaps in long COVID care and research, and cocreate knowledge on best practices for care delivery.

In this spirit, we are embracing a learning health system (LHS) approach that uses rapid-cycle methods to integrate data and real-world experience to iteratively evaluate and adapt models of long COVID care.10 Our clinically identified and data-driven objective is to provide high value health care to patients with long COVID sequalae by creating a framework to learn about this novel condition and develop innovative care models. This article provides an overview of our emerging LHS approach to the study of long COVID care that is fostering innovation and adaptability within the VHA. We describe 3 aspects of our engagement approach central to LHS: the ongoing development of a long COVID CoP dedicated to iteratively informing the bidirectional cycle of data from practice to research, results of a broad environmental scan of VHA long COVID care, and results of a survey administered to CoP members to inform ongoing needs of the community and identify early successful outcomes from participation.

Learning Health System Approach

The VHA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States serving more than 9 million veterans.11 Since 2017, the VHA has articulated a vision to become an LHS that informs and improves patient-centered care through practice-based and data-driven research (eAppendix).12 During the early COVID-19 pandemic, an LHS approach in the VHA was critical to rapidly establishing a data infrastructure for disease surveillance, coordinating data-driven solutions, leveraging use of technology, collaborating across the globe to identify best practices, and implementing systematic responses (eg, policies, workforce adjustments).

Our long COVID CoP was developed as clinical observations and ongoing conversations with stakeholders (eg, veterans, health care practitioners [HCPs], leadership) identified a need to effectively identify and treat the growing number of veterans with long COVID. This clinical issue is compounded by the limited but emerging evidence on the clinical presentation of prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, treatment, and subsequent care pathways. The VHA’s efforts and lessons learned within the lens of an LHS are applicable to other systems confronting the complex identification and management of patients with persistent and encumbering long COVID symptoms. The VHA is building upon the LHS approach to proactively prepare for and address future clinical or public health challenges that require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient/family centeredness.11

Community of Practice

As of January 25, 2022, our workgroup consisted of 128 VHA employees representing 29 VHA medical centers. Members of the multidisciplinary workgroup have diverse backgrounds with HCPs from primary care (eg, physicians, nurse practitioners), rehabilitation (eg, physical therapists), specialty care (eg, pulmonologists, physiatrists), mental health (eg, psychologists), and complementary and integrated health/Whole Health services (eg, practitoners of services such as yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, acupuncture). Members also include clinical, operations, and research leadership at local, regional, and national VHA levels. Our first objective as a large, diverse group was to establish shared goals, which included: (1) determining efficient communication pathways; (2) identifying gaps in care or research; and (3) cocreating knowledge to provide solutions to identified gaps.

Communication Mechanisms

Our first goal was to create an efficient mechanism for cross-facility communication. The initial CoP was formed in April 2021 and the first virtual meeting focused on reaching a consensus regarding the best way to communicate and proceed. We agreed to convene weekly at a consistent time, created a standard agenda template, and elected a lead facilitator of meeting proceedings. In addition, a member of the CoP recorded and took extensive meeting notes, which were later distributed to the entire CoP to accommodate varying schedules and ability to attend live meetings. Approximately 20 to 30 participants attend the meetings in real-time.