User login

The Hospitalist only

SHM Forms Hospitalist IT Task Force

Do you speak geek? If you haven’t already, you may hear that phrase or something similar in the halls of your hospital or institution.

As hospitals face the challenge of implementing computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and electronic medical records (EMRs), many hospitals are turning to hospitalists to help guide them through the complex and daunting task of translating a critical initiative into an information technology (IT) success story. More and more, hospitalists are asked to play any number of roles in leading their institution to the IT Promised Land. Are you one of these people? Do you want to be? Not sure how to get started or where to turn for help? Look no further—SHM is here to help.

Late last year, SHM convened a small group of hospitalists with extensive IT experience. The meeting led to the formation of SHM’s new Hospitalist IT Task Force and a list of initiatives to help those of you interested in bridging the gap between the hospital and IT. In addition to this laundry list of ideas, the group described a set of roles a hospitalist can play in facilitating a CPOE or other IT project. Hospitalists involved in IT can act as:

Communicators: There are gaps in knowledge and understanding between physicians and IT staff. Medical staff members might not understand the IT vocabulary/processes, while the IT staff might not be familiar with medical vocabulary/processes. Hospitalists must translate the clinical needs of the hospital for the IT community when implementing programs like CPOE.

Champions: Every project needs a champion to have a chance at success. Knowledgeable hospitalists can communicate the value of IT initiatives to the hospital and drive these projects to a positive conclusion. Hospitalists understand the implications of transitioning from a paper to electronic environment and can engage the right people and resources to support these initiatives.

Experienced leaders (power users): There is a growing community of hospitalists who have implemented CPOE/EMR and other IT initiatives. They have been in the trenches. They know what works and what doesn’t, and they understand the pros and cons of different solutions. They are power users of medical IT and possess significant knowledge that can help others.

Reviewers: Each hospital has to select a technical solution that fits its administrative and clinical needs. The hospital will evaluate multiple options and selecting the appropriate solution. Hospitalists who play the roles of communicator, champion, and/or experienced leader can be valuable when solutions are being reviewed and evaluated.

Have you served in one of these roles? Would you like to get more involved in IT? SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is exploring different ways to assist our members. Potential initiatives include:

- Developing an online resource of articles, reference material, and Web sites that provide guidance and support related to IT in a hospital setting;

- Holding an open forum at Hospital Medicine 2008, SHM’s Annual Meeting from April 3-5 in San Diego, to discuss the roles, challenges, successes, and pitfalls encountered in IT initiatives; and

- Creating other educational vehicles for hospitalists working with IT in their hospital.

The success of an IT project depends on having the right people at the table. They are committed to success, they make open and honest contributions, and they work to align the needs of the organization with the capabilities of the technical solution by taking users’ needs into full consideration.

SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is working to develop the right solutions to help you improve your hospital or project. If you are one of our hospitalist IT users and have an opinion, idea, or experience you would like to share, we would like to hear from you. Contact the Hospitalist IT Task Force at [email protected]. TH

Do you speak geek? If you haven’t already, you may hear that phrase or something similar in the halls of your hospital or institution.

As hospitals face the challenge of implementing computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and electronic medical records (EMRs), many hospitals are turning to hospitalists to help guide them through the complex and daunting task of translating a critical initiative into an information technology (IT) success story. More and more, hospitalists are asked to play any number of roles in leading their institution to the IT Promised Land. Are you one of these people? Do you want to be? Not sure how to get started or where to turn for help? Look no further—SHM is here to help.

Late last year, SHM convened a small group of hospitalists with extensive IT experience. The meeting led to the formation of SHM’s new Hospitalist IT Task Force and a list of initiatives to help those of you interested in bridging the gap between the hospital and IT. In addition to this laundry list of ideas, the group described a set of roles a hospitalist can play in facilitating a CPOE or other IT project. Hospitalists involved in IT can act as:

Communicators: There are gaps in knowledge and understanding between physicians and IT staff. Medical staff members might not understand the IT vocabulary/processes, while the IT staff might not be familiar with medical vocabulary/processes. Hospitalists must translate the clinical needs of the hospital for the IT community when implementing programs like CPOE.

Champions: Every project needs a champion to have a chance at success. Knowledgeable hospitalists can communicate the value of IT initiatives to the hospital and drive these projects to a positive conclusion. Hospitalists understand the implications of transitioning from a paper to electronic environment and can engage the right people and resources to support these initiatives.

Experienced leaders (power users): There is a growing community of hospitalists who have implemented CPOE/EMR and other IT initiatives. They have been in the trenches. They know what works and what doesn’t, and they understand the pros and cons of different solutions. They are power users of medical IT and possess significant knowledge that can help others.

Reviewers: Each hospital has to select a technical solution that fits its administrative and clinical needs. The hospital will evaluate multiple options and selecting the appropriate solution. Hospitalists who play the roles of communicator, champion, and/or experienced leader can be valuable when solutions are being reviewed and evaluated.

Have you served in one of these roles? Would you like to get more involved in IT? SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is exploring different ways to assist our members. Potential initiatives include:

- Developing an online resource of articles, reference material, and Web sites that provide guidance and support related to IT in a hospital setting;

- Holding an open forum at Hospital Medicine 2008, SHM’s Annual Meeting from April 3-5 in San Diego, to discuss the roles, challenges, successes, and pitfalls encountered in IT initiatives; and

- Creating other educational vehicles for hospitalists working with IT in their hospital.

The success of an IT project depends on having the right people at the table. They are committed to success, they make open and honest contributions, and they work to align the needs of the organization with the capabilities of the technical solution by taking users’ needs into full consideration.

SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is working to develop the right solutions to help you improve your hospital or project. If you are one of our hospitalist IT users and have an opinion, idea, or experience you would like to share, we would like to hear from you. Contact the Hospitalist IT Task Force at [email protected]. TH

Do you speak geek? If you haven’t already, you may hear that phrase or something similar in the halls of your hospital or institution.

As hospitals face the challenge of implementing computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and electronic medical records (EMRs), many hospitals are turning to hospitalists to help guide them through the complex and daunting task of translating a critical initiative into an information technology (IT) success story. More and more, hospitalists are asked to play any number of roles in leading their institution to the IT Promised Land. Are you one of these people? Do you want to be? Not sure how to get started or where to turn for help? Look no further—SHM is here to help.

Late last year, SHM convened a small group of hospitalists with extensive IT experience. The meeting led to the formation of SHM’s new Hospitalist IT Task Force and a list of initiatives to help those of you interested in bridging the gap between the hospital and IT. In addition to this laundry list of ideas, the group described a set of roles a hospitalist can play in facilitating a CPOE or other IT project. Hospitalists involved in IT can act as:

Communicators: There are gaps in knowledge and understanding between physicians and IT staff. Medical staff members might not understand the IT vocabulary/processes, while the IT staff might not be familiar with medical vocabulary/processes. Hospitalists must translate the clinical needs of the hospital for the IT community when implementing programs like CPOE.

Champions: Every project needs a champion to have a chance at success. Knowledgeable hospitalists can communicate the value of IT initiatives to the hospital and drive these projects to a positive conclusion. Hospitalists understand the implications of transitioning from a paper to electronic environment and can engage the right people and resources to support these initiatives.

Experienced leaders (power users): There is a growing community of hospitalists who have implemented CPOE/EMR and other IT initiatives. They have been in the trenches. They know what works and what doesn’t, and they understand the pros and cons of different solutions. They are power users of medical IT and possess significant knowledge that can help others.

Reviewers: Each hospital has to select a technical solution that fits its administrative and clinical needs. The hospital will evaluate multiple options and selecting the appropriate solution. Hospitalists who play the roles of communicator, champion, and/or experienced leader can be valuable when solutions are being reviewed and evaluated.

Have you served in one of these roles? Would you like to get more involved in IT? SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is exploring different ways to assist our members. Potential initiatives include:

- Developing an online resource of articles, reference material, and Web sites that provide guidance and support related to IT in a hospital setting;

- Holding an open forum at Hospital Medicine 2008, SHM’s Annual Meeting from April 3-5 in San Diego, to discuss the roles, challenges, successes, and pitfalls encountered in IT initiatives; and

- Creating other educational vehicles for hospitalists working with IT in their hospital.

The success of an IT project depends on having the right people at the table. They are committed to success, they make open and honest contributions, and they work to align the needs of the organization with the capabilities of the technical solution by taking users’ needs into full consideration.

SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is working to develop the right solutions to help you improve your hospital or project. If you are one of our hospitalist IT users and have an opinion, idea, or experience you would like to share, we would like to hear from you. Contact the Hospitalist IT Task Force at [email protected]. TH

Inside SHM Quality Summit

In October, SHM embarked on the exciting endeavor of gathering leaders in education, research, standards, and clinical practice to begin developing ideas for furthering quality improvement initiatives in hospital medicine.

At the one-day Quality Summit in Chicago, participants were asked to consider and discuss their “big-picture” vision for improving quality care in hospitals. The meeting was led by Janet Nagamine, MD, chair of SHM’s Hospital Quality Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee, and Larry Wellikson, MD, the CEO of SHM.

As Dr. Nagamine opened the meeting, she expressed both the great excitement and angst that comes with undertaking such a huge initiative as creating a quality road map for SHM. Explaining that the day was to be devoted to determining vision, Dr. Wellikson further clarified that the goal of the summit was to set priorities and create strategies for moving forward.

Russell Holman, MD, SHM’s president, expressed appreciation for the wealth of experience and background of the attendees and encouraged participants to think as visionaries. Dr. Holman remarked on SHM’s devotion to a higher calling centered on looking at patient care as being inclusive and collaborative. The group was urged to put forth their best thinking to advance the quality and safety agenda.

Pre-work for the summit focused on bringing attendees up to speed with all SHM’s initiatives related to quality improvement. To understand the scope and breadth of work undertaken by SHM, each participant was asked to thoroughly examine the most updated Resource Rooms (Web-based, interactive learning tools) and to look at a comprehensive list of organizations with whom SHM is involved. Armed with a complete picture of what SHM has done, the group was expected to think about plans for progress.

Participants worked in large and small groups to generate themes to pursue in quality endeavors.

The group agreed on the benefit of expanding SHM’s resources in education and implementation.

A generally supported theme was that training in quality improvement should be offered in medical schools and residency and fellowship programs. Additionally, those who have experience with quality improvement can benefit from additional support with implementing projects. Discussions focused on SHM’s success with educational opportunities by creating multidisciplinary teams and focusing on putting principles into practice (e.g., the Venous Thromboembolism Prevention Collaborative).

Additionally, small groups identified the potential for SHM to further the national hospital quality and patient-safety agenda by expanding research efforts into national networks. SHM’s relationships with national organizations and leaders in the quality arena were a focal point of discussion. One small group was devoted entirely to developing an innovative care collaborative comprising national leaders in nursing, pharmacy, quality, and patient care.

One noteworthy conclusion attendees could draw at the end of the summit was that SHM functions with great excitement and initiative. From leadership to members, volunteers, and staff, SHM is not an organization that rests on accomplishments but one that uses progress as a launch pad for continued improvement.

The people making decisions about quality endeavors to pursue have front-line experience and are in touch with what will improve patient care.

It was evident that while no one person or organization has all the answers, SHM is willing to do what it takes in terms of trying new things and forging new relationships.

Hospital Medicine Fast Facts 10 Key Metrics for Monitoring Hospitalist Performance

- Volume data: Measurements indicating “volume of services” provided by a hospitalist group or by individual hospitalists. Volume data, in general terms, are counts of services performed by hospitalists.

- Case mix: A tool used to characterize the clinical complexity of the patients treated by the hospital medicine group (and comparison groups). The goal of case mix is to allow “apples to apples” comparisons.

- Patient satisfaction: A survey-based measure often considered an element of quality outcomes. Surveys, often designed and administered by vendors, are typically designed to measure a patient’s perception of his or her overall hospital experience.

- Length of stay: The number of days of inpatient care utilized by a patient or a group of patients.

- Hospital cost: Measures the money expended by a hospital to care for its patients, most often expressed as cost per unit of service (e.g., cost per patient day or cost per discharge).

- Productivity measures: Objective qualifications of physician productivity (e.g., encounters, Relative Value Units).

- Provider satisfaction: The most common metric addresses referring-physician satisfaction and uses a survey to measure perceptions of their overall experience with the hospital medicine program (e.g., the care of their patient and interactions with the hospitalists). Other providers could be monitored for satisfaction, including specialists and nurses.

- Mortality: A measure of the number of patient deaths over a defined time period. Typically, the observed mortality metric is compared with expected mortality.

- Readmission rate: Describes how often patients admitted to the hospital by a physician or practice are admitted again, within a defined period following discharge.

- Joint Commission Core Measures: These are evidence-based, standardized “core” measures to track the performance of hospitals in providing quality healthcare. Four diagnoses are included: acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, community-acquired pneumonia, and pregnancy and related conditions.

To download “Measuring Hospitalist Performance: Metrics, Reports, and Dashboards.” Visit the “SHM Initiatives” section at www.hospitalmedicine.org.

In October, SHM embarked on the exciting endeavor of gathering leaders in education, research, standards, and clinical practice to begin developing ideas for furthering quality improvement initiatives in hospital medicine.

At the one-day Quality Summit in Chicago, participants were asked to consider and discuss their “big-picture” vision for improving quality care in hospitals. The meeting was led by Janet Nagamine, MD, chair of SHM’s Hospital Quality Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee, and Larry Wellikson, MD, the CEO of SHM.

As Dr. Nagamine opened the meeting, she expressed both the great excitement and angst that comes with undertaking such a huge initiative as creating a quality road map for SHM. Explaining that the day was to be devoted to determining vision, Dr. Wellikson further clarified that the goal of the summit was to set priorities and create strategies for moving forward.

Russell Holman, MD, SHM’s president, expressed appreciation for the wealth of experience and background of the attendees and encouraged participants to think as visionaries. Dr. Holman remarked on SHM’s devotion to a higher calling centered on looking at patient care as being inclusive and collaborative. The group was urged to put forth their best thinking to advance the quality and safety agenda.

Pre-work for the summit focused on bringing attendees up to speed with all SHM’s initiatives related to quality improvement. To understand the scope and breadth of work undertaken by SHM, each participant was asked to thoroughly examine the most updated Resource Rooms (Web-based, interactive learning tools) and to look at a comprehensive list of organizations with whom SHM is involved. Armed with a complete picture of what SHM has done, the group was expected to think about plans for progress.

Participants worked in large and small groups to generate themes to pursue in quality endeavors.

The group agreed on the benefit of expanding SHM’s resources in education and implementation.

A generally supported theme was that training in quality improvement should be offered in medical schools and residency and fellowship programs. Additionally, those who have experience with quality improvement can benefit from additional support with implementing projects. Discussions focused on SHM’s success with educational opportunities by creating multidisciplinary teams and focusing on putting principles into practice (e.g., the Venous Thromboembolism Prevention Collaborative).

Additionally, small groups identified the potential for SHM to further the national hospital quality and patient-safety agenda by expanding research efforts into national networks. SHM’s relationships with national organizations and leaders in the quality arena were a focal point of discussion. One small group was devoted entirely to developing an innovative care collaborative comprising national leaders in nursing, pharmacy, quality, and patient care.

One noteworthy conclusion attendees could draw at the end of the summit was that SHM functions with great excitement and initiative. From leadership to members, volunteers, and staff, SHM is not an organization that rests on accomplishments but one that uses progress as a launch pad for continued improvement.

The people making decisions about quality endeavors to pursue have front-line experience and are in touch with what will improve patient care.

It was evident that while no one person or organization has all the answers, SHM is willing to do what it takes in terms of trying new things and forging new relationships.

Hospital Medicine Fast Facts 10 Key Metrics for Monitoring Hospitalist Performance

- Volume data: Measurements indicating “volume of services” provided by a hospitalist group or by individual hospitalists. Volume data, in general terms, are counts of services performed by hospitalists.

- Case mix: A tool used to characterize the clinical complexity of the patients treated by the hospital medicine group (and comparison groups). The goal of case mix is to allow “apples to apples” comparisons.

- Patient satisfaction: A survey-based measure often considered an element of quality outcomes. Surveys, often designed and administered by vendors, are typically designed to measure a patient’s perception of his or her overall hospital experience.

- Length of stay: The number of days of inpatient care utilized by a patient or a group of patients.

- Hospital cost: Measures the money expended by a hospital to care for its patients, most often expressed as cost per unit of service (e.g., cost per patient day or cost per discharge).

- Productivity measures: Objective qualifications of physician productivity (e.g., encounters, Relative Value Units).

- Provider satisfaction: The most common metric addresses referring-physician satisfaction and uses a survey to measure perceptions of their overall experience with the hospital medicine program (e.g., the care of their patient and interactions with the hospitalists). Other providers could be monitored for satisfaction, including specialists and nurses.

- Mortality: A measure of the number of patient deaths over a defined time period. Typically, the observed mortality metric is compared with expected mortality.

- Readmission rate: Describes how often patients admitted to the hospital by a physician or practice are admitted again, within a defined period following discharge.

- Joint Commission Core Measures: These are evidence-based, standardized “core” measures to track the performance of hospitals in providing quality healthcare. Four diagnoses are included: acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, community-acquired pneumonia, and pregnancy and related conditions.

To download “Measuring Hospitalist Performance: Metrics, Reports, and Dashboards.” Visit the “SHM Initiatives” section at www.hospitalmedicine.org.

In October, SHM embarked on the exciting endeavor of gathering leaders in education, research, standards, and clinical practice to begin developing ideas for furthering quality improvement initiatives in hospital medicine.

At the one-day Quality Summit in Chicago, participants were asked to consider and discuss their “big-picture” vision for improving quality care in hospitals. The meeting was led by Janet Nagamine, MD, chair of SHM’s Hospital Quality Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee, and Larry Wellikson, MD, the CEO of SHM.

As Dr. Nagamine opened the meeting, she expressed both the great excitement and angst that comes with undertaking such a huge initiative as creating a quality road map for SHM. Explaining that the day was to be devoted to determining vision, Dr. Wellikson further clarified that the goal of the summit was to set priorities and create strategies for moving forward.

Russell Holman, MD, SHM’s president, expressed appreciation for the wealth of experience and background of the attendees and encouraged participants to think as visionaries. Dr. Holman remarked on SHM’s devotion to a higher calling centered on looking at patient care as being inclusive and collaborative. The group was urged to put forth their best thinking to advance the quality and safety agenda.

Pre-work for the summit focused on bringing attendees up to speed with all SHM’s initiatives related to quality improvement. To understand the scope and breadth of work undertaken by SHM, each participant was asked to thoroughly examine the most updated Resource Rooms (Web-based, interactive learning tools) and to look at a comprehensive list of organizations with whom SHM is involved. Armed with a complete picture of what SHM has done, the group was expected to think about plans for progress.

Participants worked in large and small groups to generate themes to pursue in quality endeavors.

The group agreed on the benefit of expanding SHM’s resources in education and implementation.

A generally supported theme was that training in quality improvement should be offered in medical schools and residency and fellowship programs. Additionally, those who have experience with quality improvement can benefit from additional support with implementing projects. Discussions focused on SHM’s success with educational opportunities by creating multidisciplinary teams and focusing on putting principles into practice (e.g., the Venous Thromboembolism Prevention Collaborative).

Additionally, small groups identified the potential for SHM to further the national hospital quality and patient-safety agenda by expanding research efforts into national networks. SHM’s relationships with national organizations and leaders in the quality arena were a focal point of discussion. One small group was devoted entirely to developing an innovative care collaborative comprising national leaders in nursing, pharmacy, quality, and patient care.

One noteworthy conclusion attendees could draw at the end of the summit was that SHM functions with great excitement and initiative. From leadership to members, volunteers, and staff, SHM is not an organization that rests on accomplishments but one that uses progress as a launch pad for continued improvement.

The people making decisions about quality endeavors to pursue have front-line experience and are in touch with what will improve patient care.

It was evident that while no one person or organization has all the answers, SHM is willing to do what it takes in terms of trying new things and forging new relationships.

Hospital Medicine Fast Facts 10 Key Metrics for Monitoring Hospitalist Performance

- Volume data: Measurements indicating “volume of services” provided by a hospitalist group or by individual hospitalists. Volume data, in general terms, are counts of services performed by hospitalists.

- Case mix: A tool used to characterize the clinical complexity of the patients treated by the hospital medicine group (and comparison groups). The goal of case mix is to allow “apples to apples” comparisons.

- Patient satisfaction: A survey-based measure often considered an element of quality outcomes. Surveys, often designed and administered by vendors, are typically designed to measure a patient’s perception of his or her overall hospital experience.

- Length of stay: The number of days of inpatient care utilized by a patient or a group of patients.

- Hospital cost: Measures the money expended by a hospital to care for its patients, most often expressed as cost per unit of service (e.g., cost per patient day or cost per discharge).

- Productivity measures: Objective qualifications of physician productivity (e.g., encounters, Relative Value Units).

- Provider satisfaction: The most common metric addresses referring-physician satisfaction and uses a survey to measure perceptions of their overall experience with the hospital medicine program (e.g., the care of their patient and interactions with the hospitalists). Other providers could be monitored for satisfaction, including specialists and nurses.

- Mortality: A measure of the number of patient deaths over a defined time period. Typically, the observed mortality metric is compared with expected mortality.

- Readmission rate: Describes how often patients admitted to the hospital by a physician or practice are admitted again, within a defined period following discharge.

- Joint Commission Core Measures: These are evidence-based, standardized “core” measures to track the performance of hospitals in providing quality healthcare. Four diagnoses are included: acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, community-acquired pneumonia, and pregnancy and related conditions.

To download “Measuring Hospitalist Performance: Metrics, Reports, and Dashboards.” Visit the “SHM Initiatives” section at www.hospitalmedicine.org.

What pre-operative cardiac evaluation of patients undergoing intermediate-risk surgery is most appropriate?

Case

The orthopedic service asks you to evaluate a 76-year-old woman with a hip fracture. She has diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia but no known coronary artery disease (CAD). She says she can carry a bag of groceries up one flight of stairs without chest symptoms.

Her physical exam is significant only for a shortened, internally rotated right hip. Her blood pressure is 160/88 mm/hg, her pulse is 75 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 16 breaths a minute with an oxygen saturation of 95% on one liter. Her creatinine is 1.2 mg/dL, and her fasting glucose is 106 mg/dL. An electrocardiogram reveals normal sinus rhythm without evidence of prior myocardial infarction (MI).

Her medications are lisinopril, atorvastatin, aspirin, fluoxetine, and diazepam. She is scheduled for the operating room tomorrow. What is the best strategy to evaluate and minimize her perioperative cardiac risk, and does it include a beta-blocker?

Overview

There are many ways to identify patients at risk for perioperative cardiac complications—but few simple, safe, evidence-based means of mitigating risk.1

Over the past 10 years, the general approach has been that preoperative revascularization is beneficial in a limited number of clinical scenarios. Further, beta-blockers reduce risk in nearly all other high- and intermediate-risk patients. Unfortunately, routine perioperative administration of beta-blockers to intermediate-risk patients is not supported by trial evidence and may expose these patients to increased risk of adverse outcomes—including death and stroke.

Review of the Data

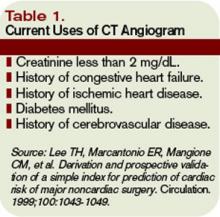

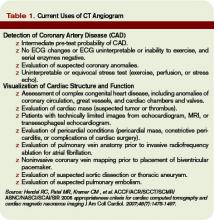

Intermediate-risk patients: Inter-mediate risk patients have recently been redefined as patients with a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of two or one (See Table 1, p. 27).2,3 Older guidelines suggested noninvasive testing for such patients if they had poor functional capacity (less than four metabolic equivalents [METS]) and were undergoing intermediate-risk surgery, including orthopedic, peritoneal, and thoracic procedures.

Unfortunately, this situation is common, leading to frequent testing and unclear benefit to patients. Omission of a noninvasive evaluation in intermediate-risk orthopedic surgery patients is not associated with an increase in perioperative cardiac events.4 Most events occur in patients who did not meet criteria for preoperative testing.

The 2007 ACC/AHA Guidelines for Perioperative Evaluation and Care address this by recommending noninvasive testing only “if it will change management.” But they offer little guidance in unclear clinical situations, such as the urgent hip-fracture repair needed by our patient.

Preoperative revascularization: While it makes intuitive sense that preoperative revascularization of high-risk patients would decrease their risk of perioperative cardiac complications, evidence countering this idea is nearly definitive. In a study by McFalls, revascularization prior to major vascular surgery did not decrease the risk of perioperative MI or 30-day mortality; however, it delayed the surgical procedure, even in patients with high-risk noninvasive test results.5,6 It is generally accepted that if these high-risk patients can safely undergo major vascular surgery without revascularization, a lower-risk patient such as ours can do so at even lower risk.

In these trials, revascularization occurred in addition to medical management of coronary disease, including aspirin, statin, and—particularly in the study by Poldermans,6 where beta-blockers were started and titrated well before surgery—beta-blocker therapy.

Patients with active cardiac symptoms or signs or uncharacterized anginal symptoms should have elective surgery delayed. However, delay is rarely an option for the hospitalist, who is typically asked to address a patient’s risk shortly before urgent or emergent surgery. These difficult situations require one to weigh the cardiac risk of surgery in a patient who is not optimized versus the risk of delaying surgery to address the more urgent cardiac situation.

Timing of perioperative percutaneous intervention: For patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) or coronary lesions, the interval between percutaneous revascularization (via stent or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA]) and surgery affects rates of postoperative cardiac events.7

The recommended interval between stent placement and noncardiac surgery for patients receiving bare-metal and drug-eluting stents is six weeks and one year, respectively.8 Surgery within two weeks of stent placement can carry mortality rates as high as 40%, and this risk appears to decrease out to one year.9,10 If a new stent is in place, any potential benefit appears to be offset by the increased risk of in-stent thrombosis with subsequent MI and possible death. PTCA may not be a safe alternative, although some recommend using PTCA if the patient has unstable cardiac symptoms and needs urgent/emergent surgery.11

Perioperative discontinuation of dual antiplatelet agents (e.g., clopidogrel and aspirin) is common and appears to increase thrombosis risk. This presents a challenge when patients with recent stent placement present for urgent surgery. Minimizing the interruption of dual antiplatelet therapy is the most important intervention a hospitalist can perform. Interruption is associated with increased risk of stent thrombosis, MI, and death. If clopidogrel must be discontinued in the perioperative period, continuation of aspirin is recommended and intravenous glycoprotein 2b/3a inhibitors can be considered.12

Perioperative beta-blocker: Studies on the outcomes of perioperative beta blockade strongly suggested benefits initially. But a number of randomized trials in the past three years have not shown a positive effect.

In a landmark study published in 1996, Mangano showed that initiation of beta blockade just prior to surgery reduced perioperative MI and cardiac death in a mixed surgical population.13 Similar findings were seen with initiation of beta-blocker one month prior to vascular surgery.14 Additionally, higher doses of beta-blocker and lower heart rates in the perioperative period seem to be associated with decreased troponin release.15 Finally, perioperative beta blockade was associated with decreased mortality in high-risk patients (RCRI of three or greater), but higher mortality in lower-risk patients (e.g., RCRI of zero or one).16

More recent data reveal less benefit for perioperative beta blockade. Yang, et al., suggested that initiation of beta-blockers just prior to surgery did not decrease postoperative cardiac complications in vascular surgery patients.17 Similar results were found in a cohort of diabetic patients undergoing major surgery.18 A subsequent meta-analysis concluded that, in the aggregate, perioperative beta blockade was neither beneficial nor harmful.19

Further data have shown increased mortality with perioperative beta blockade in low-risk patients. Most recently, an abstract from the largest randomized controlled trial to date, the POISE study, suggested that preoperative beta blockade decreased MI and cardiac death, but increased the risk of stroke and produced higher overall mortality.20

It is challenging to reconcile this newer evidence with the previous data. While it seems intuitive that blunting the catecholamine response would minimize cardiac workload and therefore decrease perioperative infarcts, surgical patients are also at risk for poor pain control, sepsis, hypovolemia, and venous thromboembolism. Beta blockade can obscure their clinical manifestations, delaying diagnosis or complicating therapy. Inconsistencies among studies and published guidelines make them difficult to apply broadly, particularly with the intermediate-risk patient. Finally, perioperative beta blockade is poorly defined in terms of timing of initiation, target heart rate, and duration of postoperative use.

Until more definitive trial data are published, it seems most prudent to continue beta-blockers in patients already using them. Start them as far in advance of surgery as possible in patients with high-risk features (such as a positive stress test). After surgery, pay close attention to volume status, pain, signs of sepsis, or other noncardiac complications.

Back to the Case

As per the 2007 ACC/AHA guidelines, this patient with one clinical risk factor (diabetes) and good functional capacity can proceed to the operating room without further intervention. While it is likely a patient with diabetes and hyperlipidemia has some degree of CAD, including possible vulnerable plaques, the best medical evidence offers little to decrease her operative cardiac risk. Perioperative beta blockade is not indicated at her level of risk (RCRI of one) given the inconsistent benefits and possible harm to patients like this seen in trials to date.

If she were limited in terms of functional capacity (i.e., less than four METS), the 2007 ACC/AHA algorithm suggests preoperative noninvasive testing “if it would change management.”

How might a positive stress test change management in this case? Revascularization with stenting in close proximity to noncardiac surgery is not safe, and there appears to be no benefit to preoperative revascularization before high-risk vascular surgery. However, ischemia on preoperative testing is an indication for a beta-blocker. A brief delay in her surgery to allow dose titration and use of telemetry monitoring after surgery would increase the safety of beta-blockers after surgery. How long to continue beta-blockers is an open question, but at least 30 days would seem adequate, tapering rather than abruptly discontinuing the dose. TH

Dr. Carter is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver in the Section of Hospital Medicine, where he directs the Medicine Consult Service. Dr. Auerbach is an associate professor of medicine in residence, associate director of the general medicine research fellowship, director of quality improvement for the UCSF Department of Medicine, and director of the surgical care Improvement program at UCSF. His research interests include perioperative medicine and quality improvement.

References

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1043-1049.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al. ACC/AHA Guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary. Circulation 2002;105:1257-1267.

- Fleischer LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for noncardiac surgery: executive summary. Circulation. 2007;116:1971-1996.

- Salerno SM, Carlson DW, Soh EK, et al. Impact of perioperative cardiac assessment guidelines on management of orthopedic surgery patients. Am J Med. 2007;120(2):185.

- McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2795-2804.

- Poldermans D, Schouten O, Vidakovic R, et al. A clinical randomized trial to evaluate the safety of a noninvasive approach in high-risk patients undergoing major vascular surgery: The DECREASE-V Pilot Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(17):1763-1769.

- Wilson, SH, Fasseas P, Orford JL, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery in the two months following coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(2):234-240.

- Grines, CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents. Circulation. 2007; 115:813-818.

- Kaluza GL, Joseph J, Lee JR, et al. Catastrophic outcomes of noncardiac surgery soon after coronary stenting. Am J Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(5):1288-1294.

- Schouten O, Bax JJ, Damen J, et al. Coronary stent placement immediately before non cardiac surgery: a potential risk? Anesthesiology 106(5);2007:1067.

- Leibowitz D, Cohen M, Planer D, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk of noncardiac surgery following coronary angioplasty with versus without stenting. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(8):1188-1191.

- Auerbach A, Goldman L. Assessing and reducing the cardiac risk of noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2006;113:1361-1376.

- Mangano DT, Layug EL, Wallace A, et al. Effect of atenolol on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(23):1713-1720.

- Poldermans D, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(24):1789-1794.

- Feringa HH, Bax JJ, Boersma E, et al. High dose b-blockers and tight heart rate control reduce myocardial ischemia and troponin T release in vascular surgery patients. Circulation. 2006;114(supp):I344.

- Lindenauer PK Pekow P, Wang K, et al. Perioperative beta-blocker therapy and mortality after major noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):349-361.

- Yang H, Raymer K, Butler R, et al. The effects of perioperative beta blockade: results of the Metoprolol after Vascular Surgery (MaVS) study, a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2006;152(5):983-990.

- Juul AB, Wetterslev J, Gluud C, et al. Effect of perioperative ß blockade in patients with diabetes undergoing major non-cardiac surgery: randomized placebo controlled, blinded multicentre trial. BMJ. 2006 June;332:1482.

- Devereaux PJ, Beattie WS, Choi PT, et al. How strong is the evidence for the use of perioperative ß blockers in noncardiac surgery? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;331:313.

- Devereaux PJ. POISE Abstract. American Heart Association Annual Scientific Session, Orlando, Fla., November 2007.

Case

The orthopedic service asks you to evaluate a 76-year-old woman with a hip fracture. She has diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia but no known coronary artery disease (CAD). She says she can carry a bag of groceries up one flight of stairs without chest symptoms.

Her physical exam is significant only for a shortened, internally rotated right hip. Her blood pressure is 160/88 mm/hg, her pulse is 75 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 16 breaths a minute with an oxygen saturation of 95% on one liter. Her creatinine is 1.2 mg/dL, and her fasting glucose is 106 mg/dL. An electrocardiogram reveals normal sinus rhythm without evidence of prior myocardial infarction (MI).

Her medications are lisinopril, atorvastatin, aspirin, fluoxetine, and diazepam. She is scheduled for the operating room tomorrow. What is the best strategy to evaluate and minimize her perioperative cardiac risk, and does it include a beta-blocker?

Overview

There are many ways to identify patients at risk for perioperative cardiac complications—but few simple, safe, evidence-based means of mitigating risk.1

Over the past 10 years, the general approach has been that preoperative revascularization is beneficial in a limited number of clinical scenarios. Further, beta-blockers reduce risk in nearly all other high- and intermediate-risk patients. Unfortunately, routine perioperative administration of beta-blockers to intermediate-risk patients is not supported by trial evidence and may expose these patients to increased risk of adverse outcomes—including death and stroke.

Review of the Data

Intermediate-risk patients: Inter-mediate risk patients have recently been redefined as patients with a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of two or one (See Table 1, p. 27).2,3 Older guidelines suggested noninvasive testing for such patients if they had poor functional capacity (less than four metabolic equivalents [METS]) and were undergoing intermediate-risk surgery, including orthopedic, peritoneal, and thoracic procedures.

Unfortunately, this situation is common, leading to frequent testing and unclear benefit to patients. Omission of a noninvasive evaluation in intermediate-risk orthopedic surgery patients is not associated with an increase in perioperative cardiac events.4 Most events occur in patients who did not meet criteria for preoperative testing.

The 2007 ACC/AHA Guidelines for Perioperative Evaluation and Care address this by recommending noninvasive testing only “if it will change management.” But they offer little guidance in unclear clinical situations, such as the urgent hip-fracture repair needed by our patient.

Preoperative revascularization: While it makes intuitive sense that preoperative revascularization of high-risk patients would decrease their risk of perioperative cardiac complications, evidence countering this idea is nearly definitive. In a study by McFalls, revascularization prior to major vascular surgery did not decrease the risk of perioperative MI or 30-day mortality; however, it delayed the surgical procedure, even in patients with high-risk noninvasive test results.5,6 It is generally accepted that if these high-risk patients can safely undergo major vascular surgery without revascularization, a lower-risk patient such as ours can do so at even lower risk.

In these trials, revascularization occurred in addition to medical management of coronary disease, including aspirin, statin, and—particularly in the study by Poldermans,6 where beta-blockers were started and titrated well before surgery—beta-blocker therapy.

Patients with active cardiac symptoms or signs or uncharacterized anginal symptoms should have elective surgery delayed. However, delay is rarely an option for the hospitalist, who is typically asked to address a patient’s risk shortly before urgent or emergent surgery. These difficult situations require one to weigh the cardiac risk of surgery in a patient who is not optimized versus the risk of delaying surgery to address the more urgent cardiac situation.

Timing of perioperative percutaneous intervention: For patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) or coronary lesions, the interval between percutaneous revascularization (via stent or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA]) and surgery affects rates of postoperative cardiac events.7

The recommended interval between stent placement and noncardiac surgery for patients receiving bare-metal and drug-eluting stents is six weeks and one year, respectively.8 Surgery within two weeks of stent placement can carry mortality rates as high as 40%, and this risk appears to decrease out to one year.9,10 If a new stent is in place, any potential benefit appears to be offset by the increased risk of in-stent thrombosis with subsequent MI and possible death. PTCA may not be a safe alternative, although some recommend using PTCA if the patient has unstable cardiac symptoms and needs urgent/emergent surgery.11

Perioperative discontinuation of dual antiplatelet agents (e.g., clopidogrel and aspirin) is common and appears to increase thrombosis risk. This presents a challenge when patients with recent stent placement present for urgent surgery. Minimizing the interruption of dual antiplatelet therapy is the most important intervention a hospitalist can perform. Interruption is associated with increased risk of stent thrombosis, MI, and death. If clopidogrel must be discontinued in the perioperative period, continuation of aspirin is recommended and intravenous glycoprotein 2b/3a inhibitors can be considered.12

Perioperative beta-blocker: Studies on the outcomes of perioperative beta blockade strongly suggested benefits initially. But a number of randomized trials in the past three years have not shown a positive effect.

In a landmark study published in 1996, Mangano showed that initiation of beta blockade just prior to surgery reduced perioperative MI and cardiac death in a mixed surgical population.13 Similar findings were seen with initiation of beta-blocker one month prior to vascular surgery.14 Additionally, higher doses of beta-blocker and lower heart rates in the perioperative period seem to be associated with decreased troponin release.15 Finally, perioperative beta blockade was associated with decreased mortality in high-risk patients (RCRI of three or greater), but higher mortality in lower-risk patients (e.g., RCRI of zero or one).16

More recent data reveal less benefit for perioperative beta blockade. Yang, et al., suggested that initiation of beta-blockers just prior to surgery did not decrease postoperative cardiac complications in vascular surgery patients.17 Similar results were found in a cohort of diabetic patients undergoing major surgery.18 A subsequent meta-analysis concluded that, in the aggregate, perioperative beta blockade was neither beneficial nor harmful.19

Further data have shown increased mortality with perioperative beta blockade in low-risk patients. Most recently, an abstract from the largest randomized controlled trial to date, the POISE study, suggested that preoperative beta blockade decreased MI and cardiac death, but increased the risk of stroke and produced higher overall mortality.20

It is challenging to reconcile this newer evidence with the previous data. While it seems intuitive that blunting the catecholamine response would minimize cardiac workload and therefore decrease perioperative infarcts, surgical patients are also at risk for poor pain control, sepsis, hypovolemia, and venous thromboembolism. Beta blockade can obscure their clinical manifestations, delaying diagnosis or complicating therapy. Inconsistencies among studies and published guidelines make them difficult to apply broadly, particularly with the intermediate-risk patient. Finally, perioperative beta blockade is poorly defined in terms of timing of initiation, target heart rate, and duration of postoperative use.

Until more definitive trial data are published, it seems most prudent to continue beta-blockers in patients already using them. Start them as far in advance of surgery as possible in patients with high-risk features (such as a positive stress test). After surgery, pay close attention to volume status, pain, signs of sepsis, or other noncardiac complications.

Back to the Case

As per the 2007 ACC/AHA guidelines, this patient with one clinical risk factor (diabetes) and good functional capacity can proceed to the operating room without further intervention. While it is likely a patient with diabetes and hyperlipidemia has some degree of CAD, including possible vulnerable plaques, the best medical evidence offers little to decrease her operative cardiac risk. Perioperative beta blockade is not indicated at her level of risk (RCRI of one) given the inconsistent benefits and possible harm to patients like this seen in trials to date.

If she were limited in terms of functional capacity (i.e., less than four METS), the 2007 ACC/AHA algorithm suggests preoperative noninvasive testing “if it would change management.”

How might a positive stress test change management in this case? Revascularization with stenting in close proximity to noncardiac surgery is not safe, and there appears to be no benefit to preoperative revascularization before high-risk vascular surgery. However, ischemia on preoperative testing is an indication for a beta-blocker. A brief delay in her surgery to allow dose titration and use of telemetry monitoring after surgery would increase the safety of beta-blockers after surgery. How long to continue beta-blockers is an open question, but at least 30 days would seem adequate, tapering rather than abruptly discontinuing the dose. TH

Dr. Carter is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver in the Section of Hospital Medicine, where he directs the Medicine Consult Service. Dr. Auerbach is an associate professor of medicine in residence, associate director of the general medicine research fellowship, director of quality improvement for the UCSF Department of Medicine, and director of the surgical care Improvement program at UCSF. His research interests include perioperative medicine and quality improvement.

References

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1043-1049.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al. ACC/AHA Guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary. Circulation 2002;105:1257-1267.

- Fleischer LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for noncardiac surgery: executive summary. Circulation. 2007;116:1971-1996.

- Salerno SM, Carlson DW, Soh EK, et al. Impact of perioperative cardiac assessment guidelines on management of orthopedic surgery patients. Am J Med. 2007;120(2):185.

- McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2795-2804.

- Poldermans D, Schouten O, Vidakovic R, et al. A clinical randomized trial to evaluate the safety of a noninvasive approach in high-risk patients undergoing major vascular surgery: The DECREASE-V Pilot Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(17):1763-1769.

- Wilson, SH, Fasseas P, Orford JL, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery in the two months following coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(2):234-240.

- Grines, CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents. Circulation. 2007; 115:813-818.

- Kaluza GL, Joseph J, Lee JR, et al. Catastrophic outcomes of noncardiac surgery soon after coronary stenting. Am J Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(5):1288-1294.

- Schouten O, Bax JJ, Damen J, et al. Coronary stent placement immediately before non cardiac surgery: a potential risk? Anesthesiology 106(5);2007:1067.

- Leibowitz D, Cohen M, Planer D, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk of noncardiac surgery following coronary angioplasty with versus without stenting. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(8):1188-1191.

- Auerbach A, Goldman L. Assessing and reducing the cardiac risk of noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2006;113:1361-1376.

- Mangano DT, Layug EL, Wallace A, et al. Effect of atenolol on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(23):1713-1720.

- Poldermans D, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(24):1789-1794.

- Feringa HH, Bax JJ, Boersma E, et al. High dose b-blockers and tight heart rate control reduce myocardial ischemia and troponin T release in vascular surgery patients. Circulation. 2006;114(supp):I344.

- Lindenauer PK Pekow P, Wang K, et al. Perioperative beta-blocker therapy and mortality after major noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):349-361.

- Yang H, Raymer K, Butler R, et al. The effects of perioperative beta blockade: results of the Metoprolol after Vascular Surgery (MaVS) study, a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2006;152(5):983-990.

- Juul AB, Wetterslev J, Gluud C, et al. Effect of perioperative ß blockade in patients with diabetes undergoing major non-cardiac surgery: randomized placebo controlled, blinded multicentre trial. BMJ. 2006 June;332:1482.

- Devereaux PJ, Beattie WS, Choi PT, et al. How strong is the evidence for the use of perioperative ß blockers in noncardiac surgery? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;331:313.

- Devereaux PJ. POISE Abstract. American Heart Association Annual Scientific Session, Orlando, Fla., November 2007.

Case

The orthopedic service asks you to evaluate a 76-year-old woman with a hip fracture. She has diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia but no known coronary artery disease (CAD). She says she can carry a bag of groceries up one flight of stairs without chest symptoms.

Her physical exam is significant only for a shortened, internally rotated right hip. Her blood pressure is 160/88 mm/hg, her pulse is 75 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 16 breaths a minute with an oxygen saturation of 95% on one liter. Her creatinine is 1.2 mg/dL, and her fasting glucose is 106 mg/dL. An electrocardiogram reveals normal sinus rhythm without evidence of prior myocardial infarction (MI).

Her medications are lisinopril, atorvastatin, aspirin, fluoxetine, and diazepam. She is scheduled for the operating room tomorrow. What is the best strategy to evaluate and minimize her perioperative cardiac risk, and does it include a beta-blocker?

Overview

There are many ways to identify patients at risk for perioperative cardiac complications—but few simple, safe, evidence-based means of mitigating risk.1

Over the past 10 years, the general approach has been that preoperative revascularization is beneficial in a limited number of clinical scenarios. Further, beta-blockers reduce risk in nearly all other high- and intermediate-risk patients. Unfortunately, routine perioperative administration of beta-blockers to intermediate-risk patients is not supported by trial evidence and may expose these patients to increased risk of adverse outcomes—including death and stroke.

Review of the Data

Intermediate-risk patients: Inter-mediate risk patients have recently been redefined as patients with a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of two or one (See Table 1, p. 27).2,3 Older guidelines suggested noninvasive testing for such patients if they had poor functional capacity (less than four metabolic equivalents [METS]) and were undergoing intermediate-risk surgery, including orthopedic, peritoneal, and thoracic procedures.

Unfortunately, this situation is common, leading to frequent testing and unclear benefit to patients. Omission of a noninvasive evaluation in intermediate-risk orthopedic surgery patients is not associated with an increase in perioperative cardiac events.4 Most events occur in patients who did not meet criteria for preoperative testing.

The 2007 ACC/AHA Guidelines for Perioperative Evaluation and Care address this by recommending noninvasive testing only “if it will change management.” But they offer little guidance in unclear clinical situations, such as the urgent hip-fracture repair needed by our patient.

Preoperative revascularization: While it makes intuitive sense that preoperative revascularization of high-risk patients would decrease their risk of perioperative cardiac complications, evidence countering this idea is nearly definitive. In a study by McFalls, revascularization prior to major vascular surgery did not decrease the risk of perioperative MI or 30-day mortality; however, it delayed the surgical procedure, even in patients with high-risk noninvasive test results.5,6 It is generally accepted that if these high-risk patients can safely undergo major vascular surgery without revascularization, a lower-risk patient such as ours can do so at even lower risk.

In these trials, revascularization occurred in addition to medical management of coronary disease, including aspirin, statin, and—particularly in the study by Poldermans,6 where beta-blockers were started and titrated well before surgery—beta-blocker therapy.

Patients with active cardiac symptoms or signs or uncharacterized anginal symptoms should have elective surgery delayed. However, delay is rarely an option for the hospitalist, who is typically asked to address a patient’s risk shortly before urgent or emergent surgery. These difficult situations require one to weigh the cardiac risk of surgery in a patient who is not optimized versus the risk of delaying surgery to address the more urgent cardiac situation.

Timing of perioperative percutaneous intervention: For patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) or coronary lesions, the interval between percutaneous revascularization (via stent or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA]) and surgery affects rates of postoperative cardiac events.7

The recommended interval between stent placement and noncardiac surgery for patients receiving bare-metal and drug-eluting stents is six weeks and one year, respectively.8 Surgery within two weeks of stent placement can carry mortality rates as high as 40%, and this risk appears to decrease out to one year.9,10 If a new stent is in place, any potential benefit appears to be offset by the increased risk of in-stent thrombosis with subsequent MI and possible death. PTCA may not be a safe alternative, although some recommend using PTCA if the patient has unstable cardiac symptoms and needs urgent/emergent surgery.11

Perioperative discontinuation of dual antiplatelet agents (e.g., clopidogrel and aspirin) is common and appears to increase thrombosis risk. This presents a challenge when patients with recent stent placement present for urgent surgery. Minimizing the interruption of dual antiplatelet therapy is the most important intervention a hospitalist can perform. Interruption is associated with increased risk of stent thrombosis, MI, and death. If clopidogrel must be discontinued in the perioperative period, continuation of aspirin is recommended and intravenous glycoprotein 2b/3a inhibitors can be considered.12

Perioperative beta-blocker: Studies on the outcomes of perioperative beta blockade strongly suggested benefits initially. But a number of randomized trials in the past three years have not shown a positive effect.

In a landmark study published in 1996, Mangano showed that initiation of beta blockade just prior to surgery reduced perioperative MI and cardiac death in a mixed surgical population.13 Similar findings were seen with initiation of beta-blocker one month prior to vascular surgery.14 Additionally, higher doses of beta-blocker and lower heart rates in the perioperative period seem to be associated with decreased troponin release.15 Finally, perioperative beta blockade was associated with decreased mortality in high-risk patients (RCRI of three or greater), but higher mortality in lower-risk patients (e.g., RCRI of zero or one).16

More recent data reveal less benefit for perioperative beta blockade. Yang, et al., suggested that initiation of beta-blockers just prior to surgery did not decrease postoperative cardiac complications in vascular surgery patients.17 Similar results were found in a cohort of diabetic patients undergoing major surgery.18 A subsequent meta-analysis concluded that, in the aggregate, perioperative beta blockade was neither beneficial nor harmful.19

Further data have shown increased mortality with perioperative beta blockade in low-risk patients. Most recently, an abstract from the largest randomized controlled trial to date, the POISE study, suggested that preoperative beta blockade decreased MI and cardiac death, but increased the risk of stroke and produced higher overall mortality.20

It is challenging to reconcile this newer evidence with the previous data. While it seems intuitive that blunting the catecholamine response would minimize cardiac workload and therefore decrease perioperative infarcts, surgical patients are also at risk for poor pain control, sepsis, hypovolemia, and venous thromboembolism. Beta blockade can obscure their clinical manifestations, delaying diagnosis or complicating therapy. Inconsistencies among studies and published guidelines make them difficult to apply broadly, particularly with the intermediate-risk patient. Finally, perioperative beta blockade is poorly defined in terms of timing of initiation, target heart rate, and duration of postoperative use.

Until more definitive trial data are published, it seems most prudent to continue beta-blockers in patients already using them. Start them as far in advance of surgery as possible in patients with high-risk features (such as a positive stress test). After surgery, pay close attention to volume status, pain, signs of sepsis, or other noncardiac complications.

Back to the Case

As per the 2007 ACC/AHA guidelines, this patient with one clinical risk factor (diabetes) and good functional capacity can proceed to the operating room without further intervention. While it is likely a patient with diabetes and hyperlipidemia has some degree of CAD, including possible vulnerable plaques, the best medical evidence offers little to decrease her operative cardiac risk. Perioperative beta blockade is not indicated at her level of risk (RCRI of one) given the inconsistent benefits and possible harm to patients like this seen in trials to date.

If she were limited in terms of functional capacity (i.e., less than four METS), the 2007 ACC/AHA algorithm suggests preoperative noninvasive testing “if it would change management.”

How might a positive stress test change management in this case? Revascularization with stenting in close proximity to noncardiac surgery is not safe, and there appears to be no benefit to preoperative revascularization before high-risk vascular surgery. However, ischemia on preoperative testing is an indication for a beta-blocker. A brief delay in her surgery to allow dose titration and use of telemetry monitoring after surgery would increase the safety of beta-blockers after surgery. How long to continue beta-blockers is an open question, but at least 30 days would seem adequate, tapering rather than abruptly discontinuing the dose. TH

Dr. Carter is an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver in the Section of Hospital Medicine, where he directs the Medicine Consult Service. Dr. Auerbach is an associate professor of medicine in residence, associate director of the general medicine research fellowship, director of quality improvement for the UCSF Department of Medicine, and director of the surgical care Improvement program at UCSF. His research interests include perioperative medicine and quality improvement.

References

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1043-1049.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al. ACC/AHA Guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary. Circulation 2002;105:1257-1267.

- Fleischer LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for noncardiac surgery: executive summary. Circulation. 2007;116:1971-1996.

- Salerno SM, Carlson DW, Soh EK, et al. Impact of perioperative cardiac assessment guidelines on management of orthopedic surgery patients. Am J Med. 2007;120(2):185.

- McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2795-2804.

- Poldermans D, Schouten O, Vidakovic R, et al. A clinical randomized trial to evaluate the safety of a noninvasive approach in high-risk patients undergoing major vascular surgery: The DECREASE-V Pilot Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(17):1763-1769.

- Wilson, SH, Fasseas P, Orford JL, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery in the two months following coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(2):234-240.

- Grines, CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents. Circulation. 2007; 115:813-818.

- Kaluza GL, Joseph J, Lee JR, et al. Catastrophic outcomes of noncardiac surgery soon after coronary stenting. Am J Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(5):1288-1294.

- Schouten O, Bax JJ, Damen J, et al. Coronary stent placement immediately before non cardiac surgery: a potential risk? Anesthesiology 106(5);2007:1067.

- Leibowitz D, Cohen M, Planer D, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk of noncardiac surgery following coronary angioplasty with versus without stenting. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(8):1188-1191.

- Auerbach A, Goldman L. Assessing and reducing the cardiac risk of noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2006;113:1361-1376.

- Mangano DT, Layug EL, Wallace A, et al. Effect of atenolol on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(23):1713-1720.

- Poldermans D, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(24):1789-1794.

- Feringa HH, Bax JJ, Boersma E, et al. High dose b-blockers and tight heart rate control reduce myocardial ischemia and troponin T release in vascular surgery patients. Circulation. 2006;114(supp):I344.

- Lindenauer PK Pekow P, Wang K, et al. Perioperative beta-blocker therapy and mortality after major noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):349-361.

- Yang H, Raymer K, Butler R, et al. The effects of perioperative beta blockade: results of the Metoprolol after Vascular Surgery (MaVS) study, a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2006;152(5):983-990.

- Juul AB, Wetterslev J, Gluud C, et al. Effect of perioperative ß blockade in patients with diabetes undergoing major non-cardiac surgery: randomized placebo controlled, blinded multicentre trial. BMJ. 2006 June;332:1482.

- Devereaux PJ, Beattie WS, Choi PT, et al. How strong is the evidence for the use of perioperative ß blockers in noncardiac surgery? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;331:313.

- Devereaux PJ. POISE Abstract. American Heart Association Annual Scientific Session, Orlando, Fla., November 2007.

Deposition Minefield

One day, you’re sitting in your office when a stranger appears and asks, “Are you Dr. Smith?” When you say yes, the stranger hands you a sheaf of papers. You open the papers and see you’ve been “commanded” to attend a deposition at a lawyer’s office next week. How do you prepare?

The Basics

Black’s Law Dictionary gives a long definition of a deposition. But the shorter, more practical definition is that a deposition is a witness’s sworn out-of-court testimony. When a physician gives a deposition in a lawyer’s office, this testimony has the same legal effect as though the physician were testifying in court.

Lawyers typically view depositions as one of two types:

- Discovery depositions: These allow lawyers to discover the substance of a witness’s testimony before trial. They can touch upon a number of subjects that seem tangential to the case. A lawyer taking a discovery deposition is putting together the pieces of the case and may or may not ask the witness to testify at trial; and

- Perpetuation depositions: These let lawyers present the testimony of a witness who cannot appear at trial. Perpetuation depositions substitute for the examinations and cross-examinations that would normally occur in the courtroom. Perpetuation depositions are generally shorter and more focused than discovery depositions.

In all depositions, lawyers ask questions of the witness and can object to legally improper questions. The lawyers can ask the witness to refer to documents or other exhibits during the deposition. A court reporter will transcribe the questions and answers and condense them into a written transcript. A judge is normally not present for a deposition but can be called during the deposition to make rulings.

Know Your Role

Perhaps the most important thing you can do in preparing for a deposition is understand your role in the lawsuit. Generally, physicians serve in one of three potential roles as deponents:

Medical malpractice defendant: When a patient sues a physician for malpractice, the patient’s attorney normally will take the physician’s deposition. In this highly adversarial process, the patient’s attorney attempts to demonstrate that the physician’s negligence injured the patient. A physician being deposed as a defendant must prepare by meeting with his attorney and reviewing the issues likely to arise during the proceedings. If you are a defendant in a lawsuit, you must set aside adequate time to prepare for the deposition with your attorney;

Retained expert witness: The rules of evidence allow people with specialized knowledge to testify as experts in fields normally beyond the average juror’s experience. Because they have specialized knowledge, experts are allowed to state opinions in their testimony, such as whether a physician’s conduct complied with the applicable standards of care. Attorneys generally hire expert witnesses to present opinions in a case and will provide a summary of the expert’s testimony before the deposition; and

Treating physician: Many physicians are deposed concerning the care they provided to a patient in lawsuits that implicate the patient’s health (auto accident, work injury, disability suit). These depositions focus on the substance of treatment, the patient’s medical condition, and the patient’s prognosis. The physician normally does not have any interest in how the lawsuit is resolved. A treating physician is often compensated for his time in the deposition, even though he was not retained as an expert to testify in the lawsuit.

Golden Rules

Because depositions are stressful, lawyers ask witnesses to remember only three rules.

Tell the truth: Your only job as a witness is to tell the truth. If you follow this rule, you have discharged your obligation to the legal system.

However, keep some things in mind when telling the truth. In particular, your ability to tell the truth is subject to the limitations of your memory and the fact that your deposition may be occurring several years after you provided care. “I don’t know” and “I don’t remember” are absolutely acceptable answers in a deposition. In fact, they are preferable to inaccurate or untruthful testimony. If reviewing a document (such as the patient’s medical records) will help you provide accurate and truthful testimony, don’t be shy about asking to review them. In any situation where you are guessing or providing your best recollection, make sure the lawyer knows you are doing your best but that you can’t remember all the details.

Make sure you understand the question: This rule seems self-evident, but many lawyers ask convoluted or compound questions. Lawyers may also use language unfamiliar to you as an outsider to the legal process. For example, when lawyers use the phrase “standard of care,” it has a fairly precise definition (it is an action a reasonably careful physician would undertake under the same or similar circumstances). Ask for clarification of any question that is not clear. It’s the lawyer’s job to ask an understandable question, not the physician’s job to answer a question that doesn’t make sense. Be extra careful when the opposing lawyer objects to a question. While the lawyer’s objection does not relieve you from answering, it should signal you that the question is potentially flawed or beyond the scope of your knowledge.

Answer only what you’re asked: Invariably, physicians struggle most when they don’t focus their answers on the question posed to them.

The majority of questions in a deposition can be answered “Yes,” “No,” “I don’t know,” and “I don’t remember.” Yet many physicians tend to volunteer additional information to explain their answers. Because lawyers are trained to recognize and follow up on nonresponsive answers, the physician’s deposition becomes longer and more challenging. To provide a better answer, don’t think out loud. Ponder the question and mentally prepare your answer. Doing so lets you respond more precisely. Answer only the question you are asked. If there is an area that needs more explanation, the other party’s attorney (or your attorney) will have an opportunity to allow you to clarify the record.

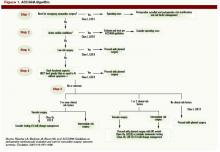

To help you follow the rules, use this decision tree during your deposition (see Figure 1, left).

Regardless of the purpose of a deposition or your perceived role in it, consult with an attorney before being deposed. Even if you believe you are being deposed only as a treating provider, a deposition could lead to potential claims or raise concerns about your records. If served with a subpoena, contact your insurance company, which may retain an attorney to assist you. TH

Patrick O’Rourke works in the Office of University Counsel, Department of Litigation, University of Colorado, Denver.

One day, you’re sitting in your office when a stranger appears and asks, “Are you Dr. Smith?” When you say yes, the stranger hands you a sheaf of papers. You open the papers and see you’ve been “commanded” to attend a deposition at a lawyer’s office next week. How do you prepare?

The Basics

Black’s Law Dictionary gives a long definition of a deposition. But the shorter, more practical definition is that a deposition is a witness’s sworn out-of-court testimony. When a physician gives a deposition in a lawyer’s office, this testimony has the same legal effect as though the physician were testifying in court.