User login

The Hospitalist only

Subtle Skills

Hospitalists with a hunger for taking on administrative roles often pursue an advanced degree. But whether it’s to assume a leadership role or just do a better job, it’s the not-altogether-obvious skills that can help hospitalists improve their careers and job satisfaction.

By refining communication styles, being receptive to mentoring, or learning how to influence decision-makers, hospitalists can convey competence to their peers and superiors. Intangible strengths such as these will help the hospitalist who wishes to carve a niche as a quality-improvement researcher, director of a medical education clerkship, patient safety officer, or medical director.

Who Needs What

The administrative skills hospitalists need depend on their career goals. Those who reflect on their career goals, identify their core values, and consider what is feasible at different stages in their lives can more quickly build the abilities they’ll need. This self-awareness is perhaps the first skill to develop.

The setting and practice model hospitalists work in also influences which skills they may need.

“Although the skills needed in different settings may be fundamentally the same, the politics differ between a community hospital and a teaching hospital,” says Sayeed Khan, MD, director of the hospitalist program of Lakeside Medical Group. “Communication skills may be even more crucial in a community hospital, where it’s less understood what a hospitalist is.” Such ability to educate people in Hospitalist 101 is yet another skill a savvy administrator or administrator-to-be should hone.

Hospitalists also need to understand quality control and other measures—and what the numbers mean.

For example, says Dr. Khan, it’s valuable to know:

- What it means to have good bed days at the end of the month and an average length of stay of 3.3 days;

- How that compares with other groups in other hospitals; and

- The implications of those measures in terms of outcomes, dollar costs, and savings to the hospital as well as the group—and how that translates for the patient.

“Those are the types of figures that many hospitalists don’t really understand,” says Dr. Khan.

But hospitalists can learn by observing and studying. “I’m a good example of that in that I do not have a formal business background,” Dr. Khan says. “Along with the literature, networking with other people, particularly at the SHM annual meeting, can help hospitalists gain a better understanding of what these numbers mean and what the benchmarks are.”

He believes administrative skills can be divided into two categories: those related to metrics (the math behind what hospitalists do) and those related to patient care.

In regard to patient care, effective committee participation is an administrative ability that can influence the standard of care. For example, Dr. Khan is participating in committee work in the area of maintaining patients’ glycemic control.

“Historically, that issue was not well addressed,” he says. It is now recognized that patients who have tight glycemic control do much better while hospitalized, irrespective of whether they have diabetes. “But it’s difficult to get other clinicians to change their practice styles,” says Dr. Khan. “You can implement change in your own practice, and others can learn by example. But if you are on a committee that designs new protocols and those get implemented, then you’ve directly changed how medicine is practiced at that hospital.”

Being able to win buy-in for your ideas makes that possible. “Purely speaking, committee participation is not an administrative role,” says Dr. Khan. “But it is an administrative skill in that it is outside the scope of what’s normally required for a hospitalist.”

Get Help

Honing one’s receptivity to mentorship is another vital ability for the upwardly mobile hospitalist. Mentors can direct inexperienced physicians to resources that may help them develop proficiency. A mentor who has grappled with the same issues can help open doors to opportunities hospitalists may not know about.

As she reflects on her early career, when she had no mentors and no administrative experience, Sylvia C.W. McKean, MD, realizes she could have used guidance and advocacy. Effective mentorship helps hospitalists reach their goals faster with fewer impediments, she says.

“Mentorship is critical,” says Dr. McKean, medical director, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “But knowing how to receive the information you’re getting and how to apply it to your own specific professional goals can really help you develop the skills that will help you move your career forward. Informal mentorship is one area where there has been less opportunity for women in the past, resulting in more promotions for men.”

Other skills women may especially need are learning the written and unwritten rules of promotion, being more assertive in finding out what they are, and developing diplomacy—including learning to say no with finesse.

“The reality is that if you are in an environment that has predominantly male leadership, it is important for [a woman] to have male advocates to support whatever it is that you are trying to do,” says Dr. McKean. “In some instances they may have to speak for you.”

Efficiency and setting priorities are also important skills.

“I learned very early on that efficiency was critical to managing several roles—administrative, patient care, and raising three boys,” says Dr. McKean. “There were some things, however, that in retrospect I did not need to do. For example, I did my own home-improvement tasks instead of hiring someone else to do them. For women in particular, you don’t have to be a super everything. At different phases in your life your priorities will vary. Get help so that you’re not spending time doing tasks that don’t further your goals.”

Communication

Facility with communication, of course, is paramount in every aspect of medicine. Being poised, articulate, concise, and persuasive to get your message across, says Dr. McKean, goes a long way toward advancing one’s career.

“It took me a long time to realize this,” says Dr. McKean. “For example, whenever I generated reports I tried to have as much information in there as possible because I thought it would look like I was very knowledgeable. A one-page document that summarizes the key points is often more effective in getting people’s attention.”

Another subset of communication is skill at public speaking, which may lead to being invited to give lectures.

Dr. Khan believes shy, less-articulate clinicians can begin to improve their public speaking by serving on committees. “Unless the committee is a committee of two, that is the appropriate forum to begin voicing your opinions and expertise on a particular matter,” he says. “There’s a certain comfort level built into that because you’re not necessarily speaking on a topic you are unfamiliar with.”

Another intangible administrative skill, he says, is the ability to deal with people from different walks of life. Some highly placed hospital administrators don’t have clinical backgrounds and will require explanations of clinical situations that mesh with their business understanding.

Time Management

Organization is a critical administrative skill no matter what career path a hospitalist follows.

“As hospitalists we are typically juggling more than one thing at one time,” Dr. Khan says. “As a hospitalist who is involved in administrative tasks, if you’re not organized, that is a path to failure.”

Strive to hire the right people for clerical and administrative staff positions. They will fill in the weak spots to keep you on track and present a good image as your front person. But having a good clerical or administrative assistant doesn’t let you off the hook; you, too, must demonstrate solid time management. Make sure you take good notes at committees, quickly access data or documentation, and research and report back well.

The Interpersonal

Robert L. Benak, MD, a hospitalist and medical director of Champlain Valley Physicians Hospital (CVPH) Medical Center, a 341-bed acute care hospital and 54-bed skilled nursing facility in Plattsburgh, N.Y., thinks the most important intangible skills involve managing relationships.

Again, self-reflection helps. “Understand what your personality is like on a calm day and what it is like on a stressful day,” he says.

He says it’s critical to be able to negotiate with others. “Understanding what lies underneath, what common and different interests the two negotiating partners have helps you focus on getting the best compromise of conflicting interests to resolve a disagreement in an amicable and effective way,” he says.

Dr. Benak, who joined SHM around the time his group started in October 2006, thanks the SHM Leadership Academy for strengthening his interpersonal skills. He has tried to bring home what he learned to his group of five hospitalists.

Recently, he had to determine whether to designate a patient with abdominal pain as a surgical or medical patient. Dr. Benak invoked his “ability to sit down with the orthopedic surgeon and general surgeon, recognizing that they’ve got legitimate interests and concerns, as do I, and figuring out what works well for us, and more importantly, what works best for the patient.”

That ability to compromise is indispensable to growth as a hospitalist, he says.

“I was a chemistry major in college and loved working with concrete, though sometimes complicated, problems where you’re either right or you’re wrong,” he says. “I’ve come to see that giving up being right, and giving up any sense of entitlement I may feel in having the principal position, are skills. Even if you think the other person is being unreasonable, you have to accept that as a fact and figure out how to cope with that in a way that is a credit to yourself and your program.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

Hospitalists with a hunger for taking on administrative roles often pursue an advanced degree. But whether it’s to assume a leadership role or just do a better job, it’s the not-altogether-obvious skills that can help hospitalists improve their careers and job satisfaction.

By refining communication styles, being receptive to mentoring, or learning how to influence decision-makers, hospitalists can convey competence to their peers and superiors. Intangible strengths such as these will help the hospitalist who wishes to carve a niche as a quality-improvement researcher, director of a medical education clerkship, patient safety officer, or medical director.

Who Needs What

The administrative skills hospitalists need depend on their career goals. Those who reflect on their career goals, identify their core values, and consider what is feasible at different stages in their lives can more quickly build the abilities they’ll need. This self-awareness is perhaps the first skill to develop.

The setting and practice model hospitalists work in also influences which skills they may need.

“Although the skills needed in different settings may be fundamentally the same, the politics differ between a community hospital and a teaching hospital,” says Sayeed Khan, MD, director of the hospitalist program of Lakeside Medical Group. “Communication skills may be even more crucial in a community hospital, where it’s less understood what a hospitalist is.” Such ability to educate people in Hospitalist 101 is yet another skill a savvy administrator or administrator-to-be should hone.

Hospitalists also need to understand quality control and other measures—and what the numbers mean.

For example, says Dr. Khan, it’s valuable to know:

- What it means to have good bed days at the end of the month and an average length of stay of 3.3 days;

- How that compares with other groups in other hospitals; and

- The implications of those measures in terms of outcomes, dollar costs, and savings to the hospital as well as the group—and how that translates for the patient.

“Those are the types of figures that many hospitalists don’t really understand,” says Dr. Khan.

But hospitalists can learn by observing and studying. “I’m a good example of that in that I do not have a formal business background,” Dr. Khan says. “Along with the literature, networking with other people, particularly at the SHM annual meeting, can help hospitalists gain a better understanding of what these numbers mean and what the benchmarks are.”

He believes administrative skills can be divided into two categories: those related to metrics (the math behind what hospitalists do) and those related to patient care.

In regard to patient care, effective committee participation is an administrative ability that can influence the standard of care. For example, Dr. Khan is participating in committee work in the area of maintaining patients’ glycemic control.

“Historically, that issue was not well addressed,” he says. It is now recognized that patients who have tight glycemic control do much better while hospitalized, irrespective of whether they have diabetes. “But it’s difficult to get other clinicians to change their practice styles,” says Dr. Khan. “You can implement change in your own practice, and others can learn by example. But if you are on a committee that designs new protocols and those get implemented, then you’ve directly changed how medicine is practiced at that hospital.”

Being able to win buy-in for your ideas makes that possible. “Purely speaking, committee participation is not an administrative role,” says Dr. Khan. “But it is an administrative skill in that it is outside the scope of what’s normally required for a hospitalist.”

Get Help

Honing one’s receptivity to mentorship is another vital ability for the upwardly mobile hospitalist. Mentors can direct inexperienced physicians to resources that may help them develop proficiency. A mentor who has grappled with the same issues can help open doors to opportunities hospitalists may not know about.

As she reflects on her early career, when she had no mentors and no administrative experience, Sylvia C.W. McKean, MD, realizes she could have used guidance and advocacy. Effective mentorship helps hospitalists reach their goals faster with fewer impediments, she says.

“Mentorship is critical,” says Dr. McKean, medical director, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “But knowing how to receive the information you’re getting and how to apply it to your own specific professional goals can really help you develop the skills that will help you move your career forward. Informal mentorship is one area where there has been less opportunity for women in the past, resulting in more promotions for men.”

Other skills women may especially need are learning the written and unwritten rules of promotion, being more assertive in finding out what they are, and developing diplomacy—including learning to say no with finesse.

“The reality is that if you are in an environment that has predominantly male leadership, it is important for [a woman] to have male advocates to support whatever it is that you are trying to do,” says Dr. McKean. “In some instances they may have to speak for you.”

Efficiency and setting priorities are also important skills.

“I learned very early on that efficiency was critical to managing several roles—administrative, patient care, and raising three boys,” says Dr. McKean. “There were some things, however, that in retrospect I did not need to do. For example, I did my own home-improvement tasks instead of hiring someone else to do them. For women in particular, you don’t have to be a super everything. At different phases in your life your priorities will vary. Get help so that you’re not spending time doing tasks that don’t further your goals.”

Communication

Facility with communication, of course, is paramount in every aspect of medicine. Being poised, articulate, concise, and persuasive to get your message across, says Dr. McKean, goes a long way toward advancing one’s career.

“It took me a long time to realize this,” says Dr. McKean. “For example, whenever I generated reports I tried to have as much information in there as possible because I thought it would look like I was very knowledgeable. A one-page document that summarizes the key points is often more effective in getting people’s attention.”

Another subset of communication is skill at public speaking, which may lead to being invited to give lectures.

Dr. Khan believes shy, less-articulate clinicians can begin to improve their public speaking by serving on committees. “Unless the committee is a committee of two, that is the appropriate forum to begin voicing your opinions and expertise on a particular matter,” he says. “There’s a certain comfort level built into that because you’re not necessarily speaking on a topic you are unfamiliar with.”

Another intangible administrative skill, he says, is the ability to deal with people from different walks of life. Some highly placed hospital administrators don’t have clinical backgrounds and will require explanations of clinical situations that mesh with their business understanding.

Time Management

Organization is a critical administrative skill no matter what career path a hospitalist follows.

“As hospitalists we are typically juggling more than one thing at one time,” Dr. Khan says. “As a hospitalist who is involved in administrative tasks, if you’re not organized, that is a path to failure.”

Strive to hire the right people for clerical and administrative staff positions. They will fill in the weak spots to keep you on track and present a good image as your front person. But having a good clerical or administrative assistant doesn’t let you off the hook; you, too, must demonstrate solid time management. Make sure you take good notes at committees, quickly access data or documentation, and research and report back well.

The Interpersonal

Robert L. Benak, MD, a hospitalist and medical director of Champlain Valley Physicians Hospital (CVPH) Medical Center, a 341-bed acute care hospital and 54-bed skilled nursing facility in Plattsburgh, N.Y., thinks the most important intangible skills involve managing relationships.

Again, self-reflection helps. “Understand what your personality is like on a calm day and what it is like on a stressful day,” he says.

He says it’s critical to be able to negotiate with others. “Understanding what lies underneath, what common and different interests the two negotiating partners have helps you focus on getting the best compromise of conflicting interests to resolve a disagreement in an amicable and effective way,” he says.

Dr. Benak, who joined SHM around the time his group started in October 2006, thanks the SHM Leadership Academy for strengthening his interpersonal skills. He has tried to bring home what he learned to his group of five hospitalists.

Recently, he had to determine whether to designate a patient with abdominal pain as a surgical or medical patient. Dr. Benak invoked his “ability to sit down with the orthopedic surgeon and general surgeon, recognizing that they’ve got legitimate interests and concerns, as do I, and figuring out what works well for us, and more importantly, what works best for the patient.”

That ability to compromise is indispensable to growth as a hospitalist, he says.

“I was a chemistry major in college and loved working with concrete, though sometimes complicated, problems where you’re either right or you’re wrong,” he says. “I’ve come to see that giving up being right, and giving up any sense of entitlement I may feel in having the principal position, are skills. Even if you think the other person is being unreasonable, you have to accept that as a fact and figure out how to cope with that in a way that is a credit to yourself and your program.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

Hospitalists with a hunger for taking on administrative roles often pursue an advanced degree. But whether it’s to assume a leadership role or just do a better job, it’s the not-altogether-obvious skills that can help hospitalists improve their careers and job satisfaction.

By refining communication styles, being receptive to mentoring, or learning how to influence decision-makers, hospitalists can convey competence to their peers and superiors. Intangible strengths such as these will help the hospitalist who wishes to carve a niche as a quality-improvement researcher, director of a medical education clerkship, patient safety officer, or medical director.

Who Needs What

The administrative skills hospitalists need depend on their career goals. Those who reflect on their career goals, identify their core values, and consider what is feasible at different stages in their lives can more quickly build the abilities they’ll need. This self-awareness is perhaps the first skill to develop.

The setting and practice model hospitalists work in also influences which skills they may need.

“Although the skills needed in different settings may be fundamentally the same, the politics differ between a community hospital and a teaching hospital,” says Sayeed Khan, MD, director of the hospitalist program of Lakeside Medical Group. “Communication skills may be even more crucial in a community hospital, where it’s less understood what a hospitalist is.” Such ability to educate people in Hospitalist 101 is yet another skill a savvy administrator or administrator-to-be should hone.

Hospitalists also need to understand quality control and other measures—and what the numbers mean.

For example, says Dr. Khan, it’s valuable to know:

- What it means to have good bed days at the end of the month and an average length of stay of 3.3 days;

- How that compares with other groups in other hospitals; and

- The implications of those measures in terms of outcomes, dollar costs, and savings to the hospital as well as the group—and how that translates for the patient.

“Those are the types of figures that many hospitalists don’t really understand,” says Dr. Khan.

But hospitalists can learn by observing and studying. “I’m a good example of that in that I do not have a formal business background,” Dr. Khan says. “Along with the literature, networking with other people, particularly at the SHM annual meeting, can help hospitalists gain a better understanding of what these numbers mean and what the benchmarks are.”

He believes administrative skills can be divided into two categories: those related to metrics (the math behind what hospitalists do) and those related to patient care.

In regard to patient care, effective committee participation is an administrative ability that can influence the standard of care. For example, Dr. Khan is participating in committee work in the area of maintaining patients’ glycemic control.

“Historically, that issue was not well addressed,” he says. It is now recognized that patients who have tight glycemic control do much better while hospitalized, irrespective of whether they have diabetes. “But it’s difficult to get other clinicians to change their practice styles,” says Dr. Khan. “You can implement change in your own practice, and others can learn by example. But if you are on a committee that designs new protocols and those get implemented, then you’ve directly changed how medicine is practiced at that hospital.”

Being able to win buy-in for your ideas makes that possible. “Purely speaking, committee participation is not an administrative role,” says Dr. Khan. “But it is an administrative skill in that it is outside the scope of what’s normally required for a hospitalist.”

Get Help

Honing one’s receptivity to mentorship is another vital ability for the upwardly mobile hospitalist. Mentors can direct inexperienced physicians to resources that may help them develop proficiency. A mentor who has grappled with the same issues can help open doors to opportunities hospitalists may not know about.

As she reflects on her early career, when she had no mentors and no administrative experience, Sylvia C.W. McKean, MD, realizes she could have used guidance and advocacy. Effective mentorship helps hospitalists reach their goals faster with fewer impediments, she says.

“Mentorship is critical,” says Dr. McKean, medical director, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “But knowing how to receive the information you’re getting and how to apply it to your own specific professional goals can really help you develop the skills that will help you move your career forward. Informal mentorship is one area where there has been less opportunity for women in the past, resulting in more promotions for men.”

Other skills women may especially need are learning the written and unwritten rules of promotion, being more assertive in finding out what they are, and developing diplomacy—including learning to say no with finesse.

“The reality is that if you are in an environment that has predominantly male leadership, it is important for [a woman] to have male advocates to support whatever it is that you are trying to do,” says Dr. McKean. “In some instances they may have to speak for you.”

Efficiency and setting priorities are also important skills.

“I learned very early on that efficiency was critical to managing several roles—administrative, patient care, and raising three boys,” says Dr. McKean. “There were some things, however, that in retrospect I did not need to do. For example, I did my own home-improvement tasks instead of hiring someone else to do them. For women in particular, you don’t have to be a super everything. At different phases in your life your priorities will vary. Get help so that you’re not spending time doing tasks that don’t further your goals.”

Communication

Facility with communication, of course, is paramount in every aspect of medicine. Being poised, articulate, concise, and persuasive to get your message across, says Dr. McKean, goes a long way toward advancing one’s career.

“It took me a long time to realize this,” says Dr. McKean. “For example, whenever I generated reports I tried to have as much information in there as possible because I thought it would look like I was very knowledgeable. A one-page document that summarizes the key points is often more effective in getting people’s attention.”

Another subset of communication is skill at public speaking, which may lead to being invited to give lectures.

Dr. Khan believes shy, less-articulate clinicians can begin to improve their public speaking by serving on committees. “Unless the committee is a committee of two, that is the appropriate forum to begin voicing your opinions and expertise on a particular matter,” he says. “There’s a certain comfort level built into that because you’re not necessarily speaking on a topic you are unfamiliar with.”

Another intangible administrative skill, he says, is the ability to deal with people from different walks of life. Some highly placed hospital administrators don’t have clinical backgrounds and will require explanations of clinical situations that mesh with their business understanding.

Time Management

Organization is a critical administrative skill no matter what career path a hospitalist follows.

“As hospitalists we are typically juggling more than one thing at one time,” Dr. Khan says. “As a hospitalist who is involved in administrative tasks, if you’re not organized, that is a path to failure.”

Strive to hire the right people for clerical and administrative staff positions. They will fill in the weak spots to keep you on track and present a good image as your front person. But having a good clerical or administrative assistant doesn’t let you off the hook; you, too, must demonstrate solid time management. Make sure you take good notes at committees, quickly access data or documentation, and research and report back well.

The Interpersonal

Robert L. Benak, MD, a hospitalist and medical director of Champlain Valley Physicians Hospital (CVPH) Medical Center, a 341-bed acute care hospital and 54-bed skilled nursing facility in Plattsburgh, N.Y., thinks the most important intangible skills involve managing relationships.

Again, self-reflection helps. “Understand what your personality is like on a calm day and what it is like on a stressful day,” he says.

He says it’s critical to be able to negotiate with others. “Understanding what lies underneath, what common and different interests the two negotiating partners have helps you focus on getting the best compromise of conflicting interests to resolve a disagreement in an amicable and effective way,” he says.

Dr. Benak, who joined SHM around the time his group started in October 2006, thanks the SHM Leadership Academy for strengthening his interpersonal skills. He has tried to bring home what he learned to his group of five hospitalists.

Recently, he had to determine whether to designate a patient with abdominal pain as a surgical or medical patient. Dr. Benak invoked his “ability to sit down with the orthopedic surgeon and general surgeon, recognizing that they’ve got legitimate interests and concerns, as do I, and figuring out what works well for us, and more importantly, what works best for the patient.”

That ability to compromise is indispensable to growth as a hospitalist, he says.

“I was a chemistry major in college and loved working with concrete, though sometimes complicated, problems where you’re either right or you’re wrong,” he says. “I’ve come to see that giving up being right, and giving up any sense of entitlement I may feel in having the principal position, are skills. Even if you think the other person is being unreasonable, you have to accept that as a fact and figure out how to cope with that in a way that is a credit to yourself and your program.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

Hospitalists on Top

Many technically skilled professionals—including computer programmers, stockbrokers, or hospitalists—aspire to the executive suite.

The burgeoning field of hospital medicine offers especially enticing rewards for business-minded doctors, inducing frontline leaders to trade the white coat for wing tips and a shot at the top.

The pinnacle can be stratospheric. Adam Singer, MD, CEO of California-based IPC-The Hospitalist Company, traded his white coat for the so-called C suite. He has since filed an initial public offering that should produce $105 million for IPC’s stakeholders.

There’s also lots of room for hospitalists with more modest executive aspirations. The skills acquired by good hospitalists—thoroughness, the ability to solve complex problems, critical thinking, strong motivation, sound work ethic, and teamwork—serve physician executives well. Some physicians back into the executive suite once they realize they’re attracted to the business end of medicine. Those are the clinicians who volunteer to do the group’s scheduling or find that they enjoy negotiating contracts with new hires and payers. Others pursue a personal road map to the C suite.

Balancing Act

The biggest decision facing a hospitalist with managerial aspirations is whether to relinquish patient care.

“For most of your career you must remain active clinically, even though your time is disjointed because you’re intensely needed in both clinical and administrative areas,” says Andrew Urbach, MD, medical director of clinical excellence and service at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He manages both by constantly adapting. His time had been evenly split between clinical and administrative duties until July, when he cut back on his clinical duties. He now spends one week every quarter as a hospitalist and a half-day a week at the clinic. “It’s difficult balancing both, and reaching the highest level of excellence in two areas is demanding,” he says. “But the best hospitalist managers continue to see patients to maintain credibility with their peers.”

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.-based Team Health, Hospital Medicine Division, was a staff hospitalist who ceded clinical work for a managerial career. After a three-year stint as a hospitalist with Covenant HealthCare’s hospital medicine program at Covenant Medical Center in Saginaw, Mich., her mentors recruited her to “jump around the country starting hospitalist programs during 2004 and 2005,” she says. “I was in the right place at the right time, and I had the confidence to move my agenda in a diplomatic way and with humor.”

Dr. Goldsholl reluctantly gave up clinical responsibilities three years ago. “It’s all about balance in my life,” she says. “It was a conscious decision to give up patient care. I miss it, but I wanted to take my career to a national level. I travel a great deal, which isn’t compatible with patient care.”

Business School

Hospitalists attracted to management often realize they need more business schooling, says Kevin Shulman, MD, MBA, professor of medicine and management at Duke University Medical Center and the Fuqua School of Business in Durham, N.C.

“The issues in medical training are clinical, not organizational,” he says. “As you move up in administration you don’t have business skills you need. When doctors feel frustrated about not being effective organizationally, that’s when they think about business school.”

Edward Ogata, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago, and a pediatric neonatologist, realized how useful an MBA would be as he moved from clinical work to management. “I went back to school for an MBA at Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management 27 years after graduating from medical school,” he says. Pushed by the healthcare market into negotiating managed-care contracts in the 1980s, Dr. Ogata realized he knew little about accounting and finance. The always-precarious financial situations of children’s hospitals encouraged him to get the business skills to cope.

At Kellogg, in Chicago, Dr. Ogata was assigned homework and teamwork with executives from Motorola, Lucent, and GE. The first year was difficult because he was still covering call and juggling administrative tasks. He got up at 4 a.m. every day to study. Armed with business skills, Dr. Ogata feels better equipped to meet the financial and administrative needs of his inner-city hospital. “We’re not in a nice suburb with a favorable payer mix, and a hospital isn’t really a business in the conventional sense,’’ he notes. “But we are committed to doing the best.”

For Joy Drass, MD, MBA, a critical care trauma surgeon for 13 years and president of Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., methodically performing clinical tasks prepared her for top management. She assumed the presidency of the troubled hospital in 2001, one year after MedStar Health in Columbia, Md., acquired it. The hospital had recorded losses in excess of $200 million before MedStar stepped in.

“Many skills I developed as a critical care physician had an absolute application in this stressed organization,” she says. “In medicine, it’s called triage. In business, it’s prioritizing. You look at a situation and quickly set goals to get from point A to point B, encourage team work, and develop structures to support people when they are struggling through uncertainty.” Skills she learned as a graduate of the Wharton business school in Philadelphia helped her stabilize hospital operations, improve customer service and revenue collection, and develop a long-term strategic plan to improve the hospital’s chances of survival.

Varied Paths

Some hospitalists acquire business smarts from instinct and experience. When he was 13 years old, Dr. Urbach ran his family’s retail business for weeks at a time when his parents were away.

“I’ve had no formal [business] school training, but my entrepreneurial instincts and management skills were honed early in life,” he says.

Team Health’s Dr. Goldsholl intended to get a formal MBA, but was too busy. “SHM’s Leadership Academy and other programs gave me management skills, and I chose CME credits in business and management areas,” she says. “I’m also more of an experiential than a classroom learner. Mentoring and other informal settings work for me.”

Michael Ruhlen, MD, MHM, Toledo (Ohio) Children’s Hospital corporate vice president of medical informatics and vice president of medical affairs, made a successful if not easy move from clinician to manager. Acting as a hospitalist seven years before the discipline was named in 1996, he developed systematic, data-driven clinical pathways and trained other would-be pediatric hospitalists in acute care pediatrics. In 2001 he was the first recipient of the National Association of Inpatient Physician’s Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine. The award recognized his managerial skill in building a hospitalist program from scratch.

Unlike hospitalists who are moving from well-defined clinical tracks to managerial roles, Dr. Ruhlen operated in uncharted territory in his first decade as a hospitalist. From the beginning of his hospitalist career, Dr. Ruhlen’s business head identified volume-dependent competency as critical to clinical and financial success. “I saw how to create time and quality efficiencies,” he explains. “If you do one or two lumbar punctures a year, you might stick a child five or six times. Doing a higher volume of procedures led to smoother operations.”

Recognizing the complexities of hospital management, Dr. Ruhlen returned to school to sharpen his management skills. He chose the Harvard School of Public Health’s master’s in healthcare management over an MBA because, as he puts it, “I’m interested in managing a hospital, not running Campbell’s Soup.” As a hospitalist executive, he works on improving the hospital’s IT systems, developing new physician leaders, and taking the lead on change management and patient safety issues. He also has been tapped twice to serve as acting hospital president.

Medicine as Business

Hospitalists enjoy an array of career choices. Those who savor the pure joy of clinical work can continue on that path, while others can choose a career in management; some can blend both. No matter what their career paths, healthcare’s increasing complexity will keep them fully occupied.

“As medicine grows more complex, students spend their time mastering clinical issues,” Dr. Shulman notes. “Many third-year med students don’t even know the difference between Medicaid and Medicare. As they practice as hospitalists and want to move up the administrative ranks, they will acquire the general business skills that will help them be effective and reshape healthcare policy.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a medical writer based in New York.

Many technically skilled professionals—including computer programmers, stockbrokers, or hospitalists—aspire to the executive suite.

The burgeoning field of hospital medicine offers especially enticing rewards for business-minded doctors, inducing frontline leaders to trade the white coat for wing tips and a shot at the top.

The pinnacle can be stratospheric. Adam Singer, MD, CEO of California-based IPC-The Hospitalist Company, traded his white coat for the so-called C suite. He has since filed an initial public offering that should produce $105 million for IPC’s stakeholders.

There’s also lots of room for hospitalists with more modest executive aspirations. The skills acquired by good hospitalists—thoroughness, the ability to solve complex problems, critical thinking, strong motivation, sound work ethic, and teamwork—serve physician executives well. Some physicians back into the executive suite once they realize they’re attracted to the business end of medicine. Those are the clinicians who volunteer to do the group’s scheduling or find that they enjoy negotiating contracts with new hires and payers. Others pursue a personal road map to the C suite.

Balancing Act

The biggest decision facing a hospitalist with managerial aspirations is whether to relinquish patient care.

“For most of your career you must remain active clinically, even though your time is disjointed because you’re intensely needed in both clinical and administrative areas,” says Andrew Urbach, MD, medical director of clinical excellence and service at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He manages both by constantly adapting. His time had been evenly split between clinical and administrative duties until July, when he cut back on his clinical duties. He now spends one week every quarter as a hospitalist and a half-day a week at the clinic. “It’s difficult balancing both, and reaching the highest level of excellence in two areas is demanding,” he says. “But the best hospitalist managers continue to see patients to maintain credibility with their peers.”

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.-based Team Health, Hospital Medicine Division, was a staff hospitalist who ceded clinical work for a managerial career. After a three-year stint as a hospitalist with Covenant HealthCare’s hospital medicine program at Covenant Medical Center in Saginaw, Mich., her mentors recruited her to “jump around the country starting hospitalist programs during 2004 and 2005,” she says. “I was in the right place at the right time, and I had the confidence to move my agenda in a diplomatic way and with humor.”

Dr. Goldsholl reluctantly gave up clinical responsibilities three years ago. “It’s all about balance in my life,” she says. “It was a conscious decision to give up patient care. I miss it, but I wanted to take my career to a national level. I travel a great deal, which isn’t compatible with patient care.”

Business School

Hospitalists attracted to management often realize they need more business schooling, says Kevin Shulman, MD, MBA, professor of medicine and management at Duke University Medical Center and the Fuqua School of Business in Durham, N.C.

“The issues in medical training are clinical, not organizational,” he says. “As you move up in administration you don’t have business skills you need. When doctors feel frustrated about not being effective organizationally, that’s when they think about business school.”

Edward Ogata, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago, and a pediatric neonatologist, realized how useful an MBA would be as he moved from clinical work to management. “I went back to school for an MBA at Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management 27 years after graduating from medical school,” he says. Pushed by the healthcare market into negotiating managed-care contracts in the 1980s, Dr. Ogata realized he knew little about accounting and finance. The always-precarious financial situations of children’s hospitals encouraged him to get the business skills to cope.

At Kellogg, in Chicago, Dr. Ogata was assigned homework and teamwork with executives from Motorola, Lucent, and GE. The first year was difficult because he was still covering call and juggling administrative tasks. He got up at 4 a.m. every day to study. Armed with business skills, Dr. Ogata feels better equipped to meet the financial and administrative needs of his inner-city hospital. “We’re not in a nice suburb with a favorable payer mix, and a hospital isn’t really a business in the conventional sense,’’ he notes. “But we are committed to doing the best.”

For Joy Drass, MD, MBA, a critical care trauma surgeon for 13 years and president of Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., methodically performing clinical tasks prepared her for top management. She assumed the presidency of the troubled hospital in 2001, one year after MedStar Health in Columbia, Md., acquired it. The hospital had recorded losses in excess of $200 million before MedStar stepped in.

“Many skills I developed as a critical care physician had an absolute application in this stressed organization,” she says. “In medicine, it’s called triage. In business, it’s prioritizing. You look at a situation and quickly set goals to get from point A to point B, encourage team work, and develop structures to support people when they are struggling through uncertainty.” Skills she learned as a graduate of the Wharton business school in Philadelphia helped her stabilize hospital operations, improve customer service and revenue collection, and develop a long-term strategic plan to improve the hospital’s chances of survival.

Varied Paths

Some hospitalists acquire business smarts from instinct and experience. When he was 13 years old, Dr. Urbach ran his family’s retail business for weeks at a time when his parents were away.

“I’ve had no formal [business] school training, but my entrepreneurial instincts and management skills were honed early in life,” he says.

Team Health’s Dr. Goldsholl intended to get a formal MBA, but was too busy. “SHM’s Leadership Academy and other programs gave me management skills, and I chose CME credits in business and management areas,” she says. “I’m also more of an experiential than a classroom learner. Mentoring and other informal settings work for me.”

Michael Ruhlen, MD, MHM, Toledo (Ohio) Children’s Hospital corporate vice president of medical informatics and vice president of medical affairs, made a successful if not easy move from clinician to manager. Acting as a hospitalist seven years before the discipline was named in 1996, he developed systematic, data-driven clinical pathways and trained other would-be pediatric hospitalists in acute care pediatrics. In 2001 he was the first recipient of the National Association of Inpatient Physician’s Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine. The award recognized his managerial skill in building a hospitalist program from scratch.

Unlike hospitalists who are moving from well-defined clinical tracks to managerial roles, Dr. Ruhlen operated in uncharted territory in his first decade as a hospitalist. From the beginning of his hospitalist career, Dr. Ruhlen’s business head identified volume-dependent competency as critical to clinical and financial success. “I saw how to create time and quality efficiencies,” he explains. “If you do one or two lumbar punctures a year, you might stick a child five or six times. Doing a higher volume of procedures led to smoother operations.”

Recognizing the complexities of hospital management, Dr. Ruhlen returned to school to sharpen his management skills. He chose the Harvard School of Public Health’s master’s in healthcare management over an MBA because, as he puts it, “I’m interested in managing a hospital, not running Campbell’s Soup.” As a hospitalist executive, he works on improving the hospital’s IT systems, developing new physician leaders, and taking the lead on change management and patient safety issues. He also has been tapped twice to serve as acting hospital president.

Medicine as Business

Hospitalists enjoy an array of career choices. Those who savor the pure joy of clinical work can continue on that path, while others can choose a career in management; some can blend both. No matter what their career paths, healthcare’s increasing complexity will keep them fully occupied.

“As medicine grows more complex, students spend their time mastering clinical issues,” Dr. Shulman notes. “Many third-year med students don’t even know the difference between Medicaid and Medicare. As they practice as hospitalists and want to move up the administrative ranks, they will acquire the general business skills that will help them be effective and reshape healthcare policy.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a medical writer based in New York.

Many technically skilled professionals—including computer programmers, stockbrokers, or hospitalists—aspire to the executive suite.

The burgeoning field of hospital medicine offers especially enticing rewards for business-minded doctors, inducing frontline leaders to trade the white coat for wing tips and a shot at the top.

The pinnacle can be stratospheric. Adam Singer, MD, CEO of California-based IPC-The Hospitalist Company, traded his white coat for the so-called C suite. He has since filed an initial public offering that should produce $105 million for IPC’s stakeholders.

There’s also lots of room for hospitalists with more modest executive aspirations. The skills acquired by good hospitalists—thoroughness, the ability to solve complex problems, critical thinking, strong motivation, sound work ethic, and teamwork—serve physician executives well. Some physicians back into the executive suite once they realize they’re attracted to the business end of medicine. Those are the clinicians who volunteer to do the group’s scheduling or find that they enjoy negotiating contracts with new hires and payers. Others pursue a personal road map to the C suite.

Balancing Act

The biggest decision facing a hospitalist with managerial aspirations is whether to relinquish patient care.

“For most of your career you must remain active clinically, even though your time is disjointed because you’re intensely needed in both clinical and administrative areas,” says Andrew Urbach, MD, medical director of clinical excellence and service at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He manages both by constantly adapting. His time had been evenly split between clinical and administrative duties until July, when he cut back on his clinical duties. He now spends one week every quarter as a hospitalist and a half-day a week at the clinic. “It’s difficult balancing both, and reaching the highest level of excellence in two areas is demanding,” he says. “But the best hospitalist managers continue to see patients to maintain credibility with their peers.”

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.-based Team Health, Hospital Medicine Division, was a staff hospitalist who ceded clinical work for a managerial career. After a three-year stint as a hospitalist with Covenant HealthCare’s hospital medicine program at Covenant Medical Center in Saginaw, Mich., her mentors recruited her to “jump around the country starting hospitalist programs during 2004 and 2005,” she says. “I was in the right place at the right time, and I had the confidence to move my agenda in a diplomatic way and with humor.”

Dr. Goldsholl reluctantly gave up clinical responsibilities three years ago. “It’s all about balance in my life,” she says. “It was a conscious decision to give up patient care. I miss it, but I wanted to take my career to a national level. I travel a great deal, which isn’t compatible with patient care.”

Business School

Hospitalists attracted to management often realize they need more business schooling, says Kevin Shulman, MD, MBA, professor of medicine and management at Duke University Medical Center and the Fuqua School of Business in Durham, N.C.

“The issues in medical training are clinical, not organizational,” he says. “As you move up in administration you don’t have business skills you need. When doctors feel frustrated about not being effective organizationally, that’s when they think about business school.”

Edward Ogata, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago, and a pediatric neonatologist, realized how useful an MBA would be as he moved from clinical work to management. “I went back to school for an MBA at Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management 27 years after graduating from medical school,” he says. Pushed by the healthcare market into negotiating managed-care contracts in the 1980s, Dr. Ogata realized he knew little about accounting and finance. The always-precarious financial situations of children’s hospitals encouraged him to get the business skills to cope.

At Kellogg, in Chicago, Dr. Ogata was assigned homework and teamwork with executives from Motorola, Lucent, and GE. The first year was difficult because he was still covering call and juggling administrative tasks. He got up at 4 a.m. every day to study. Armed with business skills, Dr. Ogata feels better equipped to meet the financial and administrative needs of his inner-city hospital. “We’re not in a nice suburb with a favorable payer mix, and a hospital isn’t really a business in the conventional sense,’’ he notes. “But we are committed to doing the best.”

For Joy Drass, MD, MBA, a critical care trauma surgeon for 13 years and president of Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., methodically performing clinical tasks prepared her for top management. She assumed the presidency of the troubled hospital in 2001, one year after MedStar Health in Columbia, Md., acquired it. The hospital had recorded losses in excess of $200 million before MedStar stepped in.

“Many skills I developed as a critical care physician had an absolute application in this stressed organization,” she says. “In medicine, it’s called triage. In business, it’s prioritizing. You look at a situation and quickly set goals to get from point A to point B, encourage team work, and develop structures to support people when they are struggling through uncertainty.” Skills she learned as a graduate of the Wharton business school in Philadelphia helped her stabilize hospital operations, improve customer service and revenue collection, and develop a long-term strategic plan to improve the hospital’s chances of survival.

Varied Paths

Some hospitalists acquire business smarts from instinct and experience. When he was 13 years old, Dr. Urbach ran his family’s retail business for weeks at a time when his parents were away.

“I’ve had no formal [business] school training, but my entrepreneurial instincts and management skills were honed early in life,” he says.

Team Health’s Dr. Goldsholl intended to get a formal MBA, but was too busy. “SHM’s Leadership Academy and other programs gave me management skills, and I chose CME credits in business and management areas,” she says. “I’m also more of an experiential than a classroom learner. Mentoring and other informal settings work for me.”

Michael Ruhlen, MD, MHM, Toledo (Ohio) Children’s Hospital corporate vice president of medical informatics and vice president of medical affairs, made a successful if not easy move from clinician to manager. Acting as a hospitalist seven years before the discipline was named in 1996, he developed systematic, data-driven clinical pathways and trained other would-be pediatric hospitalists in acute care pediatrics. In 2001 he was the first recipient of the National Association of Inpatient Physician’s Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine. The award recognized his managerial skill in building a hospitalist program from scratch.

Unlike hospitalists who are moving from well-defined clinical tracks to managerial roles, Dr. Ruhlen operated in uncharted territory in his first decade as a hospitalist. From the beginning of his hospitalist career, Dr. Ruhlen’s business head identified volume-dependent competency as critical to clinical and financial success. “I saw how to create time and quality efficiencies,” he explains. “If you do one or two lumbar punctures a year, you might stick a child five or six times. Doing a higher volume of procedures led to smoother operations.”

Recognizing the complexities of hospital management, Dr. Ruhlen returned to school to sharpen his management skills. He chose the Harvard School of Public Health’s master’s in healthcare management over an MBA because, as he puts it, “I’m interested in managing a hospital, not running Campbell’s Soup.” As a hospitalist executive, he works on improving the hospital’s IT systems, developing new physician leaders, and taking the lead on change management and patient safety issues. He also has been tapped twice to serve as acting hospital president.

Medicine as Business

Hospitalists enjoy an array of career choices. Those who savor the pure joy of clinical work can continue on that path, while others can choose a career in management; some can blend both. No matter what their career paths, healthcare’s increasing complexity will keep them fully occupied.

“As medicine grows more complex, students spend their time mastering clinical issues,” Dr. Shulman notes. “Many third-year med students don’t even know the difference between Medicaid and Medicare. As they practice as hospitalists and want to move up the administrative ranks, they will acquire the general business skills that will help them be effective and reshape healthcare policy.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a medical writer based in New York.

Report Critical Care

Hospitalists often encounter patients who are or could become critically ill. The increased efforts while caring for these patients are best captured through critical-care service codes 99291 and 99292.

Although these codes yield higher reimbursement ($204.15 and $102.45, respectively, per national Medicare average payment), they are reported only under certain circumstances. The physician’s documentation must include enough detail to support critical-care claims: the patient’s condition, the nature of the physician’s care, and the time spent rendering care. Documentation of any other pertinent information is strongly encouraged because these services often come under payer scrutiny.

Condition and Care

A patient’s condition must meet the established criteria before the service qualifies as critical care. More specifically, the patient must have a critical illness or injury that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The physician’s personal attention (i.e., care involving one critically ill patient at a time) is essential for rendering the highly complex decisions necessary to prevent the patient’s decline if left untreated. Given the seriousness of the patient’s condition, the physician is expected to focus only on the patient for whom critical-care time is reported.

Duration

Critical care is a time-based service. It constitutes the physician’s time spent providing direct care at the bedside and gathering and reviewing data on the patient’s unit or floor.

If the physician is not immediately available to the patient, the time associated with indirect care (e.g., reviewing data, calling the family from the office) is not counted in the overall critical-care service.

The physician keeps tracks of his/her total critical-care time throughout the day. A new period of critical-care time begins each calendar day. There is no prohibition against reporting multiple hours or days of critical care, as long as the patient’s condition prompts the service and documentation supports it.

Code 99291 represents the first “hour” of critical care, which physicians may report after accumulating the first 30 minutes of care. Alternately, physician management of the patient involving less than 30 minutes of critical-care time on a given day must be reported with the appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) code:

- Initial inpatient service (99221-99223);

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233); or

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255).

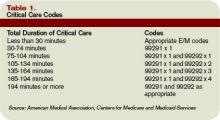

Once the physician achieves 75 minutes of critical-care time, he/she reports 99292 for the additional “30 minutes” of care beyond the first hour. Never report 99292 alone on the claim form. Code 99292 is considered an “add-on” code, which means it must be reported in addition to a primary code. Code 99291 is always the primary code (reported once per physician/group per day) for critical-care services. Code 99292 can be reported in multiple units per physician/group per day according to the number of minutes spent after the initial hour (see Table 1, p. 30).

Service Inclusions

Critical care involves highly complex decision making to manage the patient’s condition. This includes the physician’s performance and/or interpretation of labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures inherent in critical care.

Therefore, do not report the following services when billing 99291-99292:

- Cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562);

- Chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020);

- Pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); and

- Blood gases (multiple codes).

Further, don’t report interpretation of data stored in computers:

- Electrocardiograms, blood pressures, hematologic data (99090);

- Gastric intubation (43752, 91105);

- Temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953);

- Ventilation management (94002-94004, 94660, 94662); and

- Vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).

Any other service or procedure provided by the physician can be billed in addition to 99291-99292.

Be sure not to add separately billable procedure time into the physician’s total critical-care time. A notation in the medical record should reflect this (e.g., time spent inserting a central line is not included in today’s critical-care time).

Location

Because a patient can become seriously ill in any setting, physicians often provide critical-care services in emergency departments (EDs) and on standard medical-surgical floors before the patient is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Bed location alone does not determine critical-care reporting. Patients assigned to an ICU might be critically ill or injured and meet the “condition” requirements for 99291-99292.

However, the care provided may not meet the remaining requirements. According to the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology 2008 (Professional Edition) and the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, payment can be made for critical-care services provided in any location as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Services for a patient who is not critically ill and unstable but who happens to be receiving care in a critical-care, intensive-care, or other specialized-care unit are reported using subsequent hospital care codes 99231-99233 or hospital consultation codes 99251-99255. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Hospitalists often encounter patients who are or could become critically ill. The increased efforts while caring for these patients are best captured through critical-care service codes 99291 and 99292.

Although these codes yield higher reimbursement ($204.15 and $102.45, respectively, per national Medicare average payment), they are reported only under certain circumstances. The physician’s documentation must include enough detail to support critical-care claims: the patient’s condition, the nature of the physician’s care, and the time spent rendering care. Documentation of any other pertinent information is strongly encouraged because these services often come under payer scrutiny.

Condition and Care

A patient’s condition must meet the established criteria before the service qualifies as critical care. More specifically, the patient must have a critical illness or injury that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The physician’s personal attention (i.e., care involving one critically ill patient at a time) is essential for rendering the highly complex decisions necessary to prevent the patient’s decline if left untreated. Given the seriousness of the patient’s condition, the physician is expected to focus only on the patient for whom critical-care time is reported.

Duration

Critical care is a time-based service. It constitutes the physician’s time spent providing direct care at the bedside and gathering and reviewing data on the patient’s unit or floor.

If the physician is not immediately available to the patient, the time associated with indirect care (e.g., reviewing data, calling the family from the office) is not counted in the overall critical-care service.

The physician keeps tracks of his/her total critical-care time throughout the day. A new period of critical-care time begins each calendar day. There is no prohibition against reporting multiple hours or days of critical care, as long as the patient’s condition prompts the service and documentation supports it.

Code 99291 represents the first “hour” of critical care, which physicians may report after accumulating the first 30 minutes of care. Alternately, physician management of the patient involving less than 30 minutes of critical-care time on a given day must be reported with the appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) code:

- Initial inpatient service (99221-99223);

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233); or

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255).

Once the physician achieves 75 minutes of critical-care time, he/she reports 99292 for the additional “30 minutes” of care beyond the first hour. Never report 99292 alone on the claim form. Code 99292 is considered an “add-on” code, which means it must be reported in addition to a primary code. Code 99291 is always the primary code (reported once per physician/group per day) for critical-care services. Code 99292 can be reported in multiple units per physician/group per day according to the number of minutes spent after the initial hour (see Table 1, p. 30).

Service Inclusions

Critical care involves highly complex decision making to manage the patient’s condition. This includes the physician’s performance and/or interpretation of labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures inherent in critical care.

Therefore, do not report the following services when billing 99291-99292:

- Cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562);

- Chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020);

- Pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); and

- Blood gases (multiple codes).

Further, don’t report interpretation of data stored in computers:

- Electrocardiograms, blood pressures, hematologic data (99090);

- Gastric intubation (43752, 91105);

- Temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953);

- Ventilation management (94002-94004, 94660, 94662); and

- Vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).

Any other service or procedure provided by the physician can be billed in addition to 99291-99292.

Be sure not to add separately billable procedure time into the physician’s total critical-care time. A notation in the medical record should reflect this (e.g., time spent inserting a central line is not included in today’s critical-care time).

Location

Because a patient can become seriously ill in any setting, physicians often provide critical-care services in emergency departments (EDs) and on standard medical-surgical floors before the patient is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Bed location alone does not determine critical-care reporting. Patients assigned to an ICU might be critically ill or injured and meet the “condition” requirements for 99291-99292.

However, the care provided may not meet the remaining requirements. According to the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology 2008 (Professional Edition) and the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, payment can be made for critical-care services provided in any location as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Services for a patient who is not critically ill and unstable but who happens to be receiving care in a critical-care, intensive-care, or other specialized-care unit are reported using subsequent hospital care codes 99231-99233 or hospital consultation codes 99251-99255. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Hospitalists often encounter patients who are or could become critically ill. The increased efforts while caring for these patients are best captured through critical-care service codes 99291 and 99292.

Although these codes yield higher reimbursement ($204.15 and $102.45, respectively, per national Medicare average payment), they are reported only under certain circumstances. The physician’s documentation must include enough detail to support critical-care claims: the patient’s condition, the nature of the physician’s care, and the time spent rendering care. Documentation of any other pertinent information is strongly encouraged because these services often come under payer scrutiny.

Condition and Care

A patient’s condition must meet the established criteria before the service qualifies as critical care. More specifically, the patient must have a critical illness or injury that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The physician’s personal attention (i.e., care involving one critically ill patient at a time) is essential for rendering the highly complex decisions necessary to prevent the patient’s decline if left untreated. Given the seriousness of the patient’s condition, the physician is expected to focus only on the patient for whom critical-care time is reported.

Duration

Critical care is a time-based service. It constitutes the physician’s time spent providing direct care at the bedside and gathering and reviewing data on the patient’s unit or floor.

If the physician is not immediately available to the patient, the time associated with indirect care (e.g., reviewing data, calling the family from the office) is not counted in the overall critical-care service.

The physician keeps tracks of his/her total critical-care time throughout the day. A new period of critical-care time begins each calendar day. There is no prohibition against reporting multiple hours or days of critical care, as long as the patient’s condition prompts the service and documentation supports it.

Code 99291 represents the first “hour” of critical care, which physicians may report after accumulating the first 30 minutes of care. Alternately, physician management of the patient involving less than 30 minutes of critical-care time on a given day must be reported with the appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) code:

- Initial inpatient service (99221-99223);

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233); or

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255).

Once the physician achieves 75 minutes of critical-care time, he/she reports 99292 for the additional “30 minutes” of care beyond the first hour. Never report 99292 alone on the claim form. Code 99292 is considered an “add-on” code, which means it must be reported in addition to a primary code. Code 99291 is always the primary code (reported once per physician/group per day) for critical-care services. Code 99292 can be reported in multiple units per physician/group per day according to the number of minutes spent after the initial hour (see Table 1, p. 30).

Service Inclusions

Critical care involves highly complex decision making to manage the patient’s condition. This includes the physician’s performance and/or interpretation of labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures inherent in critical care.

Therefore, do not report the following services when billing 99291-99292:

- Cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562);

- Chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020);

- Pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); and

- Blood gases (multiple codes).

Further, don’t report interpretation of data stored in computers:

- Electrocardiograms, blood pressures, hematologic data (99090);

- Gastric intubation (43752, 91105);

- Temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953);

- Ventilation management (94002-94004, 94660, 94662); and

- Vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).

Any other service or procedure provided by the physician can be billed in addition to 99291-99292.

Be sure not to add separately billable procedure time into the physician’s total critical-care time. A notation in the medical record should reflect this (e.g., time spent inserting a central line is not included in today’s critical-care time).

Location

Because a patient can become seriously ill in any setting, physicians often provide critical-care services in emergency departments (EDs) and on standard medical-surgical floors before the patient is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Bed location alone does not determine critical-care reporting. Patients assigned to an ICU might be critically ill or injured and meet the “condition” requirements for 99291-99292.

However, the care provided may not meet the remaining requirements. According to the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology 2008 (Professional Edition) and the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, payment can be made for critical-care services provided in any location as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Services for a patient who is not critically ill and unstable but who happens to be receiving care in a critical-care, intensive-care, or other specialized-care unit are reported using subsequent hospital care codes 99231-99233 or hospital consultation codes 99251-99255. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

The OIG Aftermath

An increase in uninsured patients who show up in emergency departments (EDs), physician specialty shortages, and a physician population unwilling to take call all have led to a now-common practice: hospitals pay physician-specialists for on-call coverage of their EDs.

Though essential for providing adequate emergency care, this hospital-physician arrangement can violate anti-kickback laws. But recently, one hospital’s payments to on-call physicians was given an official federal stamp of approval. What does this official statement mean for hospital medicine groups and the hospitalists they employ?

Origins of the Opinion

In September 2007, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) issued an advisory opinion that a hospital that pays physicians for providing on-call and indigent care services in the ED does not violate the federal anti-kickback statute.

An unnamed medical center requested the opinion and submitted details on the comprehensive, detailed program it had created to ensure coverage of the ED.

The hospital’s program includes varied payment structures for staff physicians based on their participation in an on-call schedule for the ED and provision of inpatient follow-up care to patients seen while on call, among other actions.

The program applies to 18 specialties including hospitalists, and all participating physicians receive a per-diem payment for each on-call day.

Lou Glaser, partner at law firm of Sonnenschein Nath & Rosenthal, LLP, in Chicago, wrote the request.

“In this particular case, the hospital extended the program to nearly every specialty on the staff,” he explains. “Few hospitals have gone that far. But my client wanted to ensure that this program was appropriate and, if questioned, wanted to be able to say that they did everything possible to set up an appropriate program. They also, to the extent that if the OIG said no, wanted to be able to tell their physicians that they tried everything possible” to set up a fair payment system.

Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, chief medical officer at Cogent Healthcare in Irvine, Calif., and a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, is surprised the opinion was requested.

“It came out of the blue,” he says. “We weren’t worrying about it.” He believes the shortage of physicians willing to provide on-call care in the ED—particularly to uninsured patients—forces hospitals to create similar payment structures.

“The opinion basically says the OIG doesn’t frown on the current practice,” Dr. Greeno says. “There’s no reason they would—and if they did, it would mean a staffing crisis for all hospitals.” Part of this potential crisis includes care for uninsured patients, for which the hospital isn’t compensated.

Uninsured Patients

A pivotal point in the OIG opinion and in the problems hospitals have with ED on-call staffing is payment for care of uninsured patients—especially those who require an on-call physician at the ED in the middle of the night.

“My client wanted a solution to this, a solution that ensured their indigent patients would receive care from all necessary specialties,” says Glaser.

The payment program created by Glaser’s client hospitals was structured to include care for indigent patients. “The OIG latched on to that for a number of reasons,” says Glaser. “But basically it shows that physicians are being paid for something that they would not otherwise be paid for.”

Effect on Hospitalists

Though the OIG opinion doesn’t change status quo for most, it provides valuable guidance on what the government considers an acceptable plan for covering on-call shortages. Criteria outlined in the opinion include:

- There must be a clear, demonstrated need for the on-call service;

- Participating physicians would otherwise be un- or under-compensated for a meaningful portion of their work, such as caring for uninsured admissions;

- Participating physicians deliver defined added value such as better outcomes, or participation in quality initiatives; and

- Reimbursement reflects market value.

Because most hospitalists are employed by or supported by the hospital for which they are on call, they are entirely exempt from anti-kickback issues. Therefore, the OIG opinion won’t affect their on-call payments.

“The opinion obviously isn’t geared toward any specialty,” Glaser points out. “In fact, the OIG noted that the hospital could not select specific groups and try to steer money toward those. That said, hospitalists are in a slightly different position than other medical staff. They maintain their practice at the hospital, and depend on that for their volume and income.”

If your hospital medicine group is not supported primarily by the hospital, how can you ensure your on-call payments are legally acceptable?