User login

3 ... 2 ... 1 ... Moving Day

SHM is growing, changing, evolving and advancing. If you have been a member or been engaged with the society for the past few years, this isn’t news to you. Our membership is growing; the products, publications and services we offer are expanding; attendance at our annual meeting is increasing; and we are continuing to create new and valuable online resources. These are tangible signs of growth that many of you see and touch on a regular basis. On a day-to-day basis, I see the same things, but because I work for SHM, I have the opportunity to see the growth and change from within the organization.

When I signed on with SHM more than three years ago, I walked through the door and into a small office, approximately 3,000 square feet in size with about 13 full-time staff members. Since then, we have grown steadily, consistently adding new faces to the SHM team and expanding into new places by breaking through a wall into an adjacent space. Flash forward to the present day. Between April and July 2008, SHM has added 13 new faces to the staff. At the end of September 2008, we broke ground on construction of our new corporate headquarters, a 16,000-square-foot office in downtown Philadelphia.

Since its inception 12 years ago, SHM has called 190 Independence Mall home, but just as the hospital medicine movement has grown, so has SHM and the staff supporting the society. This winter, SHM will be moving our corporate headquarters to the new facility at 1500 Spring Garden. The process to find our new headquarters has been an extensive one. We began the search for a new office approximately one year ago, and as I am writing this, final construction documents have been sent to a list of general contractors.

During the past six months, SHM has been working with projects managers, architects, engineers, and consultants to take our new office from a “blank slate” to a finished and fully operational office before the end of 2008. As you read this article, construction on the new headquarters is fully underway. Workers are putting up drywall, running cables, laying carpet, and installing equipment that will be the supporting foundation for the staff and society for the next decade.

So, by now you are probably asking, “What does this mean to me? I don’t see these people on a daily basis, and I don’t work at SHM headquarters.” At a very basic level it means SHM will have a new address and new phone numbers. Your letters, applications, registrations, and anything addressed to SHM will be routed to our new home. Additionally, as part of our move, SHM will implement a new phone system. Our toll-free, 1-800 number will remain the same, however, all of the people who work for SHM will have new office phone numbers.

It is important you know how to reach SHM in our new home, but even more important is to know that this move is a significant milestone in the evolution of the society and the next step in providing you, our members, with ever-improving and enhanced levels of service and support. In creating a new facility, we are further equipping staff with the tools they need to serve you, creating technical capacities to meet current and future needs, and setting a stage for SHM’s continued growth in support of the growing hospital medicine movement.

During the weeks and months ahead, the SHM team will be preparing for the launch of the new One Day Hospitalist University, opening of the new Fellowship in Hospital Medicine and[Add Another New Program Here. In addition to all of these new and exciting initiatives, we will be organizing files, packing boxes and preparing for our move. As we transition to new desks, new phones, new commutes and a new environment, we would like to take a moment to thank you for your support and understanding while we take another significant step in the history of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Behind the Scenes

Change is in the air

By Geri Barnes

It’s autumn and there is a bite to the air. Every year around this time, I vacillate between being depressed about the pending winter and energized by the change of season. This year, I definitely am excited and energized.

As weather is one of those environmental dynamics that impacts daily life, so do changes in the healthcare arena impact on SHM and its life. We’ve seen “never events” come into being, an expansion of CMS’ Hospitals Compare, and an increasing focus on pay-for-performance. All of these factors are designed to improve patient care, particularly care of the hospitalized patient. SHM staff needs to be ready to support the hospital medicine community.

SHM long has been focused on defining and providing hospitalists with the education and resources needed for every day practice, as well as for imple- menting cutting-edge quality improvement interventions. To support these focus areas, our staff members were organized in one department, Education and Quality Initiatives. During the last year, we decided our efforts would be better served by creating two departments: Education and Meetings and Quality Initiatives. Last summer, we hired two new staff members to lead the department and move the quality efforts forward. Jane Kelly-Cummings, RN, CPHQ, senior director, Quality Initiatives, has more than 20 years of experience in clinical practice, quality improvement, patient safety, healthcare informatics and quality improvement education. Linda Boclair, MT (ASCP), MEd, MBA, brings to SHM 25 years of management in the healthcare industry and serves as the Quality Initiatives Department director. You will be hearing more about the Quality Initiatives Department in the near future.

I am heading up the newly organized Education and Meetings Department. I am joined by Erica Pearson, director, Meetings; Theresa Jones, education project manager; Meghan Pitzer, meetings coordinator; and Carolyn Brennan, director, Research Program Development. We are charged with managing SHM’s Education Enterprise, which includes meetings and all other educational activities that support our members.

For meetings, we focus on leading our volunteers in the development of relevant program and educational content, ensuring we meet the requirements for continuing medical education (CME) programs. We design and implement meeting logistics with a common goal: the attendees leave the meeting feeling nothing could have been better organized. The Education and Meetings staff has focused their energies on the following meetings:

- The cornerstone of our meetings is the SHM annual meeting. Hospital Medicine 2009 will take place May 14-17, 2009, in Chicago at the Hyatt Regency. The planning of the program and logistics began in March 2008, and the organizational effort will continue through the end of the meeting. This comprehensive program includes annual meeting education sessions over the course of two and a half days and another full day of seven concurrent pre-courses.

- An important educational event is SHM’s Leadership Academy. Established in 2005, the Level I Academy has been presented semi-annually, with the eighth event taking place in Los Angeles this past September. Based on a need for the next level of leadership skills, Level II started in 2006 and recently presented for the third time. All events have basically sold out, and their popularity continues to grow.

- SHM instituted the One-Day Hospitalist University (ODHU) series this year, presenting four of our best pre-courses on a regional basis. The goal is to present ODHU in four different locations during the course of the year. The first ODHU takes place this month in Baltimore; the next is Feb. 3-4 in Atlanta.

- Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2009 was held in July in Denver. As the lead sponsor, SHM organized this successful conference, which was co-sponsored by the American Pediatric Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Expert Training Sessions is a new series of educational events that provide the opportunity to learn quality improvement strategies for glycemic control, VTE prevention, or transitions of care directly from an expert and interact on a personal basis. Presented in Boston and Nashville and planned for St. Louis, this initiative already is proving successful and we are hoping to expand in the near future.

The other major focus area for the Education and Meetings Department lies in meeting the educational needs of the hospital medicine community. Staff, working with the Education Committee, are exploring new and exciting ways to identify needs and define strategies to deliver relevant programming. The efforts, which will lead to a comprehensive education plan that will drive the activities the next few years, are focused on the following:

- Life-long learning has become the standard for physicians in general and hospitalists in particular. SHM is in the early stages of identifying and developing resources that will be readily accessible on the SHM Web site, such as a hospital medicine reading list on clinical and healthcare-systems topics based on the Core Competencies.

- The Education Committee is exploring the possibility of developing an evidence-based medicine (EBM) primer, which can be used to practice and teach EBM. It will be designed for the practicing hospitalist in a community hospital setting and will define how to research, read, and use EBM journal articles.

- SHM is exploring the use of Web 2.0 to continually assess needs, deliver educational programs, and communicate with members and faculty.

- The needs of academic hospitalists are unique and SHM is dedicated to support this important segment of our constituency. Joining with the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), SHM is planning an Academic Boot Camp that will focus on education skills, research, mentoring, and career pathways.

- SHM is developing a comprehensive communication and education program to become the main resource for hospitalists as they engage in Maintenance of Certification.

So, the welcome winds of change blow, bringing the energy and organization needed to accomplish our education and quality goals. We are confident our internal changes will result in moving our agenda forward in ways previously only imagined.

Volunteer Search

Interested in being a part of an SHM Committee or Task Force? Now is your chance! Nominations are open for SHM Committees and Task Forces. This is your opportunity to shape the future of SHM and the hospital medicine movement.

To nominate yourself, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org and click on “About SHM,” then click on “Committees.” Here, you will see a full list of committees, as well as task forces and current members. For each committee you would like to serve on, please submit your name and a one- to two-paragraph statement about why you are qualified and interested. E-mail this information to Joi Seabrooks at [email protected] by Dec. 5. Appointments will be made in February, take affect in May and last one year. TH

SHM is growing, changing, evolving and advancing. If you have been a member or been engaged with the society for the past few years, this isn’t news to you. Our membership is growing; the products, publications and services we offer are expanding; attendance at our annual meeting is increasing; and we are continuing to create new and valuable online resources. These are tangible signs of growth that many of you see and touch on a regular basis. On a day-to-day basis, I see the same things, but because I work for SHM, I have the opportunity to see the growth and change from within the organization.

When I signed on with SHM more than three years ago, I walked through the door and into a small office, approximately 3,000 square feet in size with about 13 full-time staff members. Since then, we have grown steadily, consistently adding new faces to the SHM team and expanding into new places by breaking through a wall into an adjacent space. Flash forward to the present day. Between April and July 2008, SHM has added 13 new faces to the staff. At the end of September 2008, we broke ground on construction of our new corporate headquarters, a 16,000-square-foot office in downtown Philadelphia.

Since its inception 12 years ago, SHM has called 190 Independence Mall home, but just as the hospital medicine movement has grown, so has SHM and the staff supporting the society. This winter, SHM will be moving our corporate headquarters to the new facility at 1500 Spring Garden. The process to find our new headquarters has been an extensive one. We began the search for a new office approximately one year ago, and as I am writing this, final construction documents have been sent to a list of general contractors.

During the past six months, SHM has been working with projects managers, architects, engineers, and consultants to take our new office from a “blank slate” to a finished and fully operational office before the end of 2008. As you read this article, construction on the new headquarters is fully underway. Workers are putting up drywall, running cables, laying carpet, and installing equipment that will be the supporting foundation for the staff and society for the next decade.

So, by now you are probably asking, “What does this mean to me? I don’t see these people on a daily basis, and I don’t work at SHM headquarters.” At a very basic level it means SHM will have a new address and new phone numbers. Your letters, applications, registrations, and anything addressed to SHM will be routed to our new home. Additionally, as part of our move, SHM will implement a new phone system. Our toll-free, 1-800 number will remain the same, however, all of the people who work for SHM will have new office phone numbers.

It is important you know how to reach SHM in our new home, but even more important is to know that this move is a significant milestone in the evolution of the society and the next step in providing you, our members, with ever-improving and enhanced levels of service and support. In creating a new facility, we are further equipping staff with the tools they need to serve you, creating technical capacities to meet current and future needs, and setting a stage for SHM’s continued growth in support of the growing hospital medicine movement.

During the weeks and months ahead, the SHM team will be preparing for the launch of the new One Day Hospitalist University, opening of the new Fellowship in Hospital Medicine and[Add Another New Program Here. In addition to all of these new and exciting initiatives, we will be organizing files, packing boxes and preparing for our move. As we transition to new desks, new phones, new commutes and a new environment, we would like to take a moment to thank you for your support and understanding while we take another significant step in the history of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Behind the Scenes

Change is in the air

By Geri Barnes

It’s autumn and there is a bite to the air. Every year around this time, I vacillate between being depressed about the pending winter and energized by the change of season. This year, I definitely am excited and energized.

As weather is one of those environmental dynamics that impacts daily life, so do changes in the healthcare arena impact on SHM and its life. We’ve seen “never events” come into being, an expansion of CMS’ Hospitals Compare, and an increasing focus on pay-for-performance. All of these factors are designed to improve patient care, particularly care of the hospitalized patient. SHM staff needs to be ready to support the hospital medicine community.

SHM long has been focused on defining and providing hospitalists with the education and resources needed for every day practice, as well as for imple- menting cutting-edge quality improvement interventions. To support these focus areas, our staff members were organized in one department, Education and Quality Initiatives. During the last year, we decided our efforts would be better served by creating two departments: Education and Meetings and Quality Initiatives. Last summer, we hired two new staff members to lead the department and move the quality efforts forward. Jane Kelly-Cummings, RN, CPHQ, senior director, Quality Initiatives, has more than 20 years of experience in clinical practice, quality improvement, patient safety, healthcare informatics and quality improvement education. Linda Boclair, MT (ASCP), MEd, MBA, brings to SHM 25 years of management in the healthcare industry and serves as the Quality Initiatives Department director. You will be hearing more about the Quality Initiatives Department in the near future.

I am heading up the newly organized Education and Meetings Department. I am joined by Erica Pearson, director, Meetings; Theresa Jones, education project manager; Meghan Pitzer, meetings coordinator; and Carolyn Brennan, director, Research Program Development. We are charged with managing SHM’s Education Enterprise, which includes meetings and all other educational activities that support our members.

For meetings, we focus on leading our volunteers in the development of relevant program and educational content, ensuring we meet the requirements for continuing medical education (CME) programs. We design and implement meeting logistics with a common goal: the attendees leave the meeting feeling nothing could have been better organized. The Education and Meetings staff has focused their energies on the following meetings:

- The cornerstone of our meetings is the SHM annual meeting. Hospital Medicine 2009 will take place May 14-17, 2009, in Chicago at the Hyatt Regency. The planning of the program and logistics began in March 2008, and the organizational effort will continue through the end of the meeting. This comprehensive program includes annual meeting education sessions over the course of two and a half days and another full day of seven concurrent pre-courses.

- An important educational event is SHM’s Leadership Academy. Established in 2005, the Level I Academy has been presented semi-annually, with the eighth event taking place in Los Angeles this past September. Based on a need for the next level of leadership skills, Level II started in 2006 and recently presented for the third time. All events have basically sold out, and their popularity continues to grow.

- SHM instituted the One-Day Hospitalist University (ODHU) series this year, presenting four of our best pre-courses on a regional basis. The goal is to present ODHU in four different locations during the course of the year. The first ODHU takes place this month in Baltimore; the next is Feb. 3-4 in Atlanta.

- Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2009 was held in July in Denver. As the lead sponsor, SHM organized this successful conference, which was co-sponsored by the American Pediatric Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Expert Training Sessions is a new series of educational events that provide the opportunity to learn quality improvement strategies for glycemic control, VTE prevention, or transitions of care directly from an expert and interact on a personal basis. Presented in Boston and Nashville and planned for St. Louis, this initiative already is proving successful and we are hoping to expand in the near future.

The other major focus area for the Education and Meetings Department lies in meeting the educational needs of the hospital medicine community. Staff, working with the Education Committee, are exploring new and exciting ways to identify needs and define strategies to deliver relevant programming. The efforts, which will lead to a comprehensive education plan that will drive the activities the next few years, are focused on the following:

- Life-long learning has become the standard for physicians in general and hospitalists in particular. SHM is in the early stages of identifying and developing resources that will be readily accessible on the SHM Web site, such as a hospital medicine reading list on clinical and healthcare-systems topics based on the Core Competencies.

- The Education Committee is exploring the possibility of developing an evidence-based medicine (EBM) primer, which can be used to practice and teach EBM. It will be designed for the practicing hospitalist in a community hospital setting and will define how to research, read, and use EBM journal articles.

- SHM is exploring the use of Web 2.0 to continually assess needs, deliver educational programs, and communicate with members and faculty.

- The needs of academic hospitalists are unique and SHM is dedicated to support this important segment of our constituency. Joining with the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), SHM is planning an Academic Boot Camp that will focus on education skills, research, mentoring, and career pathways.

- SHM is developing a comprehensive communication and education program to become the main resource for hospitalists as they engage in Maintenance of Certification.

So, the welcome winds of change blow, bringing the energy and organization needed to accomplish our education and quality goals. We are confident our internal changes will result in moving our agenda forward in ways previously only imagined.

Volunteer Search

Interested in being a part of an SHM Committee or Task Force? Now is your chance! Nominations are open for SHM Committees and Task Forces. This is your opportunity to shape the future of SHM and the hospital medicine movement.

To nominate yourself, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org and click on “About SHM,” then click on “Committees.” Here, you will see a full list of committees, as well as task forces and current members. For each committee you would like to serve on, please submit your name and a one- to two-paragraph statement about why you are qualified and interested. E-mail this information to Joi Seabrooks at [email protected] by Dec. 5. Appointments will be made in February, take affect in May and last one year. TH

SHM is growing, changing, evolving and advancing. If you have been a member or been engaged with the society for the past few years, this isn’t news to you. Our membership is growing; the products, publications and services we offer are expanding; attendance at our annual meeting is increasing; and we are continuing to create new and valuable online resources. These are tangible signs of growth that many of you see and touch on a regular basis. On a day-to-day basis, I see the same things, but because I work for SHM, I have the opportunity to see the growth and change from within the organization.

When I signed on with SHM more than three years ago, I walked through the door and into a small office, approximately 3,000 square feet in size with about 13 full-time staff members. Since then, we have grown steadily, consistently adding new faces to the SHM team and expanding into new places by breaking through a wall into an adjacent space. Flash forward to the present day. Between April and July 2008, SHM has added 13 new faces to the staff. At the end of September 2008, we broke ground on construction of our new corporate headquarters, a 16,000-square-foot office in downtown Philadelphia.

Since its inception 12 years ago, SHM has called 190 Independence Mall home, but just as the hospital medicine movement has grown, so has SHM and the staff supporting the society. This winter, SHM will be moving our corporate headquarters to the new facility at 1500 Spring Garden. The process to find our new headquarters has been an extensive one. We began the search for a new office approximately one year ago, and as I am writing this, final construction documents have been sent to a list of general contractors.

During the past six months, SHM has been working with projects managers, architects, engineers, and consultants to take our new office from a “blank slate” to a finished and fully operational office before the end of 2008. As you read this article, construction on the new headquarters is fully underway. Workers are putting up drywall, running cables, laying carpet, and installing equipment that will be the supporting foundation for the staff and society for the next decade.

So, by now you are probably asking, “What does this mean to me? I don’t see these people on a daily basis, and I don’t work at SHM headquarters.” At a very basic level it means SHM will have a new address and new phone numbers. Your letters, applications, registrations, and anything addressed to SHM will be routed to our new home. Additionally, as part of our move, SHM will implement a new phone system. Our toll-free, 1-800 number will remain the same, however, all of the people who work for SHM will have new office phone numbers.

It is important you know how to reach SHM in our new home, but even more important is to know that this move is a significant milestone in the evolution of the society and the next step in providing you, our members, with ever-improving and enhanced levels of service and support. In creating a new facility, we are further equipping staff with the tools they need to serve you, creating technical capacities to meet current and future needs, and setting a stage for SHM’s continued growth in support of the growing hospital medicine movement.

During the weeks and months ahead, the SHM team will be preparing for the launch of the new One Day Hospitalist University, opening of the new Fellowship in Hospital Medicine and[Add Another New Program Here. In addition to all of these new and exciting initiatives, we will be organizing files, packing boxes and preparing for our move. As we transition to new desks, new phones, new commutes and a new environment, we would like to take a moment to thank you for your support and understanding while we take another significant step in the history of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Behind the Scenes

Change is in the air

By Geri Barnes

It’s autumn and there is a bite to the air. Every year around this time, I vacillate between being depressed about the pending winter and energized by the change of season. This year, I definitely am excited and energized.

As weather is one of those environmental dynamics that impacts daily life, so do changes in the healthcare arena impact on SHM and its life. We’ve seen “never events” come into being, an expansion of CMS’ Hospitals Compare, and an increasing focus on pay-for-performance. All of these factors are designed to improve patient care, particularly care of the hospitalized patient. SHM staff needs to be ready to support the hospital medicine community.

SHM long has been focused on defining and providing hospitalists with the education and resources needed for every day practice, as well as for imple- menting cutting-edge quality improvement interventions. To support these focus areas, our staff members were organized in one department, Education and Quality Initiatives. During the last year, we decided our efforts would be better served by creating two departments: Education and Meetings and Quality Initiatives. Last summer, we hired two new staff members to lead the department and move the quality efforts forward. Jane Kelly-Cummings, RN, CPHQ, senior director, Quality Initiatives, has more than 20 years of experience in clinical practice, quality improvement, patient safety, healthcare informatics and quality improvement education. Linda Boclair, MT (ASCP), MEd, MBA, brings to SHM 25 years of management in the healthcare industry and serves as the Quality Initiatives Department director. You will be hearing more about the Quality Initiatives Department in the near future.

I am heading up the newly organized Education and Meetings Department. I am joined by Erica Pearson, director, Meetings; Theresa Jones, education project manager; Meghan Pitzer, meetings coordinator; and Carolyn Brennan, director, Research Program Development. We are charged with managing SHM’s Education Enterprise, which includes meetings and all other educational activities that support our members.

For meetings, we focus on leading our volunteers in the development of relevant program and educational content, ensuring we meet the requirements for continuing medical education (CME) programs. We design and implement meeting logistics with a common goal: the attendees leave the meeting feeling nothing could have been better organized. The Education and Meetings staff has focused their energies on the following meetings:

- The cornerstone of our meetings is the SHM annual meeting. Hospital Medicine 2009 will take place May 14-17, 2009, in Chicago at the Hyatt Regency. The planning of the program and logistics began in March 2008, and the organizational effort will continue through the end of the meeting. This comprehensive program includes annual meeting education sessions over the course of two and a half days and another full day of seven concurrent pre-courses.

- An important educational event is SHM’s Leadership Academy. Established in 2005, the Level I Academy has been presented semi-annually, with the eighth event taking place in Los Angeles this past September. Based on a need for the next level of leadership skills, Level II started in 2006 and recently presented for the third time. All events have basically sold out, and their popularity continues to grow.

- SHM instituted the One-Day Hospitalist University (ODHU) series this year, presenting four of our best pre-courses on a regional basis. The goal is to present ODHU in four different locations during the course of the year. The first ODHU takes place this month in Baltimore; the next is Feb. 3-4 in Atlanta.

- Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2009 was held in July in Denver. As the lead sponsor, SHM organized this successful conference, which was co-sponsored by the American Pediatric Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Expert Training Sessions is a new series of educational events that provide the opportunity to learn quality improvement strategies for glycemic control, VTE prevention, or transitions of care directly from an expert and interact on a personal basis. Presented in Boston and Nashville and planned for St. Louis, this initiative already is proving successful and we are hoping to expand in the near future.

The other major focus area for the Education and Meetings Department lies in meeting the educational needs of the hospital medicine community. Staff, working with the Education Committee, are exploring new and exciting ways to identify needs and define strategies to deliver relevant programming. The efforts, which will lead to a comprehensive education plan that will drive the activities the next few years, are focused on the following:

- Life-long learning has become the standard for physicians in general and hospitalists in particular. SHM is in the early stages of identifying and developing resources that will be readily accessible on the SHM Web site, such as a hospital medicine reading list on clinical and healthcare-systems topics based on the Core Competencies.

- The Education Committee is exploring the possibility of developing an evidence-based medicine (EBM) primer, which can be used to practice and teach EBM. It will be designed for the practicing hospitalist in a community hospital setting and will define how to research, read, and use EBM journal articles.

- SHM is exploring the use of Web 2.0 to continually assess needs, deliver educational programs, and communicate with members and faculty.

- The needs of academic hospitalists are unique and SHM is dedicated to support this important segment of our constituency. Joining with the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), SHM is planning an Academic Boot Camp that will focus on education skills, research, mentoring, and career pathways.

- SHM is developing a comprehensive communication and education program to become the main resource for hospitalists as they engage in Maintenance of Certification.

So, the welcome winds of change blow, bringing the energy and organization needed to accomplish our education and quality goals. We are confident our internal changes will result in moving our agenda forward in ways previously only imagined.

Volunteer Search

Interested in being a part of an SHM Committee or Task Force? Now is your chance! Nominations are open for SHM Committees and Task Forces. This is your opportunity to shape the future of SHM and the hospital medicine movement.

To nominate yourself, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org and click on “About SHM,” then click on “Committees.” Here, you will see a full list of committees, as well as task forces and current members. For each committee you would like to serve on, please submit your name and a one- to two-paragraph statement about why you are qualified and interested. E-mail this information to Joi Seabrooks at [email protected] by Dec. 5. Appointments will be made in February, take affect in May and last one year. TH

SHM Explores Social Networks

Dear John Q. Hospitalist,

Recently, a pair of college students in our office presented an impressive summary of Web 2.0, including Facebook.com and LinkedIn.com, to the rest of the SHM staff.

As I listened to their presentation and heard the energy in their voices, I couldn’t help but think about my initial experience and excitement with the World Wide Web. Instead of doing homework, I spent many late nights searching the Internet looking for more information to help me create my first Web page. After countless hours of coding and debugging, as well as throwing the keyboard a time or two, I published my Web page and became a part of the Internet. I was hooked.

After listening to these students I was inspired to check out LinkedIn.com and create my own LinkedIn profile. While I did not stay up until the very early morning sending invites or completing every part of my profile, I found connections to old colleagues, college friends, high school buddies, and family members. Today, I eagerly await the flood of e-mail from people accepting me as a friend in their network, some of them members of SHM. I am hooked again.

Seeing SHM members on LinkedIn got me thinking about how SHM might use social networking technology. I think there is an opportunity here to create an interactive resource that will empower hospitalists to find other hospitalists, make connections, and build their own networks. I’m interested in getting your perspective. Do you think our members will use this type of an online resource?

Many social networking sites on the Internet grew out of individuals in an academic setting trying to find ways to connect with each other. I would imagine many of our student and resident members already are using social networking sites. Do you think this is the case? If so, what features and functions of a social networking tool do you think are most important? Is that different from a third-year resident, or a hospitalist who has been practicing hospital medicine for a number of years?

I know I have thrown a bunch of questions at you, so let me share with you some ideas and maybe we can begin a dialogue that will help SHM find ways in which we can leverage social networking and other Web 2.0 tools.

One of the tasks in creating a LinkedIn account is selecting the college or institution you attended and the years in which you attended. Immediately after setting up my account I was able to see the names of other alumni who attended my university during my four years and invite old friends to join my network. I can envision a scenario where an SHM member indicates which medical school he or she attended and is able to see a list of other colleagues who attended at the same time.

For the general member, someone who hasn’t attended a meeting, participated in a committee, or been more actively engaged in SHM, an online network might be a first step to increased involvement with SHM. Members could use this site to connect with other hospitalists in their area and share their interests and experience with others.

Along the way, they might learn about an SHM initiative they are interested in and connect with another hospitalist who working on this project and begin to have a dialogue. Throughout time, this person builds their network and establishes new connections. When it’s time to register for next year’s SHM Annual Meeting in Chicago, they already know a few faces in the crowd—and maybe a couple of them have become friends.

These are just a couple of ways I think SHM and our members might benefit from social networking. I am confident there are many, many more ways this technology can help our members and the hospital medicine community. What do you think? I would love to hear your thoughts and ideas. E-mail me at [email protected]. TH

Dear John Q. Hospitalist,

Recently, a pair of college students in our office presented an impressive summary of Web 2.0, including Facebook.com and LinkedIn.com, to the rest of the SHM staff.

As I listened to their presentation and heard the energy in their voices, I couldn’t help but think about my initial experience and excitement with the World Wide Web. Instead of doing homework, I spent many late nights searching the Internet looking for more information to help me create my first Web page. After countless hours of coding and debugging, as well as throwing the keyboard a time or two, I published my Web page and became a part of the Internet. I was hooked.

After listening to these students I was inspired to check out LinkedIn.com and create my own LinkedIn profile. While I did not stay up until the very early morning sending invites or completing every part of my profile, I found connections to old colleagues, college friends, high school buddies, and family members. Today, I eagerly await the flood of e-mail from people accepting me as a friend in their network, some of them members of SHM. I am hooked again.

Seeing SHM members on LinkedIn got me thinking about how SHM might use social networking technology. I think there is an opportunity here to create an interactive resource that will empower hospitalists to find other hospitalists, make connections, and build their own networks. I’m interested in getting your perspective. Do you think our members will use this type of an online resource?

Many social networking sites on the Internet grew out of individuals in an academic setting trying to find ways to connect with each other. I would imagine many of our student and resident members already are using social networking sites. Do you think this is the case? If so, what features and functions of a social networking tool do you think are most important? Is that different from a third-year resident, or a hospitalist who has been practicing hospital medicine for a number of years?

I know I have thrown a bunch of questions at you, so let me share with you some ideas and maybe we can begin a dialogue that will help SHM find ways in which we can leverage social networking and other Web 2.0 tools.

One of the tasks in creating a LinkedIn account is selecting the college or institution you attended and the years in which you attended. Immediately after setting up my account I was able to see the names of other alumni who attended my university during my four years and invite old friends to join my network. I can envision a scenario where an SHM member indicates which medical school he or she attended and is able to see a list of other colleagues who attended at the same time.

For the general member, someone who hasn’t attended a meeting, participated in a committee, or been more actively engaged in SHM, an online network might be a first step to increased involvement with SHM. Members could use this site to connect with other hospitalists in their area and share their interests and experience with others.

Along the way, they might learn about an SHM initiative they are interested in and connect with another hospitalist who working on this project and begin to have a dialogue. Throughout time, this person builds their network and establishes new connections. When it’s time to register for next year’s SHM Annual Meeting in Chicago, they already know a few faces in the crowd—and maybe a couple of them have become friends.

These are just a couple of ways I think SHM and our members might benefit from social networking. I am confident there are many, many more ways this technology can help our members and the hospital medicine community. What do you think? I would love to hear your thoughts and ideas. E-mail me at [email protected]. TH

Dear John Q. Hospitalist,

Recently, a pair of college students in our office presented an impressive summary of Web 2.0, including Facebook.com and LinkedIn.com, to the rest of the SHM staff.

As I listened to their presentation and heard the energy in their voices, I couldn’t help but think about my initial experience and excitement with the World Wide Web. Instead of doing homework, I spent many late nights searching the Internet looking for more information to help me create my first Web page. After countless hours of coding and debugging, as well as throwing the keyboard a time or two, I published my Web page and became a part of the Internet. I was hooked.

After listening to these students I was inspired to check out LinkedIn.com and create my own LinkedIn profile. While I did not stay up until the very early morning sending invites or completing every part of my profile, I found connections to old colleagues, college friends, high school buddies, and family members. Today, I eagerly await the flood of e-mail from people accepting me as a friend in their network, some of them members of SHM. I am hooked again.

Seeing SHM members on LinkedIn got me thinking about how SHM might use social networking technology. I think there is an opportunity here to create an interactive resource that will empower hospitalists to find other hospitalists, make connections, and build their own networks. I’m interested in getting your perspective. Do you think our members will use this type of an online resource?

Many social networking sites on the Internet grew out of individuals in an academic setting trying to find ways to connect with each other. I would imagine many of our student and resident members already are using social networking sites. Do you think this is the case? If so, what features and functions of a social networking tool do you think are most important? Is that different from a third-year resident, or a hospitalist who has been practicing hospital medicine for a number of years?

I know I have thrown a bunch of questions at you, so let me share with you some ideas and maybe we can begin a dialogue that will help SHM find ways in which we can leverage social networking and other Web 2.0 tools.

One of the tasks in creating a LinkedIn account is selecting the college or institution you attended and the years in which you attended. Immediately after setting up my account I was able to see the names of other alumni who attended my university during my four years and invite old friends to join my network. I can envision a scenario where an SHM member indicates which medical school he or she attended and is able to see a list of other colleagues who attended at the same time.

For the general member, someone who hasn’t attended a meeting, participated in a committee, or been more actively engaged in SHM, an online network might be a first step to increased involvement with SHM. Members could use this site to connect with other hospitalists in their area and share their interests and experience with others.

Along the way, they might learn about an SHM initiative they are interested in and connect with another hospitalist who working on this project and begin to have a dialogue. Throughout time, this person builds their network and establishes new connections. When it’s time to register for next year’s SHM Annual Meeting in Chicago, they already know a few faces in the crowd—and maybe a couple of them have become friends.

These are just a couple of ways I think SHM and our members might benefit from social networking. I am confident there are many, many more ways this technology can help our members and the hospital medicine community. What do you think? I would love to hear your thoughts and ideas. E-mail me at [email protected]. TH

SHM Forms Hospitalist IT Task Force

Do you speak geek? If you haven’t already, you may hear that phrase or something similar in the halls of your hospital or institution.

As hospitals face the challenge of implementing computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and electronic medical records (EMRs), many hospitals are turning to hospitalists to help guide them through the complex and daunting task of translating a critical initiative into an information technology (IT) success story. More and more, hospitalists are asked to play any number of roles in leading their institution to the IT Promised Land. Are you one of these people? Do you want to be? Not sure how to get started or where to turn for help? Look no further—SHM is here to help.

Late last year, SHM convened a small group of hospitalists with extensive IT experience. The meeting led to the formation of SHM’s new Hospitalist IT Task Force and a list of initiatives to help those of you interested in bridging the gap between the hospital and IT. In addition to this laundry list of ideas, the group described a set of roles a hospitalist can play in facilitating a CPOE or other IT project. Hospitalists involved in IT can act as:

Communicators: There are gaps in knowledge and understanding between physicians and IT staff. Medical staff members might not understand the IT vocabulary/processes, while the IT staff might not be familiar with medical vocabulary/processes. Hospitalists must translate the clinical needs of the hospital for the IT community when implementing programs like CPOE.

Champions: Every project needs a champion to have a chance at success. Knowledgeable hospitalists can communicate the value of IT initiatives to the hospital and drive these projects to a positive conclusion. Hospitalists understand the implications of transitioning from a paper to electronic environment and can engage the right people and resources to support these initiatives.

Experienced leaders (power users): There is a growing community of hospitalists who have implemented CPOE/EMR and other IT initiatives. They have been in the trenches. They know what works and what doesn’t, and they understand the pros and cons of different solutions. They are power users of medical IT and possess significant knowledge that can help others.

Reviewers: Each hospital has to select a technical solution that fits its administrative and clinical needs. The hospital will evaluate multiple options and selecting the appropriate solution. Hospitalists who play the roles of communicator, champion, and/or experienced leader can be valuable when solutions are being reviewed and evaluated.

Have you served in one of these roles? Would you like to get more involved in IT? SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is exploring different ways to assist our members. Potential initiatives include:

- Developing an online resource of articles, reference material, and Web sites that provide guidance and support related to IT in a hospital setting;

- Holding an open forum at Hospital Medicine 2008, SHM’s Annual Meeting from April 3-5 in San Diego, to discuss the roles, challenges, successes, and pitfalls encountered in IT initiatives; and

- Creating other educational vehicles for hospitalists working with IT in their hospital.

The success of an IT project depends on having the right people at the table. They are committed to success, they make open and honest contributions, and they work to align the needs of the organization with the capabilities of the technical solution by taking users’ needs into full consideration.

SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is working to develop the right solutions to help you improve your hospital or project. If you are one of our hospitalist IT users and have an opinion, idea, or experience you would like to share, we would like to hear from you. Contact the Hospitalist IT Task Force at [email protected]. TH

Do you speak geek? If you haven’t already, you may hear that phrase or something similar in the halls of your hospital or institution.

As hospitals face the challenge of implementing computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and electronic medical records (EMRs), many hospitals are turning to hospitalists to help guide them through the complex and daunting task of translating a critical initiative into an information technology (IT) success story. More and more, hospitalists are asked to play any number of roles in leading their institution to the IT Promised Land. Are you one of these people? Do you want to be? Not sure how to get started or where to turn for help? Look no further—SHM is here to help.

Late last year, SHM convened a small group of hospitalists with extensive IT experience. The meeting led to the formation of SHM’s new Hospitalist IT Task Force and a list of initiatives to help those of you interested in bridging the gap between the hospital and IT. In addition to this laundry list of ideas, the group described a set of roles a hospitalist can play in facilitating a CPOE or other IT project. Hospitalists involved in IT can act as:

Communicators: There are gaps in knowledge and understanding between physicians and IT staff. Medical staff members might not understand the IT vocabulary/processes, while the IT staff might not be familiar with medical vocabulary/processes. Hospitalists must translate the clinical needs of the hospital for the IT community when implementing programs like CPOE.

Champions: Every project needs a champion to have a chance at success. Knowledgeable hospitalists can communicate the value of IT initiatives to the hospital and drive these projects to a positive conclusion. Hospitalists understand the implications of transitioning from a paper to electronic environment and can engage the right people and resources to support these initiatives.

Experienced leaders (power users): There is a growing community of hospitalists who have implemented CPOE/EMR and other IT initiatives. They have been in the trenches. They know what works and what doesn’t, and they understand the pros and cons of different solutions. They are power users of medical IT and possess significant knowledge that can help others.

Reviewers: Each hospital has to select a technical solution that fits its administrative and clinical needs. The hospital will evaluate multiple options and selecting the appropriate solution. Hospitalists who play the roles of communicator, champion, and/or experienced leader can be valuable when solutions are being reviewed and evaluated.

Have you served in one of these roles? Would you like to get more involved in IT? SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is exploring different ways to assist our members. Potential initiatives include:

- Developing an online resource of articles, reference material, and Web sites that provide guidance and support related to IT in a hospital setting;

- Holding an open forum at Hospital Medicine 2008, SHM’s Annual Meeting from April 3-5 in San Diego, to discuss the roles, challenges, successes, and pitfalls encountered in IT initiatives; and

- Creating other educational vehicles for hospitalists working with IT in their hospital.

The success of an IT project depends on having the right people at the table. They are committed to success, they make open and honest contributions, and they work to align the needs of the organization with the capabilities of the technical solution by taking users’ needs into full consideration.

SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is working to develop the right solutions to help you improve your hospital or project. If you are one of our hospitalist IT users and have an opinion, idea, or experience you would like to share, we would like to hear from you. Contact the Hospitalist IT Task Force at [email protected]. TH

Do you speak geek? If you haven’t already, you may hear that phrase or something similar in the halls of your hospital or institution.

As hospitals face the challenge of implementing computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and electronic medical records (EMRs), many hospitals are turning to hospitalists to help guide them through the complex and daunting task of translating a critical initiative into an information technology (IT) success story. More and more, hospitalists are asked to play any number of roles in leading their institution to the IT Promised Land. Are you one of these people? Do you want to be? Not sure how to get started or where to turn for help? Look no further—SHM is here to help.

Late last year, SHM convened a small group of hospitalists with extensive IT experience. The meeting led to the formation of SHM’s new Hospitalist IT Task Force and a list of initiatives to help those of you interested in bridging the gap between the hospital and IT. In addition to this laundry list of ideas, the group described a set of roles a hospitalist can play in facilitating a CPOE or other IT project. Hospitalists involved in IT can act as:

Communicators: There are gaps in knowledge and understanding between physicians and IT staff. Medical staff members might not understand the IT vocabulary/processes, while the IT staff might not be familiar with medical vocabulary/processes. Hospitalists must translate the clinical needs of the hospital for the IT community when implementing programs like CPOE.

Champions: Every project needs a champion to have a chance at success. Knowledgeable hospitalists can communicate the value of IT initiatives to the hospital and drive these projects to a positive conclusion. Hospitalists understand the implications of transitioning from a paper to electronic environment and can engage the right people and resources to support these initiatives.

Experienced leaders (power users): There is a growing community of hospitalists who have implemented CPOE/EMR and other IT initiatives. They have been in the trenches. They know what works and what doesn’t, and they understand the pros and cons of different solutions. They are power users of medical IT and possess significant knowledge that can help others.

Reviewers: Each hospital has to select a technical solution that fits its administrative and clinical needs. The hospital will evaluate multiple options and selecting the appropriate solution. Hospitalists who play the roles of communicator, champion, and/or experienced leader can be valuable when solutions are being reviewed and evaluated.

Have you served in one of these roles? Would you like to get more involved in IT? SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is exploring different ways to assist our members. Potential initiatives include:

- Developing an online resource of articles, reference material, and Web sites that provide guidance and support related to IT in a hospital setting;

- Holding an open forum at Hospital Medicine 2008, SHM’s Annual Meeting from April 3-5 in San Diego, to discuss the roles, challenges, successes, and pitfalls encountered in IT initiatives; and

- Creating other educational vehicles for hospitalists working with IT in their hospital.

The success of an IT project depends on having the right people at the table. They are committed to success, they make open and honest contributions, and they work to align the needs of the organization with the capabilities of the technical solution by taking users’ needs into full consideration.

SHM’s Hospitalist IT Task Force is working to develop the right solutions to help you improve your hospital or project. If you are one of our hospitalist IT users and have an opinion, idea, or experience you would like to share, we would like to hear from you. Contact the Hospitalist IT Task Force at [email protected]. TH

An Information Services Update

As I sit here brainstorming the latest and greatest news from SHM and the folks at Information Services, it surprised me to realize that I have been with SHM for exactly two years.

When I look back at some of our accomplishments—launching a brand new SHM Web site, creating six new Web-based resource rooms around specific disease states, launching an online career center for hospitalists, and opening a hospitalist legislative advocacy center—I can’t help but think about the talented people who have brought us this far and how they will make your experience with SHM even more valuable and exciting in the years to come.

Our interactive designer, Bruce Hansen, came to SHM with a variety of skills and life experiences, including time spent working with the Peace Corps in the Ukraine. Bruce is our ace Web guru at SHM, and not only is he responsible for SHM’s Web site, but he also leads the development of the resource rooms that many of our members have come to use as a resource in their daily professional lives. Through Bruce’s leadership and intense dedication to making our Web site as easy for each of you to use as possible, you will begin to see dramatic improvements in the format of SHM’s Web site homepage. Coming in the summer of 2007, we will also be launching improvements on how to navigate and move through the Web site, making it much easier to get to the information you need.

In the Web-sphere, cool graphics and easy-to-use links are important, but content is king, and that has been the primary focus of our project assistant, Lubna Manna. Lubna came to SHM with a background in creating programs for PDAs and phones, which she will be drawing from as SHM begins to introduce resources for iPods and other handheld devices. In addition to helping many of our members with questions about our Web site, Lubna has been working with the staff at SHM to find new and dynamic ways to present the information you need, when you need it, through our Web site. Understanding how many of you currently use our Web site has given us a glimpse into what matters most, and Lubna is finding ways to change how and where we deliver information via the Web to make sure it is easy for you to find the information you need.

Our most recent addition to the Information Services team, Travis Kamps, our Web production assistant, is a wizard of sorts when it comes to anything new or cool on the Web or in other technologies. Over the next couple of months, Travis will work hand in hand with Bruce to create resource rooms that are easier to use and provide you with ways to access these quality improvement resources, whether you are just starting out in QI or are an old pro. With Travis’ help and guidance, we will also begin to see how the Internet and SHM can foster an online community in which hospitalists can network, share ideas and questions, and create a collaborative environment from which all of our members can benefit.

Of course, in any organization, there are many things that go on behind the scenes that others don’t see or know about. Have you ever wondered where all the maintenance and support staff at Disneyworld work? Believe it or not, they are just below your feet as you stroll down Main Street. In Information Services, a lot of what we do is just below your feet or behind the scenes, but we are here, and we are dedicated to finding new, creative, and innovative ways to ensure that you get the biggest bang for your buck from your SHM membership.

In the coming months, you will see improvements to your membership experience through the Web site, at the 2007 Annual Meeting, and in the products and services that are all part of your SHM membership. We are always trying to find new ways to provide you with the resources you need to make a difference in your hospital and in the healthcare that you provide. With your help and support, I am confident that the next two years will be exciting and valuable to you. TH

As I sit here brainstorming the latest and greatest news from SHM and the folks at Information Services, it surprised me to realize that I have been with SHM for exactly two years.

When I look back at some of our accomplishments—launching a brand new SHM Web site, creating six new Web-based resource rooms around specific disease states, launching an online career center for hospitalists, and opening a hospitalist legislative advocacy center—I can’t help but think about the talented people who have brought us this far and how they will make your experience with SHM even more valuable and exciting in the years to come.

Our interactive designer, Bruce Hansen, came to SHM with a variety of skills and life experiences, including time spent working with the Peace Corps in the Ukraine. Bruce is our ace Web guru at SHM, and not only is he responsible for SHM’s Web site, but he also leads the development of the resource rooms that many of our members have come to use as a resource in their daily professional lives. Through Bruce’s leadership and intense dedication to making our Web site as easy for each of you to use as possible, you will begin to see dramatic improvements in the format of SHM’s Web site homepage. Coming in the summer of 2007, we will also be launching improvements on how to navigate and move through the Web site, making it much easier to get to the information you need.

In the Web-sphere, cool graphics and easy-to-use links are important, but content is king, and that has been the primary focus of our project assistant, Lubna Manna. Lubna came to SHM with a background in creating programs for PDAs and phones, which she will be drawing from as SHM begins to introduce resources for iPods and other handheld devices. In addition to helping many of our members with questions about our Web site, Lubna has been working with the staff at SHM to find new and dynamic ways to present the information you need, when you need it, through our Web site. Understanding how many of you currently use our Web site has given us a glimpse into what matters most, and Lubna is finding ways to change how and where we deliver information via the Web to make sure it is easy for you to find the information you need.

Our most recent addition to the Information Services team, Travis Kamps, our Web production assistant, is a wizard of sorts when it comes to anything new or cool on the Web or in other technologies. Over the next couple of months, Travis will work hand in hand with Bruce to create resource rooms that are easier to use and provide you with ways to access these quality improvement resources, whether you are just starting out in QI or are an old pro. With Travis’ help and guidance, we will also begin to see how the Internet and SHM can foster an online community in which hospitalists can network, share ideas and questions, and create a collaborative environment from which all of our members can benefit.

Of course, in any organization, there are many things that go on behind the scenes that others don’t see or know about. Have you ever wondered where all the maintenance and support staff at Disneyworld work? Believe it or not, they are just below your feet as you stroll down Main Street. In Information Services, a lot of what we do is just below your feet or behind the scenes, but we are here, and we are dedicated to finding new, creative, and innovative ways to ensure that you get the biggest bang for your buck from your SHM membership.

In the coming months, you will see improvements to your membership experience through the Web site, at the 2007 Annual Meeting, and in the products and services that are all part of your SHM membership. We are always trying to find new ways to provide you with the resources you need to make a difference in your hospital and in the healthcare that you provide. With your help and support, I am confident that the next two years will be exciting and valuable to you. TH

As I sit here brainstorming the latest and greatest news from SHM and the folks at Information Services, it surprised me to realize that I have been with SHM for exactly two years.

When I look back at some of our accomplishments—launching a brand new SHM Web site, creating six new Web-based resource rooms around specific disease states, launching an online career center for hospitalists, and opening a hospitalist legislative advocacy center—I can’t help but think about the talented people who have brought us this far and how they will make your experience with SHM even more valuable and exciting in the years to come.

Our interactive designer, Bruce Hansen, came to SHM with a variety of skills and life experiences, including time spent working with the Peace Corps in the Ukraine. Bruce is our ace Web guru at SHM, and not only is he responsible for SHM’s Web site, but he also leads the development of the resource rooms that many of our members have come to use as a resource in their daily professional lives. Through Bruce’s leadership and intense dedication to making our Web site as easy for each of you to use as possible, you will begin to see dramatic improvements in the format of SHM’s Web site homepage. Coming in the summer of 2007, we will also be launching improvements on how to navigate and move through the Web site, making it much easier to get to the information you need.

In the Web-sphere, cool graphics and easy-to-use links are important, but content is king, and that has been the primary focus of our project assistant, Lubna Manna. Lubna came to SHM with a background in creating programs for PDAs and phones, which she will be drawing from as SHM begins to introduce resources for iPods and other handheld devices. In addition to helping many of our members with questions about our Web site, Lubna has been working with the staff at SHM to find new and dynamic ways to present the information you need, when you need it, through our Web site. Understanding how many of you currently use our Web site has given us a glimpse into what matters most, and Lubna is finding ways to change how and where we deliver information via the Web to make sure it is easy for you to find the information you need.

Our most recent addition to the Information Services team, Travis Kamps, our Web production assistant, is a wizard of sorts when it comes to anything new or cool on the Web or in other technologies. Over the next couple of months, Travis will work hand in hand with Bruce to create resource rooms that are easier to use and provide you with ways to access these quality improvement resources, whether you are just starting out in QI or are an old pro. With Travis’ help and guidance, we will also begin to see how the Internet and SHM can foster an online community in which hospitalists can network, share ideas and questions, and create a collaborative environment from which all of our members can benefit.

Of course, in any organization, there are many things that go on behind the scenes that others don’t see or know about. Have you ever wondered where all the maintenance and support staff at Disneyworld work? Believe it or not, they are just below your feet as you stroll down Main Street. In Information Services, a lot of what we do is just below your feet or behind the scenes, but we are here, and we are dedicated to finding new, creative, and innovative ways to ensure that you get the biggest bang for your buck from your SHM membership.

In the coming months, you will see improvements to your membership experience through the Web site, at the 2007 Annual Meeting, and in the products and services that are all part of your SHM membership. We are always trying to find new ways to provide you with the resources you need to make a difference in your hospital and in the healthcare that you provide. With your help and support, I am confident that the next two years will be exciting and valuable to you. TH

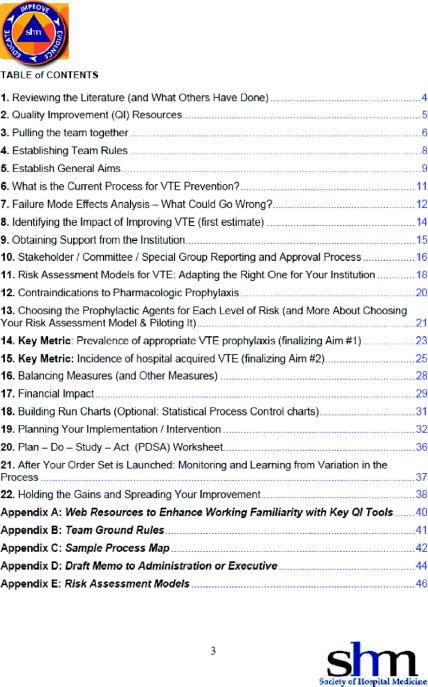

The Venous Thromboembolism Quality Improvement Resource Room

The goal of this article is to explain how the first in a series of online resource rooms provides trainees and hospitalists with quality improvement tools that can be applied locally to improve inpatient care.1 During the emergence and explosive growth of hospital medicine, the SHM recognized the need to revise training relating to inpatient care and hospital process design to meet the evolving expectation of hospitalists that their performance will be measured, to actively set quality parameters, and to lead multidisciplinary teams to improve hospital performance.2 Armed with the appropriate skill set, hospitalists would be uniquely situated to lead and manage improvements in processes in the hospitals in which they work.

The content of the first Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Quality Improvement Resource Room (QI RR) supports hospitalists leading a multidisciplinary team dedicated to improving inpatient outcomes by preventing hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE), a common cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitalized patients.3 The SHM developed this educational resource in the context of numerous reports on the incidence of medical errors in US hospitals and calls for action to improve the quality of health care.'47 Hospital report cards on quality measures are now public record, and hospitals will require uniformity in practice among physicians. Hospitalists are increasingly expected to lead initiatives that will implement national standards in key practices such as VTE prophylaxis2.

The QI RRs of the SHM are a collection of electronic tools accessible through the SHM Web site. They are designed to enhance the readiness of hospitalists and members of the multidisciplinary inpatient team to redesign care at the institutional level. Although all performance improvement is ultimately occurs locally, many QI methods and tools transcend hospital geography and disease topic. Leveraging a Web‐based platform, the SHM QI RRs present hospitalists with a general approach to QI, enriched by customizable workbooks that can be downloaded to best meet user needs. This resource is an innovation in practice‐based learning, quality improvement, and systems‐based practice.

METHODS

Development of the first QI RR followed a series of steps described in Curriculum Development for Medical Education8 (for process and timeline, see Table 1). Inadequate VTE prophylaxis was identified as an ongoing widespread problem of health care underutilization despite randomized clinical trials supporting the efficacy of prophylaxis.9, 10 Mirroring the AHRQ's assessment of underutilization of VTE prophylaxis as the single most important safety priority,6 the first QI RR focused on VTE, with plans to cover additional clinical conditions over time. As experts in the care of inpatients, hospitalists should be able to take custody of predictable complications of serious illness, identify and lower barriers to prevention, critically review prophylaxis options, utilize hospital‐specific data, and devise strategies to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice. Already leaders of multidisciplinary care teams, hospitalists are primed to lead multidisciplinary improvement teams as well.

| Phase 1 (January 2005April 2005): Executing the educational strategy |

|---|

| One‐hour conference calls |

| Curricular, clinical, technical, and creative aspects of production |

| Additional communication between members of working group between calls |

| Development of questionnaire for SHM membership, board, education, and hospital quality patient safety (HQPS) committees |

| Content freeze: fourth month of development |

| Implementation of revisions prior to April 2005 SHM Annual Meeting |

| Phase 2 (April 2005August 2005): revision based on feedback |

| Analysis of formative evaluation from Phase 1 |

| Launch of the VTE QI RR August 2005 |

| Secondary phases and venues for implementation |

| Workshops at hospital medicine educational events |

| SHM Quality course |

| Formal recognition of the learning, experience, or proficiency acquired by users |

| The working editorial team for the first resource room |

| Dedicated project manager (SHM staff) |

| Senior adviser for planning and development (SHM staff) |

| Senior adviser for education (SHM staff) |

| Content expert |

| Education editor |

| Hospital quality editor |

| Managing editor |

Available data on the demographics of hospitalists and feedback from the SHM membership, leadership, and committees indicated that most learners would have minimal previous exposure to QI concepts and only a few years of management experience. Any previous quality improvement initiatives would tend to have been isolated, experimental, or smaller in scale. The resource rooms are designed to facilitate quality improvement learning among hospitalists that is practice‐based and immediately relevant to patient care. Measurable improvement in particular care processes or outcomes should correlate with actual learning.

The educational strategy of the SHM was predicated on ensuring that a quality and patient safety curriculum would retain clinical applicability in the hospital setting. This approach, grounded in adult learning principles and common to medical education, teaches general principles by framing the learning experience as problem centered.11 Several domains were identified as universally important to any quality improvement effort: raising awareness of a local performance gap, applying the best current evidence to practice, tapping the experience of others leading QI efforts, and using measurements derived from rapid‐cycle tests of change. Such a template delineates the components of successful QI planning, implementation, and evaluation and provides users with a familiar RR format applicable to improving any care process, not just VTE.

The Internet was chosen as the mechanism for delivering training on the basis of previous surveys of the SHM membership in which members expressed a preference for electronic and Web‐based forms of educational content delivery. Drawing from the example of other organizations teaching quality improvement, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Intermountain Health Care, the SHM valued the ubiquity of a Web‐based educational resource. To facilitate on‐the‐job training, the first SHM QI RR provides a comprehensive tool kit to guide hospitalists through the process of advocating, developing, implementing, and evaluating a QI initiative for VTE.

Prior to launching the resource room, formative input was collected from SHM leaders, a panel of education and QI experts, and attendees of the society's annual meetings. Such input followed each significant step in the development of the RR curricula. For example, visitors at a kiosk at the 2005 SHM annual meeting completed surveys as they navigated through the VTE QI RR. This focused feedback shaped prelaunch development. The ultimate performance evaluation and feedback for the QI RR curricula will be gauged by user reports of measurable improvement in specific hospital process or outcomes measures. The VTE QI RR was launched in August 2005 and promoted at the SHM Web site.

RESULTS

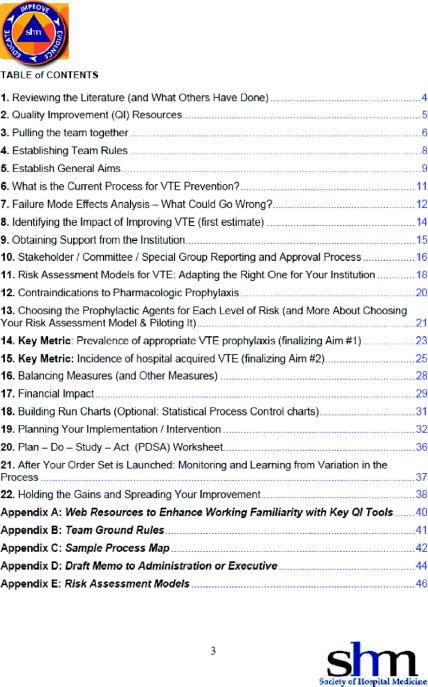

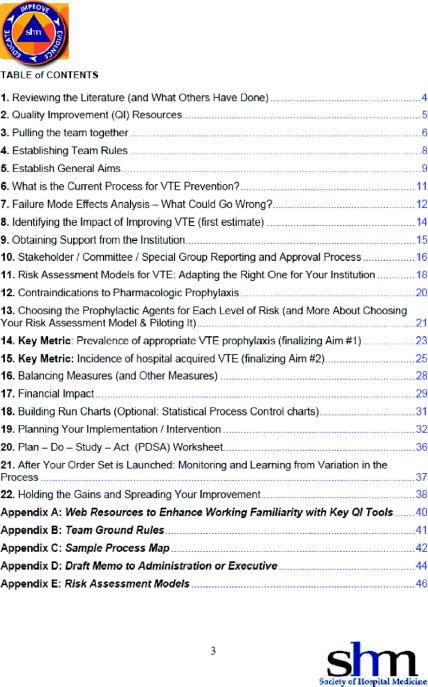

The content and layout of the VTE QI RR are depicted in Figure 1. The self‐directed learner may navigate through the entire resource room or just select areas for study. Those likely to visit only a single area are individuals looking for guidance to support discrete roles on the improvement team: champion, clinical leader, facilitator of the QI process, or educator of staff or patient audiences (see Figure 2).

Why Should You Act?

The visual center of the QI RR layout presents sobering statisticsalthough pulmonary embolism from deep vein thrombosis is the most common cause of preventable hospital death, most hospitalized medical patients at risk do not receive appropriate prophylaxisand then encourages hospitalist‐led action to reduce hospital‐acquired VTE. The role of the hospitalist is extracted from the competencies articulated in the Venous Thromboembolism, Quality Improvement, and Hospitalist as Teacher chapters of The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine.2

Awareness

In the Awareness area of the VTE QI RR, materials to raise clinician, hospital staff, and patient awareness are suggested and made available. Through the SHM's lead sponsorship of the national DVT Awareness Month campaign, suggested Steps to Action depict exactly how a hospital medicine service can use the campaign's materials to raise institutional support for tackling this preventable problem.

Evidence

The Evidence section aggregates a list of the most pertinent VTE prophylaxis literature to help ground any QI effort firmly in the evidence base. Through an agreement with the American College of Physicians (ACP), VTE prophylaxis articles reviewed in the ACP Journal Club are presented here.12 Although the listed literature focuses on prophylaxis, plans are in place to include references on diagnosis and treatment.

Experience

Resource room visitors interested in tapping into the experience of hospitalists and other leaders of QI efforts can navigate directly to this area. Interactive resources here include downloadable and adaptable protocols for VTE prophylaxis and, most importantly, improvement stories profiling actual QI successes. The Experience section features comments from an author of a seminal trial that studied computer alerts for high‐risk patients not receiving prophylaxis.10 The educational goal of this section of the QI RR is to provide opportunities to learn from successful QI projects, from the composition of the improvement team to the relevant metrics, implementation plan, and next steps.

Ask the Expert

The most interactive part of the resource room, the Ask the Expert forum, provides a hybrid of experience and evidence. A visitor who posts a clinical or improvement question to this discussion community receives a multidisciplinary response. For each question posted, a hospitalist moderator collects and aggregates responses from a panel of VTE experts, QI experts, hospitalist teachers, and pharmacists. The online exchange permitted by this forum promotes wider debate and learning. The questions and responses are archived and thus are available for subsequent users to read.

Improve