User login

Fleshy tumors

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

This man was given a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis, type 1 (NF-1). He had the typical features of NF-1, including neurofibromas all over his body (FIGURE 1), 8 café au lait spots (FIGURE 2), and axillary freckling.

NF-1 is relatively common: birth incidence is one in 3000 and prevalence in the general population is one in 5000. While it is typically inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, up to 50% of cases are sporadic. The diagnosis is typically made during childhood, but it may not be recognized until later in life.

For a diagnosis of NF-1, patients need to have at least 2 of the following:

- >=2 neurofibromas or >=1 plexiform neurofibromas

- >=6 café au lait spots (0.5 cm or larger before puberty, 1.5 cm or larger after puberty)

- axillary or inguinal freckling

- optic glioma

- >=2 Lisch nodules (melanotic iris hamartomas)

- dysplasia of the sphenoid bone or dysplasia/thinning of long bone cortex

- a first-degree relative with NF-1.

This patient’s skin tags were not removed. No intervention was necessary at this time other than recommending yearly visits to the ophthalmologist (to watch for the development of gliomas) and to his family physician to monitor his condition.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley, H. Neurofibromatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:982-985.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

This man was given a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis, type 1 (NF-1). He had the typical features of NF-1, including neurofibromas all over his body (FIGURE 1), 8 café au lait spots (FIGURE 2), and axillary freckling.

NF-1 is relatively common: birth incidence is one in 3000 and prevalence in the general population is one in 5000. While it is typically inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, up to 50% of cases are sporadic. The diagnosis is typically made during childhood, but it may not be recognized until later in life.

For a diagnosis of NF-1, patients need to have at least 2 of the following:

- >=2 neurofibromas or >=1 plexiform neurofibromas

- >=6 café au lait spots (0.5 cm or larger before puberty, 1.5 cm or larger after puberty)

- axillary or inguinal freckling

- optic glioma

- >=2 Lisch nodules (melanotic iris hamartomas)

- dysplasia of the sphenoid bone or dysplasia/thinning of long bone cortex

- a first-degree relative with NF-1.

This patient’s skin tags were not removed. No intervention was necessary at this time other than recommending yearly visits to the ophthalmologist (to watch for the development of gliomas) and to his family physician to monitor his condition.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley, H. Neurofibromatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:982-985.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

This man was given a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis, type 1 (NF-1). He had the typical features of NF-1, including neurofibromas all over his body (FIGURE 1), 8 café au lait spots (FIGURE 2), and axillary freckling.

NF-1 is relatively common: birth incidence is one in 3000 and prevalence in the general population is one in 5000. While it is typically inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, up to 50% of cases are sporadic. The diagnosis is typically made during childhood, but it may not be recognized until later in life.

For a diagnosis of NF-1, patients need to have at least 2 of the following:

- >=2 neurofibromas or >=1 plexiform neurofibromas

- >=6 café au lait spots (0.5 cm or larger before puberty, 1.5 cm or larger after puberty)

- axillary or inguinal freckling

- optic glioma

- >=2 Lisch nodules (melanotic iris hamartomas)

- dysplasia of the sphenoid bone or dysplasia/thinning of long bone cortex

- a first-degree relative with NF-1.

This patient’s skin tags were not removed. No intervention was necessary at this time other than recommending yearly visits to the ophthalmologist (to watch for the development of gliomas) and to his family physician to monitor his condition.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley, H. Neurofibromatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:982-985.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices by clicking this link:

Chronic pruritic vulva lesion

DURING A ROUTINE EXAM, a 45-year-old Caucasian woman complained of intense itching on her labia. She said that the itching had been an issue for more than 9 months and that she found herself scratching several times a day. She denied any vaginal discharge and said she hadn’t been sexually active in years. She had tried over-the-counter antifungals and topical Benadryl, but they provided only limited relief.

The patient had red thickened plaques with accentuated skin lines (furrows) covering both of her labia majora (FIGURE). Throughout the lesion, there were scattered areas of excoriation. Her labia minor were spared.

FIGURE

Red thickened plaques on labia majora

A speculum and bimanual exam were normal. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was present.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen simplex chronicus

This patient was given a diagnosis of lichen simplex chronicus (circumscribed neurodermatitis)—pathohistologic changes to the skin caused by habitual trauma from scratching a single area. The lesion begins as small red papules that later coalesce into a plaque with furrows (lichenification).1 The plaques become well circumscribed with attenuated skin lines. This is due to the thickening of both the epidermis (acanthosis) and stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis).2 Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation may be present—particularly in patients with naturally dark-colored skin.1

The epidemiology of lichen simplex chronicus is unknown. It tends to occur in adults between 30 and 50 years of age (although it has been seen in children) and is more common in women and people of Asian descent.3 The areas of the body that are affected are those that are easily reached, including the:4,5

- outer portion of the lower legs

- scrotum and vulva; pubic and anal areas

- wrists and ankles

- upper eyelids

- back or side of neck

- ear canal

- extensor forearms near the elbow

- fold behind the ear

- scalp

Pathology will show lichenification, acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and eczematous inflammation resembling psoriasis. The histologic separation between lichen simplex chronicus and psoriasis is particularly difficult, which leads some pathologists to report the process as “psoriasiform dermatitis.”1 That was the case in this presentation.

Differential diagnosis includes lichen planus, psoriasis

Skin conditions with a similar appearance to lichen simplex chronicus include lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, psoriasis, mycosis fungoides, and extramammary Paget’s disease.1,2,4,5

Lichen planus is an inflammatory cutaneous lesion of unknown etiology. It can be found throughout the body, including the mucous membranes. It commonly presents as the 5 Ps: pruritic, planar, polyangular, purple, and papules.5 Upon close examination, Wickham’s striae (reticular white lines) may be visible.4,5

Lichen sclerosus is a cutaneous disease of unknown origin that tends to occur in postmenopausal women; it prompts complaints of pruritus and dyspareunia.5 It presents as white atrophic plaques that may encompass both the vagina and rectum.4,5

Psoriasis lesions are usually distinctive, with red scaling papules that tend to coalesce into plaques. These lesions are associated with Auspitz sign—pinpoint bleeding following removal of silvery white scale.4,5 Lesions are often found on the elbows, groin, knees, scalp, gluteal cleft, fingernails, and toes.4

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that can have similar clinical characteristics to lichen simplex chronicus. It evolves through 4 phases: pre-MF, patch, plaque, and tumor.4 The patch phase may be confused with lichen simplex chronicus because there are flat, erythematous, and pruritic lesions. It also presents with lymphadenopathy and lesions that are persistently resistant to topical steroid treatments. High clinical suspicion and multiple biopsies at different sites may be useful.

Extramammary Paget’s disease is a rare cutaneous form of adenocarcinoma. About 12% of patients have a concurrent underlying internal malignancy.4,5 It appears as a white-to-red, scaling or macerated, infiltrated, eroded, or ulcerated plaque, most frequently observed on the labia majora and scrotum.5

2 keys to diagnosis

A history of severe pruritus (with a chronic itch-scratch cycle) combined with the findings of lichenification should make you suspect lichen simplex chronicus. It may be necessary to first treat the itch-scratch cycle before you can identify the underlying disease.1 If clinical diagnosis is still unclear, you may need to do a skin biopsy for pathologic identification and to rule out neoplasia.

Look for concomitant psychiatric disorders that often have contributing factors, such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.1,4,5 Correlation of history, physical exam, and pathophysiology is enough for the diagnosis.

Focus Tx on interrupting the itch-scratch cycle

Tell patients with lichen simplex chronicus that a permanent cure may not be possible. Intermittent therapy may be necessary for years.1 The key to long-term success is disruption of the itch-scratch cycle. Often, the scratching occurs during sleep without the patient even being aware. So it’s helpful to educate patients about the itch-scratch cycle and to advise them to keep their nails trimmed, wear gloves at nighttime, and if needed, apply an occlusive dressing.1,2 It’s also helpful to avoid irritants such as harsh soaps and washcloths, panty liners, tight clothing, perfumes, and deodorants.2

Help the patient break the nighttime itch-scratch cycle by prescribing sedating H1 antihistamines such as hydroxyzine (10-25 mg taken within 2 hours of bed time); increase the dose every 7 days until scratching ceases or adverse effects develop.2 Another option is a tricyclic antidepressant—doxepin 25 to 75 mg or amitriptyline 25 to 75 mg— taken within 2 hours of bed time.1

Recommend that patients use lubricants and petroleum-based ointments to restore the damaged skin barrier and its natural function. Using these products after bathing may be especially helpful.1

Class I and II topical steroids can be used as first-line treatment to reduce inflammation and pruritus. Be sure to advise patients of potential adverse effects of potent topical steroids, such as atrophy, discoloration, and striae.1,2,5

Second-line topical treatments include tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, pimecrolimus cream 1%, topical lidocaine 2%, and capsaicin 0.025% to 0.075% cream applied 3 times a day.2 Depending on the size and shape of the lesion, intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetate in varying concentrations may be beneficial.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to benefit patients during the day, and to address other psychological comorbidities that may be present (eg, anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder).1

Be sure to screen for secondary super-infections (bacterial and fungal) and treat accordingly. Follow-up should be scheduled for 4 weeks after treatment has begun.2

Steroids provided relief for my patient

I prescribed clobetasol 0.05% ointment without occlusion twice a day for 4 weeks. I also prescribed hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime and fluoxetine 20 mg daily for underlying depression.

At follow-up 4 weeks later, my patient reported excellent relief from her pruritus. Her labia’s erythema had greatly decreased, but chronic skin changes were still present. I advised her to apply the clobetasol every 2 weeks as needed, with follow-up in 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen Colden Cahill, DO, Assistant Clinical Professor, Michigan State University, 8300 Westpark Way, Zeeland, MI 49464; [email protected]

1. Stewart KM. Clinical care of vulvar pruritus with emphasis on one common cause, lichen simplex chronicus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:669-680.

2. Lynch PJ. Lichen simplex chronicus (atopic/neurodermatitis) of the anogenital region. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:8-19.

3. Prajapati V, Barankin B. Dermacase. Lichen simplex chronicus. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1391-1393.

4. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia Pa: Mosby; 2003.

5. Burgin S. Nummular eczema and lichen simplex chronicus/prurigo nodularis. In: Wolff K Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2008: 158–162.

DURING A ROUTINE EXAM, a 45-year-old Caucasian woman complained of intense itching on her labia. She said that the itching had been an issue for more than 9 months and that she found herself scratching several times a day. She denied any vaginal discharge and said she hadn’t been sexually active in years. She had tried over-the-counter antifungals and topical Benadryl, but they provided only limited relief.

The patient had red thickened plaques with accentuated skin lines (furrows) covering both of her labia majora (FIGURE). Throughout the lesion, there were scattered areas of excoriation. Her labia minor were spared.

FIGURE

Red thickened plaques on labia majora

A speculum and bimanual exam were normal. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was present.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen simplex chronicus

This patient was given a diagnosis of lichen simplex chronicus (circumscribed neurodermatitis)—pathohistologic changes to the skin caused by habitual trauma from scratching a single area. The lesion begins as small red papules that later coalesce into a plaque with furrows (lichenification).1 The plaques become well circumscribed with attenuated skin lines. This is due to the thickening of both the epidermis (acanthosis) and stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis).2 Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation may be present—particularly in patients with naturally dark-colored skin.1

The epidemiology of lichen simplex chronicus is unknown. It tends to occur in adults between 30 and 50 years of age (although it has been seen in children) and is more common in women and people of Asian descent.3 The areas of the body that are affected are those that are easily reached, including the:4,5

- outer portion of the lower legs

- scrotum and vulva; pubic and anal areas

- wrists and ankles

- upper eyelids

- back or side of neck

- ear canal

- extensor forearms near the elbow

- fold behind the ear

- scalp

Pathology will show lichenification, acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and eczematous inflammation resembling psoriasis. The histologic separation between lichen simplex chronicus and psoriasis is particularly difficult, which leads some pathologists to report the process as “psoriasiform dermatitis.”1 That was the case in this presentation.

Differential diagnosis includes lichen planus, psoriasis

Skin conditions with a similar appearance to lichen simplex chronicus include lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, psoriasis, mycosis fungoides, and extramammary Paget’s disease.1,2,4,5

Lichen planus is an inflammatory cutaneous lesion of unknown etiology. It can be found throughout the body, including the mucous membranes. It commonly presents as the 5 Ps: pruritic, planar, polyangular, purple, and papules.5 Upon close examination, Wickham’s striae (reticular white lines) may be visible.4,5

Lichen sclerosus is a cutaneous disease of unknown origin that tends to occur in postmenopausal women; it prompts complaints of pruritus and dyspareunia.5 It presents as white atrophic plaques that may encompass both the vagina and rectum.4,5

Psoriasis lesions are usually distinctive, with red scaling papules that tend to coalesce into plaques. These lesions are associated with Auspitz sign—pinpoint bleeding following removal of silvery white scale.4,5 Lesions are often found on the elbows, groin, knees, scalp, gluteal cleft, fingernails, and toes.4

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that can have similar clinical characteristics to lichen simplex chronicus. It evolves through 4 phases: pre-MF, patch, plaque, and tumor.4 The patch phase may be confused with lichen simplex chronicus because there are flat, erythematous, and pruritic lesions. It also presents with lymphadenopathy and lesions that are persistently resistant to topical steroid treatments. High clinical suspicion and multiple biopsies at different sites may be useful.

Extramammary Paget’s disease is a rare cutaneous form of adenocarcinoma. About 12% of patients have a concurrent underlying internal malignancy.4,5 It appears as a white-to-red, scaling or macerated, infiltrated, eroded, or ulcerated plaque, most frequently observed on the labia majora and scrotum.5

2 keys to diagnosis

A history of severe pruritus (with a chronic itch-scratch cycle) combined with the findings of lichenification should make you suspect lichen simplex chronicus. It may be necessary to first treat the itch-scratch cycle before you can identify the underlying disease.1 If clinical diagnosis is still unclear, you may need to do a skin biopsy for pathologic identification and to rule out neoplasia.

Look for concomitant psychiatric disorders that often have contributing factors, such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.1,4,5 Correlation of history, physical exam, and pathophysiology is enough for the diagnosis.

Focus Tx on interrupting the itch-scratch cycle

Tell patients with lichen simplex chronicus that a permanent cure may not be possible. Intermittent therapy may be necessary for years.1 The key to long-term success is disruption of the itch-scratch cycle. Often, the scratching occurs during sleep without the patient even being aware. So it’s helpful to educate patients about the itch-scratch cycle and to advise them to keep their nails trimmed, wear gloves at nighttime, and if needed, apply an occlusive dressing.1,2 It’s also helpful to avoid irritants such as harsh soaps and washcloths, panty liners, tight clothing, perfumes, and deodorants.2

Help the patient break the nighttime itch-scratch cycle by prescribing sedating H1 antihistamines such as hydroxyzine (10-25 mg taken within 2 hours of bed time); increase the dose every 7 days until scratching ceases or adverse effects develop.2 Another option is a tricyclic antidepressant—doxepin 25 to 75 mg or amitriptyline 25 to 75 mg— taken within 2 hours of bed time.1

Recommend that patients use lubricants and petroleum-based ointments to restore the damaged skin barrier and its natural function. Using these products after bathing may be especially helpful.1

Class I and II topical steroids can be used as first-line treatment to reduce inflammation and pruritus. Be sure to advise patients of potential adverse effects of potent topical steroids, such as atrophy, discoloration, and striae.1,2,5

Second-line topical treatments include tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, pimecrolimus cream 1%, topical lidocaine 2%, and capsaicin 0.025% to 0.075% cream applied 3 times a day.2 Depending on the size and shape of the lesion, intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetate in varying concentrations may be beneficial.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to benefit patients during the day, and to address other psychological comorbidities that may be present (eg, anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder).1

Be sure to screen for secondary super-infections (bacterial and fungal) and treat accordingly. Follow-up should be scheduled for 4 weeks after treatment has begun.2

Steroids provided relief for my patient

I prescribed clobetasol 0.05% ointment without occlusion twice a day for 4 weeks. I also prescribed hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime and fluoxetine 20 mg daily for underlying depression.

At follow-up 4 weeks later, my patient reported excellent relief from her pruritus. Her labia’s erythema had greatly decreased, but chronic skin changes were still present. I advised her to apply the clobetasol every 2 weeks as needed, with follow-up in 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen Colden Cahill, DO, Assistant Clinical Professor, Michigan State University, 8300 Westpark Way, Zeeland, MI 49464; [email protected]

DURING A ROUTINE EXAM, a 45-year-old Caucasian woman complained of intense itching on her labia. She said that the itching had been an issue for more than 9 months and that she found herself scratching several times a day. She denied any vaginal discharge and said she hadn’t been sexually active in years. She had tried over-the-counter antifungals and topical Benadryl, but they provided only limited relief.

The patient had red thickened plaques with accentuated skin lines (furrows) covering both of her labia majora (FIGURE). Throughout the lesion, there were scattered areas of excoriation. Her labia minor were spared.

FIGURE

Red thickened plaques on labia majora

A speculum and bimanual exam were normal. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was present.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen simplex chronicus

This patient was given a diagnosis of lichen simplex chronicus (circumscribed neurodermatitis)—pathohistologic changes to the skin caused by habitual trauma from scratching a single area. The lesion begins as small red papules that later coalesce into a plaque with furrows (lichenification).1 The plaques become well circumscribed with attenuated skin lines. This is due to the thickening of both the epidermis (acanthosis) and stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis).2 Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation may be present—particularly in patients with naturally dark-colored skin.1

The epidemiology of lichen simplex chronicus is unknown. It tends to occur in adults between 30 and 50 years of age (although it has been seen in children) and is more common in women and people of Asian descent.3 The areas of the body that are affected are those that are easily reached, including the:4,5

- outer portion of the lower legs

- scrotum and vulva; pubic and anal areas

- wrists and ankles

- upper eyelids

- back or side of neck

- ear canal

- extensor forearms near the elbow

- fold behind the ear

- scalp

Pathology will show lichenification, acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and eczematous inflammation resembling psoriasis. The histologic separation between lichen simplex chronicus and psoriasis is particularly difficult, which leads some pathologists to report the process as “psoriasiform dermatitis.”1 That was the case in this presentation.

Differential diagnosis includes lichen planus, psoriasis

Skin conditions with a similar appearance to lichen simplex chronicus include lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, psoriasis, mycosis fungoides, and extramammary Paget’s disease.1,2,4,5

Lichen planus is an inflammatory cutaneous lesion of unknown etiology. It can be found throughout the body, including the mucous membranes. It commonly presents as the 5 Ps: pruritic, planar, polyangular, purple, and papules.5 Upon close examination, Wickham’s striae (reticular white lines) may be visible.4,5

Lichen sclerosus is a cutaneous disease of unknown origin that tends to occur in postmenopausal women; it prompts complaints of pruritus and dyspareunia.5 It presents as white atrophic plaques that may encompass both the vagina and rectum.4,5

Psoriasis lesions are usually distinctive, with red scaling papules that tend to coalesce into plaques. These lesions are associated with Auspitz sign—pinpoint bleeding following removal of silvery white scale.4,5 Lesions are often found on the elbows, groin, knees, scalp, gluteal cleft, fingernails, and toes.4

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that can have similar clinical characteristics to lichen simplex chronicus. It evolves through 4 phases: pre-MF, patch, plaque, and tumor.4 The patch phase may be confused with lichen simplex chronicus because there are flat, erythematous, and pruritic lesions. It also presents with lymphadenopathy and lesions that are persistently resistant to topical steroid treatments. High clinical suspicion and multiple biopsies at different sites may be useful.

Extramammary Paget’s disease is a rare cutaneous form of adenocarcinoma. About 12% of patients have a concurrent underlying internal malignancy.4,5 It appears as a white-to-red, scaling or macerated, infiltrated, eroded, or ulcerated plaque, most frequently observed on the labia majora and scrotum.5

2 keys to diagnosis

A history of severe pruritus (with a chronic itch-scratch cycle) combined with the findings of lichenification should make you suspect lichen simplex chronicus. It may be necessary to first treat the itch-scratch cycle before you can identify the underlying disease.1 If clinical diagnosis is still unclear, you may need to do a skin biopsy for pathologic identification and to rule out neoplasia.

Look for concomitant psychiatric disorders that often have contributing factors, such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.1,4,5 Correlation of history, physical exam, and pathophysiology is enough for the diagnosis.

Focus Tx on interrupting the itch-scratch cycle

Tell patients with lichen simplex chronicus that a permanent cure may not be possible. Intermittent therapy may be necessary for years.1 The key to long-term success is disruption of the itch-scratch cycle. Often, the scratching occurs during sleep without the patient even being aware. So it’s helpful to educate patients about the itch-scratch cycle and to advise them to keep their nails trimmed, wear gloves at nighttime, and if needed, apply an occlusive dressing.1,2 It’s also helpful to avoid irritants such as harsh soaps and washcloths, panty liners, tight clothing, perfumes, and deodorants.2

Help the patient break the nighttime itch-scratch cycle by prescribing sedating H1 antihistamines such as hydroxyzine (10-25 mg taken within 2 hours of bed time); increase the dose every 7 days until scratching ceases or adverse effects develop.2 Another option is a tricyclic antidepressant—doxepin 25 to 75 mg or amitriptyline 25 to 75 mg— taken within 2 hours of bed time.1

Recommend that patients use lubricants and petroleum-based ointments to restore the damaged skin barrier and its natural function. Using these products after bathing may be especially helpful.1

Class I and II topical steroids can be used as first-line treatment to reduce inflammation and pruritus. Be sure to advise patients of potential adverse effects of potent topical steroids, such as atrophy, discoloration, and striae.1,2,5

Second-line topical treatments include tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, pimecrolimus cream 1%, topical lidocaine 2%, and capsaicin 0.025% to 0.075% cream applied 3 times a day.2 Depending on the size and shape of the lesion, intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetate in varying concentrations may be beneficial.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to benefit patients during the day, and to address other psychological comorbidities that may be present (eg, anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder).1

Be sure to screen for secondary super-infections (bacterial and fungal) and treat accordingly. Follow-up should be scheduled for 4 weeks after treatment has begun.2

Steroids provided relief for my patient

I prescribed clobetasol 0.05% ointment without occlusion twice a day for 4 weeks. I also prescribed hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime and fluoxetine 20 mg daily for underlying depression.

At follow-up 4 weeks later, my patient reported excellent relief from her pruritus. Her labia’s erythema had greatly decreased, but chronic skin changes were still present. I advised her to apply the clobetasol every 2 weeks as needed, with follow-up in 3 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen Colden Cahill, DO, Assistant Clinical Professor, Michigan State University, 8300 Westpark Way, Zeeland, MI 49464; [email protected]

1. Stewart KM. Clinical care of vulvar pruritus with emphasis on one common cause, lichen simplex chronicus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:669-680.

2. Lynch PJ. Lichen simplex chronicus (atopic/neurodermatitis) of the anogenital region. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:8-19.

3. Prajapati V, Barankin B. Dermacase. Lichen simplex chronicus. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1391-1393.

4. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia Pa: Mosby; 2003.

5. Burgin S. Nummular eczema and lichen simplex chronicus/prurigo nodularis. In: Wolff K Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2008: 158–162.

1. Stewart KM. Clinical care of vulvar pruritus with emphasis on one common cause, lichen simplex chronicus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:669-680.

2. Lynch PJ. Lichen simplex chronicus (atopic/neurodermatitis) of the anogenital region. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:8-19.

3. Prajapati V, Barankin B. Dermacase. Lichen simplex chronicus. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1391-1393.

4. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia Pa: Mosby; 2003.

5. Burgin S. Nummular eczema and lichen simplex chronicus/prurigo nodularis. In: Wolff K Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2008: 158–162.

Asymmetric smile

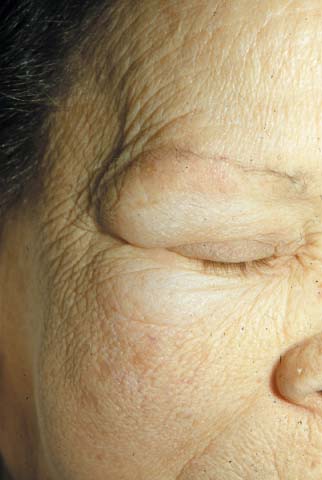

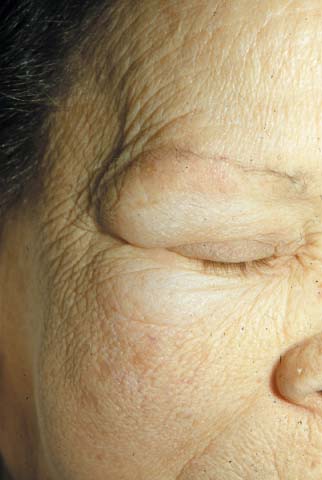

The patient was given a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy. Women who develop Bell’s palsy in pregnancy have a 5-fold increased risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.

The etiology of Bell’s palsy is unknown, but one prevailing theory suggests a viral etiology from the herpes family. The facial nerve becomes inflamed, resulting in nerve compression. Compression of the facial nerve compromises muscles of facial expression, taste fibers to the anterior tongue, pain fibers, and secretory fibers to the salivary and lacrimal glands.

This patient’s FP talked to her about treatment with steroids and antivirals. She chose not to take medications because of her pregnancy. She was told to use eye lubricants to keep her left eye moist. Though she experienced some improvement after delivery, she continued to have Bell’s palsy.

She was subsequently referred to an ear, nose, and throat surgeon who was experienced in the specialized surgical procedures needed to restore facial movement (regional muscle transfer and microvascular free tissue transfer).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Bell’s palsy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:979-981.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The patient was given a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy. Women who develop Bell’s palsy in pregnancy have a 5-fold increased risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.

The etiology of Bell’s palsy is unknown, but one prevailing theory suggests a viral etiology from the herpes family. The facial nerve becomes inflamed, resulting in nerve compression. Compression of the facial nerve compromises muscles of facial expression, taste fibers to the anterior tongue, pain fibers, and secretory fibers to the salivary and lacrimal glands.

This patient’s FP talked to her about treatment with steroids and antivirals. She chose not to take medications because of her pregnancy. She was told to use eye lubricants to keep her left eye moist. Though she experienced some improvement after delivery, she continued to have Bell’s palsy.

She was subsequently referred to an ear, nose, and throat surgeon who was experienced in the specialized surgical procedures needed to restore facial movement (regional muscle transfer and microvascular free tissue transfer).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Bell’s palsy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:979-981.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The patient was given a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy. Women who develop Bell’s palsy in pregnancy have a 5-fold increased risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.

The etiology of Bell’s palsy is unknown, but one prevailing theory suggests a viral etiology from the herpes family. The facial nerve becomes inflamed, resulting in nerve compression. Compression of the facial nerve compromises muscles of facial expression, taste fibers to the anterior tongue, pain fibers, and secretory fibers to the salivary and lacrimal glands.

This patient’s FP talked to her about treatment with steroids and antivirals. She chose not to take medications because of her pregnancy. She was told to use eye lubricants to keep her left eye moist. Though she experienced some improvement after delivery, she continued to have Bell’s palsy.

She was subsequently referred to an ear, nose, and throat surgeon who was experienced in the specialized surgical procedures needed to restore facial movement (regional muscle transfer and microvascular free tissue transfer).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Bell’s palsy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:979-981.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

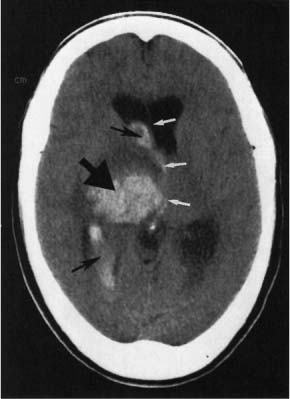

Head injury

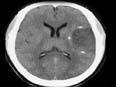

The CT scan revealed an acute subdural hematoma. The patient was hospitalized, and a neurosurgeon was consulted for surgical management.

Subdural hematomas occur at all ages. Mortality rates in treated older adults are approximately 8% for patients <65 years and 33% for patients >65 years. Most subdural hematomas are caused by trauma from a direct injury to the head or shaking injury in an infant. Motion of the brain within the skull causes a shearing force to the cortical surface and interhemispheric bridging veins. This force tears the weakest bridging veins as they cross the subdural space, resulting in an acute subdural hematoma.

Most subdural hematomas are managed surgically, and there is little evidence on conservative management. One should obtain an urgent noncontrast CT scan on any patient suspected of having a subdural hematoma. If the noncontrast CT scan is nonrevealing, obtain a contrast CT or magnetic resonance imaging scan, particularly if the traumatic event occurred 2 to 3 days earlier. Emergently refer patients with a subdural hematoma and deteriorating neurologic status or evidence of brain edema or midline shift to a hospital with neurosurgeons.

Photo courtesy of Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci, AS, et al. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Subdural hematoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:972-975.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The CT scan revealed an acute subdural hematoma. The patient was hospitalized, and a neurosurgeon was consulted for surgical management.

Subdural hematomas occur at all ages. Mortality rates in treated older adults are approximately 8% for patients <65 years and 33% for patients >65 years. Most subdural hematomas are caused by trauma from a direct injury to the head or shaking injury in an infant. Motion of the brain within the skull causes a shearing force to the cortical surface and interhemispheric bridging veins. This force tears the weakest bridging veins as they cross the subdural space, resulting in an acute subdural hematoma.

Most subdural hematomas are managed surgically, and there is little evidence on conservative management. One should obtain an urgent noncontrast CT scan on any patient suspected of having a subdural hematoma. If the noncontrast CT scan is nonrevealing, obtain a contrast CT or magnetic resonance imaging scan, particularly if the traumatic event occurred 2 to 3 days earlier. Emergently refer patients with a subdural hematoma and deteriorating neurologic status or evidence of brain edema or midline shift to a hospital with neurosurgeons.

Photo courtesy of Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci, AS, et al. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Subdural hematoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:972-975.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The CT scan revealed an acute subdural hematoma. The patient was hospitalized, and a neurosurgeon was consulted for surgical management.

Subdural hematomas occur at all ages. Mortality rates in treated older adults are approximately 8% for patients <65 years and 33% for patients >65 years. Most subdural hematomas are caused by trauma from a direct injury to the head or shaking injury in an infant. Motion of the brain within the skull causes a shearing force to the cortical surface and interhemispheric bridging veins. This force tears the weakest bridging veins as they cross the subdural space, resulting in an acute subdural hematoma.

Most subdural hematomas are managed surgically, and there is little evidence on conservative management. One should obtain an urgent noncontrast CT scan on any patient suspected of having a subdural hematoma. If the noncontrast CT scan is nonrevealing, obtain a contrast CT or magnetic resonance imaging scan, particularly if the traumatic event occurred 2 to 3 days earlier. Emergently refer patients with a subdural hematoma and deteriorating neurologic status or evidence of brain edema or midline shift to a hospital with neurosurgeons.

Photo courtesy of Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci, AS, et al. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Subdural hematoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:972-975.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

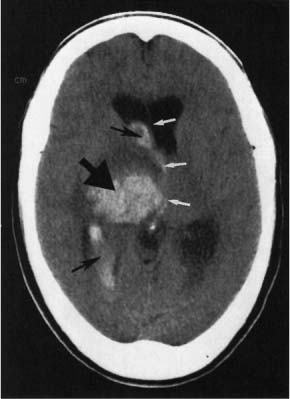

Severe headache

The CT scan showed a hemorrhagic stroke with bleeding in the right basal ganglia (large black arrow) and into the ventricles (small black arrows). (The white arrows illustrate midline shift.)

As is true for ischemic strokes, the main risk factor for hemorrhagic strokes is hypertension. In hemorrhagic strokes, it is important to not aggressively lower blood pressure. Some authorities recommend lowering blood pressure only when mean arterial pressure (MAP) is >130 mm Hg. After the hemorrhagic stroke is over, blood pressure should be treated aggressively. Modest decreases in blood pressure (12/5 mmHg) from one of many classes of hypertensive drugs lower recurrent stroke risk by 50% to 75%.

Photo courtesy of Chen MY, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Cerebral vascular accident. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:968-971.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The CT scan showed a hemorrhagic stroke with bleeding in the right basal ganglia (large black arrow) and into the ventricles (small black arrows). (The white arrows illustrate midline shift.)

As is true for ischemic strokes, the main risk factor for hemorrhagic strokes is hypertension. In hemorrhagic strokes, it is important to not aggressively lower blood pressure. Some authorities recommend lowering blood pressure only when mean arterial pressure (MAP) is >130 mm Hg. After the hemorrhagic stroke is over, blood pressure should be treated aggressively. Modest decreases in blood pressure (12/5 mmHg) from one of many classes of hypertensive drugs lower recurrent stroke risk by 50% to 75%.

Photo courtesy of Chen MY, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Cerebral vascular accident. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:968-971.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The CT scan showed a hemorrhagic stroke with bleeding in the right basal ganglia (large black arrow) and into the ventricles (small black arrows). (The white arrows illustrate midline shift.)

As is true for ischemic strokes, the main risk factor for hemorrhagic strokes is hypertension. In hemorrhagic strokes, it is important to not aggressively lower blood pressure. Some authorities recommend lowering blood pressure only when mean arterial pressure (MAP) is >130 mm Hg. After the hemorrhagic stroke is over, blood pressure should be treated aggressively. Modest decreases in blood pressure (12/5 mmHg) from one of many classes of hypertensive drugs lower recurrent stroke risk by 50% to 75%.

Photo courtesy of Chen MY, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Cerebral vascular accident. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:968-971.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

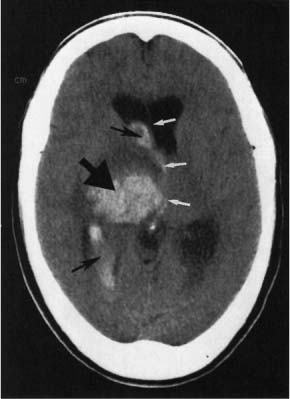

Right-sided paralysis

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The MRI (FIGURE 1) revealed an ischemic infarct in the left middle cerebral artery. Cerebral vascular accidents affect about 700,000 people every year in the United States. Ischemic (66%) and hemorrhagic (10%) strokes account for most strokes. Prevalence of stroke and mortality are higher in blacks than in whites.

The 30-day mortality rate after a first stroke is 22%. Risk factors for stroke include hypertension, cigarette smoking, type 2 diabetes, and atrial fibrillation.

A stroke response team evaluated this patient and determined that he was a candidate for tissue plasminogen activator. After the stroke, he was treated with aspirin, antihypertensives, and cholesterol-lowering medication. A noncontrast CT scan of the patient 2 weeks later is shown in FIGURE 2. He recovered 80% of his neurological deficit over the next 3 months.

Images courtesy of Chen MYM, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Cerebral vascular accident. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:968-971.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The MRI (FIGURE 1) revealed an ischemic infarct in the left middle cerebral artery. Cerebral vascular accidents affect about 700,000 people every year in the United States. Ischemic (66%) and hemorrhagic (10%) strokes account for most strokes. Prevalence of stroke and mortality are higher in blacks than in whites.

The 30-day mortality rate after a first stroke is 22%. Risk factors for stroke include hypertension, cigarette smoking, type 2 diabetes, and atrial fibrillation.

A stroke response team evaluated this patient and determined that he was a candidate for tissue plasminogen activator. After the stroke, he was treated with aspirin, antihypertensives, and cholesterol-lowering medication. A noncontrast CT scan of the patient 2 weeks later is shown in FIGURE 2. He recovered 80% of his neurological deficit over the next 3 months.

Images courtesy of Chen MYM, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Cerebral vascular accident. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:968-971.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The MRI (FIGURE 1) revealed an ischemic infarct in the left middle cerebral artery. Cerebral vascular accidents affect about 700,000 people every year in the United States. Ischemic (66%) and hemorrhagic (10%) strokes account for most strokes. Prevalence of stroke and mortality are higher in blacks than in whites.

The 30-day mortality rate after a first stroke is 22%. Risk factors for stroke include hypertension, cigarette smoking, type 2 diabetes, and atrial fibrillation.

A stroke response team evaluated this patient and determined that he was a candidate for tissue plasminogen activator. After the stroke, he was treated with aspirin, antihypertensives, and cholesterol-lowering medication. A noncontrast CT scan of the patient 2 weeks later is shown in FIGURE 2. He recovered 80% of his neurological deficit over the next 3 months.

Images courtesy of Chen MYM, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Cerebral vascular accident. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:968-971.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Painful toe ulcers

A 47-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was admitted to our hospital for intravenous antibiotic treatment of recurrent cellulitis with ulceration of her left second and third toes. Previous outpatient management with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole followed by clindamycin had failed.

The patient had been treated repeatedly over the previous 10 years for similar episodes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus cellulitis with ulceration of the same toes. These episodes began after the patient had been in multiple car accidents and had sustained lower extremity trauma.

When the patient was admitted, she was afebrile and had normal vital signs. The ulcerations on her left second and third toes (FIGURE) were painful. The distal dorsal foot was warm, erythematous, and indurated without fluctuance or crepitus. There were diffuse spider veins on the lower extremities and the peripheral pulses were 2+ symmetrically. Electrolytes, including calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase, were within normal limits, the white blood cell count was 4.9 × 103/mm3 and C-reactive protein was 1.0 mg/dL. There was an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 46 mm/h, mild transaminitis (ALT>AST), and a finding of chronic hepatitis C infection (a few months prior).

FIGURE

Ulcerated toes in a nondiabetic patient

Wound and blood cultures were negative for infection. Radiologic examination of the left foot showed no signs of osteomyelitis or other bony abnormality. We sent punch biopsies out for pathologic assessment.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Osteoma cutis

Lesional biopsies revealed that the patient had osteoma cutis, a skin condition in which bone ossification (including lamellae, trabecular bone formation, osteocytes, and sometimes marrow) occurs within the dermis.

A rare condition

Osteoma cutis has an incidence of 1.2-1.7 cases per 1000 skin lesion biopsies.1 The primary form of osteoma cutis occurs in about 25% of cases and is associated with certain genetic disorders such as Gardner’s syndrome and Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy; it arises without a preexisting lesion.1 The secondary type of osteoma cutis—which our patient had—often arises within a cancerous lesion (especially melanocytic nevi and basal cell carcinoma) or chronic inflammation (as is found in traumatic scars, acne vulgaris, chronic venous stasis, vasculitis, and other nonspecific inflammatory conditions).1-3

Sixty-eight percent of osteoma cutis cases are benign, and most patients are white females.1 Most lesions arise on the head, neck, and digits.1,4 Although foot lesions are much less common, a few cases of secondary osteoma cutis on the foot have been reported.4,5

Osteoma cutis is believed to arise via mesenchymal ossification (in contrast to endochondral bone formation from a cartilaginous precursor). Proposed mechanisms include aberrant embryological migration of mesenchymal cells into the dermis and metaplastic transformation of fibroblasts into osteoid-producing osteoblasts.4

Is it osteoma cutis or calcinosis cutis?

The differential includes calcinosis cutis, or deposition of insoluble calcium compounds in the skin without true bone formation. Lesions of both osteoma cutis and calcinosis cutis are sometimes palpable and seen on x-ray,2 but more often, plain radiographs are normal.3

Making the diagnosis requires a high suspicion for the condition—especially in patients without peripheral vascular disease or neuropathy who have nonhealing or slow-healing ulcers. A good patient history is also important to help rule out possible uncommon causes, such as cutaneous tuberculosis.6

Other diagnoses to consider for nonhealing or treatment-resistant ulcers include infection (eg, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, or underlying osteomyelitis), vasculopathy (arterial insufficiency, venous stasis, atheroembolism, or diabetes mellitus), pyoderma gangrenosum, and malnutrition.

Because the diagnosis of osteoma cutis is made primarily by pathology, suspicious lesions should be biopsied.

Conservative Tx is a good approach

Case reports suggest that bone removal speeds healing, but the benefits of surgical intervention are unclear because healing is observed in patients who receive only conservative management.2,3,5 With lesions arising on the head and neck, treatment goals are usually aesthetic. Surgical techniques of resection, curettage, or dermabrasion are most often used, and topical retinoic acid has proven to be a helpful adjuvant therapy.7

No surgery for our patient

Given our patient’s history of trauma followed by recurrent ulceration (which may not have completely resolved), we suspected that chronic inflammation was the cause of the osteoma cutis.

We prescribed minocycline 100 mg BID for 14 days for superficial wound infection, with plans to extend treatment as needed based on wound healing. She also received care at a local wound clinic for incomplete resolution of the ulceration and biopsy sites. The patient was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sally P. Weaver, MD, PhD, McLennan County Medical Education and Research Foundation, 1600 Providence Drive, Waco, TX 76707; [email protected]

1. Conlin PA, Jimenez-Quintero LP, Rapini RP. Osteomas of the skin revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:479-483.

2. Sarkany I, Kreel L. Subcutaneous ossification of the legs in chronic venous stasis. Br Med J. 1966;2:27-28.

3. Duarte IG. Multiple injuries of osteoma skin in the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:695-698.

4. Burgdorf W, Nasemann T. Cutaneous osteomas. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977;260:121-135.

5. Titchener AG, Ramoutar DN, Al-Rufaie H, et al. Osteoma cutis masquerading as an ingrowing toenail. Cases J. 2009;2:7176.-

6. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Ghosh A, et al. Non-healing perianal ulcer. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:9.-

7. Ayaviri NA, Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, et al. Isolated primary osteoma cutis of the head. Can J Plast Surg. 2006;14:33-36.

A 47-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was admitted to our hospital for intravenous antibiotic treatment of recurrent cellulitis with ulceration of her left second and third toes. Previous outpatient management with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole followed by clindamycin had failed.

The patient had been treated repeatedly over the previous 10 years for similar episodes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus cellulitis with ulceration of the same toes. These episodes began after the patient had been in multiple car accidents and had sustained lower extremity trauma.

When the patient was admitted, she was afebrile and had normal vital signs. The ulcerations on her left second and third toes (FIGURE) were painful. The distal dorsal foot was warm, erythematous, and indurated without fluctuance or crepitus. There were diffuse spider veins on the lower extremities and the peripheral pulses were 2+ symmetrically. Electrolytes, including calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase, were within normal limits, the white blood cell count was 4.9 × 103/mm3 and C-reactive protein was 1.0 mg/dL. There was an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 46 mm/h, mild transaminitis (ALT>AST), and a finding of chronic hepatitis C infection (a few months prior).

FIGURE

Ulcerated toes in a nondiabetic patient

Wound and blood cultures were negative for infection. Radiologic examination of the left foot showed no signs of osteomyelitis or other bony abnormality. We sent punch biopsies out for pathologic assessment.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Osteoma cutis

Lesional biopsies revealed that the patient had osteoma cutis, a skin condition in which bone ossification (including lamellae, trabecular bone formation, osteocytes, and sometimes marrow) occurs within the dermis.

A rare condition

Osteoma cutis has an incidence of 1.2-1.7 cases per 1000 skin lesion biopsies.1 The primary form of osteoma cutis occurs in about 25% of cases and is associated with certain genetic disorders such as Gardner’s syndrome and Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy; it arises without a preexisting lesion.1 The secondary type of osteoma cutis—which our patient had—often arises within a cancerous lesion (especially melanocytic nevi and basal cell carcinoma) or chronic inflammation (as is found in traumatic scars, acne vulgaris, chronic venous stasis, vasculitis, and other nonspecific inflammatory conditions).1-3

Sixty-eight percent of osteoma cutis cases are benign, and most patients are white females.1 Most lesions arise on the head, neck, and digits.1,4 Although foot lesions are much less common, a few cases of secondary osteoma cutis on the foot have been reported.4,5

Osteoma cutis is believed to arise via mesenchymal ossification (in contrast to endochondral bone formation from a cartilaginous precursor). Proposed mechanisms include aberrant embryological migration of mesenchymal cells into the dermis and metaplastic transformation of fibroblasts into osteoid-producing osteoblasts.4

Is it osteoma cutis or calcinosis cutis?

The differential includes calcinosis cutis, or deposition of insoluble calcium compounds in the skin without true bone formation. Lesions of both osteoma cutis and calcinosis cutis are sometimes palpable and seen on x-ray,2 but more often, plain radiographs are normal.3

Making the diagnosis requires a high suspicion for the condition—especially in patients without peripheral vascular disease or neuropathy who have nonhealing or slow-healing ulcers. A good patient history is also important to help rule out possible uncommon causes, such as cutaneous tuberculosis.6

Other diagnoses to consider for nonhealing or treatment-resistant ulcers include infection (eg, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, or underlying osteomyelitis), vasculopathy (arterial insufficiency, venous stasis, atheroembolism, or diabetes mellitus), pyoderma gangrenosum, and malnutrition.

Because the diagnosis of osteoma cutis is made primarily by pathology, suspicious lesions should be biopsied.

Conservative Tx is a good approach

Case reports suggest that bone removal speeds healing, but the benefits of surgical intervention are unclear because healing is observed in patients who receive only conservative management.2,3,5 With lesions arising on the head and neck, treatment goals are usually aesthetic. Surgical techniques of resection, curettage, or dermabrasion are most often used, and topical retinoic acid has proven to be a helpful adjuvant therapy.7

No surgery for our patient

Given our patient’s history of trauma followed by recurrent ulceration (which may not have completely resolved), we suspected that chronic inflammation was the cause of the osteoma cutis.

We prescribed minocycline 100 mg BID for 14 days for superficial wound infection, with plans to extend treatment as needed based on wound healing. She also received care at a local wound clinic for incomplete resolution of the ulceration and biopsy sites. The patient was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sally P. Weaver, MD, PhD, McLennan County Medical Education and Research Foundation, 1600 Providence Drive, Waco, TX 76707; [email protected]

A 47-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was admitted to our hospital for intravenous antibiotic treatment of recurrent cellulitis with ulceration of her left second and third toes. Previous outpatient management with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole followed by clindamycin had failed.

The patient had been treated repeatedly over the previous 10 years for similar episodes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus cellulitis with ulceration of the same toes. These episodes began after the patient had been in multiple car accidents and had sustained lower extremity trauma.

When the patient was admitted, she was afebrile and had normal vital signs. The ulcerations on her left second and third toes (FIGURE) were painful. The distal dorsal foot was warm, erythematous, and indurated without fluctuance or crepitus. There were diffuse spider veins on the lower extremities and the peripheral pulses were 2+ symmetrically. Electrolytes, including calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase, were within normal limits, the white blood cell count was 4.9 × 103/mm3 and C-reactive protein was 1.0 mg/dL. There was an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 46 mm/h, mild transaminitis (ALT>AST), and a finding of chronic hepatitis C infection (a few months prior).

FIGURE

Ulcerated toes in a nondiabetic patient

Wound and blood cultures were negative for infection. Radiologic examination of the left foot showed no signs of osteomyelitis or other bony abnormality. We sent punch biopsies out for pathologic assessment.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Osteoma cutis

Lesional biopsies revealed that the patient had osteoma cutis, a skin condition in which bone ossification (including lamellae, trabecular bone formation, osteocytes, and sometimes marrow) occurs within the dermis.

A rare condition

Osteoma cutis has an incidence of 1.2-1.7 cases per 1000 skin lesion biopsies.1 The primary form of osteoma cutis occurs in about 25% of cases and is associated with certain genetic disorders such as Gardner’s syndrome and Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy; it arises without a preexisting lesion.1 The secondary type of osteoma cutis—which our patient had—often arises within a cancerous lesion (especially melanocytic nevi and basal cell carcinoma) or chronic inflammation (as is found in traumatic scars, acne vulgaris, chronic venous stasis, vasculitis, and other nonspecific inflammatory conditions).1-3

Sixty-eight percent of osteoma cutis cases are benign, and most patients are white females.1 Most lesions arise on the head, neck, and digits.1,4 Although foot lesions are much less common, a few cases of secondary osteoma cutis on the foot have been reported.4,5

Osteoma cutis is believed to arise via mesenchymal ossification (in contrast to endochondral bone formation from a cartilaginous precursor). Proposed mechanisms include aberrant embryological migration of mesenchymal cells into the dermis and metaplastic transformation of fibroblasts into osteoid-producing osteoblasts.4

Is it osteoma cutis or calcinosis cutis?

The differential includes calcinosis cutis, or deposition of insoluble calcium compounds in the skin without true bone formation. Lesions of both osteoma cutis and calcinosis cutis are sometimes palpable and seen on x-ray,2 but more often, plain radiographs are normal.3

Making the diagnosis requires a high suspicion for the condition—especially in patients without peripheral vascular disease or neuropathy who have nonhealing or slow-healing ulcers. A good patient history is also important to help rule out possible uncommon causes, such as cutaneous tuberculosis.6

Other diagnoses to consider for nonhealing or treatment-resistant ulcers include infection (eg, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, or underlying osteomyelitis), vasculopathy (arterial insufficiency, venous stasis, atheroembolism, or diabetes mellitus), pyoderma gangrenosum, and malnutrition.

Because the diagnosis of osteoma cutis is made primarily by pathology, suspicious lesions should be biopsied.

Conservative Tx is a good approach

Case reports suggest that bone removal speeds healing, but the benefits of surgical intervention are unclear because healing is observed in patients who receive only conservative management.2,3,5 With lesions arising on the head and neck, treatment goals are usually aesthetic. Surgical techniques of resection, curettage, or dermabrasion are most often used, and topical retinoic acid has proven to be a helpful adjuvant therapy.7

No surgery for our patient

Given our patient’s history of trauma followed by recurrent ulceration (which may not have completely resolved), we suspected that chronic inflammation was the cause of the osteoma cutis.

We prescribed minocycline 100 mg BID for 14 days for superficial wound infection, with plans to extend treatment as needed based on wound healing. She also received care at a local wound clinic for incomplete resolution of the ulceration and biopsy sites. The patient was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sally P. Weaver, MD, PhD, McLennan County Medical Education and Research Foundation, 1600 Providence Drive, Waco, TX 76707; [email protected]

1. Conlin PA, Jimenez-Quintero LP, Rapini RP. Osteomas of the skin revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:479-483.

2. Sarkany I, Kreel L. Subcutaneous ossification of the legs in chronic venous stasis. Br Med J. 1966;2:27-28.

3. Duarte IG. Multiple injuries of osteoma skin in the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:695-698.

4. Burgdorf W, Nasemann T. Cutaneous osteomas. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977;260:121-135.

5. Titchener AG, Ramoutar DN, Al-Rufaie H, et al. Osteoma cutis masquerading as an ingrowing toenail. Cases J. 2009;2:7176.-

6. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Ghosh A, et al. Non-healing perianal ulcer. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:9.-

7. Ayaviri NA, Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, et al. Isolated primary osteoma cutis of the head. Can J Plast Surg. 2006;14:33-36.

1. Conlin PA, Jimenez-Quintero LP, Rapini RP. Osteomas of the skin revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:479-483.

2. Sarkany I, Kreel L. Subcutaneous ossification of the legs in chronic venous stasis. Br Med J. 1966;2:27-28.

3. Duarte IG. Multiple injuries of osteoma skin in the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:695-698.

4. Burgdorf W, Nasemann T. Cutaneous osteomas. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977;260:121-135.

5. Titchener AG, Ramoutar DN, Al-Rufaie H, et al. Osteoma cutis masquerading as an ingrowing toenail. Cases J. 2009;2:7176.-

6. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Ghosh A, et al. Non-healing perianal ulcer. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:9.-

7. Ayaviri NA, Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, et al. Isolated primary osteoma cutis of the head. Can J Plast Surg. 2006;14:33-36.

Periorbital edema

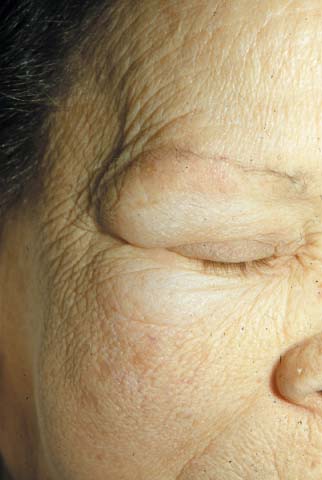

The FP recognized that the patient had hypothyroidism with symptoms of a proximal myopathy. Laboratory testing revealed a highly-elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and a very-low free thyroxine level, confirming hypothyroidism. Her creatinine kinase was also elevated, documenting a proximal myopathy secondary to hypothyroidism. The patient had classic signs of proximal myopathy (she had difficulty climbing stairs, as well as raising her arms over her head to brush her hair), She also had classic signs of hypothyroidism, including skin puffiness, dry and cool skin, hair loss, bradycardia, and a delayed relaxation phase of the deep tendon reflexes. Hypothyroidism does not require an enlarged thyroid gland or goiter as demonstrated by this case.

While the patient needed thyroid replacement, her age and a previous history of ischemic heart disease made it desirable to start levothyroxine at a low dose and titrate up carefully. The FP started the patient on 50 mcg of levothyroxine daily with a plan of increasing the dose by 25 mcg every 2 weeks.

The FP told the patient that if she experienced chest pain on her new medication, she should call the office or go to the emergency department immediately.

The patient responded well to the levothyroxine and didn’t have any cardiac complications from treatment. The patient was followed every 2 weeks with adjustments to her levothyroxine dosing based on symptoms, physical exam, and TSH measurements.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Goiter and hypothyroidism. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:954-958.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The FP recognized that the patient had hypothyroidism with symptoms of a proximal myopathy. Laboratory testing revealed a highly-elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and a very-low free thyroxine level, confirming hypothyroidism. Her creatinine kinase was also elevated, documenting a proximal myopathy secondary to hypothyroidism. The patient had classic signs of proximal myopathy (she had difficulty climbing stairs, as well as raising her arms over her head to brush her hair), She also had classic signs of hypothyroidism, including skin puffiness, dry and cool skin, hair loss, bradycardia, and a delayed relaxation phase of the deep tendon reflexes. Hypothyroidism does not require an enlarged thyroid gland or goiter as demonstrated by this case.

While the patient needed thyroid replacement, her age and a previous history of ischemic heart disease made it desirable to start levothyroxine at a low dose and titrate up carefully. The FP started the patient on 50 mcg of levothyroxine daily with a plan of increasing the dose by 25 mcg every 2 weeks.

The FP told the patient that if she experienced chest pain on her new medication, she should call the office or go to the emergency department immediately.

The patient responded well to the levothyroxine and didn’t have any cardiac complications from treatment. The patient was followed every 2 weeks with adjustments to her levothyroxine dosing based on symptoms, physical exam, and TSH measurements.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Goiter and hypothyroidism. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:954-958.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The FP recognized that the patient had hypothyroidism with symptoms of a proximal myopathy. Laboratory testing revealed a highly-elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and a very-low free thyroxine level, confirming hypothyroidism. Her creatinine kinase was also elevated, documenting a proximal myopathy secondary to hypothyroidism. The patient had classic signs of proximal myopathy (she had difficulty climbing stairs, as well as raising her arms over her head to brush her hair), She also had classic signs of hypothyroidism, including skin puffiness, dry and cool skin, hair loss, bradycardia, and a delayed relaxation phase of the deep tendon reflexes. Hypothyroidism does not require an enlarged thyroid gland or goiter as demonstrated by this case.

While the patient needed thyroid replacement, her age and a previous history of ischemic heart disease made it desirable to start levothyroxine at a low dose and titrate up carefully. The FP started the patient on 50 mcg of levothyroxine daily with a plan of increasing the dose by 25 mcg every 2 weeks.

The FP told the patient that if she experienced chest pain on her new medication, she should call the office or go to the emergency department immediately.

The patient responded well to the levothyroxine and didn’t have any cardiac complications from treatment. The patient was followed every 2 weeks with adjustments to her levothyroxine dosing based on symptoms, physical exam, and TSH measurements.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Goiter and hypothyroidism. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:954-958.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

Enlarged neck

The FP recognized this as a large goiter with symptoms of hypothyroidism. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level and a low free thyroxine level, confirming hypothyroidism.

Most goiters are not associated with thyroid dysfunction. The prevalence of goitrous hypothyroidism varies from 0.7% to 4% of the population.

Patients with endemic goiter should be given iodine. Large goiters that impinge upon the trachea or that don’t respond to medications may be treated with surgery.

Patients with goiter and hypothyroidism are treated with levothyroxine as follows:

- Younger patients start with 50 to 100 µg/d increasing by 25 to 50 µg/d at 6-week intervals until the TSH is normal (approximately 1.6 µg/kg/d of levothyroxine).

- Older patients, or those with cardiac disease, start with 25 µg/d and advance slowly to normalize the TSH (approximately 1 µg/kg/d of levothyroxine).

In this case, the FP started the patient on levothyroxine 100 µg/d and recommended that her TSH level be tested again in 6 weeks.

Photo courtesy of Dan Stulberg, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Goiter and hypothyroidism. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:954-958.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The FP recognized this as a large goiter with symptoms of hypothyroidism. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level and a low free thyroxine level, confirming hypothyroidism.

Most goiters are not associated with thyroid dysfunction. The prevalence of goitrous hypothyroidism varies from 0.7% to 4% of the population.

Patients with endemic goiter should be given iodine. Large goiters that impinge upon the trachea or that don’t respond to medications may be treated with surgery.

Patients with goiter and hypothyroidism are treated with levothyroxine as follows:

- Younger patients start with 50 to 100 µg/d increasing by 25 to 50 µg/d at 6-week intervals until the TSH is normal (approximately 1.6 µg/kg/d of levothyroxine).

- Older patients, or those with cardiac disease, start with 25 µg/d and advance slowly to normalize the TSH (approximately 1 µg/kg/d of levothyroxine).

In this case, the FP started the patient on levothyroxine 100 µg/d and recommended that her TSH level be tested again in 6 weeks.

Photo courtesy of Dan Stulberg, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Goiter and hypothyroidism. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:954-958.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link:

The FP recognized this as a large goiter with symptoms of hypothyroidism. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level and a low free thyroxine level, confirming hypothyroidism.

Most goiters are not associated with thyroid dysfunction. The prevalence of goitrous hypothyroidism varies from 0.7% to 4% of the population.

Patients with endemic goiter should be given iodine. Large goiters that impinge upon the trachea or that don’t respond to medications may be treated with surgery.

Patients with goiter and hypothyroidism are treated with levothyroxine as follows:

- Younger patients start with 50 to 100 µg/d increasing by 25 to 50 µg/d at 6-week intervals until the TSH is normal (approximately 1.6 µg/kg/d of levothyroxine).

- Older patients, or those with cardiac disease, start with 25 µg/d and advance slowly to normalize the TSH (approximately 1 µg/kg/d of levothyroxine).

In this case, the FP started the patient on levothyroxine 100 µg/d and recommended that her TSH level be tested again in 6 weeks.

Photo courtesy of Dan Stulberg, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Goiter and hypothyroidism. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:954-958.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: