User login

Your patient refuses a suicide risk assessment. Now what?

On occasion, a patient may refuse to cooperate with a suicide risk assessment or is unable to participate due to the severity of a psychiatric or medical condition. In such situations, how can we conduct an assessment that meets our ethical, professional, and legal obligations?

First, skipping a suicide risk assessment is never an option. A patient’s refusal or inability to cooperate does not release us from our duty of care. We are obligated to gather information about suicide risk to anticipate the likelihood and severity of harm.1 Furthermore, collecting information helps us evaluate what types of precautions are necessary to reduce or eliminate suicide risk.

Some clinicians may believe that a suicide risk assessment is only possible when they can ask patients about ideation, intent, plans, and past suicidal behavior. While the patient’s self-report is valuable, it is only one data point, and in some cases, it may not be reliable or credible.2 So how should you handle such situations? Here I describe 3 steps to take to estimate a patient’s suicide risk without their participation.

1. Obtain information from other sources.

These can include:

- your recent contacts with the patient

- the patient’s responses to previous inquiries about suicidality

- collateral reports from staff

- the patient’s chart and past medical records

- past suicide attempts (including the precipitants, the patient’s reasons for the attempt, details of the actions taken and methods used, any medical outcome, and the patient’s reaction to surviving)3

- past nonsuicidal self-injury

- past episodes of suicidal thinking

- treatment progress to date

- mental status.

Documenting your sources of information will indicate that you made reasonable efforts to appreciate the risk despite imperfect circumstances. Furthermore, these sources of data can support your work to assess the severity of the patient’s current suicidality, to clinically formulate why the patient is susceptible to suicidal thoughts and behavior, and to anticipate circumstances that could constitute a high-risk period for your patient to attempt suicide.

2. Document the reasons you were unable to interview the patient. For patients who are competent to refuse services, document the efforts you made to gain the patient’s cooperation. If the patient’s psychiatric condition (eg, florid psychosis) was the main impediment, note this.

3. Explain the limitations of your assessment. This might include acknowledging that your estimation of the patient’s suicide risk is missing important information but is the best possible estimate at the time. Explain how you determined the level of risk with a statement such as, “Because the patient was unable to participate, I estimated risk based on….” If the patient’s lack of participation lowers your confidence in your risk estimate, this also should be documented. Reduced confidence may indicate the need for additional steps to assure the patient’s safety (eg, admission, delaying discharge, initiating continuous observation).

1. Obegi JH. Probable standards of care for suicide risk assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(4):452-459.

2. Hom MA, Stanley IH, Duffy ME, et al. Investigating the reliability of suicide attempt history reporting across five measures: a study of US military service members at risk of suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1332-1349.

3. Rudd MD. Core competencies, warning signs, and a framework for suicide risk assessment in clinical practice. In: Nock MK, ed. The Oxford handbook of suicide and self-injury. Oxford University Press; 2014:323-336.

On occasion, a patient may refuse to cooperate with a suicide risk assessment or is unable to participate due to the severity of a psychiatric or medical condition. In such situations, how can we conduct an assessment that meets our ethical, professional, and legal obligations?

First, skipping a suicide risk assessment is never an option. A patient’s refusal or inability to cooperate does not release us from our duty of care. We are obligated to gather information about suicide risk to anticipate the likelihood and severity of harm.1 Furthermore, collecting information helps us evaluate what types of precautions are necessary to reduce or eliminate suicide risk.

Some clinicians may believe that a suicide risk assessment is only possible when they can ask patients about ideation, intent, plans, and past suicidal behavior. While the patient’s self-report is valuable, it is only one data point, and in some cases, it may not be reliable or credible.2 So how should you handle such situations? Here I describe 3 steps to take to estimate a patient’s suicide risk without their participation.

1. Obtain information from other sources.

These can include:

- your recent contacts with the patient

- the patient’s responses to previous inquiries about suicidality

- collateral reports from staff

- the patient’s chart and past medical records

- past suicide attempts (including the precipitants, the patient’s reasons for the attempt, details of the actions taken and methods used, any medical outcome, and the patient’s reaction to surviving)3

- past nonsuicidal self-injury

- past episodes of suicidal thinking

- treatment progress to date

- mental status.

Documenting your sources of information will indicate that you made reasonable efforts to appreciate the risk despite imperfect circumstances. Furthermore, these sources of data can support your work to assess the severity of the patient’s current suicidality, to clinically formulate why the patient is susceptible to suicidal thoughts and behavior, and to anticipate circumstances that could constitute a high-risk period for your patient to attempt suicide.

2. Document the reasons you were unable to interview the patient. For patients who are competent to refuse services, document the efforts you made to gain the patient’s cooperation. If the patient’s psychiatric condition (eg, florid psychosis) was the main impediment, note this.

3. Explain the limitations of your assessment. This might include acknowledging that your estimation of the patient’s suicide risk is missing important information but is the best possible estimate at the time. Explain how you determined the level of risk with a statement such as, “Because the patient was unable to participate, I estimated risk based on….” If the patient’s lack of participation lowers your confidence in your risk estimate, this also should be documented. Reduced confidence may indicate the need for additional steps to assure the patient’s safety (eg, admission, delaying discharge, initiating continuous observation).

On occasion, a patient may refuse to cooperate with a suicide risk assessment or is unable to participate due to the severity of a psychiatric or medical condition. In such situations, how can we conduct an assessment that meets our ethical, professional, and legal obligations?

First, skipping a suicide risk assessment is never an option. A patient’s refusal or inability to cooperate does not release us from our duty of care. We are obligated to gather information about suicide risk to anticipate the likelihood and severity of harm.1 Furthermore, collecting information helps us evaluate what types of precautions are necessary to reduce or eliminate suicide risk.

Some clinicians may believe that a suicide risk assessment is only possible when they can ask patients about ideation, intent, plans, and past suicidal behavior. While the patient’s self-report is valuable, it is only one data point, and in some cases, it may not be reliable or credible.2 So how should you handle such situations? Here I describe 3 steps to take to estimate a patient’s suicide risk without their participation.

1. Obtain information from other sources.

These can include:

- your recent contacts with the patient

- the patient’s responses to previous inquiries about suicidality

- collateral reports from staff

- the patient’s chart and past medical records

- past suicide attempts (including the precipitants, the patient’s reasons for the attempt, details of the actions taken and methods used, any medical outcome, and the patient’s reaction to surviving)3

- past nonsuicidal self-injury

- past episodes of suicidal thinking

- treatment progress to date

- mental status.

Documenting your sources of information will indicate that you made reasonable efforts to appreciate the risk despite imperfect circumstances. Furthermore, these sources of data can support your work to assess the severity of the patient’s current suicidality, to clinically formulate why the patient is susceptible to suicidal thoughts and behavior, and to anticipate circumstances that could constitute a high-risk period for your patient to attempt suicide.

2. Document the reasons you were unable to interview the patient. For patients who are competent to refuse services, document the efforts you made to gain the patient’s cooperation. If the patient’s psychiatric condition (eg, florid psychosis) was the main impediment, note this.

3. Explain the limitations of your assessment. This might include acknowledging that your estimation of the patient’s suicide risk is missing important information but is the best possible estimate at the time. Explain how you determined the level of risk with a statement such as, “Because the patient was unable to participate, I estimated risk based on….” If the patient’s lack of participation lowers your confidence in your risk estimate, this also should be documented. Reduced confidence may indicate the need for additional steps to assure the patient’s safety (eg, admission, delaying discharge, initiating continuous observation).

1. Obegi JH. Probable standards of care for suicide risk assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(4):452-459.

2. Hom MA, Stanley IH, Duffy ME, et al. Investigating the reliability of suicide attempt history reporting across five measures: a study of US military service members at risk of suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1332-1349.

3. Rudd MD. Core competencies, warning signs, and a framework for suicide risk assessment in clinical practice. In: Nock MK, ed. The Oxford handbook of suicide and self-injury. Oxford University Press; 2014:323-336.

1. Obegi JH. Probable standards of care for suicide risk assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(4):452-459.

2. Hom MA, Stanley IH, Duffy ME, et al. Investigating the reliability of suicide attempt history reporting across five measures: a study of US military service members at risk of suicide. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(7):1332-1349.

3. Rudd MD. Core competencies, warning signs, and a framework for suicide risk assessment in clinical practice. In: Nock MK, ed. The Oxford handbook of suicide and self-injury. Oxford University Press; 2014:323-336.

Metadata, malpractice claims, and making changes to the EHR

In 2009, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act), which is part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, provided several billion dollars of grants and incentives to stimulate the implementation of electronic health records (EHRs) and supporting technology in the United States.1 Since then, almost all health care organizations have employed EHRs and supporting technologies. Unfortunately, this has created new liability risks. One potential risk is that in malpractice claims, there is more discoverable evidence, including metadata, with which to prove the claims.2 In this article, I explain what metadata is and how it can be used in medical malpractice cases. In addition, because we cannot change metadata, I provide guidance on making corrections in your EHR do

What is metadata?

Metadata—commonly described as data about data—lurk behind the words and images we can see on our computer screens. Metadata can be conceptualized as data that provides details about the information we enter into a computer system, creating a permanent electronic footprint that can be used to track our activity.2,3 Examples of metadata include (but are not limited to) the user’s name, date and time of a record entry, changes or deletions made to the record, the date an entry was created or modified, annotations that the user added over a period of time, and any other data that the software captures without the user manually entering the information.3 Metadata is typically stored on a server or file that users cannot access, which ensures data integrity because a user cannot alter a patient’s medical record without those changes being captured.3

How metadata is used in malpractice claims

When a psychiatrist is sued for medical negligence, the integrity of the EHR is an important aspect of defending against the lawsuit. A plaintiff’s (patient’s) attorney can more readily discover changes to the patient’s medical record by requesting the metadata and having it analyzed by an information technology specialist. Because the computer system captures everything a user does, it is difficult to alter a patient’s record without being detected. Consequently, plaintiff attorneys frequently request metadata during discovery in the hopes of learning whether the defendant psychiatrist altered or attempted to hide information that was contained or missing from the original version of the medical record.3 If the medical record was revised at a time unrelated to the treatment, metadata can raise suspicion of deception, even in the absence of wrongdoing.2 Alternatively, metadata can be used to validate that the EHR was changed when treatment occurred, which can bolster a defendant psychiatrist’s ability to rely on the EHR against a claim of medical negligence.2

Depending on the jurisdiction, metadata may or may not be discoverable. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure emphasize producing documents in their original format.4 For federal cases, these rules suggest that the parties discuss discovery of this material when they are initially conferring; however, the rules do not specify whether a party must produce metadata, which leaves the courts to refine these rules through case law.4,5 In one case, a federal court ruled that a party had to produce documents with metadata intact.5 Without an agreement between both parties to exclude metadata from produced documents, the parties must produce the metadata.5 State laws differ in regards to the discoverability of metadata.

Corrections vs alterations

A patient’s medical record is the best evidence of the care we provided, should that care ever be challenged in court. We can preserve the medical record’s effectiveness through appropriate changes to it. Appropriately executed corrections are a normal part of documentation, whereas alterations to the medical record can cast doubt on our credibility and lead an otherwise defensible case to require a settlement.6

Corrections are changes to a patient’s medical record during the normal course of treatment.6 These are acceptable, provided the changes are made appropriately. Health care facilities and practices have their own policies for making appropriate corrections and addendums to the medical record. Once a correction and/or addendum is made, do not remove or delete the erroneous entry, because health care colleagues may have relied on it, and deleting an erroneous entry also would alter the integrity of the medical record.6 When done appropriately, corrections will not be misconstrued as alterations.

Alterations are changes to a patient’s medical record after a psychiatrist receives notice of a lawsuit and “clarifies” certain points in the medical record to aid the defense against the claim.6 Alterations are considered deliberate misrepresentations of facts and, if discovered during litigation, can significantly impact the ability to defend against a claim.6 In addition, many medical liability policies exclude coverage for claims in which the medical record was altered, which might result in a psychiatrist having to pay for the judgment and defense costs out of pocket.6 Psychiatrists facing litigation who have a legitimate need to change an EHR entry after a claim is filed should consult with legal counsel or a risk management professional for guidance before making any changes.3 If they concur with updating the patient’s record to correct an error (including an addendum or a late entry; see below), the original entry, date, and time stamp must be accessible.3 This should also include the current date/time of the amended entry, the name of the person making the change, and the reasons for the change.3

Continue to: How to handle corrections and late entries

How to handle corrections and late entries

Sometimes situations occur that require us to make late entries, enter addendums, or add clarification notes to patient information in the EHRs. Regardless of your work environment (ie, hospital, your own practice), there should be clear procedures in place for correcting patients’ EHRs that are in accordance with applicable federal and state laws. Correcting an error in the EHR should follow the same basic principles of correcting paper records: do not obscure the original entry, make timely corrections, sign all entries, ensure the person making the change is identified, and document the reason(s) for the correction.7 The EHR must be able to track corrections or changes to an entry once they are entered or authenticated. Any physical copies of documentation must also have the same corrections or changes if they have been previously printed from the EHR.

You may need to make an entry that is late (out of sequence) or provides additional documentation to supplement previously written entries.7 A late entry should be used to record information when a pertinent entry was missed or not written in a timely manner.7 Label the new entry as a “late entry,” enter the current date and time (do not give the appearance that the entry was made on a previous date or at an earlier time), and identify or refer to the date and incident for which the late entry is written.7 If the late entry is used to document an omission, validate the source of additional information as best you can (ie, details of where you obtained the information to write the late entry).7 Make late entries as soon as possible after the original entry; although there is no time limit on writing a late entry, delays in corrections might diminish the credibility of the changes.

Addendums are used to provide additional information in conjunction with a previous entry.7 They also provide additional information to address a specific situation or incident referenced in a previous note. Addendums should not be used to document information that was forgotten or written in error.7 A clarification note is used to avoid incorrect interpretation of previously documented information.7 When writing an addendum or a clarification note, you should label it as an “addendum” or a “clarification note”; document the current date and time; state the reason for the addendum (referring back to the original entry) or clarification note (referring back to the entry being clarified); and identify any sources of information used to support an addendum or a clarification note.7

1. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Pub L No. 111-5, 123 Stat 115 (2009).

2. Paterick ZR, Patel NJ, Ngo E, et al. Medical liability in the electronic medical records era. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31(4):558-561.

3. Funicelli A. ‘Hidden’ information in your EHRs could increase your liability risk. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(18):12-13.

4. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 26(f), 115th Cong, 1st Sess (2017).

5. Williams v Sprint/United Mgmt Co, 230 FRD 640 (D Kan 2005).

6. Ryan ML. Making changes to a medical record: corrections vs. alterations. NORCAL Mutual Insurance Company. Accessed February 3, 2021. http://www.sccma.org/Portals/19/Making%20Changes%20to%20a%20Medical%20Record.pdf

7. AHIMA’s long-term care health information practice and documentation guidelines. The American Health Information Management Association. Published 2014. Accessed February 3, 2021. http://bok.ahima.org/Pages/Long%20Term%20Care%20Guidelines%20TOC/Legal%20Documentation%20Standards/Legal%20Guidelines

In 2009, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act), which is part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, provided several billion dollars of grants and incentives to stimulate the implementation of electronic health records (EHRs) and supporting technology in the United States.1 Since then, almost all health care organizations have employed EHRs and supporting technologies. Unfortunately, this has created new liability risks. One potential risk is that in malpractice claims, there is more discoverable evidence, including metadata, with which to prove the claims.2 In this article, I explain what metadata is and how it can be used in medical malpractice cases. In addition, because we cannot change metadata, I provide guidance on making corrections in your EHR do

What is metadata?

Metadata—commonly described as data about data—lurk behind the words and images we can see on our computer screens. Metadata can be conceptualized as data that provides details about the information we enter into a computer system, creating a permanent electronic footprint that can be used to track our activity.2,3 Examples of metadata include (but are not limited to) the user’s name, date and time of a record entry, changes or deletions made to the record, the date an entry was created or modified, annotations that the user added over a period of time, and any other data that the software captures without the user manually entering the information.3 Metadata is typically stored on a server or file that users cannot access, which ensures data integrity because a user cannot alter a patient’s medical record without those changes being captured.3

How metadata is used in malpractice claims

When a psychiatrist is sued for medical negligence, the integrity of the EHR is an important aspect of defending against the lawsuit. A plaintiff’s (patient’s) attorney can more readily discover changes to the patient’s medical record by requesting the metadata and having it analyzed by an information technology specialist. Because the computer system captures everything a user does, it is difficult to alter a patient’s record without being detected. Consequently, plaintiff attorneys frequently request metadata during discovery in the hopes of learning whether the defendant psychiatrist altered or attempted to hide information that was contained or missing from the original version of the medical record.3 If the medical record was revised at a time unrelated to the treatment, metadata can raise suspicion of deception, even in the absence of wrongdoing.2 Alternatively, metadata can be used to validate that the EHR was changed when treatment occurred, which can bolster a defendant psychiatrist’s ability to rely on the EHR against a claim of medical negligence.2

Depending on the jurisdiction, metadata may or may not be discoverable. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure emphasize producing documents in their original format.4 For federal cases, these rules suggest that the parties discuss discovery of this material when they are initially conferring; however, the rules do not specify whether a party must produce metadata, which leaves the courts to refine these rules through case law.4,5 In one case, a federal court ruled that a party had to produce documents with metadata intact.5 Without an agreement between both parties to exclude metadata from produced documents, the parties must produce the metadata.5 State laws differ in regards to the discoverability of metadata.

Corrections vs alterations

A patient’s medical record is the best evidence of the care we provided, should that care ever be challenged in court. We can preserve the medical record’s effectiveness through appropriate changes to it. Appropriately executed corrections are a normal part of documentation, whereas alterations to the medical record can cast doubt on our credibility and lead an otherwise defensible case to require a settlement.6

Corrections are changes to a patient’s medical record during the normal course of treatment.6 These are acceptable, provided the changes are made appropriately. Health care facilities and practices have their own policies for making appropriate corrections and addendums to the medical record. Once a correction and/or addendum is made, do not remove or delete the erroneous entry, because health care colleagues may have relied on it, and deleting an erroneous entry also would alter the integrity of the medical record.6 When done appropriately, corrections will not be misconstrued as alterations.

Alterations are changes to a patient’s medical record after a psychiatrist receives notice of a lawsuit and “clarifies” certain points in the medical record to aid the defense against the claim.6 Alterations are considered deliberate misrepresentations of facts and, if discovered during litigation, can significantly impact the ability to defend against a claim.6 In addition, many medical liability policies exclude coverage for claims in which the medical record was altered, which might result in a psychiatrist having to pay for the judgment and defense costs out of pocket.6 Psychiatrists facing litigation who have a legitimate need to change an EHR entry after a claim is filed should consult with legal counsel or a risk management professional for guidance before making any changes.3 If they concur with updating the patient’s record to correct an error (including an addendum or a late entry; see below), the original entry, date, and time stamp must be accessible.3 This should also include the current date/time of the amended entry, the name of the person making the change, and the reasons for the change.3

Continue to: How to handle corrections and late entries

How to handle corrections and late entries

Sometimes situations occur that require us to make late entries, enter addendums, or add clarification notes to patient information in the EHRs. Regardless of your work environment (ie, hospital, your own practice), there should be clear procedures in place for correcting patients’ EHRs that are in accordance with applicable federal and state laws. Correcting an error in the EHR should follow the same basic principles of correcting paper records: do not obscure the original entry, make timely corrections, sign all entries, ensure the person making the change is identified, and document the reason(s) for the correction.7 The EHR must be able to track corrections or changes to an entry once they are entered or authenticated. Any physical copies of documentation must also have the same corrections or changes if they have been previously printed from the EHR.

You may need to make an entry that is late (out of sequence) or provides additional documentation to supplement previously written entries.7 A late entry should be used to record information when a pertinent entry was missed or not written in a timely manner.7 Label the new entry as a “late entry,” enter the current date and time (do not give the appearance that the entry was made on a previous date or at an earlier time), and identify or refer to the date and incident for which the late entry is written.7 If the late entry is used to document an omission, validate the source of additional information as best you can (ie, details of where you obtained the information to write the late entry).7 Make late entries as soon as possible after the original entry; although there is no time limit on writing a late entry, delays in corrections might diminish the credibility of the changes.

Addendums are used to provide additional information in conjunction with a previous entry.7 They also provide additional information to address a specific situation or incident referenced in a previous note. Addendums should not be used to document information that was forgotten or written in error.7 A clarification note is used to avoid incorrect interpretation of previously documented information.7 When writing an addendum or a clarification note, you should label it as an “addendum” or a “clarification note”; document the current date and time; state the reason for the addendum (referring back to the original entry) or clarification note (referring back to the entry being clarified); and identify any sources of information used to support an addendum or a clarification note.7

In 2009, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act), which is part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, provided several billion dollars of grants and incentives to stimulate the implementation of electronic health records (EHRs) and supporting technology in the United States.1 Since then, almost all health care organizations have employed EHRs and supporting technologies. Unfortunately, this has created new liability risks. One potential risk is that in malpractice claims, there is more discoverable evidence, including metadata, with which to prove the claims.2 In this article, I explain what metadata is and how it can be used in medical malpractice cases. In addition, because we cannot change metadata, I provide guidance on making corrections in your EHR do

What is metadata?

Metadata—commonly described as data about data—lurk behind the words and images we can see on our computer screens. Metadata can be conceptualized as data that provides details about the information we enter into a computer system, creating a permanent electronic footprint that can be used to track our activity.2,3 Examples of metadata include (but are not limited to) the user’s name, date and time of a record entry, changes or deletions made to the record, the date an entry was created or modified, annotations that the user added over a period of time, and any other data that the software captures without the user manually entering the information.3 Metadata is typically stored on a server or file that users cannot access, which ensures data integrity because a user cannot alter a patient’s medical record without those changes being captured.3

How metadata is used in malpractice claims

When a psychiatrist is sued for medical negligence, the integrity of the EHR is an important aspect of defending against the lawsuit. A plaintiff’s (patient’s) attorney can more readily discover changes to the patient’s medical record by requesting the metadata and having it analyzed by an information technology specialist. Because the computer system captures everything a user does, it is difficult to alter a patient’s record without being detected. Consequently, plaintiff attorneys frequently request metadata during discovery in the hopes of learning whether the defendant psychiatrist altered or attempted to hide information that was contained or missing from the original version of the medical record.3 If the medical record was revised at a time unrelated to the treatment, metadata can raise suspicion of deception, even in the absence of wrongdoing.2 Alternatively, metadata can be used to validate that the EHR was changed when treatment occurred, which can bolster a defendant psychiatrist’s ability to rely on the EHR against a claim of medical negligence.2

Depending on the jurisdiction, metadata may or may not be discoverable. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure emphasize producing documents in their original format.4 For federal cases, these rules suggest that the parties discuss discovery of this material when they are initially conferring; however, the rules do not specify whether a party must produce metadata, which leaves the courts to refine these rules through case law.4,5 In one case, a federal court ruled that a party had to produce documents with metadata intact.5 Without an agreement between both parties to exclude metadata from produced documents, the parties must produce the metadata.5 State laws differ in regards to the discoverability of metadata.

Corrections vs alterations

A patient’s medical record is the best evidence of the care we provided, should that care ever be challenged in court. We can preserve the medical record’s effectiveness through appropriate changes to it. Appropriately executed corrections are a normal part of documentation, whereas alterations to the medical record can cast doubt on our credibility and lead an otherwise defensible case to require a settlement.6

Corrections are changes to a patient’s medical record during the normal course of treatment.6 These are acceptable, provided the changes are made appropriately. Health care facilities and practices have their own policies for making appropriate corrections and addendums to the medical record. Once a correction and/or addendum is made, do not remove or delete the erroneous entry, because health care colleagues may have relied on it, and deleting an erroneous entry also would alter the integrity of the medical record.6 When done appropriately, corrections will not be misconstrued as alterations.

Alterations are changes to a patient’s medical record after a psychiatrist receives notice of a lawsuit and “clarifies” certain points in the medical record to aid the defense against the claim.6 Alterations are considered deliberate misrepresentations of facts and, if discovered during litigation, can significantly impact the ability to defend against a claim.6 In addition, many medical liability policies exclude coverage for claims in which the medical record was altered, which might result in a psychiatrist having to pay for the judgment and defense costs out of pocket.6 Psychiatrists facing litigation who have a legitimate need to change an EHR entry after a claim is filed should consult with legal counsel or a risk management professional for guidance before making any changes.3 If they concur with updating the patient’s record to correct an error (including an addendum or a late entry; see below), the original entry, date, and time stamp must be accessible.3 This should also include the current date/time of the amended entry, the name of the person making the change, and the reasons for the change.3

Continue to: How to handle corrections and late entries

How to handle corrections and late entries

Sometimes situations occur that require us to make late entries, enter addendums, or add clarification notes to patient information in the EHRs. Regardless of your work environment (ie, hospital, your own practice), there should be clear procedures in place for correcting patients’ EHRs that are in accordance with applicable federal and state laws. Correcting an error in the EHR should follow the same basic principles of correcting paper records: do not obscure the original entry, make timely corrections, sign all entries, ensure the person making the change is identified, and document the reason(s) for the correction.7 The EHR must be able to track corrections or changes to an entry once they are entered or authenticated. Any physical copies of documentation must also have the same corrections or changes if they have been previously printed from the EHR.

You may need to make an entry that is late (out of sequence) or provides additional documentation to supplement previously written entries.7 A late entry should be used to record information when a pertinent entry was missed or not written in a timely manner.7 Label the new entry as a “late entry,” enter the current date and time (do not give the appearance that the entry was made on a previous date or at an earlier time), and identify or refer to the date and incident for which the late entry is written.7 If the late entry is used to document an omission, validate the source of additional information as best you can (ie, details of where you obtained the information to write the late entry).7 Make late entries as soon as possible after the original entry; although there is no time limit on writing a late entry, delays in corrections might diminish the credibility of the changes.

Addendums are used to provide additional information in conjunction with a previous entry.7 They also provide additional information to address a specific situation or incident referenced in a previous note. Addendums should not be used to document information that was forgotten or written in error.7 A clarification note is used to avoid incorrect interpretation of previously documented information.7 When writing an addendum or a clarification note, you should label it as an “addendum” or a “clarification note”; document the current date and time; state the reason for the addendum (referring back to the original entry) or clarification note (referring back to the entry being clarified); and identify any sources of information used to support an addendum or a clarification note.7

1. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Pub L No. 111-5, 123 Stat 115 (2009).

2. Paterick ZR, Patel NJ, Ngo E, et al. Medical liability in the electronic medical records era. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31(4):558-561.

3. Funicelli A. ‘Hidden’ information in your EHRs could increase your liability risk. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(18):12-13.

4. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 26(f), 115th Cong, 1st Sess (2017).

5. Williams v Sprint/United Mgmt Co, 230 FRD 640 (D Kan 2005).

6. Ryan ML. Making changes to a medical record: corrections vs. alterations. NORCAL Mutual Insurance Company. Accessed February 3, 2021. http://www.sccma.org/Portals/19/Making%20Changes%20to%20a%20Medical%20Record.pdf

7. AHIMA’s long-term care health information practice and documentation guidelines. The American Health Information Management Association. Published 2014. Accessed February 3, 2021. http://bok.ahima.org/Pages/Long%20Term%20Care%20Guidelines%20TOC/Legal%20Documentation%20Standards/Legal%20Guidelines

1. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Pub L No. 111-5, 123 Stat 115 (2009).

2. Paterick ZR, Patel NJ, Ngo E, et al. Medical liability in the electronic medical records era. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2018;31(4):558-561.

3. Funicelli A. ‘Hidden’ information in your EHRs could increase your liability risk. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(18):12-13.

4. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 26(f), 115th Cong, 1st Sess (2017).

5. Williams v Sprint/United Mgmt Co, 230 FRD 640 (D Kan 2005).

6. Ryan ML. Making changes to a medical record: corrections vs. alterations. NORCAL Mutual Insurance Company. Accessed February 3, 2021. http://www.sccma.org/Portals/19/Making%20Changes%20to%20a%20Medical%20Record.pdf

7. AHIMA’s long-term care health information practice and documentation guidelines. The American Health Information Management Association. Published 2014. Accessed February 3, 2021. http://bok.ahima.org/Pages/Long%20Term%20Care%20Guidelines%20TOC/Legal%20Documentation%20Standards/Legal%20Guidelines

The ABCs of successful vaccinations: A role for psychiatry

While the implementation of mass vaccinations is a public health task, individual clinicians are critical for the success of any vaccination campaign. Psychiatrists may be well positioned to help increase vaccine uptake among psychiatric patients. They see their patients more frequently than primary care physicians do, which allows for patient engagement over time regarding vaccinations. Also, as physicians, psychiatrists are a trusted source of medical information, and they are well-versed in using the tools of nudging and motivational interviewing to manage ambivalence about receiving a vaccine (vaccine hesitancy).1

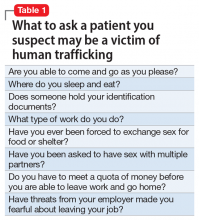

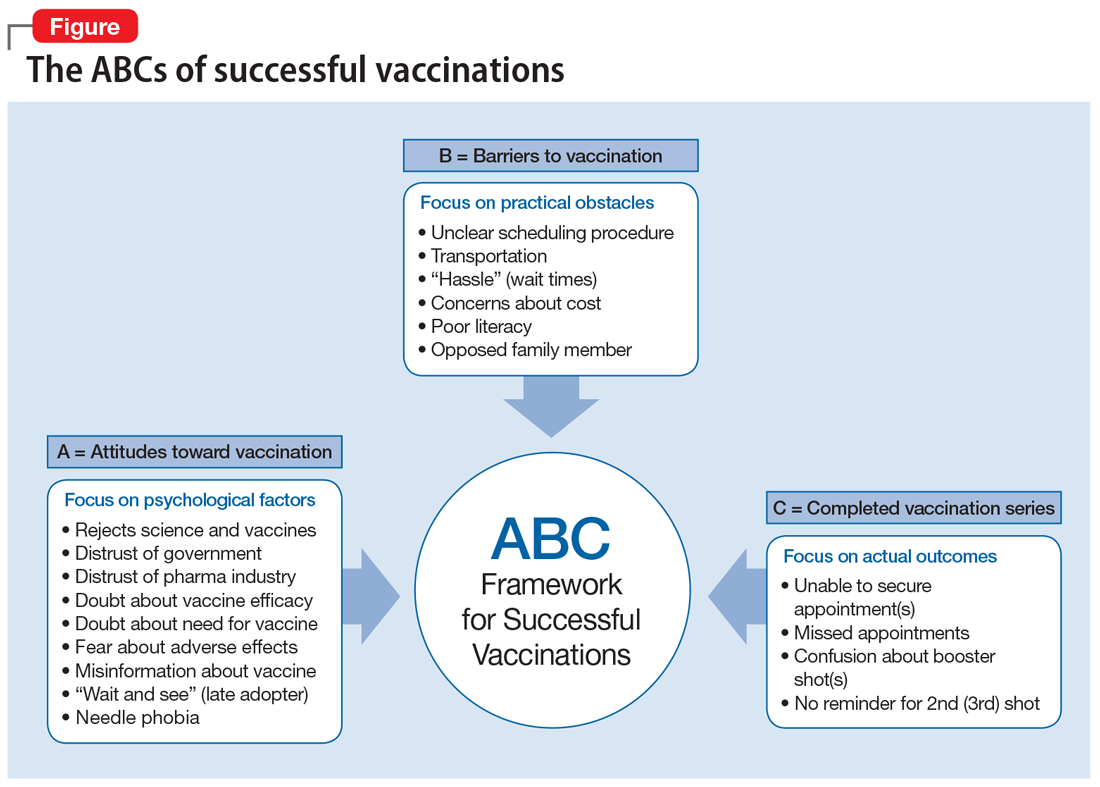

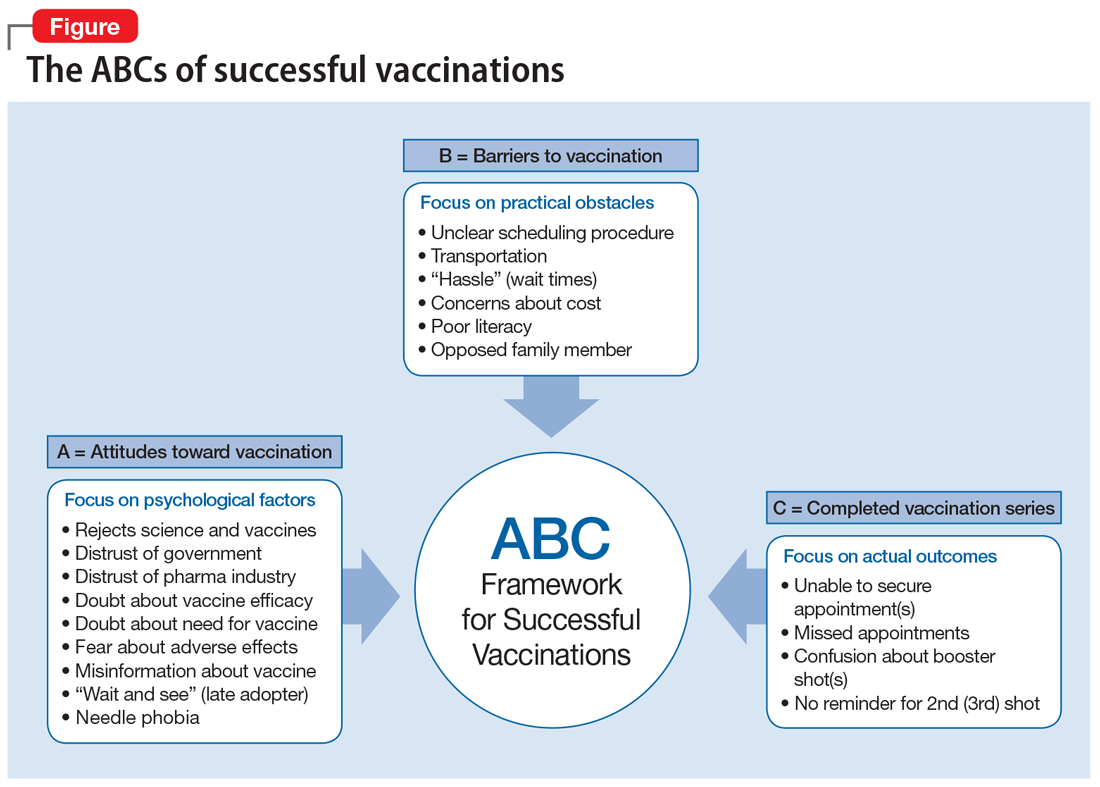

The “ABCs of successful vaccinations” (Figure) provide a framework that psychiatrists can use when speaking with their patients about vaccinations. The ABCs assess psychological factors that hinder acceptance of vaccination (A = Attitudes toward vaccination), practical challenges in vaccine access for patients who are willing to get vaccinated (B = Barriers to vaccination), and the actual outcome of “shot in the arm” (C = Completed vaccination series). The Figure provides examples of each area of focus.

How to talk to patients about vaccines

“Attitudes toward vaccination” is an area in which psychiatrists can potentially move patients from hesitancy to vaccine confidence and acceptance. First, express confidence in the vaccine (ie, make a clear statement: “You are an excellent candidate for this vaccine.”). Then, begin a discussion using presumptive language: “You must be ready to receive the vaccine.” In individuals who hesitate, elicit their concern: “What would make vaccination more acceptable?” In those who agree in principle about the benefits of vaccinations, ask about any impediments: “What would get in the way of getting vaccinated?” While some patients may require more information about the vaccine, others may need more time or mostly concrete help, such as assistance with scheduling a vaccine appointment. Do not to forget to follow up to see if a planned and complete vaccination series has taken place. The CDC offers an excellent online toolkit to help clinicians discuss vaccinations with their patients.2

Psychiatric patients, particularly those from disadvantaged and marginalized populations, have much to gain if psychiatrists are involved in preventive health care, including the coronavirus vaccination drive or the annual flu vaccination campaign.

1. McClure CC, Cataldi JR, O’Leary ST. Vaccine hesitancy: where we are and where we are going. Clin Ther. 2017;39(8):1550-1562.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccination toolkits. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/toolkits.html

While the implementation of mass vaccinations is a public health task, individual clinicians are critical for the success of any vaccination campaign. Psychiatrists may be well positioned to help increase vaccine uptake among psychiatric patients. They see their patients more frequently than primary care physicians do, which allows for patient engagement over time regarding vaccinations. Also, as physicians, psychiatrists are a trusted source of medical information, and they are well-versed in using the tools of nudging and motivational interviewing to manage ambivalence about receiving a vaccine (vaccine hesitancy).1

The “ABCs of successful vaccinations” (Figure) provide a framework that psychiatrists can use when speaking with their patients about vaccinations. The ABCs assess psychological factors that hinder acceptance of vaccination (A = Attitudes toward vaccination), practical challenges in vaccine access for patients who are willing to get vaccinated (B = Barriers to vaccination), and the actual outcome of “shot in the arm” (C = Completed vaccination series). The Figure provides examples of each area of focus.

How to talk to patients about vaccines

“Attitudes toward vaccination” is an area in which psychiatrists can potentially move patients from hesitancy to vaccine confidence and acceptance. First, express confidence in the vaccine (ie, make a clear statement: “You are an excellent candidate for this vaccine.”). Then, begin a discussion using presumptive language: “You must be ready to receive the vaccine.” In individuals who hesitate, elicit their concern: “What would make vaccination more acceptable?” In those who agree in principle about the benefits of vaccinations, ask about any impediments: “What would get in the way of getting vaccinated?” While some patients may require more information about the vaccine, others may need more time or mostly concrete help, such as assistance with scheduling a vaccine appointment. Do not to forget to follow up to see if a planned and complete vaccination series has taken place. The CDC offers an excellent online toolkit to help clinicians discuss vaccinations with their patients.2

Psychiatric patients, particularly those from disadvantaged and marginalized populations, have much to gain if psychiatrists are involved in preventive health care, including the coronavirus vaccination drive or the annual flu vaccination campaign.

While the implementation of mass vaccinations is a public health task, individual clinicians are critical for the success of any vaccination campaign. Psychiatrists may be well positioned to help increase vaccine uptake among psychiatric patients. They see their patients more frequently than primary care physicians do, which allows for patient engagement over time regarding vaccinations. Also, as physicians, psychiatrists are a trusted source of medical information, and they are well-versed in using the tools of nudging and motivational interviewing to manage ambivalence about receiving a vaccine (vaccine hesitancy).1

The “ABCs of successful vaccinations” (Figure) provide a framework that psychiatrists can use when speaking with their patients about vaccinations. The ABCs assess psychological factors that hinder acceptance of vaccination (A = Attitudes toward vaccination), practical challenges in vaccine access for patients who are willing to get vaccinated (B = Barriers to vaccination), and the actual outcome of “shot in the arm” (C = Completed vaccination series). The Figure provides examples of each area of focus.

How to talk to patients about vaccines

“Attitudes toward vaccination” is an area in which psychiatrists can potentially move patients from hesitancy to vaccine confidence and acceptance. First, express confidence in the vaccine (ie, make a clear statement: “You are an excellent candidate for this vaccine.”). Then, begin a discussion using presumptive language: “You must be ready to receive the vaccine.” In individuals who hesitate, elicit their concern: “What would make vaccination more acceptable?” In those who agree in principle about the benefits of vaccinations, ask about any impediments: “What would get in the way of getting vaccinated?” While some patients may require more information about the vaccine, others may need more time or mostly concrete help, such as assistance with scheduling a vaccine appointment. Do not to forget to follow up to see if a planned and complete vaccination series has taken place. The CDC offers an excellent online toolkit to help clinicians discuss vaccinations with their patients.2

Psychiatric patients, particularly those from disadvantaged and marginalized populations, have much to gain if psychiatrists are involved in preventive health care, including the coronavirus vaccination drive or the annual flu vaccination campaign.

1. McClure CC, Cataldi JR, O’Leary ST. Vaccine hesitancy: where we are and where we are going. Clin Ther. 2017;39(8):1550-1562.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccination toolkits. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/toolkits.html

1. McClure CC, Cataldi JR, O’Leary ST. Vaccine hesitancy: where we are and where we are going. Clin Ther. 2017;39(8):1550-1562.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccination toolkits. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/toolkits.html

Suvorexant: An option for preventing delirium?

Delirium is characterized by a disturbance of consciousness or cognition that typically has a rapid onset and fluctuating course.1 Up to 42% of hospitalized geriatric patients experience delirium.1 Approximately 10% to 31% of these patients have the condition upon admission, and the remainder develop it during their hospitalization.1 Unfortunately, options for preventing or treating delirium are limited. Benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications have been used to treat problematic behaviors associated with delirium, but they do not effectively reduce the occurrence, duration, or severity of this condition.2,3

Recent evidence suggests that suvorexant, which is FDA-approved for insomnia, may be useful for preventing delirium. Suvorexant—a dual orexin receptor (OX1R, OX2R) antagonist—promotes sleep onset and maintenance, and is associated with normal measures of sleep activity such as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, non-REM sleep, and sleep stage–specific electroencephalographic profiles.4 Here we review 3 studies that evaluated suvorexant for preventing delirium.

Hatta et al.5 In this randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded, multicenter study, 72 patients (age 65 to 89) newly admitted to an ICU were randomized to suvorexant, 15 mg/d, (n = 36) or placebo (n = 36) for 3 days.5 None of the patients taking suvorexant developed delirium, whereas 17% (6 patients) in the placebo group did (P = .025).5

Azuma et al.6 In this 7-day, blinded, randomized study of 70 adult patients (age ≥20) admitted to an ICU, 34 participants received suvorexant (15 mg nightly for age <65, 20 mg nightly for age ≥65) and the rest received treatment as usual (TAU). Suvorexant was associated with a lower incidence of delirium symptoms (n = 6, 17.6%) compared with TAU (n = 17, 47.2%) (P = .011).6 The onset of delirium was earlier in the TAU group (P < .05).6

Hatta et al.7 In this large prospective, observational study of adults (age >65), 526 patients with significant risk factors for delirium were prescribed suvorexant and/or ramelteon. Approximately 16% of the patients who received either or both of these medications met DSM-5 criteria for delirium, compared with 24% who did not receive these medications (P = .005).7

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jakob Evans, BS, for compiling much of the research for this article.

1. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364.

2. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(4):CD006379.

3. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6(6):CD005594.

4. Coleman PJ, Gotter AL, Herring WJ, et al. The discovery of suvorexant, the first orexin receptor drug for insomnia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:509-533.

5. Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Preventive effects of suvorexant on delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(8):e970-e979.

6. Azuma K, Takaesu Y, Soeda H, et al. Ability of suvorexant to prevent delirium in patients in the intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Acute Med Surg. 2018;5(4):362-368.

7. Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Real-world effectiveness of ramelteon and suvorexant for delirium prevention in 948 patients with delirium risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;81(1):19m12865. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19m12865

Delirium is characterized by a disturbance of consciousness or cognition that typically has a rapid onset and fluctuating course.1 Up to 42% of hospitalized geriatric patients experience delirium.1 Approximately 10% to 31% of these patients have the condition upon admission, and the remainder develop it during their hospitalization.1 Unfortunately, options for preventing or treating delirium are limited. Benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications have been used to treat problematic behaviors associated with delirium, but they do not effectively reduce the occurrence, duration, or severity of this condition.2,3

Recent evidence suggests that suvorexant, which is FDA-approved for insomnia, may be useful for preventing delirium. Suvorexant—a dual orexin receptor (OX1R, OX2R) antagonist—promotes sleep onset and maintenance, and is associated with normal measures of sleep activity such as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, non-REM sleep, and sleep stage–specific electroencephalographic profiles.4 Here we review 3 studies that evaluated suvorexant for preventing delirium.

Hatta et al.5 In this randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded, multicenter study, 72 patients (age 65 to 89) newly admitted to an ICU were randomized to suvorexant, 15 mg/d, (n = 36) or placebo (n = 36) for 3 days.5 None of the patients taking suvorexant developed delirium, whereas 17% (6 patients) in the placebo group did (P = .025).5

Azuma et al.6 In this 7-day, blinded, randomized study of 70 adult patients (age ≥20) admitted to an ICU, 34 participants received suvorexant (15 mg nightly for age <65, 20 mg nightly for age ≥65) and the rest received treatment as usual (TAU). Suvorexant was associated with a lower incidence of delirium symptoms (n = 6, 17.6%) compared with TAU (n = 17, 47.2%) (P = .011).6 The onset of delirium was earlier in the TAU group (P < .05).6

Hatta et al.7 In this large prospective, observational study of adults (age >65), 526 patients with significant risk factors for delirium were prescribed suvorexant and/or ramelteon. Approximately 16% of the patients who received either or both of these medications met DSM-5 criteria for delirium, compared with 24% who did not receive these medications (P = .005).7

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jakob Evans, BS, for compiling much of the research for this article.

Delirium is characterized by a disturbance of consciousness or cognition that typically has a rapid onset and fluctuating course.1 Up to 42% of hospitalized geriatric patients experience delirium.1 Approximately 10% to 31% of these patients have the condition upon admission, and the remainder develop it during their hospitalization.1 Unfortunately, options for preventing or treating delirium are limited. Benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications have been used to treat problematic behaviors associated with delirium, but they do not effectively reduce the occurrence, duration, or severity of this condition.2,3

Recent evidence suggests that suvorexant, which is FDA-approved for insomnia, may be useful for preventing delirium. Suvorexant—a dual orexin receptor (OX1R, OX2R) antagonist—promotes sleep onset and maintenance, and is associated with normal measures of sleep activity such as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, non-REM sleep, and sleep stage–specific electroencephalographic profiles.4 Here we review 3 studies that evaluated suvorexant for preventing delirium.

Hatta et al.5 In this randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded, multicenter study, 72 patients (age 65 to 89) newly admitted to an ICU were randomized to suvorexant, 15 mg/d, (n = 36) or placebo (n = 36) for 3 days.5 None of the patients taking suvorexant developed delirium, whereas 17% (6 patients) in the placebo group did (P = .025).5

Azuma et al.6 In this 7-day, blinded, randomized study of 70 adult patients (age ≥20) admitted to an ICU, 34 participants received suvorexant (15 mg nightly for age <65, 20 mg nightly for age ≥65) and the rest received treatment as usual (TAU). Suvorexant was associated with a lower incidence of delirium symptoms (n = 6, 17.6%) compared with TAU (n = 17, 47.2%) (P = .011).6 The onset of delirium was earlier in the TAU group (P < .05).6

Hatta et al.7 In this large prospective, observational study of adults (age >65), 526 patients with significant risk factors for delirium were prescribed suvorexant and/or ramelteon. Approximately 16% of the patients who received either or both of these medications met DSM-5 criteria for delirium, compared with 24% who did not receive these medications (P = .005).7

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jakob Evans, BS, for compiling much of the research for this article.

1. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364.

2. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(4):CD006379.

3. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6(6):CD005594.

4. Coleman PJ, Gotter AL, Herring WJ, et al. The discovery of suvorexant, the first orexin receptor drug for insomnia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:509-533.

5. Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Preventive effects of suvorexant on delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(8):e970-e979.

6. Azuma K, Takaesu Y, Soeda H, et al. Ability of suvorexant to prevent delirium in patients in the intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Acute Med Surg. 2018;5(4):362-368.

7. Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Real-world effectiveness of ramelteon and suvorexant for delirium prevention in 948 patients with delirium risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;81(1):19m12865. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19m12865

1. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364.

2. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(4):CD006379.

3. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6(6):CD005594.

4. Coleman PJ, Gotter AL, Herring WJ, et al. The discovery of suvorexant, the first orexin receptor drug for insomnia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:509-533.

5. Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Preventive effects of suvorexant on delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(8):e970-e979.

6. Azuma K, Takaesu Y, Soeda H, et al. Ability of suvorexant to prevent delirium in patients in the intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Acute Med Surg. 2018;5(4):362-368.

7. Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Real-world effectiveness of ramelteon and suvorexant for delirium prevention in 948 patients with delirium risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;81(1):19m12865. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19m12865

Key questions to ask patients who are veterans

The Mission Act—signed into law in 2018—recognizes that the health care needs of patients who are veterans can no longer be fully served by the Veterans Health Administration.1 This act allows some veterans who are enrolled in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system or otherwise entitled to VA care to access treatment outside of VA facilities.1 As a result, psychiatrists may treat veterans more frequently.

During such patients’ initial visit, obtaining a detailed history of their military service can reveal vital clinical information and establish a therapeutic alliance that can help foster positive treatment outcomes. Here we offer an A-to-L list of important questions to ask veterans about their military service, and explanations of why these questions are valuable.

Attained rank. What rank did you attain during your military service? Did you retire from the military? How many years did you serve?

Asking about your patient’s rank, retirement status, and time in service is vital to understanding their military experience. By military law, only individuals who retired from the military can use their rank as an identifier after they leave the military, although some veterans may not wish to be called by their rank in a clinical setting.

Branch. Which branch of the military did you serve? Were you in Active Duty, the Reserves, or the National Guard?

Military members often take great pride in service of their specific branch. Each branch has its own language, culture, values, and exposures. If your patient has served in a combination of Active Duty, Reserves, and/or National Guard, ask how much time they spent in each.

Culture. What part of the military culture was positive or negative for you?

Continue to: There is a clear culture...

There is a clear culture within the military. Some veterans may feel lost without the military structure, and even devalued without the respect of rank. Others may feel jaded and spiteful about the strict military culture, procedures, and expectations.

Discharge. When, why, and under what circumstances were you discharged? What type of discharge did you receive?

There are 6 types of discharge: Honorable, General, Other than Honorable (OTH), Entry Level Separation, Bad Conduct, and Dishonorable. The type of discharge a veteran received may impact what resources are available to them. It also can influence a veteran’s perception of their military career.

Exposures. Were you exposed to combat, death, explosive blasts, or hazardous chemicals?

Do not ask a veteran if they have killed anyone. This question is both disrespectful and highly presumptuous because most veterans have not killed anyone. Be respectful of their experiences. Depending on the veteran’s mission, they may have unique exposures (Agent Orange, burn pits, detainee camps, etc.). Consider asking follow-up questions to learn the details of these exposures.

Continue to: Family impact

Family impact. How has your military service impacted your family?

A veteran’s military service often affects family members. Deployments can cause strain on marital relationships, children’s birthdays and special events may be missed, and extended family may have negative reactions to military service. Understanding the impact on the veteran’s family members can help uncover potential stressful relationships as well as help enhance any positive support systems that are available at home.

Go. Where were you stationed? Were you deployed?

Training location, geography of combat theater, peace-keeping locations, and area of station can all profoundly impact a veteran’s military experience. Ask follow-up questions about their duty stations, deployment locations, and experiences with these locations.

Hot water. Did you ever get into “trouble” while serving the military (eg, lose rank, get arrested, etc.)? How did you respond to the military’s method of discipline?

Continue to: Although it may be difficult...

Although it may be difficult or uncomfortable to ask your patient if they experienced any disciplinary action, this information may prove useful. It can help provide context when you discuss the veteran’s ease of assimilation into civilian life and other important information regarding the type of discharge.

Injuries. Have you experienced any moral, physical, sexual, emotional, or concussive injuries?

Moral injury, guilt, and regret are common for veterans. Not all injuries are from combat. Your patient may have experienced sexual assault, hazing rituals, pranks, etc.

Job. What was your job in the military? What kind of security clearance did you have?

Note that not all veterans’ “jobs” in the military accurately reflect the duties and tasks that they actually performed. Security clearance will often influence the duties and tasks they were required to perform.

Continue to: Keeping it inside

Keeping it inside. Do you have anyone to talk with about your military experiences?

Many veterans feel uncomfortable discussing their experiences with others. Some veterans may be concerned that others will not understand what they went through. Some might perceive that disclosing their experiences could burden other people, or they may be concerned that explaining their experiences may be too shocking. Asking this question may present an opportunity for you to suggest psychotherapy for your patient.

Life as a civilian. How is your life different as a civilian? How have you adjusted to civilian life?

During the process of assimilation into civilian life, veterans may experience symptoms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or other disorders. These symptoms may emerge and/or become exacerbated during their transition to civilian life.

1. VA MISSION Act of 2018 (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act), S 2372, 115th Cong, 2nd Sess, HR Doc No. 115-671 (2018).

The Mission Act—signed into law in 2018—recognizes that the health care needs of patients who are veterans can no longer be fully served by the Veterans Health Administration.1 This act allows some veterans who are enrolled in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system or otherwise entitled to VA care to access treatment outside of VA facilities.1 As a result, psychiatrists may treat veterans more frequently.

During such patients’ initial visit, obtaining a detailed history of their military service can reveal vital clinical information and establish a therapeutic alliance that can help foster positive treatment outcomes. Here we offer an A-to-L list of important questions to ask veterans about their military service, and explanations of why these questions are valuable.

Attained rank. What rank did you attain during your military service? Did you retire from the military? How many years did you serve?

Asking about your patient’s rank, retirement status, and time in service is vital to understanding their military experience. By military law, only individuals who retired from the military can use their rank as an identifier after they leave the military, although some veterans may not wish to be called by their rank in a clinical setting.

Branch. Which branch of the military did you serve? Were you in Active Duty, the Reserves, or the National Guard?

Military members often take great pride in service of their specific branch. Each branch has its own language, culture, values, and exposures. If your patient has served in a combination of Active Duty, Reserves, and/or National Guard, ask how much time they spent in each.

Culture. What part of the military culture was positive or negative for you?

Continue to: There is a clear culture...

There is a clear culture within the military. Some veterans may feel lost without the military structure, and even devalued without the respect of rank. Others may feel jaded and spiteful about the strict military culture, procedures, and expectations.

Discharge. When, why, and under what circumstances were you discharged? What type of discharge did you receive?

There are 6 types of discharge: Honorable, General, Other than Honorable (OTH), Entry Level Separation, Bad Conduct, and Dishonorable. The type of discharge a veteran received may impact what resources are available to them. It also can influence a veteran’s perception of their military career.

Exposures. Were you exposed to combat, death, explosive blasts, or hazardous chemicals?

Do not ask a veteran if they have killed anyone. This question is both disrespectful and highly presumptuous because most veterans have not killed anyone. Be respectful of their experiences. Depending on the veteran’s mission, they may have unique exposures (Agent Orange, burn pits, detainee camps, etc.). Consider asking follow-up questions to learn the details of these exposures.

Continue to: Family impact

Family impact. How has your military service impacted your family?

A veteran’s military service often affects family members. Deployments can cause strain on marital relationships, children’s birthdays and special events may be missed, and extended family may have negative reactions to military service. Understanding the impact on the veteran’s family members can help uncover potential stressful relationships as well as help enhance any positive support systems that are available at home.

Go. Where were you stationed? Were you deployed?

Training location, geography of combat theater, peace-keeping locations, and area of station can all profoundly impact a veteran’s military experience. Ask follow-up questions about their duty stations, deployment locations, and experiences with these locations.

Hot water. Did you ever get into “trouble” while serving the military (eg, lose rank, get arrested, etc.)? How did you respond to the military’s method of discipline?

Continue to: Although it may be difficult...

Although it may be difficult or uncomfortable to ask your patient if they experienced any disciplinary action, this information may prove useful. It can help provide context when you discuss the veteran’s ease of assimilation into civilian life and other important information regarding the type of discharge.

Injuries. Have you experienced any moral, physical, sexual, emotional, or concussive injuries?

Moral injury, guilt, and regret are common for veterans. Not all injuries are from combat. Your patient may have experienced sexual assault, hazing rituals, pranks, etc.

Job. What was your job in the military? What kind of security clearance did you have?

Note that not all veterans’ “jobs” in the military accurately reflect the duties and tasks that they actually performed. Security clearance will often influence the duties and tasks they were required to perform.

Continue to: Keeping it inside

Keeping it inside. Do you have anyone to talk with about your military experiences?

Many veterans feel uncomfortable discussing their experiences with others. Some veterans may be concerned that others will not understand what they went through. Some might perceive that disclosing their experiences could burden other people, or they may be concerned that explaining their experiences may be too shocking. Asking this question may present an opportunity for you to suggest psychotherapy for your patient.

Life as a civilian. How is your life different as a civilian? How have you adjusted to civilian life?

During the process of assimilation into civilian life, veterans may experience symptoms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or other disorders. These symptoms may emerge and/or become exacerbated during their transition to civilian life.

The Mission Act—signed into law in 2018—recognizes that the health care needs of patients who are veterans can no longer be fully served by the Veterans Health Administration.1 This act allows some veterans who are enrolled in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system or otherwise entitled to VA care to access treatment outside of VA facilities.1 As a result, psychiatrists may treat veterans more frequently.

During such patients’ initial visit, obtaining a detailed history of their military service can reveal vital clinical information and establish a therapeutic alliance that can help foster positive treatment outcomes. Here we offer an A-to-L list of important questions to ask veterans about their military service, and explanations of why these questions are valuable.

Attained rank. What rank did you attain during your military service? Did you retire from the military? How many years did you serve?

Asking about your patient’s rank, retirement status, and time in service is vital to understanding their military experience. By military law, only individuals who retired from the military can use their rank as an identifier after they leave the military, although some veterans may not wish to be called by their rank in a clinical setting.

Branch. Which branch of the military did you serve? Were you in Active Duty, the Reserves, or the National Guard?

Military members often take great pride in service of their specific branch. Each branch has its own language, culture, values, and exposures. If your patient has served in a combination of Active Duty, Reserves, and/or National Guard, ask how much time they spent in each.

Culture. What part of the military culture was positive or negative for you?

Continue to: There is a clear culture...

There is a clear culture within the military. Some veterans may feel lost without the military structure, and even devalued without the respect of rank. Others may feel jaded and spiteful about the strict military culture, procedures, and expectations.

Discharge. When, why, and under what circumstances were you discharged? What type of discharge did you receive?

There are 6 types of discharge: Honorable, General, Other than Honorable (OTH), Entry Level Separation, Bad Conduct, and Dishonorable. The type of discharge a veteran received may impact what resources are available to them. It also can influence a veteran’s perception of their military career.

Exposures. Were you exposed to combat, death, explosive blasts, or hazardous chemicals?

Do not ask a veteran if they have killed anyone. This question is both disrespectful and highly presumptuous because most veterans have not killed anyone. Be respectful of their experiences. Depending on the veteran’s mission, they may have unique exposures (Agent Orange, burn pits, detainee camps, etc.). Consider asking follow-up questions to learn the details of these exposures.

Continue to: Family impact

Family impact. How has your military service impacted your family?

A veteran’s military service often affects family members. Deployments can cause strain on marital relationships, children’s birthdays and special events may be missed, and extended family may have negative reactions to military service. Understanding the impact on the veteran’s family members can help uncover potential stressful relationships as well as help enhance any positive support systems that are available at home.

Go. Where were you stationed? Were you deployed?

Training location, geography of combat theater, peace-keeping locations, and area of station can all profoundly impact a veteran’s military experience. Ask follow-up questions about their duty stations, deployment locations, and experiences with these locations.

Hot water. Did you ever get into “trouble” while serving the military (eg, lose rank, get arrested, etc.)? How did you respond to the military’s method of discipline?

Continue to: Although it may be difficult...

Although it may be difficult or uncomfortable to ask your patient if they experienced any disciplinary action, this information may prove useful. It can help provide context when you discuss the veteran’s ease of assimilation into civilian life and other important information regarding the type of discharge.

Injuries. Have you experienced any moral, physical, sexual, emotional, or concussive injuries?

Moral injury, guilt, and regret are common for veterans. Not all injuries are from combat. Your patient may have experienced sexual assault, hazing rituals, pranks, etc.

Job. What was your job in the military? What kind of security clearance did you have?

Note that not all veterans’ “jobs” in the military accurately reflect the duties and tasks that they actually performed. Security clearance will often influence the duties and tasks they were required to perform.

Continue to: Keeping it inside

Keeping it inside. Do you have anyone to talk with about your military experiences?

Many veterans feel uncomfortable discussing their experiences with others. Some veterans may be concerned that others will not understand what they went through. Some might perceive that disclosing their experiences could burden other people, or they may be concerned that explaining their experiences may be too shocking. Asking this question may present an opportunity for you to suggest psychotherapy for your patient.

Life as a civilian. How is your life different as a civilian? How have you adjusted to civilian life?

During the process of assimilation into civilian life, veterans may experience symptoms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or other disorders. These symptoms may emerge and/or become exacerbated during their transition to civilian life.

1. VA MISSION Act of 2018 (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act), S 2372, 115th Cong, 2nd Sess, HR Doc No. 115-671 (2018).

1. VA MISSION Act of 2018 (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act), S 2372, 115th Cong, 2nd Sess, HR Doc No. 115-671 (2018).

Helping survivors of human trafficking

Human trafficking (HT) is a secretive, multibillion dollar criminal industry involving the use of coercion, threats, and fraud to force individuals to engage in labor or commercial sex acts. In 2017, the International Labour Organization estimated that 24.9 million people worldwide were victims of forced labor (ie, working under threat or coercion).1 Risk factors for individuals who are vulnerable to HT include recent migration, substance use, housing insecurity, runaway youth, and mental illness. Traffickers continue the cycle of HT through isolation and emotional, physical, financial, and verbal abuse.

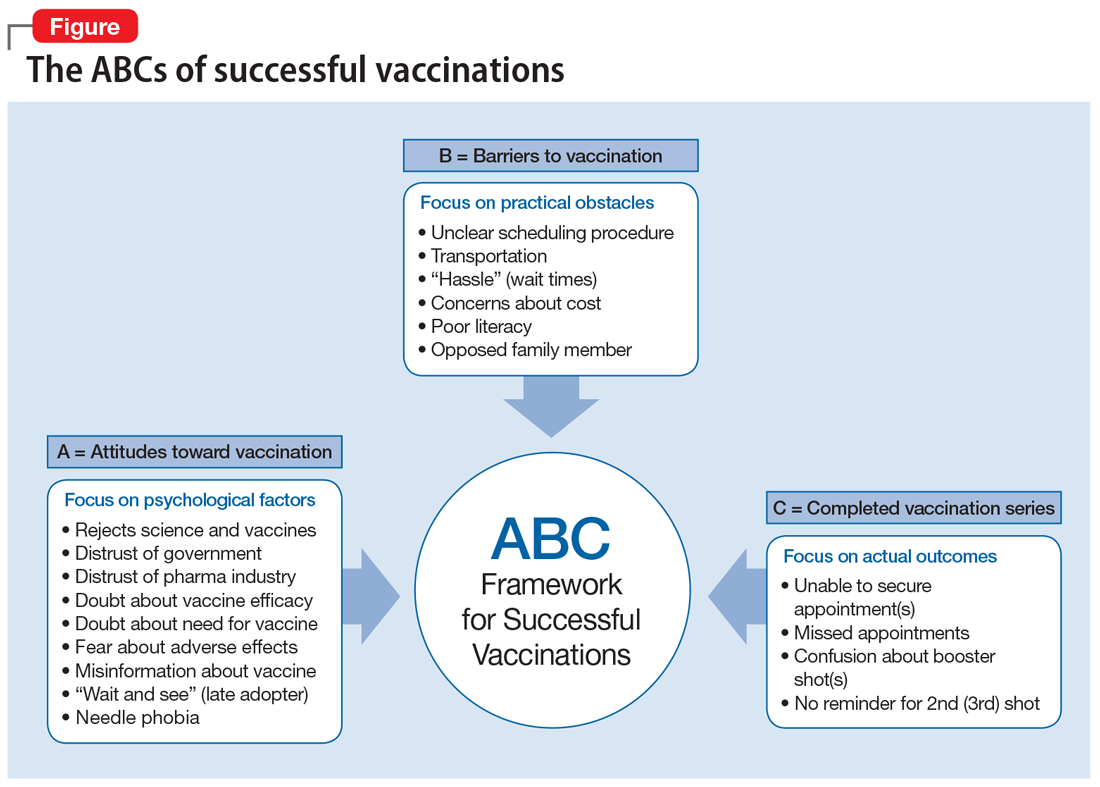

Survivors of HT may avoid seeking health care due to cultural reasons or feelings of guilt, isolation, distrust, or fear of criminal sanctions. There can be missed opportunities for victims to obtain help through health care services, law enforcement, child welfare services, or even family or friends. In a study of 173 survivors of HT in the United States, 68% of those who were currently trafficked visited with a health care professional at least once and were not identified as being trafficked.2 Psychiatrists rarely receive education on HT, which can lead to missed opportunities for identifying victims. Table 1 lists screening questions psychiatrists can ask patients they suspect may be trafficked.

The psychiatric sequelae of trafficking

Survivors of HT commonly experience psychiatric illness, substance use, pain, sexually transmitted diseases, and unplanned pregnancies.3 Here we discuss some of the psychiatric conditions that are common among HT survivors, and outline a multidisciplinary approach to their care.

PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Studies suggest survivors of HT who seek care have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 Survivors may have experienced multiple repetitive trauma, such as physical and sexual abuse.3 Compared with survivors of forced labor trafficking, survivors of sex trafficking have higher rates of childhood abuse, violence during trafficking, severe symptoms of PTSD, and comorbid depression and PTSD.4 For survivors with PTSD, consider psychosocial interventions that address social support, coping strategies, and community reintegration.5 Survivors can also benefit from trauma-informed care that focuses on the cognitive aspect of the trauma, such as cognitive processing therapy, which involves cognitive restructuring without a written account of the trauma.6