User login

Caring for LGBTQ+ Patients with IBD

Cases

Patient 1: 55-year-old cis-male, who identifies as gay, has ulcerative colitis that has been refractory to multiple biologic therapies. His provider recommends a total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (TPC with IPAA), but the patient has questions regarding sexual function following surgery. Specifically, he is wondering when, or if, he can resume receptive anal intercourse. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: 25-year-old, trans-female, status-post vaginoplasty with use of sigmoid colon and with well-controlled ulcerative colitis, presents with vaginal discharge, weight loss, and rectal bleeding. How do you explain what has happened to her? During your discussion, she also asks you why her chart continues to use her “dead name.” How do you respond?

Patient 3: 32-year-old, cis-female, G2P2, who identifies as a lesbian, has active ulcerative colitis. She wants to discuss medical or surgical therapy and future pregnancies. How would you counsel her?

Many gastroenterologists would likely know how to address patient 3’s concerns, but the concerns of patients 1 and 2 often go unaddressed or dismissed. Numerous studies and surveys have been conducted on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but the focus of these studies has always been through a heteronormative cisgender lens. The focus of many studies is on fertility or sexual health and function in cisgender, heteronormative individuals.1-3 In the last few years, however, there has been increasing awareness of the health disparities, stigma, and discrimination that sexual and gender minorities (SGM) experience.4-6 For the purposes of this discussion, individuals within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community will be referred to as SGM. We recognize that even this exhaustive listing above does not acknowledge the full spectrum of diversity within the SGM community.

Clinical Care/Competency for SGM with IBD is Lacking

Almost 10% of the US population identifies as some form of SGM, and that number can be higher within the younger generations.4 SGM patients tend to delay or avoid seeking health care due to concern for provider mistreatment or lack of regard for their individual concerns. Additionally, there are several gaps in clinical knowledge about caring for SGM individuals. Little is known regarding the incidence or prevalence of IBD in SGM populations, but it is perceived to be similar to cisgender heterosexual individuals. Furthermore, as Newman et al. highlighted in their systematic review published in May 2023, there is a lack of guidance regarding sexual activity in the setting of IBD in SGM individuals.5 There is also a significant lack of knowledge on the impact of gender-affirming care on the natural history and treatments of IBD in transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals. This can impact providers’ comfort and competence in caring for TGNC individuals.

Another important point to make is that the SGM community still faces discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity to this day, which impacts the quality and delivery of their care.7 Culturally-competent care should include care that is free from stigma, implicit and explicit biases, and discrimination. In 2011, an Institute of Medicine report documented, among other issues, provider discomfort in delivering care to SGM patients.8 While SGM individuals prefer a provider who acknowledges their sexual orientation and gender identity and treats them with the dignity and respect they deserve, many SGM individuals share valid concerns regarding their safety, which impact their desire to disclose their identity to health care providers.9 This certainly can have an impact on the quality of care they receive, including important health maintenance milestones and cancer screenings.10

An internal survey at our institution of providers (nurses, physician assistants, surgeons, and physicians) found that among 85 responders, 70% have cared for SGM who have undergone TPC with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). Of these, 75% did not ask about sexual orientation or practices before pouch formation (though almost all of them agreed it would be important to ask). A total of 55% were comfortable in discussing SGM-related concerns; 53% did not feel comfortable discussing sexual orientation or practices; and in particular when it came to anoreceptive intercourse (ARI), 73% did not feel confident discussing recommendations.11

All of these issues highlight the importance of developing curricula that focus on reducing implicit and explicit biases towards SGM individuals and increasing the competence of providers to take care of SGM individuals in a safe space.

Additionally, it further justifies the need for ethical research that focuses on the needs of SGM individuals to guide evidence-based approaches to care. Given the implicit and explicit heterosexism and transphobia in society and many health care systems, Rainbows in Gastro was formed as an advocacy group for SGM patients, trainees, and staff in gastroenterology and hepatology.4

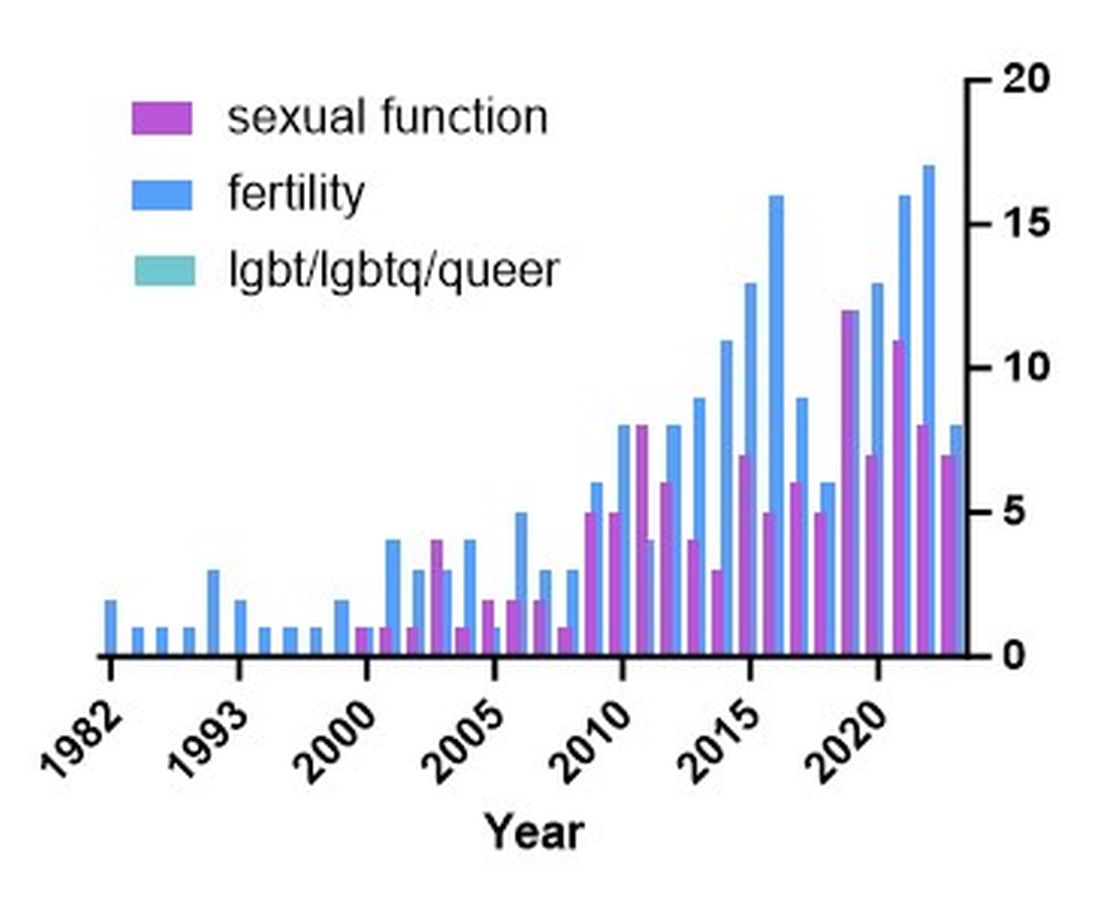

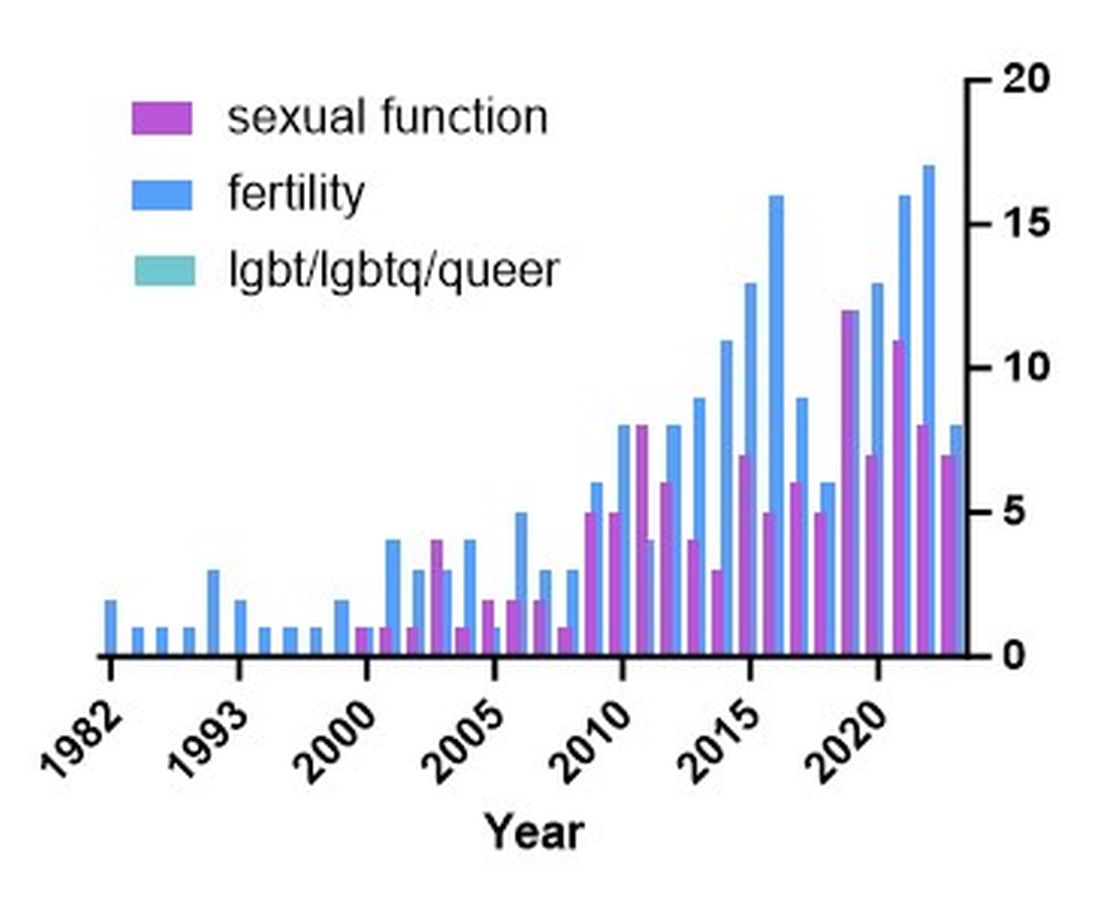

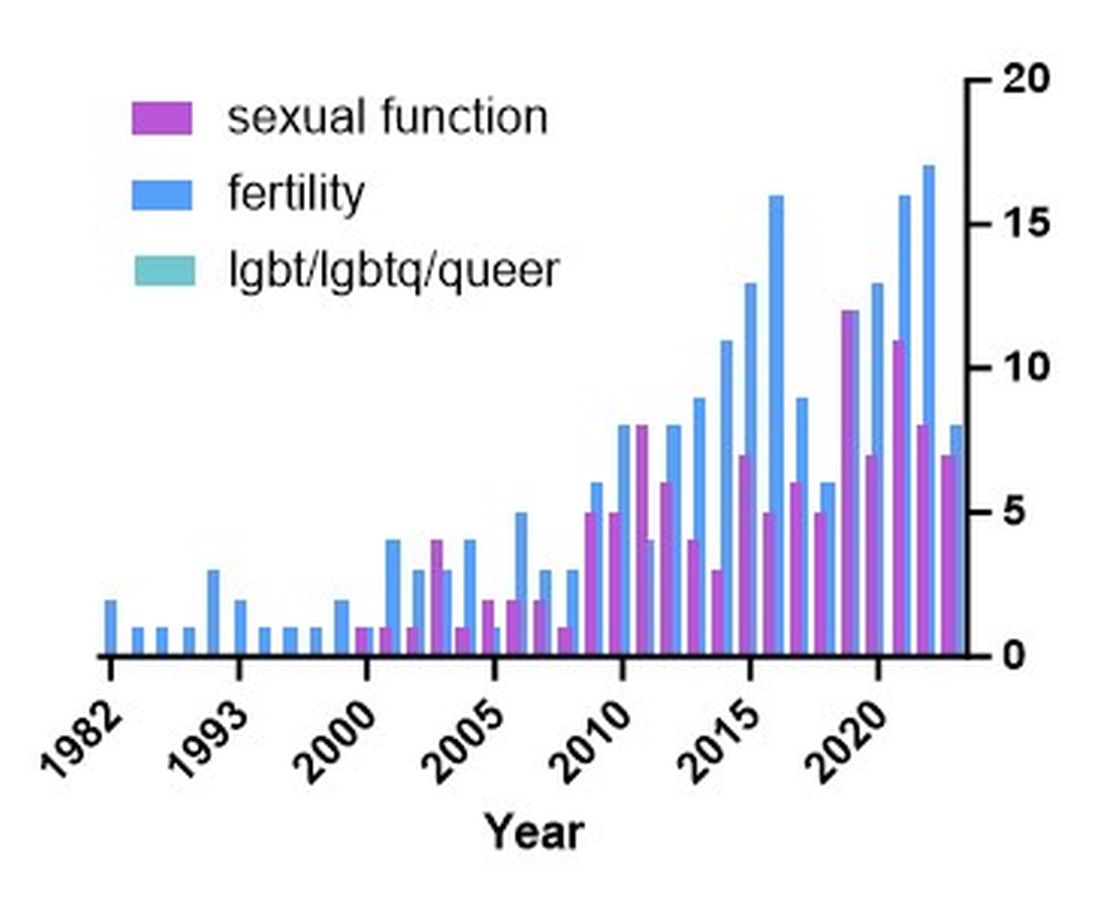

Research in SGM and IBD is lacking

There are additional needs for research in IBD and how it pertains to the needs of SGM individuals. Figure 1 highlights the lack of PubMed results for the search terms “IBD + LGBT,” “IBD + LGBTQ,” or “IBD + queer.” In contrast, the search terms “IBD + fertility” and “IBD + sexual dysfunction” generate many results. Even a systemic review conducted by Newman et al. of multiple databases in 2022 found only seven articles that demonstrated appropriately performed studies on SGM patients with IBD.5 This highlights the significant dearth of research in the realm of SGM health in IBD.

Newman and colleagues have recently published research considerations for SGM individuals. They highlighted the need to include understanding the “unique combination of psychosocial, biomedical, and legal experiences” that results in different needs and outcomes. There were several areas identified, including minority stress, which comes from existence of being SGM, especially as transgender individuals face increasing legal challenges in a variety of settings, not just healthcare.6 In a retrospective chart review investigating social determinants of health in SGM-IBD populations,12 36% of patients reported some level of social isolation, and almost 50% reported some level of stress. A total of 40% of them self-reported some perceived level of risk with respect to employment, and 17% reported depression. Given that this was a chart review and not a strict questionnaire, this study was certainly limited, and we would hypothesize that these numbers are therefore underestimating the true proportion of SGM-IBD patients who deal with employment concerns, social isolation, or psychological distress.

What Next? Back to the Patients

Circling back to our patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them? In patient 1’s case, we would inform him that pelvic surgery can increase the risk for sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction. He additionally would be advised during a staged TPC with IPAA, he may experience issues with body image. However, should he desire to participate in receptive anal intercourse after completion of his surgeries, the general recommendation would be to wait at least 6 months and with proven remission. It should further be noted that these are not formalized recommendations, only highlighting the need for more research and consensus on standards of care for SGM patients. He should finally be told that because he has ulcerative colitis, removal of the colon does not remove the risk for future intestinal involvement such as possible pouchitis.

In patient 2’s case, she is likely experiencing diversion vaginitis related to use of her colon for her neo-vagina. She should undergo colonoscopy and vaginoscopy in addition to standard work-up for her known ulcerative colitis.13 Management should be done in a multidisciplinary approach between the IBD provider, gynecologist, and gender-affirming provider. The electronic medical record should be updated to reflect the patient’s preferred name, pronouns, and gender identity, and her medical records, including automated clinical reports, should be updated accordingly.

As for patient 3, she would be counseled according to well-documented guidelines on pregnancy and IBD, including risks of medications (such as Jak inhibitors or methotrexate) versus the risk of uncontrolled IBD during pregnancy.1

Regardless of a patient’s gender identity or sexual orientation, patient-centered, culturally competent, and sensitive care should be provided. At Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we started one of the first Pride in IBD Clinics, which focuses on the care of SGM individuals with IBD. Our focus is to address the needs of patients who belong to the SGM community in a wholistic approach within a safe space (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYa_zYaCA6M; https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/inflammatory-bowel-disease-clinic/overview/ovc-20357763). Our process of developing the clinic included training all staff on proper communication and cultural sensitivity for the SGM community.

Furthermore, providing welcoming and affirming signs of inclusivity for SGM individuals at the provider’s office — including but not limited to rainbow progressive flags, gender-neutral bathroom signs, or pronoun pins on provider identification badges (see Figure 2) — are usually appreciated by patients. Ensuring that patient education materials do not assume gender (for example, using the term “parents” rather than “mother and father”) and using gender neutral terms on intake forms is very important. Inclusive communication includes providers introducing themselves by preferred name and pronouns, asking the patients to introduce themselves, and welcoming them to share their pronouns. These simple actions can provide an atmosphere of safety for SGM patients, which would serve to enhance the quality of care we can provide for them.

For Resources and Further Reading: CDC,14 the Fenway Institute’s National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center,15 and US Department of Health and Human Services.16

Dr. Chiang and Dr. Chedid are both in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Chedid is also with the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic. Neither of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest. They are on X, formerly Twitter: @dr_davidchiang , @VictorChedidMD .

CITATIONS

1. Mahadevan U et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: A report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

2. Pires F et al. A survey on the impact of IBD in sexual health: Into intimacy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32279.

3. Mules TC et al. The impact of disease activity on sexual and erectile dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1244-54.

4. Duong N et al. Overcoming disparities for sexual and gender minority patients and providers in gastroenterology and hepatology: Introduction to Rainbows in Gastro. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:299-301.

5. Newman KL et al. A systematic review of inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and health outcomes in sexual and gender minority individuals. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:866-71.

6. Newman KL et al. Research considerations in Digestive and liver disease in transgender and gender-diverse populations. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:523-28 e1.

7. Velez C et al. Digestive health in sexual and gender minority populations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:865-75.

8. Medicine Io. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2011.

9. Austin EL. Sexual orientation disclosure to health care providers among urban and non-urban southern lesbians. Women Health. 2013;53:41-55.

10. Oladeru OT et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities in transgender people. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:116-21.

11. Vinsard DG et al. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on anoreceptive intercourse in sexual and gender minorities with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Digestive Disease Week (DDW). Chicago, IL, 2023.

12. Ghusn W et al. Social determinants of health in LGBTQIA+ patients with inflammatory bowel disease. American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Charlotte, NC, 2022.

13. Grasman ME et al. Neovaginal sparing in a transgender woman with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e73-4.

14. Prevention CfDCa. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health — https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm.

15. Institute TF. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center — https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/.

16. Services UDoHaH. LGBTQI+ Resources — https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbtqi/resources/index.html.

Cases

Patient 1: 55-year-old cis-male, who identifies as gay, has ulcerative colitis that has been refractory to multiple biologic therapies. His provider recommends a total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (TPC with IPAA), but the patient has questions regarding sexual function following surgery. Specifically, he is wondering when, or if, he can resume receptive anal intercourse. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: 25-year-old, trans-female, status-post vaginoplasty with use of sigmoid colon and with well-controlled ulcerative colitis, presents with vaginal discharge, weight loss, and rectal bleeding. How do you explain what has happened to her? During your discussion, she also asks you why her chart continues to use her “dead name.” How do you respond?

Patient 3: 32-year-old, cis-female, G2P2, who identifies as a lesbian, has active ulcerative colitis. She wants to discuss medical or surgical therapy and future pregnancies. How would you counsel her?

Many gastroenterologists would likely know how to address patient 3’s concerns, but the concerns of patients 1 and 2 often go unaddressed or dismissed. Numerous studies and surveys have been conducted on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but the focus of these studies has always been through a heteronormative cisgender lens. The focus of many studies is on fertility or sexual health and function in cisgender, heteronormative individuals.1-3 In the last few years, however, there has been increasing awareness of the health disparities, stigma, and discrimination that sexual and gender minorities (SGM) experience.4-6 For the purposes of this discussion, individuals within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community will be referred to as SGM. We recognize that even this exhaustive listing above does not acknowledge the full spectrum of diversity within the SGM community.

Clinical Care/Competency for SGM with IBD is Lacking

Almost 10% of the US population identifies as some form of SGM, and that number can be higher within the younger generations.4 SGM patients tend to delay or avoid seeking health care due to concern for provider mistreatment or lack of regard for their individual concerns. Additionally, there are several gaps in clinical knowledge about caring for SGM individuals. Little is known regarding the incidence or prevalence of IBD in SGM populations, but it is perceived to be similar to cisgender heterosexual individuals. Furthermore, as Newman et al. highlighted in their systematic review published in May 2023, there is a lack of guidance regarding sexual activity in the setting of IBD in SGM individuals.5 There is also a significant lack of knowledge on the impact of gender-affirming care on the natural history and treatments of IBD in transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals. This can impact providers’ comfort and competence in caring for TGNC individuals.

Another important point to make is that the SGM community still faces discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity to this day, which impacts the quality and delivery of their care.7 Culturally-competent care should include care that is free from stigma, implicit and explicit biases, and discrimination. In 2011, an Institute of Medicine report documented, among other issues, provider discomfort in delivering care to SGM patients.8 While SGM individuals prefer a provider who acknowledges their sexual orientation and gender identity and treats them with the dignity and respect they deserve, many SGM individuals share valid concerns regarding their safety, which impact their desire to disclose their identity to health care providers.9 This certainly can have an impact on the quality of care they receive, including important health maintenance milestones and cancer screenings.10

An internal survey at our institution of providers (nurses, physician assistants, surgeons, and physicians) found that among 85 responders, 70% have cared for SGM who have undergone TPC with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). Of these, 75% did not ask about sexual orientation or practices before pouch formation (though almost all of them agreed it would be important to ask). A total of 55% were comfortable in discussing SGM-related concerns; 53% did not feel comfortable discussing sexual orientation or practices; and in particular when it came to anoreceptive intercourse (ARI), 73% did not feel confident discussing recommendations.11

All of these issues highlight the importance of developing curricula that focus on reducing implicit and explicit biases towards SGM individuals and increasing the competence of providers to take care of SGM individuals in a safe space.

Additionally, it further justifies the need for ethical research that focuses on the needs of SGM individuals to guide evidence-based approaches to care. Given the implicit and explicit heterosexism and transphobia in society and many health care systems, Rainbows in Gastro was formed as an advocacy group for SGM patients, trainees, and staff in gastroenterology and hepatology.4

Research in SGM and IBD is lacking

There are additional needs for research in IBD and how it pertains to the needs of SGM individuals. Figure 1 highlights the lack of PubMed results for the search terms “IBD + LGBT,” “IBD + LGBTQ,” or “IBD + queer.” In contrast, the search terms “IBD + fertility” and “IBD + sexual dysfunction” generate many results. Even a systemic review conducted by Newman et al. of multiple databases in 2022 found only seven articles that demonstrated appropriately performed studies on SGM patients with IBD.5 This highlights the significant dearth of research in the realm of SGM health in IBD.

Newman and colleagues have recently published research considerations for SGM individuals. They highlighted the need to include understanding the “unique combination of psychosocial, biomedical, and legal experiences” that results in different needs and outcomes. There were several areas identified, including minority stress, which comes from existence of being SGM, especially as transgender individuals face increasing legal challenges in a variety of settings, not just healthcare.6 In a retrospective chart review investigating social determinants of health in SGM-IBD populations,12 36% of patients reported some level of social isolation, and almost 50% reported some level of stress. A total of 40% of them self-reported some perceived level of risk with respect to employment, and 17% reported depression. Given that this was a chart review and not a strict questionnaire, this study was certainly limited, and we would hypothesize that these numbers are therefore underestimating the true proportion of SGM-IBD patients who deal with employment concerns, social isolation, or psychological distress.

What Next? Back to the Patients

Circling back to our patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them? In patient 1’s case, we would inform him that pelvic surgery can increase the risk for sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction. He additionally would be advised during a staged TPC with IPAA, he may experience issues with body image. However, should he desire to participate in receptive anal intercourse after completion of his surgeries, the general recommendation would be to wait at least 6 months and with proven remission. It should further be noted that these are not formalized recommendations, only highlighting the need for more research and consensus on standards of care for SGM patients. He should finally be told that because he has ulcerative colitis, removal of the colon does not remove the risk for future intestinal involvement such as possible pouchitis.

In patient 2’s case, she is likely experiencing diversion vaginitis related to use of her colon for her neo-vagina. She should undergo colonoscopy and vaginoscopy in addition to standard work-up for her known ulcerative colitis.13 Management should be done in a multidisciplinary approach between the IBD provider, gynecologist, and gender-affirming provider. The electronic medical record should be updated to reflect the patient’s preferred name, pronouns, and gender identity, and her medical records, including automated clinical reports, should be updated accordingly.

As for patient 3, she would be counseled according to well-documented guidelines on pregnancy and IBD, including risks of medications (such as Jak inhibitors or methotrexate) versus the risk of uncontrolled IBD during pregnancy.1

Regardless of a patient’s gender identity or sexual orientation, patient-centered, culturally competent, and sensitive care should be provided. At Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we started one of the first Pride in IBD Clinics, which focuses on the care of SGM individuals with IBD. Our focus is to address the needs of patients who belong to the SGM community in a wholistic approach within a safe space (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYa_zYaCA6M; https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/inflammatory-bowel-disease-clinic/overview/ovc-20357763). Our process of developing the clinic included training all staff on proper communication and cultural sensitivity for the SGM community.

Furthermore, providing welcoming and affirming signs of inclusivity for SGM individuals at the provider’s office — including but not limited to rainbow progressive flags, gender-neutral bathroom signs, or pronoun pins on provider identification badges (see Figure 2) — are usually appreciated by patients. Ensuring that patient education materials do not assume gender (for example, using the term “parents” rather than “mother and father”) and using gender neutral terms on intake forms is very important. Inclusive communication includes providers introducing themselves by preferred name and pronouns, asking the patients to introduce themselves, and welcoming them to share their pronouns. These simple actions can provide an atmosphere of safety for SGM patients, which would serve to enhance the quality of care we can provide for them.

For Resources and Further Reading: CDC,14 the Fenway Institute’s National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center,15 and US Department of Health and Human Services.16

Dr. Chiang and Dr. Chedid are both in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Chedid is also with the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic. Neither of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest. They are on X, formerly Twitter: @dr_davidchiang , @VictorChedidMD .

CITATIONS

1. Mahadevan U et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: A report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

2. Pires F et al. A survey on the impact of IBD in sexual health: Into intimacy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32279.

3. Mules TC et al. The impact of disease activity on sexual and erectile dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1244-54.

4. Duong N et al. Overcoming disparities for sexual and gender minority patients and providers in gastroenterology and hepatology: Introduction to Rainbows in Gastro. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:299-301.

5. Newman KL et al. A systematic review of inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and health outcomes in sexual and gender minority individuals. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:866-71.

6. Newman KL et al. Research considerations in Digestive and liver disease in transgender and gender-diverse populations. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:523-28 e1.

7. Velez C et al. Digestive health in sexual and gender minority populations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:865-75.

8. Medicine Io. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2011.

9. Austin EL. Sexual orientation disclosure to health care providers among urban and non-urban southern lesbians. Women Health. 2013;53:41-55.

10. Oladeru OT et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities in transgender people. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:116-21.

11. Vinsard DG et al. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on anoreceptive intercourse in sexual and gender minorities with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Digestive Disease Week (DDW). Chicago, IL, 2023.

12. Ghusn W et al. Social determinants of health in LGBTQIA+ patients with inflammatory bowel disease. American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Charlotte, NC, 2022.

13. Grasman ME et al. Neovaginal sparing in a transgender woman with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e73-4.

14. Prevention CfDCa. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health — https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm.

15. Institute TF. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center — https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/.

16. Services UDoHaH. LGBTQI+ Resources — https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbtqi/resources/index.html.

Cases

Patient 1: 55-year-old cis-male, who identifies as gay, has ulcerative colitis that has been refractory to multiple biologic therapies. His provider recommends a total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (TPC with IPAA), but the patient has questions regarding sexual function following surgery. Specifically, he is wondering when, or if, he can resume receptive anal intercourse. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: 25-year-old, trans-female, status-post vaginoplasty with use of sigmoid colon and with well-controlled ulcerative colitis, presents with vaginal discharge, weight loss, and rectal bleeding. How do you explain what has happened to her? During your discussion, she also asks you why her chart continues to use her “dead name.” How do you respond?

Patient 3: 32-year-old, cis-female, G2P2, who identifies as a lesbian, has active ulcerative colitis. She wants to discuss medical or surgical therapy and future pregnancies. How would you counsel her?

Many gastroenterologists would likely know how to address patient 3’s concerns, but the concerns of patients 1 and 2 often go unaddressed or dismissed. Numerous studies and surveys have been conducted on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but the focus of these studies has always been through a heteronormative cisgender lens. The focus of many studies is on fertility or sexual health and function in cisgender, heteronormative individuals.1-3 In the last few years, however, there has been increasing awareness of the health disparities, stigma, and discrimination that sexual and gender minorities (SGM) experience.4-6 For the purposes of this discussion, individuals within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community will be referred to as SGM. We recognize that even this exhaustive listing above does not acknowledge the full spectrum of diversity within the SGM community.

Clinical Care/Competency for SGM with IBD is Lacking

Almost 10% of the US population identifies as some form of SGM, and that number can be higher within the younger generations.4 SGM patients tend to delay or avoid seeking health care due to concern for provider mistreatment or lack of regard for their individual concerns. Additionally, there are several gaps in clinical knowledge about caring for SGM individuals. Little is known regarding the incidence or prevalence of IBD in SGM populations, but it is perceived to be similar to cisgender heterosexual individuals. Furthermore, as Newman et al. highlighted in their systematic review published in May 2023, there is a lack of guidance regarding sexual activity in the setting of IBD in SGM individuals.5 There is also a significant lack of knowledge on the impact of gender-affirming care on the natural history and treatments of IBD in transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals. This can impact providers’ comfort and competence in caring for TGNC individuals.

Another important point to make is that the SGM community still faces discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity to this day, which impacts the quality and delivery of their care.7 Culturally-competent care should include care that is free from stigma, implicit and explicit biases, and discrimination. In 2011, an Institute of Medicine report documented, among other issues, provider discomfort in delivering care to SGM patients.8 While SGM individuals prefer a provider who acknowledges their sexual orientation and gender identity and treats them with the dignity and respect they deserve, many SGM individuals share valid concerns regarding their safety, which impact their desire to disclose their identity to health care providers.9 This certainly can have an impact on the quality of care they receive, including important health maintenance milestones and cancer screenings.10

An internal survey at our institution of providers (nurses, physician assistants, surgeons, and physicians) found that among 85 responders, 70% have cared for SGM who have undergone TPC with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). Of these, 75% did not ask about sexual orientation or practices before pouch formation (though almost all of them agreed it would be important to ask). A total of 55% were comfortable in discussing SGM-related concerns; 53% did not feel comfortable discussing sexual orientation or practices; and in particular when it came to anoreceptive intercourse (ARI), 73% did not feel confident discussing recommendations.11

All of these issues highlight the importance of developing curricula that focus on reducing implicit and explicit biases towards SGM individuals and increasing the competence of providers to take care of SGM individuals in a safe space.

Additionally, it further justifies the need for ethical research that focuses on the needs of SGM individuals to guide evidence-based approaches to care. Given the implicit and explicit heterosexism and transphobia in society and many health care systems, Rainbows in Gastro was formed as an advocacy group for SGM patients, trainees, and staff in gastroenterology and hepatology.4

Research in SGM and IBD is lacking

There are additional needs for research in IBD and how it pertains to the needs of SGM individuals. Figure 1 highlights the lack of PubMed results for the search terms “IBD + LGBT,” “IBD + LGBTQ,” or “IBD + queer.” In contrast, the search terms “IBD + fertility” and “IBD + sexual dysfunction” generate many results. Even a systemic review conducted by Newman et al. of multiple databases in 2022 found only seven articles that demonstrated appropriately performed studies on SGM patients with IBD.5 This highlights the significant dearth of research in the realm of SGM health in IBD.

Newman and colleagues have recently published research considerations for SGM individuals. They highlighted the need to include understanding the “unique combination of psychosocial, biomedical, and legal experiences” that results in different needs and outcomes. There were several areas identified, including minority stress, which comes from existence of being SGM, especially as transgender individuals face increasing legal challenges in a variety of settings, not just healthcare.6 In a retrospective chart review investigating social determinants of health in SGM-IBD populations,12 36% of patients reported some level of social isolation, and almost 50% reported some level of stress. A total of 40% of them self-reported some perceived level of risk with respect to employment, and 17% reported depression. Given that this was a chart review and not a strict questionnaire, this study was certainly limited, and we would hypothesize that these numbers are therefore underestimating the true proportion of SGM-IBD patients who deal with employment concerns, social isolation, or psychological distress.

What Next? Back to the Patients

Circling back to our patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them? In patient 1’s case, we would inform him that pelvic surgery can increase the risk for sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction. He additionally would be advised during a staged TPC with IPAA, he may experience issues with body image. However, should he desire to participate in receptive anal intercourse after completion of his surgeries, the general recommendation would be to wait at least 6 months and with proven remission. It should further be noted that these are not formalized recommendations, only highlighting the need for more research and consensus on standards of care for SGM patients. He should finally be told that because he has ulcerative colitis, removal of the colon does not remove the risk for future intestinal involvement such as possible pouchitis.

In patient 2’s case, she is likely experiencing diversion vaginitis related to use of her colon for her neo-vagina. She should undergo colonoscopy and vaginoscopy in addition to standard work-up for her known ulcerative colitis.13 Management should be done in a multidisciplinary approach between the IBD provider, gynecologist, and gender-affirming provider. The electronic medical record should be updated to reflect the patient’s preferred name, pronouns, and gender identity, and her medical records, including automated clinical reports, should be updated accordingly.

As for patient 3, she would be counseled according to well-documented guidelines on pregnancy and IBD, including risks of medications (such as Jak inhibitors or methotrexate) versus the risk of uncontrolled IBD during pregnancy.1

Regardless of a patient’s gender identity or sexual orientation, patient-centered, culturally competent, and sensitive care should be provided. At Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we started one of the first Pride in IBD Clinics, which focuses on the care of SGM individuals with IBD. Our focus is to address the needs of patients who belong to the SGM community in a wholistic approach within a safe space (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYa_zYaCA6M; https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/inflammatory-bowel-disease-clinic/overview/ovc-20357763). Our process of developing the clinic included training all staff on proper communication and cultural sensitivity for the SGM community.

Furthermore, providing welcoming and affirming signs of inclusivity for SGM individuals at the provider’s office — including but not limited to rainbow progressive flags, gender-neutral bathroom signs, or pronoun pins on provider identification badges (see Figure 2) — are usually appreciated by patients. Ensuring that patient education materials do not assume gender (for example, using the term “parents” rather than “mother and father”) and using gender neutral terms on intake forms is very important. Inclusive communication includes providers introducing themselves by preferred name and pronouns, asking the patients to introduce themselves, and welcoming them to share their pronouns. These simple actions can provide an atmosphere of safety for SGM patients, which would serve to enhance the quality of care we can provide for them.

For Resources and Further Reading: CDC,14 the Fenway Institute’s National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center,15 and US Department of Health and Human Services.16

Dr. Chiang and Dr. Chedid are both in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Chedid is also with the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic. Neither of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest. They are on X, formerly Twitter: @dr_davidchiang , @VictorChedidMD .

CITATIONS

1. Mahadevan U et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: A report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

2. Pires F et al. A survey on the impact of IBD in sexual health: Into intimacy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32279.

3. Mules TC et al. The impact of disease activity on sexual and erectile dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1244-54.

4. Duong N et al. Overcoming disparities for sexual and gender minority patients and providers in gastroenterology and hepatology: Introduction to Rainbows in Gastro. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:299-301.

5. Newman KL et al. A systematic review of inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and health outcomes in sexual and gender minority individuals. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:866-71.

6. Newman KL et al. Research considerations in Digestive and liver disease in transgender and gender-diverse populations. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:523-28 e1.

7. Velez C et al. Digestive health in sexual and gender minority populations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:865-75.

8. Medicine Io. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2011.

9. Austin EL. Sexual orientation disclosure to health care providers among urban and non-urban southern lesbians. Women Health. 2013;53:41-55.

10. Oladeru OT et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities in transgender people. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:116-21.

11. Vinsard DG et al. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on anoreceptive intercourse in sexual and gender minorities with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Digestive Disease Week (DDW). Chicago, IL, 2023.

12. Ghusn W et al. Social determinants of health in LGBTQIA+ patients with inflammatory bowel disease. American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Charlotte, NC, 2022.

13. Grasman ME et al. Neovaginal sparing in a transgender woman with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e73-4.

14. Prevention CfDCa. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health — https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm.

15. Institute TF. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center — https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/.

16. Services UDoHaH. LGBTQI+ Resources — https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbtqi/resources/index.html.

One-year anniversary

Dear Friends,

It’s been a year since I have become editor-in-chief of The New Gastroenterologist and I am so grateful for our readers and contributors. Thank you for being a part of the TNG family. , including the increasing armamentarium of inflammatory bowel disease treatments, taking on leadership roles in diversity, equity, and inclusion, and tackling financial planning.

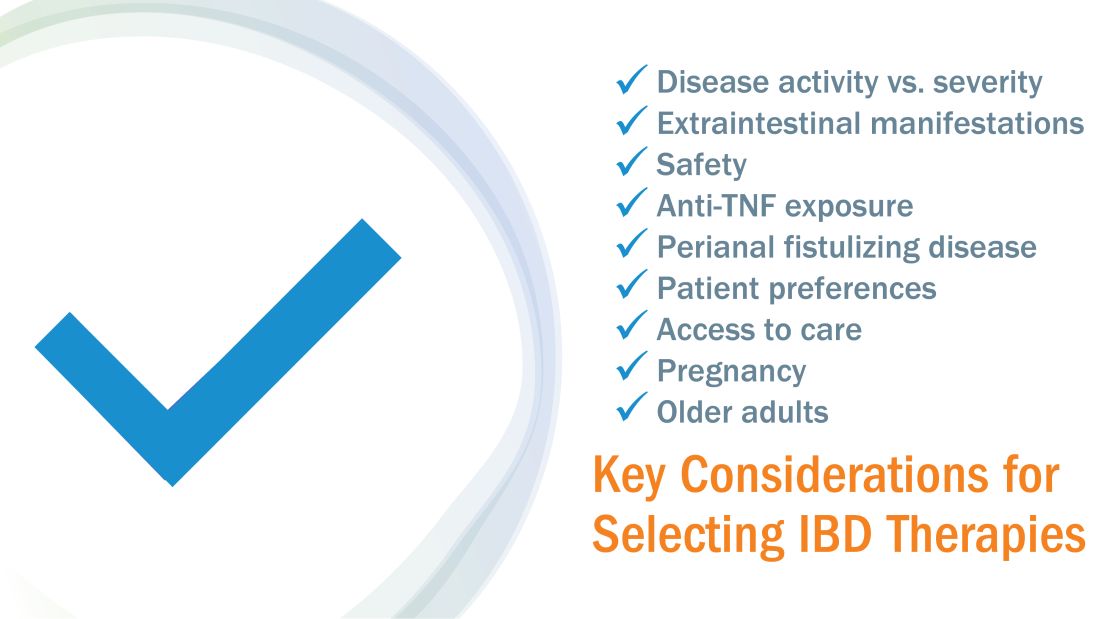

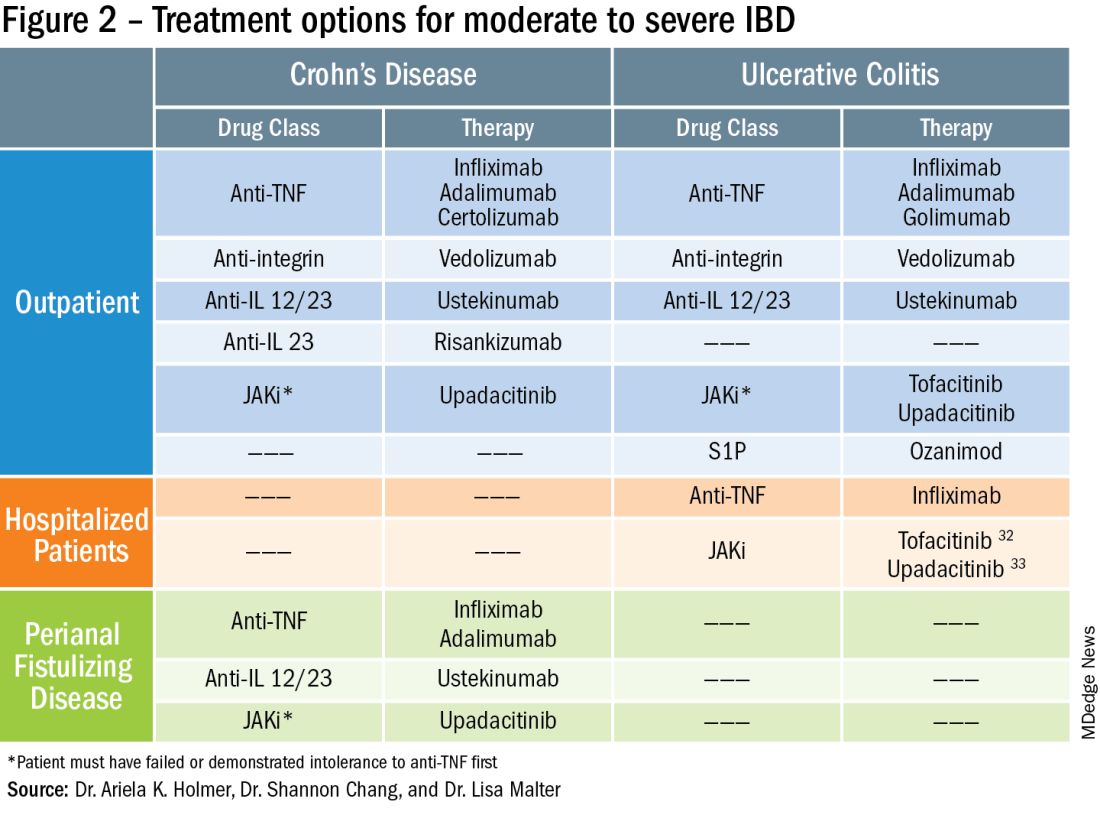

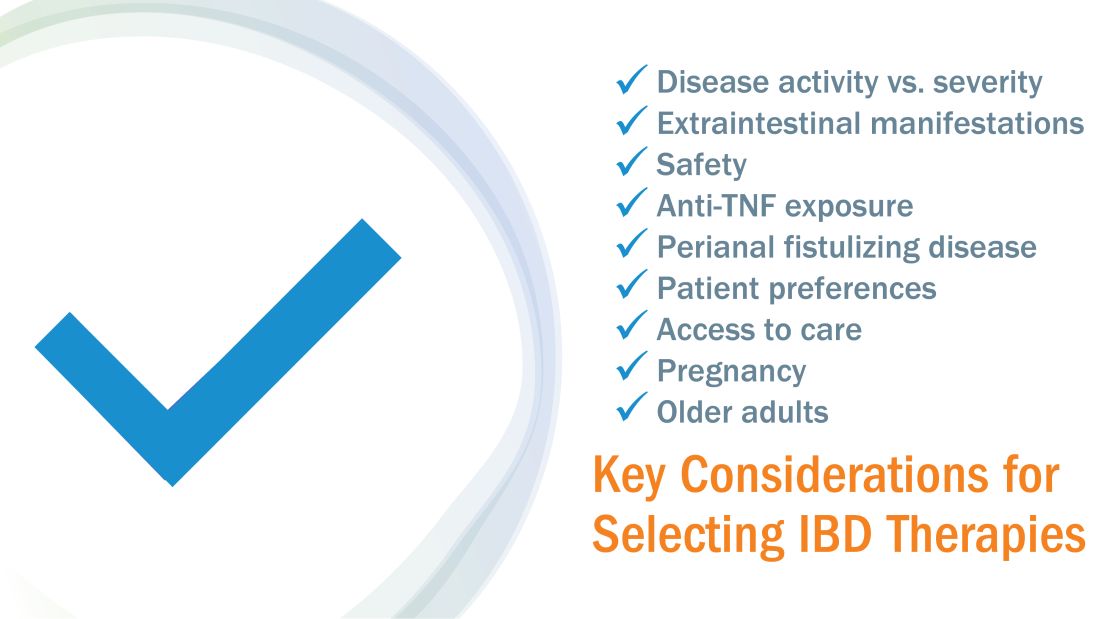

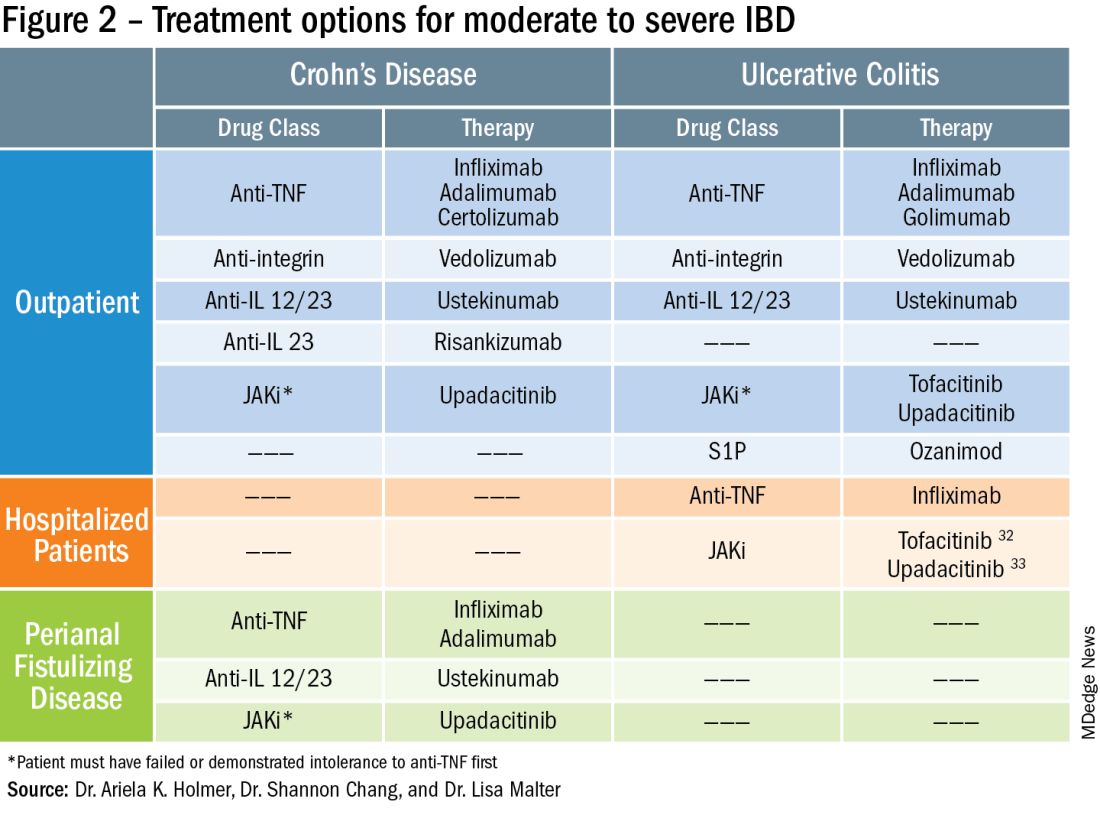

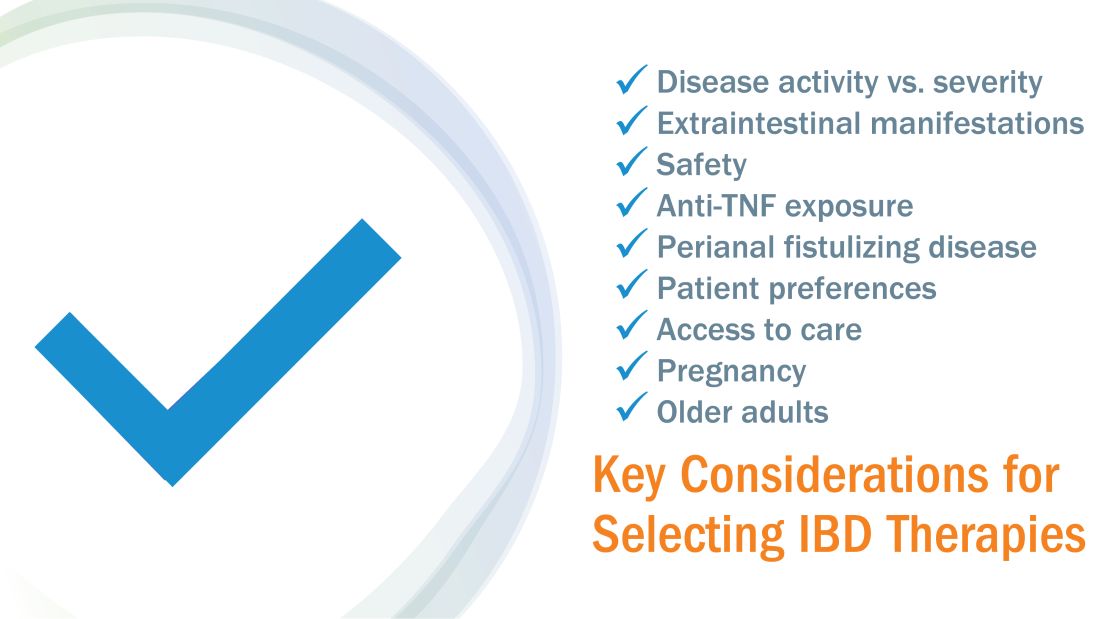

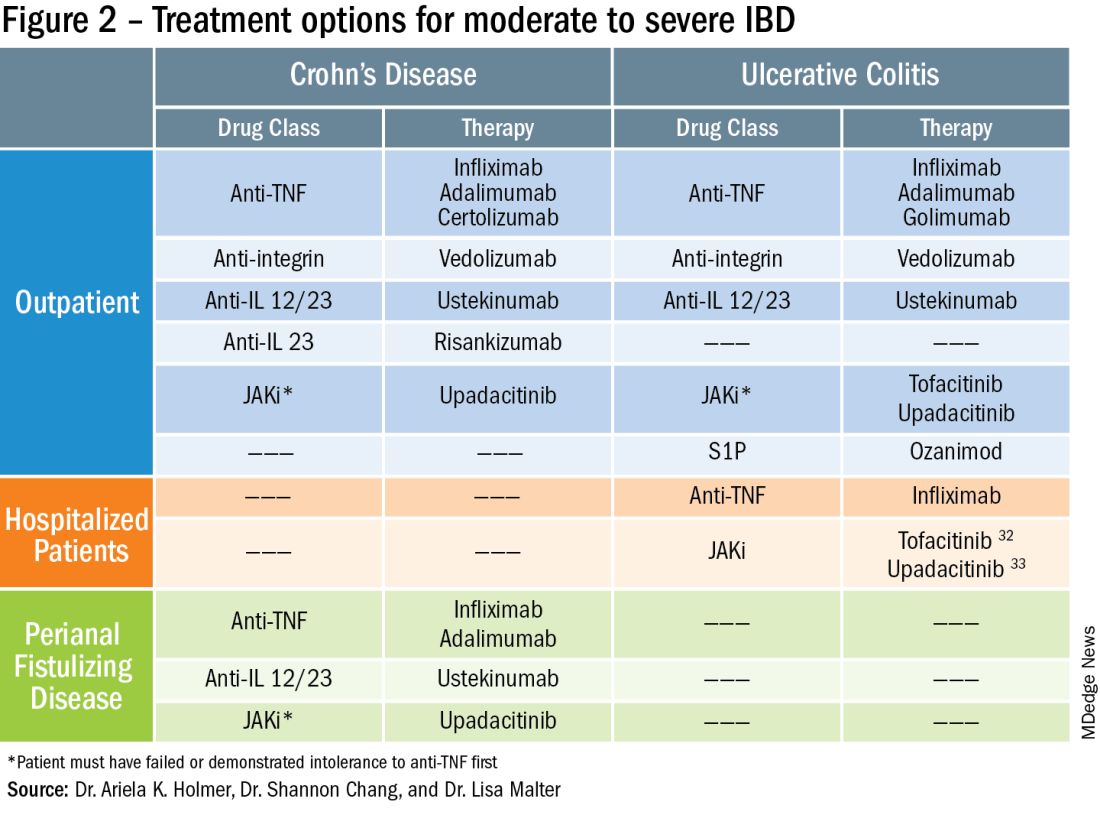

In this issue’s In Focus, Drs. Ariela K. Holmer, Shannon Chang, and Lisa Malter break down the factors that contribute to selecting therapies for moderate to severe IBD, such as disease activity and severity, extraintestinal manifestations, safety, prior anti–tumor necrosis factor exposure, perianal disease, and patient preference.

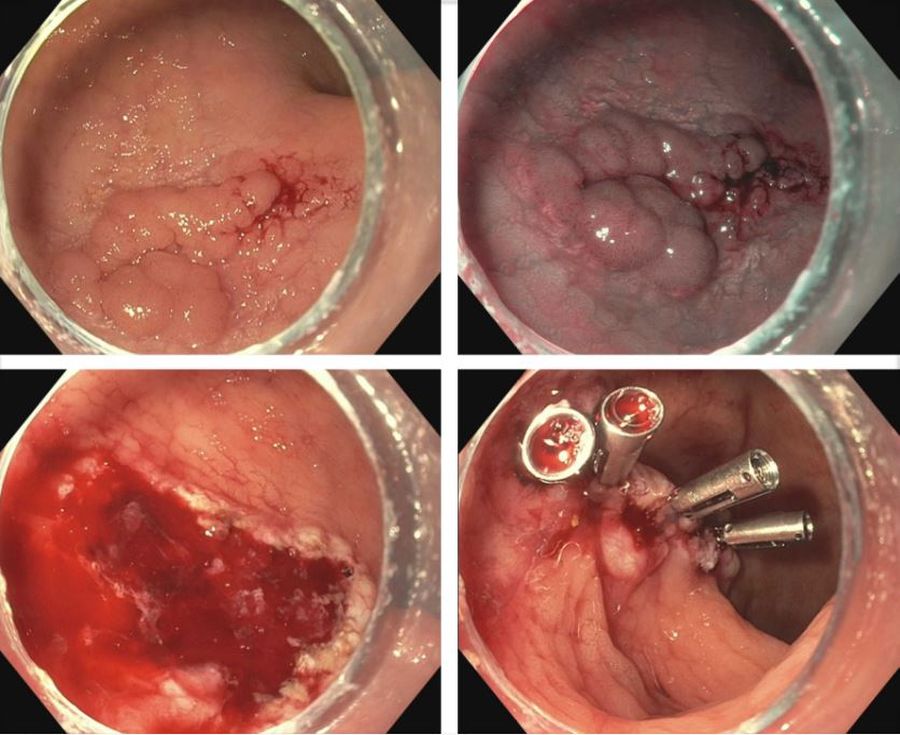

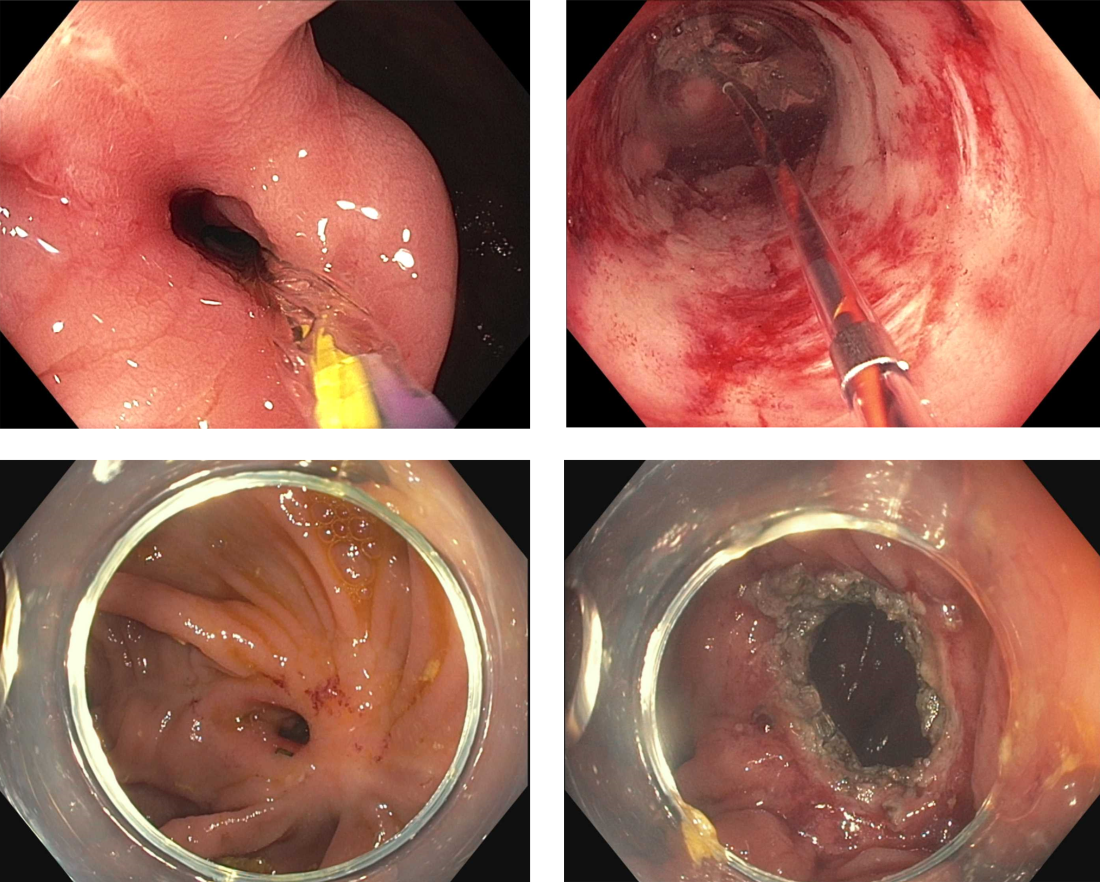

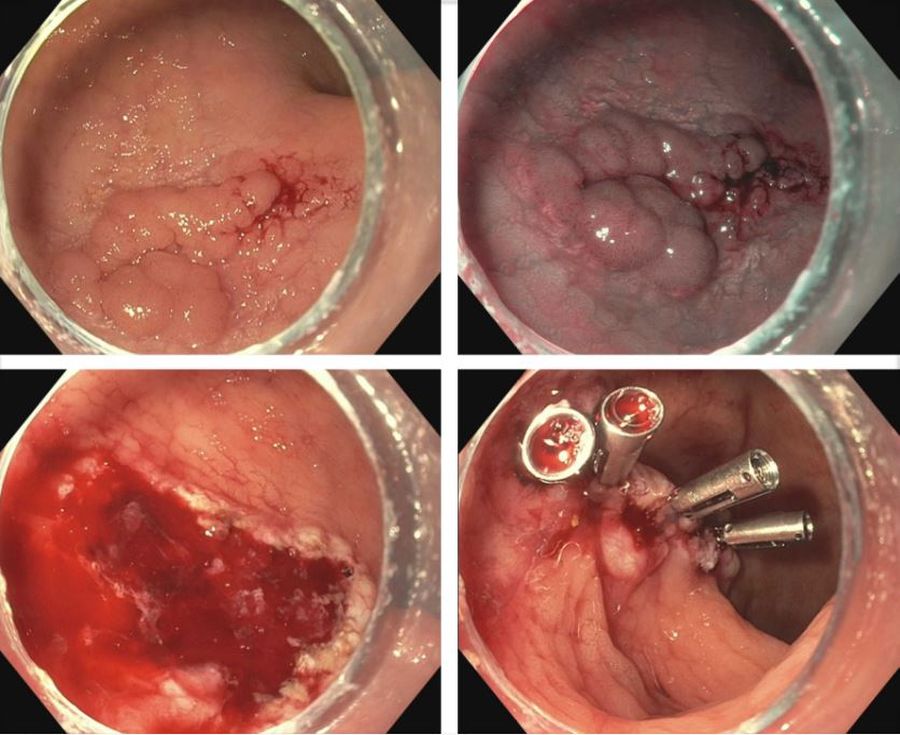

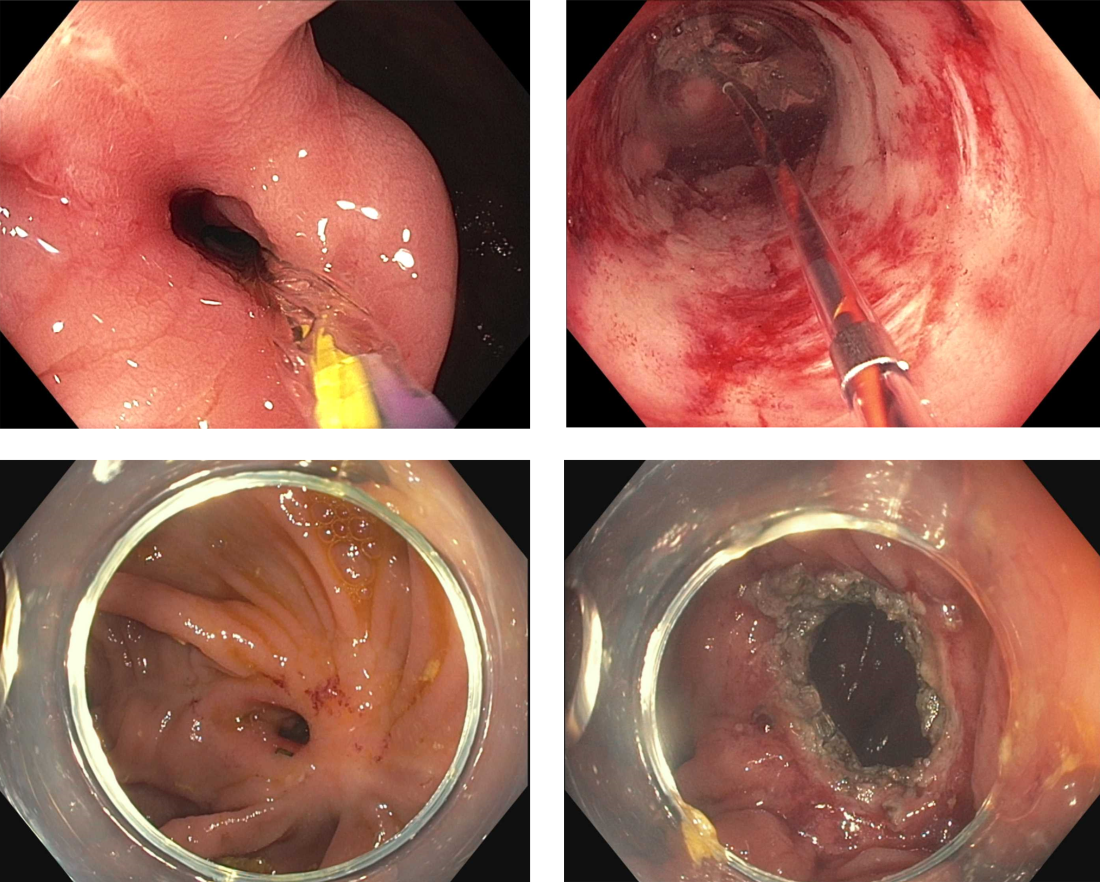

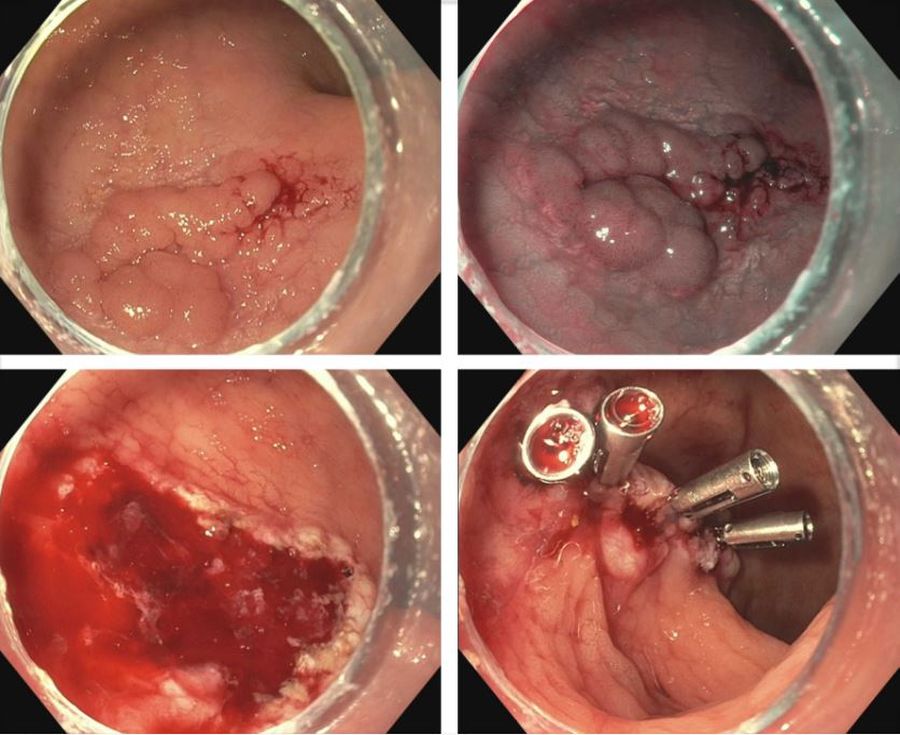

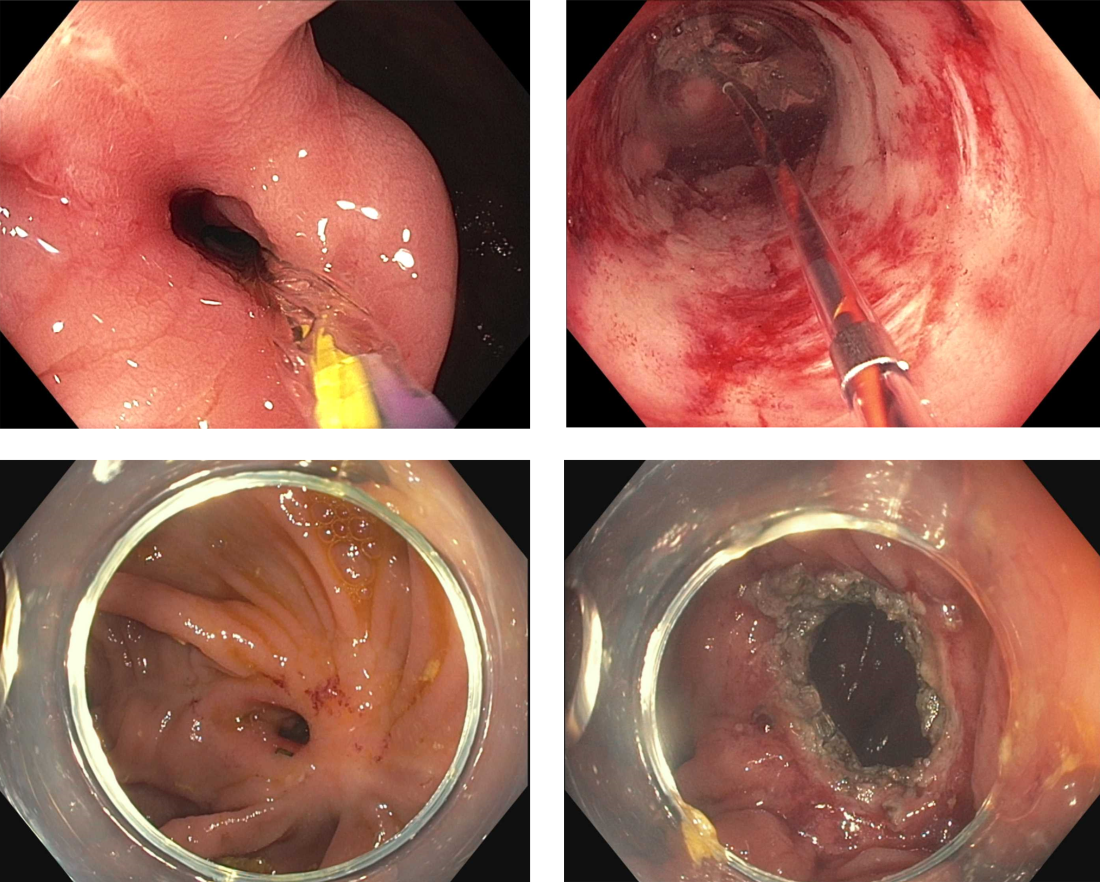

Drs. Michael G. Rubeiz, Kemmian D. Johnson, and Juan Reyes Genere continue our journey with IBD in the Short Clinical Review section, describing advances in endoscopic therapies in IBD. They review the resection of colitis dysplasia and management of luminal strictures with dilation and stricturotomy.

Early-career faculty are being requested to spearhead diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts at their institutions or for their groups. Drs. Cassandra D.L. Fritz and Nicolette Juliana Rodriguez highlight important aspects that should be considered prior to taking on DEI roles.

In the Finance section, Dr. Animesh Jain answers five common questions for young gastroenterologists. He addresses student loans, disability insurance, life insurance, retirement, and buying a first house.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first biologic therapy for IBD, infliximab, was only approved 25 years ago in 1998.

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

It’s been a year since I have become editor-in-chief of The New Gastroenterologist and I am so grateful for our readers and contributors. Thank you for being a part of the TNG family. , including the increasing armamentarium of inflammatory bowel disease treatments, taking on leadership roles in diversity, equity, and inclusion, and tackling financial planning.

In this issue’s In Focus, Drs. Ariela K. Holmer, Shannon Chang, and Lisa Malter break down the factors that contribute to selecting therapies for moderate to severe IBD, such as disease activity and severity, extraintestinal manifestations, safety, prior anti–tumor necrosis factor exposure, perianal disease, and patient preference.

Drs. Michael G. Rubeiz, Kemmian D. Johnson, and Juan Reyes Genere continue our journey with IBD in the Short Clinical Review section, describing advances in endoscopic therapies in IBD. They review the resection of colitis dysplasia and management of luminal strictures with dilation and stricturotomy.

Early-career faculty are being requested to spearhead diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts at their institutions or for their groups. Drs. Cassandra D.L. Fritz and Nicolette Juliana Rodriguez highlight important aspects that should be considered prior to taking on DEI roles.

In the Finance section, Dr. Animesh Jain answers five common questions for young gastroenterologists. He addresses student loans, disability insurance, life insurance, retirement, and buying a first house.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first biologic therapy for IBD, infliximab, was only approved 25 years ago in 1998.

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

It’s been a year since I have become editor-in-chief of The New Gastroenterologist and I am so grateful for our readers and contributors. Thank you for being a part of the TNG family. , including the increasing armamentarium of inflammatory bowel disease treatments, taking on leadership roles in diversity, equity, and inclusion, and tackling financial planning.

In this issue’s In Focus, Drs. Ariela K. Holmer, Shannon Chang, and Lisa Malter break down the factors that contribute to selecting therapies for moderate to severe IBD, such as disease activity and severity, extraintestinal manifestations, safety, prior anti–tumor necrosis factor exposure, perianal disease, and patient preference.

Drs. Michael G. Rubeiz, Kemmian D. Johnson, and Juan Reyes Genere continue our journey with IBD in the Short Clinical Review section, describing advances in endoscopic therapies in IBD. They review the resection of colitis dysplasia and management of luminal strictures with dilation and stricturotomy.

Early-career faculty are being requested to spearhead diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts at their institutions or for their groups. Drs. Cassandra D.L. Fritz and Nicolette Juliana Rodriguez highlight important aspects that should be considered prior to taking on DEI roles.

In the Finance section, Dr. Animesh Jain answers five common questions for young gastroenterologists. He addresses student loans, disability insurance, life insurance, retirement, and buying a first house.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first biologic therapy for IBD, infliximab, was only approved 25 years ago in 1998.

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Resources to help new GI fellows thrive

The AGA Gastro Squad is excited you’re here and we’re here to help.

AGA has resources and programs specifically for fellows. Whether you’re embarking on your first year or your last one, these tools can be used at any point to help you during your training.

Start here:

Review and bookmark these guides to make the most out of fellowship.

10 tips for new GI fellows

First year fellows guide

Small talk, big topics

A podcast for trainees and early career GIs from fellow early career GIs. Join our hosts for conversations with leaders in gastroenterology. They offer guidance for training and dissect the changing landscape of GI and what it means for you. Check out recent episodes and download and subscribe wherever podcasts are available.

AGA university

Get your clinical questions answered or take a deeper dive into different topic areas with AGA University. Courses include Gastro Bites sessions about topics such as examining new guideline recommendations for managing chronic idiopathic constipation in adults. CME is available. Access AGA University here.

AGA young delegates program

Get plugged in with your fellow engaged early career GIs and learn about volunteer opportunities to represent AGA. The only criteria to participate is to be an AGA member. Join now.

Get more advice

Interested in receiving additional career guidance or professional development opportunities? Connect with the AGA Gastro Squad at @AmerGastroAssn on X and on Instagram.

The AGA Gastro Squad is excited you’re here and we’re here to help.

AGA has resources and programs specifically for fellows. Whether you’re embarking on your first year or your last one, these tools can be used at any point to help you during your training.

Start here:

Review and bookmark these guides to make the most out of fellowship.

10 tips for new GI fellows

First year fellows guide

Small talk, big topics

A podcast for trainees and early career GIs from fellow early career GIs. Join our hosts for conversations with leaders in gastroenterology. They offer guidance for training and dissect the changing landscape of GI and what it means for you. Check out recent episodes and download and subscribe wherever podcasts are available.

AGA university

Get your clinical questions answered or take a deeper dive into different topic areas with AGA University. Courses include Gastro Bites sessions about topics such as examining new guideline recommendations for managing chronic idiopathic constipation in adults. CME is available. Access AGA University here.

AGA young delegates program

Get plugged in with your fellow engaged early career GIs and learn about volunteer opportunities to represent AGA. The only criteria to participate is to be an AGA member. Join now.

Get more advice

Interested in receiving additional career guidance or professional development opportunities? Connect with the AGA Gastro Squad at @AmerGastroAssn on X and on Instagram.

The AGA Gastro Squad is excited you’re here and we’re here to help.

AGA has resources and programs specifically for fellows. Whether you’re embarking on your first year or your last one, these tools can be used at any point to help you during your training.

Start here:

Review and bookmark these guides to make the most out of fellowship.

10 tips for new GI fellows

First year fellows guide

Small talk, big topics

A podcast for trainees and early career GIs from fellow early career GIs. Join our hosts for conversations with leaders in gastroenterology. They offer guidance for training and dissect the changing landscape of GI and what it means for you. Check out recent episodes and download and subscribe wherever podcasts are available.

AGA university

Get your clinical questions answered or take a deeper dive into different topic areas with AGA University. Courses include Gastro Bites sessions about topics such as examining new guideline recommendations for managing chronic idiopathic constipation in adults. CME is available. Access AGA University here.

AGA young delegates program

Get plugged in with your fellow engaged early career GIs and learn about volunteer opportunities to represent AGA. The only criteria to participate is to be an AGA member. Join now.

Get more advice

Interested in receiving additional career guidance or professional development opportunities? Connect with the AGA Gastro Squad at @AmerGastroAssn on X and on Instagram.

Propel your academic research opportunities with AGA FORWARD

The FORWARD program supports and facilitates a unique pathway for physician-scientists from underrepresented populations to advance their careers and make a meaningful impact as leaders within AGA and in academic medicine. Here’s how the AGA FORWARD program creates a supportive environment that fosters career advancement, leadership development and a growing community:

- Learn important skills critical for a successful research career, expert grant writing training and coaching from esteemed GI mentors.

- Connect with a community of GI leaders through one-on-one mentorship and near-peer mentors in medicine from underrepresented populations.

- Develop leadership skills vital to directing your lab, your institution, the field, and AGA, partnering with an executive coach to assess, identify and work on key strengths and areas of improvement.

Embark on a transformative journey toward a successful and fulfilling career in academic medicine.

Apply today.

The FORWARD program supports and facilitates a unique pathway for physician-scientists from underrepresented populations to advance their careers and make a meaningful impact as leaders within AGA and in academic medicine. Here’s how the AGA FORWARD program creates a supportive environment that fosters career advancement, leadership development and a growing community:

- Learn important skills critical for a successful research career, expert grant writing training and coaching from esteemed GI mentors.

- Connect with a community of GI leaders through one-on-one mentorship and near-peer mentors in medicine from underrepresented populations.

- Develop leadership skills vital to directing your lab, your institution, the field, and AGA, partnering with an executive coach to assess, identify and work on key strengths and areas of improvement.

Embark on a transformative journey toward a successful and fulfilling career in academic medicine.

Apply today.

The FORWARD program supports and facilitates a unique pathway for physician-scientists from underrepresented populations to advance their careers and make a meaningful impact as leaders within AGA and in academic medicine. Here’s how the AGA FORWARD program creates a supportive environment that fosters career advancement, leadership development and a growing community:

- Learn important skills critical for a successful research career, expert grant writing training and coaching from esteemed GI mentors.

- Connect with a community of GI leaders through one-on-one mentorship and near-peer mentors in medicine from underrepresented populations.

- Develop leadership skills vital to directing your lab, your institution, the field, and AGA, partnering with an executive coach to assess, identify and work on key strengths and areas of improvement.

Embark on a transformative journey toward a successful and fulfilling career in academic medicine.

Apply today.

November 2023 - ICYMI

Gastroenterology

July

Newberry C et al. Enhancing Nutrition and Obesity Education in GI Fellowship Through Universal Curriculum Development. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):16-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.004. Epub 2023 Apr 13. PMID: 37061170.

Han H et al. Macrophage-derived Osteopontin (SPP1) Protects From Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):201-17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.228. Epub 2023 Apr 5. PMID: 37028770.

Deepak P et al. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):11-15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.017. PMID: 37349061.

August

Guo L et al. Molecular Profiling Provides Clinical Insights Into Targeted and Immunotherapies as Well as Colorectal Cancer Prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):414-28.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.029. Epub 2023 May 3. PMID: 37146911.

Huang DQ et al. Fibrosis Progression Rate in Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Among People With Diabetes Versus People Without Diabetes: A Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):463-72.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.025. Epub 2023 Apr 29. PMID: 37127100.

Teoh AYB et al. EUS-Guided Choledocho-duodenostomy Using Lumen Apposing Stent Versus ERCP With Covered Metallic Stents in Patients With Unresectable Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (DRA-MBO Trial). Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):473-82.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.016. Epub 2023 Apr 28. PMID: 37121331.

September

Mehta RS et al. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use With Incident Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep;165(3):564-72.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.052. Epub 2023 Jun 12. PMID: 37315867; PMCID: PMC10527011.

Ballou S et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Bloating: Results From the Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep;165(3):647-55.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.049. Epub 2023 Jun 13. PMID: 37315866; PMCID: PMC10527500.

CGH

July

Chang JW et al. Development of a Practical Guide to Implement and Monitor Diet Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul;21(7):1690-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.006. Epub 2023 Mar 16. PMID: 36933603; PMCID: PMC10293042.

Siboni S et al. Improving the Diagnostic Yield of High-Resolution Esophageal Manometry for GERD: The “Straight Leg-Raise” International Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul;21(7):1761-70.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.008. Epub 2022 Oct 19. PMID: 36270615.

August

Wechsler EV et al. Up-Front Endoscopy Maximizes Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Satisfaction in Uninvestigated Dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2378-88.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.003. Epub 2023 Jan 13. PMID: 36646234; PMCID: PMC10542651.

Frederiks CN et al. Clinical Relevance of Random Biopsies From the Esophagogastric Junction After Complete Eradication of Barrett’s Esophagus is Low. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2260-9.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.11.012. Epub 2022 Nov 22. PMID: 36423874.

Rustgi SD et al. Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2178-82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.010. Epub 2023 Apr 19. PMID: 37086748; PMCID: PMC10526696.

September

Baroud S et al. A Protocolized Management of Walled-Off Necrosis (WON) Reduces Time to WON Resolution and Improves Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep;21(10):2543-50.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.029. Epub 2023 May 8. PMID: 37164115.

Arnim UV et al. Monitoring Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Routine Clinical Practice - International Expert Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep;21(10):2526-33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.018. Epub 2022 Dec 24. PMID: 36572109.

TIGE

Kaila V et al. Does the Absence of Contrast Passage Into the Duodenum During Intraoperative Cholangiogram Truly Predict Choledocholithiasis? Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tige.2023.05.002.

O’Keefe SJD et al. Early Enteral Feeding in Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial Between Gastric vs Distal Jejunal Feeding. Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tige.2023.06.002.

Gastro Hep Advances

Mukherjee S et al. Assessing ChatGPT’s ability to reply to queries regarding colon cancer screening based on Multi-Society Guidelines. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2023.07.008.

Lopes EW et al. Lochhead P. Improving the Consent Process with an Informed Consent Video Prior to Outpatient Colonoscopy. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2023.07.016.

Gastroenterology

July

Newberry C et al. Enhancing Nutrition and Obesity Education in GI Fellowship Through Universal Curriculum Development. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):16-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.004. Epub 2023 Apr 13. PMID: 37061170.

Han H et al. Macrophage-derived Osteopontin (SPP1) Protects From Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):201-17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.228. Epub 2023 Apr 5. PMID: 37028770.

Deepak P et al. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):11-15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.017. PMID: 37349061.

August

Guo L et al. Molecular Profiling Provides Clinical Insights Into Targeted and Immunotherapies as Well as Colorectal Cancer Prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):414-28.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.029. Epub 2023 May 3. PMID: 37146911.

Huang DQ et al. Fibrosis Progression Rate in Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Among People With Diabetes Versus People Without Diabetes: A Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):463-72.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.025. Epub 2023 Apr 29. PMID: 37127100.

Teoh AYB et al. EUS-Guided Choledocho-duodenostomy Using Lumen Apposing Stent Versus ERCP With Covered Metallic Stents in Patients With Unresectable Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (DRA-MBO Trial). Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):473-82.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.016. Epub 2023 Apr 28. PMID: 37121331.

September

Mehta RS et al. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use With Incident Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep;165(3):564-72.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.052. Epub 2023 Jun 12. PMID: 37315867; PMCID: PMC10527011.

Ballou S et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Bloating: Results From the Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep;165(3):647-55.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.049. Epub 2023 Jun 13. PMID: 37315866; PMCID: PMC10527500.

CGH

July

Chang JW et al. Development of a Practical Guide to Implement and Monitor Diet Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul;21(7):1690-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.006. Epub 2023 Mar 16. PMID: 36933603; PMCID: PMC10293042.

Siboni S et al. Improving the Diagnostic Yield of High-Resolution Esophageal Manometry for GERD: The “Straight Leg-Raise” International Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul;21(7):1761-70.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.008. Epub 2022 Oct 19. PMID: 36270615.

August

Wechsler EV et al. Up-Front Endoscopy Maximizes Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Satisfaction in Uninvestigated Dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2378-88.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.003. Epub 2023 Jan 13. PMID: 36646234; PMCID: PMC10542651.

Frederiks CN et al. Clinical Relevance of Random Biopsies From the Esophagogastric Junction After Complete Eradication of Barrett’s Esophagus is Low. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2260-9.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.11.012. Epub 2022 Nov 22. PMID: 36423874.

Rustgi SD et al. Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2178-82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.010. Epub 2023 Apr 19. PMID: 37086748; PMCID: PMC10526696.

September

Baroud S et al. A Protocolized Management of Walled-Off Necrosis (WON) Reduces Time to WON Resolution and Improves Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep;21(10):2543-50.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.029. Epub 2023 May 8. PMID: 37164115.

Arnim UV et al. Monitoring Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Routine Clinical Practice - International Expert Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep;21(10):2526-33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.018. Epub 2022 Dec 24. PMID: 36572109.

TIGE

Kaila V et al. Does the Absence of Contrast Passage Into the Duodenum During Intraoperative Cholangiogram Truly Predict Choledocholithiasis? Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tige.2023.05.002.

O’Keefe SJD et al. Early Enteral Feeding in Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial Between Gastric vs Distal Jejunal Feeding. Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tige.2023.06.002.

Gastro Hep Advances

Mukherjee S et al. Assessing ChatGPT’s ability to reply to queries regarding colon cancer screening based on Multi-Society Guidelines. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2023.07.008.

Lopes EW et al. Lochhead P. Improving the Consent Process with an Informed Consent Video Prior to Outpatient Colonoscopy. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2023.07.016.

Gastroenterology

July

Newberry C et al. Enhancing Nutrition and Obesity Education in GI Fellowship Through Universal Curriculum Development. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):16-19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.004. Epub 2023 Apr 13. PMID: 37061170.

Han H et al. Macrophage-derived Osteopontin (SPP1) Protects From Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):201-17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.228. Epub 2023 Apr 5. PMID: 37028770.

Deepak P et al. Health Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care Driven by Rural Versus Urban Residence: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jul;165(1):11-15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.017. PMID: 37349061.

August

Guo L et al. Molecular Profiling Provides Clinical Insights Into Targeted and Immunotherapies as Well as Colorectal Cancer Prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):414-28.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.029. Epub 2023 May 3. PMID: 37146911.

Huang DQ et al. Fibrosis Progression Rate in Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Among People With Diabetes Versus People Without Diabetes: A Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):463-72.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.025. Epub 2023 Apr 29. PMID: 37127100.

Teoh AYB et al. EUS-Guided Choledocho-duodenostomy Using Lumen Apposing Stent Versus ERCP With Covered Metallic Stents in Patients With Unresectable Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (DRA-MBO Trial). Gastroenterology. 2023 Aug;165(2):473-82.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.016. Epub 2023 Apr 28. PMID: 37121331.

September

Mehta RS et al. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use With Incident Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep;165(3):564-72.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.052. Epub 2023 Jun 12. PMID: 37315867; PMCID: PMC10527011.

Ballou S et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Bloating: Results From the Rome Foundation Global Epidemiology Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep;165(3):647-55.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.049. Epub 2023 Jun 13. PMID: 37315866; PMCID: PMC10527500.

CGH

July

Chang JW et al. Development of a Practical Guide to Implement and Monitor Diet Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul;21(7):1690-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.006. Epub 2023 Mar 16. PMID: 36933603; PMCID: PMC10293042.

Siboni S et al. Improving the Diagnostic Yield of High-Resolution Esophageal Manometry for GERD: The “Straight Leg-Raise” International Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul;21(7):1761-70.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.008. Epub 2022 Oct 19. PMID: 36270615.

August

Wechsler EV et al. Up-Front Endoscopy Maximizes Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Satisfaction in Uninvestigated Dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2378-88.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.003. Epub 2023 Jan 13. PMID: 36646234; PMCID: PMC10542651.

Frederiks CN et al. Clinical Relevance of Random Biopsies From the Esophagogastric Junction After Complete Eradication of Barrett’s Esophagus is Low. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2260-9.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.11.012. Epub 2022 Nov 22. PMID: 36423874.

Rustgi SD et al. Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;21(9):2178-82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.010. Epub 2023 Apr 19. PMID: 37086748; PMCID: PMC10526696.

September

Baroud S et al. A Protocolized Management of Walled-Off Necrosis (WON) Reduces Time to WON Resolution and Improves Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep;21(10):2543-50.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.029. Epub 2023 May 8. PMID: 37164115.

Arnim UV et al. Monitoring Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Routine Clinical Practice - International Expert Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep;21(10):2526-33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.018. Epub 2022 Dec 24. PMID: 36572109.

TIGE

Kaila V et al. Does the Absence of Contrast Passage Into the Duodenum During Intraoperative Cholangiogram Truly Predict Choledocholithiasis? Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tige.2023.05.002.

O’Keefe SJD et al. Early Enteral Feeding in Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial Between Gastric vs Distal Jejunal Feeding. Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tige.2023.06.002.

Gastro Hep Advances

Mukherjee S et al. Assessing ChatGPT’s ability to reply to queries regarding colon cancer screening based on Multi-Society Guidelines. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2023.07.008.

Lopes EW et al. Lochhead P. Improving the Consent Process with an Informed Consent Video Prior to Outpatient Colonoscopy. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2023.07.016.

Five personal finance questions for the young GI

While this article will get you started, these are complex topics, and each could warrant several standalone articles. I strongly encourage you to develop some basic understanding of personal finance through books, websites, and podcasts. If you can manage Barrett’s esophagus, Crohn’s, and cirrhosis, you can understand the basics of personal finance.

1. What should I do about my student loans? Go for public service loan forgiveness or pay them off?

The first step is knowing your debt burden, knowing your options, and developing a plan to pay off student loans. Public service loan forgiveness (PSLF) can be a good option in many situations. For borrowers staying in academic or other 501(c)(3) positions, PSLF is often an obvious move. Importantly, a fall 2022 statement by the U.S. Department of Education clarified that physicians working as contractors for nonprofit hospitals in California and Texas may now qualify for PSLF.1,2

For trainees debating an academic/501(c)(3) position vs. private practice, I would generally not advise making a career choice based purely on PSLF eligibility. However, borrowers with very high federal student loan burdens (e.g., debt to income ratio of > 2:1), or who are very close to the PSLF 10-year requirement may want to consider choosing a qualifying position for a few years to receive PSLF student loan forgiveness. Please see TNG’s 2020 article3 for a deeper discussion. Consultation with a company specializing in student loan advice for physicians may be well worth the upfront cost.

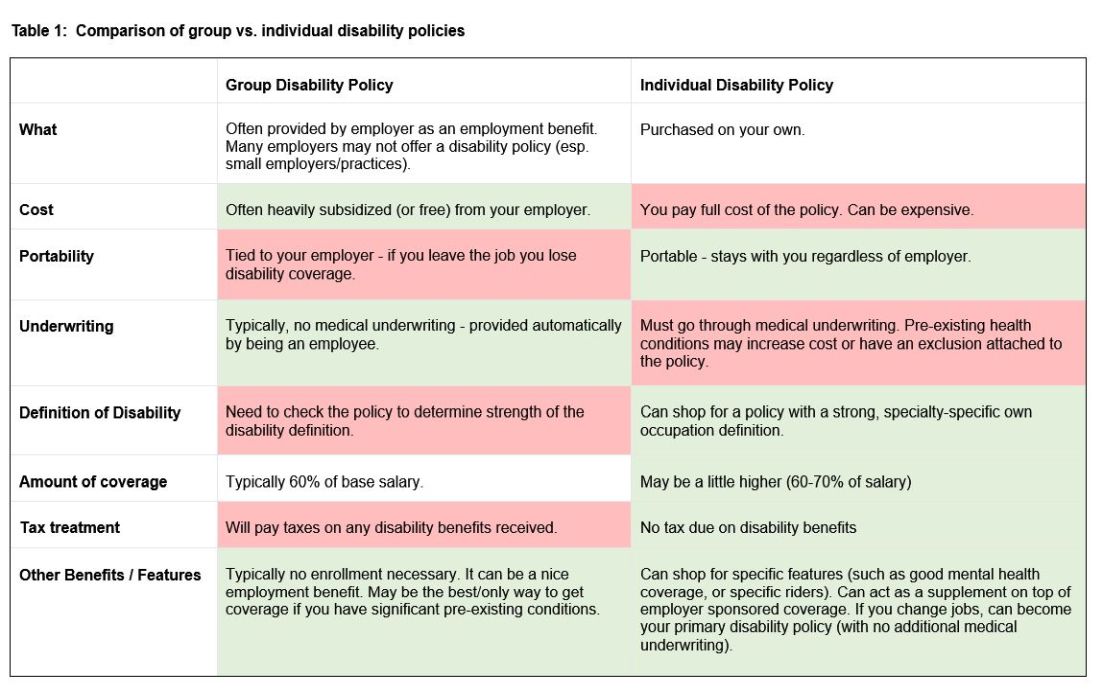

2. Do I need disability insurance? What should I look for?

I would strongly advise getting disability insurance as soon as possible (including while in training). While disability insurance is not cheap, it is one of the first steps you should take and one of the most important ways to protect your financial future. It is essential to look for a specialty-specific own occupation policy. Such a policy will provide disability payments if you are no longer able to work as a gastroenterologist/hepatologist (including an injury which prevents you from doing endoscopies).

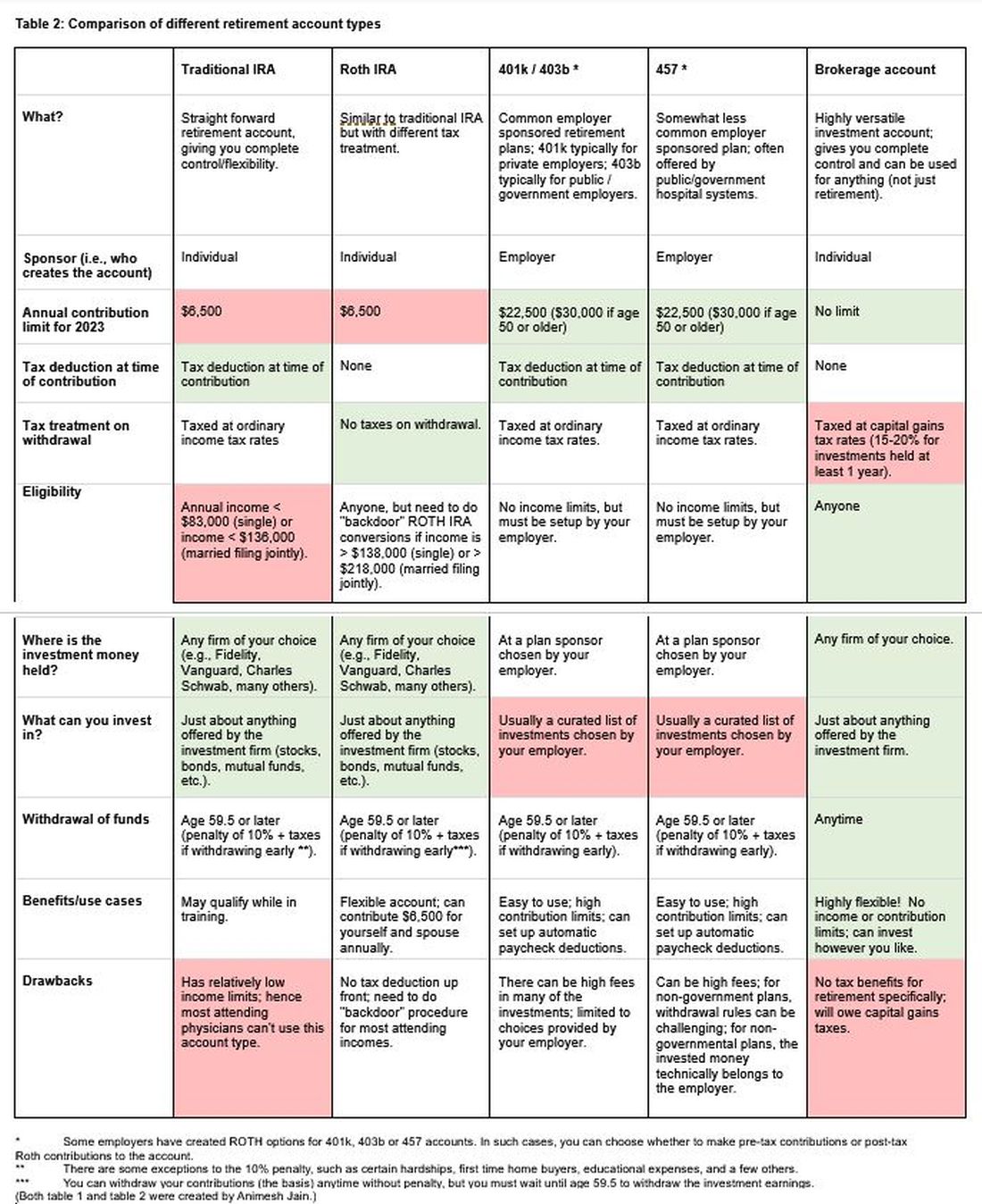

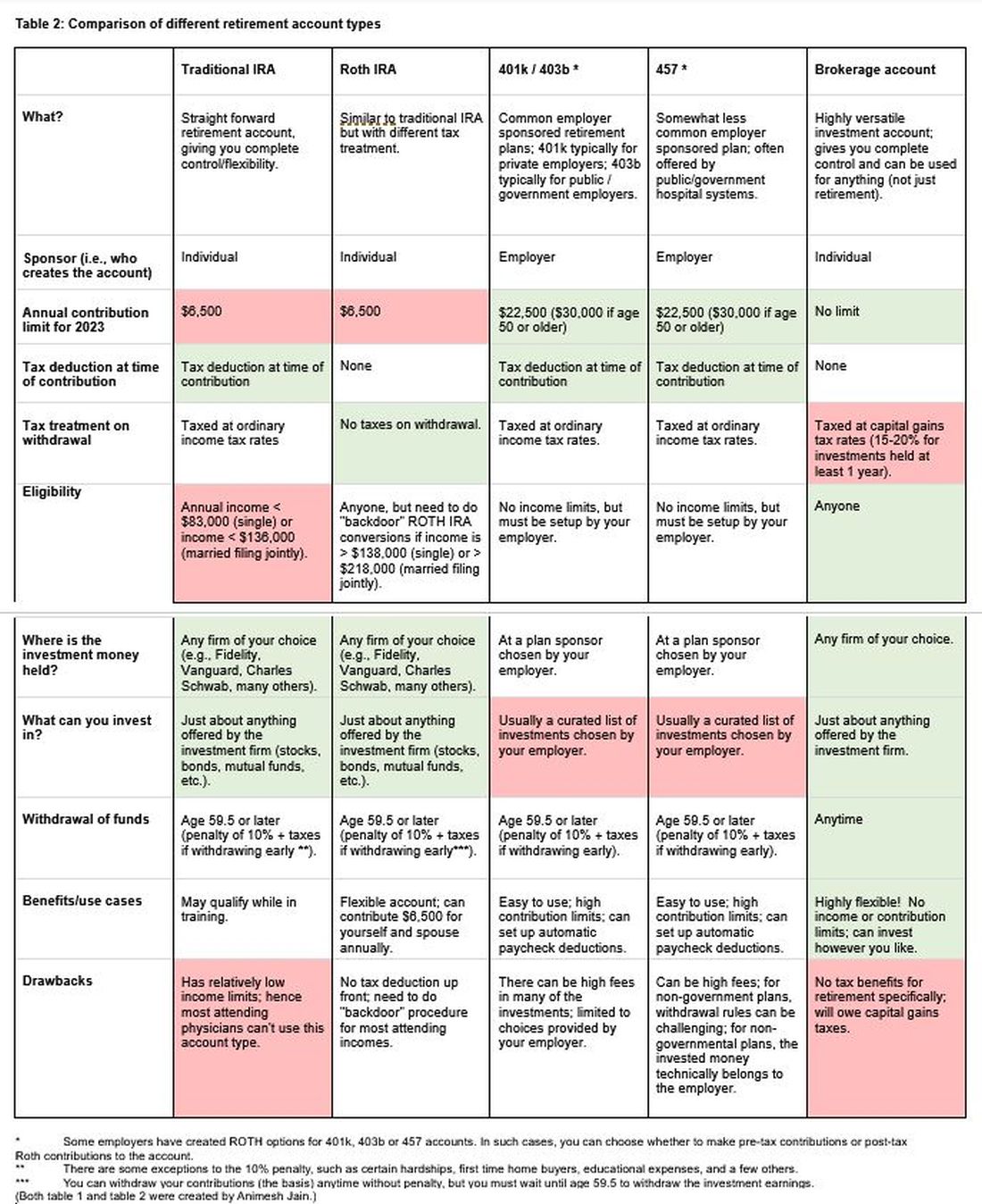

There are two major types of disability policies: group policies and individual policies. See table 1 for a detailed comparison.

Your hospital/employer may provide a group policy at a heavily subsidized rate. Alternatively, you can purchase an individual disability policy, which is independent of your employer and will stay with you even if you change jobs. Currently, the only companies providing high quality own-occupation policies for physicians are Mass Mutual, Principal, Guardian, The Standard, and Ameritas. Because disability insurance is complicated, it is highly advisable to work with an agent experienced in physician disability policies.

Importantly, even if you have a group disability policy, you can purchase an individual policy as a supplement to provide extra coverage. If you leave employers, the individual policy can then become your primary disability policy without any additional medical underwriting.

3. Do I need life insurance? What type should I get?

If anyone is dependent on your income (partner, child, etc.), you should have life insurance. Moreover, if you expect to have dependents in the near future (e.g., children), you could consider getting life insurance now while you are younger and healthier. For a young GI with multiple financial obligations, term life insurance is generally the right product. Term life insurance is a straightforward, affordable product that can be purchased from multiple high-quality insurance carriers. There are two major considerations: The amount of coverage ($2 million, $3 million, etc.) and the length of coverage (20 years, 30 years, etc.). To estimate the appropriate amount of coverage, start with your expected annual household living expenses, and multiply by 25-30. While this is a rule of thumb, it will get you in the ballpark. For many young physicians, a $2-$5 million policy with 20- to 30-year coverage is reasonable.

Many financial advisers may suggest whole life insurance policies. These are typically not the ideal policy for young GIs who are just starting their careers. While whole life insurance may be the right choice in select cases, term life insurance will be the best product for most of TNG’s audience. As an example, a $3 million, 25-year term policy for a healthy, nonsmoking 35-year-old male would cost approximately $175 per month. A similar $3 million whole life policy could cost $2,000 per month or more.

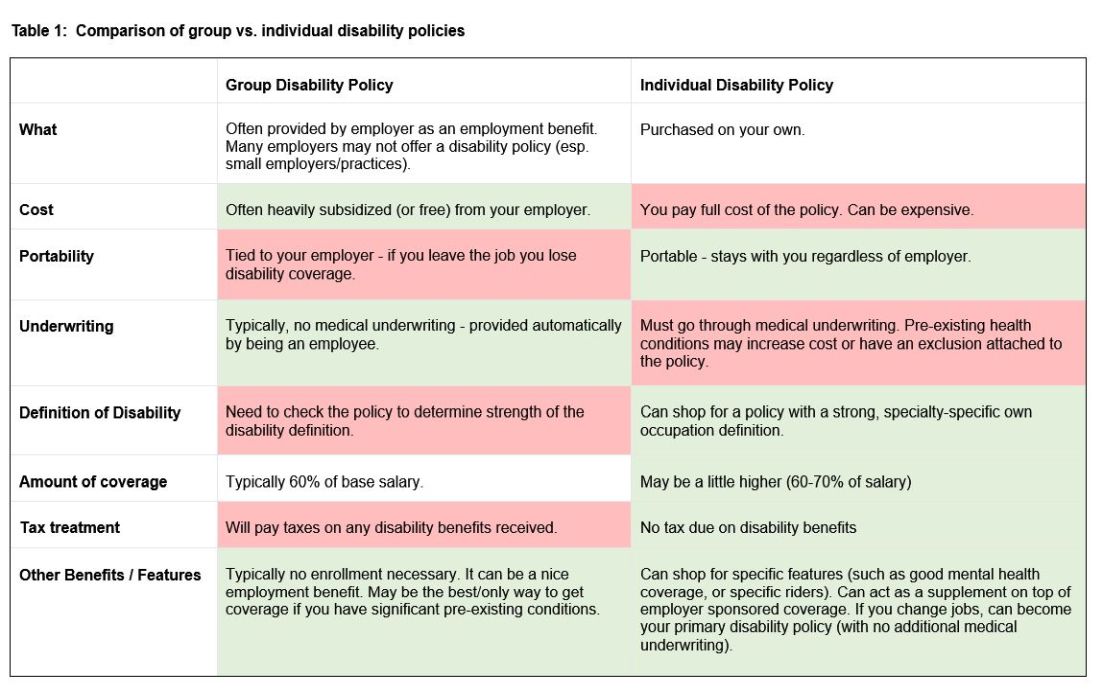

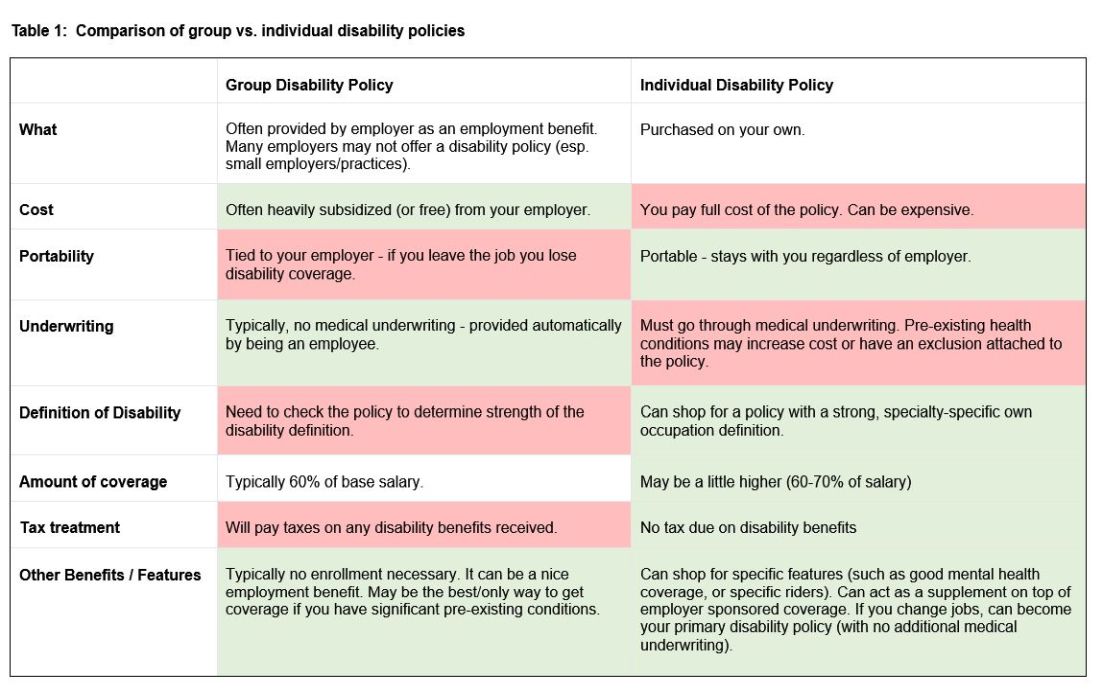

4. What do I need to know about retirement accounts and investing?

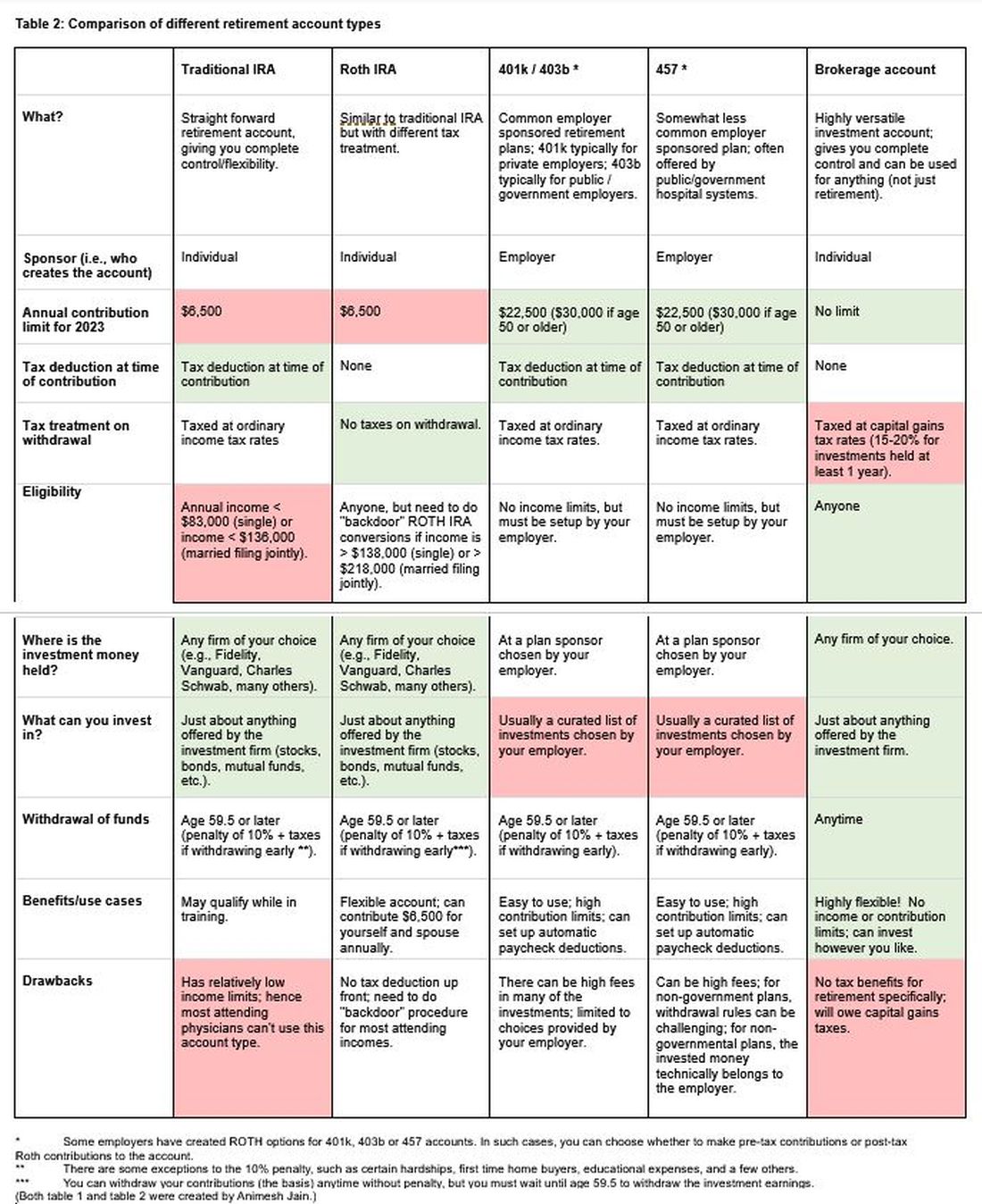

The alphabet soup of retirement accounts can be confusing – IRA, 401k, 457. Retirement accounts provide a tax break to incentivize saving for retirement. Traditional (“non-Roth”) accounts provide a tax break today, but you will pay taxes when withdrawing the money in retirement. Roth accounts provide no tax break now but provide tax-free growth for decades, and no taxes are due when withdrawing money. See table 2 for a detailed comparison of retirement accounts.

Once you place money into a retirement account, you will need to choose specific investments to grow your money. The two most common asset classes are stocks and bonds, though there are many other reasonable assets, such as real estate, commodities, and alternative currencies. It is generally recommended to have a higher proportion of stock-based investments early on (60%-90%) and then increase the ratio of bonds closer to retirement. Using low cost, passive index funds (or exchange traded funds) is a good way to get stock exposure. Target date retirement funds can be a nice tool for beginning investors since they will automatically adjust the stock/bond ratio for you.

Calculating the amount needed for retirement is beyond the scope of this article. However, saving at least 20% of your gross income specifically for retirement is a good starting point and should set you up for a reasonable retirement in about 30 years. For the average GI physician, this would mean saving $4,000 or more per month for retirement. If you aim to retire earlier, consider investing a higher percentage.

5. What do I need to know about buying a house?

The first question to ask is whether it makes sense to rent or buy a house. This is a personal and lifestyle decision, not just a financial decision. Today’s market is difficult with both high home prices and high rent costs. If there is a reasonable chance that you will be moving within 3-5 years, I would consider not buying until your long-term plans are more stable. Moreover, a high proportion of physicians change jobs.4,5,6 If you are just starting a new job, it is often wise to wait at least 6-12 months before buying a house to ensure the new job is a good fit. If you are in a stable long-term situation, it may be reasonable to buy a house. While it is commonly believed that buying a house is a “good financial move,” there are many hidden costs to home ownership, including big ticket repairs, property taxes, and real estate fees when selling a home.

First-time physician home buyers can often secure a physician mortgage with competitive interest rates and a low down payment of 0%-10% instead of the traditional 20% down payment. Moreover, a good physician mortgage should not have private mortgage insurance (PMI). Given the variation between mortgage companies, my most important piece of advice is to shop around for a good mortgage. An independent mortgage broker can be very valuable.

Dr. Jain is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He has no conflicts of interest. The information in this article is meant for general educational purposes only. For individualized personal finance advice, please seek your own financial advisor, tax accountant, insurance broker, attorney, or other financial professional. Follow Dr. Jain @AJainMD on X.

References

1. Future of PSLF Fact Sheet

2. The Loophole That Can Get Thousands of Doctors into PSLF

3. Student loan management: An introduction for the young gastroenterologist

4. Study Shows First Job after Medical Residency Often Doesn’t Last

5. More physicians want to leave their jobs as pay rates fall, survey finds

6. Physician turnover rates are climbing as they clamor for better work-life balance

While this article will get you started, these are complex topics, and each could warrant several standalone articles. I strongly encourage you to develop some basic understanding of personal finance through books, websites, and podcasts. If you can manage Barrett’s esophagus, Crohn’s, and cirrhosis, you can understand the basics of personal finance.

1. What should I do about my student loans? Go for public service loan forgiveness or pay them off?

The first step is knowing your debt burden, knowing your options, and developing a plan to pay off student loans. Public service loan forgiveness (PSLF) can be a good option in many situations. For borrowers staying in academic or other 501(c)(3) positions, PSLF is often an obvious move. Importantly, a fall 2022 statement by the U.S. Department of Education clarified that physicians working as contractors for nonprofit hospitals in California and Texas may now qualify for PSLF.1,2

For trainees debating an academic/501(c)(3) position vs. private practice, I would generally not advise making a career choice based purely on PSLF eligibility. However, borrowers with very high federal student loan burdens (e.g., debt to income ratio of > 2:1), or who are very close to the PSLF 10-year requirement may want to consider choosing a qualifying position for a few years to receive PSLF student loan forgiveness. Please see TNG’s 2020 article3 for a deeper discussion. Consultation with a company specializing in student loan advice for physicians may be well worth the upfront cost.

2. Do I need disability insurance? What should I look for?

I would strongly advise getting disability insurance as soon as possible (including while in training). While disability insurance is not cheap, it is one of the first steps you should take and one of the most important ways to protect your financial future. It is essential to look for a specialty-specific own occupation policy. Such a policy will provide disability payments if you are no longer able to work as a gastroenterologist/hepatologist (including an injury which prevents you from doing endoscopies).

There are two major types of disability policies: group policies and individual policies. See table 1 for a detailed comparison.