User login

Defining Your ‘Success’

Dear Friends,

The prevailing theme of this issue is “Success.” I have learned that “success” is personal and personalized. What “success” looked like 10, or even 5, years ago to me is very different from how I perceive it now; and I know it may be different 5 years from now. My definition of success should not look like another’s — that was the best advice I have gotten over the years and it has kept me constantly redefining what is important to me and placing value on where I want to allocate my time and efforts, at work and at home.

This issue of The New Gastroenterologist highlights topics from successful GIs within their own realms of expertise, offering insights on advancing in academic medicine, navigating financial wellness with a financial adviser, and becoming a future leader in GI.

In this issue’s clinically-focused articles, we spotlight two very nuanced and challenging topics. Dr. Sachin Srinivasan and Dr. Prateek Sharma review Barrett’s esophagus management for our “In Focus” section, with a particular emphasis on Barrett’s endoscopic therapy modalities for dysplasia and early neoplasia. Dr. Brooke Corning and team simplify their approach to pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) in our “Short Clinical Reviews.” They suggest validated ways to assess patient history, pros and cons of various diagnostic tests, and stepwise management of PFD.

Navigating academic promotion can be overwhelming and may not be at the forefront with our early career GIs’ priorities. In our “Early Career” section, Dr. Vineet Rolston interviews two highly accomplished professors in academic medicine, Dr. Sophie Balzora and Dr. Mark Schattner, for their insights into the promotion process and recommendations for junior faculty.

Dr. Anjuli K. Luthra, a therapeutic endoscopist and founder of The Scope of Finance, emphasizes financial wellness for physicians. She breaks down the search for a financial adviser, including the different types, what to ask when searching for the right fit, and what to expect.

Lastly, this issue highlights an AGA program that invests in the development of leaders for the field — the Future Leaders Program (FLP). Dr. Parakkal Deepak and Dr. Edward L. Barnes, along with their mentor, Dr. Aasma Shaukat, describe their experience as a mentee-mentor triad of FLP and how this program has impacted their careers.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: Dr. C.G. Stockton was the first AGA president in 1897, a Professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine and Clinical Medicine at the University of Buffalo in New York, and published on the relationship between GI/Hepatology and gout in the Journal of the American Medical Association the same year of his presidency.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

The prevailing theme of this issue is “Success.” I have learned that “success” is personal and personalized. What “success” looked like 10, or even 5, years ago to me is very different from how I perceive it now; and I know it may be different 5 years from now. My definition of success should not look like another’s — that was the best advice I have gotten over the years and it has kept me constantly redefining what is important to me and placing value on where I want to allocate my time and efforts, at work and at home.

This issue of The New Gastroenterologist highlights topics from successful GIs within their own realms of expertise, offering insights on advancing in academic medicine, navigating financial wellness with a financial adviser, and becoming a future leader in GI.

In this issue’s clinically-focused articles, we spotlight two very nuanced and challenging topics. Dr. Sachin Srinivasan and Dr. Prateek Sharma review Barrett’s esophagus management for our “In Focus” section, with a particular emphasis on Barrett’s endoscopic therapy modalities for dysplasia and early neoplasia. Dr. Brooke Corning and team simplify their approach to pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) in our “Short Clinical Reviews.” They suggest validated ways to assess patient history, pros and cons of various diagnostic tests, and stepwise management of PFD.

Navigating academic promotion can be overwhelming and may not be at the forefront with our early career GIs’ priorities. In our “Early Career” section, Dr. Vineet Rolston interviews two highly accomplished professors in academic medicine, Dr. Sophie Balzora and Dr. Mark Schattner, for their insights into the promotion process and recommendations for junior faculty.

Dr. Anjuli K. Luthra, a therapeutic endoscopist and founder of The Scope of Finance, emphasizes financial wellness for physicians. She breaks down the search for a financial adviser, including the different types, what to ask when searching for the right fit, and what to expect.

Lastly, this issue highlights an AGA program that invests in the development of leaders for the field — the Future Leaders Program (FLP). Dr. Parakkal Deepak and Dr. Edward L. Barnes, along with their mentor, Dr. Aasma Shaukat, describe their experience as a mentee-mentor triad of FLP and how this program has impacted their careers.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: Dr. C.G. Stockton was the first AGA president in 1897, a Professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine and Clinical Medicine at the University of Buffalo in New York, and published on the relationship between GI/Hepatology and gout in the Journal of the American Medical Association the same year of his presidency.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

The prevailing theme of this issue is “Success.” I have learned that “success” is personal and personalized. What “success” looked like 10, or even 5, years ago to me is very different from how I perceive it now; and I know it may be different 5 years from now. My definition of success should not look like another’s — that was the best advice I have gotten over the years and it has kept me constantly redefining what is important to me and placing value on where I want to allocate my time and efforts, at work and at home.

This issue of The New Gastroenterologist highlights topics from successful GIs within their own realms of expertise, offering insights on advancing in academic medicine, navigating financial wellness with a financial adviser, and becoming a future leader in GI.

In this issue’s clinically-focused articles, we spotlight two very nuanced and challenging topics. Dr. Sachin Srinivasan and Dr. Prateek Sharma review Barrett’s esophagus management for our “In Focus” section, with a particular emphasis on Barrett’s endoscopic therapy modalities for dysplasia and early neoplasia. Dr. Brooke Corning and team simplify their approach to pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) in our “Short Clinical Reviews.” They suggest validated ways to assess patient history, pros and cons of various diagnostic tests, and stepwise management of PFD.

Navigating academic promotion can be overwhelming and may not be at the forefront with our early career GIs’ priorities. In our “Early Career” section, Dr. Vineet Rolston interviews two highly accomplished professors in academic medicine, Dr. Sophie Balzora and Dr. Mark Schattner, for their insights into the promotion process and recommendations for junior faculty.

Dr. Anjuli K. Luthra, a therapeutic endoscopist and founder of The Scope of Finance, emphasizes financial wellness for physicians. She breaks down the search for a financial adviser, including the different types, what to ask when searching for the right fit, and what to expect.

Lastly, this issue highlights an AGA program that invests in the development of leaders for the field — the Future Leaders Program (FLP). Dr. Parakkal Deepak and Dr. Edward L. Barnes, along with their mentor, Dr. Aasma Shaukat, describe their experience as a mentee-mentor triad of FLP and how this program has impacted their careers.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: Dr. C.G. Stockton was the first AGA president in 1897, a Professor of the Principles and Practice of Medicine and Clinical Medicine at the University of Buffalo in New York, and published on the relationship between GI/Hepatology and gout in the Journal of the American Medical Association the same year of his presidency.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Working together

Dear Friends,

After 6 months in my first faculty position, I have come to appreciate the term “multidisciplinary approach” more than ever. Not only does this facilitate optimal patient care, but I have personally learned so much from experts in other fields. This theme resonates across this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, from treating complex gallbladder disease, to caring for sexual and gender minorities, and collaborating with the tech industry to advance patient care.

Our “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Andrew Gilman and Dr. Todd Baron, is on endoscopic management of gallbladder disease. They review endoscopic treatment options in patients with benign gallbladder disease, with emphasis on working with surgical and interventional radiology colleagues, as well as relaying endoscopic tips and techniques to achieve success in these complicated procedures.

In the “Short Clinical Reviews” section, Dr. David Chiang and Dr. Victor Chedid highlight the gaps in research and clinical care and competency for sexual and gender minorities, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. They describe the creation of the Pride in IBD clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., that creates a culturally sensitive space to care for this community.

As trainees transition to early faculty, becoming a mentor is a new role that can be very rewarding and daunting at the same time. Dr. Anna Lok, recipient of the AGA’s Distinguished Mentor Award, and Dr. Vincent Chen share invaluable experiences and advice on being a mentor from senior and early-career perspectives, respectively. Similarly in the transition to early faculty, Erin Anderson, CPA, answers five common financial questions that arise to better understand and manage a significant increase in salary.

Lastly, Dr. Shifa Umar describes her unique experience as part of the AGA’s annual Tech Summit Fellows Program, a cross-section of medicine, technology, and innovation.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The concept of the clinicopathologic conference (CPC) was introduced by Dr. Walter B. Cannon as a medical student at Harvard Medical School.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

After 6 months in my first faculty position, I have come to appreciate the term “multidisciplinary approach” more than ever. Not only does this facilitate optimal patient care, but I have personally learned so much from experts in other fields. This theme resonates across this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, from treating complex gallbladder disease, to caring for sexual and gender minorities, and collaborating with the tech industry to advance patient care.

Our “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Andrew Gilman and Dr. Todd Baron, is on endoscopic management of gallbladder disease. They review endoscopic treatment options in patients with benign gallbladder disease, with emphasis on working with surgical and interventional radiology colleagues, as well as relaying endoscopic tips and techniques to achieve success in these complicated procedures.

In the “Short Clinical Reviews” section, Dr. David Chiang and Dr. Victor Chedid highlight the gaps in research and clinical care and competency for sexual and gender minorities, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. They describe the creation of the Pride in IBD clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., that creates a culturally sensitive space to care for this community.

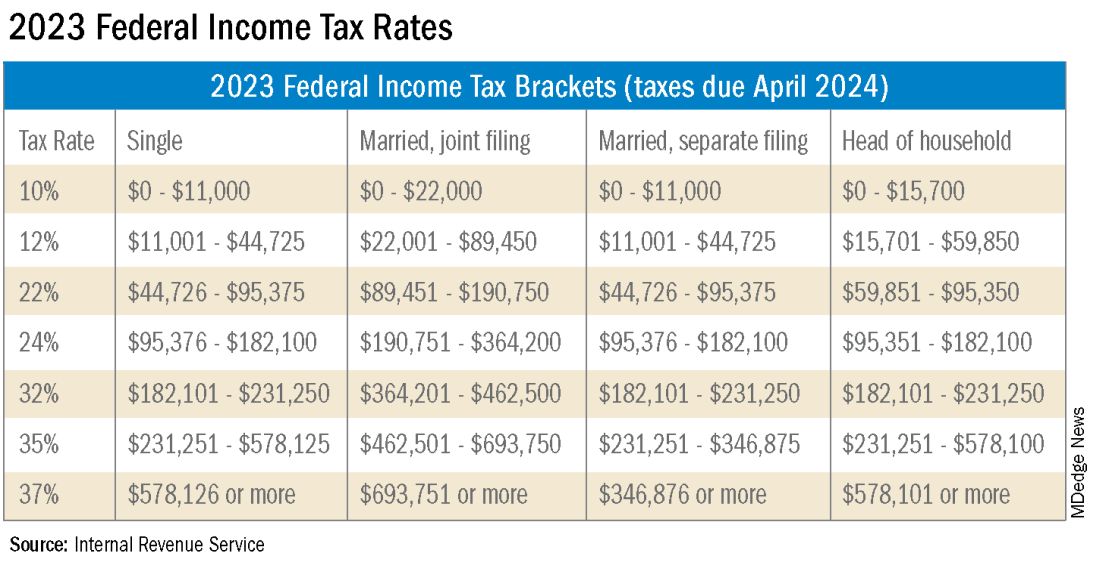

As trainees transition to early faculty, becoming a mentor is a new role that can be very rewarding and daunting at the same time. Dr. Anna Lok, recipient of the AGA’s Distinguished Mentor Award, and Dr. Vincent Chen share invaluable experiences and advice on being a mentor from senior and early-career perspectives, respectively. Similarly in the transition to early faculty, Erin Anderson, CPA, answers five common financial questions that arise to better understand and manage a significant increase in salary.

Lastly, Dr. Shifa Umar describes her unique experience as part of the AGA’s annual Tech Summit Fellows Program, a cross-section of medicine, technology, and innovation.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The concept of the clinicopathologic conference (CPC) was introduced by Dr. Walter B. Cannon as a medical student at Harvard Medical School.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

After 6 months in my first faculty position, I have come to appreciate the term “multidisciplinary approach” more than ever. Not only does this facilitate optimal patient care, but I have personally learned so much from experts in other fields. This theme resonates across this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, from treating complex gallbladder disease, to caring for sexual and gender minorities, and collaborating with the tech industry to advance patient care.

Our “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Andrew Gilman and Dr. Todd Baron, is on endoscopic management of gallbladder disease. They review endoscopic treatment options in patients with benign gallbladder disease, with emphasis on working with surgical and interventional radiology colleagues, as well as relaying endoscopic tips and techniques to achieve success in these complicated procedures.

In the “Short Clinical Reviews” section, Dr. David Chiang and Dr. Victor Chedid highlight the gaps in research and clinical care and competency for sexual and gender minorities, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. They describe the creation of the Pride in IBD clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., that creates a culturally sensitive space to care for this community.

As trainees transition to early faculty, becoming a mentor is a new role that can be very rewarding and daunting at the same time. Dr. Anna Lok, recipient of the AGA’s Distinguished Mentor Award, and Dr. Vincent Chen share invaluable experiences and advice on being a mentor from senior and early-career perspectives, respectively. Similarly in the transition to early faculty, Erin Anderson, CPA, answers five common financial questions that arise to better understand and manage a significant increase in salary.

Lastly, Dr. Shifa Umar describes her unique experience as part of the AGA’s annual Tech Summit Fellows Program, a cross-section of medicine, technology, and innovation.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The concept of the clinicopathologic conference (CPC) was introduced by Dr. Walter B. Cannon as a medical student at Harvard Medical School.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Endoscopic Management of Benign Gallbladder Disease

Introduction

The treatment of benign gallbladder disease has changed substantially in the past decade, but this represents only a snapshot in the evolutionary history of the management of this organ. What began as a problem managed exclusively by open cholecystectomy (CCY) transitioned into a race toward minimally invasive approaches in the 1980s, with advances from gastroenterology, surgery, and radiology.

The opening strides were made in 1980 with the first description of percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) by Dr. R.W. Radder.1 Shortly thereafter, in 1984, Dr. Richard Kozarek first reported the feasibility of selective cystic duct cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).2 Subsequent stenting for the treatment of acute cholecystitis (endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage, ET-GBD) was then reported by Tamada et. al. in 1991.3 Not to be outdone, the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was completed by Dr. Med Erich Mühe of Germany in 1985.4 More recently, with the expansion of interventional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), the first transmural EUS-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) was described by Dr. Baron and Dr. Topazian in 2007.5

The subsequent advent of lumen apposing metal stents (LAMS) has cemented EUS-GBD in the toolbox of treatment for benign gallbladder disease. Results of a recent prospective multicenter trial, with a Food and Drug Administration–approved protocol and investigational device exemption, have been published, opening the door for the expansion of FDA approved indications for this device.6

Benign gallbladder disease encompasses both polyps (benign and premalignant) and cholecystitis (acute/chronic, calculous/acalculous), in addition to others. The four management techniques (LC, PC, ET-GBD, and EUS-GBD) have filled integral niches in the management of these patients. Even gallbladder polyps have not been able to escape the reach of endoscopic approaches with the recent description of LAMS-assisted polypectomy as part of a gallbladder preserving strategy.7,8 While EUS-GBD also has been used for biliary decompression in the presence of a patent cystic duct and absence of cholecystitis, .9 Both of these techniques have gained wide recognition and/or guideline support for their use from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE).10,11 In addition, there is now one FDA-approved stent device for treatment of acute cholecystitis in patients unfit for surgery.

Techniques & Tips

ET-GBD

- During ERCP, after successful cannulation of the bile duct, attempted wire cannulation of the cystic duct is performed.

A cholangiogram, which clearly delineates the insertion of the cystic duct into the main bile duct, can enhance cannulation success. Rotatable fluoroscopy can facilitate identification.

- After anatomy is clear, wire access is often best achieved using a sphincterotome or stone retrieval (occlusion) balloon.

The balloon, once inflated, can be pulled downward to establish traction on the main bile duct, which can straighten the approach.

- After superficial wire engagement into the cystic duct, the accessory used can be slowly advanced into the cystic duct to stabilize the catheter and then navigate the valves of Heister to reach the gallbladder lumen.

Use of a sphincterotome, which directs toward the patient’s right (most often direction of cystic duct takeoff), is helpful. Angled guidewires are preferable. We often use a 0.035-inch, 260-cm angled hydrophilic wire (GLIDEWIRE; Terumo, Somerset, NJ) to overcome this challenging portion of ET-GBD.

If despite the above maneuvers the guidewire has failed to enter the cystic duct, cholangioscopy can be used to identify the orifice and/or stabilize deep wire cannulation. This is often cumbersome, time consuming, does not always produce success, and requires additional expertise.

- If a stone is encountered that cannot be extracted or traversed by a guidewire, cholangioscopy with electrohydraulic lithotripsy can be pursued.

- After the guidewire has entered the gallbladder, a 5 French or 7 French plastic double pigtail stent is placed. Typical lengths are 9-15 cm.

Some authors prefer to use two side-by-side plastic stents.12 This has been shown retrospectively to enhance the long term clinical success of ET-GBD but with additional technical difficulty.

- This stent can remain in place indefinitely and need not be exchanged, though it should be removed just prior to CCY if pursued. Alternatively, the surgeon can be alerted to its presence and, if comfortable, it can be removed intraoperatively.

EUS-GBD

- Use of fluoroscopy is optional but can enhance technical success in selected situations.

- Conversion, or internalization, of PC is reasonable and can enhance patient quality of life.13

- If the gallbladder wall is not in close apposition to the duodenal (or gastric) wall, consider measuring the distance.

We preferentially use 10-mm diameter by 10-mm saddle length LAMS for EUS-GBD, unless the above distance warrants use of a 15-mm by 15-mm LAMS (AXIOS, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA). If the distance is greater than 15 mm, consider searching for an alternative site, using a traditional biliary fully covered self-expandable metal stent (FCSEMS) for longer length, or converting to ET-GBD. Smaller diameter (8 mm) with an 8-mm saddle length can be used as well. The optimal diameter is unknown and also dependent on whether transluminal endoscopic diagnosis or therapy is a consideration.

- If there is difficulty locating the gallbladder, it may be decompressed or small (particularly if PC or a partial CCY has already been performed).

If a cholecystostomy tube is in place, instillation of sterile water via the tube can sometimes improve the target for LAMS placement, though caution should be made to not over-distend the gallbladder. ERCP with placement of a nasobiliary tube into the gallbladder can also serve this purpose and has been previously described.14

The gallbladder can be punctured with a 19-gauge FNA needle to instill sterile water and distend the gallbladder with the added benefit of being able to pass a guidewire, which may enhance procedural safety in difficult cases. However, success of this technique is contingent on fluid remaining within the gallbladder and not transiting out via the cystic duct. Expedient exchange of the FNA needle for the LAMS device may be necessary.

- Attempt to confirm location within the duodenum prior to puncture, as gastric origins can pose unique ramifications (i.e. potential for partial gastric outlet obstruction, obstruction of LAMS with food debris, etc.).

It can be easy to mistake an unintentional pre-pyloric position for a position within the duodenum since the working channel is behind (proximal to) the echoprobe.

- Turning off Doppler flow prior to advancement of the cautery enhanced LAMS can reduce obscurement of views on entry into the gallbladder. Lack of certainty about entry or misdeployment after presumed entry herald the most challenging aspect of EUS-GBD.

Utilization of a previously placed guidewire or advancement of one preloaded into the LAMS can aid in both enhancing confidence in location and assist with salvage maneuvers, if needed.

- After successful deployment of the LAMS we routinely place a double pigtail plastic stent through it (typically 7 French by 4 cm) to maintain patency. This may also prevent bleeding from the LAMS flange abrading the wall of either lumen.

- We routinely exchange the LAMS for two double pigtail plastic stents (typically 7 French by 4 cm) 4 weeks after initial placement especially when there is a more than modest residual stone burden (data in press). These plastic stents can remain in place indefinitely.

This exchange can be deferred if the patient is not expected to survive until the one-year anniversary of LAMS deployment. After one year the LAMS plastic covering may degrade and pose additional problems.15

LAMS Misdeployment Salvage Tips

- Salvage techniques can vary from simple to complex.

- If a wire is in place, it can be used to balloon or catheter dilate the tract and place a FCSEMS traversing the gallbladder and duodenal/gastric lumens. A similar approach can be used if the LAMS deployed on only one side (gallbladder or duodenum/stomach) and the other flange is within the peritoneum.

- The most challenging scenario to salvage is if the LAMS is misdeployed or becomes dislodged and no wire is present. This is why the use of a guidewire, even if preloaded into the LAMS and placement is freehand, is essential for EUS-GBD. A potential technique is to balloon dilate the duodenal/gastric defect and drive the endoscope into the peritoneum to reconnect that lumen to the gallbladder defect or LAMS, depending on the site of misdeployment. Doing so requires a high degree of commitment and skill and should not be done casually.

- If uncertainty remains or if misdeployment has occurred and salvage attempts have failed, consider closure of the duodenal/gastric defect and conversion to ET-GBD.

This may both treat the initial procedural indication and assist with what is essentially a large bile leak, which might also require percutaneous therapy for non-surgical management.

- For endoscopists with limited experience at salvage techniques, it is reasonable for the threshold for conversion to be low, assuming experience with and confidence in ET-GBD is high.

- If salvage is successful but ambiguity remains, consider obtaining a cholangiogram via the LAMS to confirm positioning and absence of leak.

Adverse Events

Both ET-GBD and EUS-GBD should be performed by an endoscopist comfortable with their techniques and the management of their adverse events (AEs). Rates for EUS-GBD AEs in patients at high risk for LC were reported in one international multicenter registry to be 15.3% with a 30-day mortality of 9.2%, with a significant predictor of AE being endoscopist experience less than 25 procedures.16 A meta-analysis also found an overall AE rate of 18.31%, with rates for perforation and stent related AEs (i.e. migration, occlusion, pneumoperitoneum) being 6.71% and 8.16%, respectively.17 For this reason, we recommend that patients with cholecystitis who are deemed to be poor surgical candidates be transferred to a tertiary referral center with expertise in these approaches. Rates of AEs for ET-GBD are similar to that for standard ERCP, with reported ranges of 5%-10.3%.10

Comparisons Between Techniques

The decision on which technique to utilize for endoscopic management of cholecystitis or symptomatic cholelithiasis depends first and foremost on the expertise and comfort level of the endoscopist. Given the additional training that an advanced endoscopist needs to perform EUS-GBD, combined with the perhaps slightly higher AE rate and permanency of endoscopic cholecystostomy, it is reasonable to proceed with a trial of ET-GBD if confidence is insufficient. However, ET-GBD can certainly be more technically challenging and less effective than EUS-GBD, with lower reported technical and clinical success rates (technical 85.3% vs 93.0%, clinical 95.2% vs 97.3%).18 Despite this, the rate of recurrence of cholecystitis is similar between ET-GBD and EUS-GBD (4.6% vs 4.2%).19 As stated above in the Techniques & Tips section, some authors utilize two plastic stents for ET-GBD for this purpose, though with increased technical difficulty. It is important to remember that these numbers, when paired with AE rates, represent the achievements of expert endoscopists.

Discussion with your surgery team is important when deciding modality. If the patient is felt to be a potential candidate for CCY, and EUS-GBD is not being used as a destination therapy, the surgeon may prefer ET-GBD. EUS-GBD may enhance the difficulty of CCY, though at least one study demonstrated that this was no different than PC with similar rates of conversion from LC to open CCY.20 This conversation is most critical for patients who are potential liver transplant candidates. For patients where this is not a consideration there is some evidence to suggest equivalency between LC and EUS-GBD, though certainly EUS-GBD has not yet supplanted LC as the treatment of choice.21

While there may eventually be a shift towards EUS-GBD instead of LC in certain patient groups, what is clearer are the advantages of EUS-GBD over PC. One recent meta-analysis revealed that EUS-GBD has significantly favorable odds of overall adverse events (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18-1.00), shorter hospital stay (2.76 less days, 95% CI 0.31-5.20 less days), reinterventions (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02-0.98), and unplanned readmissions (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03-0.70) compared to PC.22 Beyond the data, though, are the emotional and psychological impacts an external drain can have on a patient.

Conclusion

When expertise is available, endoscopic treatment of benign gallbladder disease has a definite role but should be undertaken only by those with the experience and skill to safely do so. Decision to proceed, especially with EUS-GBD, should be accompanied by conversation and collaboration with surgical teams. If a patient is under consideration for PC instead of LC, it may be worthwhile to seek consultation with a local center with expertise in EUS-GBD or ET-GBD. The adoption of these techniques is part of the paradigm shift, seen broadly throughout medicine, towards minimally invasive interventions, particularly in advanced endoscopy.

Dr. Gilman (X @a_gilman) and Dr. Baron (X @EndoTx) are with the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. Dr. Gilman has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Baron is a consultant and speaker for Ambu, Boston Scientific, Cook Endoscopy, Medtronic, Olympus America, and W.L. Gore.

References

1. Radder RW. Ultrasonically guided percutaneous catheter drainage for gallbladder empyema. Diagn Imaging. 1980;49:330-333.

2. Kozarek RA. Selective cannulation of the cystic duct at time of ERCP. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:37-40.

3. Tamada K et al. Efficacy of endoscopic retrograde cholecystoendoprosthesis (ERCCE) for cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 1991;23:2-3.

4. Reynolds W. The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2001;5:89-94.

5. Baron TH, Topazian MD. Endoscopic transduodenal drainage of the gallbladder: Implications for endoluminal treatment of gallbladder disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Apr;65(4):735-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.07.041.

6. Irani SS et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transluminal gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis: A prospective multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2023 Sep 1;278(3):e556-e562. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005784.

7. Shen Y et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholecystostomy for resection of gallbladder polyps with lumen-apposing metal stent. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Oct 23;99(43):e22903. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022903.

8. Pang H et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder endoscopic mucosal resection: A pilot porcine study. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2023 Feb;32(1):24-32. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2022.2153228.

9. Imai H et al. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage for rescue treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction after unsuccessful ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jul;84(1):147-51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.12.024.

10. Saumoy M et al. Endoscopic therapies for gallbladder drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Oct;94(4):671-84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.05.031.

11. Van der Merwe SW et al. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022 Feb;54(2):185-205. doi: 10.1055/a-1717-1391.

12. Storm AC et al. Transpapillary gallbladder stent placement for long-term therapy of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Oct;94(4):742-8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.025.

13. James TW, Baron TH. Converting percutaneous gallbladder drainage to internal drainage using EUS-guided therapy: A review of current practices and procedures. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018 Mar-Apr;7(2):93-6. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_110_17.

14. James TW, Baron TH. Transpapillary nasocystic tube placement to allow gallbladder distention for EUS-guided cholecystoduodenostomy. VideoGIE. 2019 Dec;4(12):561-2. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2019.08.009.

15. Gilman AJ, Baron TH. Delamination of a lumen-apposing metal stent with tissue ingrowth and stent-in-stent removal. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Sep;98(3):451-3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.04.2087.

16. Teoh AY et al. Outcomes of an international multicenter registry on EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in patients at high risk for cholecystectomy. Endosc Int Open. 2019 Aug;7(8):E964-E973. doi: 10.1055/a-0915-2098.

17. Kalva NR et al. Efficacy and safety of lumen apposing self-expandable metal stents for EUS guided cholecystostomy: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:7070961. doi: 10.1155/2018/7070961.

18. Khan MA et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: Is it better than percutaneous gallbladder drainage? Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Jan;85(1):76-87 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.06.032.

19. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage, transpapillary drainage, or percutaneous drainage in high risk acute cholecystitis patients: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2020 Feb;52(2):96-106. doi: 10.1055/a-1020-3932.

20. Jang JW et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Apr;142(4):805-11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.051.

21. Teoh AYB et al. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a propensity score analysis with 1-year follow-up data. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Mar;93(3):577-83. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.066.

22. Luk SW et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage versus percutaneous cholecystostomy for high risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019 Aug;51(8):722-32. doi: 10.1055/a-0929-6603.

Introduction

The treatment of benign gallbladder disease has changed substantially in the past decade, but this represents only a snapshot in the evolutionary history of the management of this organ. What began as a problem managed exclusively by open cholecystectomy (CCY) transitioned into a race toward minimally invasive approaches in the 1980s, with advances from gastroenterology, surgery, and radiology.

The opening strides were made in 1980 with the first description of percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) by Dr. R.W. Radder.1 Shortly thereafter, in 1984, Dr. Richard Kozarek first reported the feasibility of selective cystic duct cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).2 Subsequent stenting for the treatment of acute cholecystitis (endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage, ET-GBD) was then reported by Tamada et. al. in 1991.3 Not to be outdone, the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was completed by Dr. Med Erich Mühe of Germany in 1985.4 More recently, with the expansion of interventional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), the first transmural EUS-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) was described by Dr. Baron and Dr. Topazian in 2007.5

The subsequent advent of lumen apposing metal stents (LAMS) has cemented EUS-GBD in the toolbox of treatment for benign gallbladder disease. Results of a recent prospective multicenter trial, with a Food and Drug Administration–approved protocol and investigational device exemption, have been published, opening the door for the expansion of FDA approved indications for this device.6

Benign gallbladder disease encompasses both polyps (benign and premalignant) and cholecystitis (acute/chronic, calculous/acalculous), in addition to others. The four management techniques (LC, PC, ET-GBD, and EUS-GBD) have filled integral niches in the management of these patients. Even gallbladder polyps have not been able to escape the reach of endoscopic approaches with the recent description of LAMS-assisted polypectomy as part of a gallbladder preserving strategy.7,8 While EUS-GBD also has been used for biliary decompression in the presence of a patent cystic duct and absence of cholecystitis, .9 Both of these techniques have gained wide recognition and/or guideline support for their use from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE).10,11 In addition, there is now one FDA-approved stent device for treatment of acute cholecystitis in patients unfit for surgery.

Techniques & Tips

ET-GBD

- During ERCP, after successful cannulation of the bile duct, attempted wire cannulation of the cystic duct is performed.

A cholangiogram, which clearly delineates the insertion of the cystic duct into the main bile duct, can enhance cannulation success. Rotatable fluoroscopy can facilitate identification.

- After anatomy is clear, wire access is often best achieved using a sphincterotome or stone retrieval (occlusion) balloon.

The balloon, once inflated, can be pulled downward to establish traction on the main bile duct, which can straighten the approach.

- After superficial wire engagement into the cystic duct, the accessory used can be slowly advanced into the cystic duct to stabilize the catheter and then navigate the valves of Heister to reach the gallbladder lumen.

Use of a sphincterotome, which directs toward the patient’s right (most often direction of cystic duct takeoff), is helpful. Angled guidewires are preferable. We often use a 0.035-inch, 260-cm angled hydrophilic wire (GLIDEWIRE; Terumo, Somerset, NJ) to overcome this challenging portion of ET-GBD.

If despite the above maneuvers the guidewire has failed to enter the cystic duct, cholangioscopy can be used to identify the orifice and/or stabilize deep wire cannulation. This is often cumbersome, time consuming, does not always produce success, and requires additional expertise.

- If a stone is encountered that cannot be extracted or traversed by a guidewire, cholangioscopy with electrohydraulic lithotripsy can be pursued.

- After the guidewire has entered the gallbladder, a 5 French or 7 French plastic double pigtail stent is placed. Typical lengths are 9-15 cm.

Some authors prefer to use two side-by-side plastic stents.12 This has been shown retrospectively to enhance the long term clinical success of ET-GBD but with additional technical difficulty.

- This stent can remain in place indefinitely and need not be exchanged, though it should be removed just prior to CCY if pursued. Alternatively, the surgeon can be alerted to its presence and, if comfortable, it can be removed intraoperatively.

EUS-GBD

- Use of fluoroscopy is optional but can enhance technical success in selected situations.

- Conversion, or internalization, of PC is reasonable and can enhance patient quality of life.13

- If the gallbladder wall is not in close apposition to the duodenal (or gastric) wall, consider measuring the distance.

We preferentially use 10-mm diameter by 10-mm saddle length LAMS for EUS-GBD, unless the above distance warrants use of a 15-mm by 15-mm LAMS (AXIOS, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA). If the distance is greater than 15 mm, consider searching for an alternative site, using a traditional biliary fully covered self-expandable metal stent (FCSEMS) for longer length, or converting to ET-GBD. Smaller diameter (8 mm) with an 8-mm saddle length can be used as well. The optimal diameter is unknown and also dependent on whether transluminal endoscopic diagnosis or therapy is a consideration.

- If there is difficulty locating the gallbladder, it may be decompressed or small (particularly if PC or a partial CCY has already been performed).

If a cholecystostomy tube is in place, instillation of sterile water via the tube can sometimes improve the target for LAMS placement, though caution should be made to not over-distend the gallbladder. ERCP with placement of a nasobiliary tube into the gallbladder can also serve this purpose and has been previously described.14

The gallbladder can be punctured with a 19-gauge FNA needle to instill sterile water and distend the gallbladder with the added benefit of being able to pass a guidewire, which may enhance procedural safety in difficult cases. However, success of this technique is contingent on fluid remaining within the gallbladder and not transiting out via the cystic duct. Expedient exchange of the FNA needle for the LAMS device may be necessary.

- Attempt to confirm location within the duodenum prior to puncture, as gastric origins can pose unique ramifications (i.e. potential for partial gastric outlet obstruction, obstruction of LAMS with food debris, etc.).

It can be easy to mistake an unintentional pre-pyloric position for a position within the duodenum since the working channel is behind (proximal to) the echoprobe.

- Turning off Doppler flow prior to advancement of the cautery enhanced LAMS can reduce obscurement of views on entry into the gallbladder. Lack of certainty about entry or misdeployment after presumed entry herald the most challenging aspect of EUS-GBD.

Utilization of a previously placed guidewire or advancement of one preloaded into the LAMS can aid in both enhancing confidence in location and assist with salvage maneuvers, if needed.

- After successful deployment of the LAMS we routinely place a double pigtail plastic stent through it (typically 7 French by 4 cm) to maintain patency. This may also prevent bleeding from the LAMS flange abrading the wall of either lumen.

- We routinely exchange the LAMS for two double pigtail plastic stents (typically 7 French by 4 cm) 4 weeks after initial placement especially when there is a more than modest residual stone burden (data in press). These plastic stents can remain in place indefinitely.

This exchange can be deferred if the patient is not expected to survive until the one-year anniversary of LAMS deployment. After one year the LAMS plastic covering may degrade and pose additional problems.15

LAMS Misdeployment Salvage Tips

- Salvage techniques can vary from simple to complex.

- If a wire is in place, it can be used to balloon or catheter dilate the tract and place a FCSEMS traversing the gallbladder and duodenal/gastric lumens. A similar approach can be used if the LAMS deployed on only one side (gallbladder or duodenum/stomach) and the other flange is within the peritoneum.

- The most challenging scenario to salvage is if the LAMS is misdeployed or becomes dislodged and no wire is present. This is why the use of a guidewire, even if preloaded into the LAMS and placement is freehand, is essential for EUS-GBD. A potential technique is to balloon dilate the duodenal/gastric defect and drive the endoscope into the peritoneum to reconnect that lumen to the gallbladder defect or LAMS, depending on the site of misdeployment. Doing so requires a high degree of commitment and skill and should not be done casually.

- If uncertainty remains or if misdeployment has occurred and salvage attempts have failed, consider closure of the duodenal/gastric defect and conversion to ET-GBD.

This may both treat the initial procedural indication and assist with what is essentially a large bile leak, which might also require percutaneous therapy for non-surgical management.

- For endoscopists with limited experience at salvage techniques, it is reasonable for the threshold for conversion to be low, assuming experience with and confidence in ET-GBD is high.

- If salvage is successful but ambiguity remains, consider obtaining a cholangiogram via the LAMS to confirm positioning and absence of leak.

Adverse Events

Both ET-GBD and EUS-GBD should be performed by an endoscopist comfortable with their techniques and the management of their adverse events (AEs). Rates for EUS-GBD AEs in patients at high risk for LC were reported in one international multicenter registry to be 15.3% with a 30-day mortality of 9.2%, with a significant predictor of AE being endoscopist experience less than 25 procedures.16 A meta-analysis also found an overall AE rate of 18.31%, with rates for perforation and stent related AEs (i.e. migration, occlusion, pneumoperitoneum) being 6.71% and 8.16%, respectively.17 For this reason, we recommend that patients with cholecystitis who are deemed to be poor surgical candidates be transferred to a tertiary referral center with expertise in these approaches. Rates of AEs for ET-GBD are similar to that for standard ERCP, with reported ranges of 5%-10.3%.10

Comparisons Between Techniques

The decision on which technique to utilize for endoscopic management of cholecystitis or symptomatic cholelithiasis depends first and foremost on the expertise and comfort level of the endoscopist. Given the additional training that an advanced endoscopist needs to perform EUS-GBD, combined with the perhaps slightly higher AE rate and permanency of endoscopic cholecystostomy, it is reasonable to proceed with a trial of ET-GBD if confidence is insufficient. However, ET-GBD can certainly be more technically challenging and less effective than EUS-GBD, with lower reported technical and clinical success rates (technical 85.3% vs 93.0%, clinical 95.2% vs 97.3%).18 Despite this, the rate of recurrence of cholecystitis is similar between ET-GBD and EUS-GBD (4.6% vs 4.2%).19 As stated above in the Techniques & Tips section, some authors utilize two plastic stents for ET-GBD for this purpose, though with increased technical difficulty. It is important to remember that these numbers, when paired with AE rates, represent the achievements of expert endoscopists.

Discussion with your surgery team is important when deciding modality. If the patient is felt to be a potential candidate for CCY, and EUS-GBD is not being used as a destination therapy, the surgeon may prefer ET-GBD. EUS-GBD may enhance the difficulty of CCY, though at least one study demonstrated that this was no different than PC with similar rates of conversion from LC to open CCY.20 This conversation is most critical for patients who are potential liver transplant candidates. For patients where this is not a consideration there is some evidence to suggest equivalency between LC and EUS-GBD, though certainly EUS-GBD has not yet supplanted LC as the treatment of choice.21

While there may eventually be a shift towards EUS-GBD instead of LC in certain patient groups, what is clearer are the advantages of EUS-GBD over PC. One recent meta-analysis revealed that EUS-GBD has significantly favorable odds of overall adverse events (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18-1.00), shorter hospital stay (2.76 less days, 95% CI 0.31-5.20 less days), reinterventions (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02-0.98), and unplanned readmissions (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03-0.70) compared to PC.22 Beyond the data, though, are the emotional and psychological impacts an external drain can have on a patient.

Conclusion

When expertise is available, endoscopic treatment of benign gallbladder disease has a definite role but should be undertaken only by those with the experience and skill to safely do so. Decision to proceed, especially with EUS-GBD, should be accompanied by conversation and collaboration with surgical teams. If a patient is under consideration for PC instead of LC, it may be worthwhile to seek consultation with a local center with expertise in EUS-GBD or ET-GBD. The adoption of these techniques is part of the paradigm shift, seen broadly throughout medicine, towards minimally invasive interventions, particularly in advanced endoscopy.

Dr. Gilman (X @a_gilman) and Dr. Baron (X @EndoTx) are with the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. Dr. Gilman has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Baron is a consultant and speaker for Ambu, Boston Scientific, Cook Endoscopy, Medtronic, Olympus America, and W.L. Gore.

References

1. Radder RW. Ultrasonically guided percutaneous catheter drainage for gallbladder empyema. Diagn Imaging. 1980;49:330-333.

2. Kozarek RA. Selective cannulation of the cystic duct at time of ERCP. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:37-40.

3. Tamada K et al. Efficacy of endoscopic retrograde cholecystoendoprosthesis (ERCCE) for cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 1991;23:2-3.

4. Reynolds W. The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2001;5:89-94.

5. Baron TH, Topazian MD. Endoscopic transduodenal drainage of the gallbladder: Implications for endoluminal treatment of gallbladder disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Apr;65(4):735-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.07.041.

6. Irani SS et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transluminal gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis: A prospective multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2023 Sep 1;278(3):e556-e562. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005784.

7. Shen Y et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholecystostomy for resection of gallbladder polyps with lumen-apposing metal stent. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Oct 23;99(43):e22903. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022903.

8. Pang H et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder endoscopic mucosal resection: A pilot porcine study. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2023 Feb;32(1):24-32. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2022.2153228.

9. Imai H et al. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage for rescue treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction after unsuccessful ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jul;84(1):147-51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.12.024.

10. Saumoy M et al. Endoscopic therapies for gallbladder drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Oct;94(4):671-84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.05.031.

11. Van der Merwe SW et al. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022 Feb;54(2):185-205. doi: 10.1055/a-1717-1391.

12. Storm AC et al. Transpapillary gallbladder stent placement for long-term therapy of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Oct;94(4):742-8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.025.

13. James TW, Baron TH. Converting percutaneous gallbladder drainage to internal drainage using EUS-guided therapy: A review of current practices and procedures. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018 Mar-Apr;7(2):93-6. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_110_17.

14. James TW, Baron TH. Transpapillary nasocystic tube placement to allow gallbladder distention for EUS-guided cholecystoduodenostomy. VideoGIE. 2019 Dec;4(12):561-2. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2019.08.009.

15. Gilman AJ, Baron TH. Delamination of a lumen-apposing metal stent with tissue ingrowth and stent-in-stent removal. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Sep;98(3):451-3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.04.2087.

16. Teoh AY et al. Outcomes of an international multicenter registry on EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in patients at high risk for cholecystectomy. Endosc Int Open. 2019 Aug;7(8):E964-E973. doi: 10.1055/a-0915-2098.

17. Kalva NR et al. Efficacy and safety of lumen apposing self-expandable metal stents for EUS guided cholecystostomy: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:7070961. doi: 10.1155/2018/7070961.

18. Khan MA et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: Is it better than percutaneous gallbladder drainage? Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Jan;85(1):76-87 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.06.032.

19. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage, transpapillary drainage, or percutaneous drainage in high risk acute cholecystitis patients: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2020 Feb;52(2):96-106. doi: 10.1055/a-1020-3932.

20. Jang JW et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Apr;142(4):805-11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.051.

21. Teoh AYB et al. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a propensity score analysis with 1-year follow-up data. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Mar;93(3):577-83. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.066.

22. Luk SW et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage versus percutaneous cholecystostomy for high risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019 Aug;51(8):722-32. doi: 10.1055/a-0929-6603.

Introduction

The treatment of benign gallbladder disease has changed substantially in the past decade, but this represents only a snapshot in the evolutionary history of the management of this organ. What began as a problem managed exclusively by open cholecystectomy (CCY) transitioned into a race toward minimally invasive approaches in the 1980s, with advances from gastroenterology, surgery, and radiology.

The opening strides were made in 1980 with the first description of percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) by Dr. R.W. Radder.1 Shortly thereafter, in 1984, Dr. Richard Kozarek first reported the feasibility of selective cystic duct cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).2 Subsequent stenting for the treatment of acute cholecystitis (endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage, ET-GBD) was then reported by Tamada et. al. in 1991.3 Not to be outdone, the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was completed by Dr. Med Erich Mühe of Germany in 1985.4 More recently, with the expansion of interventional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), the first transmural EUS-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) was described by Dr. Baron and Dr. Topazian in 2007.5

The subsequent advent of lumen apposing metal stents (LAMS) has cemented EUS-GBD in the toolbox of treatment for benign gallbladder disease. Results of a recent prospective multicenter trial, with a Food and Drug Administration–approved protocol and investigational device exemption, have been published, opening the door for the expansion of FDA approved indications for this device.6

Benign gallbladder disease encompasses both polyps (benign and premalignant) and cholecystitis (acute/chronic, calculous/acalculous), in addition to others. The four management techniques (LC, PC, ET-GBD, and EUS-GBD) have filled integral niches in the management of these patients. Even gallbladder polyps have not been able to escape the reach of endoscopic approaches with the recent description of LAMS-assisted polypectomy as part of a gallbladder preserving strategy.7,8 While EUS-GBD also has been used for biliary decompression in the presence of a patent cystic duct and absence of cholecystitis, .9 Both of these techniques have gained wide recognition and/or guideline support for their use from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE).10,11 In addition, there is now one FDA-approved stent device for treatment of acute cholecystitis in patients unfit for surgery.

Techniques & Tips

ET-GBD

- During ERCP, after successful cannulation of the bile duct, attempted wire cannulation of the cystic duct is performed.

A cholangiogram, which clearly delineates the insertion of the cystic duct into the main bile duct, can enhance cannulation success. Rotatable fluoroscopy can facilitate identification.

- After anatomy is clear, wire access is often best achieved using a sphincterotome or stone retrieval (occlusion) balloon.

The balloon, once inflated, can be pulled downward to establish traction on the main bile duct, which can straighten the approach.

- After superficial wire engagement into the cystic duct, the accessory used can be slowly advanced into the cystic duct to stabilize the catheter and then navigate the valves of Heister to reach the gallbladder lumen.

Use of a sphincterotome, which directs toward the patient’s right (most often direction of cystic duct takeoff), is helpful. Angled guidewires are preferable. We often use a 0.035-inch, 260-cm angled hydrophilic wire (GLIDEWIRE; Terumo, Somerset, NJ) to overcome this challenging portion of ET-GBD.

If despite the above maneuvers the guidewire has failed to enter the cystic duct, cholangioscopy can be used to identify the orifice and/or stabilize deep wire cannulation. This is often cumbersome, time consuming, does not always produce success, and requires additional expertise.

- If a stone is encountered that cannot be extracted or traversed by a guidewire, cholangioscopy with electrohydraulic lithotripsy can be pursued.

- After the guidewire has entered the gallbladder, a 5 French or 7 French plastic double pigtail stent is placed. Typical lengths are 9-15 cm.

Some authors prefer to use two side-by-side plastic stents.12 This has been shown retrospectively to enhance the long term clinical success of ET-GBD but with additional technical difficulty.

- This stent can remain in place indefinitely and need not be exchanged, though it should be removed just prior to CCY if pursued. Alternatively, the surgeon can be alerted to its presence and, if comfortable, it can be removed intraoperatively.

EUS-GBD

- Use of fluoroscopy is optional but can enhance technical success in selected situations.

- Conversion, or internalization, of PC is reasonable and can enhance patient quality of life.13

- If the gallbladder wall is not in close apposition to the duodenal (or gastric) wall, consider measuring the distance.

We preferentially use 10-mm diameter by 10-mm saddle length LAMS for EUS-GBD, unless the above distance warrants use of a 15-mm by 15-mm LAMS (AXIOS, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA). If the distance is greater than 15 mm, consider searching for an alternative site, using a traditional biliary fully covered self-expandable metal stent (FCSEMS) for longer length, or converting to ET-GBD. Smaller diameter (8 mm) with an 8-mm saddle length can be used as well. The optimal diameter is unknown and also dependent on whether transluminal endoscopic diagnosis or therapy is a consideration.

- If there is difficulty locating the gallbladder, it may be decompressed or small (particularly if PC or a partial CCY has already been performed).

If a cholecystostomy tube is in place, instillation of sterile water via the tube can sometimes improve the target for LAMS placement, though caution should be made to not over-distend the gallbladder. ERCP with placement of a nasobiliary tube into the gallbladder can also serve this purpose and has been previously described.14

The gallbladder can be punctured with a 19-gauge FNA needle to instill sterile water and distend the gallbladder with the added benefit of being able to pass a guidewire, which may enhance procedural safety in difficult cases. However, success of this technique is contingent on fluid remaining within the gallbladder and not transiting out via the cystic duct. Expedient exchange of the FNA needle for the LAMS device may be necessary.

- Attempt to confirm location within the duodenum prior to puncture, as gastric origins can pose unique ramifications (i.e. potential for partial gastric outlet obstruction, obstruction of LAMS with food debris, etc.).

It can be easy to mistake an unintentional pre-pyloric position for a position within the duodenum since the working channel is behind (proximal to) the echoprobe.

- Turning off Doppler flow prior to advancement of the cautery enhanced LAMS can reduce obscurement of views on entry into the gallbladder. Lack of certainty about entry or misdeployment after presumed entry herald the most challenging aspect of EUS-GBD.

Utilization of a previously placed guidewire or advancement of one preloaded into the LAMS can aid in both enhancing confidence in location and assist with salvage maneuvers, if needed.

- After successful deployment of the LAMS we routinely place a double pigtail plastic stent through it (typically 7 French by 4 cm) to maintain patency. This may also prevent bleeding from the LAMS flange abrading the wall of either lumen.

- We routinely exchange the LAMS for two double pigtail plastic stents (typically 7 French by 4 cm) 4 weeks after initial placement especially when there is a more than modest residual stone burden (data in press). These plastic stents can remain in place indefinitely.

This exchange can be deferred if the patient is not expected to survive until the one-year anniversary of LAMS deployment. After one year the LAMS plastic covering may degrade and pose additional problems.15

LAMS Misdeployment Salvage Tips

- Salvage techniques can vary from simple to complex.

- If a wire is in place, it can be used to balloon or catheter dilate the tract and place a FCSEMS traversing the gallbladder and duodenal/gastric lumens. A similar approach can be used if the LAMS deployed on only one side (gallbladder or duodenum/stomach) and the other flange is within the peritoneum.

- The most challenging scenario to salvage is if the LAMS is misdeployed or becomes dislodged and no wire is present. This is why the use of a guidewire, even if preloaded into the LAMS and placement is freehand, is essential for EUS-GBD. A potential technique is to balloon dilate the duodenal/gastric defect and drive the endoscope into the peritoneum to reconnect that lumen to the gallbladder defect or LAMS, depending on the site of misdeployment. Doing so requires a high degree of commitment and skill and should not be done casually.

- If uncertainty remains or if misdeployment has occurred and salvage attempts have failed, consider closure of the duodenal/gastric defect and conversion to ET-GBD.

This may both treat the initial procedural indication and assist with what is essentially a large bile leak, which might also require percutaneous therapy for non-surgical management.

- For endoscopists with limited experience at salvage techniques, it is reasonable for the threshold for conversion to be low, assuming experience with and confidence in ET-GBD is high.

- If salvage is successful but ambiguity remains, consider obtaining a cholangiogram via the LAMS to confirm positioning and absence of leak.

Adverse Events

Both ET-GBD and EUS-GBD should be performed by an endoscopist comfortable with their techniques and the management of their adverse events (AEs). Rates for EUS-GBD AEs in patients at high risk for LC were reported in one international multicenter registry to be 15.3% with a 30-day mortality of 9.2%, with a significant predictor of AE being endoscopist experience less than 25 procedures.16 A meta-analysis also found an overall AE rate of 18.31%, with rates for perforation and stent related AEs (i.e. migration, occlusion, pneumoperitoneum) being 6.71% and 8.16%, respectively.17 For this reason, we recommend that patients with cholecystitis who are deemed to be poor surgical candidates be transferred to a tertiary referral center with expertise in these approaches. Rates of AEs for ET-GBD are similar to that for standard ERCP, with reported ranges of 5%-10.3%.10

Comparisons Between Techniques

The decision on which technique to utilize for endoscopic management of cholecystitis or symptomatic cholelithiasis depends first and foremost on the expertise and comfort level of the endoscopist. Given the additional training that an advanced endoscopist needs to perform EUS-GBD, combined with the perhaps slightly higher AE rate and permanency of endoscopic cholecystostomy, it is reasonable to proceed with a trial of ET-GBD if confidence is insufficient. However, ET-GBD can certainly be more technically challenging and less effective than EUS-GBD, with lower reported technical and clinical success rates (technical 85.3% vs 93.0%, clinical 95.2% vs 97.3%).18 Despite this, the rate of recurrence of cholecystitis is similar between ET-GBD and EUS-GBD (4.6% vs 4.2%).19 As stated above in the Techniques & Tips section, some authors utilize two plastic stents for ET-GBD for this purpose, though with increased technical difficulty. It is important to remember that these numbers, when paired with AE rates, represent the achievements of expert endoscopists.

Discussion with your surgery team is important when deciding modality. If the patient is felt to be a potential candidate for CCY, and EUS-GBD is not being used as a destination therapy, the surgeon may prefer ET-GBD. EUS-GBD may enhance the difficulty of CCY, though at least one study demonstrated that this was no different than PC with similar rates of conversion from LC to open CCY.20 This conversation is most critical for patients who are potential liver transplant candidates. For patients where this is not a consideration there is some evidence to suggest equivalency between LC and EUS-GBD, though certainly EUS-GBD has not yet supplanted LC as the treatment of choice.21

While there may eventually be a shift towards EUS-GBD instead of LC in certain patient groups, what is clearer are the advantages of EUS-GBD over PC. One recent meta-analysis revealed that EUS-GBD has significantly favorable odds of overall adverse events (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18-1.00), shorter hospital stay (2.76 less days, 95% CI 0.31-5.20 less days), reinterventions (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02-0.98), and unplanned readmissions (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03-0.70) compared to PC.22 Beyond the data, though, are the emotional and psychological impacts an external drain can have on a patient.

Conclusion

When expertise is available, endoscopic treatment of benign gallbladder disease has a definite role but should be undertaken only by those with the experience and skill to safely do so. Decision to proceed, especially with EUS-GBD, should be accompanied by conversation and collaboration with surgical teams. If a patient is under consideration for PC instead of LC, it may be worthwhile to seek consultation with a local center with expertise in EUS-GBD or ET-GBD. The adoption of these techniques is part of the paradigm shift, seen broadly throughout medicine, towards minimally invasive interventions, particularly in advanced endoscopy.

Dr. Gilman (X @a_gilman) and Dr. Baron (X @EndoTx) are with the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. Dr. Gilman has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Baron is a consultant and speaker for Ambu, Boston Scientific, Cook Endoscopy, Medtronic, Olympus America, and W.L. Gore.

References

1. Radder RW. Ultrasonically guided percutaneous catheter drainage for gallbladder empyema. Diagn Imaging. 1980;49:330-333.

2. Kozarek RA. Selective cannulation of the cystic duct at time of ERCP. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:37-40.

3. Tamada K et al. Efficacy of endoscopic retrograde cholecystoendoprosthesis (ERCCE) for cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 1991;23:2-3.

4. Reynolds W. The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2001;5:89-94.

5. Baron TH, Topazian MD. Endoscopic transduodenal drainage of the gallbladder: Implications for endoluminal treatment of gallbladder disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Apr;65(4):735-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.07.041.

6. Irani SS et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transluminal gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis: A prospective multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2023 Sep 1;278(3):e556-e562. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005784.

7. Shen Y et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholecystostomy for resection of gallbladder polyps with lumen-apposing metal stent. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Oct 23;99(43):e22903. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022903.

8. Pang H et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder endoscopic mucosal resection: A pilot porcine study. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2023 Feb;32(1):24-32. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2022.2153228.

9. Imai H et al. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage for rescue treatment of malignant distal biliary obstruction after unsuccessful ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jul;84(1):147-51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.12.024.

10. Saumoy M et al. Endoscopic therapies for gallbladder drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Oct;94(4):671-84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.05.031.

11. Van der Merwe SW et al. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022 Feb;54(2):185-205. doi: 10.1055/a-1717-1391.

12. Storm AC et al. Transpapillary gallbladder stent placement for long-term therapy of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Oct;94(4):742-8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.025.

13. James TW, Baron TH. Converting percutaneous gallbladder drainage to internal drainage using EUS-guided therapy: A review of current practices and procedures. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018 Mar-Apr;7(2):93-6. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_110_17.

14. James TW, Baron TH. Transpapillary nasocystic tube placement to allow gallbladder distention for EUS-guided cholecystoduodenostomy. VideoGIE. 2019 Dec;4(12):561-2. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2019.08.009.

15. Gilman AJ, Baron TH. Delamination of a lumen-apposing metal stent with tissue ingrowth and stent-in-stent removal. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Sep;98(3):451-3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.04.2087.

16. Teoh AY et al. Outcomes of an international multicenter registry on EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in patients at high risk for cholecystectomy. Endosc Int Open. 2019 Aug;7(8):E964-E973. doi: 10.1055/a-0915-2098.

17. Kalva NR et al. Efficacy and safety of lumen apposing self-expandable metal stents for EUS guided cholecystostomy: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:7070961. doi: 10.1155/2018/7070961.

18. Khan MA et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis: Is it better than percutaneous gallbladder drainage? Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Jan;85(1):76-87 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.06.032.

19. Mohan BP et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage, transpapillary drainage, or percutaneous drainage in high risk acute cholecystitis patients: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2020 Feb;52(2):96-106. doi: 10.1055/a-1020-3932.

20. Jang JW et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012 Apr;142(4):805-11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.051.

21. Teoh AYB et al. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a propensity score analysis with 1-year follow-up data. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Mar;93(3):577-83. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.066.

22. Luk SW et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage versus percutaneous cholecystostomy for high risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019 Aug;51(8):722-32. doi: 10.1055/a-0929-6603.

February 2024 – ICYMI

Gastroenterology

October 2023

El-Salhy M et al. Efficacy of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome at 3 Years After Transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):982-994.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.020. Epub 2022 Jun 14. PMID: 35709830.

Bajaj JS and Nagy LE. Natural History of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: Understanding the Changing Landscape of Pathophysiology and Patient Care. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):840-851. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.031. Epub 2022 May 19. PMID: 35598629; PMCID: PMC9509416.

Lo CH et al. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):852-861.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.067. Epub 2022 Jul 1. PMID: 35788344; PMCID: PMC9509450.

November 2023

Khoshiwal AM et al. The Tissue Systems Pathology Test Outperforms Pathology Review in Risk Stratifying Patients With Low-Grade Dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2023 Nov;165(5):1168-1179.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.029. Epub 2023 Aug 30. PMID: 37657759.

Chen YI et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage of First Intent With a Lumen-Apposing Metal Stent vs Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Study (ELEMENT Trial). Gastroenterology. 2023 Nov;165(5):1249-1261.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.024. Epub 2023 Aug 6. PMID: 37549753.

December 2023

Almario CV et al. Prevalence and Burden of Illness of Rome IV Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the United States: Results From a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Gastroenterology. 2023 Dec;165(6):1475-1487. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.010. Epub 2023 Aug 16. PMID: 37595647.

Koopmann BDM et al. The Natural Disease Course of Pancreatic Cyst-Associated Neoplasia, Dysplasia, and Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Results of a Microsimulation Model. Gastroenterology. 2023 Dec;165(6):1522-1532. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.027. Epub 2023 Aug 24. PMID: 37633497.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

October 2023

Jung DH et al. Comparison of a Polysaccharide Hemostatic Powder and Conventional Therapy for Peptic Ulcer Bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Oct;21(11):2844-2253.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.02.031. Epub 2023 Mar 10. PMID: 36906081.

Liang PS et al. Blood Test Increases Colorectal Cancer Screening in Persons Who Declined Colonoscopy and Fecal Immunochemical Test: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Oct;21(11):2951-2957.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.036. Epub 2023 Apr 8. PMID: 37037262; PMCID: PMC10523873.

November 2023

Li YK et al. Risk of Postcolonoscopy Thromboembolic Events: A Real-World Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov;21(12):3051-3059.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.021. Epub 2022 Sep 24. PMID: 36167228.

Tome J et al. Bile Acid Sequestrants in Microscopic Colitis: Clinical Outcomes and Utility of Bile Acid Testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov;21(12):3125-3131.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.031. Epub 2023 May 10. PMID: 37172800.

Berry SK et al. A Randomized Parallel-group Study of Digital Gut-directed Hypnotherapy vs Muscle Relaxation for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov;21(12):3152-3159.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.06.015. Epub 2023 Jun 28. PMID: 37391055.

December 2023

Kanwal F et al. Risk Stratification Model for Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Dec;21(13):3296-3304.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.019. Epub 2023 Apr 30. PMID: 37390101; PMCID: PMC10661677.

Forss A et al. Patients With Microscopic Colitis Are at Higher Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events: A Matched Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Dec;21(13):3356-3364.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.05.014. Epub 2023 May 26. PMID: 37245713.

Zheng T et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Efficacy and Safety of Cannabidiol in Idiopathic and Diabetic Gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Dec;21(13):3405-3414.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.07.008. Epub 2023 Jul 22. PMID: 37482172.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Rengarajan A and Aadam A. Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) and Its Use in Esophageal Dysmotility. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Dec 16. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.12.004.

Wang D et al. Sphincterotomy vs Sham Procedure for Pain Relief in Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Nov 7. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.10.003

Gastro Hep Advances

Gregory MH et al. Short Bowel Syndrome: Transition of Pediatric Patients to Adult Gastroenterology Care. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023 Sep 8. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.09.006.

Viser AC et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients in the Ambulatory Setting Commonly Screen Positive for Malnutrition. Gastro Hep Advances. 2023 Nov 16. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.11.007.

Gastroenterology

October 2023

El-Salhy M et al. Efficacy of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome at 3 Years After Transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):982-994.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.020. Epub 2022 Jun 14. PMID: 35709830.

Bajaj JS and Nagy LE. Natural History of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: Understanding the Changing Landscape of Pathophysiology and Patient Care. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):840-851. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.031. Epub 2022 May 19. PMID: 35598629; PMCID: PMC9509416.

Lo CH et al. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. Gastroenterology. 2022 Oct;163(4):852-861.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.067. Epub 2022 Jul 1. PMID: 35788344; PMCID: PMC9509450.

November 2023

Khoshiwal AM et al. The Tissue Systems Pathology Test Outperforms Pathology Review in Risk Stratifying Patients With Low-Grade Dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2023 Nov;165(5):1168-1179.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.07.029. Epub 2023 Aug 30. PMID: 37657759.