User login

Neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships

“So you want to be a gastroenterologist? What do you really want to do?” This is not an uncommon question that a trainee is faced with when progressing through residency and gastroenterology fellowship.

The list of possibilities includes general gastroenterology, advanced endoscopy, transplant hepatology, and neurogastroenterology and motility. From there, each subspecialty can be broken down further into organ system or a specific procedure of interest. Another necessary question is whether to pursue a career in academics or private practice. The first is for the resident who is interested in gaining experience in gastroenterology prior to starting a general gastroenterology fellowship (there are two programs that currently allow for this pathway). The other track is for those who have completed a general gastroenterology fellowship and are looking to enhance their academic careers by pursuing additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility.

There is currently a need for gastroenterologists interested in neurogastroenterology and motility. Among the most common diagnoses in an ambulatory setting, based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) coding, are abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, nausea and vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and dysphagia.1,2 While many fellows are exposed to a wide range of motility patients during general gastroenterology fellowship, there is typically not a sufficient amount of training to attain “level 2” proficiency.2,3 In an effort to help standardize training there are recommended thresholds established and advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility can help fellows to attain that proficiency.2,3 The extra year can also help you prepare to run a motility lab, train nurses, establish lab protocols and quality standards, and manage referrals, which are important skills as a neurogastroenterology and motility specialist.

Types of programs

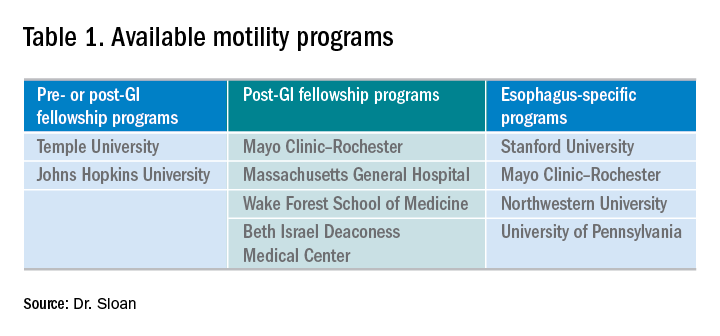

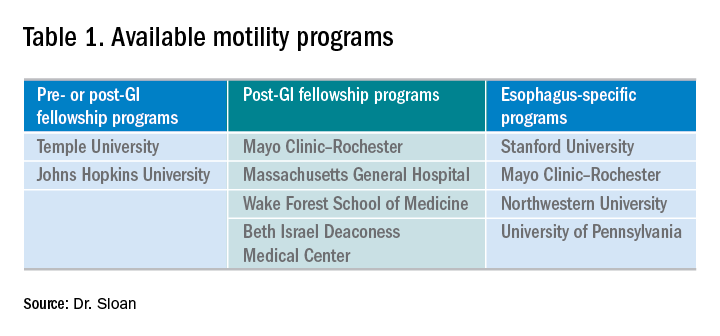

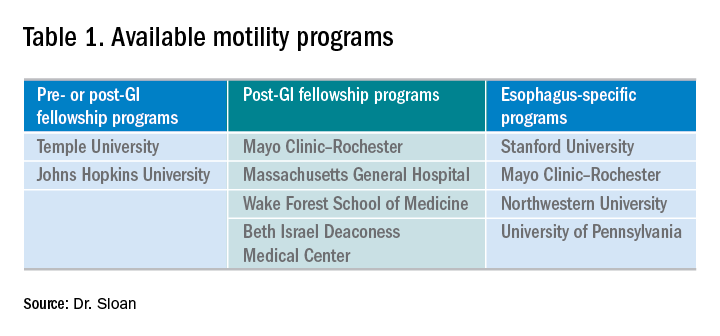

There are several different types of motility programs available. As mentioned previously, some programs afford individuals an opportunity to gain additional experience in gastroenterology before progressing to general gastroenterology fellowship. There are two programs that offer a 1-year fellowship in neurogastroenterology and motility, both prior to or after a general gastroenterology fellowship. Four programs offer 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships only after a general gastroenterology fellowship. While the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships cover esophageal motility, there are four programs that specifically focus solely on the esophagus (Table 1).

In addition to pursuing an extra year of training, interested gastroenterology fellows may choose to explore a 1-month Clinical Training Program sponsored by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) at 1 of 10 centers.

Where to find programs

Currently, there is not a singular list of neurogastroenterology and motility programs available for review as you might find with an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) residency or fellowship. At present, the best way to identify the available programs is to search online. Motivation to select a specific program may be related to individual preference and can include geography and department expertise; this ultimately helps to create a focused list. With regard to the ANMS 1-month Clinical Training Program, the list of available programs is available on the society’s website and is for fellows currently in training who wish to incorporate neurogastroenterology and motility into their general GI fellowship.

How to apply

Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility is currently a non-ACGME pathway and does not offer a match process for its applicants. After identifying a program of interest, one can find specific instructions on how to apply at the programs’ websites. Typically the process involves reaching out to the program director, writing a letter of interest or personal statement, providing letters of recommendation, and interviewing. Each program has some variability in what is required and attention should be paid to the criteria listed on the specific website.

My experience

I was fortunate to have substantial exposure to esophageal motility in my general gastroenterology fellowship. Gaining this experience was invaluable and laid the foundation for my interest in neurogastroenterology and motility, and, specifically, esophageal dysmotility. My interest in neurogastroenterology and motility then collided with my desire to pursue a career in academics. Knowing the general trajectory for my future career, I began exploring the possibility of undergoing an additional 1-year fellowship early in my second year of GI fellowship. I worked closely with my program director to help define my future goals and to identify available places that would help me attain those goals. While I continued to have an interest in the esophagus, additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility would broaden my understanding and enhance my ability to manage complex patients and perform research at a tertiary care center. I investigated the different neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship programs online and followed the online application instructions. Utilizing national gastroenterology society conferences as networking opportunities, I was able to meet with the program director of my current neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship. In my third year of general gastroenterology fellowship I formally interviewed with the motility group at Johns Hopkins and was later accepted into the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship program.

Now, nearing the end of my 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship, I reflect on my extremely positive experience. Throughout the course of the year I have been able to work with multiple GI providers — each with their own area of expertise within the field. There has been a profound exposure to a wide variety of patients with a spectrum of motility conditions covering the entire GI tract. There has been ample opportunity to read motility studies with the guidance and support of the motility faculty to further enhance my skills. The additional year has broadened my exposure to, and the management of, the biopsychosocial aspect of this specific patient population. In line with that, I have had the ability to grow with regard to my use of pharmacology and recognize which symptom might benefit from a particular neuromodulator. An emphasis was also placed on learning the gut-brain axis, and, through multidisciplinary clinics, I worked closely with other disciplines such as psychiatry and GI clinical psychology. Furthermore, the additional year has allowed me to be involved in several research projects within neurogastroenterology and motility that will undoubtedly enhance my future career.

Conclusion

Deciding to pursue an additional year in neurogastroenterology and motility has been one that has helped to give a solid direction to my budding career. It has left me confident in managing this diverse and complex patient population and has helped prepare me for a career in academic gastroenterology. For those who are interested in academic neurogastroenterology and motility, an additional fellowship can help define you as a gastroenterologist and help you to pursue the career of your dreams.

Dr. Sloan is a clinical instructor in the division of gastroenterology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

References

1. Peery A. et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731-41.e3.

2. Rao S., Parkman H. Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology 2015;148:881-5.

3. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The gastroenterology core curriculum, third edition. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2012-18.

“So you want to be a gastroenterologist? What do you really want to do?” This is not an uncommon question that a trainee is faced with when progressing through residency and gastroenterology fellowship.

The list of possibilities includes general gastroenterology, advanced endoscopy, transplant hepatology, and neurogastroenterology and motility. From there, each subspecialty can be broken down further into organ system or a specific procedure of interest. Another necessary question is whether to pursue a career in academics or private practice. The first is for the resident who is interested in gaining experience in gastroenterology prior to starting a general gastroenterology fellowship (there are two programs that currently allow for this pathway). The other track is for those who have completed a general gastroenterology fellowship and are looking to enhance their academic careers by pursuing additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility.

There is currently a need for gastroenterologists interested in neurogastroenterology and motility. Among the most common diagnoses in an ambulatory setting, based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) coding, are abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, nausea and vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and dysphagia.1,2 While many fellows are exposed to a wide range of motility patients during general gastroenterology fellowship, there is typically not a sufficient amount of training to attain “level 2” proficiency.2,3 In an effort to help standardize training there are recommended thresholds established and advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility can help fellows to attain that proficiency.2,3 The extra year can also help you prepare to run a motility lab, train nurses, establish lab protocols and quality standards, and manage referrals, which are important skills as a neurogastroenterology and motility specialist.

Types of programs

There are several different types of motility programs available. As mentioned previously, some programs afford individuals an opportunity to gain additional experience in gastroenterology before progressing to general gastroenterology fellowship. There are two programs that offer a 1-year fellowship in neurogastroenterology and motility, both prior to or after a general gastroenterology fellowship. Four programs offer 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships only after a general gastroenterology fellowship. While the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships cover esophageal motility, there are four programs that specifically focus solely on the esophagus (Table 1).

In addition to pursuing an extra year of training, interested gastroenterology fellows may choose to explore a 1-month Clinical Training Program sponsored by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) at 1 of 10 centers.

Where to find programs

Currently, there is not a singular list of neurogastroenterology and motility programs available for review as you might find with an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) residency or fellowship. At present, the best way to identify the available programs is to search online. Motivation to select a specific program may be related to individual preference and can include geography and department expertise; this ultimately helps to create a focused list. With regard to the ANMS 1-month Clinical Training Program, the list of available programs is available on the society’s website and is for fellows currently in training who wish to incorporate neurogastroenterology and motility into their general GI fellowship.

How to apply

Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility is currently a non-ACGME pathway and does not offer a match process for its applicants. After identifying a program of interest, one can find specific instructions on how to apply at the programs’ websites. Typically the process involves reaching out to the program director, writing a letter of interest or personal statement, providing letters of recommendation, and interviewing. Each program has some variability in what is required and attention should be paid to the criteria listed on the specific website.

My experience

I was fortunate to have substantial exposure to esophageal motility in my general gastroenterology fellowship. Gaining this experience was invaluable and laid the foundation for my interest in neurogastroenterology and motility, and, specifically, esophageal dysmotility. My interest in neurogastroenterology and motility then collided with my desire to pursue a career in academics. Knowing the general trajectory for my future career, I began exploring the possibility of undergoing an additional 1-year fellowship early in my second year of GI fellowship. I worked closely with my program director to help define my future goals and to identify available places that would help me attain those goals. While I continued to have an interest in the esophagus, additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility would broaden my understanding and enhance my ability to manage complex patients and perform research at a tertiary care center. I investigated the different neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship programs online and followed the online application instructions. Utilizing national gastroenterology society conferences as networking opportunities, I was able to meet with the program director of my current neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship. In my third year of general gastroenterology fellowship I formally interviewed with the motility group at Johns Hopkins and was later accepted into the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship program.

Now, nearing the end of my 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship, I reflect on my extremely positive experience. Throughout the course of the year I have been able to work with multiple GI providers — each with their own area of expertise within the field. There has been a profound exposure to a wide variety of patients with a spectrum of motility conditions covering the entire GI tract. There has been ample opportunity to read motility studies with the guidance and support of the motility faculty to further enhance my skills. The additional year has broadened my exposure to, and the management of, the biopsychosocial aspect of this specific patient population. In line with that, I have had the ability to grow with regard to my use of pharmacology and recognize which symptom might benefit from a particular neuromodulator. An emphasis was also placed on learning the gut-brain axis, and, through multidisciplinary clinics, I worked closely with other disciplines such as psychiatry and GI clinical psychology. Furthermore, the additional year has allowed me to be involved in several research projects within neurogastroenterology and motility that will undoubtedly enhance my future career.

Conclusion

Deciding to pursue an additional year in neurogastroenterology and motility has been one that has helped to give a solid direction to my budding career. It has left me confident in managing this diverse and complex patient population and has helped prepare me for a career in academic gastroenterology. For those who are interested in academic neurogastroenterology and motility, an additional fellowship can help define you as a gastroenterologist and help you to pursue the career of your dreams.

Dr. Sloan is a clinical instructor in the division of gastroenterology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

References

1. Peery A. et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731-41.e3.

2. Rao S., Parkman H. Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology 2015;148:881-5.

3. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The gastroenterology core curriculum, third edition. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2012-18.

“So you want to be a gastroenterologist? What do you really want to do?” This is not an uncommon question that a trainee is faced with when progressing through residency and gastroenterology fellowship.

The list of possibilities includes general gastroenterology, advanced endoscopy, transplant hepatology, and neurogastroenterology and motility. From there, each subspecialty can be broken down further into organ system or a specific procedure of interest. Another necessary question is whether to pursue a career in academics or private practice. The first is for the resident who is interested in gaining experience in gastroenterology prior to starting a general gastroenterology fellowship (there are two programs that currently allow for this pathway). The other track is for those who have completed a general gastroenterology fellowship and are looking to enhance their academic careers by pursuing additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility.

There is currently a need for gastroenterologists interested in neurogastroenterology and motility. Among the most common diagnoses in an ambulatory setting, based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) coding, are abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, nausea and vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and dysphagia.1,2 While many fellows are exposed to a wide range of motility patients during general gastroenterology fellowship, there is typically not a sufficient amount of training to attain “level 2” proficiency.2,3 In an effort to help standardize training there are recommended thresholds established and advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility can help fellows to attain that proficiency.2,3 The extra year can also help you prepare to run a motility lab, train nurses, establish lab protocols and quality standards, and manage referrals, which are important skills as a neurogastroenterology and motility specialist.

Types of programs

There are several different types of motility programs available. As mentioned previously, some programs afford individuals an opportunity to gain additional experience in gastroenterology before progressing to general gastroenterology fellowship. There are two programs that offer a 1-year fellowship in neurogastroenterology and motility, both prior to or after a general gastroenterology fellowship. Four programs offer 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships only after a general gastroenterology fellowship. While the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowships cover esophageal motility, there are four programs that specifically focus solely on the esophagus (Table 1).

In addition to pursuing an extra year of training, interested gastroenterology fellows may choose to explore a 1-month Clinical Training Program sponsored by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) at 1 of 10 centers.

Where to find programs

Currently, there is not a singular list of neurogastroenterology and motility programs available for review as you might find with an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) residency or fellowship. At present, the best way to identify the available programs is to search online. Motivation to select a specific program may be related to individual preference and can include geography and department expertise; this ultimately helps to create a focused list. With regard to the ANMS 1-month Clinical Training Program, the list of available programs is available on the society’s website and is for fellows currently in training who wish to incorporate neurogastroenterology and motility into their general GI fellowship.

How to apply

Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and motility is currently a non-ACGME pathway and does not offer a match process for its applicants. After identifying a program of interest, one can find specific instructions on how to apply at the programs’ websites. Typically the process involves reaching out to the program director, writing a letter of interest or personal statement, providing letters of recommendation, and interviewing. Each program has some variability in what is required and attention should be paid to the criteria listed on the specific website.

My experience

I was fortunate to have substantial exposure to esophageal motility in my general gastroenterology fellowship. Gaining this experience was invaluable and laid the foundation for my interest in neurogastroenterology and motility, and, specifically, esophageal dysmotility. My interest in neurogastroenterology and motility then collided with my desire to pursue a career in academics. Knowing the general trajectory for my future career, I began exploring the possibility of undergoing an additional 1-year fellowship early in my second year of GI fellowship. I worked closely with my program director to help define my future goals and to identify available places that would help me attain those goals. While I continued to have an interest in the esophagus, additional training in neurogastroenterology and motility would broaden my understanding and enhance my ability to manage complex patients and perform research at a tertiary care center. I investigated the different neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship programs online and followed the online application instructions. Utilizing national gastroenterology society conferences as networking opportunities, I was able to meet with the program director of my current neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship. In my third year of general gastroenterology fellowship I formally interviewed with the motility group at Johns Hopkins and was later accepted into the neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship program.

Now, nearing the end of my 1-year neurogastroenterology and motility fellowship, I reflect on my extremely positive experience. Throughout the course of the year I have been able to work with multiple GI providers — each with their own area of expertise within the field. There has been a profound exposure to a wide variety of patients with a spectrum of motility conditions covering the entire GI tract. There has been ample opportunity to read motility studies with the guidance and support of the motility faculty to further enhance my skills. The additional year has broadened my exposure to, and the management of, the biopsychosocial aspect of this specific patient population. In line with that, I have had the ability to grow with regard to my use of pharmacology and recognize which symptom might benefit from a particular neuromodulator. An emphasis was also placed on learning the gut-brain axis, and, through multidisciplinary clinics, I worked closely with other disciplines such as psychiatry and GI clinical psychology. Furthermore, the additional year has allowed me to be involved in several research projects within neurogastroenterology and motility that will undoubtedly enhance my future career.

Conclusion

Deciding to pursue an additional year in neurogastroenterology and motility has been one that has helped to give a solid direction to my budding career. It has left me confident in managing this diverse and complex patient population and has helped prepare me for a career in academic gastroenterology. For those who are interested in academic neurogastroenterology and motility, an additional fellowship can help define you as a gastroenterologist and help you to pursue the career of your dreams.

Dr. Sloan is a clinical instructor in the division of gastroenterology at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

References

1. Peery A. et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731-41.e3.

2. Rao S., Parkman H. Advanced training in neurogastroenterology and gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology 2015;148:881-5.

3. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The gastroenterology core curriculum, third edition. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2012-18.

AGA Editorial Fellowship: Three lasting lessons

As a first-year gastroenterology fellow, banding my first patient with a variceal bleed was an exciting – but also stress-provoking – event. What if I banded incorrectly and caused more bleeding? With a successful band, a patient’s hemorrhagic shock is now controlled, hemodynamics improved, and euphoria takes over. Now, in my third year of a gastroenterology fellowship but my first year of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Editorial Fellowship, preparing to present the first manuscript that I handled to the Board of Editors at our weekly meeting has now induced the same excitement and need for the same level of dedication. Have I researched the foundational literature that this current manuscript was built on? What is the trajectory of this research and will this project be interesting to our readers and lead to breakthroughs in the field?

Gastroenterology is the premier flagship journal of the AGA and, in this Editorial Fellowship, I was selected to spend a fully immersive 1-year experience working on all aspects of this journal. In its second year of inception, I echo Dr. Eric Shah’s insight into the transformative and immersive nature of this fellowship.1 In this role, I have made three developments, and each one has left me with a valuable lesson.

Mentorship

My first development was as a direct mentee under the leadership of the two editors in chief Richard Peek, MD, and Douglas Corley, MD, and associate editor John Inadomi, MD. In this role, I reviewed submitted manuscripts regarding outcome data of oncologic studies in the fields of colon, esophageal, and gastric cancer. I served as a reviewer for submitted manuscripts and discussed the impact, novelty, and decision for publication with the Board of Editors. In our weekly meetings, the associate editors discussed manuscripts that needed further review prior to acceptance, revision, or rejection. A few themes underpinned the discussion of these manuscripts:

- Is this science reproducible and is there scientific rigor for study design, validity, and analysis?

- How does this manuscript add to the current state of the literature?

- What is the trajectory of this research field?

- How will this manuscript lead to breakthroughs in this field?

- Are the advancements in this manuscript likely to lead to paradigm shifts in the field in its approach, design, or findings?

I also was fortunate to meet leaders in the field, including working daily in person with multiple members of the Board of Editors at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., as well as visiting professors, including Dr. Corley, Linda Rabeneck, MD, and T. Jake Liang, MD, who not only spoke on their scientific inquiries but also about their transitional path from gastroenterology fellows to pioneers in their respective fields. From these lessons, I have learned the scientific rigor of manuscript review for Gastroenterology and how to approach modern challenges in our field to directly improve patient care.

AGA’s commitment to early-career investigators

The Editorial Fellowship allowed me to expand a traditional third-year gastroenterology fellowship to dive deep into the intense path to get a manuscript published in Gastroenterology. Whereas 1 year prior, I had found dilating a complete esophageal stricture difficult, I now found myself learning to master clinical trial design, applying modern techniques of artificial intelligence, understanding organoid development, and navigating the impact of the microbiome. I was fortunate to be selected for Vanderbilt’s Master’s in Science in Clinical Investigation, which allowed me to apply my education not only to my own research but also to synergistically understand and deconstruct new submissions ranging from modern statistics with Bayesian modeling to analysis of large genetic data. All of this was built in the supportive framework of my mentoring committee.

As a fellow, I am inspired to see the multicenter, international collaboration to answer important questions in our field. Leveraging large databases and the expertise of multiple investigators, breakthroughs were made because of the collaborative nature of the science. This also was felt in the review process, where experts generously reviewed manuscripts to enhance the quality of the submission in order to advance knowledge in the field. Reading hundreds of these reviews this year has allowed me to refocus my current research studies and improve the way I write my current reviews. In the spirit of reproducible science and challenging the precision of study design, I was impressed by the time, effort, and dedication reviewers from our field spent to help improve the literature. Dr. Peek and Dr. Corley, our editors in chief, committed their time in discussing my innovations and critiques and displayed their level of interest in the opinions of early-career investigators and fostering the next generation of scientists and practitioners. In this lesson, I was invigorated by the depth of AGA opportunities for fellows and junior faculty in education, research, and involvement.

Self-reflection

Having the honor and privilege to review manuscripts upon submission also increased my critical view of my current practices. I now question the level of evidence for which current patient care practices are based, which allows me to better understand the research areas that need increased attention to improve the quality of our guidelines and evidence. For motivated fellows interested in a path of academic medicine, I would strongly advise applying for this prestigious fellowship. In no other training process could I have learned such a breadth of scientific skills and directly apply them to my patient care, my research, and my role as an educator. Furthermore, I was able to contribute to the reviewing and editing process, which allowed me to directly contribute to the field at an early stage of my career. In this final lesson, I exit this impactful Editorial Fellowship in self-reflection. I leave this fellowship humbled – by you – the reader who continues to learn to improve your patient care, the scientist as she works tirelessly to answer questions and contribute to the literature, the gastroenterology community for their willingness to teach and mentor fellows and early-career investigators and practitioners, and the patients who remind us that we all have a shared mission to advance scientific knowledge to improve patient care.

Dr. Naik is a gastroenterology fellow in the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Reference

1. Shah ED. Skills acquired during my 1-year AGA Editorial Fellowship. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1563.

As a first-year gastroenterology fellow, banding my first patient with a variceal bleed was an exciting – but also stress-provoking – event. What if I banded incorrectly and caused more bleeding? With a successful band, a patient’s hemorrhagic shock is now controlled, hemodynamics improved, and euphoria takes over. Now, in my third year of a gastroenterology fellowship but my first year of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Editorial Fellowship, preparing to present the first manuscript that I handled to the Board of Editors at our weekly meeting has now induced the same excitement and need for the same level of dedication. Have I researched the foundational literature that this current manuscript was built on? What is the trajectory of this research and will this project be interesting to our readers and lead to breakthroughs in the field?

Gastroenterology is the premier flagship journal of the AGA and, in this Editorial Fellowship, I was selected to spend a fully immersive 1-year experience working on all aspects of this journal. In its second year of inception, I echo Dr. Eric Shah’s insight into the transformative and immersive nature of this fellowship.1 In this role, I have made three developments, and each one has left me with a valuable lesson.

Mentorship

My first development was as a direct mentee under the leadership of the two editors in chief Richard Peek, MD, and Douglas Corley, MD, and associate editor John Inadomi, MD. In this role, I reviewed submitted manuscripts regarding outcome data of oncologic studies in the fields of colon, esophageal, and gastric cancer. I served as a reviewer for submitted manuscripts and discussed the impact, novelty, and decision for publication with the Board of Editors. In our weekly meetings, the associate editors discussed manuscripts that needed further review prior to acceptance, revision, or rejection. A few themes underpinned the discussion of these manuscripts:

- Is this science reproducible and is there scientific rigor for study design, validity, and analysis?

- How does this manuscript add to the current state of the literature?

- What is the trajectory of this research field?

- How will this manuscript lead to breakthroughs in this field?

- Are the advancements in this manuscript likely to lead to paradigm shifts in the field in its approach, design, or findings?

I also was fortunate to meet leaders in the field, including working daily in person with multiple members of the Board of Editors at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., as well as visiting professors, including Dr. Corley, Linda Rabeneck, MD, and T. Jake Liang, MD, who not only spoke on their scientific inquiries but also about their transitional path from gastroenterology fellows to pioneers in their respective fields. From these lessons, I have learned the scientific rigor of manuscript review for Gastroenterology and how to approach modern challenges in our field to directly improve patient care.

AGA’s commitment to early-career investigators

The Editorial Fellowship allowed me to expand a traditional third-year gastroenterology fellowship to dive deep into the intense path to get a manuscript published in Gastroenterology. Whereas 1 year prior, I had found dilating a complete esophageal stricture difficult, I now found myself learning to master clinical trial design, applying modern techniques of artificial intelligence, understanding organoid development, and navigating the impact of the microbiome. I was fortunate to be selected for Vanderbilt’s Master’s in Science in Clinical Investigation, which allowed me to apply my education not only to my own research but also to synergistically understand and deconstruct new submissions ranging from modern statistics with Bayesian modeling to analysis of large genetic data. All of this was built in the supportive framework of my mentoring committee.

As a fellow, I am inspired to see the multicenter, international collaboration to answer important questions in our field. Leveraging large databases and the expertise of multiple investigators, breakthroughs were made because of the collaborative nature of the science. This also was felt in the review process, where experts generously reviewed manuscripts to enhance the quality of the submission in order to advance knowledge in the field. Reading hundreds of these reviews this year has allowed me to refocus my current research studies and improve the way I write my current reviews. In the spirit of reproducible science and challenging the precision of study design, I was impressed by the time, effort, and dedication reviewers from our field spent to help improve the literature. Dr. Peek and Dr. Corley, our editors in chief, committed their time in discussing my innovations and critiques and displayed their level of interest in the opinions of early-career investigators and fostering the next generation of scientists and practitioners. In this lesson, I was invigorated by the depth of AGA opportunities for fellows and junior faculty in education, research, and involvement.

Self-reflection

Having the honor and privilege to review manuscripts upon submission also increased my critical view of my current practices. I now question the level of evidence for which current patient care practices are based, which allows me to better understand the research areas that need increased attention to improve the quality of our guidelines and evidence. For motivated fellows interested in a path of academic medicine, I would strongly advise applying for this prestigious fellowship. In no other training process could I have learned such a breadth of scientific skills and directly apply them to my patient care, my research, and my role as an educator. Furthermore, I was able to contribute to the reviewing and editing process, which allowed me to directly contribute to the field at an early stage of my career. In this final lesson, I exit this impactful Editorial Fellowship in self-reflection. I leave this fellowship humbled – by you – the reader who continues to learn to improve your patient care, the scientist as she works tirelessly to answer questions and contribute to the literature, the gastroenterology community for their willingness to teach and mentor fellows and early-career investigators and practitioners, and the patients who remind us that we all have a shared mission to advance scientific knowledge to improve patient care.

Dr. Naik is a gastroenterology fellow in the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Reference

1. Shah ED. Skills acquired during my 1-year AGA Editorial Fellowship. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1563.

As a first-year gastroenterology fellow, banding my first patient with a variceal bleed was an exciting – but also stress-provoking – event. What if I banded incorrectly and caused more bleeding? With a successful band, a patient’s hemorrhagic shock is now controlled, hemodynamics improved, and euphoria takes over. Now, in my third year of a gastroenterology fellowship but my first year of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Editorial Fellowship, preparing to present the first manuscript that I handled to the Board of Editors at our weekly meeting has now induced the same excitement and need for the same level of dedication. Have I researched the foundational literature that this current manuscript was built on? What is the trajectory of this research and will this project be interesting to our readers and lead to breakthroughs in the field?

Gastroenterology is the premier flagship journal of the AGA and, in this Editorial Fellowship, I was selected to spend a fully immersive 1-year experience working on all aspects of this journal. In its second year of inception, I echo Dr. Eric Shah’s insight into the transformative and immersive nature of this fellowship.1 In this role, I have made three developments, and each one has left me with a valuable lesson.

Mentorship

My first development was as a direct mentee under the leadership of the two editors in chief Richard Peek, MD, and Douglas Corley, MD, and associate editor John Inadomi, MD. In this role, I reviewed submitted manuscripts regarding outcome data of oncologic studies in the fields of colon, esophageal, and gastric cancer. I served as a reviewer for submitted manuscripts and discussed the impact, novelty, and decision for publication with the Board of Editors. In our weekly meetings, the associate editors discussed manuscripts that needed further review prior to acceptance, revision, or rejection. A few themes underpinned the discussion of these manuscripts:

- Is this science reproducible and is there scientific rigor for study design, validity, and analysis?

- How does this manuscript add to the current state of the literature?

- What is the trajectory of this research field?

- How will this manuscript lead to breakthroughs in this field?

- Are the advancements in this manuscript likely to lead to paradigm shifts in the field in its approach, design, or findings?

I also was fortunate to meet leaders in the field, including working daily in person with multiple members of the Board of Editors at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., as well as visiting professors, including Dr. Corley, Linda Rabeneck, MD, and T. Jake Liang, MD, who not only spoke on their scientific inquiries but also about their transitional path from gastroenterology fellows to pioneers in their respective fields. From these lessons, I have learned the scientific rigor of manuscript review for Gastroenterology and how to approach modern challenges in our field to directly improve patient care.

AGA’s commitment to early-career investigators

The Editorial Fellowship allowed me to expand a traditional third-year gastroenterology fellowship to dive deep into the intense path to get a manuscript published in Gastroenterology. Whereas 1 year prior, I had found dilating a complete esophageal stricture difficult, I now found myself learning to master clinical trial design, applying modern techniques of artificial intelligence, understanding organoid development, and navigating the impact of the microbiome. I was fortunate to be selected for Vanderbilt’s Master’s in Science in Clinical Investigation, which allowed me to apply my education not only to my own research but also to synergistically understand and deconstruct new submissions ranging from modern statistics with Bayesian modeling to analysis of large genetic data. All of this was built in the supportive framework of my mentoring committee.

As a fellow, I am inspired to see the multicenter, international collaboration to answer important questions in our field. Leveraging large databases and the expertise of multiple investigators, breakthroughs were made because of the collaborative nature of the science. This also was felt in the review process, where experts generously reviewed manuscripts to enhance the quality of the submission in order to advance knowledge in the field. Reading hundreds of these reviews this year has allowed me to refocus my current research studies and improve the way I write my current reviews. In the spirit of reproducible science and challenging the precision of study design, I was impressed by the time, effort, and dedication reviewers from our field spent to help improve the literature. Dr. Peek and Dr. Corley, our editors in chief, committed their time in discussing my innovations and critiques and displayed their level of interest in the opinions of early-career investigators and fostering the next generation of scientists and practitioners. In this lesson, I was invigorated by the depth of AGA opportunities for fellows and junior faculty in education, research, and involvement.

Self-reflection

Having the honor and privilege to review manuscripts upon submission also increased my critical view of my current practices. I now question the level of evidence for which current patient care practices are based, which allows me to better understand the research areas that need increased attention to improve the quality of our guidelines and evidence. For motivated fellows interested in a path of academic medicine, I would strongly advise applying for this prestigious fellowship. In no other training process could I have learned such a breadth of scientific skills and directly apply them to my patient care, my research, and my role as an educator. Furthermore, I was able to contribute to the reviewing and editing process, which allowed me to directly contribute to the field at an early stage of my career. In this final lesson, I exit this impactful Editorial Fellowship in self-reflection. I leave this fellowship humbled – by you – the reader who continues to learn to improve your patient care, the scientist as she works tirelessly to answer questions and contribute to the literature, the gastroenterology community for their willingness to teach and mentor fellows and early-career investigators and practitioners, and the patients who remind us that we all have a shared mission to advance scientific knowledge to improve patient care.

Dr. Naik is a gastroenterology fellow in the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

Reference

1. Shah ED. Skills acquired during my 1-year AGA Editorial Fellowship. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1563.

Estate planning: A must-do for all medical professionals

As medical professionals, you may have encountered patients with serious illnesses and asked yourself the following questions: What if I was in that situation? Where will my assets go when I die? What will happen to my loved ones, and will they be taken care of? Who would handle my affairs if I became ill? These important questions can only be addressed through effective estate planning.

Everyone needs an estate plan regardless of age, health, and financial or family situation. An effective estate plan provides for the orderly management and disposition of your assets upon your death. In addition, as medical professionals may appreciate, an effective estate plan appoints individuals to manage your financial affairs and make health care decisions for you in the event that you become physically or mentally incapacitated.

The most common estate planning tool is a will, which dictates how your assets pass at death. In addition, a will identifies the personal representative of your estate (that is, the person who will see that your assets pass in accordance with your wishes) and, in many states, identifies the guardian of any minor children. Although a court will make the ultimate determination of who is appointed as the guardian, courts typically give significant weight to the person named in a will.

If you die “intestate,” meaning that you died without a valid will, your assets will be distributed in accordance with your state’s intestacy statutes, and any interested person (as opposed to the individual of your choice) may be appointed as the personal representative of your estate. Therefore, to ensure that your property goes to the individuals of your choice and that your final affairs are handled by the person you trust, a will is essential.

In many states, a revocable living trust can be equally beneficial. Like a will, a revocable living trust will dictate how your property passes at death and appoints a trustee to see that the property is distributed in accordance with your wishes. Revocable living trusts can be great tools for incapacity planning and, unlike a will, are not required to be recorded, so the trust agreement can remain private. The assets that are held in a revocable living trust also avoid the often lengthy and expensive probate process, which generally includes the preparation and filing of a petition to open the estate, an inventory identifying the assets of the estate, and an accounting that details all assets received and distributed, followed by the payment of fees based upon the value of the probate estate.

In many situations, leaving assets to young, disabled, or troubled children would result in catastrophic consequences, such as disqualification for government benefits, dissipation of assets for inappropriate uses, or attachment by creditors. Further, for wealthy individuals, outright distributions to spouses could lead to unnecessary estate tax. Wills and revocable trusts can protect against these issues by requiring that, at death, the decedent’s assets are held in further trust for these individuals.

There are various types of trusts that can help ensure that your assets are used for the benefit of your loved one while avoiding any unintended consequences, some of which include the following:

- Special needs trusts, which allow the trustee to use the trust funds for the benefit of the disabled beneficiary without disqualifying the beneficiary from important government benefits.

- Spendthrift trusts, which can protect the trust assets from claims of creditors or property division in a divorce action.

- Marital trusts, which can be used to reduce taxes and ensure that property will be distributed pursuant to your wishes upon the death of your spouse.

- Dynasty trusts, which can be used to protect assets for many generations and, in doing so, reduce the amount of federal and state transfer taxes.

Whether you use a will or revocable living trust, it is critical to coordinate the beneficiary designations of assets such as retirement accounts and life insurance policies, as well as any other account that passes by beneficiary designation. These beneficiary designations trump the provisions of your will and revocable living trust. Likewise, property owned jointly with another person as joint tenants with the right of survivorship, or with a spouse as tenants by the entirety, will pass directly to the joint owner and not pursuant to the terms of your will or revocable trust.

An effective estate plan involves not just planning for death, but also for your incapacity. A durable power of attorney allows you to select an agent or agents to manage your property during your lifetime. The power of attorney can become effective immediately so that the agent can act on your behalf upon execution of the document or the power of attorney can become effective only if and when you become incapacitated.

A durable power of attorney for health care (or advance health care directive) permits you to appoint an agent to make health care decisions on your behalf in the event that you cannot make your own decisions. In addition, should you become permanently unconscious or in a terminal condition, it permits you to appoint an agent who can withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. With a living will, you can express in writing the circumstances under which you do or do not want artificial life-sustaining measures.

With respect to these powers of attorney, the persons that you appoint as your agents should be people that you trust. It is also important to have conversations with your designated agents to ensure that they understand their responsibilities and your wishes. Without these powers of attorney, in the event of your incapacitation, a court will appoint a guardian. The guardian may not be the person you would have appointed, and it will result in annual, and burdensome, court filings.

As busy medical professionals, it may be difficult to find time to develop an estate plan and you may believe that there is plenty of time to do it in the future. It is important to begin thinking about your estate-planning goals and to speak with an attorney to help develop and draft your estate-planning documents. If you already have estate-planning documents, it is important to review those documents periodically to ensure that your estate-planning objectives have remained the same and, if they have changed, to update your documents.

No one knows what the future will hold, so it is important to consult with a local attorney to establish or review your estate plan now. If you do, you will be comforted by the fact that you and your loved ones will be taken care of in accordance with your wishes if you are unable to do so in the future.

Mr. D’Emilio is a managing member and Mr. Riley is an associate at McCollom D’Emilio Smith Uebler, Wilmington, Del.

As medical professionals, you may have encountered patients with serious illnesses and asked yourself the following questions: What if I was in that situation? Where will my assets go when I die? What will happen to my loved ones, and will they be taken care of? Who would handle my affairs if I became ill? These important questions can only be addressed through effective estate planning.

Everyone needs an estate plan regardless of age, health, and financial or family situation. An effective estate plan provides for the orderly management and disposition of your assets upon your death. In addition, as medical professionals may appreciate, an effective estate plan appoints individuals to manage your financial affairs and make health care decisions for you in the event that you become physically or mentally incapacitated.

The most common estate planning tool is a will, which dictates how your assets pass at death. In addition, a will identifies the personal representative of your estate (that is, the person who will see that your assets pass in accordance with your wishes) and, in many states, identifies the guardian of any minor children. Although a court will make the ultimate determination of who is appointed as the guardian, courts typically give significant weight to the person named in a will.

If you die “intestate,” meaning that you died without a valid will, your assets will be distributed in accordance with your state’s intestacy statutes, and any interested person (as opposed to the individual of your choice) may be appointed as the personal representative of your estate. Therefore, to ensure that your property goes to the individuals of your choice and that your final affairs are handled by the person you trust, a will is essential.

In many states, a revocable living trust can be equally beneficial. Like a will, a revocable living trust will dictate how your property passes at death and appoints a trustee to see that the property is distributed in accordance with your wishes. Revocable living trusts can be great tools for incapacity planning and, unlike a will, are not required to be recorded, so the trust agreement can remain private. The assets that are held in a revocable living trust also avoid the often lengthy and expensive probate process, which generally includes the preparation and filing of a petition to open the estate, an inventory identifying the assets of the estate, and an accounting that details all assets received and distributed, followed by the payment of fees based upon the value of the probate estate.

In many situations, leaving assets to young, disabled, or troubled children would result in catastrophic consequences, such as disqualification for government benefits, dissipation of assets for inappropriate uses, or attachment by creditors. Further, for wealthy individuals, outright distributions to spouses could lead to unnecessary estate tax. Wills and revocable trusts can protect against these issues by requiring that, at death, the decedent’s assets are held in further trust for these individuals.

There are various types of trusts that can help ensure that your assets are used for the benefit of your loved one while avoiding any unintended consequences, some of which include the following:

- Special needs trusts, which allow the trustee to use the trust funds for the benefit of the disabled beneficiary without disqualifying the beneficiary from important government benefits.

- Spendthrift trusts, which can protect the trust assets from claims of creditors or property division in a divorce action.

- Marital trusts, which can be used to reduce taxes and ensure that property will be distributed pursuant to your wishes upon the death of your spouse.

- Dynasty trusts, which can be used to protect assets for many generations and, in doing so, reduce the amount of federal and state transfer taxes.

Whether you use a will or revocable living trust, it is critical to coordinate the beneficiary designations of assets such as retirement accounts and life insurance policies, as well as any other account that passes by beneficiary designation. These beneficiary designations trump the provisions of your will and revocable living trust. Likewise, property owned jointly with another person as joint tenants with the right of survivorship, or with a spouse as tenants by the entirety, will pass directly to the joint owner and not pursuant to the terms of your will or revocable trust.

An effective estate plan involves not just planning for death, but also for your incapacity. A durable power of attorney allows you to select an agent or agents to manage your property during your lifetime. The power of attorney can become effective immediately so that the agent can act on your behalf upon execution of the document or the power of attorney can become effective only if and when you become incapacitated.

A durable power of attorney for health care (or advance health care directive) permits you to appoint an agent to make health care decisions on your behalf in the event that you cannot make your own decisions. In addition, should you become permanently unconscious or in a terminal condition, it permits you to appoint an agent who can withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. With a living will, you can express in writing the circumstances under which you do or do not want artificial life-sustaining measures.

With respect to these powers of attorney, the persons that you appoint as your agents should be people that you trust. It is also important to have conversations with your designated agents to ensure that they understand their responsibilities and your wishes. Without these powers of attorney, in the event of your incapacitation, a court will appoint a guardian. The guardian may not be the person you would have appointed, and it will result in annual, and burdensome, court filings.

As busy medical professionals, it may be difficult to find time to develop an estate plan and you may believe that there is plenty of time to do it in the future. It is important to begin thinking about your estate-planning goals and to speak with an attorney to help develop and draft your estate-planning documents. If you already have estate-planning documents, it is important to review those documents periodically to ensure that your estate-planning objectives have remained the same and, if they have changed, to update your documents.

No one knows what the future will hold, so it is important to consult with a local attorney to establish or review your estate plan now. If you do, you will be comforted by the fact that you and your loved ones will be taken care of in accordance with your wishes if you are unable to do so in the future.

Mr. D’Emilio is a managing member and Mr. Riley is an associate at McCollom D’Emilio Smith Uebler, Wilmington, Del.

As medical professionals, you may have encountered patients with serious illnesses and asked yourself the following questions: What if I was in that situation? Where will my assets go when I die? What will happen to my loved ones, and will they be taken care of? Who would handle my affairs if I became ill? These important questions can only be addressed through effective estate planning.

Everyone needs an estate plan regardless of age, health, and financial or family situation. An effective estate plan provides for the orderly management and disposition of your assets upon your death. In addition, as medical professionals may appreciate, an effective estate plan appoints individuals to manage your financial affairs and make health care decisions for you in the event that you become physically or mentally incapacitated.

The most common estate planning tool is a will, which dictates how your assets pass at death. In addition, a will identifies the personal representative of your estate (that is, the person who will see that your assets pass in accordance with your wishes) and, in many states, identifies the guardian of any minor children. Although a court will make the ultimate determination of who is appointed as the guardian, courts typically give significant weight to the person named in a will.

If you die “intestate,” meaning that you died without a valid will, your assets will be distributed in accordance with your state’s intestacy statutes, and any interested person (as opposed to the individual of your choice) may be appointed as the personal representative of your estate. Therefore, to ensure that your property goes to the individuals of your choice and that your final affairs are handled by the person you trust, a will is essential.

In many states, a revocable living trust can be equally beneficial. Like a will, a revocable living trust will dictate how your property passes at death and appoints a trustee to see that the property is distributed in accordance with your wishes. Revocable living trusts can be great tools for incapacity planning and, unlike a will, are not required to be recorded, so the trust agreement can remain private. The assets that are held in a revocable living trust also avoid the often lengthy and expensive probate process, which generally includes the preparation and filing of a petition to open the estate, an inventory identifying the assets of the estate, and an accounting that details all assets received and distributed, followed by the payment of fees based upon the value of the probate estate.

In many situations, leaving assets to young, disabled, or troubled children would result in catastrophic consequences, such as disqualification for government benefits, dissipation of assets for inappropriate uses, or attachment by creditors. Further, for wealthy individuals, outright distributions to spouses could lead to unnecessary estate tax. Wills and revocable trusts can protect against these issues by requiring that, at death, the decedent’s assets are held in further trust for these individuals.

There are various types of trusts that can help ensure that your assets are used for the benefit of your loved one while avoiding any unintended consequences, some of which include the following:

- Special needs trusts, which allow the trustee to use the trust funds for the benefit of the disabled beneficiary without disqualifying the beneficiary from important government benefits.

- Spendthrift trusts, which can protect the trust assets from claims of creditors or property division in a divorce action.

- Marital trusts, which can be used to reduce taxes and ensure that property will be distributed pursuant to your wishes upon the death of your spouse.

- Dynasty trusts, which can be used to protect assets for many generations and, in doing so, reduce the amount of federal and state transfer taxes.

Whether you use a will or revocable living trust, it is critical to coordinate the beneficiary designations of assets such as retirement accounts and life insurance policies, as well as any other account that passes by beneficiary designation. These beneficiary designations trump the provisions of your will and revocable living trust. Likewise, property owned jointly with another person as joint tenants with the right of survivorship, or with a spouse as tenants by the entirety, will pass directly to the joint owner and not pursuant to the terms of your will or revocable trust.

An effective estate plan involves not just planning for death, but also for your incapacity. A durable power of attorney allows you to select an agent or agents to manage your property during your lifetime. The power of attorney can become effective immediately so that the agent can act on your behalf upon execution of the document or the power of attorney can become effective only if and when you become incapacitated.

A durable power of attorney for health care (or advance health care directive) permits you to appoint an agent to make health care decisions on your behalf in the event that you cannot make your own decisions. In addition, should you become permanently unconscious or in a terminal condition, it permits you to appoint an agent who can withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. With a living will, you can express in writing the circumstances under which you do or do not want artificial life-sustaining measures.

With respect to these powers of attorney, the persons that you appoint as your agents should be people that you trust. It is also important to have conversations with your designated agents to ensure that they understand their responsibilities and your wishes. Without these powers of attorney, in the event of your incapacitation, a court will appoint a guardian. The guardian may not be the person you would have appointed, and it will result in annual, and burdensome, court filings.

As busy medical professionals, it may be difficult to find time to develop an estate plan and you may believe that there is plenty of time to do it in the future. It is important to begin thinking about your estate-planning goals and to speak with an attorney to help develop and draft your estate-planning documents. If you already have estate-planning documents, it is important to review those documents periodically to ensure that your estate-planning objectives have remained the same and, if they have changed, to update your documents.

No one knows what the future will hold, so it is important to consult with a local attorney to establish or review your estate plan now. If you do, you will be comforted by the fact that you and your loved ones will be taken care of in accordance with your wishes if you are unable to do so in the future.

Mr. D’Emilio is a managing member and Mr. Riley is an associate at McCollom D’Emilio Smith Uebler, Wilmington, Del.

Building an effective community gastroenterology practice

During my medical training and fellowship, I often heard that my education was not preparing me for the real world. After 3 years of internal medicine training with limited exposure to the outpatient arena and 3-4 years of specialty gastroenterology, hepatology, and advanced procedure training, you’ve probably heard the same thing. Most gastroenterologists who enter private practice have felt this way early on, and our experiences can help you navigate some of the major factors that influence clinical practice to build a thriving career in gastroenterology.

Conduct research on referrals

Once you’ve decided to join a practice, do some research about local dynamics between large hospital systems and private practice. Community clinical practice is unique and varies by region, location, and how the practice is set up. GIs working in rural, low-access areas face different challenges than those working in urban areas near major health care systems. In rural, low-access areas, some physicians have long wait lists for office appointments and procedures.

In urban settings, there may be a larger population of patients but more competition from hospital systems and other practices. In this case, you’ll have to figure out where most of the referrals come from and why – is it the group’s overall reputation or are there physicians in the practice with a highly needed specialty?

Determine if your specialty training can be a differentiator in your market. If you are multilingual and there is a large patient population that speaks the language(s) in which you are fluent, this can be a great way to bring new patients into a practice. This is especially true if there aren’t many (or any) physicians in the practice who are multilingual.

Meet with local physicians in health care systems. Make a connection with hospitalists, referring physicians, ED physicians, advanced practitioners, and surgeons while covering inpatient service. Volunteer for teaching activities – including for nursing staff, who are a great referral source.

Figure out what opportunities exist to have direct interactions with patients, such as health fairs. If possible, it might be smart to invest in marketing directly to patients in your community as well. Leverage opportunities provided by awareness months – such as providing patients with information about cancer screening – to establish a referral basis.

Medical practice is complex and at times can be confusing until you’ve practiced in a given location for some time. Look internally to learn about the community. It’s always a good idea to learn from those who have been practicing in the community for a long time. Don’t hesitate to ask questions and make suggestions, even if they seem naive. Develop relationships with staff members and gain their trust. Establishing a clear understanding of your specialty with your colleagues and staff also can be a good way to find referrals.

Learn the internal process

Schedules during early months are usually filled with urgent patients. Make yourself available for overflow referrals to other established physicians within the practice and for hospital discharge follow-ups. Reading through the charts of these patients can help you understand the various styles of other doctors and can help you familiarize yourself with referring physicians.

This also will help to clarify the process of how a patient moves through the system – from the time patients call the office to when they check out. This includes navigating through procedures, results reporting, and the recall system. While it will be hard to master all aspects of a practice right away, processes within practices are well established, and it is important for you to have a good understanding of how they function.

Focus on patient care and satisfaction

Learning internal processes also can be useful in increasing patient satisfaction, an important quality outcome indicator. As you’re starting out, keep the following things in mind that can help put your patients at ease and increase satisfaction.

- Understand how to communicate what a patient should expect when being seen. Being at ease with the process helps garner trust and confidence.

- Call patients the next day to check on their symptoms.

- Relay results personally. Make connections with family member(s).

- Remember that cultural competency is important. Do everything you can to ensure you’re meeting the social, cultural, and linguistic needs of patients in your community.

- Above all – continue to provide personalized and thorough care. Word of mouth is the best form of referral and is time tested.

Continue to grow

As you begin to understand the dynamics of local practice, it’s important to establish where you fit into the practice and start differentiating your expertise. Here are some ideas and suggestions for how you can continue to expand your patient base.

- Differentiate and establish a subspecialty within your practice: Motility, inflammatory bowel disease, Clostridium difficile/fecal microbiota transplantation, liver diseases, Celiac disease, and medical weight-loss programs are just a few.

- Establish connections with local medical societies as well as hospital and state committees. This is a great way to connect with other physicians of various specialties. If you have a specialty unique to the area, it may help establish a clear referral line.

- Establish a consistent conversation with referring physicians – get to know them and keep direct lines of communication, such as having their cell phone numbers.

- Look for public speaking engagements that reach patients directly. These are organized mostly through patient-based organization and foundations.

- Increase your reach through the local media and through social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

At this point, you should have plenty of patients to keep you busy, which could lead to other challenges in managing your various responsibilities and obligations. A key factor at this stage to help reduce stress is to lean on the effective and efficient support system your practice should have in place. Educating medical assistants or nurses on the most common GI diseases and conditions can help reduce the time involved in communicating results. Practice management software and patient portals can help create efficiencies to handle the increasing number of patient visits.

Remember, creating a referral process and patient base as a new gastroenterologist doesn’t have to be daunting. If you follow these tips, you’ll be on your way to establishing yourself within the community. No doubt you will have the same success as many physicians in my group and in the groups of my colleagues in the Digestive Health Physicians Association. And once you’re established, it will be your turn to help the next generation of physicians who want to enter private practice and thrive – so that independent community GI care remains strong well into the future.

Dr. Alaparthi is the director of committee operations at the Gastroenterology Center of Connecticut and serves as chair of the communications committee for the Digestive Health Physicians Association.

During my medical training and fellowship, I often heard that my education was not preparing me for the real world. After 3 years of internal medicine training with limited exposure to the outpatient arena and 3-4 years of specialty gastroenterology, hepatology, and advanced procedure training, you’ve probably heard the same thing. Most gastroenterologists who enter private practice have felt this way early on, and our experiences can help you navigate some of the major factors that influence clinical practice to build a thriving career in gastroenterology.

Conduct research on referrals

Once you’ve decided to join a practice, do some research about local dynamics between large hospital systems and private practice. Community clinical practice is unique and varies by region, location, and how the practice is set up. GIs working in rural, low-access areas face different challenges than those working in urban areas near major health care systems. In rural, low-access areas, some physicians have long wait lists for office appointments and procedures.

In urban settings, there may be a larger population of patients but more competition from hospital systems and other practices. In this case, you’ll have to figure out where most of the referrals come from and why – is it the group’s overall reputation or are there physicians in the practice with a highly needed specialty?

Determine if your specialty training can be a differentiator in your market. If you are multilingual and there is a large patient population that speaks the language(s) in which you are fluent, this can be a great way to bring new patients into a practice. This is especially true if there aren’t many (or any) physicians in the practice who are multilingual.

Meet with local physicians in health care systems. Make a connection with hospitalists, referring physicians, ED physicians, advanced practitioners, and surgeons while covering inpatient service. Volunteer for teaching activities – including for nursing staff, who are a great referral source.

Figure out what opportunities exist to have direct interactions with patients, such as health fairs. If possible, it might be smart to invest in marketing directly to patients in your community as well. Leverage opportunities provided by awareness months – such as providing patients with information about cancer screening – to establish a referral basis.

Medical practice is complex and at times can be confusing until you’ve practiced in a given location for some time. Look internally to learn about the community. It’s always a good idea to learn from those who have been practicing in the community for a long time. Don’t hesitate to ask questions and make suggestions, even if they seem naive. Develop relationships with staff members and gain their trust. Establishing a clear understanding of your specialty with your colleagues and staff also can be a good way to find referrals.

Learn the internal process

Schedules during early months are usually filled with urgent patients. Make yourself available for overflow referrals to other established physicians within the practice and for hospital discharge follow-ups. Reading through the charts of these patients can help you understand the various styles of other doctors and can help you familiarize yourself with referring physicians.

This also will help to clarify the process of how a patient moves through the system – from the time patients call the office to when they check out. This includes navigating through procedures, results reporting, and the recall system. While it will be hard to master all aspects of a practice right away, processes within practices are well established, and it is important for you to have a good understanding of how they function.

Focus on patient care and satisfaction

Learning internal processes also can be useful in increasing patient satisfaction, an important quality outcome indicator. As you’re starting out, keep the following things in mind that can help put your patients at ease and increase satisfaction.

- Understand how to communicate what a patient should expect when being seen. Being at ease with the process helps garner trust and confidence.

- Call patients the next day to check on their symptoms.

- Relay results personally. Make connections with family member(s).

- Remember that cultural competency is important. Do everything you can to ensure you’re meeting the social, cultural, and linguistic needs of patients in your community.

- Above all – continue to provide personalized and thorough care. Word of mouth is the best form of referral and is time tested.

Continue to grow

As you begin to understand the dynamics of local practice, it’s important to establish where you fit into the practice and start differentiating your expertise. Here are some ideas and suggestions for how you can continue to expand your patient base.

- Differentiate and establish a subspecialty within your practice: Motility, inflammatory bowel disease, Clostridium difficile/fecal microbiota transplantation, liver diseases, Celiac disease, and medical weight-loss programs are just a few.

- Establish connections with local medical societies as well as hospital and state committees. This is a great way to connect with other physicians of various specialties. If you have a specialty unique to the area, it may help establish a clear referral line.

- Establish a consistent conversation with referring physicians – get to know them and keep direct lines of communication, such as having their cell phone numbers.

- Look for public speaking engagements that reach patients directly. These are organized mostly through patient-based organization and foundations.

- Increase your reach through the local media and through social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.