User login

Lessons learned as a gastroenterologist on social media

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

Navigating a pandemic: The importance of preparedness in independent GI practices

It was early March, and our second day of advocacy on Capitol Hill with the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DHPA) was cut short when congressional offices were shuttered because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sitting with several of my GI physician colleagues from across the country, we knew that our practices, our patients, and our communities would be impacted by the coronavirus. None of us could have known the extent.

We also didn’t know in that moment that our advocacy work through DHPA would be one of the most important factors in ensuring that our practices were prepared to weather the pandemic. Our membership, legal counsel, and legislative lobbyists helped us remain informed about new legislation and regulations and ensured that we had much-needed access to government resources.

Just a few months into what is now the COVID-19 pandemic, independent GI practice leaders have learned a lot about how to strengthen our practices to respond to future crises – and what early-career GIs should look for in the practices they are considering.

First and foremost, practice leadership is key. One thing most successful GI practices have in common is that they hire really smart executives and administrative teams who excel at taking care of the business side of things so that physicians like me can do what we do best: treat patients.

Stay informed about state and federal policies

As a member of DHPA, Capital Digestive Care was well positioned to keep up to date on the government response to the coronavirus and the support it provided to small businesses and to health care providers.

Over the past 5 years, DHPA physician leaders have established strong relationships with our elected federal leaders. During our Capitol Hill visits in early March, we discussed the coronavirus in addition to our policy priorities.

The relationships we’ve built with policymakers have helped us educate them about how private practices were being affected and make the case that it was crucial to include private practices in health care stimulus packages.

Without this federal financial support, many medical groups may have had to close their doors – leaving a large gap in care once the pandemic subsides.

In addition to the federal government’s financial support, our policy advocacy efforts kept us informed about federal health agencies’ decisions on telehealth coverage. We were able to educate our physicians and staff about state and federal adjustments to telehealth rules for the pandemic, on the guidelines for elective procedures, on employee furlough and leave rules, as well as other congressional and state actions that would impact our practice.

You can’t be an independent physician without being open to learning about the business of health care and understanding how health policies affect your ability to practice medicine and care for people in your community. Every early-career physician who is looking to join a practice should ask how its leadership remains informed about health policy at the state and federal levels.

Make plans, be flexible

Implementing telehealth was critical in responding to the coronavirus pandemic. We were able to get up and running quickly on telemedicine because we had already invested in telehealth and had conducted a pilot of the platform with a smaller group of providers well before the pandemic hit.

In March, we were able to expand the telehealth platform to accommodate virtual visits by all of our providers. We also had to figure out how to shift our employees to telework, develop remote desktop and VPN solutions, and make sure that our scheduling and revenue cycle team members were fully operational.

The overriding goal was the safety of patients, staff, and our providers while continuing to provide medical care. Our inflammatory bowel disease patients needing visits to receive medication infusions took over an entire office so that there could be appropriate spacing and limited contacts with staff and other patients.

Our administrators knew early on that we needed a back-up plan and worked with physicians and providers doing telehealth visits to provide the flexibility to switch to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid–approved platforms (including Facetime) for those instances in which patients were uncomfortable using our main platform or when it was strained by bandwidth issues – a common challenge with any platform. Virtual check-in and check-out procedures were developed utilizing our usual office staff from remote locations.

For patients who had indications for gastroenterology procedures, we established a prioritization system, based on state guidelines, for those that were needed urgently or routinely as our endoscopy centers began to reopen. Safety measures were put into place including screening questionnaires, preprocedure COVID rt-PCT testing, personal protective equipment, and workflow changes to achieve social distancing.

As an early-career GI physician who is considering private practice, you’ll likely have several conversations with administrative leaders when deciding what practice to join. Ask about how the practice responded to COVID-19, and what processes it has in place to prepare for future emergencies.

During the early weeks of the pandemic, the CDC Board of Managers met two to three times per week. Task forces to discuss office operations and planning for ambulatory surgery center opening were established with participation by nearly every provider and manager. Communication between all providers and managers was important to decrease the obvious anxiety everyone was experiencing.

Old financial models may no longer work

Most practices develop budgets based on historical data. We quickly figured out that budgets from historical forecasts no longer worked and that we needed to understand the impact to budgets almost in real time.

We immediately looked to conserve cash and reduce expenses, requesting that our large vendors extend payment terms or provide a period of forbearance. We looked at everything from our EMR costs to lab supplies and everything in between.

Changing how we modeled our budgets and reducing costs made some of our hard decisions less difficult. While we had to furlough staff, our models for reducing physician compensation and lowering our costs allowed us to create a model for the return to work that included the use of paid time off and paid health care for our furloughed employees.

Our operations team also set up systems to gather information that was needed to apply for and report on federal loans and grants. They also set up ways to track revenue per visit and appeals for denied telehealth and other services in an effort to create new models and budgets as COVID-19 progressed. The revenue cycle team focused on unpaid older accounts receivable.

Focused on the future

It’s an understatement to say that COVID-19 has forever changed the practice of medicine. The health care industry will need to transform.

For some time now, GI practices have discussed the consequence of disruptive innovation affecting utilization of endoscopic procedures. We were looking at technology that might eventually replace office personnel. No one was thinking about a pandemic that would cause nearly overnight closure of endoscopy suites and curtail the entire in-office administrative workforce. The coronavirus pandemic is likely to be the catalyst that brings many innovations into the mainstream.

We’ll most likely see a transition to the virtual medical office for those visits that don’t require a patient to see a physician in person. This will make online scheduling and registration, on-demand messaging, and remote patient monitoring and chronic care management necessities.

We may also see more rapid adoption of technologies that allow information from health trackers and wearables to be integrated into EMRs that easily follow the patient from physician to physician. Administrative support and patient assistance from remote locations will become the norm.

Inquiring about how practices plan for emergencies and how their leadership thinks about the future of gastroenterology is a great way to show that you’re thinking holistically about health care delivery and how medicine is practiced now and in the future.

So much has changed in the decades I’ve been practicing medicine and so much is yet to change. As early-career GI physicians who are familiar with new technologies, you are in a great position to lead the practices you join into the future of gastroenterology.

Dr. Weinstein is president and CEO of Capital Digestive Care and the immediate past president of the Digestive Health Physicians Association.

It was early March, and our second day of advocacy on Capitol Hill with the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DHPA) was cut short when congressional offices were shuttered because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sitting with several of my GI physician colleagues from across the country, we knew that our practices, our patients, and our communities would be impacted by the coronavirus. None of us could have known the extent.

We also didn’t know in that moment that our advocacy work through DHPA would be one of the most important factors in ensuring that our practices were prepared to weather the pandemic. Our membership, legal counsel, and legislative lobbyists helped us remain informed about new legislation and regulations and ensured that we had much-needed access to government resources.

Just a few months into what is now the COVID-19 pandemic, independent GI practice leaders have learned a lot about how to strengthen our practices to respond to future crises – and what early-career GIs should look for in the practices they are considering.

First and foremost, practice leadership is key. One thing most successful GI practices have in common is that they hire really smart executives and administrative teams who excel at taking care of the business side of things so that physicians like me can do what we do best: treat patients.

Stay informed about state and federal policies

As a member of DHPA, Capital Digestive Care was well positioned to keep up to date on the government response to the coronavirus and the support it provided to small businesses and to health care providers.

Over the past 5 years, DHPA physician leaders have established strong relationships with our elected federal leaders. During our Capitol Hill visits in early March, we discussed the coronavirus in addition to our policy priorities.

The relationships we’ve built with policymakers have helped us educate them about how private practices were being affected and make the case that it was crucial to include private practices in health care stimulus packages.

Without this federal financial support, many medical groups may have had to close their doors – leaving a large gap in care once the pandemic subsides.

In addition to the federal government’s financial support, our policy advocacy efforts kept us informed about federal health agencies’ decisions on telehealth coverage. We were able to educate our physicians and staff about state and federal adjustments to telehealth rules for the pandemic, on the guidelines for elective procedures, on employee furlough and leave rules, as well as other congressional and state actions that would impact our practice.

You can’t be an independent physician without being open to learning about the business of health care and understanding how health policies affect your ability to practice medicine and care for people in your community. Every early-career physician who is looking to join a practice should ask how its leadership remains informed about health policy at the state and federal levels.

Make plans, be flexible

Implementing telehealth was critical in responding to the coronavirus pandemic. We were able to get up and running quickly on telemedicine because we had already invested in telehealth and had conducted a pilot of the platform with a smaller group of providers well before the pandemic hit.

In March, we were able to expand the telehealth platform to accommodate virtual visits by all of our providers. We also had to figure out how to shift our employees to telework, develop remote desktop and VPN solutions, and make sure that our scheduling and revenue cycle team members were fully operational.

The overriding goal was the safety of patients, staff, and our providers while continuing to provide medical care. Our inflammatory bowel disease patients needing visits to receive medication infusions took over an entire office so that there could be appropriate spacing and limited contacts with staff and other patients.

Our administrators knew early on that we needed a back-up plan and worked with physicians and providers doing telehealth visits to provide the flexibility to switch to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid–approved platforms (including Facetime) for those instances in which patients were uncomfortable using our main platform or when it was strained by bandwidth issues – a common challenge with any platform. Virtual check-in and check-out procedures were developed utilizing our usual office staff from remote locations.

For patients who had indications for gastroenterology procedures, we established a prioritization system, based on state guidelines, for those that were needed urgently or routinely as our endoscopy centers began to reopen. Safety measures were put into place including screening questionnaires, preprocedure COVID rt-PCT testing, personal protective equipment, and workflow changes to achieve social distancing.

As an early-career GI physician who is considering private practice, you’ll likely have several conversations with administrative leaders when deciding what practice to join. Ask about how the practice responded to COVID-19, and what processes it has in place to prepare for future emergencies.

During the early weeks of the pandemic, the CDC Board of Managers met two to three times per week. Task forces to discuss office operations and planning for ambulatory surgery center opening were established with participation by nearly every provider and manager. Communication between all providers and managers was important to decrease the obvious anxiety everyone was experiencing.

Old financial models may no longer work

Most practices develop budgets based on historical data. We quickly figured out that budgets from historical forecasts no longer worked and that we needed to understand the impact to budgets almost in real time.

We immediately looked to conserve cash and reduce expenses, requesting that our large vendors extend payment terms or provide a period of forbearance. We looked at everything from our EMR costs to lab supplies and everything in between.

Changing how we modeled our budgets and reducing costs made some of our hard decisions less difficult. While we had to furlough staff, our models for reducing physician compensation and lowering our costs allowed us to create a model for the return to work that included the use of paid time off and paid health care for our furloughed employees.

Our operations team also set up systems to gather information that was needed to apply for and report on federal loans and grants. They also set up ways to track revenue per visit and appeals for denied telehealth and other services in an effort to create new models and budgets as COVID-19 progressed. The revenue cycle team focused on unpaid older accounts receivable.

Focused on the future

It’s an understatement to say that COVID-19 has forever changed the practice of medicine. The health care industry will need to transform.

For some time now, GI practices have discussed the consequence of disruptive innovation affecting utilization of endoscopic procedures. We were looking at technology that might eventually replace office personnel. No one was thinking about a pandemic that would cause nearly overnight closure of endoscopy suites and curtail the entire in-office administrative workforce. The coronavirus pandemic is likely to be the catalyst that brings many innovations into the mainstream.

We’ll most likely see a transition to the virtual medical office for those visits that don’t require a patient to see a physician in person. This will make online scheduling and registration, on-demand messaging, and remote patient monitoring and chronic care management necessities.

We may also see more rapid adoption of technologies that allow information from health trackers and wearables to be integrated into EMRs that easily follow the patient from physician to physician. Administrative support and patient assistance from remote locations will become the norm.

Inquiring about how practices plan for emergencies and how their leadership thinks about the future of gastroenterology is a great way to show that you’re thinking holistically about health care delivery and how medicine is practiced now and in the future.

So much has changed in the decades I’ve been practicing medicine and so much is yet to change. As early-career GI physicians who are familiar with new technologies, you are in a great position to lead the practices you join into the future of gastroenterology.

Dr. Weinstein is president and CEO of Capital Digestive Care and the immediate past president of the Digestive Health Physicians Association.

It was early March, and our second day of advocacy on Capitol Hill with the Digestive Health Physicians Association (DHPA) was cut short when congressional offices were shuttered because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sitting with several of my GI physician colleagues from across the country, we knew that our practices, our patients, and our communities would be impacted by the coronavirus. None of us could have known the extent.

We also didn’t know in that moment that our advocacy work through DHPA would be one of the most important factors in ensuring that our practices were prepared to weather the pandemic. Our membership, legal counsel, and legislative lobbyists helped us remain informed about new legislation and regulations and ensured that we had much-needed access to government resources.

Just a few months into what is now the COVID-19 pandemic, independent GI practice leaders have learned a lot about how to strengthen our practices to respond to future crises – and what early-career GIs should look for in the practices they are considering.

First and foremost, practice leadership is key. One thing most successful GI practices have in common is that they hire really smart executives and administrative teams who excel at taking care of the business side of things so that physicians like me can do what we do best: treat patients.

Stay informed about state and federal policies

As a member of DHPA, Capital Digestive Care was well positioned to keep up to date on the government response to the coronavirus and the support it provided to small businesses and to health care providers.

Over the past 5 years, DHPA physician leaders have established strong relationships with our elected federal leaders. During our Capitol Hill visits in early March, we discussed the coronavirus in addition to our policy priorities.

The relationships we’ve built with policymakers have helped us educate them about how private practices were being affected and make the case that it was crucial to include private practices in health care stimulus packages.

Without this federal financial support, many medical groups may have had to close their doors – leaving a large gap in care once the pandemic subsides.

In addition to the federal government’s financial support, our policy advocacy efforts kept us informed about federal health agencies’ decisions on telehealth coverage. We were able to educate our physicians and staff about state and federal adjustments to telehealth rules for the pandemic, on the guidelines for elective procedures, on employee furlough and leave rules, as well as other congressional and state actions that would impact our practice.

You can’t be an independent physician without being open to learning about the business of health care and understanding how health policies affect your ability to practice medicine and care for people in your community. Every early-career physician who is looking to join a practice should ask how its leadership remains informed about health policy at the state and federal levels.

Make plans, be flexible

Implementing telehealth was critical in responding to the coronavirus pandemic. We were able to get up and running quickly on telemedicine because we had already invested in telehealth and had conducted a pilot of the platform with a smaller group of providers well before the pandemic hit.

In March, we were able to expand the telehealth platform to accommodate virtual visits by all of our providers. We also had to figure out how to shift our employees to telework, develop remote desktop and VPN solutions, and make sure that our scheduling and revenue cycle team members were fully operational.

The overriding goal was the safety of patients, staff, and our providers while continuing to provide medical care. Our inflammatory bowel disease patients needing visits to receive medication infusions took over an entire office so that there could be appropriate spacing and limited contacts with staff and other patients.

Our administrators knew early on that we needed a back-up plan and worked with physicians and providers doing telehealth visits to provide the flexibility to switch to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid–approved platforms (including Facetime) for those instances in which patients were uncomfortable using our main platform or when it was strained by bandwidth issues – a common challenge with any platform. Virtual check-in and check-out procedures were developed utilizing our usual office staff from remote locations.

For patients who had indications for gastroenterology procedures, we established a prioritization system, based on state guidelines, for those that were needed urgently or routinely as our endoscopy centers began to reopen. Safety measures were put into place including screening questionnaires, preprocedure COVID rt-PCT testing, personal protective equipment, and workflow changes to achieve social distancing.

As an early-career GI physician who is considering private practice, you’ll likely have several conversations with administrative leaders when deciding what practice to join. Ask about how the practice responded to COVID-19, and what processes it has in place to prepare for future emergencies.

During the early weeks of the pandemic, the CDC Board of Managers met two to three times per week. Task forces to discuss office operations and planning for ambulatory surgery center opening were established with participation by nearly every provider and manager. Communication between all providers and managers was important to decrease the obvious anxiety everyone was experiencing.

Old financial models may no longer work

Most practices develop budgets based on historical data. We quickly figured out that budgets from historical forecasts no longer worked and that we needed to understand the impact to budgets almost in real time.

We immediately looked to conserve cash and reduce expenses, requesting that our large vendors extend payment terms or provide a period of forbearance. We looked at everything from our EMR costs to lab supplies and everything in between.

Changing how we modeled our budgets and reducing costs made some of our hard decisions less difficult. While we had to furlough staff, our models for reducing physician compensation and lowering our costs allowed us to create a model for the return to work that included the use of paid time off and paid health care for our furloughed employees.

Our operations team also set up systems to gather information that was needed to apply for and report on federal loans and grants. They also set up ways to track revenue per visit and appeals for denied telehealth and other services in an effort to create new models and budgets as COVID-19 progressed. The revenue cycle team focused on unpaid older accounts receivable.

Focused on the future

It’s an understatement to say that COVID-19 has forever changed the practice of medicine. The health care industry will need to transform.

For some time now, GI practices have discussed the consequence of disruptive innovation affecting utilization of endoscopic procedures. We were looking at technology that might eventually replace office personnel. No one was thinking about a pandemic that would cause nearly overnight closure of endoscopy suites and curtail the entire in-office administrative workforce. The coronavirus pandemic is likely to be the catalyst that brings many innovations into the mainstream.

We’ll most likely see a transition to the virtual medical office for those visits that don’t require a patient to see a physician in person. This will make online scheduling and registration, on-demand messaging, and remote patient monitoring and chronic care management necessities.

We may also see more rapid adoption of technologies that allow information from health trackers and wearables to be integrated into EMRs that easily follow the patient from physician to physician. Administrative support and patient assistance from remote locations will become the norm.

Inquiring about how practices plan for emergencies and how their leadership thinks about the future of gastroenterology is a great way to show that you’re thinking holistically about health care delivery and how medicine is practiced now and in the future.

So much has changed in the decades I’ve been practicing medicine and so much is yet to change. As early-career GI physicians who are familiar with new technologies, you are in a great position to lead the practices you join into the future of gastroenterology.

Dr. Weinstein is president and CEO of Capital Digestive Care and the immediate past president of the Digestive Health Physicians Association.

Coronavirus impact on medical education: Thoughts from two GI fellows’ perspectives

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

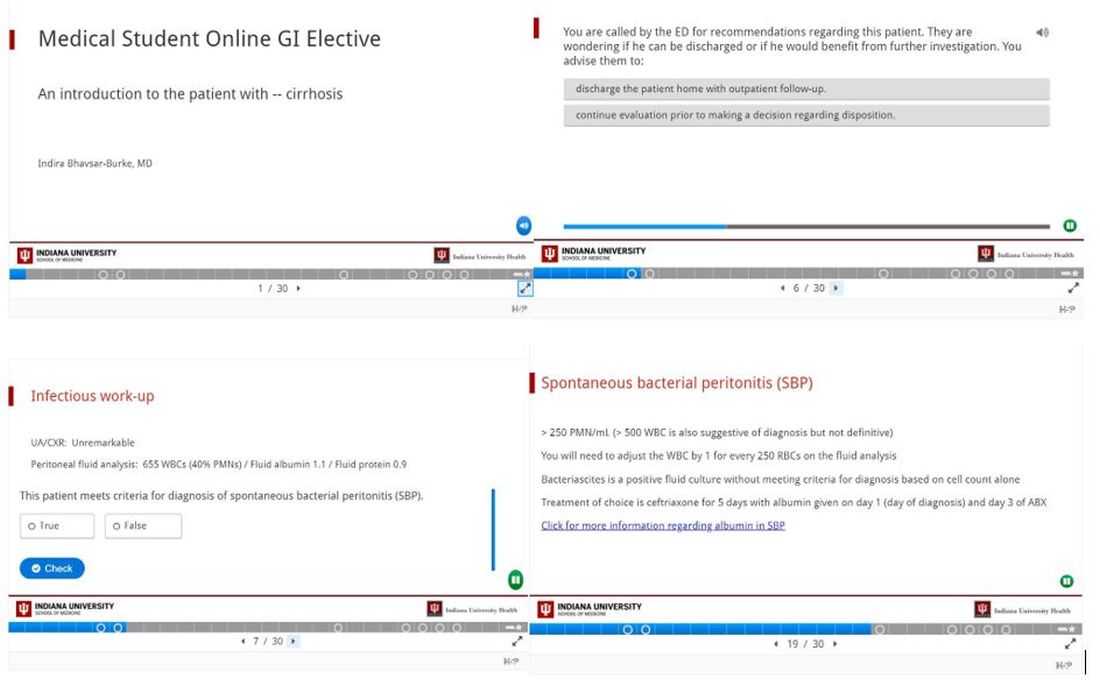

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

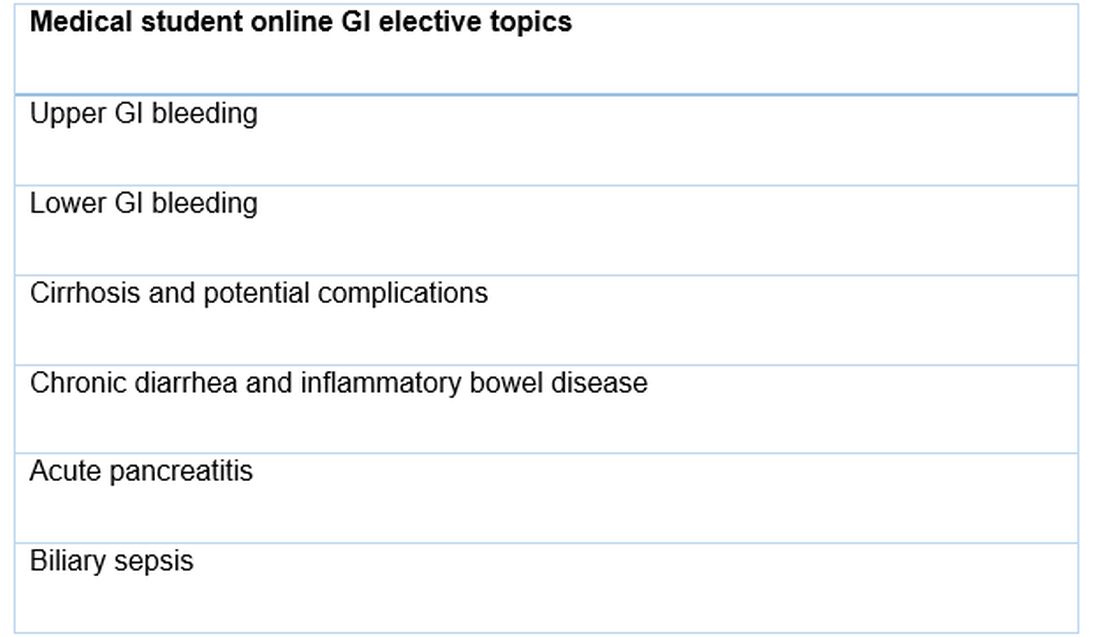

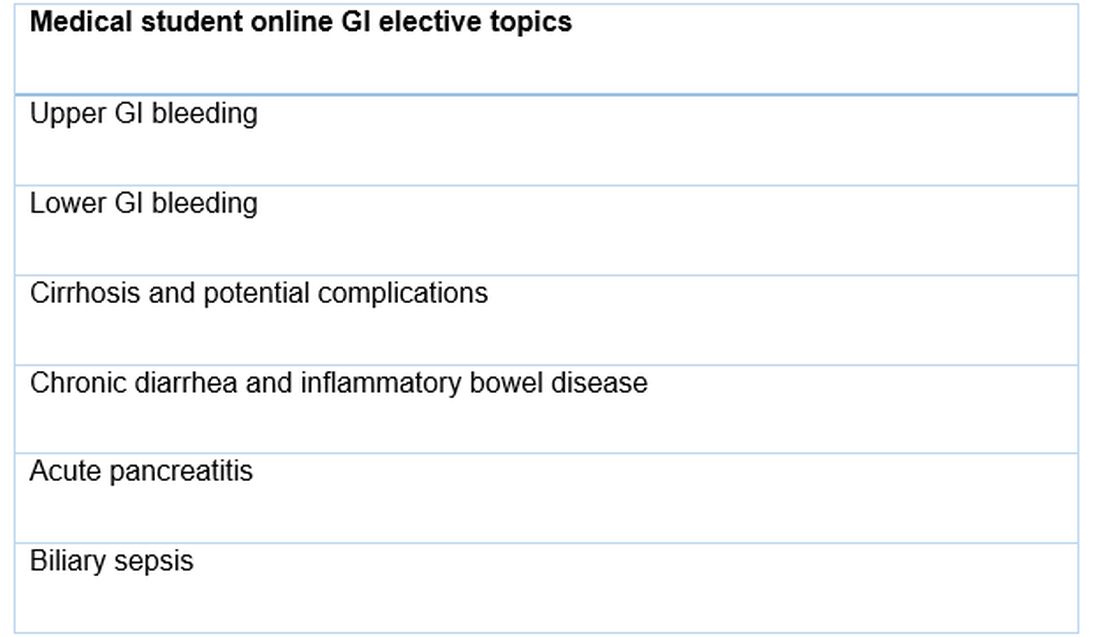

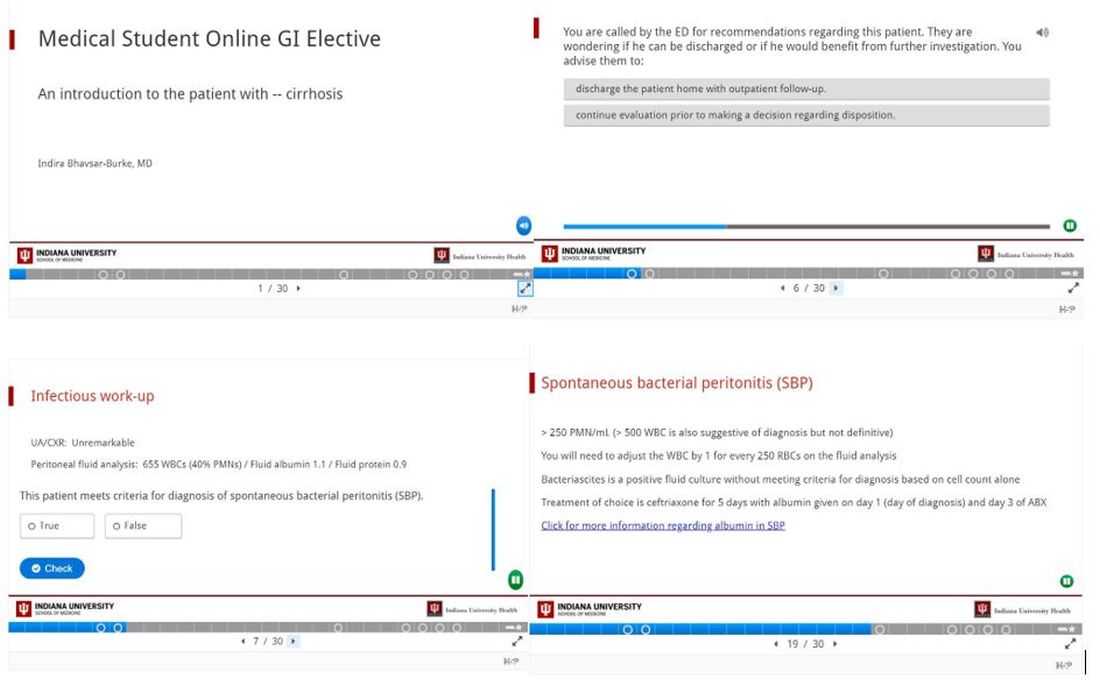

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Introduction

We are living in an unprecedented time. During March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) outbreak, our institution removed all medical students from rotations with direct patient contact to prioritize their safety and well-being, following recommendations made by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).1 Similarly, we as gastroenterology fellows experienced an upheaval in our usual schedules and routines. Some of us were redeployed to other areas of the hospital, such as inpatient wards and emergency departments, to meet the needs of our patients and our health system. These changes were difficult, not only because we were practicing in different roles, but also because unknown situations commonly incite fear and anxiety.

Among the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were the changes thrust upon medical students who suddenly found themselves without clinical exposure (both on core clerkships and electives) for the duration of the academic year.2 We too lost many of our educational and teaching opportunities as we adapted to our changing circumstances and new reality. Therefore, . We used the lessons we learned because of the changes in our own medical education to anticipate the best ways to provide learning opportunities for our students.

GI fellows’ experiences

The changes to our schedules and lack of in-person educational conferences seemingly happened overnight – the shock of being pulled from clinics, consults, and endoscopy left us feeling scared and lonely. We were quickly transitioned from knowing our roles and responsibilities as GI providers to taking over care for hospitalist patients as the “primary team,” working in the COVID emergency department (ED), and losing our clinic space. Redeployment to other clinical environments was anxiety-provoking. Self-doubt and fear were the most cited concerns as we asked ourselves: Do I remember enough general medicine to be an effective hospitalist? How do I place admission orders or perform a medication reconciliation on discharge? What can I expect in the COVID ED? Will I have to intubate someone? What about possible PPE shortages? Are my family members safe at home? Should I stay in a hotel? Do we have estimates on how long this will last?

Clinical schedules were reconfigured to consolidate the use of inpatient fellows and allow for reserves of fellows to be redeployed if needed. Schedules for the following 7 days were made just 48 hours prior to the start of each workweek. The anticipation and fear of the unknown were perhaps the hardest parts of the changes in our clinical learning environment. Little time was provided to make child care arrangements, coordinate with the schedules of significant others, or review topics and skills we might need in the next week that had gone unused for some time.

Our conference schedule was pared down considerably as fellows and attendings adjusted to their new responsibilities and a virtual platform for fellows’ education. While the transition to online lectures was seamless, the spirit of conference certainly changed. Impromptu questions and conversations that oftentimes arise organically during case conferences no longer occurred as virtual meetings do not offer the same space to foster these discussions as we awkwardly muted and unmuted ourselves. Participation in lectures seemed disjointed, which translated in some ways to less effective learning opportunities. Our involvement in endoscopy was also removed as only urgent cases were being performed and PPE conservation was of the utmost priority. This was especially concerning for third-year fellows on the cusp of graduation who would soon be independent practitioners without recent procedural practice. In general, the fellowship felt isolated and uncertain, which our program director addressed with weekly virtual COVID-19 “happy hour” updates.

GI fellows’ contribution

As our program encouraged us to come together during this time to support each other, we realized that while our clinical duties may look different during the COVID-19 crisis, our responsibility to learners was more important than ever. At many academic institutions, GI fellows are referred to as “the face of the division” owed in large part to our consistent presence on consult services and roles as teachers for medical students and residents who rotate with us. In an effort to assist the medical school’s charge to rapidly generate at-home curriculum for our students, we created an online curriculum for medical students to complete during the time they were previously scheduled to rotate with us on consults either as third- or fourth-year students.

We designed a series of interactive podcasts covering six topics that are commonly encountered issues on the GI consult service: upper GI bleeding, lower GI bleeding, biliary sepsis, acute pancreatitis, chronic diarrhea with a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, as well as cirrhosis and its associated complications.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant change in the daily activities of GI fellows including new responsibilities and a great need for adaptation. We hope that the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us – to think of others and make our talents available to those who need them, to look for ways to adapt to challenges, to live in the present but focus on the future, and to spread creativity when able – will continue long after the curve has flattened.

References

1. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/medical-school-life/online-learning-during-covid-19-tips-help-med-students. Apr 3, 2020.

2. Murphy B. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/covid-19-how-virus-impacting-medical-schools. Mar 20, 2020.

3. “H5P: Create, share and reuse interactive HTML5 content in your browser.” H5P website. https://h5p.org.

Dr. Bhavsar-Burke and Dr. Jansson-Knodell are GI fellows in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Choosing a career in health equity and health care policy

Dr. Anyane-Yeboa is a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Minority Health Policy at Harvard University and a recent graduate of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She previously completed her gastroenterology fellowship at the University of Chicago. She will be an academic gastroenterologist at Massachusetts General Hospital starting in the fall of 2020.

How did your career pathway lead you to a career in health equity and policy?