User login

Research Committee Chair Reflects

Before Andy Auerbach, MD, MPH, concludes a four-year term as chair of SHM’s Research Committee, I talked with him about his perspective on hospital medicine research. Dr. Auerbach is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

He received a career development award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) early in his career and is the principal investigator of an R01 research project grant from the NHLBI titled “Improving use of perioperative beta-blockers through a multidimensional QI program.”

He is also a co-author of “Outcomes of Patients Treated by Hospitalists, General Internists, and Family Physicians” in the December 2007 New England Journal of Medicine, which found statistically significant differences in length of stay and cost. He received his medical degree from Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H., and did his residency training in internal medicine at Yale New Haven Hospital in Connecticut. He completed an MPH in clinical epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston in 1998.

Q: So, is academia as glamorous as it sounds?

Dr. Auerbach: Way more glamorous—you should see my office. And yes, we are in a white tower.

Q: How did you get your start in research?

Dr. Auerbach: I actually started out my research fellowship wanting to be a cardiologist and go into the cath lab while developing the skills to participate in and teach research methods. I found I really enjoyed the work, particularly the creative and entrepreneurial aspects of developing a project or grant and seeing it through to completion.

Q: What are the research options for hospitalists practicing in nonteaching settings?

Dr. Auerbach: I think the most straightforward way to participate in research is to partner with a clinical research organization to help enroll patients in their trials. While you don’t get the opportunity to design the study, you do get to get a feel for consent/enrollment and internal review board [IRB] processes.

The next best way to get involved with research is to partner with a researcher—and this need not be a hospitalist—at your site or very near by. Many QI projects are close to being research-ready and may provide an opportunity to make that work count twice. But it will require you to learn about analytic methods.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t mention the value of other very useful academic products—rigorous reports of a QI intervention (think of both success and failure stories) and patient case reports. If well referenced and used as teaching documents, these can be very useful ways to advance knowledge.

Q: Are there any particular prerequisites in terms of training that you find especially helpful as you conduct your research?

Dr. Auerbach: It is hard to be a capital-R “Researcher” and compete for career development grants and NIH funding without some advanced [degrees] and a clinical research fellowship. I hesitate to call these prerequisites, but they are nearly so.

Q: What do you like best about your career as a hospitalist?

Dr. Auerbach: I really like acute care medicine, but didn’t want to subspecialize—otherwise I’d be wearing lead in a cath lab now. I also like the questions and processes in the hospital a bit more than the clinic setting.

Q: Who are your mentors and how did you find them?

Dr. Auerbach: I’ve had a remarkable set of mentors from fellowship [Mary Beth Hamel, Roger Davis, Russ Phillips] through my early career [Lee Goldman, Bob Wachter, Ralph Gonzales]. Now that I am early-mid career, I’m trying to pass their teaching on.

Q: Any advice for hospitalists interested in research but daunted by the prospect of starting their own studies?

Dr. Auerbach: If you want to do a scholarly/academic project to round out your personal/career satisfaction, I think the daunting nature of research can be overcome with the right questions and right support—and by defining what these are well before you actually dive into a dataset or implementation project. You also have to decide how much satisfaction you will get from the project in the end compared to the incremental nights/weekends you will spend to plan and execute your project—not to mention publish.

If you are thinking of research as a career, be aware of what makes you happy. If you like to write, enjoy the process of hypothesis generating/testing, and take rejection well you may be happy as a researcher. There are still plenty of nights/weekends to be spent, though.

Making a switch from full-time clinical or administrative work to research means making a very big commitment to going back to get the skills as part of a fellowship.

Q: Do researchers interested in quality improvement questions still have to run their work past the IRB?

Dr. Auerbach: Unfortunately this is now an area of uncertainty for people—unnecessarily so. Until recent events, IRBs have not required approval for QI projects that seek to enhance care according to an evidence-based standard, especially if that standard is endorsed by the institution. If you plan to publish your findings—particularly if you talk to or touch patients, or collect personal health information—I think it is nearly always wise to at least call your local IRB to ask for how you can or should conduct the study. This is best done before you start the project, obviously.

If you want to publish your results using deidentified data after the project is done, our IRB would say that is exempt from review [e.g., no need for approval]. But I think even this case would be worth a phone call to ensure your IRB feels similarly.

Whether or not you get IRB approval, be very aware of how and where you store data. TH

Before Andy Auerbach, MD, MPH, concludes a four-year term as chair of SHM’s Research Committee, I talked with him about his perspective on hospital medicine research. Dr. Auerbach is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

He received a career development award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) early in his career and is the principal investigator of an R01 research project grant from the NHLBI titled “Improving use of perioperative beta-blockers through a multidimensional QI program.”

He is also a co-author of “Outcomes of Patients Treated by Hospitalists, General Internists, and Family Physicians” in the December 2007 New England Journal of Medicine, which found statistically significant differences in length of stay and cost. He received his medical degree from Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H., and did his residency training in internal medicine at Yale New Haven Hospital in Connecticut. He completed an MPH in clinical epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston in 1998.

Q: So, is academia as glamorous as it sounds?

Dr. Auerbach: Way more glamorous—you should see my office. And yes, we are in a white tower.

Q: How did you get your start in research?

Dr. Auerbach: I actually started out my research fellowship wanting to be a cardiologist and go into the cath lab while developing the skills to participate in and teach research methods. I found I really enjoyed the work, particularly the creative and entrepreneurial aspects of developing a project or grant and seeing it through to completion.

Q: What are the research options for hospitalists practicing in nonteaching settings?

Dr. Auerbach: I think the most straightforward way to participate in research is to partner with a clinical research organization to help enroll patients in their trials. While you don’t get the opportunity to design the study, you do get to get a feel for consent/enrollment and internal review board [IRB] processes.

The next best way to get involved with research is to partner with a researcher—and this need not be a hospitalist—at your site or very near by. Many QI projects are close to being research-ready and may provide an opportunity to make that work count twice. But it will require you to learn about analytic methods.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t mention the value of other very useful academic products—rigorous reports of a QI intervention (think of both success and failure stories) and patient case reports. If well referenced and used as teaching documents, these can be very useful ways to advance knowledge.

Q: Are there any particular prerequisites in terms of training that you find especially helpful as you conduct your research?

Dr. Auerbach: It is hard to be a capital-R “Researcher” and compete for career development grants and NIH funding without some advanced [degrees] and a clinical research fellowship. I hesitate to call these prerequisites, but they are nearly so.

Q: What do you like best about your career as a hospitalist?

Dr. Auerbach: I really like acute care medicine, but didn’t want to subspecialize—otherwise I’d be wearing lead in a cath lab now. I also like the questions and processes in the hospital a bit more than the clinic setting.

Q: Who are your mentors and how did you find them?

Dr. Auerbach: I’ve had a remarkable set of mentors from fellowship [Mary Beth Hamel, Roger Davis, Russ Phillips] through my early career [Lee Goldman, Bob Wachter, Ralph Gonzales]. Now that I am early-mid career, I’m trying to pass their teaching on.

Q: Any advice for hospitalists interested in research but daunted by the prospect of starting their own studies?

Dr. Auerbach: If you want to do a scholarly/academic project to round out your personal/career satisfaction, I think the daunting nature of research can be overcome with the right questions and right support—and by defining what these are well before you actually dive into a dataset or implementation project. You also have to decide how much satisfaction you will get from the project in the end compared to the incremental nights/weekends you will spend to plan and execute your project—not to mention publish.

If you are thinking of research as a career, be aware of what makes you happy. If you like to write, enjoy the process of hypothesis generating/testing, and take rejection well you may be happy as a researcher. There are still plenty of nights/weekends to be spent, though.

Making a switch from full-time clinical or administrative work to research means making a very big commitment to going back to get the skills as part of a fellowship.

Q: Do researchers interested in quality improvement questions still have to run their work past the IRB?

Dr. Auerbach: Unfortunately this is now an area of uncertainty for people—unnecessarily so. Until recent events, IRBs have not required approval for QI projects that seek to enhance care according to an evidence-based standard, especially if that standard is endorsed by the institution. If you plan to publish your findings—particularly if you talk to or touch patients, or collect personal health information—I think it is nearly always wise to at least call your local IRB to ask for how you can or should conduct the study. This is best done before you start the project, obviously.

If you want to publish your results using deidentified data after the project is done, our IRB would say that is exempt from review [e.g., no need for approval]. But I think even this case would be worth a phone call to ensure your IRB feels similarly.

Whether or not you get IRB approval, be very aware of how and where you store data. TH

Before Andy Auerbach, MD, MPH, concludes a four-year term as chair of SHM’s Research Committee, I talked with him about his perspective on hospital medicine research. Dr. Auerbach is an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

He received a career development award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) early in his career and is the principal investigator of an R01 research project grant from the NHLBI titled “Improving use of perioperative beta-blockers through a multidimensional QI program.”

He is also a co-author of “Outcomes of Patients Treated by Hospitalists, General Internists, and Family Physicians” in the December 2007 New England Journal of Medicine, which found statistically significant differences in length of stay and cost. He received his medical degree from Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, N.H., and did his residency training in internal medicine at Yale New Haven Hospital in Connecticut. He completed an MPH in clinical epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston in 1998.

Q: So, is academia as glamorous as it sounds?

Dr. Auerbach: Way more glamorous—you should see my office. And yes, we are in a white tower.

Q: How did you get your start in research?

Dr. Auerbach: I actually started out my research fellowship wanting to be a cardiologist and go into the cath lab while developing the skills to participate in and teach research methods. I found I really enjoyed the work, particularly the creative and entrepreneurial aspects of developing a project or grant and seeing it through to completion.

Q: What are the research options for hospitalists practicing in nonteaching settings?

Dr. Auerbach: I think the most straightforward way to participate in research is to partner with a clinical research organization to help enroll patients in their trials. While you don’t get the opportunity to design the study, you do get to get a feel for consent/enrollment and internal review board [IRB] processes.

The next best way to get involved with research is to partner with a researcher—and this need not be a hospitalist—at your site or very near by. Many QI projects are close to being research-ready and may provide an opportunity to make that work count twice. But it will require you to learn about analytic methods.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t mention the value of other very useful academic products—rigorous reports of a QI intervention (think of both success and failure stories) and patient case reports. If well referenced and used as teaching documents, these can be very useful ways to advance knowledge.

Q: Are there any particular prerequisites in terms of training that you find especially helpful as you conduct your research?

Dr. Auerbach: It is hard to be a capital-R “Researcher” and compete for career development grants and NIH funding without some advanced [degrees] and a clinical research fellowship. I hesitate to call these prerequisites, but they are nearly so.

Q: What do you like best about your career as a hospitalist?

Dr. Auerbach: I really like acute care medicine, but didn’t want to subspecialize—otherwise I’d be wearing lead in a cath lab now. I also like the questions and processes in the hospital a bit more than the clinic setting.

Q: Who are your mentors and how did you find them?

Dr. Auerbach: I’ve had a remarkable set of mentors from fellowship [Mary Beth Hamel, Roger Davis, Russ Phillips] through my early career [Lee Goldman, Bob Wachter, Ralph Gonzales]. Now that I am early-mid career, I’m trying to pass their teaching on.

Q: Any advice for hospitalists interested in research but daunted by the prospect of starting their own studies?

Dr. Auerbach: If you want to do a scholarly/academic project to round out your personal/career satisfaction, I think the daunting nature of research can be overcome with the right questions and right support—and by defining what these are well before you actually dive into a dataset or implementation project. You also have to decide how much satisfaction you will get from the project in the end compared to the incremental nights/weekends you will spend to plan and execute your project—not to mention publish.

If you are thinking of research as a career, be aware of what makes you happy. If you like to write, enjoy the process of hypothesis generating/testing, and take rejection well you may be happy as a researcher. There are still plenty of nights/weekends to be spent, though.

Making a switch from full-time clinical or administrative work to research means making a very big commitment to going back to get the skills as part of a fellowship.

Q: Do researchers interested in quality improvement questions still have to run their work past the IRB?

Dr. Auerbach: Unfortunately this is now an area of uncertainty for people—unnecessarily so. Until recent events, IRBs have not required approval for QI projects that seek to enhance care according to an evidence-based standard, especially if that standard is endorsed by the institution. If you plan to publish your findings—particularly if you talk to or touch patients, or collect personal health information—I think it is nearly always wise to at least call your local IRB to ask for how you can or should conduct the study. This is best done before you start the project, obviously.

If you want to publish your results using deidentified data after the project is done, our IRB would say that is exempt from review [e.g., no need for approval]. But I think even this case would be worth a phone call to ensure your IRB feels similarly.

Whether or not you get IRB approval, be very aware of how and where you store data. TH

Satisfaction Is Job No. 1

The Career Satisfaction Task Force has focused on two key areas this year to build upon the work that resulted in last year’s white paper “A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction.”

The paper outlined a framework for hospital medicine program leaders and hospitalists to identify important components of matching individuals and programs for the best job fit.

This year, the task force is working to bring the white paper to life and moving it from a conceptual framework to demonstrating how to use it to solve real issues facing programs and individuals.

The first of these projects was a Webinar led by SHM Senior Vice President Joe Miller, Sylvia McKean, MD (course director of Hospital Medicine 2008), and Win Whitcomb, MD (a co-founder of SHM). Each of them has held leadership roles on this task force. About 80 people participated in the December event, and more than three-fourths of attendees rated it highly.

At last year’s Annual Meeting in Dallas, the white paper was presented in a task force workshop. In keeping with our aim to bring the framework to life, this year’s workshop will use real case studies to demonstrate how to use bring the concepts to solutions. The workshop will be facilitated by Chad Whelan, MD, assistant professor of medicine and director of the Hospitalists Scholars Training Program, University of Chicago. Discussing key concepts will be Doug Carlson, MD, associate professor, Pediatrics Division, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Tosha Wetterneck, MD, University of Wisconsin Hospital/Clinics, Madison. Drs. Carlson and Wetterneck made significant contributions to the white paper. In this highly interactive workshop, case studies that demonstrate challenges with workload/scheduling and autonomy will be discussed. Drs. Carlson and Wetterneck will lead the participants through discussions aimed at identifying the root causes of struggle and potential solutions for the program.

In the coming months, we hope to develop a series of articles to be published in The Hospitalist addressing the issues of greatest importance for career satisfaction.

The task force realizes there may be opportunities to add knowledge about career satisfaction and provide a valuable service to SHM member. We are in the early stages of developing a survey geared to further clarifying the most important factors in making satisfying career matches as well as providing detailed feedback about programs to their leaders. We are seeking funding to enable us to begin this exciting work.

The Career Satisfaction Task Force has focused on two key areas this year to build upon the work that resulted in last year’s white paper “A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction.”

The paper outlined a framework for hospital medicine program leaders and hospitalists to identify important components of matching individuals and programs for the best job fit.

This year, the task force is working to bring the white paper to life and moving it from a conceptual framework to demonstrating how to use it to solve real issues facing programs and individuals.

The first of these projects was a Webinar led by SHM Senior Vice President Joe Miller, Sylvia McKean, MD (course director of Hospital Medicine 2008), and Win Whitcomb, MD (a co-founder of SHM). Each of them has held leadership roles on this task force. About 80 people participated in the December event, and more than three-fourths of attendees rated it highly.

At last year’s Annual Meeting in Dallas, the white paper was presented in a task force workshop. In keeping with our aim to bring the framework to life, this year’s workshop will use real case studies to demonstrate how to use bring the concepts to solutions. The workshop will be facilitated by Chad Whelan, MD, assistant professor of medicine and director of the Hospitalists Scholars Training Program, University of Chicago. Discussing key concepts will be Doug Carlson, MD, associate professor, Pediatrics Division, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Tosha Wetterneck, MD, University of Wisconsin Hospital/Clinics, Madison. Drs. Carlson and Wetterneck made significant contributions to the white paper. In this highly interactive workshop, case studies that demonstrate challenges with workload/scheduling and autonomy will be discussed. Drs. Carlson and Wetterneck will lead the participants through discussions aimed at identifying the root causes of struggle and potential solutions for the program.

In the coming months, we hope to develop a series of articles to be published in The Hospitalist addressing the issues of greatest importance for career satisfaction.

The task force realizes there may be opportunities to add knowledge about career satisfaction and provide a valuable service to SHM member. We are in the early stages of developing a survey geared to further clarifying the most important factors in making satisfying career matches as well as providing detailed feedback about programs to their leaders. We are seeking funding to enable us to begin this exciting work.

The Career Satisfaction Task Force has focused on two key areas this year to build upon the work that resulted in last year’s white paper “A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction.”

The paper outlined a framework for hospital medicine program leaders and hospitalists to identify important components of matching individuals and programs for the best job fit.

This year, the task force is working to bring the white paper to life and moving it from a conceptual framework to demonstrating how to use it to solve real issues facing programs and individuals.

The first of these projects was a Webinar led by SHM Senior Vice President Joe Miller, Sylvia McKean, MD (course director of Hospital Medicine 2008), and Win Whitcomb, MD (a co-founder of SHM). Each of them has held leadership roles on this task force. About 80 people participated in the December event, and more than three-fourths of attendees rated it highly.

At last year’s Annual Meeting in Dallas, the white paper was presented in a task force workshop. In keeping with our aim to bring the framework to life, this year’s workshop will use real case studies to demonstrate how to use bring the concepts to solutions. The workshop will be facilitated by Chad Whelan, MD, assistant professor of medicine and director of the Hospitalists Scholars Training Program, University of Chicago. Discussing key concepts will be Doug Carlson, MD, associate professor, Pediatrics Division, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Tosha Wetterneck, MD, University of Wisconsin Hospital/Clinics, Madison. Drs. Carlson and Wetterneck made significant contributions to the white paper. In this highly interactive workshop, case studies that demonstrate challenges with workload/scheduling and autonomy will be discussed. Drs. Carlson and Wetterneck will lead the participants through discussions aimed at identifying the root causes of struggle and potential solutions for the program.

In the coming months, we hope to develop a series of articles to be published in The Hospitalist addressing the issues of greatest importance for career satisfaction.

The task force realizes there may be opportunities to add knowledge about career satisfaction and provide a valuable service to SHM member. We are in the early stages of developing a survey geared to further clarifying the most important factors in making satisfying career matches as well as providing detailed feedback about programs to their leaders. We are seeking funding to enable us to begin this exciting work.

What is the best method of treating acutely worsened chronic pain?

Case

A 69-year-old female with metastatic ovarian cancer and chronic pain syndrome presented to the hospital with seven days of progressively worsening abdominal pain. The pain had been similar to her chronic cancer pain but more severe. She has acute renal failure secondary to volume depletion from poor intake. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis reveal progression of her cancer with acute pathology. What is the best method of treating this patient’s pain?

Overview

Pain is pandemic. It is the most common reason patients seek healthcare.1 Almost one-third of Americans will experience severe chronic pain at some point in their lives. Every year, approximately 25 million Americans experience acute pain and 50 million experience chronic pain. Only one in four patients with pain receives appropriate therapy and control of their pain.

Pain is the most common symptom experienced by hospitalized adults.2 Acute or chronic pain can be particularly challenging to treat because these patients are frequently opioid dependent and have many psychosocial factors. No one method of pain control is superior to another. However, one method to gain rapid control of an acute pain crisis in a patient with chronic pain is to use patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).

Review of the Data

The first commercially available PCA pumps became available in 1976.3 They were created after studies in the 1960s demonstrated that small doses of opioids given intravenously provided more effective pain relief than conventional intramuscular injections.

The majority of studies on PCAs are in the postoperative patient, with cancer pain being next most commonly studied. PCAs utilize microprocessor-controlled infusion pumps that deliver a preprogrammed dose of opioid when the patient pushes the demand button. They allow programming of dose (demand dose), time between doses (lockout interval), background infusion rate (basal rate), and nurse-initiated dose (bolus dose).

The PCA paradigm is based on the opioid pharmacologic concept of minimum effective analgesic concentration (MEAC).4,5 The MEAC is the smallest serum opioid concentration at which pain is relieved. The dose-response curve to opioids is sigmoidal such that minimal analgesia is achieved until the MEAC is reached, after which minute increases in opioid concentrations produce analgesia, until further increases produce no significant increased analgesic effect.

PCAs allow individualized dosing and titration to achieve the MEAC, with small incremental doses administered whenever the serum concentration falls below the MEAC. A major goal of PCA technology is to regulate drug delivery to rapidly achieve and maintain the MEAC.

Advantages of PCAs

- More individual dosing and titration of pain medications to account for inter-individual and intra-individual variability in the response to opioids;

- Negative feedback control system, an added safety measure to avoid respiratory depression. As patients become too sedated from opioids, they are no longer able to push the button to receive further opioids;

- Higher patient satisfaction with pain control, a major determinant being personal control over the delivery of pain relief;6-8 and

- Greater analgesic efficacy vs. conventional analgesia.

Disadvantages of PCAs

Select patient populations: Not all patients are able to understand and retain the required instructions necessary to safely or effectively use self-administered opioids (e.g., cognitively impaired patients).

Potential for opioid dosing errors: These are related to equipment factors, medical personnel prescribing or programming errors.

Increased cost: PCAs have been shown to be more expensive in comparison with intramuscular (IM) injections, the prior standard of care.9-10

PCA Prescribing

The parameters programmed into the PCA machine include the basal rate, demand (or incremental) dose, lockout interval, nurse-initiated bolus dose, and choice of opioid.

Basal rate: The continuous infusion of opioid set at an hourly rate. Most studies that compare PCA use with and without basal rates (in postoperative patients) do not show improved pain relief or sleep with basal rates.11 Basal rates have been associated with increased risk of sedation and respiratory depression.12

The routine use of basal rates is not recommended initially, unless a patient is opioid-tolerant (i.e., on chronic opioid therapy). For patients on chronic opioids, their 24-hour total opioid requirement is converted by equianalgesic dosing to the basal rate. Steady state is not achieved for eight to 12 hours of continuous infusion; therefore, it is not recommended to change the basal rate more frequently than every eight hours.13

Demand dose: The dose patients provide themselves by pushing the button. Studies on opioid-naïve patients using morphine PCAs have shown that 1 mg IV morphine was the optimal starting dose, based on good pain relief without respiratory depression. Lower doses, such as 0.5 mg IV morphine, are generally used in the elderly as opioid requirements are known to decrease with patient age.14

For patients with a basal rate, the demand dose is often set at 50% to 100% of the basal rate. The demand dose is the parameter that should be titrated up for acute pain control. World Health Organization guidelines recommend increasing the dose by 25% to 50% for mild to moderate pain, and 50% to 100% for moderate to severe pain.15

Lockout interval: Minimal allowable time between demand doses. This time is based on the time to peak effect of IV opioids and can vary from five to 15 minutes. The effects of varying lockout intervals—seven to 11 minutes for morphine and five to eight minutes for fentanyl—had no effect on pain levels or side effects.16 Ten minutes is a standard lockout interval.

Bolus dose: The nurse-initiated dose that may be given initially to achieve pain control and later to counteract incidental pain (e.g., that caused by physical therapy, dressing changes, or radiology tests). A recommended dose is equivalent to the basal rate or twice the demand dose.

Choice of opioid: Morphine is the standard opioid because of its familiarity, cost, and years of study. Although inter-individual variability exists, there are no major differences in side effects among the different opioids. Renal and hepatic insufficiency can increase the effects of opioids. Morphine is especially troublesome in renal failure because it has an active metabolite—morphine-6-glucuronide—that can accumulate and increase the risk of sedation and respiratory depression.

Other Concerns

PCA complications: The most well-studied adverse effects of PCAs are nausea and respiratory depression. There is no difference between PCAs and conventional analgesia in rates of nausea or respiratory depression.17

Nausea is the most common side effect in postoperative patients on PCAs. Patients rapidly develop tolerance to nausea over a period of days. However, many clinicians are concerned about respiratory depression and the risk of death. The overall incidence of respiratory depression with PCAs is less than 1% (range from 0.1 to 0.8%), similar to conventional analgesia. However, the incidence is significantly higher when basal rates are used, rising to 1.1 to 3.9%. Other factors predisposing a patient to increased risk of respiratory depression are older age, obstructive sleep apnea, hypovolemia, renal failure, and the concurrent use of other sedating medications.18

Medication errors are also common. The overall incidence of medication mishaps with PCAs is 1.2%.19 More than 50% of these occur because of operator-related errors (e.g., improper loading, programming errors, and documentation errors). Equipment malfunction is the next most common error.

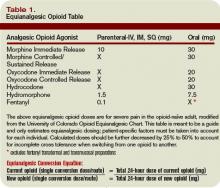

Opioid equianalgesic dosing conversions: The equianalgesic dose ratio is the ratio of the dose of two opioids required to produce the same analgesic effect. (See Table 1, right.) For example, IV morphine is three times as potent as oral morphine, with an equianalgesic dose ratio of 1:3. Equianalgesic dose tables vary somewhat in their values, which have been largely determined by single-dose administration studies.20 The generalizability of these tables to chronic opioid administration is not well studied.

Incomplete cross tolerance: When switching from one opioid to another, lower doses can be used to control pain.21, 22 Tolerance to one opioid does not completely transfer to the new opioid. Starting at half to two-thirds of the new opioid dose is generally recommended to avoid opioid-specific tolerance and inter-individual variability.23,24

Back to the Case

Opioids are the mainstay of pharmacological management of moderate-to-severe cancer pain. Evaluation of the patient reveals that her acute increase in pain is likely due to progression of her cancer. She had been taking morphine (sustained-release, 90 mg oral) twice daily for her pain and had been using approximately five doses per day of immediate-release oral morphine 20 mg for breakthrough pain. This is equivalent to a total 24-hour opioid requirement of 280 mg oral morphine.

She should be started on a PCA for rapid pain control and titration. Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is a better PCA choice than morphine because she has acute renal failure. The equianalgesic dose ratio of oral morphine to IV hydromorphone is approximately 30:1.5. The total 24-hour opioid dose of 280 mg oral morphine is equivalent to 14 mg IV hydromorphone ([280mg morphine per day ÷ 30] x 1.5 = 14).

After adjusting for 60% incomplete cross tolerance, the total 24-hour opioid dose is reduced to 8.4 mg IV hydromorphone (14 mg x 0.6 = 8.4 mg). This is approximately equivalent to 0.4 mg IV hydromorphone/hour (8.4 mg ÷ 24 hours), which is her initial basal rate. The demand dose should be set at 0.2 mg (50% the basal rate) with a lockout interval of 10 minutes.

Over a period of several days, the patient’s pain was controlled and her opioid requirements stabilized. She was on a basal rate of 1.4 mg/hour and a demand dose of 1 mg with a 10-minute lockout. Her total 24-hour opioid requirement was 44 mg of IV hydromorphone. As her renal function improved but did not completely normalize, oxycodone was chosen over morphine when converting her back to oral pain medications (less active renal metabolites). The equianalgesic dose ratio of oral oxycodone to IV hydromorphone is approximately 20:1.5. Her total 24-hour opioid dose of 44 mg IV hydromorphone is equivalent to 587 mg oral oxycodone (44 ÷ 1.5) x 20. After adjusting for 60% incomplete cross tolerance, the total 24-hour opioid dose is reduced to 352 mg oral oxycodone or 180 mg of sustained-release oxycodone twice daily (352 mg ÷ 2 ≈ 180 mg). For breakthrough pain she should receive 40 mg of immediate-release oxycodone every hour as needed (10% to 15% of the 24-hour opioid requirement). TH

Dr. Youngwerth is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine, University of Colorado at Denver, assistant director, Palliative Care Consult Service, associate director, Colorado Palliative Medicine Fellowship Program, and medical director, Hospice of Saint John.

References

- American Pain Society. Pain: Current understanding of assessment, management, and treatments. National Pharmaceutical Council 2006;1-79.

- Morrison RS, Meier DE, Fischberg D, et al. Improving the management of pain in hospitalized adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1033-1039.

- Grass JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S44-S61.

- Etches RC. Patient-controlled analgesia. Surg Clinics N Amer. 1999;79:297-312.

- Nolan MF and Wilson M-C B. Patient-controlled analgesia: A method for the controlled self-administration of opioid pain medications. Phys Ther. 1995;75:374-379.

- Ballantyne JC, Carr DB, Chalmers TC, Dear KBG, Angelillo IF, Mosteller F. Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia: Meta-analyses of initial randomized control trials. J Clin Anesth. 1993;5:182-193.

- Hudcova J, McNicol E, Quah C, Lau J, Carr DB. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus conventional opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;4:1-10.

- Sidebotham D, Dijkhuizen MRJ, Schug SA. The safety and utilization of patient-controlled analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:202-209.

- Macintyre PE. Safety and efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:36-46.

- Manon C, Rittenhouse BE, Perreault S, et al. Efficacy and costs of patient-controlled analgesia versus regularly administered intramuscular opioid therapy. Amer Soc Anesth Inc. 1998;89:1377-1388.

- Krenn H, Oczenski W, Jellinek H, Krumpl-Ströher M, Schweitzer E, Fitzgerald RD. Nalbuphine by PCA-pump for analgesia following hysterectomy: Bolus application versus continuous infusion with bolus application. Eur J Pain. 2001;5:219-226.

- Lehmann KA. Recent developments in patient-controlled analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:S72-S89.

- American Pain Society. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. 5th ed. 2003:1-73.

- Macintyre PC, Jarvis DA. Age is the best predictor of postoperative morphine requirements. Pain. 1995;64:357-364.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Adult cancer pain. Version 2.2005:1-30.

- Ginsberg B, Gil KM, Muir M, Sullivan F, Williams DA, Glass PSA. The influence of lockout intervals and drug selection on patient-controlled analgesia following gynecological surgery. Pain. 1995;62:95-100.

- Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, Tramer MR. Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:795-804.

- Etches RC. Respiratory depression associated with patient-controlled analgesia: a review of eight cases. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:125-132.

- Oswalt KE, Shrewsbury P, Stanton-Hicks M. The incidence of medication mishaps in 3,299 PCA patients. Pain. 1990;S5;S152.

- Pereira J, Lawlor P, Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E. Equianalgesic dose rations for opioids: A critical review and proposals for long-term dosing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:672-687.

- Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943-1953.

- Mercandante S. Opioid rotation for cancer pain. Cancer. 1999;86:1856-1866.

- Mehta V, Langford RM. Acute pain management for opioid dependent patients. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:269-276.

- Pasternak GW. Incomplete cross tolerance and multiple mu opioid peptide receptors. Trends Pharm Sciences. 2001;22:67-70.

Case

A 69-year-old female with metastatic ovarian cancer and chronic pain syndrome presented to the hospital with seven days of progressively worsening abdominal pain. The pain had been similar to her chronic cancer pain but more severe. She has acute renal failure secondary to volume depletion from poor intake. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis reveal progression of her cancer with acute pathology. What is the best method of treating this patient’s pain?

Overview

Pain is pandemic. It is the most common reason patients seek healthcare.1 Almost one-third of Americans will experience severe chronic pain at some point in their lives. Every year, approximately 25 million Americans experience acute pain and 50 million experience chronic pain. Only one in four patients with pain receives appropriate therapy and control of their pain.

Pain is the most common symptom experienced by hospitalized adults.2 Acute or chronic pain can be particularly challenging to treat because these patients are frequently opioid dependent and have many psychosocial factors. No one method of pain control is superior to another. However, one method to gain rapid control of an acute pain crisis in a patient with chronic pain is to use patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).

Review of the Data

The first commercially available PCA pumps became available in 1976.3 They were created after studies in the 1960s demonstrated that small doses of opioids given intravenously provided more effective pain relief than conventional intramuscular injections.

The majority of studies on PCAs are in the postoperative patient, with cancer pain being next most commonly studied. PCAs utilize microprocessor-controlled infusion pumps that deliver a preprogrammed dose of opioid when the patient pushes the demand button. They allow programming of dose (demand dose), time between doses (lockout interval), background infusion rate (basal rate), and nurse-initiated dose (bolus dose).

The PCA paradigm is based on the opioid pharmacologic concept of minimum effective analgesic concentration (MEAC).4,5 The MEAC is the smallest serum opioid concentration at which pain is relieved. The dose-response curve to opioids is sigmoidal such that minimal analgesia is achieved until the MEAC is reached, after which minute increases in opioid concentrations produce analgesia, until further increases produce no significant increased analgesic effect.

PCAs allow individualized dosing and titration to achieve the MEAC, with small incremental doses administered whenever the serum concentration falls below the MEAC. A major goal of PCA technology is to regulate drug delivery to rapidly achieve and maintain the MEAC.

Advantages of PCAs

- More individual dosing and titration of pain medications to account for inter-individual and intra-individual variability in the response to opioids;

- Negative feedback control system, an added safety measure to avoid respiratory depression. As patients become too sedated from opioids, they are no longer able to push the button to receive further opioids;

- Higher patient satisfaction with pain control, a major determinant being personal control over the delivery of pain relief;6-8 and

- Greater analgesic efficacy vs. conventional analgesia.

Disadvantages of PCAs

Select patient populations: Not all patients are able to understand and retain the required instructions necessary to safely or effectively use self-administered opioids (e.g., cognitively impaired patients).

Potential for opioid dosing errors: These are related to equipment factors, medical personnel prescribing or programming errors.

Increased cost: PCAs have been shown to be more expensive in comparison with intramuscular (IM) injections, the prior standard of care.9-10

PCA Prescribing

The parameters programmed into the PCA machine include the basal rate, demand (or incremental) dose, lockout interval, nurse-initiated bolus dose, and choice of opioid.

Basal rate: The continuous infusion of opioid set at an hourly rate. Most studies that compare PCA use with and without basal rates (in postoperative patients) do not show improved pain relief or sleep with basal rates.11 Basal rates have been associated with increased risk of sedation and respiratory depression.12

The routine use of basal rates is not recommended initially, unless a patient is opioid-tolerant (i.e., on chronic opioid therapy). For patients on chronic opioids, their 24-hour total opioid requirement is converted by equianalgesic dosing to the basal rate. Steady state is not achieved for eight to 12 hours of continuous infusion; therefore, it is not recommended to change the basal rate more frequently than every eight hours.13

Demand dose: The dose patients provide themselves by pushing the button. Studies on opioid-naïve patients using morphine PCAs have shown that 1 mg IV morphine was the optimal starting dose, based on good pain relief without respiratory depression. Lower doses, such as 0.5 mg IV morphine, are generally used in the elderly as opioid requirements are known to decrease with patient age.14

For patients with a basal rate, the demand dose is often set at 50% to 100% of the basal rate. The demand dose is the parameter that should be titrated up for acute pain control. World Health Organization guidelines recommend increasing the dose by 25% to 50% for mild to moderate pain, and 50% to 100% for moderate to severe pain.15

Lockout interval: Minimal allowable time between demand doses. This time is based on the time to peak effect of IV opioids and can vary from five to 15 minutes. The effects of varying lockout intervals—seven to 11 minutes for morphine and five to eight minutes for fentanyl—had no effect on pain levels or side effects.16 Ten minutes is a standard lockout interval.

Bolus dose: The nurse-initiated dose that may be given initially to achieve pain control and later to counteract incidental pain (e.g., that caused by physical therapy, dressing changes, or radiology tests). A recommended dose is equivalent to the basal rate or twice the demand dose.

Choice of opioid: Morphine is the standard opioid because of its familiarity, cost, and years of study. Although inter-individual variability exists, there are no major differences in side effects among the different opioids. Renal and hepatic insufficiency can increase the effects of opioids. Morphine is especially troublesome in renal failure because it has an active metabolite—morphine-6-glucuronide—that can accumulate and increase the risk of sedation and respiratory depression.

Other Concerns

PCA complications: The most well-studied adverse effects of PCAs are nausea and respiratory depression. There is no difference between PCAs and conventional analgesia in rates of nausea or respiratory depression.17

Nausea is the most common side effect in postoperative patients on PCAs. Patients rapidly develop tolerance to nausea over a period of days. However, many clinicians are concerned about respiratory depression and the risk of death. The overall incidence of respiratory depression with PCAs is less than 1% (range from 0.1 to 0.8%), similar to conventional analgesia. However, the incidence is significantly higher when basal rates are used, rising to 1.1 to 3.9%. Other factors predisposing a patient to increased risk of respiratory depression are older age, obstructive sleep apnea, hypovolemia, renal failure, and the concurrent use of other sedating medications.18

Medication errors are also common. The overall incidence of medication mishaps with PCAs is 1.2%.19 More than 50% of these occur because of operator-related errors (e.g., improper loading, programming errors, and documentation errors). Equipment malfunction is the next most common error.

Opioid equianalgesic dosing conversions: The equianalgesic dose ratio is the ratio of the dose of two opioids required to produce the same analgesic effect. (See Table 1, right.) For example, IV morphine is three times as potent as oral morphine, with an equianalgesic dose ratio of 1:3. Equianalgesic dose tables vary somewhat in their values, which have been largely determined by single-dose administration studies.20 The generalizability of these tables to chronic opioid administration is not well studied.

Incomplete cross tolerance: When switching from one opioid to another, lower doses can be used to control pain.21, 22 Tolerance to one opioid does not completely transfer to the new opioid. Starting at half to two-thirds of the new opioid dose is generally recommended to avoid opioid-specific tolerance and inter-individual variability.23,24

Back to the Case

Opioids are the mainstay of pharmacological management of moderate-to-severe cancer pain. Evaluation of the patient reveals that her acute increase in pain is likely due to progression of her cancer. She had been taking morphine (sustained-release, 90 mg oral) twice daily for her pain and had been using approximately five doses per day of immediate-release oral morphine 20 mg for breakthrough pain. This is equivalent to a total 24-hour opioid requirement of 280 mg oral morphine.

She should be started on a PCA for rapid pain control and titration. Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is a better PCA choice than morphine because she has acute renal failure. The equianalgesic dose ratio of oral morphine to IV hydromorphone is approximately 30:1.5. The total 24-hour opioid dose of 280 mg oral morphine is equivalent to 14 mg IV hydromorphone ([280mg morphine per day ÷ 30] x 1.5 = 14).

After adjusting for 60% incomplete cross tolerance, the total 24-hour opioid dose is reduced to 8.4 mg IV hydromorphone (14 mg x 0.6 = 8.4 mg). This is approximately equivalent to 0.4 mg IV hydromorphone/hour (8.4 mg ÷ 24 hours), which is her initial basal rate. The demand dose should be set at 0.2 mg (50% the basal rate) with a lockout interval of 10 minutes.

Over a period of several days, the patient’s pain was controlled and her opioid requirements stabilized. She was on a basal rate of 1.4 mg/hour and a demand dose of 1 mg with a 10-minute lockout. Her total 24-hour opioid requirement was 44 mg of IV hydromorphone. As her renal function improved but did not completely normalize, oxycodone was chosen over morphine when converting her back to oral pain medications (less active renal metabolites). The equianalgesic dose ratio of oral oxycodone to IV hydromorphone is approximately 20:1.5. Her total 24-hour opioid dose of 44 mg IV hydromorphone is equivalent to 587 mg oral oxycodone (44 ÷ 1.5) x 20. After adjusting for 60% incomplete cross tolerance, the total 24-hour opioid dose is reduced to 352 mg oral oxycodone or 180 mg of sustained-release oxycodone twice daily (352 mg ÷ 2 ≈ 180 mg). For breakthrough pain she should receive 40 mg of immediate-release oxycodone every hour as needed (10% to 15% of the 24-hour opioid requirement). TH

Dr. Youngwerth is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine, University of Colorado at Denver, assistant director, Palliative Care Consult Service, associate director, Colorado Palliative Medicine Fellowship Program, and medical director, Hospice of Saint John.

References

- American Pain Society. Pain: Current understanding of assessment, management, and treatments. National Pharmaceutical Council 2006;1-79.

- Morrison RS, Meier DE, Fischberg D, et al. Improving the management of pain in hospitalized adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1033-1039.

- Grass JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S44-S61.

- Etches RC. Patient-controlled analgesia. Surg Clinics N Amer. 1999;79:297-312.

- Nolan MF and Wilson M-C B. Patient-controlled analgesia: A method for the controlled self-administration of opioid pain medications. Phys Ther. 1995;75:374-379.

- Ballantyne JC, Carr DB, Chalmers TC, Dear KBG, Angelillo IF, Mosteller F. Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia: Meta-analyses of initial randomized control trials. J Clin Anesth. 1993;5:182-193.

- Hudcova J, McNicol E, Quah C, Lau J, Carr DB. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus conventional opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;4:1-10.

- Sidebotham D, Dijkhuizen MRJ, Schug SA. The safety and utilization of patient-controlled analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:202-209.

- Macintyre PE. Safety and efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:36-46.

- Manon C, Rittenhouse BE, Perreault S, et al. Efficacy and costs of patient-controlled analgesia versus regularly administered intramuscular opioid therapy. Amer Soc Anesth Inc. 1998;89:1377-1388.

- Krenn H, Oczenski W, Jellinek H, Krumpl-Ströher M, Schweitzer E, Fitzgerald RD. Nalbuphine by PCA-pump for analgesia following hysterectomy: Bolus application versus continuous infusion with bolus application. Eur J Pain. 2001;5:219-226.

- Lehmann KA. Recent developments in patient-controlled analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:S72-S89.

- American Pain Society. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. 5th ed. 2003:1-73.

- Macintyre PC, Jarvis DA. Age is the best predictor of postoperative morphine requirements. Pain. 1995;64:357-364.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Adult cancer pain. Version 2.2005:1-30.

- Ginsberg B, Gil KM, Muir M, Sullivan F, Williams DA, Glass PSA. The influence of lockout intervals and drug selection on patient-controlled analgesia following gynecological surgery. Pain. 1995;62:95-100.

- Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, Tramer MR. Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:795-804.

- Etches RC. Respiratory depression associated with patient-controlled analgesia: a review of eight cases. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:125-132.

- Oswalt KE, Shrewsbury P, Stanton-Hicks M. The incidence of medication mishaps in 3,299 PCA patients. Pain. 1990;S5;S152.

- Pereira J, Lawlor P, Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E. Equianalgesic dose rations for opioids: A critical review and proposals for long-term dosing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:672-687.

- Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943-1953.

- Mercandante S. Opioid rotation for cancer pain. Cancer. 1999;86:1856-1866.

- Mehta V, Langford RM. Acute pain management for opioid dependent patients. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:269-276.

- Pasternak GW. Incomplete cross tolerance and multiple mu opioid peptide receptors. Trends Pharm Sciences. 2001;22:67-70.

Case

A 69-year-old female with metastatic ovarian cancer and chronic pain syndrome presented to the hospital with seven days of progressively worsening abdominal pain. The pain had been similar to her chronic cancer pain but more severe. She has acute renal failure secondary to volume depletion from poor intake. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis reveal progression of her cancer with acute pathology. What is the best method of treating this patient’s pain?

Overview

Pain is pandemic. It is the most common reason patients seek healthcare.1 Almost one-third of Americans will experience severe chronic pain at some point in their lives. Every year, approximately 25 million Americans experience acute pain and 50 million experience chronic pain. Only one in four patients with pain receives appropriate therapy and control of their pain.

Pain is the most common symptom experienced by hospitalized adults.2 Acute or chronic pain can be particularly challenging to treat because these patients are frequently opioid dependent and have many psychosocial factors. No one method of pain control is superior to another. However, one method to gain rapid control of an acute pain crisis in a patient with chronic pain is to use patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).

Review of the Data

The first commercially available PCA pumps became available in 1976.3 They were created after studies in the 1960s demonstrated that small doses of opioids given intravenously provided more effective pain relief than conventional intramuscular injections.

The majority of studies on PCAs are in the postoperative patient, with cancer pain being next most commonly studied. PCAs utilize microprocessor-controlled infusion pumps that deliver a preprogrammed dose of opioid when the patient pushes the demand button. They allow programming of dose (demand dose), time between doses (lockout interval), background infusion rate (basal rate), and nurse-initiated dose (bolus dose).

The PCA paradigm is based on the opioid pharmacologic concept of minimum effective analgesic concentration (MEAC).4,5 The MEAC is the smallest serum opioid concentration at which pain is relieved. The dose-response curve to opioids is sigmoidal such that minimal analgesia is achieved until the MEAC is reached, after which minute increases in opioid concentrations produce analgesia, until further increases produce no significant increased analgesic effect.

PCAs allow individualized dosing and titration to achieve the MEAC, with small incremental doses administered whenever the serum concentration falls below the MEAC. A major goal of PCA technology is to regulate drug delivery to rapidly achieve and maintain the MEAC.

Advantages of PCAs

- More individual dosing and titration of pain medications to account for inter-individual and intra-individual variability in the response to opioids;

- Negative feedback control system, an added safety measure to avoid respiratory depression. As patients become too sedated from opioids, they are no longer able to push the button to receive further opioids;

- Higher patient satisfaction with pain control, a major determinant being personal control over the delivery of pain relief;6-8 and

- Greater analgesic efficacy vs. conventional analgesia.

Disadvantages of PCAs

Select patient populations: Not all patients are able to understand and retain the required instructions necessary to safely or effectively use self-administered opioids (e.g., cognitively impaired patients).

Potential for opioid dosing errors: These are related to equipment factors, medical personnel prescribing or programming errors.

Increased cost: PCAs have been shown to be more expensive in comparison with intramuscular (IM) injections, the prior standard of care.9-10

PCA Prescribing

The parameters programmed into the PCA machine include the basal rate, demand (or incremental) dose, lockout interval, nurse-initiated bolus dose, and choice of opioid.

Basal rate: The continuous infusion of opioid set at an hourly rate. Most studies that compare PCA use with and without basal rates (in postoperative patients) do not show improved pain relief or sleep with basal rates.11 Basal rates have been associated with increased risk of sedation and respiratory depression.12

The routine use of basal rates is not recommended initially, unless a patient is opioid-tolerant (i.e., on chronic opioid therapy). For patients on chronic opioids, their 24-hour total opioid requirement is converted by equianalgesic dosing to the basal rate. Steady state is not achieved for eight to 12 hours of continuous infusion; therefore, it is not recommended to change the basal rate more frequently than every eight hours.13

Demand dose: The dose patients provide themselves by pushing the button. Studies on opioid-naïve patients using morphine PCAs have shown that 1 mg IV morphine was the optimal starting dose, based on good pain relief without respiratory depression. Lower doses, such as 0.5 mg IV morphine, are generally used in the elderly as opioid requirements are known to decrease with patient age.14

For patients with a basal rate, the demand dose is often set at 50% to 100% of the basal rate. The demand dose is the parameter that should be titrated up for acute pain control. World Health Organization guidelines recommend increasing the dose by 25% to 50% for mild to moderate pain, and 50% to 100% for moderate to severe pain.15

Lockout interval: Minimal allowable time between demand doses. This time is based on the time to peak effect of IV opioids and can vary from five to 15 minutes. The effects of varying lockout intervals—seven to 11 minutes for morphine and five to eight minutes for fentanyl—had no effect on pain levels or side effects.16 Ten minutes is a standard lockout interval.

Bolus dose: The nurse-initiated dose that may be given initially to achieve pain control and later to counteract incidental pain (e.g., that caused by physical therapy, dressing changes, or radiology tests). A recommended dose is equivalent to the basal rate or twice the demand dose.

Choice of opioid: Morphine is the standard opioid because of its familiarity, cost, and years of study. Although inter-individual variability exists, there are no major differences in side effects among the different opioids. Renal and hepatic insufficiency can increase the effects of opioids. Morphine is especially troublesome in renal failure because it has an active metabolite—morphine-6-glucuronide—that can accumulate and increase the risk of sedation and respiratory depression.

Other Concerns

PCA complications: The most well-studied adverse effects of PCAs are nausea and respiratory depression. There is no difference between PCAs and conventional analgesia in rates of nausea or respiratory depression.17

Nausea is the most common side effect in postoperative patients on PCAs. Patients rapidly develop tolerance to nausea over a period of days. However, many clinicians are concerned about respiratory depression and the risk of death. The overall incidence of respiratory depression with PCAs is less than 1% (range from 0.1 to 0.8%), similar to conventional analgesia. However, the incidence is significantly higher when basal rates are used, rising to 1.1 to 3.9%. Other factors predisposing a patient to increased risk of respiratory depression are older age, obstructive sleep apnea, hypovolemia, renal failure, and the concurrent use of other sedating medications.18

Medication errors are also common. The overall incidence of medication mishaps with PCAs is 1.2%.19 More than 50% of these occur because of operator-related errors (e.g., improper loading, programming errors, and documentation errors). Equipment malfunction is the next most common error.

Opioid equianalgesic dosing conversions: The equianalgesic dose ratio is the ratio of the dose of two opioids required to produce the same analgesic effect. (See Table 1, right.) For example, IV morphine is three times as potent as oral morphine, with an equianalgesic dose ratio of 1:3. Equianalgesic dose tables vary somewhat in their values, which have been largely determined by single-dose administration studies.20 The generalizability of these tables to chronic opioid administration is not well studied.

Incomplete cross tolerance: When switching from one opioid to another, lower doses can be used to control pain.21, 22 Tolerance to one opioid does not completely transfer to the new opioid. Starting at half to two-thirds of the new opioid dose is generally recommended to avoid opioid-specific tolerance and inter-individual variability.23,24

Back to the Case

Opioids are the mainstay of pharmacological management of moderate-to-severe cancer pain. Evaluation of the patient reveals that her acute increase in pain is likely due to progression of her cancer. She had been taking morphine (sustained-release, 90 mg oral) twice daily for her pain and had been using approximately five doses per day of immediate-release oral morphine 20 mg for breakthrough pain. This is equivalent to a total 24-hour opioid requirement of 280 mg oral morphine.

She should be started on a PCA for rapid pain control and titration. Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is a better PCA choice than morphine because she has acute renal failure. The equianalgesic dose ratio of oral morphine to IV hydromorphone is approximately 30:1.5. The total 24-hour opioid dose of 280 mg oral morphine is equivalent to 14 mg IV hydromorphone ([280mg morphine per day ÷ 30] x 1.5 = 14).

After adjusting for 60% incomplete cross tolerance, the total 24-hour opioid dose is reduced to 8.4 mg IV hydromorphone (14 mg x 0.6 = 8.4 mg). This is approximately equivalent to 0.4 mg IV hydromorphone/hour (8.4 mg ÷ 24 hours), which is her initial basal rate. The demand dose should be set at 0.2 mg (50% the basal rate) with a lockout interval of 10 minutes.

Over a period of several days, the patient’s pain was controlled and her opioid requirements stabilized. She was on a basal rate of 1.4 mg/hour and a demand dose of 1 mg with a 10-minute lockout. Her total 24-hour opioid requirement was 44 mg of IV hydromorphone. As her renal function improved but did not completely normalize, oxycodone was chosen over morphine when converting her back to oral pain medications (less active renal metabolites). The equianalgesic dose ratio of oral oxycodone to IV hydromorphone is approximately 20:1.5. Her total 24-hour opioid dose of 44 mg IV hydromorphone is equivalent to 587 mg oral oxycodone (44 ÷ 1.5) x 20. After adjusting for 60% incomplete cross tolerance, the total 24-hour opioid dose is reduced to 352 mg oral oxycodone or 180 mg of sustained-release oxycodone twice daily (352 mg ÷ 2 ≈ 180 mg). For breakthrough pain she should receive 40 mg of immediate-release oxycodone every hour as needed (10% to 15% of the 24-hour opioid requirement). TH

Dr. Youngwerth is a hospitalist and instructor of medicine, University of Colorado at Denver, assistant director, Palliative Care Consult Service, associate director, Colorado Palliative Medicine Fellowship Program, and medical director, Hospice of Saint John.

References

- American Pain Society. Pain: Current understanding of assessment, management, and treatments. National Pharmaceutical Council 2006;1-79.

- Morrison RS, Meier DE, Fischberg D, et al. Improving the management of pain in hospitalized adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1033-1039.

- Grass JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S44-S61.

- Etches RC. Patient-controlled analgesia. Surg Clinics N Amer. 1999;79:297-312.

- Nolan MF and Wilson M-C B. Patient-controlled analgesia: A method for the controlled self-administration of opioid pain medications. Phys Ther. 1995;75:374-379.

- Ballantyne JC, Carr DB, Chalmers TC, Dear KBG, Angelillo IF, Mosteller F. Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia: Meta-analyses of initial randomized control trials. J Clin Anesth. 1993;5:182-193.

- Hudcova J, McNicol E, Quah C, Lau J, Carr DB. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus conventional opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;4:1-10.

- Sidebotham D, Dijkhuizen MRJ, Schug SA. The safety and utilization of patient-controlled analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:202-209.

- Macintyre PE. Safety and efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:36-46.

- Manon C, Rittenhouse BE, Perreault S, et al. Efficacy and costs of patient-controlled analgesia versus regularly administered intramuscular opioid therapy. Amer Soc Anesth Inc. 1998;89:1377-1388.

- Krenn H, Oczenski W, Jellinek H, Krumpl-Ströher M, Schweitzer E, Fitzgerald RD. Nalbuphine by PCA-pump for analgesia following hysterectomy: Bolus application versus continuous infusion with bolus application. Eur J Pain. 2001;5:219-226.

- Lehmann KA. Recent developments in patient-controlled analgesia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:S72-S89.

- American Pain Society. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. 5th ed. 2003:1-73.

- Macintyre PC, Jarvis DA. Age is the best predictor of postoperative morphine requirements. Pain. 1995;64:357-364.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Adult cancer pain. Version 2.2005:1-30.

- Ginsberg B, Gil KM, Muir M, Sullivan F, Williams DA, Glass PSA. The influence of lockout intervals and drug selection on patient-controlled analgesia following gynecological surgery. Pain. 1995;62:95-100.

- Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, Tramer MR. Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:795-804.

- Etches RC. Respiratory depression associated with patient-controlled analgesia: a review of eight cases. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:125-132.

- Oswalt KE, Shrewsbury P, Stanton-Hicks M. The incidence of medication mishaps in 3,299 PCA patients. Pain. 1990;S5;S152.

- Pereira J, Lawlor P, Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E. Equianalgesic dose rations for opioids: A critical review and proposals for long-term dosing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:672-687.

- Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943-1953.

- Mercandante S. Opioid rotation for cancer pain. Cancer. 1999;86:1856-1866.

- Mehta V, Langford RM. Acute pain management for opioid dependent patients. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:269-276.

- Pasternak GW. Incomplete cross tolerance and multiple mu opioid peptide receptors. Trends Pharm Sciences. 2001;22:67-70.

Malpractice Chronicle

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Oversedated, Unresponsive After Aneurysm Surgery

A 73-year-old man went to a hospital emergency department (ED) with complaints of chest pain, bloating, and blood in his stools. CT revealed an aortic aneurysm, and surgery was performed three days later. In the recovery room, the patient became confused and agitated. He managed to leave the building before several nurses were able to restrain him and return him to his room.

It was determined that the man was experiencing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, making him uncooperative and potentially violent. He was started on a detoxification protocol, which included lorazepam and haloperidol.

Over the next several days, the patient appeared oversedated and unresponsive, and his lorazepam dosage was reduced. When he developed a rattle in his chest and began to have trouble breathing, no action was taken. He went into respiratory arrest and was intubated; during this procedure, he sustained a punctured lung. Although the man was resuscitated, he was left with anoxic brain injury. He remained in a deep coma until his ventilator was turned off.

Plaintiffs for the decedent claimed that he was oversedated. He developed a mucous plug that he was unable to clear because of physical restraints and a decreased level of consciousness.

According to a published account, a settlement of $107,500 was reached.

Discontinued Monitoring for Abdominal Cyst

The plaintiff child, an infant girl, was delivered in September by an Ob-Gyn from a women's health practice. Her mother had undergone serial fetal ultrasonography to monitor an abdominal cyst that was detected in the unborn child early in the woman's pregnancy.

During the eight weeks following hospital discharge, the child was seen numerous times by physicians at a pediatrics/adolescent medicine group for digestive issues, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and pale-colored stools. In late October, the mother asked one of the pediatricians whether the infant's problems could be related to the cyst; she questioned whether the prenatal ultrasounds had been faxed to the pediatrician's office.

When no follow-up testing was ordered, the parents took the infant to another doctor, who had her admitted. She was diagnosed with a choledochal cyst (a congenital bile duct anomaly) and liver failure. During surgery, associated biliary atresia was also discovered.

In February, the infant underwent a liver transplant. She suffered one episode of liver rejection and will require a lifelong regimen of antirejection medications.

According to the plaintiff, an Ob-Gyn had assured the mother that an order for postpartum ultrasonography would be placed in the chart to ensure follow-up on the infant's cyst, but the test was never ordered. The plaintiffs also claimed that the Ob-Gyn never informed the pediatrics/adolescent medicine group about the cyst and that no information about the cyst was placed in the newborn's charts by hospital nurses. The plaintiff claimed that proper monitoring would have led to early intervention at a time when the infant's liver was salvageable.

The defendants contended that they had communicated properly and that the child would still have needed a liver transplant, even if testing had been conducted earlier.

During the trial, a confidential settlement was reached with the hospital and the pediatrics group. According to a published report, a $16.5 million verdict was returned against the women's health practice.

Abscess Develops Following a Fall

One day at work, a 54-year-old man fell off his chair and landed on his right hip. He did not seek immediate medical attention but was in considerable pain by the time he arrived home. During the night, his pain worsened, and his wife called an ambulance.

When the patient arrived at the ED, he was barely able to walk and reported a 9 on the 10-point pain scale. His skin moistness, color, and temperature were all normal. An IV was started, and the man was given morphine. When his pain persisted, he was given ketorolac tromethamine, meperidine, and hydroxyzine pamoate.

The ED physician made a diagnosis of acute lumbosacral strain and released the man with prescriptions and instructions for hydrocodone/acetaminophen and cyclobenzaprine. He was to be on bed rest for two days, remain home from work for two more days, and see his primary care provider in seven to 10 days if his condition had not resolved.

The man's pain became increasingly severe. He could not walk unaided, and after four days, he was pale or grayish in color, clammy, sweaty, and short of breath. On the fifth day, this US Army veteran kept an appointment at a US Air Force/university hospital–based clinic, where a second-year resident examined him, diagnosed muscle sprain, and prescribed a few more days of rest. The patient was not seen by the supervising physician.

The next day, the man was unable to urinate; the following day, he began to hallucinate. He was transported to an ED, where he was placed on life support. The day after his admission, CT confirmed the presence of a retroperitoneal (psoas) abscess and showed that the abscess was encroaching into the epidural space. By this time, his body had swelled to the point that his skin could no longer expand to accommodate it and had begun to crack.

A surgeon who was consulted diagnosed overwhelming sepsis, making the patient too unstable for surgery. By the time the decision was made to airlift him to the university hospital, the man was technically too heavy for the helicopter guidelines. He died one week later.

The case centered around a dispute regarding what the clinic's second-year resident had told the supervising physician regarding the decedent's symptoms. The court ultimately concluded that there was negligence on the part of both physicians, which led to the patient's death. According to a published report, a bench verdict of $8,265,009 was returned.

Infectious Mononucleosis Misdiagnosed as URI

A 19-year-old college student was treated by the defendant family practitioner, Dr. F., during repeated bouts of sinus infection and upper respiratory infection (URI). When the student's illness recurred in November while he was away at school, he was seen twice by an otolaryngologist. The student received a diagnosis of URI, for which he was given antibiotics and a steroid injection.

During the patient's winter break from school, he was still unwell. He called Dr. F.'s office for an appointment and was seen three days later. No lab work or tests were ordered, but Dr. F. made a diagnosis of strep throat and prescribed antibiotics. The student was also instructed that if his condition persisted or worsened, he should call Dr. F.

Two days later, the patient's mother phoned Dr. F.'s office to report that her son was experiencing severe abdominal pain. Because it was the weekend, the mother spoke with an on-call physician, who ordered a change in antibiotics. The patient's condition improved somewhat, but by the next afternoon, the pain had returned, and he was nauseated and vomiting.

He was taken to an ED, where a diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis was made. Less than an hour later, the patient went into cardiac arrest and died.

An autopsy revealed that the decedent's spleen had become enlarged to 10 times its normal size and ruptured, leading to massive internal bleeding and death.

The plaintiff alleged negligence in Dr. F.'s failure to diagnose infectious mononucleosis, claiming that the physician had not examined the decedent's abdomen during the office visit; had this examination been performed, the decedent's enlarged spleen would have been easily detected. The plaintiff further claimed that Dr. F.'s erroneous diagnosis had discouraged the decedent from seeking ED treatment when his condition first worsened.

The defendant denied any negligence, arguing that the decedent's death was an extremely rare complication of infectious mononucleosis and that the outcome would have been the same, even if the decedent had gone to the ED when his worsening symptoms began.

A defense verdict was returned.

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Oversedated, Unresponsive After Aneurysm Surgery

A 73-year-old man went to a hospital emergency department (ED) with complaints of chest pain, bloating, and blood in his stools. CT revealed an aortic aneurysm, and surgery was performed three days later. In the recovery room, the patient became confused and agitated. He managed to leave the building before several nurses were able to restrain him and return him to his room.

It was determined that the man was experiencing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, making him uncooperative and potentially violent. He was started on a detoxification protocol, which included lorazepam and haloperidol.

Over the next several days, the patient appeared oversedated and unresponsive, and his lorazepam dosage was reduced. When he developed a rattle in his chest and began to have trouble breathing, no action was taken. He went into respiratory arrest and was intubated; during this procedure, he sustained a punctured lung. Although the man was resuscitated, he was left with anoxic brain injury. He remained in a deep coma until his ventilator was turned off.

Plaintiffs for the decedent claimed that he was oversedated. He developed a mucous plug that he was unable to clear because of physical restraints and a decreased level of consciousness.

According to a published account, a settlement of $107,500 was reached.