User login

Malpractice minute: June POLL RESULTS

Could a patient’s violent act have been prevented?

A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. He killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26. The niece’s family claimed the death could have been prevented if the man was civilly committed or heavily medicated. Was the behavioral health authority liable?

⋥ LIABLE: 11% ⋥ NOT LIABLE: 89%

What did the court decide?

The mother was found to be 39% at fault, the patient 11% at fault, and the behavioral health authority 50% at fault for the woman’s death and paid half of the verdict amount to the parents. A $101,740 verdict was returned for the niece’s mother and a $100,625 verdict was returned for the father.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Could a patient’s violent act have been prevented?

A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. He killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26. The niece’s family claimed the death could have been prevented if the man was civilly committed or heavily medicated. Was the behavioral health authority liable?

⋥ LIABLE: 11% ⋥ NOT LIABLE: 89%

What did the court decide?

The mother was found to be 39% at fault, the patient 11% at fault, and the behavioral health authority 50% at fault for the woman’s death and paid half of the verdict amount to the parents. A $101,740 verdict was returned for the niece’s mother and a $100,625 verdict was returned for the father.

Could a patient’s violent act have been prevented?

A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. He killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26. The niece’s family claimed the death could have been prevented if the man was civilly committed or heavily medicated. Was the behavioral health authority liable?

⋥ LIABLE: 11% ⋥ NOT LIABLE: 89%

What did the court decide?

The mother was found to be 39% at fault, the patient 11% at fault, and the behavioral health authority 50% at fault for the woman’s death and paid half of the verdict amount to the parents. A $101,740 verdict was returned for the niece’s mother and a $100,625 verdict was returned for the father.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Divorce, custody, and parental consent for psychiatric treatment

Dear Dr. Mossman:

I treat children and adolescents in an acute inpatient setting. Sometimes a child of divorced parents—call him “Johnny”—is admitted to the hospital by one parent—for example the mother—but she doesn’t inform the father. Although the parents have joint custody, Mom doesn’t want me to contact Dad.

I tell Mom that I’d like to get clinical information and consent from Dad, but she refuses, saying, “This will make me look bad, and my ex-husband will try to take emergency custody of Johnny.” My hospital’s legal department says consent from both parents isn’t needed.

These scenarios always leave me feeling upset and confused. I’d appreciate clarification on how to handle these matters.—Submitted by “Dr. K”

Knowing the correct legal answer to a question often doesn’t supply the best clinical solution for your patient. Dr. K received a legally sound response from hospital administrators: a parent who has legal custody may authorize medical treatment for a minor child without first asking or informing the other parent. But Dr. K feels unsatisfied because the hospital didn’t provide what Dr. K sought: a clinically sound answer.

This article reviews custody arrangements and the legal rights they give divorced parents. Also, we will discuss the mother’s concerns and explain why—despite her fears—notifying and involving Johnny’s father can be important, even when it’s not legally required.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Custody and urgent treatment

A minor—defined in most states as a person younger than age 18—legally cannot give consent for medical care except in limited circumstances, such as contraceptive care.1,2 When a minor undergoes psychiatric hospitalization, physicians usually must obtain consent from the minor’s legal custodian.

Married parents both have legal custody of their children. They also have equal rights to spend time with their children and make major decisions about their welfare, such as authorizing medical care. When parents divorce, these rights must be reassigned in a court-approved divorce decree. Table 1 explains some key terms used to describe custody arrangements after divorce.2,3

Several decades ago, children—especially those younger age 10—usually remained with their mothers, who received sole legal custody; fathers typically had visitation privileges.4 Now, however, most states’ statutes presume that divorced mothers and fathers will have joint legal custody.3

Joint legal custody lets both parents retain their individual legal authority to make decisions on behalf of minor children, although the children may spend most of their time in the physical custody of 1 parent. This means that when urgent medical care is needed—such as a psychiatric hospitalization—1 parent’s consent is sufficient legal authorization for treatment.1,2

What if a child’s parent claims to have legal custody, but the doctor isn’t sure? A doctor who in good faith relies on a parent’s statement can properly provide urgent treatment without delving into custody arrangements.2 In many states, noncustodial parents may authorize treatment in urgent situations—and even some nonurgent ones—if they happen to have physical control of the child when care is needed, such as during a visit.1

Table 1

Child custody: Key legal terms

| Term | Refers to |

|---|---|

| Custody arrangement | The specified times each parent will spend with a minor child and which parent(s) can make major decisions about a child’s welfare |

| Legal custody | A parent’s right to make major decisions about a child’s welfare, including medical care |

| Visitation | The child’s means of maintaining contact with a noncustodial parent |

| Physical custody | Who has physical possession of the child at a particular time, such as during visitation |

| Sole legal custody | A custody arrangement in which only one parent retains the right to make major decisions for the child |

| Joint legal custody | A custody arrangement in which both parents retain the right to make major decisions affecting the child |

| Modification of custody | A legal process in which a court changes a previous custody order |

| Source: Adapted from references 2,3 | |

Nonurgent treatment

After receiving urgent treatment, psychiatric patients typically need continuing, nonurgent care. Dr. K’s inquiry may be anticipating this scenario. In general, parents with joint custody have an equal right to authorize nonurgent care for their children, and Johnny’s treatment could proceed with only Mom’s consent.1 However, if Dr. K knows or has reason to think that Johnny’s father would refuse to give consent for ongoing, nonurgent psychiatric care, providing treatment over the father’s objection may be legally questionable. Under some joint legal custody agreements, both parents need to give consent for medical care and receive clinical information about their children.2

Moreover, trying to treat Johnny in the face of Dad’s explicit objection may be clinically unwise. Unfortunately, many couples’ conflicts are not resolved by divorce, and children can become pawns in ongoing postmarital battles. Such situations can exacerbate children’s emotional problems, which is the opposite of what Dr. K hopes to do for Johnny.

What can Dr. K do?

Address a parent’s fears. Few parents are at their levelheaded best when their children need psychiatric hospitalization. To help Mom and Johnny, Dr. K can point out these things:

- Many states, such as Ohio,5 give Dad the right to learn about Johnny’s treatment and access to treatment records.

- Sooner or later, Dad will find out about the hospitalization. The next time Johnny visits his father, he’ll probably tell Dad what happened. In a few weeks, Dad may receive insurance paperwork or a bill from the hospital.

- Dad may be far more upset and prone to retaliate if he finds out later and is excluded from Johnny’s treatment than if he is notified immediately and gets to participate in his son’s care.

- Realistically, Dad cannot take Johnny away because Mom has arranged for appropriate medical care. If hospitalization is indicated, Mom’s failure to get treatment for Johnny could be grounds for Dad to claim she’s an unfit parent.

Why both parents are needed

Johnny’s hospital care probably will benefit from Dad’s involvement for several reasons (Table 2).

More information. Child and adolescent psychiatrists agree that in most clinical situations it helps to obtain information from as many sources as possible.6-9 Johnny’s father might have crucial information relevant to diagnosis or treatment, such as family history details that Mom doesn’t know.

Debiasing. If Johnny spends time living with both parents, Dr. K should know how often symptoms appear in both environments. Dad’s perspective may be vital, but when postdivorce relationships are strained, what parents convey about each other can be biased. Getting information directly from both parents will give Dr. K a more realistic picture of the child’s environment and psychosocial stressors.7

Treatment planning. After a psychiatric hospitalization, both parents should be aware of Johnny’s diagnosis and treatment. Johnny may need careful supervision for recurrence of symptoms, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, that can have life-threatening implications.

Medication management. If Johnny is taking medication, he’ll need to receive it regularly. Missing medication when Johnny is with Dad would reduce effectiveness and in some cases could be dangerous. Both parents also should know about possible side effects so they can provide good monitoring.

Psychotherapy. Often, family therapy is an important element of a child’s recovery and will achieve optimum results only if all family members participate. Also, children need consistency. If a behavioral plan is part of Johnny’s treatment, Mom and Dad will need to agree on the rules and implement them consistently at both homes.

Table 2

Why both parents’ input is valuable

| More information from different perspectives concerning behavior in a variety of contexts and settings |

| Less biased information |

| Better treatment planning |

| Better medication management |

| More effective therapy |

Work with parents

When one divorced parent is reluctant to inform the other about their child’s hospitalization, you can respond empathically to fears and concerns. Despite mental health professionals’ best efforts, psychiatric illness still generates feelings of stigma and shame. Divorced parents often feel guilty about the stress the divorce has brought to their children, and they may consciously or unconsciously blame themselves for their child’s illness. In the midst of an ongoing custody dispute, the parent initiating a psychiatric hospitalization may feel especially vulnerable and reluctant to inform the other parent about what’s happening.

Being attuned to these issues will help you address and normalize a parent’s fears. Parents should know that a court could support their seeking treatment for their children’s illness, and they could be contributing to medical neglect if they do not seek this treatment.

In rare instances, not informing the other parent may be the best clinical decision. In situations involving child abuse or extreme domestic violence, a parent’s learning about the hospitalization could create safety issues. In most instances, however, both Mom and Dad will see their child soon after hospitalization, so one parent cannot hope to conceal a hospitalization for very long. Involving both parents from the outset usually will give the child and his family the best shot at a positive outcome.

1. Berger JE. Consent by proxy for nonurgent pediatric care. Pediatrics 2003;112:1186-95.

2. Quinn KM, Weiner BA. Legal rights of children. In: Weiner BA, Wettstein RM, eds. Legal issues in mental health care. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993:309-47.

3. Kelly JB. The determination of child custody. Future Child 1994;4:121-242.

4. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, Slobogin C. Psychological evaluations for the courts: a handbook for mental health professionals and lawyers. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

5. Ohio Rev Code § 3109. 051(H).

6. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

7. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment of the family. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:922-37.

8. Bostic JQ, King RA. Clinical assessment of children and adolescents: content and structure. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, eds. Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:323-44.

9. Weston CG, Klykylo WM. The initial psychiatric evaluation of children and adolescents. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, eds. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:546-54.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

I treat children and adolescents in an acute inpatient setting. Sometimes a child of divorced parents—call him “Johnny”—is admitted to the hospital by one parent—for example the mother—but she doesn’t inform the father. Although the parents have joint custody, Mom doesn’t want me to contact Dad.

I tell Mom that I’d like to get clinical information and consent from Dad, but she refuses, saying, “This will make me look bad, and my ex-husband will try to take emergency custody of Johnny.” My hospital’s legal department says consent from both parents isn’t needed.

These scenarios always leave me feeling upset and confused. I’d appreciate clarification on how to handle these matters.—Submitted by “Dr. K”

Knowing the correct legal answer to a question often doesn’t supply the best clinical solution for your patient. Dr. K received a legally sound response from hospital administrators: a parent who has legal custody may authorize medical treatment for a minor child without first asking or informing the other parent. But Dr. K feels unsatisfied because the hospital didn’t provide what Dr. K sought: a clinically sound answer.

This article reviews custody arrangements and the legal rights they give divorced parents. Also, we will discuss the mother’s concerns and explain why—despite her fears—notifying and involving Johnny’s father can be important, even when it’s not legally required.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Custody and urgent treatment

A minor—defined in most states as a person younger than age 18—legally cannot give consent for medical care except in limited circumstances, such as contraceptive care.1,2 When a minor undergoes psychiatric hospitalization, physicians usually must obtain consent from the minor’s legal custodian.

Married parents both have legal custody of their children. They also have equal rights to spend time with their children and make major decisions about their welfare, such as authorizing medical care. When parents divorce, these rights must be reassigned in a court-approved divorce decree. Table 1 explains some key terms used to describe custody arrangements after divorce.2,3

Several decades ago, children—especially those younger age 10—usually remained with their mothers, who received sole legal custody; fathers typically had visitation privileges.4 Now, however, most states’ statutes presume that divorced mothers and fathers will have joint legal custody.3

Joint legal custody lets both parents retain their individual legal authority to make decisions on behalf of minor children, although the children may spend most of their time in the physical custody of 1 parent. This means that when urgent medical care is needed—such as a psychiatric hospitalization—1 parent’s consent is sufficient legal authorization for treatment.1,2

What if a child’s parent claims to have legal custody, but the doctor isn’t sure? A doctor who in good faith relies on a parent’s statement can properly provide urgent treatment without delving into custody arrangements.2 In many states, noncustodial parents may authorize treatment in urgent situations—and even some nonurgent ones—if they happen to have physical control of the child when care is needed, such as during a visit.1

Table 1

Child custody: Key legal terms

| Term | Refers to |

|---|---|

| Custody arrangement | The specified times each parent will spend with a minor child and which parent(s) can make major decisions about a child’s welfare |

| Legal custody | A parent’s right to make major decisions about a child’s welfare, including medical care |

| Visitation | The child’s means of maintaining contact with a noncustodial parent |

| Physical custody | Who has physical possession of the child at a particular time, such as during visitation |

| Sole legal custody | A custody arrangement in which only one parent retains the right to make major decisions for the child |

| Joint legal custody | A custody arrangement in which both parents retain the right to make major decisions affecting the child |

| Modification of custody | A legal process in which a court changes a previous custody order |

| Source: Adapted from references 2,3 | |

Nonurgent treatment

After receiving urgent treatment, psychiatric patients typically need continuing, nonurgent care. Dr. K’s inquiry may be anticipating this scenario. In general, parents with joint custody have an equal right to authorize nonurgent care for their children, and Johnny’s treatment could proceed with only Mom’s consent.1 However, if Dr. K knows or has reason to think that Johnny’s father would refuse to give consent for ongoing, nonurgent psychiatric care, providing treatment over the father’s objection may be legally questionable. Under some joint legal custody agreements, both parents need to give consent for medical care and receive clinical information about their children.2

Moreover, trying to treat Johnny in the face of Dad’s explicit objection may be clinically unwise. Unfortunately, many couples’ conflicts are not resolved by divorce, and children can become pawns in ongoing postmarital battles. Such situations can exacerbate children’s emotional problems, which is the opposite of what Dr. K hopes to do for Johnny.

What can Dr. K do?

Address a parent’s fears. Few parents are at their levelheaded best when their children need psychiatric hospitalization. To help Mom and Johnny, Dr. K can point out these things:

- Many states, such as Ohio,5 give Dad the right to learn about Johnny’s treatment and access to treatment records.

- Sooner or later, Dad will find out about the hospitalization. The next time Johnny visits his father, he’ll probably tell Dad what happened. In a few weeks, Dad may receive insurance paperwork or a bill from the hospital.

- Dad may be far more upset and prone to retaliate if he finds out later and is excluded from Johnny’s treatment than if he is notified immediately and gets to participate in his son’s care.

- Realistically, Dad cannot take Johnny away because Mom has arranged for appropriate medical care. If hospitalization is indicated, Mom’s failure to get treatment for Johnny could be grounds for Dad to claim she’s an unfit parent.

Why both parents are needed

Johnny’s hospital care probably will benefit from Dad’s involvement for several reasons (Table 2).

More information. Child and adolescent psychiatrists agree that in most clinical situations it helps to obtain information from as many sources as possible.6-9 Johnny’s father might have crucial information relevant to diagnosis or treatment, such as family history details that Mom doesn’t know.

Debiasing. If Johnny spends time living with both parents, Dr. K should know how often symptoms appear in both environments. Dad’s perspective may be vital, but when postdivorce relationships are strained, what parents convey about each other can be biased. Getting information directly from both parents will give Dr. K a more realistic picture of the child’s environment and psychosocial stressors.7

Treatment planning. After a psychiatric hospitalization, both parents should be aware of Johnny’s diagnosis and treatment. Johnny may need careful supervision for recurrence of symptoms, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, that can have life-threatening implications.

Medication management. If Johnny is taking medication, he’ll need to receive it regularly. Missing medication when Johnny is with Dad would reduce effectiveness and in some cases could be dangerous. Both parents also should know about possible side effects so they can provide good monitoring.

Psychotherapy. Often, family therapy is an important element of a child’s recovery and will achieve optimum results only if all family members participate. Also, children need consistency. If a behavioral plan is part of Johnny’s treatment, Mom and Dad will need to agree on the rules and implement them consistently at both homes.

Table 2

Why both parents’ input is valuable

| More information from different perspectives concerning behavior in a variety of contexts and settings |

| Less biased information |

| Better treatment planning |

| Better medication management |

| More effective therapy |

Work with parents

When one divorced parent is reluctant to inform the other about their child’s hospitalization, you can respond empathically to fears and concerns. Despite mental health professionals’ best efforts, psychiatric illness still generates feelings of stigma and shame. Divorced parents often feel guilty about the stress the divorce has brought to their children, and they may consciously or unconsciously blame themselves for their child’s illness. In the midst of an ongoing custody dispute, the parent initiating a psychiatric hospitalization may feel especially vulnerable and reluctant to inform the other parent about what’s happening.

Being attuned to these issues will help you address and normalize a parent’s fears. Parents should know that a court could support their seeking treatment for their children’s illness, and they could be contributing to medical neglect if they do not seek this treatment.

In rare instances, not informing the other parent may be the best clinical decision. In situations involving child abuse or extreme domestic violence, a parent’s learning about the hospitalization could create safety issues. In most instances, however, both Mom and Dad will see their child soon after hospitalization, so one parent cannot hope to conceal a hospitalization for very long. Involving both parents from the outset usually will give the child and his family the best shot at a positive outcome.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

I treat children and adolescents in an acute inpatient setting. Sometimes a child of divorced parents—call him “Johnny”—is admitted to the hospital by one parent—for example the mother—but she doesn’t inform the father. Although the parents have joint custody, Mom doesn’t want me to contact Dad.

I tell Mom that I’d like to get clinical information and consent from Dad, but she refuses, saying, “This will make me look bad, and my ex-husband will try to take emergency custody of Johnny.” My hospital’s legal department says consent from both parents isn’t needed.

These scenarios always leave me feeling upset and confused. I’d appreciate clarification on how to handle these matters.—Submitted by “Dr. K”

Knowing the correct legal answer to a question often doesn’t supply the best clinical solution for your patient. Dr. K received a legally sound response from hospital administrators: a parent who has legal custody may authorize medical treatment for a minor child without first asking or informing the other parent. But Dr. K feels unsatisfied because the hospital didn’t provide what Dr. K sought: a clinically sound answer.

This article reviews custody arrangements and the legal rights they give divorced parents. Also, we will discuss the mother’s concerns and explain why—despite her fears—notifying and involving Johnny’s father can be important, even when it’s not legally required.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Custody and urgent treatment

A minor—defined in most states as a person younger than age 18—legally cannot give consent for medical care except in limited circumstances, such as contraceptive care.1,2 When a minor undergoes psychiatric hospitalization, physicians usually must obtain consent from the minor’s legal custodian.

Married parents both have legal custody of their children. They also have equal rights to spend time with their children and make major decisions about their welfare, such as authorizing medical care. When parents divorce, these rights must be reassigned in a court-approved divorce decree. Table 1 explains some key terms used to describe custody arrangements after divorce.2,3

Several decades ago, children—especially those younger age 10—usually remained with their mothers, who received sole legal custody; fathers typically had visitation privileges.4 Now, however, most states’ statutes presume that divorced mothers and fathers will have joint legal custody.3

Joint legal custody lets both parents retain their individual legal authority to make decisions on behalf of minor children, although the children may spend most of their time in the physical custody of 1 parent. This means that when urgent medical care is needed—such as a psychiatric hospitalization—1 parent’s consent is sufficient legal authorization for treatment.1,2

What if a child’s parent claims to have legal custody, but the doctor isn’t sure? A doctor who in good faith relies on a parent’s statement can properly provide urgent treatment without delving into custody arrangements.2 In many states, noncustodial parents may authorize treatment in urgent situations—and even some nonurgent ones—if they happen to have physical control of the child when care is needed, such as during a visit.1

Table 1

Child custody: Key legal terms

| Term | Refers to |

|---|---|

| Custody arrangement | The specified times each parent will spend with a minor child and which parent(s) can make major decisions about a child’s welfare |

| Legal custody | A parent’s right to make major decisions about a child’s welfare, including medical care |

| Visitation | The child’s means of maintaining contact with a noncustodial parent |

| Physical custody | Who has physical possession of the child at a particular time, such as during visitation |

| Sole legal custody | A custody arrangement in which only one parent retains the right to make major decisions for the child |

| Joint legal custody | A custody arrangement in which both parents retain the right to make major decisions affecting the child |

| Modification of custody | A legal process in which a court changes a previous custody order |

| Source: Adapted from references 2,3 | |

Nonurgent treatment

After receiving urgent treatment, psychiatric patients typically need continuing, nonurgent care. Dr. K’s inquiry may be anticipating this scenario. In general, parents with joint custody have an equal right to authorize nonurgent care for their children, and Johnny’s treatment could proceed with only Mom’s consent.1 However, if Dr. K knows or has reason to think that Johnny’s father would refuse to give consent for ongoing, nonurgent psychiatric care, providing treatment over the father’s objection may be legally questionable. Under some joint legal custody agreements, both parents need to give consent for medical care and receive clinical information about their children.2

Moreover, trying to treat Johnny in the face of Dad’s explicit objection may be clinically unwise. Unfortunately, many couples’ conflicts are not resolved by divorce, and children can become pawns in ongoing postmarital battles. Such situations can exacerbate children’s emotional problems, which is the opposite of what Dr. K hopes to do for Johnny.

What can Dr. K do?

Address a parent’s fears. Few parents are at their levelheaded best when their children need psychiatric hospitalization. To help Mom and Johnny, Dr. K can point out these things:

- Many states, such as Ohio,5 give Dad the right to learn about Johnny’s treatment and access to treatment records.

- Sooner or later, Dad will find out about the hospitalization. The next time Johnny visits his father, he’ll probably tell Dad what happened. In a few weeks, Dad may receive insurance paperwork or a bill from the hospital.

- Dad may be far more upset and prone to retaliate if he finds out later and is excluded from Johnny’s treatment than if he is notified immediately and gets to participate in his son’s care.

- Realistically, Dad cannot take Johnny away because Mom has arranged for appropriate medical care. If hospitalization is indicated, Mom’s failure to get treatment for Johnny could be grounds for Dad to claim she’s an unfit parent.

Why both parents are needed

Johnny’s hospital care probably will benefit from Dad’s involvement for several reasons (Table 2).

More information. Child and adolescent psychiatrists agree that in most clinical situations it helps to obtain information from as many sources as possible.6-9 Johnny’s father might have crucial information relevant to diagnosis or treatment, such as family history details that Mom doesn’t know.

Debiasing. If Johnny spends time living with both parents, Dr. K should know how often symptoms appear in both environments. Dad’s perspective may be vital, but when postdivorce relationships are strained, what parents convey about each other can be biased. Getting information directly from both parents will give Dr. K a more realistic picture of the child’s environment and psychosocial stressors.7

Treatment planning. After a psychiatric hospitalization, both parents should be aware of Johnny’s diagnosis and treatment. Johnny may need careful supervision for recurrence of symptoms, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, that can have life-threatening implications.

Medication management. If Johnny is taking medication, he’ll need to receive it regularly. Missing medication when Johnny is with Dad would reduce effectiveness and in some cases could be dangerous. Both parents also should know about possible side effects so they can provide good monitoring.

Psychotherapy. Often, family therapy is an important element of a child’s recovery and will achieve optimum results only if all family members participate. Also, children need consistency. If a behavioral plan is part of Johnny’s treatment, Mom and Dad will need to agree on the rules and implement them consistently at both homes.

Table 2

Why both parents’ input is valuable

| More information from different perspectives concerning behavior in a variety of contexts and settings |

| Less biased information |

| Better treatment planning |

| Better medication management |

| More effective therapy |

Work with parents

When one divorced parent is reluctant to inform the other about their child’s hospitalization, you can respond empathically to fears and concerns. Despite mental health professionals’ best efforts, psychiatric illness still generates feelings of stigma and shame. Divorced parents often feel guilty about the stress the divorce has brought to their children, and they may consciously or unconsciously blame themselves for their child’s illness. In the midst of an ongoing custody dispute, the parent initiating a psychiatric hospitalization may feel especially vulnerable and reluctant to inform the other parent about what’s happening.

Being attuned to these issues will help you address and normalize a parent’s fears. Parents should know that a court could support their seeking treatment for their children’s illness, and they could be contributing to medical neglect if they do not seek this treatment.

In rare instances, not informing the other parent may be the best clinical decision. In situations involving child abuse or extreme domestic violence, a parent’s learning about the hospitalization could create safety issues. In most instances, however, both Mom and Dad will see their child soon after hospitalization, so one parent cannot hope to conceal a hospitalization for very long. Involving both parents from the outset usually will give the child and his family the best shot at a positive outcome.

1. Berger JE. Consent by proxy for nonurgent pediatric care. Pediatrics 2003;112:1186-95.

2. Quinn KM, Weiner BA. Legal rights of children. In: Weiner BA, Wettstein RM, eds. Legal issues in mental health care. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993:309-47.

3. Kelly JB. The determination of child custody. Future Child 1994;4:121-242.

4. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, Slobogin C. Psychological evaluations for the courts: a handbook for mental health professionals and lawyers. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

5. Ohio Rev Code § 3109. 051(H).

6. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

7. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment of the family. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:922-37.

8. Bostic JQ, King RA. Clinical assessment of children and adolescents: content and structure. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, eds. Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:323-44.

9. Weston CG, Klykylo WM. The initial psychiatric evaluation of children and adolescents. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, eds. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:546-54.

1. Berger JE. Consent by proxy for nonurgent pediatric care. Pediatrics 2003;112:1186-95.

2. Quinn KM, Weiner BA. Legal rights of children. In: Weiner BA, Wettstein RM, eds. Legal issues in mental health care. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993:309-47.

3. Kelly JB. The determination of child custody. Future Child 1994;4:121-242.

4. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, Slobogin C. Psychological evaluations for the courts: a handbook for mental health professionals and lawyers. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

5. Ohio Rev Code § 3109. 051(H).

6. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

7. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment of the family. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:922-37.

8. Bostic JQ, King RA. Clinical assessment of children and adolescents: content and structure. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, eds. Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:323-44.

9. Weston CG, Klykylo WM. The initial psychiatric evaluation of children and adolescents. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, eds. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:546-54.

We’re Hiring

At the 2008 SHM Annual Meeting in San Diego, I had the pleasure of serving as moderator for a panel commenting on the opportunities and challenges faced by hospitalists. I’m not sure how well our predictions will withstand the test of time, but two things came up that I’ll discuss here:

1) Nearly every group is recruiting, and many seem to think the hospitalist shortage will last throughout the careers of those in practice today.

2) Nearly all hospitalist groups are looking for more doctors. I asked the approximately 1,600 in attendance how many are recruiting for more hospitalists. Nearly every hand in the room shot up. It was impressive; one friend (Bob Reynolds) told me he was sitting in the back and could feel a breeze in the room from all the hands being raised. Only about three hands went up when I asked how many thought their staffing was adequate.

Bear in mind that based on the show of hands nearly every group in the country is recruiting. Many groups are looking to add three to six hospitalists this year alone. This is on top of the average group growing about 20% to 25% the past two years, based on my study of data from the “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement.” The survey showed the number of FTE doctors in the average hospitalist group grew from a median six to eight hospitalists (the average went from eight to 9.7).

Hospital medicine is the fastest-growing field in the history of American medicine, and it looks like the demand for hospitalists may be increasing even faster than the supply.

I was tempted to ask for a show of hands from doctors at the meeting who were looking for a hospitalist position, but feared it could disrupt the whole conference as those seeking new doctors pounced on the potential candidates in a piranha-like feeding frenzy. So there is good news for anyone interested in joining a hospitalist group: You should have a lot of choices. If you’re recruiting, you’d better get to work to make sure you have really good plan. Let me offer a few ideas.

Never stop recruiting. Dr. Greg Mappin, VPMA at Self Regional Hospital in Greenwood, S.C., told me his philosophy is to “recruit forever, and hire when necessary.” I agree.

You should build and maintain a robust candidate pipeline by ensuring your practice maintains a high level of visibility before your best source of new doctors. The best source for most groups is the closest residency training program, though other nearby hospitalist or outpatient practices might be a secondary source of new manpower.

I suggest you engage residents by hosting a dinner near their hospital once or twice a year and inviting all second- and third-year residents to attend regardless of their interest in becoming hospitalists. You might do this even in years you may not need to add hospitalists to ensure your dinner becomes a regular event for them and to ensure they’re very familiar with your program. Some hospitals develop night and weekend moonlighting programs that employ nearby residents, which increases the chance some will join the practice upon completion of their training.

Ensure all hospitalists—especially the group leader—actively participate in recruiting. Your hospital or medical group’s physician recruiter can be a terrific asset. He/she can provide advice regarding how to find candidates, arranging interviews, etc. Yet, it is critical for the hospitalist group leader to actively communicate with every candidate, including responding to every inquiry within a day or so.

Too many group leaders make a big mistake by waiting many days to respond to new inquiries, or letting the recruiter handle all communication in advance of an interview. During the interview, be sure the candidate spends time with many of the current group members and provides contact information for every group member in case the candidate would like to call any who weren’t available on the interview day. Consider providing the candidate with a copy of the group schedule, any orientation documents you have, and other such printed materials to review after the visit.

Recruit specifically for short-term members of your practice. Despite concerns about turnover, I think it is reasonable to actively pursue candidates who may have as little as two years to work in your practice. For example, they may plan to move to another town (e.g., when their spouse finishes training) or start fellowship training. In my experience, at least half of new doctors who plan to be a hospitalist for only a year or two will choose to stay on long term.

If you want your classified ad to stand out, think about writing one that specifically targets short-term hospitalists. It could say something like: “Do you have only two years to work as a hospitalist? Then this is the place for you.” You even could add benefits, such as tuition to attend conferences that would be of value for the doctor regardless of their future specialty or practice setting. If you desperately need additional doctors, get creative in recruiting those who plan to stay with you for only a couple years. I’m confident some will end up staying long term.

Continue “recruiting” the doctors in your practice. For a number of reasons, hospitalist turnover may be higher than most other specialties. So it is particularly important to take steps to minimize it. SHM’s white paper on hospitalist career satisfaction (“A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction”) offers observations and valuable suggestions for any practice. Find it under the “Publications” link on SHM’s Web site, www. hospitalmedicine.org.

No End to Shortage

Now back to that panel discussion at SHM’s Annual Meeting in April. I asked the panelists what things would be like if in 10 years the demand for hospitalists decreased, and the supply finally caught up with and ultimately exceeded demand.

I thought this could be a provocative question that would lead to a discussion about how much of our current situation, such as recent increases in hospital financial support provided per hospitalist, are due to the current hospitalist shortage. Will hospitals decrease their support if there is ever an excess of hospitalists?

No one was buying it. Everyone was convinced that despite the incredible growth in numbers of doctors practicing as hospitalists, the demand for hospitalists will continue to grow even faster than the supply. Panelist Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, chief medical officer of Cogent Healthcare in Irvine, Calif., thought this hospitalist shortage would continue throughout our lifetime. I’m not sure how long Ron thinks he (or I) will live, but that’s a pretty bold prediction.

It looks like the current intense recruiting environment is here to stay for a long time. Every practice should be thinking about how best to manage it. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

At the 2008 SHM Annual Meeting in San Diego, I had the pleasure of serving as moderator for a panel commenting on the opportunities and challenges faced by hospitalists. I’m not sure how well our predictions will withstand the test of time, but two things came up that I’ll discuss here:

1) Nearly every group is recruiting, and many seem to think the hospitalist shortage will last throughout the careers of those in practice today.

2) Nearly all hospitalist groups are looking for more doctors. I asked the approximately 1,600 in attendance how many are recruiting for more hospitalists. Nearly every hand in the room shot up. It was impressive; one friend (Bob Reynolds) told me he was sitting in the back and could feel a breeze in the room from all the hands being raised. Only about three hands went up when I asked how many thought their staffing was adequate.

Bear in mind that based on the show of hands nearly every group in the country is recruiting. Many groups are looking to add three to six hospitalists this year alone. This is on top of the average group growing about 20% to 25% the past two years, based on my study of data from the “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement.” The survey showed the number of FTE doctors in the average hospitalist group grew from a median six to eight hospitalists (the average went from eight to 9.7).

Hospital medicine is the fastest-growing field in the history of American medicine, and it looks like the demand for hospitalists may be increasing even faster than the supply.

I was tempted to ask for a show of hands from doctors at the meeting who were looking for a hospitalist position, but feared it could disrupt the whole conference as those seeking new doctors pounced on the potential candidates in a piranha-like feeding frenzy. So there is good news for anyone interested in joining a hospitalist group: You should have a lot of choices. If you’re recruiting, you’d better get to work to make sure you have really good plan. Let me offer a few ideas.

Never stop recruiting. Dr. Greg Mappin, VPMA at Self Regional Hospital in Greenwood, S.C., told me his philosophy is to “recruit forever, and hire when necessary.” I agree.

You should build and maintain a robust candidate pipeline by ensuring your practice maintains a high level of visibility before your best source of new doctors. The best source for most groups is the closest residency training program, though other nearby hospitalist or outpatient practices might be a secondary source of new manpower.

I suggest you engage residents by hosting a dinner near their hospital once or twice a year and inviting all second- and third-year residents to attend regardless of their interest in becoming hospitalists. You might do this even in years you may not need to add hospitalists to ensure your dinner becomes a regular event for them and to ensure they’re very familiar with your program. Some hospitals develop night and weekend moonlighting programs that employ nearby residents, which increases the chance some will join the practice upon completion of their training.

Ensure all hospitalists—especially the group leader—actively participate in recruiting. Your hospital or medical group’s physician recruiter can be a terrific asset. He/she can provide advice regarding how to find candidates, arranging interviews, etc. Yet, it is critical for the hospitalist group leader to actively communicate with every candidate, including responding to every inquiry within a day or so.

Too many group leaders make a big mistake by waiting many days to respond to new inquiries, or letting the recruiter handle all communication in advance of an interview. During the interview, be sure the candidate spends time with many of the current group members and provides contact information for every group member in case the candidate would like to call any who weren’t available on the interview day. Consider providing the candidate with a copy of the group schedule, any orientation documents you have, and other such printed materials to review after the visit.

Recruit specifically for short-term members of your practice. Despite concerns about turnover, I think it is reasonable to actively pursue candidates who may have as little as two years to work in your practice. For example, they may plan to move to another town (e.g., when their spouse finishes training) or start fellowship training. In my experience, at least half of new doctors who plan to be a hospitalist for only a year or two will choose to stay on long term.

If you want your classified ad to stand out, think about writing one that specifically targets short-term hospitalists. It could say something like: “Do you have only two years to work as a hospitalist? Then this is the place for you.” You even could add benefits, such as tuition to attend conferences that would be of value for the doctor regardless of their future specialty or practice setting. If you desperately need additional doctors, get creative in recruiting those who plan to stay with you for only a couple years. I’m confident some will end up staying long term.

Continue “recruiting” the doctors in your practice. For a number of reasons, hospitalist turnover may be higher than most other specialties. So it is particularly important to take steps to minimize it. SHM’s white paper on hospitalist career satisfaction (“A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction”) offers observations and valuable suggestions for any practice. Find it under the “Publications” link on SHM’s Web site, www. hospitalmedicine.org.

No End to Shortage

Now back to that panel discussion at SHM’s Annual Meeting in April. I asked the panelists what things would be like if in 10 years the demand for hospitalists decreased, and the supply finally caught up with and ultimately exceeded demand.

I thought this could be a provocative question that would lead to a discussion about how much of our current situation, such as recent increases in hospital financial support provided per hospitalist, are due to the current hospitalist shortage. Will hospitals decrease their support if there is ever an excess of hospitalists?

No one was buying it. Everyone was convinced that despite the incredible growth in numbers of doctors practicing as hospitalists, the demand for hospitalists will continue to grow even faster than the supply. Panelist Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, chief medical officer of Cogent Healthcare in Irvine, Calif., thought this hospitalist shortage would continue throughout our lifetime. I’m not sure how long Ron thinks he (or I) will live, but that’s a pretty bold prediction.

It looks like the current intense recruiting environment is here to stay for a long time. Every practice should be thinking about how best to manage it. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

At the 2008 SHM Annual Meeting in San Diego, I had the pleasure of serving as moderator for a panel commenting on the opportunities and challenges faced by hospitalists. I’m not sure how well our predictions will withstand the test of time, but two things came up that I’ll discuss here:

1) Nearly every group is recruiting, and many seem to think the hospitalist shortage will last throughout the careers of those in practice today.

2) Nearly all hospitalist groups are looking for more doctors. I asked the approximately 1,600 in attendance how many are recruiting for more hospitalists. Nearly every hand in the room shot up. It was impressive; one friend (Bob Reynolds) told me he was sitting in the back and could feel a breeze in the room from all the hands being raised. Only about three hands went up when I asked how many thought their staffing was adequate.

Bear in mind that based on the show of hands nearly every group in the country is recruiting. Many groups are looking to add three to six hospitalists this year alone. This is on top of the average group growing about 20% to 25% the past two years, based on my study of data from the “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement.” The survey showed the number of FTE doctors in the average hospitalist group grew from a median six to eight hospitalists (the average went from eight to 9.7).

Hospital medicine is the fastest-growing field in the history of American medicine, and it looks like the demand for hospitalists may be increasing even faster than the supply.

I was tempted to ask for a show of hands from doctors at the meeting who were looking for a hospitalist position, but feared it could disrupt the whole conference as those seeking new doctors pounced on the potential candidates in a piranha-like feeding frenzy. So there is good news for anyone interested in joining a hospitalist group: You should have a lot of choices. If you’re recruiting, you’d better get to work to make sure you have really good plan. Let me offer a few ideas.

Never stop recruiting. Dr. Greg Mappin, VPMA at Self Regional Hospital in Greenwood, S.C., told me his philosophy is to “recruit forever, and hire when necessary.” I agree.

You should build and maintain a robust candidate pipeline by ensuring your practice maintains a high level of visibility before your best source of new doctors. The best source for most groups is the closest residency training program, though other nearby hospitalist or outpatient practices might be a secondary source of new manpower.

I suggest you engage residents by hosting a dinner near their hospital once or twice a year and inviting all second- and third-year residents to attend regardless of their interest in becoming hospitalists. You might do this even in years you may not need to add hospitalists to ensure your dinner becomes a regular event for them and to ensure they’re very familiar with your program. Some hospitals develop night and weekend moonlighting programs that employ nearby residents, which increases the chance some will join the practice upon completion of their training.

Ensure all hospitalists—especially the group leader—actively participate in recruiting. Your hospital or medical group’s physician recruiter can be a terrific asset. He/she can provide advice regarding how to find candidates, arranging interviews, etc. Yet, it is critical for the hospitalist group leader to actively communicate with every candidate, including responding to every inquiry within a day or so.

Too many group leaders make a big mistake by waiting many days to respond to new inquiries, or letting the recruiter handle all communication in advance of an interview. During the interview, be sure the candidate spends time with many of the current group members and provides contact information for every group member in case the candidate would like to call any who weren’t available on the interview day. Consider providing the candidate with a copy of the group schedule, any orientation documents you have, and other such printed materials to review after the visit.

Recruit specifically for short-term members of your practice. Despite concerns about turnover, I think it is reasonable to actively pursue candidates who may have as little as two years to work in your practice. For example, they may plan to move to another town (e.g., when their spouse finishes training) or start fellowship training. In my experience, at least half of new doctors who plan to be a hospitalist for only a year or two will choose to stay on long term.

If you want your classified ad to stand out, think about writing one that specifically targets short-term hospitalists. It could say something like: “Do you have only two years to work as a hospitalist? Then this is the place for you.” You even could add benefits, such as tuition to attend conferences that would be of value for the doctor regardless of their future specialty or practice setting. If you desperately need additional doctors, get creative in recruiting those who plan to stay with you for only a couple years. I’m confident some will end up staying long term.

Continue “recruiting” the doctors in your practice. For a number of reasons, hospitalist turnover may be higher than most other specialties. So it is particularly important to take steps to minimize it. SHM’s white paper on hospitalist career satisfaction (“A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction”) offers observations and valuable suggestions for any practice. Find it under the “Publications” link on SHM’s Web site, www. hospitalmedicine.org.

No End to Shortage

Now back to that panel discussion at SHM’s Annual Meeting in April. I asked the panelists what things would be like if in 10 years the demand for hospitalists decreased, and the supply finally caught up with and ultimately exceeded demand.

I thought this could be a provocative question that would lead to a discussion about how much of our current situation, such as recent increases in hospital financial support provided per hospitalist, are due to the current hospitalist shortage. Will hospitals decrease their support if there is ever an excess of hospitalists?

No one was buying it. Everyone was convinced that despite the incredible growth in numbers of doctors practicing as hospitalists, the demand for hospitalists will continue to grow even faster than the supply. Panelist Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, chief medical officer of Cogent Healthcare in Irvine, Calif., thought this hospitalist shortage would continue throughout our lifetime. I’m not sure how long Ron thinks he (or I) will live, but that’s a pretty bold prediction.

It looks like the current intense recruiting environment is here to stay for a long time. Every practice should be thinking about how best to manage it. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

How can we Reduce Indwelling Urinary Catheter Use and Complications?

Case

A 68-year-old male with a history of Alzheimer’s dementia and incontinence presents with failure to thrive. A Foley catheter is placed due to the patient’s incontinence and fall risk. Three days after admission while awaiting placement in a skilled nursing facility (SNF), he develops a urinary tract infection (UTI) complicated by delirium delaying his transfer to the SNF. What could have been done to prevent this complication?

Overview

It has been 50 years since Beeson, et al., recognized the potential harms stemming from urethral catheterization and penned an editorial to the American Journal of Medicine titled “The case against the catheter.”1

Since then, there has been considerable exploration of ways to limit urethral catheterization and ultimately decrease catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs). Unfortunately, little progress has been made; indwelling urinary catheters remain ubiquitous in hospitals and CAUTIs remain the most common hospital-acquired infection in the United States.2 Given the emphasis on the quality and costs of healthcare, it is an opportune time to revisit catheter management and use as a way to combat the clinical and economic consequences of CAUTIs.

Clinicians may be lulled into thinking the clinical impact of CAUTI is less than that of other nosocomial infections. However, beyond the obvious patient harm from UTIs, associated bacteremia, and even death, the public health implications of CAUTI cannot be denied. Urinary tract infections constitute 40% of all nosocomial infections; accounting for an estimated 1 million cases annually.3 Further, 80% of all UTIs are associated with indwelling catheter use.

On average, nosocomial UTI necessitates one extra hospital day per patient, or approximately one million excess hospital days per year.4 Pooled cost analysis shows that UTIs consume an additional $400-$1,700 per event, or an estimated $425 million per year in the United States.5,6 Clearly, we cannot wait another 50 years to address this problem.

Review of the Data

Catheter duration as a risk factor for CAUTI: The indwelling catheter creates a portal of entry into a usually sterile body cavity and provides a surface on which microorganisms can colonize. At a finite rate of colonization—the incidence of bacteriuria is 3% to 10% per catheter day—the duration of urinary catheterization becomes the strongest predictor of catheter-associated bacteriuria.7 Even in relatively short-term catheter use of two to 10 days, the pooled cumulative incidence of developing bacteriuria is 26%.

Given the magnitude of these numbers, it should be no surprise that after one month of catheterization, bacteriuria develops in almost all patients. Twenty-four percent of patients with bacteriuria develop symptomatic UTIs with close to 5% suffering bacteremia. Consequently, nosocomial UTIs cause 15% of all hospital-acquired bacteremia.

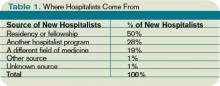

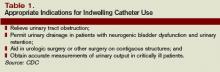

Optimal catheter management: The easiest and most effective means to prevent CAUTI is to limit the use of urinary catheters to clearly identified medical indications (see Table 1, above). However, as simple as this prevention practice may sound, studies have demonstrated that as many as 20% of patients have indwelling catheters initially placed for unjustified or even unknown medical indications.8 Additionally, continued catheter use is inappropriate in one-third to one-half of all catheter days.9 These data confirm misuse and overuse of indwelling urinary catheters in the hospital setting is common.

In 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognized the importance of addressing this situation and published a guideline to aid prevention of CAUTIs.10 The CDC urged the limitation of catheter use to a carefully selected patient population. Furthermore, the report strongly stressed the importance of catheter removal as soon as possible and advised against the use of catheters solely for the convenience of healthcare workers.

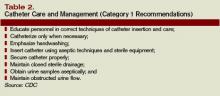

Evidence-based techniques for insertion and catheter care also were outlined in the guideline (see Table 2, p. 31). However, these recommendations have been poorly implemented, likely due to the competing priorities of providers and the difficulty operationalizing the guidelines. Additionally, evidence from the intervening 25 years has not yet been incorporated into the guideline, although a revision currently is underway.

Until that revision is complete, the Joanna Briggs Institute guideline published in 2001 addresses some of the same management techniques and incorporates newer evidence.11 Of note, practices that have been discredited due to contradictory evidence include aggressive meatal cleaning, bladder irrigation, and the application of antimicrobial agents in the drainage bag.12

Strategies to reduce unnecessary catheter days: One of the remediable reasons for catheter misuse lies in the fact physicians often are unaware of the presence of an indwelling catheter in their hospitalized patients.

Saint, et al., showed physicians were unaware of catheterization in 28% of their patients and that attending physicians were less conscious of a patient’s catheter status than residents, interns, or medical students.13 Further, the “forgotten” catheters were more likely to be unnecessary than those remembered by the healthcare team.

This information has prompted the use of various computer-based and multidisciplinary feedback protocols to readdress and re-evaluate the need for continued catheterization in a patient. For example, a study at the VAMC Puget Sound demonstrated that having a computerized order protocol for urinary catheters significantly increased the rate of documentation as well as decreased the duration of catheterization by an average of three days.14

Similar interventions to encourage early catheter removal have included daily reminders from nursing staff, allowing a nurse to discontinue catheter use independent of a physician’s order, and feedback in which nursing staff is educated about the incidence of UTI.15-17 All these relatively simple interventions showed significant improvement in the catheter removal rate and incidence of CAUTIs as well as documented cost savings.

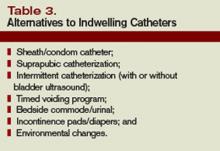

Alternatives to indwelling catheters: In addition to efforts to decrease catheter days, alternatives to the indwelling catheters also should be explored. One such alternative method is intermittent catheterization.

Several studies in postoperative patients with hip fractures have demonstrated that the development of UTI is lower with intermittent catheterization when compared with indwelling catheterization.18 Nevertheless, since the risk of bacteriuria is 1% to 3% per episode of catheterization, after a few weeks the majority of patients will have bacteriuria. However, as the bulk of this bacteriuria often is asymptomatic, intermittent catheterization may still be an improvement. This is particularly true in postoperative patients undergoing rehabilitation and those patients only requiring catheterization for a limited number of days.

More recent studies have evaluated the use of bedside bladder ultrasound in an attempt to determine when intermittent catheterization is needed and thereby limit its use compared with standard timed catheterization. Frederickson, et al., demonstrated that this intervention resulted in significantly fewer catheterizations in surgical patients, thus delaying or avoiding the need for catheterization in 81% of the cases.19 Given this drastic improvement, it is no surprise bladder ultrasound use reduced the rates of UTI.20

External condom catheters present another alternative to indwelling catheter use but the outcomes data is conflicting. While the risk of bacteriuria is approximately 12% per month, this rate becomes increasingly higher with frequent manipulation of the condom catheter. 21,22

Two parallel cohort studies in a VA nursing home showed the incidence of symptomatic UTI to be 2.5 times greater in men with an indwelling catheter than those with a condom catheter.23 On the other hand, a cross-sectional Danish study reported higher rates of UTI with external condom catheters than urethral catheters in hospitalized patients.24 Complications from condom catheters include phimosis and local skin maceration, necessitating meticulous care with the use of these devices. Although the data surrounding external catheterization is somewhat contradictory, this device warrants consideration in incontinent males without urinary tract obstruction.

There are several other alternatives to urethral catheterization (see Table 3, p. 31), many of which have excellent face validity even in the absence of rigorous evidence.

Antimicrobial catheters: The development of antimicrobial urinary catheters, including silver-alloy and nitrofurazone-coated catheters, has been greeted with much excitement, however, the jury is still out about their best use. A 2006 systematic literature review reported that in comparison to standard catheters, antimicrobial catheters can delay or even prevent the development of bacteriuria with short-term usage.25

However, not all antimicrobial catheters are equally effective; assorted studies lack data about clinically relevant endpoints such as prevention of symptomatic UTI, bloodstream infection or death.26, 27 In addition, there are no good trials comparing nitrofurazone to silver-alloy catheters. Therefore, the level of excitement surrounding antimicrobial catheters—particularly silver-alloy catheters—must be tempered by the additional costs incurred by their use.

To date, the cost-effectiveness of antimicrobial catheters has not been demonstrated. Although additional research in this topic is still needed, some experts currently recommend the consideration of silver-alloy catheters in patients at the highest risk for developing serious consequences from UTIs.

Efforts to reduce CAUTI: In response to significant public interest in hospital-acquired infections including CAUTI, the federal government and many state governments are beginning to demand change. In August 2007, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services instituted a mandate making hospitals financially responsible for selected preventable hospital-acquired harms, including CAUTIs.28 In addition, beginning with Pennsylvania in 2006, several states have mandated public reporting of hospital-acquired infections.29

Given the available information about CAUTI prevalence, risks, and preventive techniques, it is surprising the majority of hospitals in the United States have not taken appropriate measures to limit indwelling catheter use. A recent study by Saint, et al., demonstrated the startling fact that only a minority of hospitals monitor the use of urethral catheters in their patients.30

Among study hospitals, there was no widely used technique to prevent CAUTI including evidence-based practices such as daily catheter reminders. The results of this investigation illustrate the urgent need for a national strategy to reduce CAUTI. Until that time, however, hospital-based physicians must take the lead to champion collaborative efforts, to promote evidence-based catheter use.

Back to the Case

As incontinence and fall risk are not medically appropriate indications for a urethral catheter, a Foley catheter should not have been utilized. Alternatives to indwelling catheterization in this patient would include a bedside commode with nursing assistance, a timed voiding program, intermittent catheterization with or without bladder ultrasound, incontinence pads, or a condom catheter.

Attentiveness to the appropriate medical indications for catheter use, familiarity with catheter alternatives, and recognition of the clinical and economic impact of CAUTI may have prevented this patient’s UTI-induced delirium and facilitated his early transfer to SNF. TH

Dr. Wald is a getriatric hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver. Dr. Furfari is a hospital medicine fellow at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Beeson PB. The case against the catheter. Am J Med. 1958;24:1-3.

- Saint S. Clinical and economic consequences of nosocomial catheter-related bacteriuria. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28:68-75.

- Sedor J, Mulholland SG. Hospital-acquired UTIs associated with the indwelling catheter. Urol Clin North Am. 1999;26:821-828.

- Foxman B. Epidemiology of UTI: Incidence, morbidity and economic costs. Am J Med. 2002;113(1A):5S-13S.

- Tambyah PA, Knasinski V, Maki D. The direct costs of nosocomial catheter-associated UTI in the era of managed care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:27-31.

- Jarvis, WR. Selected aspects of socioeconomic impact of nosocomial infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996;17:552-557.

- Warren JW. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997;11:609-622.

- Jain P, Parada JP, David A, Smith L. Overuse of the indwelling urinary catheter in hospitalized medical patients. Arch Internal Med. 1995;155:1425-1429.

- Hartstein AI, Garber SB, Ward TT, Jones SR, Morthland VH. Nosocomial urinary tract infection: a prospective evaluation of 108 catheterized patients. Infect Control. 1981;2:380-386.

- Wong E. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Center for Disease Control and Prevention 1981. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/gl_catheter_assoc.html . Accessed May 8, 2008.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Management of short term indwelling urethral catheters to prevent urinary tract infections. 2000;4(1):ISSN 1329-1874.

- Burke JP, Garibaldi RA, Britt MR, Jacobson JA, Conti M, Alling DW. Prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Am J Med. 1981;70:655-658.

- Saint S, Wiese J, Amory JK, et al. Are physicians aware of which of their patients have indwelling urinary catheters? Am J Med. 2000;109:476-480.

- Cornia PB, Amory JK, Fraser S, Saint S, Lipsky BA. Computer-based order entry decreases duration of indwelling urinary catheterization in hospitalized patients. Am J Med. 2003;114:404-406.

- Huang WC, Wann SR, Lin SL, et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensive care units can be reduced by prompting physicians to remove unnecessary catheters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(11):974-978.

- Topal J, Conklin S, Camp K, Morris TB, Herbert P. Prevention of nosocomial catheter-associated urinary tract infections through computerized feedback to physicians and a nurse-directed protocol. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(3):121-126.

- Goetz AM, Kedzuf S, Wagener M, Muder R. Feedback to nursing staff as an intervention to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(5):402-404.

- Johansson I, Athlin E, Frykholm L, Bolinder H, Larsson G. Intermittent versus indwelling catheters for older patients with hip fractures. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11:651-656.

- Frederickson M, Neitzel JJ, Miller EH, Reuter S, Graner T, Heller J. The implementation of bedside bladder ultrasound technology: Effects of patient and cost postoperative outcomes in tertiary care. Orthop Nurs. 2000;19(3):79-87.

- Slappendel R, Weber EWG. Non-invasive measurement of bladder volume as an indication for bladder catheterization after orthopedic surgery and its effect on urinary tract infections. Eur J Anesthesiol. 1999;16:503-506.

- Hirsh D, Fainstein V, Musher DM. Do condom catheter collecting systems cause urinary tract infections? JAMA. 1979;242:340-341.

- Wong ES. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Am J Infect Control. 1983;11:28-36.

- Saint S, Lipsky BA. Preventing catheter-related bacteriuria. Should We? Can We? How? Arch Internal Med. 1999;159:800-808.

- Zimakoff J, Stickler DJ, Pontoppidan B, Larsen SO. Bladder management and urinary tract infection in Danish hospitals, nursing homes and home care: A national prevalence study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996;17(4):215-221.

- Johnson JR, Kuskowski MA, Wilt TJ. Systematic Review: Antimicrobial urinary catheters to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients. Ann Internal Med. 2006;144(2):116-126.

- Saint S, Elmore JG, Sullivan SD, Emerson SS, Koepsell TD. The efficacy of silver alloy-coated urinary catheters in preventing urinary tract infections; a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 1998;105(3):236-241.

- Bronahan J, Jull A, Tracy C. Cochrane incontinence group. Types of urethral catheters for management of short-term voiding problems in hospitalized adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:CD004013.

- Wald HL, Kramer AM. Nonpayment for harms resulting from medical care. JAMA. 2007;298(23):2782-2784.

- Goldstein J. Hospital infections’ cost tallied. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Nov. 15, 2006.

- Saint S, Kowalski CP, Kaufman SR, et al. Preventing hospital-acquired urinary tract infection in the United States: A national study. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(2):243-250.

Case

A 68-year-old male with a history of Alzheimer’s dementia and incontinence presents with failure to thrive. A Foley catheter is placed due to the patient’s incontinence and fall risk. Three days after admission while awaiting placement in a skilled nursing facility (SNF), he develops a urinary tract infection (UTI) complicated by delirium delaying his transfer to the SNF. What could have been done to prevent this complication?

Overview

It has been 50 years since Beeson, et al., recognized the potential harms stemming from urethral catheterization and penned an editorial to the American Journal of Medicine titled “The case against the catheter.”1

Since then, there has been considerable exploration of ways to limit urethral catheterization and ultimately decrease catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs). Unfortunately, little progress has been made; indwelling urinary catheters remain ubiquitous in hospitals and CAUTIs remain the most common hospital-acquired infection in the United States.2 Given the emphasis on the quality and costs of healthcare, it is an opportune time to revisit catheter management and use as a way to combat the clinical and economic consequences of CAUTIs.