User login

What is the best antibiotic treatment for C.difficile-associated diarrhea?

Case

An 84-year-old woman presents with watery diarrhea. She recently received a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a hospitalization for pneumonia. Her temperature is 101 degrees, her heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute. Her abdominal exam is significant for mild distention, hyperactive bowel sounds, and diffuse, mild tenderness without rebound or guarding. Her white blood cell count is 18,200 cells/mm3. You suspect C. difficile infection. Should you treat empirically with antibiotics and, if so, which antibiotic should you prescribe?

Overview

C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that produces spores and toxins. In 1978, C. difficile was identified as the causative agent for antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 The portal of entry is via the fecal-oral route.

Some patients carry C. difficile in their intestinal flora and show no signs of infection. Patients who develop symptoms commonly present with profuse, watery diarrhea. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain also can be seen. Severe cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) can present with significant abdominal pain and multisystem organ failure, with toxic megacolon resulting from toxin production and ileus.2 In severe cases due to ileus, diarrhea may be absent. Risk of mortality in severe cases is high, with some reviews citing death rates of 57% in patients requiring total colectomy.3 Risk factors for developing CDAD include the prior or current use of antibiotics, advanced age, hospitalization, and prior gastrointestinal surgery or procedures.4

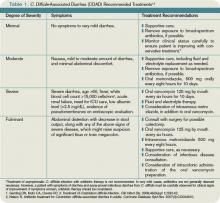

The initial CDAD treatment involves removal of the agent that incited the infection. In most cases, this means discontinuation of an antimicrobial agent. Removal of the inciting agent allows restoration of the normal bowel flora. In mild CDAD cases, this may be sufficient therapy. However, most CDAD cases require treatment. Although many antimicrobial and probiotic agents have been used in CDAD treatment, metronidazole and vancomycin are the most commonly prescribed agents. There is an ongoing debate as to which should be considered the first-line agent.

Review of the Data

Metronidazole and vancomycin have the longest histories of use and are the most studied agents in CDAD. Metronidazole is prescribed 250 mg four times daily (or 500 mg twice daily) for 14 days. It is reasonably tolerated, although it can cause a metallic taste in the mouth. Vancomycin is given 125 mg four times daily (or 500 mg three times daily) for 10 to 14 days. Unlike metronidazole, which can be given by mouth or intravenously, only oral vancomycin is effective in CDAD.

Historically, metronidazole has been prescribed more frequently as the first-line agent in CDAD. Proponents of the drug tout its low cost and the importance of minimizing the development of vancomycin-resistant enteric pathogens. There are two small, prospective, randomized studies comparing the efficacy of the agents against one another in the treatment of C. difficile infection, with similar efficacy demonstrated in both studies. In the early 1980s, Teasley and colleagues randomized 94 patients with C. difficile infection to either metronidazole or vancomycin.5 All the patients receiving vancomycin resolved their disease; 95% of patients receiving metronidazole were cured. The differences were not statistically significant.

In the mid-1990s, Wenisch and colleagues randomized patients with C. difficile infection to receive vancomycin, metronidazole, fusidic acid, or teicoplanin therapy.6 Ninety-four percent of patients in both the vancomycin and metronidazole groups were cured.

However, since 2000, investigators have reported higher failure rates with metronidazole therapy in C. difficile infections. For example, in 2005, Pepin and colleagues reviewed cases of C. difficile infections at a hospital in Quebec.7 They determined the number of patients with C. difficile infection initially treated with metronidazole who required additional therapy had markedly increased. Between 1991 and 2002, 9.6% of patients who initially were treated with metronidazole required a switch to vancomycin (or the addition of vancomycin) because of a disappointing response. This figure doubled to 25.7% in 2003-2004. The 60-day probability of recurrence also increased in the 2003-2004 test group (47.2%), compared with the 1991-2002 group (20.8%). Both results were statistically significant. Such data contributed to the debate regarding whether metronidazole or vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of C. difficile infections.

In 2007, Zar and colleagues studied the efficacy of metronidazole and vancomycin in the treatment of CDAD patients, but the study stratified patients according to disease severity.8 This allowed the authors to investigate whether one agent was superior in treating mild or severe CDAD. They determined disease severity by assigning points to individual patient characteristics. Patients with two or more points were deemed to have “severe” CDAD.

The investigators assigned one point for each of the following patient characteristics: temperature >38.3 degrees Celsius, age >60 years, albumin level <2.5 mg/dL, and white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3 within 48 hours of enrolling in the study. Any patient with endoscopic evidence of pseudomembrane formation or admission to the intensive-care unit (ICU) for CDAD treatment was considered to have severe disease.

This was a prospective, randomized controlled trial of 150 patients. Patients were randomly prescribed 500 mg metronidazole by mouth three times daily or 125 mg of vancomycin by mouth four times daily. Patients with mild CDAD had similar cure rates: 90% metronidazole versus 98% vancomycin (P=0.36). However, patients with severe CDAD fared statistically better when treated with oral vancomycin. Ninety-seven percent of severe CDAD patients treated with oral vancomycin had a clinical cure, while only 76% of those treated with metronidazole were cured (P=0.02). Recurrence of the disease was similar in each treatment group.

Based on this study, metronidazole and vancomycin appear equally effective in the treatment of mild CDAD, but vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of patients with severe CDAD.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors predisposing her to developing CDAD. She was of advanced age and took a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a recent hospitalization. She also presented with signs consistent with a severe case of CDAD. She had a fever, a white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3, and was older than 60. Thus, she should be treated with supportive care, placed on contact precautions, and administered oral vancomycin 125 mg by mouth every six hours for 10 days as empiric therapy for CDAD. Stool cultures should be sent to confirm the presence of the C. difficile toxin.

Bottom Line

The appropriate antibiotic choice to treat CDAD in any patient depends upon the clinical severity of the disease. Treat patients with mild CDAD with metronidazole; prescribe oral vancomycin for patients with severe CDAD. TH

Dr. Mattison, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is a hospitalist and co-director of the Inpatient Geriatrics Unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. Dr. Li, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is director of hospital medicine and associate chief of BIDMC’s Division of General Medicine and Primary Care.

References

1.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. Role of C. difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(5):778-782.

2.Poutanen SM, Simor AE. C. difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):51-58.

3.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant C. difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363-372.

4.Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of C. difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):758-764.

5.Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-1046.

6.Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Hasenhündl M, Hirschl AM, Graninger W. Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:813-818.

7.Pepin J, Alary M, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of C. difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1591-1597.

8.Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):302-307.

Case

An 84-year-old woman presents with watery diarrhea. She recently received a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a hospitalization for pneumonia. Her temperature is 101 degrees, her heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute. Her abdominal exam is significant for mild distention, hyperactive bowel sounds, and diffuse, mild tenderness without rebound or guarding. Her white blood cell count is 18,200 cells/mm3. You suspect C. difficile infection. Should you treat empirically with antibiotics and, if so, which antibiotic should you prescribe?

Overview

C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that produces spores and toxins. In 1978, C. difficile was identified as the causative agent for antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 The portal of entry is via the fecal-oral route.

Some patients carry C. difficile in their intestinal flora and show no signs of infection. Patients who develop symptoms commonly present with profuse, watery diarrhea. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain also can be seen. Severe cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) can present with significant abdominal pain and multisystem organ failure, with toxic megacolon resulting from toxin production and ileus.2 In severe cases due to ileus, diarrhea may be absent. Risk of mortality in severe cases is high, with some reviews citing death rates of 57% in patients requiring total colectomy.3 Risk factors for developing CDAD include the prior or current use of antibiotics, advanced age, hospitalization, and prior gastrointestinal surgery or procedures.4

The initial CDAD treatment involves removal of the agent that incited the infection. In most cases, this means discontinuation of an antimicrobial agent. Removal of the inciting agent allows restoration of the normal bowel flora. In mild CDAD cases, this may be sufficient therapy. However, most CDAD cases require treatment. Although many antimicrobial and probiotic agents have been used in CDAD treatment, metronidazole and vancomycin are the most commonly prescribed agents. There is an ongoing debate as to which should be considered the first-line agent.

Review of the Data

Metronidazole and vancomycin have the longest histories of use and are the most studied agents in CDAD. Metronidazole is prescribed 250 mg four times daily (or 500 mg twice daily) for 14 days. It is reasonably tolerated, although it can cause a metallic taste in the mouth. Vancomycin is given 125 mg four times daily (or 500 mg three times daily) for 10 to 14 days. Unlike metronidazole, which can be given by mouth or intravenously, only oral vancomycin is effective in CDAD.

Historically, metronidazole has been prescribed more frequently as the first-line agent in CDAD. Proponents of the drug tout its low cost and the importance of minimizing the development of vancomycin-resistant enteric pathogens. There are two small, prospective, randomized studies comparing the efficacy of the agents against one another in the treatment of C. difficile infection, with similar efficacy demonstrated in both studies. In the early 1980s, Teasley and colleagues randomized 94 patients with C. difficile infection to either metronidazole or vancomycin.5 All the patients receiving vancomycin resolved their disease; 95% of patients receiving metronidazole were cured. The differences were not statistically significant.

In the mid-1990s, Wenisch and colleagues randomized patients with C. difficile infection to receive vancomycin, metronidazole, fusidic acid, or teicoplanin therapy.6 Ninety-four percent of patients in both the vancomycin and metronidazole groups were cured.

However, since 2000, investigators have reported higher failure rates with metronidazole therapy in C. difficile infections. For example, in 2005, Pepin and colleagues reviewed cases of C. difficile infections at a hospital in Quebec.7 They determined the number of patients with C. difficile infection initially treated with metronidazole who required additional therapy had markedly increased. Between 1991 and 2002, 9.6% of patients who initially were treated with metronidazole required a switch to vancomycin (or the addition of vancomycin) because of a disappointing response. This figure doubled to 25.7% in 2003-2004. The 60-day probability of recurrence also increased in the 2003-2004 test group (47.2%), compared with the 1991-2002 group (20.8%). Both results were statistically significant. Such data contributed to the debate regarding whether metronidazole or vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of C. difficile infections.

In 2007, Zar and colleagues studied the efficacy of metronidazole and vancomycin in the treatment of CDAD patients, but the study stratified patients according to disease severity.8 This allowed the authors to investigate whether one agent was superior in treating mild or severe CDAD. They determined disease severity by assigning points to individual patient characteristics. Patients with two or more points were deemed to have “severe” CDAD.

The investigators assigned one point for each of the following patient characteristics: temperature >38.3 degrees Celsius, age >60 years, albumin level <2.5 mg/dL, and white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3 within 48 hours of enrolling in the study. Any patient with endoscopic evidence of pseudomembrane formation or admission to the intensive-care unit (ICU) for CDAD treatment was considered to have severe disease.

This was a prospective, randomized controlled trial of 150 patients. Patients were randomly prescribed 500 mg metronidazole by mouth three times daily or 125 mg of vancomycin by mouth four times daily. Patients with mild CDAD had similar cure rates: 90% metronidazole versus 98% vancomycin (P=0.36). However, patients with severe CDAD fared statistically better when treated with oral vancomycin. Ninety-seven percent of severe CDAD patients treated with oral vancomycin had a clinical cure, while only 76% of those treated with metronidazole were cured (P=0.02). Recurrence of the disease was similar in each treatment group.

Based on this study, metronidazole and vancomycin appear equally effective in the treatment of mild CDAD, but vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of patients with severe CDAD.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors predisposing her to developing CDAD. She was of advanced age and took a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a recent hospitalization. She also presented with signs consistent with a severe case of CDAD. She had a fever, a white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3, and was older than 60. Thus, she should be treated with supportive care, placed on contact precautions, and administered oral vancomycin 125 mg by mouth every six hours for 10 days as empiric therapy for CDAD. Stool cultures should be sent to confirm the presence of the C. difficile toxin.

Bottom Line

The appropriate antibiotic choice to treat CDAD in any patient depends upon the clinical severity of the disease. Treat patients with mild CDAD with metronidazole; prescribe oral vancomycin for patients with severe CDAD. TH

Dr. Mattison, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is a hospitalist and co-director of the Inpatient Geriatrics Unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. Dr. Li, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is director of hospital medicine and associate chief of BIDMC’s Division of General Medicine and Primary Care.

References

1.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. Role of C. difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(5):778-782.

2.Poutanen SM, Simor AE. C. difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):51-58.

3.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant C. difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363-372.

4.Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of C. difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):758-764.

5.Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-1046.

6.Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Hasenhündl M, Hirschl AM, Graninger W. Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:813-818.

7.Pepin J, Alary M, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of C. difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1591-1597.

8.Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):302-307.

Case

An 84-year-old woman presents with watery diarrhea. She recently received a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a hospitalization for pneumonia. Her temperature is 101 degrees, her heart rate is 110 beats per minute, and her respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute. Her abdominal exam is significant for mild distention, hyperactive bowel sounds, and diffuse, mild tenderness without rebound or guarding. Her white blood cell count is 18,200 cells/mm3. You suspect C. difficile infection. Should you treat empirically with antibiotics and, if so, which antibiotic should you prescribe?

Overview

C. difficile is an anaerobic gram-positive bacillus that produces spores and toxins. In 1978, C. difficile was identified as the causative agent for antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 The portal of entry is via the fecal-oral route.

Some patients carry C. difficile in their intestinal flora and show no signs of infection. Patients who develop symptoms commonly present with profuse, watery diarrhea. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain also can be seen. Severe cases of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) can present with significant abdominal pain and multisystem organ failure, with toxic megacolon resulting from toxin production and ileus.2 In severe cases due to ileus, diarrhea may be absent. Risk of mortality in severe cases is high, with some reviews citing death rates of 57% in patients requiring total colectomy.3 Risk factors for developing CDAD include the prior or current use of antibiotics, advanced age, hospitalization, and prior gastrointestinal surgery or procedures.4

The initial CDAD treatment involves removal of the agent that incited the infection. In most cases, this means discontinuation of an antimicrobial agent. Removal of the inciting agent allows restoration of the normal bowel flora. In mild CDAD cases, this may be sufficient therapy. However, most CDAD cases require treatment. Although many antimicrobial and probiotic agents have been used in CDAD treatment, metronidazole and vancomycin are the most commonly prescribed agents. There is an ongoing debate as to which should be considered the first-line agent.

Review of the Data

Metronidazole and vancomycin have the longest histories of use and are the most studied agents in CDAD. Metronidazole is prescribed 250 mg four times daily (or 500 mg twice daily) for 14 days. It is reasonably tolerated, although it can cause a metallic taste in the mouth. Vancomycin is given 125 mg four times daily (or 500 mg three times daily) for 10 to 14 days. Unlike metronidazole, which can be given by mouth or intravenously, only oral vancomycin is effective in CDAD.

Historically, metronidazole has been prescribed more frequently as the first-line agent in CDAD. Proponents of the drug tout its low cost and the importance of minimizing the development of vancomycin-resistant enteric pathogens. There are two small, prospective, randomized studies comparing the efficacy of the agents against one another in the treatment of C. difficile infection, with similar efficacy demonstrated in both studies. In the early 1980s, Teasley and colleagues randomized 94 patients with C. difficile infection to either metronidazole or vancomycin.5 All the patients receiving vancomycin resolved their disease; 95% of patients receiving metronidazole were cured. The differences were not statistically significant.

In the mid-1990s, Wenisch and colleagues randomized patients with C. difficile infection to receive vancomycin, metronidazole, fusidic acid, or teicoplanin therapy.6 Ninety-four percent of patients in both the vancomycin and metronidazole groups were cured.

However, since 2000, investigators have reported higher failure rates with metronidazole therapy in C. difficile infections. For example, in 2005, Pepin and colleagues reviewed cases of C. difficile infections at a hospital in Quebec.7 They determined the number of patients with C. difficile infection initially treated with metronidazole who required additional therapy had markedly increased. Between 1991 and 2002, 9.6% of patients who initially were treated with metronidazole required a switch to vancomycin (or the addition of vancomycin) because of a disappointing response. This figure doubled to 25.7% in 2003-2004. The 60-day probability of recurrence also increased in the 2003-2004 test group (47.2%), compared with the 1991-2002 group (20.8%). Both results were statistically significant. Such data contributed to the debate regarding whether metronidazole or vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of C. difficile infections.

In 2007, Zar and colleagues studied the efficacy of metronidazole and vancomycin in the treatment of CDAD patients, but the study stratified patients according to disease severity.8 This allowed the authors to investigate whether one agent was superior in treating mild or severe CDAD. They determined disease severity by assigning points to individual patient characteristics. Patients with two or more points were deemed to have “severe” CDAD.

The investigators assigned one point for each of the following patient characteristics: temperature >38.3 degrees Celsius, age >60 years, albumin level <2.5 mg/dL, and white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3 within 48 hours of enrolling in the study. Any patient with endoscopic evidence of pseudomembrane formation or admission to the intensive-care unit (ICU) for CDAD treatment was considered to have severe disease.

This was a prospective, randomized controlled trial of 150 patients. Patients were randomly prescribed 500 mg metronidazole by mouth three times daily or 125 mg of vancomycin by mouth four times daily. Patients with mild CDAD had similar cure rates: 90% metronidazole versus 98% vancomycin (P=0.36). However, patients with severe CDAD fared statistically better when treated with oral vancomycin. Ninety-seven percent of severe CDAD patients treated with oral vancomycin had a clinical cure, while only 76% of those treated with metronidazole were cured (P=0.02). Recurrence of the disease was similar in each treatment group.

Based on this study, metronidazole and vancomycin appear equally effective in the treatment of mild CDAD, but vancomycin is the superior agent in the treatment of patients with severe CDAD.

Back to the Case

Our patient had several risk factors predisposing her to developing CDAD. She was of advanced age and took a fluoroquinolone antibiotic during a recent hospitalization. She also presented with signs consistent with a severe case of CDAD. She had a fever, a white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mm3, and was older than 60. Thus, she should be treated with supportive care, placed on contact precautions, and administered oral vancomycin 125 mg by mouth every six hours for 10 days as empiric therapy for CDAD. Stool cultures should be sent to confirm the presence of the C. difficile toxin.

Bottom Line

The appropriate antibiotic choice to treat CDAD in any patient depends upon the clinical severity of the disease. Treat patients with mild CDAD with metronidazole; prescribe oral vancomycin for patients with severe CDAD. TH

Dr. Mattison, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is a hospitalist and co-director of the Inpatient Geriatrics Unit at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. Dr. Li, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, is director of hospital medicine and associate chief of BIDMC’s Division of General Medicine and Primary Care.

References

1.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. Role of C. difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(5):778-782.

2.Poutanen SM, Simor AE. C. difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):51-58.

3.Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ, et al. Fulminant C. difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications. Ann Surg. 2002;235(3):363-372.

4.Bartlett JG. Narrative review: the new epidemic of C. difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):758-764.

5.Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-1046.

6.Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Hasenhündl M, Hirschl AM, Graninger W. Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:813-818.

7.Pepin J, Alary M, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of C. difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1591-1597.

8.Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of C. difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):302-307.

Why off-label isn’t off base

This article is adapted from the February 2009 issue of Current Psychiatry, a Quadrant HealthCom Inc. publication.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE

A physician speaking with a colleague expressed his anxiety and uncertainty over off-label prescribing:

“When I was a resident, attending physicians occasionally cited journal articles in their consultation notes to substantiate their treatment choices. Since then, I’ve done this at times when I’ve prescribed a drug off label.

“Recently, I mentioned this practice to a physician who is trained as a lawyer. He thought citing articles in a patient’s chart was a bad idea, because by doing so I was automatically making the referred-to article the ‘expert witness.’ If a lawsuit occurred, I might be called upon to justify the article’s validity, statistical details, methodology, etc. My intent is to show that I have a detailed, well-thought-out justification for my treatment choice.

“Am I placing myself at greater risk of incurring liability should a lawsuit occur?”

This physician wants to know how he can minimize malpractice risk when prescribing a medication off label. He wonders if citing an article in a patient’s chart is a good—or bad—idea.

In law school, attorneys-in-training learn to answer very general legal questions with “It depends.” There’s little certainty about how to avoid successful malpractice litigation because few, if any, strategies have been tested systematically. However, this article will explain and, I hope, help you avoid the medicolegal pitfalls of off-label prescribing.

Limited testing for safety and effectiveness. Experiences such as the fen-phen (weight loss) controversy1 and estrogens for preventing vascular disease in postmenopausal women2 remind physicians that some untested treatments may do more harm than good.

Commercial influence. Pharmaceutical companies have used advisory boards, consultant meetings, and continuing medical education events to promote unproven off-label indications for drugs.3,4 Many studies that were, ostensibly, designed and proposed by researchers show evidence of so-called ghost authorship by commercial concerns.5

Study bias. Even peer-reviewed, double-blind studies that are published in the medical literature might not sufficiently support off-label prescribing practices because sponsors of such studies can structure them or use statistical analyses to make results look favorable. Former editors of the British Medical Journal and The Lancet have acknowledged that their publications unwittingly served as “an extension of the marketing arm” or “laundering operations” for drug manufacturers.6,7 Even for FDA-approved indications, a selective, positive-result publication bias and nonreporting of negative results may make drugs seem more effective than the full range of studies would justify.8

Legal use of labeling. Although off-label prescribing is accepted medical practice, doctors “may be found negligent if their decision to use a drug off label is sufficiently careless, imprudent, or unprofessional.”9 During a malpractice lawsuit, plaintiff’s counsel could try to use FDA-approved labeling or prescribing information to establish a presumptive standard of care. Such evidence usually is admissible if it is supported by expert testimony. The burden of proof is then placed on the defendant physician to show how an off-label use met the standard of care.10

References

1. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

2. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

3. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.-

4. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

5. Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.-

6. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.-

7. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

8. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

9. Richardson v Miller. 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

10. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

Off-label: Accepted and necessary

Off-label prescribing occurs when a physician prescribes a medication or uses a medical device outside the scope of FDA-approved labeling. Most commonly, off-label use involves prescribing a medication for something other than its FDA-approved indication. An example is sildenafil [Viagra] for women who have antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.1

Other examples are prescribing a drug:

- at an unapproved dose

- in an unapproved format (e.g., mixing capsule contents with applesauce)

- outside the approved age group

- for longer than the approved interval

- at a different dose schedule (e.g., qhs instead of bid or tid).

Typically, it takes years for a new drug to gain FDA approval and additional time for an already-approved drug to gain approval for a new indication. In the meantime, clinicians treat their patients with available drugs prescribed off label.

Off-label prescribing is legal. FDA approval means drugs may be sold and marketed in specific ways. But the FDA does not tell physicians how they can use approved drugs. As each edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference explains, “Once a product has been approved for marketing, a physician may prescribe it for uses or in treatment regimens or patient populations that are not included in approved labeling.”2 Federal statutes state that FDA approval does not “limit or interfere with the authority of a health care practitioner to prescribe” approved drugs or devices “for any condition or disease.”3

- Know why an article applies to your patient. If you are sued for malpractice, you can use an article to support your treatment choice by explaining how this information contributed to your decision-making.

- Tell your patient that the proposed treatment is an off-label use when you obtain consent, even though case law says you don’t have to do this. Telling your patient helps him understand your reasoning and prevents surprises that may give offense.

- Engage in ongoing informed consent. Uncertainty is part of medical practice and is heightened when physicians prescribe off label. Ongoing discussions help patients understand, accept, and share that uncertainty.

- Document informed consent. This will show—if it becomes necessary—that you and your patient made collaborative, conscientious decisions about treatment.1

Reference

1. Royal College of Psychiatrists. CR142. Use of unlicensed medicine for unlicensed applications in psychiatric practice. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/collegereports/cr/cr142.aspx. Accessed March 4, 2009.

Does off-label constitute malpractice?

Off-label use is not only legal—it’s often wise medical practice. Many drug uses that now have FDA approval were off label just a few years ago. Examples include using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat panic disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Fluoxetine is the only FDA-approved drug for treating depression in adolescents, but other SSRIs may also have a favorable risk–benefit profile.6

The practice is common—we know that

Numerous studies have shown that off-label prescribing is common in, for example, psychiatry7 and other specialties.8,9 Because the practice is so common, the mere fact that a drug is not FDA-approved for a particular use does not imply that the drug was prescribed negligently.

Some commentators have suggested that off-label prescribing amounts to human experimentation.10 Without FDA approval, they say, physicians lack hard evidence, so to speak, that a product is safe and effective—making off-label prescribing a small-scale clinical trial based on the doctor’s educated guesses.

If this reasoning is correct, off-label prescribing would require the same human subject protections used in research, including institutional review board approval and special consent forms.

Although this argument sounds plausible, off-label prescribing is not experimentation or research (see “4 reasons why off-label prescribing can be controversial”).4,11-19 Researchers investigate hypotheses to obtain generalizable knowledge, whereas medical therapy aims to benefit individual patients. This experimentation–therapy distinction is not perfect because successful off-label treatment of one patient might imply beneficial effects for others.10 When courts have looked at this matter, though, they have found that “off-label use… by a physician seeking an optimal treatment for his or her patient is not necessarily…research or an investigational or experimental treatment when the use is customarily followed by physicians.”4

Courts also have said that off-label use does not require special informed consent. Just because a drug is prescribed off label doesn’t mean it’s risky. FDA approval “is not a material risk inherently involved in a proposed therapy which a physician should have disclosed to a patient prior to the therapy.”20 In other words, a physician is not required to discuss FDA regulatory status—such as off-label uses of a medication—to comply with standards of informed consent. FDA regulatory status has nothing to do with the risks or benefits of a medication and it does not provide information about treatment alternatives.21

What should you do?

For advice on protecting yourself when you prescribe off label, see the box above.

In addition, you should keep abreast of news and scientific evidence concerning drug uses, effects, interactions, and adverse effects, especially when prescribing for uses that are different from the manufacturer’s intended purposes.22

Last, collect articles on off-label uses, but keep them separate from your patients’ files. Good attorneys are highly skilled at using documents to score legal points, and opposing counsel will prepare questions to focus on the articles’ faults or limitations in isolation.

1. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

2. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62nd ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, Inc.; 2007.

3. Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21USC §396

4. Richardson v Miller. 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

5. Buckman Co. v Plaintiffs’ Legal Comm., 531 US 341 (2001).

6. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

7. Baldwin DS, Kosky N. Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13:414-422.

8. Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. European Network for Drug Investigation in Children. BMJ. 2000;320:79-82.

9. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021-1026.

10. Mehlman MJ. Off-label prescribing. Available at: http://www.thedoctorwillseeyounow.com/articles/bioethics/offlabel_11. Accessed October 21, 2008.

11. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

12. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

13. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.-

14. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

15. Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.-

16. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.-

17. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

18. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

19. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

20. Klein v Biscup. 673 NE2d 225 (Ohio App 1996).

21. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent: debunking myths and misconceptions. Food Drug Law J. 1998;53:71-104.

22. Shajnfeld A, Krueger RB. Reforming (purportedly) non-punitive responses to sexual offending. Dev Mental Health Law. 2006;25:81-99.

This article is adapted from the February 2009 issue of Current Psychiatry, a Quadrant HealthCom Inc. publication.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE

A physician speaking with a colleague expressed his anxiety and uncertainty over off-label prescribing:

“When I was a resident, attending physicians occasionally cited journal articles in their consultation notes to substantiate their treatment choices. Since then, I’ve done this at times when I’ve prescribed a drug off label.

“Recently, I mentioned this practice to a physician who is trained as a lawyer. He thought citing articles in a patient’s chart was a bad idea, because by doing so I was automatically making the referred-to article the ‘expert witness.’ If a lawsuit occurred, I might be called upon to justify the article’s validity, statistical details, methodology, etc. My intent is to show that I have a detailed, well-thought-out justification for my treatment choice.

“Am I placing myself at greater risk of incurring liability should a lawsuit occur?”

This physician wants to know how he can minimize malpractice risk when prescribing a medication off label. He wonders if citing an article in a patient’s chart is a good—or bad—idea.

In law school, attorneys-in-training learn to answer very general legal questions with “It depends.” There’s little certainty about how to avoid successful malpractice litigation because few, if any, strategies have been tested systematically. However, this article will explain and, I hope, help you avoid the medicolegal pitfalls of off-label prescribing.

Limited testing for safety and effectiveness. Experiences such as the fen-phen (weight loss) controversy1 and estrogens for preventing vascular disease in postmenopausal women2 remind physicians that some untested treatments may do more harm than good.

Commercial influence. Pharmaceutical companies have used advisory boards, consultant meetings, and continuing medical education events to promote unproven off-label indications for drugs.3,4 Many studies that were, ostensibly, designed and proposed by researchers show evidence of so-called ghost authorship by commercial concerns.5

Study bias. Even peer-reviewed, double-blind studies that are published in the medical literature might not sufficiently support off-label prescribing practices because sponsors of such studies can structure them or use statistical analyses to make results look favorable. Former editors of the British Medical Journal and The Lancet have acknowledged that their publications unwittingly served as “an extension of the marketing arm” or “laundering operations” for drug manufacturers.6,7 Even for FDA-approved indications, a selective, positive-result publication bias and nonreporting of negative results may make drugs seem more effective than the full range of studies would justify.8

Legal use of labeling. Although off-label prescribing is accepted medical practice, doctors “may be found negligent if their decision to use a drug off label is sufficiently careless, imprudent, or unprofessional.”9 During a malpractice lawsuit, plaintiff’s counsel could try to use FDA-approved labeling or prescribing information to establish a presumptive standard of care. Such evidence usually is admissible if it is supported by expert testimony. The burden of proof is then placed on the defendant physician to show how an off-label use met the standard of care.10

References

1. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

2. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

3. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.-

4. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

5. Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.-

6. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.-

7. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

8. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

9. Richardson v Miller. 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

10. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

Off-label: Accepted and necessary

Off-label prescribing occurs when a physician prescribes a medication or uses a medical device outside the scope of FDA-approved labeling. Most commonly, off-label use involves prescribing a medication for something other than its FDA-approved indication. An example is sildenafil [Viagra] for women who have antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.1

Other examples are prescribing a drug:

- at an unapproved dose

- in an unapproved format (e.g., mixing capsule contents with applesauce)

- outside the approved age group

- for longer than the approved interval

- at a different dose schedule (e.g., qhs instead of bid or tid).

Typically, it takes years for a new drug to gain FDA approval and additional time for an already-approved drug to gain approval for a new indication. In the meantime, clinicians treat their patients with available drugs prescribed off label.

Off-label prescribing is legal. FDA approval means drugs may be sold and marketed in specific ways. But the FDA does not tell physicians how they can use approved drugs. As each edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference explains, “Once a product has been approved for marketing, a physician may prescribe it for uses or in treatment regimens or patient populations that are not included in approved labeling.”2 Federal statutes state that FDA approval does not “limit or interfere with the authority of a health care practitioner to prescribe” approved drugs or devices “for any condition or disease.”3

- Know why an article applies to your patient. If you are sued for malpractice, you can use an article to support your treatment choice by explaining how this information contributed to your decision-making.

- Tell your patient that the proposed treatment is an off-label use when you obtain consent, even though case law says you don’t have to do this. Telling your patient helps him understand your reasoning and prevents surprises that may give offense.

- Engage in ongoing informed consent. Uncertainty is part of medical practice and is heightened when physicians prescribe off label. Ongoing discussions help patients understand, accept, and share that uncertainty.

- Document informed consent. This will show—if it becomes necessary—that you and your patient made collaborative, conscientious decisions about treatment.1

Reference

1. Royal College of Psychiatrists. CR142. Use of unlicensed medicine for unlicensed applications in psychiatric practice. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/collegereports/cr/cr142.aspx. Accessed March 4, 2009.

Does off-label constitute malpractice?

Off-label use is not only legal—it’s often wise medical practice. Many drug uses that now have FDA approval were off label just a few years ago. Examples include using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat panic disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Fluoxetine is the only FDA-approved drug for treating depression in adolescents, but other SSRIs may also have a favorable risk–benefit profile.6

The practice is common—we know that

Numerous studies have shown that off-label prescribing is common in, for example, psychiatry7 and other specialties.8,9 Because the practice is so common, the mere fact that a drug is not FDA-approved for a particular use does not imply that the drug was prescribed negligently.

Some commentators have suggested that off-label prescribing amounts to human experimentation.10 Without FDA approval, they say, physicians lack hard evidence, so to speak, that a product is safe and effective—making off-label prescribing a small-scale clinical trial based on the doctor’s educated guesses.

If this reasoning is correct, off-label prescribing would require the same human subject protections used in research, including institutional review board approval and special consent forms.

Although this argument sounds plausible, off-label prescribing is not experimentation or research (see “4 reasons why off-label prescribing can be controversial”).4,11-19 Researchers investigate hypotheses to obtain generalizable knowledge, whereas medical therapy aims to benefit individual patients. This experimentation–therapy distinction is not perfect because successful off-label treatment of one patient might imply beneficial effects for others.10 When courts have looked at this matter, though, they have found that “off-label use… by a physician seeking an optimal treatment for his or her patient is not necessarily…research or an investigational or experimental treatment when the use is customarily followed by physicians.”4

Courts also have said that off-label use does not require special informed consent. Just because a drug is prescribed off label doesn’t mean it’s risky. FDA approval “is not a material risk inherently involved in a proposed therapy which a physician should have disclosed to a patient prior to the therapy.”20 In other words, a physician is not required to discuss FDA regulatory status—such as off-label uses of a medication—to comply with standards of informed consent. FDA regulatory status has nothing to do with the risks or benefits of a medication and it does not provide information about treatment alternatives.21

What should you do?

For advice on protecting yourself when you prescribe off label, see the box above.

In addition, you should keep abreast of news and scientific evidence concerning drug uses, effects, interactions, and adverse effects, especially when prescribing for uses that are different from the manufacturer’s intended purposes.22

Last, collect articles on off-label uses, but keep them separate from your patients’ files. Good attorneys are highly skilled at using documents to score legal points, and opposing counsel will prepare questions to focus on the articles’ faults or limitations in isolation.

This article is adapted from the February 2009 issue of Current Psychiatry, a Quadrant HealthCom Inc. publication.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE

A physician speaking with a colleague expressed his anxiety and uncertainty over off-label prescribing:

“When I was a resident, attending physicians occasionally cited journal articles in their consultation notes to substantiate their treatment choices. Since then, I’ve done this at times when I’ve prescribed a drug off label.

“Recently, I mentioned this practice to a physician who is trained as a lawyer. He thought citing articles in a patient’s chart was a bad idea, because by doing so I was automatically making the referred-to article the ‘expert witness.’ If a lawsuit occurred, I might be called upon to justify the article’s validity, statistical details, methodology, etc. My intent is to show that I have a detailed, well-thought-out justification for my treatment choice.

“Am I placing myself at greater risk of incurring liability should a lawsuit occur?”

This physician wants to know how he can minimize malpractice risk when prescribing a medication off label. He wonders if citing an article in a patient’s chart is a good—or bad—idea.

In law school, attorneys-in-training learn to answer very general legal questions with “It depends.” There’s little certainty about how to avoid successful malpractice litigation because few, if any, strategies have been tested systematically. However, this article will explain and, I hope, help you avoid the medicolegal pitfalls of off-label prescribing.

Limited testing for safety and effectiveness. Experiences such as the fen-phen (weight loss) controversy1 and estrogens for preventing vascular disease in postmenopausal women2 remind physicians that some untested treatments may do more harm than good.

Commercial influence. Pharmaceutical companies have used advisory boards, consultant meetings, and continuing medical education events to promote unproven off-label indications for drugs.3,4 Many studies that were, ostensibly, designed and proposed by researchers show evidence of so-called ghost authorship by commercial concerns.5

Study bias. Even peer-reviewed, double-blind studies that are published in the medical literature might not sufficiently support off-label prescribing practices because sponsors of such studies can structure them or use statistical analyses to make results look favorable. Former editors of the British Medical Journal and The Lancet have acknowledged that their publications unwittingly served as “an extension of the marketing arm” or “laundering operations” for drug manufacturers.6,7 Even for FDA-approved indications, a selective, positive-result publication bias and nonreporting of negative results may make drugs seem more effective than the full range of studies would justify.8

Legal use of labeling. Although off-label prescribing is accepted medical practice, doctors “may be found negligent if their decision to use a drug off label is sufficiently careless, imprudent, or unprofessional.”9 During a malpractice lawsuit, plaintiff’s counsel could try to use FDA-approved labeling or prescribing information to establish a presumptive standard of care. Such evidence usually is admissible if it is supported by expert testimony. The burden of proof is then placed on the defendant physician to show how an off-label use met the standard of care.10

References

1. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

2. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

3. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.-

4. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

5. Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.-

6. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.-

7. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

8. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

9. Richardson v Miller. 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

10. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

Off-label: Accepted and necessary

Off-label prescribing occurs when a physician prescribes a medication or uses a medical device outside the scope of FDA-approved labeling. Most commonly, off-label use involves prescribing a medication for something other than its FDA-approved indication. An example is sildenafil [Viagra] for women who have antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.1

Other examples are prescribing a drug:

- at an unapproved dose

- in an unapproved format (e.g., mixing capsule contents with applesauce)

- outside the approved age group

- for longer than the approved interval

- at a different dose schedule (e.g., qhs instead of bid or tid).

Typically, it takes years for a new drug to gain FDA approval and additional time for an already-approved drug to gain approval for a new indication. In the meantime, clinicians treat their patients with available drugs prescribed off label.

Off-label prescribing is legal. FDA approval means drugs may be sold and marketed in specific ways. But the FDA does not tell physicians how they can use approved drugs. As each edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference explains, “Once a product has been approved for marketing, a physician may prescribe it for uses or in treatment regimens or patient populations that are not included in approved labeling.”2 Federal statutes state that FDA approval does not “limit or interfere with the authority of a health care practitioner to prescribe” approved drugs or devices “for any condition or disease.”3

- Know why an article applies to your patient. If you are sued for malpractice, you can use an article to support your treatment choice by explaining how this information contributed to your decision-making.

- Tell your patient that the proposed treatment is an off-label use when you obtain consent, even though case law says you don’t have to do this. Telling your patient helps him understand your reasoning and prevents surprises that may give offense.

- Engage in ongoing informed consent. Uncertainty is part of medical practice and is heightened when physicians prescribe off label. Ongoing discussions help patients understand, accept, and share that uncertainty.

- Document informed consent. This will show—if it becomes necessary—that you and your patient made collaborative, conscientious decisions about treatment.1

Reference

1. Royal College of Psychiatrists. CR142. Use of unlicensed medicine for unlicensed applications in psychiatric practice. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/collegereports/cr/cr142.aspx. Accessed March 4, 2009.

Does off-label constitute malpractice?

Off-label use is not only legal—it’s often wise medical practice. Many drug uses that now have FDA approval were off label just a few years ago. Examples include using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat panic disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Fluoxetine is the only FDA-approved drug for treating depression in adolescents, but other SSRIs may also have a favorable risk–benefit profile.6

The practice is common—we know that

Numerous studies have shown that off-label prescribing is common in, for example, psychiatry7 and other specialties.8,9 Because the practice is so common, the mere fact that a drug is not FDA-approved for a particular use does not imply that the drug was prescribed negligently.

Some commentators have suggested that off-label prescribing amounts to human experimentation.10 Without FDA approval, they say, physicians lack hard evidence, so to speak, that a product is safe and effective—making off-label prescribing a small-scale clinical trial based on the doctor’s educated guesses.

If this reasoning is correct, off-label prescribing would require the same human subject protections used in research, including institutional review board approval and special consent forms.

Although this argument sounds plausible, off-label prescribing is not experimentation or research (see “4 reasons why off-label prescribing can be controversial”).4,11-19 Researchers investigate hypotheses to obtain generalizable knowledge, whereas medical therapy aims to benefit individual patients. This experimentation–therapy distinction is not perfect because successful off-label treatment of one patient might imply beneficial effects for others.10 When courts have looked at this matter, though, they have found that “off-label use… by a physician seeking an optimal treatment for his or her patient is not necessarily…research or an investigational or experimental treatment when the use is customarily followed by physicians.”4

Courts also have said that off-label use does not require special informed consent. Just because a drug is prescribed off label doesn’t mean it’s risky. FDA approval “is not a material risk inherently involved in a proposed therapy which a physician should have disclosed to a patient prior to the therapy.”20 In other words, a physician is not required to discuss FDA regulatory status—such as off-label uses of a medication—to comply with standards of informed consent. FDA regulatory status has nothing to do with the risks or benefits of a medication and it does not provide information about treatment alternatives.21

What should you do?

For advice on protecting yourself when you prescribe off label, see the box above.

In addition, you should keep abreast of news and scientific evidence concerning drug uses, effects, interactions, and adverse effects, especially when prescribing for uses that are different from the manufacturer’s intended purposes.22

Last, collect articles on off-label uses, but keep them separate from your patients’ files. Good attorneys are highly skilled at using documents to score legal points, and opposing counsel will prepare questions to focus on the articles’ faults or limitations in isolation.

1. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

2. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62nd ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, Inc.; 2007.

3. Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21USC §396

4. Richardson v Miller. 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

5. Buckman Co. v Plaintiffs’ Legal Comm., 531 US 341 (2001).

6. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

7. Baldwin DS, Kosky N. Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13:414-422.

8. Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. European Network for Drug Investigation in Children. BMJ. 2000;320:79-82.

9. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021-1026.

10. Mehlman MJ. Off-label prescribing. Available at: http://www.thedoctorwillseeyounow.com/articles/bioethics/offlabel_11. Accessed October 21, 2008.

11. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

12. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

13. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.-

14. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

15. Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.-

16. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.-

17. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

18. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

19. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

20. Klein v Biscup. 673 NE2d 225 (Ohio App 1996).

21. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent: debunking myths and misconceptions. Food Drug Law J. 1998;53:71-104.

22. Shajnfeld A, Krueger RB. Reforming (purportedly) non-punitive responses to sexual offending. Dev Mental Health Law. 2006;25:81-99.

1. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

2. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 62nd ed. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, Inc.; 2007.

3. Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21USC §396

4. Richardson v Miller. 44 SW3d 1 (Tenn Ct App 2000).

5. Buckman Co. v Plaintiffs’ Legal Comm., 531 US 341 (2001).

6. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

7. Baldwin DS, Kosky N. Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13:414-422.

8. Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. European Network for Drug Investigation in Children. BMJ. 2000;320:79-82.

9. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021-1026.

10. Mehlman MJ. Off-label prescribing. Available at: http://www.thedoctorwillseeyounow.com/articles/bioethics/offlabel_11. Accessed October 21, 2008.

11. Connolly H, Crary J, McGoon M, et al. Vascular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581-588.

12. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

13. Sismondo S. Ghost management: how much of the medical literature is shaped behind the scenes by the pharmaceutical industry? PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e286.-

14. Steinman MA, Bero L, Chren M, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284-293.

15. Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen H, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e19.-

16. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2(5):e138.-

17. Horton R. The dawn of McScience. New York Rev Books. 2004;51(4):7-9.

18. Turner EH, Matthews A, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252-260.

19. Henry V. Off-label prescribing. Legal implications. J Leg Med. 1999;20:365-383.

20. Klein v Biscup. 673 NE2d 225 (Ohio App 1996).

21. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent: debunking myths and misconceptions. Food Drug Law J. 1998;53:71-104.

22. Shajnfeld A, Krueger RB. Reforming (purportedly) non-punitive responses to sexual offending. Dev Mental Health Law. 2006;25:81-99.

Bonus-Pay Bonanza

Although there is a lot of debate about the effectiveness of pay-for-performance (P4P) plans, I think the plans are only going to increase in the foreseeable future.

We need more research to tell us the relative impact of public reporting of performance data and P4P programs. Most importantly, the details of how these plans are set up, how and what they measure, and the dollar amount involved will have everything to do with whether they are successful in improving the value of care we provide.

SHM’S Practice Management Committee conducted a mini-survey of hospitalist group leaders in 2006. Here are some of the key findings.

P4P Prevalence

Forty-one percent (60 out of 146) of hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders reported their groups have a quality-incentive program. Of those HMG leaders more likely to report participation in a quality-incentive program:

- 60% were at hospitals participating in a P4P program;

- 50% were at multispecialty/PCP medical groups; and

- 50% were in the Southern region.

Of those HMG leaders less likely to report participation in P4P programs, 28% were at academic programs and 31% were at local hospitalist-only groups.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders participating in a quality-incentive program:

- 43% reported it was an individual incentive;

- 35% reported it was a group incentive;

- 10% reported the plan had elements of both individual and group incentives; and

- 12% were not sure if their plans had individual or group incentives.

Basis of Quality Targets

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program (respondents could indicate one or more answers):

- 60% of the programs have targets based on national benchmarks;

- 23% have targets based on local or regional benchmarks;

- 37% have targets based on their hospital’s previous experience; and

- 47% have targets based on improvement over a baseline.

Maximum Impact of Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 16% report the maximum impact is less than 3%;

- 24% report the maximum impact is from 3% to 7%;

- 35% report the maximum impact is from 8% to 10%;

- 17% report the maximum impact is from 11% to 20%;

- 3% report the maximum impact is more than 20%; and

- 5% report they do not know the maximum impact.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 61% said they have received an incentive payment;

- 37% have not received an incentive payment; and

- 2% were unsure if they have received an incentive payment.

Quality Metrics

The most common metrics used in P4P programs, based on 29 responses to the SHM survey:

- 93% of HM programs have metrics based on The Joint Commission’s (JCAHO) heart failure measures;

- 86% have metrics based on JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 79% have metrics based on JCAHO myocardial infarction measures;

- 28% have metrics based on a measure of medication reconciliation;

- 24% have metrics based on avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% have metrics based on 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 21% have metrics based on patient satisfaction measures;

- 17% have metrics based on transitions-of-care measures;

- 10% have metrics based on throughput measures;

- 7% have metrics based on end-of-life measures;

- 7% have metrics based on “good citizenship” measures;

- 7% have metrics based on mortality rate measures; and

- 7% have metrics based on readmission rate measures.

The most common metrics used in quality-incentive programs, based on 45 responses to SHM’s survey:

- 73% of programs use JCAHO heart failure measures;

- 73% use “good citizenship” measures;

- 73% use patient satisfaction measures;

- 67% use JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 51% use transitions-of-care measures;

- 44% use JCAHO M.I. measures;

- 31% use throughput measures;

- 27% use avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% use a measure based on medication reconciliation;

- 11% use 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 9% use readmission rate measures;

- 7% use mortality rate measures; and

- 2% use end-of-life measures.

Recommendations

The prevalence of hospitalist quality-based compensation plans is continuing to grow rapidly, but the details of the plans’ structure will govern whether they benefit our patients, improve the overall value of the care we provide, and serve as a meaningful component of our compensation. I suggest each practice consider implementing plans with the following attributes:

A total dollar amount available for performance that is enough to influence hospitalist behavior. I think quality incentives should compose as much as 15% to 20% of a hospitalist’s annual income. Plans connecting quality performance to equal to or less than 7% of annual compensation (the case for 40% of groups in the above survey) rarely are effective.

Money vs. metrics. It usually is better to establish a plan based on a sliding scale of improved performance rather than a single threshold. For example, if all of the bonus money is available for a 10% improvement in performance, consider providing 10% of the total available money for each 1% improvement in performance.

Degree of difficulty. Performance thresholds should be set so that hospitalists need to change their practices to achieve them, but not so far out of reach that hospitalists give up on them. This can get tricky. Many practices set thresholds that are very easy to reach (e.g., they may be near the current level of performance).

Metrics for which trusted data is readily available. In most cases, this means using data already being collected. Avoid hard-to-track metrics, as they are likely to lead to disagreements about their accuracy.

Group vs. individual measures. Most performance metrics can’t be clearly attributed to one hospitalist as compared to another. For example, who gets the credit or blame for Ms. Smith getting or not getting a pneumovax? The majority of performance metrics are best measured and paid on a group basis. Some metrics, such as documenting medicine reconciliation on admission and discharge, can be effectively attributed to a single hospitalist and could be paid on an individual basis.

Small number of metrics, A meaningfully large amount of money should be connected to each one. Don’t make the mistake of having a $10,000 per doctor annual quality bonus pool divided among 20 metrics (each metric would pay a maximum of $500 per year).

Rotating metrics. Consider an annual meeting with members of your hospital’s administration to jointly establish the metrics used in the hospitalist quality incentive for that year. It is reasonable to change the metrics periodically.

It seems to me P4P programs are in their infancy, and will continue to evolve rapidly. Plans that fail to improve outcomes enough to justify the complexity of implementing, tracking, and paying for them will disappear slowly. (I wonder if payment for pneumovax administration during the hospital stay will be in this category.) And new, more effective, and more valuable programs will be developed.

Hospitalist practices will need to be nimble to keep pace with all of this change. Although SHM can alert you to how new P4P initiatives might affect your practice, and even recommend methods to improve your performance, you and your hospitalist colleagues still will have a lot of work to operationalize these programs in your practice. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Although there is a lot of debate about the effectiveness of pay-for-performance (P4P) plans, I think the plans are only going to increase in the foreseeable future.

We need more research to tell us the relative impact of public reporting of performance data and P4P programs. Most importantly, the details of how these plans are set up, how and what they measure, and the dollar amount involved will have everything to do with whether they are successful in improving the value of care we provide.

SHM’S Practice Management Committee conducted a mini-survey of hospitalist group leaders in 2006. Here are some of the key findings.

P4P Prevalence

Forty-one percent (60 out of 146) of hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders reported their groups have a quality-incentive program. Of those HMG leaders more likely to report participation in a quality-incentive program:

- 60% were at hospitals participating in a P4P program;

- 50% were at multispecialty/PCP medical groups; and

- 50% were in the Southern region.

Of those HMG leaders less likely to report participation in P4P programs, 28% were at academic programs and 31% were at local hospitalist-only groups.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders participating in a quality-incentive program:

- 43% reported it was an individual incentive;

- 35% reported it was a group incentive;

- 10% reported the plan had elements of both individual and group incentives; and

- 12% were not sure if their plans had individual or group incentives.

Basis of Quality Targets

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program (respondents could indicate one or more answers):

- 60% of the programs have targets based on national benchmarks;

- 23% have targets based on local or regional benchmarks;

- 37% have targets based on their hospital’s previous experience; and

- 47% have targets based on improvement over a baseline.

Maximum Impact of Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 16% report the maximum impact is less than 3%;

- 24% report the maximum impact is from 3% to 7%;

- 35% report the maximum impact is from 8% to 10%;

- 17% report the maximum impact is from 11% to 20%;

- 3% report the maximum impact is more than 20%; and

- 5% report they do not know the maximum impact.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 61% said they have received an incentive payment;

- 37% have not received an incentive payment; and

- 2% were unsure if they have received an incentive payment.

Quality Metrics