User login

Multiply Your Contacts

Networking is crucial to career advancement, no matter what your long-term goals are. Connecting with others in hospital medicine, general healthcare, and business can build your knowledge base, your support system, and your reputation. But how—and why—should hospitalists present themselves to the influential people they need to know?

The Need to Network

You may think it’s not necessary to expand your list of contacts within hospital medicine. Put another way, why bother to network? Vineet Arora, MD, MA, assistant professor of medicine at the Pritzker School of Medicine at University of Chicago, points to a paper, “Strength of Weak Ties,” published in the May 1973 American Journal of Sociology by sociologist Mark Granovetter. In the paper, he presents a social science theory that says “the people who are most helpful to you are those who you don’t know well,” Dr. Arora says. Granovetter’s theory suggests that in marketing or politics, the weak ties enable individuals to reach populations and audiences that are not accessible via strong ties.

“It’s not your friends or the people you know the best who are most likely to help you get a job,” Dr. Arora says. “Those people have already helped you as much as they can.” The main lesson here, she says, is to “think carefully about reaching outside your comfort zone. Introduce yourself to a stranger; it’s to your advantage to cultivate these weak ties.”

To increase your number of “weak ties” in hospital medicine, follow these simple steps:

Step 1: Establish Goals

Consider why you’re networking in order to focus your efforts and target your contacts. Are you looking for a new position? Do you want to transform yourself into the go-to hospitalist in a specific clinical area? Are you looking to learn leadership skills?

Once you’ve determined what you want to get out of networking—and it might be more than one goal—outline a brief elevator speech. It’s a one-minute explanation of who you are and what you’re interested in. It will prepare you to open a conversation with a stranger. “You should present yourself in a concise way,” Dr. Arora stresses. “State who you are and what your interests are.”

Step 2: Make a Plan

Once you know your goals and are able to state them clearly and eloquently, map out your networking strategy. You may simply keep this in the back of your mind for the short term, or you may specifically plan on attending events that will allow you to network with the appropriate people, such as hiring managers, experts in your area of interest, or HM movers and shakers.

“Figure out who the people are in your field of interest who are making waves, and go where they are,” Dr. Arora says. But “don’t just attend the meetings. Be proactive.”

Choose your conferences wisely. For example, if you’re interested in leadership skills or a leadership position, consider SHM’s biannual Leadership Academy. “Not only is this a terrific learning opportunity, it’s a very strong networking environment,” says Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer for Cogent Healthcare in Nashville, Tenn., and past president of SHM. “You’re sharing a room with 120 or 130 leaders or leaders-in-training.”

Dozens of annual conferences and courses are available for networking, including clinical CME courses offered by universities. “The American College of Physician Executives [ACPE] has advanced training courses not only in management, but in quality improvement and a variety of other interests,” Dr. Holman explains.

Networking at industry events may not have an immediate payoff, Dr. Arora warns. “You’re probably not going to land a job or land an opportunity at a meeting,” she says, “but you float your name and get to know people.”

Step 3: Let the Networking Begin

With your short speech ready to go, attend a conference or meeting with key industry leaders and simply approach influential individuals you’d like to meet.

“The way it’s done is even more important than where and when you do it,” Dr. Holman says. “You don’t want to come across as pushy, aggressive, or needy.” Simply introduce yourself with a handshake, rely on your elevator speech for a brief explanation, then give that person a chance to talk. Ask questions about how their career advanced, then ask if they know of any opportunities for you, he says.

If your initial conversation is rushed—say, you’re approaching a speaker after a presentation—keep your conversation brief. “At an event like an SHM meeting, it may be difficult to catch certain people,” Dr. Holman says. “If you can, at least shake their hand and exchange business cards, then follow up with an e-mail and ask for 15 minutes of their time. This is very acceptable; it happens to me all the time.”

Another key piece of advice: “Don’t ask them to contact you—you be the one to send an e-mail,” Dr. Holman says.

Step 4: Follow Up

Soon after the in-person meeting, send a follow-up e-mail. Carefully consider your subject line to ensure your message is read. Reference your encounter in the message (e.g., “We met after your presentation at the conference in Miami”) to remind the person who you are. Depending on your goals, you may ask for information to be forwarded, contacts for additional networking, or request a brief telephone conversation.

“A lot of speakers post their e-mail in their presentation,” Dr. Arora points out. “If you don’t get a chance to talk to them in person, send them a message after you get home. People love to get feedback. Comment on their presentation and introduce yourself that way.”

Hospitalists can strengthen their connections with an offer to reciprocate: “You want to be as helpful as you are helped,” Dr. Holman says. “End the conversation with the offer: ‘If there is any way that I can help you, let me know.’ ”

Set goals, practice your elevator speech, venture out and introduce yourself, and follow up.

These simple steps will help you in your networking efforts, and likely will help advance your career. TH

Jane Jerrard is a medical writer based in Chicago. She also writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Networking is crucial to career advancement, no matter what your long-term goals are. Connecting with others in hospital medicine, general healthcare, and business can build your knowledge base, your support system, and your reputation. But how—and why—should hospitalists present themselves to the influential people they need to know?

The Need to Network

You may think it’s not necessary to expand your list of contacts within hospital medicine. Put another way, why bother to network? Vineet Arora, MD, MA, assistant professor of medicine at the Pritzker School of Medicine at University of Chicago, points to a paper, “Strength of Weak Ties,” published in the May 1973 American Journal of Sociology by sociologist Mark Granovetter. In the paper, he presents a social science theory that says “the people who are most helpful to you are those who you don’t know well,” Dr. Arora says. Granovetter’s theory suggests that in marketing or politics, the weak ties enable individuals to reach populations and audiences that are not accessible via strong ties.

“It’s not your friends or the people you know the best who are most likely to help you get a job,” Dr. Arora says. “Those people have already helped you as much as they can.” The main lesson here, she says, is to “think carefully about reaching outside your comfort zone. Introduce yourself to a stranger; it’s to your advantage to cultivate these weak ties.”

To increase your number of “weak ties” in hospital medicine, follow these simple steps:

Step 1: Establish Goals

Consider why you’re networking in order to focus your efforts and target your contacts. Are you looking for a new position? Do you want to transform yourself into the go-to hospitalist in a specific clinical area? Are you looking to learn leadership skills?

Once you’ve determined what you want to get out of networking—and it might be more than one goal—outline a brief elevator speech. It’s a one-minute explanation of who you are and what you’re interested in. It will prepare you to open a conversation with a stranger. “You should present yourself in a concise way,” Dr. Arora stresses. “State who you are and what your interests are.”

Step 2: Make a Plan

Once you know your goals and are able to state them clearly and eloquently, map out your networking strategy. You may simply keep this in the back of your mind for the short term, or you may specifically plan on attending events that will allow you to network with the appropriate people, such as hiring managers, experts in your area of interest, or HM movers and shakers.

“Figure out who the people are in your field of interest who are making waves, and go where they are,” Dr. Arora says. But “don’t just attend the meetings. Be proactive.”

Choose your conferences wisely. For example, if you’re interested in leadership skills or a leadership position, consider SHM’s biannual Leadership Academy. “Not only is this a terrific learning opportunity, it’s a very strong networking environment,” says Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer for Cogent Healthcare in Nashville, Tenn., and past president of SHM. “You’re sharing a room with 120 or 130 leaders or leaders-in-training.”

Dozens of annual conferences and courses are available for networking, including clinical CME courses offered by universities. “The American College of Physician Executives [ACPE] has advanced training courses not only in management, but in quality improvement and a variety of other interests,” Dr. Holman explains.

Networking at industry events may not have an immediate payoff, Dr. Arora warns. “You’re probably not going to land a job or land an opportunity at a meeting,” she says, “but you float your name and get to know people.”

Step 3: Let the Networking Begin

With your short speech ready to go, attend a conference or meeting with key industry leaders and simply approach influential individuals you’d like to meet.

“The way it’s done is even more important than where and when you do it,” Dr. Holman says. “You don’t want to come across as pushy, aggressive, or needy.” Simply introduce yourself with a handshake, rely on your elevator speech for a brief explanation, then give that person a chance to talk. Ask questions about how their career advanced, then ask if they know of any opportunities for you, he says.

If your initial conversation is rushed—say, you’re approaching a speaker after a presentation—keep your conversation brief. “At an event like an SHM meeting, it may be difficult to catch certain people,” Dr. Holman says. “If you can, at least shake their hand and exchange business cards, then follow up with an e-mail and ask for 15 minutes of their time. This is very acceptable; it happens to me all the time.”

Another key piece of advice: “Don’t ask them to contact you—you be the one to send an e-mail,” Dr. Holman says.

Step 4: Follow Up

Soon after the in-person meeting, send a follow-up e-mail. Carefully consider your subject line to ensure your message is read. Reference your encounter in the message (e.g., “We met after your presentation at the conference in Miami”) to remind the person who you are. Depending on your goals, you may ask for information to be forwarded, contacts for additional networking, or request a brief telephone conversation.

“A lot of speakers post their e-mail in their presentation,” Dr. Arora points out. “If you don’t get a chance to talk to them in person, send them a message after you get home. People love to get feedback. Comment on their presentation and introduce yourself that way.”

Hospitalists can strengthen their connections with an offer to reciprocate: “You want to be as helpful as you are helped,” Dr. Holman says. “End the conversation with the offer: ‘If there is any way that I can help you, let me know.’ ”

Set goals, practice your elevator speech, venture out and introduce yourself, and follow up.

These simple steps will help you in your networking efforts, and likely will help advance your career. TH

Jane Jerrard is a medical writer based in Chicago. She also writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Networking is crucial to career advancement, no matter what your long-term goals are. Connecting with others in hospital medicine, general healthcare, and business can build your knowledge base, your support system, and your reputation. But how—and why—should hospitalists present themselves to the influential people they need to know?

The Need to Network

You may think it’s not necessary to expand your list of contacts within hospital medicine. Put another way, why bother to network? Vineet Arora, MD, MA, assistant professor of medicine at the Pritzker School of Medicine at University of Chicago, points to a paper, “Strength of Weak Ties,” published in the May 1973 American Journal of Sociology by sociologist Mark Granovetter. In the paper, he presents a social science theory that says “the people who are most helpful to you are those who you don’t know well,” Dr. Arora says. Granovetter’s theory suggests that in marketing or politics, the weak ties enable individuals to reach populations and audiences that are not accessible via strong ties.

“It’s not your friends or the people you know the best who are most likely to help you get a job,” Dr. Arora says. “Those people have already helped you as much as they can.” The main lesson here, she says, is to “think carefully about reaching outside your comfort zone. Introduce yourself to a stranger; it’s to your advantage to cultivate these weak ties.”

To increase your number of “weak ties” in hospital medicine, follow these simple steps:

Step 1: Establish Goals

Consider why you’re networking in order to focus your efforts and target your contacts. Are you looking for a new position? Do you want to transform yourself into the go-to hospitalist in a specific clinical area? Are you looking to learn leadership skills?

Once you’ve determined what you want to get out of networking—and it might be more than one goal—outline a brief elevator speech. It’s a one-minute explanation of who you are and what you’re interested in. It will prepare you to open a conversation with a stranger. “You should present yourself in a concise way,” Dr. Arora stresses. “State who you are and what your interests are.”

Step 2: Make a Plan

Once you know your goals and are able to state them clearly and eloquently, map out your networking strategy. You may simply keep this in the back of your mind for the short term, or you may specifically plan on attending events that will allow you to network with the appropriate people, such as hiring managers, experts in your area of interest, or HM movers and shakers.

“Figure out who the people are in your field of interest who are making waves, and go where they are,” Dr. Arora says. But “don’t just attend the meetings. Be proactive.”

Choose your conferences wisely. For example, if you’re interested in leadership skills or a leadership position, consider SHM’s biannual Leadership Academy. “Not only is this a terrific learning opportunity, it’s a very strong networking environment,” says Russell L. Holman, MD, chief operating officer for Cogent Healthcare in Nashville, Tenn., and past president of SHM. “You’re sharing a room with 120 or 130 leaders or leaders-in-training.”

Dozens of annual conferences and courses are available for networking, including clinical CME courses offered by universities. “The American College of Physician Executives [ACPE] has advanced training courses not only in management, but in quality improvement and a variety of other interests,” Dr. Holman explains.

Networking at industry events may not have an immediate payoff, Dr. Arora warns. “You’re probably not going to land a job or land an opportunity at a meeting,” she says, “but you float your name and get to know people.”

Step 3: Let the Networking Begin

With your short speech ready to go, attend a conference or meeting with key industry leaders and simply approach influential individuals you’d like to meet.

“The way it’s done is even more important than where and when you do it,” Dr. Holman says. “You don’t want to come across as pushy, aggressive, or needy.” Simply introduce yourself with a handshake, rely on your elevator speech for a brief explanation, then give that person a chance to talk. Ask questions about how their career advanced, then ask if they know of any opportunities for you, he says.

If your initial conversation is rushed—say, you’re approaching a speaker after a presentation—keep your conversation brief. “At an event like an SHM meeting, it may be difficult to catch certain people,” Dr. Holman says. “If you can, at least shake their hand and exchange business cards, then follow up with an e-mail and ask for 15 minutes of their time. This is very acceptable; it happens to me all the time.”

Another key piece of advice: “Don’t ask them to contact you—you be the one to send an e-mail,” Dr. Holman says.

Step 4: Follow Up

Soon after the in-person meeting, send a follow-up e-mail. Carefully consider your subject line to ensure your message is read. Reference your encounter in the message (e.g., “We met after your presentation at the conference in Miami”) to remind the person who you are. Depending on your goals, you may ask for information to be forwarded, contacts for additional networking, or request a brief telephone conversation.

“A lot of speakers post their e-mail in their presentation,” Dr. Arora points out. “If you don’t get a chance to talk to them in person, send them a message after you get home. People love to get feedback. Comment on their presentation and introduce yourself that way.”

Hospitalists can strengthen their connections with an offer to reciprocate: “You want to be as helpful as you are helped,” Dr. Holman says. “End the conversation with the offer: ‘If there is any way that I can help you, let me know.’ ”

Set goals, practice your elevator speech, venture out and introduce yourself, and follow up.

These simple steps will help you in your networking efforts, and likely will help advance your career. TH

Jane Jerrard is a medical writer based in Chicago. She also writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

To Crush or Not to Crush

There are multiple reasons for crushing tablets or capsule contents before administering medications, but there are numerous medications that should not be crushed. These medications should not be chewed, either, usually due to their specific formulations and their pharmacokinetic properties.1 Most of the no-crush medications are sustained-release, oral-dosage formulas. The majority of extended-release products should not be crushed or chewed, although there are some newer slow-release tablet formulations available that are scored and can be divided or halved (e.g., Toprol XL).

A common reason for crushing a tablet or capsule is for use by a hospitalized patient with an enteral feeding tube. A recent review in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy provides more details about administering medications in patients with enteral feeding tubes.2 Oral solutions can be used when commercially available and medically appropriate. If an oral solution or suspension is not available, the hospital pharmacy should be consulted to determine if a liquid formulation of the product can be extemporaneously prepared. In some cases, after careful consideration of compatibility, stability, and drug absorption changes, an injectable formulation of a product may be used. You should always consult your hospital pharmacist for information on this modality of drug administration.

Some patients have difficulty swallowing tablets or capsules; some dislike the taste. In these cases, crushing of medication for powdered delivery (to be mixed with food or beverages) should be considered. But beware of certain caveats, as not all medications are suitable for crushing. Generally, meds that should not be crushed fall into one of these categories:

- Sustained-release tablets, which can be composed of multiple layers for different drug release times, as can beads within capsules. Some of the more common prefixes or suffixes for sustained-release, controlled-release, or controlled-delivery products include: 12-hour, 24-hour, CC, CD, CR, ER, LA, Retard, SA, Slo-, SR, XL, XR, or XT.

- Enteric-coated tablets, which are formulated because certain drugs can be irritating to the stomach or are degraded by stomach acid. By enteric-coating tablets or capsule beads, the drug’s release can be delayed until it reaches the small intestine. Prefixes include EN- and EC-.

Other medications have objectionable tastes and are sugar-coated to improve tolerability. If this type of medication is crushed, the patient would be subject to its unpleasant taste, which could significantly impair medication adherence. Additionally, both sublingual and effervescent medications should not be crushed because it will decrease the medication’s effectiveness.

Hospital Pharmacy publishes a wall chart that includes many of these types of formulations, along with their do’s and don’ts. If there is ever any doubt about the best way to administer a particular product or whether it can be halved or crushed, ask your pharmacist.3 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

1. Mitchell J. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed or chewed: facts and comparisons 4.0. Hospital Pharmacy Web site. Available at: online.factsandcomparisons.com/Viewer.aspx?book=atoz&monoID=fandc-atoz1040. Accessed March 5, 2009.

2. Williams NT. Medication administration through enteral feeding tubes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(24):2347-2357.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed: wall chart. Wolters Kluwer Health Web site. Available at: www.factsandcomparisons.com/Products/product.aspx?id=1111. Accessed Jan. 26, 2009.

4. Mylan's Matrix receives final FDA approval for the generic version of the antiretroviral Zerit capsules. Wolters Kluwer Health Web site. Available at: http://mylan.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=399. Accessed Jan. 23, 2009.

5. Product approval information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/Cber/products/Cinryze.htm. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

6. FDA licenses for marketing new therapy for rare genetic disease. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01903.html. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

7. Sancuso patch approved for nausea and vomiting. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.empr.com/Sancusopatchapprovedfornauseaandvomiting/article/122384/. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

8. TussiCaps now available for cough suppression. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.empr.com/TussiCapsnowavailableforcoughsuppression/article/122377/. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

9. UCB’s Vimpat approved by U.S. FDA as adjunctive therapy for partial onset seizures in adults. Medical News Today Web site. Available at: www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/127354.php. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

10. Apriso granted FDA marketing approval for maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Medical News Today Web site. Available at: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/127839.php. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

11. http://biz.yahoo.com/ap/081106/cv_therapeutics _ranexa.html?.v=1. Accessed February 2, 2009.

12. FDA approves Seroquel for bipolar maintenance. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.prescribingreference.com/news/showNews/which/SeroquelXRForBipolar10101. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

13. Seroquel XR Web site. Available at: www.pharmacistelink.com/news/2009/01/14_seroquel.pdf. Accessed Jan. 23, 2009.

14. Peck P. Smoking cessation drug linked to 1,001 new serious adverse events. Medpage Today Web site. Available at: www.medpagetoday.com/PrimaryCare/Smoking/11428. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

15. Public health advisory: important information on Chantix (varenicline). U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/CDER/Drug/advisory/varenicline.htm. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

There are multiple reasons for crushing tablets or capsule contents before administering medications, but there are numerous medications that should not be crushed. These medications should not be chewed, either, usually due to their specific formulations and their pharmacokinetic properties.1 Most of the no-crush medications are sustained-release, oral-dosage formulas. The majority of extended-release products should not be crushed or chewed, although there are some newer slow-release tablet formulations available that are scored and can be divided or halved (e.g., Toprol XL).

A common reason for crushing a tablet or capsule is for use by a hospitalized patient with an enteral feeding tube. A recent review in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy provides more details about administering medications in patients with enteral feeding tubes.2 Oral solutions can be used when commercially available and medically appropriate. If an oral solution or suspension is not available, the hospital pharmacy should be consulted to determine if a liquid formulation of the product can be extemporaneously prepared. In some cases, after careful consideration of compatibility, stability, and drug absorption changes, an injectable formulation of a product may be used. You should always consult your hospital pharmacist for information on this modality of drug administration.

Some patients have difficulty swallowing tablets or capsules; some dislike the taste. In these cases, crushing of medication for powdered delivery (to be mixed with food or beverages) should be considered. But beware of certain caveats, as not all medications are suitable for crushing. Generally, meds that should not be crushed fall into one of these categories:

- Sustained-release tablets, which can be composed of multiple layers for different drug release times, as can beads within capsules. Some of the more common prefixes or suffixes for sustained-release, controlled-release, or controlled-delivery products include: 12-hour, 24-hour, CC, CD, CR, ER, LA, Retard, SA, Slo-, SR, XL, XR, or XT.

- Enteric-coated tablets, which are formulated because certain drugs can be irritating to the stomach or are degraded by stomach acid. By enteric-coating tablets or capsule beads, the drug’s release can be delayed until it reaches the small intestine. Prefixes include EN- and EC-.

Other medications have objectionable tastes and are sugar-coated to improve tolerability. If this type of medication is crushed, the patient would be subject to its unpleasant taste, which could significantly impair medication adherence. Additionally, both sublingual and effervescent medications should not be crushed because it will decrease the medication’s effectiveness.

Hospital Pharmacy publishes a wall chart that includes many of these types of formulations, along with their do’s and don’ts. If there is ever any doubt about the best way to administer a particular product or whether it can be halved or crushed, ask your pharmacist.3 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

1. Mitchell J. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed or chewed: facts and comparisons 4.0. Hospital Pharmacy Web site. Available at: online.factsandcomparisons.com/Viewer.aspx?book=atoz&monoID=fandc-atoz1040. Accessed March 5, 2009.

2. Williams NT. Medication administration through enteral feeding tubes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(24):2347-2357.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed: wall chart. Wolters Kluwer Health Web site. Available at: www.factsandcomparisons.com/Products/product.aspx?id=1111. Accessed Jan. 26, 2009.

4. Mylan's Matrix receives final FDA approval for the generic version of the antiretroviral Zerit capsules. Wolters Kluwer Health Web site. Available at: http://mylan.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=399. Accessed Jan. 23, 2009.

5. Product approval information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/Cber/products/Cinryze.htm. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

6. FDA licenses for marketing new therapy for rare genetic disease. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01903.html. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

7. Sancuso patch approved for nausea and vomiting. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.empr.com/Sancusopatchapprovedfornauseaandvomiting/article/122384/. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

8. TussiCaps now available for cough suppression. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.empr.com/TussiCapsnowavailableforcoughsuppression/article/122377/. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

9. UCB’s Vimpat approved by U.S. FDA as adjunctive therapy for partial onset seizures in adults. Medical News Today Web site. Available at: www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/127354.php. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

10. Apriso granted FDA marketing approval for maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Medical News Today Web site. Available at: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/127839.php. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

11. http://biz.yahoo.com/ap/081106/cv_therapeutics _ranexa.html?.v=1. Accessed February 2, 2009.

12. FDA approves Seroquel for bipolar maintenance. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.prescribingreference.com/news/showNews/which/SeroquelXRForBipolar10101. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

13. Seroquel XR Web site. Available at: www.pharmacistelink.com/news/2009/01/14_seroquel.pdf. Accessed Jan. 23, 2009.

14. Peck P. Smoking cessation drug linked to 1,001 new serious adverse events. Medpage Today Web site. Available at: www.medpagetoday.com/PrimaryCare/Smoking/11428. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

15. Public health advisory: important information on Chantix (varenicline). U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/CDER/Drug/advisory/varenicline.htm. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

There are multiple reasons for crushing tablets or capsule contents before administering medications, but there are numerous medications that should not be crushed. These medications should not be chewed, either, usually due to their specific formulations and their pharmacokinetic properties.1 Most of the no-crush medications are sustained-release, oral-dosage formulas. The majority of extended-release products should not be crushed or chewed, although there are some newer slow-release tablet formulations available that are scored and can be divided or halved (e.g., Toprol XL).

A common reason for crushing a tablet or capsule is for use by a hospitalized patient with an enteral feeding tube. A recent review in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy provides more details about administering medications in patients with enteral feeding tubes.2 Oral solutions can be used when commercially available and medically appropriate. If an oral solution or suspension is not available, the hospital pharmacy should be consulted to determine if a liquid formulation of the product can be extemporaneously prepared. In some cases, after careful consideration of compatibility, stability, and drug absorption changes, an injectable formulation of a product may be used. You should always consult your hospital pharmacist for information on this modality of drug administration.

Some patients have difficulty swallowing tablets or capsules; some dislike the taste. In these cases, crushing of medication for powdered delivery (to be mixed with food or beverages) should be considered. But beware of certain caveats, as not all medications are suitable for crushing. Generally, meds that should not be crushed fall into one of these categories:

- Sustained-release tablets, which can be composed of multiple layers for different drug release times, as can beads within capsules. Some of the more common prefixes or suffixes for sustained-release, controlled-release, or controlled-delivery products include: 12-hour, 24-hour, CC, CD, CR, ER, LA, Retard, SA, Slo-, SR, XL, XR, or XT.

- Enteric-coated tablets, which are formulated because certain drugs can be irritating to the stomach or are degraded by stomach acid. By enteric-coating tablets or capsule beads, the drug’s release can be delayed until it reaches the small intestine. Prefixes include EN- and EC-.

Other medications have objectionable tastes and are sugar-coated to improve tolerability. If this type of medication is crushed, the patient would be subject to its unpleasant taste, which could significantly impair medication adherence. Additionally, both sublingual and effervescent medications should not be crushed because it will decrease the medication’s effectiveness.

Hospital Pharmacy publishes a wall chart that includes many of these types of formulations, along with their do’s and don’ts. If there is ever any doubt about the best way to administer a particular product or whether it can be halved or crushed, ask your pharmacist.3 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

1. Mitchell J. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed or chewed: facts and comparisons 4.0. Hospital Pharmacy Web site. Available at: online.factsandcomparisons.com/Viewer.aspx?book=atoz&monoID=fandc-atoz1040. Accessed March 5, 2009.

2. Williams NT. Medication administration through enteral feeding tubes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(24):2347-2357.

3. Mitchell JF. Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed: wall chart. Wolters Kluwer Health Web site. Available at: www.factsandcomparisons.com/Products/product.aspx?id=1111. Accessed Jan. 26, 2009.

4. Mylan's Matrix receives final FDA approval for the generic version of the antiretroviral Zerit capsules. Wolters Kluwer Health Web site. Available at: http://mylan.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=399. Accessed Jan. 23, 2009.

5. Product approval information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/Cber/products/Cinryze.htm. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

6. FDA licenses for marketing new therapy for rare genetic disease. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01903.html. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

7. Sancuso patch approved for nausea and vomiting. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.empr.com/Sancusopatchapprovedfornauseaandvomiting/article/122384/. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

8. TussiCaps now available for cough suppression. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.empr.com/TussiCapsnowavailableforcoughsuppression/article/122377/. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

9. UCB’s Vimpat approved by U.S. FDA as adjunctive therapy for partial onset seizures in adults. Medical News Today Web site. Available at: www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/127354.php. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

10. Apriso granted FDA marketing approval for maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Medical News Today Web site. Available at: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/127839.php. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

11. http://biz.yahoo.com/ap/081106/cv_therapeutics _ranexa.html?.v=1. Accessed February 2, 2009.

12. FDA approves Seroquel for bipolar maintenance. Monthly Prescribing Reference Web site. Available at: www.prescribingreference.com/news/showNews/which/SeroquelXRForBipolar10101. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

13. Seroquel XR Web site. Available at: www.pharmacistelink.com/news/2009/01/14_seroquel.pdf. Accessed Jan. 23, 2009.

14. Peck P. Smoking cessation drug linked to 1,001 new serious adverse events. Medpage Today Web site. Available at: www.medpagetoday.com/PrimaryCare/Smoking/11428. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

15. Public health advisory: important information on Chantix (varenicline). U.S. Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: www.fda.gov/CDER/Drug/advisory/varenicline.htm. Accessed Jan. 14, 2009.

Eliminate Inconsistency

Three years ago, Andrew Masica, MD, MSCI, joined the MedProvider Inpatient Care Unit hospitalist group at Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) in Dallas just as the national debate on Medicare recidivism rates was focusing on high-risk populations.

Dr. Masica’s master’s degree in clinical investigation, combined with the roughly 35 hospitalists operating at the 900-bed BUMC, suggested it made sense to see what Baylor’s doctors could add to the conversation. And a study was born: “Reduction of 30-Day Post-Discharge Hospital Readmission or ED Visit Rates in High-Risk Elderly Medical Patients Through Delivery of a Targeted Care Bundle.” The single-center study will be published in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine.

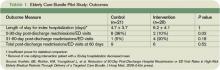

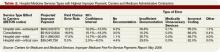

The study found readmission/ED visit rates were lower after 30 days for those given an individualized care bundle of educational information compared with those who received the center’s standard treatment (10% individualized care bundle compared with 38.1% for standard treatment, P=0.04). Analysis also showed that for those patients who had a readmission or post-discharge ED visit, the time interval to the second event was longer in the intervention group compared with the control group (36.2 days to 15.7 days, P=0.05). At 60 days, however, readmission/ED visit rates were not affected positively for the intervention group versus the control group (42.9% vs. 30%, P=0.52).

The study team emphasizes that its small sample size—20 in the intervention group, 21 in the control—make it nearly impossible to extrapolate the results to large population sets; however, the results fuel the debate. “We don’t want to overstate our conclusions,” says Dr. Masica, the principal study investigator. “Important questions need to be asked. Is it the specific characteristics of the care coordinators? Can you reproduce this at other facilities? Is it the care bundle or the personnel? …We view this as early-phase work that people can build upon.”

Expansion Opportunity

Still, Dr. Masica believes hospitalist-centric conclusions can be reached. Since the study used in-house personnel only, other HM groups could easily reproduce the bundle without added expense. Additionally, because the coordinated-care approach involves a checklist of patient interaction activities, not medical procedures, the barrier to replication is further reduced. However, hospitalists will need the cooperation of more than their own medical directors.

In BUMC’s case, that meant the assistance of patient-care support services and the pharmacy department. Liz Youngblood, RN, MBA, supervised the care coordination in her role as vice president of patient-care support services for the Baylor Health Care System. Brian Cohen, PharmD, MS, was the pharmacy lead. Dr. Masica notes the confluence between departments was one of the keys to the reduction in recidivism over the first 30 days post-discharge.

“If you pick the high-risk patients and deliver the care in a bundle, you would be able to improve outcomes,” Dr. Masica says. “When you deliver just pieces of the care—just the coordinated care or just the pharmacist—you get inconsistencies.”

The first struggle BUMC researchers encountered—once they secured funding from Baylor’s Institute for Health Care Research and Improvement—was enrolling enough patients who met the criteria set for the study. The high-risk patient thresholds were:

- At least 70 years old;

- Regular use of at least five medications;

- At least three chronic, comorbid conditions;

- Assistance with at least one activity of daily living; and

- Preadmission residence at home or at an assisted-living facility with a reasonable expectation of disposition back to that residence.

Researchers also wanted patients with common DRGs admitted, and set exclusion criteria as well: lack of fluency in English; admission primarily for a surgical procedure; terminal diagnosis with life expectancy of less than six months; and residency in a long-term care facility. Patients who could not be enrolled within 72 hours of admission were excluded.

Dr. Masica notes hospitalists interested in replicating the research should pay attention to the consent forms they used. When the Baylor team conducted its research from March to September 2007, they used a long-form consent waiver. Baylor’s consent form for similar studies has since been shortened, and Dr. Masica says a less complicated form would have helped encourage more patients to enroll. In the end, 60 patients declined to enroll in the Baylor study and 56 were unable to give their consent due to impairment.

Once enrolled, the patients were delivered the care bundle in stages (see Table 1). Care coordinators (CCs) saw patients daily, instructing them on specific health conditions with an eye toward teaching home care, should post-discharge problems arise. Clinical pharmacists (CPs) visited patients to focus on medication reconciliation and education. CCs and CPs would follow up with post-discharge phone calls to confirm receipt of medical equipment and medications, use and affects of those medications, home-health arrangements, and to schedule follow-up appointments. If patients indicated any issues, the coordinators recommended action plans.

“It would be surprising to find out how little patients really understand about why they’re in the hospital and what they’re being treated for,” Youngblood says. “To have the reinforcement is really valuable.”

Care Continuum

One topic the study skirts is the ever-contentious realm of post-discharge care and who takes over responsibility for patient care. While the Baylor study examined readmission/ED visit rates through 60 days, Dr. Masica says a transitional-care program is the best way to manage that care continuum.

“We did see a difference at 30 days,” Dr. Masica says. “At 60 days, that effectively washed out. That makes sense. You can only control things so much from the hospital side. After 30 days, you need transitional care, good primary care.”

Baylor’s research team is working on a follow-up study that would apply the coordinated-care bundle to specific disease management. Youngblood notes that directing specific services at a targeted population—for example, congestive heart failure patients—should show an even more concentrated reduction of 30-day recidivism. “The key is to identify the high-risk groups,” he says. “You can’t apply this to every single patient. That would be low-yield. Your yield is going to come in on the very high-risk folks.” TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Three years ago, Andrew Masica, MD, MSCI, joined the MedProvider Inpatient Care Unit hospitalist group at Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) in Dallas just as the national debate on Medicare recidivism rates was focusing on high-risk populations.

Dr. Masica’s master’s degree in clinical investigation, combined with the roughly 35 hospitalists operating at the 900-bed BUMC, suggested it made sense to see what Baylor’s doctors could add to the conversation. And a study was born: “Reduction of 30-Day Post-Discharge Hospital Readmission or ED Visit Rates in High-Risk Elderly Medical Patients Through Delivery of a Targeted Care Bundle.” The single-center study will be published in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The study found readmission/ED visit rates were lower after 30 days for those given an individualized care bundle of educational information compared with those who received the center’s standard treatment (10% individualized care bundle compared with 38.1% for standard treatment, P=0.04). Analysis also showed that for those patients who had a readmission or post-discharge ED visit, the time interval to the second event was longer in the intervention group compared with the control group (36.2 days to 15.7 days, P=0.05). At 60 days, however, readmission/ED visit rates were not affected positively for the intervention group versus the control group (42.9% vs. 30%, P=0.52).

The study team emphasizes that its small sample size—20 in the intervention group, 21 in the control—make it nearly impossible to extrapolate the results to large population sets; however, the results fuel the debate. “We don’t want to overstate our conclusions,” says Dr. Masica, the principal study investigator. “Important questions need to be asked. Is it the specific characteristics of the care coordinators? Can you reproduce this at other facilities? Is it the care bundle or the personnel? …We view this as early-phase work that people can build upon.”

Expansion Opportunity

Still, Dr. Masica believes hospitalist-centric conclusions can be reached. Since the study used in-house personnel only, other HM groups could easily reproduce the bundle without added expense. Additionally, because the coordinated-care approach involves a checklist of patient interaction activities, not medical procedures, the barrier to replication is further reduced. However, hospitalists will need the cooperation of more than their own medical directors.

In BUMC’s case, that meant the assistance of patient-care support services and the pharmacy department. Liz Youngblood, RN, MBA, supervised the care coordination in her role as vice president of patient-care support services for the Baylor Health Care System. Brian Cohen, PharmD, MS, was the pharmacy lead. Dr. Masica notes the confluence between departments was one of the keys to the reduction in recidivism over the first 30 days post-discharge.

“If you pick the high-risk patients and deliver the care in a bundle, you would be able to improve outcomes,” Dr. Masica says. “When you deliver just pieces of the care—just the coordinated care or just the pharmacist—you get inconsistencies.”

The first struggle BUMC researchers encountered—once they secured funding from Baylor’s Institute for Health Care Research and Improvement—was enrolling enough patients who met the criteria set for the study. The high-risk patient thresholds were:

- At least 70 years old;

- Regular use of at least five medications;

- At least three chronic, comorbid conditions;

- Assistance with at least one activity of daily living; and

- Preadmission residence at home or at an assisted-living facility with a reasonable expectation of disposition back to that residence.

Researchers also wanted patients with common DRGs admitted, and set exclusion criteria as well: lack of fluency in English; admission primarily for a surgical procedure; terminal diagnosis with life expectancy of less than six months; and residency in a long-term care facility. Patients who could not be enrolled within 72 hours of admission were excluded.

Dr. Masica notes hospitalists interested in replicating the research should pay attention to the consent forms they used. When the Baylor team conducted its research from March to September 2007, they used a long-form consent waiver. Baylor’s consent form for similar studies has since been shortened, and Dr. Masica says a less complicated form would have helped encourage more patients to enroll. In the end, 60 patients declined to enroll in the Baylor study and 56 were unable to give their consent due to impairment.

Once enrolled, the patients were delivered the care bundle in stages (see Table 1). Care coordinators (CCs) saw patients daily, instructing them on specific health conditions with an eye toward teaching home care, should post-discharge problems arise. Clinical pharmacists (CPs) visited patients to focus on medication reconciliation and education. CCs and CPs would follow up with post-discharge phone calls to confirm receipt of medical equipment and medications, use and affects of those medications, home-health arrangements, and to schedule follow-up appointments. If patients indicated any issues, the coordinators recommended action plans.

“It would be surprising to find out how little patients really understand about why they’re in the hospital and what they’re being treated for,” Youngblood says. “To have the reinforcement is really valuable.”

Care Continuum

One topic the study skirts is the ever-contentious realm of post-discharge care and who takes over responsibility for patient care. While the Baylor study examined readmission/ED visit rates through 60 days, Dr. Masica says a transitional-care program is the best way to manage that care continuum.

“We did see a difference at 30 days,” Dr. Masica says. “At 60 days, that effectively washed out. That makes sense. You can only control things so much from the hospital side. After 30 days, you need transitional care, good primary care.”

Baylor’s research team is working on a follow-up study that would apply the coordinated-care bundle to specific disease management. Youngblood notes that directing specific services at a targeted population—for example, congestive heart failure patients—should show an even more concentrated reduction of 30-day recidivism. “The key is to identify the high-risk groups,” he says. “You can’t apply this to every single patient. That would be low-yield. Your yield is going to come in on the very high-risk folks.” TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Three years ago, Andrew Masica, MD, MSCI, joined the MedProvider Inpatient Care Unit hospitalist group at Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) in Dallas just as the national debate on Medicare recidivism rates was focusing on high-risk populations.

Dr. Masica’s master’s degree in clinical investigation, combined with the roughly 35 hospitalists operating at the 900-bed BUMC, suggested it made sense to see what Baylor’s doctors could add to the conversation. And a study was born: “Reduction of 30-Day Post-Discharge Hospital Readmission or ED Visit Rates in High-Risk Elderly Medical Patients Through Delivery of a Targeted Care Bundle.” The single-center study will be published in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The study found readmission/ED visit rates were lower after 30 days for those given an individualized care bundle of educational information compared with those who received the center’s standard treatment (10% individualized care bundle compared with 38.1% for standard treatment, P=0.04). Analysis also showed that for those patients who had a readmission or post-discharge ED visit, the time interval to the second event was longer in the intervention group compared with the control group (36.2 days to 15.7 days, P=0.05). At 60 days, however, readmission/ED visit rates were not affected positively for the intervention group versus the control group (42.9% vs. 30%, P=0.52).

The study team emphasizes that its small sample size—20 in the intervention group, 21 in the control—make it nearly impossible to extrapolate the results to large population sets; however, the results fuel the debate. “We don’t want to overstate our conclusions,” says Dr. Masica, the principal study investigator. “Important questions need to be asked. Is it the specific characteristics of the care coordinators? Can you reproduce this at other facilities? Is it the care bundle or the personnel? …We view this as early-phase work that people can build upon.”

Expansion Opportunity

Still, Dr. Masica believes hospitalist-centric conclusions can be reached. Since the study used in-house personnel only, other HM groups could easily reproduce the bundle without added expense. Additionally, because the coordinated-care approach involves a checklist of patient interaction activities, not medical procedures, the barrier to replication is further reduced. However, hospitalists will need the cooperation of more than their own medical directors.

In BUMC’s case, that meant the assistance of patient-care support services and the pharmacy department. Liz Youngblood, RN, MBA, supervised the care coordination in her role as vice president of patient-care support services for the Baylor Health Care System. Brian Cohen, PharmD, MS, was the pharmacy lead. Dr. Masica notes the confluence between departments was one of the keys to the reduction in recidivism over the first 30 days post-discharge.

“If you pick the high-risk patients and deliver the care in a bundle, you would be able to improve outcomes,” Dr. Masica says. “When you deliver just pieces of the care—just the coordinated care or just the pharmacist—you get inconsistencies.”

The first struggle BUMC researchers encountered—once they secured funding from Baylor’s Institute for Health Care Research and Improvement—was enrolling enough patients who met the criteria set for the study. The high-risk patient thresholds were:

- At least 70 years old;

- Regular use of at least five medications;

- At least three chronic, comorbid conditions;

- Assistance with at least one activity of daily living; and

- Preadmission residence at home or at an assisted-living facility with a reasonable expectation of disposition back to that residence.

Researchers also wanted patients with common DRGs admitted, and set exclusion criteria as well: lack of fluency in English; admission primarily for a surgical procedure; terminal diagnosis with life expectancy of less than six months; and residency in a long-term care facility. Patients who could not be enrolled within 72 hours of admission were excluded.

Dr. Masica notes hospitalists interested in replicating the research should pay attention to the consent forms they used. When the Baylor team conducted its research from March to September 2007, they used a long-form consent waiver. Baylor’s consent form for similar studies has since been shortened, and Dr. Masica says a less complicated form would have helped encourage more patients to enroll. In the end, 60 patients declined to enroll in the Baylor study and 56 were unable to give their consent due to impairment.

Once enrolled, the patients were delivered the care bundle in stages (see Table 1). Care coordinators (CCs) saw patients daily, instructing them on specific health conditions with an eye toward teaching home care, should post-discharge problems arise. Clinical pharmacists (CPs) visited patients to focus on medication reconciliation and education. CCs and CPs would follow up with post-discharge phone calls to confirm receipt of medical equipment and medications, use and affects of those medications, home-health arrangements, and to schedule follow-up appointments. If patients indicated any issues, the coordinators recommended action plans.

“It would be surprising to find out how little patients really understand about why they’re in the hospital and what they’re being treated for,” Youngblood says. “To have the reinforcement is really valuable.”

Care Continuum

One topic the study skirts is the ever-contentious realm of post-discharge care and who takes over responsibility for patient care. While the Baylor study examined readmission/ED visit rates through 60 days, Dr. Masica says a transitional-care program is the best way to manage that care continuum.

“We did see a difference at 30 days,” Dr. Masica says. “At 60 days, that effectively washed out. That makes sense. You can only control things so much from the hospital side. After 30 days, you need transitional care, good primary care.”

Baylor’s research team is working on a follow-up study that would apply the coordinated-care bundle to specific disease management. Youngblood notes that directing specific services at a targeted population—for example, congestive heart failure patients—should show an even more concentrated reduction of 30-day recidivism. “The key is to identify the high-risk groups,” he says. “You can’t apply this to every single patient. That would be low-yield. Your yield is going to come in on the very high-risk folks.” TH

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

The latest research you need to know

In This Edition

- Generic vs. brand-name drugs.

- Rapid-response teams and mortality.

- A new prediction rule for mortality in acute pancreatitis.

- Viral causes of community-acquired pneumonia.

- Intensive insulin therapy in the ICU.

- New preoperative and intraoperative risk factors.

- Timing of ICU feedings and mortality.

- Aspirin as primary prevention in diabetics.

Generic, Brand-Name Drugs Used for Cardiovascular Disease Are Clinically Equivalent

Clinical question: Is there a clinical risk when substituting generic drugs for brand-name drugs in the treatment of cardiovascular disease?

Background: Spending on healthcare in the U.S. has reached critical levels. Increasing prescription drug costs make up a large portion of healthcare expenditures. The high cost of medicines directly affect adherence to treatment regimens and contribute to poor health outcomes. Cardiovascular drugs make up the largest portion of outpatient prescription drug spending.

Study design: Systematic review of relevant articles with a meta-analysis performed to determine an aggregate effect size.

Setting: Multiple locations and varied patient populations.

Synopsis: A total of 47 articles were included in the review, of which 38 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The studies measured both clinical efficacy and safety end points. More than half the articles were published prior to 2000. Clinical equivalence was noted in all seven beta-blocker RCTs; 10 of 11 diuretic RCTs; five of seven calcium-channel-blocker RCTs; all three antiplatelet-agent RCTs (clopidogrel, enteric-coated aspirin); two statin RCTs; one ACE-inhibitor RCT; and one alpha-blocker RCT. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, clinical equivalence was noted in all five warfarin RCTs and a single Class 1 anti-arrhythmic-agent RCT.

The aggregate effect size was -0.03 (95% CI, -0.15 to 0.08), which indicates nearly complete overlap of the generic and brand-name distributions. The data show no evidence of superiority of brand-name to generic drugs in clinical outcomes measured in the various studies.

In a separate review of editorials addressing generic substitution for cardiovascular drugs, 53% expressed a negative view of generic-drug substitution.

Bottom line: There is clinical equivalency between generic and brand-name drugs used in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Despite this conclusion, a substantial number of editorials advise against generic substitution, which affects both patient and physician drug preferences.

Citation: Kesselheim A, Misono A, Lee J, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008; 300(21):2514-2526.

RRT Implement-ation Doesn’t Affect Hospitalwide Code Rates or Mortality

Clinical question: Does the use of a rapid-response team (RRT) affect hospitalwide code rates and mortality?

Background: In the 100,000 Lives campaign, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement recommended that hospitals implement RRTs to help reduce preventable, in-hospital deaths. Studies have demonstrated that rates of non-ICU codes decrease after RRT implementation. It is unclear if this translates to changes in mortality rates.

Study design: Prospective cohort study of adult inpatients.

Setting: Saint Luke’s Hospital, a 404-bed tertiary-care academic hospital in Kansas City, Mo.

Synopsis: The hospital documented a total of 376 RRT activations. After RRT implementation, mean hospitalwide code rates decreased to 7.5 per 1,000 admissions from 11.2 per 1,000 admissions. This was not associated with a statistically significant reduction in hospitalwide code rates (adjusted odds ratio 0.76; 95% CI; 0.57-1.01; P=0.06). Secondary analyses noted lower rates of non-ICU codes (0.59; 95% CI, 0.40-0.89) compared with ICU codes (0.95; 95% CI; 0.64-1.43; P=0.03 for interaction). Finally, the RRT implementation was not associated with lower hospital-wide mortality (0.95; 95% CI; 0.81-1.11; P=0.52).

Secondary analyses also revealed few instances of RRT undertreatment or underutilization that may have affected the mortality numbers.

A limitation of this study is that it was slightly underpowered (78%) to detect a significant mortality difference. The findings also represent a single institution experience, and may not be generalized to other adult hospital settings or RRT programs.

Bottom line: Implementation of an RRT does not confer lower rates of hospital-wide code arrests or mortality.

Citation: Chan P, Khalid A, Longmore L, et al. Hospital-wide code rates and mortality before and after implementation of a rapid response team. JAMA. 2008;300(21):2506-2513.

Simple Scoring System Provides Timely Prediction of Mortality in Acute Pancreatitis

Clinical question: How can physicians predict mortality in acute pancreatitis?

Background: Historical predictors of mortality in acute pancreatitis require up to 48 hours of data, such as with the Ranson Criteria, or extensive amounts of data, such as with the APACHE II score. An easier tool is needed to predict which patients are at higher risk of mortality.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Patients in the Cardinal Health clinical outcomes research database, which supports public reporting of hospital performance.

Synopsis: The authors identified patients with the principal diagnosis of pancreatitis from 2000-2001 and explored numerous diagnostic findings available within the first 24 hours. Ultimately, BUN >25, impaired mental status, presence of SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome), age >60, and presence of a pleural effusion were found to be predictive of mortality. These diagnostic findings correspond to the mnemonic BISAP. The BISAP score was then validated in a second cohort that included patients from 2004-2005.

Each finding in the BISAP score was given one point. A score of less than 2 was present in approximately 60% of patients admitted with acute pancreatitis, and corresponded to a mortality of less than 1%. A score of 2 corresponded to a mortality of 2%. Higher scores were associated with steeply increasing mortality, with a score of 5 corresponding with greater than 20% mortality.

The BISAP score performed similarly to the APACHE II score, but the former is easier to calculate on the day of admission and has fewer parameters. A more challenging research step will be to demonstrate that using the BISAP score to determine treatment strategies can affect patient outcomes.

Bottom line: The easy-to-calculate BISAP score is a new method for predicting mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. This tool should help hospitalists determine, on the day of admission, to what extent patients with acute pancreatitis need aggressive management, such as ICU admission and early involvement of specialists.

Citation: Wu B, Johannes R, Sun X, Tabak Y, Conwell D, Banks P. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut. 2008;57(12): 1698-1703.

Nasal Swabs Identify Viral Causes in CAP Patients

Clinical question: How often is viral infection associated with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in adults?

Background: CAP is a clinically important disease that is associated with significant hospitalization and mortality. CAP treatment guidelines acknowledge respiratory viruses as an etiology for pneumonia, but few recommendations are made regarding management of these viral infections.

Study design: Prospective study.

Setting: Five hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, from 2004-2006.

Synopsis: The authors enrolled 193 hospitalized adults, median age 71. Nucleic amplification tests (NATs) from nasopharyngeal swab specimens were tested for human metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus 1-4, coronaviruses, and adenovirus.

Fifteen percent of these patients had a nasal swab positive for a viral infection. Interestingly, 4% of patients had both a positive viral nasal swab and positive bacterial cultures. Compared with bacterial infection, patients with viral infection tended to be older (76 vs. 64 years, P=0.01), have limited ambulation (66% vs. 32%, P=0.006), and have a history of cardiac disease (66% vs. 32%, P=0.02). Patients with bacterial pneumonia showed a statistically significant trend toward having chest pain, an abnormal white blood count, and a lobar infiltrate on chest X-ray.

Further investigations might look at how nasal swab data could be used to improve infection control within the hospital for patients found to have easily transmissible viruses. Further research could explore the feasibility of avoiding antibiotic use in patients found to have viral pneumonia, assuming bacterial co-infection is reliably excluded.

Bottom line: Nasal swabs using NAT technology could play a significant role in identifying pathogens in CAP patients. How this technology should affect clinical decision-making and how it might improve outcomes remains unknown.

Citation: Johnstone J, Majumdar S, Fox J, Marrie T. Viral infection in adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: prevalence, pathogens, and presentation. Chest. 2008;134(6):1141-1148.

Intensive Insulin Therapy Doesn’t Reduce ICU Mortality

Clinical question: Does the use of intensive insulin therapy decrease mortality in the intensive-care unit (ICU)?

Background: In 2001, Van den Berghe et al (N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1359-67) reported a reduction in morbidity and mortality with intensive insulin therapy (IIT) in surgical ICU patients. This study led to the adoption of IIT protocols in many hospitals. Since 2001, further studies have failed to reproduce the same dramatic benefit of IIT.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: National Guard King Abdulaziz Medical City, a tertiary-care teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia.

Synopsis: Patients were included in this study if they were 18 years or older with serum glucose levels greater than 110 mg/dL during the first 24 hours of ICU admission. There were multiple exclusion criteria, including patients with Type I diabetes, documented hypoglycemia on ICU admission (glucose <40), or diabetic ketoacidosis.

Enrolled patients were randomized to IIT or conventional insulin therapy (CIT). A multidisciplinary team designed the protocols to maintain glucose levels of 80 to 110 mg/dL and 180 to 200 mg/dL in the IIT and the CIT groups, respectively. The primary endpoint measured was ICU mortality.

The study did not produce a statistically significant difference in ICU mortality (13.5% for IIT vs. 17.1% for CIT; P=0.30). The adjusted hypoglycemia rate was 6.8 per 100 treatment days with IIT and 0.4 per 100 treatment days with CIT (P<0.0001). Patients with hypoglycemia had higher ICU mortality (23.8% vs. 13.7%, P=0.02).

In the measurement of secondary endpoints, there was a trend toward lower episodes of severe sepsis and septic shock in the IIT group (20.7% in IIT vs. 27.2% in CIT, P=0.08). However, this result was not statistically significant.

Bottom line: This well-designed study failed to show a survival benefit with IIT use in the critical-care setting. Given the findings of this and several other recent studies, one should question whether IIT should be prescribed as the standard of care in all critically-ill patients.

Citation: Arabi Y, Dabbagh O, Tamim H, et al. Intensive versus conventional insulin therapy: a randomized controlled trial in medical and surgical critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(12):3190-3197.

Preoperative and Intraoperative Predictors of Cardiac Adverse Events

Clinical question: What are the incidence and risk factors for perioperative cardiac adverse events after noncardiac surgery?

Background: In the past few decades, the incidence of cardiac adverse events (CAEs) for a general surgery population has remained largely unchanged (approximately 1%). This is in spite of multiple studies evaluating predictive models and attempts at preventive treatment, including preoperative coronary revascularization and perioperative beta blockers.

Study design: Prospective observational study.

Setting: Single, large, tertiary-care university hospital.

Synopsis: A total of 7,740 cases were reviewed in this study, which consisted of general surgery (4,937), vascular surgery (1,846), and urological surgery (957). A trained nurse followed up for perioperative CAEs as many as 30 days after the operation via medical chart review, phone calls, and letters. CAEs were defined as: Q-wave myocardial infarction (MI), non-ST elevation MI, cardiac arrest, or new cardiac dysrhythmia. A total of 83 CAEs (1.1% of patients) had cardiac arrest, with cardiac dysrhythmia being most common.

A total of seven preoperative risk factors were identified as independent predictors for CAEs: age 68, BMI 30, emergent surgery, prior coronary intervention or cardiac surgery, active congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and hypertension. In addition, two intraoperative risk factors were identified: intraoperative transfusion of packed red blood cells and operative duration of 3.8 hours. (The P value was 0.05 for all independent predictors.)

A further evaluation of intraoperative parameters of high-risk patients experiencing a CAE showed that these patients were more likely to have an episode of mean arterial pressure (MAP) <50 mmHg, an episode of 40% decrease in MAP, and an episode of tachycardia (heart rate >100).

Bottom line: A combination of preoperative predictors and intraoperative elements can help improve risk assessment for perioperative CAEs after noncardiac surgery.

Citation: Kheterpal S, O’Reilly M, Englesbe M, et al. Preoperative and intraoperative predictors of cardiac adverse events after general, vascular, and urological surgery. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(1):58-66.

Early Feeding in the ICU Does Not Affect Hospital Mortality

Clinical question: Will implementing evidence-based feeding guidelines improve feeding practices and reduce mortality in ICU patients?

Background: There is evidence suggesting that providing nutritional support to ICU patients within 24 hours of admission may decrease mortality. It is widely understood that patient care varies between ICUs, and there exist no uniform, evidence-based guidelines for nutritional support. Many patients remain unfed after 48 hours.

Study design: Cluster, randomized-controlled trial.

Setting: ICUs in 27 community and tertiary-care hospitals in Australia and New Zealand.

Synopsis: Hospitals were randomized to intervention or control groups. Dietitian and intensivist co-investigators from intervention ICUs developed guidelines using the Clinical Practice Guideline Development Cycle. Control ICUs were requested to make no new ICU nutritional management changes. The study enrolled 1,118 eligible patients and included adults expected to stay longer than two days. Excluded were patients taking oral diets, patients receiving palliative care or with suspected brain death, and patients sent from other facilities.

Guidelines were implemented using several methods—educational outreach visits, one-on-one conversations, active reminders, passive reminders, and educational in-services. The guidelines were successful in evoking significant practice changes in all of the intervention ICUs. Significantly more patients received nutritional support during their ICU stays in guideline ICUs, and patients in these ICUs were fed significantly earlier. There were, however, no significant differences between guideline and control ICUs with regard to hospital discharge mortality (28.9% vs. 27.4%; 95% CI; -6.3% to 12.0%; P=0.75). The groups also showed no statistical difference in hospital or ICU length of stay.

Bottom line: Significantly more patients in the guideline ICUs were fed within 24 hours, but this did not translate into improvements in mortality or other clinical outcomes.

Citation: Doig G, Simpson F, Finfer S, et al. Effect of evidence-based feeding guidelines on mortality of critically ill adults: a cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2731-2741.

Low-Dose Aspirin Doesn’t Reduce Cardiovascular Events in Type 2 Diabetes Patients

Clinical question: Is low-dose aspirin effective for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic events in patients with Type 2 diabetes?

Background: Diabetes is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular events. Several prior studies have shown that aspirin therapy is effective as a secondary prevention strategy for cardiovascular events. The American Diabetes Association also recommends use of aspirin as a primary prevention strategy. Clinical trial data is currently insufficient in this area.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, open-label, controlled trial with blinded endpoint assessment.

Setting: 163 institutions in Japan.

Synopsis: The study enrolled 2,539 diabetic patients between 30 and 85 years old—mean age was 65—and included patients without EKG changes or a significant history or ongoing treatment of atherosclerotic disease. Patients were randomly assigned into an aspirin group (81 mg or 100 mg once daily) or a nonaspirin group. Patients had a median follow up of 4.37 years.

The primary endpoint was any atherosclerotic event, ranging from sudden death to ischemic heart disease or stroke. The incidence of atherosclerotic events was not statistically different in the aspirin group (68 events, 5.4%) than in the nonaspirin group (86 events, 6.7%) (HR, 0.80; 95% CI; 0.58-1.10; log-rank test, P=0.16). However, there was a suggested benefit of primary prevention in the subgroup aged 65 years or older. In addition, the combined endpoint of fatal coronary and cerebrovascular events occurred in one patient in the aspirin group and 10 patients in the nonaspirin group (HR, 0.10; 95 % CI, 0.01-0.79; P=.0037). This study is limited by the low incidence of atherosclerotic disease in Japan.

Bottom line: Low-dose aspirin used in patients with Type 2 diabetes does not significantly demonstrate primary prevention of cardiovascular events.

Citation: Ogawa H, Nakayama M, Morimoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(18):2134-2141. TH

In This Edition

- Generic vs. brand-name drugs.

- Rapid-response teams and mortality.

- A new prediction rule for mortality in acute pancreatitis.

- Viral causes of community-acquired pneumonia.

- Intensive insulin therapy in the ICU.

- New preoperative and intraoperative risk factors.

- Timing of ICU feedings and mortality.

- Aspirin as primary prevention in diabetics.

Generic, Brand-Name Drugs Used for Cardiovascular Disease Are Clinically Equivalent

Clinical question: Is there a clinical risk when substituting generic drugs for brand-name drugs in the treatment of cardiovascular disease?

Background: Spending on healthcare in the U.S. has reached critical levels. Increasing prescription drug costs make up a large portion of healthcare expenditures. The high cost of medicines directly affect adherence to treatment regimens and contribute to poor health outcomes. Cardiovascular drugs make up the largest portion of outpatient prescription drug spending.

Study design: Systematic review of relevant articles with a meta-analysis performed to determine an aggregate effect size.

Setting: Multiple locations and varied patient populations.

Synopsis: A total of 47 articles were included in the review, of which 38 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The studies measured both clinical efficacy and safety end points. More than half the articles were published prior to 2000. Clinical equivalence was noted in all seven beta-blocker RCTs; 10 of 11 diuretic RCTs; five of seven calcium-channel-blocker RCTs; all three antiplatelet-agent RCTs (clopidogrel, enteric-coated aspirin); two statin RCTs; one ACE-inhibitor RCT; and one alpha-blocker RCT. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, clinical equivalence was noted in all five warfarin RCTs and a single Class 1 anti-arrhythmic-agent RCT.

The aggregate effect size was -0.03 (95% CI, -0.15 to 0.08), which indicates nearly complete overlap of the generic and brand-name distributions. The data show no evidence of superiority of brand-name to generic drugs in clinical outcomes measured in the various studies.

In a separate review of editorials addressing generic substitution for cardiovascular drugs, 53% expressed a negative view of generic-drug substitution.

Bottom line: There is clinical equivalency between generic and brand-name drugs used in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Despite this conclusion, a substantial number of editorials advise against generic substitution, which affects both patient and physician drug preferences.

Citation: Kesselheim A, Misono A, Lee J, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008; 300(21):2514-2526.

RRT Implement-ation Doesn’t Affect Hospitalwide Code Rates or Mortality

Clinical question: Does the use of a rapid-response team (RRT) affect hospitalwide code rates and mortality?

Background: In the 100,000 Lives campaign, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement recommended that hospitals implement RRTs to help reduce preventable, in-hospital deaths. Studies have demonstrated that rates of non-ICU codes decrease after RRT implementation. It is unclear if this translates to changes in mortality rates.

Study design: Prospective cohort study of adult inpatients.

Setting: Saint Luke’s Hospital, a 404-bed tertiary-care academic hospital in Kansas City, Mo.

Synopsis: The hospital documented a total of 376 RRT activations. After RRT implementation, mean hospitalwide code rates decreased to 7.5 per 1,000 admissions from 11.2 per 1,000 admissions. This was not associated with a statistically significant reduction in hospitalwide code rates (adjusted odds ratio 0.76; 95% CI; 0.57-1.01; P=0.06). Secondary analyses noted lower rates of non-ICU codes (0.59; 95% CI, 0.40-0.89) compared with ICU codes (0.95; 95% CI; 0.64-1.43; P=0.03 for interaction). Finally, the RRT implementation was not associated with lower hospital-wide mortality (0.95; 95% CI; 0.81-1.11; P=0.52).