User login

Make the Diagnosis - February 2016

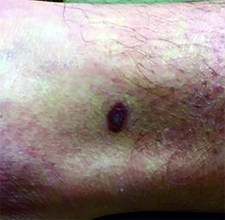

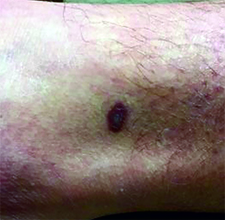

Diagnosis: Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an uncommon, noninfectious neutrophilic dermatosis that results in chronic ulcerative lesions. This disease process favors adult women and can be associated with systemic diseases in the majority of cases. The most common underlying systemic ailments include inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, infection, and hematologic malignancy; it can also be drug induced.

Typically, the lesions begin as an erythematous pustule or nodule on an extremity. As was the case with our patient, a history of a "spider bite" or other arthropod assault may be elicited in the history as patients try to attribute a cause to the development of the initial ulceration. The pustule then develops into an ulcer with a characteristic necrotic, violaceous undermined border with a purulent base. Also, this disease process is associated with pathergy, in which minor trauma can induce additional lesions at remote sites.

There are four well-known types of pyoderma gangrenosum including the classic ulcerative lesions, pustular, bullous, and superficial granulomatous type, also known as vegetative PG. The pustular type may be seen more frequently in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, the bullous type may predominate in hematologic disorders, and the superficial granulomatous type is known to occur following surgery or other trauma.

The pathology of lesions can be nonspecific. However, in untreated lesions, widespread infiltration of neutrophils can be demonstrated at the base of the ulcers with accompanying necrosis at the periphery of lesions.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an uncommon, noninfectious neutrophilic dermatosis that results in chronic ulcerative lesions. This disease process favors adult women and can be associated with systemic diseases in the majority of cases. The most common underlying systemic ailments include inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, infection, and hematologic malignancy; it can also be drug induced.

Typically, the lesions begin as an erythematous pustule or nodule on an extremity. As was the case with our patient, a history of a "spider bite" or other arthropod assault may be elicited in the history as patients try to attribute a cause to the development of the initial ulceration. The pustule then develops into an ulcer with a characteristic necrotic, violaceous undermined border with a purulent base. Also, this disease process is associated with pathergy, in which minor trauma can induce additional lesions at remote sites.

There are four well-known types of pyoderma gangrenosum including the classic ulcerative lesions, pustular, bullous, and superficial granulomatous type, also known as vegetative PG. The pustular type may be seen more frequently in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, the bullous type may predominate in hematologic disorders, and the superficial granulomatous type is known to occur following surgery or other trauma.

The pathology of lesions can be nonspecific. However, in untreated lesions, widespread infiltration of neutrophils can be demonstrated at the base of the ulcers with accompanying necrosis at the periphery of lesions.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an uncommon, noninfectious neutrophilic dermatosis that results in chronic ulcerative lesions. This disease process favors adult women and can be associated with systemic diseases in the majority of cases. The most common underlying systemic ailments include inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, infection, and hematologic malignancy; it can also be drug induced.

Typically, the lesions begin as an erythematous pustule or nodule on an extremity. As was the case with our patient, a history of a "spider bite" or other arthropod assault may be elicited in the history as patients try to attribute a cause to the development of the initial ulceration. The pustule then develops into an ulcer with a characteristic necrotic, violaceous undermined border with a purulent base. Also, this disease process is associated with pathergy, in which minor trauma can induce additional lesions at remote sites.

There are four well-known types of pyoderma gangrenosum including the classic ulcerative lesions, pustular, bullous, and superficial granulomatous type, also known as vegetative PG. The pustular type may be seen more frequently in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, the bullous type may predominate in hematologic disorders, and the superficial granulomatous type is known to occur following surgery or other trauma.

The pathology of lesions can be nonspecific. However, in untreated lesions, widespread infiltration of neutrophils can be demonstrated at the base of the ulcers with accompanying necrosis at the periphery of lesions.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 42-year-old woman with a 10-year history of Crohn's disease, treated with weekly subcutaneous injections of adalimumab, and hypertension presented with ulcerations on the lower extremities. She stated that the ulcerations began after she had been camping and reported being bitten by several ants during the trip, approximately 3 months earlier.

Make the Diagnosis - January 2016

Diagnosis: Urticaria pigmentosa

Urticaria pigmentosa (UP), also known as cutaneous mastocytosis, is characterized by the presence of pigmented macular and/or papular lesions associated with severe pruritis that can appear on any part of the body. With increased scratching and/or exposure to heat, the lesions become elevated. This phenomenon is known as Darier’s sign. The urticarial lesions can progress to become fluid-filled blisters. UP can rarely progress to systemic mastocytosis and present with systemic symptoms that are more common in adults, including headache, fatigue, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and tachycardia.

UP has been associated with increased inflammatory mast cells that abnormally collect in the skin. Mast cells specialize in producing histamine. In UP, the overproliferation of mast cells, secondary to point mutations in proto-oncogene c-kit binding to mast cell growth factor (MCGF), leads to an abundance of inflammatory chemicals, which produces the characteristic itching and presenting symptoms.

Although the pathophysiology of UP is known, the exact etiology is unclear. Certain medications that can cause mast-cell degranulation have been implicated, such as aspirin, NSAIDs, narcotics, alcohol, and anticholinergics. Children with allergies such as asthma are known to have an increased predisposition to UP, which typically presents in the first year of life and is self-limited by adolescence. Some cases sporadically appear, but others may be secondary to genetic inheritance as an autosomal dominant trait.

Diagnosis of UP is made by the presence of the characteristic skin lesions but can be confirmed by microscopic evaluation. A positive Darier’s sign on physical exam and lab testing for elevated histamine can aid in the diagnosis. UP is often mistaken for moles or insect bites on initial presentation; however, the persistence of the lesions for months to years is a distinguishing factor.

Given the self-limiting nature of UP, the treatment is symptomatic and supportive. Topical steroids and antihistamines can be useful to treat severe pruritis. In addition, PUVA has been shown to be an effective treatment for UP in adults.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Parteek Singla and Dr. Damon McClain of Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, N.C.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Urticaria pigmentosa

Urticaria pigmentosa (UP), also known as cutaneous mastocytosis, is characterized by the presence of pigmented macular and/or papular lesions associated with severe pruritis that can appear on any part of the body. With increased scratching and/or exposure to heat, the lesions become elevated. This phenomenon is known as Darier’s sign. The urticarial lesions can progress to become fluid-filled blisters. UP can rarely progress to systemic mastocytosis and present with systemic symptoms that are more common in adults, including headache, fatigue, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and tachycardia.

UP has been associated with increased inflammatory mast cells that abnormally collect in the skin. Mast cells specialize in producing histamine. In UP, the overproliferation of mast cells, secondary to point mutations in proto-oncogene c-kit binding to mast cell growth factor (MCGF), leads to an abundance of inflammatory chemicals, which produces the characteristic itching and presenting symptoms.

Although the pathophysiology of UP is known, the exact etiology is unclear. Certain medications that can cause mast-cell degranulation have been implicated, such as aspirin, NSAIDs, narcotics, alcohol, and anticholinergics. Children with allergies such as asthma are known to have an increased predisposition to UP, which typically presents in the first year of life and is self-limited by adolescence. Some cases sporadically appear, but others may be secondary to genetic inheritance as an autosomal dominant trait.

Diagnosis of UP is made by the presence of the characteristic skin lesions but can be confirmed by microscopic evaluation. A positive Darier’s sign on physical exam and lab testing for elevated histamine can aid in the diagnosis. UP is often mistaken for moles or insect bites on initial presentation; however, the persistence of the lesions for months to years is a distinguishing factor.

Given the self-limiting nature of UP, the treatment is symptomatic and supportive. Topical steroids and antihistamines can be useful to treat severe pruritis. In addition, PUVA has been shown to be an effective treatment for UP in adults.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Parteek Singla and Dr. Damon McClain of Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, N.C.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Urticaria pigmentosa

Urticaria pigmentosa (UP), also known as cutaneous mastocytosis, is characterized by the presence of pigmented macular and/or papular lesions associated with severe pruritis that can appear on any part of the body. With increased scratching and/or exposure to heat, the lesions become elevated. This phenomenon is known as Darier’s sign. The urticarial lesions can progress to become fluid-filled blisters. UP can rarely progress to systemic mastocytosis and present with systemic symptoms that are more common in adults, including headache, fatigue, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and tachycardia.

UP has been associated with increased inflammatory mast cells that abnormally collect in the skin. Mast cells specialize in producing histamine. In UP, the overproliferation of mast cells, secondary to point mutations in proto-oncogene c-kit binding to mast cell growth factor (MCGF), leads to an abundance of inflammatory chemicals, which produces the characteristic itching and presenting symptoms.

Although the pathophysiology of UP is known, the exact etiology is unclear. Certain medications that can cause mast-cell degranulation have been implicated, such as aspirin, NSAIDs, narcotics, alcohol, and anticholinergics. Children with allergies such as asthma are known to have an increased predisposition to UP, which typically presents in the first year of life and is self-limited by adolescence. Some cases sporadically appear, but others may be secondary to genetic inheritance as an autosomal dominant trait.

Diagnosis of UP is made by the presence of the characteristic skin lesions but can be confirmed by microscopic evaluation. A positive Darier’s sign on physical exam and lab testing for elevated histamine can aid in the diagnosis. UP is often mistaken for moles or insect bites on initial presentation; however, the persistence of the lesions for months to years is a distinguishing factor.

Given the self-limiting nature of UP, the treatment is symptomatic and supportive. Topical steroids and antihistamines can be useful to treat severe pruritis. In addition, PUVA has been shown to be an effective treatment for UP in adults.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Parteek Singla and Dr. Damon McClain of Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, N.C.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Otherwise healthy 11-month-old female twins presented with a mildly pruritic rash that had been present since birth. There was no history of prolonged nausea, diarrhea, or vomiting. There was no family history of mast cell diseases. The girls were not taking any medications. On exam, there were hyperpigmented macules, patches, and papules mostly on the trunk but also on the extremities. A Darier’s sign was noted when firmly scratching with a tongue depressor

Make the Diagnosis - December 2015

Diagnosis: Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), also known as immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is characterized by palpable purpura, abdominal pain, renal disease, arthritis and/or arthralgia. HSP affects all ages, but is most common in children (the mean age of onset is between six and seven years of age). It also has a slight predilection for males, as well as whites and Asians. Patients are more likely to present during the fall, winter, and spring. It is thought that HSP may be associated with infections that are more prevalent during these times of the year.

Patients typically have purpura and joint or abdominal pain, although some may present without significant skin manifestations or pain. The rash associated with HSP may appear as erythematous macules or papules that coalesce and evolve into palpable purpura with petechiae, ecchymoses, and/or subcutaneous edema. The skin is typically affected in areas that are more dependent or experience more pressure, such as the lower extremities or buttocks. A more diffuse distribution across the entire body can be seen in those who are nonambulatory.

The arthritis associated with HSP usually affects the lower extremities, and it is oligoarticular, nondeforming, and transient, with prominent swelling and tenderness. Gastrointestinal involvement may manifest as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, transient paralytic ileus, hemorrhage, bowel ischemia, intussusception (rare in adults), and/or bowel perforation. These symptoms tend to develop 1 week after the rash, but there are reports of gastrointestinal complaints preceding all other manifestations of HSP.

Additionally, there can be renal involvement, which is more common in adults. These patients may experience hematuria with or without red blood cell casts, nephrotic range proteinuria, and/or elevated serum creatinine. Other less common symptoms that have been reported in patients with HSP include scrotal pain and swelling, headaches, seizures, ataxia, central and peripheral neuropathies, impaired lung diffusion capacity, keratitis, and uveitis.

The diagnosis of HSP is classically based upon clinical presentation. The diagnosis may be complicated in cases in which patients do not present with classic signs, such as palpable purpura of the lower extremities and buttocks. In these situations, a biopsy of the skin or kidney may aid in the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for HSP includes acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy, coagulopathies, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hypersensitivity vasculitis, IgA nephropathy, immune thrombocytopenia purpura, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, reactive arthritis, rheumatic fever, small vessel vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

The etiology of HSP is unclear. Most believe that it is an immune-mediated vasculitis with genetic and environmental influences. In HSP, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with deposition of IgA immune complexes, complement component 3 (C3), and fibrin in the affected vessel walls. Small vessels within the papillary dermis are usually present with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and monocytes.

The treatment of HSP usually consists of supportive care, since most patients will recover spontaneously. Therefore, hydration, rest, and pain relief are essential. Other treatment modalities may be required for more severe or extensive HSP and its complications.

Our patient’s biopsy results were consistent with a leukocytoclastic vasculitis. His biopsy revealed an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear dust with extravasation of erythrocytes and fibrin in the walls of small blood vessels, along with prominent papillary dermal edema and subepidermal vesiculation. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in upper dermal blood vessels. The patient also had renal involvement that was confirmed with a renal biopsy.

This case and photos are courtesy of Tanya Greywal, University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Brooke Resh Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), also known as immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is characterized by palpable purpura, abdominal pain, renal disease, arthritis and/or arthralgia. HSP affects all ages, but is most common in children (the mean age of onset is between six and seven years of age). It also has a slight predilection for males, as well as whites and Asians. Patients are more likely to present during the fall, winter, and spring. It is thought that HSP may be associated with infections that are more prevalent during these times of the year.

Patients typically have purpura and joint or abdominal pain, although some may present without significant skin manifestations or pain. The rash associated with HSP may appear as erythematous macules or papules that coalesce and evolve into palpable purpura with petechiae, ecchymoses, and/or subcutaneous edema. The skin is typically affected in areas that are more dependent or experience more pressure, such as the lower extremities or buttocks. A more diffuse distribution across the entire body can be seen in those who are nonambulatory.

The arthritis associated with HSP usually affects the lower extremities, and it is oligoarticular, nondeforming, and transient, with prominent swelling and tenderness. Gastrointestinal involvement may manifest as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, transient paralytic ileus, hemorrhage, bowel ischemia, intussusception (rare in adults), and/or bowel perforation. These symptoms tend to develop 1 week after the rash, but there are reports of gastrointestinal complaints preceding all other manifestations of HSP.

Additionally, there can be renal involvement, which is more common in adults. These patients may experience hematuria with or without red blood cell casts, nephrotic range proteinuria, and/or elevated serum creatinine. Other less common symptoms that have been reported in patients with HSP include scrotal pain and swelling, headaches, seizures, ataxia, central and peripheral neuropathies, impaired lung diffusion capacity, keratitis, and uveitis.

The diagnosis of HSP is classically based upon clinical presentation. The diagnosis may be complicated in cases in which patients do not present with classic signs, such as palpable purpura of the lower extremities and buttocks. In these situations, a biopsy of the skin or kidney may aid in the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for HSP includes acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy, coagulopathies, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hypersensitivity vasculitis, IgA nephropathy, immune thrombocytopenia purpura, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, reactive arthritis, rheumatic fever, small vessel vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

The etiology of HSP is unclear. Most believe that it is an immune-mediated vasculitis with genetic and environmental influences. In HSP, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with deposition of IgA immune complexes, complement component 3 (C3), and fibrin in the affected vessel walls. Small vessels within the papillary dermis are usually present with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and monocytes.

The treatment of HSP usually consists of supportive care, since most patients will recover spontaneously. Therefore, hydration, rest, and pain relief are essential. Other treatment modalities may be required for more severe or extensive HSP and its complications.

Our patient’s biopsy results were consistent with a leukocytoclastic vasculitis. His biopsy revealed an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear dust with extravasation of erythrocytes and fibrin in the walls of small blood vessels, along with prominent papillary dermal edema and subepidermal vesiculation. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in upper dermal blood vessels. The patient also had renal involvement that was confirmed with a renal biopsy.

This case and photos are courtesy of Tanya Greywal, University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Brooke Resh Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), also known as immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is characterized by palpable purpura, abdominal pain, renal disease, arthritis and/or arthralgia. HSP affects all ages, but is most common in children (the mean age of onset is between six and seven years of age). It also has a slight predilection for males, as well as whites and Asians. Patients are more likely to present during the fall, winter, and spring. It is thought that HSP may be associated with infections that are more prevalent during these times of the year.

Patients typically have purpura and joint or abdominal pain, although some may present without significant skin manifestations or pain. The rash associated with HSP may appear as erythematous macules or papules that coalesce and evolve into palpable purpura with petechiae, ecchymoses, and/or subcutaneous edema. The skin is typically affected in areas that are more dependent or experience more pressure, such as the lower extremities or buttocks. A more diffuse distribution across the entire body can be seen in those who are nonambulatory.

The arthritis associated with HSP usually affects the lower extremities, and it is oligoarticular, nondeforming, and transient, with prominent swelling and tenderness. Gastrointestinal involvement may manifest as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, transient paralytic ileus, hemorrhage, bowel ischemia, intussusception (rare in adults), and/or bowel perforation. These symptoms tend to develop 1 week after the rash, but there are reports of gastrointestinal complaints preceding all other manifestations of HSP.

Additionally, there can be renal involvement, which is more common in adults. These patients may experience hematuria with or without red blood cell casts, nephrotic range proteinuria, and/or elevated serum creatinine. Other less common symptoms that have been reported in patients with HSP include scrotal pain and swelling, headaches, seizures, ataxia, central and peripheral neuropathies, impaired lung diffusion capacity, keratitis, and uveitis.

The diagnosis of HSP is classically based upon clinical presentation. The diagnosis may be complicated in cases in which patients do not present with classic signs, such as palpable purpura of the lower extremities and buttocks. In these situations, a biopsy of the skin or kidney may aid in the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for HSP includes acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy, coagulopathies, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hypersensitivity vasculitis, IgA nephropathy, immune thrombocytopenia purpura, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, reactive arthritis, rheumatic fever, small vessel vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

The etiology of HSP is unclear. Most believe that it is an immune-mediated vasculitis with genetic and environmental influences. In HSP, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with deposition of IgA immune complexes, complement component 3 (C3), and fibrin in the affected vessel walls. Small vessels within the papillary dermis are usually present with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and monocytes.

The treatment of HSP usually consists of supportive care, since most patients will recover spontaneously. Therefore, hydration, rest, and pain relief are essential. Other treatment modalities may be required for more severe or extensive HSP and its complications.

Our patient’s biopsy results were consistent with a leukocytoclastic vasculitis. His biopsy revealed an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear dust with extravasation of erythrocytes and fibrin in the walls of small blood vessels, along with prominent papillary dermal edema and subepidermal vesiculation. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in upper dermal blood vessels. The patient also had renal involvement that was confirmed with a renal biopsy.

This case and photos are courtesy of Tanya Greywal, University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Brooke Resh Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 40-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented for progressive asymptomatic blisters on the feet, and erythematous lesions on the arms, legs, and trunk. His symptoms began with edema of the feet after a long flight to the Philippines. After a few days, erosions and bullae began forming on his dorsal feet. He was initially evaluated in the Philippines by his primary care physician,who treated him with antibiotics. The patient soon developed pruritic red bumps on his forearms and trunk. The patient was later seen in the emergency department in the United States. At that time, his physical exam was significant for large bullae on a dusky base on the bilateral dorsal feet, and scattered erythematous papules and violaceous macules with dusky centers on the legs, arms, and trunk.

Make the Diagnosis - November 2015

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer diagnosed in the United States, with approximately 2.8 million cases diagnosed annually, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation. While a minority of cases are linked to genetic syndromes (e.g., basal cell nevus syndrome), most cases result from ultraviolet sun exposure. A power law model was recently described linking ultraviolet exposure and incidence of basal cell carcinoma.

Many diagnosed BCC cases are small (< 1cm in size) and easily treated in the clinic. In cases where treatment is delayed for years due to financial, psychological, or psychiatric reasons, tumors can cause significant local tissue destruction and grow to alarming sizes.

The differential diagnosis of BCC may vary depending on the clinical sub-type (e.g., superficial, nodular, infiltrative, etc). Nodular BCC may mimic adnexal neoplasms, intradermal melanocytic nevi, Merkel cell carcinoma, or even amelanotic melanoma. Superficial BCC may mimic a lichenoid keratosis, Bowen’s disease, or other inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis and dermatitis. A larger lesion may mimic chronic infections such as mycetoma, or distant metastases from another primary carcinoma (breast or renal). Location and history can assist with teasing out the probable cause.

While diagnosis of this lesion can be made based on history and clinical appearance, this is best assisted with a biopsy, preferably a punch or incisional biopsy as chronic scarring and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may affect the pathologic diagnosis. Bacteria often colonize these large tumors and can lead to secondary infections. In this patient, maggots were noted in the skin.

While there are multiple modalities available for treating small tumors (e.g., topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, electrodessication and curettage, excision, Mohs), larger tumors are often handled differently. While some might consider radiation therapy in this case, typically Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice. Oral vismodegib, a smoothened inhibitor, has been marketed for locally advanced basal cell carcinoma and has been used as a primary or adjunctive therapy with Mohs in tumors of this size. One important factor determining the choice of treatment is whether the primary tumor has spread. In tumors who have been left untreated for a long time, it is reasonable to image the patient to evaluate for metastases.

We present this case as an example where Mohs provided immediate definitive treatment. This tumor was cleared in 1 stage, with 67 slides read to evaluate the entire peripheral and deep margin. The Mohs surgery was performed under local anesthesia with no additional sedatives and 3-0 nylon sutures were used to approximate the wound. A two month follow-up photo is shown showing an almost healed surgical wound with an acceptable cosmetic result.

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer diagnosed in the United States, with approximately 2.8 million cases diagnosed annually, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation. While a minority of cases are linked to genetic syndromes (e.g., basal cell nevus syndrome), most cases result from ultraviolet sun exposure. A power law model was recently described linking ultraviolet exposure and incidence of basal cell carcinoma.

Many diagnosed BCC cases are small (< 1cm in size) and easily treated in the clinic. In cases where treatment is delayed for years due to financial, psychological, or psychiatric reasons, tumors can cause significant local tissue destruction and grow to alarming sizes.

The differential diagnosis of BCC may vary depending on the clinical sub-type (e.g., superficial, nodular, infiltrative, etc). Nodular BCC may mimic adnexal neoplasms, intradermal melanocytic nevi, Merkel cell carcinoma, or even amelanotic melanoma. Superficial BCC may mimic a lichenoid keratosis, Bowen’s disease, or other inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis and dermatitis. A larger lesion may mimic chronic infections such as mycetoma, or distant metastases from another primary carcinoma (breast or renal). Location and history can assist with teasing out the probable cause.

While diagnosis of this lesion can be made based on history and clinical appearance, this is best assisted with a biopsy, preferably a punch or incisional biopsy as chronic scarring and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may affect the pathologic diagnosis. Bacteria often colonize these large tumors and can lead to secondary infections. In this patient, maggots were noted in the skin.

While there are multiple modalities available for treating small tumors (e.g., topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, electrodessication and curettage, excision, Mohs), larger tumors are often handled differently. While some might consider radiation therapy in this case, typically Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice. Oral vismodegib, a smoothened inhibitor, has been marketed for locally advanced basal cell carcinoma and has been used as a primary or adjunctive therapy with Mohs in tumors of this size. One important factor determining the choice of treatment is whether the primary tumor has spread. In tumors who have been left untreated for a long time, it is reasonable to image the patient to evaluate for metastases.

We present this case as an example where Mohs provided immediate definitive treatment. This tumor was cleared in 1 stage, with 67 slides read to evaluate the entire peripheral and deep margin. The Mohs surgery was performed under local anesthesia with no additional sedatives and 3-0 nylon sutures were used to approximate the wound. A two month follow-up photo is shown showing an almost healed surgical wound with an acceptable cosmetic result.

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer diagnosed in the United States, with approximately 2.8 million cases diagnosed annually, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation. While a minority of cases are linked to genetic syndromes (e.g., basal cell nevus syndrome), most cases result from ultraviolet sun exposure. A power law model was recently described linking ultraviolet exposure and incidence of basal cell carcinoma.

Many diagnosed BCC cases are small (< 1cm in size) and easily treated in the clinic. In cases where treatment is delayed for years due to financial, psychological, or psychiatric reasons, tumors can cause significant local tissue destruction and grow to alarming sizes.

The differential diagnosis of BCC may vary depending on the clinical sub-type (e.g., superficial, nodular, infiltrative, etc). Nodular BCC may mimic adnexal neoplasms, intradermal melanocytic nevi, Merkel cell carcinoma, or even amelanotic melanoma. Superficial BCC may mimic a lichenoid keratosis, Bowen’s disease, or other inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis and dermatitis. A larger lesion may mimic chronic infections such as mycetoma, or distant metastases from another primary carcinoma (breast or renal). Location and history can assist with teasing out the probable cause.

While diagnosis of this lesion can be made based on history and clinical appearance, this is best assisted with a biopsy, preferably a punch or incisional biopsy as chronic scarring and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may affect the pathologic diagnosis. Bacteria often colonize these large tumors and can lead to secondary infections. In this patient, maggots were noted in the skin.

While there are multiple modalities available for treating small tumors (e.g., topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, electrodessication and curettage, excision, Mohs), larger tumors are often handled differently. While some might consider radiation therapy in this case, typically Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice. Oral vismodegib, a smoothened inhibitor, has been marketed for locally advanced basal cell carcinoma and has been used as a primary or adjunctive therapy with Mohs in tumors of this size. One important factor determining the choice of treatment is whether the primary tumor has spread. In tumors who have been left untreated for a long time, it is reasonable to image the patient to evaluate for metastases.

We present this case as an example where Mohs provided immediate definitive treatment. This tumor was cleared in 1 stage, with 67 slides read to evaluate the entire peripheral and deep margin. The Mohs surgery was performed under local anesthesia with no additional sedatives and 3-0 nylon sutures were used to approximate the wound. A two month follow-up photo is shown showing an almost healed surgical wound with an acceptable cosmetic result.

Case and photo courtesy of: Andrew R. Styperek MD; Houston Methodist Hospital and DermSurgery Associates, Houston TX Arash Kimyai-Asadi MD; DermSurgery Associates, Houston TX Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD in Aventura, Fla. To submit your case for possible publication, send an e-mail to [email protected]. A 65 year old Caucasian male arrived with a decades-long history of a lesion on his back measuring 25 x 21 centimeters. In the last few years he has noticed discharge and an unpleasant smell. He denied any fatigue, shortness of breath, lymph node enlargement, or any other systemic symptoms. He had a history of hyperlipidemia and hypertension, which were controlled with daily oral medications. The patient was not taking aspirin or any other anticoagulant therapy.

Make the Diagnosis - August 2015

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Andrew R. Styperek, Houston Methodist Hospital and Dr. Leonard H. Goldberg of DermSurgery Associates, both in Houston. Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD in Aventura, Fla. To submit your case for possible publication, send an e-mail to [email protected]. A 27-year-old white female was admitted to the hospital with fever and shortness of breath. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of a long history of chronic skin itchiness and eczema, which had never resolved despite topical therapy. The patient denied any skeletal, tooth, or lung abnormalities. Her past medical history was significant for chronic cytomegalovirus infection of the right eye, resulting in extirpation of the orbit. She also had a history of eczema herpeticum. On physical exam, she had a patch of gauze over her right orbit, significant soft tissue loss of the nose, and numerous diffuse pink/red eczematous plaques over her arms, trunk, legs, and face. Of note, she also had multiple umbilicated and verrucous papules scattered over her body.

Make the Diagnosis - July 2015

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

Diagnosis: Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a rare connective tissue disorder in which excessive collagen is deposited in the skin and internal organs. This disease predominantly affects women (3-6:1) between the ages of 20 and 60 years with no apparent racial predominance. Effective treatment is critical, as scleroderma carries a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of up to 50% at 5 years in severe cases. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis is unknown, but three pathways are implicated, including immune deregulation, vascular abnormalities, and abnormal fibroblast activation.

Clinical presentation is variable because of the involvement of multiple organ systems. Common features include cutaneous pruritus, skin thickening, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, palpitations, nonproductive cough, and joint pain and swelling, as well as muscle pain and weakness. Laboratory findings may include elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased urea and creatinine levels, and elevated C-reactive protein. Antinuclear antibodies are usually elevated, especially Scl-70, antimitochondrial, and anticentromere antibodies. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be assessed upon diagnosis. A Doppler echocardiogram may detect cardiac abnormalities, and chest x-ray or high-resolution CT is used to assess for pulmonary fibrosis.

Despite the severity of the disease, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying agents for the treatment of scleroderma, and management often focuses on symptom relief. For example, patients with kidney involvement should be placed on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II inhibitor therapy, and patients with gastrointestinal tract involvement should use proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers to control reflux. Bosentan and pentoxifylline, which target vascular abnormalities, also may help improve skin fibrosis. Steroids show benefits in the early stages of the disease, but carry a risk of scleroderma renal crisis with doses greater than 15 mg of prednisone daily. Mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus have immunomodulatory and antifibrotic properties, which may be of benefit in this disease.

Cyclophosphamide is reserved for more severe cases. Other treatment modalities include rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, and autologous stem cell transplantation.

This case and photo were submitted by Charlotte E. LaSenna and Dr. Andrea Maderal of the University of Miami department of dermatology. Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD in Aventura, Fla. To submit your case for possible publication, send an e-mail to [email protected]. A 55-year-old woman with an 8-year history of previously diagnosed vitiligo presented with worsening pruritus and swelling of the hands and feet for several months. Her medical history included liver disease. Upon physical examination, she was ill-appearing, with notable salt-and-pepper diffuse depigmentation, as well as pitting edema of the bilateral hands and face. Laboratory studies showed a positive ANA >1:2,560 with a centromere pattern, negative Scl-70, and positive antimitochondrial antibody at 158.5. Renal function and urinalysis were normal. Liver function tests were abnormal with elevated alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin.

Make the Diagnosis - June 2015

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Kaposi's sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm with four principal clinical variants: HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, classic Kaposi's sarcoma, African endemic Kaposi's sarcoma, and immunosuppression-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. The etiologic agent in all clinical variants is human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma is primarily seen in men who have sex with men.

The four variants of Kaposi's sarcoma can have different clinical presentations. In HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma, patients may present with a single lesion or with symmetric widespread lesions. Clinically, the lesions can range from faint erythematous macules, to small violaceous papules, to large plaques or ulcerated nodules. The lesions are generally asymptomatic.

Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. Common body locations include the face (especially the nose), hard palate, trunk, penis, lower legs, and soles. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics. Histologically, atypical, angular vessels with an associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells appear in the upper dermis in macular lesions. Nodules and tumors reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions stain positive for human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8).

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma has greatly decreased. HAART is the most effective treatment method, and should be the initial therapy in most patients with mild to moderate disease.

However, some patients with HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma require further treatment - those who have well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads. Other treatments include local destruction (cryotherapy), topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin, or paclitaxel.

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Kaposi's sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm with four principal clinical variants: HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, classic Kaposi's sarcoma, African endemic Kaposi's sarcoma, and immunosuppression-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. The etiologic agent in all clinical variants is human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma is primarily seen in men who have sex with men.

The four variants of Kaposi's sarcoma can have different clinical presentations. In HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma, patients may present with a single lesion or with symmetric widespread lesions. Clinically, the lesions can range from faint erythematous macules, to small violaceous papules, to large plaques or ulcerated nodules. The lesions are generally asymptomatic.

Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. Common body locations include the face (especially the nose), hard palate, trunk, penis, lower legs, and soles. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics. Histologically, atypical, angular vessels with an associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells appear in the upper dermis in macular lesions. Nodules and tumors reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions stain positive for human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8).

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma has greatly decreased. HAART is the most effective treatment method, and should be the initial therapy in most patients with mild to moderate disease.

However, some patients with HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma require further treatment - those who have well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads. Other treatments include local destruction (cryotherapy), topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin, or paclitaxel.

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Kaposi's sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm with four principal clinical variants: HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, classic Kaposi's sarcoma, African endemic Kaposi's sarcoma, and immunosuppression-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. The etiologic agent in all clinical variants is human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma is primarily seen in men who have sex with men.

The four variants of Kaposi's sarcoma can have different clinical presentations. In HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma, patients may present with a single lesion or with symmetric widespread lesions. Clinically, the lesions can range from faint erythematous macules, to small violaceous papules, to large plaques or ulcerated nodules. The lesions are generally asymptomatic.

Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. Common body locations include the face (especially the nose), hard palate, trunk, penis, lower legs, and soles. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics. Histologically, atypical, angular vessels with an associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells appear in the upper dermis in macular lesions. Nodules and tumors reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions stain positive for human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8).

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma has greatly decreased. HAART is the most effective treatment method, and should be the initial therapy in most patients with mild to moderate disease.

However, some patients with HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma require further treatment - those who have well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads. Other treatments include local destruction (cryotherapy), topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin, or paclitaxel.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Ann Mazor Reed, Larkin Community Hospital, South Miami; and Dr. Donna Bilu Martin, Premier Dermatology, MD. Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD in Aventura, Fla. To submit your case for possible publication, send an e-mail to [email protected]. A 39-year-old white male presented with a 2-month history involving asymptomatic violaceous plaques on his leg and posterior neck. He had no significant past medical history. He had no oral or mucosal involvement, no lymphadenopathy, and denied any systemic symptoms.

Make the Diagnosis - May 2015

Diagnosis: Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a self-limited cutaneous disorder predominantly seen in women that affects children and adults. The cause is unknown. Inciting factors can include herpes zoster infection, sun exposure, medications, and trauma.

Several clinical variants exist. Localized GA is the most common form, often presenting in the first three decades of life as an asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaque with a firm border and central clearing localized to the wrists, ankles, and dorsal hands or feet. Generalized GA accounts for 15% of reported cases and presents in the fourth to seventh decades of life as multiple asymptomatic or pruritic skin-colored or erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities. Subcutaneous GA is more common in children and presents as multiple painless nodules on the scalp or extremities. Patch GA can be localized or generalized. Perforating GA presents as asymptomatic erythematous papules that evolve into yellow, umbilicated papules with a clear-to-white discharge.

Histopathologically, an interstitial or palisading pattern is seen with a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, degenerated collagen, and mucin deposition (visualized with alcian blue or colloidal iron stains). The interstitial pattern presents in the majority of cases.

Diagnosis of GA is predominantly clinically based. When the diagnosis is questionable or the presentation is atypical, biopsy is useful. Granuloma annulare is often self-limiting and resolves within 2 years, although recurrence is possible. First-line therapy for localized GA includes high-potency topical corticosteroids or intralesional corticosteroids. Other treatments include cryotherapy, phototherapy, and topical tacrolimus. For generalized GA, topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for select lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, light therapy, hydroxychloroquine, isotretinion, and dapsone also have been reported as treatments in the literature.

Diagnosis: Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a self-limited cutaneous disorder predominantly seen in women that affects children and adults. The cause is unknown. Inciting factors can include herpes zoster infection, sun exposure, medications, and trauma.

Several clinical variants exist. Localized GA is the most common form, often presenting in the first three decades of life as an asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaque with a firm border and central clearing localized to the wrists, ankles, and dorsal hands or feet. Generalized GA accounts for 15% of reported cases and presents in the fourth to seventh decades of life as multiple asymptomatic or pruritic skin-colored or erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities. Subcutaneous GA is more common in children and presents as multiple painless nodules on the scalp or extremities. Patch GA can be localized or generalized. Perforating GA presents as asymptomatic erythematous papules that evolve into yellow, umbilicated papules with a clear-to-white discharge.

Histopathologically, an interstitial or palisading pattern is seen with a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, degenerated collagen, and mucin deposition (visualized with alcian blue or colloidal iron stains). The interstitial pattern presents in the majority of cases.

Diagnosis of GA is predominantly clinically based. When the diagnosis is questionable or the presentation is atypical, biopsy is useful. Granuloma annulare is often self-limiting and resolves within 2 years, although recurrence is possible. First-line therapy for localized GA includes high-potency topical corticosteroids or intralesional corticosteroids. Other treatments include cryotherapy, phototherapy, and topical tacrolimus. For generalized GA, topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for select lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, light therapy, hydroxychloroquine, isotretinion, and dapsone also have been reported as treatments in the literature.

Diagnosis: Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a self-limited cutaneous disorder predominantly seen in women that affects children and adults. The cause is unknown. Inciting factors can include herpes zoster infection, sun exposure, medications, and trauma.

Several clinical variants exist. Localized GA is the most common form, often presenting in the first three decades of life as an asymptomatic, erythematous, annular plaque with a firm border and central clearing localized to the wrists, ankles, and dorsal hands or feet. Generalized GA accounts for 15% of reported cases and presents in the fourth to seventh decades of life as multiple asymptomatic or pruritic skin-colored or erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities. Subcutaneous GA is more common in children and presents as multiple painless nodules on the scalp or extremities. Patch GA can be localized or generalized. Perforating GA presents as asymptomatic erythematous papules that evolve into yellow, umbilicated papules with a clear-to-white discharge.

Histopathologically, an interstitial or palisading pattern is seen with a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, degenerated collagen, and mucin deposition (visualized with alcian blue or colloidal iron stains). The interstitial pattern presents in the majority of cases.

Diagnosis of GA is predominantly clinically based. When the diagnosis is questionable or the presentation is atypical, biopsy is useful. Granuloma annulare is often self-limiting and resolves within 2 years, although recurrence is possible. First-line therapy for localized GA includes high-potency topical corticosteroids or intralesional corticosteroids. Other treatments include cryotherapy, phototherapy, and topical tacrolimus. For generalized GA, topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be used for select lesions. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, light therapy, hydroxychloroquine, isotretinion, and dapsone also have been reported as treatments in the literature.

This case and photo were submitted by Orli Stern of Ross University and Dr. Donna Bilu Martin of Premier Dermatology, MD. A 60-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented with a 3-month history of asymptomatic, erythematous, firm, annular plaques on her bilateral proximal upper extremities and dorsal hands. The lesions have not been treated in the past.

Make the Diagnosis - April 2015

Diagnosis: Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a common inflammatory condition involving the skin, nails, mucous membranes, and hair follicles. It has no racial predilection, and often affects men and women aged 20-60 years. It is less common in children, who account for only 4% of cases. The lesions are often atypical.

Clinically, patients often present with erythematous to violaceous small, flat-topped, polygonal papules that may coalesce into plaques. Lesions are generally pruritic, and may be tender or painful. Older lesions may be hyperpigmented. White streaks known as Wickham striae can cross the surface of lesions. These striae also can be present orally, such as in the patient described here. Oral lesions also may be atrophic or erosive.

Common body locations with involvement are the inner wrists, legs, torso, or genitals (glans penis). The face is rarely involved. Nail changes, such as longitudinal ridging and splitting, onycholysis, red lunula, yellow nail syndrome, and pterygium formation, can occur.

Lichen planus often spontaneously resolves on its own, with 2/3 of patients resolving in a year. Mucous membrane disease tends to be more chronic. The etiology of lichen planus is unknown. It may have an autoimmune mechanism in which T cells induce keratinocytes to undergo apoptosis. Between 4% and 60% of lichen planus patients also have hepatitis C infections. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous lesions include lichenoid drug eruption, guttate psoriasis, syphilis, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Oral lesions may resemble candidiasis, leukoplakia, malignancies, and bullous disease.

Topical and intralesional steroids are often effective for localized disease. Systemic corticosteroids can be useful when lesions are widespread. Phototherapy, isotretinoin, acitretin, hydroxychloroquine, and oral immunosuppressive agents (such as cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil) all have been described in the treatment of lichen planus.

Diagnosis: Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a common inflammatory condition involving the skin, nails, mucous membranes, and hair follicles. It has no racial predilection, and often affects men and women aged 20-60 years. It is less common in children, who account for only 4% of cases. The lesions are often atypical.

Clinically, patients often present with erythematous to violaceous small, flat-topped, polygonal papules that may coalesce into plaques. Lesions are generally pruritic, and may be tender or painful. Older lesions may be hyperpigmented. White streaks known as Wickham striae can cross the surface of lesions. These striae also can be present orally, such as in the patient described here. Oral lesions also may be atrophic or erosive.

Common body locations with involvement are the inner wrists, legs, torso, or genitals (glans penis). The face is rarely involved. Nail changes, such as longitudinal ridging and splitting, onycholysis, red lunula, yellow nail syndrome, and pterygium formation, can occur.

Lichen planus often spontaneously resolves on its own, with 2/3 of patients resolving in a year. Mucous membrane disease tends to be more chronic. The etiology of lichen planus is unknown. It may have an autoimmune mechanism in which T cells induce keratinocytes to undergo apoptosis. Between 4% and 60% of lichen planus patients also have hepatitis C infections. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous lesions include lichenoid drug eruption, guttate psoriasis, syphilis, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Oral lesions may resemble candidiasis, leukoplakia, malignancies, and bullous disease.

Topical and intralesional steroids are often effective for localized disease. Systemic corticosteroids can be useful when lesions are widespread. Phototherapy, isotretinoin, acitretin, hydroxychloroquine, and oral immunosuppressive agents (such as cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil) all have been described in the treatment of lichen planus.

Diagnosis: Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a common inflammatory condition involving the skin, nails, mucous membranes, and hair follicles. It has no racial predilection, and often affects men and women aged 20-60 years. It is less common in children, who account for only 4% of cases. The lesions are often atypical.

Clinically, patients often present with erythematous to violaceous small, flat-topped, polygonal papules that may coalesce into plaques. Lesions are generally pruritic, and may be tender or painful. Older lesions may be hyperpigmented. White streaks known as Wickham striae can cross the surface of lesions. These striae also can be present orally, such as in the patient described here. Oral lesions also may be atrophic or erosive.

Common body locations with involvement are the inner wrists, legs, torso, or genitals (glans penis). The face is rarely involved. Nail changes, such as longitudinal ridging and splitting, onycholysis, red lunula, yellow nail syndrome, and pterygium formation, can occur.

Lichen planus often spontaneously resolves on its own, with 2/3 of patients resolving in a year. Mucous membrane disease tends to be more chronic. The etiology of lichen planus is unknown. It may have an autoimmune mechanism in which T cells induce keratinocytes to undergo apoptosis. Between 4% and 60% of lichen planus patients also have hepatitis C infections. The differential diagnosis for cutaneous lesions include lichenoid drug eruption, guttate psoriasis, syphilis, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. Oral lesions may resemble candidiasis, leukoplakia, malignancies, and bullous disease.

Topical and intralesional steroids are often effective for localized disease. Systemic corticosteroids can be useful when lesions are widespread. Phototherapy, isotretinoin, acitretin, hydroxychloroquine, and oral immunosuppressive agents (such as cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil) all have been described in the treatment of lichen planus.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Damon McClain, a dermatologist in Camp Lejeune, N.C. A 34-year-old male presented with a 1-month history of an itchy rash on his penis and feet. Upon physical examination, these lesions were seen orally. Blood work, including hepatitis serologies, was negative. His skin lesions improved with topical steroids.

Make the Diagnosis - March 2015

Diagnosis: Bleomycin-induced flagellate hyperpigmentation

Bleomycin is an antineoplastic agent. Most reported side effects involve the lung and skin since these organs have lower concentrations of the enzyme that detoxifies bleomycin. Other dermatologic side effects of bleomycin include Raynaud's phenomenon, hyperkeratosis, nailbed changes, and peeling of the skin on the palmar and plantar surfaces.

Flagellate erythema has been described in relation to bleomycin treatment along with other reported associations with peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative), docetaxel, dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still's disease, and shiitake mushroom dermatitis. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anytime from 1 day to several months after exposure to the offending agent. Patients typically present with history of itching followed by the appearance of red linear streaks, which are most commonly found on the trunk. Over time, the erythema will resolve to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

The exact cause is unknown, but it is thought that scratching causes vasodilation with bleomycin accumulating in the skin. Diagnosis is made by physical examination of the characteristic appearance of the rash along with the history of chemotherapy. A skin biopsy may be performed. In most cases, the rash resolves spontaneously within 6-8 months. Severe rashes may warrant discontinuation of bleomycin. Using antihistamines and topical and oral corticosteroids in conjunction with bleomycin may reduce the incidence of flagellate erythema/hyperpigmentation.

Diagnosis: Bleomycin-induced flagellate hyperpigmentation

Bleomycin is an antineoplastic agent. Most reported side effects involve the lung and skin since these organs have lower concentrations of the enzyme that detoxifies bleomycin. Other dermatologic side effects of bleomycin include Raynaud's phenomenon, hyperkeratosis, nailbed changes, and peeling of the skin on the palmar and plantar surfaces.

Flagellate erythema has been described in relation to bleomycin treatment along with other reported associations with peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative), docetaxel, dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still's disease, and shiitake mushroom dermatitis. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anytime from 1 day to several months after exposure to the offending agent. Patients typically present with history of itching followed by the appearance of red linear streaks, which are most commonly found on the trunk. Over time, the erythema will resolve to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

The exact cause is unknown, but it is thought that scratching causes vasodilation with bleomycin accumulating in the skin. Diagnosis is made by physical examination of the characteristic appearance of the rash along with the history of chemotherapy. A skin biopsy may be performed. In most cases, the rash resolves spontaneously within 6-8 months. Severe rashes may warrant discontinuation of bleomycin. Using antihistamines and topical and oral corticosteroids in conjunction with bleomycin may reduce the incidence of flagellate erythema/hyperpigmentation.

Diagnosis: Bleomycin-induced flagellate hyperpigmentation

Bleomycin is an antineoplastic agent. Most reported side effects involve the lung and skin since these organs have lower concentrations of the enzyme that detoxifies bleomycin. Other dermatologic side effects of bleomycin include Raynaud's phenomenon, hyperkeratosis, nailbed changes, and peeling of the skin on the palmar and plantar surfaces.

Flagellate erythema has been described in relation to bleomycin treatment along with other reported associations with peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative), docetaxel, dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still's disease, and shiitake mushroom dermatitis. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anytime from 1 day to several months after exposure to the offending agent. Patients typically present with history of itching followed by the appearance of red linear streaks, which are most commonly found on the trunk. Over time, the erythema will resolve to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

The exact cause is unknown, but it is thought that scratching causes vasodilation with bleomycin accumulating in the skin. Diagnosis is made by physical examination of the characteristic appearance of the rash along with the history of chemotherapy. A skin biopsy may be performed. In most cases, the rash resolves spontaneously within 6-8 months. Severe rashes may warrant discontinuation of bleomycin. Using antihistamines and topical and oral corticosteroids in conjunction with bleomycin may reduce the incidence of flagellate erythema/hyperpigmentation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Damon McClain, a dermatologist in Camp Lejeune, N.C., and by Parteek Singla. A 26-year-old male presented with asymptomatic hyperpigmented streaks on his back. He was receiving chemotherapy for testicular cancer. He received dexamethasone with his first chemotherapy treatment and had no cutaneous eruption at that time. He was not given a steroid with his second dose of chemotherapy. The lesions began an hour after that dose. Initially, the lesions were red and pruritic, and then they turned brown. The patient had no nailfold changes on examination. He had no other medical problems and reported that he had not eaten any unusual foods.