User login

Make the Diagnosis - February 2018

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is an autosomal dominant genetic neurocutaneous disorder. There are eight subtypes of NF: NF type 1-7 and NF-NOS, or not otherwise specified. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), or von Recklinghausen disease, is the most common and is a result of a genetic mutation on chromosome 17 that is involved in producing a protein called neurofibromin. Neurofibromin is a tumor suppressor that suppresses products of ras proto-oncogenes. When it is absent, tumor progression may occur.

Von Recklinghausen NF-1 appears in childhood, usually by age 10. Diagnosis requires the presence of at least 2 of the following 7 criteria:

•Six or more café au lait macules measuring 5 mm in diameter or greater in prepubertal children and measuring greater than 15 mm in postpubertal children.

•Axillary or inguinal freckling (Crowe’s sign).

•Two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma.

•Optic nerve glioma.

•Two or more iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules).

•Sphenoid dysplasia or long-bone abnormalities, such as pseudoarthrosis.

•First degree relative with NF-1.

The diagnosis is usually made via physical examination. Supportive tests include an ophthalmologic exam to detect Lisch nodules and cataracts. A neurological evaluation is essential. Imaging examinations can identify bony abnormalities and tumor growths. Also, genetic testing to identify genetic mutations can be performed.

Neurofibromatosis type 2 results from a genetic mutation located on chromosome 22 that produces a protein called merlin and occurs in adolescence. Acoustic or vestibular neuromas may occur; these interfere with the transmission of sound and maintaining balance. Symptoms include gradual hearing loss, tinnitus, poor balance, and headaches. Radiosurgery and cochlear implants have shown a role for symptomatic treatment in patients with NF-2.

This case and photo were submitted by Parteek Singla, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University and Barnes Jewish Hospital, both in St. Louis, and by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is an autosomal dominant genetic neurocutaneous disorder. There are eight subtypes of NF: NF type 1-7 and NF-NOS, or not otherwise specified. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), or von Recklinghausen disease, is the most common and is a result of a genetic mutation on chromosome 17 that is involved in producing a protein called neurofibromin. Neurofibromin is a tumor suppressor that suppresses products of ras proto-oncogenes. When it is absent, tumor progression may occur.

Von Recklinghausen NF-1 appears in childhood, usually by age 10. Diagnosis requires the presence of at least 2 of the following 7 criteria:

•Six or more café au lait macules measuring 5 mm in diameter or greater in prepubertal children and measuring greater than 15 mm in postpubertal children.

•Axillary or inguinal freckling (Crowe’s sign).

•Two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma.

•Optic nerve glioma.

•Two or more iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules).

•Sphenoid dysplasia or long-bone abnormalities, such as pseudoarthrosis.

•First degree relative with NF-1.

The diagnosis is usually made via physical examination. Supportive tests include an ophthalmologic exam to detect Lisch nodules and cataracts. A neurological evaluation is essential. Imaging examinations can identify bony abnormalities and tumor growths. Also, genetic testing to identify genetic mutations can be performed.

Neurofibromatosis type 2 results from a genetic mutation located on chromosome 22 that produces a protein called merlin and occurs in adolescence. Acoustic or vestibular neuromas may occur; these interfere with the transmission of sound and maintaining balance. Symptoms include gradual hearing loss, tinnitus, poor balance, and headaches. Radiosurgery and cochlear implants have shown a role for symptomatic treatment in patients with NF-2.

This case and photo were submitted by Parteek Singla, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University and Barnes Jewish Hospital, both in St. Louis, and by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is an autosomal dominant genetic neurocutaneous disorder. There are eight subtypes of NF: NF type 1-7 and NF-NOS, or not otherwise specified. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), or von Recklinghausen disease, is the most common and is a result of a genetic mutation on chromosome 17 that is involved in producing a protein called neurofibromin. Neurofibromin is a tumor suppressor that suppresses products of ras proto-oncogenes. When it is absent, tumor progression may occur.

Von Recklinghausen NF-1 appears in childhood, usually by age 10. Diagnosis requires the presence of at least 2 of the following 7 criteria:

•Six or more café au lait macules measuring 5 mm in diameter or greater in prepubertal children and measuring greater than 15 mm in postpubertal children.

•Axillary or inguinal freckling (Crowe’s sign).

•Two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma.

•Optic nerve glioma.

•Two or more iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules).

•Sphenoid dysplasia or long-bone abnormalities, such as pseudoarthrosis.

•First degree relative with NF-1.

The diagnosis is usually made via physical examination. Supportive tests include an ophthalmologic exam to detect Lisch nodules and cataracts. A neurological evaluation is essential. Imaging examinations can identify bony abnormalities and tumor growths. Also, genetic testing to identify genetic mutations can be performed.

Neurofibromatosis type 2 results from a genetic mutation located on chromosome 22 that produces a protein called merlin and occurs in adolescence. Acoustic or vestibular neuromas may occur; these interfere with the transmission of sound and maintaining balance. Symptoms include gradual hearing loss, tinnitus, poor balance, and headaches. Radiosurgery and cochlear implants have shown a role for symptomatic treatment in patients with NF-2.

This case and photo were submitted by Parteek Singla, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University and Barnes Jewish Hospital, both in St. Louis, and by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Make the diagnosis - January 2018

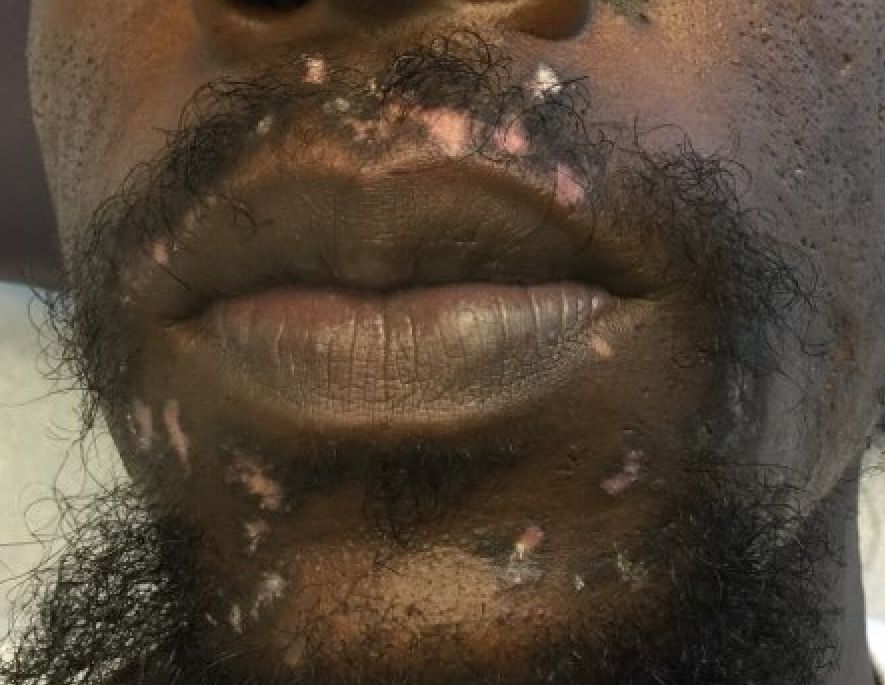

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus can be classified into acute, subacute, and chronic lesions. Chronic cutaneous lupus, or discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). They are one of the more common skin presentations seen in lupus. Young adults are typically affected, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1. Progression from DLE to SLE is uncommon. However, patients with SLE will frequently develop discoid lesions.

The differential diagnosis includes: subacute cutaneous lupus, lichen planus, seborrheic dermatitis, Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, polymorphous light eruption, rosacea, granuloma faciale, and sarcoidosis. Histology of DLE may reveal hyperkeratosis, a thin epidermis with effacement of the rete ridges, a lichenoid and vacuolar interface dermatitis, and follicular plugging. Damaged keratinocytes called colloid bodies may be present. Increased mucin and thickening of the basement membrane are commonly seen. Active lesions will exhibit more of an inflammatory infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in more than 75% of cases.

This case and the photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus can be classified into acute, subacute, and chronic lesions. Chronic cutaneous lupus, or discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). They are one of the more common skin presentations seen in lupus. Young adults are typically affected, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1. Progression from DLE to SLE is uncommon. However, patients with SLE will frequently develop discoid lesions.

The differential diagnosis includes: subacute cutaneous lupus, lichen planus, seborrheic dermatitis, Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, polymorphous light eruption, rosacea, granuloma faciale, and sarcoidosis. Histology of DLE may reveal hyperkeratosis, a thin epidermis with effacement of the rete ridges, a lichenoid and vacuolar interface dermatitis, and follicular plugging. Damaged keratinocytes called colloid bodies may be present. Increased mucin and thickening of the basement membrane are commonly seen. Active lesions will exhibit more of an inflammatory infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in more than 75% of cases.

This case and the photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus can be classified into acute, subacute, and chronic lesions. Chronic cutaneous lupus, or discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). They are one of the more common skin presentations seen in lupus. Young adults are typically affected, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1. Progression from DLE to SLE is uncommon. However, patients with SLE will frequently develop discoid lesions.

The differential diagnosis includes: subacute cutaneous lupus, lichen planus, seborrheic dermatitis, Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, polymorphous light eruption, rosacea, granuloma faciale, and sarcoidosis. Histology of DLE may reveal hyperkeratosis, a thin epidermis with effacement of the rete ridges, a lichenoid and vacuolar interface dermatitis, and follicular plugging. Damaged keratinocytes called colloid bodies may be present. Increased mucin and thickening of the basement membrane are commonly seen. Active lesions will exhibit more of an inflammatory infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in more than 75% of cases.

This case and the photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 32-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented with a 2-year history of asymptomatic perioral lesions. On physical examination, multiple erythematous to hypopigmented atrophic plaques with peripheral hyperpigmentation were present.

Make The Diagnosis - November 2017

Angiosarcoma is also known as malignant hemangioendothelioma, hemangiosarcoma, and lymphangiosarcoma. It is an uncommon, high-grade malignant vascular neoplasm of the inner lining of blood vessels. Unlike most sarcomas, it occurs more superficially, most often on the head and neck (particularly on the scalp). This neoplasm occurs twice as often in males as it does in females. Angiosarcomas can occur in the breast after radiation therapy, as well as in the liver and spleen, but 60% are cutaneous.

Clinical exam findings may show a violaceous lesion similar to a bruise on the head and neck that does not heal or bleeds when scratched; this is of particular concern when the lesion has appeared in an area of prior radiation therapy. Deeper tumors may be felt as a soft nodule. Ulceration may be present. Biopsy of the lesion will show hyperchromatic, pleomorphic tumor cells that dissect between collagen bundles with endothelial cells that are multilayered along with hemorrhage. Malignant cells stain positive for CD31, CD34, ERG, and FLI1.

For localized disease, surgery with wide local excision plus adjuvant radiation therapy can be used. For metastatic disease, chemotherapy is the treatment modality of choice. Unfortunately, prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of about 35% in nonmetastatic angiosarcoma cases. The majority of recurrences – approximately 75% – occur within 24 months of local treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Parteek Singla, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University and at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, both in St. Louis, and by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Angiosarcoma is also known as malignant hemangioendothelioma, hemangiosarcoma, and lymphangiosarcoma. It is an uncommon, high-grade malignant vascular neoplasm of the inner lining of blood vessels. Unlike most sarcomas, it occurs more superficially, most often on the head and neck (particularly on the scalp). This neoplasm occurs twice as often in males as it does in females. Angiosarcomas can occur in the breast after radiation therapy, as well as in the liver and spleen, but 60% are cutaneous.

Clinical exam findings may show a violaceous lesion similar to a bruise on the head and neck that does not heal or bleeds when scratched; this is of particular concern when the lesion has appeared in an area of prior radiation therapy. Deeper tumors may be felt as a soft nodule. Ulceration may be present. Biopsy of the lesion will show hyperchromatic, pleomorphic tumor cells that dissect between collagen bundles with endothelial cells that are multilayered along with hemorrhage. Malignant cells stain positive for CD31, CD34, ERG, and FLI1.

For localized disease, surgery with wide local excision plus adjuvant radiation therapy can be used. For metastatic disease, chemotherapy is the treatment modality of choice. Unfortunately, prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of about 35% in nonmetastatic angiosarcoma cases. The majority of recurrences – approximately 75% – occur within 24 months of local treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Parteek Singla, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University and at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, both in St. Louis, and by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Angiosarcoma is also known as malignant hemangioendothelioma, hemangiosarcoma, and lymphangiosarcoma. It is an uncommon, high-grade malignant vascular neoplasm of the inner lining of blood vessels. Unlike most sarcomas, it occurs more superficially, most often on the head and neck (particularly on the scalp). This neoplasm occurs twice as often in males as it does in females. Angiosarcomas can occur in the breast after radiation therapy, as well as in the liver and spleen, but 60% are cutaneous.

Clinical exam findings may show a violaceous lesion similar to a bruise on the head and neck that does not heal or bleeds when scratched; this is of particular concern when the lesion has appeared in an area of prior radiation therapy. Deeper tumors may be felt as a soft nodule. Ulceration may be present. Biopsy of the lesion will show hyperchromatic, pleomorphic tumor cells that dissect between collagen bundles with endothelial cells that are multilayered along with hemorrhage. Malignant cells stain positive for CD31, CD34, ERG, and FLI1.

For localized disease, surgery with wide local excision plus adjuvant radiation therapy can be used. For metastatic disease, chemotherapy is the treatment modality of choice. Unfortunately, prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of about 35% in nonmetastatic angiosarcoma cases. The majority of recurrences – approximately 75% – occur within 24 months of local treatment.

This case and photo were submitted by Parteek Singla, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University and at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, both in St. Louis, and by Susannah McClain, MD, of Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 62-year-old healthy man presented with a skin lesion located on the left scalp. The lesion was swollen and painful and had been present for 4 months. This lesion had not been treated in the past.

Make the Diagnosis - October 2017

Palmoplantar keratoderma

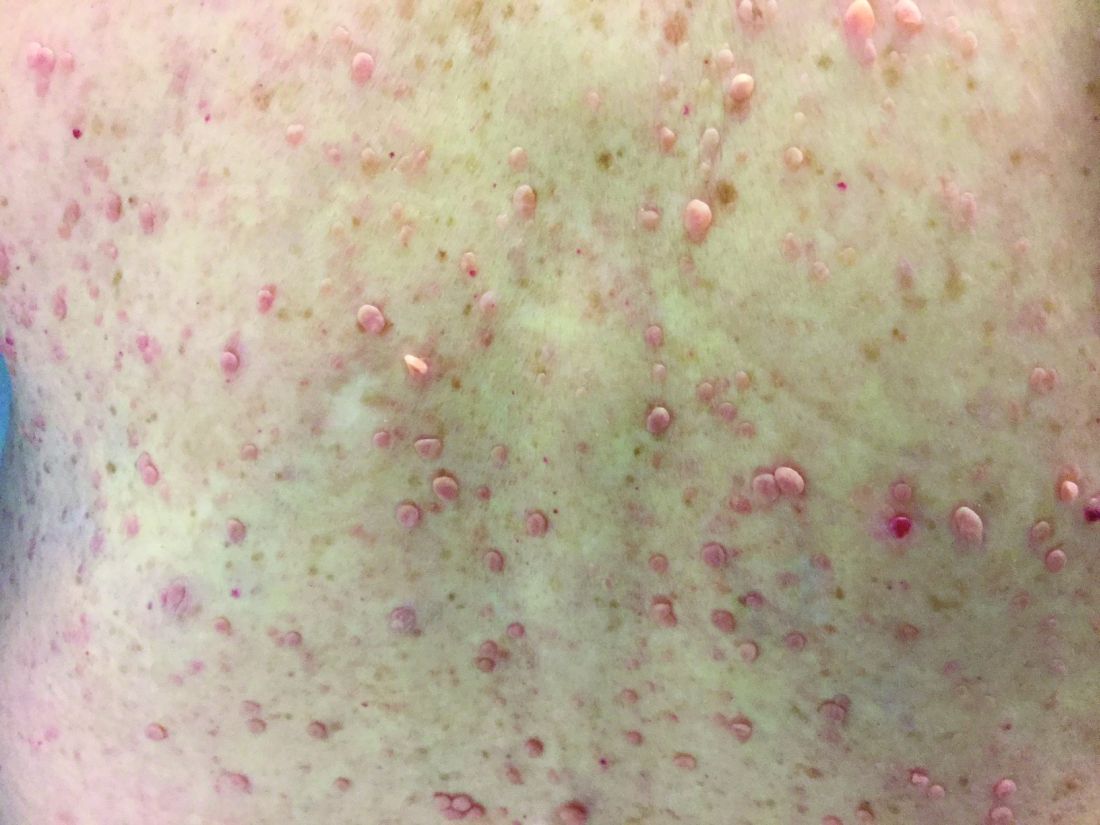

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is made of a group of benign disorders that cause thickening of the palms and soles. It is generally divided into three categories: diffuse PPK, with involvement of the whole palmoplantar surface; focal and striate PPK, usually located mainly on pressure points; and punctate PPK, featuring multiple small hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, or spicules. This patient’s lesions are most consistent with punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (PPPK).

PPPK is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, although acquired cases can be seen. It is also called Buschke-Fischer-Brauer syndrome, or keratodermia palmoplantaris papulosa. The condition affects men and women equally. Lesions usually appear during adolescence or after, unlike other forms of keratoderma, which may occur during childhood. While any race may be affected, in those of African descent, lesions are more common in the palmar creases. The condition is likely due to an aberration in proteins involved in keratin filament assembly. A mutation in the AAGAB gene can be at fault. PPPK can be associated with Darier’s disease and Cowden disease. Familial PPPK may be associated with Hodgkin disease, squamous cell carcinoma, kidney, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer.

Upon physical exam, multiple keratotic, punctate papules are present on the palms and soles, which may appear clear or more opaque. They may also have a verrucous appearance. Some lesions may have a central keratotic core and appear more comedonal. Most often, lesions are nontransgradient, meaning they only involve the palms and soles. Sometimes lesions may extend to the top of the hands and feet as well, which is called transgradient. Lesions are typically asymptomatic, although larger lesions can become painful with friction. Other types of PPPKs include filiform keratoderma and marginal keratoderma.

Histologic evaluation reveals columns of hyperkeratosis with an increased granular layer. There is no dermal inflammation. Clinically, the differential diagnosis is limited. Verruca vulgaris will reveal bleeding points upon paring with a blade. In spiny keratoderma, also called punctate porokeratosis of the palms and soles, lesions protrude more and resemble “music box spines.” Histologically, columnar parakeratosis is seen. Pitted keratolysis have reduced stratum corneum and a distinct clinical appearance.

If treatment is desired, emollients, keratolytics such as topical retinoids, salicylic acid, lactic acid, and urea may be used. Oral retinoids may be useful in symptomatic patients. Surgery and CO2 laser may be an option for resistant lesions.

This case and photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Palmoplantar keratoderma

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is made of a group of benign disorders that cause thickening of the palms and soles. It is generally divided into three categories: diffuse PPK, with involvement of the whole palmoplantar surface; focal and striate PPK, usually located mainly on pressure points; and punctate PPK, featuring multiple small hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, or spicules. This patient’s lesions are most consistent with punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (PPPK).

PPPK is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, although acquired cases can be seen. It is also called Buschke-Fischer-Brauer syndrome, or keratodermia palmoplantaris papulosa. The condition affects men and women equally. Lesions usually appear during adolescence or after, unlike other forms of keratoderma, which may occur during childhood. While any race may be affected, in those of African descent, lesions are more common in the palmar creases. The condition is likely due to an aberration in proteins involved in keratin filament assembly. A mutation in the AAGAB gene can be at fault. PPPK can be associated with Darier’s disease and Cowden disease. Familial PPPK may be associated with Hodgkin disease, squamous cell carcinoma, kidney, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer.

Upon physical exam, multiple keratotic, punctate papules are present on the palms and soles, which may appear clear or more opaque. They may also have a verrucous appearance. Some lesions may have a central keratotic core and appear more comedonal. Most often, lesions are nontransgradient, meaning they only involve the palms and soles. Sometimes lesions may extend to the top of the hands and feet as well, which is called transgradient. Lesions are typically asymptomatic, although larger lesions can become painful with friction. Other types of PPPKs include filiform keratoderma and marginal keratoderma.

Histologic evaluation reveals columns of hyperkeratosis with an increased granular layer. There is no dermal inflammation. Clinically, the differential diagnosis is limited. Verruca vulgaris will reveal bleeding points upon paring with a blade. In spiny keratoderma, also called punctate porokeratosis of the palms and soles, lesions protrude more and resemble “music box spines.” Histologically, columnar parakeratosis is seen. Pitted keratolysis have reduced stratum corneum and a distinct clinical appearance.

If treatment is desired, emollients, keratolytics such as topical retinoids, salicylic acid, lactic acid, and urea may be used. Oral retinoids may be useful in symptomatic patients. Surgery and CO2 laser may be an option for resistant lesions.

This case and photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Palmoplantar keratoderma

Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) is made of a group of benign disorders that cause thickening of the palms and soles. It is generally divided into three categories: diffuse PPK, with involvement of the whole palmoplantar surface; focal and striate PPK, usually located mainly on pressure points; and punctate PPK, featuring multiple small hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, or spicules. This patient’s lesions are most consistent with punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (PPPK).

PPPK is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, although acquired cases can be seen. It is also called Buschke-Fischer-Brauer syndrome, or keratodermia palmoplantaris papulosa. The condition affects men and women equally. Lesions usually appear during adolescence or after, unlike other forms of keratoderma, which may occur during childhood. While any race may be affected, in those of African descent, lesions are more common in the palmar creases. The condition is likely due to an aberration in proteins involved in keratin filament assembly. A mutation in the AAGAB gene can be at fault. PPPK can be associated with Darier’s disease and Cowden disease. Familial PPPK may be associated with Hodgkin disease, squamous cell carcinoma, kidney, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer.

Upon physical exam, multiple keratotic, punctate papules are present on the palms and soles, which may appear clear or more opaque. They may also have a verrucous appearance. Some lesions may have a central keratotic core and appear more comedonal. Most often, lesions are nontransgradient, meaning they only involve the palms and soles. Sometimes lesions may extend to the top of the hands and feet as well, which is called transgradient. Lesions are typically asymptomatic, although larger lesions can become painful with friction. Other types of PPPKs include filiform keratoderma and marginal keratoderma.

Histologic evaluation reveals columns of hyperkeratosis with an increased granular layer. There is no dermal inflammation. Clinically, the differential diagnosis is limited. Verruca vulgaris will reveal bleeding points upon paring with a blade. In spiny keratoderma, also called punctate porokeratosis of the palms and soles, lesions protrude more and resemble “music box spines.” Histologically, columnar parakeratosis is seen. Pitted keratolysis have reduced stratum corneum and a distinct clinical appearance.

If treatment is desired, emollients, keratolytics such as topical retinoids, salicylic acid, lactic acid, and urea may be used. Oral retinoids may be useful in symptomatic patients. Surgery and CO2 laser may be an option for resistant lesions.

This case and photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Make the Diagnosis - September 2017

Nevus sebaceous (NS)

Nevus sebaceous (NS) is a congenital hamartoma of the sebaceous glands that was first described by Josef Jadassohn, MD, in 1895. The lesion is caused by a post-zygotic somatic mutation in the KRAS or HRAS genes, which can lead to variable clinical mosaicism. In addition, hamartomatous presentations within different cell lines may occur if the pluripotent stem cells are affected. The lesion is present in about 0.3% of newborns and is equally represented among gender, race, and geography.

NS has three stages of presentation. At birth or early childhood, NS most commonly presents as a solitary, well-circumscribed, smooth, yellow to tan-brown plaque with associated hair loss in the vertex of the scalp, although it may less commonly present on the face, neck, or trunk. The lesion may be raised at birth. During puberty, hormonal variations alter the form of the lesion and the NS can become more verrucous and nodular. The clinical differential diagnosis for NS includes seborrheic keratosis, congenital nevus, and epidermal nevus.

About 24% of patients may develop appendageal tumors arising from the primary lesion. The majority of these tumors are benign, with trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum as the most common secondary growths. The most common malignant tumor that arises is basal cell carcinoma. Deletion of the patched gene has been implicated in the development of basal cell carcinoma within NS lesions. Many other tumors arising from NS lesions have been reported in the literature, including keratoacanthoma, apocrine cystadenoma, leiomyoma, and sebaceous cell carcinoma. More rarely, development of an eccrine or apocrine carcinoma within the NS can lead to widespread metastasis and death.

Because there is a chance of secondary tumor development, the decision to surgically excise the lesion or closely follow for transformation is controversial. Advocates of surgical excision reason that adolescence is the optimal time for removal because it is before pubertal enlargement and the patient would be able to tolerate anesthesia. If the patient chooses to clinically monitor the lesion, he or she should be informed that a full-thickness excision with wide margins will have to be performed if malignant transformation occurs.

A biopsy was performed of the erythematous papule that revealed an atypical sebaceous neoplasm with features of a sebaceoma. The patient had subsequent excision of the entire lesion that was read by a different dermatopathologist and revealed nevus sebaceous with syringocystadenoma papilliferum, no residual atypical sebaceous neoplasm, and clear margins.

This case and photo were submitted by Victoria Billero, University of Miami, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Nevus sebaceous (NS)

Nevus sebaceous (NS) is a congenital hamartoma of the sebaceous glands that was first described by Josef Jadassohn, MD, in 1895. The lesion is caused by a post-zygotic somatic mutation in the KRAS or HRAS genes, which can lead to variable clinical mosaicism. In addition, hamartomatous presentations within different cell lines may occur if the pluripotent stem cells are affected. The lesion is present in about 0.3% of newborns and is equally represented among gender, race, and geography.

NS has three stages of presentation. At birth or early childhood, NS most commonly presents as a solitary, well-circumscribed, smooth, yellow to tan-brown plaque with associated hair loss in the vertex of the scalp, although it may less commonly present on the face, neck, or trunk. The lesion may be raised at birth. During puberty, hormonal variations alter the form of the lesion and the NS can become more verrucous and nodular. The clinical differential diagnosis for NS includes seborrheic keratosis, congenital nevus, and epidermal nevus.

About 24% of patients may develop appendageal tumors arising from the primary lesion. The majority of these tumors are benign, with trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum as the most common secondary growths. The most common malignant tumor that arises is basal cell carcinoma. Deletion of the patched gene has been implicated in the development of basal cell carcinoma within NS lesions. Many other tumors arising from NS lesions have been reported in the literature, including keratoacanthoma, apocrine cystadenoma, leiomyoma, and sebaceous cell carcinoma. More rarely, development of an eccrine or apocrine carcinoma within the NS can lead to widespread metastasis and death.

Because there is a chance of secondary tumor development, the decision to surgically excise the lesion or closely follow for transformation is controversial. Advocates of surgical excision reason that adolescence is the optimal time for removal because it is before pubertal enlargement and the patient would be able to tolerate anesthesia. If the patient chooses to clinically monitor the lesion, he or she should be informed that a full-thickness excision with wide margins will have to be performed if malignant transformation occurs.

A biopsy was performed of the erythematous papule that revealed an atypical sebaceous neoplasm with features of a sebaceoma. The patient had subsequent excision of the entire lesion that was read by a different dermatopathologist and revealed nevus sebaceous with syringocystadenoma papilliferum, no residual atypical sebaceous neoplasm, and clear margins.

This case and photo were submitted by Victoria Billero, University of Miami, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Nevus sebaceous (NS)

Nevus sebaceous (NS) is a congenital hamartoma of the sebaceous glands that was first described by Josef Jadassohn, MD, in 1895. The lesion is caused by a post-zygotic somatic mutation in the KRAS or HRAS genes, which can lead to variable clinical mosaicism. In addition, hamartomatous presentations within different cell lines may occur if the pluripotent stem cells are affected. The lesion is present in about 0.3% of newborns and is equally represented among gender, race, and geography.

NS has three stages of presentation. At birth or early childhood, NS most commonly presents as a solitary, well-circumscribed, smooth, yellow to tan-brown plaque with associated hair loss in the vertex of the scalp, although it may less commonly present on the face, neck, or trunk. The lesion may be raised at birth. During puberty, hormonal variations alter the form of the lesion and the NS can become more verrucous and nodular. The clinical differential diagnosis for NS includes seborrheic keratosis, congenital nevus, and epidermal nevus.

About 24% of patients may develop appendageal tumors arising from the primary lesion. The majority of these tumors are benign, with trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum as the most common secondary growths. The most common malignant tumor that arises is basal cell carcinoma. Deletion of the patched gene has been implicated in the development of basal cell carcinoma within NS lesions. Many other tumors arising from NS lesions have been reported in the literature, including keratoacanthoma, apocrine cystadenoma, leiomyoma, and sebaceous cell carcinoma. More rarely, development of an eccrine or apocrine carcinoma within the NS can lead to widespread metastasis and death.

Because there is a chance of secondary tumor development, the decision to surgically excise the lesion or closely follow for transformation is controversial. Advocates of surgical excision reason that adolescence is the optimal time for removal because it is before pubertal enlargement and the patient would be able to tolerate anesthesia. If the patient chooses to clinically monitor the lesion, he or she should be informed that a full-thickness excision with wide margins will have to be performed if malignant transformation occurs.

A biopsy was performed of the erythematous papule that revealed an atypical sebaceous neoplasm with features of a sebaceoma. The patient had subsequent excision of the entire lesion that was read by a different dermatopathologist and revealed nevus sebaceous with syringocystadenoma papilliferum, no residual atypical sebaceous neoplasm, and clear margins.

This case and photo were submitted by Victoria Billero, University of Miami, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 30-year-old woman presented for a routine full body skin exam. Upon exam, was found to have a 4 cm x 1.7 cm smooth, yellow plaque on the left scalp with a prominent 5 mm erythematous papule. The plaque had been present since childhood. The papule developed over the past few months.

Make the Diagnosis - August 2017

Trichofolliculoma

Trichofolliculoma is a rare, benign skin lesion that was first described in 1944. While the etiology is largely known, it is considered to be a hamartoma with follicular differentiation that results when the pluripotent skin cells cease to differentiate into the hair follicle. The lesion lacks specific predilection for gender or race but most commonly occurs on the face of adults. Clinically, trichofolliculoma presents as a solitary, skin-colored papule or nodule. It may contain a central sebum-producing pore or have a tuft of white hair protruding from the central pore, although neither of these manifestations are mandatory. Trichofolliculomas generally are asymptomatic and are not associated with any systemic or other cutaneous diseases. Therefore, no treatment is required. However, surgical excision or curettage and electrodesiccation may be performed for cosmetic reasons.

Definitive diagnosis of trichofolliculoma requires a biopsy. The histopathology shows a primary cystic structure within the dermis that may or may not be connected to the epidermis. There are multiple abnormal secondary follicles that radiate from the primary cystic structure, and the entire apparatus is surrounded by a well-circumscribed dense connective tissue. Immunohistochemical studies have revealed that trichofolliculoma is characterized by activated, aberrant cytokeratin-15 (CK15)–positive follicle stem cells that show outer root sheath differentiation while attempting to make hair. This results in disorder of the normal hair cycle.

The clinical differential diagnosis for trichofolliculoma includes dermal nevus, basal cell carcinoma, and pilar sheath acanthoma. These cutaneous entities may be ruled out by histopathology.

The histopathology of basal cell carcinoma consists of tumors of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei. There is palisading around the periphery of the tumor with stromal retraction that leads to a clefting appearance, as well as mucinous change in the stroma.

The histopathology of dermal nevus reveals small nests of melanocytes within the upper dermis that commonly localize around the pilosebaceous units. There is variability in pigmentation and cellularity of the melanocytes, and there is no junctional component.

The histopathology of pilar sheath acanthoma shows dermal proliferation of lobules comprising benign squamous epithelium that arrange themselves around small cystic spaces. The lobules themselves are surrounded by eosinophilic basement membrane.

The case and photo were submitted by Victoria Billero, MS; Adam Wulkan, MD; and Caroline Winslow, MD, all of the department of dermatology, University of Miami (Fla.).

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Trichofolliculoma

Trichofolliculoma is a rare, benign skin lesion that was first described in 1944. While the etiology is largely known, it is considered to be a hamartoma with follicular differentiation that results when the pluripotent skin cells cease to differentiate into the hair follicle. The lesion lacks specific predilection for gender or race but most commonly occurs on the face of adults. Clinically, trichofolliculoma presents as a solitary, skin-colored papule or nodule. It may contain a central sebum-producing pore or have a tuft of white hair protruding from the central pore, although neither of these manifestations are mandatory. Trichofolliculomas generally are asymptomatic and are not associated with any systemic or other cutaneous diseases. Therefore, no treatment is required. However, surgical excision or curettage and electrodesiccation may be performed for cosmetic reasons.

Definitive diagnosis of trichofolliculoma requires a biopsy. The histopathology shows a primary cystic structure within the dermis that may or may not be connected to the epidermis. There are multiple abnormal secondary follicles that radiate from the primary cystic structure, and the entire apparatus is surrounded by a well-circumscribed dense connective tissue. Immunohistochemical studies have revealed that trichofolliculoma is characterized by activated, aberrant cytokeratin-15 (CK15)–positive follicle stem cells that show outer root sheath differentiation while attempting to make hair. This results in disorder of the normal hair cycle.

The clinical differential diagnosis for trichofolliculoma includes dermal nevus, basal cell carcinoma, and pilar sheath acanthoma. These cutaneous entities may be ruled out by histopathology.

The histopathology of basal cell carcinoma consists of tumors of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei. There is palisading around the periphery of the tumor with stromal retraction that leads to a clefting appearance, as well as mucinous change in the stroma.

The histopathology of dermal nevus reveals small nests of melanocytes within the upper dermis that commonly localize around the pilosebaceous units. There is variability in pigmentation and cellularity of the melanocytes, and there is no junctional component.

The histopathology of pilar sheath acanthoma shows dermal proliferation of lobules comprising benign squamous epithelium that arrange themselves around small cystic spaces. The lobules themselves are surrounded by eosinophilic basement membrane.

The case and photo were submitted by Victoria Billero, MS; Adam Wulkan, MD; and Caroline Winslow, MD, all of the department of dermatology, University of Miami (Fla.).

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Trichofolliculoma

Trichofolliculoma is a rare, benign skin lesion that was first described in 1944. While the etiology is largely known, it is considered to be a hamartoma with follicular differentiation that results when the pluripotent skin cells cease to differentiate into the hair follicle. The lesion lacks specific predilection for gender or race but most commonly occurs on the face of adults. Clinically, trichofolliculoma presents as a solitary, skin-colored papule or nodule. It may contain a central sebum-producing pore or have a tuft of white hair protruding from the central pore, although neither of these manifestations are mandatory. Trichofolliculomas generally are asymptomatic and are not associated with any systemic or other cutaneous diseases. Therefore, no treatment is required. However, surgical excision or curettage and electrodesiccation may be performed for cosmetic reasons.

Definitive diagnosis of trichofolliculoma requires a biopsy. The histopathology shows a primary cystic structure within the dermis that may or may not be connected to the epidermis. There are multiple abnormal secondary follicles that radiate from the primary cystic structure, and the entire apparatus is surrounded by a well-circumscribed dense connective tissue. Immunohistochemical studies have revealed that trichofolliculoma is characterized by activated, aberrant cytokeratin-15 (CK15)–positive follicle stem cells that show outer root sheath differentiation while attempting to make hair. This results in disorder of the normal hair cycle.

The clinical differential diagnosis for trichofolliculoma includes dermal nevus, basal cell carcinoma, and pilar sheath acanthoma. These cutaneous entities may be ruled out by histopathology.

The histopathology of basal cell carcinoma consists of tumors of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei. There is palisading around the periphery of the tumor with stromal retraction that leads to a clefting appearance, as well as mucinous change in the stroma.

The histopathology of dermal nevus reveals small nests of melanocytes within the upper dermis that commonly localize around the pilosebaceous units. There is variability in pigmentation and cellularity of the melanocytes, and there is no junctional component.

The histopathology of pilar sheath acanthoma shows dermal proliferation of lobules comprising benign squamous epithelium that arrange themselves around small cystic spaces. The lobules themselves are surrounded by eosinophilic basement membrane.

The case and photo were submitted by Victoria Billero, MS; Adam Wulkan, MD; and Caroline Winslow, MD, all of the department of dermatology, University of Miami (Fla.).

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 67-year-old white female with no significant past medical history presented as a first-time patient to clinic for a full skin check. An incidental finding of a solitary, asymptomatic, non-tender 8 mm flesh-colored papule with a tuft of long white hair protruding through a central pore was observed on her right lateral forehead that had been present for longer than 10 years.

Make the Diagnosis - July 2017

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis)

A biopsy revealed an intact epidermis with intense infiltration of neutrophils in the superficial dermis, striking superficial edema, and a few lymphoid cells, consistent with Sweet’s syndrome. The patient was started on prednisone with a slow taper and had resolution of her symptoms.

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is characterized by the sudden manifestation of painful edematous and erythematous papules, plaques, and/or nodules. As may be predicted by the descriptive name, the skin findings are often accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and other extracutaneous manifestations. Sweet’s syndrome is generally divided into three categories: classical (idiopathic), drug associated, and malignancy associated.

Classical (idiopathic) Sweet’s syndrome

Drug-associated Sweet’s syndrome

Drug-associated Sweet’s syndrome must meet all the diagnostic criteria of the classical variant, as well as a temporal relationship for both the onset and resolution of symptoms associated with the initiation and cessation of a drug, respectively. Signs and symptoms of the disease process typically develop 2 weeks after the initial drug exposure. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is the most commonly reported inciting drug; however, an extensive list of potential offenders has been described in the literature. Although most cases will self-resolve within several weeks of drug cessation, treatment with corticosteroids can expedite recovery.

Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome

Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome may occur as the first revelation of an undiagnosed malignancy, as a complication of an already diagnosed malignancy, or as a warning sign of the recurrence of a previously diagnosed malignancy. Association with solid tumors is uncommon, with approximately 85% of reported cases occurring in patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy (most frequently, acute myeloblastic leukemia). The treatment of choice for malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome is targeted at eradicating the underlying malignancy; however, most patients will receive a course of corticosteroids to aid in a faster resolution of symptoms. Very few cases of Sweet’s syndrome associated with untreated melanoma have been reported in the literature, as patients with melanoma are much more likely to develop Sweet’s syndrome as a result of anti-neoplastic drug therapy than as a result of the tumor itself.

While it is not completely clear if this patient’s diagnosis was the classical type or malignancy associated, it is more likely the former as the patient improved with oral corticosteroids.

This case and photo are courtesy of Natasha Cowan, University of California, San Diego, and Nick Celano, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis)

A biopsy revealed an intact epidermis with intense infiltration of neutrophils in the superficial dermis, striking superficial edema, and a few lymphoid cells, consistent with Sweet’s syndrome. The patient was started on prednisone with a slow taper and had resolution of her symptoms.

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is characterized by the sudden manifestation of painful edematous and erythematous papules, plaques, and/or nodules. As may be predicted by the descriptive name, the skin findings are often accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and other extracutaneous manifestations. Sweet’s syndrome is generally divided into three categories: classical (idiopathic), drug associated, and malignancy associated.

Classical (idiopathic) Sweet’s syndrome

Drug-associated Sweet’s syndrome

Drug-associated Sweet’s syndrome must meet all the diagnostic criteria of the classical variant, as well as a temporal relationship for both the onset and resolution of symptoms associated with the initiation and cessation of a drug, respectively. Signs and symptoms of the disease process typically develop 2 weeks after the initial drug exposure. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is the most commonly reported inciting drug; however, an extensive list of potential offenders has been described in the literature. Although most cases will self-resolve within several weeks of drug cessation, treatment with corticosteroids can expedite recovery.

Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome

Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome may occur as the first revelation of an undiagnosed malignancy, as a complication of an already diagnosed malignancy, or as a warning sign of the recurrence of a previously diagnosed malignancy. Association with solid tumors is uncommon, with approximately 85% of reported cases occurring in patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy (most frequently, acute myeloblastic leukemia). The treatment of choice for malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome is targeted at eradicating the underlying malignancy; however, most patients will receive a course of corticosteroids to aid in a faster resolution of symptoms. Very few cases of Sweet’s syndrome associated with untreated melanoma have been reported in the literature, as patients with melanoma are much more likely to develop Sweet’s syndrome as a result of anti-neoplastic drug therapy than as a result of the tumor itself.

While it is not completely clear if this patient’s diagnosis was the classical type or malignancy associated, it is more likely the former as the patient improved with oral corticosteroids.

This case and photo are courtesy of Natasha Cowan, University of California, San Diego, and Nick Celano, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis)

A biopsy revealed an intact epidermis with intense infiltration of neutrophils in the superficial dermis, striking superficial edema, and a few lymphoid cells, consistent with Sweet’s syndrome. The patient was started on prednisone with a slow taper and had resolution of her symptoms.

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is characterized by the sudden manifestation of painful edematous and erythematous papules, plaques, and/or nodules. As may be predicted by the descriptive name, the skin findings are often accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and other extracutaneous manifestations. Sweet’s syndrome is generally divided into three categories: classical (idiopathic), drug associated, and malignancy associated.

Classical (idiopathic) Sweet’s syndrome

Drug-associated Sweet’s syndrome

Drug-associated Sweet’s syndrome must meet all the diagnostic criteria of the classical variant, as well as a temporal relationship for both the onset and resolution of symptoms associated with the initiation and cessation of a drug, respectively. Signs and symptoms of the disease process typically develop 2 weeks after the initial drug exposure. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is the most commonly reported inciting drug; however, an extensive list of potential offenders has been described in the literature. Although most cases will self-resolve within several weeks of drug cessation, treatment with corticosteroids can expedite recovery.

Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome

Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome may occur as the first revelation of an undiagnosed malignancy, as a complication of an already diagnosed malignancy, or as a warning sign of the recurrence of a previously diagnosed malignancy. Association with solid tumors is uncommon, with approximately 85% of reported cases occurring in patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy (most frequently, acute myeloblastic leukemia). The treatment of choice for malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome is targeted at eradicating the underlying malignancy; however, most patients will receive a course of corticosteroids to aid in a faster resolution of symptoms. Very few cases of Sweet’s syndrome associated with untreated melanoma have been reported in the literature, as patients with melanoma are much more likely to develop Sweet’s syndrome as a result of anti-neoplastic drug therapy than as a result of the tumor itself.

While it is not completely clear if this patient’s diagnosis was the classical type or malignancy associated, it is more likely the former as the patient improved with oral corticosteroids.

This case and photo are courtesy of Natasha Cowan, University of California, San Diego, and Nick Celano, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 57-year-old homeless white female with history of untreated malignant melanoma presented with a one-week history of an itchy, painful rash on the right side of her body. Physical exam revealed scattered bullous and pustular edematous plaques on the right arm, hand, and lower leg. She had a fever of 101.5F and an elevated white blood cell count.

Make the Diagnosis - June 2017

Diagnosis: Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN)

Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN) is a rare, benign adnexal hamartoma first reported by Marsden et al. in 1979 as “comedo nevus of the palm” (Br J Dermatol. 1979 Dec;101[6]:717-22).

To date, 77 cases of PEODDN have been reported in the literature, with 53% having congenital onset. The average age of onset for the acquired lesions was 6 years. PEODDN affects males and females equally. Acral location is the most common (94%), but lesions have been reported less commonly on the trunk and face. A review of the literature found that most cases of PEODDN were independent, not associated with other conditions. Rarely, Bowen’s disease and squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to arise within PEODDN. Interestingly, two cases have been associated with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID).

Common differential diagnoses for PEODDN include porokeratosis of Mibelli, linear psoriasis, and linear epidermal nevus. Linear porokeratosis and porokeratosis of Mibelli are characterized by sharply demarcated hyperkeratotic annular lesions with distinct keratotic edges but do not have eccrine gland involvement on histopathology. Linear psoriasis, a rare form of psoriasis, is characterized by late onset linear psoriatic lesions along Blaschko lines. Linear epidermal nevus is a disease characterized by pruritic, erythematous scaly lesions following Blaschko lines that occurs in the first months of life and is slowly progressive. Histopathological features of PEODDN are diagnostic and distinguish it from these other clinical entities. A prominent parakeratotic column within an epidermal invagination that displays loss of the granular layer is found overlaying an eccrine duct with a dilated acrosyringium. Vacuolated and dyskeratotic keratinocytes are also typically present within the epidermal invagination.

The treatment for PEODDN remains elusive. Topical keratolytics, topical retinoids, topical steroids, topical calcipotriol, cryosurgery, phototherapy, and anthralin have been used to treat PEODDN unsuccessfully. Thus far, the most efficacious treatments include CO2 laser and surgical excision for small lesions. Given the young age of this patient, emollient therapy was chosen as treatment until the patient reaches an age at which the lesion is cosmetically more disturbing and other therapies may be safely attempted.

In conclusion, this patient represents a classic case of the rare entity, PEODDN, and draws attention to recent discoveries that a genetic mutation in GJB2 is causative. Because PEODDN shares its pathogenic mutation with KID syndrome, clinicians should be aware that, if the same mutation also affects germline cells, offspring have the potential to express manifestations of KID syndrome.

This case and photo are courtesy of Molly B. Hirt, a medical student at Indiana University, Indianapolis; Carrie L. Davis, MD, of the Dermatology Center of Southern Indiana and Indiana University, Bloomington; and Anita N. Haggstrom, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN)

Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN) is a rare, benign adnexal hamartoma first reported by Marsden et al. in 1979 as “comedo nevus of the palm” (Br J Dermatol. 1979 Dec;101[6]:717-22).

To date, 77 cases of PEODDN have been reported in the literature, with 53% having congenital onset. The average age of onset for the acquired lesions was 6 years. PEODDN affects males and females equally. Acral location is the most common (94%), but lesions have been reported less commonly on the trunk and face. A review of the literature found that most cases of PEODDN were independent, not associated with other conditions. Rarely, Bowen’s disease and squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to arise within PEODDN. Interestingly, two cases have been associated with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID).

Common differential diagnoses for PEODDN include porokeratosis of Mibelli, linear psoriasis, and linear epidermal nevus. Linear porokeratosis and porokeratosis of Mibelli are characterized by sharply demarcated hyperkeratotic annular lesions with distinct keratotic edges but do not have eccrine gland involvement on histopathology. Linear psoriasis, a rare form of psoriasis, is characterized by late onset linear psoriatic lesions along Blaschko lines. Linear epidermal nevus is a disease characterized by pruritic, erythematous scaly lesions following Blaschko lines that occurs in the first months of life and is slowly progressive. Histopathological features of PEODDN are diagnostic and distinguish it from these other clinical entities. A prominent parakeratotic column within an epidermal invagination that displays loss of the granular layer is found overlaying an eccrine duct with a dilated acrosyringium. Vacuolated and dyskeratotic keratinocytes are also typically present within the epidermal invagination.

The treatment for PEODDN remains elusive. Topical keratolytics, topical retinoids, topical steroids, topical calcipotriol, cryosurgery, phototherapy, and anthralin have been used to treat PEODDN unsuccessfully. Thus far, the most efficacious treatments include CO2 laser and surgical excision for small lesions. Given the young age of this patient, emollient therapy was chosen as treatment until the patient reaches an age at which the lesion is cosmetically more disturbing and other therapies may be safely attempted.

In conclusion, this patient represents a classic case of the rare entity, PEODDN, and draws attention to recent discoveries that a genetic mutation in GJB2 is causative. Because PEODDN shares its pathogenic mutation with KID syndrome, clinicians should be aware that, if the same mutation also affects germline cells, offspring have the potential to express manifestations of KID syndrome.

This case and photo are courtesy of Molly B. Hirt, a medical student at Indiana University, Indianapolis; Carrie L. Davis, MD, of the Dermatology Center of Southern Indiana and Indiana University, Bloomington; and Anita N. Haggstrom, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN)

Porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus (PEODDN) is a rare, benign adnexal hamartoma first reported by Marsden et al. in 1979 as “comedo nevus of the palm” (Br J Dermatol. 1979 Dec;101[6]:717-22).

To date, 77 cases of PEODDN have been reported in the literature, with 53% having congenital onset. The average age of onset for the acquired lesions was 6 years. PEODDN affects males and females equally. Acral location is the most common (94%), but lesions have been reported less commonly on the trunk and face. A review of the literature found that most cases of PEODDN were independent, not associated with other conditions. Rarely, Bowen’s disease and squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to arise within PEODDN. Interestingly, two cases have been associated with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID).

Common differential diagnoses for PEODDN include porokeratosis of Mibelli, linear psoriasis, and linear epidermal nevus. Linear porokeratosis and porokeratosis of Mibelli are characterized by sharply demarcated hyperkeratotic annular lesions with distinct keratotic edges but do not have eccrine gland involvement on histopathology. Linear psoriasis, a rare form of psoriasis, is characterized by late onset linear psoriatic lesions along Blaschko lines. Linear epidermal nevus is a disease characterized by pruritic, erythematous scaly lesions following Blaschko lines that occurs in the first months of life and is slowly progressive. Histopathological features of PEODDN are diagnostic and distinguish it from these other clinical entities. A prominent parakeratotic column within an epidermal invagination that displays loss of the granular layer is found overlaying an eccrine duct with a dilated acrosyringium. Vacuolated and dyskeratotic keratinocytes are also typically present within the epidermal invagination.

The treatment for PEODDN remains elusive. Topical keratolytics, topical retinoids, topical steroids, topical calcipotriol, cryosurgery, phototherapy, and anthralin have been used to treat PEODDN unsuccessfully. Thus far, the most efficacious treatments include CO2 laser and surgical excision for small lesions. Given the young age of this patient, emollient therapy was chosen as treatment until the patient reaches an age at which the lesion is cosmetically more disturbing and other therapies may be safely attempted.

In conclusion, this patient represents a classic case of the rare entity, PEODDN, and draws attention to recent discoveries that a genetic mutation in GJB2 is causative. Because PEODDN shares its pathogenic mutation with KID syndrome, clinicians should be aware that, if the same mutation also affects germline cells, offspring have the potential to express manifestations of KID syndrome.

This case and photo are courtesy of Molly B. Hirt, a medical student at Indiana University, Indianapolis; Carrie L. Davis, MD, of the Dermatology Center of Southern Indiana and Indiana University, Bloomington; and Anita N. Haggstrom, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Make the Diagnosis - May 2017

Dermatitis herpetiformis

The primary lesions of DH are vesicles and papules in a grouped or “herpetic” formation. However, as these lesions are extremely pruritic, the primary lesions may be absent in many cases and instead replaced by secondary excoriations and erosions. DH has a very classic distribution pattern, particularly involving the bilateral extensor surfaces, buttocks, and scalp. Although some cases of oral DH have been reported, mucosal involvement is generally considered to be very rare.

Despite its strong association with underlying celiac disease, most patients with DH do not report any associated gastrointestinal symptoms. Those with DH may present with any variety of other autoimmune conditions, with hypothyroidism being the most common. Interestingly, patients with DH have been shown to be at an increased development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is not certain whether adherence to a strict gluten-free diet reduces this risk in this population.

Diagnosis can be made with a proper clinical history and examination, tissue pathology, direct immunofluorescence microscopy (DIF), and/or serology, with DIF being the most definitive. Perilesional skin is preferred for DIF, as lesional biopsies have been found to have higher rates of false negative results. The characteristic DIF finding diagnostic of DH is granular IgA deposits within dermal papillae, which was seen in this patient’s DIF.

Adequate treatment of DH can usually be accomplished with a combination of dapsone and a gluten-free diet. Initially, dapsone may be used for more immediate relief of associated pruritus and other bothersome symptoms. A strict gluten-free diet should be implemented as soon as possible, and dapsone can be tapered approximately 2-3 months after initiation as to avoid potential adverse effects with longterm treatment at higher doses.

The case and photo were submitted by Natasha Cowan, BS, University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, and Nick Celano, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Dermatitis herpetiformis

The primary lesions of DH are vesicles and papules in a grouped or “herpetic” formation. However, as these lesions are extremely pruritic, the primary lesions may be absent in many cases and instead replaced by secondary excoriations and erosions. DH has a very classic distribution pattern, particularly involving the bilateral extensor surfaces, buttocks, and scalp. Although some cases of oral DH have been reported, mucosal involvement is generally considered to be very rare.

Despite its strong association with underlying celiac disease, most patients with DH do not report any associated gastrointestinal symptoms. Those with DH may present with any variety of other autoimmune conditions, with hypothyroidism being the most common. Interestingly, patients with DH have been shown to be at an increased development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is not certain whether adherence to a strict gluten-free diet reduces this risk in this population.

Diagnosis can be made with a proper clinical history and examination, tissue pathology, direct immunofluorescence microscopy (DIF), and/or serology, with DIF being the most definitive. Perilesional skin is preferred for DIF, as lesional biopsies have been found to have higher rates of false negative results. The characteristic DIF finding diagnostic of DH is granular IgA deposits within dermal papillae, which was seen in this patient’s DIF.

Adequate treatment of DH can usually be accomplished with a combination of dapsone and a gluten-free diet. Initially, dapsone may be used for more immediate relief of associated pruritus and other bothersome symptoms. A strict gluten-free diet should be implemented as soon as possible, and dapsone can be tapered approximately 2-3 months after initiation as to avoid potential adverse effects with longterm treatment at higher doses.

The case and photo were submitted by Natasha Cowan, BS, University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, and Nick Celano, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Dermatitis herpetiformis

The primary lesions of DH are vesicles and papules in a grouped or “herpetic” formation. However, as these lesions are extremely pruritic, the primary lesions may be absent in many cases and instead replaced by secondary excoriations and erosions. DH has a very classic distribution pattern, particularly involving the bilateral extensor surfaces, buttocks, and scalp. Although some cases of oral DH have been reported, mucosal involvement is generally considered to be very rare.

Despite its strong association with underlying celiac disease, most patients with DH do not report any associated gastrointestinal symptoms. Those with DH may present with any variety of other autoimmune conditions, with hypothyroidism being the most common. Interestingly, patients with DH have been shown to be at an increased development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is not certain whether adherence to a strict gluten-free diet reduces this risk in this population.

Diagnosis can be made with a proper clinical history and examination, tissue pathology, direct immunofluorescence microscopy (DIF), and/or serology, with DIF being the most definitive. Perilesional skin is preferred for DIF, as lesional biopsies have been found to have higher rates of false negative results. The characteristic DIF finding diagnostic of DH is granular IgA deposits within dermal papillae, which was seen in this patient’s DIF.

Adequate treatment of DH can usually be accomplished with a combination of dapsone and a gluten-free diet. Initially, dapsone may be used for more immediate relief of associated pruritus and other bothersome symptoms. A strict gluten-free diet should be implemented as soon as possible, and dapsone can be tapered approximately 2-3 months after initiation as to avoid potential adverse effects with longterm treatment at higher doses.

The case and photo were submitted by Natasha Cowan, BS, University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, and Nick Celano, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Make the Diagnosis - April 2017

Trichomycosis axillaris

Trichomycosis axillaris (TA) is a bacterial infection of the genus Corynebacterium that affects hairs in the axilla. Predisposing factors include poor local hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, and warm, humid climates. Gram-positive diphtheroids, classically Corynebacterium tenuis, mix with sweat on hair shafts and subsequently produce a cementing material. In the majority of cases, bacterial infection causes keratin damage to the hair shaft with sparing of the cortex. However, recent cases have reported significant invasion of the hair cortex by bacterial structures.

TA is often a clinical diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a discontinuous thick-layer coating of bacterial structures adhered to the hair shafts. Periodic acid–Schiff, gram, and Grocott silver stains are all positive. Examination of hairs with 20% hydrogen peroxide solution can provide a microscopic diagnosis. Wood lamp examination produces a weak, yellow fluorescence, and potassium hydroxide test demonstrates yellowish material of minimal translucency surrounding the hair cortex.

Complete resolution can be achieved by shaving off all the axillary hairs. It is imperative to maintain good hygiene and keep the area dry and clean. To prevent recurrence, topical benzoyl peroxide or topical antibiotics such as erythromycin and clindamycin can be applied. If axillary hyperhidrosis is concurrently present, aluminum chloride hexahydrate solution can decrease sweating and reduce the risk of bacterial regrowth. Injections of botulinum toxin can be used to treat the hyperhidrosis as well.

This patient responded well to topical erythromycin lotion.

This case and photo are courtesy of Jessica Cervantes, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/edermatologynews. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Trichomycosis axillaris

Trichomycosis axillaris (TA) is a bacterial infection of the genus Corynebacterium that affects hairs in the axilla. Predisposing factors include poor local hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, and warm, humid climates. Gram-positive diphtheroids, classically Corynebacterium tenuis, mix with sweat on hair shafts and subsequently produce a cementing material. In the majority of cases, bacterial infection causes keratin damage to the hair shaft with sparing of the cortex. However, recent cases have reported significant invasion of the hair cortex by bacterial structures.

TA is often a clinical diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a discontinuous thick-layer coating of bacterial structures adhered to the hair shafts. Periodic acid–Schiff, gram, and Grocott silver stains are all positive. Examination of hairs with 20% hydrogen peroxide solution can provide a microscopic diagnosis. Wood lamp examination produces a weak, yellow fluorescence, and potassium hydroxide test demonstrates yellowish material of minimal translucency surrounding the hair cortex.

Complete resolution can be achieved by shaving off all the axillary hairs. It is imperative to maintain good hygiene and keep the area dry and clean. To prevent recurrence, topical benzoyl peroxide or topical antibiotics such as erythromycin and clindamycin can be applied. If axillary hyperhidrosis is concurrently present, aluminum chloride hexahydrate solution can decrease sweating and reduce the risk of bacterial regrowth. Injections of botulinum toxin can be used to treat the hyperhidrosis as well.

This patient responded well to topical erythromycin lotion.

This case and photo are courtesy of Jessica Cervantes, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/edermatologynews. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Trichomycosis axillaris

Trichomycosis axillaris (TA) is a bacterial infection of the genus Corynebacterium that affects hairs in the axilla. Predisposing factors include poor local hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, and warm, humid climates. Gram-positive diphtheroids, classically Corynebacterium tenuis, mix with sweat on hair shafts and subsequently produce a cementing material. In the majority of cases, bacterial infection causes keratin damage to the hair shaft with sparing of the cortex. However, recent cases have reported significant invasion of the hair cortex by bacterial structures.

TA is often a clinical diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a discontinuous thick-layer coating of bacterial structures adhered to the hair shafts. Periodic acid–Schiff, gram, and Grocott silver stains are all positive. Examination of hairs with 20% hydrogen peroxide solution can provide a microscopic diagnosis. Wood lamp examination produces a weak, yellow fluorescence, and potassium hydroxide test demonstrates yellowish material of minimal translucency surrounding the hair cortex.

Complete resolution can be achieved by shaving off all the axillary hairs. It is imperative to maintain good hygiene and keep the area dry and clean. To prevent recurrence, topical benzoyl peroxide or topical antibiotics such as erythromycin and clindamycin can be applied. If axillary hyperhidrosis is concurrently present, aluminum chloride hexahydrate solution can decrease sweating and reduce the risk of bacterial regrowth. Injections of botulinum toxin can be used to treat the hyperhidrosis as well.

This patient responded well to topical erythromycin lotion.

This case and photo are courtesy of Jessica Cervantes, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/edermatologynews. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 35-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented with the chief complaint of occasional malodorous “crust in his underarms.” He used no prior treatments, and he did report axillary hyperhidrosis.