User login

VA shares its best practices to achieve HCV ‘cascade of cure’

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cares for more patients with hepatitis C virus than any other care provider in the country, and has achieved a rapid and sharp reduction in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among veterans over the past 3 years.

The VA has treated more than 92,000 HCV-infected individuals since the advent of oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in 2014. The number of veterans with HCV who were eligible for treatment was 168,000 in 2014 and 51,000 in July 2017, according to an article in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Sep 26. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073).

Given that success in HCV treatment, with a cure rate that exceeds 90% for those prescribed DAAs, the VA is well positioned to share best practices with other organizations, according to Pamela S. Belperio, PharmD, and her coauthors. The best practices harmonize with the recently outlined national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“The leveraging of health systems data transforms numbers into knowledge” that is used both by individual providers and the VA as a whole, wrote Dr. Belperio, national public health pharmacist in the VA’s public health division, and her coauthors.

Identifying veterans who were infected with HCV is simplified by means of electronic point-of-care reminders that prompt providers to conduct HCV risk assessment and testing. Veterans eligible for testing also receive automated letters that serve as a laboratory order form for HCV testing at a VA laboratory.

Adding HCV birth cohort screening as a performance measure and recommending reflex confirmatory HCV RNA testing for positive antibody tests were additional initiatives that contributed to the 3%-4% annual increase in veterans receiving HCV testing, “substantially higher than in other health care systems,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

To respect regional variations in practice within the VA system, multidisciplinary innovation teams meet in each region to identify opportunities for improving and streamlining HCV testing and treatment, using lean process improvement techniques. Regions also share innovations with each other.

The VA used a multipronged approach to raise awareness about HCV testing and treatment among VA health care providers and veterans. Provider reach has been expanded by extensive use of telemedicine, including real-time video calls between providers and patients or other providers at remote locations. Those telemedicine initiatives allow pharmacists and mental health providers to lend their expertise to physicians and other providers, who are themselves directly caring for HCV-infected individuals.

Patients at more than half of VA facilities receive care from physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and clinical pharmacy specialists, “who have been recognized as delivering the same quality of care and providing more timely access to HCV treatment,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her collaborators. Expanding the use of advanced practice providers allows more targeted use of specialists, and “is an important practice that can be adapted into other health care systems,” they noted.

Non–evidence-based criteria for HCV treatment eligibility remain a major barrier for HCV-infected individuals nationwide, despite VA studies showing “cure rates among veterans with alcohol, substance use, and mental health disorders that are similar to cure rates in those without these conditions,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

Within the VA, involving alcohol and substance use specialists, mental health providers, case managers, and social workers in the patient’s care team is an approach that can increase adherence and up the chance for a cure among the most vulnerable veterans.

The VA has been able to negotiate reduced pricing for the expensive DAAs, and has continued to receive additional appropriations to fund DAAs and other HCV-related resources. “Financing for HCV treatment and infrastructure resources, coupled with reduced drug prices, has been paramount to the VA’s success in curing HCV infection,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

However, they added, individual private insurers may not reap the benefits of achieving sweeping HCV cures within their particular patient panel, because patients frequently switch insurers. Still, “consistent leveraging of drug prices and removal of restrictions to HCV treatment among all insurers would help assuage this gap,” they wrote.

Dr. Belperio described the VA’s vision of a “hepatitis C cascade of cure” that occurs when individuals with chronic HCV are identified, linked to care, treated with DAAs, and achieve sustained viral response. The comprehensive strategies employed by the VA have meant that, from 2014 to 2016, the percentage of HCV-infected individuals who have been linked to care and treatment increased from 27% to 59%. Of those treated, SVR rates have risen from 51% to 84% during the same period, said Dr. Belperio and her coauthors.

It will not be easy to extend that success into the nongovernment sector, the article’s authors acknowledged. Still, “the VA recognizes the resources necessary to realize this goal and the innovations that could make it possible, and is poised to extend best practices to other health care organizations and providers delivering HCV care.”

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cares for more patients with hepatitis C virus than any other care provider in the country, and has achieved a rapid and sharp reduction in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among veterans over the past 3 years.

The VA has treated more than 92,000 HCV-infected individuals since the advent of oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in 2014. The number of veterans with HCV who were eligible for treatment was 168,000 in 2014 and 51,000 in July 2017, according to an article in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Sep 26. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073).

Given that success in HCV treatment, with a cure rate that exceeds 90% for those prescribed DAAs, the VA is well positioned to share best practices with other organizations, according to Pamela S. Belperio, PharmD, and her coauthors. The best practices harmonize with the recently outlined national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“The leveraging of health systems data transforms numbers into knowledge” that is used both by individual providers and the VA as a whole, wrote Dr. Belperio, national public health pharmacist in the VA’s public health division, and her coauthors.

Identifying veterans who were infected with HCV is simplified by means of electronic point-of-care reminders that prompt providers to conduct HCV risk assessment and testing. Veterans eligible for testing also receive automated letters that serve as a laboratory order form for HCV testing at a VA laboratory.

Adding HCV birth cohort screening as a performance measure and recommending reflex confirmatory HCV RNA testing for positive antibody tests were additional initiatives that contributed to the 3%-4% annual increase in veterans receiving HCV testing, “substantially higher than in other health care systems,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

To respect regional variations in practice within the VA system, multidisciplinary innovation teams meet in each region to identify opportunities for improving and streamlining HCV testing and treatment, using lean process improvement techniques. Regions also share innovations with each other.

The VA used a multipronged approach to raise awareness about HCV testing and treatment among VA health care providers and veterans. Provider reach has been expanded by extensive use of telemedicine, including real-time video calls between providers and patients or other providers at remote locations. Those telemedicine initiatives allow pharmacists and mental health providers to lend their expertise to physicians and other providers, who are themselves directly caring for HCV-infected individuals.

Patients at more than half of VA facilities receive care from physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and clinical pharmacy specialists, “who have been recognized as delivering the same quality of care and providing more timely access to HCV treatment,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her collaborators. Expanding the use of advanced practice providers allows more targeted use of specialists, and “is an important practice that can be adapted into other health care systems,” they noted.

Non–evidence-based criteria for HCV treatment eligibility remain a major barrier for HCV-infected individuals nationwide, despite VA studies showing “cure rates among veterans with alcohol, substance use, and mental health disorders that are similar to cure rates in those without these conditions,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

Within the VA, involving alcohol and substance use specialists, mental health providers, case managers, and social workers in the patient’s care team is an approach that can increase adherence and up the chance for a cure among the most vulnerable veterans.

The VA has been able to negotiate reduced pricing for the expensive DAAs, and has continued to receive additional appropriations to fund DAAs and other HCV-related resources. “Financing for HCV treatment and infrastructure resources, coupled with reduced drug prices, has been paramount to the VA’s success in curing HCV infection,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

However, they added, individual private insurers may not reap the benefits of achieving sweeping HCV cures within their particular patient panel, because patients frequently switch insurers. Still, “consistent leveraging of drug prices and removal of restrictions to HCV treatment among all insurers would help assuage this gap,” they wrote.

Dr. Belperio described the VA’s vision of a “hepatitis C cascade of cure” that occurs when individuals with chronic HCV are identified, linked to care, treated with DAAs, and achieve sustained viral response. The comprehensive strategies employed by the VA have meant that, from 2014 to 2016, the percentage of HCV-infected individuals who have been linked to care and treatment increased from 27% to 59%. Of those treated, SVR rates have risen from 51% to 84% during the same period, said Dr. Belperio and her coauthors.

It will not be easy to extend that success into the nongovernment sector, the article’s authors acknowledged. Still, “the VA recognizes the resources necessary to realize this goal and the innovations that could make it possible, and is poised to extend best practices to other health care organizations and providers delivering HCV care.”

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) cares for more patients with hepatitis C virus than any other care provider in the country, and has achieved a rapid and sharp reduction in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among veterans over the past 3 years.

The VA has treated more than 92,000 HCV-infected individuals since the advent of oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in 2014. The number of veterans with HCV who were eligible for treatment was 168,000 in 2014 and 51,000 in July 2017, according to an article in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Sep 26. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073).

Given that success in HCV treatment, with a cure rate that exceeds 90% for those prescribed DAAs, the VA is well positioned to share best practices with other organizations, according to Pamela S. Belperio, PharmD, and her coauthors. The best practices harmonize with the recently outlined national strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“The leveraging of health systems data transforms numbers into knowledge” that is used both by individual providers and the VA as a whole, wrote Dr. Belperio, national public health pharmacist in the VA’s public health division, and her coauthors.

Identifying veterans who were infected with HCV is simplified by means of electronic point-of-care reminders that prompt providers to conduct HCV risk assessment and testing. Veterans eligible for testing also receive automated letters that serve as a laboratory order form for HCV testing at a VA laboratory.

Adding HCV birth cohort screening as a performance measure and recommending reflex confirmatory HCV RNA testing for positive antibody tests were additional initiatives that contributed to the 3%-4% annual increase in veterans receiving HCV testing, “substantially higher than in other health care systems,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

To respect regional variations in practice within the VA system, multidisciplinary innovation teams meet in each region to identify opportunities for improving and streamlining HCV testing and treatment, using lean process improvement techniques. Regions also share innovations with each other.

The VA used a multipronged approach to raise awareness about HCV testing and treatment among VA health care providers and veterans. Provider reach has been expanded by extensive use of telemedicine, including real-time video calls between providers and patients or other providers at remote locations. Those telemedicine initiatives allow pharmacists and mental health providers to lend their expertise to physicians and other providers, who are themselves directly caring for HCV-infected individuals.

Patients at more than half of VA facilities receive care from physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and clinical pharmacy specialists, “who have been recognized as delivering the same quality of care and providing more timely access to HCV treatment,” wrote Dr. Belperio and her collaborators. Expanding the use of advanced practice providers allows more targeted use of specialists, and “is an important practice that can be adapted into other health care systems,” they noted.

Non–evidence-based criteria for HCV treatment eligibility remain a major barrier for HCV-infected individuals nationwide, despite VA studies showing “cure rates among veterans with alcohol, substance use, and mental health disorders that are similar to cure rates in those without these conditions,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

Within the VA, involving alcohol and substance use specialists, mental health providers, case managers, and social workers in the patient’s care team is an approach that can increase adherence and up the chance for a cure among the most vulnerable veterans.

The VA has been able to negotiate reduced pricing for the expensive DAAs, and has continued to receive additional appropriations to fund DAAs and other HCV-related resources. “Financing for HCV treatment and infrastructure resources, coupled with reduced drug prices, has been paramount to the VA’s success in curing HCV infection,” said Dr. Belperio and her colleagues.

However, they added, individual private insurers may not reap the benefits of achieving sweeping HCV cures within their particular patient panel, because patients frequently switch insurers. Still, “consistent leveraging of drug prices and removal of restrictions to HCV treatment among all insurers would help assuage this gap,” they wrote.

Dr. Belperio described the VA’s vision of a “hepatitis C cascade of cure” that occurs when individuals with chronic HCV are identified, linked to care, treated with DAAs, and achieve sustained viral response. The comprehensive strategies employed by the VA have meant that, from 2014 to 2016, the percentage of HCV-infected individuals who have been linked to care and treatment increased from 27% to 59%. Of those treated, SVR rates have risen from 51% to 84% during the same period, said Dr. Belperio and her coauthors.

It will not be easy to extend that success into the nongovernment sector, the article’s authors acknowledged. Still, “the VA recognizes the resources necessary to realize this goal and the innovations that could make it possible, and is poised to extend best practices to other health care organizations and providers delivering HCV care.”

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

ACOG urges standardization of postpartum hemorrhage treatment

Ob.gyns. and hospitals should have an organized and systematic treatment plan for postpartum hemorrhage, according to an updated practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

ACOG is recommending that obstetric care facilities post guidelines regarding the diagnosis methods and management techniques of postpartum hemorrhage. If postpartum hemorrhage is suspected, a physical exam should be performed to quickly inspect the uterus, cervix, vulva, and perineum to identify the source of bleeding. Once the cause has been identified, a treatment plan specific to the etiology of the bleeding can be implemented (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-86).

“Less invasive methods should always be used first,” Aaron Caughey, MD, PhD, one of the coauthors of the practice bulletin, said in a statement. “If those methods fail, then more aggressive interventions must be considered to preserve the life of the mother.”

The ACOG reVITALize program defines postpartum hemorrhage “as cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 mL or blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after the birth process,” which differs from more traditional definitions of postpartum hemorrhage that puts the blood loss at more than 500 mL after vaginal birth and more than 1,000 mL after cesarean delivery.

The unpredictable nature of postpartum hemorrhage and its potential for severe morbidity and mortality make identifying its risk factors a priority. Risk assessment tools have been shown to identify 60%-85% of patients who will experience a serious hemorrhagic event. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage can be made into a simple table that categorizes different factors into low, medium, or high risk categories and posted in obstetric care facilities.

“The important thing is for providers to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of excessive blood loss earlier and to have the resources at hand for the prompt escalation to more aggressive interventions if other therapies fail,” said Dr. Caughey, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Prevention is one of the key strategies outlined for combating postpartum hemorrhage. Many clinicians and organizations advise active management of the third stage of labor to decrease the likelihood of women experiencing postpartum hemorrhage. This can be done by administering oxytocin, massaging the uterus, and traction of the umbilical cord. Oxytocin can be administered both intravenously and intramuscularly and presents the lowest risk of adverse affects.

“By implementing standard protocols, we can improve outcomes,” Dr. Caughey said. “And this is even more critical for rural hospitals that often do not have the ability to treat a woman who may need a massive blood transfusion. They need to have a response plan in place for these obstetric emergencies, which includes triage and transferring patients to higher-level facilities, if necessary.”

Ob.gyns. and hospitals should have an organized and systematic treatment plan for postpartum hemorrhage, according to an updated practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

ACOG is recommending that obstetric care facilities post guidelines regarding the diagnosis methods and management techniques of postpartum hemorrhage. If postpartum hemorrhage is suspected, a physical exam should be performed to quickly inspect the uterus, cervix, vulva, and perineum to identify the source of bleeding. Once the cause has been identified, a treatment plan specific to the etiology of the bleeding can be implemented (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-86).

“Less invasive methods should always be used first,” Aaron Caughey, MD, PhD, one of the coauthors of the practice bulletin, said in a statement. “If those methods fail, then more aggressive interventions must be considered to preserve the life of the mother.”

The ACOG reVITALize program defines postpartum hemorrhage “as cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 mL or blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after the birth process,” which differs from more traditional definitions of postpartum hemorrhage that puts the blood loss at more than 500 mL after vaginal birth and more than 1,000 mL after cesarean delivery.

The unpredictable nature of postpartum hemorrhage and its potential for severe morbidity and mortality make identifying its risk factors a priority. Risk assessment tools have been shown to identify 60%-85% of patients who will experience a serious hemorrhagic event. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage can be made into a simple table that categorizes different factors into low, medium, or high risk categories and posted in obstetric care facilities.

“The important thing is for providers to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of excessive blood loss earlier and to have the resources at hand for the prompt escalation to more aggressive interventions if other therapies fail,” said Dr. Caughey, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Prevention is one of the key strategies outlined for combating postpartum hemorrhage. Many clinicians and organizations advise active management of the third stage of labor to decrease the likelihood of women experiencing postpartum hemorrhage. This can be done by administering oxytocin, massaging the uterus, and traction of the umbilical cord. Oxytocin can be administered both intravenously and intramuscularly and presents the lowest risk of adverse affects.

“By implementing standard protocols, we can improve outcomes,” Dr. Caughey said. “And this is even more critical for rural hospitals that often do not have the ability to treat a woman who may need a massive blood transfusion. They need to have a response plan in place for these obstetric emergencies, which includes triage and transferring patients to higher-level facilities, if necessary.”

Ob.gyns. and hospitals should have an organized and systematic treatment plan for postpartum hemorrhage, according to an updated practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

ACOG is recommending that obstetric care facilities post guidelines regarding the diagnosis methods and management techniques of postpartum hemorrhage. If postpartum hemorrhage is suspected, a physical exam should be performed to quickly inspect the uterus, cervix, vulva, and perineum to identify the source of bleeding. Once the cause has been identified, a treatment plan specific to the etiology of the bleeding can be implemented (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-86).

“Less invasive methods should always be used first,” Aaron Caughey, MD, PhD, one of the coauthors of the practice bulletin, said in a statement. “If those methods fail, then more aggressive interventions must be considered to preserve the life of the mother.”

The ACOG reVITALize program defines postpartum hemorrhage “as cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 mL or blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after the birth process,” which differs from more traditional definitions of postpartum hemorrhage that puts the blood loss at more than 500 mL after vaginal birth and more than 1,000 mL after cesarean delivery.

The unpredictable nature of postpartum hemorrhage and its potential for severe morbidity and mortality make identifying its risk factors a priority. Risk assessment tools have been shown to identify 60%-85% of patients who will experience a serious hemorrhagic event. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage can be made into a simple table that categorizes different factors into low, medium, or high risk categories and posted in obstetric care facilities.

“The important thing is for providers to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of excessive blood loss earlier and to have the resources at hand for the prompt escalation to more aggressive interventions if other therapies fail,” said Dr. Caughey, professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

Prevention is one of the key strategies outlined for combating postpartum hemorrhage. Many clinicians and organizations advise active management of the third stage of labor to decrease the likelihood of women experiencing postpartum hemorrhage. This can be done by administering oxytocin, massaging the uterus, and traction of the umbilical cord. Oxytocin can be administered both intravenously and intramuscularly and presents the lowest risk of adverse affects.

“By implementing standard protocols, we can improve outcomes,” Dr. Caughey said. “And this is even more critical for rural hospitals that often do not have the ability to treat a woman who may need a massive blood transfusion. They need to have a response plan in place for these obstetric emergencies, which includes triage and transferring patients to higher-level facilities, if necessary.”

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

No difference in survival between x-ray or CT NSCLC follow-up

Madrid – Computed tomography scans do not appear to be superior to plain old chest x-rays for follow-up of patients with completely resected non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), results of a randomized clinical trial suggest.

Among 1,775 patients followed out to 10 years with either a “minimal” protocol – consisting of history, physical exam, and periodic chest x-rays – or a “maximal” protocol – including CT scans of the thorax and upper abdomen, as well as bronchoscopy for squamous-cell carcinomas – there were no significant differences in overall survival at either 3, 5, or 8 years of follow-up, reported Virginie Westeel, MD, from the Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire of the Hôpital Jean Minjoz in Besançon, France.

In hopes of finding that answer, Dr. Westeel and colleagues in the French Cooperative Thoracic Oncology Group conducted a clinical trial comparing the standard follow-up approach recommended in most clinical guidelines, as described by Dr. Westeel, with an experimental protocol consisting of history and exam plus chest x-ray, CT scans, and fiber-optic bronchoscopy (mandatory for squamous- and large-cell carcinomas, optional for adenocarcinomas).

Patients with completely resected stage I, II, and IIIA tumors, and T4 tumors with pulmonary nodules in the same lobe, were randomly assigned to follow-up with one of the two protocols.

In each trial arm, the assigned procedures were repeated every 6 months after randomization for the first 2 years, then yearly until 5 years.

After a median follow-up of 8.7 years, there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint of overall survival. Median OS was 123.6 months in the maximal protocol group, compared with 99.7 months in the minimal protocol group (P = .037)

The 3-, 5-, and 8-year survival rates for the maximal and minimal protocols, respectively, were 76.1% vs. 77.3%, 65.8% vs. 66.7%, and 54.6% vs. 51.7%.

Because there appeared to be a separation of the survival curve beginning around 8 years, the investigators performed an exploratory 2-year landmark analysis.

They found that, among patients who had a recurrence within 24 months of randomization, there was no difference in OS between each follow-up protocol. However, among those patients with no recurrence within 24 months of resection, the median OS was not reached among patients assigned to the maximal protocol versus 129.3 months for those assigned to the minimal protocol (P = .04).

Patients without early recurrence had higher rates of secondary primary cancers, and for these patients, early detection with CT-based surveillance could explain the differences in overall survival, Dr. Westeel said.

“Our suggestion for practice is that, because there is no survival difference, both follow-up protocols are acceptable. However, a CT scan every 6 months is probably of no value in the first 2 years,” but yearly chest CTs to detect second primary cancers early may be of interest, she said.

Enriqueta Felip, MD, from Vall D’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, who was not involved in the trial, commented that, while the study needed to be conducted, it was unlikely to change her clinical practice because of potential differences among patients with varying stages of NSCLC at the time of resection.

“I think it’s an important trial, [but] tomorrow I will follow my patients with a CT scan,” she said.

Dr. Felip was an invited expert at the briefing.

The study was supported by the French Ministry of Health, Fondation de France, and Laboratoire Lilly. Dr. Westeel and Dr. Felip reported no conflicts of interest relevant to the study.

Madrid – Computed tomography scans do not appear to be superior to plain old chest x-rays for follow-up of patients with completely resected non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), results of a randomized clinical trial suggest.

Among 1,775 patients followed out to 10 years with either a “minimal” protocol – consisting of history, physical exam, and periodic chest x-rays – or a “maximal” protocol – including CT scans of the thorax and upper abdomen, as well as bronchoscopy for squamous-cell carcinomas – there were no significant differences in overall survival at either 3, 5, or 8 years of follow-up, reported Virginie Westeel, MD, from the Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire of the Hôpital Jean Minjoz in Besançon, France.

In hopes of finding that answer, Dr. Westeel and colleagues in the French Cooperative Thoracic Oncology Group conducted a clinical trial comparing the standard follow-up approach recommended in most clinical guidelines, as described by Dr. Westeel, with an experimental protocol consisting of history and exam plus chest x-ray, CT scans, and fiber-optic bronchoscopy (mandatory for squamous- and large-cell carcinomas, optional for adenocarcinomas).

Patients with completely resected stage I, II, and IIIA tumors, and T4 tumors with pulmonary nodules in the same lobe, were randomly assigned to follow-up with one of the two protocols.

In each trial arm, the assigned procedures were repeated every 6 months after randomization for the first 2 years, then yearly until 5 years.

After a median follow-up of 8.7 years, there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint of overall survival. Median OS was 123.6 months in the maximal protocol group, compared with 99.7 months in the minimal protocol group (P = .037)

The 3-, 5-, and 8-year survival rates for the maximal and minimal protocols, respectively, were 76.1% vs. 77.3%, 65.8% vs. 66.7%, and 54.6% vs. 51.7%.

Because there appeared to be a separation of the survival curve beginning around 8 years, the investigators performed an exploratory 2-year landmark analysis.

They found that, among patients who had a recurrence within 24 months of randomization, there was no difference in OS between each follow-up protocol. However, among those patients with no recurrence within 24 months of resection, the median OS was not reached among patients assigned to the maximal protocol versus 129.3 months for those assigned to the minimal protocol (P = .04).

Patients without early recurrence had higher rates of secondary primary cancers, and for these patients, early detection with CT-based surveillance could explain the differences in overall survival, Dr. Westeel said.

“Our suggestion for practice is that, because there is no survival difference, both follow-up protocols are acceptable. However, a CT scan every 6 months is probably of no value in the first 2 years,” but yearly chest CTs to detect second primary cancers early may be of interest, she said.

Enriqueta Felip, MD, from Vall D’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, who was not involved in the trial, commented that, while the study needed to be conducted, it was unlikely to change her clinical practice because of potential differences among patients with varying stages of NSCLC at the time of resection.

“I think it’s an important trial, [but] tomorrow I will follow my patients with a CT scan,” she said.

Dr. Felip was an invited expert at the briefing.

The study was supported by the French Ministry of Health, Fondation de France, and Laboratoire Lilly. Dr. Westeel and Dr. Felip reported no conflicts of interest relevant to the study.

Madrid – Computed tomography scans do not appear to be superior to plain old chest x-rays for follow-up of patients with completely resected non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), results of a randomized clinical trial suggest.

Among 1,775 patients followed out to 10 years with either a “minimal” protocol – consisting of history, physical exam, and periodic chest x-rays – or a “maximal” protocol – including CT scans of the thorax and upper abdomen, as well as bronchoscopy for squamous-cell carcinomas – there were no significant differences in overall survival at either 3, 5, or 8 years of follow-up, reported Virginie Westeel, MD, from the Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire of the Hôpital Jean Minjoz in Besançon, France.

In hopes of finding that answer, Dr. Westeel and colleagues in the French Cooperative Thoracic Oncology Group conducted a clinical trial comparing the standard follow-up approach recommended in most clinical guidelines, as described by Dr. Westeel, with an experimental protocol consisting of history and exam plus chest x-ray, CT scans, and fiber-optic bronchoscopy (mandatory for squamous- and large-cell carcinomas, optional for adenocarcinomas).

Patients with completely resected stage I, II, and IIIA tumors, and T4 tumors with pulmonary nodules in the same lobe, were randomly assigned to follow-up with one of the two protocols.

In each trial arm, the assigned procedures were repeated every 6 months after randomization for the first 2 years, then yearly until 5 years.

After a median follow-up of 8.7 years, there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint of overall survival. Median OS was 123.6 months in the maximal protocol group, compared with 99.7 months in the minimal protocol group (P = .037)

The 3-, 5-, and 8-year survival rates for the maximal and minimal protocols, respectively, were 76.1% vs. 77.3%, 65.8% vs. 66.7%, and 54.6% vs. 51.7%.

Because there appeared to be a separation of the survival curve beginning around 8 years, the investigators performed an exploratory 2-year landmark analysis.

They found that, among patients who had a recurrence within 24 months of randomization, there was no difference in OS between each follow-up protocol. However, among those patients with no recurrence within 24 months of resection, the median OS was not reached among patients assigned to the maximal protocol versus 129.3 months for those assigned to the minimal protocol (P = .04).

Patients without early recurrence had higher rates of secondary primary cancers, and for these patients, early detection with CT-based surveillance could explain the differences in overall survival, Dr. Westeel said.

“Our suggestion for practice is that, because there is no survival difference, both follow-up protocols are acceptable. However, a CT scan every 6 months is probably of no value in the first 2 years,” but yearly chest CTs to detect second primary cancers early may be of interest, she said.

Enriqueta Felip, MD, from Vall D’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, who was not involved in the trial, commented that, while the study needed to be conducted, it was unlikely to change her clinical practice because of potential differences among patients with varying stages of NSCLC at the time of resection.

“I think it’s an important trial, [but] tomorrow I will follow my patients with a CT scan,” she said.

Dr. Felip was an invited expert at the briefing.

The study was supported by the French Ministry of Health, Fondation de France, and Laboratoire Lilly. Dr. Westeel and Dr. Felip reported no conflicts of interest relevant to the study.

AT ESMO 2017

Key clinical point: There were no differences in long-term overall survival among patients with resected NSCLC followed with x-rays and those followed with CT scans.

Major finding: Overall survival rates at 3, 5, and 8 years were similar among patients followed with minimal or maximal protocols.

Data source: Randomized controlled trial in 1,775 patients with completely resected non–small cell lung cancer.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the French Ministry of Health, Fondation de France, and Laboratoire Lilly. Dr. Westeel and Dr. Felip reported no conflicts of interest relevant to the study.

VIDEO: What’s new in AAP’s pediatric hypertension guidelines

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

SAN FRANCISCO – The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released new hypertension guidelines for children and adolescents.

Some of the advice is similar to the group’s last effort in 2004, but there are a few key changes that clinicians need to know, according to lead author Joseph Flynn, MD, professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He explained what they are, and the reasons behind them, in an interview at the joint hypertension scientific sessions sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension (Pediatrics. 2017 Aug 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904).

The prevalence of pediatric hypertension, he said, now rivals asthma.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA/ASH JOINT SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

New data prompt update to ACC guidance on nonstatin LDL lowering

The American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways has released a “focused update” for the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The update was deemed by the ECDP writing committee to be desirable given the additional evidence and perspectives that have emerged since the publication of the 2016 version, particularly with respect to the efficacy and safety of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for the secondary prevention of ASCVD, as well as the best use of ezetimibe in addition to statin therapy after acute coronary syndrome.

The ECDP algorithms endorse the four evidence-based statin benefit groups identified in the 2013 guidelines (adults aged 21 and older with clinical ASCVD, adults aged 21 and older with LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, adults aged 40-75 years without ASCVD but with diabetes and with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, and adults aged 40-75 without ASCVD or diabetes but with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD of 7.5% or greater) and assume that the patient is currently taking or has attempted to take a statin, they noted.

Among the changes in the 2017 focused update are:

- Consideration of new randomized clinical trial data for the PCSK9 inhibitors evolocumab and bococizumab. Namely, they included results from the cardiovascular outcomes trials FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) and SPIRE-1 and SPIRE-2 (Studies of PCSK9 Inhibition and the Reduction of Vascular Events), which were published in early 2017.

- An adjustment in the ECDP algorithms with respect to thresholds for consideration of net ASCVD risk reduction. The 2016 ECDP thresholds for risk reduction benefit were percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C level in patients with clinical ASCVD, baseline LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, and primary prevention. In patients with diabetes with or without clinical ASCVD, clinicians were allowed to consider absolute LDL-C and/or non-HDL-cholesterol levels. In the 2017 ECDP update, the thresholds are percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C or non-HDL-C levels for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups. This change was based on the inclusion criteria of the FOURIER trial, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes after an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab), and the SPIRE-2 trial, all of which included non-HDL-C thresholds. “In alignment with these inclusion criteria, the 2017 Focused Update includes both LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds for evaluation of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit when considering the addition of nonstatin therapies for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups” the update explained.

- An expansion of the threshold for consideration of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit from a reduction of LDL C of at least 50%, as well as consideration of LDL-C less than 70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C less than 100 mg/dL for all patients (that is, both those with and those without comorbidities) who have clinical ASCVD and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL. The 2016 ECDP had different thresholds for those with versus those without comorbidities. This change was based on findings from the FOURIER trial and the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial).“Based on consideration of all available evidence, the consensus of the writing committee members is that lower LDL-C levels are safe and optimal in patients with clinical ASCVD due to [their] increased risk of recurrent events,” they said.

- An expanded recommendation on the use of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibition. The 2016 ECDP stated that “if a decision is made to proceed with the addition of nonstatin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the addition of ezetimibe as the initial agent and a PCSK9 inhibitor as the second agent.” However, based on the FOURIER findings, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial, and the IMPROVE-IT trial, the 2017 Focused Update states that, if such a decision is made in patients with clinical ASCVD with comorbidities and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, it is reasonable to weigh the addition of either ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor in light of “considerations of the additional percent LDL-C reduction desired, patient preferences, costs, route of administration, and other factors.” The update also spells out considerations that may favor the initial choice of ezetimibe versus a PCSK9 inhibitor (such as requiring less than 25% additional lowering of LDL-C, an age of over 75 years, cost, and other patient factors and preferences) .

- Additional factors, based on the FOURIER trial results and inclusion criteria, that may be considered for the identification of higher-risk patients with clinical ASCVD. The 2016 ECDP included on this list diabetes, a recent ASCVD event, an ASCVD event while already taking a statin, poorly controlled other major ASCVD risk factors, elevated lipoprotein, chronic kidney disease, symptomatic heart failure, maintenance hemodialysis, and baseline LDL-C of at least 190 mg/dL not due to secondary causes. The 2017 update added being 65 years or older, prior MI or nonhemorrhagic stroke, current daily cigarette smoking, symptomatic peripheral artery disease with prior MI or stroke, history of non-MI related coronary revascularization, residual coronary artery disease with at least 40% stenosis in at least two large vessels, HDL-C less than 40 mg/dL for men and less than 50 mg/dL for women, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein greater than 2 mg/L, and metabolic syndrome.

The content of the full ECDP has been changed in accordance with these updates and now includes more extensive and detailed guidance for decision making – both in the text and in treatment algorithms.

Aspects that remain unchanged include the decision pathways and algorithms for the use of ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in primary prevention patients with LDL-C less than 190 mg/dL or in those without ASCVD and LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater unattributable to secondary causes.

In addition to other changes made for the purpose of clarification and consistency, recommendations regarding bile acid–sequestrant use were downgraded; these are now only recommended as optional secondary agents for consideration in patients who cannot tolerate ezetimibe.

“[These] recommendations attempt to provide practical guidance for clinicians and patients regarding the use of nonstatin therapies to further reduce ASCVD risk in situations not covered by the guideline until such time as the scientific evidence base expands and cardiovascular outcomes trials are completed with new agents for ASCVD risk reduction,” the committee concluded.

Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported having no disclosures.

The American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways has released a “focused update” for the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The update was deemed by the ECDP writing committee to be desirable given the additional evidence and perspectives that have emerged since the publication of the 2016 version, particularly with respect to the efficacy and safety of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for the secondary prevention of ASCVD, as well as the best use of ezetimibe in addition to statin therapy after acute coronary syndrome.

The ECDP algorithms endorse the four evidence-based statin benefit groups identified in the 2013 guidelines (adults aged 21 and older with clinical ASCVD, adults aged 21 and older with LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, adults aged 40-75 years without ASCVD but with diabetes and with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, and adults aged 40-75 without ASCVD or diabetes but with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD of 7.5% or greater) and assume that the patient is currently taking or has attempted to take a statin, they noted.

Among the changes in the 2017 focused update are:

- Consideration of new randomized clinical trial data for the PCSK9 inhibitors evolocumab and bococizumab. Namely, they included results from the cardiovascular outcomes trials FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) and SPIRE-1 and SPIRE-2 (Studies of PCSK9 Inhibition and the Reduction of Vascular Events), which were published in early 2017.

- An adjustment in the ECDP algorithms with respect to thresholds for consideration of net ASCVD risk reduction. The 2016 ECDP thresholds for risk reduction benefit were percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C level in patients with clinical ASCVD, baseline LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, and primary prevention. In patients with diabetes with or without clinical ASCVD, clinicians were allowed to consider absolute LDL-C and/or non-HDL-cholesterol levels. In the 2017 ECDP update, the thresholds are percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C or non-HDL-C levels for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups. This change was based on the inclusion criteria of the FOURIER trial, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes after an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab), and the SPIRE-2 trial, all of which included non-HDL-C thresholds. “In alignment with these inclusion criteria, the 2017 Focused Update includes both LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds for evaluation of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit when considering the addition of nonstatin therapies for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups” the update explained.

- An expansion of the threshold for consideration of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit from a reduction of LDL C of at least 50%, as well as consideration of LDL-C less than 70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C less than 100 mg/dL for all patients (that is, both those with and those without comorbidities) who have clinical ASCVD and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL. The 2016 ECDP had different thresholds for those with versus those without comorbidities. This change was based on findings from the FOURIER trial and the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial).“Based on consideration of all available evidence, the consensus of the writing committee members is that lower LDL-C levels are safe and optimal in patients with clinical ASCVD due to [their] increased risk of recurrent events,” they said.

- An expanded recommendation on the use of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibition. The 2016 ECDP stated that “if a decision is made to proceed with the addition of nonstatin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the addition of ezetimibe as the initial agent and a PCSK9 inhibitor as the second agent.” However, based on the FOURIER findings, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial, and the IMPROVE-IT trial, the 2017 Focused Update states that, if such a decision is made in patients with clinical ASCVD with comorbidities and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, it is reasonable to weigh the addition of either ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor in light of “considerations of the additional percent LDL-C reduction desired, patient preferences, costs, route of administration, and other factors.” The update also spells out considerations that may favor the initial choice of ezetimibe versus a PCSK9 inhibitor (such as requiring less than 25% additional lowering of LDL-C, an age of over 75 years, cost, and other patient factors and preferences) .

- Additional factors, based on the FOURIER trial results and inclusion criteria, that may be considered for the identification of higher-risk patients with clinical ASCVD. The 2016 ECDP included on this list diabetes, a recent ASCVD event, an ASCVD event while already taking a statin, poorly controlled other major ASCVD risk factors, elevated lipoprotein, chronic kidney disease, symptomatic heart failure, maintenance hemodialysis, and baseline LDL-C of at least 190 mg/dL not due to secondary causes. The 2017 update added being 65 years or older, prior MI or nonhemorrhagic stroke, current daily cigarette smoking, symptomatic peripheral artery disease with prior MI or stroke, history of non-MI related coronary revascularization, residual coronary artery disease with at least 40% stenosis in at least two large vessels, HDL-C less than 40 mg/dL for men and less than 50 mg/dL for women, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein greater than 2 mg/L, and metabolic syndrome.

The content of the full ECDP has been changed in accordance with these updates and now includes more extensive and detailed guidance for decision making – both in the text and in treatment algorithms.

Aspects that remain unchanged include the decision pathways and algorithms for the use of ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in primary prevention patients with LDL-C less than 190 mg/dL or in those without ASCVD and LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater unattributable to secondary causes.

In addition to other changes made for the purpose of clarification and consistency, recommendations regarding bile acid–sequestrant use were downgraded; these are now only recommended as optional secondary agents for consideration in patients who cannot tolerate ezetimibe.

“[These] recommendations attempt to provide practical guidance for clinicians and patients regarding the use of nonstatin therapies to further reduce ASCVD risk in situations not covered by the guideline until such time as the scientific evidence base expands and cardiovascular outcomes trials are completed with new agents for ASCVD risk reduction,” the committee concluded.

Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported having no disclosures.

The American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways has released a “focused update” for the 2016 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway (ECDP) on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

The update was deemed by the ECDP writing committee to be desirable given the additional evidence and perspectives that have emerged since the publication of the 2016 version, particularly with respect to the efficacy and safety of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for the secondary prevention of ASCVD, as well as the best use of ezetimibe in addition to statin therapy after acute coronary syndrome.

The ECDP algorithms endorse the four evidence-based statin benefit groups identified in the 2013 guidelines (adults aged 21 and older with clinical ASCVD, adults aged 21 and older with LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, adults aged 40-75 years without ASCVD but with diabetes and with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, and adults aged 40-75 without ASCVD or diabetes but with LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL and an estimated 10-year risk for ASCVD of 7.5% or greater) and assume that the patient is currently taking or has attempted to take a statin, they noted.

Among the changes in the 2017 focused update are:

- Consideration of new randomized clinical trial data for the PCSK9 inhibitors evolocumab and bococizumab. Namely, they included results from the cardiovascular outcomes trials FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk) and SPIRE-1 and SPIRE-2 (Studies of PCSK9 Inhibition and the Reduction of Vascular Events), which were published in early 2017.

- An adjustment in the ECDP algorithms with respect to thresholds for consideration of net ASCVD risk reduction. The 2016 ECDP thresholds for risk reduction benefit were percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C level in patients with clinical ASCVD, baseline LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater, and primary prevention. In patients with diabetes with or without clinical ASCVD, clinicians were allowed to consider absolute LDL-C and/or non-HDL-cholesterol levels. In the 2017 ECDP update, the thresholds are percent reduction in LDL-C with consideration of absolute LDL-C or non-HDL-C levels for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups. This change was based on the inclusion criteria of the FOURIER trial, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial (Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes after an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab), and the SPIRE-2 trial, all of which included non-HDL-C thresholds. “In alignment with these inclusion criteria, the 2017 Focused Update includes both LDL-C and non-HDL-C thresholds for evaluation of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit when considering the addition of nonstatin therapies for patients in each of the four statin benefit groups” the update explained.

- An expansion of the threshold for consideration of net ASCVD risk-reduction benefit from a reduction of LDL C of at least 50%, as well as consideration of LDL-C less than 70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C less than 100 mg/dL for all patients (that is, both those with and those without comorbidities) who have clinical ASCVD and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL. The 2016 ECDP had different thresholds for those with versus those without comorbidities. This change was based on findings from the FOURIER trial and the IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial).“Based on consideration of all available evidence, the consensus of the writing committee members is that lower LDL-C levels are safe and optimal in patients with clinical ASCVD due to [their] increased risk of recurrent events,” they said.

- An expanded recommendation on the use of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibition. The 2016 ECDP stated that “if a decision is made to proceed with the addition of nonstatin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy, it is reasonable to consider the addition of ezetimibe as the initial agent and a PCSK9 inhibitor as the second agent.” However, based on the FOURIER findings, the ongoing ODYSSEY Outcomes trial, and the IMPROVE-IT trial, the 2017 Focused Update states that, if such a decision is made in patients with clinical ASCVD with comorbidities and baseline LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL, it is reasonable to weigh the addition of either ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor in light of “considerations of the additional percent LDL-C reduction desired, patient preferences, costs, route of administration, and other factors.” The update also spells out considerations that may favor the initial choice of ezetimibe versus a PCSK9 inhibitor (such as requiring less than 25% additional lowering of LDL-C, an age of over 75 years, cost, and other patient factors and preferences) .

- Additional factors, based on the FOURIER trial results and inclusion criteria, that may be considered for the identification of higher-risk patients with clinical ASCVD. The 2016 ECDP included on this list diabetes, a recent ASCVD event, an ASCVD event while already taking a statin, poorly controlled other major ASCVD risk factors, elevated lipoprotein, chronic kidney disease, symptomatic heart failure, maintenance hemodialysis, and baseline LDL-C of at least 190 mg/dL not due to secondary causes. The 2017 update added being 65 years or older, prior MI or nonhemorrhagic stroke, current daily cigarette smoking, symptomatic peripheral artery disease with prior MI or stroke, history of non-MI related coronary revascularization, residual coronary artery disease with at least 40% stenosis in at least two large vessels, HDL-C less than 40 mg/dL for men and less than 50 mg/dL for women, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein greater than 2 mg/L, and metabolic syndrome.

The content of the full ECDP has been changed in accordance with these updates and now includes more extensive and detailed guidance for decision making – both in the text and in treatment algorithms.

Aspects that remain unchanged include the decision pathways and algorithms for the use of ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors in primary prevention patients with LDL-C less than 190 mg/dL or in those without ASCVD and LDL-C of 190 mg/dL or greater unattributable to secondary causes.

In addition to other changes made for the purpose of clarification and consistency, recommendations regarding bile acid–sequestrant use were downgraded; these are now only recommended as optional secondary agents for consideration in patients who cannot tolerate ezetimibe.

“[These] recommendations attempt to provide practical guidance for clinicians and patients regarding the use of nonstatin therapies to further reduce ASCVD risk in situations not covered by the guideline until such time as the scientific evidence base expands and cardiovascular outcomes trials are completed with new agents for ASCVD risk reduction,” the committee concluded.

Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported having no disclosures.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

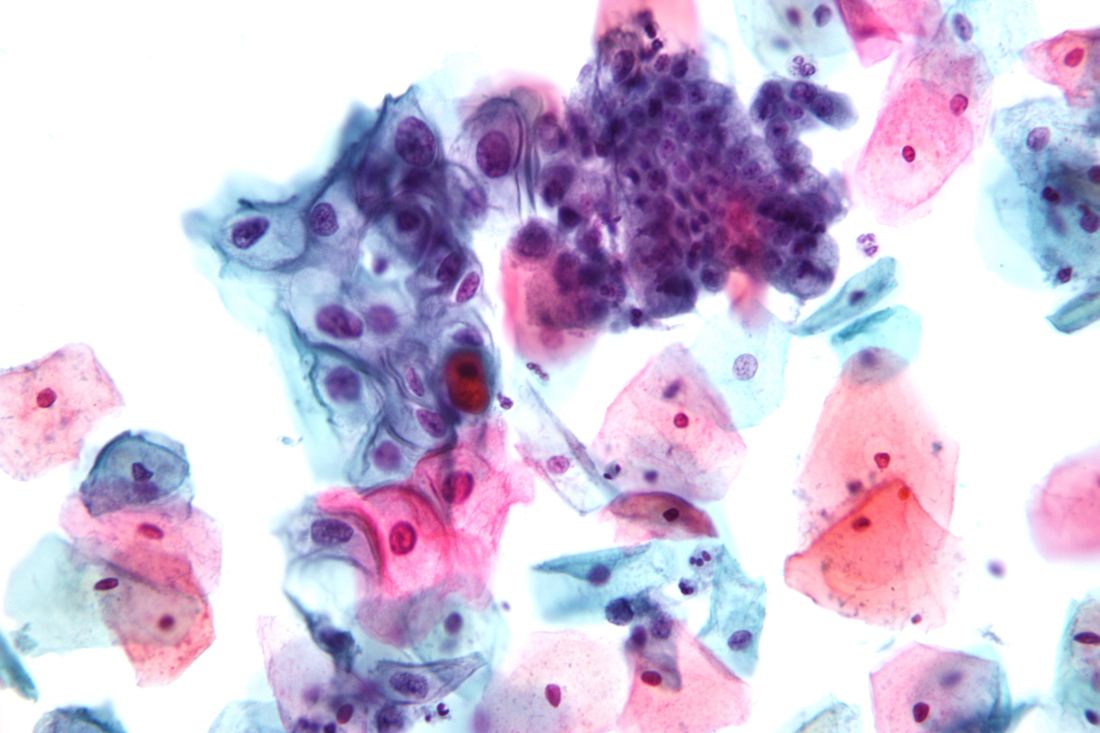

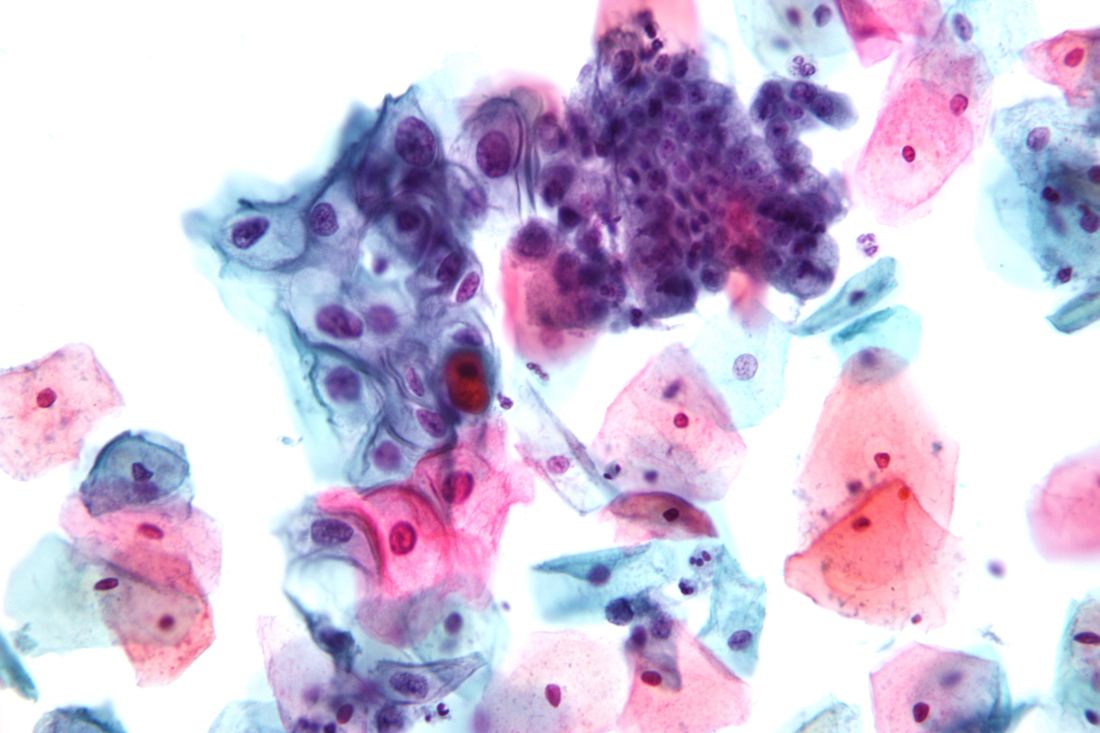

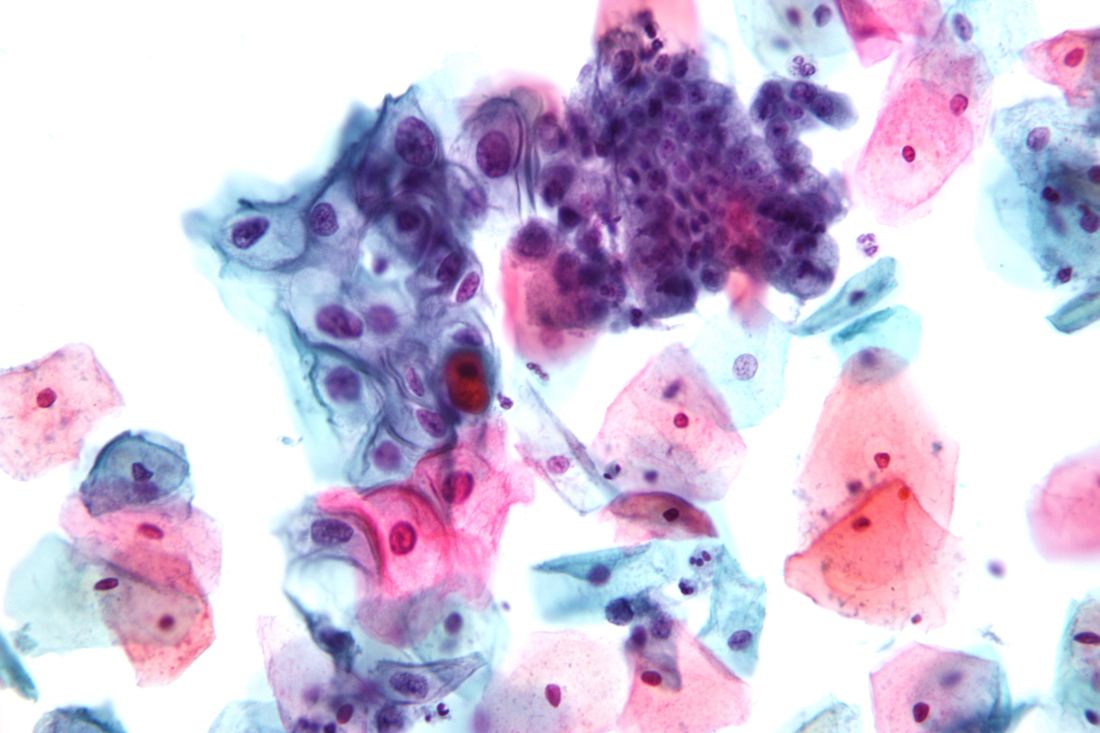

USPSTF backs away from cotesting in cervical cancer screening

Women aged 30-65 years should be offered a choice between two cervical cancer screening methods, according to draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The recommendations were released on Sept. 12.

The Task Force continues to recommend that women in their 20s be screened every 3 years via cervical cytology, but in a change from the 2012 recommendations, the researchers now advise clinicians to offer women aged 30-65 years a choice of either cytology every 3 years or the high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) test every 5 years as a method of screening for cervical cancer. Cotesting is no longer recommended.

Offering women aged 30-65 years a screening choice received an A recommendation. The draft retains the previous Task Force position and D recommendation against cervical cancer screening for certain groups, including women younger than 21 years, women aged 65 and older with a history of screening and a low risk of cervical cancer, and women who have had a hysterectomy.

The USPSTF based the draft recommendations in part on a review of four randomized, controlled trials of cotesting hrHPV and cytology that included more than 130,000 women.

“Modeling found that cotesting does not offer any benefit in terms of cancer reduction or life-years gained over hrHPV testing alone but increases the number of tests and procedures per each cancer case averted,” the Task Force members noted in the draft recommendation statement. “Therefore, the USPSTF concluded that there is convincing evidence that screening with either cytology alone or hrHPV testing alone provides substantial benefit and is preferable to cotesting” in otherwise healthy women aged 30-65 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The USPSTF draft recommendations do not apply to women at increased risk for cervical cancer, including those with compromised immune systems or those who have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3.

The draft recommendations are available online for public comment from Sept. 12 through Oct. 9, 2017, at the USPSTF website, www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Women aged 30-65 years should be offered a choice between two cervical cancer screening methods, according to draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The recommendations were released on Sept. 12.

The Task Force continues to recommend that women in their 20s be screened every 3 years via cervical cytology, but in a change from the 2012 recommendations, the researchers now advise clinicians to offer women aged 30-65 years a choice of either cytology every 3 years or the high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) test every 5 years as a method of screening for cervical cancer. Cotesting is no longer recommended.

Offering women aged 30-65 years a screening choice received an A recommendation. The draft retains the previous Task Force position and D recommendation against cervical cancer screening for certain groups, including women younger than 21 years, women aged 65 and older with a history of screening and a low risk of cervical cancer, and women who have had a hysterectomy.

The USPSTF based the draft recommendations in part on a review of four randomized, controlled trials of cotesting hrHPV and cytology that included more than 130,000 women.

“Modeling found that cotesting does not offer any benefit in terms of cancer reduction or life-years gained over hrHPV testing alone but increases the number of tests and procedures per each cancer case averted,” the Task Force members noted in the draft recommendation statement. “Therefore, the USPSTF concluded that there is convincing evidence that screening with either cytology alone or hrHPV testing alone provides substantial benefit and is preferable to cotesting” in otherwise healthy women aged 30-65 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The USPSTF draft recommendations do not apply to women at increased risk for cervical cancer, including those with compromised immune systems or those who have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3.

The draft recommendations are available online for public comment from Sept. 12 through Oct. 9, 2017, at the USPSTF website, www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Women aged 30-65 years should be offered a choice between two cervical cancer screening methods, according to draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The recommendations were released on Sept. 12.

The Task Force continues to recommend that women in their 20s be screened every 3 years via cervical cytology, but in a change from the 2012 recommendations, the researchers now advise clinicians to offer women aged 30-65 years a choice of either cytology every 3 years or the high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) test every 5 years as a method of screening for cervical cancer. Cotesting is no longer recommended.

Offering women aged 30-65 years a screening choice received an A recommendation. The draft retains the previous Task Force position and D recommendation against cervical cancer screening for certain groups, including women younger than 21 years, women aged 65 and older with a history of screening and a low risk of cervical cancer, and women who have had a hysterectomy.

The USPSTF based the draft recommendations in part on a review of four randomized, controlled trials of cotesting hrHPV and cytology that included more than 130,000 women.

“Modeling found that cotesting does not offer any benefit in terms of cancer reduction or life-years gained over hrHPV testing alone but increases the number of tests and procedures per each cancer case averted,” the Task Force members noted in the draft recommendation statement. “Therefore, the USPSTF concluded that there is convincing evidence that screening with either cytology alone or hrHPV testing alone provides substantial benefit and is preferable to cotesting” in otherwise healthy women aged 30-65 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The USPSTF draft recommendations do not apply to women at increased risk for cervical cancer, including those with compromised immune systems or those who have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3.

The draft recommendations are available online for public comment from Sept. 12 through Oct. 9, 2017, at the USPSTF website, www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

ASCO issues guideline on communication with patients

Recommendations for improved communication between oncologists and their patients are the focus of a new guideline issued by a panel convened by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The guideline recommends that oncologists establish care goals with each patient, address the costs of care, and initiate discussion of end-of-life preferences early in the course of incurable disease.

Patients also should be made aware of all treatment options, which may include clinical trials and, for certain patients, palliative care alone, the panel recommended.

The ASCO Expert Panel included medical oncologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and experts in hospice and palliative medicine, communication skills, health disparities, and advocacy. Their consensus-based, patient-clinician communication guideline drew on the panel’s systematic evaluation of guidelines, reviews and meta-analyses, and randomized, controlled trials published from 2006 through Oct. 1, 2016.

More specifics on the guideline are available here and feedback can be provided at asco.org/guidelineswiki.

Dr. Gilligan of the Taussig Cancer Institute and the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication, Cleveland Clinic, disclosed support from WellPoint; other panel members disclosed various consultancy roles or funding from pharmaceutical companies and CVS Health.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Recommendations for improved communication between oncologists and their patients are the focus of a new guideline issued by a panel convened by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The guideline recommends that oncologists establish care goals with each patient, address the costs of care, and initiate discussion of end-of-life preferences early in the course of incurable disease.

Patients also should be made aware of all treatment options, which may include clinical trials and, for certain patients, palliative care alone, the panel recommended.

The ASCO Expert Panel included medical oncologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and experts in hospice and palliative medicine, communication skills, health disparities, and advocacy. Their consensus-based, patient-clinician communication guideline drew on the panel’s systematic evaluation of guidelines, reviews and meta-analyses, and randomized, controlled trials published from 2006 through Oct. 1, 2016.

More specifics on the guideline are available here and feedback can be provided at asco.org/guidelineswiki.

Dr. Gilligan of the Taussig Cancer Institute and the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication, Cleveland Clinic, disclosed support from WellPoint; other panel members disclosed various consultancy roles or funding from pharmaceutical companies and CVS Health.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Recommendations for improved communication between oncologists and their patients are the focus of a new guideline issued by a panel convened by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The guideline recommends that oncologists establish care goals with each patient, address the costs of care, and initiate discussion of end-of-life preferences early in the course of incurable disease.

Patients also should be made aware of all treatment options, which may include clinical trials and, for certain patients, palliative care alone, the panel recommended.

The ASCO Expert Panel included medical oncologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and experts in hospice and palliative medicine, communication skills, health disparities, and advocacy. Their consensus-based, patient-clinician communication guideline drew on the panel’s systematic evaluation of guidelines, reviews and meta-analyses, and randomized, controlled trials published from 2006 through Oct. 1, 2016.

More specifics on the guideline are available here and feedback can be provided at asco.org/guidelineswiki.

Dr. Gilligan of the Taussig Cancer Institute and the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication, Cleveland Clinic, disclosed support from WellPoint; other panel members disclosed various consultancy roles or funding from pharmaceutical companies and CVS Health.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

New recommendations tout biosimilars for rheumatologic diseases

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.

“Treatment with biological agents has dramatically improved the outcome for patients with inflammatory diseases. However, the high cost of these medications has limited access for many patients,” Jonathan Kay, MD, of UMass Memorial Medical Center and the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and his colleagues wrote on behalf of the Task Force on the Use of Biosimilars to Treat Rheumatological Diseases. Biosimilars of agents no longer protected by patent allow for increased availability at lower costs, they noted. In the European Union, the United States, Japan, and other countries, biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and rituximab have been approved, and those for which the bio-originator is no longer protected by patent have been marketed.

The task force, convened in 2016 to address the matter at an international level, included 25 experts from Europe, Japan, and the United States, including 17 rheumatologists, a rheumatologist/regulator, a dermatologist, a gastroenterologist, 2 pharmacologists, 2 patients, and a research fellow. The task force identified five overarching principles and made eight specific recommendations, based on expert opinion and an extensive literature review that yielded 29 relevant full-text papers and 20 relevant abstracts from the 2015 and 2016 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism annual meetings (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211937).

“This statement was intended both to guide clinicians and to serve as a framework for future educational efforts,” they wrote.

The experts based all five overarching principles for the use of biosimilars on level 5, grade D evidence, indicating that they were derived mainly from expert opinion. They determined that:

- Treatment of rheumatic diseases is based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their rheumatologists.

- The contextual aspects of the health care system should be taken into consideration when treatment decisions are made.

- A biosimilar, as approved by authorities in a highly regulated area, is neither better nor worse in efficacy and is not inferior in safety to its bio-originator.

- Patients and health care providers should be informed about the nature of biosimilars, their approval process, and their safety and efficacy.

- Harmonized methods should be established to obtain reliable pharmacovigilance data, including traceability, about both biosimilars and bio-originators.

These principles represent the key issues regarding biosimilars as identified by the task force. As for the specific recommendations, the task force agreed that:

1. The availability of biosimilars must significantly lower the cost of treating an individual patient and increase access to optimal therapy for all patients with rheumatic diseases (level 5, grade D evidence).

2. Approved biosimilars can be used to treat appropriate patients in the same way as their bio-originators (level 1b, grade A evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual randomized, controlled trial and that the level 1 evidence is consistent).

3. Antidrug antibodies to biosimilars need not be measured in clinical practice as no significant differences have been detected between biosimilars and their bio-originators (level 2b, grade B evidence, indicating that the recommendation is based on an individual cohort study/low-quality randomized, controlled trial and consistent level 2 or 3 evidence).

4. Relevant preclinical and phase 1 data on a biosimilar should be available when phase 3 data are published (level 5, grade D evidence).

5. Confirmation of efficacy and safety in a single indication is sufficient for extrapolation to other diseases for which the bio-originator has been approved because biosimilars are equivalent in physiochemical, functional, and pharmacokinetic properties to the bio-originator (level 5, grade D evidence).

6. Available evidence suggests that a single switch from a bio-originator to one of its biosimilars is safe and effective; there is no reason to expect a different clinical outcome. However, patient perspectives must be considered (level 1b, grade A evidence).

7. Multiple switching between biosimilars and their bio-originators or other biosimilars should be assessed in registries (level 5, grade D evidence).

8. No switch to or among biosimilars should be initiated without the prior awareness of the patient and the treating health care provider (level 5, grade D evidence).

Differing opinions about the use of biosimilars as published by various subspecialty organizations highlight a lack of confidence among many clinicians with respect to appropriate use of the products, but that is changing amid a rapidly growing body of evidence, the task force said. The group achieved a high level of agreement about both the evaluation of biosimilars and their use to treat rheumatologic diseases, reaching 100% consensus for six of the recommendations and 91% and 96% for the other two.

“Data available as of December 2016 support the use of biosimilars by rheumatologists to encourage a fair and competitive market for biologics. Biosimilars now provide an opportunity to expand access to effective but expensive medications, increasing the number of available treatment choices and helping to control rapidly increasing drug expenditures,” they concluded.

The task force’s work was funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen. Dr. Kay and his coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, many of which are developing biosimilars.

The available evidence is sufficient to support switching appropriate patients with rheumatologic diseases from a bio-originator agent to an approved biosimilar agent, according to new consensus-based recommendations from an international multidisciplinary task force.