User login

Is anatomy destiny? Not according to GxE!

The long-held dogma that “anatomy is destiny” is fraying at the edges. The traditional nature vs nurture debate has also undergone a major transformation into a gene-by-environment interaction, abbreviated as GxE in the medical literature.1,2 This is as true for psychiatric brain disorders as for any other medical illness.

The pessimistic determinism of “anatomy is destiny” has given way to a much more optimistic perspective, especially for the most plastic of all organs, the human brain. While genes are essential to construct one’s anatomy, environmental factors can significantly modulate gene expression. A person’s life experiences, good or bad, can wield a lasting influence on one’s brain structure and function, often transcending what is coded by the genome. For the mind, its thoughts, emotions, and cognition, the neurogenetic “tyranny” can be curbed or modified by one’s experiences. This epigenetic process is alive and well and known to be mediated by DNA methylation and histone modifications.

Consider the following examples of how genes are not the sole determinants of one’s mental health:

- A landmark study conducted in New Zealand3 followed a cohort of 847 individuals from age 3 to 26. Researchers recorded stressful life events for each participant, including romantic breakups, grief, medical illness, or employment problems, between age 21 and 26. Participants were evaluated for depressive episodes and hospitalizations and their genes tested for whether each individual carried the short (S) or long (L) allele of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene. They found that when life stresses occurred, the probability of depression was much higher among the subgroup who were SS homozygous than among the LL homozygous subgroup. Thus, the genetic vulnerability to depression did not manifest itself unless adverse environmental events occurred. This is a classic example of GxE interaction, where genes alone are insufficient to produce a psychiatric disorder without environmental events interacting with them and triggering the psychopathology.

- In the same cohort described above, investigators showed that some children who were abused at an early age developed antisocial behavior as adults, while others did not.4 They discovered that a high expression of a polymorphism in the gene that codes for monoamine oxidase A had a protective effect that decreased the likelihood of developing antisocial traits in children who experienced trauma. In this case, the life experience failed to worsen a child’s behavior in the presence of elevated levels of a genetically determined protective enzyme.

- Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by numerous genetic factors (risk genes, copy number variants, and de novo mutations) and a wide variety of perinatal complications. Concordance for schizophrenia in monozygotic twins who have identical genes is only 50%, not 100% as would be expected.5 Obviously, nongenetic factors during fetal life must play a role in disrupting the neurodevelopment of the affected twin, but not in the healthy twin. Examples of such factors may include differential distribution of blood during fetal life, leading to low birthweight and hypoplastic brain volume in the affected twin. It may also be due to labor complications, where one twin has an uneventful vaginal delivery while the other experiences hypoxia, a brain insult, due to a complicated breech delivery. Thus, despite having the same genes, the postnatal outcome in a discordant monozygotic twin pair diverges dramatically.

- A recent study6 identified somatic mutations in monozygotic twins discordant for psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and delusional disorder. Such somatic mutations have also been found in Van der Woude syndrome, which includes cleft palate. However, skillful surgeons can repair the cleft palate and allow the affected twin to have a normal facial appearance and oral functions, offsetting the abnormal genetic code.

- A monozygotic twin pair (one of whom was a patient of mine) born to a mother with bipolar disorder and adopted at birth by different families developed bipolar disorder due to genetic transmission, but eventually had very different outcomes. One twin was promptly and successfully treated with lithium at the first manic episode and became a successful teacher and author, while his twin did not receive treatment, became addicted to drugs, was repeatedly incarcerated for assaultive behavior, and later completed suicide at a young age. The appropriate environment and experiences of a person who inherits a psychiatric disorder can dramatically alter the prognosis for the better.

The GxE neurobiological equation is a central feature in many of our patients. As clinicians, we can modulate the patient’s environment by providing timely therapeutic biopsychosocial interventions to our patient to catalyze the GxE equation and veer it towards health, resilience, and wellness. Psychiatric practice can effectively help our patients overcome their genetically and neurobiologically driven maladaptive behavior and enable them to recover from the ravages of neuropsychiatric illness. Thus, psychiatric care represents the ultimate “E” that can interact with and modulate the “G” and effectively demonstrate that anatomy is not destiny.

1. Ridley M. Nature via nurture: genes, experience and what makes us human. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 2003.

2. Rutter M. Genes and behavior: nature–nurture interplay explained. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

3. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301(5631):386-389.

4. Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297(5582):851-854.

5. Stabenau JR, Pollin W. Heredity and environment in schizophrenia, revisited. The contribution of twin and high-risk studies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181(5):290-297.

6. Nishioka M, Bundo M, Ueda J, et al. Identification of somatic mutations in monozygotic twins discordant for psychiatric disorders. NPJ Schizophr. 2018;4(1):7.

The long-held dogma that “anatomy is destiny” is fraying at the edges. The traditional nature vs nurture debate has also undergone a major transformation into a gene-by-environment interaction, abbreviated as GxE in the medical literature.1,2 This is as true for psychiatric brain disorders as for any other medical illness.

The pessimistic determinism of “anatomy is destiny” has given way to a much more optimistic perspective, especially for the most plastic of all organs, the human brain. While genes are essential to construct one’s anatomy, environmental factors can significantly modulate gene expression. A person’s life experiences, good or bad, can wield a lasting influence on one’s brain structure and function, often transcending what is coded by the genome. For the mind, its thoughts, emotions, and cognition, the neurogenetic “tyranny” can be curbed or modified by one’s experiences. This epigenetic process is alive and well and known to be mediated by DNA methylation and histone modifications.

Consider the following examples of how genes are not the sole determinants of one’s mental health:

- A landmark study conducted in New Zealand3 followed a cohort of 847 individuals from age 3 to 26. Researchers recorded stressful life events for each participant, including romantic breakups, grief, medical illness, or employment problems, between age 21 and 26. Participants were evaluated for depressive episodes and hospitalizations and their genes tested for whether each individual carried the short (S) or long (L) allele of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene. They found that when life stresses occurred, the probability of depression was much higher among the subgroup who were SS homozygous than among the LL homozygous subgroup. Thus, the genetic vulnerability to depression did not manifest itself unless adverse environmental events occurred. This is a classic example of GxE interaction, where genes alone are insufficient to produce a psychiatric disorder without environmental events interacting with them and triggering the psychopathology.

- In the same cohort described above, investigators showed that some children who were abused at an early age developed antisocial behavior as adults, while others did not.4 They discovered that a high expression of a polymorphism in the gene that codes for monoamine oxidase A had a protective effect that decreased the likelihood of developing antisocial traits in children who experienced trauma. In this case, the life experience failed to worsen a child’s behavior in the presence of elevated levels of a genetically determined protective enzyme.

- Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by numerous genetic factors (risk genes, copy number variants, and de novo mutations) and a wide variety of perinatal complications. Concordance for schizophrenia in monozygotic twins who have identical genes is only 50%, not 100% as would be expected.5 Obviously, nongenetic factors during fetal life must play a role in disrupting the neurodevelopment of the affected twin, but not in the healthy twin. Examples of such factors may include differential distribution of blood during fetal life, leading to low birthweight and hypoplastic brain volume in the affected twin. It may also be due to labor complications, where one twin has an uneventful vaginal delivery while the other experiences hypoxia, a brain insult, due to a complicated breech delivery. Thus, despite having the same genes, the postnatal outcome in a discordant monozygotic twin pair diverges dramatically.

- A recent study6 identified somatic mutations in monozygotic twins discordant for psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and delusional disorder. Such somatic mutations have also been found in Van der Woude syndrome, which includes cleft palate. However, skillful surgeons can repair the cleft palate and allow the affected twin to have a normal facial appearance and oral functions, offsetting the abnormal genetic code.

- A monozygotic twin pair (one of whom was a patient of mine) born to a mother with bipolar disorder and adopted at birth by different families developed bipolar disorder due to genetic transmission, but eventually had very different outcomes. One twin was promptly and successfully treated with lithium at the first manic episode and became a successful teacher and author, while his twin did not receive treatment, became addicted to drugs, was repeatedly incarcerated for assaultive behavior, and later completed suicide at a young age. The appropriate environment and experiences of a person who inherits a psychiatric disorder can dramatically alter the prognosis for the better.

The GxE neurobiological equation is a central feature in many of our patients. As clinicians, we can modulate the patient’s environment by providing timely therapeutic biopsychosocial interventions to our patient to catalyze the GxE equation and veer it towards health, resilience, and wellness. Psychiatric practice can effectively help our patients overcome their genetically and neurobiologically driven maladaptive behavior and enable them to recover from the ravages of neuropsychiatric illness. Thus, psychiatric care represents the ultimate “E” that can interact with and modulate the “G” and effectively demonstrate that anatomy is not destiny.

The long-held dogma that “anatomy is destiny” is fraying at the edges. The traditional nature vs nurture debate has also undergone a major transformation into a gene-by-environment interaction, abbreviated as GxE in the medical literature.1,2 This is as true for psychiatric brain disorders as for any other medical illness.

The pessimistic determinism of “anatomy is destiny” has given way to a much more optimistic perspective, especially for the most plastic of all organs, the human brain. While genes are essential to construct one’s anatomy, environmental factors can significantly modulate gene expression. A person’s life experiences, good or bad, can wield a lasting influence on one’s brain structure and function, often transcending what is coded by the genome. For the mind, its thoughts, emotions, and cognition, the neurogenetic “tyranny” can be curbed or modified by one’s experiences. This epigenetic process is alive and well and known to be mediated by DNA methylation and histone modifications.

Consider the following examples of how genes are not the sole determinants of one’s mental health:

- A landmark study conducted in New Zealand3 followed a cohort of 847 individuals from age 3 to 26. Researchers recorded stressful life events for each participant, including romantic breakups, grief, medical illness, or employment problems, between age 21 and 26. Participants were evaluated for depressive episodes and hospitalizations and their genes tested for whether each individual carried the short (S) or long (L) allele of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene. They found that when life stresses occurred, the probability of depression was much higher among the subgroup who were SS homozygous than among the LL homozygous subgroup. Thus, the genetic vulnerability to depression did not manifest itself unless adverse environmental events occurred. This is a classic example of GxE interaction, where genes alone are insufficient to produce a psychiatric disorder without environmental events interacting with them and triggering the psychopathology.

- In the same cohort described above, investigators showed that some children who were abused at an early age developed antisocial behavior as adults, while others did not.4 They discovered that a high expression of a polymorphism in the gene that codes for monoamine oxidase A had a protective effect that decreased the likelihood of developing antisocial traits in children who experienced trauma. In this case, the life experience failed to worsen a child’s behavior in the presence of elevated levels of a genetically determined protective enzyme.

- Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by numerous genetic factors (risk genes, copy number variants, and de novo mutations) and a wide variety of perinatal complications. Concordance for schizophrenia in monozygotic twins who have identical genes is only 50%, not 100% as would be expected.5 Obviously, nongenetic factors during fetal life must play a role in disrupting the neurodevelopment of the affected twin, but not in the healthy twin. Examples of such factors may include differential distribution of blood during fetal life, leading to low birthweight and hypoplastic brain volume in the affected twin. It may also be due to labor complications, where one twin has an uneventful vaginal delivery while the other experiences hypoxia, a brain insult, due to a complicated breech delivery. Thus, despite having the same genes, the postnatal outcome in a discordant monozygotic twin pair diverges dramatically.

- A recent study6 identified somatic mutations in monozygotic twins discordant for psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and delusional disorder. Such somatic mutations have also been found in Van der Woude syndrome, which includes cleft palate. However, skillful surgeons can repair the cleft palate and allow the affected twin to have a normal facial appearance and oral functions, offsetting the abnormal genetic code.

- A monozygotic twin pair (one of whom was a patient of mine) born to a mother with bipolar disorder and adopted at birth by different families developed bipolar disorder due to genetic transmission, but eventually had very different outcomes. One twin was promptly and successfully treated with lithium at the first manic episode and became a successful teacher and author, while his twin did not receive treatment, became addicted to drugs, was repeatedly incarcerated for assaultive behavior, and later completed suicide at a young age. The appropriate environment and experiences of a person who inherits a psychiatric disorder can dramatically alter the prognosis for the better.

The GxE neurobiological equation is a central feature in many of our patients. As clinicians, we can modulate the patient’s environment by providing timely therapeutic biopsychosocial interventions to our patient to catalyze the GxE equation and veer it towards health, resilience, and wellness. Psychiatric practice can effectively help our patients overcome their genetically and neurobiologically driven maladaptive behavior and enable them to recover from the ravages of neuropsychiatric illness. Thus, psychiatric care represents the ultimate “E” that can interact with and modulate the “G” and effectively demonstrate that anatomy is not destiny.

1. Ridley M. Nature via nurture: genes, experience and what makes us human. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 2003.

2. Rutter M. Genes and behavior: nature–nurture interplay explained. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

3. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301(5631):386-389.

4. Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297(5582):851-854.

5. Stabenau JR, Pollin W. Heredity and environment in schizophrenia, revisited. The contribution of twin and high-risk studies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181(5):290-297.

6. Nishioka M, Bundo M, Ueda J, et al. Identification of somatic mutations in monozygotic twins discordant for psychiatric disorders. NPJ Schizophr. 2018;4(1):7.

1. Ridley M. Nature via nurture: genes, experience and what makes us human. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 2003.

2. Rutter M. Genes and behavior: nature–nurture interplay explained. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

3. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301(5631):386-389.

4. Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297(5582):851-854.

5. Stabenau JR, Pollin W. Heredity and environment in schizophrenia, revisited. The contribution of twin and high-risk studies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181(5):290-297.

6. Nishioka M, Bundo M, Ueda J, et al. Identification of somatic mutations in monozygotic twins discordant for psychiatric disorders. NPJ Schizophr. 2018;4(1):7.

Delivering bad news in obstetric practice

Obstetrics is a field filled with joyful experiences highlighted by pregnancy, childbirth, and the growth of healthy families. The field is also filled with many experiences that are sorrowful, including failure to conceive after infertility treatment, miscarriage, ultrasound-detected fetal anomalies, fetuses with genetic problems, fetal and neonatal demise, extremely premature birth, and birth injury. For decades oncologists have evolved their approach to discussing bad news with cancer patients. In the distant past, oncologists often kept a cancer diagnosis from the patient, preferring to spare them the stress of the news. In the modern era of transparency, however, oncologists now uniformly strive to keep patients informed of their situation and have adopted structured approaches to delivering bad news. An adverse pregnancy outcome such as a miscarriage or fetal loss may trigger emotional responses as intense as those experienced by a person hearing about a cancer diagnosis. Women who have recently experienced a miscarriage report emotional responses ranging from “a little disappointed” to “in shock” and “for it to be taken away was crushing.”1 As obstetricians, we can advance our practice by adopting a structured approach to delivering bad news, building on the lessons from cancer medicine. Improving the quality of our communication about adverse pregnancy events will reduce emotional distress and enable patients and families to more effectively cope with challenging situations.

Communicating bad news: The facts, the emotional response, and the impact on identity

Clinicians need to be cognizant that a conversation about bad news is 3 interwoven conversations that involve facts, emotional responses, and an altered self-identity. In addition to communicating the facts of the event in clear language, clinicians need to simultaneously monitor and manage the emotional responses to the adverse event and the impact on the participants’ sense of self.2 Clinicians are steeped in scientific tradition and method, and as experts we are naturally drawn to a discussion of the facts.

However, a discussion about bad news is highly likely to trigger an emotional response in the patient and the clinician. For example, when a clinician tells the patient about delivery events that resulted in an unexpected newborn injury, the patient may become angry and the clinician may be fearful, anxious, and defensive. Managing the emotions of all participants in the conversation is important for an optimal outcome.

An adverse event also may cause those involved to think about their self-identity. A key feature of bad news is that it alters patients’ expectations about their future, juxtaposing the reality of their outcome with the preferable outcome that may have been. Following a stillbirth during her first pregnancy the patient may be wondering, “Will I ever be a mother?”, “Did I cause the loss?”, and “Does all life end in death?” A traumatic event also may impact the self-identity of the clinician. Following a delivery where the newborn was injured, the clinician may be wondering, “Am I a good or bad clinician?”, “Did I do something wrong?”, “Is it time for me to retire from obstetrical practice?”

Following an adverse pregnancy outcome some patients are consumed with intense grief. This may require the patient and her family to move through a series of emotions (similar to those who receive a new diagnosis of cancer), including denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Responses to grief

Kubler-Ross identified these 5 psychological coping mechanisms that are often used by people experiencing grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.3 The goal of the clinician is to help grieving patients move through these stages in an appropriate fashion and not get stuck in the stages of denial, anger, and/or depression. Following a difficult pregnancy some patients and their family members become stuck in a state dominated by anger, rage, and resentment. This is fertile ground for the growth of a professional liability case. Denial and anger are adaptive short-term defenses to protecting self-identity. In time, most people engage in more constructive responses, accept the adverse event, and plan for the future. Kubler-Ross observed that hope helps people survive through a time of great suffering and is present throughout the response to grief. Clinicians can play an important role in ensuring that a flame of hope is kept burning throughout the process of responding to and grieving bad outcomes.

A structured approach to delivering bad news: SPIKES

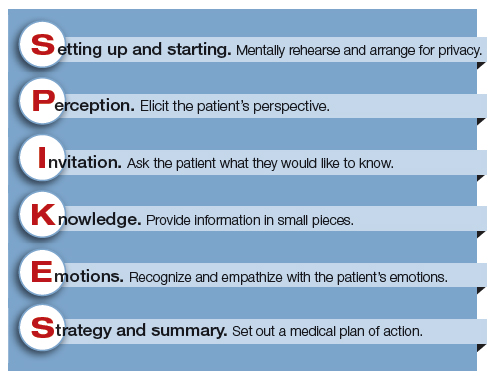

Dr. Robert Buckman, an oncologist, has proposed using a structured approach, SPIKES, to guide conversations focused on delivering bad news.4–6 SPIKES is focused on trying to deeply understand the patient’s level of knowledge, emotions, and perspective before providing medical information and support. SPIKES consists of 6 key steps.

1. Setting up and starting. Mentally rehearse and arrange for privacy. Make sure the patient’s support people are present. Sit down, use open body language, eye contact, and/or touch to make a connection with the patient. Create room for a dialogue by using open-ended questions, silent pauses, listening first, and encouraging the patient to provide their perspective.

2. Perception. Elicit the patient’s perspective. Assess what the patient believes and feels. Assess vocabulary and comprehension.

3. Invitation. Ask the patient what they would like to know. Obtain permission to share knowledge.

4. Knowledge. Provide information in small pieces, always checking back on the patient’s understanding. Use plain language that aligns with the patient’s vocabulary and understanding.

5. Emotions. Explore, explicitly recognize, and empathize with the patient’s emotions.

6. Strategy and summary. Set out a medical plan of action. Express a commitment to be available for the patient as she embarks on the care plan. Arrange for a follow-up conversation.

Some studies have indicated that having a protocol such as SPIKES for delivering bad news helps clinicians to navigate this challenging process, which in turn improves patient satisfaction with disclosure.7 Simulation training focused on communicating bad news could be better utilized to help clinicians practice this skill, similar to the simulation exercises used to practice common clinical problems like hemorrhage and shoulder dystocia.8,9

Physician responses to bad outcomes

Over a career in clinical practice, physicians experience many bad outcomes that expose them to the contagion of sadness and grief. Despite this vicarious trauma, they must always present a professional persona, placing the patient’s needs above their own pain. Due to these experiences, clinicians may become isolated, depressed, and burned out. Drs. Michael and Enid Balint recognized the adverse effect of a lifetime of exposure to suffering and pain. They proposed that physicians could mitigate the trauma of these experiences by participating in small group meetings with a trained leader to discuss their most difficult clinical experiences in a confidential and supportive environment.10,11 By sharing clinical experiences, feelings, and stories with trusted colleagues, physicians can channel painful experiences into a greater understanding of the empathy and compassion needed to care for themselves, their colleagues, and patients. Clinical practice is invariably punctuated by occasional adverse outcomes necessitating that we effectively manage the process of delivering bad news, simultaneously caring for ourselves and our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Flink-Bochacki R, Hamm ME, Borrero S, Chen BA, Achilles SL, Chang JC. Family planning and counseling desires of women who have experienced miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):625-631.

- Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations. How to discuss what matters most. Penguin Books: New York, NY; 1999:9-10.

- Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. MacMillan: New York, NY; 1969.

- Buckman R. How to break bad news. A guide for health care professionals. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 1992.

- Buckman R. Practical plans for difficult conversations in medicine. Strategies that work in breaking bad news. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 2010.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312-319.

- Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, Stern D. Teaching students to break bad news. Am J Surg. 2001;182(1):20-23.

- Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: a review of strategies. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):107-117.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Pitman: London, England; 1957.

- Salinksky J. Balint groups and the Balint method. The Balint Society website. https://balint.co.uk/about/the-balint-method/. Accessed May 17, 2018.

Obstetrics is a field filled with joyful experiences highlighted by pregnancy, childbirth, and the growth of healthy families. The field is also filled with many experiences that are sorrowful, including failure to conceive after infertility treatment, miscarriage, ultrasound-detected fetal anomalies, fetuses with genetic problems, fetal and neonatal demise, extremely premature birth, and birth injury. For decades oncologists have evolved their approach to discussing bad news with cancer patients. In the distant past, oncologists often kept a cancer diagnosis from the patient, preferring to spare them the stress of the news. In the modern era of transparency, however, oncologists now uniformly strive to keep patients informed of their situation and have adopted structured approaches to delivering bad news. An adverse pregnancy outcome such as a miscarriage or fetal loss may trigger emotional responses as intense as those experienced by a person hearing about a cancer diagnosis. Women who have recently experienced a miscarriage report emotional responses ranging from “a little disappointed” to “in shock” and “for it to be taken away was crushing.”1 As obstetricians, we can advance our practice by adopting a structured approach to delivering bad news, building on the lessons from cancer medicine. Improving the quality of our communication about adverse pregnancy events will reduce emotional distress and enable patients and families to more effectively cope with challenging situations.

Communicating bad news: The facts, the emotional response, and the impact on identity

Clinicians need to be cognizant that a conversation about bad news is 3 interwoven conversations that involve facts, emotional responses, and an altered self-identity. In addition to communicating the facts of the event in clear language, clinicians need to simultaneously monitor and manage the emotional responses to the adverse event and the impact on the participants’ sense of self.2 Clinicians are steeped in scientific tradition and method, and as experts we are naturally drawn to a discussion of the facts.

However, a discussion about bad news is highly likely to trigger an emotional response in the patient and the clinician. For example, when a clinician tells the patient about delivery events that resulted in an unexpected newborn injury, the patient may become angry and the clinician may be fearful, anxious, and defensive. Managing the emotions of all participants in the conversation is important for an optimal outcome.

An adverse event also may cause those involved to think about their self-identity. A key feature of bad news is that it alters patients’ expectations about their future, juxtaposing the reality of their outcome with the preferable outcome that may have been. Following a stillbirth during her first pregnancy the patient may be wondering, “Will I ever be a mother?”, “Did I cause the loss?”, and “Does all life end in death?” A traumatic event also may impact the self-identity of the clinician. Following a delivery where the newborn was injured, the clinician may be wondering, “Am I a good or bad clinician?”, “Did I do something wrong?”, “Is it time for me to retire from obstetrical practice?”

Following an adverse pregnancy outcome some patients are consumed with intense grief. This may require the patient and her family to move through a series of emotions (similar to those who receive a new diagnosis of cancer), including denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Responses to grief

Kubler-Ross identified these 5 psychological coping mechanisms that are often used by people experiencing grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.3 The goal of the clinician is to help grieving patients move through these stages in an appropriate fashion and not get stuck in the stages of denial, anger, and/or depression. Following a difficult pregnancy some patients and their family members become stuck in a state dominated by anger, rage, and resentment. This is fertile ground for the growth of a professional liability case. Denial and anger are adaptive short-term defenses to protecting self-identity. In time, most people engage in more constructive responses, accept the adverse event, and plan for the future. Kubler-Ross observed that hope helps people survive through a time of great suffering and is present throughout the response to grief. Clinicians can play an important role in ensuring that a flame of hope is kept burning throughout the process of responding to and grieving bad outcomes.

A structured approach to delivering bad news: SPIKES

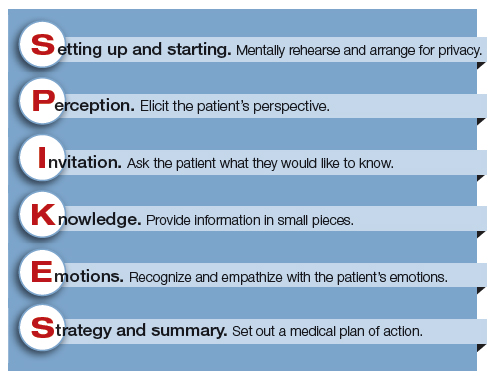

Dr. Robert Buckman, an oncologist, has proposed using a structured approach, SPIKES, to guide conversations focused on delivering bad news.4–6 SPIKES is focused on trying to deeply understand the patient’s level of knowledge, emotions, and perspective before providing medical information and support. SPIKES consists of 6 key steps.

1. Setting up and starting. Mentally rehearse and arrange for privacy. Make sure the patient’s support people are present. Sit down, use open body language, eye contact, and/or touch to make a connection with the patient. Create room for a dialogue by using open-ended questions, silent pauses, listening first, and encouraging the patient to provide their perspective.

2. Perception. Elicit the patient’s perspective. Assess what the patient believes and feels. Assess vocabulary and comprehension.

3. Invitation. Ask the patient what they would like to know. Obtain permission to share knowledge.

4. Knowledge. Provide information in small pieces, always checking back on the patient’s understanding. Use plain language that aligns with the patient’s vocabulary and understanding.

5. Emotions. Explore, explicitly recognize, and empathize with the patient’s emotions.

6. Strategy and summary. Set out a medical plan of action. Express a commitment to be available for the patient as she embarks on the care plan. Arrange for a follow-up conversation.

Some studies have indicated that having a protocol such as SPIKES for delivering bad news helps clinicians to navigate this challenging process, which in turn improves patient satisfaction with disclosure.7 Simulation training focused on communicating bad news could be better utilized to help clinicians practice this skill, similar to the simulation exercises used to practice common clinical problems like hemorrhage and shoulder dystocia.8,9

Physician responses to bad outcomes

Over a career in clinical practice, physicians experience many bad outcomes that expose them to the contagion of sadness and grief. Despite this vicarious trauma, they must always present a professional persona, placing the patient’s needs above their own pain. Due to these experiences, clinicians may become isolated, depressed, and burned out. Drs. Michael and Enid Balint recognized the adverse effect of a lifetime of exposure to suffering and pain. They proposed that physicians could mitigate the trauma of these experiences by participating in small group meetings with a trained leader to discuss their most difficult clinical experiences in a confidential and supportive environment.10,11 By sharing clinical experiences, feelings, and stories with trusted colleagues, physicians can channel painful experiences into a greater understanding of the empathy and compassion needed to care for themselves, their colleagues, and patients. Clinical practice is invariably punctuated by occasional adverse outcomes necessitating that we effectively manage the process of delivering bad news, simultaneously caring for ourselves and our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Obstetrics is a field filled with joyful experiences highlighted by pregnancy, childbirth, and the growth of healthy families. The field is also filled with many experiences that are sorrowful, including failure to conceive after infertility treatment, miscarriage, ultrasound-detected fetal anomalies, fetuses with genetic problems, fetal and neonatal demise, extremely premature birth, and birth injury. For decades oncologists have evolved their approach to discussing bad news with cancer patients. In the distant past, oncologists often kept a cancer diagnosis from the patient, preferring to spare them the stress of the news. In the modern era of transparency, however, oncologists now uniformly strive to keep patients informed of their situation and have adopted structured approaches to delivering bad news. An adverse pregnancy outcome such as a miscarriage or fetal loss may trigger emotional responses as intense as those experienced by a person hearing about a cancer diagnosis. Women who have recently experienced a miscarriage report emotional responses ranging from “a little disappointed” to “in shock” and “for it to be taken away was crushing.”1 As obstetricians, we can advance our practice by adopting a structured approach to delivering bad news, building on the lessons from cancer medicine. Improving the quality of our communication about adverse pregnancy events will reduce emotional distress and enable patients and families to more effectively cope with challenging situations.

Communicating bad news: The facts, the emotional response, and the impact on identity

Clinicians need to be cognizant that a conversation about bad news is 3 interwoven conversations that involve facts, emotional responses, and an altered self-identity. In addition to communicating the facts of the event in clear language, clinicians need to simultaneously monitor and manage the emotional responses to the adverse event and the impact on the participants’ sense of self.2 Clinicians are steeped in scientific tradition and method, and as experts we are naturally drawn to a discussion of the facts.

However, a discussion about bad news is highly likely to trigger an emotional response in the patient and the clinician. For example, when a clinician tells the patient about delivery events that resulted in an unexpected newborn injury, the patient may become angry and the clinician may be fearful, anxious, and defensive. Managing the emotions of all participants in the conversation is important for an optimal outcome.

An adverse event also may cause those involved to think about their self-identity. A key feature of bad news is that it alters patients’ expectations about their future, juxtaposing the reality of their outcome with the preferable outcome that may have been. Following a stillbirth during her first pregnancy the patient may be wondering, “Will I ever be a mother?”, “Did I cause the loss?”, and “Does all life end in death?” A traumatic event also may impact the self-identity of the clinician. Following a delivery where the newborn was injured, the clinician may be wondering, “Am I a good or bad clinician?”, “Did I do something wrong?”, “Is it time for me to retire from obstetrical practice?”

Following an adverse pregnancy outcome some patients are consumed with intense grief. This may require the patient and her family to move through a series of emotions (similar to those who receive a new diagnosis of cancer), including denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Responses to grief

Kubler-Ross identified these 5 psychological coping mechanisms that are often used by people experiencing grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.3 The goal of the clinician is to help grieving patients move through these stages in an appropriate fashion and not get stuck in the stages of denial, anger, and/or depression. Following a difficult pregnancy some patients and their family members become stuck in a state dominated by anger, rage, and resentment. This is fertile ground for the growth of a professional liability case. Denial and anger are adaptive short-term defenses to protecting self-identity. In time, most people engage in more constructive responses, accept the adverse event, and plan for the future. Kubler-Ross observed that hope helps people survive through a time of great suffering and is present throughout the response to grief. Clinicians can play an important role in ensuring that a flame of hope is kept burning throughout the process of responding to and grieving bad outcomes.

A structured approach to delivering bad news: SPIKES

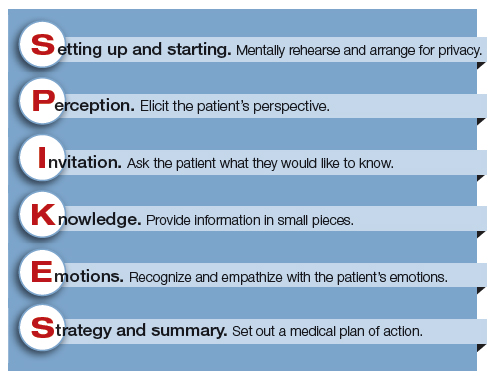

Dr. Robert Buckman, an oncologist, has proposed using a structured approach, SPIKES, to guide conversations focused on delivering bad news.4–6 SPIKES is focused on trying to deeply understand the patient’s level of knowledge, emotions, and perspective before providing medical information and support. SPIKES consists of 6 key steps.

1. Setting up and starting. Mentally rehearse and arrange for privacy. Make sure the patient’s support people are present. Sit down, use open body language, eye contact, and/or touch to make a connection with the patient. Create room for a dialogue by using open-ended questions, silent pauses, listening first, and encouraging the patient to provide their perspective.

2. Perception. Elicit the patient’s perspective. Assess what the patient believes and feels. Assess vocabulary and comprehension.

3. Invitation. Ask the patient what they would like to know. Obtain permission to share knowledge.

4. Knowledge. Provide information in small pieces, always checking back on the patient’s understanding. Use plain language that aligns with the patient’s vocabulary and understanding.

5. Emotions. Explore, explicitly recognize, and empathize with the patient’s emotions.

6. Strategy and summary. Set out a medical plan of action. Express a commitment to be available for the patient as she embarks on the care plan. Arrange for a follow-up conversation.

Some studies have indicated that having a protocol such as SPIKES for delivering bad news helps clinicians to navigate this challenging process, which in turn improves patient satisfaction with disclosure.7 Simulation training focused on communicating bad news could be better utilized to help clinicians practice this skill, similar to the simulation exercises used to practice common clinical problems like hemorrhage and shoulder dystocia.8,9

Physician responses to bad outcomes

Over a career in clinical practice, physicians experience many bad outcomes that expose them to the contagion of sadness and grief. Despite this vicarious trauma, they must always present a professional persona, placing the patient’s needs above their own pain. Due to these experiences, clinicians may become isolated, depressed, and burned out. Drs. Michael and Enid Balint recognized the adverse effect of a lifetime of exposure to suffering and pain. They proposed that physicians could mitigate the trauma of these experiences by participating in small group meetings with a trained leader to discuss their most difficult clinical experiences in a confidential and supportive environment.10,11 By sharing clinical experiences, feelings, and stories with trusted colleagues, physicians can channel painful experiences into a greater understanding of the empathy and compassion needed to care for themselves, their colleagues, and patients. Clinical practice is invariably punctuated by occasional adverse outcomes necessitating that we effectively manage the process of delivering bad news, simultaneously caring for ourselves and our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Flink-Bochacki R, Hamm ME, Borrero S, Chen BA, Achilles SL, Chang JC. Family planning and counseling desires of women who have experienced miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):625-631.

- Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations. How to discuss what matters most. Penguin Books: New York, NY; 1999:9-10.

- Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. MacMillan: New York, NY; 1969.

- Buckman R. How to break bad news. A guide for health care professionals. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 1992.

- Buckman R. Practical plans for difficult conversations in medicine. Strategies that work in breaking bad news. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 2010.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312-319.

- Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, Stern D. Teaching students to break bad news. Am J Surg. 2001;182(1):20-23.

- Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: a review of strategies. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):107-117.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Pitman: London, England; 1957.

- Salinksky J. Balint groups and the Balint method. The Balint Society website. https://balint.co.uk/about/the-balint-method/. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- Flink-Bochacki R, Hamm ME, Borrero S, Chen BA, Achilles SL, Chang JC. Family planning and counseling desires of women who have experienced miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):625-631.

- Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations. How to discuss what matters most. Penguin Books: New York, NY; 1999:9-10.

- Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. MacMillan: New York, NY; 1969.

- Buckman R. How to break bad news. A guide for health care professionals. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 1992.

- Buckman R. Practical plans for difficult conversations in medicine. Strategies that work in breaking bad news. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 2010.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312-319.

- Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, Stern D. Teaching students to break bad news. Am J Surg. 2001;182(1):20-23.

- Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: a review of strategies. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):107-117.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Pitman: London, England; 1957.

- Salinksky J. Balint groups and the Balint method. The Balint Society website. https://balint.co.uk/about/the-balint-method/. Accessed May 17, 2018.

Eleven on a scale of 1 to 10

I literally rode into the sunset recently as I finished my tour of duty as one of the Director examiners for the American Board of Surgery. I was heading out of St. Louis westward toward my home in Kansas. It was a 9-hour drive, which gave me plenty of time to reflect on the 6 years I shared the responsibility of administering the certifying exam known by most surgeons as “the oral exam.”

Over the last dozen years, Directors V. Suzanne Klimberg and Karen J. Brasel, along with former Executive Director Frank Lewis, a team of psychometricians at the Board, and members of the certification committee of the Board, worked tirelessly to create a testing instrument as fair and statistically sound as possible given the inherently qualitative exam. I believe they did a magnificent job. Gone are the legends of yesteryear where candidates were subjected to the whims of whatever crossed the mind of the examiners, including their prejudices about the “right” answer. The oral exam now represents a well-constructed survey of surgical judgment issues that have been thoroughly vetted.

Being an examiner for the orals means you arrive Sunday afternoon before the exams that are given over the next two and a half days. Each examiner undergoes an overview briefing on Sunday afternoon and then studies “the book” for that test’s content usually until late into the night. This book is an impressive document.

We arise around 0530 to attend a breakfast meeting, which includes breaking into our six-person teams and going over each question that will be given that day. At 0800, the first candidates for the first session walk into a room and meet the two surgeons who will make some of the most important decisions affecting that candidate’s career. If you rate the intensity of this moment on a scale of 1 to 10, this is an 11 for both candidates and examiners. No one in the room knows how it will turn out because every session has its own twists and turns. Everyone there wants to see a passing score, but the two examiners know that they must make a decision that is safe for the public and fair for the candidate.

Twelve exams are given per team per day except for the final day which has only six. So, each team examines 30 candidates over 3 days. I’ve opened a door and shaken the moist hand of 438 candidates. I’ve seen every sort of emotion during those sessions. I’ve had moments of great joy and times of profound sadness as candidates respond to the questions. I’ve always tried to be friendly, but just like surgery, it is a serious business and decisions have to be made. That means ignoring one’s hopes and acting on the best facts available at the moment. Most surgeons remember their oral examiners and what they were asked for a lifetime. I know I do.

I could write a book on this experience (I won’t, though). But as I reflect on my time as a Director, what stands out in my mind are the associate examiners with whom I’ve worked. These surgeons are invited to participate and receive no compensation. It’s 3 days out of their lives, and because they don’t give the exam as frequently as the Directors do, the amount of study and effort is greater for them. Each is selected because he or she is considered to be a thoughtful surgeon with high standards. These surgeons do this job because they care about quality in our profession.

Most of the associates I have worked with are far more accomplished than I. I was once paired with a renowned breast surgeon (okay, it was Kelly K. Hunt). My ego was at great risk because I knew how accomplished she was. But like all the other associates, she was gracious and hard working. We rarely work with another Director, but Anne G. Rizzo, who later became a Director, and I did an exam together. She was a dazzling questioner with very high standards. In other words, she was typical of the people I met. My first associate (also later a Director) was Reid Adams. He was great; I was nervous. My last associate was Marc L. Melcher, a transplant surgeon who asked penetrating questions in a calm manner. I wish I could name each of my associates and thank them for making my work so much better, for teaching me things I didn’t know, for deepening my own knowledge, and serving in a hard job with grace. This column can’t be that long, but you all know who you are. Thank you.

At the end of the day, I believe the oral exam to be a great thing for our profession. When you think about the number of patients potentially affected throughout a surgeon’s career, the impact of decisions made on the day of the exam can be enormous. Given that, over a 20-year career, a surgeon may operate on 25,000 patients, a summative check on a surgeon’s judgment and knowledge is important. Each year, the ABS adjudicates on some 1,100 surgeons. A single year’s set of surgeons over the following 20-year period translates into 27.5 million patients. I hope we never stop doing the orals because of cost, time, or convenience. The exam is just too important to our profession to risk forgoing this last, big step before a surgeon is presented to the world as “certified.”

I literally rode into the sunset recently as I finished my tour of duty as one of the Director examiners for the American Board of Surgery. I was heading out of St. Louis westward toward my home in Kansas. It was a 9-hour drive, which gave me plenty of time to reflect on the 6 years I shared the responsibility of administering the certifying exam known by most surgeons as “the oral exam.”

Over the last dozen years, Directors V. Suzanne Klimberg and Karen J. Brasel, along with former Executive Director Frank Lewis, a team of psychometricians at the Board, and members of the certification committee of the Board, worked tirelessly to create a testing instrument as fair and statistically sound as possible given the inherently qualitative exam. I believe they did a magnificent job. Gone are the legends of yesteryear where candidates were subjected to the whims of whatever crossed the mind of the examiners, including their prejudices about the “right” answer. The oral exam now represents a well-constructed survey of surgical judgment issues that have been thoroughly vetted.

Being an examiner for the orals means you arrive Sunday afternoon before the exams that are given over the next two and a half days. Each examiner undergoes an overview briefing on Sunday afternoon and then studies “the book” for that test’s content usually until late into the night. This book is an impressive document.

We arise around 0530 to attend a breakfast meeting, which includes breaking into our six-person teams and going over each question that will be given that day. At 0800, the first candidates for the first session walk into a room and meet the two surgeons who will make some of the most important decisions affecting that candidate’s career. If you rate the intensity of this moment on a scale of 1 to 10, this is an 11 for both candidates and examiners. No one in the room knows how it will turn out because every session has its own twists and turns. Everyone there wants to see a passing score, but the two examiners know that they must make a decision that is safe for the public and fair for the candidate.

Twelve exams are given per team per day except for the final day which has only six. So, each team examines 30 candidates over 3 days. I’ve opened a door and shaken the moist hand of 438 candidates. I’ve seen every sort of emotion during those sessions. I’ve had moments of great joy and times of profound sadness as candidates respond to the questions. I’ve always tried to be friendly, but just like surgery, it is a serious business and decisions have to be made. That means ignoring one’s hopes and acting on the best facts available at the moment. Most surgeons remember their oral examiners and what they were asked for a lifetime. I know I do.

I could write a book on this experience (I won’t, though). But as I reflect on my time as a Director, what stands out in my mind are the associate examiners with whom I’ve worked. These surgeons are invited to participate and receive no compensation. It’s 3 days out of their lives, and because they don’t give the exam as frequently as the Directors do, the amount of study and effort is greater for them. Each is selected because he or she is considered to be a thoughtful surgeon with high standards. These surgeons do this job because they care about quality in our profession.

Most of the associates I have worked with are far more accomplished than I. I was once paired with a renowned breast surgeon (okay, it was Kelly K. Hunt). My ego was at great risk because I knew how accomplished she was. But like all the other associates, she was gracious and hard working. We rarely work with another Director, but Anne G. Rizzo, who later became a Director, and I did an exam together. She was a dazzling questioner with very high standards. In other words, she was typical of the people I met. My first associate (also later a Director) was Reid Adams. He was great; I was nervous. My last associate was Marc L. Melcher, a transplant surgeon who asked penetrating questions in a calm manner. I wish I could name each of my associates and thank them for making my work so much better, for teaching me things I didn’t know, for deepening my own knowledge, and serving in a hard job with grace. This column can’t be that long, but you all know who you are. Thank you.

At the end of the day, I believe the oral exam to be a great thing for our profession. When you think about the number of patients potentially affected throughout a surgeon’s career, the impact of decisions made on the day of the exam can be enormous. Given that, over a 20-year career, a surgeon may operate on 25,000 patients, a summative check on a surgeon’s judgment and knowledge is important. Each year, the ABS adjudicates on some 1,100 surgeons. A single year’s set of surgeons over the following 20-year period translates into 27.5 million patients. I hope we never stop doing the orals because of cost, time, or convenience. The exam is just too important to our profession to risk forgoing this last, big step before a surgeon is presented to the world as “certified.”

I literally rode into the sunset recently as I finished my tour of duty as one of the Director examiners for the American Board of Surgery. I was heading out of St. Louis westward toward my home in Kansas. It was a 9-hour drive, which gave me plenty of time to reflect on the 6 years I shared the responsibility of administering the certifying exam known by most surgeons as “the oral exam.”

Over the last dozen years, Directors V. Suzanne Klimberg and Karen J. Brasel, along with former Executive Director Frank Lewis, a team of psychometricians at the Board, and members of the certification committee of the Board, worked tirelessly to create a testing instrument as fair and statistically sound as possible given the inherently qualitative exam. I believe they did a magnificent job. Gone are the legends of yesteryear where candidates were subjected to the whims of whatever crossed the mind of the examiners, including their prejudices about the “right” answer. The oral exam now represents a well-constructed survey of surgical judgment issues that have been thoroughly vetted.

Being an examiner for the orals means you arrive Sunday afternoon before the exams that are given over the next two and a half days. Each examiner undergoes an overview briefing on Sunday afternoon and then studies “the book” for that test’s content usually until late into the night. This book is an impressive document.

We arise around 0530 to attend a breakfast meeting, which includes breaking into our six-person teams and going over each question that will be given that day. At 0800, the first candidates for the first session walk into a room and meet the two surgeons who will make some of the most important decisions affecting that candidate’s career. If you rate the intensity of this moment on a scale of 1 to 10, this is an 11 for both candidates and examiners. No one in the room knows how it will turn out because every session has its own twists and turns. Everyone there wants to see a passing score, but the two examiners know that they must make a decision that is safe for the public and fair for the candidate.

Twelve exams are given per team per day except for the final day which has only six. So, each team examines 30 candidates over 3 days. I’ve opened a door and shaken the moist hand of 438 candidates. I’ve seen every sort of emotion during those sessions. I’ve had moments of great joy and times of profound sadness as candidates respond to the questions. I’ve always tried to be friendly, but just like surgery, it is a serious business and decisions have to be made. That means ignoring one’s hopes and acting on the best facts available at the moment. Most surgeons remember their oral examiners and what they were asked for a lifetime. I know I do.

I could write a book on this experience (I won’t, though). But as I reflect on my time as a Director, what stands out in my mind are the associate examiners with whom I’ve worked. These surgeons are invited to participate and receive no compensation. It’s 3 days out of their lives, and because they don’t give the exam as frequently as the Directors do, the amount of study and effort is greater for them. Each is selected because he or she is considered to be a thoughtful surgeon with high standards. These surgeons do this job because they care about quality in our profession.

Most of the associates I have worked with are far more accomplished than I. I was once paired with a renowned breast surgeon (okay, it was Kelly K. Hunt). My ego was at great risk because I knew how accomplished she was. But like all the other associates, she was gracious and hard working. We rarely work with another Director, but Anne G. Rizzo, who later became a Director, and I did an exam together. She was a dazzling questioner with very high standards. In other words, she was typical of the people I met. My first associate (also later a Director) was Reid Adams. He was great; I was nervous. My last associate was Marc L. Melcher, a transplant surgeon who asked penetrating questions in a calm manner. I wish I could name each of my associates and thank them for making my work so much better, for teaching me things I didn’t know, for deepening my own knowledge, and serving in a hard job with grace. This column can’t be that long, but you all know who you are. Thank you.

At the end of the day, I believe the oral exam to be a great thing for our profession. When you think about the number of patients potentially affected throughout a surgeon’s career, the impact of decisions made on the day of the exam can be enormous. Given that, over a 20-year career, a surgeon may operate on 25,000 patients, a summative check on a surgeon’s judgment and knowledge is important. Each year, the ABS adjudicates on some 1,100 surgeons. A single year’s set of surgeons over the following 20-year period translates into 27.5 million patients. I hope we never stop doing the orals because of cost, time, or convenience. The exam is just too important to our profession to risk forgoing this last, big step before a surgeon is presented to the world as “certified.”

Gender equity in surgery: It’s complicated

For most of my professional life I have avoided writing about gender inequity in the field of surgery – not because I believe it does not exist, but because the reasons it does exist are manifold and complicated.

To be sure, implicit and explicit bias remain important reasons why only a minority of female medical students still choose surgery as a career in 2018, why female surgeons still earn only 82% of the salary of their male counterparts, and why women occupy only 12% of the chairs in academic surgical departments in the United States. It has long been tempting to lay the blame for those inequities on a stereotypical macho surgical culture that prevailed as the 20th century came to a close. But the factors that perpetuate male/female imbalance in our profession are complicated and run deep in the psyches of both men and women. We are all products of our generations, our culture, upbringing, and environment – men as well as women. Correcting the imbalance requires much more than simply passing laws that require equitable pay or treatment.

I realized how deeply ingrained biases are in all of us while still in my surgical residency in the 1970s. On a rare occasion when neither my husband (also a surgical resident) nor I was on call, we had a dinner party with friends at our house. The telephone rang (no iPhones, just a land line), and I ran to answer our only telephone in another room. It was the hospital operator, who asked, “Is Dr. Deveney there?” Without thinking, I answered, “Just a moment, I’ll get him!” I had taken only three steps away from the phone when it occurred to me what I had just said. I turned back, picked up the phone, and asked, “Which Dr. Deveney were you looking for?”

If even I had been conditioned to think automatically of “doctor” being a man after all of my effort to earn a place in the ranks, was there any hope that equality could be achieved? When I finished my residency and was offered a surgery position at our VA, I asked no questions about salary or other particulars; I was simply grateful that I had been given a job.

That was 1978 – a different time, a different generation. Since then, women have made dramatic progress toward equity in our profession, as in many others. The support, mentoring, and consciousness-raising efforts of the Association of Women Surgeons (AWS) are responsible for much of this progress. The American College of Surgeons was very supportive of the AWS early on and continues to encourage female medical students to choose surgery as a career and to help the advancement of women into leadership roles in surgery. Many surgical residency programs have 50% women in their ranks; half of our residents in Oregon have been women for over a decade. Our program director is a woman, as are 28% of the faculty; not 50%, but definitely progress, since I was the lone woman on the faculty when I arrived in 1987.

Although women occupy only 12% of the surgical chairs in U.S. surgical departments, this number has soared in the past 2 years from 7 in 2016 to 21 this year after languishing in the low single digits since 1987, when the late Olga Jonasson, MD, FACS, became the first female chair at Ohio State University. And yet, women have not reached full equality with men across the United States in surgical training, leadership, or pay. Why not?

Multiple factors have played roles in impeding the progress of women in achieving equality in surgery. Traditional cultural expectations of male and female roles in society affect both genders as they grow up, even when their parents make deliberate efforts to raise their children in as “gender-neutral” a way as possible and encourage their daughters to strive for success to the same degree as their sons. Explicit bias against women remains easier to recognize and combat than implicit or unconscious bias, to which we are all subject.

We have only recently begun to acknowledge and attempt to dispel implicit bias and much work remains to be done if we are to reach a level playing field that is gender neutral. The book, “Why So Slow?” by Virginia Valian (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1998) offered valuable insights that helped me understand why we behave as we do and how our departments and institutions might become more equitable to all. Women tend to underrate their abilities and attribute their success to luck rather than superior performance, to believe that they are less qualified for higher pay or promotion than men are, and to be less assertive than men in negotiations. It will require conscious vigilance and effort by both sexes as well as by institutions themselves to educate all about the criteria necessary for advancement. Institutions need to develop training for all in recognizing and eliminating implicit bias, and in implementing clear and explicit criteria for compensation and promotion, making sure that all faculty are educated to understand what those criteria are.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

For most of my professional life I have avoided writing about gender inequity in the field of surgery – not because I believe it does not exist, but because the reasons it does exist are manifold and complicated.

To be sure, implicit and explicit bias remain important reasons why only a minority of female medical students still choose surgery as a career in 2018, why female surgeons still earn only 82% of the salary of their male counterparts, and why women occupy only 12% of the chairs in academic surgical departments in the United States. It has long been tempting to lay the blame for those inequities on a stereotypical macho surgical culture that prevailed as the 20th century came to a close. But the factors that perpetuate male/female imbalance in our profession are complicated and run deep in the psyches of both men and women. We are all products of our generations, our culture, upbringing, and environment – men as well as women. Correcting the imbalance requires much more than simply passing laws that require equitable pay or treatment.

I realized how deeply ingrained biases are in all of us while still in my surgical residency in the 1970s. On a rare occasion when neither my husband (also a surgical resident) nor I was on call, we had a dinner party with friends at our house. The telephone rang (no iPhones, just a land line), and I ran to answer our only telephone in another room. It was the hospital operator, who asked, “Is Dr. Deveney there?” Without thinking, I answered, “Just a moment, I’ll get him!” I had taken only three steps away from the phone when it occurred to me what I had just said. I turned back, picked up the phone, and asked, “Which Dr. Deveney were you looking for?”

If even I had been conditioned to think automatically of “doctor” being a man after all of my effort to earn a place in the ranks, was there any hope that equality could be achieved? When I finished my residency and was offered a surgery position at our VA, I asked no questions about salary or other particulars; I was simply grateful that I had been given a job.

That was 1978 – a different time, a different generation. Since then, women have made dramatic progress toward equity in our profession, as in many others. The support, mentoring, and consciousness-raising efforts of the Association of Women Surgeons (AWS) are responsible for much of this progress. The American College of Surgeons was very supportive of the AWS early on and continues to encourage female medical students to choose surgery as a career and to help the advancement of women into leadership roles in surgery. Many surgical residency programs have 50% women in their ranks; half of our residents in Oregon have been women for over a decade. Our program director is a woman, as are 28% of the faculty; not 50%, but definitely progress, since I was the lone woman on the faculty when I arrived in 1987.

Although women occupy only 12% of the surgical chairs in U.S. surgical departments, this number has soared in the past 2 years from 7 in 2016 to 21 this year after languishing in the low single digits since 1987, when the late Olga Jonasson, MD, FACS, became the first female chair at Ohio State University. And yet, women have not reached full equality with men across the United States in surgical training, leadership, or pay. Why not?

Multiple factors have played roles in impeding the progress of women in achieving equality in surgery. Traditional cultural expectations of male and female roles in society affect both genders as they grow up, even when their parents make deliberate efforts to raise their children in as “gender-neutral” a way as possible and encourage their daughters to strive for success to the same degree as their sons. Explicit bias against women remains easier to recognize and combat than implicit or unconscious bias, to which we are all subject.

We have only recently begun to acknowledge and attempt to dispel implicit bias and much work remains to be done if we are to reach a level playing field that is gender neutral. The book, “Why So Slow?” by Virginia Valian (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1998) offered valuable insights that helped me understand why we behave as we do and how our departments and institutions might become more equitable to all. Women tend to underrate their abilities and attribute their success to luck rather than superior performance, to believe that they are less qualified for higher pay or promotion than men are, and to be less assertive than men in negotiations. It will require conscious vigilance and effort by both sexes as well as by institutions themselves to educate all about the criteria necessary for advancement. Institutions need to develop training for all in recognizing and eliminating implicit bias, and in implementing clear and explicit criteria for compensation and promotion, making sure that all faculty are educated to understand what those criteria are.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

For most of my professional life I have avoided writing about gender inequity in the field of surgery – not because I believe it does not exist, but because the reasons it does exist are manifold and complicated.

To be sure, implicit and explicit bias remain important reasons why only a minority of female medical students still choose surgery as a career in 2018, why female surgeons still earn only 82% of the salary of their male counterparts, and why women occupy only 12% of the chairs in academic surgical departments in the United States. It has long been tempting to lay the blame for those inequities on a stereotypical macho surgical culture that prevailed as the 20th century came to a close. But the factors that perpetuate male/female imbalance in our profession are complicated and run deep in the psyches of both men and women. We are all products of our generations, our culture, upbringing, and environment – men as well as women. Correcting the imbalance requires much more than simply passing laws that require equitable pay or treatment.

I realized how deeply ingrained biases are in all of us while still in my surgical residency in the 1970s. On a rare occasion when neither my husband (also a surgical resident) nor I was on call, we had a dinner party with friends at our house. The telephone rang (no iPhones, just a land line), and I ran to answer our only telephone in another room. It was the hospital operator, who asked, “Is Dr. Deveney there?” Without thinking, I answered, “Just a moment, I’ll get him!” I had taken only three steps away from the phone when it occurred to me what I had just said. I turned back, picked up the phone, and asked, “Which Dr. Deveney were you looking for?”

If even I had been conditioned to think automatically of “doctor” being a man after all of my effort to earn a place in the ranks, was there any hope that equality could be achieved? When I finished my residency and was offered a surgery position at our VA, I asked no questions about salary or other particulars; I was simply grateful that I had been given a job.

That was 1978 – a different time, a different generation. Since then, women have made dramatic progress toward equity in our profession, as in many others. The support, mentoring, and consciousness-raising efforts of the Association of Women Surgeons (AWS) are responsible for much of this progress. The American College of Surgeons was very supportive of the AWS early on and continues to encourage female medical students to choose surgery as a career and to help the advancement of women into leadership roles in surgery. Many surgical residency programs have 50% women in their ranks; half of our residents in Oregon have been women for over a decade. Our program director is a woman, as are 28% of the faculty; not 50%, but definitely progress, since I was the lone woman on the faculty when I arrived in 1987.

Although women occupy only 12% of the surgical chairs in U.S. surgical departments, this number has soared in the past 2 years from 7 in 2016 to 21 this year after languishing in the low single digits since 1987, when the late Olga Jonasson, MD, FACS, became the first female chair at Ohio State University. And yet, women have not reached full equality with men across the United States in surgical training, leadership, or pay. Why not?

Multiple factors have played roles in impeding the progress of women in achieving equality in surgery. Traditional cultural expectations of male and female roles in society affect both genders as they grow up, even when their parents make deliberate efforts to raise their children in as “gender-neutral” a way as possible and encourage their daughters to strive for success to the same degree as their sons. Explicit bias against women remains easier to recognize and combat than implicit or unconscious bias, to which we are all subject.

We have only recently begun to acknowledge and attempt to dispel implicit bias and much work remains to be done if we are to reach a level playing field that is gender neutral. The book, “Why So Slow?” by Virginia Valian (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1998) offered valuable insights that helped me understand why we behave as we do and how our departments and institutions might become more equitable to all. Women tend to underrate their abilities and attribute their success to luck rather than superior performance, to believe that they are less qualified for higher pay or promotion than men are, and to be less assertive than men in negotiations. It will require conscious vigilance and effort by both sexes as well as by institutions themselves to educate all about the criteria necessary for advancement. Institutions need to develop training for all in recognizing and eliminating implicit bias, and in implementing clear and explicit criteria for compensation and promotion, making sure that all faculty are educated to understand what those criteria are.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

The algorithm less traveled

To this day I remain impressed by the algorithmic nature of trauma management. A routine that to the internist could appear mindless and slavish was to the trauma physician a protocol designed to take no chances on missing a life-threatening complication in the heat of the moment. The trauma physician cannot afford to wait for a cognitively derived epiphany in a clinical setting that often rapidly unfolds as a series of “never-miss” scenarios. The appropriate algorithm, rigorously followed, offers the best chance of avoiding a catastrophe of omission. This was long before Atul Gawande published his Checklist Manifesto.