User login

Delivering bad news in obstetric practice

Obstetrics is a field filled with joyful experiences highlighted by pregnancy, childbirth, and the growth of healthy families. The field is also filled with many experiences that are sorrowful, including failure to conceive after infertility treatment, miscarriage, ultrasound-detected fetal anomalies, fetuses with genetic problems, fetal and neonatal demise, extremely premature birth, and birth injury. For decades oncologists have evolved their approach to discussing bad news with cancer patients. In the distant past, oncologists often kept a cancer diagnosis from the patient, preferring to spare them the stress of the news. In the modern era of transparency, however, oncologists now uniformly strive to keep patients informed of their situation and have adopted structured approaches to delivering bad news. An adverse pregnancy outcome such as a miscarriage or fetal loss may trigger emotional responses as intense as those experienced by a person hearing about a cancer diagnosis. Women who have recently experienced a miscarriage report emotional responses ranging from “a little disappointed” to “in shock” and “for it to be taken away was crushing.”1 As obstetricians, we can advance our practice by adopting a structured approach to delivering bad news, building on the lessons from cancer medicine. Improving the quality of our communication about adverse pregnancy events will reduce emotional distress and enable patients and families to more effectively cope with challenging situations.

Communicating bad news: The facts, the emotional response, and the impact on identity

Clinicians need to be cognizant that a conversation about bad news is 3 interwoven conversations that involve facts, emotional responses, and an altered self-identity. In addition to communicating the facts of the event in clear language, clinicians need to simultaneously monitor and manage the emotional responses to the adverse event and the impact on the participants’ sense of self.2 Clinicians are steeped in scientific tradition and method, and as experts we are naturally drawn to a discussion of the facts.

However, a discussion about bad news is highly likely to trigger an emotional response in the patient and the clinician. For example, when a clinician tells the patient about delivery events that resulted in an unexpected newborn injury, the patient may become angry and the clinician may be fearful, anxious, and defensive. Managing the emotions of all participants in the conversation is important for an optimal outcome.

An adverse event also may cause those involved to think about their self-identity. A key feature of bad news is that it alters patients’ expectations about their future, juxtaposing the reality of their outcome with the preferable outcome that may have been. Following a stillbirth during her first pregnancy the patient may be wondering, “Will I ever be a mother?”, “Did I cause the loss?”, and “Does all life end in death?” A traumatic event also may impact the self-identity of the clinician. Following a delivery where the newborn was injured, the clinician may be wondering, “Am I a good or bad clinician?”, “Did I do something wrong?”, “Is it time for me to retire from obstetrical practice?”

Following an adverse pregnancy outcome some patients are consumed with intense grief. This may require the patient and her family to move through a series of emotions (similar to those who receive a new diagnosis of cancer), including denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Responses to grief

Kubler-Ross identified these 5 psychological coping mechanisms that are often used by people experiencing grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.3 The goal of the clinician is to help grieving patients move through these stages in an appropriate fashion and not get stuck in the stages of denial, anger, and/or depression. Following a difficult pregnancy some patients and their family members become stuck in a state dominated by anger, rage, and resentment. This is fertile ground for the growth of a professional liability case. Denial and anger are adaptive short-term defenses to protecting self-identity. In time, most people engage in more constructive responses, accept the adverse event, and plan for the future. Kubler-Ross observed that hope helps people survive through a time of great suffering and is present throughout the response to grief. Clinicians can play an important role in ensuring that a flame of hope is kept burning throughout the process of responding to and grieving bad outcomes.

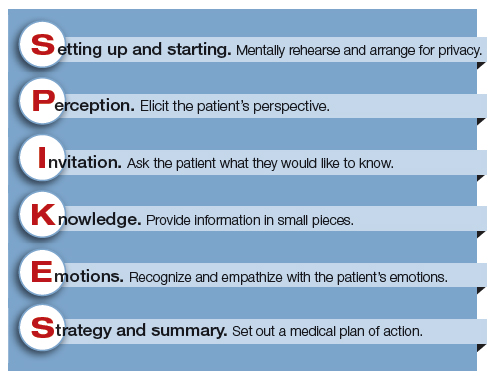

A structured approach to delivering bad news: SPIKES

Dr. Robert Buckman, an oncologist, has proposed using a structured approach, SPIKES, to guide conversations focused on delivering bad news.4–6 SPIKES is focused on trying to deeply understand the patient’s level of knowledge, emotions, and perspective before providing medical information and support. SPIKES consists of 6 key steps.

1. Setting up and starting. Mentally rehearse and arrange for privacy. Make sure the patient’s support people are present. Sit down, use open body language, eye contact, and/or touch to make a connection with the patient. Create room for a dialogue by using open-ended questions, silent pauses, listening first, and encouraging the patient to provide their perspective.

2. Perception. Elicit the patient’s perspective. Assess what the patient believes and feels. Assess vocabulary and comprehension.

3. Invitation. Ask the patient what they would like to know. Obtain permission to share knowledge.

4. Knowledge. Provide information in small pieces, always checking back on the patient’s understanding. Use plain language that aligns with the patient’s vocabulary and understanding.

5. Emotions. Explore, explicitly recognize, and empathize with the patient’s emotions.

6. Strategy and summary. Set out a medical plan of action. Express a commitment to be available for the patient as she embarks on the care plan. Arrange for a follow-up conversation.

Some studies have indicated that having a protocol such as SPIKES for delivering bad news helps clinicians to navigate this challenging process, which in turn improves patient satisfaction with disclosure.7 Simulation training focused on communicating bad news could be better utilized to help clinicians practice this skill, similar to the simulation exercises used to practice common clinical problems like hemorrhage and shoulder dystocia.8,9

Physician responses to bad outcomes

Over a career in clinical practice, physicians experience many bad outcomes that expose them to the contagion of sadness and grief. Despite this vicarious trauma, they must always present a professional persona, placing the patient’s needs above their own pain. Due to these experiences, clinicians may become isolated, depressed, and burned out. Drs. Michael and Enid Balint recognized the adverse effect of a lifetime of exposure to suffering and pain. They proposed that physicians could mitigate the trauma of these experiences by participating in small group meetings with a trained leader to discuss their most difficult clinical experiences in a confidential and supportive environment.10,11 By sharing clinical experiences, feelings, and stories with trusted colleagues, physicians can channel painful experiences into a greater understanding of the empathy and compassion needed to care for themselves, their colleagues, and patients. Clinical practice is invariably punctuated by occasional adverse outcomes necessitating that we effectively manage the process of delivering bad news, simultaneously caring for ourselves and our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Flink-Bochacki R, Hamm ME, Borrero S, Chen BA, Achilles SL, Chang JC. Family planning and counseling desires of women who have experienced miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):625-631.

- Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations. How to discuss what matters most. Penguin Books: New York, NY; 1999:9-10.

- Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. MacMillan: New York, NY; 1969.

- Buckman R. How to break bad news. A guide for health care professionals. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 1992.

- Buckman R. Practical plans for difficult conversations in medicine. Strategies that work in breaking bad news. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 2010.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312-319.

- Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, Stern D. Teaching students to break bad news. Am J Surg. 2001;182(1):20-23.

- Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: a review of strategies. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):107-117.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Pitman: London, England; 1957.

- Salinksky J. Balint groups and the Balint method. The Balint Society website. https://balint.co.uk/about/the-balint-method/. Accessed May 17, 2018.

Obstetrics is a field filled with joyful experiences highlighted by pregnancy, childbirth, and the growth of healthy families. The field is also filled with many experiences that are sorrowful, including failure to conceive after infertility treatment, miscarriage, ultrasound-detected fetal anomalies, fetuses with genetic problems, fetal and neonatal demise, extremely premature birth, and birth injury. For decades oncologists have evolved their approach to discussing bad news with cancer patients. In the distant past, oncologists often kept a cancer diagnosis from the patient, preferring to spare them the stress of the news. In the modern era of transparency, however, oncologists now uniformly strive to keep patients informed of their situation and have adopted structured approaches to delivering bad news. An adverse pregnancy outcome such as a miscarriage or fetal loss may trigger emotional responses as intense as those experienced by a person hearing about a cancer diagnosis. Women who have recently experienced a miscarriage report emotional responses ranging from “a little disappointed” to “in shock” and “for it to be taken away was crushing.”1 As obstetricians, we can advance our practice by adopting a structured approach to delivering bad news, building on the lessons from cancer medicine. Improving the quality of our communication about adverse pregnancy events will reduce emotional distress and enable patients and families to more effectively cope with challenging situations.

Communicating bad news: The facts, the emotional response, and the impact on identity

Clinicians need to be cognizant that a conversation about bad news is 3 interwoven conversations that involve facts, emotional responses, and an altered self-identity. In addition to communicating the facts of the event in clear language, clinicians need to simultaneously monitor and manage the emotional responses to the adverse event and the impact on the participants’ sense of self.2 Clinicians are steeped in scientific tradition and method, and as experts we are naturally drawn to a discussion of the facts.

However, a discussion about bad news is highly likely to trigger an emotional response in the patient and the clinician. For example, when a clinician tells the patient about delivery events that resulted in an unexpected newborn injury, the patient may become angry and the clinician may be fearful, anxious, and defensive. Managing the emotions of all participants in the conversation is important for an optimal outcome.

An adverse event also may cause those involved to think about their self-identity. A key feature of bad news is that it alters patients’ expectations about their future, juxtaposing the reality of their outcome with the preferable outcome that may have been. Following a stillbirth during her first pregnancy the patient may be wondering, “Will I ever be a mother?”, “Did I cause the loss?”, and “Does all life end in death?” A traumatic event also may impact the self-identity of the clinician. Following a delivery where the newborn was injured, the clinician may be wondering, “Am I a good or bad clinician?”, “Did I do something wrong?”, “Is it time for me to retire from obstetrical practice?”

Following an adverse pregnancy outcome some patients are consumed with intense grief. This may require the patient and her family to move through a series of emotions (similar to those who receive a new diagnosis of cancer), including denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Responses to grief

Kubler-Ross identified these 5 psychological coping mechanisms that are often used by people experiencing grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.3 The goal of the clinician is to help grieving patients move through these stages in an appropriate fashion and not get stuck in the stages of denial, anger, and/or depression. Following a difficult pregnancy some patients and their family members become stuck in a state dominated by anger, rage, and resentment. This is fertile ground for the growth of a professional liability case. Denial and anger are adaptive short-term defenses to protecting self-identity. In time, most people engage in more constructive responses, accept the adverse event, and plan for the future. Kubler-Ross observed that hope helps people survive through a time of great suffering and is present throughout the response to grief. Clinicians can play an important role in ensuring that a flame of hope is kept burning throughout the process of responding to and grieving bad outcomes.

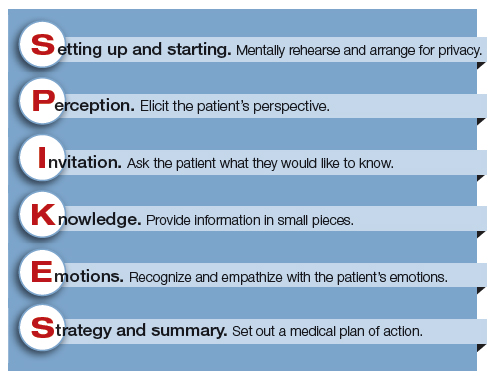

A structured approach to delivering bad news: SPIKES

Dr. Robert Buckman, an oncologist, has proposed using a structured approach, SPIKES, to guide conversations focused on delivering bad news.4–6 SPIKES is focused on trying to deeply understand the patient’s level of knowledge, emotions, and perspective before providing medical information and support. SPIKES consists of 6 key steps.

1. Setting up and starting. Mentally rehearse and arrange for privacy. Make sure the patient’s support people are present. Sit down, use open body language, eye contact, and/or touch to make a connection with the patient. Create room for a dialogue by using open-ended questions, silent pauses, listening first, and encouraging the patient to provide their perspective.

2. Perception. Elicit the patient’s perspective. Assess what the patient believes and feels. Assess vocabulary and comprehension.

3. Invitation. Ask the patient what they would like to know. Obtain permission to share knowledge.

4. Knowledge. Provide information in small pieces, always checking back on the patient’s understanding. Use plain language that aligns with the patient’s vocabulary and understanding.

5. Emotions. Explore, explicitly recognize, and empathize with the patient’s emotions.

6. Strategy and summary. Set out a medical plan of action. Express a commitment to be available for the patient as she embarks on the care plan. Arrange for a follow-up conversation.

Some studies have indicated that having a protocol such as SPIKES for delivering bad news helps clinicians to navigate this challenging process, which in turn improves patient satisfaction with disclosure.7 Simulation training focused on communicating bad news could be better utilized to help clinicians practice this skill, similar to the simulation exercises used to practice common clinical problems like hemorrhage and shoulder dystocia.8,9

Physician responses to bad outcomes

Over a career in clinical practice, physicians experience many bad outcomes that expose them to the contagion of sadness and grief. Despite this vicarious trauma, they must always present a professional persona, placing the patient’s needs above their own pain. Due to these experiences, clinicians may become isolated, depressed, and burned out. Drs. Michael and Enid Balint recognized the adverse effect of a lifetime of exposure to suffering and pain. They proposed that physicians could mitigate the trauma of these experiences by participating in small group meetings with a trained leader to discuss their most difficult clinical experiences in a confidential and supportive environment.10,11 By sharing clinical experiences, feelings, and stories with trusted colleagues, physicians can channel painful experiences into a greater understanding of the empathy and compassion needed to care for themselves, their colleagues, and patients. Clinical practice is invariably punctuated by occasional adverse outcomes necessitating that we effectively manage the process of delivering bad news, simultaneously caring for ourselves and our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Obstetrics is a field filled with joyful experiences highlighted by pregnancy, childbirth, and the growth of healthy families. The field is also filled with many experiences that are sorrowful, including failure to conceive after infertility treatment, miscarriage, ultrasound-detected fetal anomalies, fetuses with genetic problems, fetal and neonatal demise, extremely premature birth, and birth injury. For decades oncologists have evolved their approach to discussing bad news with cancer patients. In the distant past, oncologists often kept a cancer diagnosis from the patient, preferring to spare them the stress of the news. In the modern era of transparency, however, oncologists now uniformly strive to keep patients informed of their situation and have adopted structured approaches to delivering bad news. An adverse pregnancy outcome such as a miscarriage or fetal loss may trigger emotional responses as intense as those experienced by a person hearing about a cancer diagnosis. Women who have recently experienced a miscarriage report emotional responses ranging from “a little disappointed” to “in shock” and “for it to be taken away was crushing.”1 As obstetricians, we can advance our practice by adopting a structured approach to delivering bad news, building on the lessons from cancer medicine. Improving the quality of our communication about adverse pregnancy events will reduce emotional distress and enable patients and families to more effectively cope with challenging situations.

Communicating bad news: The facts, the emotional response, and the impact on identity

Clinicians need to be cognizant that a conversation about bad news is 3 interwoven conversations that involve facts, emotional responses, and an altered self-identity. In addition to communicating the facts of the event in clear language, clinicians need to simultaneously monitor and manage the emotional responses to the adverse event and the impact on the participants’ sense of self.2 Clinicians are steeped in scientific tradition and method, and as experts we are naturally drawn to a discussion of the facts.

However, a discussion about bad news is highly likely to trigger an emotional response in the patient and the clinician. For example, when a clinician tells the patient about delivery events that resulted in an unexpected newborn injury, the patient may become angry and the clinician may be fearful, anxious, and defensive. Managing the emotions of all participants in the conversation is important for an optimal outcome.

An adverse event also may cause those involved to think about their self-identity. A key feature of bad news is that it alters patients’ expectations about their future, juxtaposing the reality of their outcome with the preferable outcome that may have been. Following a stillbirth during her first pregnancy the patient may be wondering, “Will I ever be a mother?”, “Did I cause the loss?”, and “Does all life end in death?” A traumatic event also may impact the self-identity of the clinician. Following a delivery where the newborn was injured, the clinician may be wondering, “Am I a good or bad clinician?”, “Did I do something wrong?”, “Is it time for me to retire from obstetrical practice?”

Following an adverse pregnancy outcome some patients are consumed with intense grief. This may require the patient and her family to move through a series of emotions (similar to those who receive a new diagnosis of cancer), including denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Responses to grief

Kubler-Ross identified these 5 psychological coping mechanisms that are often used by people experiencing grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.3 The goal of the clinician is to help grieving patients move through these stages in an appropriate fashion and not get stuck in the stages of denial, anger, and/or depression. Following a difficult pregnancy some patients and their family members become stuck in a state dominated by anger, rage, and resentment. This is fertile ground for the growth of a professional liability case. Denial and anger are adaptive short-term defenses to protecting self-identity. In time, most people engage in more constructive responses, accept the adverse event, and plan for the future. Kubler-Ross observed that hope helps people survive through a time of great suffering and is present throughout the response to grief. Clinicians can play an important role in ensuring that a flame of hope is kept burning throughout the process of responding to and grieving bad outcomes.

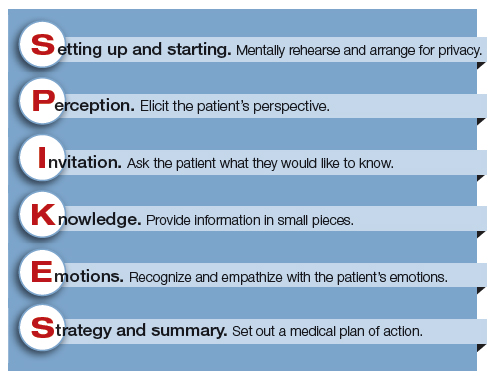

A structured approach to delivering bad news: SPIKES

Dr. Robert Buckman, an oncologist, has proposed using a structured approach, SPIKES, to guide conversations focused on delivering bad news.4–6 SPIKES is focused on trying to deeply understand the patient’s level of knowledge, emotions, and perspective before providing medical information and support. SPIKES consists of 6 key steps.

1. Setting up and starting. Mentally rehearse and arrange for privacy. Make sure the patient’s support people are present. Sit down, use open body language, eye contact, and/or touch to make a connection with the patient. Create room for a dialogue by using open-ended questions, silent pauses, listening first, and encouraging the patient to provide their perspective.

2. Perception. Elicit the patient’s perspective. Assess what the patient believes and feels. Assess vocabulary and comprehension.

3. Invitation. Ask the patient what they would like to know. Obtain permission to share knowledge.

4. Knowledge. Provide information in small pieces, always checking back on the patient’s understanding. Use plain language that aligns with the patient’s vocabulary and understanding.

5. Emotions. Explore, explicitly recognize, and empathize with the patient’s emotions.

6. Strategy and summary. Set out a medical plan of action. Express a commitment to be available for the patient as she embarks on the care plan. Arrange for a follow-up conversation.

Some studies have indicated that having a protocol such as SPIKES for delivering bad news helps clinicians to navigate this challenging process, which in turn improves patient satisfaction with disclosure.7 Simulation training focused on communicating bad news could be better utilized to help clinicians practice this skill, similar to the simulation exercises used to practice common clinical problems like hemorrhage and shoulder dystocia.8,9

Physician responses to bad outcomes

Over a career in clinical practice, physicians experience many bad outcomes that expose them to the contagion of sadness and grief. Despite this vicarious trauma, they must always present a professional persona, placing the patient’s needs above their own pain. Due to these experiences, clinicians may become isolated, depressed, and burned out. Drs. Michael and Enid Balint recognized the adverse effect of a lifetime of exposure to suffering and pain. They proposed that physicians could mitigate the trauma of these experiences by participating in small group meetings with a trained leader to discuss their most difficult clinical experiences in a confidential and supportive environment.10,11 By sharing clinical experiences, feelings, and stories with trusted colleagues, physicians can channel painful experiences into a greater understanding of the empathy and compassion needed to care for themselves, their colleagues, and patients. Clinical practice is invariably punctuated by occasional adverse outcomes necessitating that we effectively manage the process of delivering bad news, simultaneously caring for ourselves and our patients.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Flink-Bochacki R, Hamm ME, Borrero S, Chen BA, Achilles SL, Chang JC. Family planning and counseling desires of women who have experienced miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):625-631.

- Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations. How to discuss what matters most. Penguin Books: New York, NY; 1999:9-10.

- Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. MacMillan: New York, NY; 1969.

- Buckman R. How to break bad news. A guide for health care professionals. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 1992.

- Buckman R. Practical plans for difficult conversations in medicine. Strategies that work in breaking bad news. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 2010.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312-319.

- Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, Stern D. Teaching students to break bad news. Am J Surg. 2001;182(1):20-23.

- Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: a review of strategies. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):107-117.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Pitman: London, England; 1957.

- Salinksky J. Balint groups and the Balint method. The Balint Society website. https://balint.co.uk/about/the-balint-method/. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- Flink-Bochacki R, Hamm ME, Borrero S, Chen BA, Achilles SL, Chang JC. Family planning and counseling desires of women who have experienced miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):625-631.

- Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations. How to discuss what matters most. Penguin Books: New York, NY; 1999:9-10.

- Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. MacMillan: New York, NY; 1969.

- Buckman R. How to break bad news. A guide for health care professionals. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 1992.

- Buckman R. Practical plans for difficult conversations in medicine. Strategies that work in breaking bad news. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD; 2010.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004;363(9405):312-319.

- Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, Stern D. Teaching students to break bad news. Am J Surg. 2001;182(1):20-23.

- Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: a review of strategies. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):107-117.

- Balint M. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Pitman: London, England; 1957.

- Salinksky J. Balint groups and the Balint method. The Balint Society website. https://balint.co.uk/about/the-balint-method/. Accessed May 17, 2018.