User login

The daunting challenge of schizophrenia: Hundreds of biotypes and dozens of theories

Islands of knowledge in an ocean of ignorance. That summarizes the advances in unraveling the enigma of schizophrenia, arguably the most complex psychiatric brain disorder. The more breakthroughs are made, the more questions emerge.

Progress is definitely being made and the published literature, replete with new findings, is growing logarithmically. Particularly exciting are the recent advances in the etiology of schizophrenia, both genetic and environmental. Collaboration among geneticists around the world has enabled genome-wide association studies on almost 50,000 DNA samples and has revealed 3 genetic pathways to disrupted brain development, which lead to schizophrenia in early adulthood. Those genetic pathways include:

1. Susceptibility genes—more than 340 of them—are found significantly more often in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population. These risk genes are scattered across all 23 pairs of chromosomes. They influence neurotransmitter functions, neuroplasticity, and immune regulation. The huge task that lies ahead is identifying what each of the risk genes disrupts in brain structure and/or function.

2. Copy number variants (CNVs), such as deletions (1 allele instead of the normal 2) or duplications (3 alleles), are much more frequent in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population. That means too little or too much protein is made, which can disrupt the 4 stages of brain development (proliferation, migration, differentiation, and elimination).

3. de novo nonsense mutations, leading to complete absence of protein coding by the affected genes, with adverse ripple effects on brain development.

Approximately 10,000 genes (close to 50% of all 22,000 coding genes in the human genome) are involved in constructing the human brain. The latest estimate is that 79% of the hundreds of biotypes of schizophrenia are genetic in etiology.

In addition, multiple environmental factors can disrupt brain development and lead to schizophrenia. These include older paternal age (>45 years) at the time of conception, pregnancy complications (infections, gestational diabetes, vitamin D deficiency, hypoxia during delivery), childhood maltreatment (sexual or physical abuse or neglect) in the first 5 to 6 years of life, as well as migration and urbanicity (being born and raised in a large metropolitan area).

The bottom line: Schizophrenia is not only very complex, but also an extremely heterogeneous brain syndrome, both biologically and clinically. Psychiatric practitioners are fully cognizant of the extensive clinical variability in patients with schizophrenia, including the presence, absence, or severity of various signs and symptoms, such as insight, delusions, hallucinations, conceptual disorganization, bizarre behaviors, emotional withdrawal, agitation, depression, suicidality, anxiety, substance use, somatic concerns, hostility, idiosyncratic mannerisms, blunted affect, apathy, avolition, self-neglect, poor attention, memory impairment, and problems with decision-making, planning ahead, or organizing one’s life.

In addition, heterogeneity is encountered in such variables as age of onset, minor physical anomalies, soft neurologic signs, naturally occurring movement disorders, premorbid functioning, family history, general medical comorbidities, psychiatry comorbidities, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, neurophysiological deviations (pre-pulse inhibition, p50, p300, N100, mismatch negativity, smooth pursuit eye movements), pituitary volume, rapidity and extent of response to antipsychotics, type and frequency of adverse effects, and functional disability or restoration of vocational functioning.

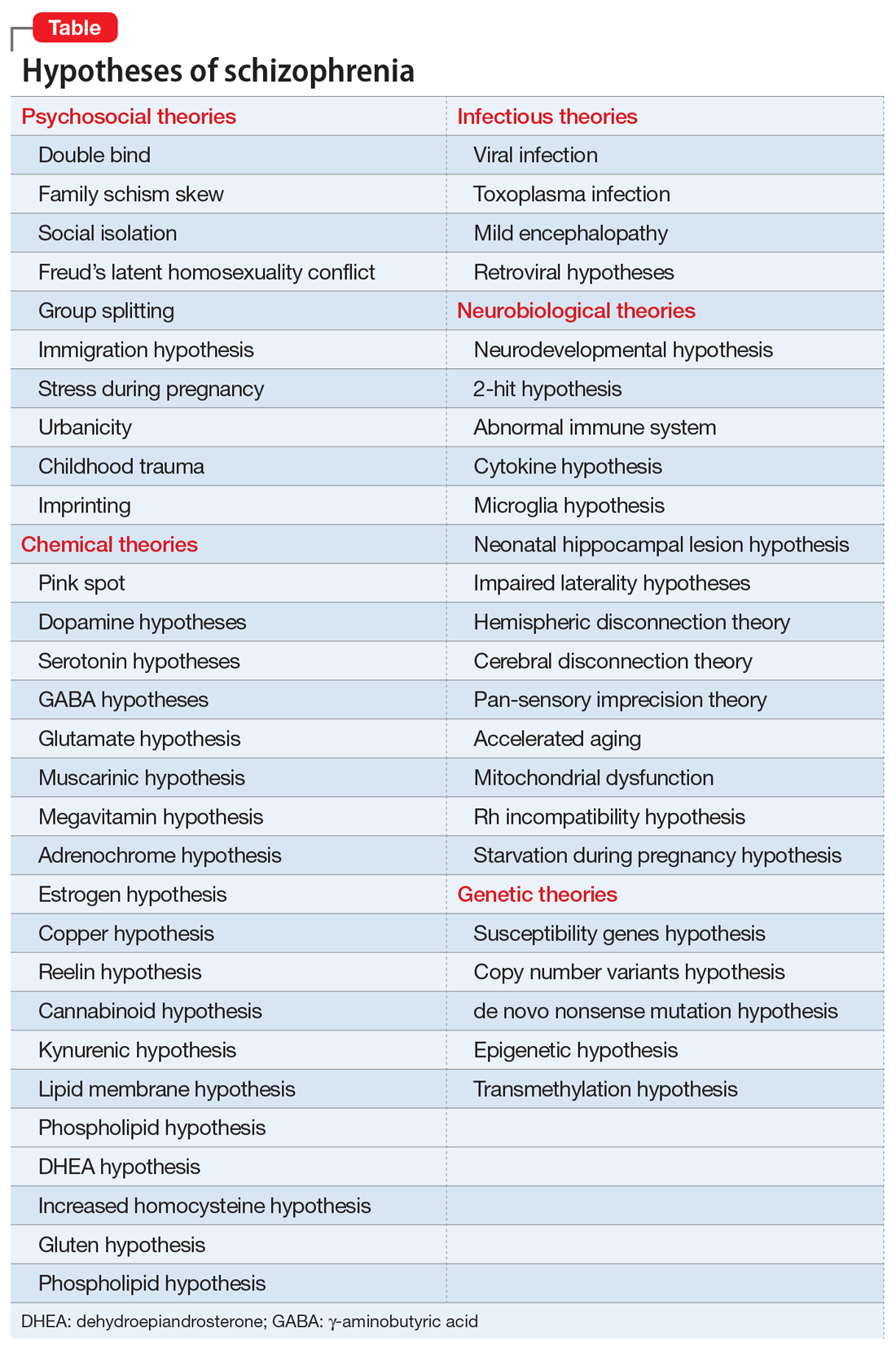

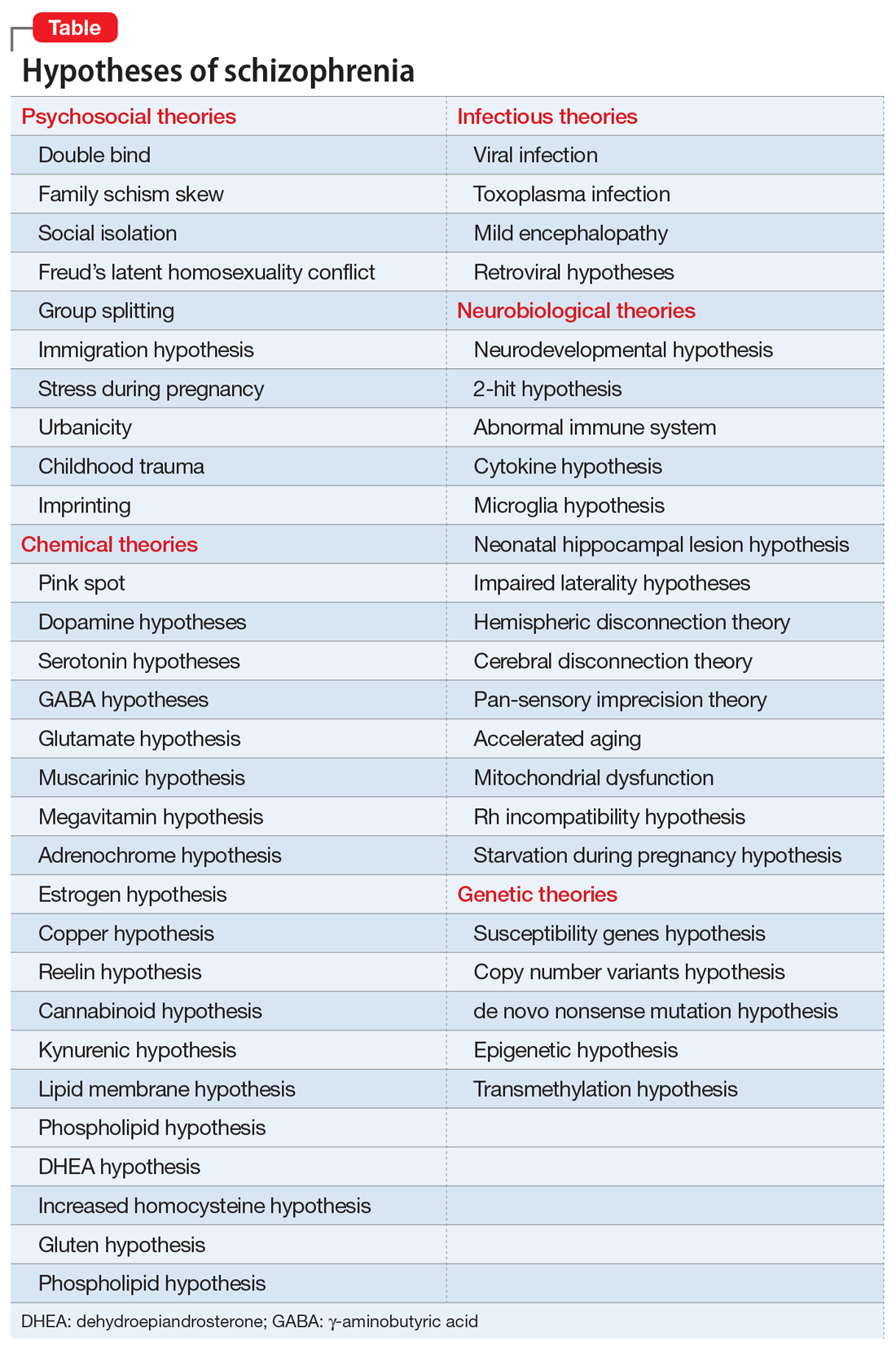

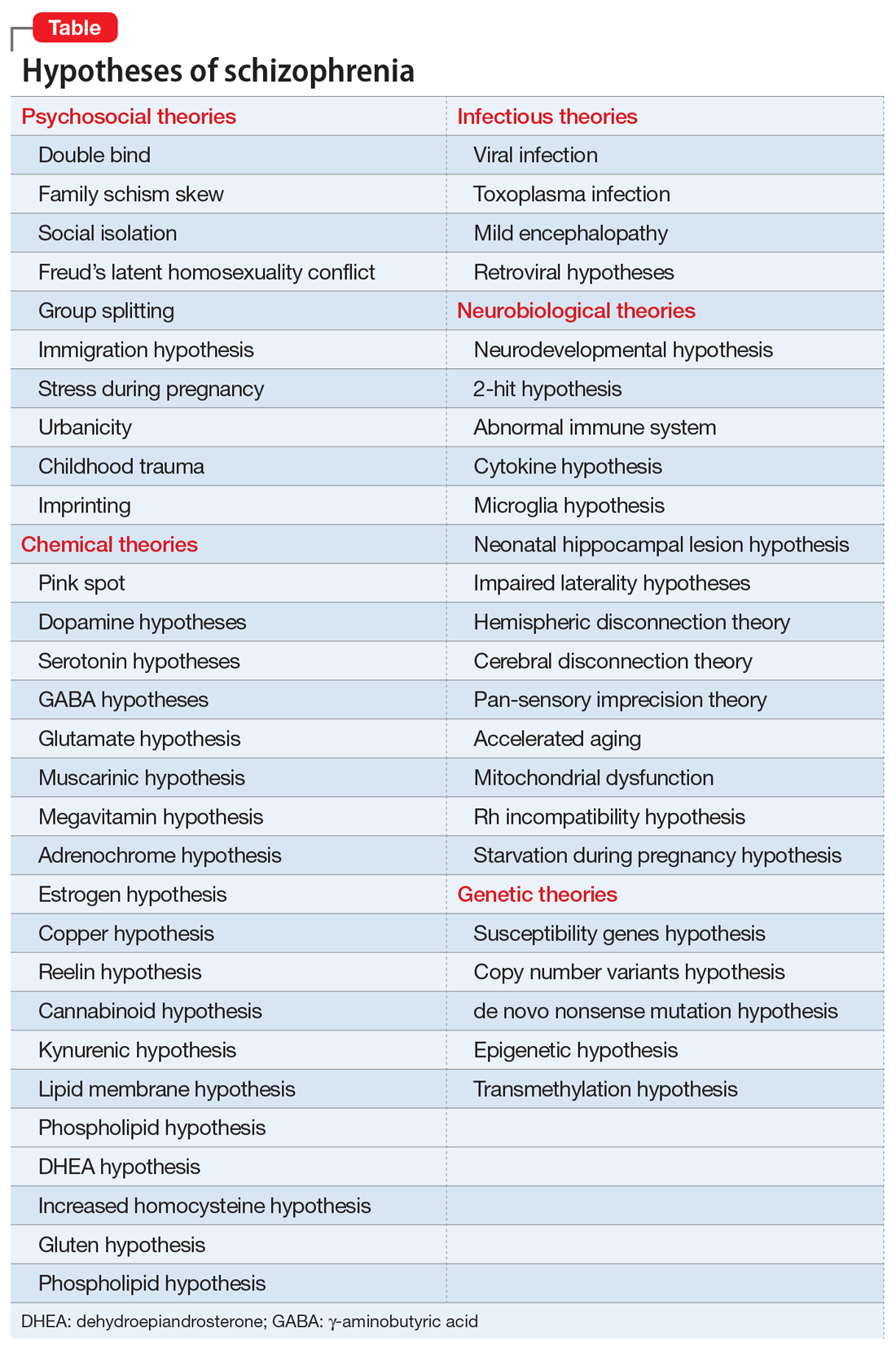

No wonder, then, given the daunting biologic and clinical heterogeneity of this complex brain syndrome, that myriad hypotheses have been proposed over the past century. The Table lists approximately 50 hypotheses, some discredited but others plausible and still viable. The most absurd hypotheses are the double bind theory of schizophrenia in the 1950s by Gregory Bateson et al, or the latent homosexuality theory of Freud. Some hypotheses may be related to a specific biotype within the schizophrenia syndrome (such as the megavitamin theory) that do not apply to other biotypes. Some of the hypotheses seem to be the product of the rich imagination of an enthusiastic researcher based on limited data.

Another consequence of the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia is the large number of “lab tests” that have been reported over the past few decades.1 Those hundreds of biomarkers probably mirror the biologies of the numerous disease subtypes within the schizophrenia syndrome. Some are blood tests, others neurophysiological or neuroimaging, others molecular or genetic, along with many postmortem tissue markers. Obviously, none of these “lab tests” can be used clinically because there would be an unacceptably large number of false positives and false negatives when applied to a heterogeneous sample of patients with schizophrenia.

Heterogeneity also represents a formidable challenge for researchers. Replication of a research finding by investigators across the world can be quite challenging because of the variable composition of biotypes in different countries. This heterogeneity also complicates FDA clinical trials by pharmaceutical companies seeking approval for a new drug to treat schizophrenia. The FDA requires use of DSM diagnostic criteria, which would include patients with similar clinical symptoms, but who can vary widely at the biological level. This results in failed clinical trials where only 20% or 30% of patients with schizophrenia show significant improvement compared with placebo. Given the advances in schizophrenia, a better strategy is to recruit participants who share a specific biomarker to assemble a biologically more homogeneous sample of schizophrenia. If the clinical trial is successful, the same biomarker can then be used by practitioners to predict response to the new drug. That would fulfill the aspirations of applying precision medicine in psychiatric practice.

The famous Eugen Bleuler (whose sister suffered from schizophrenia) was prescient when a century ago he published his classic book titled Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias.2 His astute clinical observations led him to recognize the heterogeneity of the syndrome whose name he coined (schizophrenia, or disconnected thoughts). His conceptualization of schizophrenia as a spectrum of disorders of variable outcomes contrasted with that of Emil Kraepelin’s model,3 which regarded dementia praecox as a single, homogeneous, deteriorating disease. But neither Bleuler nor Kraepelin, both of whom relied on clinical observations without any biologic studies, could even imagine the spectacular complexity of the neurobiology of the schizophrenia syndrome and how difficult it is to identify its many biotypes. The monumental advances in neuroscience and neurogenetics, with their sophisticated methodologies, will eventually decipher the mysteries of this neuropsychiatric syndrome, which generates so many aberrations in thought, affect, mood, cognition, and behavior, often leading to severe functional disability among young adults, and untold anguish for their families.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: Few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

2. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

3. Hippius H, Muller N. The work of Emil Kraepelin and his research group in Munich. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(Suppl 2):3-11.

Islands of knowledge in an ocean of ignorance. That summarizes the advances in unraveling the enigma of schizophrenia, arguably the most complex psychiatric brain disorder. The more breakthroughs are made, the more questions emerge.

Progress is definitely being made and the published literature, replete with new findings, is growing logarithmically. Particularly exciting are the recent advances in the etiology of schizophrenia, both genetic and environmental. Collaboration among geneticists around the world has enabled genome-wide association studies on almost 50,000 DNA samples and has revealed 3 genetic pathways to disrupted brain development, which lead to schizophrenia in early adulthood. Those genetic pathways include:

1. Susceptibility genes—more than 340 of them—are found significantly more often in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population. These risk genes are scattered across all 23 pairs of chromosomes. They influence neurotransmitter functions, neuroplasticity, and immune regulation. The huge task that lies ahead is identifying what each of the risk genes disrupts in brain structure and/or function.

2. Copy number variants (CNVs), such as deletions (1 allele instead of the normal 2) or duplications (3 alleles), are much more frequent in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population. That means too little or too much protein is made, which can disrupt the 4 stages of brain development (proliferation, migration, differentiation, and elimination).

3. de novo nonsense mutations, leading to complete absence of protein coding by the affected genes, with adverse ripple effects on brain development.

Approximately 10,000 genes (close to 50% of all 22,000 coding genes in the human genome) are involved in constructing the human brain. The latest estimate is that 79% of the hundreds of biotypes of schizophrenia are genetic in etiology.

In addition, multiple environmental factors can disrupt brain development and lead to schizophrenia. These include older paternal age (>45 years) at the time of conception, pregnancy complications (infections, gestational diabetes, vitamin D deficiency, hypoxia during delivery), childhood maltreatment (sexual or physical abuse or neglect) in the first 5 to 6 years of life, as well as migration and urbanicity (being born and raised in a large metropolitan area).

The bottom line: Schizophrenia is not only very complex, but also an extremely heterogeneous brain syndrome, both biologically and clinically. Psychiatric practitioners are fully cognizant of the extensive clinical variability in patients with schizophrenia, including the presence, absence, or severity of various signs and symptoms, such as insight, delusions, hallucinations, conceptual disorganization, bizarre behaviors, emotional withdrawal, agitation, depression, suicidality, anxiety, substance use, somatic concerns, hostility, idiosyncratic mannerisms, blunted affect, apathy, avolition, self-neglect, poor attention, memory impairment, and problems with decision-making, planning ahead, or organizing one’s life.

In addition, heterogeneity is encountered in such variables as age of onset, minor physical anomalies, soft neurologic signs, naturally occurring movement disorders, premorbid functioning, family history, general medical comorbidities, psychiatry comorbidities, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, neurophysiological deviations (pre-pulse inhibition, p50, p300, N100, mismatch negativity, smooth pursuit eye movements), pituitary volume, rapidity and extent of response to antipsychotics, type and frequency of adverse effects, and functional disability or restoration of vocational functioning.

No wonder, then, given the daunting biologic and clinical heterogeneity of this complex brain syndrome, that myriad hypotheses have been proposed over the past century. The Table lists approximately 50 hypotheses, some discredited but others plausible and still viable. The most absurd hypotheses are the double bind theory of schizophrenia in the 1950s by Gregory Bateson et al, or the latent homosexuality theory of Freud. Some hypotheses may be related to a specific biotype within the schizophrenia syndrome (such as the megavitamin theory) that do not apply to other biotypes. Some of the hypotheses seem to be the product of the rich imagination of an enthusiastic researcher based on limited data.

Another consequence of the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia is the large number of “lab tests” that have been reported over the past few decades.1 Those hundreds of biomarkers probably mirror the biologies of the numerous disease subtypes within the schizophrenia syndrome. Some are blood tests, others neurophysiological or neuroimaging, others molecular or genetic, along with many postmortem tissue markers. Obviously, none of these “lab tests” can be used clinically because there would be an unacceptably large number of false positives and false negatives when applied to a heterogeneous sample of patients with schizophrenia.

Heterogeneity also represents a formidable challenge for researchers. Replication of a research finding by investigators across the world can be quite challenging because of the variable composition of biotypes in different countries. This heterogeneity also complicates FDA clinical trials by pharmaceutical companies seeking approval for a new drug to treat schizophrenia. The FDA requires use of DSM diagnostic criteria, which would include patients with similar clinical symptoms, but who can vary widely at the biological level. This results in failed clinical trials where only 20% or 30% of patients with schizophrenia show significant improvement compared with placebo. Given the advances in schizophrenia, a better strategy is to recruit participants who share a specific biomarker to assemble a biologically more homogeneous sample of schizophrenia. If the clinical trial is successful, the same biomarker can then be used by practitioners to predict response to the new drug. That would fulfill the aspirations of applying precision medicine in psychiatric practice.

The famous Eugen Bleuler (whose sister suffered from schizophrenia) was prescient when a century ago he published his classic book titled Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias.2 His astute clinical observations led him to recognize the heterogeneity of the syndrome whose name he coined (schizophrenia, or disconnected thoughts). His conceptualization of schizophrenia as a spectrum of disorders of variable outcomes contrasted with that of Emil Kraepelin’s model,3 which regarded dementia praecox as a single, homogeneous, deteriorating disease. But neither Bleuler nor Kraepelin, both of whom relied on clinical observations without any biologic studies, could even imagine the spectacular complexity of the neurobiology of the schizophrenia syndrome and how difficult it is to identify its many biotypes. The monumental advances in neuroscience and neurogenetics, with their sophisticated methodologies, will eventually decipher the mysteries of this neuropsychiatric syndrome, which generates so many aberrations in thought, affect, mood, cognition, and behavior, often leading to severe functional disability among young adults, and untold anguish for their families.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

Islands of knowledge in an ocean of ignorance. That summarizes the advances in unraveling the enigma of schizophrenia, arguably the most complex psychiatric brain disorder. The more breakthroughs are made, the more questions emerge.

Progress is definitely being made and the published literature, replete with new findings, is growing logarithmically. Particularly exciting are the recent advances in the etiology of schizophrenia, both genetic and environmental. Collaboration among geneticists around the world has enabled genome-wide association studies on almost 50,000 DNA samples and has revealed 3 genetic pathways to disrupted brain development, which lead to schizophrenia in early adulthood. Those genetic pathways include:

1. Susceptibility genes—more than 340 of them—are found significantly more often in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population. These risk genes are scattered across all 23 pairs of chromosomes. They influence neurotransmitter functions, neuroplasticity, and immune regulation. The huge task that lies ahead is identifying what each of the risk genes disrupts in brain structure and/or function.

2. Copy number variants (CNVs), such as deletions (1 allele instead of the normal 2) or duplications (3 alleles), are much more frequent in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population. That means too little or too much protein is made, which can disrupt the 4 stages of brain development (proliferation, migration, differentiation, and elimination).

3. de novo nonsense mutations, leading to complete absence of protein coding by the affected genes, with adverse ripple effects on brain development.

Approximately 10,000 genes (close to 50% of all 22,000 coding genes in the human genome) are involved in constructing the human brain. The latest estimate is that 79% of the hundreds of biotypes of schizophrenia are genetic in etiology.

In addition, multiple environmental factors can disrupt brain development and lead to schizophrenia. These include older paternal age (>45 years) at the time of conception, pregnancy complications (infections, gestational diabetes, vitamin D deficiency, hypoxia during delivery), childhood maltreatment (sexual or physical abuse or neglect) in the first 5 to 6 years of life, as well as migration and urbanicity (being born and raised in a large metropolitan area).

The bottom line: Schizophrenia is not only very complex, but also an extremely heterogeneous brain syndrome, both biologically and clinically. Psychiatric practitioners are fully cognizant of the extensive clinical variability in patients with schizophrenia, including the presence, absence, or severity of various signs and symptoms, such as insight, delusions, hallucinations, conceptual disorganization, bizarre behaviors, emotional withdrawal, agitation, depression, suicidality, anxiety, substance use, somatic concerns, hostility, idiosyncratic mannerisms, blunted affect, apathy, avolition, self-neglect, poor attention, memory impairment, and problems with decision-making, planning ahead, or organizing one’s life.

In addition, heterogeneity is encountered in such variables as age of onset, minor physical anomalies, soft neurologic signs, naturally occurring movement disorders, premorbid functioning, family history, general medical comorbidities, psychiatry comorbidities, structural brain abnormalities on neuroimaging, neurophysiological deviations (pre-pulse inhibition, p50, p300, N100, mismatch negativity, smooth pursuit eye movements), pituitary volume, rapidity and extent of response to antipsychotics, type and frequency of adverse effects, and functional disability or restoration of vocational functioning.

No wonder, then, given the daunting biologic and clinical heterogeneity of this complex brain syndrome, that myriad hypotheses have been proposed over the past century. The Table lists approximately 50 hypotheses, some discredited but others plausible and still viable. The most absurd hypotheses are the double bind theory of schizophrenia in the 1950s by Gregory Bateson et al, or the latent homosexuality theory of Freud. Some hypotheses may be related to a specific biotype within the schizophrenia syndrome (such as the megavitamin theory) that do not apply to other biotypes. Some of the hypotheses seem to be the product of the rich imagination of an enthusiastic researcher based on limited data.

Another consequence of the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia is the large number of “lab tests” that have been reported over the past few decades.1 Those hundreds of biomarkers probably mirror the biologies of the numerous disease subtypes within the schizophrenia syndrome. Some are blood tests, others neurophysiological or neuroimaging, others molecular or genetic, along with many postmortem tissue markers. Obviously, none of these “lab tests” can be used clinically because there would be an unacceptably large number of false positives and false negatives when applied to a heterogeneous sample of patients with schizophrenia.

Heterogeneity also represents a formidable challenge for researchers. Replication of a research finding by investigators across the world can be quite challenging because of the variable composition of biotypes in different countries. This heterogeneity also complicates FDA clinical trials by pharmaceutical companies seeking approval for a new drug to treat schizophrenia. The FDA requires use of DSM diagnostic criteria, which would include patients with similar clinical symptoms, but who can vary widely at the biological level. This results in failed clinical trials where only 20% or 30% of patients with schizophrenia show significant improvement compared with placebo. Given the advances in schizophrenia, a better strategy is to recruit participants who share a specific biomarker to assemble a biologically more homogeneous sample of schizophrenia. If the clinical trial is successful, the same biomarker can then be used by practitioners to predict response to the new drug. That would fulfill the aspirations of applying precision medicine in psychiatric practice.

The famous Eugen Bleuler (whose sister suffered from schizophrenia) was prescient when a century ago he published his classic book titled Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias.2 His astute clinical observations led him to recognize the heterogeneity of the syndrome whose name he coined (schizophrenia, or disconnected thoughts). His conceptualization of schizophrenia as a spectrum of disorders of variable outcomes contrasted with that of Emil Kraepelin’s model,3 which regarded dementia praecox as a single, homogeneous, deteriorating disease. But neither Bleuler nor Kraepelin, both of whom relied on clinical observations without any biologic studies, could even imagine the spectacular complexity of the neurobiology of the schizophrenia syndrome and how difficult it is to identify its many biotypes. The monumental advances in neuroscience and neurogenetics, with their sophisticated methodologies, will eventually decipher the mysteries of this neuropsychiatric syndrome, which generates so many aberrations in thought, affect, mood, cognition, and behavior, often leading to severe functional disability among young adults, and untold anguish for their families.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: Few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

2. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

3. Hippius H, Muller N. The work of Emil Kraepelin and his research group in Munich. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(Suppl 2):3-11.

1. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: Few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

2. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

3. Hippius H, Muller N. The work of Emil Kraepelin and his research group in Munich. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(Suppl 2):3-11.

Change is upon us

It shouldn’t be a surprise. Although we don’t necessarily welcome change, change is a constant in our world. Nothing new here – it has always been so. Most of us dread change, because of our natural apprehension of the unknown. New ideas and ways of functioning that disrupt the status quo require effort, adjustment, and learning with no guarantee of success.

In my lifetime alone, ways of communicating with one another have undergone so many changes that it’s dizzying to contemplate. When I was a child in rural Oregon, our means of communicating with friends and family was the “party line” (by which was meant, not the political party, but the community’s telephone connection). We didn’t have a separate phone number, but rather a ring that was specific to our family. Most people on the line knew each other’s ring and could surreptitiously listen in if curiosity got the best of them. Privacy was not a big consideration.

Fast forward just over a half-century, and our system of communication is barely recognizable: 24/7 connectivity on hand-held electronic devices to any part of the world, SMS, Skype, Facebook, texting. Instantaneous worldwide communication is a given from anywhere, even the golf course.

Yes, there are hazards in this convenience. Recent events have demonstrated the lack of privacy and security of our communications, and what you see is not necessarily what it appears to be. It has become abundantly clear just how fragile the process of exchanging valid information can be. And yet, who would wish to erase all of this convenience to go back to the old days before the Internet? I doubt seriously that many surgeons would exchange the old world of limited access to information and communication for our era of immersive connectivity.

A comparable progression has occurred in our methods of professional learning and moving our corpus of knowledge forward. For the past half-century and more, new techniques, knowledge, and ideas have been presented in meetings of established societies and published in peer-reviewed journals. Unfortunately, not all who might benefit from these new ideas have access to them. If you belong to the society, can afford the time and money to attend the meeting, and work in an institution that subscribes to online access to all of the major journals, you can read them. Surgeons in independent practice in rural, remote communities likely do not have that luxury. ACS Surgery News has had many functions but one of the most important has been to serve surgeons in those remote communities as well as for others who simply wanted the convenience of ready access to new information all in one place.

Unfortunately, print publications are becoming more expensive to produce and mail, and advertising dollars to subsidize them are shrinking. Thus, Tyler Hughes and I, the coeditors of ACS Surgery News, were informed that our publication will cease production after the December 2018 issue. We and the ACS leadership huddled to find a way to continue what we all believe is a benefit to our ACS Fellows, particularly those who practice in small rural hospitals. The answer was right in front of us: The ACS Communities, to which all Fellows have online access. So that is our plan: Tyler and I will continue to write our “homespun” commentaries, and our editorial board will contribute concise articles that summarize the “latest and greatest” presentations at meetings they attend or from recently published articles in major journals across the spectrum of general surgery and surgical specialties. If readers have questions or comments, they will be able to communicate with the authors for clarification. We hope that this structure and content will benefit our surgical colleagues. Look for our new ACS Communities presence in January 2019.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery emerita in the department of surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

It shouldn’t be a surprise. Although we don’t necessarily welcome change, change is a constant in our world. Nothing new here – it has always been so. Most of us dread change, because of our natural apprehension of the unknown. New ideas and ways of functioning that disrupt the status quo require effort, adjustment, and learning with no guarantee of success.

In my lifetime alone, ways of communicating with one another have undergone so many changes that it’s dizzying to contemplate. When I was a child in rural Oregon, our means of communicating with friends and family was the “party line” (by which was meant, not the political party, but the community’s telephone connection). We didn’t have a separate phone number, but rather a ring that was specific to our family. Most people on the line knew each other’s ring and could surreptitiously listen in if curiosity got the best of them. Privacy was not a big consideration.

Fast forward just over a half-century, and our system of communication is barely recognizable: 24/7 connectivity on hand-held electronic devices to any part of the world, SMS, Skype, Facebook, texting. Instantaneous worldwide communication is a given from anywhere, even the golf course.

Yes, there are hazards in this convenience. Recent events have demonstrated the lack of privacy and security of our communications, and what you see is not necessarily what it appears to be. It has become abundantly clear just how fragile the process of exchanging valid information can be. And yet, who would wish to erase all of this convenience to go back to the old days before the Internet? I doubt seriously that many surgeons would exchange the old world of limited access to information and communication for our era of immersive connectivity.

A comparable progression has occurred in our methods of professional learning and moving our corpus of knowledge forward. For the past half-century and more, new techniques, knowledge, and ideas have been presented in meetings of established societies and published in peer-reviewed journals. Unfortunately, not all who might benefit from these new ideas have access to them. If you belong to the society, can afford the time and money to attend the meeting, and work in an institution that subscribes to online access to all of the major journals, you can read them. Surgeons in independent practice in rural, remote communities likely do not have that luxury. ACS Surgery News has had many functions but one of the most important has been to serve surgeons in those remote communities as well as for others who simply wanted the convenience of ready access to new information all in one place.

Unfortunately, print publications are becoming more expensive to produce and mail, and advertising dollars to subsidize them are shrinking. Thus, Tyler Hughes and I, the coeditors of ACS Surgery News, were informed that our publication will cease production after the December 2018 issue. We and the ACS leadership huddled to find a way to continue what we all believe is a benefit to our ACS Fellows, particularly those who practice in small rural hospitals. The answer was right in front of us: The ACS Communities, to which all Fellows have online access. So that is our plan: Tyler and I will continue to write our “homespun” commentaries, and our editorial board will contribute concise articles that summarize the “latest and greatest” presentations at meetings they attend or from recently published articles in major journals across the spectrum of general surgery and surgical specialties. If readers have questions or comments, they will be able to communicate with the authors for clarification. We hope that this structure and content will benefit our surgical colleagues. Look for our new ACS Communities presence in January 2019.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery emerita in the department of surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

It shouldn’t be a surprise. Although we don’t necessarily welcome change, change is a constant in our world. Nothing new here – it has always been so. Most of us dread change, because of our natural apprehension of the unknown. New ideas and ways of functioning that disrupt the status quo require effort, adjustment, and learning with no guarantee of success.

In my lifetime alone, ways of communicating with one another have undergone so many changes that it’s dizzying to contemplate. When I was a child in rural Oregon, our means of communicating with friends and family was the “party line” (by which was meant, not the political party, but the community’s telephone connection). We didn’t have a separate phone number, but rather a ring that was specific to our family. Most people on the line knew each other’s ring and could surreptitiously listen in if curiosity got the best of them. Privacy was not a big consideration.

Fast forward just over a half-century, and our system of communication is barely recognizable: 24/7 connectivity on hand-held electronic devices to any part of the world, SMS, Skype, Facebook, texting. Instantaneous worldwide communication is a given from anywhere, even the golf course.

Yes, there are hazards in this convenience. Recent events have demonstrated the lack of privacy and security of our communications, and what you see is not necessarily what it appears to be. It has become abundantly clear just how fragile the process of exchanging valid information can be. And yet, who would wish to erase all of this convenience to go back to the old days before the Internet? I doubt seriously that many surgeons would exchange the old world of limited access to information and communication for our era of immersive connectivity.

A comparable progression has occurred in our methods of professional learning and moving our corpus of knowledge forward. For the past half-century and more, new techniques, knowledge, and ideas have been presented in meetings of established societies and published in peer-reviewed journals. Unfortunately, not all who might benefit from these new ideas have access to them. If you belong to the society, can afford the time and money to attend the meeting, and work in an institution that subscribes to online access to all of the major journals, you can read them. Surgeons in independent practice in rural, remote communities likely do not have that luxury. ACS Surgery News has had many functions but one of the most important has been to serve surgeons in those remote communities as well as for others who simply wanted the convenience of ready access to new information all in one place.

Unfortunately, print publications are becoming more expensive to produce and mail, and advertising dollars to subsidize them are shrinking. Thus, Tyler Hughes and I, the coeditors of ACS Surgery News, were informed that our publication will cease production after the December 2018 issue. We and the ACS leadership huddled to find a way to continue what we all believe is a benefit to our ACS Fellows, particularly those who practice in small rural hospitals. The answer was right in front of us: The ACS Communities, to which all Fellows have online access. So that is our plan: Tyler and I will continue to write our “homespun” commentaries, and our editorial board will contribute concise articles that summarize the “latest and greatest” presentations at meetings they attend or from recently published articles in major journals across the spectrum of general surgery and surgical specialties. If readers have questions or comments, they will be able to communicate with the authors for clarification. We hope that this structure and content will benefit our surgical colleagues. Look for our new ACS Communities presence in January 2019.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery emerita in the department of surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Psychopharmacology 3.0

There is little doubt that the psychopharmacology revolution has been transformational for psychiatry and is also credited for sparking the momentous neuroscience advances of the past half century.

The field of psychiatry, dominated by Freudian psychology for decades, radically evolved from psychoanalysis to pharmacotherapy with the discovery that serious mental disorders are treatable with medications, thus dispensing with the couch.

Prior to 1952, the prevailing dogma was that “madness is irreversible.” That’s why millions of patients with various psychiatric disorders were locked up in institutions, which added to the stigma of mental illness. Then came the first antipsychotic drug, chlorpromazine, which “magically” eliminated the delusions and hallucinations of patients who had been hospitalized for years. That serendipitous and historic discovery was as transformational for psychiatry as penicillin was for infections (yet inexplicably, only the discovery of penicillin received a Nobel Prize). Most people today do not know that before chlorpromazine, 50% of all hospital beds in the U.S. were occupied by psychiatric patients. The massive shuttering of state hospitals in the 1970s and ’80s was a direct consequence of the widespread use of chlorpromazine and its cohort of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs).

That was Psychopharmacology 1.0, spanning the period 1952 to 1987. It included dozens of FGAs belonging to 6 classes: phenothiazines, thioxanthenes, butyrophenones, dibenzazepines, dihydroindolones, and dibenzodiazepines. Psychopharmacology 1.0 also included monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants for depression, and lithium for bipolar mania. Ironically, clozapine, the incognito seed template of the second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) class, was synthesized in 1959 with the early wave of FGAs, and launched in Europe in 1972, only to be withdrawn in 1974 due to agranulocytosis-induced deaths not recognized during the clinical trials.

The late 1980s ushered in Psychopharmacology 2.0, which was also transformative. It began in 1987 with the introduction of fluoxetine, the first selective serotonin receptor inhibitor. Then clozapine was resurrected in 1988 as the first FDA-approved drug for refractory schizophrenia. Being the first SGA (no acute extrapyramidal side effects at all, in contrast to all FGAs), it became the “mechanistic model” for all other SGA agents, which were introduced starting in 1993. All SGAs were designed by pharmaceutical companies’ medicinal chemists to mimic clozapine’s receptor profile: far stronger affinity to serotonin 5HT-2A receptors than to dopamine D2 receptors. Three partial agonists and several heterocyclic antidepressants were also introduced during this 2.0 era, which continued until approximately 2017. Of the 11 SGAs that were initially approved for schizophrenia, 7 also were approved for bipolar mania, and 2 received an FDA indication for bipolar depression, thus addressing a glaring unmet need.

Psychopharmacology 3.0 has already begun. Its seeds started sprouting over the past few years with the landmark studies of intravenous ketamine, which was demonstrated to reverse severe and refractory depression and suicidal urges within hours of injection. The first ketamine product, esketamine, an intranasal formulation, is expected to be approved by the FDA soon. In the same vein, other rapid-acting antidepressants, a welcome paradigm shift, are being developed, including IV scopolamine, IV rapastinel, and inhalable nitrous oxide.

Three novel and important pharmacologic agents have arrived in this 3.0 era:

- Pimavanserin, a serotonin 5HT-2A inverse agonist, the first and only non-dopamine–blocking antipsychotic approved by the FDA for the delusions and hallucinations of Parkinson’s disease psychosis. It is currently in clinical trials for schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease psychosis (for which nothing is yet approved).

- Valbenazine, the first drug approved for tardive dyskinesia (TD), the treatment of which had been elusive and remained a huge unmet need for 60 years. Its novel mechanism of action is inhibition of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), which reduces the putative dopamine supersensitivity of TD.

- Deutetrabenazine, which was also approved for TD a few months after valbenazine, and has the same mechanism of action. It also was approved for Huntington’s chorea.

Continue to: Another important feature...

Another important feature of Psychopharmacology 3.0 is the repurposing of hallucinogens into novel therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.1 The opioid system is being recognized as another key player in depression, with many studies showing buprenorphine has antidepressant and anti-suicidal properties2 and the recent finding that pre-treatment with naloxone blocks the rapid antidepressive effects of ketamine.3 This finding casts doubt on the notion that the antidepressant mechanism of action of ketamine is solely mediated via its antagonism of the glutamate N-methyl-

These early developments in Psychopharmacology 3.0 augur well for the future. Companies in the pharmaceutical industry (which are hated by many, and even demonized and kept at arm’s length by major medical schools) are, in fact, the only entities in the world that develop new medications for psychiatric disorders, 82% of which still have no FDA-approved drug.4 Psychiatric researchers and clinicians should collaborate and advise the pharmaceutical companies about the urgent or unmet needs of psychiatric patients so they can target those unmet needs with their massive R&D resources.

In that spirit, here is my wish list of therapeutic targets that I hope will emerge during the Psychopharmacology 3.0 era and beyond:

1. New mechanisms of action for antipsychotics, based on emerging neurobiological research in schizophrenia and related psychoses, such as:

- Inhibit microglia activation

- Repair mitochondrial dysfunction

- Modulate the hypofunctional NMDA receptors

- Inhibit apoptosis

- Enhance neurogenesis

- Repair myelin pathology

- Inhibit neuroinflammation and oxidative stress

- Increase neurotropic growth factors

- Neurosteroid therapies (including estrogen)

- Exploit the microbiome influence on both the enteric and cephalic brains

2. Long-acting injectable antidepressants and mood stabilizers, because there is a malignant transformation into treatment-resistance in mood disorders after recurrent episodes due to nonadherence.5

3. Treatments for personality disorders, especially borderline and antisocial personality disorders.

4. An effective treatment for alcoholism.

5. Pharmacotherapy for aggression.

6. Vaccines for substance use.

7. Stage-specific pharmacotherapies (because the neurobiology of prodromal, first-episode, and multiple-episode patients have been shown to be quite different).

8. Drugs for epigenetic modulation to inhibit risk genes and to over-express protective genes.

It may take decades and hundreds of billions (even trillions) of R&D investment to accomplish the above, but I remain excited about the prospects of astounding psychopharmacologic advances to treat the disorders of the mind. Precision psychiatry advances will also expedite the selection of the right medication for each patient by employing predictive biomarkers. Breakthrough methodologies, such as pluripotent stem cells, opto-genetics, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), promise to revolutionize the biology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of various neuropsychiatric disorders.

The future of psychopharmacology is bright, if adequate resources are invested. The current direct and indirect costs of mental disorders and addictions are in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Only intensive research and disruptive discoveries will have the salutary dual effect of healing disease and reducing the economic burden of neuropsychiatric disorders. Psychopharmacology 3.0 advances, along with nonpharmacologic therapies such as neuromodulation (electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, and a dozen other techniques in development). Together with the indispensable evidence-based psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy, psychopharmacology represents the leading edge of progress in psychiatric treatment. The psychiatrists of 1952 could only fantasize about what has since become a reality in healing ailing minds.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected]

1. Nasrallah, HA. Maddening therapies: How hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):19-21.

2. Serafini G, Adavastro G, Canepa G, et al. The efficacy of buprenorphine in major depression, treatment-resistant depression and suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8). doi: 10.3390/ijms19082410.

3. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020138. [Epub ahead of print].

4. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders. The majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatr. 2009;2(1):29-36.

5. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198.

There is little doubt that the psychopharmacology revolution has been transformational for psychiatry and is also credited for sparking the momentous neuroscience advances of the past half century.

The field of psychiatry, dominated by Freudian psychology for decades, radically evolved from psychoanalysis to pharmacotherapy with the discovery that serious mental disorders are treatable with medications, thus dispensing with the couch.

Prior to 1952, the prevailing dogma was that “madness is irreversible.” That’s why millions of patients with various psychiatric disorders were locked up in institutions, which added to the stigma of mental illness. Then came the first antipsychotic drug, chlorpromazine, which “magically” eliminated the delusions and hallucinations of patients who had been hospitalized for years. That serendipitous and historic discovery was as transformational for psychiatry as penicillin was for infections (yet inexplicably, only the discovery of penicillin received a Nobel Prize). Most people today do not know that before chlorpromazine, 50% of all hospital beds in the U.S. were occupied by psychiatric patients. The massive shuttering of state hospitals in the 1970s and ’80s was a direct consequence of the widespread use of chlorpromazine and its cohort of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs).

That was Psychopharmacology 1.0, spanning the period 1952 to 1987. It included dozens of FGAs belonging to 6 classes: phenothiazines, thioxanthenes, butyrophenones, dibenzazepines, dihydroindolones, and dibenzodiazepines. Psychopharmacology 1.0 also included monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants for depression, and lithium for bipolar mania. Ironically, clozapine, the incognito seed template of the second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) class, was synthesized in 1959 with the early wave of FGAs, and launched in Europe in 1972, only to be withdrawn in 1974 due to agranulocytosis-induced deaths not recognized during the clinical trials.

The late 1980s ushered in Psychopharmacology 2.0, which was also transformative. It began in 1987 with the introduction of fluoxetine, the first selective serotonin receptor inhibitor. Then clozapine was resurrected in 1988 as the first FDA-approved drug for refractory schizophrenia. Being the first SGA (no acute extrapyramidal side effects at all, in contrast to all FGAs), it became the “mechanistic model” for all other SGA agents, which were introduced starting in 1993. All SGAs were designed by pharmaceutical companies’ medicinal chemists to mimic clozapine’s receptor profile: far stronger affinity to serotonin 5HT-2A receptors than to dopamine D2 receptors. Three partial agonists and several heterocyclic antidepressants were also introduced during this 2.0 era, which continued until approximately 2017. Of the 11 SGAs that were initially approved for schizophrenia, 7 also were approved for bipolar mania, and 2 received an FDA indication for bipolar depression, thus addressing a glaring unmet need.

Psychopharmacology 3.0 has already begun. Its seeds started sprouting over the past few years with the landmark studies of intravenous ketamine, which was demonstrated to reverse severe and refractory depression and suicidal urges within hours of injection. The first ketamine product, esketamine, an intranasal formulation, is expected to be approved by the FDA soon. In the same vein, other rapid-acting antidepressants, a welcome paradigm shift, are being developed, including IV scopolamine, IV rapastinel, and inhalable nitrous oxide.

Three novel and important pharmacologic agents have arrived in this 3.0 era:

- Pimavanserin, a serotonin 5HT-2A inverse agonist, the first and only non-dopamine–blocking antipsychotic approved by the FDA for the delusions and hallucinations of Parkinson’s disease psychosis. It is currently in clinical trials for schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease psychosis (for which nothing is yet approved).

- Valbenazine, the first drug approved for tardive dyskinesia (TD), the treatment of which had been elusive and remained a huge unmet need for 60 years. Its novel mechanism of action is inhibition of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), which reduces the putative dopamine supersensitivity of TD.

- Deutetrabenazine, which was also approved for TD a few months after valbenazine, and has the same mechanism of action. It also was approved for Huntington’s chorea.

Continue to: Another important feature...

Another important feature of Psychopharmacology 3.0 is the repurposing of hallucinogens into novel therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.1 The opioid system is being recognized as another key player in depression, with many studies showing buprenorphine has antidepressant and anti-suicidal properties2 and the recent finding that pre-treatment with naloxone blocks the rapid antidepressive effects of ketamine.3 This finding casts doubt on the notion that the antidepressant mechanism of action of ketamine is solely mediated via its antagonism of the glutamate N-methyl-

These early developments in Psychopharmacology 3.0 augur well for the future. Companies in the pharmaceutical industry (which are hated by many, and even demonized and kept at arm’s length by major medical schools) are, in fact, the only entities in the world that develop new medications for psychiatric disorders, 82% of which still have no FDA-approved drug.4 Psychiatric researchers and clinicians should collaborate and advise the pharmaceutical companies about the urgent or unmet needs of psychiatric patients so they can target those unmet needs with their massive R&D resources.

In that spirit, here is my wish list of therapeutic targets that I hope will emerge during the Psychopharmacology 3.0 era and beyond:

1. New mechanisms of action for antipsychotics, based on emerging neurobiological research in schizophrenia and related psychoses, such as:

- Inhibit microglia activation

- Repair mitochondrial dysfunction

- Modulate the hypofunctional NMDA receptors

- Inhibit apoptosis

- Enhance neurogenesis

- Repair myelin pathology

- Inhibit neuroinflammation and oxidative stress

- Increase neurotropic growth factors

- Neurosteroid therapies (including estrogen)

- Exploit the microbiome influence on both the enteric and cephalic brains

2. Long-acting injectable antidepressants and mood stabilizers, because there is a malignant transformation into treatment-resistance in mood disorders after recurrent episodes due to nonadherence.5

3. Treatments for personality disorders, especially borderline and antisocial personality disorders.

4. An effective treatment for alcoholism.

5. Pharmacotherapy for aggression.

6. Vaccines for substance use.

7. Stage-specific pharmacotherapies (because the neurobiology of prodromal, first-episode, and multiple-episode patients have been shown to be quite different).

8. Drugs for epigenetic modulation to inhibit risk genes and to over-express protective genes.

It may take decades and hundreds of billions (even trillions) of R&D investment to accomplish the above, but I remain excited about the prospects of astounding psychopharmacologic advances to treat the disorders of the mind. Precision psychiatry advances will also expedite the selection of the right medication for each patient by employing predictive biomarkers. Breakthrough methodologies, such as pluripotent stem cells, opto-genetics, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), promise to revolutionize the biology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of various neuropsychiatric disorders.

The future of psychopharmacology is bright, if adequate resources are invested. The current direct and indirect costs of mental disorders and addictions are in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Only intensive research and disruptive discoveries will have the salutary dual effect of healing disease and reducing the economic burden of neuropsychiatric disorders. Psychopharmacology 3.0 advances, along with nonpharmacologic therapies such as neuromodulation (electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, and a dozen other techniques in development). Together with the indispensable evidence-based psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy, psychopharmacology represents the leading edge of progress in psychiatric treatment. The psychiatrists of 1952 could only fantasize about what has since become a reality in healing ailing minds.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected]

There is little doubt that the psychopharmacology revolution has been transformational for psychiatry and is also credited for sparking the momentous neuroscience advances of the past half century.

The field of psychiatry, dominated by Freudian psychology for decades, radically evolved from psychoanalysis to pharmacotherapy with the discovery that serious mental disorders are treatable with medications, thus dispensing with the couch.

Prior to 1952, the prevailing dogma was that “madness is irreversible.” That’s why millions of patients with various psychiatric disorders were locked up in institutions, which added to the stigma of mental illness. Then came the first antipsychotic drug, chlorpromazine, which “magically” eliminated the delusions and hallucinations of patients who had been hospitalized for years. That serendipitous and historic discovery was as transformational for psychiatry as penicillin was for infections (yet inexplicably, only the discovery of penicillin received a Nobel Prize). Most people today do not know that before chlorpromazine, 50% of all hospital beds in the U.S. were occupied by psychiatric patients. The massive shuttering of state hospitals in the 1970s and ’80s was a direct consequence of the widespread use of chlorpromazine and its cohort of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs).

That was Psychopharmacology 1.0, spanning the period 1952 to 1987. It included dozens of FGAs belonging to 6 classes: phenothiazines, thioxanthenes, butyrophenones, dibenzazepines, dihydroindolones, and dibenzodiazepines. Psychopharmacology 1.0 also included monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants for depression, and lithium for bipolar mania. Ironically, clozapine, the incognito seed template of the second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) class, was synthesized in 1959 with the early wave of FGAs, and launched in Europe in 1972, only to be withdrawn in 1974 due to agranulocytosis-induced deaths not recognized during the clinical trials.

The late 1980s ushered in Psychopharmacology 2.0, which was also transformative. It began in 1987 with the introduction of fluoxetine, the first selective serotonin receptor inhibitor. Then clozapine was resurrected in 1988 as the first FDA-approved drug for refractory schizophrenia. Being the first SGA (no acute extrapyramidal side effects at all, in contrast to all FGAs), it became the “mechanistic model” for all other SGA agents, which were introduced starting in 1993. All SGAs were designed by pharmaceutical companies’ medicinal chemists to mimic clozapine’s receptor profile: far stronger affinity to serotonin 5HT-2A receptors than to dopamine D2 receptors. Three partial agonists and several heterocyclic antidepressants were also introduced during this 2.0 era, which continued until approximately 2017. Of the 11 SGAs that were initially approved for schizophrenia, 7 also were approved for bipolar mania, and 2 received an FDA indication for bipolar depression, thus addressing a glaring unmet need.

Psychopharmacology 3.0 has already begun. Its seeds started sprouting over the past few years with the landmark studies of intravenous ketamine, which was demonstrated to reverse severe and refractory depression and suicidal urges within hours of injection. The first ketamine product, esketamine, an intranasal formulation, is expected to be approved by the FDA soon. In the same vein, other rapid-acting antidepressants, a welcome paradigm shift, are being developed, including IV scopolamine, IV rapastinel, and inhalable nitrous oxide.

Three novel and important pharmacologic agents have arrived in this 3.0 era:

- Pimavanserin, a serotonin 5HT-2A inverse agonist, the first and only non-dopamine–blocking antipsychotic approved by the FDA for the delusions and hallucinations of Parkinson’s disease psychosis. It is currently in clinical trials for schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease psychosis (for which nothing is yet approved).

- Valbenazine, the first drug approved for tardive dyskinesia (TD), the treatment of which had been elusive and remained a huge unmet need for 60 years. Its novel mechanism of action is inhibition of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), which reduces the putative dopamine supersensitivity of TD.

- Deutetrabenazine, which was also approved for TD a few months after valbenazine, and has the same mechanism of action. It also was approved for Huntington’s chorea.

Continue to: Another important feature...

Another important feature of Psychopharmacology 3.0 is the repurposing of hallucinogens into novel therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.1 The opioid system is being recognized as another key player in depression, with many studies showing buprenorphine has antidepressant and anti-suicidal properties2 and the recent finding that pre-treatment with naloxone blocks the rapid antidepressive effects of ketamine.3 This finding casts doubt on the notion that the antidepressant mechanism of action of ketamine is solely mediated via its antagonism of the glutamate N-methyl-

These early developments in Psychopharmacology 3.0 augur well for the future. Companies in the pharmaceutical industry (which are hated by many, and even demonized and kept at arm’s length by major medical schools) are, in fact, the only entities in the world that develop new medications for psychiatric disorders, 82% of which still have no FDA-approved drug.4 Psychiatric researchers and clinicians should collaborate and advise the pharmaceutical companies about the urgent or unmet needs of psychiatric patients so they can target those unmet needs with their massive R&D resources.

In that spirit, here is my wish list of therapeutic targets that I hope will emerge during the Psychopharmacology 3.0 era and beyond:

1. New mechanisms of action for antipsychotics, based on emerging neurobiological research in schizophrenia and related psychoses, such as:

- Inhibit microglia activation

- Repair mitochondrial dysfunction

- Modulate the hypofunctional NMDA receptors

- Inhibit apoptosis

- Enhance neurogenesis

- Repair myelin pathology

- Inhibit neuroinflammation and oxidative stress

- Increase neurotropic growth factors

- Neurosteroid therapies (including estrogen)

- Exploit the microbiome influence on both the enteric and cephalic brains

2. Long-acting injectable antidepressants and mood stabilizers, because there is a malignant transformation into treatment-resistance in mood disorders after recurrent episodes due to nonadherence.5

3. Treatments for personality disorders, especially borderline and antisocial personality disorders.

4. An effective treatment for alcoholism.

5. Pharmacotherapy for aggression.

6. Vaccines for substance use.

7. Stage-specific pharmacotherapies (because the neurobiology of prodromal, first-episode, and multiple-episode patients have been shown to be quite different).

8. Drugs for epigenetic modulation to inhibit risk genes and to over-express protective genes.

It may take decades and hundreds of billions (even trillions) of R&D investment to accomplish the above, but I remain excited about the prospects of astounding psychopharmacologic advances to treat the disorders of the mind. Precision psychiatry advances will also expedite the selection of the right medication for each patient by employing predictive biomarkers. Breakthrough methodologies, such as pluripotent stem cells, opto-genetics, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), promise to revolutionize the biology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of various neuropsychiatric disorders.

The future of psychopharmacology is bright, if adequate resources are invested. The current direct and indirect costs of mental disorders and addictions are in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Only intensive research and disruptive discoveries will have the salutary dual effect of healing disease and reducing the economic burden of neuropsychiatric disorders. Psychopharmacology 3.0 advances, along with nonpharmacologic therapies such as neuromodulation (electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, and a dozen other techniques in development). Together with the indispensable evidence-based psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy, psychopharmacology represents the leading edge of progress in psychiatric treatment. The psychiatrists of 1952 could only fantasize about what has since become a reality in healing ailing minds.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected]

1. Nasrallah, HA. Maddening therapies: How hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):19-21.

2. Serafini G, Adavastro G, Canepa G, et al. The efficacy of buprenorphine in major depression, treatment-resistant depression and suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8). doi: 10.3390/ijms19082410.

3. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020138. [Epub ahead of print].

4. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders. The majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatr. 2009;2(1):29-36.

5. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198.

1. Nasrallah, HA. Maddening therapies: How hallucinogens morphed into novel treatments. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):19-21.

2. Serafini G, Adavastro G, Canepa G, et al. The efficacy of buprenorphine in major depression, treatment-resistant depression and suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8). doi: 10.3390/ijms19082410.

3. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020138. [Epub ahead of print].

4. Devulapalli KK, Nasrallah HA. An analysis of the high psychotropic off-label use in psychiatric disorders. The majority of psychiatric diagnoses have no approved drug. Asian J Psychiatr. 2009;2(1):29-36.

5. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198.

A physician’s response to observational studies of opioid prescribing

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

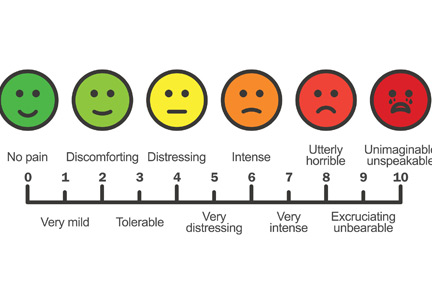

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

Death of a sales pitch

The EHR and our troubled health care system, Part 1

In 2000, the Institute of Medicine published “To Err Is Human,” a landmark study that warned that as many as 98,000 people die annually as a result of medical errors. One conclusion of the report stated, “When patients see multiple providers in different settings, none of whom has access to complete information, it becomes easier for things to go wrong.” Government and public reaction to the study resulted in the rushed integration of electronic health records into the U.S. medical system. EHR vendors promised solutions that included a dramatic reduction of preventable errors, a simplified system of physician communication, and the consolidation of a patient’s salient medical information into a single, transferable file. Now, almost 20 years later, these promises remain mostly unfilled. How did we get here?

Systems of medical records have been in place since 1600 B.C. For thousands of years, they consisted mainly of the patient’s diagnosis and the physician’s treatment. In 1968, the New England Journal of Medicine published the special article “Medical Records That Guide and Teach” by Lawrence L. Weed, MD. In the report, Dr. Weed advocated for the organization of medical records by problems rather than by a single diagnosis. This was the birth of our modern system. Medical records would now include lists of symptoms, findings, and problems that would organize the physician’s planning and allow third parties to confirm the initial diagnosis. Nearly concurrent with this publication, the next major innovation was developing in a very unusual location.

In 1999, Fortune magazine labeled Jack Welch “Manager of the Century” for his innovative work as CEO of General Electric. His techniques involved cutting waste and streamlining his workforce. While these methods were somewhat controversial, GE’s market value increased dramatically under his watch. The publishers at Fortune became interested in finding similar innovators in other fields. In this pursuit, they sent journalist Philip Longman to find the “Jack Welch” of health care.

Mr. Longman had recently lost his wife to breast cancer and was becoming obsessed with medical errors and health care quality integration. He set out to discover the best health care system in the United States. After months of research, Mr. Longman reached a startling conclusion. By nearly every metric, the Veterans Affairs system produced the highest quality of care. The key factor in upholding that quality appeared to be the EHR system VistA (Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture).

The development of VistA was a grassroots effort begun in the 1970s. Using Tandy computers and Wang processors, the VA “hardhats” sought to develop an electronic system for medical records and communication. This effort was initially opposed and driven underground by the central bureaucracy. Laptops were confiscated, people were fired. Still, development continued, and in 1978, the Decentralized Hospital Computer Program was launched at 20 VA sites. The national rollout occurred in 1994 under the name VistA.

VistA was developed by doctors, for doctors, and routinely enjoys the highest satisfaction rates among all available EHRs. VistA also is an open source model; its code is readily available on the VA website. After seeing the evidence of VistA’s efficacy, Representative Pete Stark (D-CA) introduced HR 6898 on Sept. 15, 2008. The bill would establish a large federal open source health IT system that private hospitals could leverage. The bill also mandated that only open source solutions would receive federal funding. As opposed to proprietary systems, open source models allow for rapid innovation, easy personal configuration, and incorporation of open source apps from unlimited numbers of contributors.

HR 6898 never passed, despite initial bipartisan support. By relying on lobbyists, marketing, and money, the proprietary EHR vendors killed the Stark bill. After a 4-month scramble, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) passed, with EHR vendor support. HITECH established a certification system for EHRs. While the Stark bill envisioned a single, open source network, there were soon hundreds of certified EHR systems in the United States.