User login

The tests that we order define us

May et al discuss one of the most common laboratory tests we order, the complete blood cell count, and how to interpret and unlock additional information that we often overlook.

Singh et al explain the utility and limitations of assessing hepatic fibrosis in patients with known liver disease using specialized and increasingly available imaging techniques in patients with common diseases that may progress to liver failure.

Using several clinical scenarios, Suresh explores the limitations of serologic testing in patients with a potential “autoimmune” or systemic inflammatory syndrome (which, based on new consultations I see in my rheumatology clinic, seems to be virtually everyone who has experienced pain or fatigue).

The Journal also continues our ongoing series on Smart Testing that has focused on tests and testing strategies that have a strong evidence basis to support or discourage their utilization in specific settings. But in most real-life clinical scenarios, relatively little directly applicable evidence can be brought to bear on our decision process with a specific patient. Hence the ongoing need for each of us to refine our clinical reasoning skills, and to recognize the continuing challenges facing the incorporation of artificial intelligence and algorithmic practice into the management of the individual patient sitting or lying in front of us.

The challenge is to balance input from Watson, “Dr. Google,” our accumulated anecdotal and group experience, and specific data from the patient’s physical examination and provided history. All these sources are valuable, and I believe that how we thoughtfully and purposefully weigh and incorporate this information into practice defines us as the clinicians we are.

May et al discuss one of the most common laboratory tests we order, the complete blood cell count, and how to interpret and unlock additional information that we often overlook.

Singh et al explain the utility and limitations of assessing hepatic fibrosis in patients with known liver disease using specialized and increasingly available imaging techniques in patients with common diseases that may progress to liver failure.

Using several clinical scenarios, Suresh explores the limitations of serologic testing in patients with a potential “autoimmune” or systemic inflammatory syndrome (which, based on new consultations I see in my rheumatology clinic, seems to be virtually everyone who has experienced pain or fatigue).

The Journal also continues our ongoing series on Smart Testing that has focused on tests and testing strategies that have a strong evidence basis to support or discourage their utilization in specific settings. But in most real-life clinical scenarios, relatively little directly applicable evidence can be brought to bear on our decision process with a specific patient. Hence the ongoing need for each of us to refine our clinical reasoning skills, and to recognize the continuing challenges facing the incorporation of artificial intelligence and algorithmic practice into the management of the individual patient sitting or lying in front of us.

The challenge is to balance input from Watson, “Dr. Google,” our accumulated anecdotal and group experience, and specific data from the patient’s physical examination and provided history. All these sources are valuable, and I believe that how we thoughtfully and purposefully weigh and incorporate this information into practice defines us as the clinicians we are.

May et al discuss one of the most common laboratory tests we order, the complete blood cell count, and how to interpret and unlock additional information that we often overlook.

Singh et al explain the utility and limitations of assessing hepatic fibrosis in patients with known liver disease using specialized and increasingly available imaging techniques in patients with common diseases that may progress to liver failure.

Using several clinical scenarios, Suresh explores the limitations of serologic testing in patients with a potential “autoimmune” or systemic inflammatory syndrome (which, based on new consultations I see in my rheumatology clinic, seems to be virtually everyone who has experienced pain or fatigue).

The Journal also continues our ongoing series on Smart Testing that has focused on tests and testing strategies that have a strong evidence basis to support or discourage their utilization in specific settings. But in most real-life clinical scenarios, relatively little directly applicable evidence can be brought to bear on our decision process with a specific patient. Hence the ongoing need for each of us to refine our clinical reasoning skills, and to recognize the continuing challenges facing the incorporation of artificial intelligence and algorithmic practice into the management of the individual patient sitting or lying in front of us.

The challenge is to balance input from Watson, “Dr. Google,” our accumulated anecdotal and group experience, and specific data from the patient’s physical examination and provided history. All these sources are valuable, and I believe that how we thoughtfully and purposefully weigh and incorporate this information into practice defines us as the clinicians we are.

Psychiatry and neurology: Sister neuroscience specialties with different approaches to the brain

Neurologists and psychiatrists diagnose and treat disorders of the brain’s hardware and software, respectively. The brain is a physically tangible structure, while its mind is virtual and intangible.

Not surprisingly, neurology and psychiatry have very different approaches to the assessment and treatment of brain and mind disorders. It reminds me of ophthalmology, where some of the faculty focus on the hardware of the eye (cornea, lens, and retina) while others focus on the major function of the eye—vision. Similarly, the mind is the major function of the brain.

Clinical neuroscience represents the shared foundational underpinnings of neurologists and psychiatrists, but their management of brain and mind disorders is understandably quite different, albeit with the same final goal: to repair and restore the structure and function of this divinely complex organ, the command and control center of the human soul and behavior.

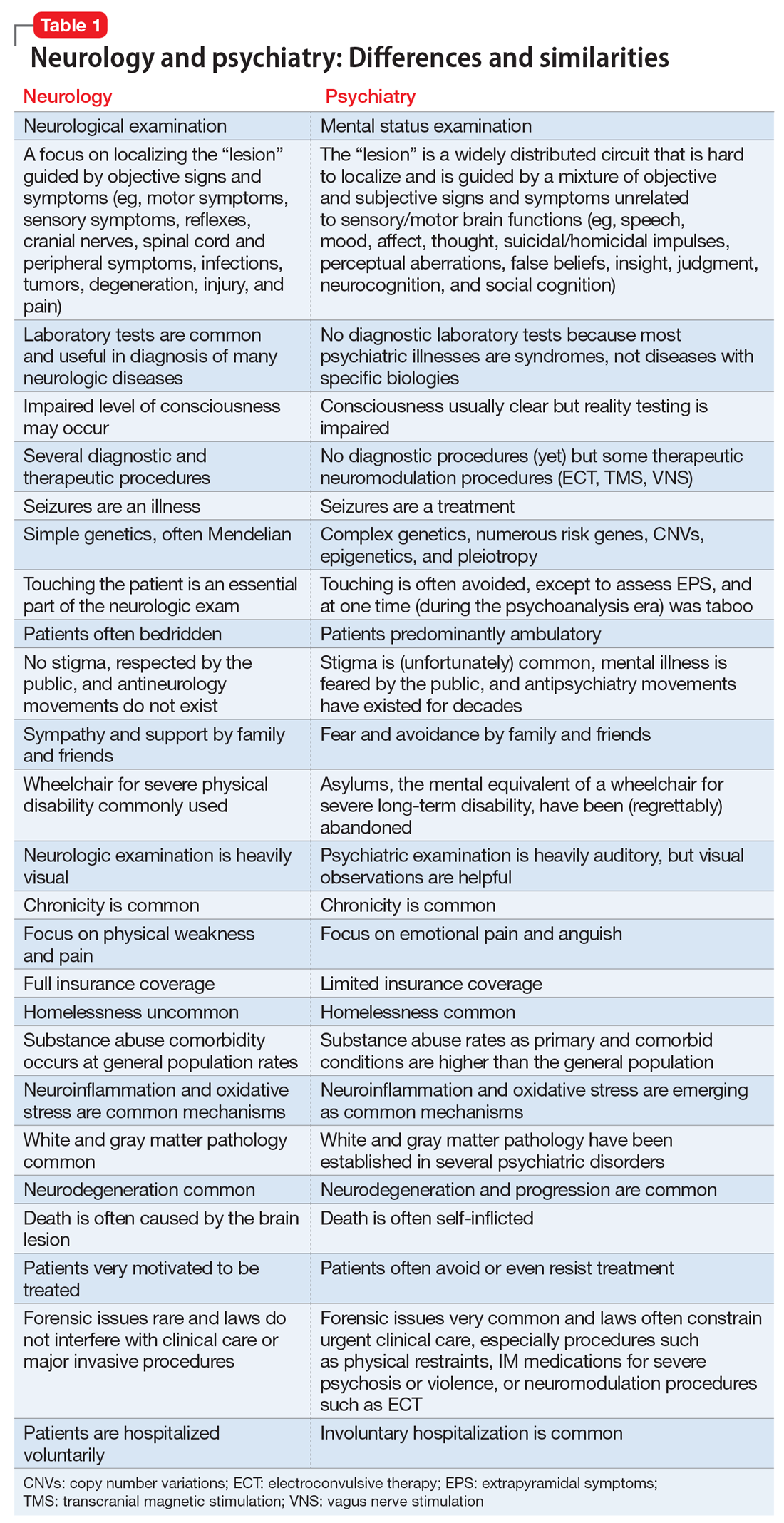

In Table 1, I compare and contrast the clinical approaches of these 2 sister clinical neuroscience specialties, beyond the shared standard medical templates of history of present illness, medical history, social history, family history, review of systems, and physical examination.

Despite those many differences in assessing and treating neurologic vs psychiatric disorders of the brain, there is an indisputable fact: Every neurologic disorder is associated with psychiatric manifestations, and every psychiatric illness is associated with neurologic symptoms. The brain is the most complex structure in the universe; its development requires the expression of 50% of the human genome, and its major task is to generate a mind that enables every human being to navigate the biopsychosocial imperatives of life. Any brain lesion, regardless of size and location, will disrupt the integrity of the mind in one way or another, such as speaking, thinking, fantasizing, arguing, understanding, feeling, remembering, plotting, enjoying, socializing, or courting. The bottom line is that every patient with a brain/mind disorder should ideally receive both neurologic and psychiatric evaluation, and the requisite dual interventions as necessary.1 If the focus is exclusively on either the brain or the mind, clinical and functional outcomes for the patient will be suboptimal.

Neuropsychiatrists and behavioral neurologists represent excellent bridges across these 2 sister specialties. There are twice as many psychiatrists as neurologists, but very few neuropsychiatrists or behavioral neurologists. The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) has approved several board certifications for both specialties, and several subspecialties as well (Table 2). When will the ABPN approve neuropsychiatry and behavioral neurology as subspecialties, to facilitate the integration of the brain and the mind,2 and to bridge the chasm between disorders of the brain and mind?

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Nasrallah HA. Toward the era of transformational neuropsychiatry. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;17:140-141.

2. Nasrallah HA. Reintegrating psychiatry and neurology is long overdue: Part 1. April 30, 2014. https://www.cmeinstitute.com/pages/lets-talk.aspx?bid=72. Accessed February 11, 2019.

Neurologists and psychiatrists diagnose and treat disorders of the brain’s hardware and software, respectively. The brain is a physically tangible structure, while its mind is virtual and intangible.

Not surprisingly, neurology and psychiatry have very different approaches to the assessment and treatment of brain and mind disorders. It reminds me of ophthalmology, where some of the faculty focus on the hardware of the eye (cornea, lens, and retina) while others focus on the major function of the eye—vision. Similarly, the mind is the major function of the brain.

Clinical neuroscience represents the shared foundational underpinnings of neurologists and psychiatrists, but their management of brain and mind disorders is understandably quite different, albeit with the same final goal: to repair and restore the structure and function of this divinely complex organ, the command and control center of the human soul and behavior.

In Table 1, I compare and contrast the clinical approaches of these 2 sister clinical neuroscience specialties, beyond the shared standard medical templates of history of present illness, medical history, social history, family history, review of systems, and physical examination.

Despite those many differences in assessing and treating neurologic vs psychiatric disorders of the brain, there is an indisputable fact: Every neurologic disorder is associated with psychiatric manifestations, and every psychiatric illness is associated with neurologic symptoms. The brain is the most complex structure in the universe; its development requires the expression of 50% of the human genome, and its major task is to generate a mind that enables every human being to navigate the biopsychosocial imperatives of life. Any brain lesion, regardless of size and location, will disrupt the integrity of the mind in one way or another, such as speaking, thinking, fantasizing, arguing, understanding, feeling, remembering, plotting, enjoying, socializing, or courting. The bottom line is that every patient with a brain/mind disorder should ideally receive both neurologic and psychiatric evaluation, and the requisite dual interventions as necessary.1 If the focus is exclusively on either the brain or the mind, clinical and functional outcomes for the patient will be suboptimal.

Neuropsychiatrists and behavioral neurologists represent excellent bridges across these 2 sister specialties. There are twice as many psychiatrists as neurologists, but very few neuropsychiatrists or behavioral neurologists. The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) has approved several board certifications for both specialties, and several subspecialties as well (Table 2). When will the ABPN approve neuropsychiatry and behavioral neurology as subspecialties, to facilitate the integration of the brain and the mind,2 and to bridge the chasm between disorders of the brain and mind?

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

Neurologists and psychiatrists diagnose and treat disorders of the brain’s hardware and software, respectively. The brain is a physically tangible structure, while its mind is virtual and intangible.

Not surprisingly, neurology and psychiatry have very different approaches to the assessment and treatment of brain and mind disorders. It reminds me of ophthalmology, where some of the faculty focus on the hardware of the eye (cornea, lens, and retina) while others focus on the major function of the eye—vision. Similarly, the mind is the major function of the brain.

Clinical neuroscience represents the shared foundational underpinnings of neurologists and psychiatrists, but their management of brain and mind disorders is understandably quite different, albeit with the same final goal: to repair and restore the structure and function of this divinely complex organ, the command and control center of the human soul and behavior.

In Table 1, I compare and contrast the clinical approaches of these 2 sister clinical neuroscience specialties, beyond the shared standard medical templates of history of present illness, medical history, social history, family history, review of systems, and physical examination.

Despite those many differences in assessing and treating neurologic vs psychiatric disorders of the brain, there is an indisputable fact: Every neurologic disorder is associated with psychiatric manifestations, and every psychiatric illness is associated with neurologic symptoms. The brain is the most complex structure in the universe; its development requires the expression of 50% of the human genome, and its major task is to generate a mind that enables every human being to navigate the biopsychosocial imperatives of life. Any brain lesion, regardless of size and location, will disrupt the integrity of the mind in one way or another, such as speaking, thinking, fantasizing, arguing, understanding, feeling, remembering, plotting, enjoying, socializing, or courting. The bottom line is that every patient with a brain/mind disorder should ideally receive both neurologic and psychiatric evaluation, and the requisite dual interventions as necessary.1 If the focus is exclusively on either the brain or the mind, clinical and functional outcomes for the patient will be suboptimal.

Neuropsychiatrists and behavioral neurologists represent excellent bridges across these 2 sister specialties. There are twice as many psychiatrists as neurologists, but very few neuropsychiatrists or behavioral neurologists. The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) has approved several board certifications for both specialties, and several subspecialties as well (Table 2). When will the ABPN approve neuropsychiatry and behavioral neurology as subspecialties, to facilitate the integration of the brain and the mind,2 and to bridge the chasm between disorders of the brain and mind?

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Nasrallah HA. Toward the era of transformational neuropsychiatry. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;17:140-141.

2. Nasrallah HA. Reintegrating psychiatry and neurology is long overdue: Part 1. April 30, 2014. https://www.cmeinstitute.com/pages/lets-talk.aspx?bid=72. Accessed February 11, 2019.

1. Nasrallah HA. Toward the era of transformational neuropsychiatry. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;17:140-141.

2. Nasrallah HA. Reintegrating psychiatry and neurology is long overdue: Part 1. April 30, 2014. https://www.cmeinstitute.com/pages/lets-talk.aspx?bid=72. Accessed February 11, 2019.

How do you feel about expectantly managing a well-dated pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation?

Most people know that preterm birth is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality. Consequently, strict guidelines have been enforced to prevent non–medically indicated scheduled deliveries before 39 weeks’ gestation. Fewer people recognize that late-term birth is also an important and avoidable contributor to perinatal morbidity. To improve pregnancy outcomes, we may need enhanced guidelines about minimizing expectant management of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.

For the fetus, what is the optimal duration of a healthy pregnancy?

When pregnancy progresses past the date of the confinement, the risk of fetal or newborn injury or death increases, especially after 41 weeks’ gestation. Analysis of this risk, day by day, suggests that after 40 weeks’ and 3 days’ gestation there is no medical benefit to the fetus to remain in utero because, compared with induced delivery, expectant management of the pregnancy is associated with a greater rate of fetal and newborn morbidity and mortality.1

The fetal and newborn benefits of delivery, rather than expectant management, at term include: a decrease in stillbirth and perinatal death rates, a decrease in admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), a decrease in meconium-stained amniotic fluid and meconium aspiration syndrome, a decrease in low Apgar scores, and a decrease in problems related to uteroplacental insufficiency, including oligohydramnios.2 In a comprehensive meta-analysis, induction of labor at or beyond term reduced the risk of perinatal death or stillbirth by 67%, the risk of a 5-minute Apgar score below 7 by 30%, and the risk of NICU admission by 12%.2 The number of women that would need to be induced to prevent 1 perinatal death was estimated to be 426.2

Maternal benefits of avoiding late-term pregnancy

The maternal benefits of avoiding continuing a pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation include a reduction in labor dystocia and the risk of cesarean delivery (CD).2,3 In one clinical trial, 3,407 women with low-risk pregnancy were randomly assigned to induction of labor at 41 weeks’ gestation or expectant management, awaiting the onset of labor with serial antenatal monitoring (nonstress tests and assessment of amniotic fluid volume).4 The CD rate was lower among the women randomized to induction of labor at 41 weeks’ (21.2% vs 24.5% in the expectant management group, P = .03). The rate of meconium-stained fluid was lower in the induction of labor group (25.0% vs 28.7%, P = .009). The rate of CD due to fetal distress also was lower in the induction of labor group (5.7% vs 8.3%, P = .003). The risks of maternal postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, and endometritis did not differ between the groups. There were 2 stillbirths in the expectant management group (2/1,706) and none in the induction of labor group (0/1,701). There were no neonatal deaths in this study.4

Obstetric management, including accurate dating of pregnancy and membrane sweeping at term, can help to reduce the risk that a pregnancy will progress beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.5

Continue to: Routinely use ultrasound to accurately establish gestational age

Routinely use ultrasound to accurately establish gestational age

First trimester ultrasound should be offered to all pregnant women because it is a more accurate assessment of gestational age and will result in fewer pregnancies that are thought to be at or beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.5 In a meta-analysis of 8 studies, including 25,516 women, early ultrasonography reduced the rate of intervention for postterm pregnancy by 42% (31/1,000 to 18/1,000 pregnant women).6

Membrane sweeping (or stripping)

Membrane sweeping, which causes the release of prostaglandins, has been reported to reduce the risk of late-term and postterm induction of labor.7,8 In the most recent Cochrane review on the topic, sweeping membranes reduced the rate of induction of labor at 41 weeks by 41% and at 42 weeks by 72%.7 To avoid one induction of labor for late-term or postterm pregnancy, sweeping of membranes would need to be performed on 8 women. In a recent meta-analysis, membrane sweeping reduced the rate of induction of labor for postmaturity by 48%.9

Membrane sweeping is associated with pain and an increased rate of vaginal bleeding.10 It does not increase the rate of maternal or neonatal infection, however. It also does not reduce the CD rate. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends that all clinicians have a discussion of membrane sweeping with their patients at 38 weeks’ gestation and offer membrane stripping at 40 weeks to increase the rate of timely spontaneous labor and to avoid the risks of prolonged pregnancy.11 Of note, in one randomized study of women planning a trial of labor after CD, membrane sweeping did not impact the duration of pregnancy, onset of spontaneous labor, or the CD rate.12

Steps from an expert. A skillfull midwife practicing in the United Kingdom provides the following guidance on how to perform membrane sweeping.13

- Prepare the patient. Explain the procedure, have the patient empty her bladder, and encourage relaxed breathing if the vaginal examination causes pain.

- Abdominal exam. Assess uterine size, fetal lie and presentation, and fetal heart tones.

- Vaginal exam. Ascertain cervical dilation, effacement, and position. If the cervix is closed a sweep may not be possible. In this case, massaging the vaginal fornices may help to release prostaglandins and stimulate uterine contractions. If the cervix is closed but soft, massage of the cervix may permit the insertion of a finger. If the cervix is favorable for sweeping, insert one finger in the cervix and rotate the finger in a circle to separate the amnion from the cervix.

- After the procedure. Provide the woman with a sanitary pad and recommend acetaminophen and a warm bath if she has discomfort or painful contractions. Advise her to come to the maternity unit in the following situations: severe pain, significant bleeding, or spontaneous rupture of the membranes.

Membrane sweeping can be performed as frequently as every 3 days. Formal cervical ripening and induction of labor may need to be planned if membrane sweeping does not result in the initiation of regular contractions.

Continue to: Collaborative decision making

Collaborative decision making

All clinicians recognize the primacy of patient autonomy.14 Competent patients have the right to select the course of care that they believe is optimal. When a patient decides to continue her pregnancy past 41 weeks, it is helpful to endorse respect for the decision and inquire about the patient’s reasons for continuing the pregnancy. Understanding the patient’s concerns may begin a conversation that will result in the patient accepting a plan for induction near 41 weeks’ gestation. If the patient insists on expectant management well beyond 41 weeks, the medical record should contain a summary of the clinician recommendation to induce labor at or before 41 weeks’ gestation and the patient’s preference for expectant management and her understanding of the decision’s risks.

Obstetricians and midwives constantly face the challenge of balancing the desire to avoid meddlesome interference in a pregnancy with the need to act to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes. The challenge is daunting. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the benefit of induction of labor at or beyond term, estimated that 426 inductions would need to be initiated to prevent one perinatal death.2 From one perspective it is meddlesome to intervene on more than 400 women to prevent one perinatal death. However, substantial data indicate that expectant management of a well-dated pregnancy at 41 weeks’ gestation will result in adverse outcomes that likely could be prevented by induction of labor. If you ran an airline and could take an action to prevent one airplane crash for every 400 flights, you would likely move heaven and earth to try to prevent that disaster. Unless the patient strongly prefers expectant management, well-managed induction of labor at or before 41 weeks’ gestation is likely to reduce the rate of adverse pregnancy events and, hence, is warranted.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Divon MY, Ferber A, Sanderson M, et al. A functional definition of prolonged pregnancy based on daily fetal and neonatal mortality rates. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:423-426.

- Middleton P, Shepherd E, Crowther CA. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD004945.

- Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labor versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:252-263.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hellmann J, et al; Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. Induction of labor as compared with serial antenatal monitoring in post-term pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1587-1592.

- Delaney M, Roggensack A. No. 214-Guidelines for the management of pregnancy at 41+0 to 42+0 weeks. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e164-e174.

- Whitworth M, Bricker L, Mullan C. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD007058.

- Boulvain M, Stan C, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD000451.

- Berghella V, Rogers RA, Lescale K. Stripping of membranes as a safe method to reduce prolonged pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:927-931.

- Avdiyovski H, Haith-Cooper M, Scally A. Membrane sweeping at term to promote spontaneous labour and reduce the likelihood of a formal induction of labour for postmaturity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018:1-9.

- de Miranda E, van der Bom JG, Bonsel G, et al. Membrane sweeping and prevention of post-term pregnancy in low-risk pregnancies: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:402-408.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health. NICE Guideline 70. Induction of labour; July 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg70/evidence/cg70-induction-of-labour-full-guideline2. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Hamdan M, Sidhu K, Sabir N, et al. Serial membrane sweeping at term in planned vaginal birth after cesarean: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:745-751.

- Gibbon K. How to perform a stretch and sweep. Midwives Magazine. 2012. https://www.rcm.org.uk/news-views-and-analysis/analysis/how-to%E2%80%A6-perform-a-stretch-and-sweep. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Ryan KJ. Erosion of the rights of pregnant women: in the interest of fetal well-being. Womens Health Issues. 1990;1:21-24.

Most people know that preterm birth is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality. Consequently, strict guidelines have been enforced to prevent non–medically indicated scheduled deliveries before 39 weeks’ gestation. Fewer people recognize that late-term birth is also an important and avoidable contributor to perinatal morbidity. To improve pregnancy outcomes, we may need enhanced guidelines about minimizing expectant management of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.

For the fetus, what is the optimal duration of a healthy pregnancy?

When pregnancy progresses past the date of the confinement, the risk of fetal or newborn injury or death increases, especially after 41 weeks’ gestation. Analysis of this risk, day by day, suggests that after 40 weeks’ and 3 days’ gestation there is no medical benefit to the fetus to remain in utero because, compared with induced delivery, expectant management of the pregnancy is associated with a greater rate of fetal and newborn morbidity and mortality.1

The fetal and newborn benefits of delivery, rather than expectant management, at term include: a decrease in stillbirth and perinatal death rates, a decrease in admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), a decrease in meconium-stained amniotic fluid and meconium aspiration syndrome, a decrease in low Apgar scores, and a decrease in problems related to uteroplacental insufficiency, including oligohydramnios.2 In a comprehensive meta-analysis, induction of labor at or beyond term reduced the risk of perinatal death or stillbirth by 67%, the risk of a 5-minute Apgar score below 7 by 30%, and the risk of NICU admission by 12%.2 The number of women that would need to be induced to prevent 1 perinatal death was estimated to be 426.2

Maternal benefits of avoiding late-term pregnancy

The maternal benefits of avoiding continuing a pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation include a reduction in labor dystocia and the risk of cesarean delivery (CD).2,3 In one clinical trial, 3,407 women with low-risk pregnancy were randomly assigned to induction of labor at 41 weeks’ gestation or expectant management, awaiting the onset of labor with serial antenatal monitoring (nonstress tests and assessment of amniotic fluid volume).4 The CD rate was lower among the women randomized to induction of labor at 41 weeks’ (21.2% vs 24.5% in the expectant management group, P = .03). The rate of meconium-stained fluid was lower in the induction of labor group (25.0% vs 28.7%, P = .009). The rate of CD due to fetal distress also was lower in the induction of labor group (5.7% vs 8.3%, P = .003). The risks of maternal postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, and endometritis did not differ between the groups. There were 2 stillbirths in the expectant management group (2/1,706) and none in the induction of labor group (0/1,701). There were no neonatal deaths in this study.4

Obstetric management, including accurate dating of pregnancy and membrane sweeping at term, can help to reduce the risk that a pregnancy will progress beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.5

Continue to: Routinely use ultrasound to accurately establish gestational age

Routinely use ultrasound to accurately establish gestational age

First trimester ultrasound should be offered to all pregnant women because it is a more accurate assessment of gestational age and will result in fewer pregnancies that are thought to be at or beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.5 In a meta-analysis of 8 studies, including 25,516 women, early ultrasonography reduced the rate of intervention for postterm pregnancy by 42% (31/1,000 to 18/1,000 pregnant women).6

Membrane sweeping (or stripping)

Membrane sweeping, which causes the release of prostaglandins, has been reported to reduce the risk of late-term and postterm induction of labor.7,8 In the most recent Cochrane review on the topic, sweeping membranes reduced the rate of induction of labor at 41 weeks by 41% and at 42 weeks by 72%.7 To avoid one induction of labor for late-term or postterm pregnancy, sweeping of membranes would need to be performed on 8 women. In a recent meta-analysis, membrane sweeping reduced the rate of induction of labor for postmaturity by 48%.9

Membrane sweeping is associated with pain and an increased rate of vaginal bleeding.10 It does not increase the rate of maternal or neonatal infection, however. It also does not reduce the CD rate. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends that all clinicians have a discussion of membrane sweeping with their patients at 38 weeks’ gestation and offer membrane stripping at 40 weeks to increase the rate of timely spontaneous labor and to avoid the risks of prolonged pregnancy.11 Of note, in one randomized study of women planning a trial of labor after CD, membrane sweeping did not impact the duration of pregnancy, onset of spontaneous labor, or the CD rate.12

Steps from an expert. A skillfull midwife practicing in the United Kingdom provides the following guidance on how to perform membrane sweeping.13

- Prepare the patient. Explain the procedure, have the patient empty her bladder, and encourage relaxed breathing if the vaginal examination causes pain.

- Abdominal exam. Assess uterine size, fetal lie and presentation, and fetal heart tones.

- Vaginal exam. Ascertain cervical dilation, effacement, and position. If the cervix is closed a sweep may not be possible. In this case, massaging the vaginal fornices may help to release prostaglandins and stimulate uterine contractions. If the cervix is closed but soft, massage of the cervix may permit the insertion of a finger. If the cervix is favorable for sweeping, insert one finger in the cervix and rotate the finger in a circle to separate the amnion from the cervix.

- After the procedure. Provide the woman with a sanitary pad and recommend acetaminophen and a warm bath if she has discomfort or painful contractions. Advise her to come to the maternity unit in the following situations: severe pain, significant bleeding, or spontaneous rupture of the membranes.

Membrane sweeping can be performed as frequently as every 3 days. Formal cervical ripening and induction of labor may need to be planned if membrane sweeping does not result in the initiation of regular contractions.

Continue to: Collaborative decision making

Collaborative decision making

All clinicians recognize the primacy of patient autonomy.14 Competent patients have the right to select the course of care that they believe is optimal. When a patient decides to continue her pregnancy past 41 weeks, it is helpful to endorse respect for the decision and inquire about the patient’s reasons for continuing the pregnancy. Understanding the patient’s concerns may begin a conversation that will result in the patient accepting a plan for induction near 41 weeks’ gestation. If the patient insists on expectant management well beyond 41 weeks, the medical record should contain a summary of the clinician recommendation to induce labor at or before 41 weeks’ gestation and the patient’s preference for expectant management and her understanding of the decision’s risks.

Obstetricians and midwives constantly face the challenge of balancing the desire to avoid meddlesome interference in a pregnancy with the need to act to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes. The challenge is daunting. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the benefit of induction of labor at or beyond term, estimated that 426 inductions would need to be initiated to prevent one perinatal death.2 From one perspective it is meddlesome to intervene on more than 400 women to prevent one perinatal death. However, substantial data indicate that expectant management of a well-dated pregnancy at 41 weeks’ gestation will result in adverse outcomes that likely could be prevented by induction of labor. If you ran an airline and could take an action to prevent one airplane crash for every 400 flights, you would likely move heaven and earth to try to prevent that disaster. Unless the patient strongly prefers expectant management, well-managed induction of labor at or before 41 weeks’ gestation is likely to reduce the rate of adverse pregnancy events and, hence, is warranted.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Most people know that preterm birth is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality. Consequently, strict guidelines have been enforced to prevent non–medically indicated scheduled deliveries before 39 weeks’ gestation. Fewer people recognize that late-term birth is also an important and avoidable contributor to perinatal morbidity. To improve pregnancy outcomes, we may need enhanced guidelines about minimizing expectant management of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.

For the fetus, what is the optimal duration of a healthy pregnancy?

When pregnancy progresses past the date of the confinement, the risk of fetal or newborn injury or death increases, especially after 41 weeks’ gestation. Analysis of this risk, day by day, suggests that after 40 weeks’ and 3 days’ gestation there is no medical benefit to the fetus to remain in utero because, compared with induced delivery, expectant management of the pregnancy is associated with a greater rate of fetal and newborn morbidity and mortality.1

The fetal and newborn benefits of delivery, rather than expectant management, at term include: a decrease in stillbirth and perinatal death rates, a decrease in admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), a decrease in meconium-stained amniotic fluid and meconium aspiration syndrome, a decrease in low Apgar scores, and a decrease in problems related to uteroplacental insufficiency, including oligohydramnios.2 In a comprehensive meta-analysis, induction of labor at or beyond term reduced the risk of perinatal death or stillbirth by 67%, the risk of a 5-minute Apgar score below 7 by 30%, and the risk of NICU admission by 12%.2 The number of women that would need to be induced to prevent 1 perinatal death was estimated to be 426.2

Maternal benefits of avoiding late-term pregnancy

The maternal benefits of avoiding continuing a pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation include a reduction in labor dystocia and the risk of cesarean delivery (CD).2,3 In one clinical trial, 3,407 women with low-risk pregnancy were randomly assigned to induction of labor at 41 weeks’ gestation or expectant management, awaiting the onset of labor with serial antenatal monitoring (nonstress tests and assessment of amniotic fluid volume).4 The CD rate was lower among the women randomized to induction of labor at 41 weeks’ (21.2% vs 24.5% in the expectant management group, P = .03). The rate of meconium-stained fluid was lower in the induction of labor group (25.0% vs 28.7%, P = .009). The rate of CD due to fetal distress also was lower in the induction of labor group (5.7% vs 8.3%, P = .003). The risks of maternal postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, and endometritis did not differ between the groups. There were 2 stillbirths in the expectant management group (2/1,706) and none in the induction of labor group (0/1,701). There were no neonatal deaths in this study.4

Obstetric management, including accurate dating of pregnancy and membrane sweeping at term, can help to reduce the risk that a pregnancy will progress beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.5

Continue to: Routinely use ultrasound to accurately establish gestational age

Routinely use ultrasound to accurately establish gestational age

First trimester ultrasound should be offered to all pregnant women because it is a more accurate assessment of gestational age and will result in fewer pregnancies that are thought to be at or beyond 41 weeks’ gestation.5 In a meta-analysis of 8 studies, including 25,516 women, early ultrasonography reduced the rate of intervention for postterm pregnancy by 42% (31/1,000 to 18/1,000 pregnant women).6

Membrane sweeping (or stripping)

Membrane sweeping, which causes the release of prostaglandins, has been reported to reduce the risk of late-term and postterm induction of labor.7,8 In the most recent Cochrane review on the topic, sweeping membranes reduced the rate of induction of labor at 41 weeks by 41% and at 42 weeks by 72%.7 To avoid one induction of labor for late-term or postterm pregnancy, sweeping of membranes would need to be performed on 8 women. In a recent meta-analysis, membrane sweeping reduced the rate of induction of labor for postmaturity by 48%.9

Membrane sweeping is associated with pain and an increased rate of vaginal bleeding.10 It does not increase the rate of maternal or neonatal infection, however. It also does not reduce the CD rate. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends that all clinicians have a discussion of membrane sweeping with their patients at 38 weeks’ gestation and offer membrane stripping at 40 weeks to increase the rate of timely spontaneous labor and to avoid the risks of prolonged pregnancy.11 Of note, in one randomized study of women planning a trial of labor after CD, membrane sweeping did not impact the duration of pregnancy, onset of spontaneous labor, or the CD rate.12

Steps from an expert. A skillfull midwife practicing in the United Kingdom provides the following guidance on how to perform membrane sweeping.13

- Prepare the patient. Explain the procedure, have the patient empty her bladder, and encourage relaxed breathing if the vaginal examination causes pain.

- Abdominal exam. Assess uterine size, fetal lie and presentation, and fetal heart tones.

- Vaginal exam. Ascertain cervical dilation, effacement, and position. If the cervix is closed a sweep may not be possible. In this case, massaging the vaginal fornices may help to release prostaglandins and stimulate uterine contractions. If the cervix is closed but soft, massage of the cervix may permit the insertion of a finger. If the cervix is favorable for sweeping, insert one finger in the cervix and rotate the finger in a circle to separate the amnion from the cervix.

- After the procedure. Provide the woman with a sanitary pad and recommend acetaminophen and a warm bath if she has discomfort or painful contractions. Advise her to come to the maternity unit in the following situations: severe pain, significant bleeding, or spontaneous rupture of the membranes.

Membrane sweeping can be performed as frequently as every 3 days. Formal cervical ripening and induction of labor may need to be planned if membrane sweeping does not result in the initiation of regular contractions.

Continue to: Collaborative decision making

Collaborative decision making

All clinicians recognize the primacy of patient autonomy.14 Competent patients have the right to select the course of care that they believe is optimal. When a patient decides to continue her pregnancy past 41 weeks, it is helpful to endorse respect for the decision and inquire about the patient’s reasons for continuing the pregnancy. Understanding the patient’s concerns may begin a conversation that will result in the patient accepting a plan for induction near 41 weeks’ gestation. If the patient insists on expectant management well beyond 41 weeks, the medical record should contain a summary of the clinician recommendation to induce labor at or before 41 weeks’ gestation and the patient’s preference for expectant management and her understanding of the decision’s risks.

Obstetricians and midwives constantly face the challenge of balancing the desire to avoid meddlesome interference in a pregnancy with the need to act to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes. The challenge is daunting. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the benefit of induction of labor at or beyond term, estimated that 426 inductions would need to be initiated to prevent one perinatal death.2 From one perspective it is meddlesome to intervene on more than 400 women to prevent one perinatal death. However, substantial data indicate that expectant management of a well-dated pregnancy at 41 weeks’ gestation will result in adverse outcomes that likely could be prevented by induction of labor. If you ran an airline and could take an action to prevent one airplane crash for every 400 flights, you would likely move heaven and earth to try to prevent that disaster. Unless the patient strongly prefers expectant management, well-managed induction of labor at or before 41 weeks’ gestation is likely to reduce the rate of adverse pregnancy events and, hence, is warranted.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Divon MY, Ferber A, Sanderson M, et al. A functional definition of prolonged pregnancy based on daily fetal and neonatal mortality rates. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:423-426.

- Middleton P, Shepherd E, Crowther CA. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD004945.

- Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labor versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:252-263.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hellmann J, et al; Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. Induction of labor as compared with serial antenatal monitoring in post-term pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1587-1592.

- Delaney M, Roggensack A. No. 214-Guidelines for the management of pregnancy at 41+0 to 42+0 weeks. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e164-e174.

- Whitworth M, Bricker L, Mullan C. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD007058.

- Boulvain M, Stan C, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD000451.

- Berghella V, Rogers RA, Lescale K. Stripping of membranes as a safe method to reduce prolonged pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:927-931.

- Avdiyovski H, Haith-Cooper M, Scally A. Membrane sweeping at term to promote spontaneous labour and reduce the likelihood of a formal induction of labour for postmaturity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018:1-9.

- de Miranda E, van der Bom JG, Bonsel G, et al. Membrane sweeping and prevention of post-term pregnancy in low-risk pregnancies: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:402-408.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health. NICE Guideline 70. Induction of labour; July 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg70/evidence/cg70-induction-of-labour-full-guideline2. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Hamdan M, Sidhu K, Sabir N, et al. Serial membrane sweeping at term in planned vaginal birth after cesarean: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:745-751.

- Gibbon K. How to perform a stretch and sweep. Midwives Magazine. 2012. https://www.rcm.org.uk/news-views-and-analysis/analysis/how-to%E2%80%A6-perform-a-stretch-and-sweep. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Ryan KJ. Erosion of the rights of pregnant women: in the interest of fetal well-being. Womens Health Issues. 1990;1:21-24.

- Divon MY, Ferber A, Sanderson M, et al. A functional definition of prolonged pregnancy based on daily fetal and neonatal mortality rates. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:423-426.

- Middleton P, Shepherd E, Crowther CA. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD004945.

- Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labor versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:252-263.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hellmann J, et al; Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. Induction of labor as compared with serial antenatal monitoring in post-term pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1587-1592.

- Delaney M, Roggensack A. No. 214-Guidelines for the management of pregnancy at 41+0 to 42+0 weeks. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e164-e174.

- Whitworth M, Bricker L, Mullan C. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD007058.

- Boulvain M, Stan C, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD000451.

- Berghella V, Rogers RA, Lescale K. Stripping of membranes as a safe method to reduce prolonged pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:927-931.

- Avdiyovski H, Haith-Cooper M, Scally A. Membrane sweeping at term to promote spontaneous labour and reduce the likelihood of a formal induction of labour for postmaturity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018:1-9.

- de Miranda E, van der Bom JG, Bonsel G, et al. Membrane sweeping and prevention of post-term pregnancy in low-risk pregnancies: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:402-408.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health. NICE Guideline 70. Induction of labour; July 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg70/evidence/cg70-induction-of-labour-full-guideline2. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Hamdan M, Sidhu K, Sabir N, et al. Serial membrane sweeping at term in planned vaginal birth after cesarean: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:745-751.

- Gibbon K. How to perform a stretch and sweep. Midwives Magazine. 2012. https://www.rcm.org.uk/news-views-and-analysis/analysis/how-to%E2%80%A6-perform-a-stretch-and-sweep. Accessed January 23, 2019.

- Ryan KJ. Erosion of the rights of pregnant women: in the interest of fetal well-being. Womens Health Issues. 1990;1:21-24.

There is more to the TSH than a number

At a quick read, the messages from these articles may seem contradictory. But the biology is more complex in the setting of endogenous production of T4 by the thyroid gland, which is regulated by TSH, which in turn is regulated in a feedback loop by the thyroid-produced T4. In the setting of a fixed replacement dose of exogenous levothyroxine, the provided hormone affects the pituitary production of TSH, which likely will have no significant subsequent effect on the T4 level. Thus, the feedback control loop is far simpler.

There has not been a definitive study demonstrating that thyroxine supplementation in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism results in a superior clinical outcome. There are hints that this may be the case, and Azim and Nasr cite some of these studies. Recognizing a few markedly different physiologic reasons why the TSH can be slightly elevated and the T4 normal helps explain the lack of uniform clinical success with supplementation therapy and provides rationales for some management strategies.

Any biological variability in the responsiveness of the thyroid gland to TSH may affect the relationship between the levels of TSH and thyroid gland-released T4. In theory, if the thyroid receptor has decreased affinity for TSH, a higher TSH concentration will be needed to get the thyroid gland to secrete the level of T4 that the pituitary sensing mechanism deems normal for that individual. If the receptor affinity was decreased due to a gene polymorphism, this relationship between TSH and T4 may be stable, and providing exogenous T4 will result in a lower, “normalized” TSH level but may disrupt the thyroid-pituitary crosstalk and may even produce clinical hyperthyroidism.

A similar scenario exists in the setting of early thyroid gland failure, such as in Hashimoto thyroiditis. But in the latter scenario, the TSH-to-T4 production relationship may be unstable over time, for as additional thyroid gland is destroyed, T4 production will continue to decrease, the TSH will increase, and the thyroid gland may ultimately fail and hypothyroidism will occur. Hence the recommendation that in the setting of subclinical hypothyroidism and antiperoxidase antibodies, T4 and TSH levels should be monitored regularly in order to detect early true thyroid gland failure when the T4 level can no longer be maintained despite the increased stimulation of the gland by the elevated TSH. Analogous to this may be subclinical hypothyroidism in the elderly, in whom thyroid gland failure may develop, despite an increased TSH, from senescence rather than autoimmunity. What I am suggesting is that the natural history of all patients with subclinical hypothyroidism is not alike, and it thus should not be surprising that there does not seem to be a one-size-fits-all approach to management.

Symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have not uniformly improved with T4 treatment compared with placebo. Notably, most patients with subclinical hypothyroidism experience no symptoms. But consider the extremely common symptom of fatigue, which can be present for a myriad of defined and undefined reasons. This symptom may often lead physicians to check the TSH and, if that is even slightly elevated, to also check the T4. It may also lead some physicians to routinely check the T4. Subclinical hypothyroidism is also quite common; thus, by chance alone or because of the circadian timing of checking the TSH, a slightly elevated TSH and fatigue may coexist and yet be unrelated.

Additionally, a positive biochemical response to thyroxine supplementation, such as a lowering of cholesterol, does not prove that the patient was clinically hypothyroid prior to supplementation, any more than lowering a patient’s blood glucose with insulin proves that the patient was diabetic. The management of subclinical hypothyroidism should be nuanced and based on both clinical and laboratory parameters.

- Nasr C. Is a serum TSH measurement sufficient to monitor the treatment of primary hypothyroidism? Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(8):571–573. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15165

- Mandell BF. Trust the thyroid thermostat. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(8):552–553. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83b.08016

At a quick read, the messages from these articles may seem contradictory. But the biology is more complex in the setting of endogenous production of T4 by the thyroid gland, which is regulated by TSH, which in turn is regulated in a feedback loop by the thyroid-produced T4. In the setting of a fixed replacement dose of exogenous levothyroxine, the provided hormone affects the pituitary production of TSH, which likely will have no significant subsequent effect on the T4 level. Thus, the feedback control loop is far simpler.

There has not been a definitive study demonstrating that thyroxine supplementation in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism results in a superior clinical outcome. There are hints that this may be the case, and Azim and Nasr cite some of these studies. Recognizing a few markedly different physiologic reasons why the TSH can be slightly elevated and the T4 normal helps explain the lack of uniform clinical success with supplementation therapy and provides rationales for some management strategies.

Any biological variability in the responsiveness of the thyroid gland to TSH may affect the relationship between the levels of TSH and thyroid gland-released T4. In theory, if the thyroid receptor has decreased affinity for TSH, a higher TSH concentration will be needed to get the thyroid gland to secrete the level of T4 that the pituitary sensing mechanism deems normal for that individual. If the receptor affinity was decreased due to a gene polymorphism, this relationship between TSH and T4 may be stable, and providing exogenous T4 will result in a lower, “normalized” TSH level but may disrupt the thyroid-pituitary crosstalk and may even produce clinical hyperthyroidism.

A similar scenario exists in the setting of early thyroid gland failure, such as in Hashimoto thyroiditis. But in the latter scenario, the TSH-to-T4 production relationship may be unstable over time, for as additional thyroid gland is destroyed, T4 production will continue to decrease, the TSH will increase, and the thyroid gland may ultimately fail and hypothyroidism will occur. Hence the recommendation that in the setting of subclinical hypothyroidism and antiperoxidase antibodies, T4 and TSH levels should be monitored regularly in order to detect early true thyroid gland failure when the T4 level can no longer be maintained despite the increased stimulation of the gland by the elevated TSH. Analogous to this may be subclinical hypothyroidism in the elderly, in whom thyroid gland failure may develop, despite an increased TSH, from senescence rather than autoimmunity. What I am suggesting is that the natural history of all patients with subclinical hypothyroidism is not alike, and it thus should not be surprising that there does not seem to be a one-size-fits-all approach to management.

Symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have not uniformly improved with T4 treatment compared with placebo. Notably, most patients with subclinical hypothyroidism experience no symptoms. But consider the extremely common symptom of fatigue, which can be present for a myriad of defined and undefined reasons. This symptom may often lead physicians to check the TSH and, if that is even slightly elevated, to also check the T4. It may also lead some physicians to routinely check the T4. Subclinical hypothyroidism is also quite common; thus, by chance alone or because of the circadian timing of checking the TSH, a slightly elevated TSH and fatigue may coexist and yet be unrelated.

Additionally, a positive biochemical response to thyroxine supplementation, such as a lowering of cholesterol, does not prove that the patient was clinically hypothyroid prior to supplementation, any more than lowering a patient’s blood glucose with insulin proves that the patient was diabetic. The management of subclinical hypothyroidism should be nuanced and based on both clinical and laboratory parameters.

At a quick read, the messages from these articles may seem contradictory. But the biology is more complex in the setting of endogenous production of T4 by the thyroid gland, which is regulated by TSH, which in turn is regulated in a feedback loop by the thyroid-produced T4. In the setting of a fixed replacement dose of exogenous levothyroxine, the provided hormone affects the pituitary production of TSH, which likely will have no significant subsequent effect on the T4 level. Thus, the feedback control loop is far simpler.

There has not been a definitive study demonstrating that thyroxine supplementation in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism results in a superior clinical outcome. There are hints that this may be the case, and Azim and Nasr cite some of these studies. Recognizing a few markedly different physiologic reasons why the TSH can be slightly elevated and the T4 normal helps explain the lack of uniform clinical success with supplementation therapy and provides rationales for some management strategies.

Any biological variability in the responsiveness of the thyroid gland to TSH may affect the relationship between the levels of TSH and thyroid gland-released T4. In theory, if the thyroid receptor has decreased affinity for TSH, a higher TSH concentration will be needed to get the thyroid gland to secrete the level of T4 that the pituitary sensing mechanism deems normal for that individual. If the receptor affinity was decreased due to a gene polymorphism, this relationship between TSH and T4 may be stable, and providing exogenous T4 will result in a lower, “normalized” TSH level but may disrupt the thyroid-pituitary crosstalk and may even produce clinical hyperthyroidism.

A similar scenario exists in the setting of early thyroid gland failure, such as in Hashimoto thyroiditis. But in the latter scenario, the TSH-to-T4 production relationship may be unstable over time, for as additional thyroid gland is destroyed, T4 production will continue to decrease, the TSH will increase, and the thyroid gland may ultimately fail and hypothyroidism will occur. Hence the recommendation that in the setting of subclinical hypothyroidism and antiperoxidase antibodies, T4 and TSH levels should be monitored regularly in order to detect early true thyroid gland failure when the T4 level can no longer be maintained despite the increased stimulation of the gland by the elevated TSH. Analogous to this may be subclinical hypothyroidism in the elderly, in whom thyroid gland failure may develop, despite an increased TSH, from senescence rather than autoimmunity. What I am suggesting is that the natural history of all patients with subclinical hypothyroidism is not alike, and it thus should not be surprising that there does not seem to be a one-size-fits-all approach to management.

Symptoms in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have not uniformly improved with T4 treatment compared with placebo. Notably, most patients with subclinical hypothyroidism experience no symptoms. But consider the extremely common symptom of fatigue, which can be present for a myriad of defined and undefined reasons. This symptom may often lead physicians to check the TSH and, if that is even slightly elevated, to also check the T4. It may also lead some physicians to routinely check the T4. Subclinical hypothyroidism is also quite common; thus, by chance alone or because of the circadian timing of checking the TSH, a slightly elevated TSH and fatigue may coexist and yet be unrelated.

Additionally, a positive biochemical response to thyroxine supplementation, such as a lowering of cholesterol, does not prove that the patient was clinically hypothyroid prior to supplementation, any more than lowering a patient’s blood glucose with insulin proves that the patient was diabetic. The management of subclinical hypothyroidism should be nuanced and based on both clinical and laboratory parameters.

- Nasr C. Is a serum TSH measurement sufficient to monitor the treatment of primary hypothyroidism? Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(8):571–573. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15165

- Mandell BF. Trust the thyroid thermostat. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(8):552–553. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83b.08016

- Nasr C. Is a serum TSH measurement sufficient to monitor the treatment of primary hypothyroidism? Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(8):571–573. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15165

- Mandell BF. Trust the thyroid thermostat. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83(8):552–553. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83b.08016

Psychiatry’s social impact: Pervasive and multifaceted

Psychiatry has an enormous swath of effects on the social structure of society, perhaps more than any other medical specialty. Its ramifications can be observed and experienced across medical, scientific, legal, financial, political, sexual, religious, cultural, sociological, and artistic aspects of the aggregate of humans living together that we call society.

And yet, despite its pervasive and significant consequences at multiple levels of human communities, psychiatry remains inadequately appreciated or understood. In fact, it is sometimes maligned in a manner that no other medical discipline ever has to face.

I will expound on what may sound like a sweeping statement, and let you decide if society is indeed influenced in myriad ways by the wide array of psychiatric brain disorders that impact various core components of society.

Consider the following major societal repercussions of psychiatric disorders:

- Twenty-five percent of the population suffers from a psychiatric disorder per the landmark Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study,1,2 funded by the National Institutes of Health. This translates to 85 million children, adolescents, adults, and older adults. No other medical specialty comes close to affecting this massive number of individuals in society.

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 4 of the top 10 causes of disability across all medical conditions are psychiatric disorders (Table3). Depression, alcoholism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder account for the greatest proportion of individuals with disabilities. Obviously, the impact of psychiatry in society is more significant than any other medical specialty as far as functional disability is concerned.

- The jails and prisons of the country are brimming with psychiatric patients who are arrested, incarcerated, and criminalized because their brain disorder disrupts their behavior. This is one of the most serious (and frankly outrageous) legal problems in our society. It occurred after our society decided to shutter state-supported hospitals (asylums) where psychiatric patients used to be treated as medically ill persons by health care professionals such as physicians, nurses, psychologists, and social workers, not prison guards. Remember that in the 1960s, 50% of all hospital beds in the United States were occupied by psychiatric patients, which is another historical indication of the societal impact of psychiatry.

- Alcohol and drug abuse are undoubtedly one of society’s most intractable problems. They are not only psychiatric disorders, but are often associated with multiple other psychiatric comorbidities and can lead to a host of general medical and surgical consequences. They are not only costly in financial terms, but they also lead to an increase in crime and forensic problems. Premature death is a heavy toll for society due to alcohol and substance use, as the opioid epidemic clearly has demonstrated over the past few years.

- Homelessness is an endemic sociological cancer in the body of society and is very often driven by psychiatric disorders and addictions. Countless numbers of severely mentally ill patients became homeless when asylums were closed and they were “freed” from restrictive institutional settings. Homelessness and imprisonment became the heavy and shameful price of “freedom” for persons with disabling psychiatric disorders in our “advanced” society.

- Suicide, both completed and attempted, is intimately associated with psychiatric disorders. Approximately 47,000 deaths from suicide were reported in the United States in 2017.4 Given that more than 30 million Americans suffer from mood disorders, millions of suicide attempts take place, crowding the emergency rooms of the country with individuals who need to receive emergent health care. The tragic toll of suicide and the heavy medical care costs of suicide attempts are incalculable, and unfortunately have been growing steadily over the past 20 years.

- Homicide is sometimes committed by persons with a psychiatric disorder, most commonly antisocial personality disorder. The rate of homicide often is used as a measure of a city’s quality of life, and urban areas where access to psychiatric care is limited tend to have high homicide rates.

- School problems, whether due to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, below-average intellectual abilities, conduct disorder, bullying, impulsive behavior, substance use, broken homes, or dysfunctional families (often due to addictive or psychiatric disorders), are a major societal problem. Whether the problem is truancy, school fights, or dropping out before getting a high school diploma, psychiatric illness is frequently the underlying reason.

- Sexual controversies, such as expanding and evolving gender identity issues and discrimination against non-cisgender individuals, have instigated both positive and negative initiatives in society. Sexual abuse of children and its grave psychiatric implications in adulthood continues to happen despite public outrage and law enforcement efforts, and is often driven by individuals with serious psychopathology. In addition, sexual addiction (and its many biopsychosocial complications) is often associated with neuropsychiatric disorders.

- Poverty and the perpetual underclass are often a result of psychiatric disorders, and represent an ongoing societal challenge that has proven impossible to fix just by throwing money at it. Whether the affected individuals are seriously mentally ill, addicted, cognitively impaired or challenged, or unmotivated because of a neuropsychiatric disorder, poverty is practically impossible to eliminate.

- One positive impact of psychiatry in society is that artistic abilities, writing talent, musical creativity, entrepreneurship, and high productivity are often associated with certain psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar disorder, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and psychosis spectrum disorders. Society is enriched by the creative energy and out-of-the-box thinking of persons with mild to moderate neuropsychiatric disorders.

- The financial impact of psychiatry is massive. The direct and indirect costs of psychiatric and addictive disorders are estimated to be more than $400 billion/year. Even a single serious psychiatric disorder, such as schizophrenia, costs society approximately $70 billion/year. The same holds true for bipolar disorder and depression. Thus, psychiatry accounts for a substantial portion of the financial expenditures in society.

- And last but certainly not least are the impediments to psychiatric treatment for tens of millions of individuals in our society who need treatment the most: the lack of health insurance parity; the stigma of seeking psychiatric help; the serious shortage of psychiatrists, especially in inner-city areas and rural regions; the poor public understanding about psychiatric illness; and the fact that the success rate of psychiatric treatment is very similar to (and sometimes better than) that of serious cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal diseases. There are also many flawed religious, cultural, or philosophical belief systems that fail to accept that the mind is a product of brain biology and function and that psychiatric disorders are brain disorders that affect thought, mood impulses, cognition, and behavior, just as other brain disorders cause muscle weakness, epileptic seizures, or stroke. The public must understand that depression can be caused by stroke or multiple sclerosis, that Parkinson’s disease can cause hallucinations and delusions, and that brain tumors can cause personality changes.

Continue to: So, what should society do to address...

So, what should society do to address the multiple impacts of psychiatry on its structure and function? I have a brief answer: intensive research. If society would embark on a massive research effort to discover preventions and cures for psychiatric disorders, the return on investment would be tremendous in human and financial terms. Currently, only a miniscule amount of money (<0.5% of the annual cost of psychiatric disorders) is invested in psychiatric brain research. Society should embark on a BHAG (pronounced Bee Hag), an acronym for “Big Hairy Audacious Goal,” a term coined by Jim Collins and Jerry Poras, who authored the seminal book Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. The BHAG is an ambitious and visionary goal that steers a company (or in this case, society) to a much brighter future. It would be on the scale of the Manhattan Project in the 1940s, which developed the nuclear bomb that put an end to World War II. When it comes to psychiatry, society should do no less.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Regier DA, Myers JK, Kramer M, et al. The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area program. Historical context, major objectives, and study population characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(10):934-941.

2. Robins LN, Regier DA (eds). Psychiatric disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1992.

3. World Health Organization. Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2000 estimates. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_regional_2000/en/. Accessed January 17, 2019.

4. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicide statistics. https://afsp.org/about-suicide/suicide-statistics. Accessed January 18, 2019.

Psychiatry has an enormous swath of effects on the social structure of society, perhaps more than any other medical specialty. Its ramifications can be observed and experienced across medical, scientific, legal, financial, political, sexual, religious, cultural, sociological, and artistic aspects of the aggregate of humans living together that we call society.

And yet, despite its pervasive and significant consequences at multiple levels of human communities, psychiatry remains inadequately appreciated or understood. In fact, it is sometimes maligned in a manner that no other medical discipline ever has to face.

I will expound on what may sound like a sweeping statement, and let you decide if society is indeed influenced in myriad ways by the wide array of psychiatric brain disorders that impact various core components of society.

Consider the following major societal repercussions of psychiatric disorders:

- Twenty-five percent of the population suffers from a psychiatric disorder per the landmark Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study,1,2 funded by the National Institutes of Health. This translates to 85 million children, adolescents, adults, and older adults. No other medical specialty comes close to affecting this massive number of individuals in society.

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 4 of the top 10 causes of disability across all medical conditions are psychiatric disorders (Table3). Depression, alcoholism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder account for the greatest proportion of individuals with disabilities. Obviously, the impact of psychiatry in society is more significant than any other medical specialty as far as functional disability is concerned.

- The jails and prisons of the country are brimming with psychiatric patients who are arrested, incarcerated, and criminalized because their brain disorder disrupts their behavior. This is one of the most serious (and frankly outrageous) legal problems in our society. It occurred after our society decided to shutter state-supported hospitals (asylums) where psychiatric patients used to be treated as medically ill persons by health care professionals such as physicians, nurses, psychologists, and social workers, not prison guards. Remember that in the 1960s, 50% of all hospital beds in the United States were occupied by psychiatric patients, which is another historical indication of the societal impact of psychiatry.

- Alcohol and drug abuse are undoubtedly one of society’s most intractable problems. They are not only psychiatric disorders, but are often associated with multiple other psychiatric comorbidities and can lead to a host of general medical and surgical consequences. They are not only costly in financial terms, but they also lead to an increase in crime and forensic problems. Premature death is a heavy toll for society due to alcohol and substance use, as the opioid epidemic clearly has demonstrated over the past few years.

- Homelessness is an endemic sociological cancer in the body of society and is very often driven by psychiatric disorders and addictions. Countless numbers of severely mentally ill patients became homeless when asylums were closed and they were “freed” from restrictive institutional settings. Homelessness and imprisonment became the heavy and shameful price of “freedom” for persons with disabling psychiatric disorders in our “advanced” society.

- Suicide, both completed and attempted, is intimately associated with psychiatric disorders. Approximately 47,000 deaths from suicide were reported in the United States in 2017.4 Given that more than 30 million Americans suffer from mood disorders, millions of suicide attempts take place, crowding the emergency rooms of the country with individuals who need to receive emergent health care. The tragic toll of suicide and the heavy medical care costs of suicide attempts are incalculable, and unfortunately have been growing steadily over the past 20 years.

- Homicide is sometimes committed by persons with a psychiatric disorder, most commonly antisocial personality disorder. The rate of homicide often is used as a measure of a city’s quality of life, and urban areas where access to psychiatric care is limited tend to have high homicide rates.

- School problems, whether due to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, below-average intellectual abilities, conduct disorder, bullying, impulsive behavior, substance use, broken homes, or dysfunctional families (often due to addictive or psychiatric disorders), are a major societal problem. Whether the problem is truancy, school fights, or dropping out before getting a high school diploma, psychiatric illness is frequently the underlying reason.

- Sexual controversies, such as expanding and evolving gender identity issues and discrimination against non-cisgender individuals, have instigated both positive and negative initiatives in society. Sexual abuse of children and its grave psychiatric implications in adulthood continues to happen despite public outrage and law enforcement efforts, and is often driven by individuals with serious psychopathology. In addition, sexual addiction (and its many biopsychosocial complications) is often associated with neuropsychiatric disorders.

- Poverty and the perpetual underclass are often a result of psychiatric disorders, and represent an ongoing societal challenge that has proven impossible to fix just by throwing money at it. Whether the affected individuals are seriously mentally ill, addicted, cognitively impaired or challenged, or unmotivated because of a neuropsychiatric disorder, poverty is practically impossible to eliminate.

- One positive impact of psychiatry in society is that artistic abilities, writing talent, musical creativity, entrepreneurship, and high productivity are often associated with certain psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar disorder, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and psychosis spectrum disorders. Society is enriched by the creative energy and out-of-the-box thinking of persons with mild to moderate neuropsychiatric disorders.

- The financial impact of psychiatry is massive. The direct and indirect costs of psychiatric and addictive disorders are estimated to be more than $400 billion/year. Even a single serious psychiatric disorder, such as schizophrenia, costs society approximately $70 billion/year. The same holds true for bipolar disorder and depression. Thus, psychiatry accounts for a substantial portion of the financial expenditures in society.

- And last but certainly not least are the impediments to psychiatric treatment for tens of millions of individuals in our society who need treatment the most: the lack of health insurance parity; the stigma of seeking psychiatric help; the serious shortage of psychiatrists, especially in inner-city areas and rural regions; the poor public understanding about psychiatric illness; and the fact that the success rate of psychiatric treatment is very similar to (and sometimes better than) that of serious cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal diseases. There are also many flawed religious, cultural, or philosophical belief systems that fail to accept that the mind is a product of brain biology and function and that psychiatric disorders are brain disorders that affect thought, mood impulses, cognition, and behavior, just as other brain disorders cause muscle weakness, epileptic seizures, or stroke. The public must understand that depression can be caused by stroke or multiple sclerosis, that Parkinson’s disease can cause hallucinations and delusions, and that brain tumors can cause personality changes.

Continue to: So, what should society do to address...

So, what should society do to address the multiple impacts of psychiatry on its structure and function? I have a brief answer: intensive research. If society would embark on a massive research effort to discover preventions and cures for psychiatric disorders, the return on investment would be tremendous in human and financial terms. Currently, only a miniscule amount of money (<0.5% of the annual cost of psychiatric disorders) is invested in psychiatric brain research. Society should embark on a BHAG (pronounced Bee Hag), an acronym for “Big Hairy Audacious Goal,” a term coined by Jim Collins and Jerry Poras, who authored the seminal book Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. The BHAG is an ambitious and visionary goal that steers a company (or in this case, society) to a much brighter future. It would be on the scale of the Manhattan Project in the 1940s, which developed the nuclear bomb that put an end to World War II. When it comes to psychiatry, society should do no less.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].