User login

Violaceous Papule With an Erythematous Rim

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

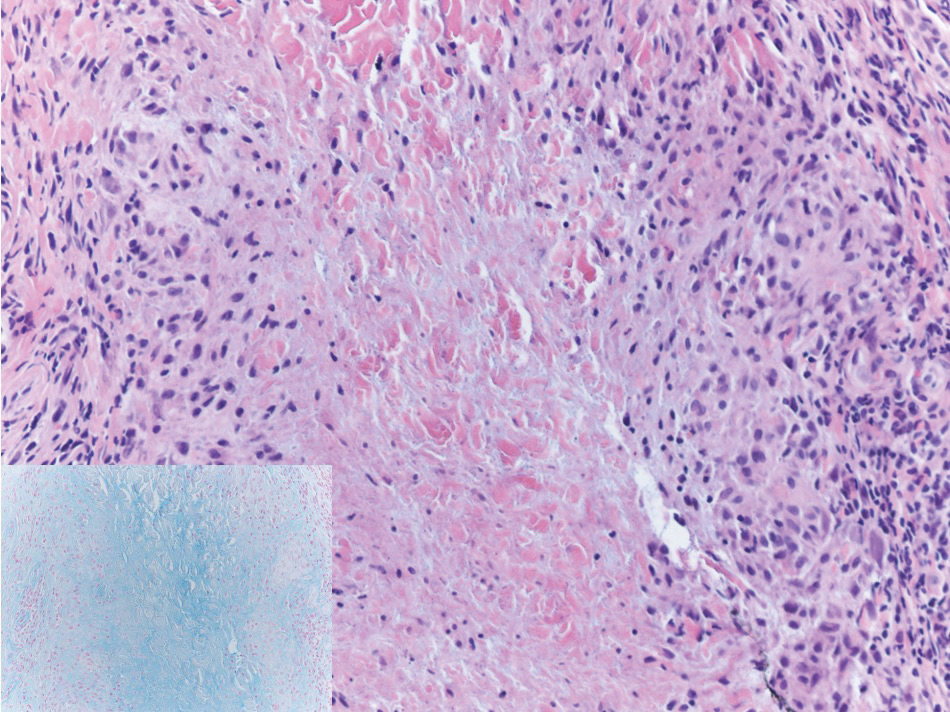

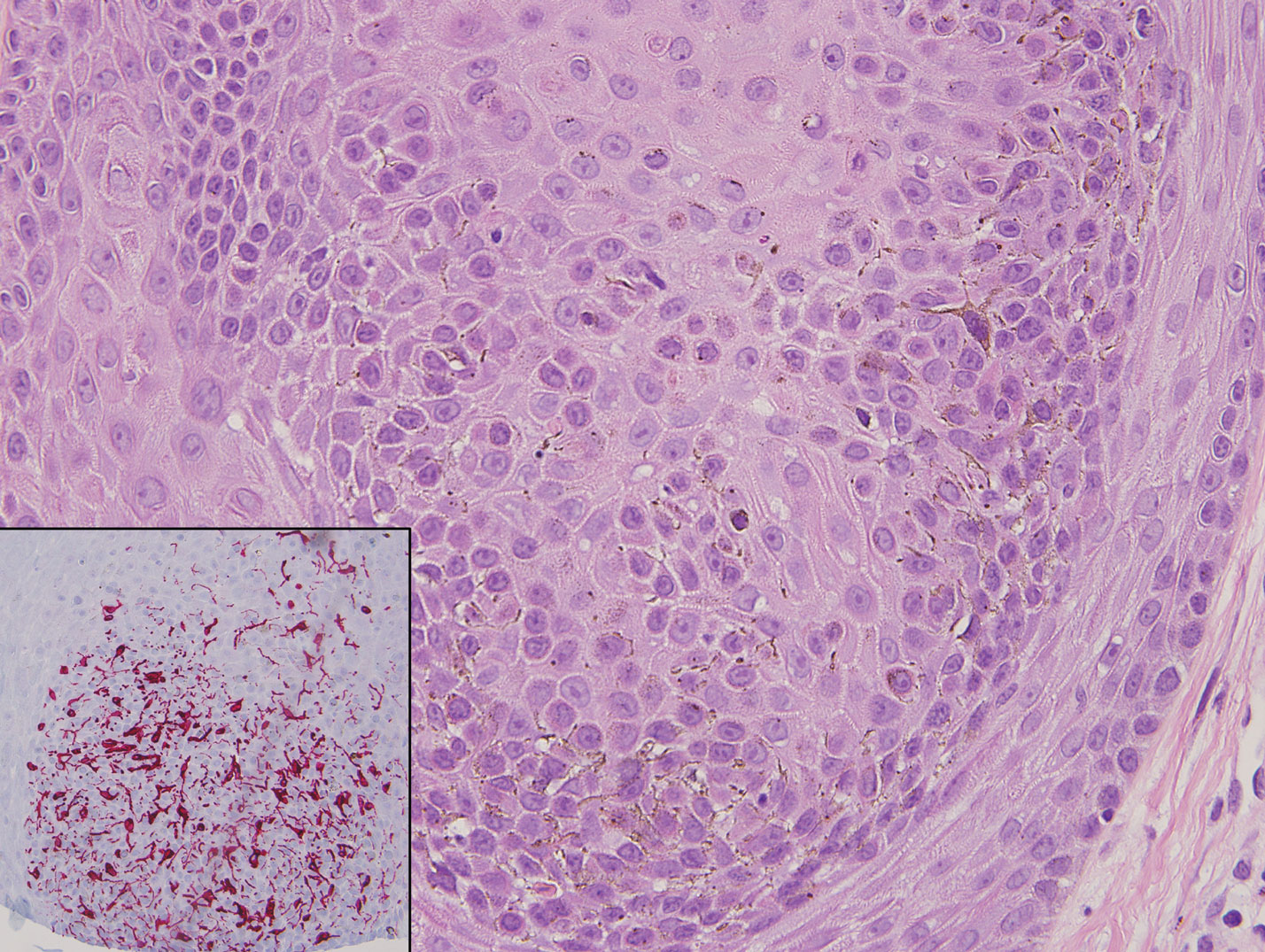

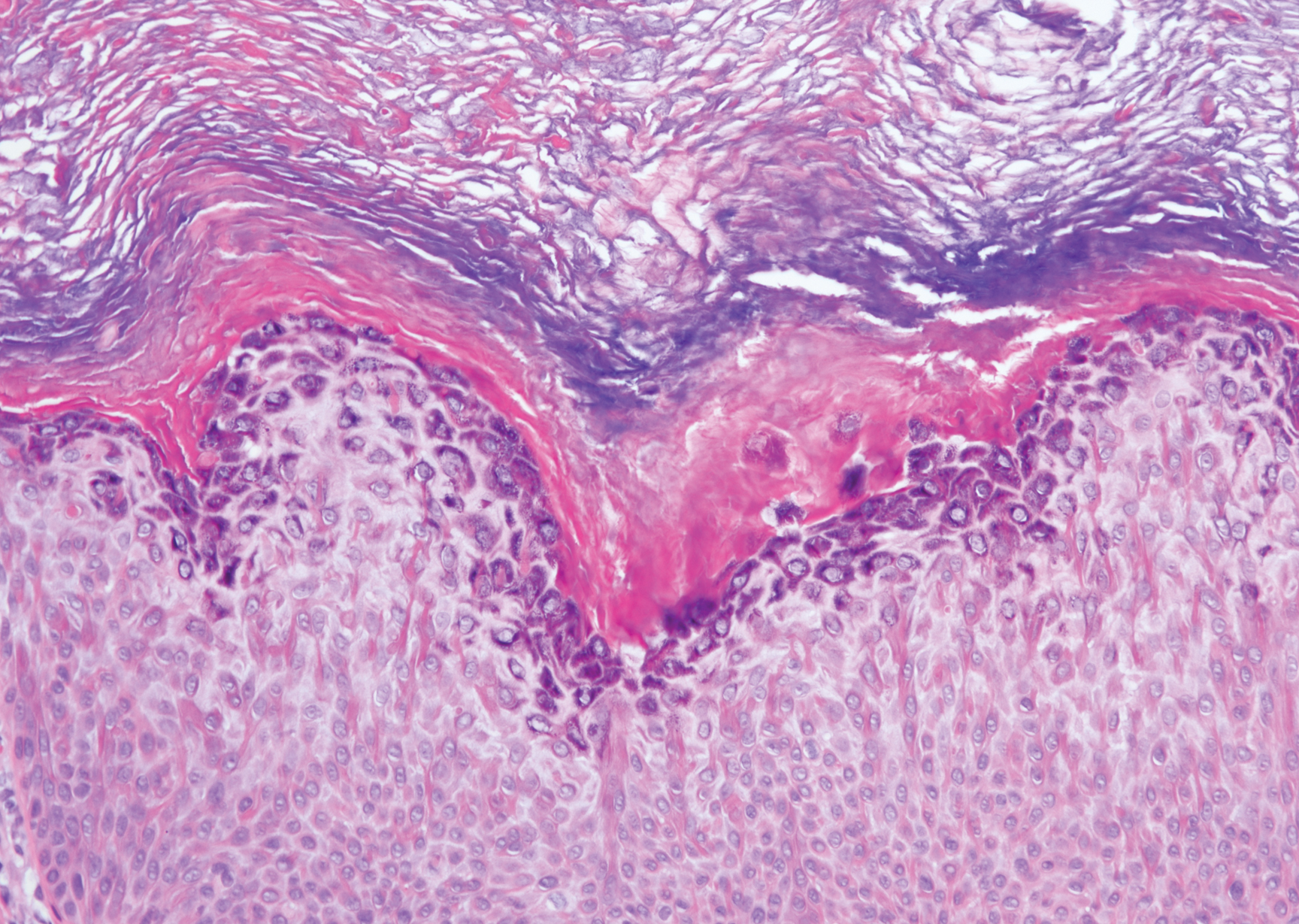

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

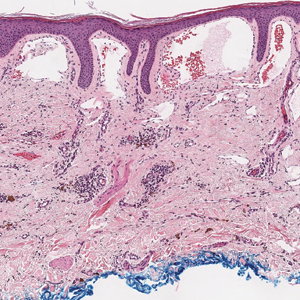

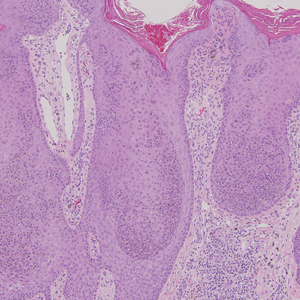

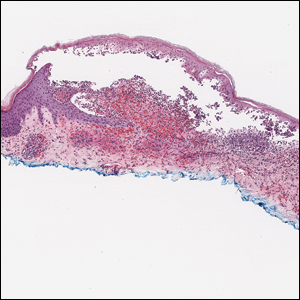

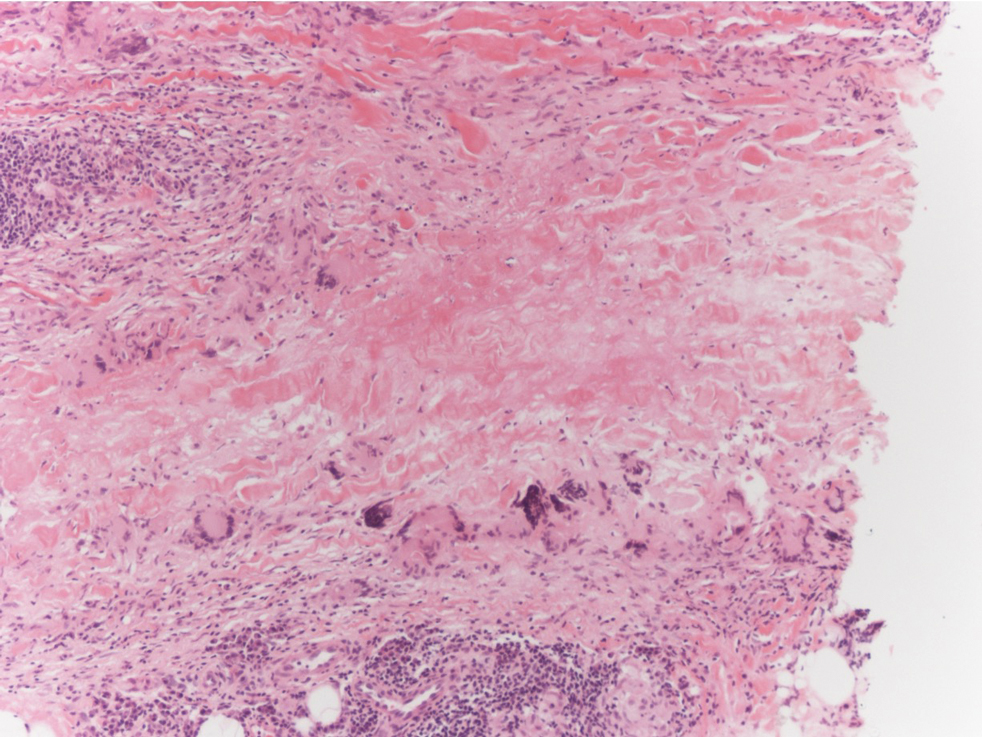

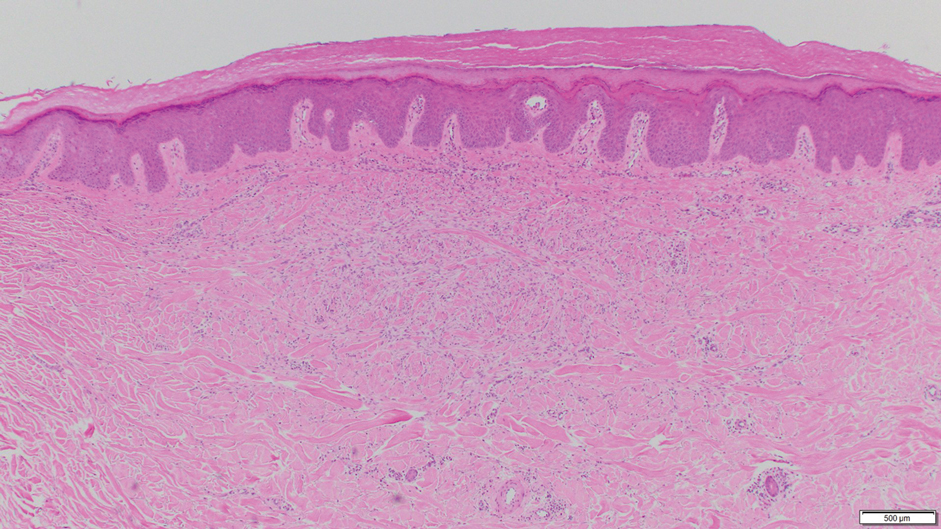

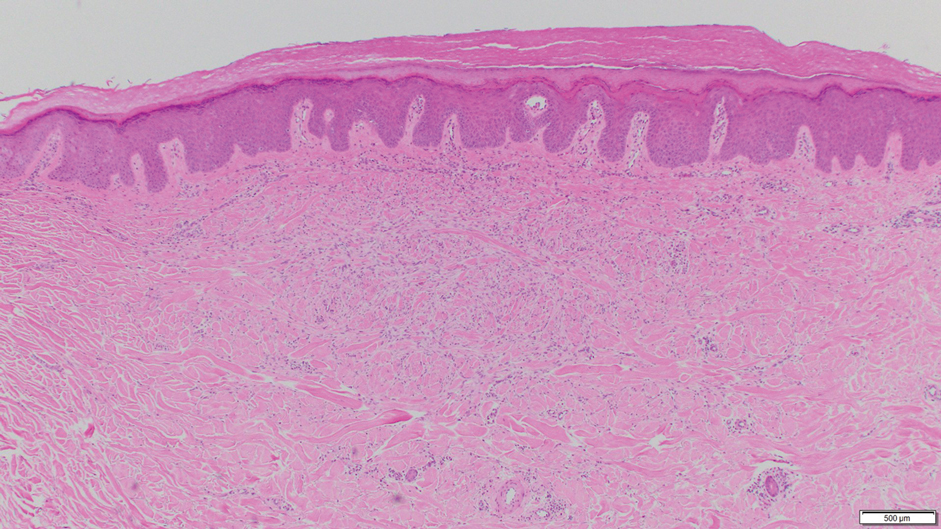

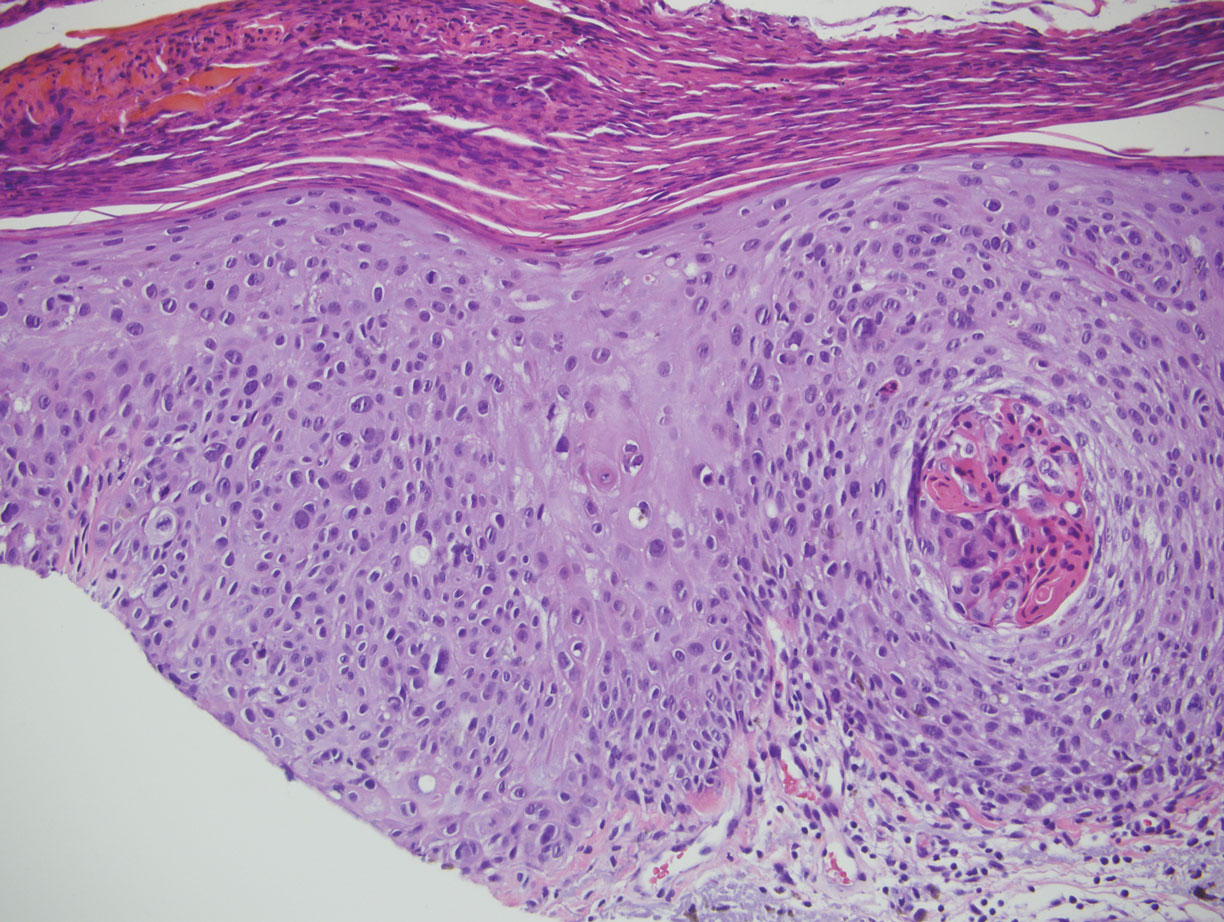

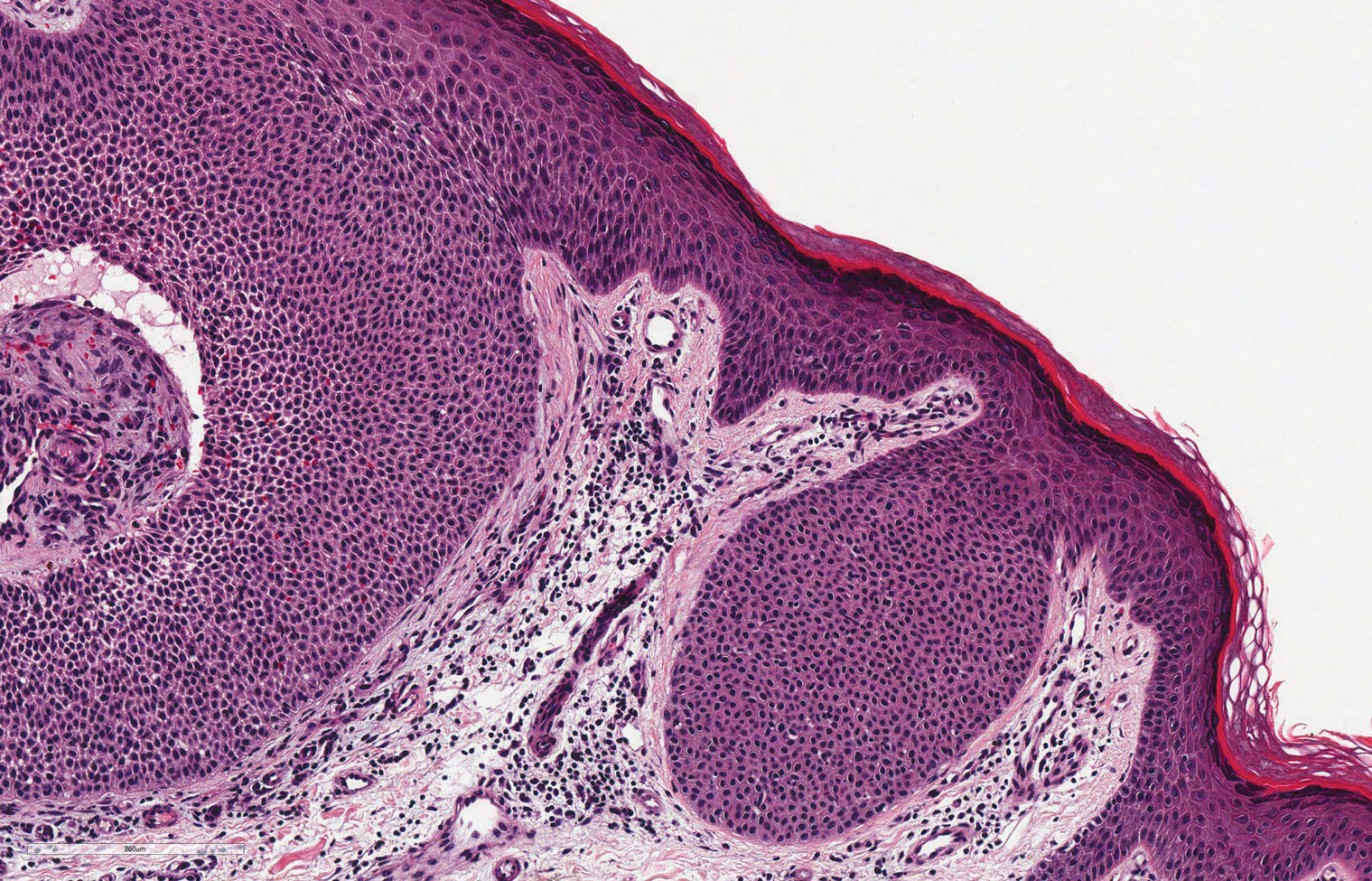

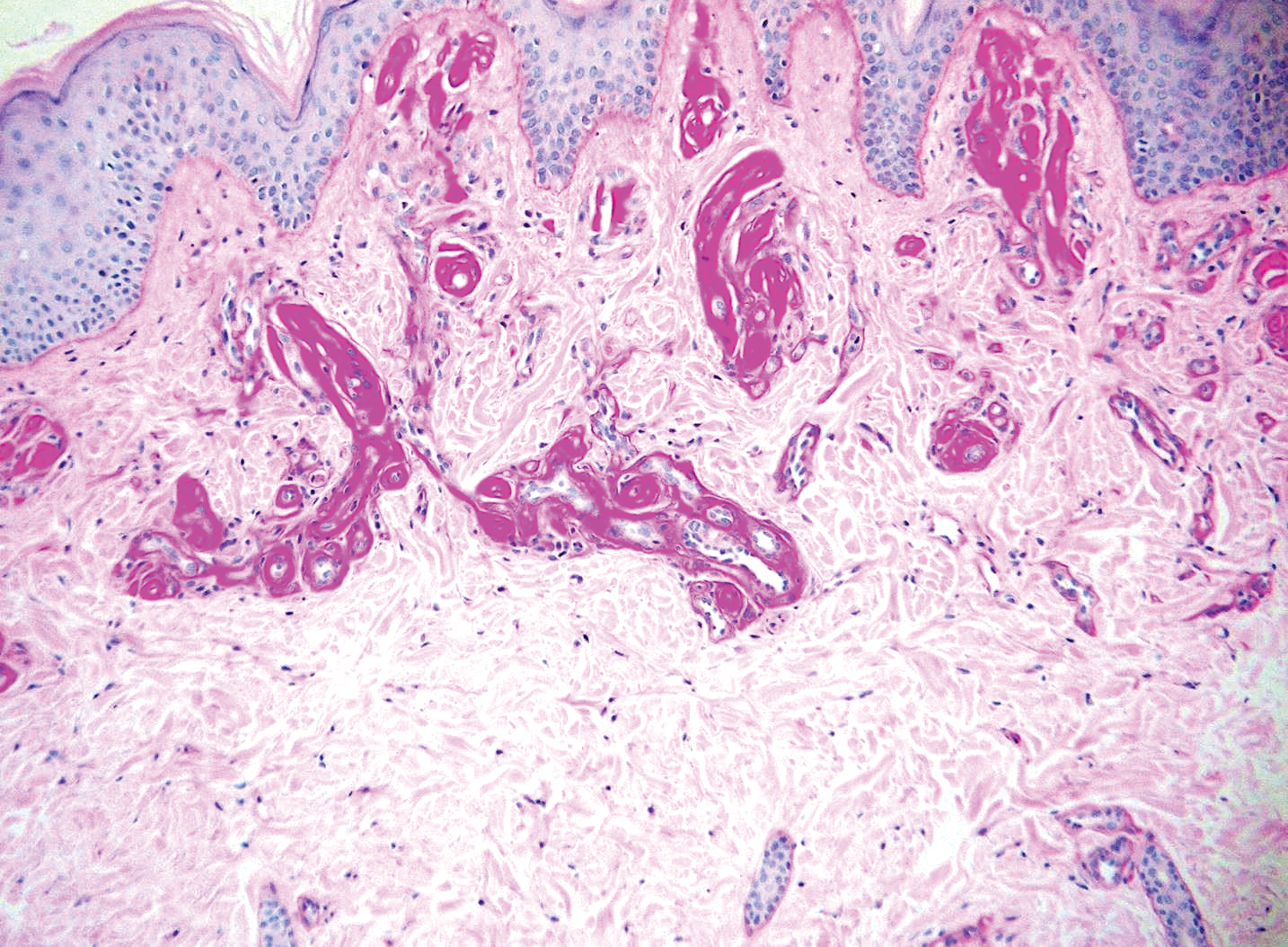

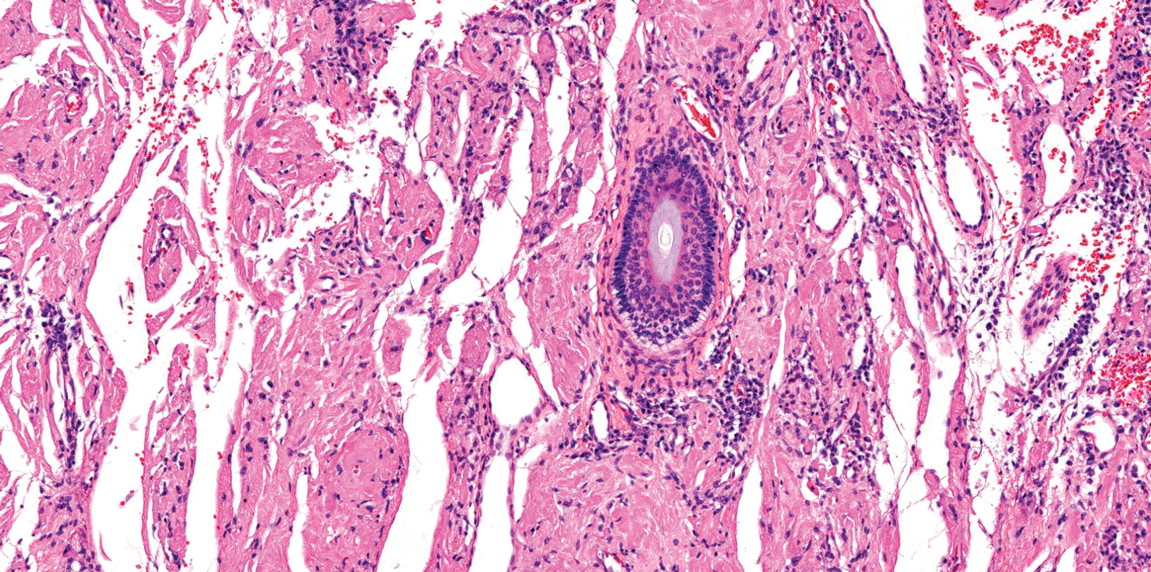

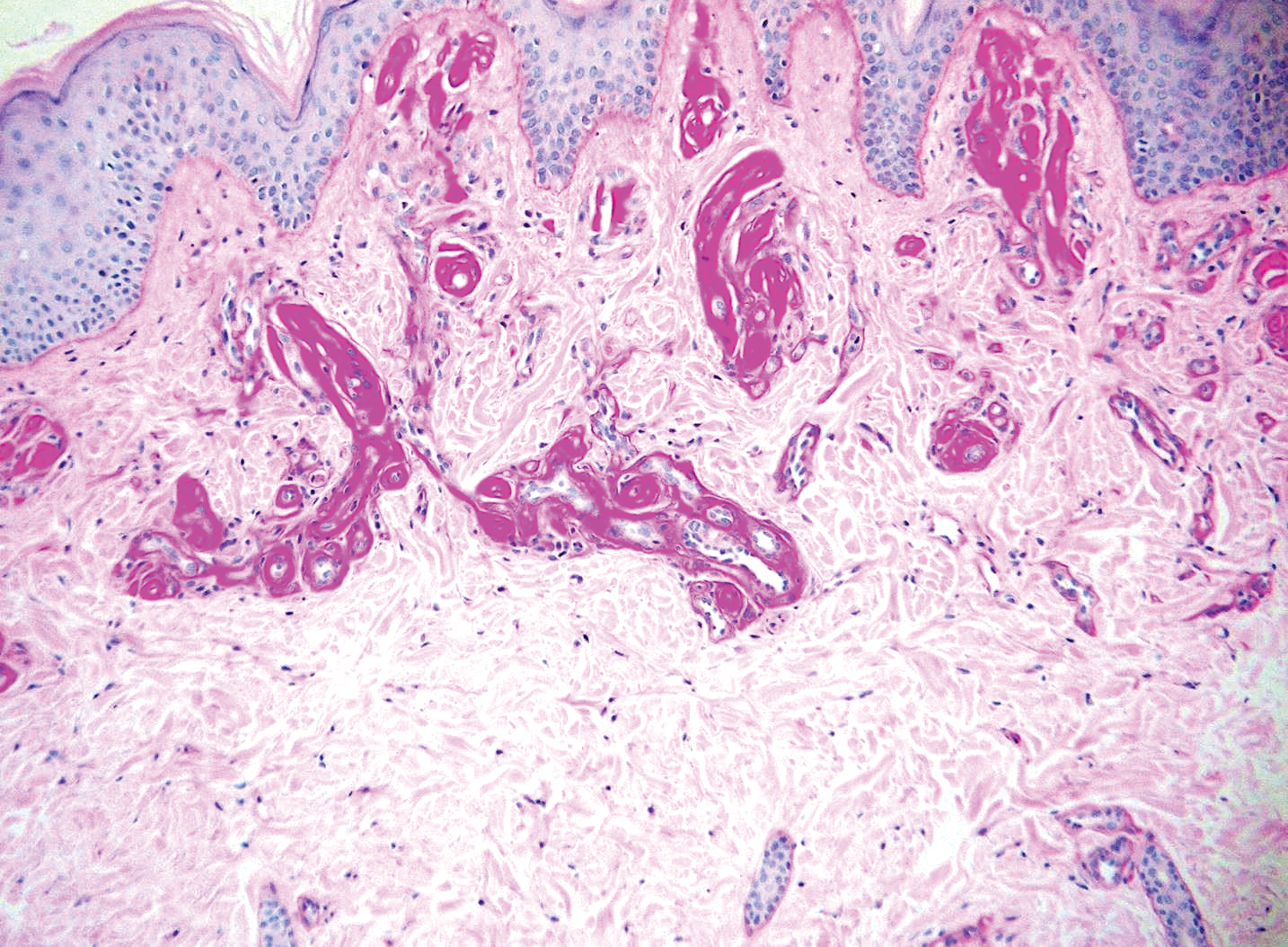

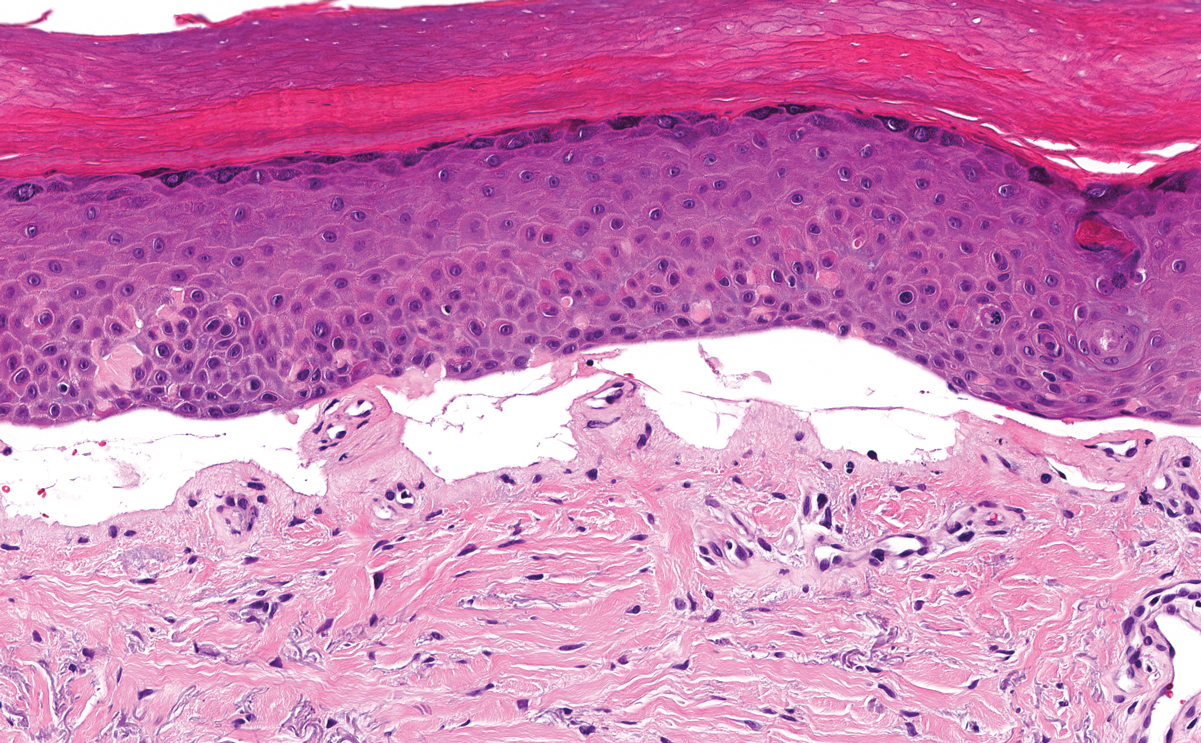

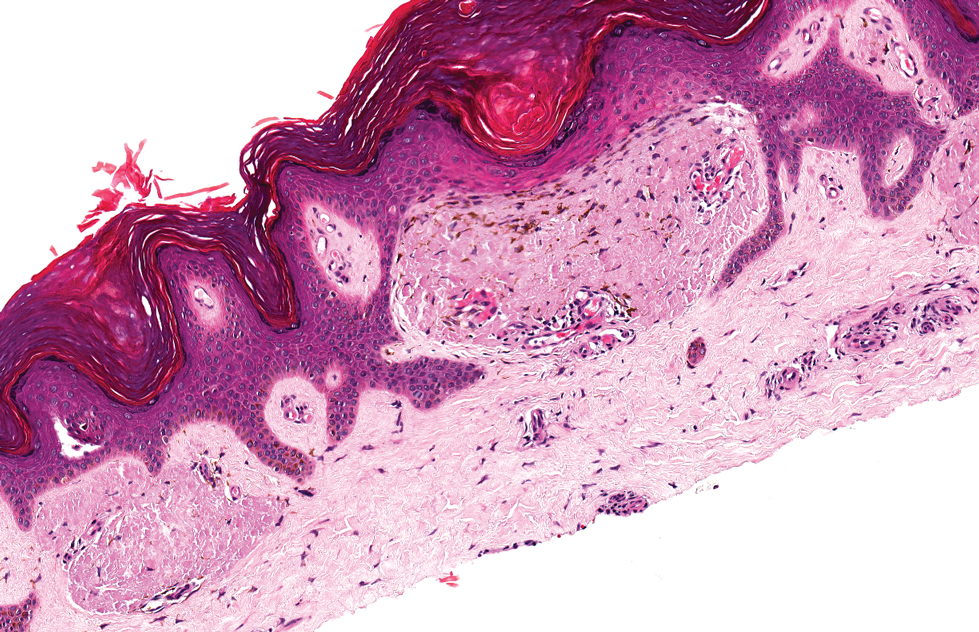

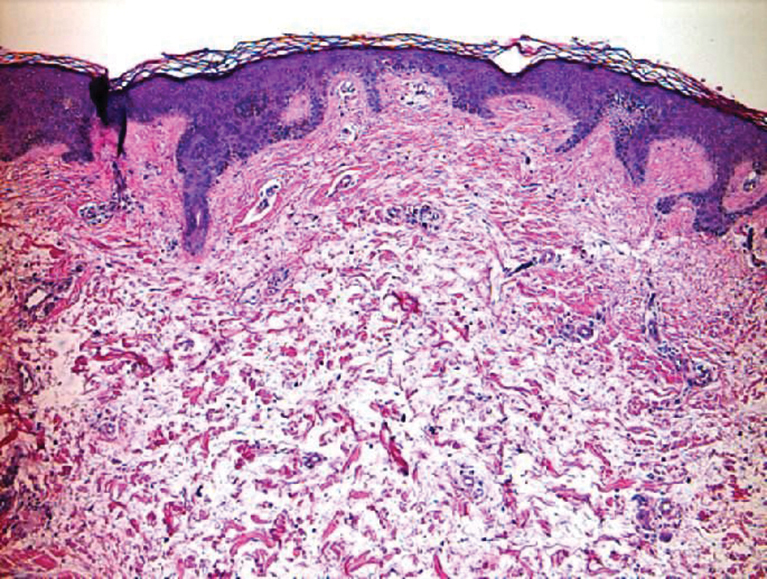

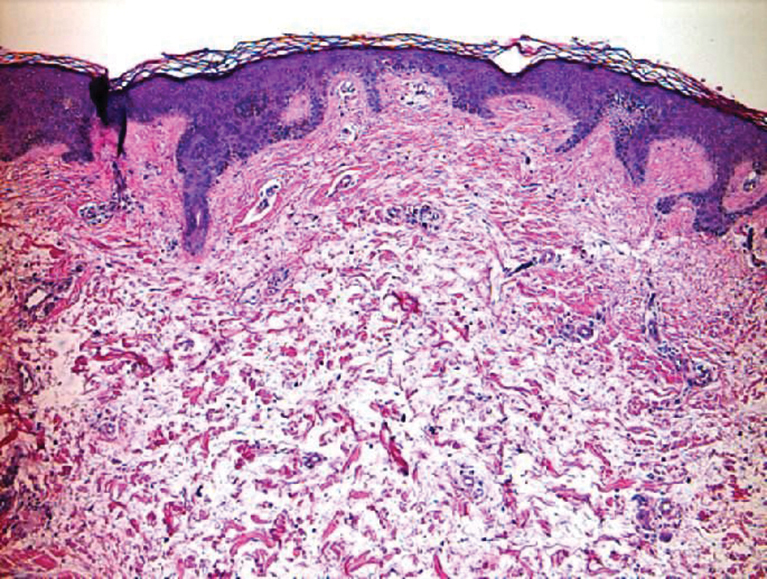

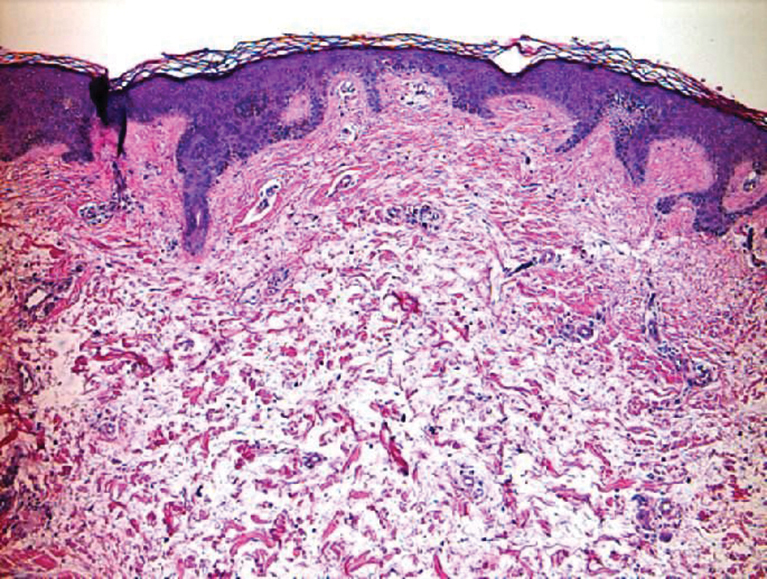

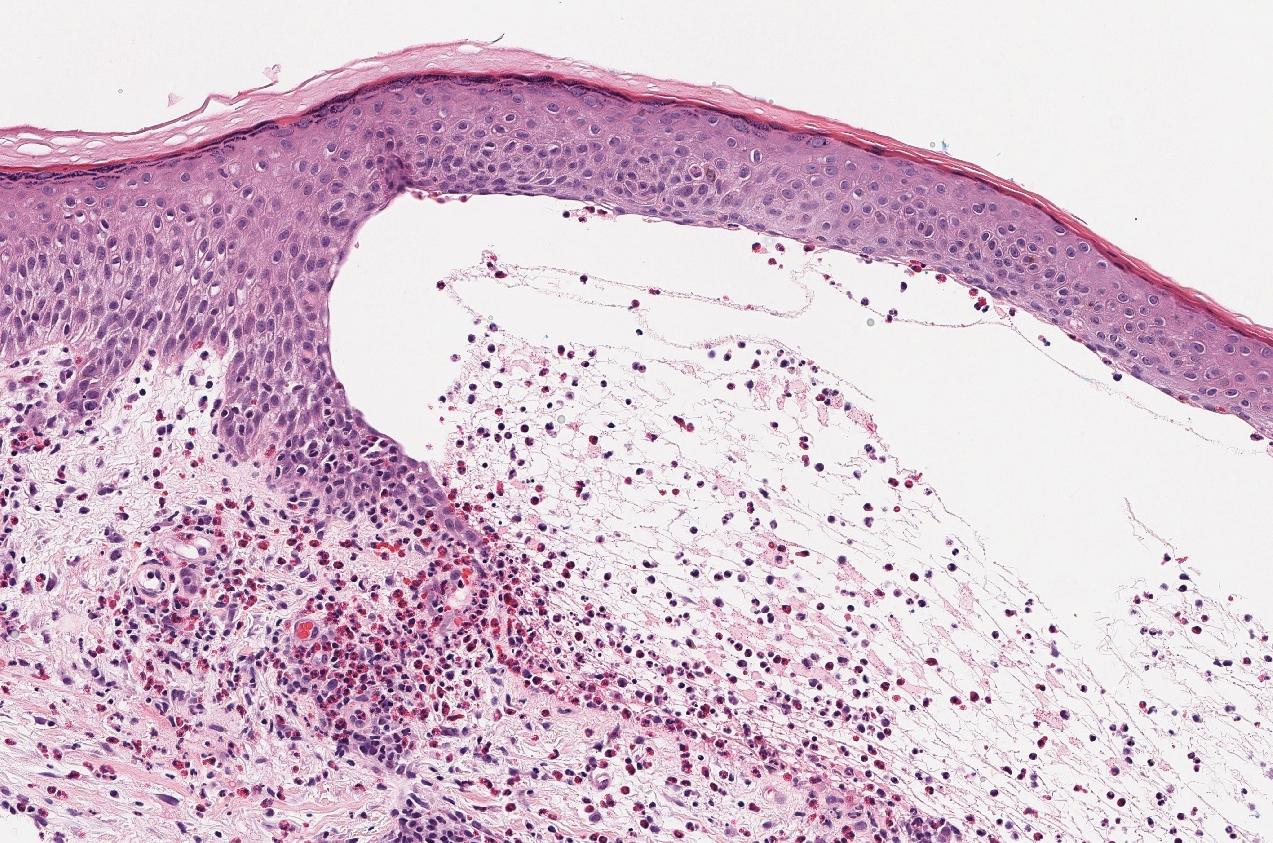

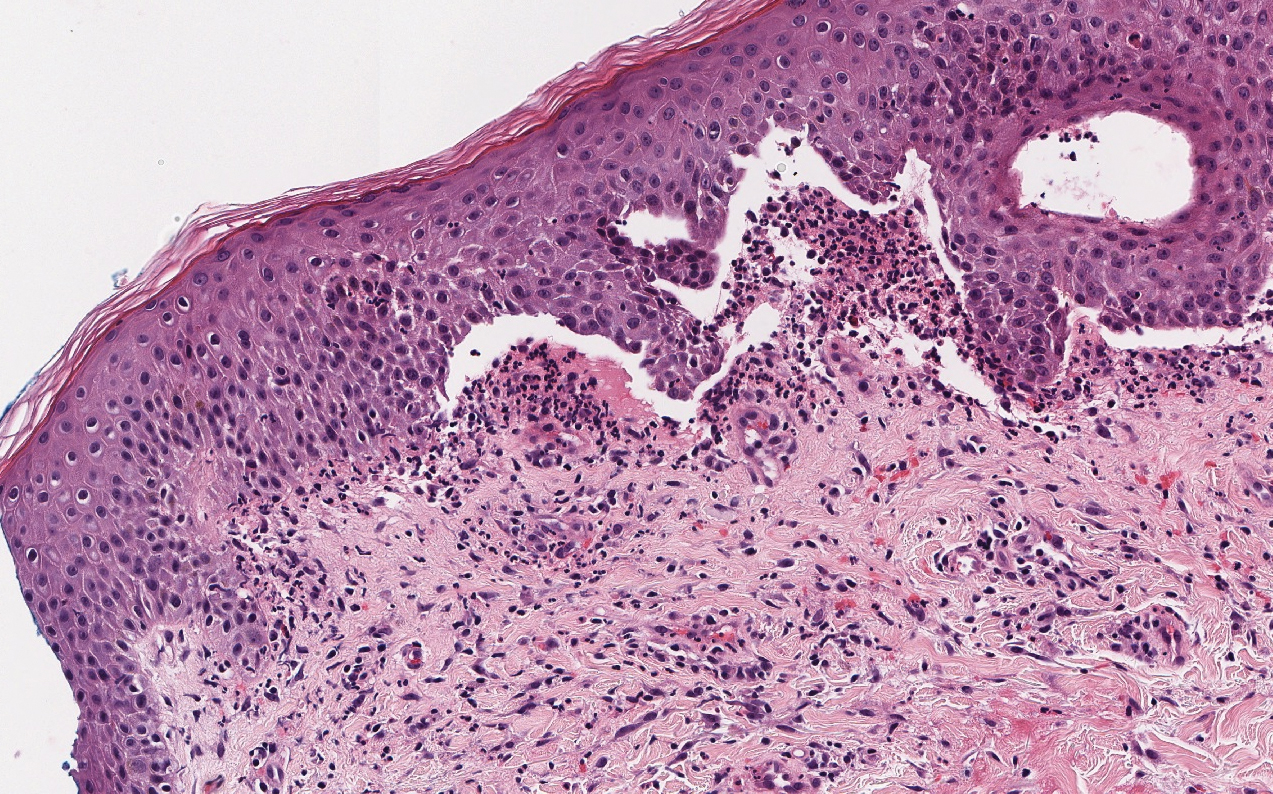

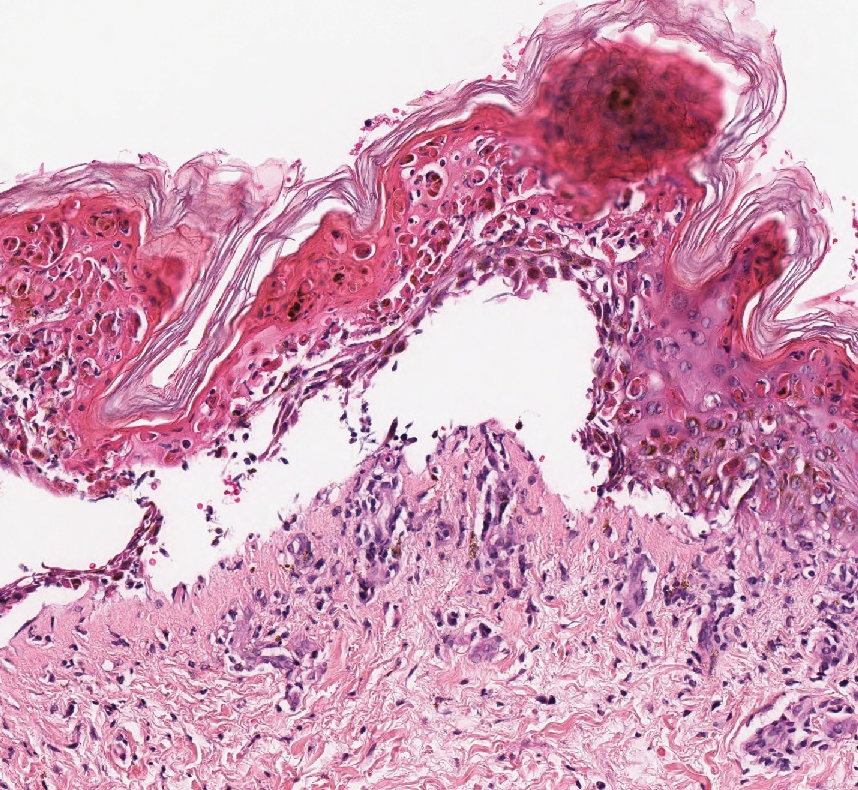

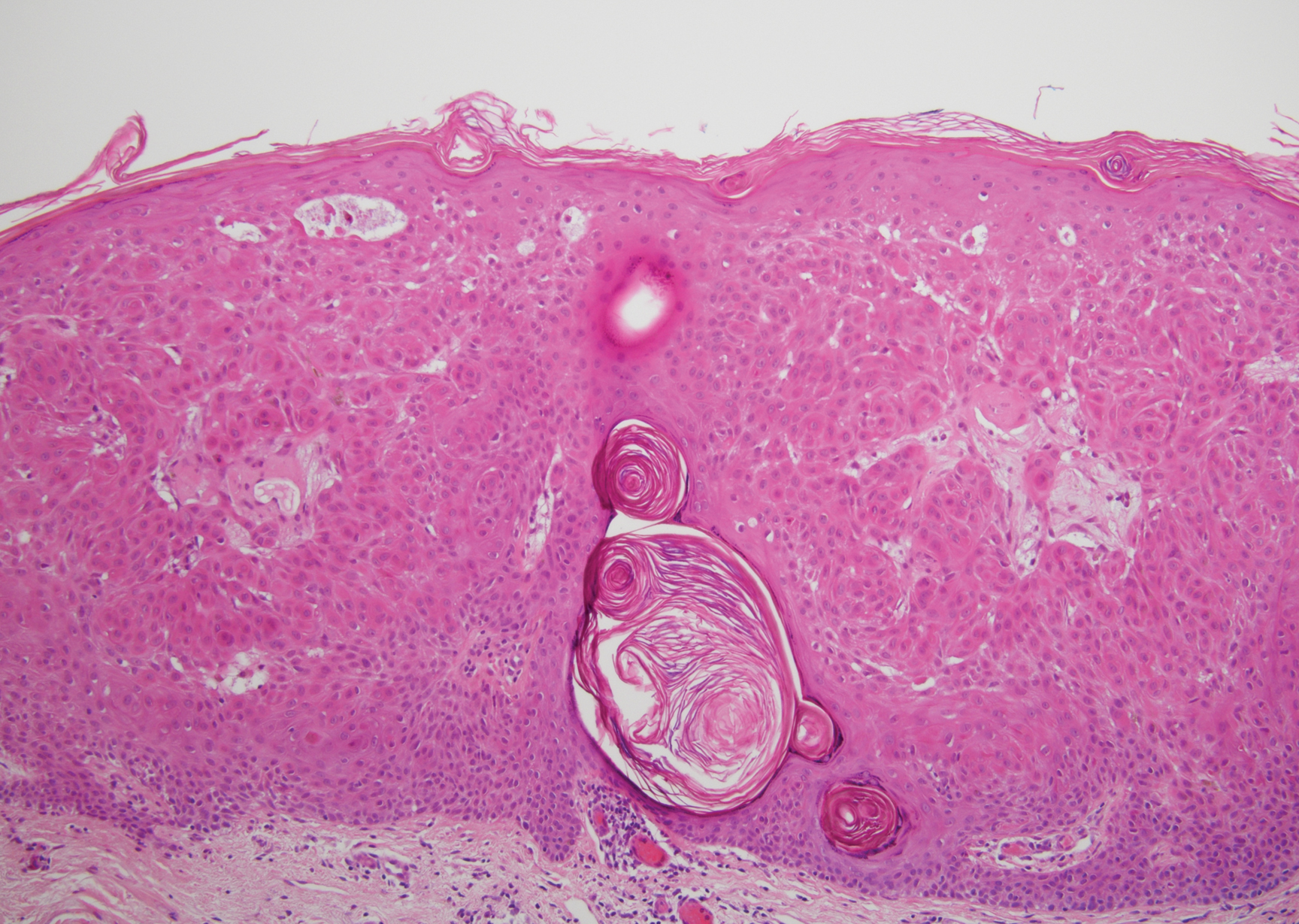

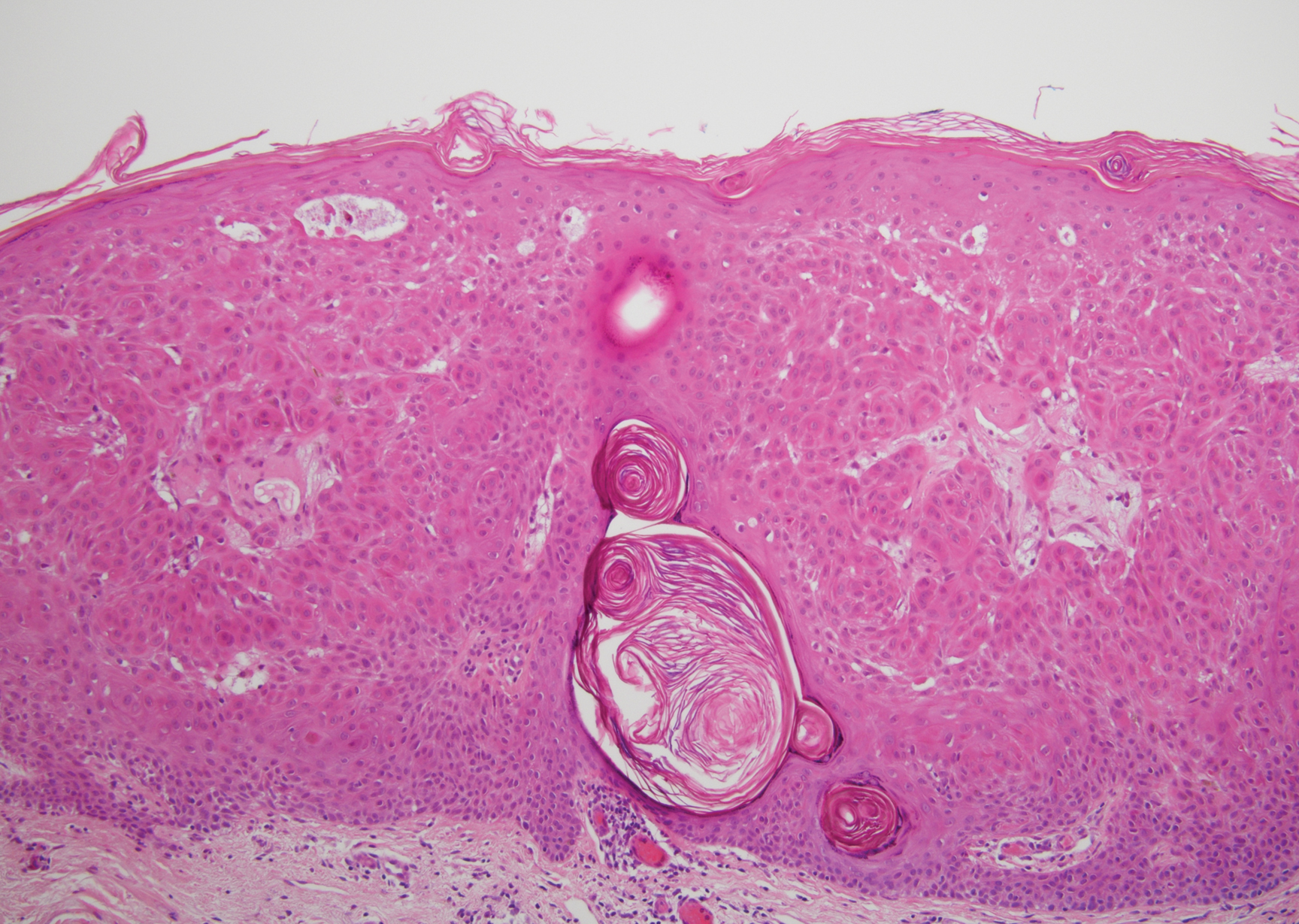

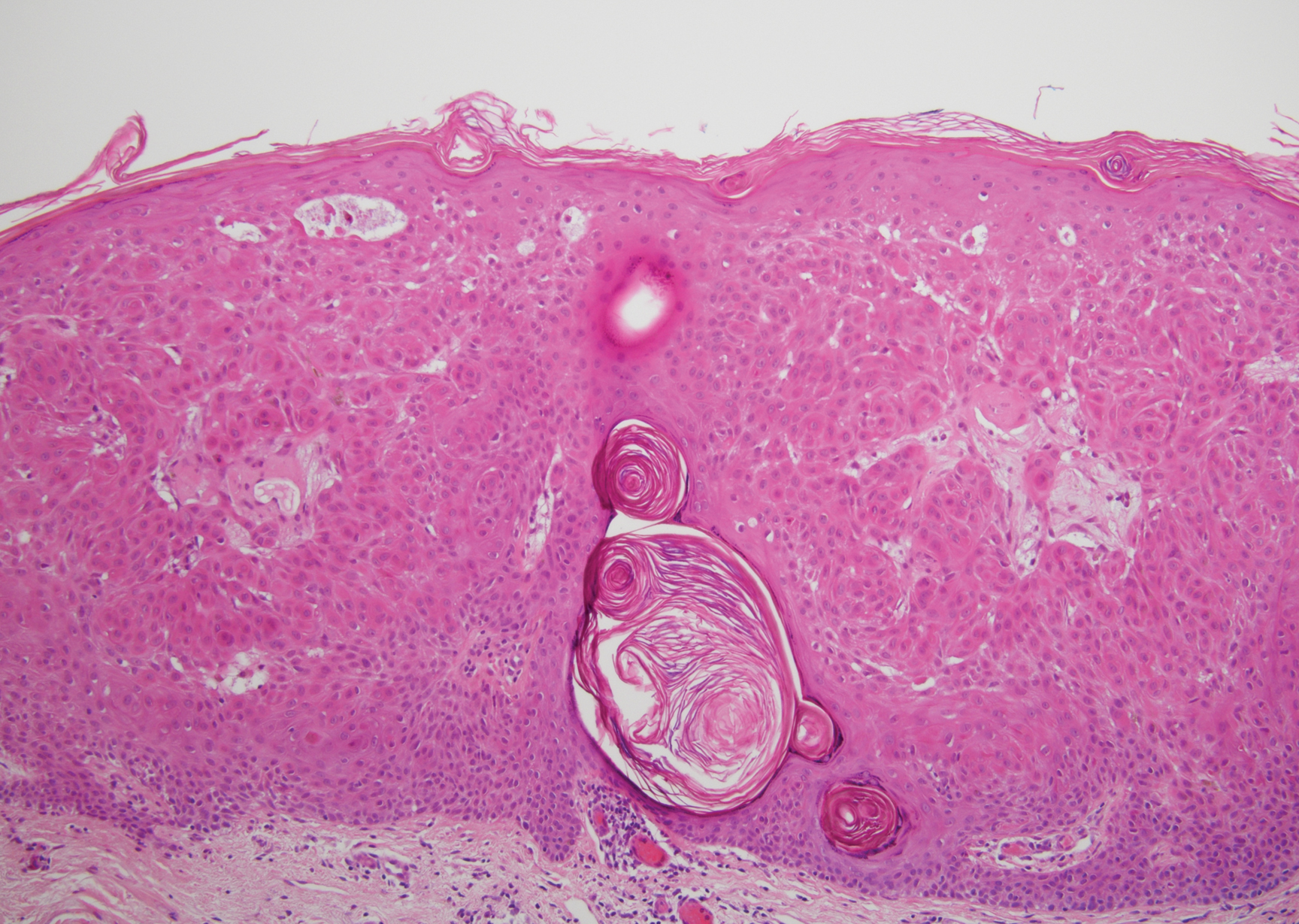

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

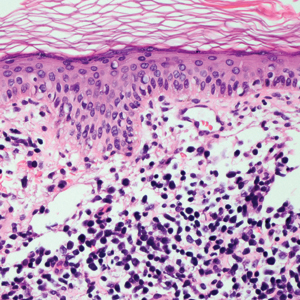

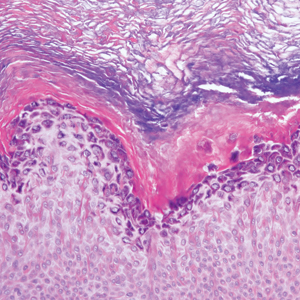

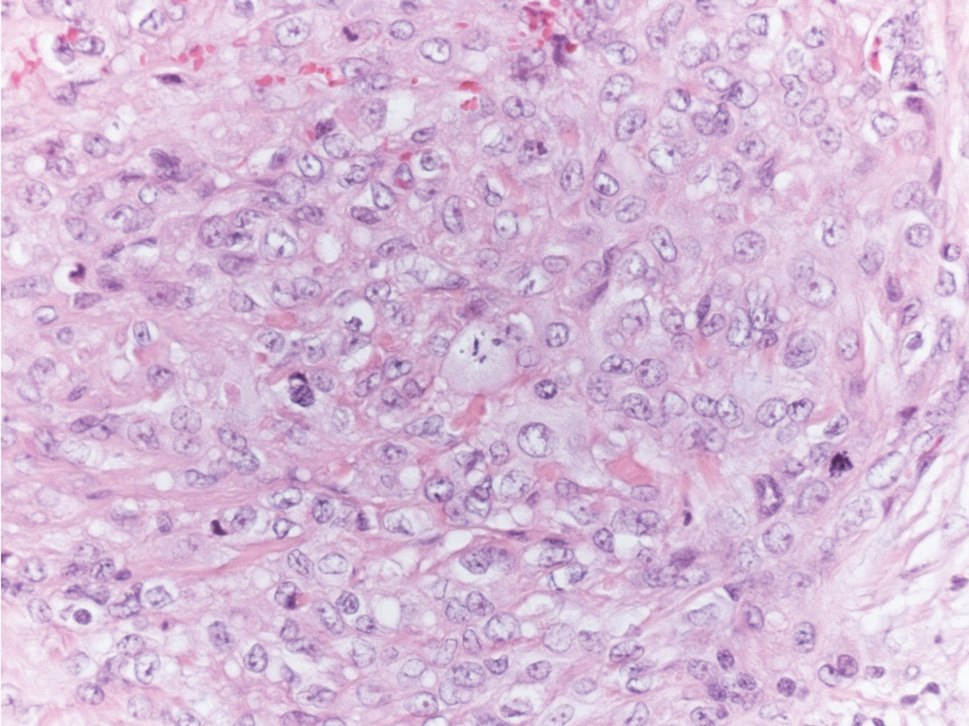

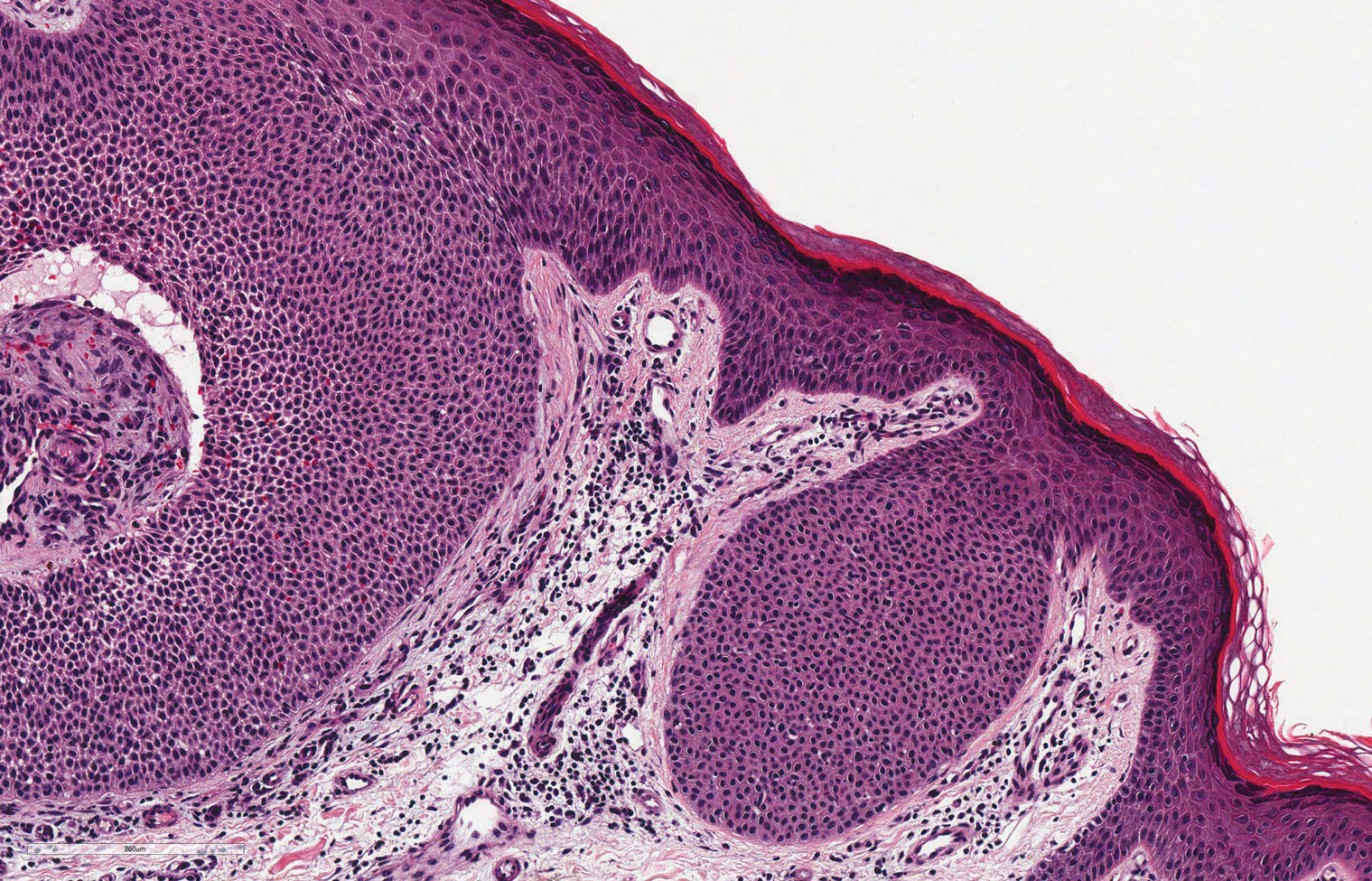

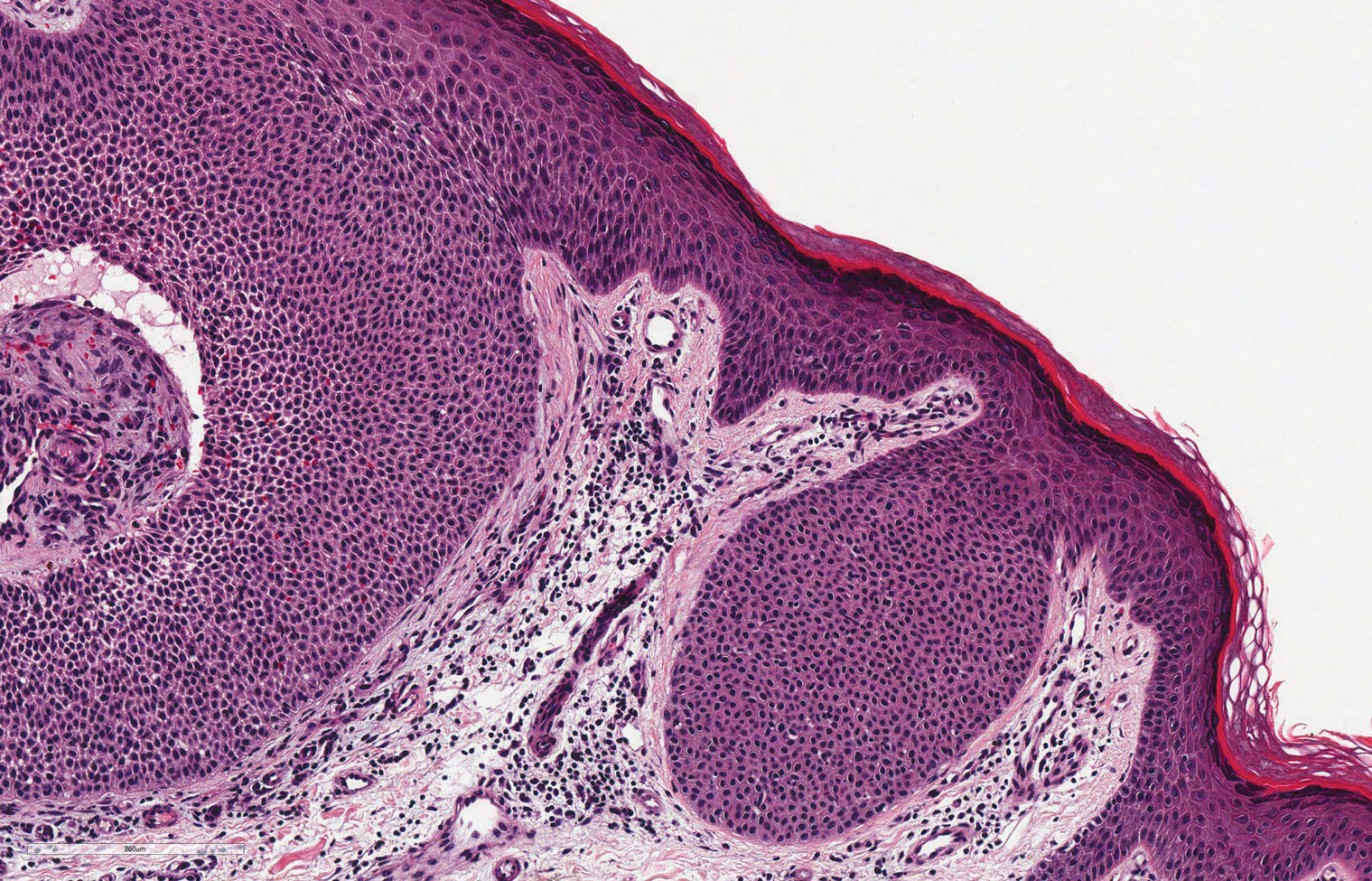

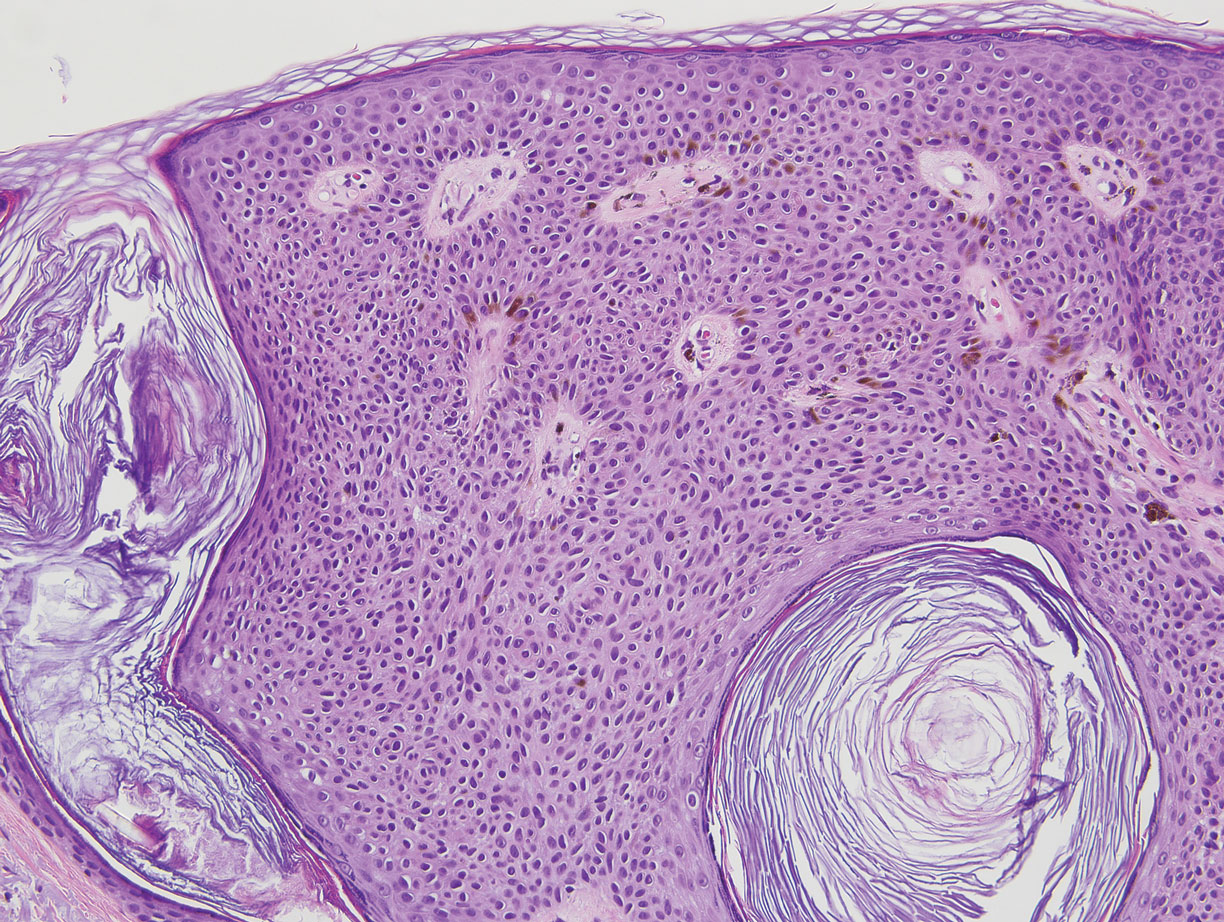

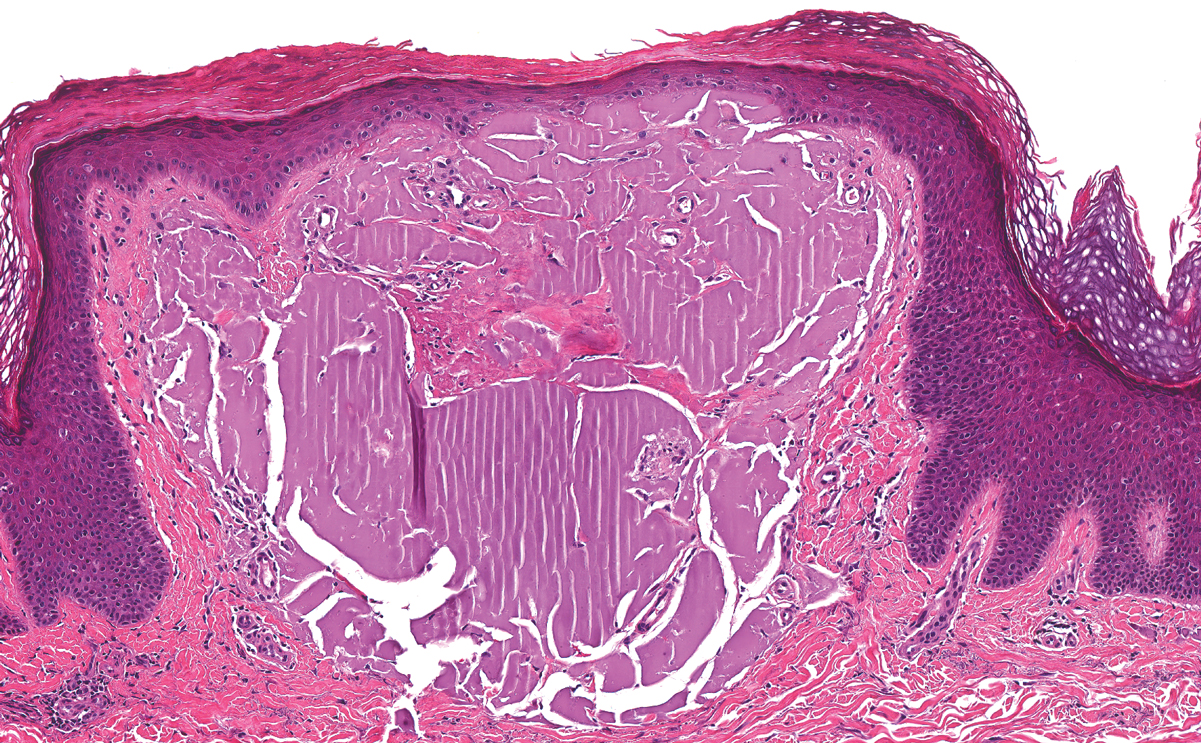

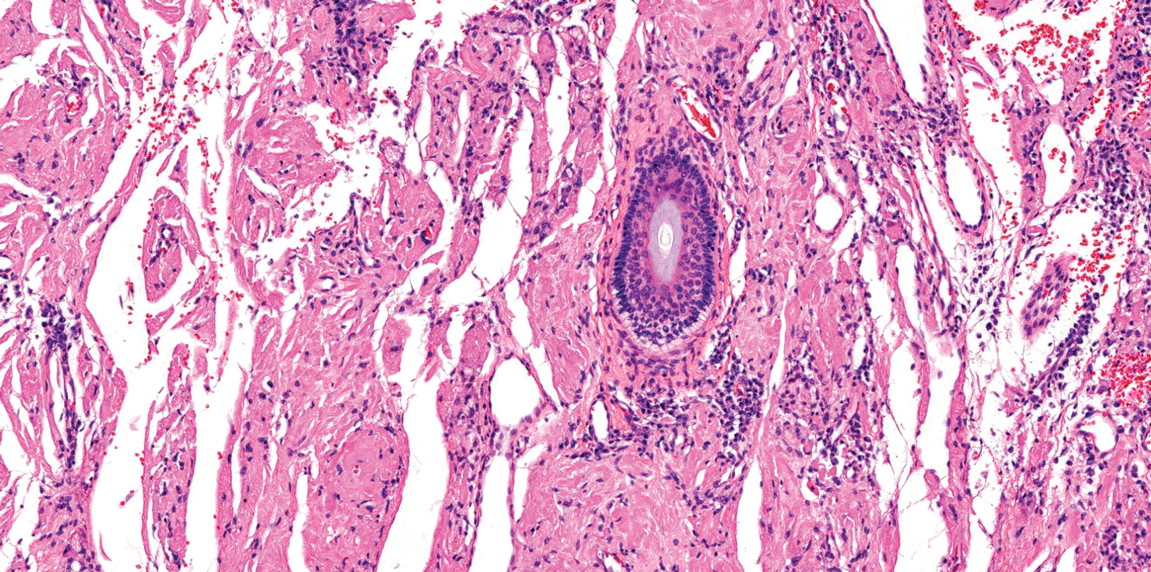

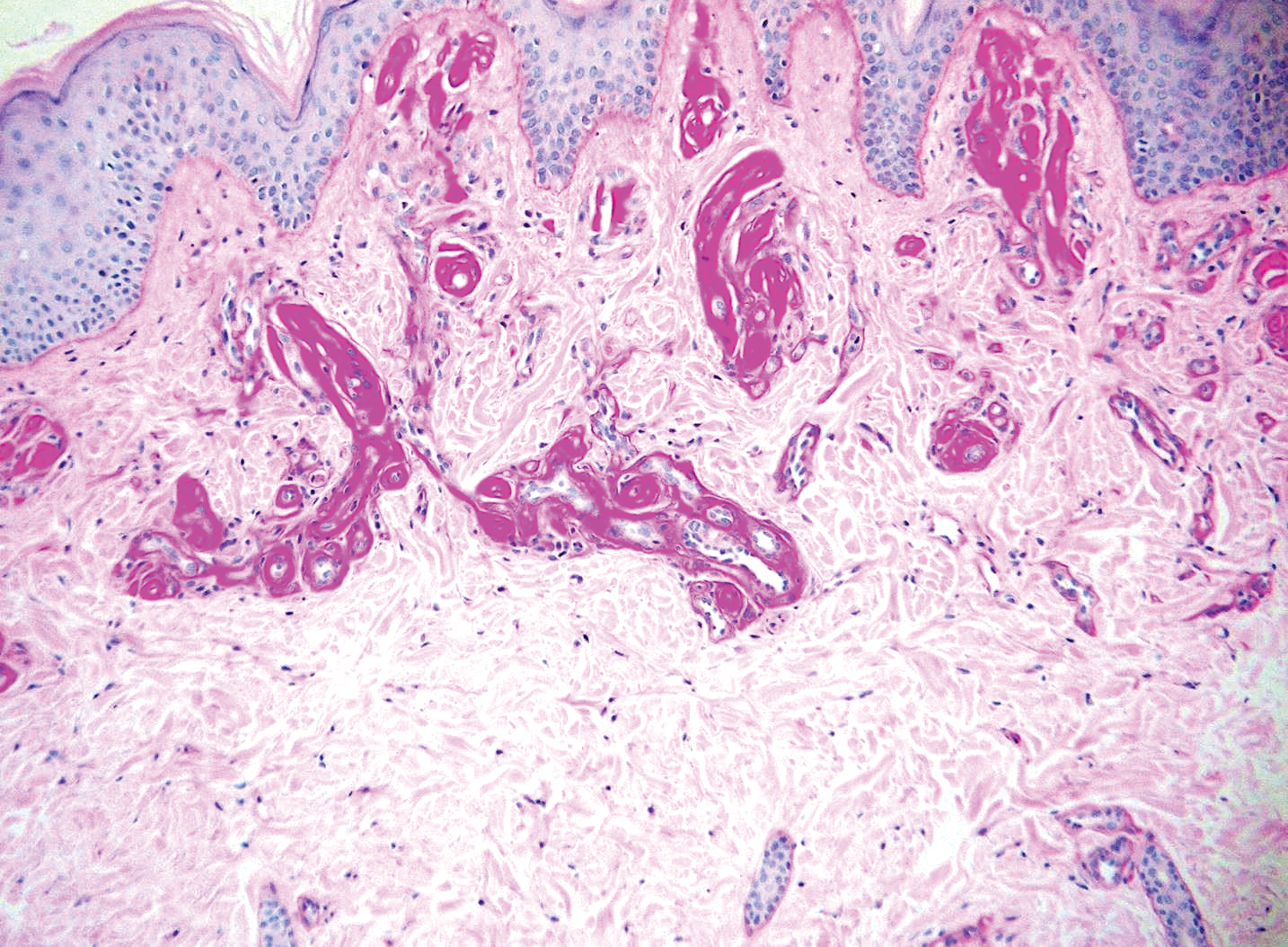

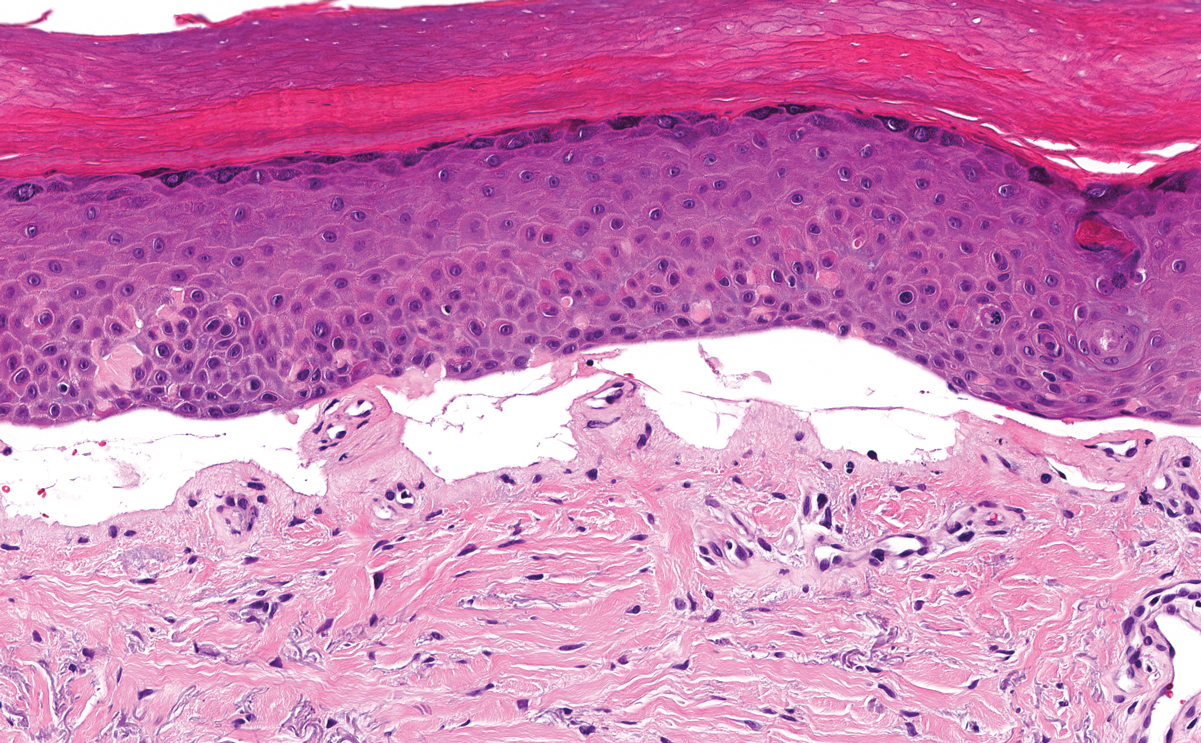

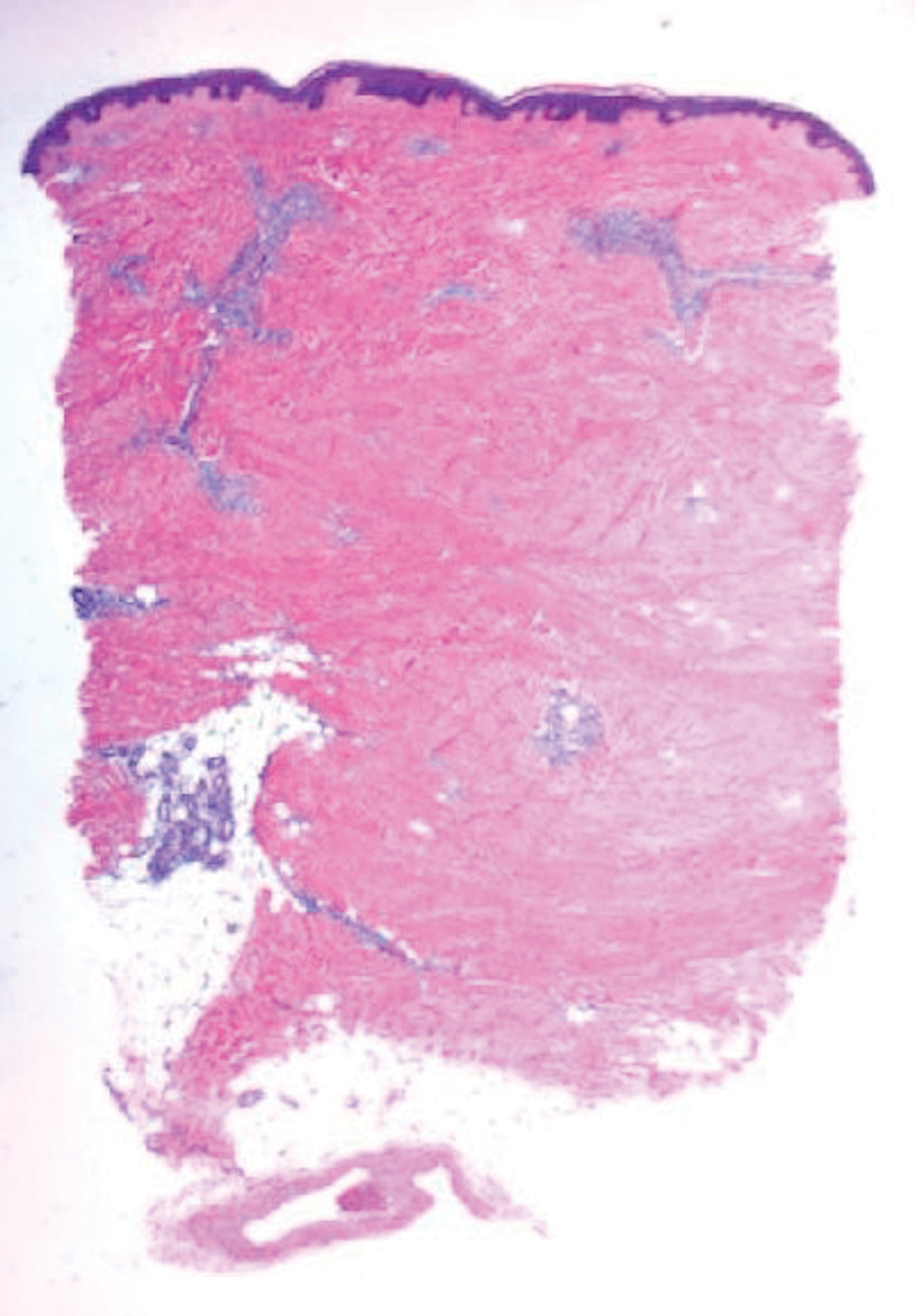

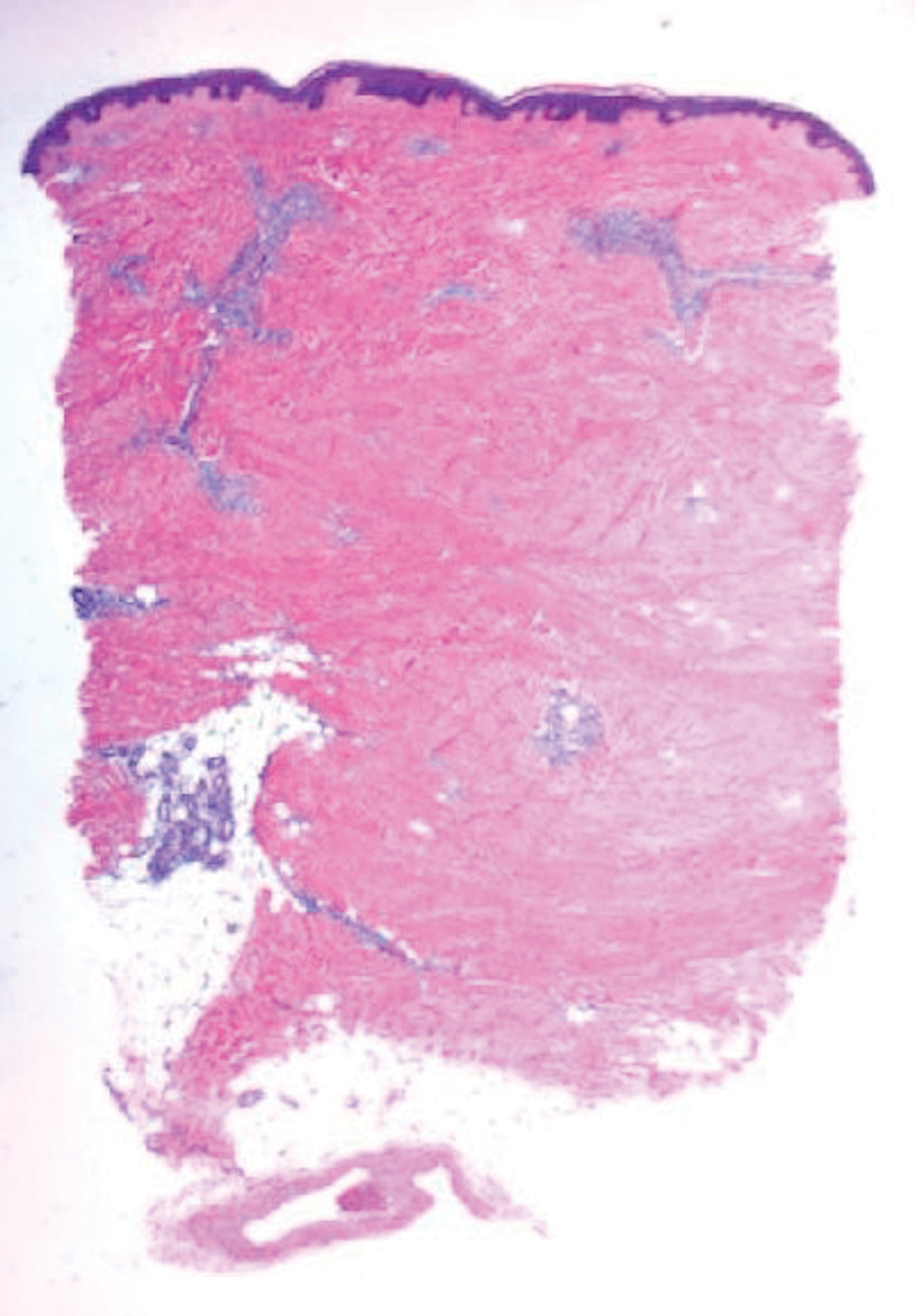

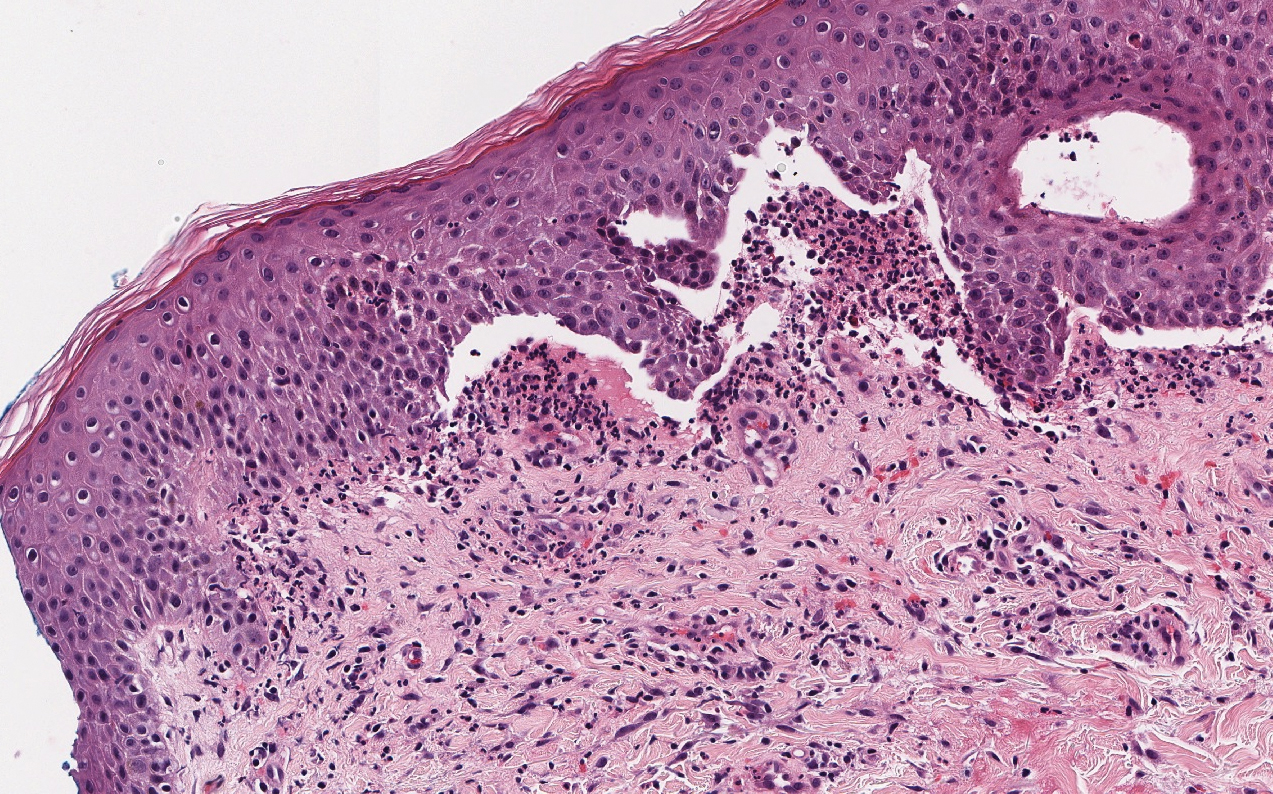

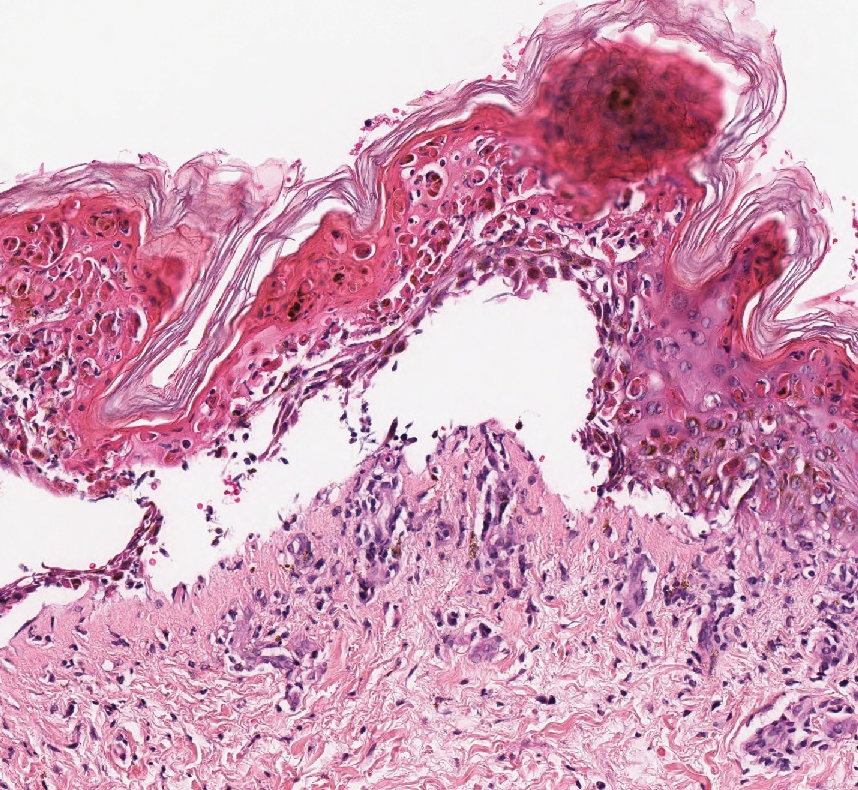

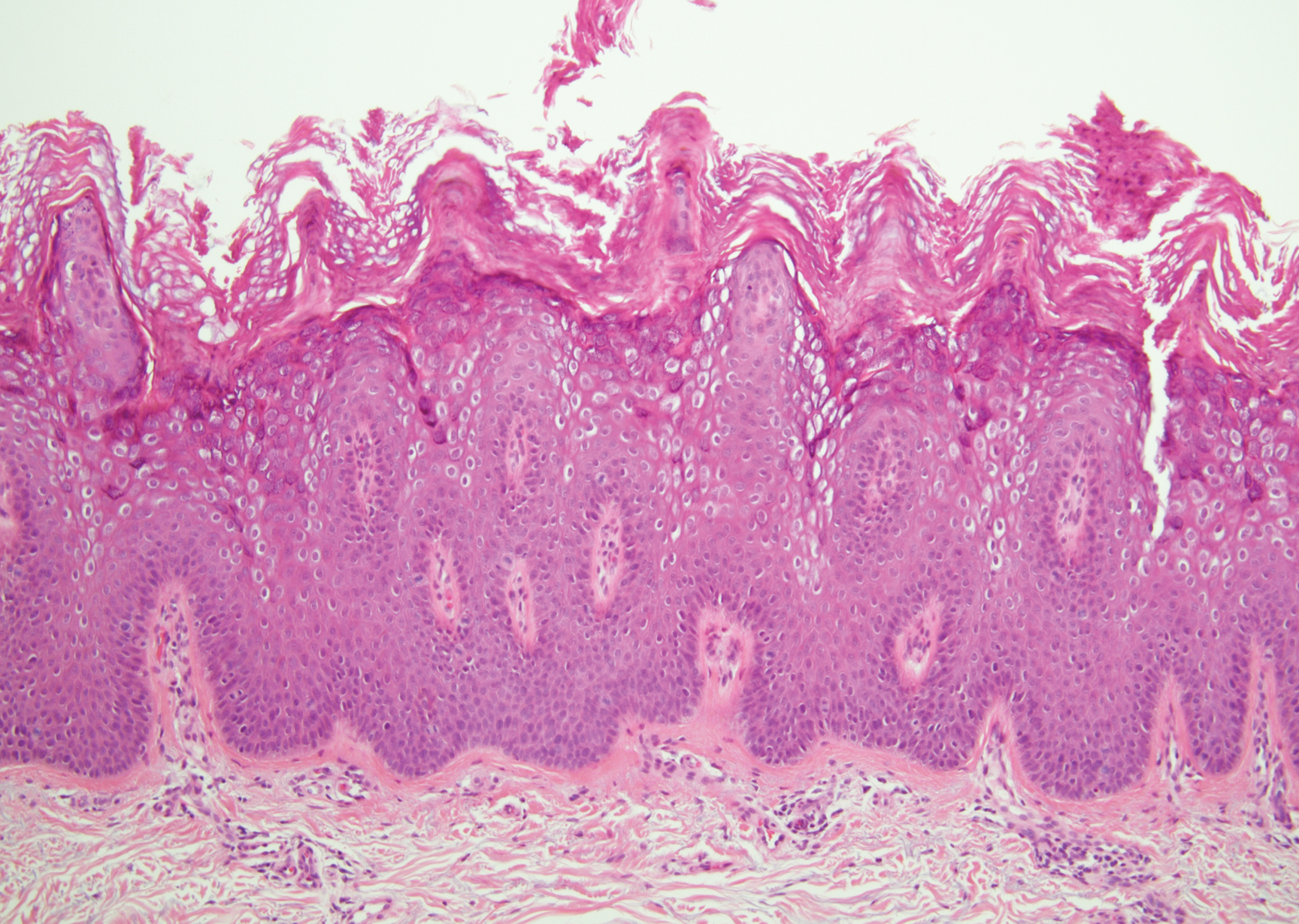

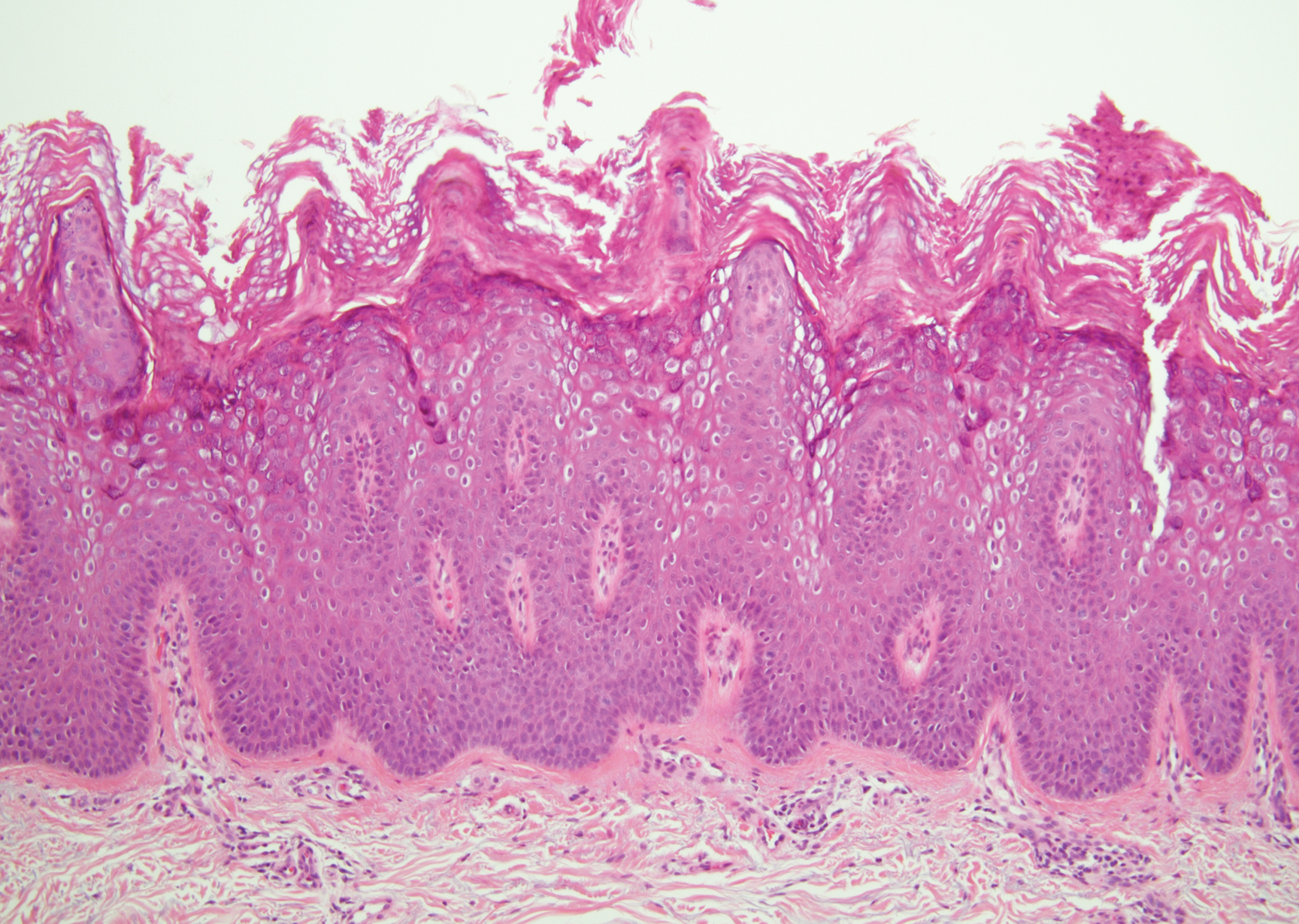

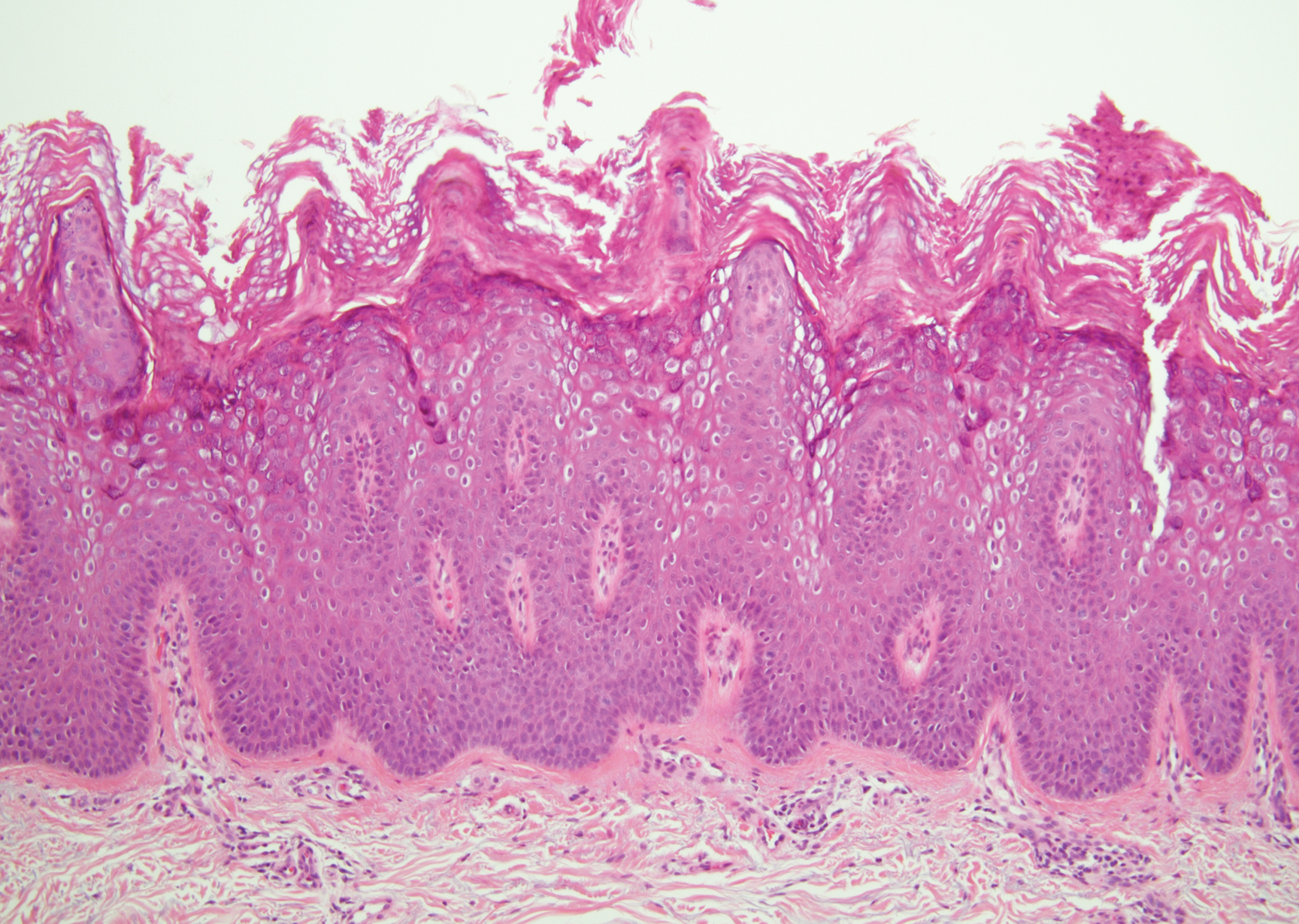

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

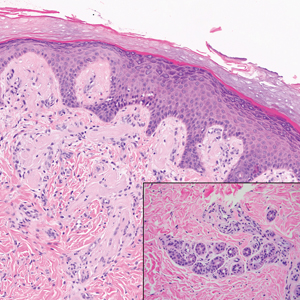

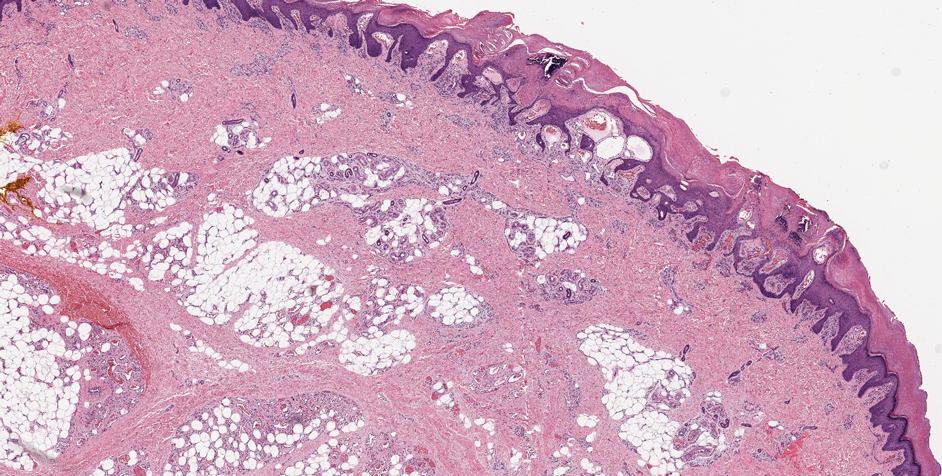

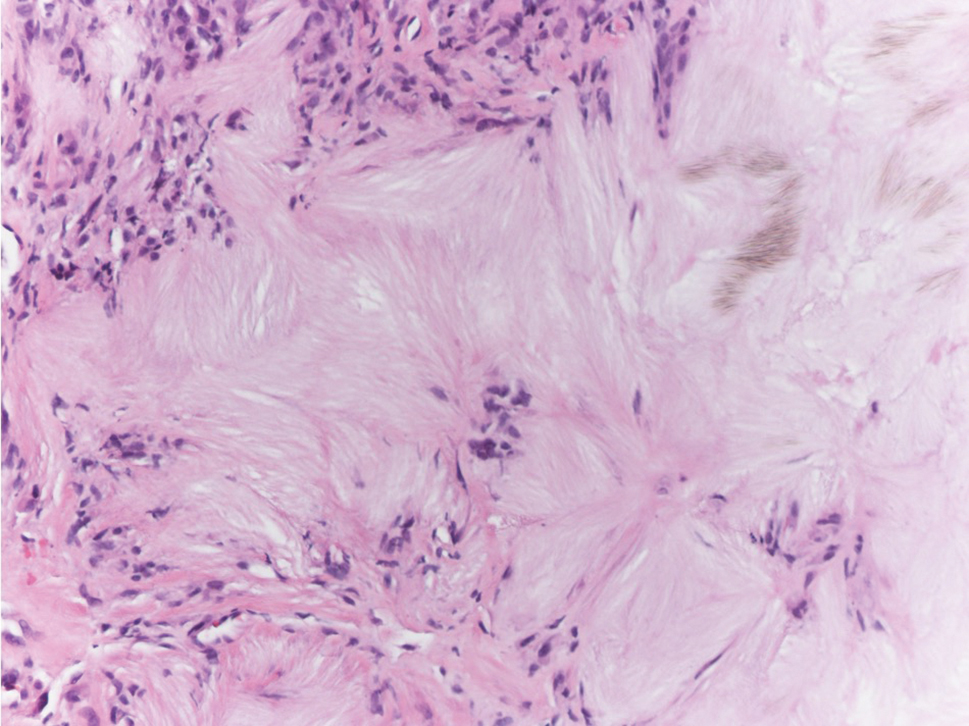

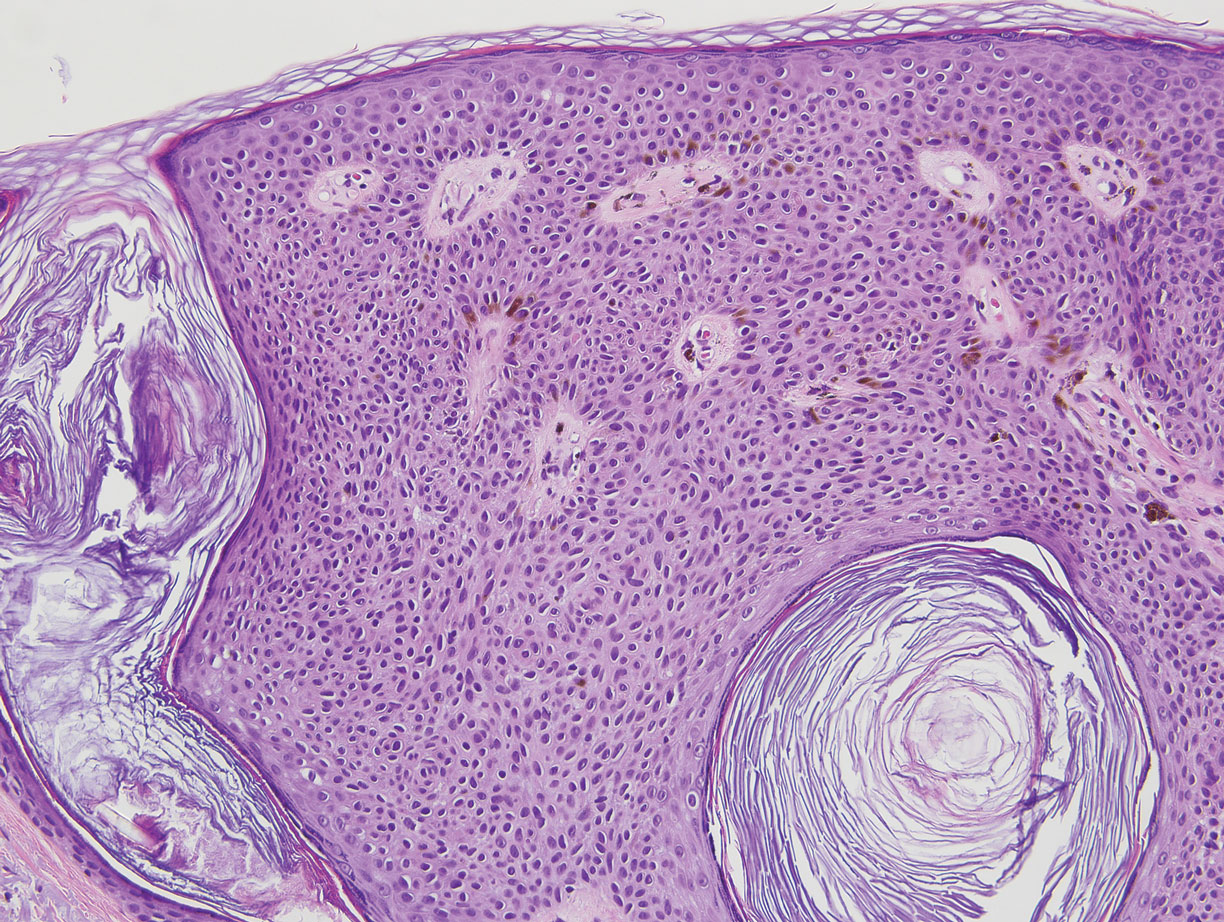

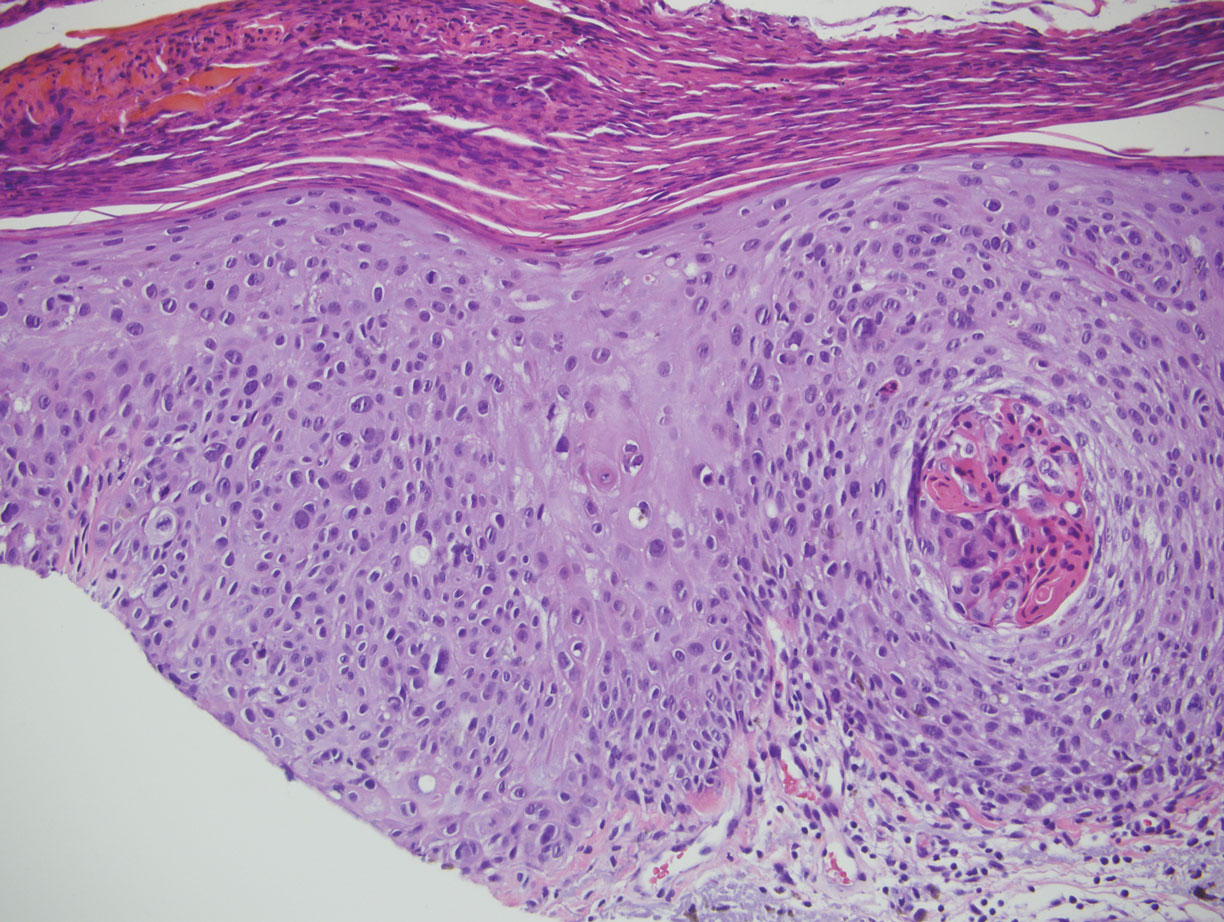

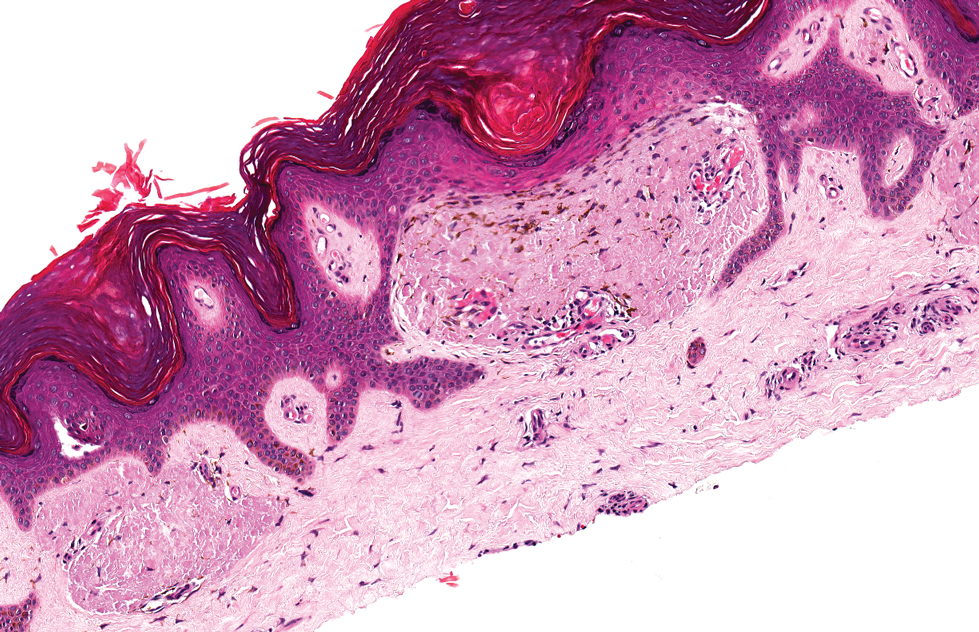

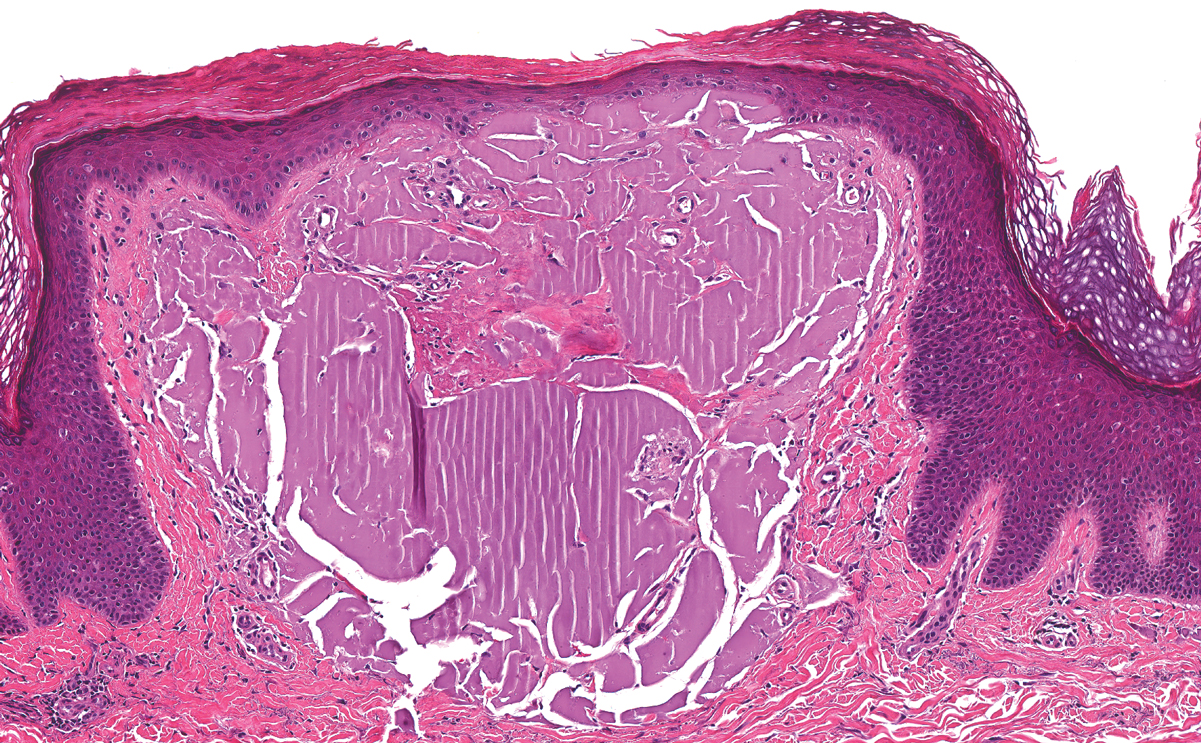

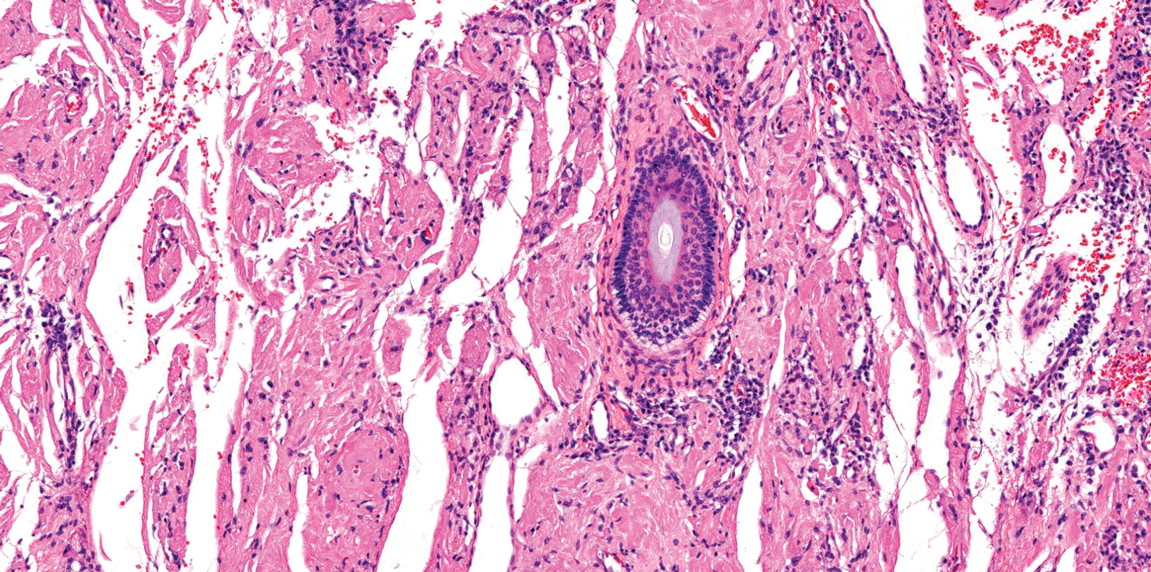

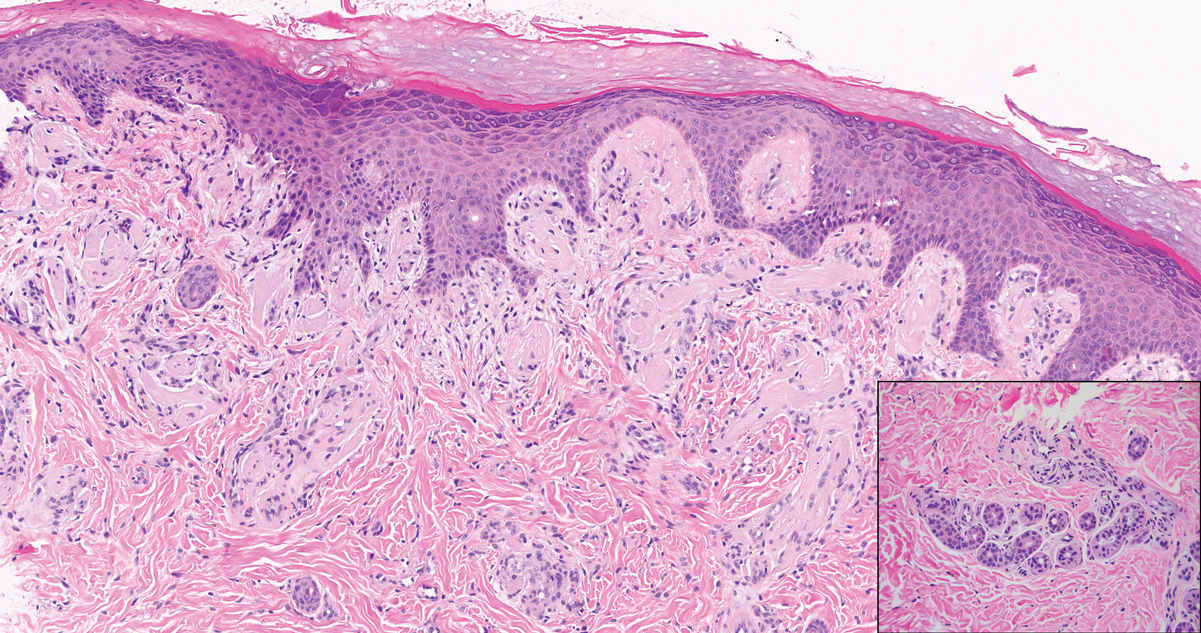

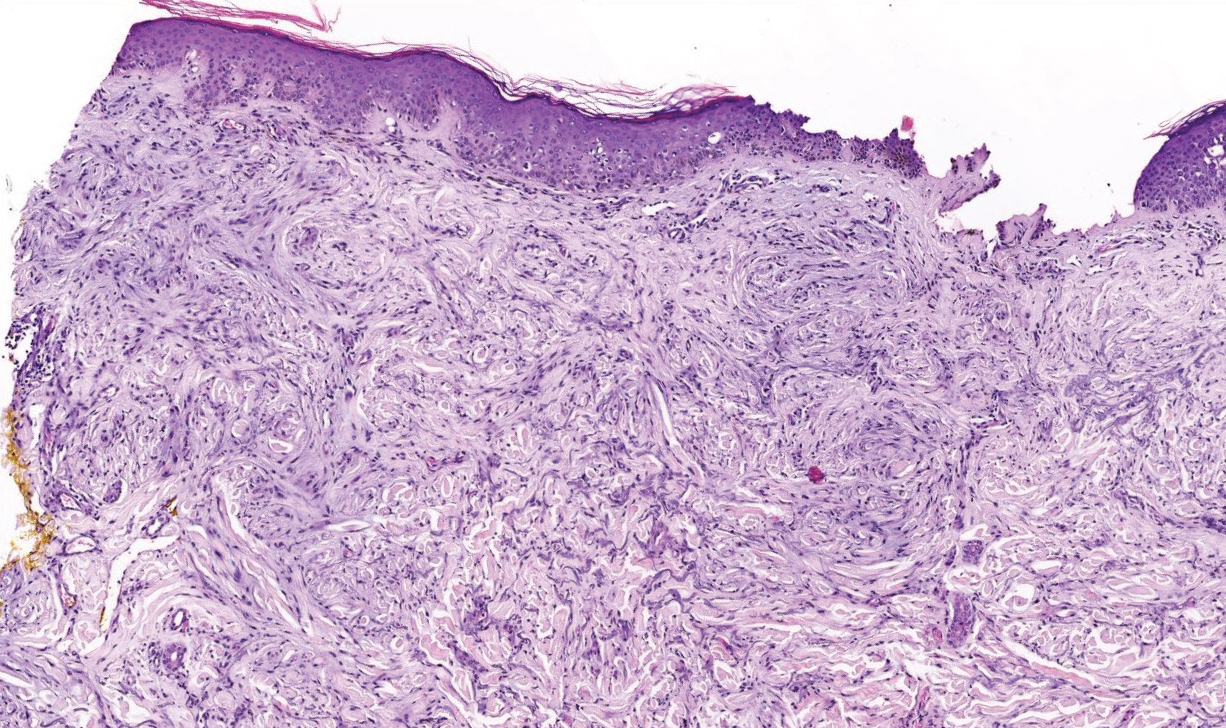

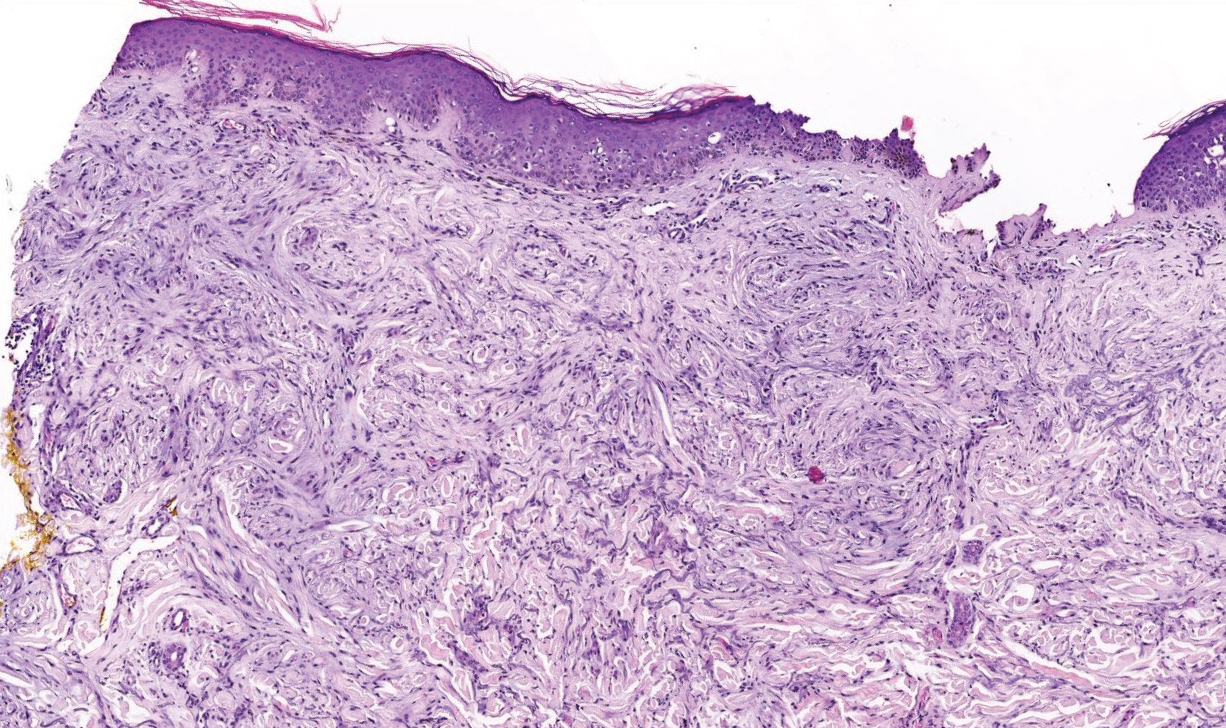

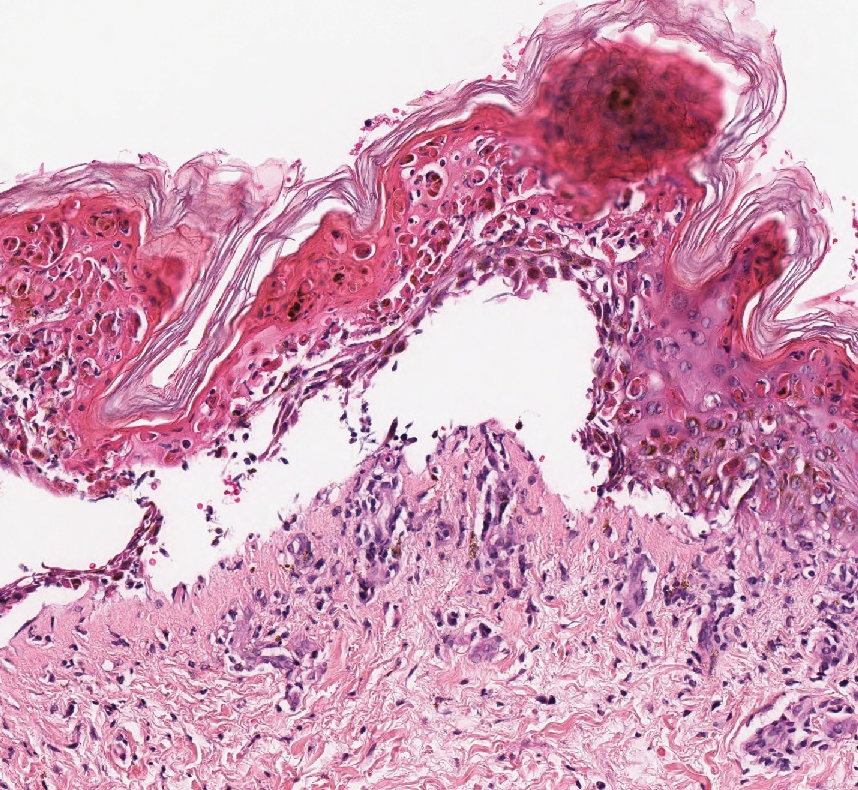

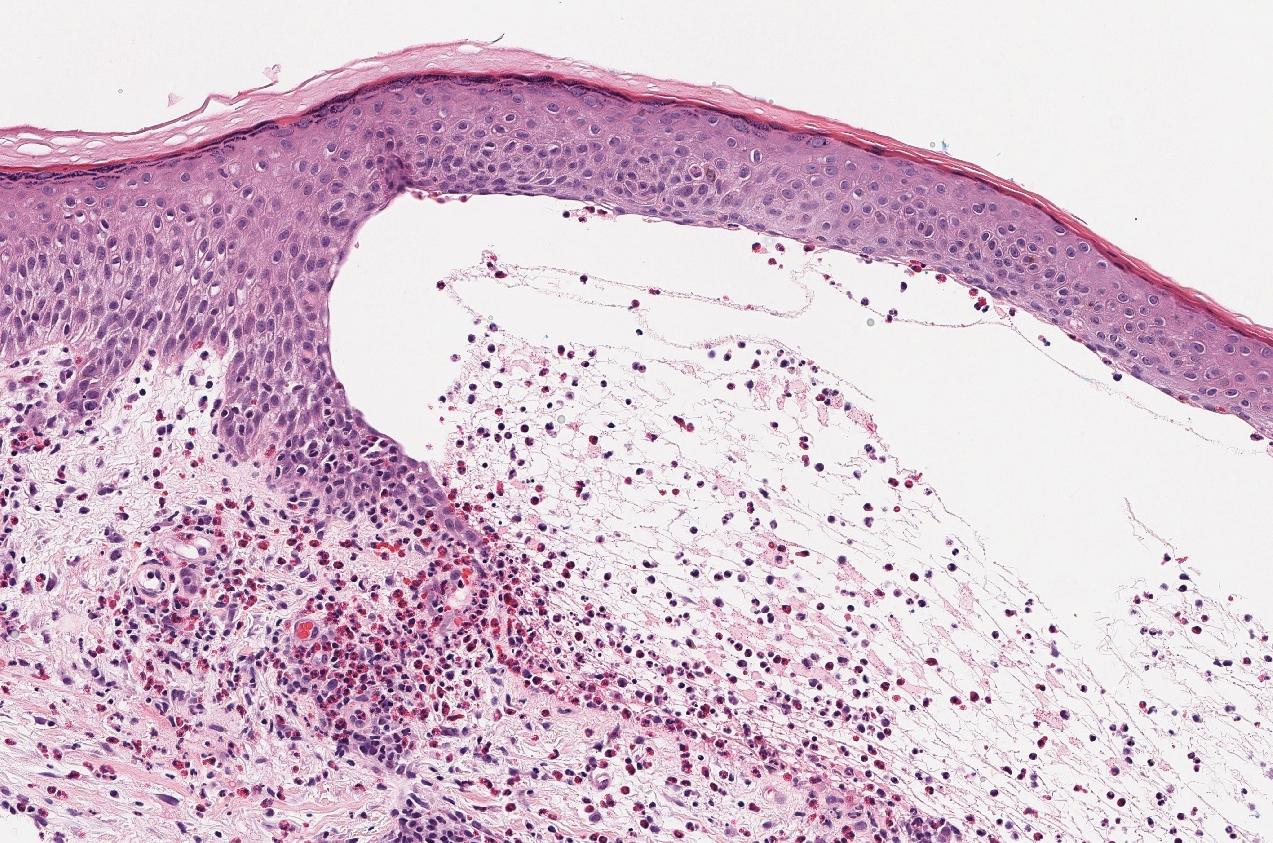

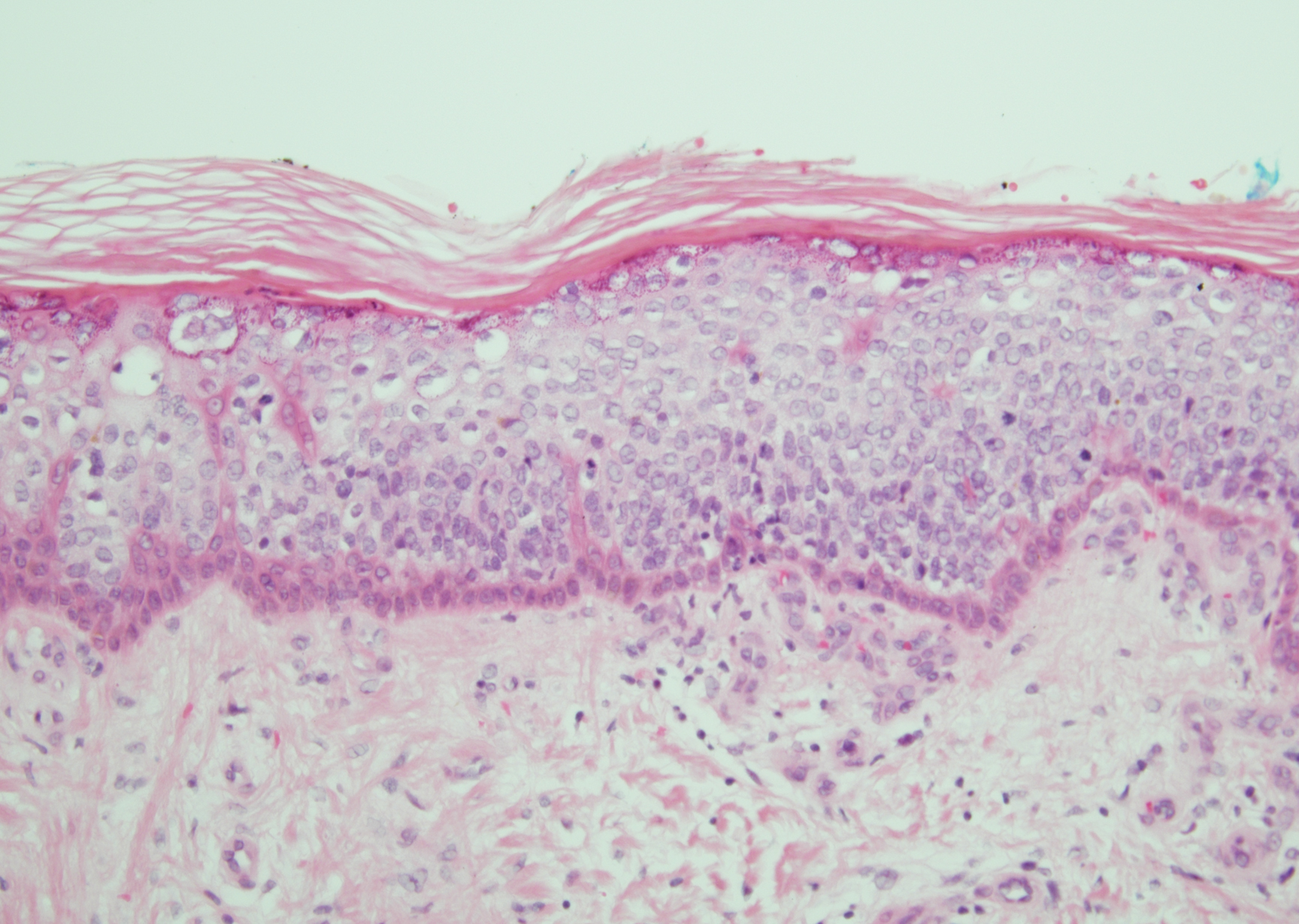

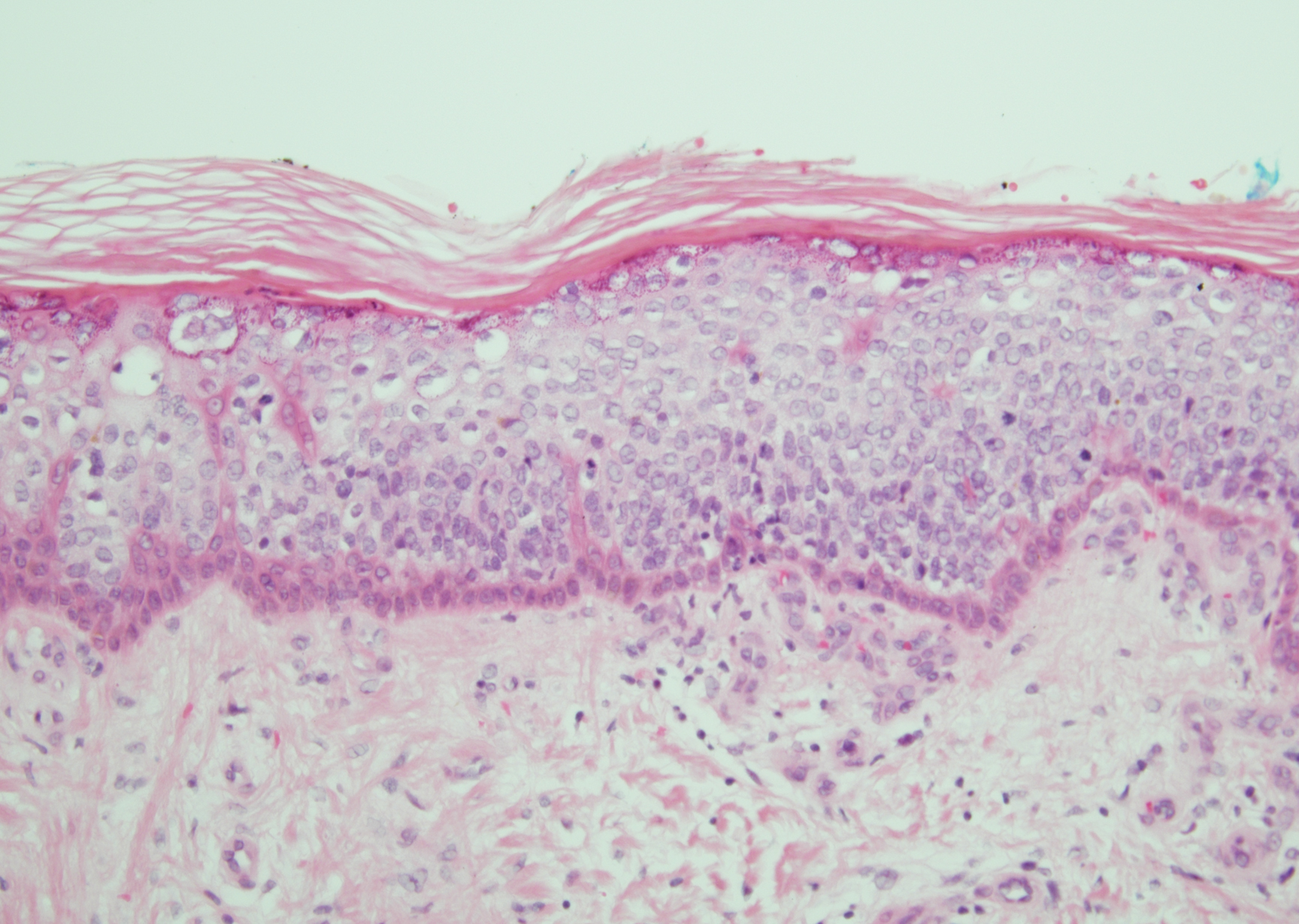

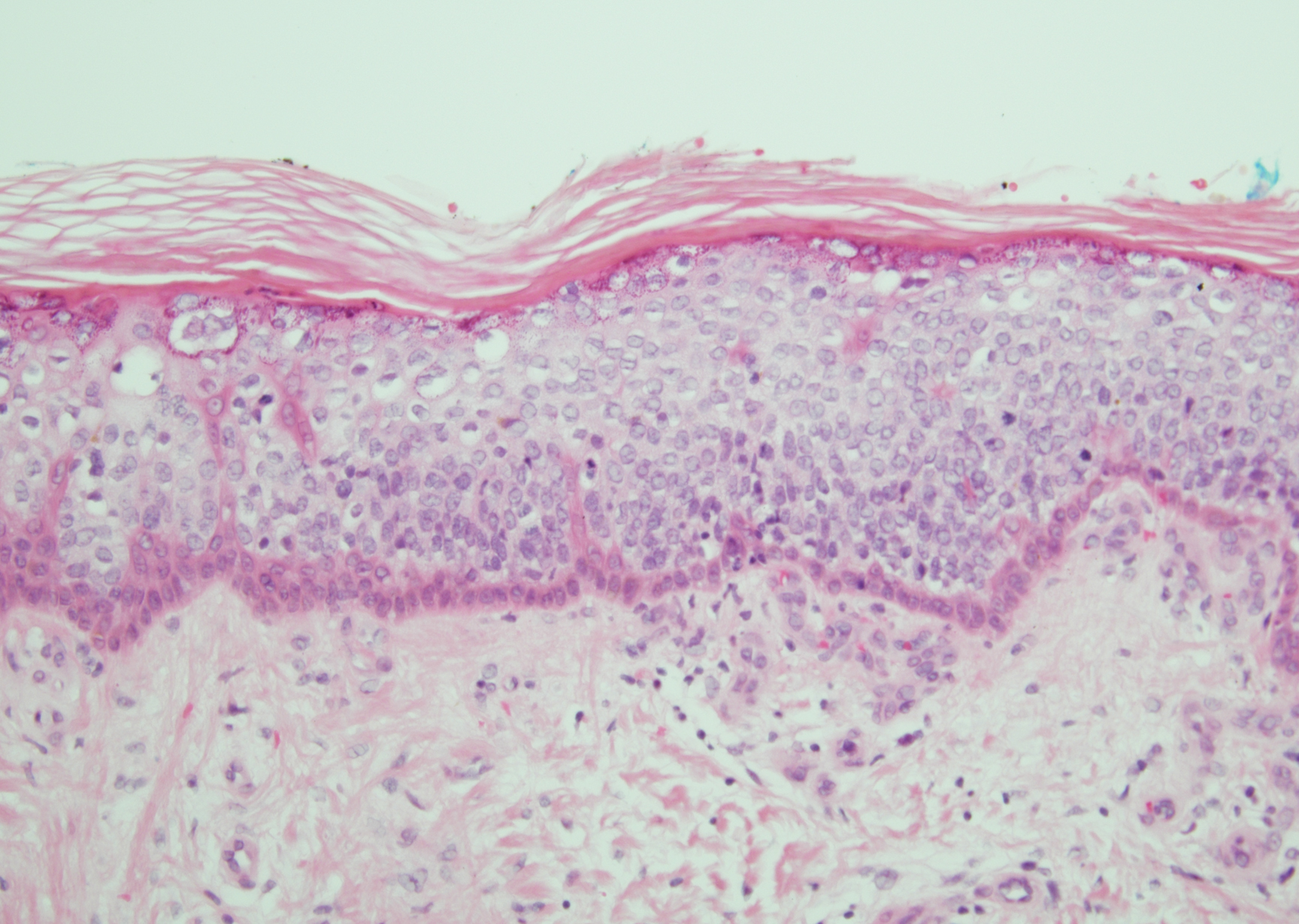

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

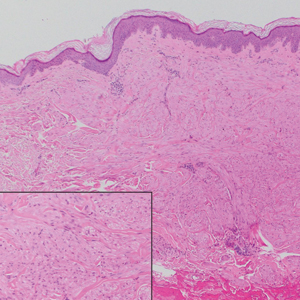

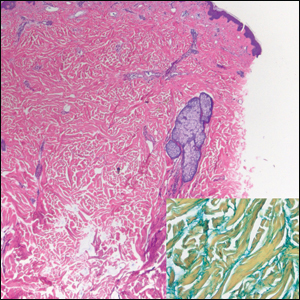

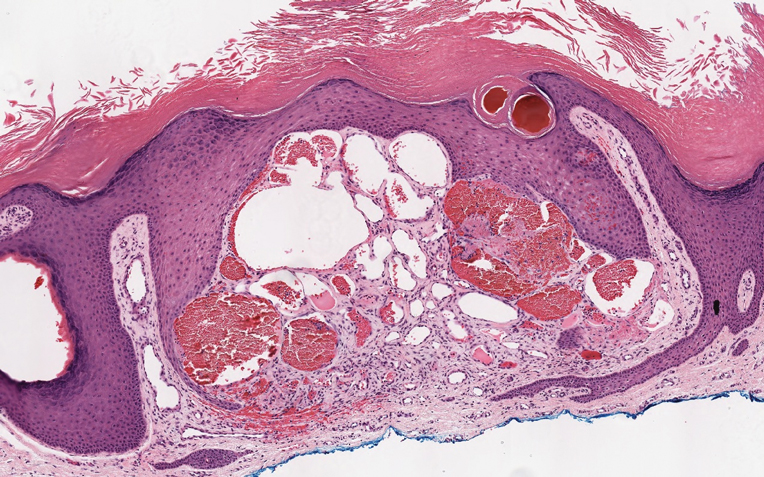

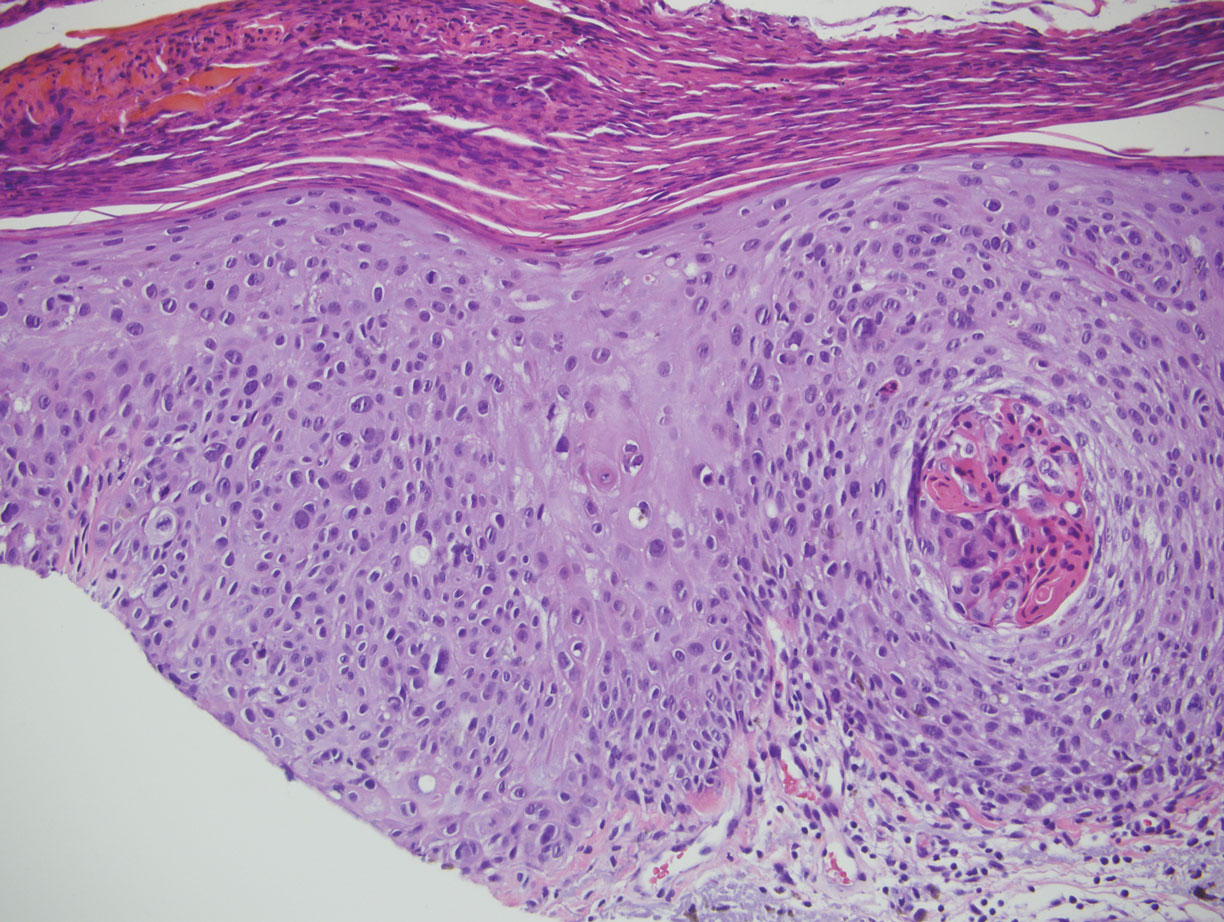

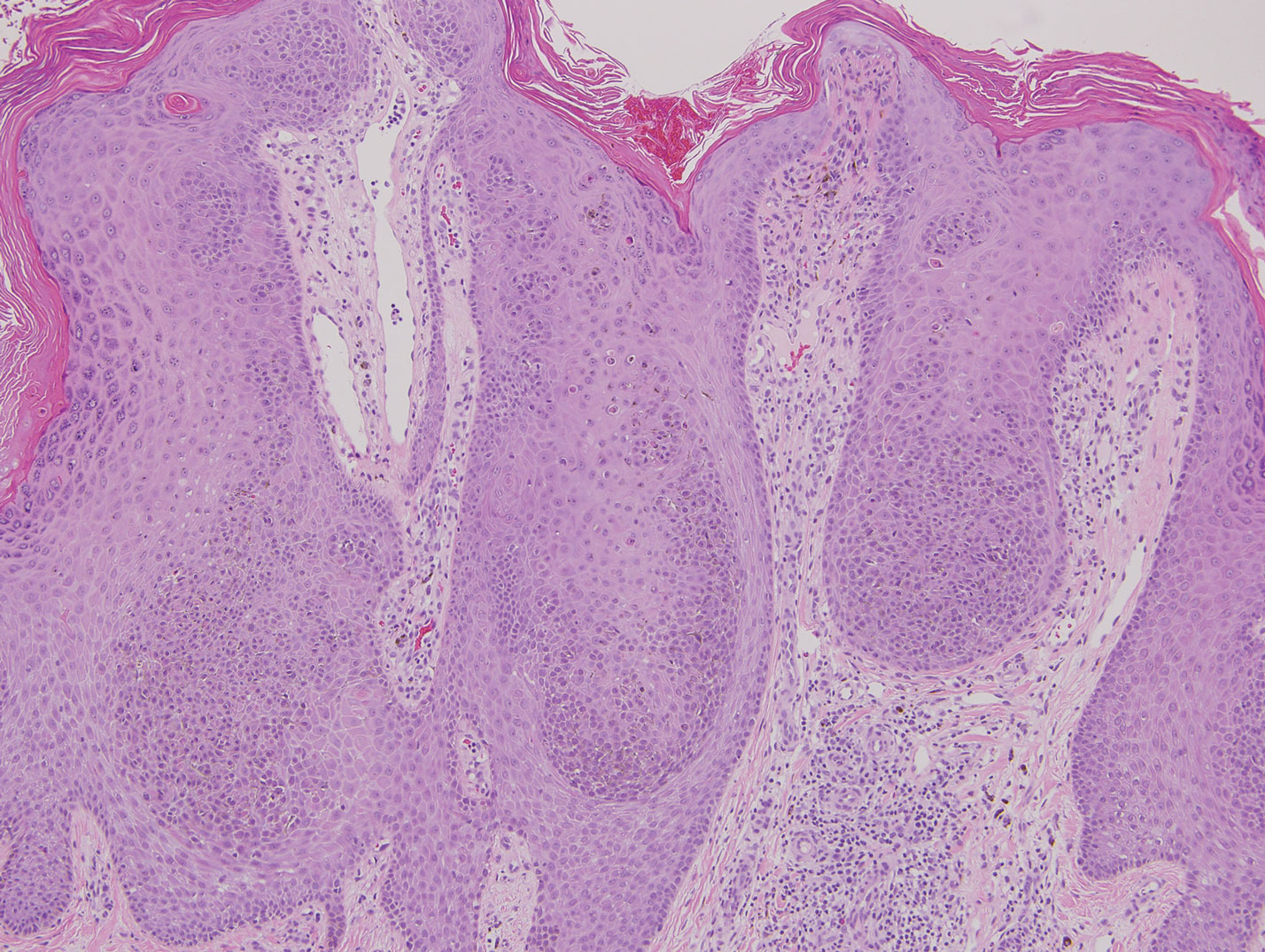

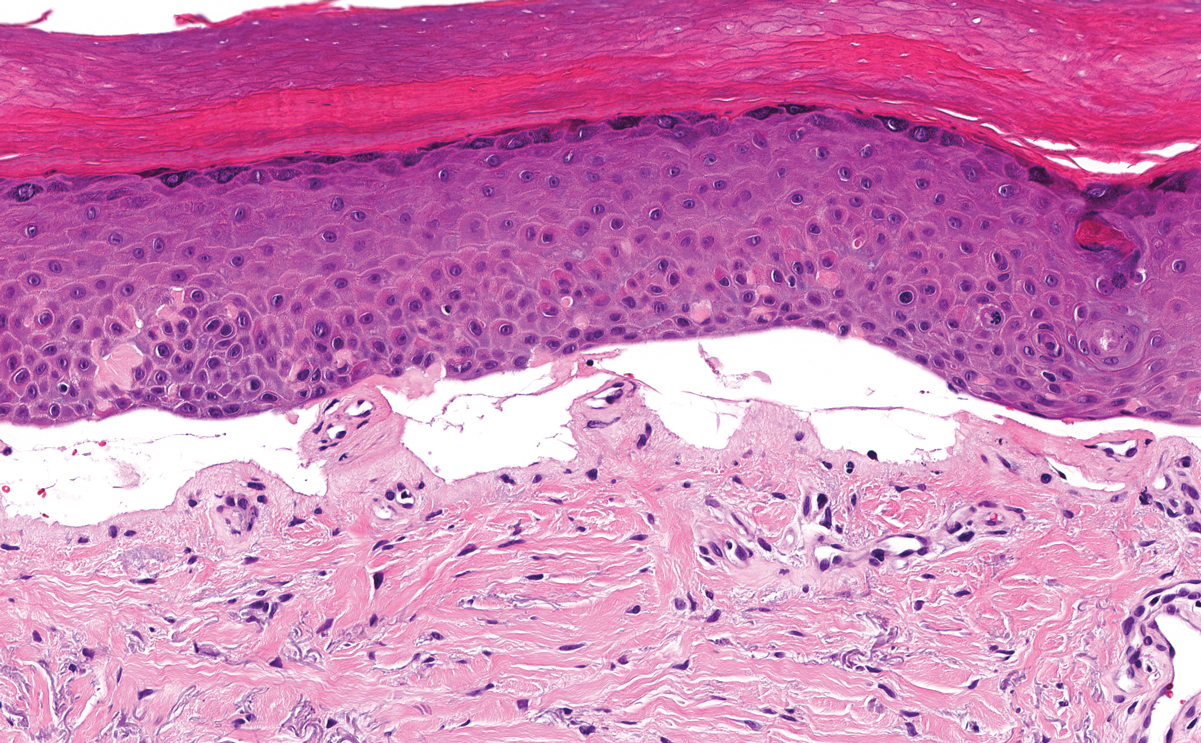

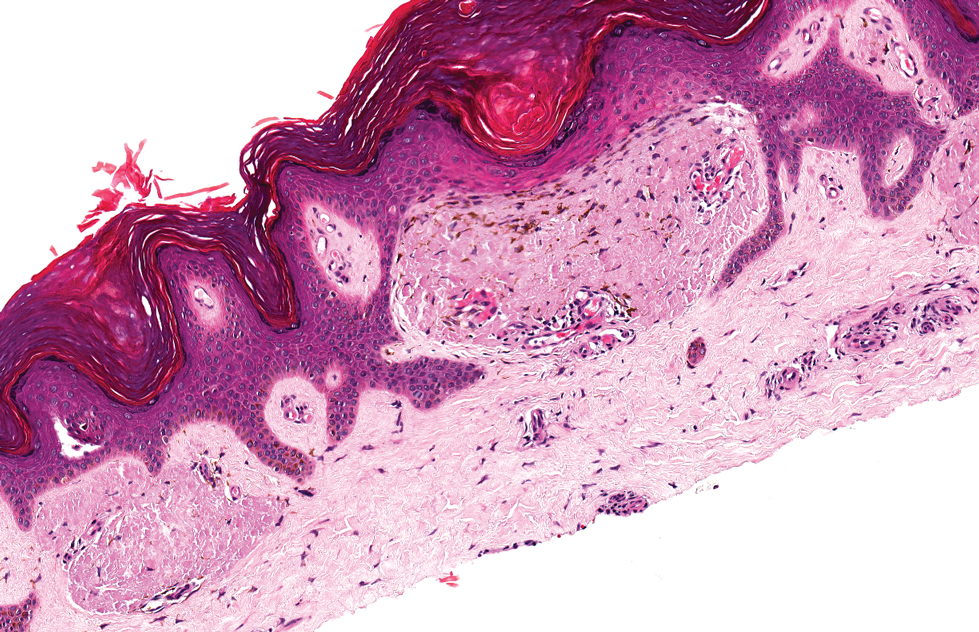

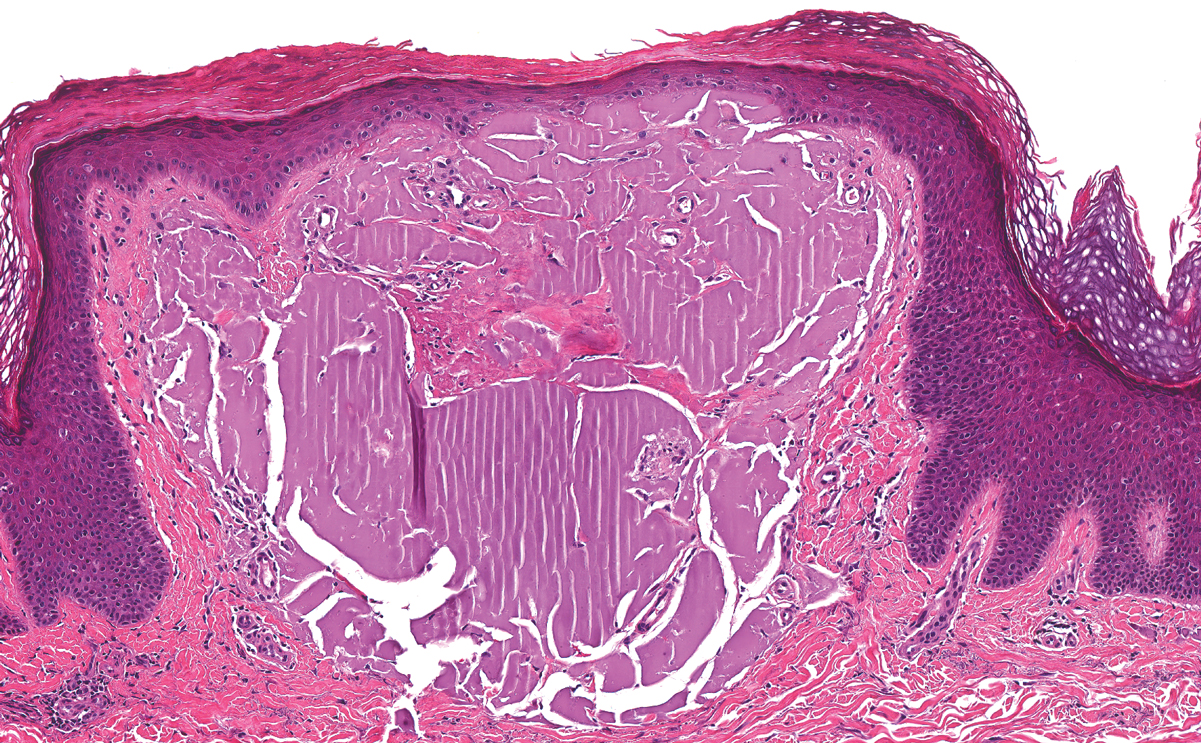

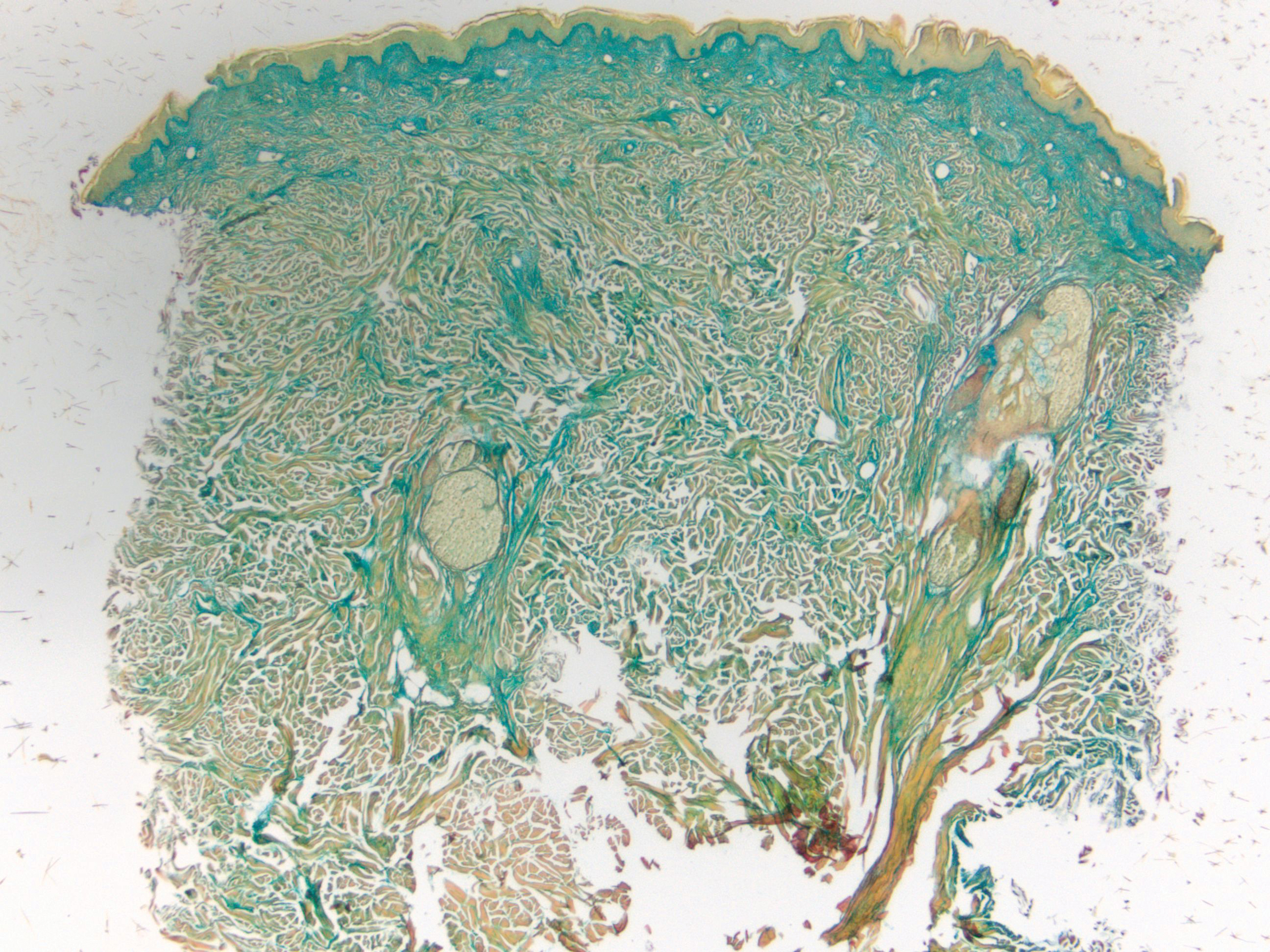

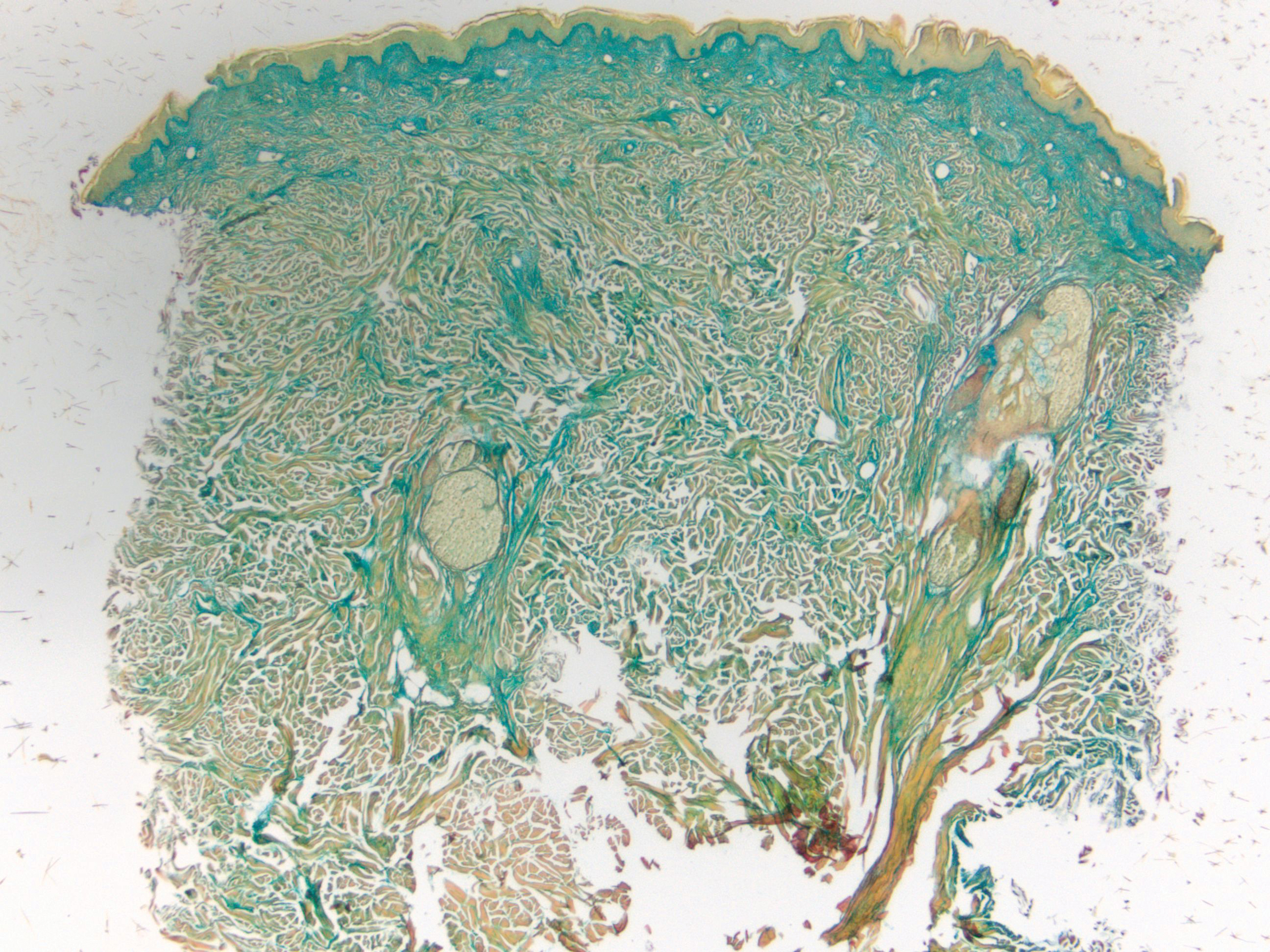

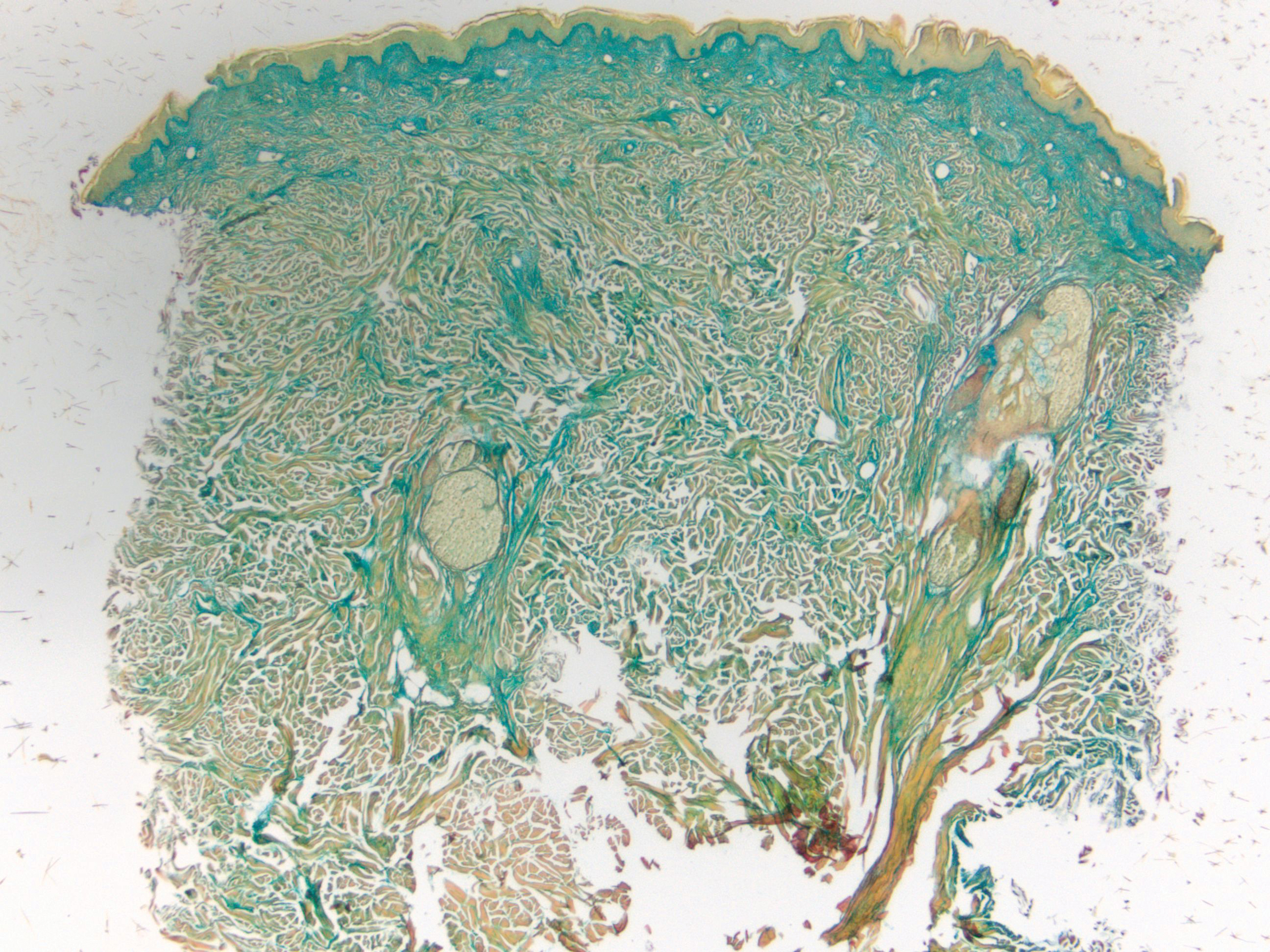

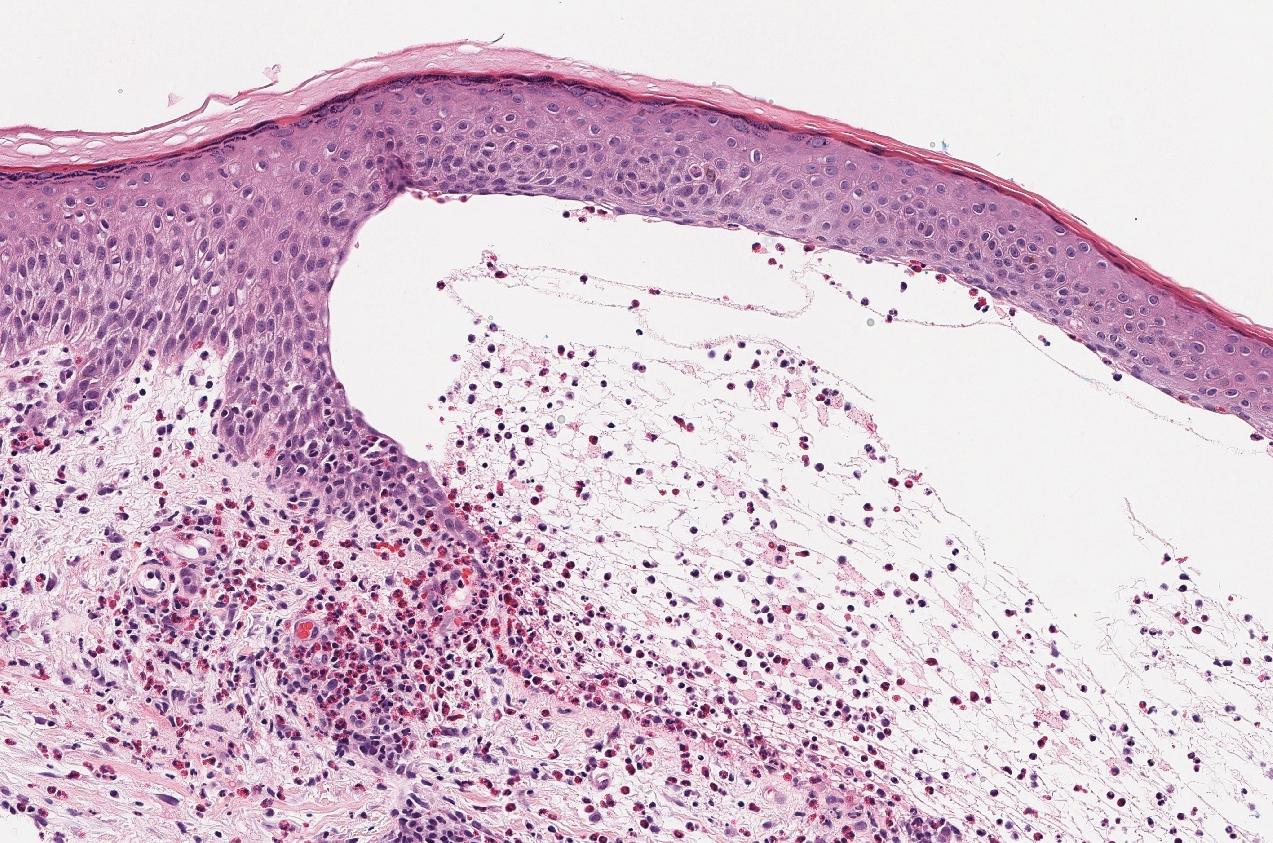

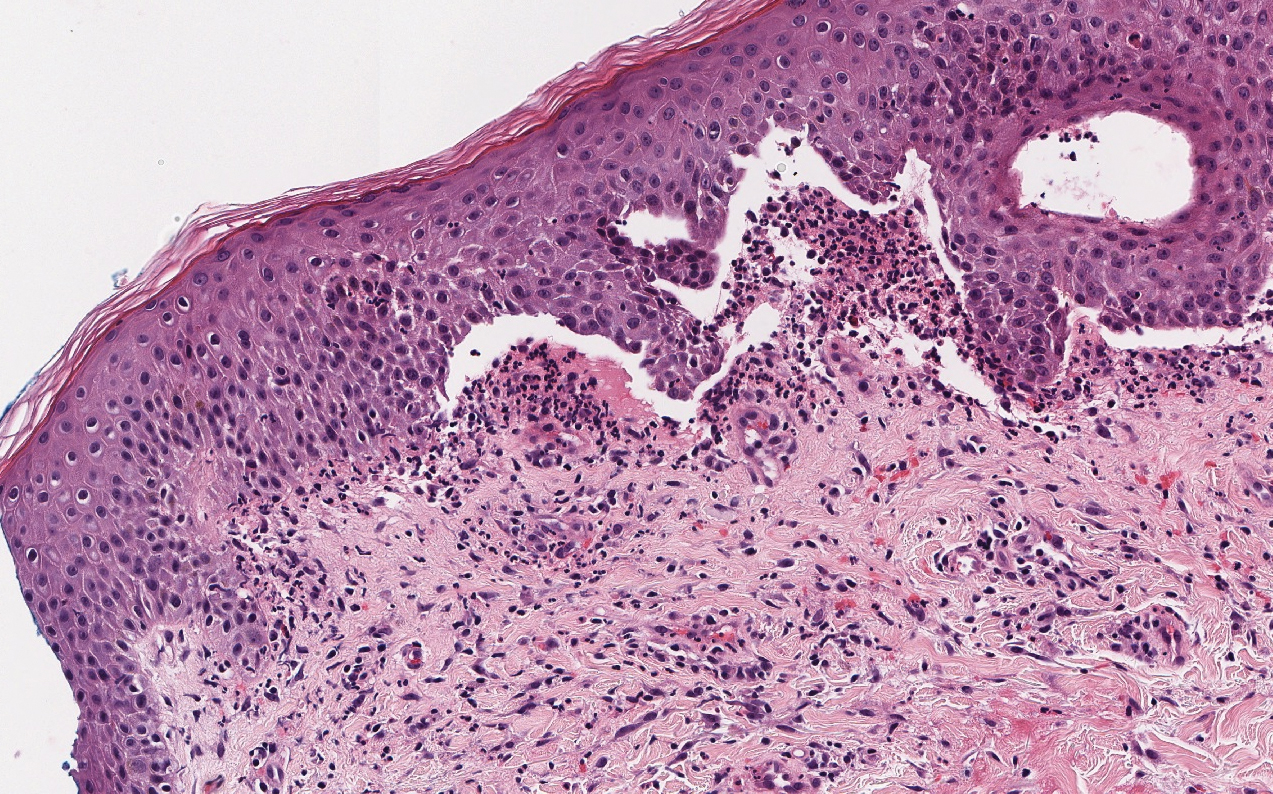

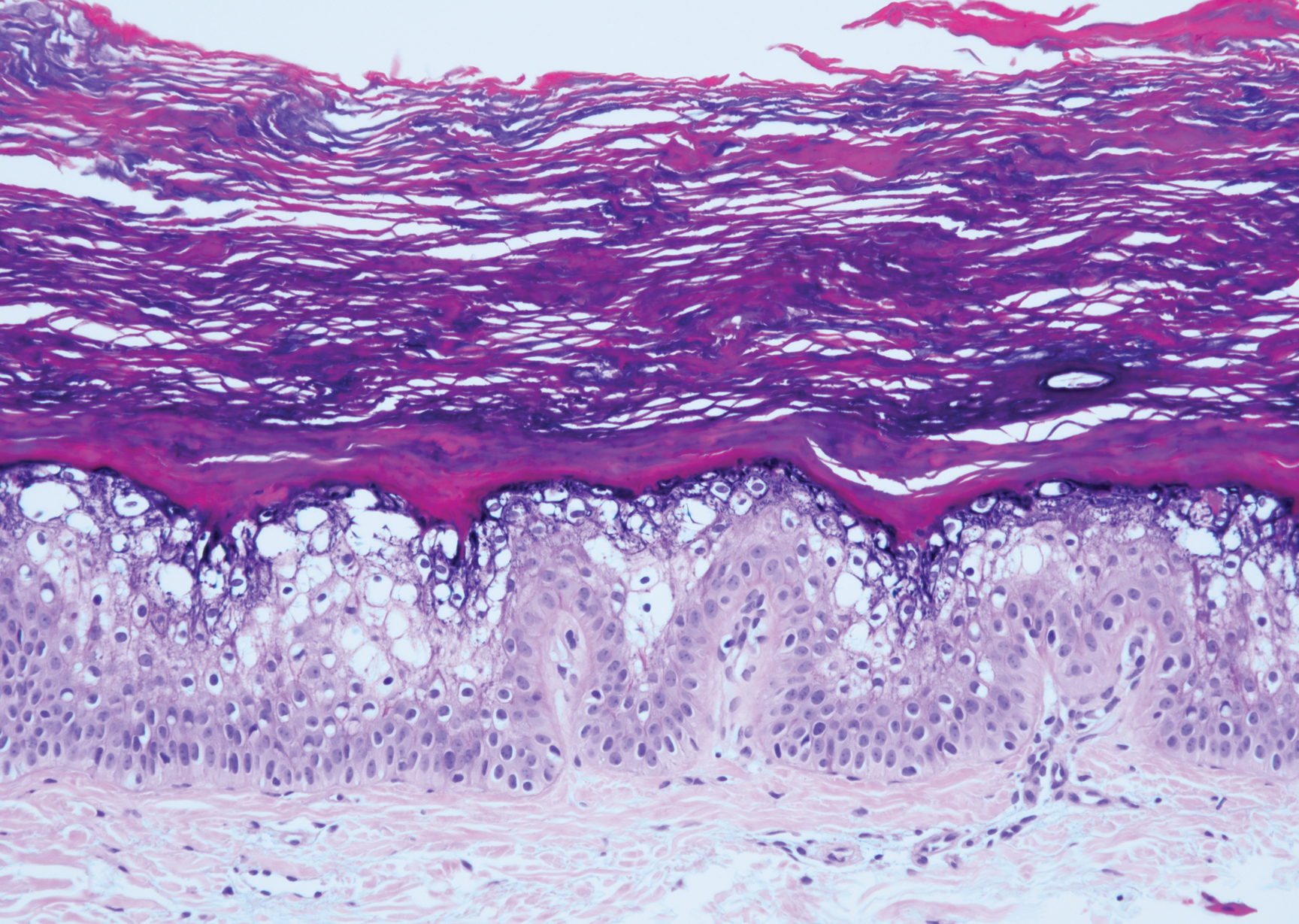

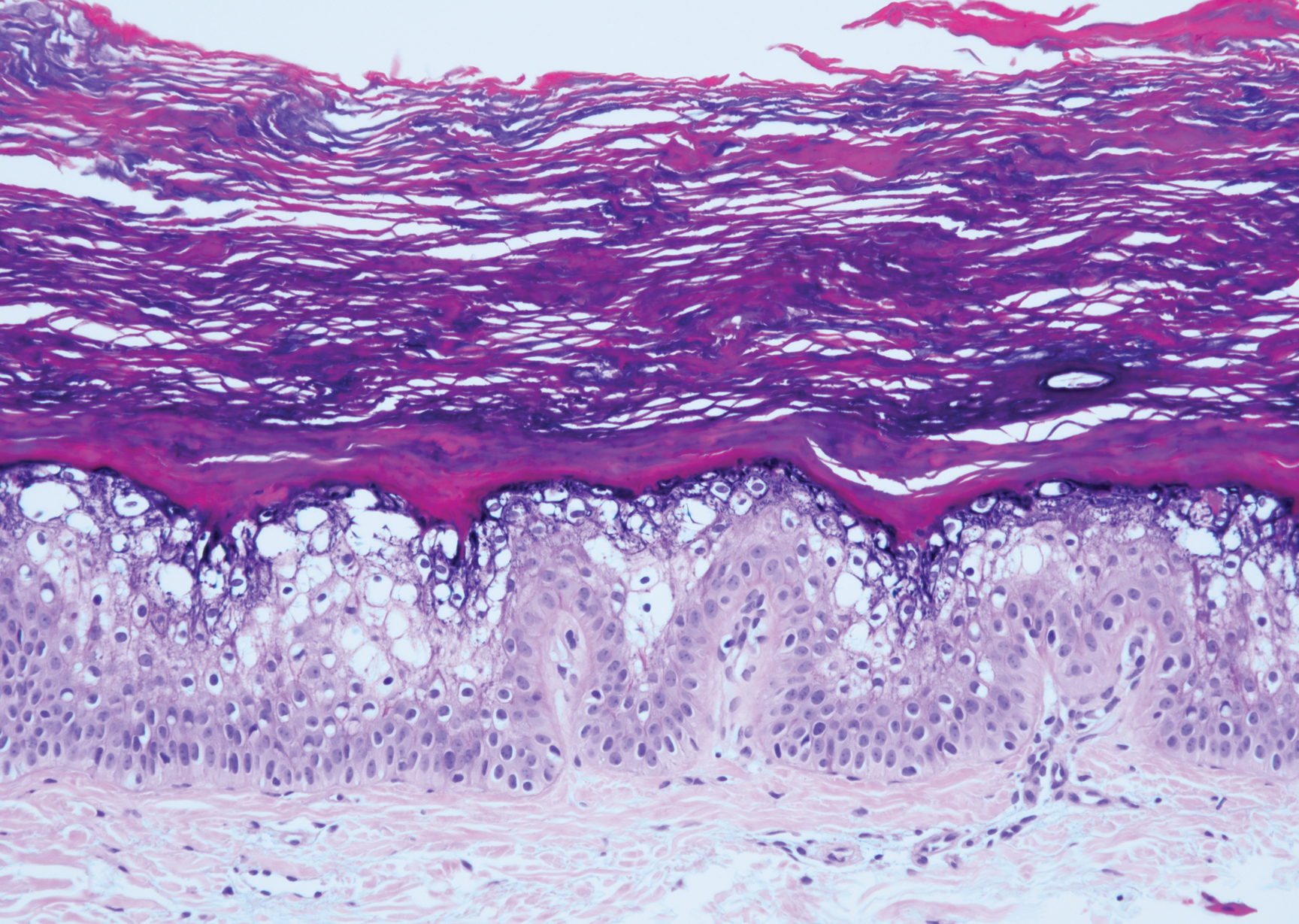

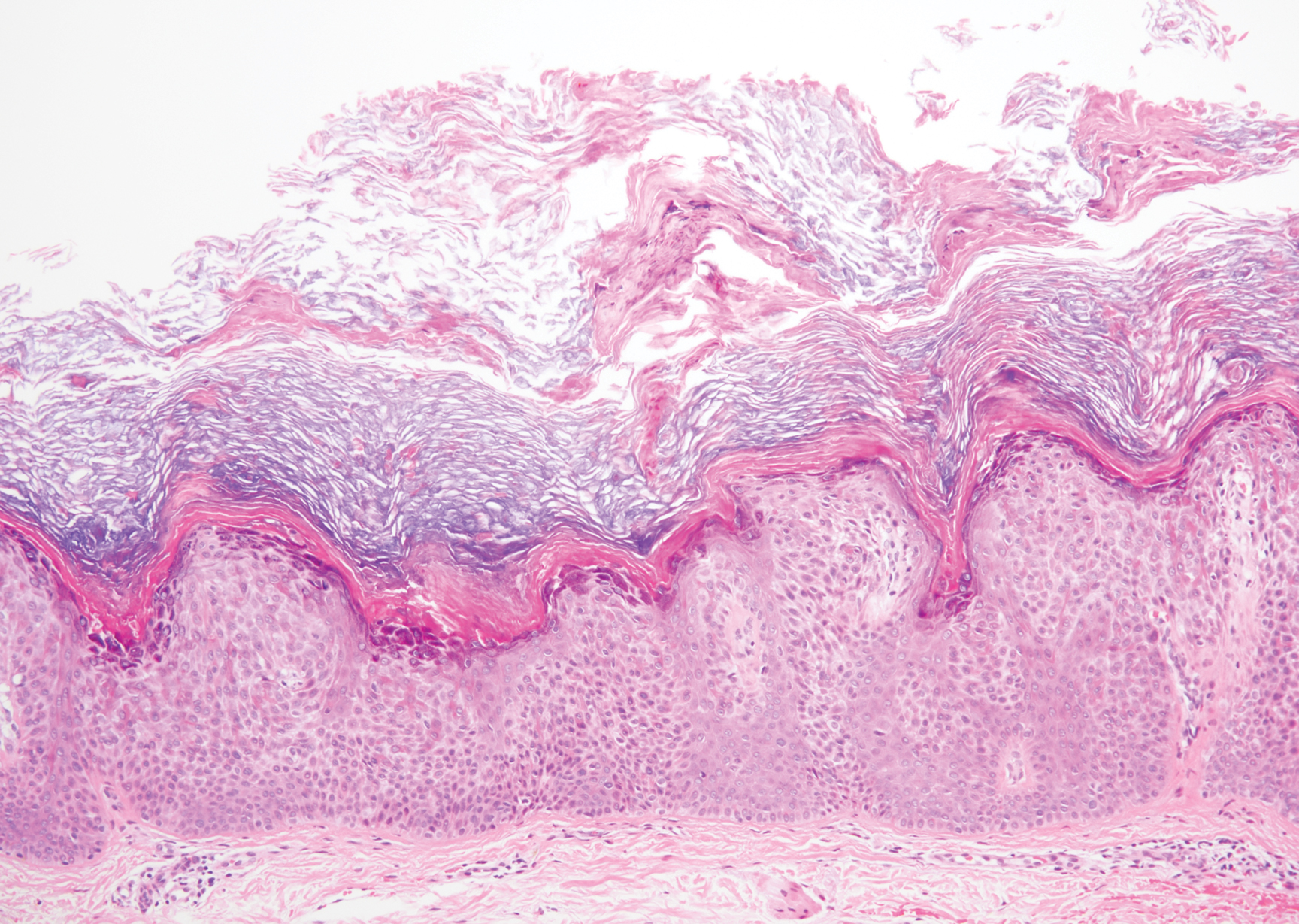

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

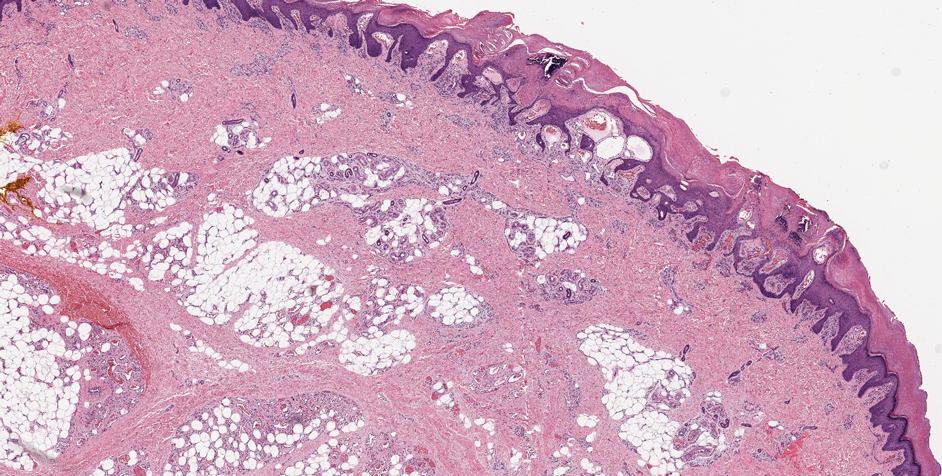

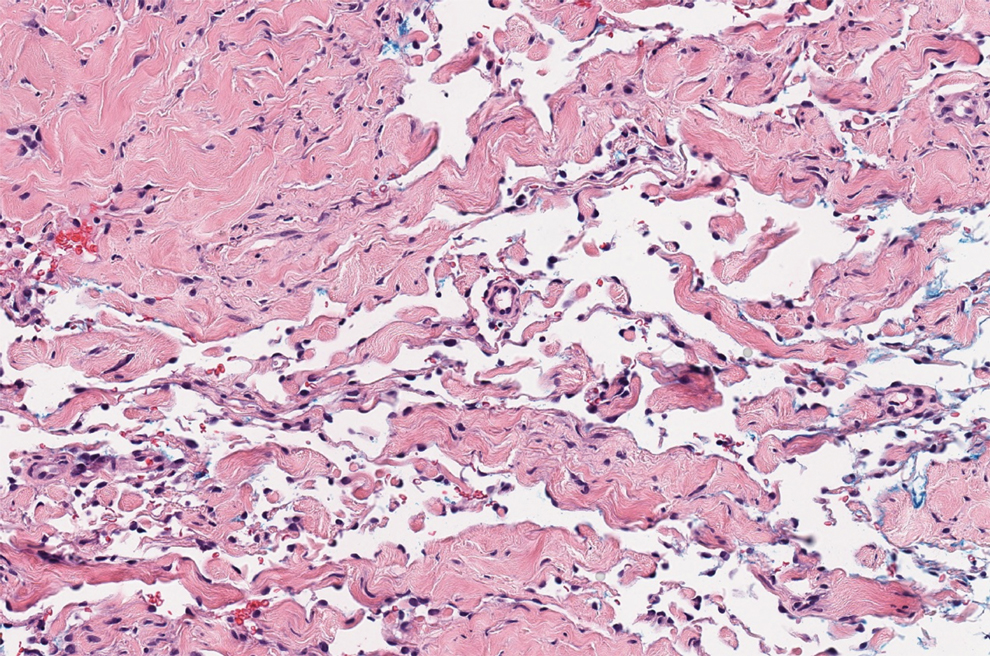

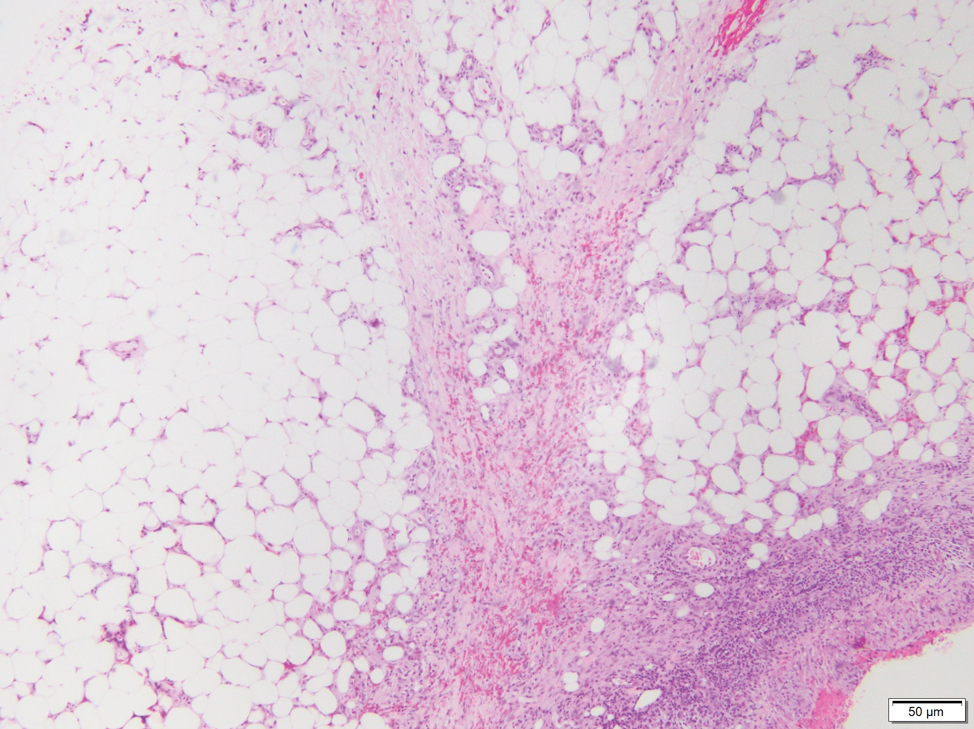

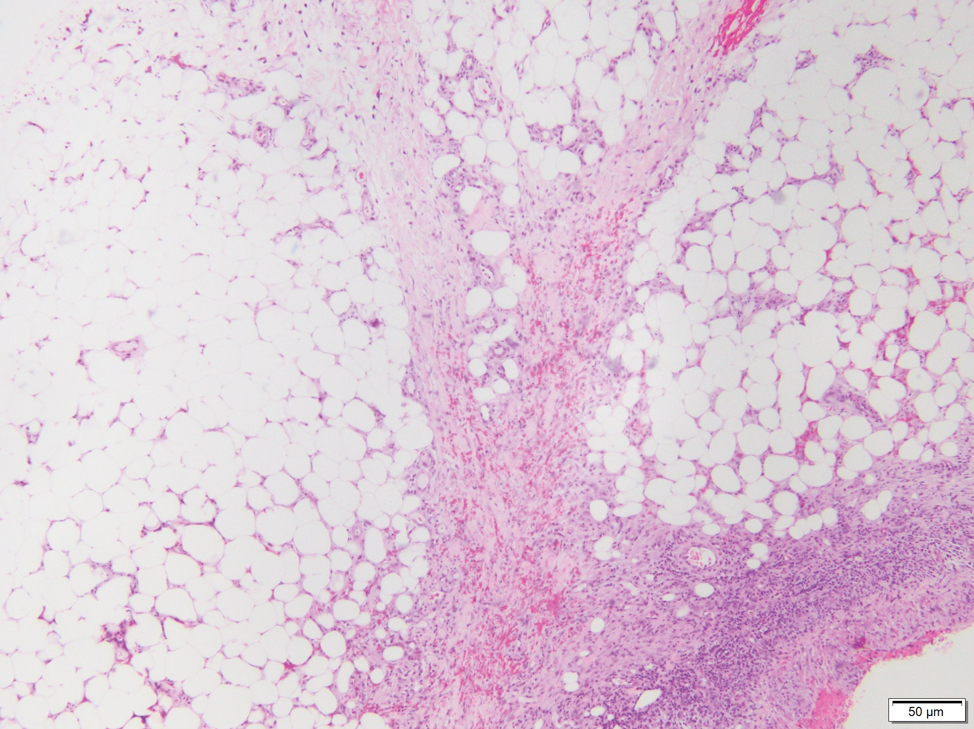

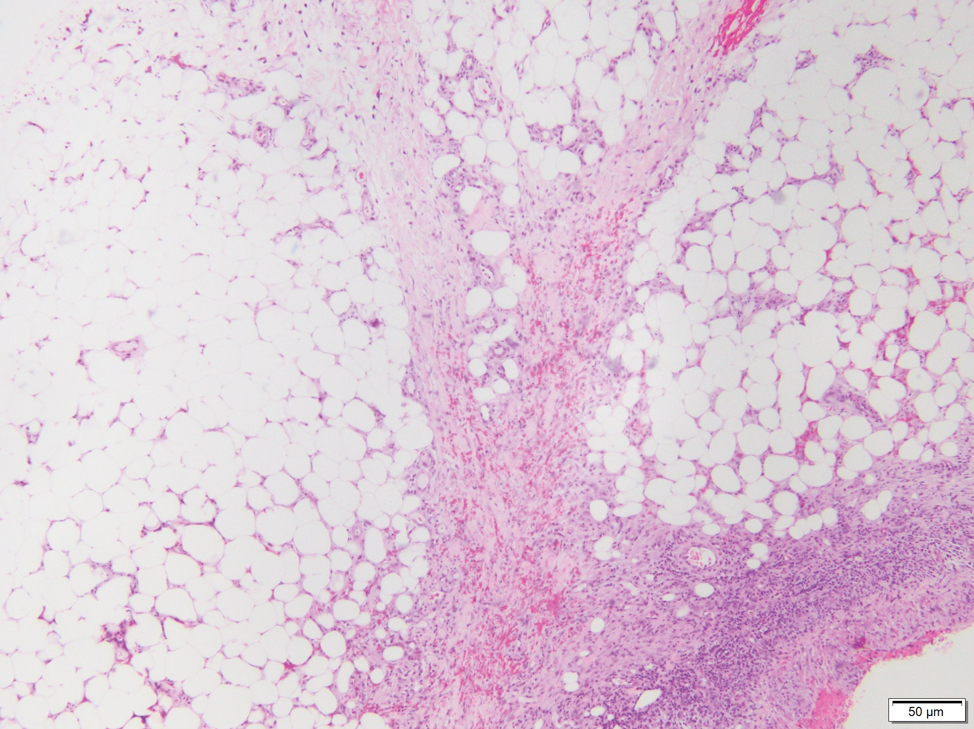

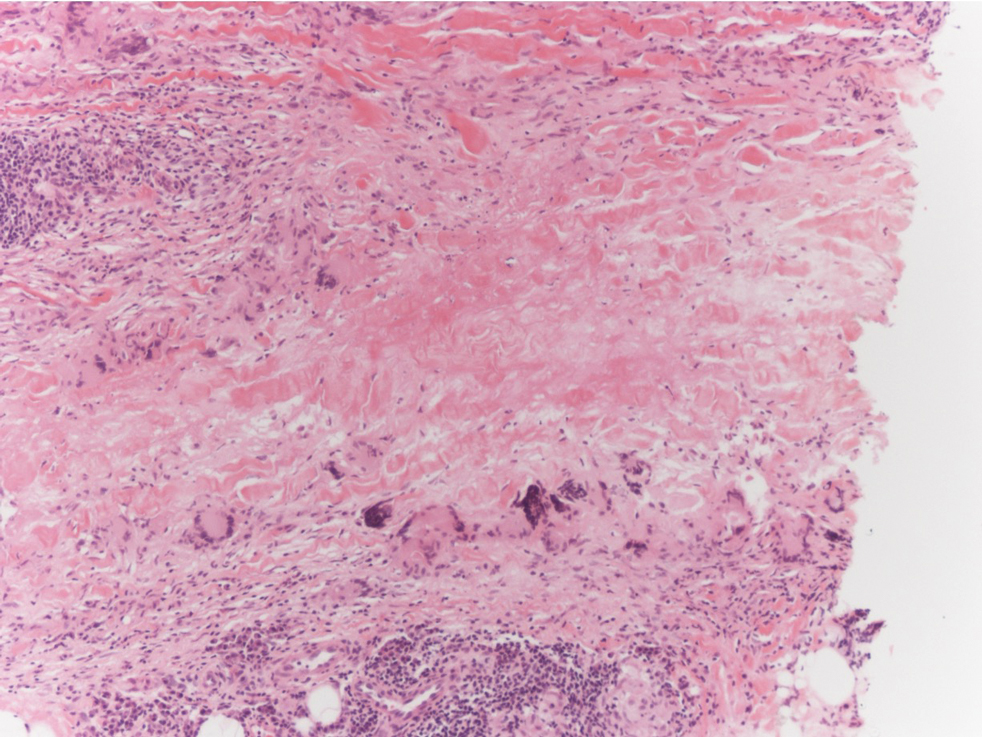

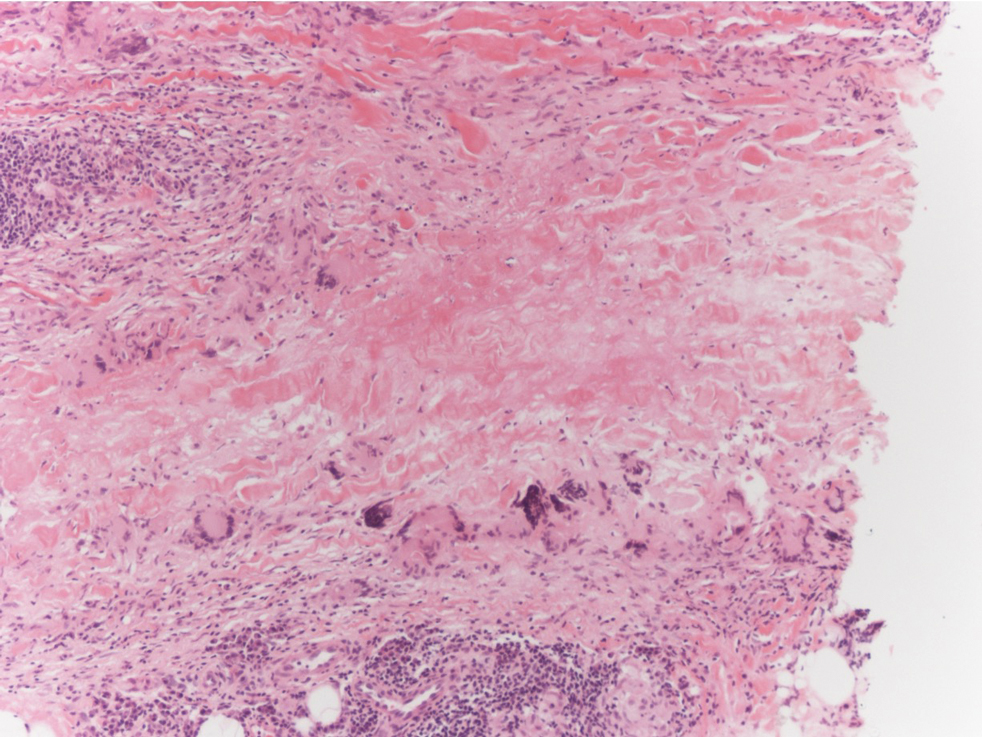

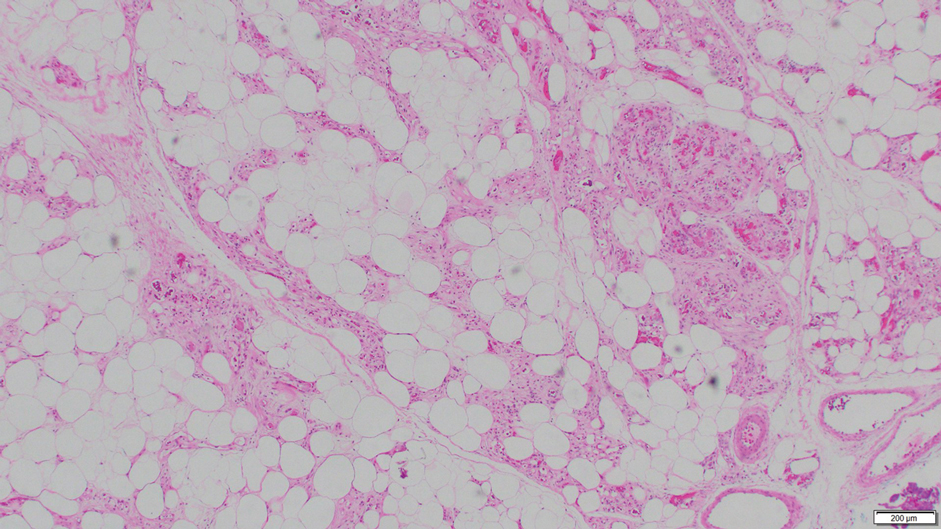

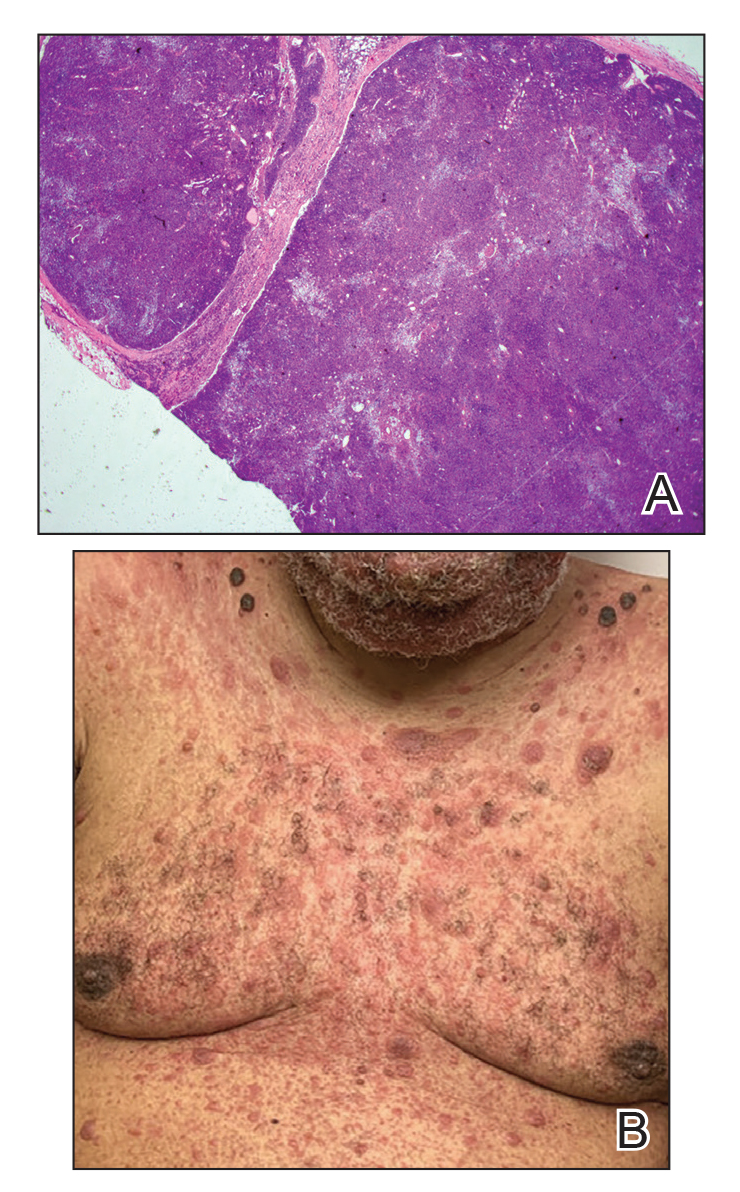

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

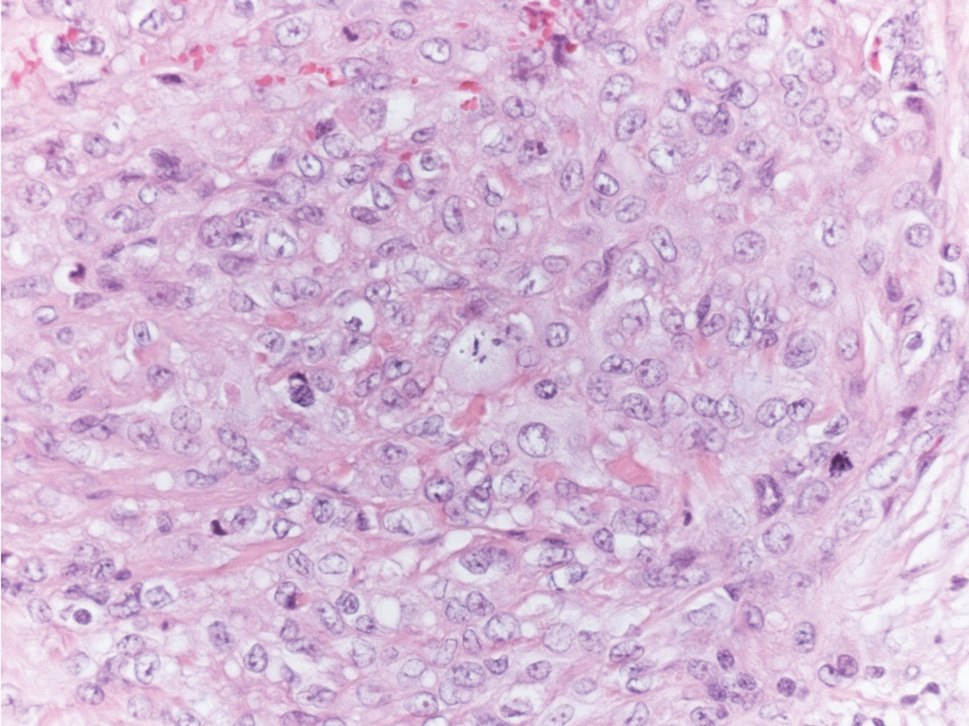

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

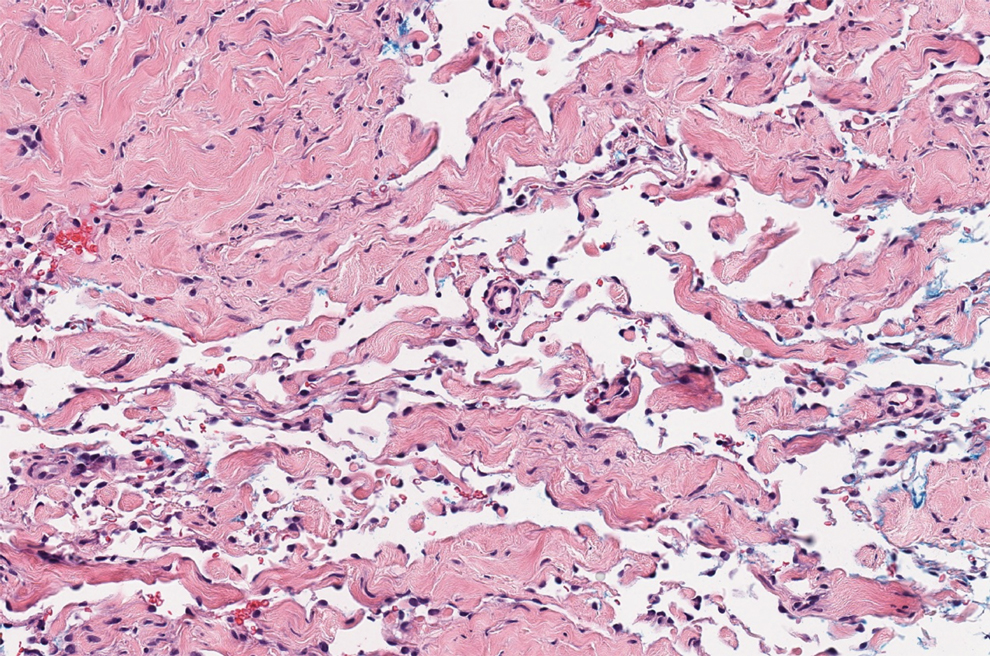

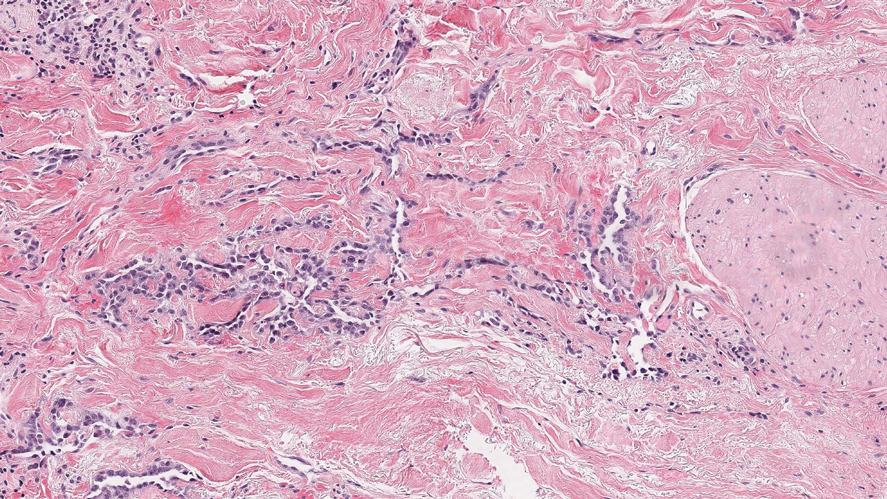

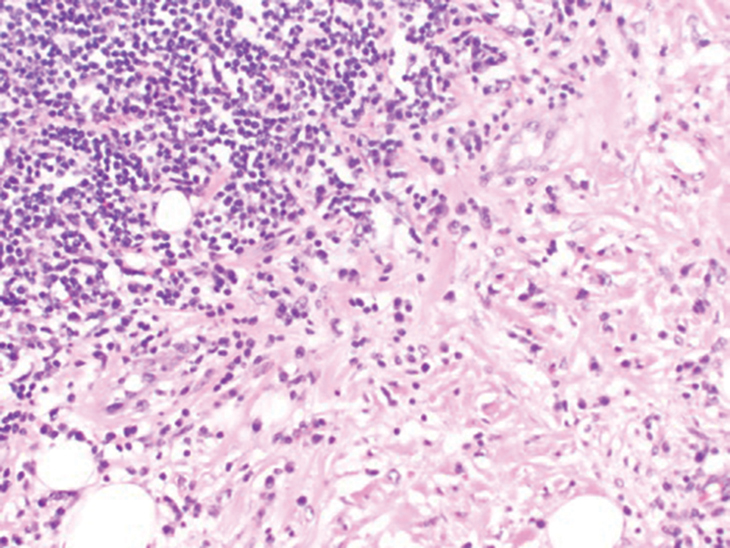

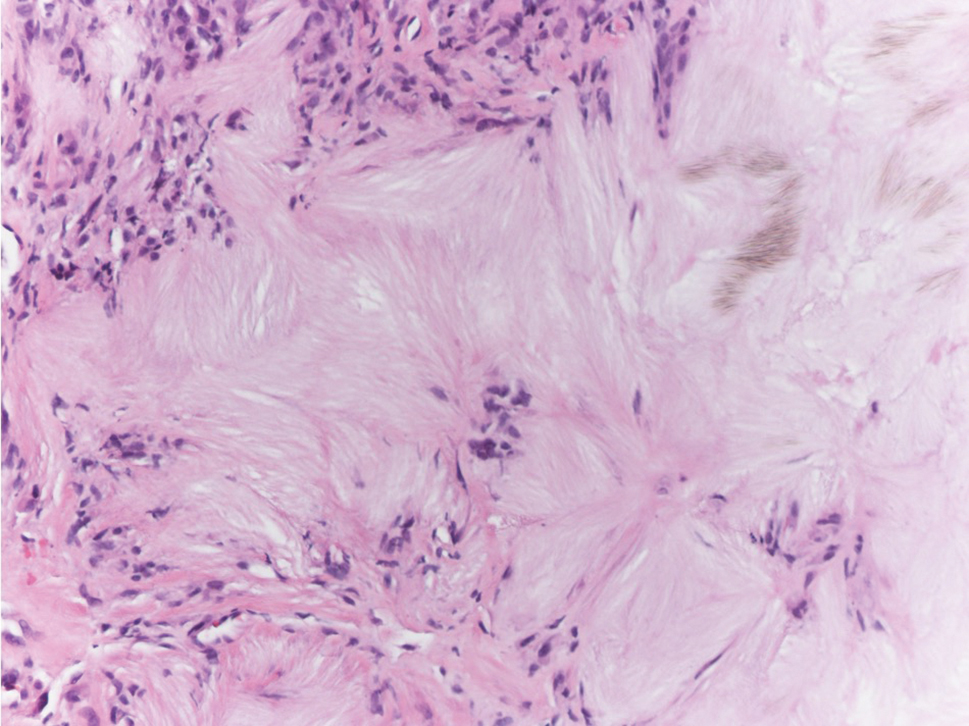

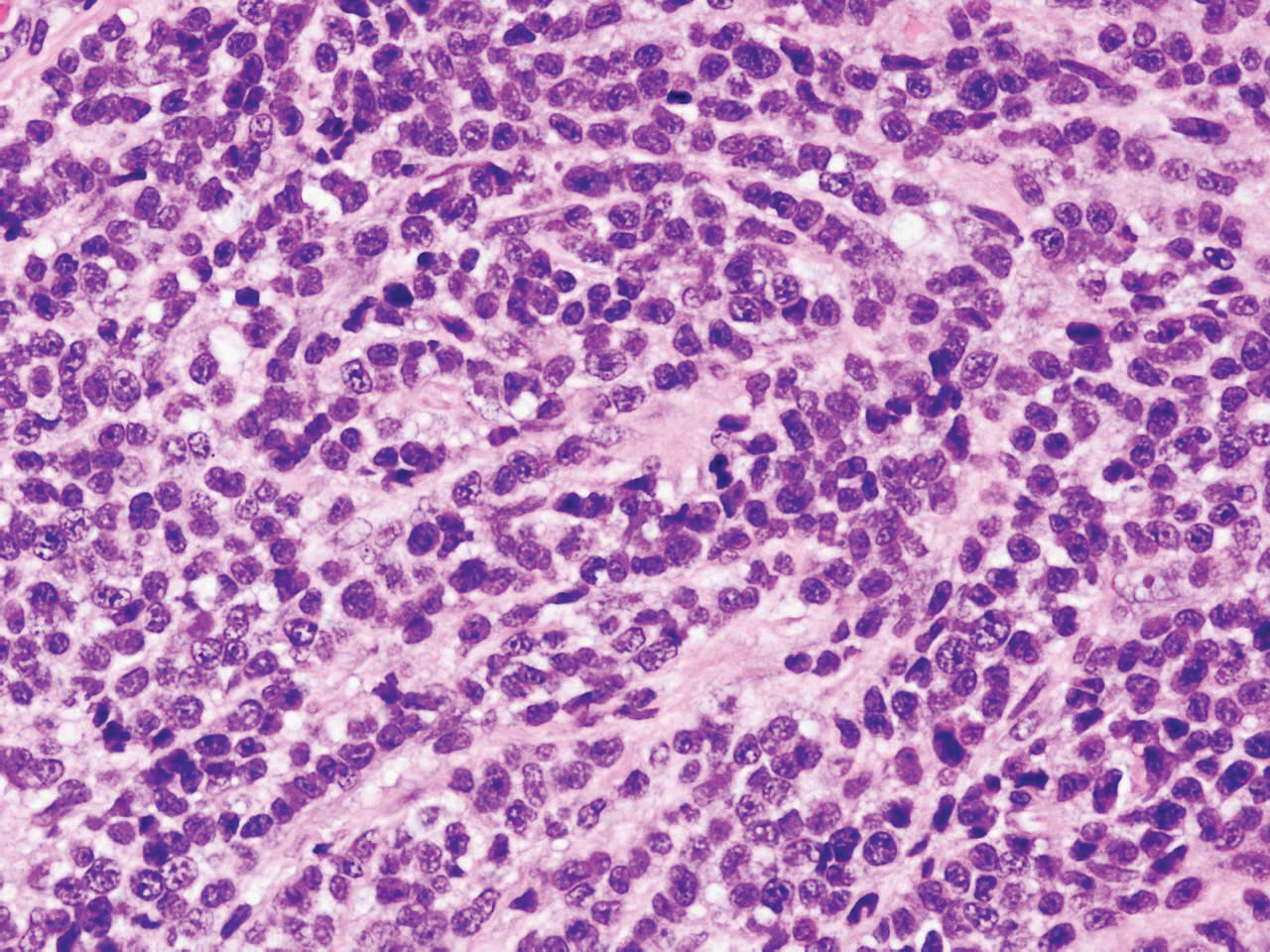

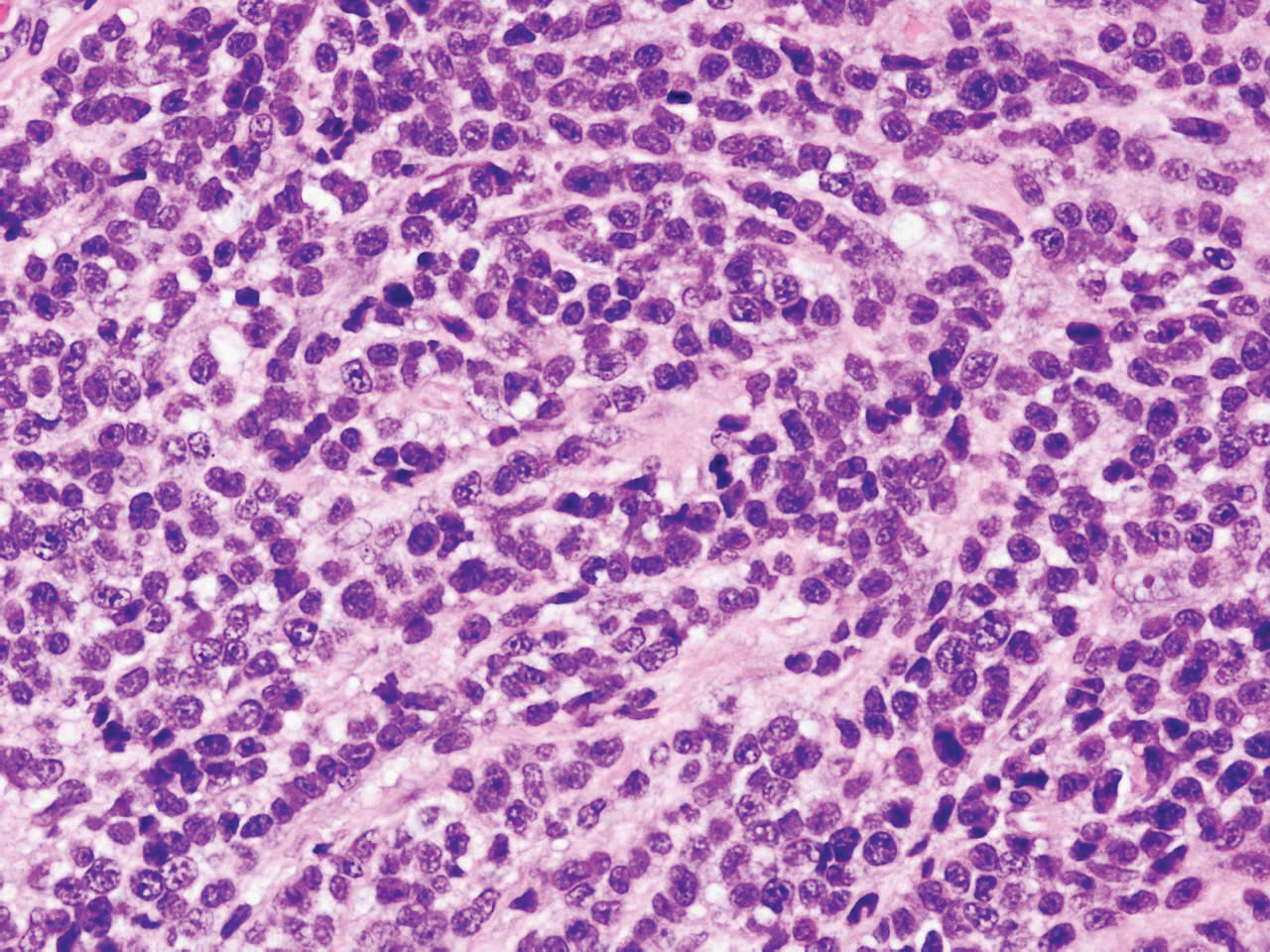

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

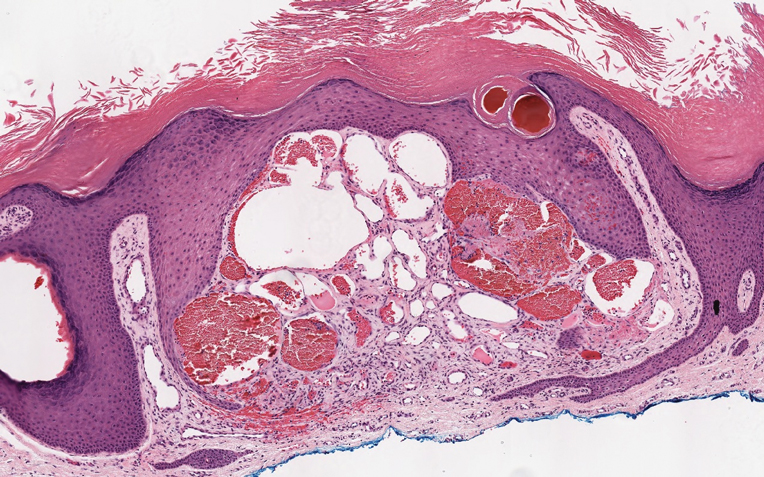

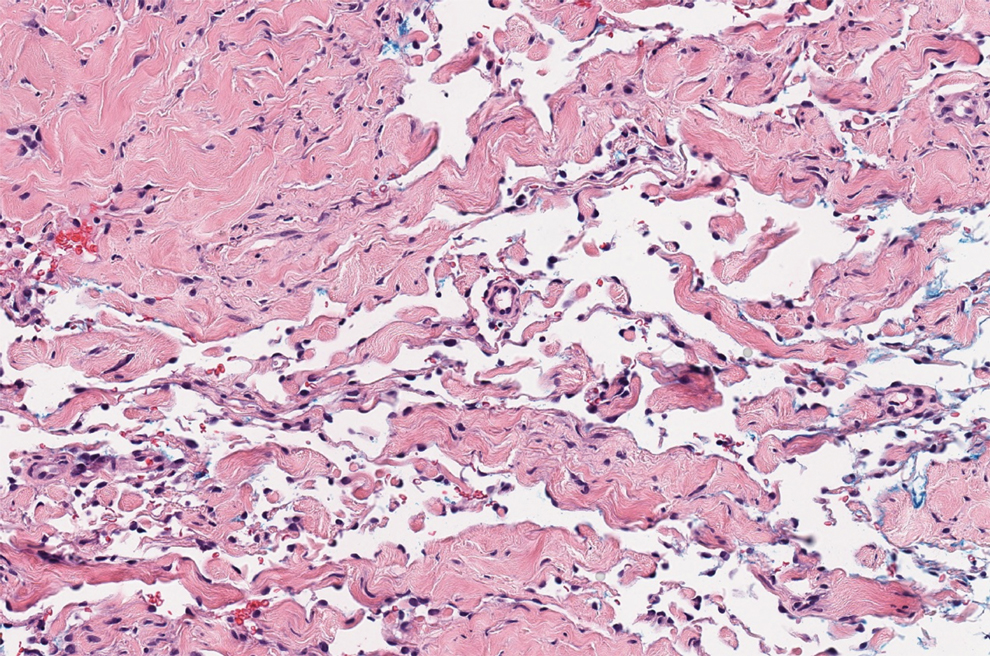

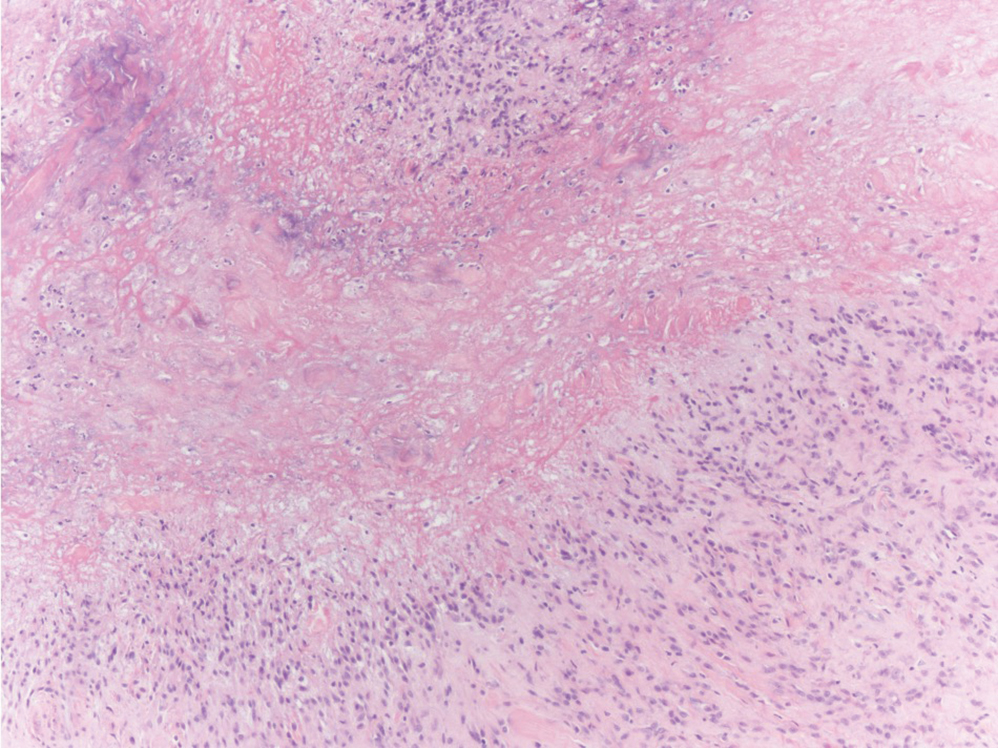

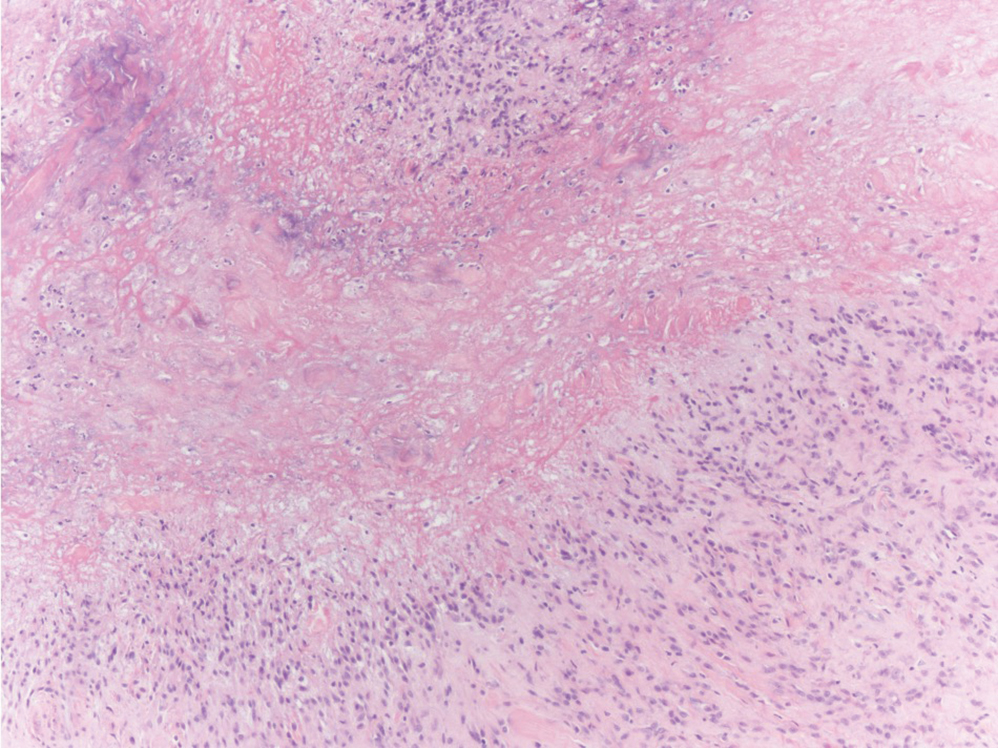

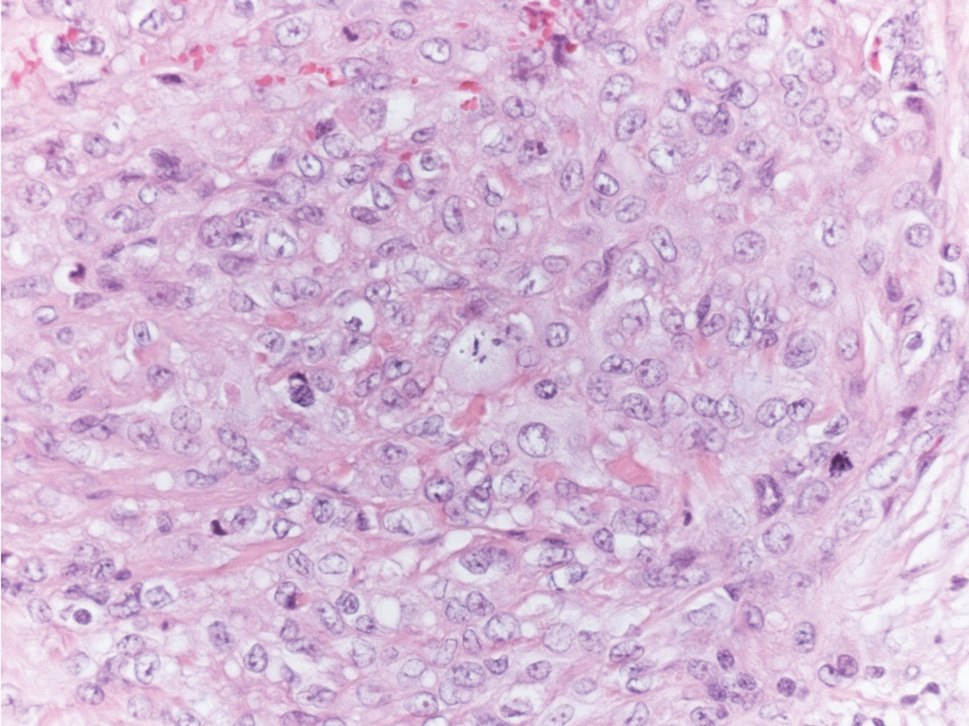

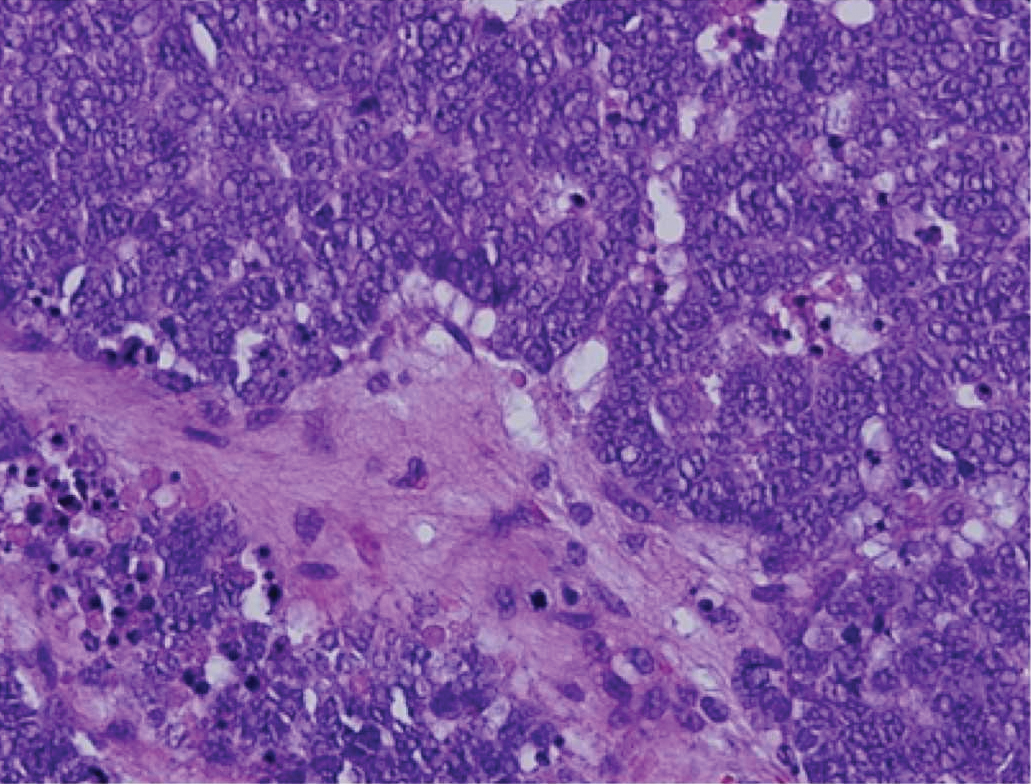

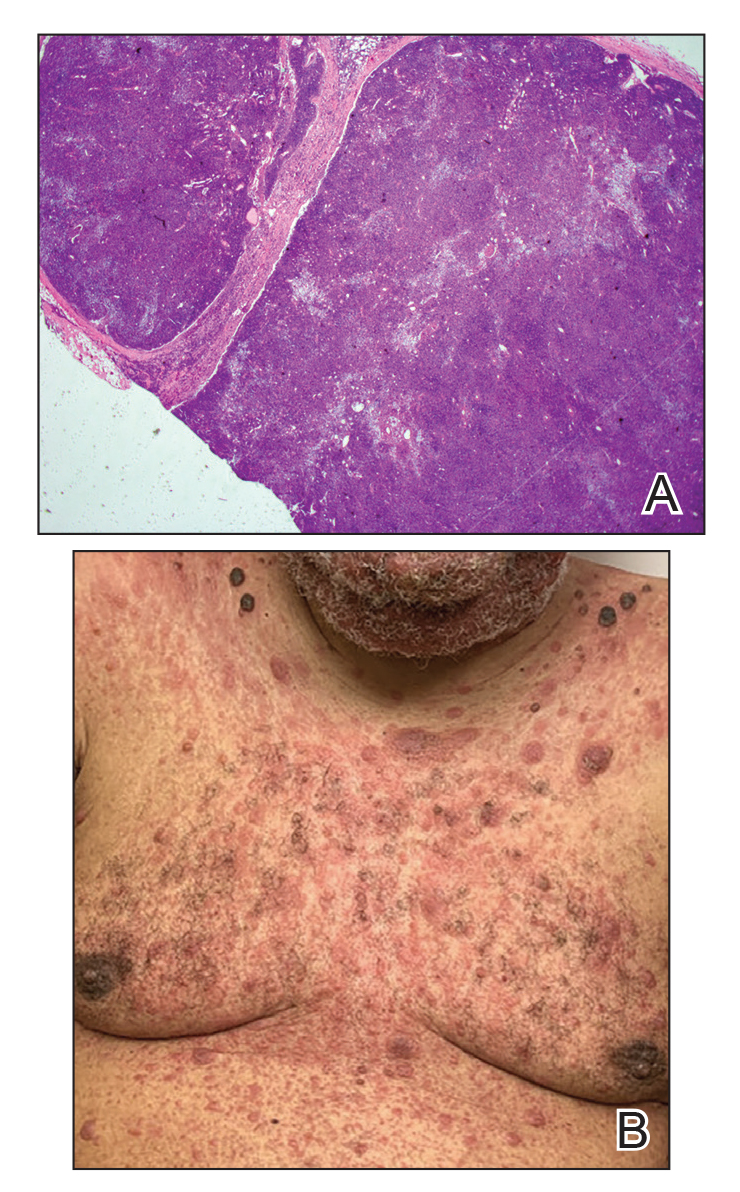

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

A 35-year-old man presented with a reddish brown papule on the left upper chest of 1 year’s duration that had changed color to reddish purple. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm violaceous papule with an erythematous rim.

Tender Soft Tissue Mass on the Base of the Neck

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Panniculitislike T-cell Lymphoma

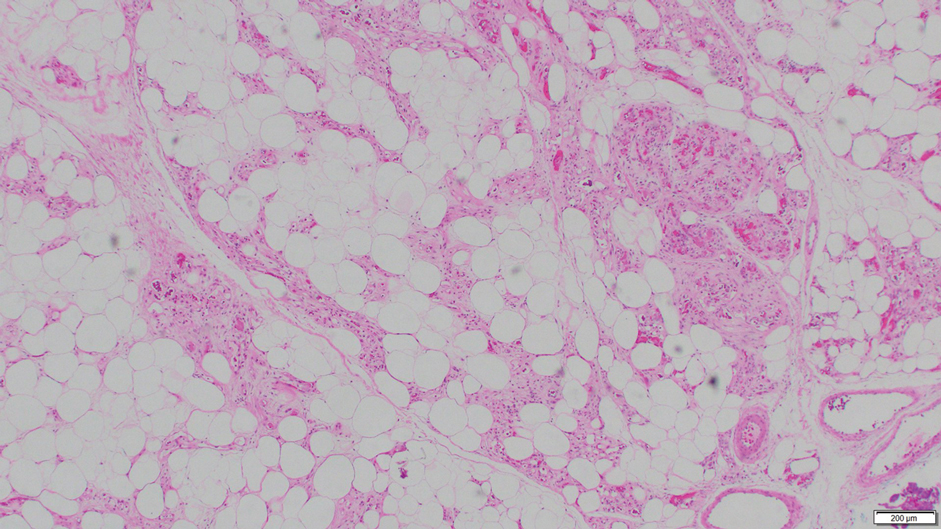

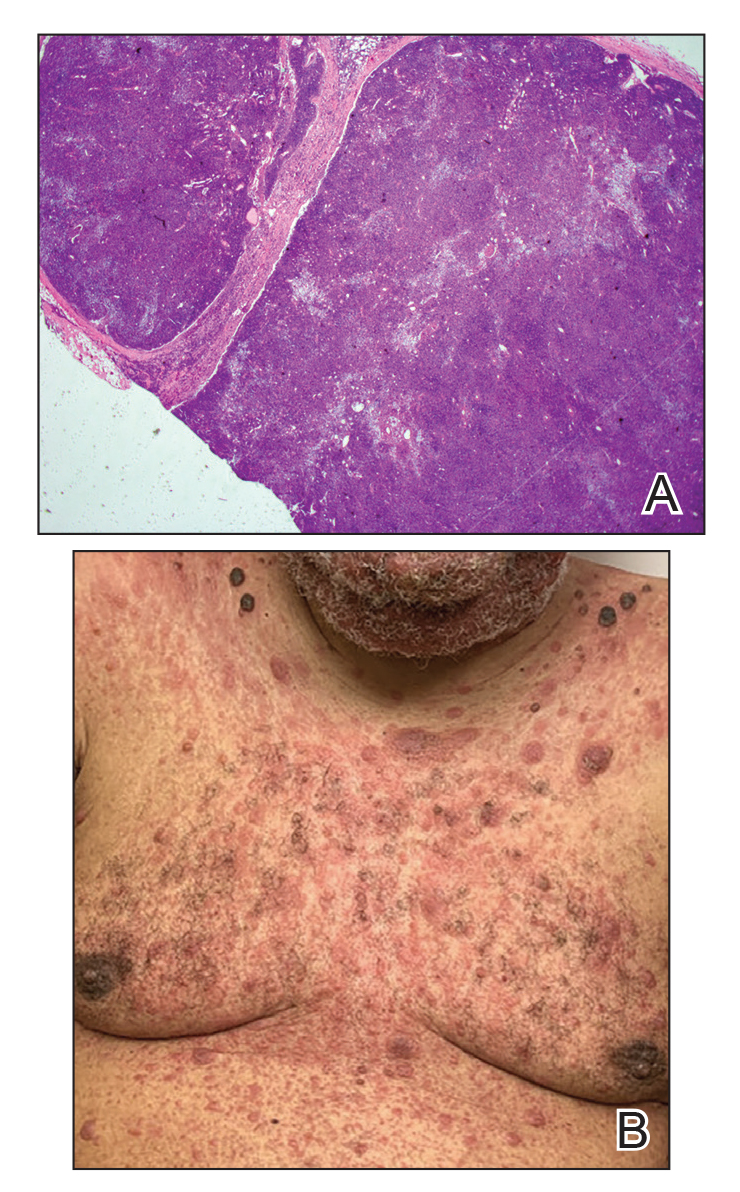

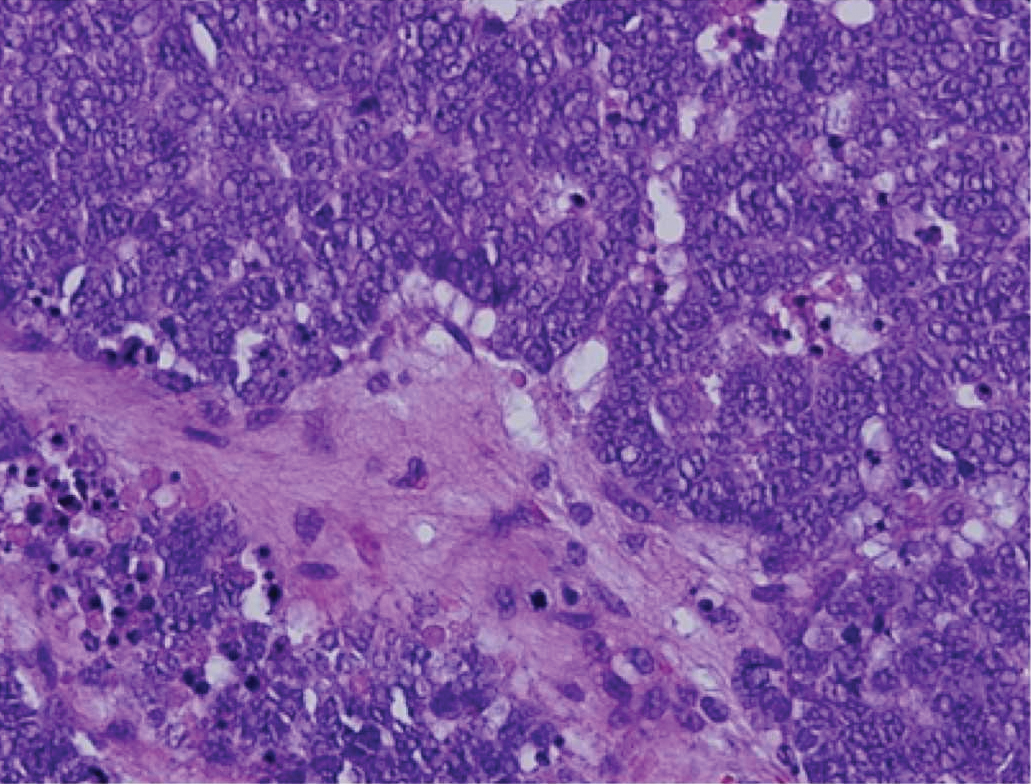

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a rare form of cutaneous lymphoma of mature cytotoxic T cells simulating panniculitis and preferentially infiltrating the subcutaneous tissue.1 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma can affect all ages but predominantly affects younger individuals, with 20% being younger than 20 years.2 It is a rare lymphoma that accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.3 It presents clinically as multiple subcutaneous masses, nodules, or plaques generally on the trunk or extremities.1,2 The skin surrounding the nodules may be erythematous, and the nodules may become necrotic; however, ulceration typically is not seen. Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and chills are present in half of cases.1 According to the World Health Organization, cytopenia and elevated liver function tests are common, and a hemophagocytic syndrome may be present in 15% to 20% of cases.3 The presence of a hemophagocytic syndrome yields a poor prognosis.1,3 Current guidelines denote that SPTCL T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ; is a distinct entity from the TCRγδ; phenotype, known as cutaneous γδ-positive T-cell lymphoma.3,4 Cutaneous γδ-positive T-cell lymphoma is associated with rapid decline and a worse prognosis.4

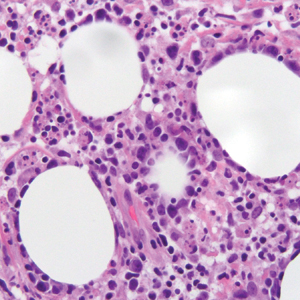

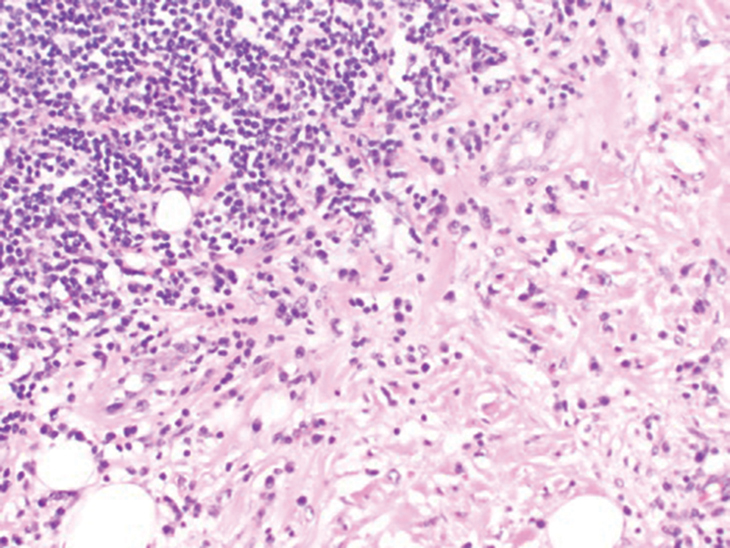

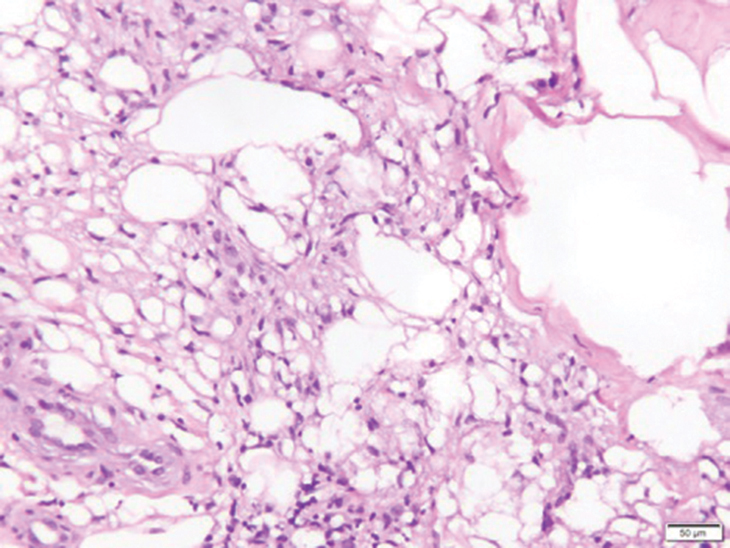

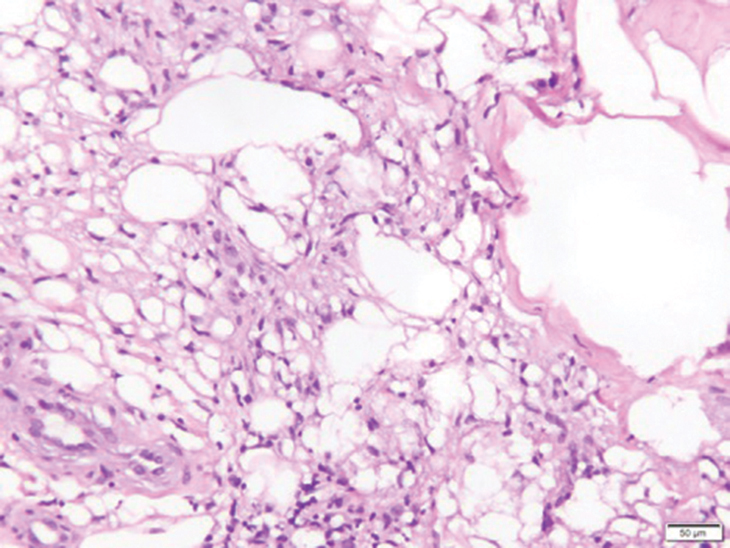

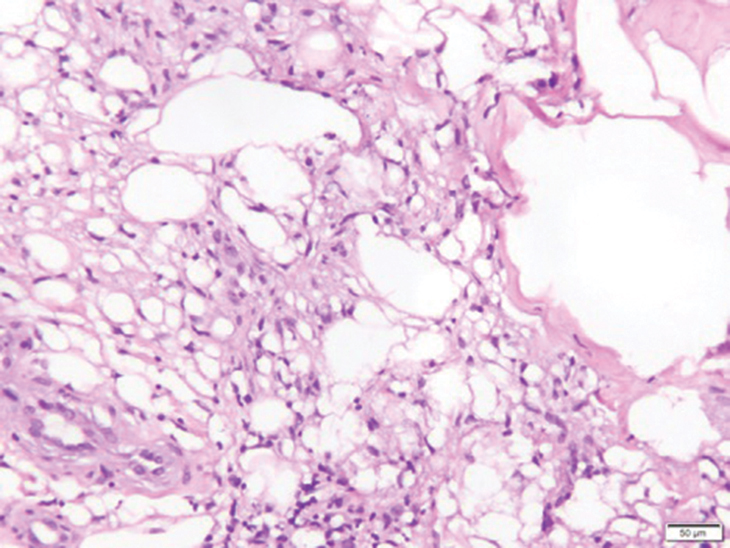

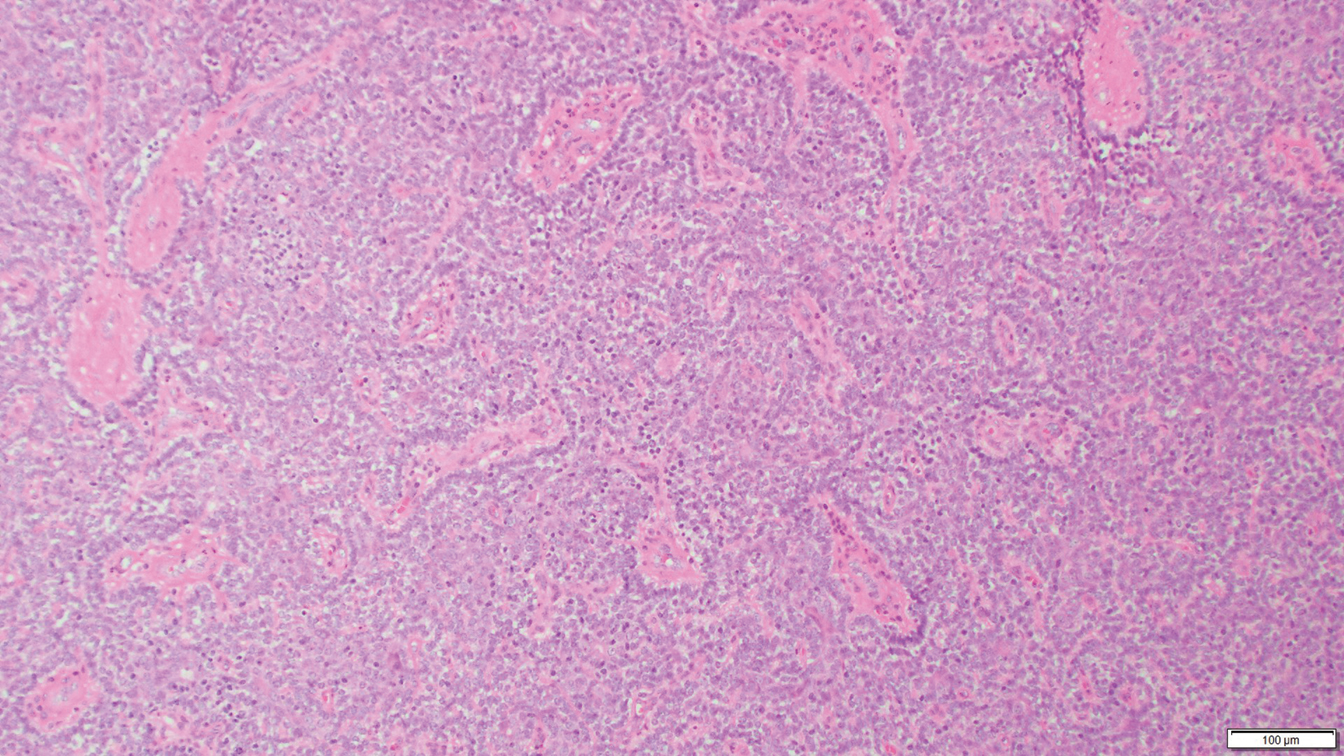

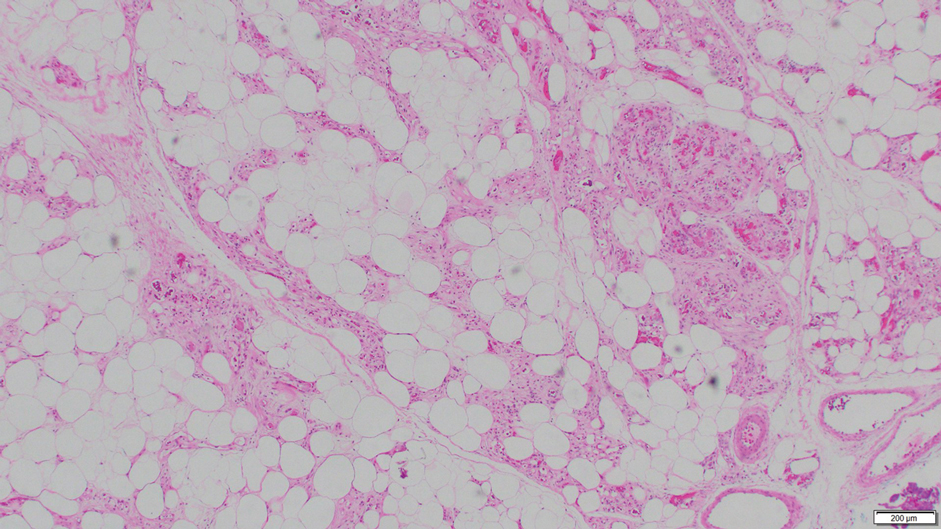

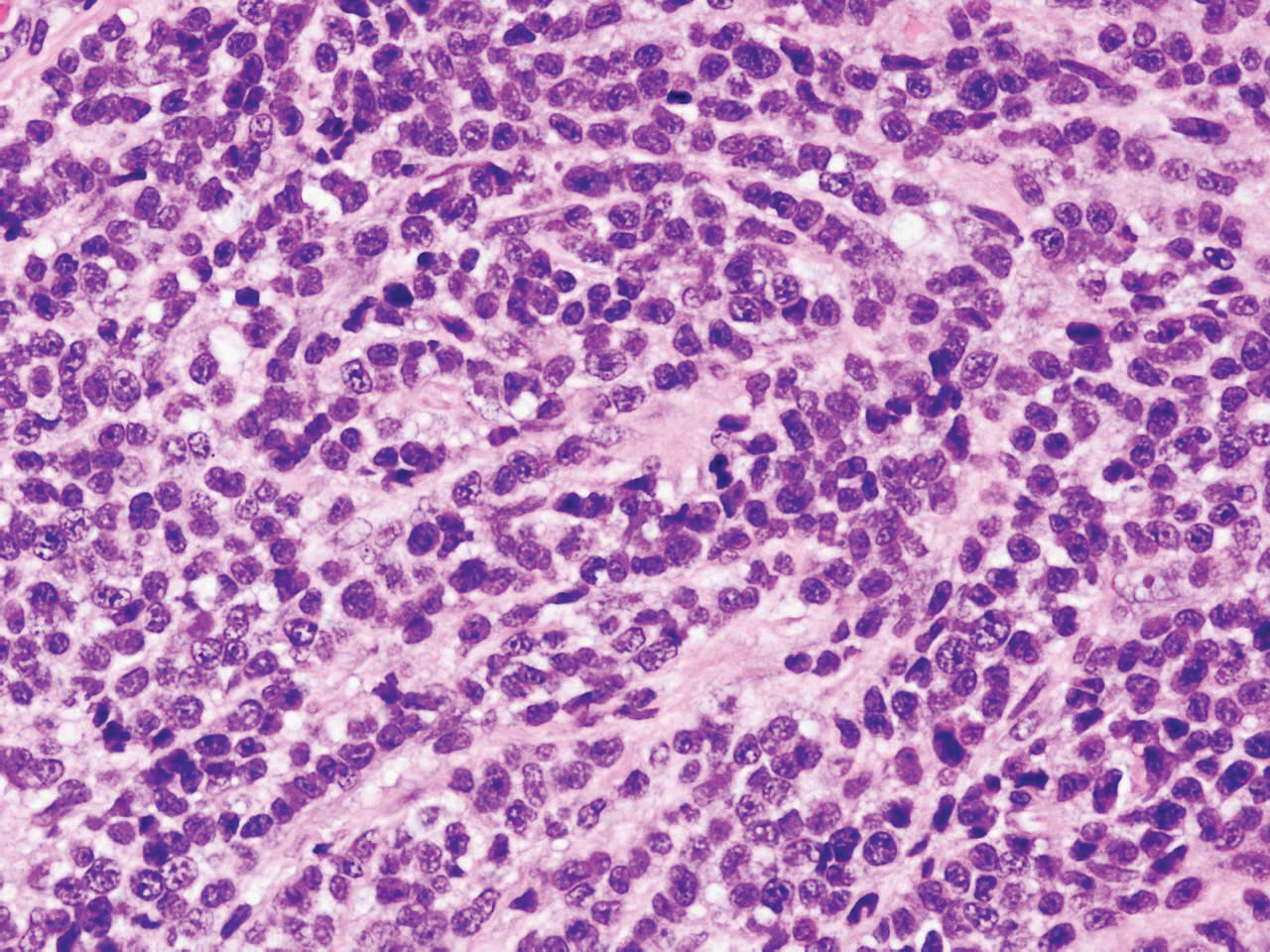

Histology of SPTCL is characteristic for a lobular panniculitislike infiltrate.1 The heavy subcutaneous lymphoid infiltrate is composed of atypical small- to medium-sized lymphocytes with mature chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli lining adipocytes. The dense inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of neoplastic T cells and macrophages may diffusely invade into the subcutaneous tissue.1 Admixed histocytes and karyorrhectic debris as well as rimming of the lymphocytes around the fat cells is typical and was seen in our patient (quiz image). The T cells of SPTCL have the following immunophenotype: TCR-beta F1+, CD3+, CD4-, CD8+, CD56-. They can express numerous cytotoxic proteins, such as T1a-1, granzyme B, and perforin.2,3 Although the CD8+ T cells may be sparse, they generally surround the adipocytes in a rimming manner and may distort the adipocyte membrane.1

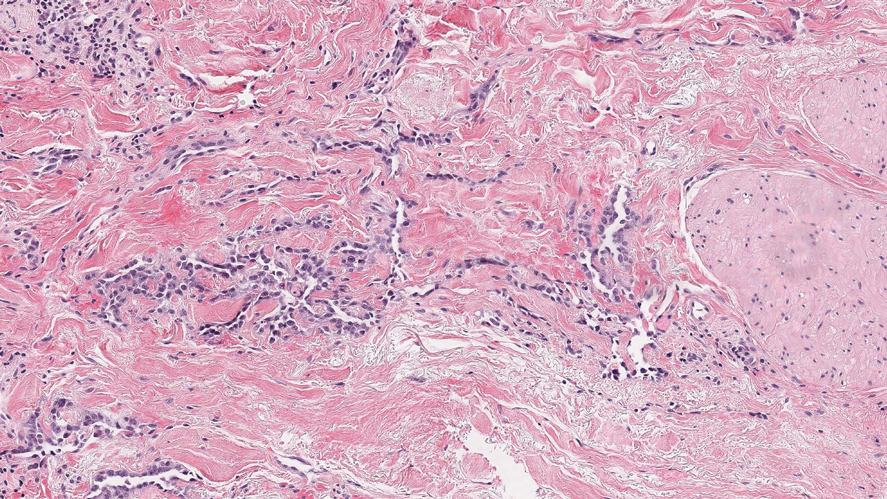

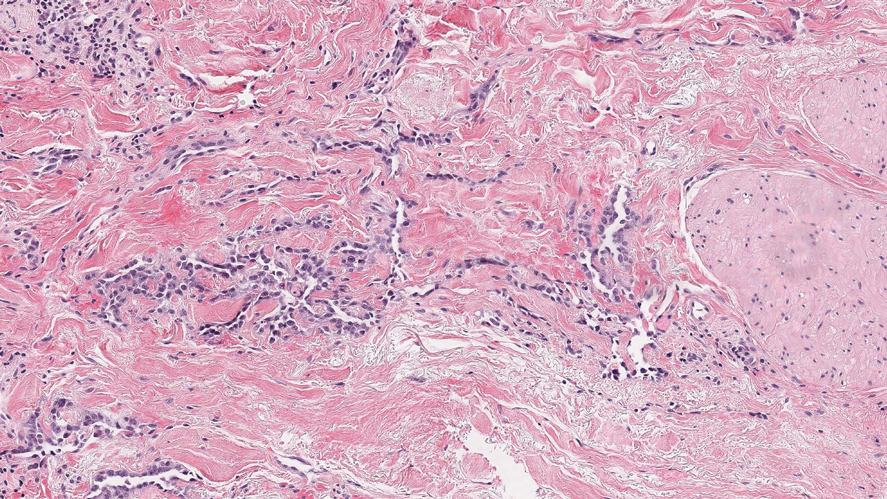

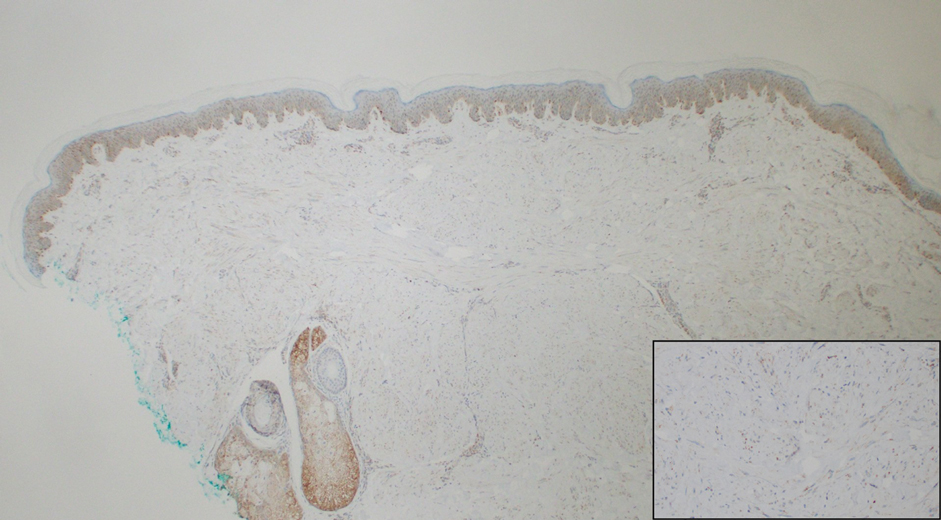

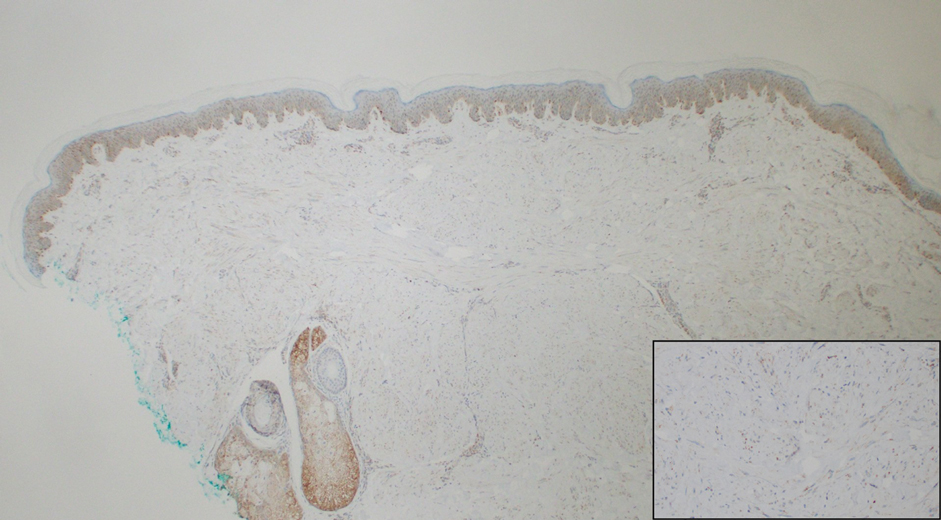

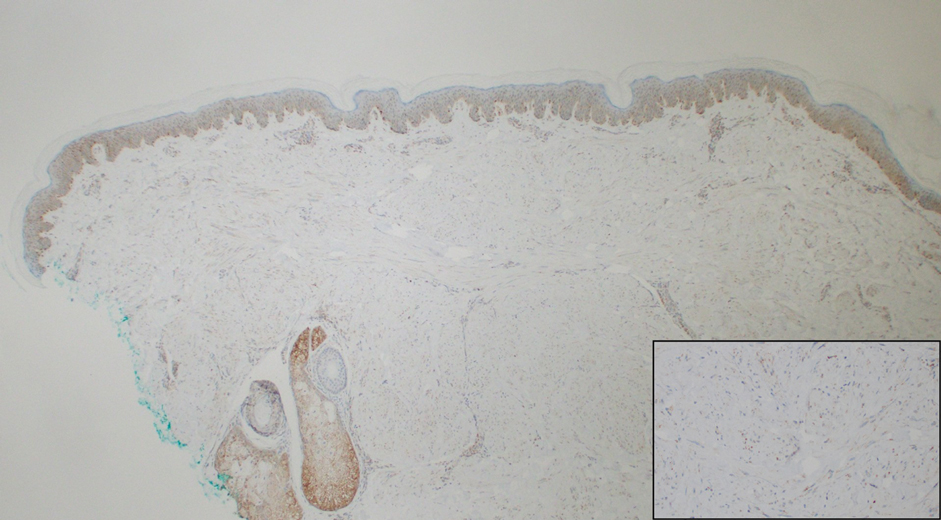

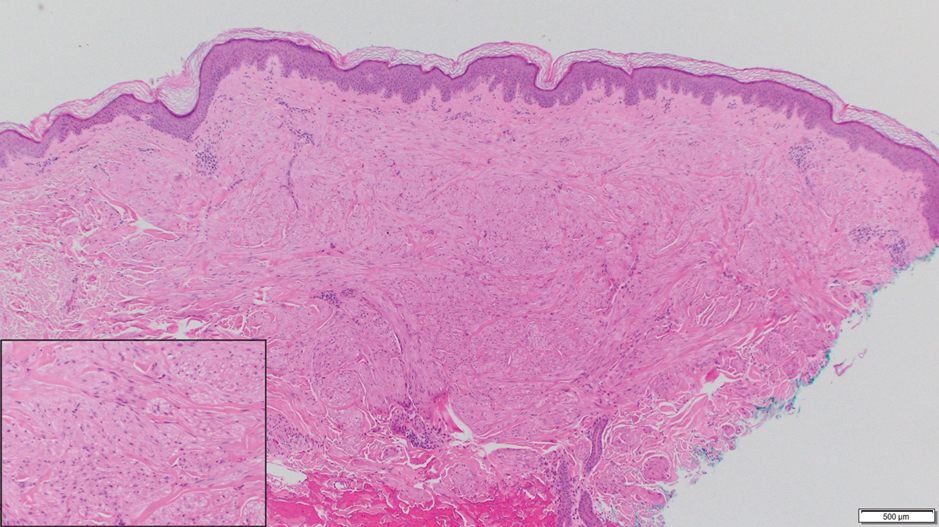

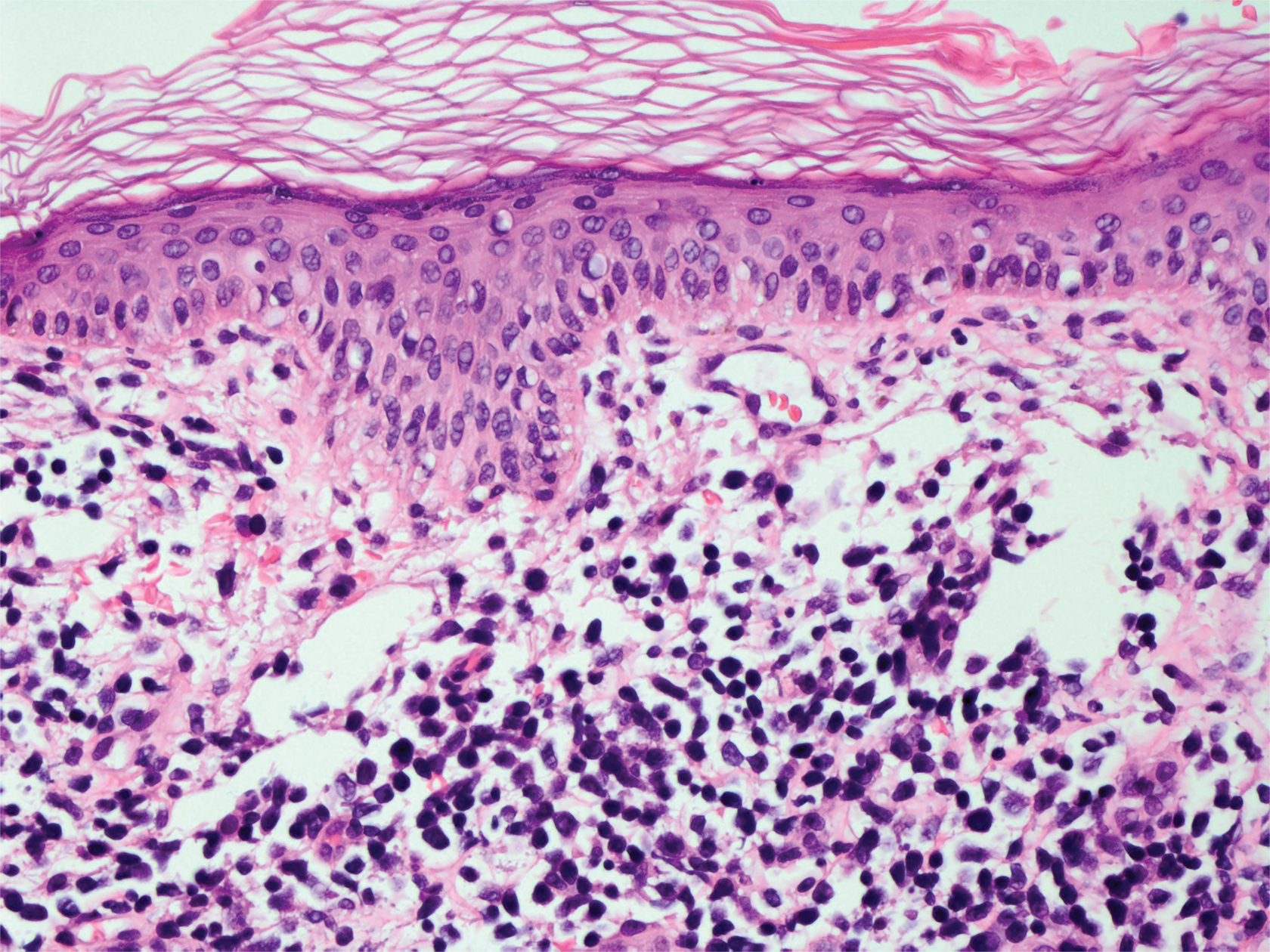

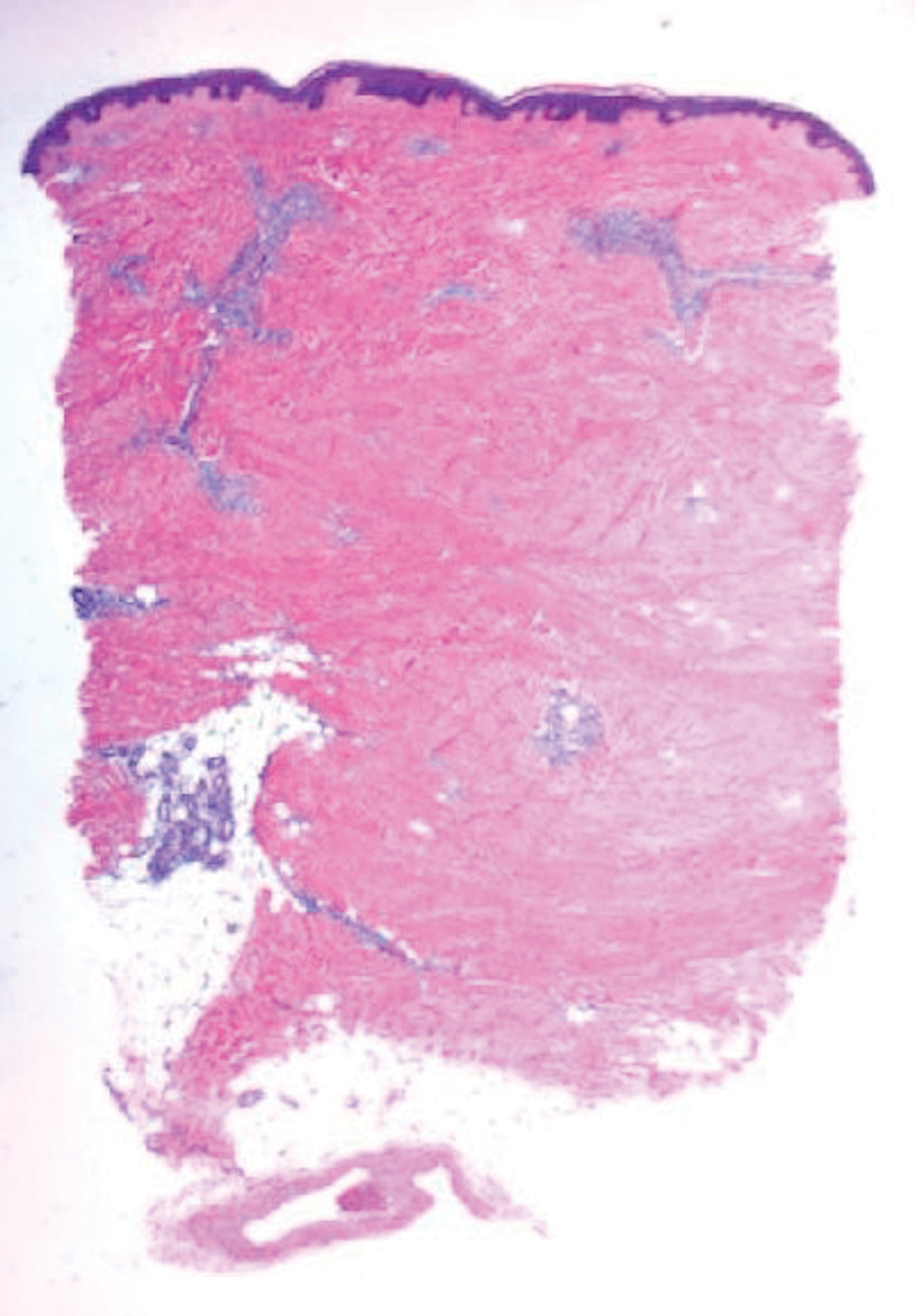

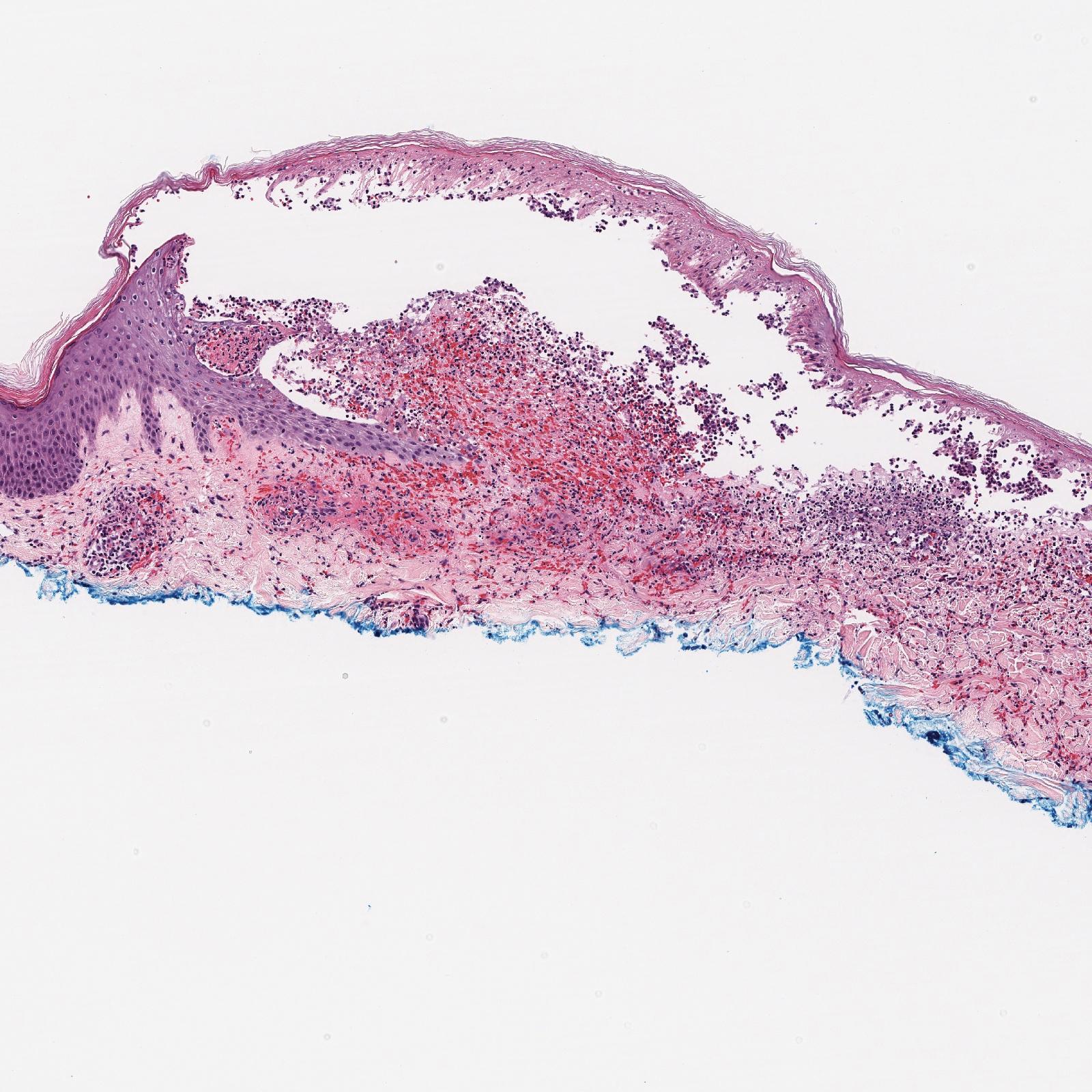

Lupus erythematosus profundus (LEP) is a form of chronic cutaneous lupus that affects the deep dermis and fat.5 It also can present clinically as tender plaques or nodules. It most frequently involves the upper arms, shoulders, face, or buttocks--areas that are less commonly involved in other panniculitides.6 Histologically, LEP is similar to chronic discoid lupus with features such as epidermal atrophy, interface changes, and a thickened basement membrane (Figure 1). Lupus erythematosus profundus can present as a lobular panniculitis with mucin as well as a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate that can involve the septa.5 Some cases of LEP have a predominantly lobular lymphocytic panniculitis in the absence of the typical epidermal or dermal changes of lupus erythematosus. Lymphoid follicles with germinal center formation are present in half of cases and reportedly are characteristic of LEP.6,7 The lymphoid follicles often have plasma cells, can extend into the septa as well as in between collagen bundles, and may have nuclear fragmentation.5 Another characteristic feature of LEP is hyaline sclerosis of lobules with focal extension into the interlobular septa. Immunofluorescence studies usually show linear deposition of IgM and C3 at the dermoepidermal junction. Antinuclear antibodies can be present in patients who have LEP but are not entirely specific.6

Lupus erythematosus profundus and SPTCL are part of a spectrum and may have overlapping clinical and histopathologic characteristics; therefore, distinguishing them may be difficult.6-8 It is important to monitor these patients closely, as their disease may progress to lymphoma.6 Patients with SPTCL are more likely to present with advanced symptoms such as fever and hepatosplenomegaly and to succumb to hemophagocytic syndrome than patients with LEP.9

Although SPTCL usually is clonal, several cases of LEP with clonality also have been described. Clonal LEP cases generally are identified in patients who present with fever and cytopenia.8 Lymphoid atypia and morphologic abnormalities may be seen in cases of LEP, further complicating the distinction between LEP and SPTCL. An elevated Ki67 level may be seen in cases of SPTCL with periadipocytic rimming.9 LeBlanc et al10 used Ki67 "hot spots" along with CD8 immunohistochemistry to identify atypical lymphocytes associated with SPTCL. Lymphocyte rimming was defined by the presence of CD8+ lymphocytes with an elevated Ki67 index. Clinical, histopathologic, and molecular findings all should be used when dealing with challenging cases.

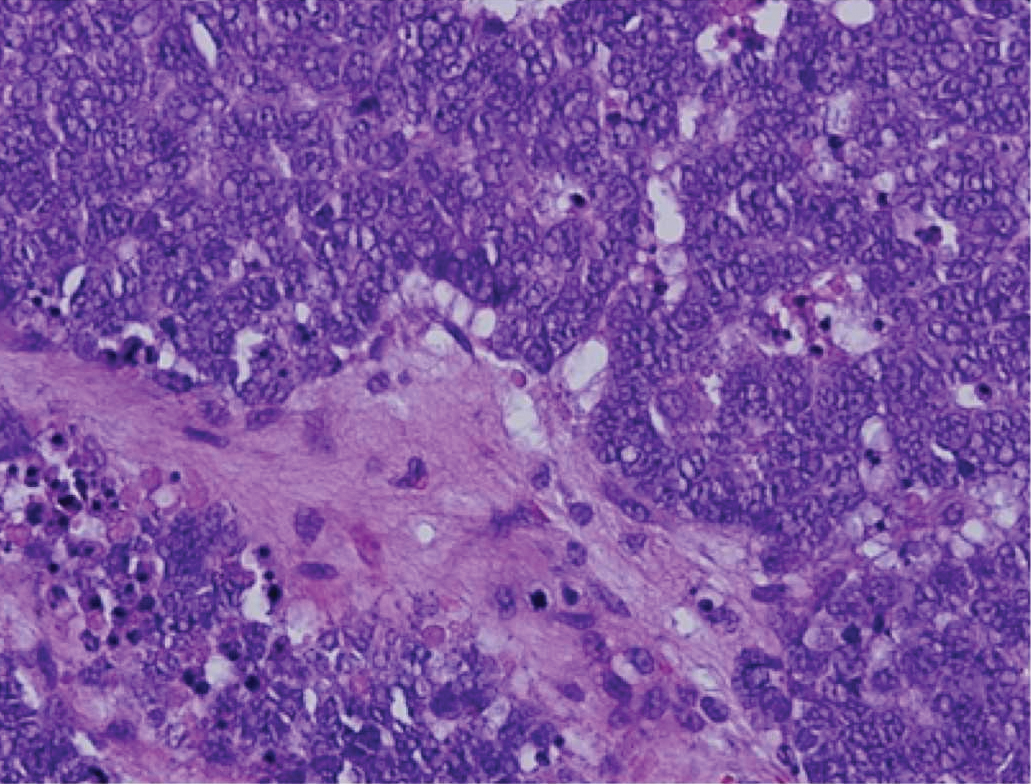

Fat necrosis can occur in any part of the body where trauma has occurred and can be associated with many disease processes. Patients typically present with a palpable mass, but a clinical history of trauma is not always present. Histopathologic findings include necrotic fat alongside lipid-laden foamy macrophages and scattered inflammatory cells (Figure 2).11 Fragments of normal as well as degenerating adipose tissue and multinucleated giant cells can be present.

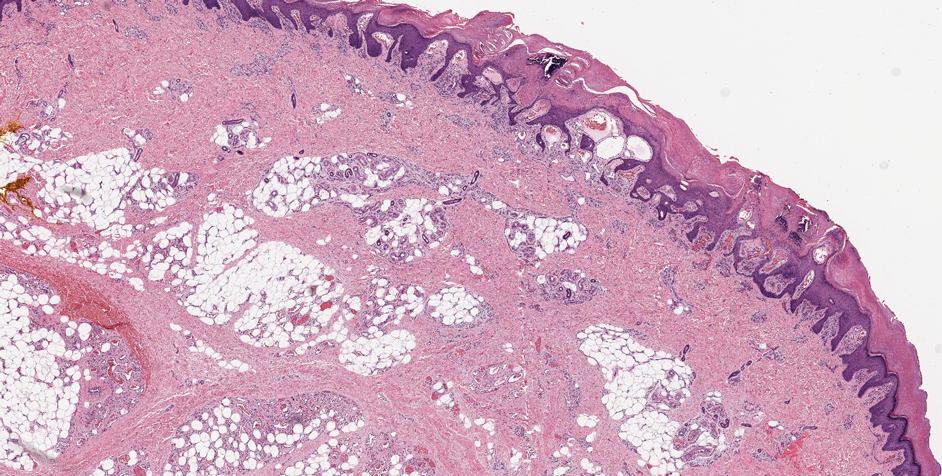

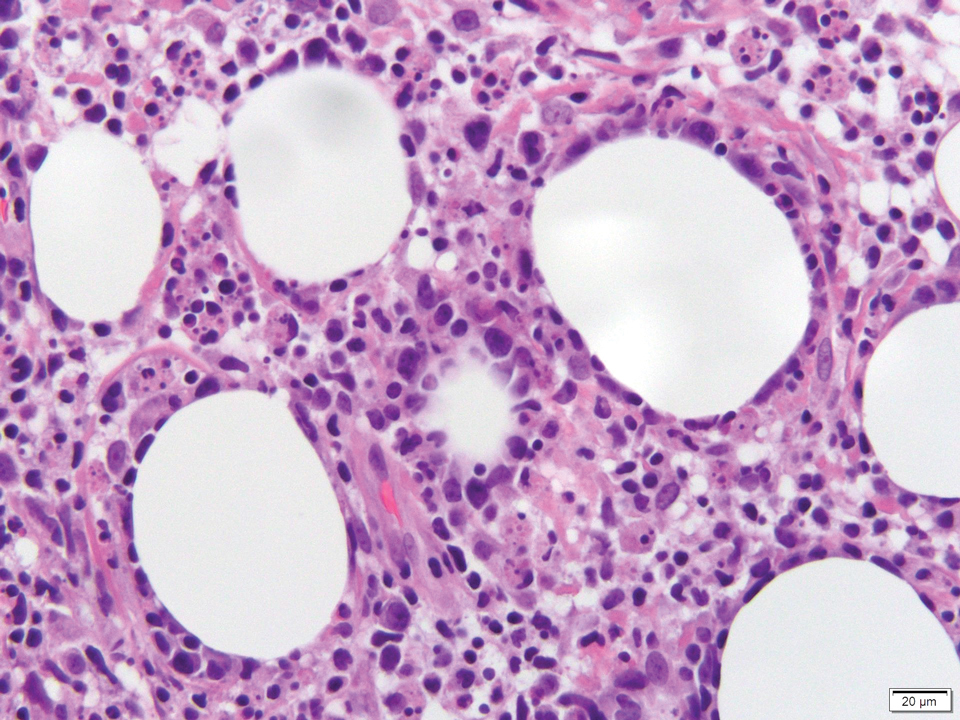

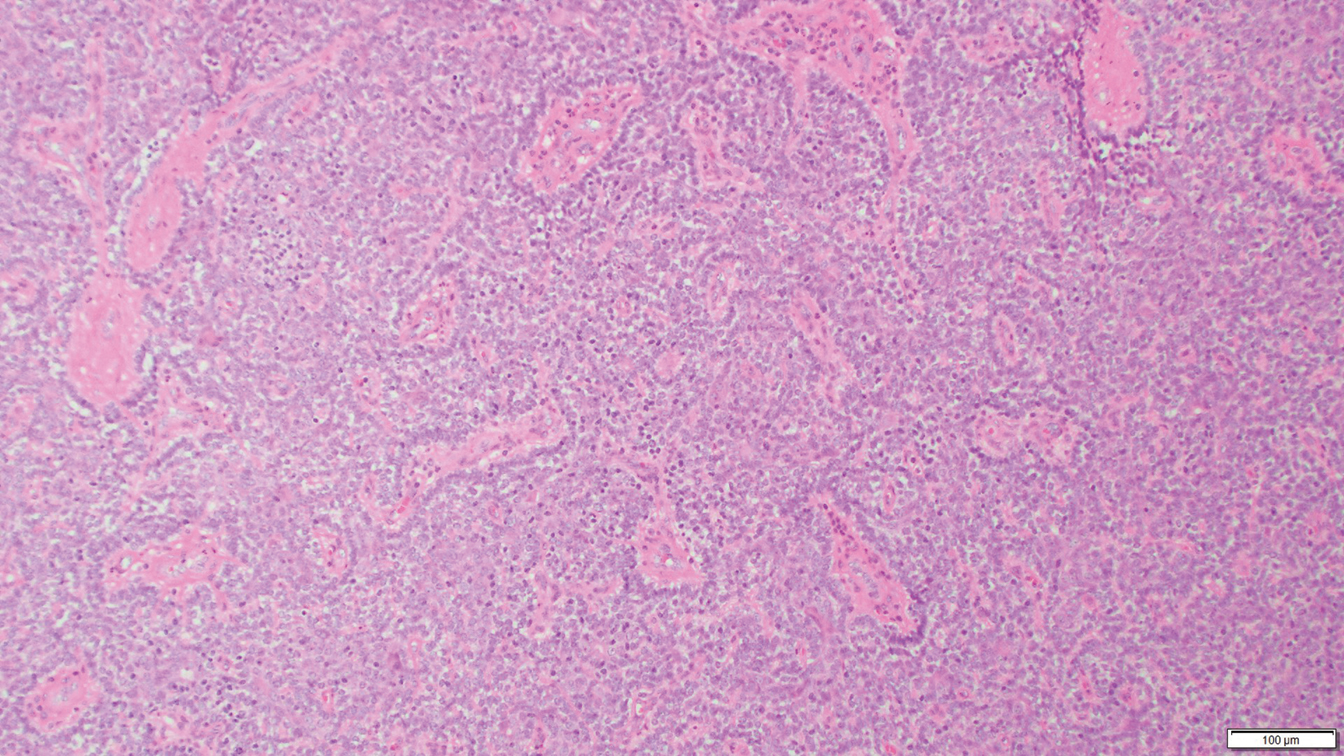

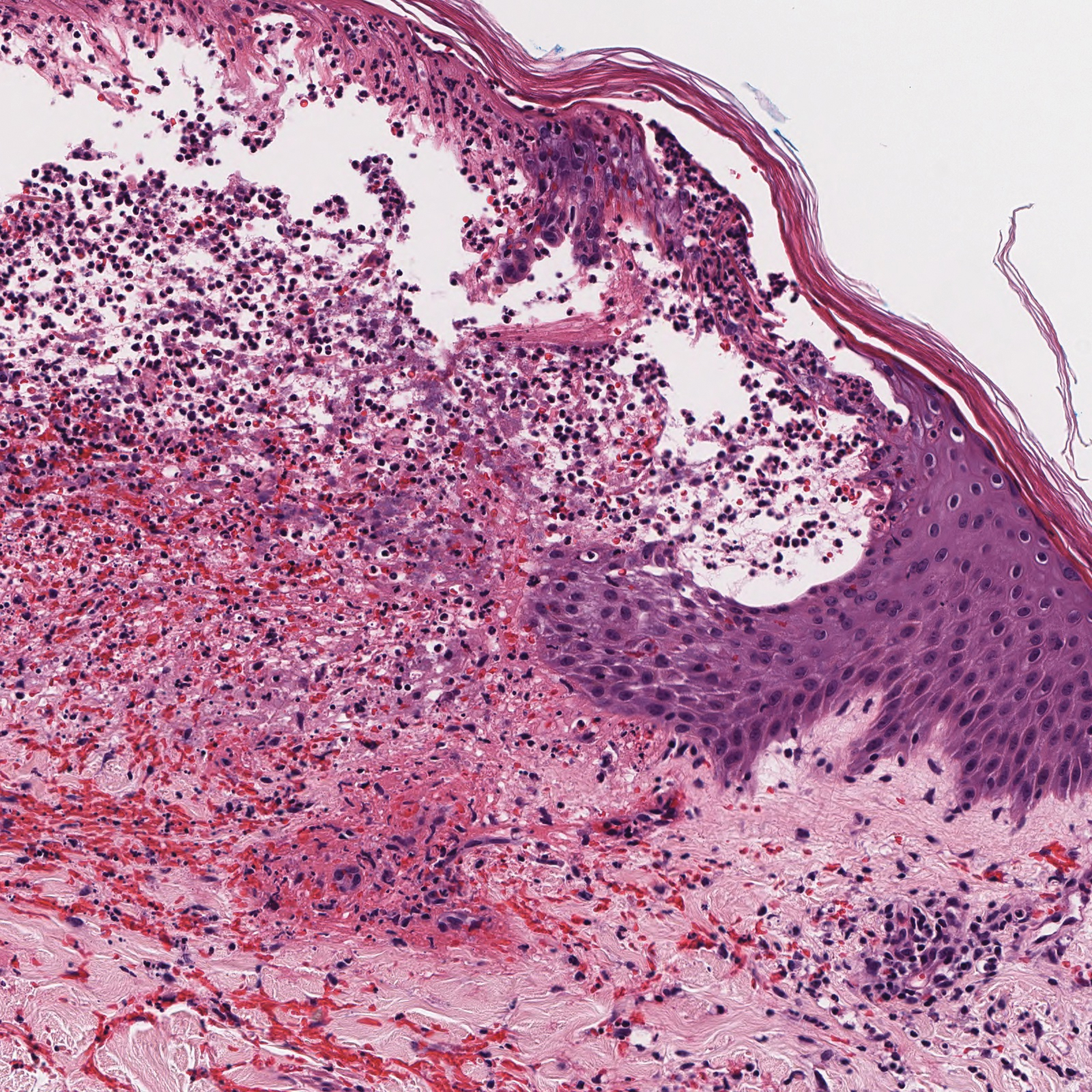

Erythema nodosum (EN) is the most frequently encountered panniculitis and usually is seen in women in early adulthood.12 Patients present with several tender subcutaneous nodules and plaques that most commonly are present on the anterior surface of the legs.12,13 Patients may have a constellation of symptoms including fever and leukocytosis, but the disorder generally is self-limited.12 Erythema nodosum may be associated with a variety of diseases or infections including sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy.14 The etiology of EN is diverse; therefore, a proper clinical workup may be necessary. Histopathology is that of a septal panniculitis with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and occasional eosinophils (Figure 3).13

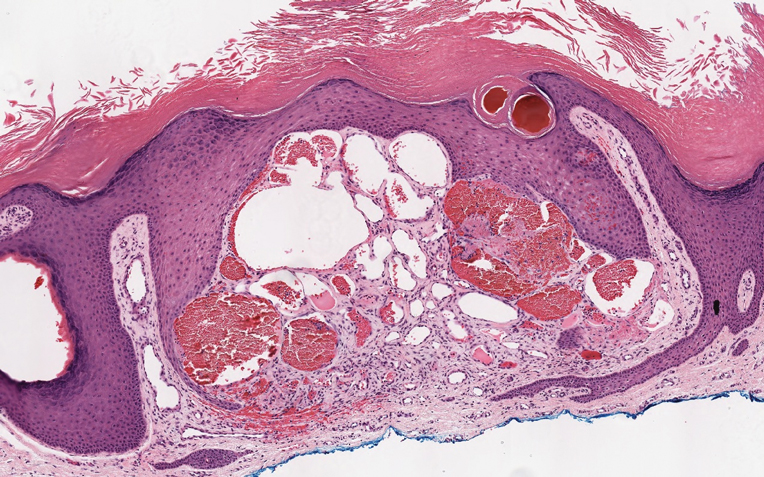

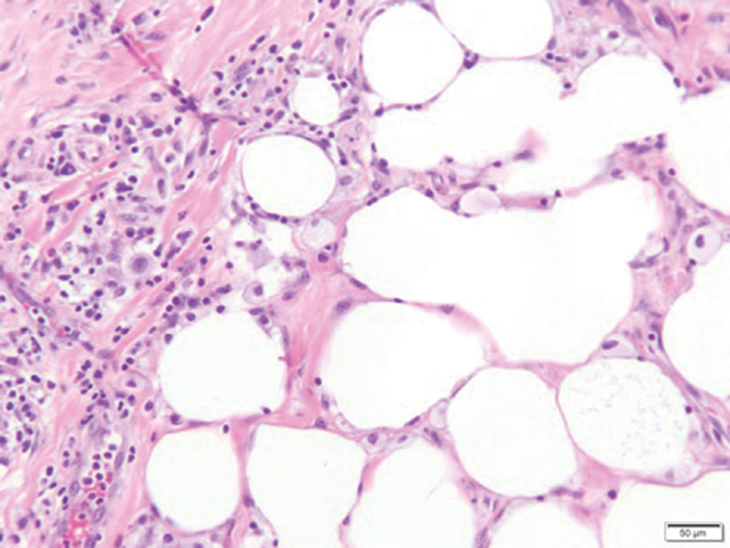

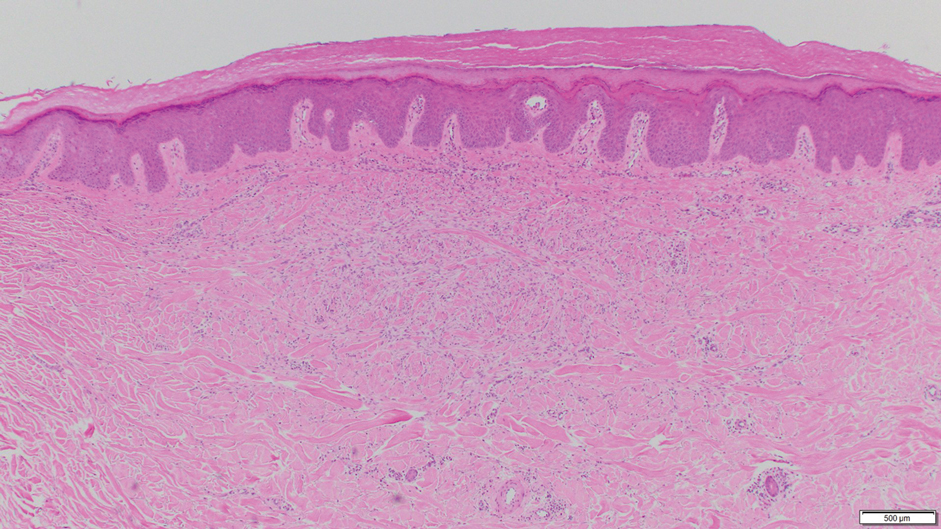

Lipodermatosclerosis also occurs on the legs, most commonly in patients with venous insufficiency.12,15 Patients present clinically with pain, induration, redness, or swelling of the legs. Histopathology predominantly is characterized by membranous fat necrosis, fibrosis, and fatty microcysts that may be lined by a thickened hyaline membrane (Figure 4). Lipodermatosclerosis lesions generally do not resolve spontaneously and may need to be treated.16

- Musick SR, Lynch DT. Subcutaneous Panniculitis Like T-cell Lymphoma. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Guenova E, Schanz S, Hoetzenecker W, et al. Systemic corticosteroids for subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:891-894.

- Swerdlow SH. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017.

- Bagheri F, Cervellione KL, Delgado B, et al. An illustrative case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [published online March 3, 2011]. J Skin Cancer. doi:10.1155/2011/824528

- Kogame T, Yamashita R, Hirata M, et al. Analysis of possible structures of inducible skin‐associated lymphoid tissue in lupus erythematosus profundus. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1117-1121.

- Arps DP, Patel RM. Lupus profundus (panniculitis): a potential mimic of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1211-1215.

- Alberti-Violetti S, Berti E. Lymphocytic lobular panniculitis: a diagnostic challenge. Dermatopathology. 2018;5:30-33.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN, Kovatich AJ, et al. Lupus profundus, indeterminate lymphocytic lobular panniculitis and subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a spectrum of subcuticular T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:235-247.

- Sitthinamsuwan P, Pattanaprichakul P, Treetipsatit J, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma versus lupus erythematosus panniculitis: distinction by means of the periadipocytic cell proliferation index. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:567-574.

- LeBlanc RE, Tavallaee M, Kim YH, et al. Useful parameters for distinguishing subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma from lupus erythematosus panniculitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:745-754.

- Burkholz KJ, Roberts CC, Lidner TK. Posttraumatic pseudolipoma (fat necrosis) mimicking atypical lipoma or liposarcoma on MRI. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;2:56-60.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Thurber S, Kohler S. Histopathologic spectrum of erythema nodosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:18-26.

- Requena L, Requena C. Erythema nodosum. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:4.

- Choonhakarn C, Chaowattanapanit S, Julanon N. Lipodermatosclerosis: a clinicopathologic correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:303-308.

- Huang TM, Lee JY. Lipodermatosclerosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases and differential diagnosis from erythema nodosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:453-460.

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Panniculitislike T-cell Lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a rare form of cutaneous lymphoma of mature cytotoxic T cells simulating panniculitis and preferentially infiltrating the subcutaneous tissue.1 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma can affect all ages but predominantly affects younger individuals, with 20% being younger than 20 years.2 It is a rare lymphoma that accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.3 It presents clinically as multiple subcutaneous masses, nodules, or plaques generally on the trunk or extremities.1,2 The skin surrounding the nodules may be erythematous, and the nodules may become necrotic; however, ulceration typically is not seen. Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and chills are present in half of cases.1 According to the World Health Organization, cytopenia and elevated liver function tests are common, and a hemophagocytic syndrome may be present in 15% to 20% of cases.3 The presence of a hemophagocytic syndrome yields a poor prognosis.1,3 Current guidelines denote that SPTCL T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ; is a distinct entity from the TCRγδ; phenotype, known as cutaneous γδ-positive T-cell lymphoma.3,4 Cutaneous γδ-positive T-cell lymphoma is associated with rapid decline and a worse prognosis.4

Histology of SPTCL is characteristic for a lobular panniculitislike infiltrate.1 The heavy subcutaneous lymphoid infiltrate is composed of atypical small- to medium-sized lymphocytes with mature chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli lining adipocytes. The dense inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of neoplastic T cells and macrophages may diffusely invade into the subcutaneous tissue.1 Admixed histocytes and karyorrhectic debris as well as rimming of the lymphocytes around the fat cells is typical and was seen in our patient (quiz image). The T cells of SPTCL have the following immunophenotype: TCR-beta F1+, CD3+, CD4-, CD8+, CD56-. They can express numerous cytotoxic proteins, such as T1a-1, granzyme B, and perforin.2,3 Although the CD8+ T cells may be sparse, they generally surround the adipocytes in a rimming manner and may distort the adipocyte membrane.1

Lupus erythematosus profundus (LEP) is a form of chronic cutaneous lupus that affects the deep dermis and fat.5 It also can present clinically as tender plaques or nodules. It most frequently involves the upper arms, shoulders, face, or buttocks--areas that are less commonly involved in other panniculitides.6 Histologically, LEP is similar to chronic discoid lupus with features such as epidermal atrophy, interface changes, and a thickened basement membrane (Figure 1). Lupus erythematosus profundus can present as a lobular panniculitis with mucin as well as a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate that can involve the septa.5 Some cases of LEP have a predominantly lobular lymphocytic panniculitis in the absence of the typical epidermal or dermal changes of lupus erythematosus. Lymphoid follicles with germinal center formation are present in half of cases and reportedly are characteristic of LEP.6,7 The lymphoid follicles often have plasma cells, can extend into the septa as well as in between collagen bundles, and may have nuclear fragmentation.5 Another characteristic feature of LEP is hyaline sclerosis of lobules with focal extension into the interlobular septa. Immunofluorescence studies usually show linear deposition of IgM and C3 at the dermoepidermal junction. Antinuclear antibodies can be present in patients who have LEP but are not entirely specific.6

Lupus erythematosus profundus and SPTCL are part of a spectrum and may have overlapping clinical and histopathologic characteristics; therefore, distinguishing them may be difficult.6-8 It is important to monitor these patients closely, as their disease may progress to lymphoma.6 Patients with SPTCL are more likely to present with advanced symptoms such as fever and hepatosplenomegaly and to succumb to hemophagocytic syndrome than patients with LEP.9

Although SPTCL usually is clonal, several cases of LEP with clonality also have been described. Clonal LEP cases generally are identified in patients who present with fever and cytopenia.8 Lymphoid atypia and morphologic abnormalities may be seen in cases of LEP, further complicating the distinction between LEP and SPTCL. An elevated Ki67 level may be seen in cases of SPTCL with periadipocytic rimming.9 LeBlanc et al10 used Ki67 "hot spots" along with CD8 immunohistochemistry to identify atypical lymphocytes associated with SPTCL. Lymphocyte rimming was defined by the presence of CD8+ lymphocytes with an elevated Ki67 index. Clinical, histopathologic, and molecular findings all should be used when dealing with challenging cases.

Fat necrosis can occur in any part of the body where trauma has occurred and can be associated with many disease processes. Patients typically present with a palpable mass, but a clinical history of trauma is not always present. Histopathologic findings include necrotic fat alongside lipid-laden foamy macrophages and scattered inflammatory cells (Figure 2).11 Fragments of normal as well as degenerating adipose tissue and multinucleated giant cells can be present.

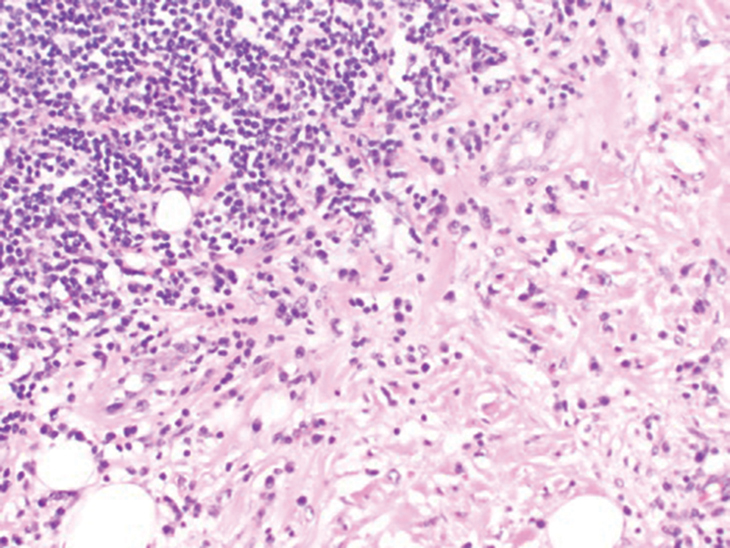

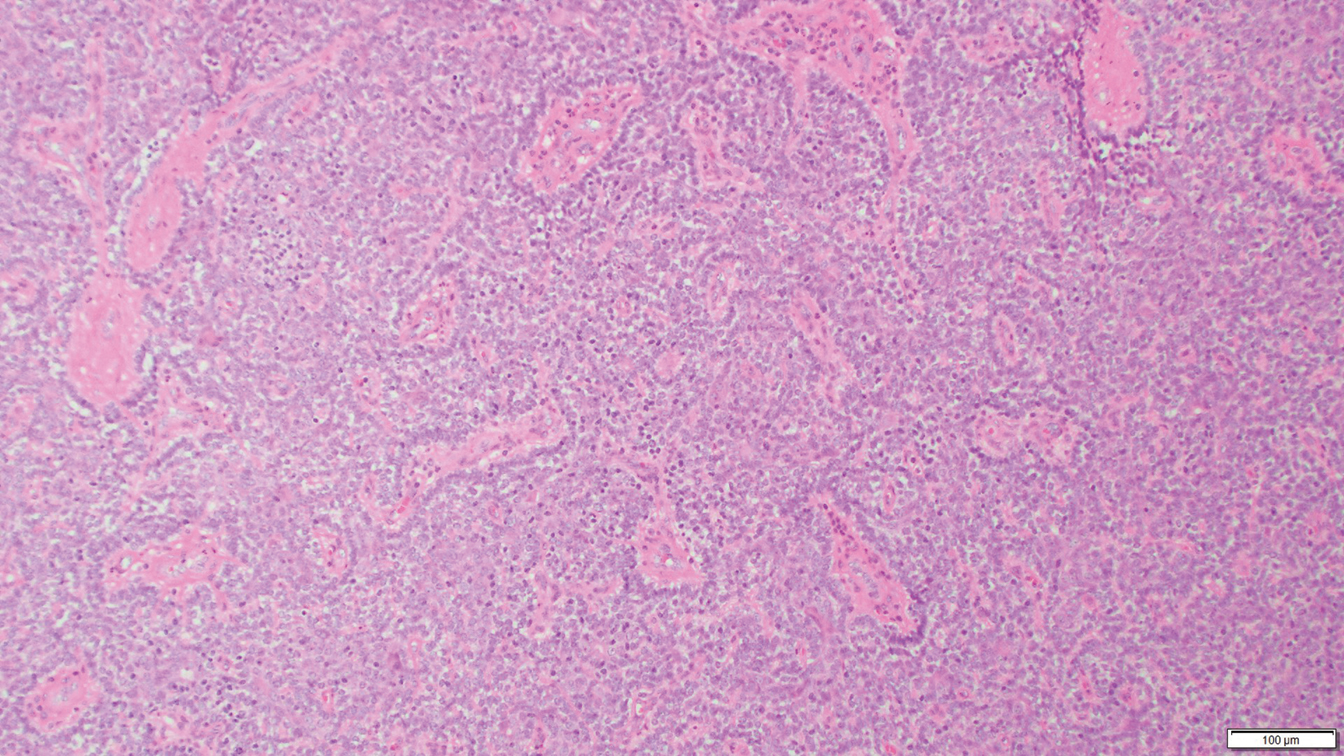

Erythema nodosum (EN) is the most frequently encountered panniculitis and usually is seen in women in early adulthood.12 Patients present with several tender subcutaneous nodules and plaques that most commonly are present on the anterior surface of the legs.12,13 Patients may have a constellation of symptoms including fever and leukocytosis, but the disorder generally is self-limited.12 Erythema nodosum may be associated with a variety of diseases or infections including sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy.14 The etiology of EN is diverse; therefore, a proper clinical workup may be necessary. Histopathology is that of a septal panniculitis with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and occasional eosinophils (Figure 3).13

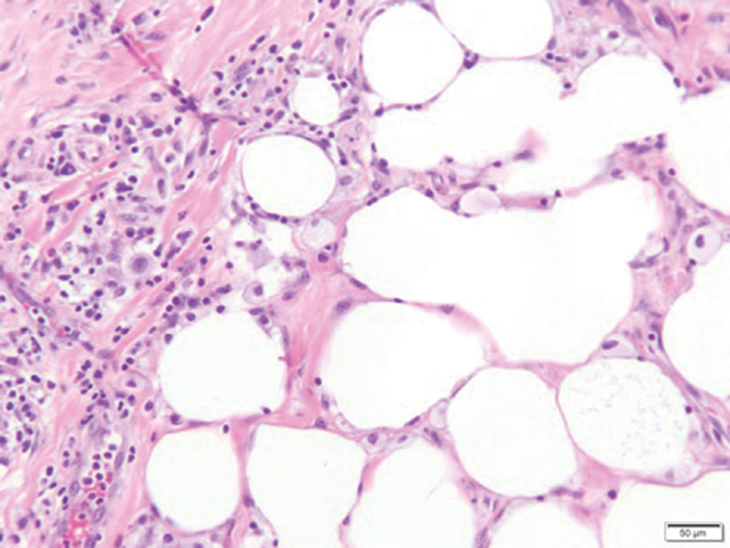

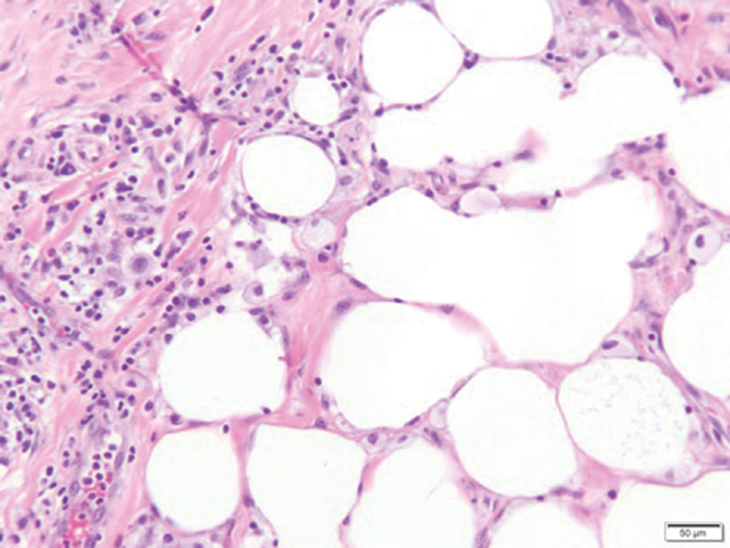

Lipodermatosclerosis also occurs on the legs, most commonly in patients with venous insufficiency.12,15 Patients present clinically with pain, induration, redness, or swelling of the legs. Histopathology predominantly is characterized by membranous fat necrosis, fibrosis, and fatty microcysts that may be lined by a thickened hyaline membrane (Figure 4). Lipodermatosclerosis lesions generally do not resolve spontaneously and may need to be treated.16

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Panniculitislike T-cell Lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a rare form of cutaneous lymphoma of mature cytotoxic T cells simulating panniculitis and preferentially infiltrating the subcutaneous tissue.1 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma can affect all ages but predominantly affects younger individuals, with 20% being younger than 20 years.2 It is a rare lymphoma that accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.3 It presents clinically as multiple subcutaneous masses, nodules, or plaques generally on the trunk or extremities.1,2 The skin surrounding the nodules may be erythematous, and the nodules may become necrotic; however, ulceration typically is not seen. Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and chills are present in half of cases.1 According to the World Health Organization, cytopenia and elevated liver function tests are common, and a hemophagocytic syndrome may be present in 15% to 20% of cases.3 The presence of a hemophagocytic syndrome yields a poor prognosis.1,3 Current guidelines denote that SPTCL T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ; is a distinct entity from the TCRγδ; phenotype, known as cutaneous γδ-positive T-cell lymphoma.3,4 Cutaneous γδ-positive T-cell lymphoma is associated with rapid decline and a worse prognosis.4

Histology of SPTCL is characteristic for a lobular panniculitislike infiltrate.1 The heavy subcutaneous lymphoid infiltrate is composed of atypical small- to medium-sized lymphocytes with mature chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli lining adipocytes. The dense inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of neoplastic T cells and macrophages may diffusely invade into the subcutaneous tissue.1 Admixed histocytes and karyorrhectic debris as well as rimming of the lymphocytes around the fat cells is typical and was seen in our patient (quiz image). The T cells of SPTCL have the following immunophenotype: TCR-beta F1+, CD3+, CD4-, CD8+, CD56-. They can express numerous cytotoxic proteins, such as T1a-1, granzyme B, and perforin.2,3 Although the CD8+ T cells may be sparse, they generally surround the adipocytes in a rimming manner and may distort the adipocyte membrane.1

Lupus erythematosus profundus (LEP) is a form of chronic cutaneous lupus that affects the deep dermis and fat.5 It also can present clinically as tender plaques or nodules. It most frequently involves the upper arms, shoulders, face, or buttocks--areas that are less commonly involved in other panniculitides.6 Histologically, LEP is similar to chronic discoid lupus with features such as epidermal atrophy, interface changes, and a thickened basement membrane (Figure 1). Lupus erythematosus profundus can present as a lobular panniculitis with mucin as well as a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate that can involve the septa.5 Some cases of LEP have a predominantly lobular lymphocytic panniculitis in the absence of the typical epidermal or dermal changes of lupus erythematosus. Lymphoid follicles with germinal center formation are present in half of cases and reportedly are characteristic of LEP.6,7 The lymphoid follicles often have plasma cells, can extend into the septa as well as in between collagen bundles, and may have nuclear fragmentation.5 Another characteristic feature of LEP is hyaline sclerosis of lobules with focal extension into the interlobular septa. Immunofluorescence studies usually show linear deposition of IgM and C3 at the dermoepidermal junction. Antinuclear antibodies can be present in patients who have LEP but are not entirely specific.6

Lupus erythematosus profundus and SPTCL are part of a spectrum and may have overlapping clinical and histopathologic characteristics; therefore, distinguishing them may be difficult.6-8 It is important to monitor these patients closely, as their disease may progress to lymphoma.6 Patients with SPTCL are more likely to present with advanced symptoms such as fever and hepatosplenomegaly and to succumb to hemophagocytic syndrome than patients with LEP.9

Although SPTCL usually is clonal, several cases of LEP with clonality also have been described. Clonal LEP cases generally are identified in patients who present with fever and cytopenia.8 Lymphoid atypia and morphologic abnormalities may be seen in cases of LEP, further complicating the distinction between LEP and SPTCL. An elevated Ki67 level may be seen in cases of SPTCL with periadipocytic rimming.9 LeBlanc et al10 used Ki67 "hot spots" along with CD8 immunohistochemistry to identify atypical lymphocytes associated with SPTCL. Lymphocyte rimming was defined by the presence of CD8+ lymphocytes with an elevated Ki67 index. Clinical, histopathologic, and molecular findings all should be used when dealing with challenging cases.

Fat necrosis can occur in any part of the body where trauma has occurred and can be associated with many disease processes. Patients typically present with a palpable mass, but a clinical history of trauma is not always present. Histopathologic findings include necrotic fat alongside lipid-laden foamy macrophages and scattered inflammatory cells (Figure 2).11 Fragments of normal as well as degenerating adipose tissue and multinucleated giant cells can be present.

Erythema nodosum (EN) is the most frequently encountered panniculitis and usually is seen in women in early adulthood.12 Patients present with several tender subcutaneous nodules and plaques that most commonly are present on the anterior surface of the legs.12,13 Patients may have a constellation of symptoms including fever and leukocytosis, but the disorder generally is self-limited.12 Erythema nodosum may be associated with a variety of diseases or infections including sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy.14 The etiology of EN is diverse; therefore, a proper clinical workup may be necessary. Histopathology is that of a septal panniculitis with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and occasional eosinophils (Figure 3).13

Lipodermatosclerosis also occurs on the legs, most commonly in patients with venous insufficiency.12,15 Patients present clinically with pain, induration, redness, or swelling of the legs. Histopathology predominantly is characterized by membranous fat necrosis, fibrosis, and fatty microcysts that may be lined by a thickened hyaline membrane (Figure 4). Lipodermatosclerosis lesions generally do not resolve spontaneously and may need to be treated.16

- Musick SR, Lynch DT. Subcutaneous Panniculitis Like T-cell Lymphoma. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Guenova E, Schanz S, Hoetzenecker W, et al. Systemic corticosteroids for subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:891-894.

- Swerdlow SH. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017.

- Bagheri F, Cervellione KL, Delgado B, et al. An illustrative case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [published online March 3, 2011]. J Skin Cancer. doi:10.1155/2011/824528

- Kogame T, Yamashita R, Hirata M, et al. Analysis of possible structures of inducible skin‐associated lymphoid tissue in lupus erythematosus profundus. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1117-1121.

- Arps DP, Patel RM. Lupus profundus (panniculitis): a potential mimic of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1211-1215.

- Alberti-Violetti S, Berti E. Lymphocytic lobular panniculitis: a diagnostic challenge. Dermatopathology. 2018;5:30-33.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN, Kovatich AJ, et al. Lupus profundus, indeterminate lymphocytic lobular panniculitis and subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a spectrum of subcuticular T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:235-247.

- Sitthinamsuwan P, Pattanaprichakul P, Treetipsatit J, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma versus lupus erythematosus panniculitis: distinction by means of the periadipocytic cell proliferation index. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:567-574.

- LeBlanc RE, Tavallaee M, Kim YH, et al. Useful parameters for distinguishing subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma from lupus erythematosus panniculitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:745-754.

- Burkholz KJ, Roberts CC, Lidner TK. Posttraumatic pseudolipoma (fat necrosis) mimicking atypical lipoma or liposarcoma on MRI. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;2:56-60.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Thurber S, Kohler S. Histopathologic spectrum of erythema nodosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:18-26.

- Requena L, Requena C. Erythema nodosum. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:4.

- Choonhakarn C, Chaowattanapanit S, Julanon N. Lipodermatosclerosis: a clinicopathologic correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:303-308.

- Huang TM, Lee JY. Lipodermatosclerosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases and differential diagnosis from erythema nodosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:453-460.

- Musick SR, Lynch DT. Subcutaneous Panniculitis Like T-cell Lymphoma. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Guenova E, Schanz S, Hoetzenecker W, et al. Systemic corticosteroids for subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:891-894.

- Swerdlow SH. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017.

- Bagheri F, Cervellione KL, Delgado B, et al. An illustrative case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [published online March 3, 2011]. J Skin Cancer. doi:10.1155/2011/824528

- Kogame T, Yamashita R, Hirata M, et al. Analysis of possible structures of inducible skin‐associated lymphoid tissue in lupus erythematosus profundus. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1117-1121.

- Arps DP, Patel RM. Lupus profundus (panniculitis): a potential mimic of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1211-1215.

- Alberti-Violetti S, Berti E. Lymphocytic lobular panniculitis: a diagnostic challenge. Dermatopathology. 2018;5:30-33.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN, Kovatich AJ, et al. Lupus profundus, indeterminate lymphocytic lobular panniculitis and subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a spectrum of subcuticular T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:235-247.

- Sitthinamsuwan P, Pattanaprichakul P, Treetipsatit J, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma versus lupus erythematosus panniculitis: distinction by means of the periadipocytic cell proliferation index. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:567-574.

- LeBlanc RE, Tavallaee M, Kim YH, et al. Useful parameters for distinguishing subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma from lupus erythematosus panniculitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:745-754.

- Burkholz KJ, Roberts CC, Lidner TK. Posttraumatic pseudolipoma (fat necrosis) mimicking atypical lipoma or liposarcoma on MRI. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;2:56-60.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Thurber S, Kohler S. Histopathologic spectrum of erythema nodosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:18-26.

- Requena L, Requena C. Erythema nodosum. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:4.

- Choonhakarn C, Chaowattanapanit S, Julanon N. Lipodermatosclerosis: a clinicopathologic correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:303-308.

- Huang TM, Lee JY. Lipodermatosclerosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases and differential diagnosis from erythema nodosum. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:453-460.

A 47-year-old man presented with a tender soft tissue mass on the upper back with increasing discomfort over the last 4 weeks. He noted that he felt feverish a few times. Physical examination revealed a 3×4-cm area of induration involving the upper mid back with faint erythema of the overlying skin; no drainage was noted. A prominent left posterior cervical lymph node also was appreciated, and a punch biopsy of the mass was performed.

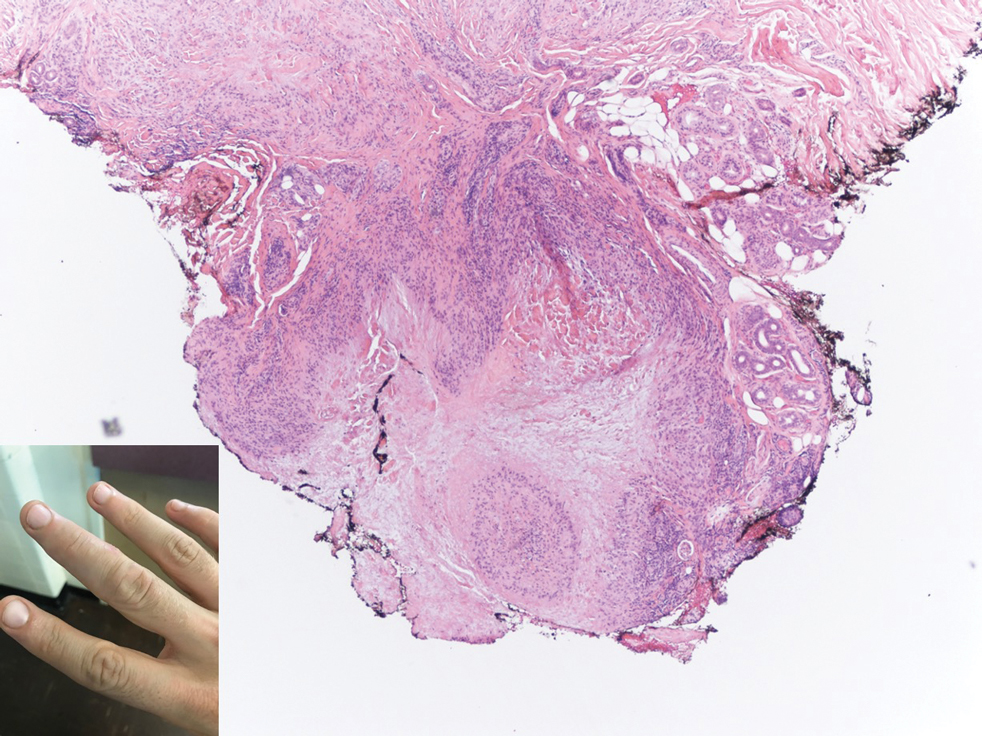

Multiple Nontender Subcutaneous Nodules on the Finger

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

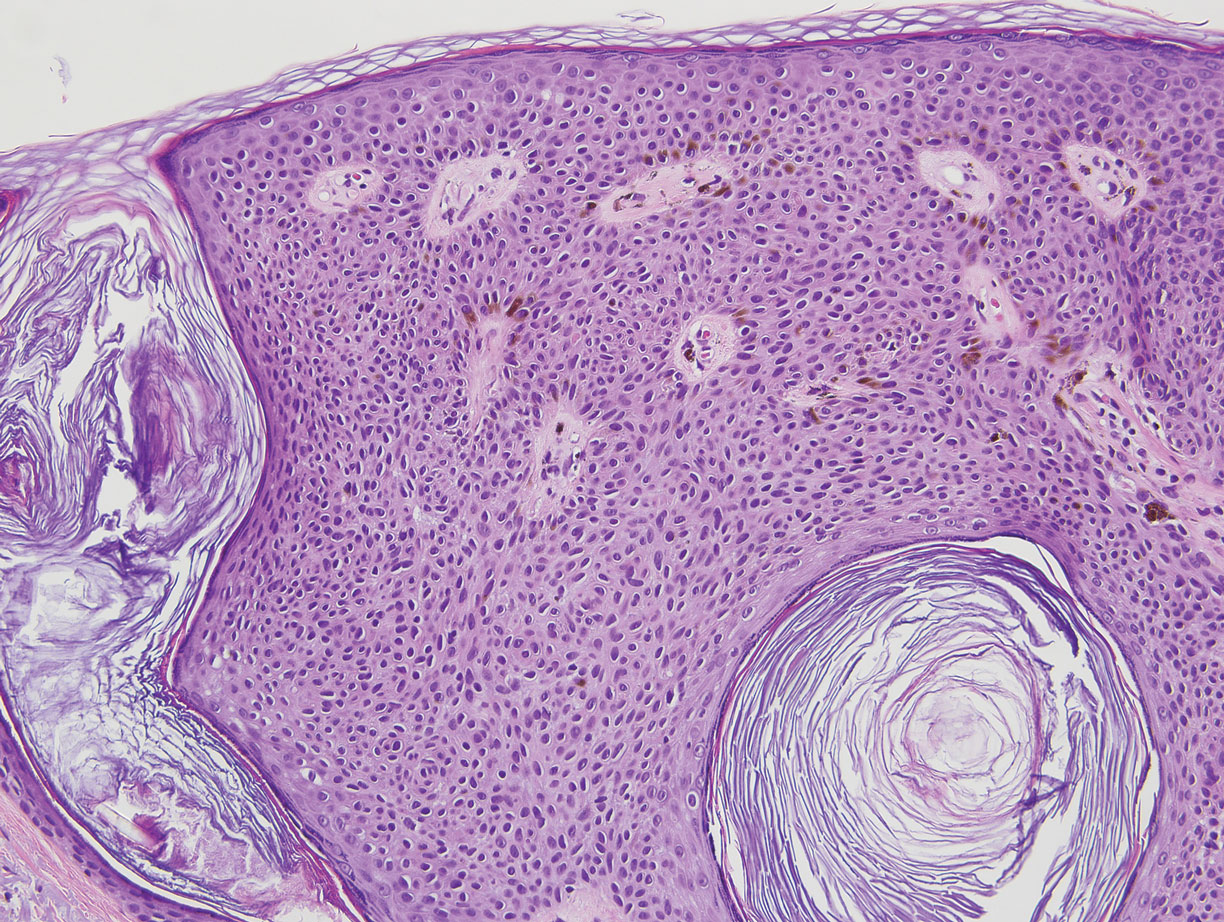

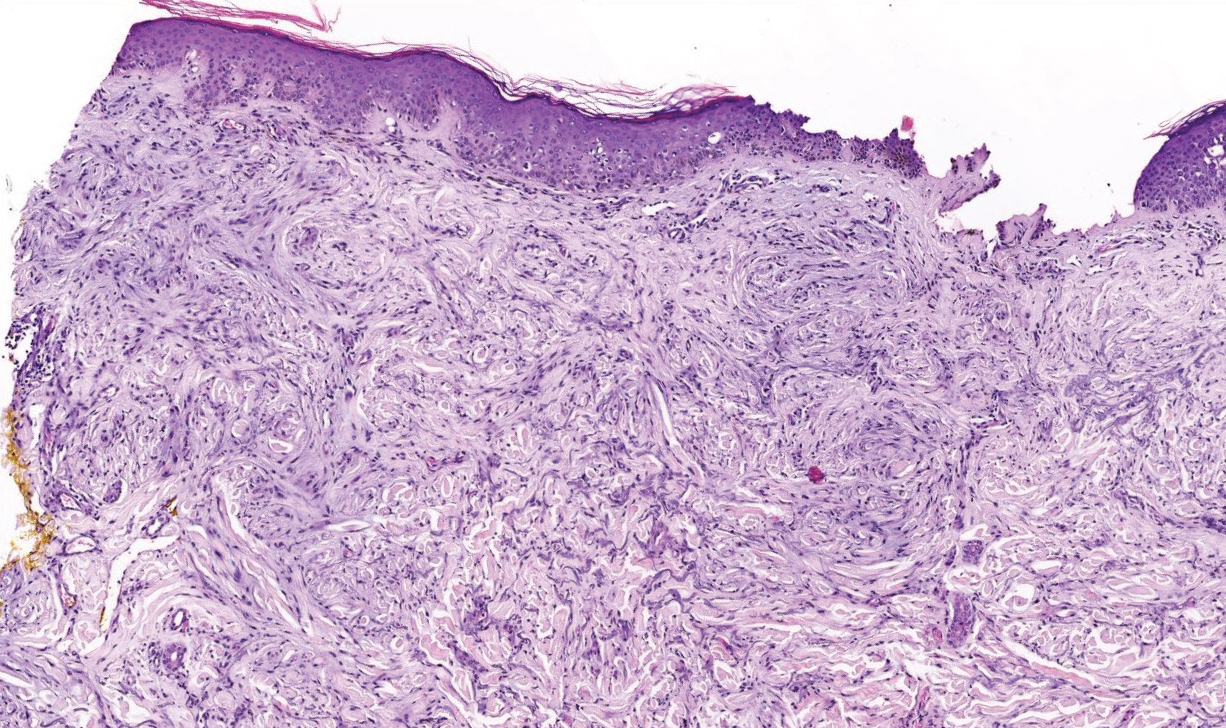

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

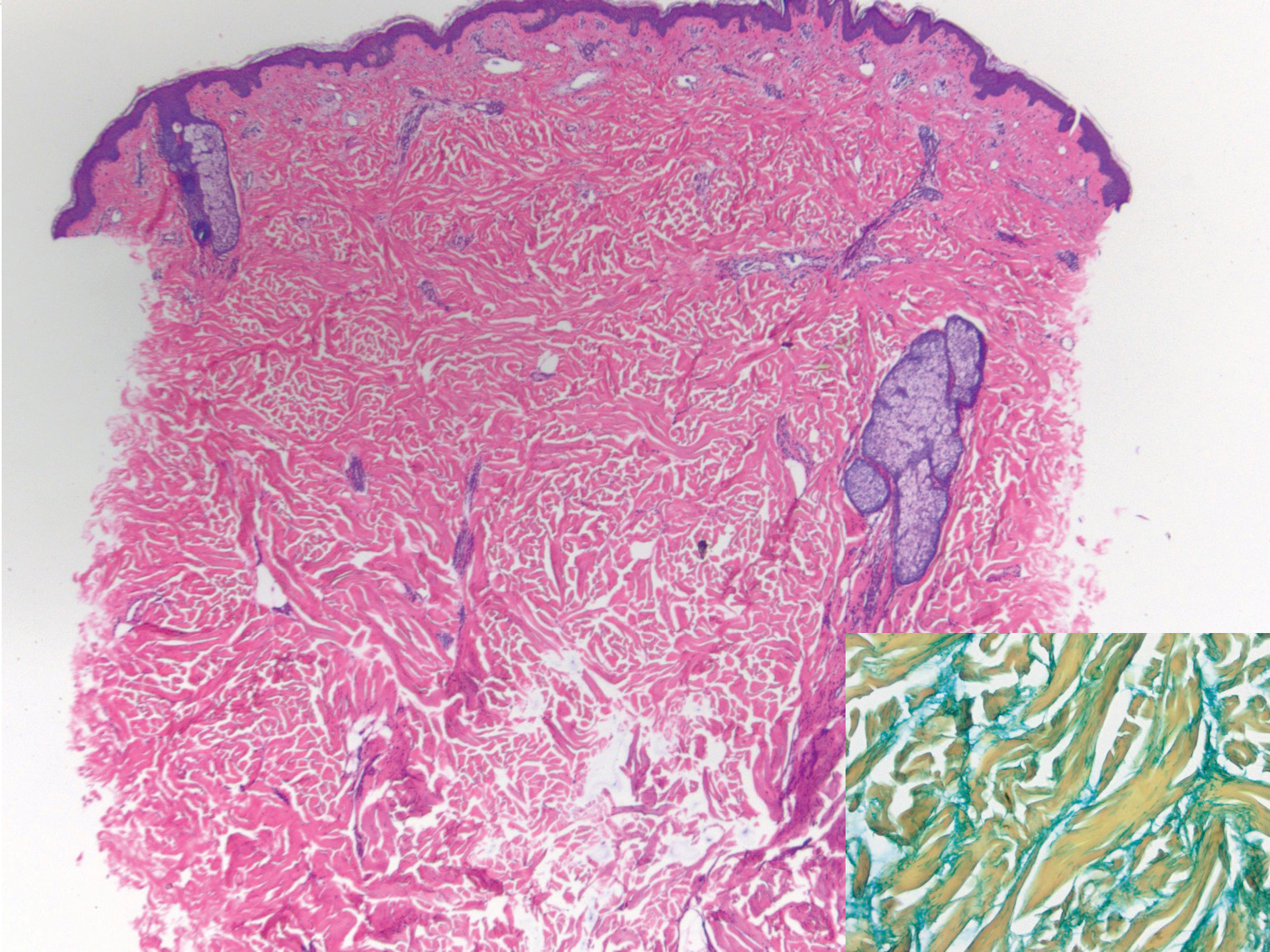

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

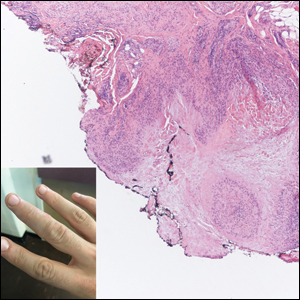

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

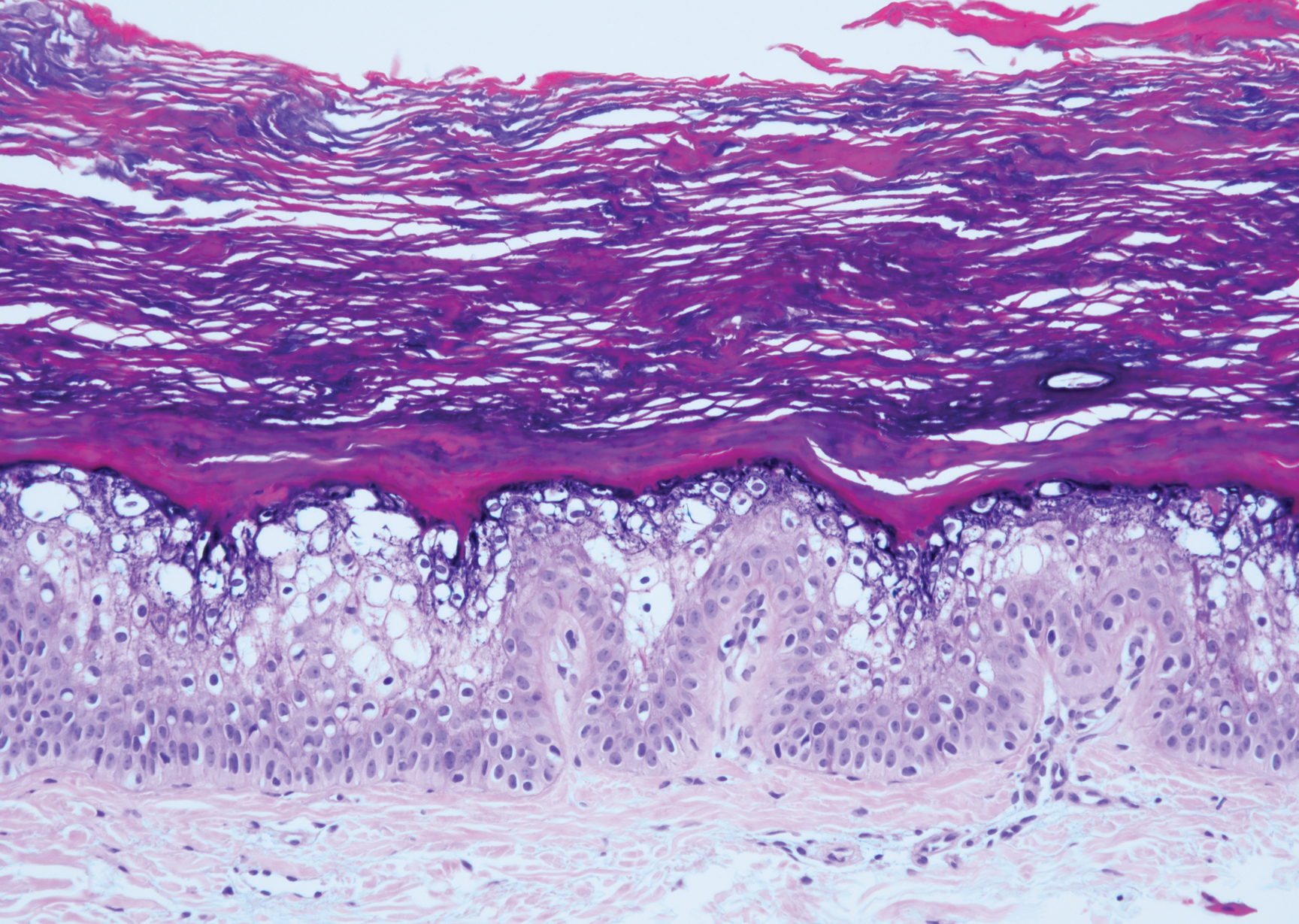

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

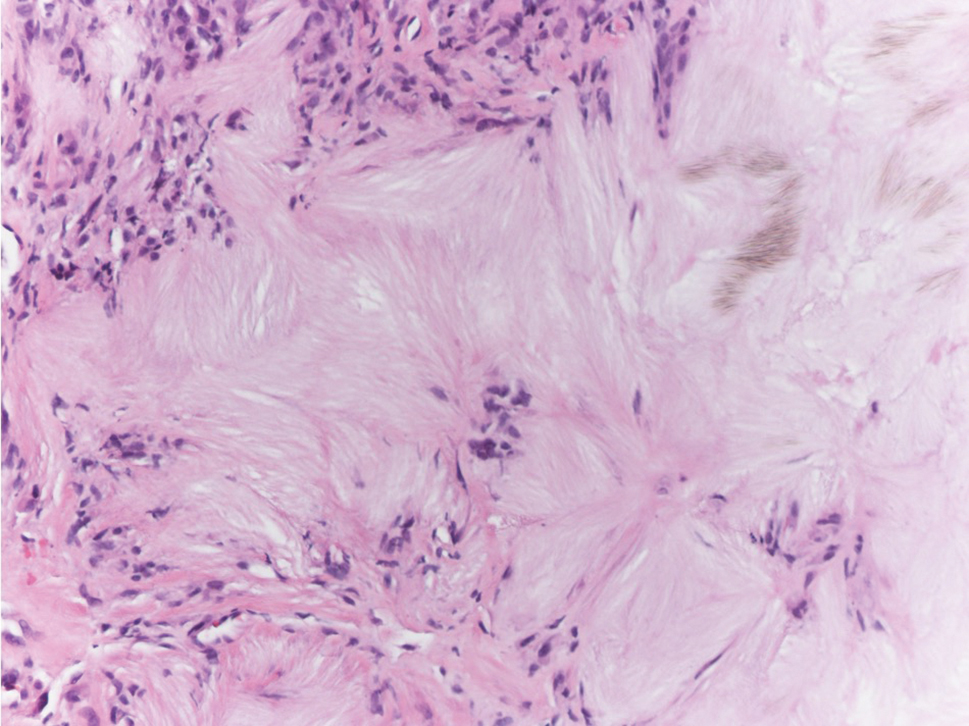

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

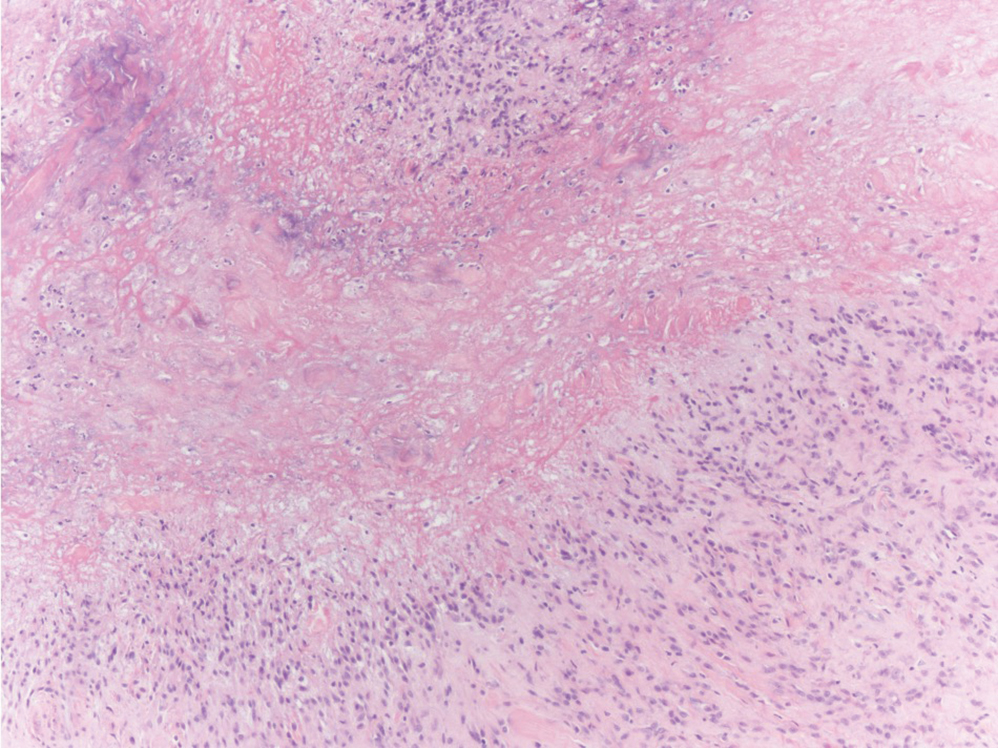

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Granuloma Annulare

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare (SGA), also known as deep GA, is a rare variant of GA that usually occurs in children and young adults. It presents as single or multiple, nontender, deep dermal and/or subcutaneous nodules with normal-appearing skin usually on the anterior lower legs, dorsal aspects of the hands and fingers, scalp, or buttocks.1-3 The pathogenesis of SGA as well as GA is not fully understood, and proposed inciting factors include trauma, insect bite reactions, tuberculin skin testing, vaccines, UV exposure, medications, and viral infections.3-6 A cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen also has been postulated as a possible mechanism.7 Treatment usually is not necessary, as the nature of the condition is benign and the course often is self-limited. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 2 years in 50% of patients with localized GA.4,8 Surgery usually is not recommended due to the high recurrence rate (40%-75%).4,9

Absence of epidermal change in this entity obfuscates clinical recognition, and accurate diagnosis often depends on punch or excisional biopsies revealing characteristic histopathology. The histology of SGA consists of palisaded granulomas with central areas of necrobiosis composed of degenerated collagen, mucin deposition, and nuclear dust from neutrophils that extend into the deep dermis and subcutis.2 The periphery of the granulomas is lined by palisading epithelioid histiocytes with occasional multinucleated giant cells.10,11 Eosinophils often are present.12 Colloidal iron and Alcian blue stains can be used to highlight the abundant connective tissue mucin of the granulomas.4

The histologic differential diagnosis of SGA includes rheumatoid nodule, necrobiosis lipoidica, epithelioid sarcoma, and tophaceous gout.2 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatologic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis and are found in up to 30% to 40% of patients with the disease.13-15 They present as firm, painless, subcutaneous papulonodules on the extensor surfaces and at sites of trauma or pressure. Histologically, rheumatoid nodules exhibit a homogenous and eosinophilic central area of necrobiosis with fibrin deposition and absent mucin deep within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). In contrast, granulomas in SGA usually are pale and basophilic with abundant mucin.2

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of the skin that most commonly occurs in young to middle-aged adults and is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus.16 It clinically presents as yellow to red-brown papules and plaques with a peripheral erythematous to violaceous rim usually on the pretibial area. Over time, lesions become yellowish atrophic patches and plaques that sometimes can ulcerate. Histopathology reveals areas of horizontally arranged, palisaded, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis intermixed with areas of degenerated collagen and widespread fibrosis extending from the superficial dermis into the subcutis (Figure 2).2 These areas lack mucin and have an increased number of plasma cells. Eosinophils and/or lymphoid nodules occasionally can be seen.17,18

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare malignant soft tissue sarcoma that tends to occur on the distal extremities in younger patients, typically aged 20 to 40 years, often with preceding trauma to the area. It usually presents as a solitary, poorly defined, hard, subcutaneous nodule. Histologic analysis shows central areas of necrosis and degenerated collagen surrounded by epithelioid and spindle cells with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei and mitoses (Figure 3).2 These tumor cells express positivity for keratins, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and CD34, while they usually are negative for desmin, S-100, and FLI-1 nuclear transcription factor.2,4,19

Tophaceous gout results from the accumulation of monosodium urate crystals in the skin. It clinically presents as firm, white-yellow, dermal and subcutaneous papulonodules on the helix of the ear and the skin overlying joints. Histopathology reveals palisaded granulomas surrounding an amorphous feathery material that corresponds to the urate crystals that were destroyed with formalin fixation (Figure 4). When the tissue is fixed with ethanol or is incompletely fixed in formalin, birefringent urate crystals are evident with polarization.20

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

- Felner EI, Steinberg JB, Weinberg AG. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a review of 47 cases. Pediatrics. 1997;100:965-967.

- Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:96-99.

- Taranu T, Grigorovici M, Constantin M, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:292-294.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare: a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Muhlbauer JE. Granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:217-230.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Wells RS, Smith MA. The natural history of granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 1963;75:199.

- Davids JR, Kolman BH, Billman GF, et al. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: recognition and treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:582-586.

- Evans MJ, Blessing K, Gray ES. Pseudorheumatoid nodule (deep granuloma annulare) of childhood: clinicopathologic features of twenty patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:6-9.

- Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare: a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

- Weedon D. Granuloma annulare. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill-Livingstone; 1997:167-170.

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209.

- Highton J, Hessian PA, Stamp L. The rheumatoid nodule: peripheral or central to rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1385-1387.

- Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:65-72.

- Erfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, et al. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:595-601.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK. A new histopathologic feature of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: lymphoid nodules. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:75-77.

- Armah HB, Parwani AV. Epithelioid sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:814-819.

- Shidham V, Chivukula M, Basir Z, et al. Evaluation of crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections for the differential diagnosis pseudogout, gout, and tumoral calcinosis. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:806-810.

Painful Papules on the Arms

The Diagnosis: Piloleiomyoma

Leiomyoma cutis, also known as cutaneous leiomyoma, is a benign smooth muscle tumor first described in 1854.1 Cutaneous leiomyoma is comprised of 3 distinct types that depend on the origin of smooth muscle tumor: piloleiomyoma (arrector pili muscle), angioleiomyoma (tunica media of arteries/veins), and genital leiomyoma (dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, erectile muscle of nipple).2 It affects both sexes equally, though some reports have noted an increased prevalence in females. Piloleiomyomas commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (solitary) and trunk (multiple).1 Tumors most often present as firm flesh-colored or pink-brown papulonodules. They can be linear, dermatomal, segmental, or diffuse, and often are painful. Clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors is aided by the acronym "BLEND AN EGG": blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor.3 For isolated lesions, surgical excision is the treatment of choice. For numerous lesions in which excision would not be feasible, intralesional corticosteroids, medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin), and botulinum toxin have been used for pain relief.4

Notably, multiple cutaneous leiomyomas can be seen in association with uterine leiomyomas in Reed syndrome due to an autosomal-dominant or de novo mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene, FH. Reed syndrome is associated with a lifetime risk for renal cell carcinoma (hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer) in 15% of cases with FH mutations.5 In our patient, both immunohistochemical staining and blood testing for FH were performed. Immunohistochemistry revealed notably diminished staining with only weak patchy granular cytoplasmic staining present (Figure 1). Genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathogenic variant of the FH gene, consistent with a diagnosis of Reed syndrome.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and dermatomyofibroma. The histologic appearance varies depending on the type, with piloleiomyoma typically located within the reticular dermis with possible subcutaneous extension. Fascicles of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells in an interlacing arrangement often ramify between neighboring dermal collagen; these smooth muscle cells contain cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei with a perinuclear clear vacuole. Marked epidermal hyperplasia is possible.6 A close association with a nearby hair follicle frequently is noted. Although differentiated smooth muscle cells usually are evident on hematoxylin and eosin, positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and desmin can aid in diagnosis.7 Immunohistochemical staining for FH has proven to be highly specific (97.6%) with moderate sensitivity (70.0%).8 Angioleiomyomas appear as well-demarcated dermal to subcutaneous tumors composed of smooth muscle cells surrounding thick-walled vaculature.9 Scrotal and vulvar leiomyomas are composed of eosinophilic spindle cells, though vulvar leiomyomas have shown epithelioid differentiation.10 Nipple leiomyomas appear similar to piloleiomyomas on histology with interlacing smooth muscle fiber bundles.

Eccrine spiradenoma is a relatively uncommon adnexal tumor derived from eccrine sweat glands. It most often presents as a small, painful or tender, intradermal nodule (or rarely as nodules) on the head or ventral trunk.11 There is no sexual predilection. It affects adults at any age but most often from 15 to 35 years. Although rare, malignant transformation is possible. Histologically, eccrine spiradenomas appear as a well-demarcated dermal tumor composed of bland basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm, often with numerous admixed lymphocytes and variably prominent vasculature (Figure 2). Eosinophilic basement membrane material can be seen within or surrounding the nodules of tumor cells. Multiple spiradenomas can occur in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to an inherited mutation in the CYLD gene. Spiradenomas are benign neoplasms, and surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice.12

Dermatofibroma, also known as cutaneous benign fibrous histiocytoma, is a firm, flesh-colored papule or nodule that most often presents on the lower extremities. It typically is seen in women aged 20 to 40 years.13 The etiology is uncertain, and dermatofibromas often spontaneously develop, though there are inconsistent reports of development with local trauma including insect bites and puncture wounds. The dimple sign refers to skin dimpling with lateral pressure.13 Most commonly, dermatofibromas consist of a dermal proliferation of bland fibroblastic cells with entrapment of dermal collagen bundles at the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3). The fibroblastic cells often are paler and less eosinophilic than smooth muscle cells seen in cutaneous leiomyomas, with tapered nuclei that lack a perinuclear vacuole. Admixed histocytes and other inflammatory cells often are present. Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and/or hyperpigmentation also may be present. Numerous histologic variants have been described, including cellular, epithelioid, aneurysmal, atypical, and hemosiderotic types.14 Immunohistochemical stains may show patchy positive staining for SMA, but h-caldesmon and desmin typically are negative.

Neurofibroma is a tumor derived from neuromesenchymal tissue with nerve axons. They form through neuromesenchyme (eg, Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, endoneural fibroblast) proliferation. Solitary neurofibromas occur most commonly in adults and have no gender predilection. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic, solitary, soft, flesh-colored papulonodule.15 Clinical variants include pigmented, diffuse, and plexiform, with plexiform neurofibromas almost always being consistent with a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Histologically, neurofibromas present as dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of randomly arranged spindle cells with wavy tapered nuclei within a loose collagenous stroma (Figure 4).16 The spindle cells in neurofibromas will stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 and negatively for SMA and desmin.

Angiolipoma is a benign tumor composed of adipocytes that also contains vasculature.17 The majority of cases are of unknown etiology, though familial cases have been described. They typically present as multiple painful or tender (differentiating from lipomas) subcutaneous swellings over the forearms in individuals aged 20 to 30 years.18 On histopathology, angiolipomas appear as well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumors containing mature adipocytes intermixed with small capillary vessels, some of which contain luminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 5).

- Malik K, Patel P, Chen J, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:35-46.

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Delfino S, Toto V, Brunetti B, et al. Recurrent atypical eccrine spiradenoma of the forehead. In Vivo. 2008;22:821-823.

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Choi JH, Ro JY. Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:958-972.