User login

LISTEN NOW: Kristen Kulasa, MD, Explains How Hospitalists Can Work with Nutritionists and Dieticians

Kristen Kulasa, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine and director of Inpatient Glycemic Control, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at the University of California in San Diego, provides tips on how hospitalists can work with nutritionists and dieticians for the betterment of diabetic patients. As a mentor for SHM's care coordination program on inpatient diabetes, Dr. Kulasa offers hospitalists advice in treating diabetic patients. She points to SHM’s website, which has a lot of resources to help hospitalists feel comfortable with insulin dosing.

Kristen Kulasa, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine and director of Inpatient Glycemic Control, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at the University of California in San Diego, provides tips on how hospitalists can work with nutritionists and dieticians for the betterment of diabetic patients. As a mentor for SHM's care coordination program on inpatient diabetes, Dr. Kulasa offers hospitalists advice in treating diabetic patients. She points to SHM’s website, which has a lot of resources to help hospitalists feel comfortable with insulin dosing.

Kristen Kulasa, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine and director of Inpatient Glycemic Control, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at the University of California in San Diego, provides tips on how hospitalists can work with nutritionists and dieticians for the betterment of diabetic patients. As a mentor for SHM's care coordination program on inpatient diabetes, Dr. Kulasa offers hospitalists advice in treating diabetic patients. She points to SHM’s website, which has a lot of resources to help hospitalists feel comfortable with insulin dosing.

LISTEN NOW: Dr. Carolyn Zelop, MD, Discusses Cardiovascular Emergencies in Pregnant Women

Listen now to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Zelop, a board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J.

Listen now to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Zelop, a board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J.

Listen now to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Zelop, a board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J.

Insulin Rules in the Hospital

Although new medications to manage and treat hyperglycemia and diabetes continuously appear on the market, national guidelines and position statements consistently refer to insulin as the treatment of choice in the inpatient hospital setting.

“When patients are admitted to the hospital, our standard is to switch from the outpatient regimen [wide variety of medications] to the inpatient regimen—insulin,” says Paul M. Szumita, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy practice manager director at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

For critically ill patients in ICUs or during the peri-operative period, intravenous infusion of insulin is preferred. Most general medicine and surgery patients are managed with subcutaneous insulin.

“Using a basal bolus regimen starting at a total daily dose of 0.3-0.5 unit/kg is sufficient for most patients,” says Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, CDE, FCAE, FACP, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga., and a member of the board of directors for the American Diabetes Association; however, for most general medicine and surgical patients who have low oral intake or are NPO, a recent trial reported that the administration of basal insulin alone plus correction doses with rapid-acting insulin analogs before meals is as good as a basal bolus regimen. A regimen should be tweaked throughout the inpatient’s stay with an aim to reach the goal of minimal or no hypoglycemia.1

Planning for a discharge regimen should start early in the hospital stay, Dr. Szumita says, and should be based on several factors:

- The patient’s Hb1c;

- The prior regimen and how it was performing;

- The patient’s wishes; and

- Collaboration with outpatient providers.

At discharge, it is critical that patients be clear about what medications they should be on post-discharge and that they follow-up with outpatient providers in a timely manner. TH

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

Reference

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Hermayer K, et al. Randomized study comparing a basal-bolus with a basal plus correction insulin regimen for the hospital management of medical and surgical patients with type 2 diabetes: basal plus trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2169-2174.

Although new medications to manage and treat hyperglycemia and diabetes continuously appear on the market, national guidelines and position statements consistently refer to insulin as the treatment of choice in the inpatient hospital setting.

“When patients are admitted to the hospital, our standard is to switch from the outpatient regimen [wide variety of medications] to the inpatient regimen—insulin,” says Paul M. Szumita, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy practice manager director at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

For critically ill patients in ICUs or during the peri-operative period, intravenous infusion of insulin is preferred. Most general medicine and surgery patients are managed with subcutaneous insulin.

“Using a basal bolus regimen starting at a total daily dose of 0.3-0.5 unit/kg is sufficient for most patients,” says Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, CDE, FCAE, FACP, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga., and a member of the board of directors for the American Diabetes Association; however, for most general medicine and surgical patients who have low oral intake or are NPO, a recent trial reported that the administration of basal insulin alone plus correction doses with rapid-acting insulin analogs before meals is as good as a basal bolus regimen. A regimen should be tweaked throughout the inpatient’s stay with an aim to reach the goal of minimal or no hypoglycemia.1

Planning for a discharge regimen should start early in the hospital stay, Dr. Szumita says, and should be based on several factors:

- The patient’s Hb1c;

- The prior regimen and how it was performing;

- The patient’s wishes; and

- Collaboration with outpatient providers.

At discharge, it is critical that patients be clear about what medications they should be on post-discharge and that they follow-up with outpatient providers in a timely manner. TH

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

Reference

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Hermayer K, et al. Randomized study comparing a basal-bolus with a basal plus correction insulin regimen for the hospital management of medical and surgical patients with type 2 diabetes: basal plus trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2169-2174.

Although new medications to manage and treat hyperglycemia and diabetes continuously appear on the market, national guidelines and position statements consistently refer to insulin as the treatment of choice in the inpatient hospital setting.

“When patients are admitted to the hospital, our standard is to switch from the outpatient regimen [wide variety of medications] to the inpatient regimen—insulin,” says Paul M. Szumita, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy practice manager director at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

For critically ill patients in ICUs or during the peri-operative period, intravenous infusion of insulin is preferred. Most general medicine and surgery patients are managed with subcutaneous insulin.

“Using a basal bolus regimen starting at a total daily dose of 0.3-0.5 unit/kg is sufficient for most patients,” says Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, CDE, FCAE, FACP, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga., and a member of the board of directors for the American Diabetes Association; however, for most general medicine and surgical patients who have low oral intake or are NPO, a recent trial reported that the administration of basal insulin alone plus correction doses with rapid-acting insulin analogs before meals is as good as a basal bolus regimen. A regimen should be tweaked throughout the inpatient’s stay with an aim to reach the goal of minimal or no hypoglycemia.1

Planning for a discharge regimen should start early in the hospital stay, Dr. Szumita says, and should be based on several factors:

- The patient’s Hb1c;

- The prior regimen and how it was performing;

- The patient’s wishes; and

- Collaboration with outpatient providers.

At discharge, it is critical that patients be clear about what medications they should be on post-discharge and that they follow-up with outpatient providers in a timely manner. TH

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

Reference

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Hermayer K, et al. Randomized study comparing a basal-bolus with a basal plus correction insulin regimen for the hospital management of medical and surgical patients with type 2 diabetes: basal plus trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2169-2174.

The Increasing Presence of Pregnant Patients in Hospital Medicine

Twenty years ago, pregnant women rarely appeared in the hospital for reasons other than delivery. Two trends responsible for that shift are advanced maternal age and rising rates of obesity, defined as a body mass index of >30.

The birth rate for women ages 35-44 has continued to rise, and that has brought new challenges to treating pregnancy, many of which result in hospital visits.1

OB/GYN hospitalist Robert Olson, MD, SFHM, has witnessed the winds of change firsthand. “Older patients are more likely to have medical conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, as well as the unusual medical problems such as status post heart attack, status post heart transplant, status post chemotherapy for cancer, as well as being on medications for chronic disease,” says Dr. Olson, who practices in Bellingham, Wash., and is the founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, more than one third of U.S. women are obese and more than half of all pregnant women are overweight or obese and therefore prone to complications that send them to the hospital, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia.3

As an inpatient, obese pregnant women present their own challenges, including increased risk of thromboembolism. When treating this type of patient, remember pneumatic compression devices are recommended if the patient will be immobile for any length of time.4

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Clinicians might also have significant difficulty intubating the overweight mother-to-be. Whether for cesarean section, other surgical procedures, or an acute medical crisis, physicians must approach intubation with caution as a result of excessive adipose tissue, obscured landmarks, difficulty positioning, and edema, as well as progesterone-induced relaxation of the sphincter between the esophagus and stomach.5 It is vital to make use of your most experienced staff when intubating this special needs patient. TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist, PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. E-mail interview. November 13, 2013.

- Leddy MA, Power ML, Schulkin J. The impact of maternal obesity on maternal and fetal health. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(4):170-178.

- ACOG committee opinion number 549. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):213-217.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

Twenty years ago, pregnant women rarely appeared in the hospital for reasons other than delivery. Two trends responsible for that shift are advanced maternal age and rising rates of obesity, defined as a body mass index of >30.

The birth rate for women ages 35-44 has continued to rise, and that has brought new challenges to treating pregnancy, many of which result in hospital visits.1

OB/GYN hospitalist Robert Olson, MD, SFHM, has witnessed the winds of change firsthand. “Older patients are more likely to have medical conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, as well as the unusual medical problems such as status post heart attack, status post heart transplant, status post chemotherapy for cancer, as well as being on medications for chronic disease,” says Dr. Olson, who practices in Bellingham, Wash., and is the founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, more than one third of U.S. women are obese and more than half of all pregnant women are overweight or obese and therefore prone to complications that send them to the hospital, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia.3

As an inpatient, obese pregnant women present their own challenges, including increased risk of thromboembolism. When treating this type of patient, remember pneumatic compression devices are recommended if the patient will be immobile for any length of time.4

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Clinicians might also have significant difficulty intubating the overweight mother-to-be. Whether for cesarean section, other surgical procedures, or an acute medical crisis, physicians must approach intubation with caution as a result of excessive adipose tissue, obscured landmarks, difficulty positioning, and edema, as well as progesterone-induced relaxation of the sphincter between the esophagus and stomach.5 It is vital to make use of your most experienced staff when intubating this special needs patient. TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist, PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. E-mail interview. November 13, 2013.

- Leddy MA, Power ML, Schulkin J. The impact of maternal obesity on maternal and fetal health. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(4):170-178.

- ACOG committee opinion number 549. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):213-217.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

Twenty years ago, pregnant women rarely appeared in the hospital for reasons other than delivery. Two trends responsible for that shift are advanced maternal age and rising rates of obesity, defined as a body mass index of >30.

The birth rate for women ages 35-44 has continued to rise, and that has brought new challenges to treating pregnancy, many of which result in hospital visits.1

OB/GYN hospitalist Robert Olson, MD, SFHM, has witnessed the winds of change firsthand. “Older patients are more likely to have medical conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, as well as the unusual medical problems such as status post heart attack, status post heart transplant, status post chemotherapy for cancer, as well as being on medications for chronic disease,” says Dr. Olson, who practices in Bellingham, Wash., and is the founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, more than one third of U.S. women are obese and more than half of all pregnant women are overweight or obese and therefore prone to complications that send them to the hospital, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia.3

As an inpatient, obese pregnant women present their own challenges, including increased risk of thromboembolism. When treating this type of patient, remember pneumatic compression devices are recommended if the patient will be immobile for any length of time.4

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Clinicians might also have significant difficulty intubating the overweight mother-to-be. Whether for cesarean section, other surgical procedures, or an acute medical crisis, physicians must approach intubation with caution as a result of excessive adipose tissue, obscured landmarks, difficulty positioning, and edema, as well as progesterone-induced relaxation of the sphincter between the esophagus and stomach.5 It is vital to make use of your most experienced staff when intubating this special needs patient. TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist, PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. E-mail interview. November 13, 2013.

- Leddy MA, Power ML, Schulkin J. The impact of maternal obesity on maternal and fetal health. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1(4):170-178.

- ACOG committee opinion number 549. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):213-217.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

Evidence-Based Medicine Guru Implores Hospitalists to Join Cause

Gordon Guyatt, MD, who coined the term evidence-based medicine in a 1992 JAMA article, outlined EBM principles and challenged hospitalists to challenge the research.

Gordon Guyatt, MD, who coined the term evidence-based medicine in a 1992 JAMA article, outlined EBM principles and challenged hospitalists to challenge the research.

Gordon Guyatt, MD, who coined the term evidence-based medicine in a 1992 JAMA article, outlined EBM principles and challenged hospitalists to challenge the research.

Hospitalists Flock to Annual Meeting's Bedside Procedures Pre-Courses

From early-career hospitalists looking to gain hands-on experience with intraosseous lines to family-medicine trained physicians brushing up on ultrasound usage, the procedures' pre-courses at SHM annual meetings receive rave reviews.

From early-career hospitalists looking to gain hands-on experience with intraosseous lines to family-medicine trained physicians brushing up on ultrasound usage, the procedures' pre-courses at SHM annual meetings receive rave reviews.

From early-career hospitalists looking to gain hands-on experience with intraosseous lines to family-medicine trained physicians brushing up on ultrasound usage, the procedures' pre-courses at SHM annual meetings receive rave reviews.

Room for Improvement in Identifying, Treating Sepsis

Despite huge strides in the treatment of heart failure, pneumonia and myocardial infarction, hospitals have a long way to go in improving care for patients with sepsis, say the authors of a recent commentary published online in JAMA.

In a related study published in July in JAMA, sepsis was found to contribute to one in every two to three hospital deaths based on mortality results from two independent patient cohorts measured between 2010 and 2012. Additionally, most instances of sepsis were present upon admission, the report notes.

For their part, hospitalists should focus on identifying the signs and symptoms of sepsis early, according to study authors Colin R. Cooke, MD, MSc, MS, and Theodore J. Iwashyna, MD, PhD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

"When patients are admitted for an illness such as pneumonia, we put them in a bin where we know how to treat patients with pneumonia, but we may fail to recognize when they meet the criteria for sepsis," Dr. Cooke says. "If we can recognize a patient has sepsis, then we can get on top of the illness faster by delivering antibiotics and also ensuring the patient gets fluid resuscitation early in the course of the disease."

In their JAMA article, Dr. Cooke and Dr. Iwashyna call on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop quality mandates that would encourage hospitals to share best practices in treating sepsis. The mandates, however, shouldn't include financial penalties, which the authors say "would create perverse incentives to not report delayed diagnosis of sepsis rather than address the problem."

Visit our website for more information on identifying sepsis in hospitalized patients.

Despite huge strides in the treatment of heart failure, pneumonia and myocardial infarction, hospitals have a long way to go in improving care for patients with sepsis, say the authors of a recent commentary published online in JAMA.

In a related study published in July in JAMA, sepsis was found to contribute to one in every two to three hospital deaths based on mortality results from two independent patient cohorts measured between 2010 and 2012. Additionally, most instances of sepsis were present upon admission, the report notes.

For their part, hospitalists should focus on identifying the signs and symptoms of sepsis early, according to study authors Colin R. Cooke, MD, MSc, MS, and Theodore J. Iwashyna, MD, PhD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

"When patients are admitted for an illness such as pneumonia, we put them in a bin where we know how to treat patients with pneumonia, but we may fail to recognize when they meet the criteria for sepsis," Dr. Cooke says. "If we can recognize a patient has sepsis, then we can get on top of the illness faster by delivering antibiotics and also ensuring the patient gets fluid resuscitation early in the course of the disease."

In their JAMA article, Dr. Cooke and Dr. Iwashyna call on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop quality mandates that would encourage hospitals to share best practices in treating sepsis. The mandates, however, shouldn't include financial penalties, which the authors say "would create perverse incentives to not report delayed diagnosis of sepsis rather than address the problem."

Visit our website for more information on identifying sepsis in hospitalized patients.

Despite huge strides in the treatment of heart failure, pneumonia and myocardial infarction, hospitals have a long way to go in improving care for patients with sepsis, say the authors of a recent commentary published online in JAMA.

In a related study published in July in JAMA, sepsis was found to contribute to one in every two to three hospital deaths based on mortality results from two independent patient cohorts measured between 2010 and 2012. Additionally, most instances of sepsis were present upon admission, the report notes.

For their part, hospitalists should focus on identifying the signs and symptoms of sepsis early, according to study authors Colin R. Cooke, MD, MSc, MS, and Theodore J. Iwashyna, MD, PhD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

"When patients are admitted for an illness such as pneumonia, we put them in a bin where we know how to treat patients with pneumonia, but we may fail to recognize when they meet the criteria for sepsis," Dr. Cooke says. "If we can recognize a patient has sepsis, then we can get on top of the illness faster by delivering antibiotics and also ensuring the patient gets fluid resuscitation early in the course of the disease."

In their JAMA article, Dr. Cooke and Dr. Iwashyna call on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop quality mandates that would encourage hospitals to share best practices in treating sepsis. The mandates, however, shouldn't include financial penalties, which the authors say "would create perverse incentives to not report delayed diagnosis of sepsis rather than address the problem."

Visit our website for more information on identifying sepsis in hospitalized patients.

Primary-Care Physicians Weigh in on Quality of Care Transitions

A new study on transitions of care gives hospitalists a view from the other side.

Published recently online in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the authors surveyed 22 primary-care physician leaders in California-based post-discharge clinics and asked them about ways to improve care transitions.

Physicians' responses focused on several areas that need work, most notably aligned financial incentives, regulations to standardize interoperability among electronic health records (EHR) and data sharing, and more opportunities for professional networking, the authors note.

Although the qualitative study takes a broad view of the healthcare system, its lead author says hospitalists should view "systems change" as a long-term goal achievable via incremental improvements that can start now.

"National policy change is needed to move the needle for the whole health system," says hospitalist Oanh Kieu Nguyen, MD, MAS, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. "But locally, you can innovate within these domains and start to make changes to improve practice settings more immediately. National policy to align financial incentives and improve EHR interoperability will be key to helping local changes take hold and spread across systems. Otherwise, there will continue to be a lot of variability and fragmentation around care transitions on a national level."

Dr. Nguyen, who has practiced as both a hospitalist and PCP, says that because policies and studies on post-discharge care transitions primarily have focused on the hospital perspective, it is important to gain an understanding of the primary-care point of view.

"As a hospitalist, it's really easy to get caught up in just wanting to get patients teed up and sent home. Once they're out, we think they're no longer really our problem," Dr. Nguyen adds. "It's easy to forget that primary care is an important part of the other side of the equation. The way our healthcare system is designed doesn't really give physicians an incentive to look at the whole picture of a patient across all the environments they're in."

Many hospitalists are sharing their challenges and successes in care transitions through HMX. Join the conversation now.

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

A new study on transitions of care gives hospitalists a view from the other side.

Published recently online in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the authors surveyed 22 primary-care physician leaders in California-based post-discharge clinics and asked them about ways to improve care transitions.

Physicians' responses focused on several areas that need work, most notably aligned financial incentives, regulations to standardize interoperability among electronic health records (EHR) and data sharing, and more opportunities for professional networking, the authors note.

Although the qualitative study takes a broad view of the healthcare system, its lead author says hospitalists should view "systems change" as a long-term goal achievable via incremental improvements that can start now.

"National policy change is needed to move the needle for the whole health system," says hospitalist Oanh Kieu Nguyen, MD, MAS, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. "But locally, you can innovate within these domains and start to make changes to improve practice settings more immediately. National policy to align financial incentives and improve EHR interoperability will be key to helping local changes take hold and spread across systems. Otherwise, there will continue to be a lot of variability and fragmentation around care transitions on a national level."

Dr. Nguyen, who has practiced as both a hospitalist and PCP, says that because policies and studies on post-discharge care transitions primarily have focused on the hospital perspective, it is important to gain an understanding of the primary-care point of view.

"As a hospitalist, it's really easy to get caught up in just wanting to get patients teed up and sent home. Once they're out, we think they're no longer really our problem," Dr. Nguyen adds. "It's easy to forget that primary care is an important part of the other side of the equation. The way our healthcare system is designed doesn't really give physicians an incentive to look at the whole picture of a patient across all the environments they're in."

Many hospitalists are sharing their challenges and successes in care transitions through HMX. Join the conversation now.

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

A new study on transitions of care gives hospitalists a view from the other side.

Published recently online in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the authors surveyed 22 primary-care physician leaders in California-based post-discharge clinics and asked them about ways to improve care transitions.

Physicians' responses focused on several areas that need work, most notably aligned financial incentives, regulations to standardize interoperability among electronic health records (EHR) and data sharing, and more opportunities for professional networking, the authors note.

Although the qualitative study takes a broad view of the healthcare system, its lead author says hospitalists should view "systems change" as a long-term goal achievable via incremental improvements that can start now.

"National policy change is needed to move the needle for the whole health system," says hospitalist Oanh Kieu Nguyen, MD, MAS, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. "But locally, you can innovate within these domains and start to make changes to improve practice settings more immediately. National policy to align financial incentives and improve EHR interoperability will be key to helping local changes take hold and spread across systems. Otherwise, there will continue to be a lot of variability and fragmentation around care transitions on a national level."

Dr. Nguyen, who has practiced as both a hospitalist and PCP, says that because policies and studies on post-discharge care transitions primarily have focused on the hospital perspective, it is important to gain an understanding of the primary-care point of view.

"As a hospitalist, it's really easy to get caught up in just wanting to get patients teed up and sent home. Once they're out, we think they're no longer really our problem," Dr. Nguyen adds. "It's easy to forget that primary care is an important part of the other side of the equation. The way our healthcare system is designed doesn't really give physicians an incentive to look at the whole picture of a patient across all the environments they're in."

Many hospitalists are sharing their challenges and successes in care transitions through HMX. Join the conversation now.

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

Physician Tips Help Hone Clinicians' Practice Management, Decision-Making Skills

EDITOR’S NOTE: Second in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

The third installment in the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series, Becoming a Consummate Clinician is written in two parts. Part 1, “Medical Musts and Must-Nots,” is focused on the basics of being a clinician: gathering an appropriate history, performing an effective physical examination, and formulating differential diagnoses. This section in particular is geared toward house officers and attending physicians on teaching teams. While the audience here is primarily clinicians on a teaching service, there is good advice for those in any practice setting about avoiding common mistakes and developing clinical sagacity.

In this first section, we are given advisement on treatment of and with medications. Regardless of a clinician’s level of experience, it is worth reading this text to review and internalize these authors’ advice regarding medication pitfalls. Simply putting this advice into one’s daily practice of medicine will take any practitioner a long way toward becoming a “consummate clinician.”

Part 2, “Medical Masteries,” logically builds upon material presented in Part 1. The final section of the book addresses aspects of critical analysis of medical data and encourages engagement of critical thinking skills in all aspects of clinical decision-making. Specific topics addressed include reducing medical errors, reevaluating evidence-based medicine, deconstructing several widely cited medical aphorisms, identifying sources of cognitive errors, and transforming information into understanding.

The authors devoted the final chapter to the discussion of “What is disease?” and “What is health?” which, quite frankly, adds little value to the book.

Drs. Goldberger and Goldberger discuss what they term the “interstitial curriculum”—what is not explicitly taught but should be. Included in the “interstitial curriculum” is examination of cognitive errors and how we are more apt to make these in the era of “high-throughput” patient care. Another topic included in their “interstitial curriculum” is the paucity of attention paid to addressing uncertainty in all aspects of medicine. These topics are worth the cost of this book, even if it only helps promote awareness of these important ideas and bring the discussion to a larger audience.

The complementary processes of constantly rethinking assumptions, researching information, and reformulating basic mechanisms are fundamental to practicing all types of medicine successfully. Such processes also help to avoid potentially lethal errors and help to rigorously and compassionately advance the inseparable sciences of prevention and healing. The deep and multidimensional challenges are central to the ongoing pursuit of becoming the consummate clinician.”

Analysis

There are times in this book, particularly in the beginning, when the reader feels this text was written for the benefit of the house officer and those practitioners serving on inpatient teaching services. Continued reading, however, finds brilliant advice for clinicians in all practice settings and in all stages of their careers.

The encouragement of all readers to rethink everything we assume to be true and to seek a deeper understanding of what we “know” is priceless.

The quotes included throughout the book were both valuable and enjoyable. The authors included quotes from Plutarch to Hector Barbosa from Pirates of the Caribbean. One quote that is particularly germane to the practice of hospital medicine in this age of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems comes from Sir William Osler:

“Remember…that every patient upon whom you wait will examine you critically and form an estimate of you by the way in which you conduct yourself at the bedside. Skill and nicety in manipulation, in the simple act of feeling the pulse or in the performance of any minor operation, will do more towards establishing confidence in you than a string of diplomas, or the reputation of extensive hospital experience.”

Conversely, the computer-generated graphics added no value and were, in fact, a detractor. Hopefully, the next edition will not feature the sophomorically rendered bridge advising us to “bridge the classroom-to-clinic gap,” the flamingo, or the zigzagging line, among others.

Dr. Lindsey is chief operations officer and strategist of Synergy Surgicalists, and a member of Team Hospitalist.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Second in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

The third installment in the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series, Becoming a Consummate Clinician is written in two parts. Part 1, “Medical Musts and Must-Nots,” is focused on the basics of being a clinician: gathering an appropriate history, performing an effective physical examination, and formulating differential diagnoses. This section in particular is geared toward house officers and attending physicians on teaching teams. While the audience here is primarily clinicians on a teaching service, there is good advice for those in any practice setting about avoiding common mistakes and developing clinical sagacity.

In this first section, we are given advisement on treatment of and with medications. Regardless of a clinician’s level of experience, it is worth reading this text to review and internalize these authors’ advice regarding medication pitfalls. Simply putting this advice into one’s daily practice of medicine will take any practitioner a long way toward becoming a “consummate clinician.”

Part 2, “Medical Masteries,” logically builds upon material presented in Part 1. The final section of the book addresses aspects of critical analysis of medical data and encourages engagement of critical thinking skills in all aspects of clinical decision-making. Specific topics addressed include reducing medical errors, reevaluating evidence-based medicine, deconstructing several widely cited medical aphorisms, identifying sources of cognitive errors, and transforming information into understanding.

The authors devoted the final chapter to the discussion of “What is disease?” and “What is health?” which, quite frankly, adds little value to the book.

Drs. Goldberger and Goldberger discuss what they term the “interstitial curriculum”—what is not explicitly taught but should be. Included in the “interstitial curriculum” is examination of cognitive errors and how we are more apt to make these in the era of “high-throughput” patient care. Another topic included in their “interstitial curriculum” is the paucity of attention paid to addressing uncertainty in all aspects of medicine. These topics are worth the cost of this book, even if it only helps promote awareness of these important ideas and bring the discussion to a larger audience.

The complementary processes of constantly rethinking assumptions, researching information, and reformulating basic mechanisms are fundamental to practicing all types of medicine successfully. Such processes also help to avoid potentially lethal errors and help to rigorously and compassionately advance the inseparable sciences of prevention and healing. The deep and multidimensional challenges are central to the ongoing pursuit of becoming the consummate clinician.”

Analysis

There are times in this book, particularly in the beginning, when the reader feels this text was written for the benefit of the house officer and those practitioners serving on inpatient teaching services. Continued reading, however, finds brilliant advice for clinicians in all practice settings and in all stages of their careers.

The encouragement of all readers to rethink everything we assume to be true and to seek a deeper understanding of what we “know” is priceless.

The quotes included throughout the book were both valuable and enjoyable. The authors included quotes from Plutarch to Hector Barbosa from Pirates of the Caribbean. One quote that is particularly germane to the practice of hospital medicine in this age of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems comes from Sir William Osler:

“Remember…that every patient upon whom you wait will examine you critically and form an estimate of you by the way in which you conduct yourself at the bedside. Skill and nicety in manipulation, in the simple act of feeling the pulse or in the performance of any minor operation, will do more towards establishing confidence in you than a string of diplomas, or the reputation of extensive hospital experience.”

Conversely, the computer-generated graphics added no value and were, in fact, a detractor. Hopefully, the next edition will not feature the sophomorically rendered bridge advising us to “bridge the classroom-to-clinic gap,” the flamingo, or the zigzagging line, among others.

Dr. Lindsey is chief operations officer and strategist of Synergy Surgicalists, and a member of Team Hospitalist.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Second in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

The third installment in the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series, Becoming a Consummate Clinician is written in two parts. Part 1, “Medical Musts and Must-Nots,” is focused on the basics of being a clinician: gathering an appropriate history, performing an effective physical examination, and formulating differential diagnoses. This section in particular is geared toward house officers and attending physicians on teaching teams. While the audience here is primarily clinicians on a teaching service, there is good advice for those in any practice setting about avoiding common mistakes and developing clinical sagacity.

In this first section, we are given advisement on treatment of and with medications. Regardless of a clinician’s level of experience, it is worth reading this text to review and internalize these authors’ advice regarding medication pitfalls. Simply putting this advice into one’s daily practice of medicine will take any practitioner a long way toward becoming a “consummate clinician.”

Part 2, “Medical Masteries,” logically builds upon material presented in Part 1. The final section of the book addresses aspects of critical analysis of medical data and encourages engagement of critical thinking skills in all aspects of clinical decision-making. Specific topics addressed include reducing medical errors, reevaluating evidence-based medicine, deconstructing several widely cited medical aphorisms, identifying sources of cognitive errors, and transforming information into understanding.

The authors devoted the final chapter to the discussion of “What is disease?” and “What is health?” which, quite frankly, adds little value to the book.

Drs. Goldberger and Goldberger discuss what they term the “interstitial curriculum”—what is not explicitly taught but should be. Included in the “interstitial curriculum” is examination of cognitive errors and how we are more apt to make these in the era of “high-throughput” patient care. Another topic included in their “interstitial curriculum” is the paucity of attention paid to addressing uncertainty in all aspects of medicine. These topics are worth the cost of this book, even if it only helps promote awareness of these important ideas and bring the discussion to a larger audience.

The complementary processes of constantly rethinking assumptions, researching information, and reformulating basic mechanisms are fundamental to practicing all types of medicine successfully. Such processes also help to avoid potentially lethal errors and help to rigorously and compassionately advance the inseparable sciences of prevention and healing. The deep and multidimensional challenges are central to the ongoing pursuit of becoming the consummate clinician.”

Analysis

There are times in this book, particularly in the beginning, when the reader feels this text was written for the benefit of the house officer and those practitioners serving on inpatient teaching services. Continued reading, however, finds brilliant advice for clinicians in all practice settings and in all stages of their careers.

The encouragement of all readers to rethink everything we assume to be true and to seek a deeper understanding of what we “know” is priceless.

The quotes included throughout the book were both valuable and enjoyable. The authors included quotes from Plutarch to Hector Barbosa from Pirates of the Caribbean. One quote that is particularly germane to the practice of hospital medicine in this age of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems comes from Sir William Osler:

“Remember…that every patient upon whom you wait will examine you critically and form an estimate of you by the way in which you conduct yourself at the bedside. Skill and nicety in manipulation, in the simple act of feeling the pulse or in the performance of any minor operation, will do more towards establishing confidence in you than a string of diplomas, or the reputation of extensive hospital experience.”

Conversely, the computer-generated graphics added no value and were, in fact, a detractor. Hopefully, the next edition will not feature the sophomorically rendered bridge advising us to “bridge the classroom-to-clinic gap,” the flamingo, or the zigzagging line, among others.

Dr. Lindsey is chief operations officer and strategist of Synergy Surgicalists, and a member of Team Hospitalist.

When Should You Decolonize Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Hospitalized Patients?

Case

A 45-year-old previously healthy female was admitted to the ICU with sepsis caused by community-acquired pneumonia. Per hospital policy, all patients admitted to the ICU are screened for MRSA colonization. If the nasal screen is positive, contact isolation is initiated and the hospital’s MRSA decolonization protocol is implemented. Her nasal screen was positive for MRSA.

Overview

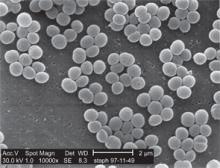

MRSA infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and death occurs in almost 5% of patients who develop a MRSA infection. In 2005, invasive MRSA was responsible for approximately 278,000 hospitalizations and 19,000 deaths. MRSA is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and is the most common pathogen in surgical site infections (SSIs) and ventilator-associated pneumonias. The cost of treating MRSA infections is substantial; in 2003, $14.5 billion was spent on MRSA-related hospitalizations.

It is well known that MRSA colonization is a risk factor for the subsequent development of a MRSA infection. This risk persists over time, and approximately 25% of individuals who are colonized with MRSA for more than one year will develop a late-onset MRSA infection.1 It is estimated that between 0.8% and 6% of people in the U.S. are asymptomatically colonized with MRSA.

One infection control strategy for reducing the transmission of MRSA among hospitalized patients involves screening for the presence of this organism and then placing colonized and/or infected patients in isolation; however, there is considerable controversy about which patients should be screened.

An additional element of many infection control strategies involves MRSA decolonization, but there is uncertainty about which patients benefit from it and significant variability in its reported success rates.2 Additionally, several studies have indicated that MRSA decolonization is only temporary and that patients become recolonized over time.

Treatment

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of MRSA carriers will develop an infection while they are hospitalized. Furthermore, even after they have been discharged from the hospital, their risk for developing a MRSA infection persists.

Most patients who develop a MRSA infection have been colonized prior to infection, and these patients usually develop an infection caused by the same strain as the colonization. In view of this fact, a primary goal of decolonization is reducing the likelihood of “auto-infection.” Another goal of decolonization is reducing the transmission of MRSA to other patients.

In order to determine whether MRSA colonization is present, patients undergo screening, and specimens are collected from the nares using nasal swabs. Specimens from extranasal sites, such as the groin, are sometimes also obtained for screening. These screening tests are usually done with either cultures or polymerase chain reaction testing.

There is significant variability in the details of screening and decolonization protocols among different healthcare facilities. Typically, the screening test costs more than the agents used for decolonization. Partly for this reason, some facilities forego screening altogether, instead treating all patients with a decolonization regimen; however, there is concern that administering decolonizing medications to all patients would lead to the unnecessary treatment of large numbers of patients. Such widespread use of the decolonizing agents might promote the development of resistance to these medications.

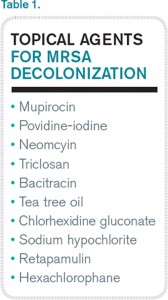

Medications. Decolonization typically involves the use of a topical antibiotic, most commonly mupirocin, which is applied to the nares. This may be used in conjunction with an oral antimicrobial agent. While the nares are the anatomical locations most commonly colonized by MRSA, extranasal colonization occurs in 50% of those who are nasally colonized.

Of the topical medications available for decolonization, mupirocin has the highest efficacy, with eradication of MRSA and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) colonization ranging from 81% to 93%. To increase the likelihood of successful decolonization, an antiseptic agent, such as chlorhexidine gluconate, may also be applied to the skin. Chlorhexidine gluconate is also commonly used to prevent other HAIs.

Neomycin is sometimes used for decolonization, but its efficacy for this purpose is questionable. There are also concerns about resistance, but it may be an option in cases of documented mupirocin resistance. Preparations that contain tea tree oil appear to be more effective for decolonization of skin sites than for nasal decolonization. Table 1 lists the topical antibiotics and antiseptics that may be utilized for decolonization, while Table 2 lists the oral medications that can be used for this purpose. Table 3 lists investigational agents being evaluated for their ability to decolonize patients.

It has been suggested that the patients who might derive the most benefit from decolonization are those at increased risk for developing a MRSA infection during a specific time interval. This would include patients who are admitted to the ICU for an acute illness and cardiothoracic surgery patients. A benefit from decolonization has also been observed in hemodialysis patients, who have an incidence of invasive MRSA infections 100 times greater than the general population. Otherwise, there are no data to support the routine use of decolonization in nonsurgical patients.

It is not uncommon for hospitals to screen patients admitted to the ICU for MRSA nasal colonization; in fact, screening is mandatory in nine states. If the nasal screen is positive, contact precautions are instituted. The decision about whether or not to initiate a decolonization protocol varies among different ICUs, but most do not carry out universal decolonization.

Some studies show decolonization is beneficial for ICU patients. These studies include a large cluster-randomized trial called REDUCE MRSA,3 which took place in 43 hospitals and involved 74,256 patients in 74 ICUs. The study showed that universal (i.e., without screening) decolonization using mupirocin and chlorhexidine was effective in reducing rates of MRSA clinical isolates, as well as bloodstream infection from any pathogen. Other studies have demonstrated benefits from the decolonization of ICU patients.4,5

Surgical Site Infections. Meanwhile, SSIs are often associated with increased mortality rates and substantial healthcare costs, including increased hospital lengths of stay and readmission rates. Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen most commonly isolated from SSIs. In surgical patients, colonization with MRSA is associated with an elevated rate of MRSA SSIs. The goal of decolonization in surgical patients is not to permanently eliminate MRSA but to prevent SSIs by suppressing the presence of this organism for a relatively brief duration.

There is evidence that decolonization reduces SSIs for cardiothoracic surgeries.6 For these patients, it is cost effective to screen for nasal carriage of MRSA and then treat carriers with a combination of pre-operative mupirocin and chlorhexidine. It may be reasonable to delay cardiothoracic surgery in colonized patients who will require implantation of prosthetic material until they complete MRSA decolonization.

In addition to reducing the risk of auto-infection, another goal of decolonization is limiting the possibility of transmission of MRSA from a colonized patient to a susceptible individual; however, there are only limited data available that measure the efficacy of decolonization for preventing transmission.

Concerns about the potential hazards of decolonization therapy have impacted its widespread implementation. The biggest concern is that patients may develop resistance to the antimicrobial agents used for decolonization, particularly if they are used at increased frequency. Mupirocin resistance monitoring is valuable, but, unfortunately, the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to mupirocin is not routinely evaluated, so the prevalence of mupirocin resistance in local strains is often unknown. Another concern about decolonization is the cost of screening and decolonizing patients.

Back to the Case

The patient in this case required admission to an ICU and, based on the results of the REDUCE MRSA clinical trial, she would likely benefit from undergoing decolonization to reduce her risk of both MRSA-positive clinical cultures and bloodstream infections caused by any pathogen.

Bottom Line

Decolonization is beneficial for patients at increased risk of developing a MRSA infection during a specific period, such as patients admitted to the ICU and those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.

Dr. Clarke is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital and a faculty member in the Emory University Department of Medicine, both in Atlanta.

References

- Dow G, Field D, Mancuso M, Allard J. Decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during routine hospital care: Efficacy and long-term follow-up. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010;21(1):38-44.

- Simor AE. Staphylococcal decolonisation: An effective strategy for prevention of infection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):952-962.

- Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2255-2265.

- Fraser T, Fatica C, Scarpelli M, et al. Decrease in Staphylococcus aureus colonization and hospital-acquired infection in a medical intensive care unit after institution of an active surveillance and decolonization program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(8):779-783.

- Robotham J, Graves N, Cookson B, et al. Screening, isolation, and decolonisation strategies in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units: Cost effectiveness evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343:d5694.

- Schweizer M, Perencevich E, McDanel J, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention of decolonization and prophylaxis to decrease Gram positive surgical site infections after cardiac or orthopedic surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2743.

Case

A 45-year-old previously healthy female was admitted to the ICU with sepsis caused by community-acquired pneumonia. Per hospital policy, all patients admitted to the ICU are screened for MRSA colonization. If the nasal screen is positive, contact isolation is initiated and the hospital’s MRSA decolonization protocol is implemented. Her nasal screen was positive for MRSA.

Overview

MRSA infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and death occurs in almost 5% of patients who develop a MRSA infection. In 2005, invasive MRSA was responsible for approximately 278,000 hospitalizations and 19,000 deaths. MRSA is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and is the most common pathogen in surgical site infections (SSIs) and ventilator-associated pneumonias. The cost of treating MRSA infections is substantial; in 2003, $14.5 billion was spent on MRSA-related hospitalizations.

It is well known that MRSA colonization is a risk factor for the subsequent development of a MRSA infection. This risk persists over time, and approximately 25% of individuals who are colonized with MRSA for more than one year will develop a late-onset MRSA infection.1 It is estimated that between 0.8% and 6% of people in the U.S. are asymptomatically colonized with MRSA.

One infection control strategy for reducing the transmission of MRSA among hospitalized patients involves screening for the presence of this organism and then placing colonized and/or infected patients in isolation; however, there is considerable controversy about which patients should be screened.

An additional element of many infection control strategies involves MRSA decolonization, but there is uncertainty about which patients benefit from it and significant variability in its reported success rates.2 Additionally, several studies have indicated that MRSA decolonization is only temporary and that patients become recolonized over time.

Treatment

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of MRSA carriers will develop an infection while they are hospitalized. Furthermore, even after they have been discharged from the hospital, their risk for developing a MRSA infection persists.

Most patients who develop a MRSA infection have been colonized prior to infection, and these patients usually develop an infection caused by the same strain as the colonization. In view of this fact, a primary goal of decolonization is reducing the likelihood of “auto-infection.” Another goal of decolonization is reducing the transmission of MRSA to other patients.

In order to determine whether MRSA colonization is present, patients undergo screening, and specimens are collected from the nares using nasal swabs. Specimens from extranasal sites, such as the groin, are sometimes also obtained for screening. These screening tests are usually done with either cultures or polymerase chain reaction testing.

There is significant variability in the details of screening and decolonization protocols among different healthcare facilities. Typically, the screening test costs more than the agents used for decolonization. Partly for this reason, some facilities forego screening altogether, instead treating all patients with a decolonization regimen; however, there is concern that administering decolonizing medications to all patients would lead to the unnecessary treatment of large numbers of patients. Such widespread use of the decolonizing agents might promote the development of resistance to these medications.

Medications. Decolonization typically involves the use of a topical antibiotic, most commonly mupirocin, which is applied to the nares. This may be used in conjunction with an oral antimicrobial agent. While the nares are the anatomical locations most commonly colonized by MRSA, extranasal colonization occurs in 50% of those who are nasally colonized.

Of the topical medications available for decolonization, mupirocin has the highest efficacy, with eradication of MRSA and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) colonization ranging from 81% to 93%. To increase the likelihood of successful decolonization, an antiseptic agent, such as chlorhexidine gluconate, may also be applied to the skin. Chlorhexidine gluconate is also commonly used to prevent other HAIs.

Neomycin is sometimes used for decolonization, but its efficacy for this purpose is questionable. There are also concerns about resistance, but it may be an option in cases of documented mupirocin resistance. Preparations that contain tea tree oil appear to be more effective for decolonization of skin sites than for nasal decolonization. Table 1 lists the topical antibiotics and antiseptics that may be utilized for decolonization, while Table 2 lists the oral medications that can be used for this purpose. Table 3 lists investigational agents being evaluated for their ability to decolonize patients.

It has been suggested that the patients who might derive the most benefit from decolonization are those at increased risk for developing a MRSA infection during a specific time interval. This would include patients who are admitted to the ICU for an acute illness and cardiothoracic surgery patients. A benefit from decolonization has also been observed in hemodialysis patients, who have an incidence of invasive MRSA infections 100 times greater than the general population. Otherwise, there are no data to support the routine use of decolonization in nonsurgical patients.

It is not uncommon for hospitals to screen patients admitted to the ICU for MRSA nasal colonization; in fact, screening is mandatory in nine states. If the nasal screen is positive, contact precautions are instituted. The decision about whether or not to initiate a decolonization protocol varies among different ICUs, but most do not carry out universal decolonization.

Some studies show decolonization is beneficial for ICU patients. These studies include a large cluster-randomized trial called REDUCE MRSA,3 which took place in 43 hospitals and involved 74,256 patients in 74 ICUs. The study showed that universal (i.e., without screening) decolonization using mupirocin and chlorhexidine was effective in reducing rates of MRSA clinical isolates, as well as bloodstream infection from any pathogen. Other studies have demonstrated benefits from the decolonization of ICU patients.4,5

Surgical Site Infections. Meanwhile, SSIs are often associated with increased mortality rates and substantial healthcare costs, including increased hospital lengths of stay and readmission rates. Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen most commonly isolated from SSIs. In surgical patients, colonization with MRSA is associated with an elevated rate of MRSA SSIs. The goal of decolonization in surgical patients is not to permanently eliminate MRSA but to prevent SSIs by suppressing the presence of this organism for a relatively brief duration.

There is evidence that decolonization reduces SSIs for cardiothoracic surgeries.6 For these patients, it is cost effective to screen for nasal carriage of MRSA and then treat carriers with a combination of pre-operative mupirocin and chlorhexidine. It may be reasonable to delay cardiothoracic surgery in colonized patients who will require implantation of prosthetic material until they complete MRSA decolonization.

In addition to reducing the risk of auto-infection, another goal of decolonization is limiting the possibility of transmission of MRSA from a colonized patient to a susceptible individual; however, there are only limited data available that measure the efficacy of decolonization for preventing transmission.

Concerns about the potential hazards of decolonization therapy have impacted its widespread implementation. The biggest concern is that patients may develop resistance to the antimicrobial agents used for decolonization, particularly if they are used at increased frequency. Mupirocin resistance monitoring is valuable, but, unfortunately, the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to mupirocin is not routinely evaluated, so the prevalence of mupirocin resistance in local strains is often unknown. Another concern about decolonization is the cost of screening and decolonizing patients.

Back to the Case

The patient in this case required admission to an ICU and, based on the results of the REDUCE MRSA clinical trial, she would likely benefit from undergoing decolonization to reduce her risk of both MRSA-positive clinical cultures and bloodstream infections caused by any pathogen.

Bottom Line

Decolonization is beneficial for patients at increased risk of developing a MRSA infection during a specific period, such as patients admitted to the ICU and those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.

Dr. Clarke is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital and a faculty member in the Emory University Department of Medicine, both in Atlanta.

References

- Dow G, Field D, Mancuso M, Allard J. Decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during routine hospital care: Efficacy and long-term follow-up. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010;21(1):38-44.

- Simor AE. Staphylococcal decolonisation: An effective strategy for prevention of infection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):952-962.

- Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2255-2265.

- Fraser T, Fatica C, Scarpelli M, et al. Decrease in Staphylococcus aureus colonization and hospital-acquired infection in a medical intensive care unit after institution of an active surveillance and decolonization program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(8):779-783.

- Robotham J, Graves N, Cookson B, et al. Screening, isolation, and decolonisation strategies in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units: Cost effectiveness evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343:d5694.

- Schweizer M, Perencevich E, McDanel J, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention of decolonization and prophylaxis to decrease Gram positive surgical site infections after cardiac or orthopedic surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2743.

Case

A 45-year-old previously healthy female was admitted to the ICU with sepsis caused by community-acquired pneumonia. Per hospital policy, all patients admitted to the ICU are screened for MRSA colonization. If the nasal screen is positive, contact isolation is initiated and the hospital’s MRSA decolonization protocol is implemented. Her nasal screen was positive for MRSA.

Overview

MRSA infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and death occurs in almost 5% of patients who develop a MRSA infection. In 2005, invasive MRSA was responsible for approximately 278,000 hospitalizations and 19,000 deaths. MRSA is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and is the most common pathogen in surgical site infections (SSIs) and ventilator-associated pneumonias. The cost of treating MRSA infections is substantial; in 2003, $14.5 billion was spent on MRSA-related hospitalizations.

It is well known that MRSA colonization is a risk factor for the subsequent development of a MRSA infection. This risk persists over time, and approximately 25% of individuals who are colonized with MRSA for more than one year will develop a late-onset MRSA infection.1 It is estimated that between 0.8% and 6% of people in the U.S. are asymptomatically colonized with MRSA.

One infection control strategy for reducing the transmission of MRSA among hospitalized patients involves screening for the presence of this organism and then placing colonized and/or infected patients in isolation; however, there is considerable controversy about which patients should be screened.

An additional element of many infection control strategies involves MRSA decolonization, but there is uncertainty about which patients benefit from it and significant variability in its reported success rates.2 Additionally, several studies have indicated that MRSA decolonization is only temporary and that patients become recolonized over time.

Treatment

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of MRSA carriers will develop an infection while they are hospitalized. Furthermore, even after they have been discharged from the hospital, their risk for developing a MRSA infection persists.

Most patients who develop a MRSA infection have been colonized prior to infection, and these patients usually develop an infection caused by the same strain as the colonization. In view of this fact, a primary goal of decolonization is reducing the likelihood of “auto-infection.” Another goal of decolonization is reducing the transmission of MRSA to other patients.

In order to determine whether MRSA colonization is present, patients undergo screening, and specimens are collected from the nares using nasal swabs. Specimens from extranasal sites, such as the groin, are sometimes also obtained for screening. These screening tests are usually done with either cultures or polymerase chain reaction testing.

There is significant variability in the details of screening and decolonization protocols among different healthcare facilities. Typically, the screening test costs more than the agents used for decolonization. Partly for this reason, some facilities forego screening altogether, instead treating all patients with a decolonization regimen; however, there is concern that administering decolonizing medications to all patients would lead to the unnecessary treatment of large numbers of patients. Such widespread use of the decolonizing agents might promote the development of resistance to these medications.

Medications. Decolonization typically involves the use of a topical antibiotic, most commonly mupirocin, which is applied to the nares. This may be used in conjunction with an oral antimicrobial agent. While the nares are the anatomical locations most commonly colonized by MRSA, extranasal colonization occurs in 50% of those who are nasally colonized.

Of the topical medications available for decolonization, mupirocin has the highest efficacy, with eradication of MRSA and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) colonization ranging from 81% to 93%. To increase the likelihood of successful decolonization, an antiseptic agent, such as chlorhexidine gluconate, may also be applied to the skin. Chlorhexidine gluconate is also commonly used to prevent other HAIs.

Neomycin is sometimes used for decolonization, but its efficacy for this purpose is questionable. There are also concerns about resistance, but it may be an option in cases of documented mupirocin resistance. Preparations that contain tea tree oil appear to be more effective for decolonization of skin sites than for nasal decolonization. Table 1 lists the topical antibiotics and antiseptics that may be utilized for decolonization, while Table 2 lists the oral medications that can be used for this purpose. Table 3 lists investigational agents being evaluated for their ability to decolonize patients.

It has been suggested that the patients who might derive the most benefit from decolonization are those at increased risk for developing a MRSA infection during a specific time interval. This would include patients who are admitted to the ICU for an acute illness and cardiothoracic surgery patients. A benefit from decolonization has also been observed in hemodialysis patients, who have an incidence of invasive MRSA infections 100 times greater than the general population. Otherwise, there are no data to support the routine use of decolonization in nonsurgical patients.

It is not uncommon for hospitals to screen patients admitted to the ICU for MRSA nasal colonization; in fact, screening is mandatory in nine states. If the nasal screen is positive, contact precautions are instituted. The decision about whether or not to initiate a decolonization protocol varies among different ICUs, but most do not carry out universal decolonization.

Some studies show decolonization is beneficial for ICU patients. These studies include a large cluster-randomized trial called REDUCE MRSA,3 which took place in 43 hospitals and involved 74,256 patients in 74 ICUs. The study showed that universal (i.e., without screening) decolonization using mupirocin and chlorhexidine was effective in reducing rates of MRSA clinical isolates, as well as bloodstream infection from any pathogen. Other studies have demonstrated benefits from the decolonization of ICU patients.4,5

Surgical Site Infections. Meanwhile, SSIs are often associated with increased mortality rates and substantial healthcare costs, including increased hospital lengths of stay and readmission rates. Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen most commonly isolated from SSIs. In surgical patients, colonization with MRSA is associated with an elevated rate of MRSA SSIs. The goal of decolonization in surgical patients is not to permanently eliminate MRSA but to prevent SSIs by suppressing the presence of this organism for a relatively brief duration.

There is evidence that decolonization reduces SSIs for cardiothoracic surgeries.6 For these patients, it is cost effective to screen for nasal carriage of MRSA and then treat carriers with a combination of pre-operative mupirocin and chlorhexidine. It may be reasonable to delay cardiothoracic surgery in colonized patients who will require implantation of prosthetic material until they complete MRSA decolonization.

In addition to reducing the risk of auto-infection, another goal of decolonization is limiting the possibility of transmission of MRSA from a colonized patient to a susceptible individual; however, there are only limited data available that measure the efficacy of decolonization for preventing transmission.

Concerns about the potential hazards of decolonization therapy have impacted its widespread implementation. The biggest concern is that patients may develop resistance to the antimicrobial agents used for decolonization, particularly if they are used at increased frequency. Mupirocin resistance monitoring is valuable, but, unfortunately, the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to mupirocin is not routinely evaluated, so the prevalence of mupirocin resistance in local strains is often unknown. Another concern about decolonization is the cost of screening and decolonizing patients.

Back to the Case

The patient in this case required admission to an ICU and, based on the results of the REDUCE MRSA clinical trial, she would likely benefit from undergoing decolonization to reduce her risk of both MRSA-positive clinical cultures and bloodstream infections caused by any pathogen.

Bottom Line

Decolonization is beneficial for patients at increased risk of developing a MRSA infection during a specific period, such as patients admitted to the ICU and those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.

Dr. Clarke is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University Hospital and a faculty member in the Emory University Department of Medicine, both in Atlanta.

References

- Dow G, Field D, Mancuso M, Allard J. Decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during routine hospital care: Efficacy and long-term follow-up. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010;21(1):38-44.

- Simor AE. Staphylococcal decolonisation: An effective strategy for prevention of infection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(12):952-962.

- Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(24):2255-2265.

- Fraser T, Fatica C, Scarpelli M, et al. Decrease in Staphylococcus aureus colonization and hospital-acquired infection in a medical intensive care unit after institution of an active surveillance and decolonization program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(8):779-783.

- Robotham J, Graves N, Cookson B, et al. Screening, isolation, and decolonisation strategies in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care units: Cost effectiveness evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343:d5694.

- Schweizer M, Perencevich E, McDanel J, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention of decolonization and prophylaxis to decrease Gram positive surgical site infections after cardiac or orthopedic surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2743.