User login

Triple therapy in question

Clinical question: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor safer than, and as efficacious as, triple therapy with warfarin?

Background: Recent studies have shown that patients on long-term anticoagulation who undergo PCI can be managed on oral anticoagulants and P2Y12 inhibitors with lower bleeding rates than do those who receive triple therapy.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 414 sites in 41 countries.

Synopsis: In 2,725 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, low-dose (110 mg, twice daily) and high-dose (150 mg, twice daily) dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor lowered absolute bleeding risk by 11.5% and 5.5%, respectively, compared with triple therapy. Rates of thrombosis, death, and unexpected revascularization as a composite endpoint were noninferior to triple therapy for both dabigatran doses studied. In patients on dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, it is reasonable to continue dabigatran and add a single P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) but not aspirin after PCI. In patients at high risk for bleeding complications, it may be reasonable to dose reduce the dabigatran from 150 mg twice daily to 110 mg twice daily before starting antiplatelet therapy, although the study was underpowered to examine this.

Bottom line: In patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, dabigatran plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor had lower bleeding rates and was noninferior with respect to the risk of thromboembolic events when compared with triple therapy with warfarin.

Citation: Cannon CP et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor safer than, and as efficacious as, triple therapy with warfarin?

Background: Recent studies have shown that patients on long-term anticoagulation who undergo PCI can be managed on oral anticoagulants and P2Y12 inhibitors with lower bleeding rates than do those who receive triple therapy.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 414 sites in 41 countries.

Synopsis: In 2,725 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, low-dose (110 mg, twice daily) and high-dose (150 mg, twice daily) dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor lowered absolute bleeding risk by 11.5% and 5.5%, respectively, compared with triple therapy. Rates of thrombosis, death, and unexpected revascularization as a composite endpoint were noninferior to triple therapy for both dabigatran doses studied. In patients on dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, it is reasonable to continue dabigatran and add a single P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) but not aspirin after PCI. In patients at high risk for bleeding complications, it may be reasonable to dose reduce the dabigatran from 150 mg twice daily to 110 mg twice daily before starting antiplatelet therapy, although the study was underpowered to examine this.

Bottom line: In patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, dabigatran plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor had lower bleeding rates and was noninferior with respect to the risk of thromboembolic events when compared with triple therapy with warfarin.

Citation: Cannon CP et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor safer than, and as efficacious as, triple therapy with warfarin?

Background: Recent studies have shown that patients on long-term anticoagulation who undergo PCI can be managed on oral anticoagulants and P2Y12 inhibitors with lower bleeding rates than do those who receive triple therapy.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 414 sites in 41 countries.

Synopsis: In 2,725 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, low-dose (110 mg, twice daily) and high-dose (150 mg, twice daily) dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor lowered absolute bleeding risk by 11.5% and 5.5%, respectively, compared with triple therapy. Rates of thrombosis, death, and unexpected revascularization as a composite endpoint were noninferior to triple therapy for both dabigatran doses studied. In patients on dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, it is reasonable to continue dabigatran and add a single P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) but not aspirin after PCI. In patients at high risk for bleeding complications, it may be reasonable to dose reduce the dabigatran from 150 mg twice daily to 110 mg twice daily before starting antiplatelet therapy, although the study was underpowered to examine this.

Bottom line: In patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, dabigatran plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor had lower bleeding rates and was noninferior with respect to the risk of thromboembolic events when compared with triple therapy with warfarin.

Citation: Cannon CP et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Rivaroxaban lowers cardiovascular risk but increases bleeding risk

Clinical question: Is rivaroxaban alone or in combination with aspirin more effective than is aspirin alone in preventing cardiovascular events in patients with stable atherosclerotic disease?

Background: Previous studies have shown that, among patients with stable atherosclerosis, anticoagulation with a vitamin-K antagonist (VKA) plus aspirin is superior to aspirin alone for secondary prevention but has increased rates of major bleeding.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: 602 sites in 33 countries.

Synopsis: In 27,395 patients with stable atherosclerotic disease, the addition of 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily to aspirin therapy reduced the rates of cardiovascular death, stroke, or nonfatal MI, at the cost of increased major bleeding rates. The authors found a 1.3% absolute risk reduction in recurrent cardiovascular events, but a 1.2% absolute increase in major bleeding rates, although intracranial and fatal bleeding rates were similar between the two groups. The trial was stopped early for efficacy, which may overestimate the treatment effect. In addition, much of the benefit in the rivaroxaban-plus-aspirin group was driven by lower rates of ischemic stroke. Rates of myocardial infarction were not significantly different between the groups. The addition of rivaroxaban to aspirin for secondary prevention should be individualized and considered in patients at high risk for ischemic stroke with low bleeding risk.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban plus aspirin lowers ischemic event rates in stable atherosclerosis compared to aspirin but increases major bleeding rates. Cost efficacy is uncertain.

Citation: Eikelboom JW et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709118.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Is rivaroxaban alone or in combination with aspirin more effective than is aspirin alone in preventing cardiovascular events in patients with stable atherosclerotic disease?

Background: Previous studies have shown that, among patients with stable atherosclerosis, anticoagulation with a vitamin-K antagonist (VKA) plus aspirin is superior to aspirin alone for secondary prevention but has increased rates of major bleeding.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: 602 sites in 33 countries.

Synopsis: In 27,395 patients with stable atherosclerotic disease, the addition of 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily to aspirin therapy reduced the rates of cardiovascular death, stroke, or nonfatal MI, at the cost of increased major bleeding rates. The authors found a 1.3% absolute risk reduction in recurrent cardiovascular events, but a 1.2% absolute increase in major bleeding rates, although intracranial and fatal bleeding rates were similar between the two groups. The trial was stopped early for efficacy, which may overestimate the treatment effect. In addition, much of the benefit in the rivaroxaban-plus-aspirin group was driven by lower rates of ischemic stroke. Rates of myocardial infarction were not significantly different between the groups. The addition of rivaroxaban to aspirin for secondary prevention should be individualized and considered in patients at high risk for ischemic stroke with low bleeding risk.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban plus aspirin lowers ischemic event rates in stable atherosclerosis compared to aspirin but increases major bleeding rates. Cost efficacy is uncertain.

Citation: Eikelboom JW et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709118.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Is rivaroxaban alone or in combination with aspirin more effective than is aspirin alone in preventing cardiovascular events in patients with stable atherosclerotic disease?

Background: Previous studies have shown that, among patients with stable atherosclerosis, anticoagulation with a vitamin-K antagonist (VKA) plus aspirin is superior to aspirin alone for secondary prevention but has increased rates of major bleeding.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: 602 sites in 33 countries.

Synopsis: In 27,395 patients with stable atherosclerotic disease, the addition of 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily to aspirin therapy reduced the rates of cardiovascular death, stroke, or nonfatal MI, at the cost of increased major bleeding rates. The authors found a 1.3% absolute risk reduction in recurrent cardiovascular events, but a 1.2% absolute increase in major bleeding rates, although intracranial and fatal bleeding rates were similar between the two groups. The trial was stopped early for efficacy, which may overestimate the treatment effect. In addition, much of the benefit in the rivaroxaban-plus-aspirin group was driven by lower rates of ischemic stroke. Rates of myocardial infarction were not significantly different between the groups. The addition of rivaroxaban to aspirin for secondary prevention should be individualized and considered in patients at high risk for ischemic stroke with low bleeding risk.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban plus aspirin lowers ischemic event rates in stable atherosclerosis compared to aspirin but increases major bleeding rates. Cost efficacy is uncertain.

Citation: Eikelboom JW et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709118.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

FVC deterioration signals increasing risk in rib fracture patients

ORLANDO – according to a study presented at the annual scientific assembly Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Daily, easily conducted, bedside FVC monitoring can help identify the first signs of a worsening condition and lead to earlier intervention, according to presenter Rachel Warner, DO, a surgical resident at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

“Unplanned upgrades to the ICU have been associated with prolonged hospital stay, mechanical ventilation, and even higher risk of mortality when compared to planned upgrades,” Dr. Warner explained. “We aim to decrease these events by creating a system where early decline can be recognized by any member of the health care team.”

In a retrospective study, investigators analyzed 1,106 rib fracture patients enrolled in a rib fracture care pathway at a Level I trauma center during 2009-2014, all of whom were admitted with an FVC greater than 1 L. Patients’ FVCs were assessed with spirometry in the ED, and the results were then used to determine their care placement. Then FVC was continually monitored throughout each patient’s stay at the hospital. The investigators hypothesized that those patients whose FVC level deteriorated to lower than 1 L were at higher risk for complications.

Two groups of patients were analyzed: Group A was composed of patients whose initial FVC scores were greater than or equal to 1 but deteriorated over time to below 1, while Group B was composed of patients whose scores remained above 1. Group A patients were an average age 58 years and were majority male (61%); their had FVC scores initially averaged 1.3 but dropped to a low of 0.7. Patients in group B were on average younger, at 48 years, but also majority male (79%); they had a slightly higher initial average FVC of 1.6, with a low of 1.4.

Rate of complications among patients whose FVC scores dropped below 1 was 15%, compared with 3.2% in the other group (P less than .001).

Group A patients were significantly more likely than were Group B patients to develop pneumonia (9% vs. 4%, respectively), be upgraded to the intensive care unit (3.7% vs. 0.2%), require intubation (1.6% vs. 0.1%), or be readmitted (4% vs. 1%).

Average length of stay for patients whose FVC score dropped below 1 was 10 days, compared with 4 days among the patients who maintained a higher FVC. Mortality rates were also significantly higher at 3%, compared with 0.2%. Dr. Warner said that FVC levels can be the first indication of worsening clinical status and should be treated as an early warning sign for which patients may need to be preemptively moved to a higher level of care.

Dr. Warner and her colleagues were limited by the retrospective nature of their analysis, as well as not including other injuries into their analysis.

In a discussion of the study, Bryce R.H. Robinson, MD, FACS, of Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Wash., supported using data such as FVC to help identify at-risk patients early. “I am encouraged to see others utilize easily obtainable, objective measures for those at risk for pulmonary decompensation with rib fractures,” said Dr. Robinson.

While keeping the cutoff at 1 L for FVC testing regardless of other factors, like sex or weight, would make it easy to train all members of the medical team, this may be oversimplifying FVC measurements, cautioned Dr. Robinson.

“While it is a little bit less specific to the patient, broad adaptation across the health care team is much more feasible with standard values,” responded Dr. Warner. “Given this, we do intentionally accept a level of overtriaged patients. We have found these patients generally make up the geriatric population and have confounding factors that would otherwise make them high risk for complications.”

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Warner R et al. EAST Scientific Assembly 2018 abstract #9

ORLANDO – according to a study presented at the annual scientific assembly Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Daily, easily conducted, bedside FVC monitoring can help identify the first signs of a worsening condition and lead to earlier intervention, according to presenter Rachel Warner, DO, a surgical resident at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

“Unplanned upgrades to the ICU have been associated with prolonged hospital stay, mechanical ventilation, and even higher risk of mortality when compared to planned upgrades,” Dr. Warner explained. “We aim to decrease these events by creating a system where early decline can be recognized by any member of the health care team.”

In a retrospective study, investigators analyzed 1,106 rib fracture patients enrolled in a rib fracture care pathway at a Level I trauma center during 2009-2014, all of whom were admitted with an FVC greater than 1 L. Patients’ FVCs were assessed with spirometry in the ED, and the results were then used to determine their care placement. Then FVC was continually monitored throughout each patient’s stay at the hospital. The investigators hypothesized that those patients whose FVC level deteriorated to lower than 1 L were at higher risk for complications.

Two groups of patients were analyzed: Group A was composed of patients whose initial FVC scores were greater than or equal to 1 but deteriorated over time to below 1, while Group B was composed of patients whose scores remained above 1. Group A patients were an average age 58 years and were majority male (61%); their had FVC scores initially averaged 1.3 but dropped to a low of 0.7. Patients in group B were on average younger, at 48 years, but also majority male (79%); they had a slightly higher initial average FVC of 1.6, with a low of 1.4.

Rate of complications among patients whose FVC scores dropped below 1 was 15%, compared with 3.2% in the other group (P less than .001).

Group A patients were significantly more likely than were Group B patients to develop pneumonia (9% vs. 4%, respectively), be upgraded to the intensive care unit (3.7% vs. 0.2%), require intubation (1.6% vs. 0.1%), or be readmitted (4% vs. 1%).

Average length of stay for patients whose FVC score dropped below 1 was 10 days, compared with 4 days among the patients who maintained a higher FVC. Mortality rates were also significantly higher at 3%, compared with 0.2%. Dr. Warner said that FVC levels can be the first indication of worsening clinical status and should be treated as an early warning sign for which patients may need to be preemptively moved to a higher level of care.

Dr. Warner and her colleagues were limited by the retrospective nature of their analysis, as well as not including other injuries into their analysis.

In a discussion of the study, Bryce R.H. Robinson, MD, FACS, of Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Wash., supported using data such as FVC to help identify at-risk patients early. “I am encouraged to see others utilize easily obtainable, objective measures for those at risk for pulmonary decompensation with rib fractures,” said Dr. Robinson.

While keeping the cutoff at 1 L for FVC testing regardless of other factors, like sex or weight, would make it easy to train all members of the medical team, this may be oversimplifying FVC measurements, cautioned Dr. Robinson.

“While it is a little bit less specific to the patient, broad adaptation across the health care team is much more feasible with standard values,” responded Dr. Warner. “Given this, we do intentionally accept a level of overtriaged patients. We have found these patients generally make up the geriatric population and have confounding factors that would otherwise make them high risk for complications.”

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Warner R et al. EAST Scientific Assembly 2018 abstract #9

ORLANDO – according to a study presented at the annual scientific assembly Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Daily, easily conducted, bedside FVC monitoring can help identify the first signs of a worsening condition and lead to earlier intervention, according to presenter Rachel Warner, DO, a surgical resident at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

“Unplanned upgrades to the ICU have been associated with prolonged hospital stay, mechanical ventilation, and even higher risk of mortality when compared to planned upgrades,” Dr. Warner explained. “We aim to decrease these events by creating a system where early decline can be recognized by any member of the health care team.”

In a retrospective study, investigators analyzed 1,106 rib fracture patients enrolled in a rib fracture care pathway at a Level I trauma center during 2009-2014, all of whom were admitted with an FVC greater than 1 L. Patients’ FVCs were assessed with spirometry in the ED, and the results were then used to determine their care placement. Then FVC was continually monitored throughout each patient’s stay at the hospital. The investigators hypothesized that those patients whose FVC level deteriorated to lower than 1 L were at higher risk for complications.

Two groups of patients were analyzed: Group A was composed of patients whose initial FVC scores were greater than or equal to 1 but deteriorated over time to below 1, while Group B was composed of patients whose scores remained above 1. Group A patients were an average age 58 years and were majority male (61%); their had FVC scores initially averaged 1.3 but dropped to a low of 0.7. Patients in group B were on average younger, at 48 years, but also majority male (79%); they had a slightly higher initial average FVC of 1.6, with a low of 1.4.

Rate of complications among patients whose FVC scores dropped below 1 was 15%, compared with 3.2% in the other group (P less than .001).

Group A patients were significantly more likely than were Group B patients to develop pneumonia (9% vs. 4%, respectively), be upgraded to the intensive care unit (3.7% vs. 0.2%), require intubation (1.6% vs. 0.1%), or be readmitted (4% vs. 1%).

Average length of stay for patients whose FVC score dropped below 1 was 10 days, compared with 4 days among the patients who maintained a higher FVC. Mortality rates were also significantly higher at 3%, compared with 0.2%. Dr. Warner said that FVC levels can be the first indication of worsening clinical status and should be treated as an early warning sign for which patients may need to be preemptively moved to a higher level of care.

Dr. Warner and her colleagues were limited by the retrospective nature of their analysis, as well as not including other injuries into their analysis.

In a discussion of the study, Bryce R.H. Robinson, MD, FACS, of Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Wash., supported using data such as FVC to help identify at-risk patients early. “I am encouraged to see others utilize easily obtainable, objective measures for those at risk for pulmonary decompensation with rib fractures,” said Dr. Robinson.

While keeping the cutoff at 1 L for FVC testing regardless of other factors, like sex or weight, would make it easy to train all members of the medical team, this may be oversimplifying FVC measurements, cautioned Dr. Robinson.

“While it is a little bit less specific to the patient, broad adaptation across the health care team is much more feasible with standard values,” responded Dr. Warner. “Given this, we do intentionally accept a level of overtriaged patients. We have found these patients generally make up the geriatric population and have confounding factors that would otherwise make them high risk for complications.”

Investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Warner R et al. EAST Scientific Assembly 2018 abstract #9

REPORTING FROM EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: Rib fracture patients with FVC below 1 are at higher risk for pulmonary complications.

Major finding: Rate of pulmonary complications was 15% among patients with FVC under 1, compared to 3% in patients with FVC above 1 (P less than .001).

Study details: Retrospective study of 1,106 patients enrolled at a Level I trauma center from 2009 through 2014.

Disclosures: Presenters reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Warner R et al. EAST Scientific Assembly 2018 abstract #9.

Prescribe antibiotics wisely

Clinical question: What is the incidence of antibiotic-associated adverse drug events (ADEs) among adult inpatients?

Background: Antibiotics are used widely in the inpatient setting, although 20%-30% of inpatient antibiotic prescription are estimated to be unnecessary. Data are lacking on the rates of associated ADEs.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Synopsis: Of the 5,579 patients admitted to four inpatient medicine services between September 2013 and June 2014, 1,488 (27%) received antibiotics for at least 24 hours. Patients were followed through admission and out to 90 days. A total of 324 unique antibiotic-associated ADEs occurred among 298 (20%) patients within 90 days of initial therapy. The overall rate of antibiotic-associated ADEs was 22.9/10,000 person-days. The investigators determined that 287 (19%) of antibiotic regimens were not clinically indicated, and among those, there were 56 (20%) ADEs. The most common 30-day ADEs were gastrointestinal, renal, and hematologic. The highest proportion of ADEs occurred with beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, intravenous vancomycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, perhaps reflecting how commonly these agents are prescribed. Nearly all ADEs were considered clinically significant (97%). There were no deaths attributable to antibiotic-associated ADEs.

Bottom line: Antibiotic associated ADEs occur in about one in five inpatients, and about one in five antibiotic prescriptions may not be clinically indicated.

Citation: Tamma PD et al. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;177(9):1308-15.

Dr. Anderson is an associate program director in the internal medicine residency training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a hospitalist at the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System in Denver.

Clinical question: What is the incidence of antibiotic-associated adverse drug events (ADEs) among adult inpatients?

Background: Antibiotics are used widely in the inpatient setting, although 20%-30% of inpatient antibiotic prescription are estimated to be unnecessary. Data are lacking on the rates of associated ADEs.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Synopsis: Of the 5,579 patients admitted to four inpatient medicine services between September 2013 and June 2014, 1,488 (27%) received antibiotics for at least 24 hours. Patients were followed through admission and out to 90 days. A total of 324 unique antibiotic-associated ADEs occurred among 298 (20%) patients within 90 days of initial therapy. The overall rate of antibiotic-associated ADEs was 22.9/10,000 person-days. The investigators determined that 287 (19%) of antibiotic regimens were not clinically indicated, and among those, there were 56 (20%) ADEs. The most common 30-day ADEs were gastrointestinal, renal, and hematologic. The highest proportion of ADEs occurred with beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, intravenous vancomycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, perhaps reflecting how commonly these agents are prescribed. Nearly all ADEs were considered clinically significant (97%). There were no deaths attributable to antibiotic-associated ADEs.

Bottom line: Antibiotic associated ADEs occur in about one in five inpatients, and about one in five antibiotic prescriptions may not be clinically indicated.

Citation: Tamma PD et al. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;177(9):1308-15.

Dr. Anderson is an associate program director in the internal medicine residency training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a hospitalist at the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System in Denver.

Clinical question: What is the incidence of antibiotic-associated adverse drug events (ADEs) among adult inpatients?

Background: Antibiotics are used widely in the inpatient setting, although 20%-30% of inpatient antibiotic prescription are estimated to be unnecessary. Data are lacking on the rates of associated ADEs.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Synopsis: Of the 5,579 patients admitted to four inpatient medicine services between September 2013 and June 2014, 1,488 (27%) received antibiotics for at least 24 hours. Patients were followed through admission and out to 90 days. A total of 324 unique antibiotic-associated ADEs occurred among 298 (20%) patients within 90 days of initial therapy. The overall rate of antibiotic-associated ADEs was 22.9/10,000 person-days. The investigators determined that 287 (19%) of antibiotic regimens were not clinically indicated, and among those, there were 56 (20%) ADEs. The most common 30-day ADEs were gastrointestinal, renal, and hematologic. The highest proportion of ADEs occurred with beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, intravenous vancomycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, perhaps reflecting how commonly these agents are prescribed. Nearly all ADEs were considered clinically significant (97%). There were no deaths attributable to antibiotic-associated ADEs.

Bottom line: Antibiotic associated ADEs occur in about one in five inpatients, and about one in five antibiotic prescriptions may not be clinically indicated.

Citation: Tamma PD et al. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;177(9):1308-15.

Dr. Anderson is an associate program director in the internal medicine residency training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a hospitalist at the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System in Denver.

FDA: No more codeine or hydrocodone cold medicines for children

New safety labeling changes for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone limit their use to adults 18 years or older.

The Food and Drug Administration took this action after “conducting an extensive review and convening a panel of outside experts,” which determined that the risks of these medicines outweigh their benefits in children younger than 18 years. The agency also is requiring companies to add a boxed warning to drug labels for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone about the “risks of misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, death, and slowed or difficult breathing,” according to an FDA safety announcement.

Common side effects of opioids include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, shortness of breath, and headache, according to the press release.

Reassure parents that cough because of a cold or upper respiratory infection is self-limited and generally does not need to be treated, the FDA advised. If children do need cough treatment, there are over-the-counter products such as dextromethorphan, as well as prescription benzonatate products, the FDA said. Encourage parents to check labels of nonprescription cough and cold products.

In a few states, some codeine cough medicines are available OTC. The FDA is considering regulatory action for these products, according to the safety announcement.

New safety labeling changes for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone limit their use to adults 18 years or older.

The Food and Drug Administration took this action after “conducting an extensive review and convening a panel of outside experts,” which determined that the risks of these medicines outweigh their benefits in children younger than 18 years. The agency also is requiring companies to add a boxed warning to drug labels for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone about the “risks of misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, death, and slowed or difficult breathing,” according to an FDA safety announcement.

Common side effects of opioids include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, shortness of breath, and headache, according to the press release.

Reassure parents that cough because of a cold or upper respiratory infection is self-limited and generally does not need to be treated, the FDA advised. If children do need cough treatment, there are over-the-counter products such as dextromethorphan, as well as prescription benzonatate products, the FDA said. Encourage parents to check labels of nonprescription cough and cold products.

In a few states, some codeine cough medicines are available OTC. The FDA is considering regulatory action for these products, according to the safety announcement.

New safety labeling changes for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone limit their use to adults 18 years or older.

The Food and Drug Administration took this action after “conducting an extensive review and convening a panel of outside experts,” which determined that the risks of these medicines outweigh their benefits in children younger than 18 years. The agency also is requiring companies to add a boxed warning to drug labels for prescription cough and cold medicines containing codeine or hydrocodone about the “risks of misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, death, and slowed or difficult breathing,” according to an FDA safety announcement.

Common side effects of opioids include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, shortness of breath, and headache, according to the press release.

Reassure parents that cough because of a cold or upper respiratory infection is self-limited and generally does not need to be treated, the FDA advised. If children do need cough treatment, there are over-the-counter products such as dextromethorphan, as well as prescription benzonatate products, the FDA said. Encourage parents to check labels of nonprescription cough and cold products.

In a few states, some codeine cough medicines are available OTC. The FDA is considering regulatory action for these products, according to the safety announcement.

Check orthostatic vital signs within 1 minute

Clinical question: What is the relationship between timing of measurement of postural blood pressure (BP) and adverse clinical outcomes?

Background: Guidelines recommend measuring postural BP after 3 minutes of standing to avoid potentially false-positive readings obtained before that interval. In SPRINT, orthostatic hypotension (OH) determined at 1 minute was associated with higher risk of emergency department visits for OH and syncope. Whether that finding was because of the shortened interval of measurement is uncertain.

Setting: Four U.S. communities over 2 decades.

Synopsis: In a cohort of 11,429 middle-aged patients, upright BP was measured every 25 seconds over a 5-minute interval after participants had been supine for 20 minutes. About 2-3 seconds elapsed between the end of one BP measurement and the initiation of the next. OH was defined as a 20–mm Hg drop in systolic BP. After researchers adjusted for covariates, OH at 30 seconds and 1 minute were associated with higher odds of dizziness, fracture, syncope, death, and motor vehicle crashes recorded over a median follow-up of 23 years. Measurements after 1 minute were not reliably associated with any adverse outcomes.

Bottom line: Measuring OH at 30 seconds and 1 minute reliably identifies patients at risk for associated adverse clinical outcomes.

Citation: Juraschek SP et al. Association of history of dizziness and long-term adverse outcomes with early vs. later orthostatic hypotension times in middle-aged adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;177(9):1316-23.

Dr. Anderson is an associate program director in the internal medicine residency training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a hospitalist at the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System in Denver.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between timing of measurement of postural blood pressure (BP) and adverse clinical outcomes?

Background: Guidelines recommend measuring postural BP after 3 minutes of standing to avoid potentially false-positive readings obtained before that interval. In SPRINT, orthostatic hypotension (OH) determined at 1 minute was associated with higher risk of emergency department visits for OH and syncope. Whether that finding was because of the shortened interval of measurement is uncertain.

Setting: Four U.S. communities over 2 decades.

Synopsis: In a cohort of 11,429 middle-aged patients, upright BP was measured every 25 seconds over a 5-minute interval after participants had been supine for 20 minutes. About 2-3 seconds elapsed between the end of one BP measurement and the initiation of the next. OH was defined as a 20–mm Hg drop in systolic BP. After researchers adjusted for covariates, OH at 30 seconds and 1 minute were associated with higher odds of dizziness, fracture, syncope, death, and motor vehicle crashes recorded over a median follow-up of 23 years. Measurements after 1 minute were not reliably associated with any adverse outcomes.

Bottom line: Measuring OH at 30 seconds and 1 minute reliably identifies patients at risk for associated adverse clinical outcomes.

Citation: Juraschek SP et al. Association of history of dizziness and long-term adverse outcomes with early vs. later orthostatic hypotension times in middle-aged adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;177(9):1316-23.

Dr. Anderson is an associate program director in the internal medicine residency training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a hospitalist at the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System in Denver.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between timing of measurement of postural blood pressure (BP) and adverse clinical outcomes?

Background: Guidelines recommend measuring postural BP after 3 minutes of standing to avoid potentially false-positive readings obtained before that interval. In SPRINT, orthostatic hypotension (OH) determined at 1 minute was associated with higher risk of emergency department visits for OH and syncope. Whether that finding was because of the shortened interval of measurement is uncertain.

Setting: Four U.S. communities over 2 decades.

Synopsis: In a cohort of 11,429 middle-aged patients, upright BP was measured every 25 seconds over a 5-minute interval after participants had been supine for 20 minutes. About 2-3 seconds elapsed between the end of one BP measurement and the initiation of the next. OH was defined as a 20–mm Hg drop in systolic BP. After researchers adjusted for covariates, OH at 30 seconds and 1 minute were associated with higher odds of dizziness, fracture, syncope, death, and motor vehicle crashes recorded over a median follow-up of 23 years. Measurements after 1 minute were not reliably associated with any adverse outcomes.

Bottom line: Measuring OH at 30 seconds and 1 minute reliably identifies patients at risk for associated adverse clinical outcomes.

Citation: Juraschek SP et al. Association of history of dizziness and long-term adverse outcomes with early vs. later orthostatic hypotension times in middle-aged adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;177(9):1316-23.

Dr. Anderson is an associate program director in the internal medicine residency training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a hospitalist at the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System in Denver.

Optimal rate of flow for high-flow nasal cannula in young children

Clinical question

Is there an optimal rate of flow for high-flow nasal cannula in respiratory distress?

Background

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) has been increasingly used to treat children with moderate to severe bronchiolitis, both in intensive care unit (ICU) settings and on inpatient wards. Studies have shown it may allow children with bronchiolitis to avoid ICU admission and intubation. In preterm infants it has been shown to decrease work of breathing. No prior studies, however, have examined optimizing the rate of flow for individual patients, and considerable heterogeneity exists in choosing initial HFNC flow rates.

Reliably measuring effort of breathing has proved challenging. Placing a manometer in the esophagus allows measurement of the pressure-rate product (PRP), a previously validated measure of effort of breathing computed by multiplying the difference between maximum and minimum esophageal pressures by the respiratory rate.1 An increasing PRP indicates increasing effort of breathing. The authors chose systems from Fisher & Paykel and Vapotherm for their testing.

Study design

Single-center prospective observational trial.

Setting

24-bed pediatric intensive care unit in a 347-bed urban free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A single center recruited patients aged 37 weeks corrected gestational age to 3 years who were admitted to the ICU with respiratory distress. Fifty-four patients met inclusion criteria and 21 were enrolled and completed the study. Prior data suggested a sample size of 20 would be sufficient to identify a clinically significant effect size. Median age was 6 months.

Thirteen patients had bronchiolitis, three had pneumonia, and five had other respiratory illnesses. Each patient received HFNC delivered by both systems in sequence with flow rates of 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 L/kg per minute to a maximum of 30 L/min. Following the trials, patients remained on HFNC as per usual care with twice-daily PRP measurements until weaned off HFNC.

A dose-dependent relationship existed between flow and change in PRP, with the greatest reduction in PRP at 2 L/kg per minute flow (P less than .001) and a slightly smaller but similar reduction in PRP at 1.5 L/kg per minute. When stratifying the subjects by weight, this effect was not statistically significant for patients heavier than 8 kg (P = .38), with all significant changes being in patients less than 8 kg (P less than .001) with a median drop in PRP of 25%. Further examining these younger and lighter patients, the greatest reduction in PRP was in the lightest patients (less than 5 kg).

Given the similarity in drop in PRP at 1.5 L/kg per minute and 2 L/kg per minute, the authors suggest this flow rate yields a plateau effect and minimal further improvement would be seen with increasing flow rates. A rate of 2 L/kg per minute was chosen as a maximum a priori as it was judged the highest level of HFNC patients could tolerate without worsening agitation or air leak. There was no difference seen between the two HFNC systems in the study. The authors did not report the fraction of inspired oxygen settings used, the size of HFNC cannulas, or how PRP changed over several days as HFNC was weaned.

Bottom line

The optimal HFNC rate to decrease effort of breathing for children less than 3 years old is between 1.5 and 2 L/kg/min with the greatest improvement expected in children under 5 kg.

Citation

Weiler T et al. The Relationship between High Flow Nasal Cannula Flow Rate and Effort of Breathing in Children. The Journal of Pediatrics. October 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.006.

Reference

1. Argent AC, Newth CJL, Klein M. The mechanics of breathing in children with acute severe croup. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(2):324-32. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0910-x.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia.

Clinical question

Is there an optimal rate of flow for high-flow nasal cannula in respiratory distress?

Background

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) has been increasingly used to treat children with moderate to severe bronchiolitis, both in intensive care unit (ICU) settings and on inpatient wards. Studies have shown it may allow children with bronchiolitis to avoid ICU admission and intubation. In preterm infants it has been shown to decrease work of breathing. No prior studies, however, have examined optimizing the rate of flow for individual patients, and considerable heterogeneity exists in choosing initial HFNC flow rates.

Reliably measuring effort of breathing has proved challenging. Placing a manometer in the esophagus allows measurement of the pressure-rate product (PRP), a previously validated measure of effort of breathing computed by multiplying the difference between maximum and minimum esophageal pressures by the respiratory rate.1 An increasing PRP indicates increasing effort of breathing. The authors chose systems from Fisher & Paykel and Vapotherm for their testing.

Study design

Single-center prospective observational trial.

Setting

24-bed pediatric intensive care unit in a 347-bed urban free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A single center recruited patients aged 37 weeks corrected gestational age to 3 years who were admitted to the ICU with respiratory distress. Fifty-four patients met inclusion criteria and 21 were enrolled and completed the study. Prior data suggested a sample size of 20 would be sufficient to identify a clinically significant effect size. Median age was 6 months.

Thirteen patients had bronchiolitis, three had pneumonia, and five had other respiratory illnesses. Each patient received HFNC delivered by both systems in sequence with flow rates of 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 L/kg per minute to a maximum of 30 L/min. Following the trials, patients remained on HFNC as per usual care with twice-daily PRP measurements until weaned off HFNC.

A dose-dependent relationship existed between flow and change in PRP, with the greatest reduction in PRP at 2 L/kg per minute flow (P less than .001) and a slightly smaller but similar reduction in PRP at 1.5 L/kg per minute. When stratifying the subjects by weight, this effect was not statistically significant for patients heavier than 8 kg (P = .38), with all significant changes being in patients less than 8 kg (P less than .001) with a median drop in PRP of 25%. Further examining these younger and lighter patients, the greatest reduction in PRP was in the lightest patients (less than 5 kg).

Given the similarity in drop in PRP at 1.5 L/kg per minute and 2 L/kg per minute, the authors suggest this flow rate yields a plateau effect and minimal further improvement would be seen with increasing flow rates. A rate of 2 L/kg per minute was chosen as a maximum a priori as it was judged the highest level of HFNC patients could tolerate without worsening agitation or air leak. There was no difference seen between the two HFNC systems in the study. The authors did not report the fraction of inspired oxygen settings used, the size of HFNC cannulas, or how PRP changed over several days as HFNC was weaned.

Bottom line

The optimal HFNC rate to decrease effort of breathing for children less than 3 years old is between 1.5 and 2 L/kg/min with the greatest improvement expected in children under 5 kg.

Citation

Weiler T et al. The Relationship between High Flow Nasal Cannula Flow Rate and Effort of Breathing in Children. The Journal of Pediatrics. October 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.006.

Reference

1. Argent AC, Newth CJL, Klein M. The mechanics of breathing in children with acute severe croup. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(2):324-32. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0910-x.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia.

Clinical question

Is there an optimal rate of flow for high-flow nasal cannula in respiratory distress?

Background

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) has been increasingly used to treat children with moderate to severe bronchiolitis, both in intensive care unit (ICU) settings and on inpatient wards. Studies have shown it may allow children with bronchiolitis to avoid ICU admission and intubation. In preterm infants it has been shown to decrease work of breathing. No prior studies, however, have examined optimizing the rate of flow for individual patients, and considerable heterogeneity exists in choosing initial HFNC flow rates.

Reliably measuring effort of breathing has proved challenging. Placing a manometer in the esophagus allows measurement of the pressure-rate product (PRP), a previously validated measure of effort of breathing computed by multiplying the difference between maximum and minimum esophageal pressures by the respiratory rate.1 An increasing PRP indicates increasing effort of breathing. The authors chose systems from Fisher & Paykel and Vapotherm for their testing.

Study design

Single-center prospective observational trial.

Setting

24-bed pediatric intensive care unit in a 347-bed urban free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A single center recruited patients aged 37 weeks corrected gestational age to 3 years who were admitted to the ICU with respiratory distress. Fifty-four patients met inclusion criteria and 21 were enrolled and completed the study. Prior data suggested a sample size of 20 would be sufficient to identify a clinically significant effect size. Median age was 6 months.

Thirteen patients had bronchiolitis, three had pneumonia, and five had other respiratory illnesses. Each patient received HFNC delivered by both systems in sequence with flow rates of 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 L/kg per minute to a maximum of 30 L/min. Following the trials, patients remained on HFNC as per usual care with twice-daily PRP measurements until weaned off HFNC.

A dose-dependent relationship existed between flow and change in PRP, with the greatest reduction in PRP at 2 L/kg per minute flow (P less than .001) and a slightly smaller but similar reduction in PRP at 1.5 L/kg per minute. When stratifying the subjects by weight, this effect was not statistically significant for patients heavier than 8 kg (P = .38), with all significant changes being in patients less than 8 kg (P less than .001) with a median drop in PRP of 25%. Further examining these younger and lighter patients, the greatest reduction in PRP was in the lightest patients (less than 5 kg).

Given the similarity in drop in PRP at 1.5 L/kg per minute and 2 L/kg per minute, the authors suggest this flow rate yields a plateau effect and minimal further improvement would be seen with increasing flow rates. A rate of 2 L/kg per minute was chosen as a maximum a priori as it was judged the highest level of HFNC patients could tolerate without worsening agitation or air leak. There was no difference seen between the two HFNC systems in the study. The authors did not report the fraction of inspired oxygen settings used, the size of HFNC cannulas, or how PRP changed over several days as HFNC was weaned.

Bottom line

The optimal HFNC rate to decrease effort of breathing for children less than 3 years old is between 1.5 and 2 L/kg/min with the greatest improvement expected in children under 5 kg.

Citation

Weiler T et al. The Relationship between High Flow Nasal Cannula Flow Rate and Effort of Breathing in Children. The Journal of Pediatrics. October 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.006.

Reference

1. Argent AC, Newth CJL, Klein M. The mechanics of breathing in children with acute severe croup. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(2):324-32. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0910-x.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia.

How to manage a patient presenting with syncope

Case

A 38-year-old construction worker without significant medical history presents following witnessed syncope at her job, after standing for at least 2 hours on a particularly warm day. She reported an episode of syncope under similar circumstances 2 months prior. With each episode, she experienced “tunneling” of peripheral vision, then loss of consciousness without palpitations or incontinence. Her physical exam, vital signs (including orthostatic blood pressures), labs, and ECG were unremarkable.

Brief overview

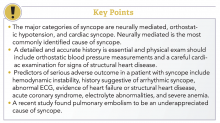

The American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society guidelines define syncope as “a symptom that presents with an abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery” with cerebral hypoperfusion as the presumed mechanism.1 Furthermore, “there should not be clinical features of other nonsyncope causes of loss of consciousness, such as seizure, antecedent head trauma, or apparent loss of consciousness (that is, pseudosyncope).”1

A careful history revolving around the patient’s behavior prior to, during, and following the event, a thorough past medical history, and a review of current medications are essential. Potential obstacles in obtaining details of the event include lack of witnesses, patient’s inability to recall the experience, and inaccurate description of convulsive syncope as a “seizure” by bystanders.2

Overview of data

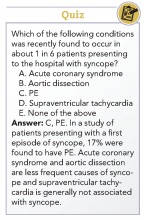

Obtaining a detailed history is crucial to understanding both the etiology of the syncopal event and determining which patients are at high risk for adverse outcomes. The etiology of syncope can be determined by history alone in 26% of patients younger than 65 years.3 Data on the prevalence of syncope by cause varies widely. As a general rule, in younger patients, especially those under 40 years of age, neurally mediated syncope is most common. As patients age, orthostatic hypotension and cardiac causes (including arrhythmias and structural diseases) occur more frequently, though neurally mediated syncope is still the most common.

Many of these predictors, however, would raise the clinical suspicion of most hospitalists for adverse outcomes in their hospitalized patients independent of the presence or absence of syncope. In fact, a meta-analysis has concluded that “None of the evaluated prediction tools (SFSR, EGSYS) performed better than clinical judgment in identifying serious outcomes during emergency department stay, and at 10 and 30 days after syncope.”6

Once the patient is hospitalized, further evaluation should be based on a careful history and physical examination. Standard evaluation also includes careful review of medications, an ECG to exclude findings suggestive of arrhythmias as well as structural or coronary artery disease, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements.1 Additional tests should be considered as deemed appropriate. For example, in patients over 40 years of age without history of carotid artery disease or stroke and in whom no carotid artery bruit is appreciated, a carotid sinus massage may be considered. The correct technique is to massage the sinus on the right then left, each for 5 seconds in both supine and standing positions with continuous heart rate and frequent blood pressure monitoring. Reproduction of syncope, especially concurrent with a cardiac pause of greater than 3 seconds and a systolic blood pressure drop of greater than 50 mmHg, is considered a positive test. Tilt-table testing should be considered in those for whom neurally mediated syncope is suspected but not confirmed, or in patients who might benefit from further elucidation of their prodromal symptoms.

Of note, a study recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the prevalence of PE in patients (median age, 80 years) presenting with a first episode of syncope was 17%, a rate that is substantially higher than historically presumed.8 Although the prevalence of PE was highest among patients presenting with syncope of unclear origin (25%), nearly 13% of patients with other explanations for syncope also had PE.

Application of data

Bottom Line

Dr. Roberts, Dr. Krason, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Shen W-K et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;70(5):e39-e110.

2. Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):377-85.

3. Del Rosso A et al. Relation of clinical presentation of syncope to the age of patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Nov 15;96(10):1431-5.

4. Blanc JJ. Syncope: Definition, epidemiology, and classification. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):341-5.

5. Matthews IG et al. Syncope in the older person. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):411-21.

6. Costantino G et al. Syncope risk stratification tools vs clinical judgment: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2014 Nov;127(11):1126.e13-25.

7. Chiu DT et al. Are echocardiography, telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring, and cardiac enzymes in emergency department patients presenting with syncope useful tests? A preliminary investigation. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:113-8.

8. Prandoni P et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct;375(20):1524-31.

9. Sheldon RS et al. Standardized approaches to the investigation of syncope: Canadian Cardiovascular Society position paper. Can J Cardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;27(2):246-253.

10. Moya A et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009 Nov;30(21):2631-71.

Additional reading

1. Brignole M, Hamdan MH. New concepts in the assessment of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 May; 59(18):1583-91.

2. Rosanio S et al. Syncope in adults: systematic review and proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Int J Cardiol. 2013 Jan;162(3):149-57.

Case

A 38-year-old construction worker without significant medical history presents following witnessed syncope at her job, after standing for at least 2 hours on a particularly warm day. She reported an episode of syncope under similar circumstances 2 months prior. With each episode, she experienced “tunneling” of peripheral vision, then loss of consciousness without palpitations or incontinence. Her physical exam, vital signs (including orthostatic blood pressures), labs, and ECG were unremarkable.

Brief overview

The American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society guidelines define syncope as “a symptom that presents with an abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery” with cerebral hypoperfusion as the presumed mechanism.1 Furthermore, “there should not be clinical features of other nonsyncope causes of loss of consciousness, such as seizure, antecedent head trauma, or apparent loss of consciousness (that is, pseudosyncope).”1

A careful history revolving around the patient’s behavior prior to, during, and following the event, a thorough past medical history, and a review of current medications are essential. Potential obstacles in obtaining details of the event include lack of witnesses, patient’s inability to recall the experience, and inaccurate description of convulsive syncope as a “seizure” by bystanders.2

Overview of data

Obtaining a detailed history is crucial to understanding both the etiology of the syncopal event and determining which patients are at high risk for adverse outcomes. The etiology of syncope can be determined by history alone in 26% of patients younger than 65 years.3 Data on the prevalence of syncope by cause varies widely. As a general rule, in younger patients, especially those under 40 years of age, neurally mediated syncope is most common. As patients age, orthostatic hypotension and cardiac causes (including arrhythmias and structural diseases) occur more frequently, though neurally mediated syncope is still the most common.

Many of these predictors, however, would raise the clinical suspicion of most hospitalists for adverse outcomes in their hospitalized patients independent of the presence or absence of syncope. In fact, a meta-analysis has concluded that “None of the evaluated prediction tools (SFSR, EGSYS) performed better than clinical judgment in identifying serious outcomes during emergency department stay, and at 10 and 30 days after syncope.”6

Once the patient is hospitalized, further evaluation should be based on a careful history and physical examination. Standard evaluation also includes careful review of medications, an ECG to exclude findings suggestive of arrhythmias as well as structural or coronary artery disease, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements.1 Additional tests should be considered as deemed appropriate. For example, in patients over 40 years of age without history of carotid artery disease or stroke and in whom no carotid artery bruit is appreciated, a carotid sinus massage may be considered. The correct technique is to massage the sinus on the right then left, each for 5 seconds in both supine and standing positions with continuous heart rate and frequent blood pressure monitoring. Reproduction of syncope, especially concurrent with a cardiac pause of greater than 3 seconds and a systolic blood pressure drop of greater than 50 mmHg, is considered a positive test. Tilt-table testing should be considered in those for whom neurally mediated syncope is suspected but not confirmed, or in patients who might benefit from further elucidation of their prodromal symptoms.

Of note, a study recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the prevalence of PE in patients (median age, 80 years) presenting with a first episode of syncope was 17%, a rate that is substantially higher than historically presumed.8 Although the prevalence of PE was highest among patients presenting with syncope of unclear origin (25%), nearly 13% of patients with other explanations for syncope also had PE.

Application of data

Bottom Line

Dr. Roberts, Dr. Krason, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Shen W-K et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;70(5):e39-e110.

2. Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):377-85.

3. Del Rosso A et al. Relation of clinical presentation of syncope to the age of patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Nov 15;96(10):1431-5.

4. Blanc JJ. Syncope: Definition, epidemiology, and classification. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):341-5.

5. Matthews IG et al. Syncope in the older person. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):411-21.

6. Costantino G et al. Syncope risk stratification tools vs clinical judgment: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2014 Nov;127(11):1126.e13-25.

7. Chiu DT et al. Are echocardiography, telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring, and cardiac enzymes in emergency department patients presenting with syncope useful tests? A preliminary investigation. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:113-8.

8. Prandoni P et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct;375(20):1524-31.

9. Sheldon RS et al. Standardized approaches to the investigation of syncope: Canadian Cardiovascular Society position paper. Can J Cardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;27(2):246-253.

10. Moya A et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009 Nov;30(21):2631-71.

Additional reading

1. Brignole M, Hamdan MH. New concepts in the assessment of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 May; 59(18):1583-91.

2. Rosanio S et al. Syncope in adults: systematic review and proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Int J Cardiol. 2013 Jan;162(3):149-57.

Case

A 38-year-old construction worker without significant medical history presents following witnessed syncope at her job, after standing for at least 2 hours on a particularly warm day. She reported an episode of syncope under similar circumstances 2 months prior. With each episode, she experienced “tunneling” of peripheral vision, then loss of consciousness without palpitations or incontinence. Her physical exam, vital signs (including orthostatic blood pressures), labs, and ECG were unremarkable.

Brief overview

The American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society guidelines define syncope as “a symptom that presents with an abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery” with cerebral hypoperfusion as the presumed mechanism.1 Furthermore, “there should not be clinical features of other nonsyncope causes of loss of consciousness, such as seizure, antecedent head trauma, or apparent loss of consciousness (that is, pseudosyncope).”1

A careful history revolving around the patient’s behavior prior to, during, and following the event, a thorough past medical history, and a review of current medications are essential. Potential obstacles in obtaining details of the event include lack of witnesses, patient’s inability to recall the experience, and inaccurate description of convulsive syncope as a “seizure” by bystanders.2

Overview of data

Obtaining a detailed history is crucial to understanding both the etiology of the syncopal event and determining which patients are at high risk for adverse outcomes. The etiology of syncope can be determined by history alone in 26% of patients younger than 65 years.3 Data on the prevalence of syncope by cause varies widely. As a general rule, in younger patients, especially those under 40 years of age, neurally mediated syncope is most common. As patients age, orthostatic hypotension and cardiac causes (including arrhythmias and structural diseases) occur more frequently, though neurally mediated syncope is still the most common.

Many of these predictors, however, would raise the clinical suspicion of most hospitalists for adverse outcomes in their hospitalized patients independent of the presence or absence of syncope. In fact, a meta-analysis has concluded that “None of the evaluated prediction tools (SFSR, EGSYS) performed better than clinical judgment in identifying serious outcomes during emergency department stay, and at 10 and 30 days after syncope.”6

Once the patient is hospitalized, further evaluation should be based on a careful history and physical examination. Standard evaluation also includes careful review of medications, an ECG to exclude findings suggestive of arrhythmias as well as structural or coronary artery disease, and orthostatic blood pressure measurements.1 Additional tests should be considered as deemed appropriate. For example, in patients over 40 years of age without history of carotid artery disease or stroke and in whom no carotid artery bruit is appreciated, a carotid sinus massage may be considered. The correct technique is to massage the sinus on the right then left, each for 5 seconds in both supine and standing positions with continuous heart rate and frequent blood pressure monitoring. Reproduction of syncope, especially concurrent with a cardiac pause of greater than 3 seconds and a systolic blood pressure drop of greater than 50 mmHg, is considered a positive test. Tilt-table testing should be considered in those for whom neurally mediated syncope is suspected but not confirmed, or in patients who might benefit from further elucidation of their prodromal symptoms.

Of note, a study recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the prevalence of PE in patients (median age, 80 years) presenting with a first episode of syncope was 17%, a rate that is substantially higher than historically presumed.8 Although the prevalence of PE was highest among patients presenting with syncope of unclear origin (25%), nearly 13% of patients with other explanations for syncope also had PE.

Application of data

Bottom Line

Dr. Roberts, Dr. Krason, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Shen W-K et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 1;70(5):e39-e110.

2. Sheldon R. How to differentiate syncope from seizure. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):377-85.

3. Del Rosso A et al. Relation of clinical presentation of syncope to the age of patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Nov 15;96(10):1431-5.

4. Blanc JJ. Syncope: Definition, epidemiology, and classification. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):341-5.

5. Matthews IG et al. Syncope in the older person. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):411-21.

6. Costantino G et al. Syncope risk stratification tools vs clinical judgment: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2014 Nov;127(11):1126.e13-25.

7. Chiu DT et al. Are echocardiography, telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring, and cardiac enzymes in emergency department patients presenting with syncope useful tests? A preliminary investigation. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:113-8.

8. Prandoni P et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct;375(20):1524-31.

9. Sheldon RS et al. Standardized approaches to the investigation of syncope: Canadian Cardiovascular Society position paper. Can J Cardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;27(2):246-253.

10. Moya A et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009 Nov;30(21):2631-71.

Additional reading

1. Brignole M, Hamdan MH. New concepts in the assessment of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 May; 59(18):1583-91.

2. Rosanio S et al. Syncope in adults: systematic review and proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Int J Cardiol. 2013 Jan;162(3):149-57.

Thrombectomy shines in presence of a clinical deficit and imaging mismatch

, according to Raul G. Nogueira, MD, and his DAWN trial coinvestigators.

A total of 206 patients who had experienced occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid artery or proximal middle cerebral artery in the past 6-24 hours were included in the study – 107 receiving thrombectomy with the Trevo device plus standard care and 99 receiving standard care alone. After 90 days of treatment, the mean utility-weighted modified Rankin scale score for patients who received thrombectomy was 5.5, compared with 3.4 in the control group. The rate of functional independence was 49% in the thrombectomy group and 13% in the control group.

“Further studies are needed to establish the prevalence of patients who would be eligible for thrombectomy among the entire population of patients with ischemic stroke. Further studies are also needed to determine whether late thrombectomy has a benefit when more widely available imaging techniques are used to estimate the infarct volume at presentation, such as assessment of the extent of hypodensity on non–contrast-enhanced CT,” the investigators noted.

SOURCE: Nogueira R et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:11-21

, according to Raul G. Nogueira, MD, and his DAWN trial coinvestigators.

A total of 206 patients who had experienced occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid artery or proximal middle cerebral artery in the past 6-24 hours were included in the study – 107 receiving thrombectomy with the Trevo device plus standard care and 99 receiving standard care alone. After 90 days of treatment, the mean utility-weighted modified Rankin scale score for patients who received thrombectomy was 5.5, compared with 3.4 in the control group. The rate of functional independence was 49% in the thrombectomy group and 13% in the control group.

“Further studies are needed to establish the prevalence of patients who would be eligible for thrombectomy among the entire population of patients with ischemic stroke. Further studies are also needed to determine whether late thrombectomy has a benefit when more widely available imaging techniques are used to estimate the infarct volume at presentation, such as assessment of the extent of hypodensity on non–contrast-enhanced CT,” the investigators noted.

SOURCE: Nogueira R et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:11-21

, according to Raul G. Nogueira, MD, and his DAWN trial coinvestigators.

A total of 206 patients who had experienced occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid artery or proximal middle cerebral artery in the past 6-24 hours were included in the study – 107 receiving thrombectomy with the Trevo device plus standard care and 99 receiving standard care alone. After 90 days of treatment, the mean utility-weighted modified Rankin scale score for patients who received thrombectomy was 5.5, compared with 3.4 in the control group. The rate of functional independence was 49% in the thrombectomy group and 13% in the control group.

“Further studies are needed to establish the prevalence of patients who would be eligible for thrombectomy among the entire population of patients with ischemic stroke. Further studies are also needed to determine whether late thrombectomy has a benefit when more widely available imaging techniques are used to estimate the infarct volume at presentation, such as assessment of the extent of hypodensity on non–contrast-enhanced CT,” the investigators noted.

SOURCE: Nogueira R et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:11-21

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Majority of influenza-related deaths among hospitalized patients occur after discharge

SAN DIEGO – Over half of hospitalized, influenza-related deaths occurred within 30 days of discharge, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

As physicians and pharmaceutical companies attempt to measure the burden of seasonal influenza, discharged patients are currently not considered as much as they should be, according to investigators.

Among 968 deceased patients studied, 444 (46%) died in hospital, while 524 (54%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 15,562 patients hospitalized for influenza-related cases between 2014 and 2015, as recorded in Influenza-Associated Hospitalizations Surveillance (FluSurv-NET), a database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of the studied patients were women (55%) and the majority were white.

Those who died were more likely to have been admitted to the hospital immediately after influenza onset, with 26% of those who died after discharge and 22% of those who died in hospital having been admitted the same day. In contrast, 13% of those who lived past 30 days were admitted immediately after onset.

A total of 46% of those who died after hospitalization had a length of stay longer than 1 week, compared to 15% of those who lived.

Among patients who died after discharge, 356 (68%) died within 2 weeks of discharge, with the highest number of deaths occurring within the first few days, according to presenter Craig McGowan of the Influenza Division of the CDC in Atlanta.

Age also seemed to be a possible mortality predictor, according to Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators. “Those who died were more likely to be elderly, and those who died after discharge were even more likely to be 85 [years or older] than those who died during their influenza-related hospitalizations,” said Mr. McGowan, who added that patients aged 85 years and older made up more than half of those who died after discharge.

Patients who died in hospital were significantly more likely to have influenza listed as a cause of death. Overall, influenza-related and non–influenza-related respiratory issues were the two most common causes of death listed on death certificates of patients who died during hospitalization or within 14 days of discharge, while cardiovascular or other symptoms were listed for those who died between 15 and 30 days after discharge.

Admission and discharge locations among patients who did not die were almost 80% from a private residence to a private residence, while observations of those who died revealed a different pattern. “Those individuals who died after discharge were almost evenly split between admission from a nursing home or a private residence,” Mr. McGowan said. “Those who were admitted from the nursing home were almost exclusively discharged to either hospice care or back to a nursing home.”

Mr. McGowan noted rehospitalization to be a significant factor among those who died, with 34% of deaths occurring back in the hospital after initial discharge.

Influenza testing of studied patients was given at clinicians’ discretion, which may make the sample not generalizable to the overall influenza population, and the investigators included only bivariate associations, which means there were likely confounding effects that could not be accounted for.

Mr. McGowan and his fellow investigators plan to expand their research by determining underlying causes of death in these patients, to create more accurate estimates of influenza-associated mortality.

Mr. McGowan reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: McGowan, C., et al., ID Week 2017, Abstract 951.

SAN DIEGO – Over half of hospitalized, influenza-related deaths occurred within 30 days of discharge, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

As physicians and pharmaceutical companies attempt to measure the burden of seasonal influenza, discharged patients are currently not considered as much as they should be, according to investigators.

Among 968 deceased patients studied, 444 (46%) died in hospital, while 524 (54%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Investigators conducted a retrospective study of 15,562 patients hospitalized for influenza-related cases between 2014 and 2015, as recorded in Influenza-Associated Hospitalizations Surveillance (FluSurv-NET), a database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The majority of the studied patients were women (55%) and the majority were white.

Those who died were more likely to have been admitted to the hospital immediately after influenza onset, with 26% of those who died after discharge and 22% of those who died in hospital having been admitted the same day. In contrast, 13% of those who lived past 30 days were admitted immediately after onset.

A total of 46% of those who died after hospitalization had a length of stay longer than 1 week, compared to 15% of those who lived.

Among patients who died after discharge, 356 (68%) died within 2 weeks of discharge, with the highest number of deaths occurring within the first few days, according to presenter Craig McGowan of the Influenza Division of the CDC in Atlanta.