User login

2022 Update on cervical disease

Cervical cancer is an important global health problem with an estimated 604,127 new cases and 341,831 deaths in 2020.1 Nearly 85% of the disease burden affects individuals from low and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) set forth the goal for all countries to reach and maintain an incidence rate of below 4 per 100,000 women by 2030 as part of the Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer.

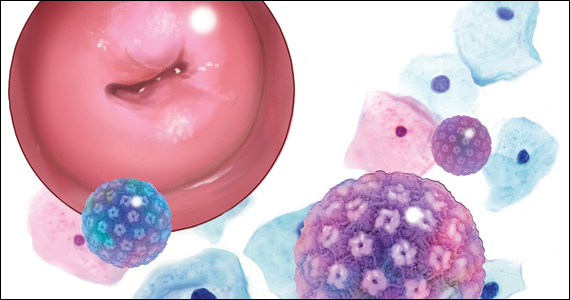

Although traditional Pap cytology has been the cornerstone of screening programs, its poor sensitivity of approximately 50% and limitations in accessibility require new strategies to achieve the elimination of cervical cancer.2 The discovery that persistent infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) is an essential step in the development of cervical cancer led to the development of diagnostic HPV tests, which have higher sensitivity than cytology (96.1% vs 53.0%) but somewhat lower specificity (90.7% vs 96.3%) for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or worse lesions.2 Initially, HPV testing was incorporated as a method to triage atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) cytology results.3 Later, the concept of cotesting with cytology emerged,4,5 and since then, several clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of primary HPV screening.6-9

In 2020, the WHO recommended HPV DNA testing as the primary screening method starting at the age of 30 years, with regular testing every 5 to 10 years, for the general population.10 Currently, primary HPV has been adopted in multiple countries, including Australia, the Netherlands, Turkey, England, and Argentina.

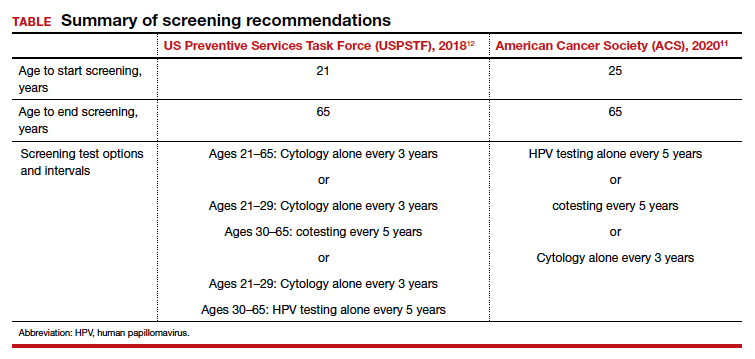

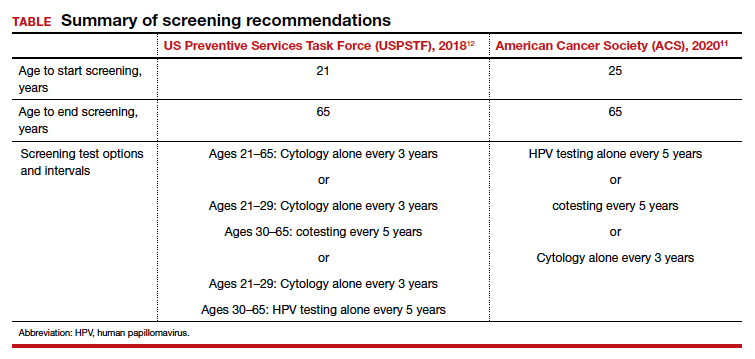

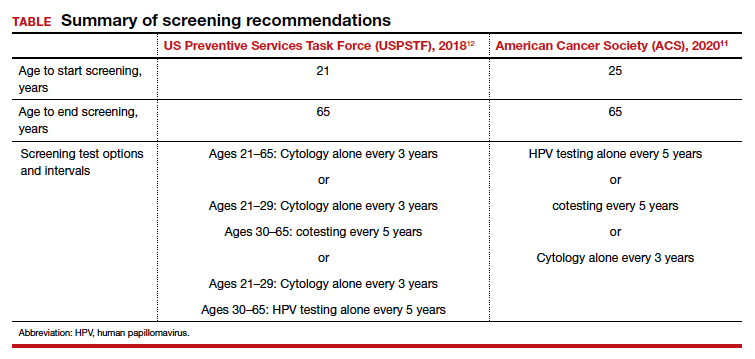

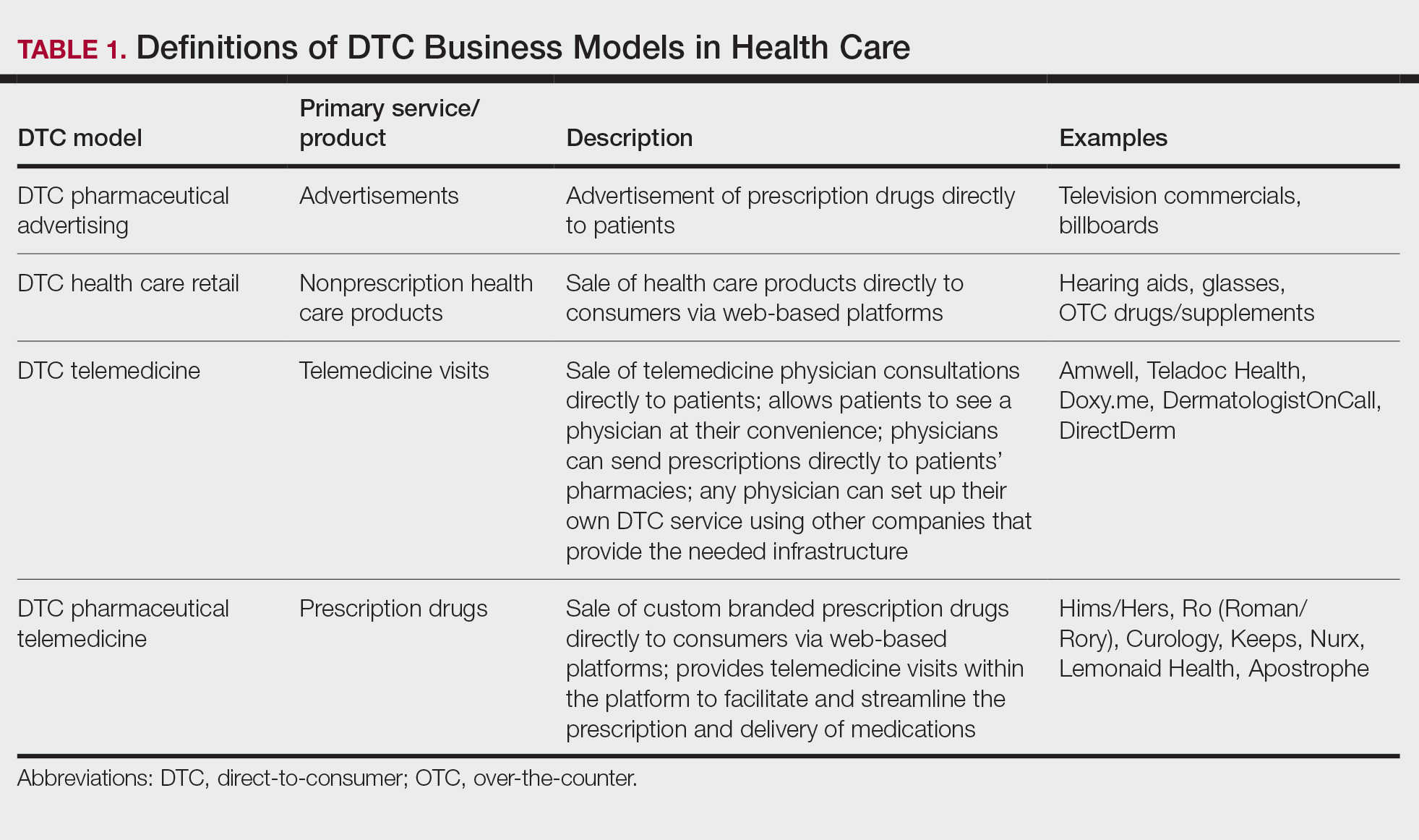

In the United States, there are 3 currently acceptable screening strategies: cytology, cytology plus HPV (cotesting), and primary HPV testing (TABLE). The American Cancer Society (ACS) specifically states that HPV testing alone every 5 years is preferred starting at age 25 years; cotesting every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years are also acceptable.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that cytology alone every 3 years starting at 21 years and then HPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years or cytology every 3 years starting at age 30 are all acceptable strategies.12

When applying these guidelines, it is important to note that they are intended for the screening of patients with all prior normal results with no symptoms. These routine screening guidelines do not apply to special populations, such as those with a history of abnormal results or treatment, a history of immunosuppression,13 a history of HPV-related vulvar or vaginal dysplasia,14-16 or a history of hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no prior history of cervical dysplasia.17,18 By contrast, surveillance is interval testing for those who have either an abnormal prior test result or treatment; these may be managed per risk-based estimates provided by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP).18,19 Finally, diagnosis is evaluation (which may include diagnostic cytology) of a patient with abnormal signs and/or symptoms (such as bleeding, pain, discharge, or cervical mass).

In this Update, we present the evidence for primary HPV testing, the management options for a positive result in the United States, and research that will improve uptake of primary HPV testing as well as accessibility.

Change in screening paradigm: Evidence for primary HPV testing

HPV DNA tests are multiplex assays that detect the DNA of targeted high-risk HPV types, using multiple probes, either by direct genomic detection or by amplification of a viral DNA fragment using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).20,21 Alternatively, HPV mRNA-based tests detect the expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins, a marker of viral integration.20 In examining the data from well-conducted clinical trials, 2 important observations are that different HPV assays were used and that direct comparison may not be valid. In addition, not all tests used in the studies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary HPV testing.

Continue to: FDA-approved HPV tests...

FDA-approved HPV tests

Currently, 2 tests are FDA approved for primary HPV screening. The Cobas HPV test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) was the first FDA-approved test for primary HPV screening in women aged 25 years and older.6 This test reports pooled results from 12 high-risk (hr) HPV types (31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/66/68) with reflex genotyping for HPV 16/18, and thus it provides an immediate triage option for HPV-positive women. Of note, it is also approved for cotesting. The second FDA-approved test is the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company) for primary HPV screening.22 It detects 14 hrHPV types, types 16/18/45 specifically as well as types 31/33/35/39/51/52/56/58/59/66/68.

Other HPV tests are FDA approved for cotesting and reflex testing but not for primary HPV testing. The Hybrid Capture test, or HC2 (Qiagen Inc), was the first HPV test to be approved by the FDA in 1997 for reflex testing of women with ASCUS cytology. In 2003, it was approved for cotesting along with cytology in women aged 30 years and older.20,21 In 2009, the Cervista HPV HR test (Hologic Inc) was approved for cotesting. The Aptima HPV assay (Hologic Inc), which is also approved for cotesting, is an RNA-based assay that allows detection of E6/E7 mRNA transcripts of 14 HPV types.23

Comparing HPV testing with cytology

Ronco and colleagues pooled data from 4 European randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—Swedescreen, POBASCAM, NTCC, ARTISTIC—with a total of 176,464 participants randomly assigned to HPV or cytology screening.24 Swedescreen and POBASCAM used GP5/GP6 PCR, while ARTISTIC and NTCC used HC2 for primary HPV screening. The screening interval was 3 years in all except 5 years in POBASCAM. The pooled detection rate of invasive disease was similar in the 2 arms, with pooled rate ratio for cancer detection being 0.79 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46–1.36) in the first 2.5 years, but was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.25–0.81), favoring the HPV arm, after 2.5 years. HPV testing was more effective in preventing cases of adenocarcinoma than squamous cell carcinoma (0.31 [95% CI, 0.14–0.69] vs 0.78 [95% CI, 0.49–1.25]). The authors concluded that HPV-based screening from age 30 years provided 60% to 70% better protection than cytology.

The result of the above meta-analysis was confirmed by the HPV FOCAL RCT that investigated the efficacy of HPV testing (HC2) in comparison with cytology.25 The detection rates for CIN 3 lesions supported primary HPV screening, with an absolute difference in incidence rate of 2.67/1,000 (95% CI, 0.53–4.88) at study randomization and 3.22/1,000 (95% CI, 5.12–1.48) at study exit 4 years later.

Cotesting using HPV and cytology: Marginal benefit

Dillner and colleagues were one of the first groups to report on the risk of CIN 3 based on both HPV and cytology status.26 Using pooled analysis of data from multiple countries, these investigators reported that the cumulative incidence rates (CIR) of CIN 3 after 6 years of follow-up increased consistently in HPV-positive subjects, and an HPV-positive result more accurately predicted CIN 3+ at 5 years than cytology alone. Furthermore, HPV negativity provided greater reassurance than cytology alone. At 5 years of follow-up, the rates of CIN 3+ were 0.25% (0.12%–0.41%) for women negative for HPV compared with 0.83% (0.50%–1.13%) for women with negative cytology results. There was little difference in rates for CIN 3+ between women with negative results on both tests and women who were negative for HPV.

The important question is then the marginal benefit of cotesting, which is the most costly screening option. A study of 331,818 women enrolled for cotesting at Kaiser Permanente found that the risk of CIN 3+ predicted by HPV testing alone when compared with cytology was significantly higher at both 3 years (5.0% vs 3.8%; P = .046) and 5 years (7.6% vs 4.7%; P = .001).27 A negative cytology result did not decrease the risk of CIN 3 further for HPV-negative patients (3 years: 0.047% vs 0.063%, P = .6; 5 years: 0.16% vs 0.17%, P = .8). They concluded that a negative HPV test was enough reassurance for low risk of CIN 3+ and that an additional negative cytology result does not provide extra reassurance.

Furthermore, a systematic meta-analysis of 48 studies, including 8 RCTs, found that the addition of cytology to HPV testing raised the sensitivity by 2% for CIN 3 compared with HPV testing alone. This improvement in sensitivity was at the expense of considerable loss of specificity, with a ratio of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.92–0.95) for CIN 3.28 Schiffman and colleagues also assessed the relative contribution of HPV testing and cytology in detection of CIN 3 and cancer.29 The HPV component alone identified a significantly higher proportion of preinvasive and invasive disease than cytology. Only 3.5% of precancers and 5.9% of cancers were preceded by HPV-negative, cytology-positive results. Thus, cytology contributed only 5 cases per million women per year to the sensitivity of the combined test, at the cost of significantly more colposcopies. Hence, the evidence suggests that there is limited benefit of adding cytology to HPV testing.30

Continue to: Triage of a positive HPV result...

Triage of a positive HPV result

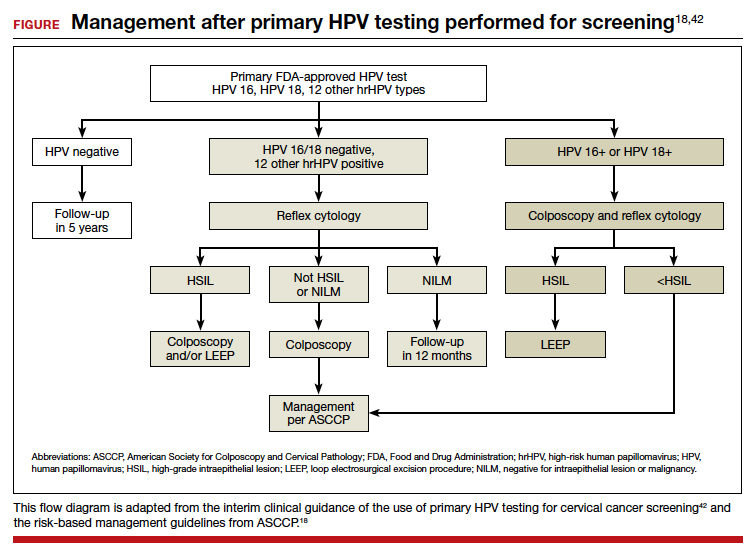

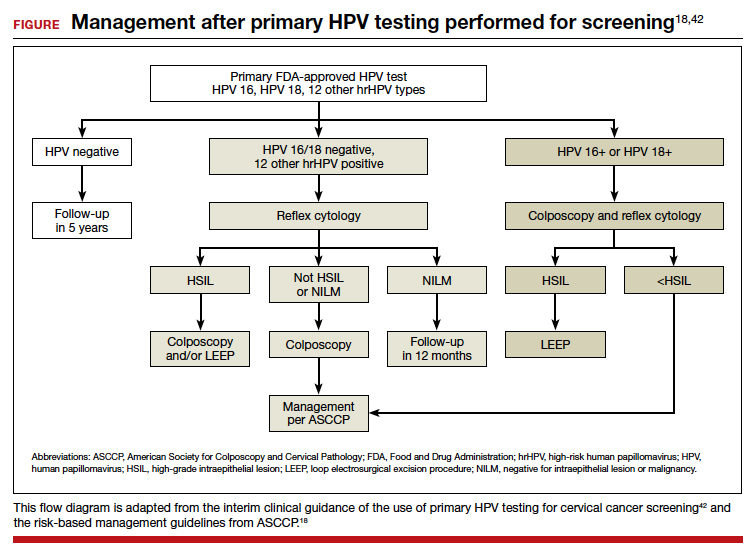

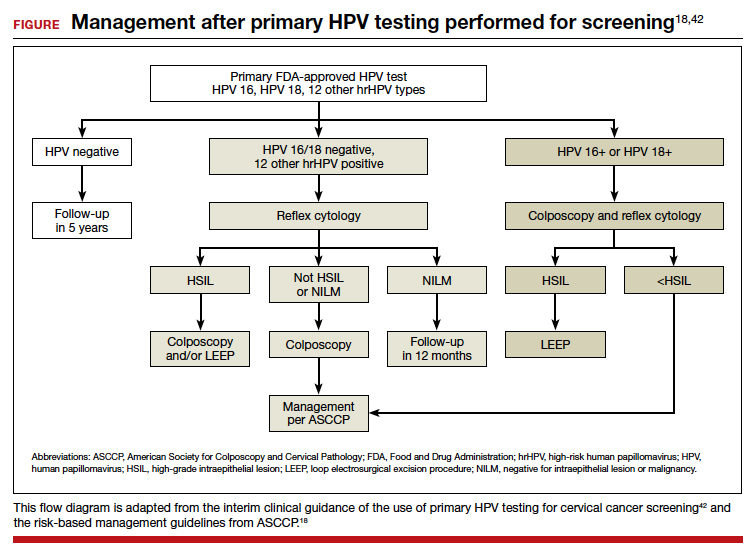

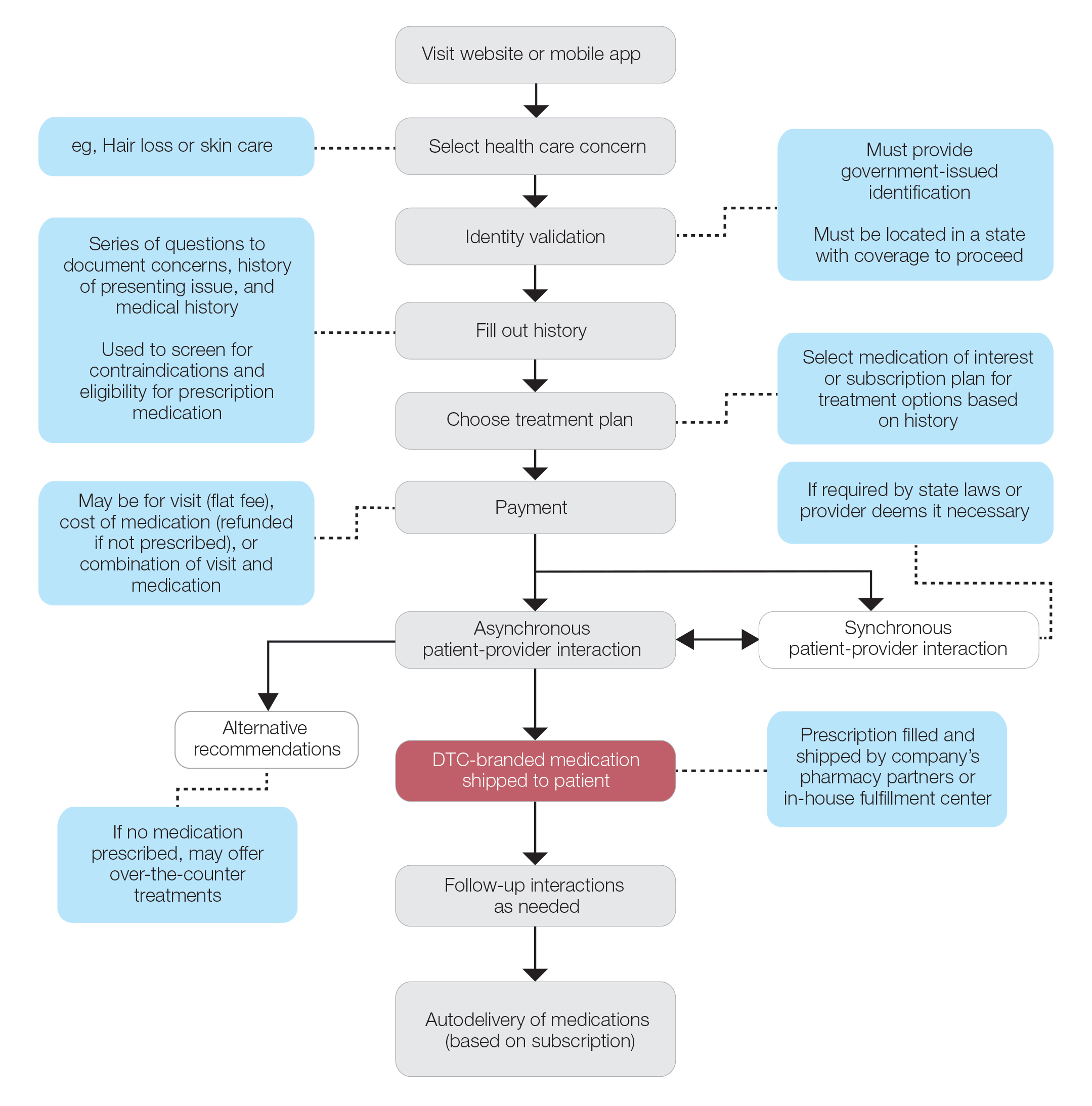

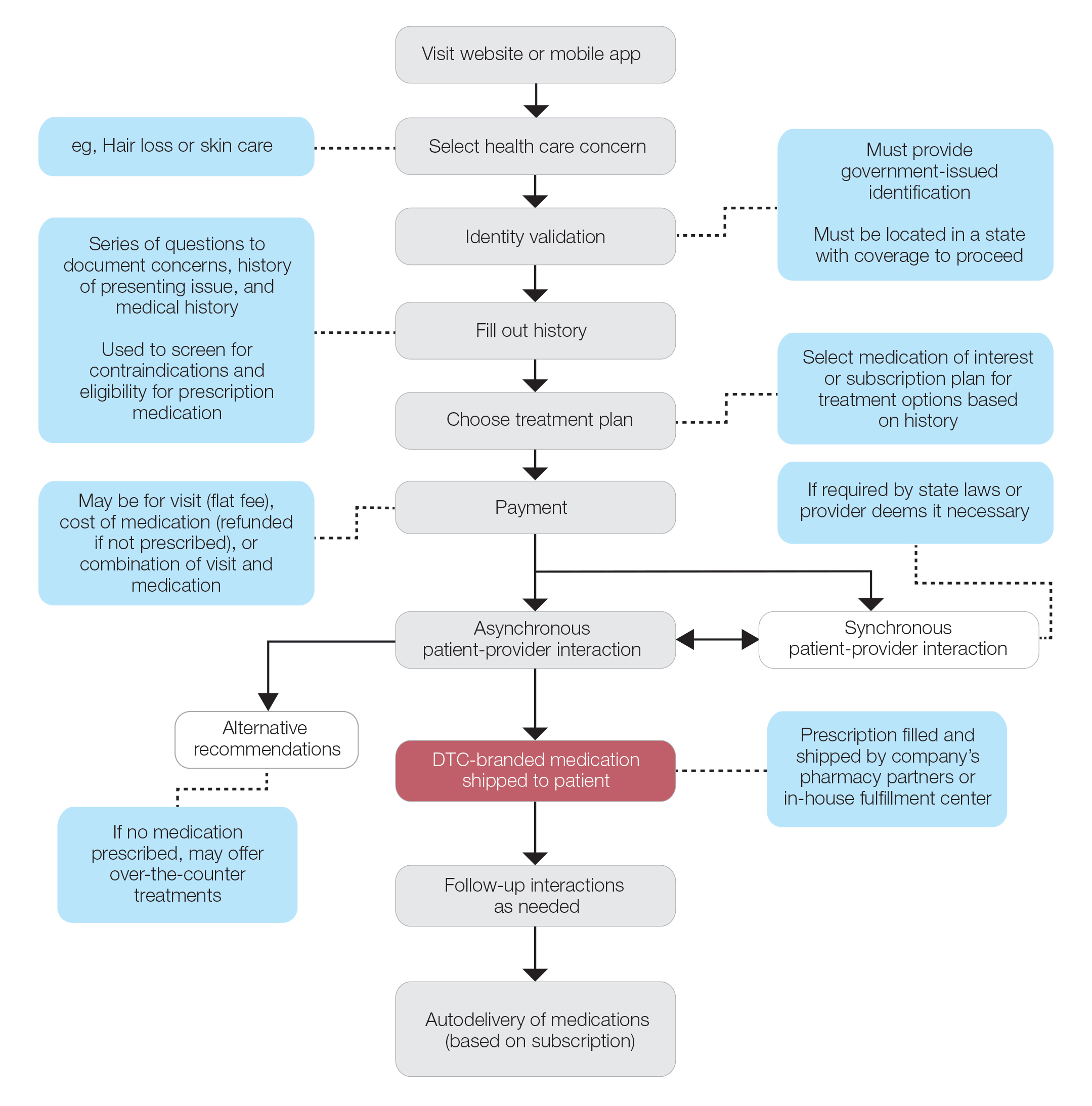

An important limitation of HPV testing is its inability to discriminate between transient and persistent infections. Referral of all HPV-positive cases to colposcopy would overburden the system with associated unnecessary procedures. Hence, a triage strategy is essential to identify clinically important infections that truly require colposcopic evaluation. The FIGURE illustrates the management of a primary HPV test result performed for screening.

HPV genotyping

One strategy for triaging a positive HPV test result is genotyping. HPV 16 and 18 have the highest risk of persistence and progression and merit immediate referral to colposcopy. In the ATHENA trial, CIN 3 was identified in 17.8% (95% CI, 14.8–20.7%) of HPV 16 positive women at baseline, and the CIR increased to 25.2% (95% CI, 21.7–28.7%) after 3 years. The 3-year CIR of CIN 3 was only 5.4% (95% CI, 4.5–6.3%) in women with HPV genotypes other than 16/18. HPV 18–positive women had a 3-year CIR that was intermediate between women with HPV 16 and women with the 12 other genotypes.6 Hence, HPV 16/18–positive cases should be referred for immediate colposcopy, and negative cases should be followed up with cytology and referred for colposcopy if the cytology is ASCUS or worse.31

In July 2020, extended genotyping was approved by the FDA with individual detection of HPV 31, 51, 52 (in addition to 16, 18, and 45) and pooled detection of 33/58, 35/39/68, and 56/59/66. One study found that individual genotypes HPV 16 and 31 carry baseline risk values for CIN 3+ (8.1% and 7.5%, respectively) that are above the 5-year risk threshold for referral to colposcopy following the ASCCP risk-based management guideline.32

Cytology

The higher specificity of cytology makes it an option for triaging HPV-positive cases, and current management guidelines recommend triage to both genotyping and cytology for all patients who are HPV positive, and especially if they are HPV positive but HPV 16/18 negative. Of note, cytology results remain more subjective than those of primary HPV testing, but the combination of initial HPV testing with reflex to cytology is a reasonable and cost effective next step.18 The VASCAR trial found higher colposcopy referrals in the HPV screening and cytology triage group compared with the cytology alone group (19.36 vs 14.54 per 1,000 women).33 The ATHENA trial investigated various triage strategies for HPV-positive cases and its impact on colposcopy referrals.6 Using HPV genotyping and reflex cytology, if HPV 16/18 was positive, colposcopy was advised, but if any of the other 12 HPV types were positive, reflex cytology was done. If reported as ASCUS or worse, colposcopy was performed; conversely, if it was normal, women were rescreened with cotesting after 1 year. Although this strategy led to a reduction in the number of colposcopies, referrals were still higher in the primary HPV arm (3,769 colposcopies per 294 cases) compared with cytology (1,934 colposcopies per 179 cases) or cotesting (3,097 colposcopies per 240 cases) in women aged 25 years.14

p16/Ki-67 Dual-Stain

Diffused p16 immunohistochemical staining, as opposed to focal staining, is associated with active HPV infection but can be present in low-grade as well as high-grade lesions.34 Ki-67 is a marker of cellular proliferation. Coexpression of p16 and Ki-67 indicates a loss of cell cycle regulation and is a hallmark of neoplastic transformation. When positive, these tests are supportive of active HPV infection and of a high-grade lesion. Incorporation of these stains to cytology alone provides additional objective reassurance to cytology, where there is much inter- and intra-observer variability. These stains can be done by laboratories using the stains alone or they can use the FDA-approved p16/Ki-67 Dual-Stain immunohistochemistry (DS), CINtec PLUS Cytology (Roche Diagnostics). However, DS is not yet formally incorporated into triage algorithms by national guidelines.

The IMPACT trial assessed the performance of DS compared with cytology in the triage of HPV-positive results, with or without HPV 16/18 genotyping.35 This was a prospective observational screening study of 35,263 women aged 25 to 65 years across 32 sites in the United States. Of the 4,927 HPV-positive patients with DS results, the sensitivity of DS for CIN 3+ was 91.9% (95% CI, 86.1%–95.4%) and 86.0% (95% CI, 77.5%–91.6%) in HPV 16/18–positive and in the 12 other genotypes, respectively. Using DS alone to triage HPV-positive results showed significantly higher sensitivity and specificity than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage of 12 “other” genotypes, and substantially higher sensitivity but lower specificity than using cytology alone. Of note, triage with DS alone would have referred significantly fewer women to colposcopy than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage for the 12 other genotypes (48.6% vs 56.0%; P< .0001).

Similarly, a retrospective analysis of the ATHENA trial cohort of HPV-positive results of 7,727 patients aged 25 years or older also demonstrated increased sensitivity of DS compared with cytology (74.9% vs 51.9%; P<.0001) and similar specificities (74.1% vs 75%; P = .3198).36 The European PALMS study, which included 27,349 women aged 18 years or older across 5 countries who underwent routine screening with HPV testing, cytology, and DS, confirmed these findings.37 The sensitivity of DS was higher than that of cytology (86.7% vs 68.5%; P<.001) for CIN 3+ with comparable specificities (95.2% vs 95.4%; P = .15).

Challenges and opportunities to improve access to primary HPV screening

The historical success of the Pap test in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer relied on individuals having access to the test. This remains true as screening transitions to primary HPV testing. Limitations of HPV-based screening include provider and patient knowledge; access to tests; cost; need for new laboratory infrastructure; need to leverage the electronic health record to record results, calculate a patient’s risk and determine next steps; and the need to re-educate patients and providers about this new model of care. The American Cancer Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are currently leading initiatives to help adopt primary HPV screening in the United States and to facilitate new care approaches.

Self-collection and independence from subjective cytology would further improve access. Multiple effectiveness studies and patient acceptability studies have shown that primary HPV screening via self-collection is effective, cost effective, and acceptable to women, especially among underscreened populations.38 Sensitivity is comparable to clinician-obtained samples with polymerase chain reaction–based HPV tests. Furthermore, newer molecular tests that detect methylated target host genes or methylated viral genome can be used to triage HPV-positive cases. Several host methylation markers that identify the specific host genes (for example, CADM1, MAL, and miR-124-2) have been shown to be more specific, reproducible, and can be used in self-collected samples as they are based on molecular methylation analysis.39 The ASCCP monitors these new developments and will incorporate promising tests and approaches once validated and FDA approved into the risk-based management guidelines. An erratum was recently published, and the risk-calculator is also available on the ASCCP website free of charge (https://app.asccp.org).40

In conclusion, transition to primary HPV testing from Pap cytology in cervical cancer screening has many challenges but also opportunities. Learning from the experience of countries that have already adopted primary HPV testing is crucial to successful implementation of this new screening paradigm.41 The evidence supporting primary HPV screening with its improved sensitivity is clear, and the existing triage options and innovations will continue to improve triage of patients with clinically important lesions as well as accessibility. With strong advocacy and sound implementation, the WHO goal of cervical cancer elimination and 70% of women being screened with a high-performance test by age 35 and again by age 45 is achievable. ●

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71: 209-249.

- Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095-1101.

- Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346-355.

- Tota JE, Bentley J, Blake J, et al. Introduction of molecular HPV testing as the primary technology in cervical cancer screening: acting on evidence to change the current paradigm. Prev Med. 2017;98:5-14.

- Ronco G, Giorgi Rossi P. Role of HPV DNA testing in modern gynaecological practice. Best Prac Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;47:107-118.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197.

- Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579-1588.

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- Bulkmans NW, Rozendaal L, Snijders PJ, et al. POBASCAM, a population-based randomized controlled trial for implementation of high-risk HPV testing in cervical screening: design, methods and baseline data of 44,102 women. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:94-101.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention. 2nd edition. Geneva: 2021. https://www .who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030824. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. American Cancer Society; 2020. https://www.cancer .org/cancer/cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging /cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines.html. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens KD, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Moscicki AB, Flowers L, Huchko MJ, et al. Guidelines for cervical cancer screening in immunosuppressed women without HIV infection. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2019;23:87-101.

- Committee opinion no. 675. Management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e178-e182.

- Satmary W, Holschneider CH, Brunette LL, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: risk factors for recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:126-131.

- Preti M, Scurry J, Marchitelli CE, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:10511062.

- Khan MJ, Massad LS, Kinney W, et al. A common clinical dilemma: management of abnormal vaginal cytology and human papillomavirus test results. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:364-370.

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2020;24:102-131.

- Egemen D, Cheung LC, Chen X, et al. Risk estimates supporting the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2020;24:132-143.

- Bhatla N, Singla S, Awasthi D. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid testing in developed countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:209-220.

- Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Castle PE, et al. Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:516-520.

- Ejegod D, Bottari F, Pedersen H, et al. The BD Onclarity HPV assay on samples collected in SurePath medium meets the international guidelines for human papillomavirus test requirements for cervical screening. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2267-2272.

- Richardson LA, Tota J, Franco EL. Optimizing technology for cervical cancer screening in high-resource settings. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;6:343-353.

- Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: followup of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754.

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

- Arbyn M, Ronco G, Anttila A, et al. Evidence regarding human papillomavirus testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine. 2012;30(suppl 5):F88-99.

- Schiffman M, Kinney WK, et al. Relative performance of HPV and cytology components of cotesting in cervical screening. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2018;110:501-508.

- Jin XW, Lipold L, Foucher J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of primary HPV testing, cytology and co-testing as cervical cancer screening for women above age 30 years. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1338-1344.

- Tota JE, Bentley J, Blake J, et al. Approaches for triaging women who test positive for human papillomavirus in cervical cancer screening. Prev Med. 2017;98:15-20.

- Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Parvu V, et al. Stratified risk of high-grade cervical disease using onclarity HPV extended genotyping in women, ≥25 years of age, with NILM cytology. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:26-33.

- Louvanto K, Chevarie-Davis M, Ramanakumar AV, et al. HPV testing with cytology triage for cervical cancer screening in routine practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:474.e1-7.

- Keating JT, Cviko A, Riethdorf S, et al. Ki-67, cyclin E, and p16INK4 are complimentary surrogate biomarkers for human papilloma virus-related cervical neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:884-891.

- Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Clinical validation of p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology triage of HPV-positive women: results from the IMPACT trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:461-471.

- Wright TC Jr, Behrens CM, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Triaging HPV-positive women with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results from a sub-study nested into the ATHENA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:51-56.

- Ikenberg H, Bergeron C, Schmidt D, et al. Screening for cervical cancer precursors with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results of the PALMS study. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2013;105:15501557.

- Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2018;363:k4823.

- Verhoef VMJ, Bosgraaf RP, van Kemenade FJ, et al. Triage by methylation-marker testing versus cytology in women who test HPV-positive on self-collected cervicovaginal specimens (PROHTECT-3): a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:315-322.

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. Erratum: 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2021;25:330-331.

- Hall MT, Simms KT, Lew JB, et al. The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in Australia: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e19-e27.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:178-182.

Cervical cancer is an important global health problem with an estimated 604,127 new cases and 341,831 deaths in 2020.1 Nearly 85% of the disease burden affects individuals from low and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) set forth the goal for all countries to reach and maintain an incidence rate of below 4 per 100,000 women by 2030 as part of the Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer.

Although traditional Pap cytology has been the cornerstone of screening programs, its poor sensitivity of approximately 50% and limitations in accessibility require new strategies to achieve the elimination of cervical cancer.2 The discovery that persistent infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) is an essential step in the development of cervical cancer led to the development of diagnostic HPV tests, which have higher sensitivity than cytology (96.1% vs 53.0%) but somewhat lower specificity (90.7% vs 96.3%) for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or worse lesions.2 Initially, HPV testing was incorporated as a method to triage atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) cytology results.3 Later, the concept of cotesting with cytology emerged,4,5 and since then, several clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of primary HPV screening.6-9

In 2020, the WHO recommended HPV DNA testing as the primary screening method starting at the age of 30 years, with regular testing every 5 to 10 years, for the general population.10 Currently, primary HPV has been adopted in multiple countries, including Australia, the Netherlands, Turkey, England, and Argentina.

In the United States, there are 3 currently acceptable screening strategies: cytology, cytology plus HPV (cotesting), and primary HPV testing (TABLE). The American Cancer Society (ACS) specifically states that HPV testing alone every 5 years is preferred starting at age 25 years; cotesting every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years are also acceptable.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that cytology alone every 3 years starting at 21 years and then HPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years or cytology every 3 years starting at age 30 are all acceptable strategies.12

When applying these guidelines, it is important to note that they are intended for the screening of patients with all prior normal results with no symptoms. These routine screening guidelines do not apply to special populations, such as those with a history of abnormal results or treatment, a history of immunosuppression,13 a history of HPV-related vulvar or vaginal dysplasia,14-16 or a history of hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no prior history of cervical dysplasia.17,18 By contrast, surveillance is interval testing for those who have either an abnormal prior test result or treatment; these may be managed per risk-based estimates provided by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP).18,19 Finally, diagnosis is evaluation (which may include diagnostic cytology) of a patient with abnormal signs and/or symptoms (such as bleeding, pain, discharge, or cervical mass).

In this Update, we present the evidence for primary HPV testing, the management options for a positive result in the United States, and research that will improve uptake of primary HPV testing as well as accessibility.

Change in screening paradigm: Evidence for primary HPV testing

HPV DNA tests are multiplex assays that detect the DNA of targeted high-risk HPV types, using multiple probes, either by direct genomic detection or by amplification of a viral DNA fragment using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).20,21 Alternatively, HPV mRNA-based tests detect the expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins, a marker of viral integration.20 In examining the data from well-conducted clinical trials, 2 important observations are that different HPV assays were used and that direct comparison may not be valid. In addition, not all tests used in the studies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary HPV testing.

Continue to: FDA-approved HPV tests...

FDA-approved HPV tests

Currently, 2 tests are FDA approved for primary HPV screening. The Cobas HPV test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) was the first FDA-approved test for primary HPV screening in women aged 25 years and older.6 This test reports pooled results from 12 high-risk (hr) HPV types (31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/66/68) with reflex genotyping for HPV 16/18, and thus it provides an immediate triage option for HPV-positive women. Of note, it is also approved for cotesting. The second FDA-approved test is the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company) for primary HPV screening.22 It detects 14 hrHPV types, types 16/18/45 specifically as well as types 31/33/35/39/51/52/56/58/59/66/68.

Other HPV tests are FDA approved for cotesting and reflex testing but not for primary HPV testing. The Hybrid Capture test, or HC2 (Qiagen Inc), was the first HPV test to be approved by the FDA in 1997 for reflex testing of women with ASCUS cytology. In 2003, it was approved for cotesting along with cytology in women aged 30 years and older.20,21 In 2009, the Cervista HPV HR test (Hologic Inc) was approved for cotesting. The Aptima HPV assay (Hologic Inc), which is also approved for cotesting, is an RNA-based assay that allows detection of E6/E7 mRNA transcripts of 14 HPV types.23

Comparing HPV testing with cytology

Ronco and colleagues pooled data from 4 European randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—Swedescreen, POBASCAM, NTCC, ARTISTIC—with a total of 176,464 participants randomly assigned to HPV or cytology screening.24 Swedescreen and POBASCAM used GP5/GP6 PCR, while ARTISTIC and NTCC used HC2 for primary HPV screening. The screening interval was 3 years in all except 5 years in POBASCAM. The pooled detection rate of invasive disease was similar in the 2 arms, with pooled rate ratio for cancer detection being 0.79 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46–1.36) in the first 2.5 years, but was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.25–0.81), favoring the HPV arm, after 2.5 years. HPV testing was more effective in preventing cases of adenocarcinoma than squamous cell carcinoma (0.31 [95% CI, 0.14–0.69] vs 0.78 [95% CI, 0.49–1.25]). The authors concluded that HPV-based screening from age 30 years provided 60% to 70% better protection than cytology.

The result of the above meta-analysis was confirmed by the HPV FOCAL RCT that investigated the efficacy of HPV testing (HC2) in comparison with cytology.25 The detection rates for CIN 3 lesions supported primary HPV screening, with an absolute difference in incidence rate of 2.67/1,000 (95% CI, 0.53–4.88) at study randomization and 3.22/1,000 (95% CI, 5.12–1.48) at study exit 4 years later.

Cotesting using HPV and cytology: Marginal benefit

Dillner and colleagues were one of the first groups to report on the risk of CIN 3 based on both HPV and cytology status.26 Using pooled analysis of data from multiple countries, these investigators reported that the cumulative incidence rates (CIR) of CIN 3 after 6 years of follow-up increased consistently in HPV-positive subjects, and an HPV-positive result more accurately predicted CIN 3+ at 5 years than cytology alone. Furthermore, HPV negativity provided greater reassurance than cytology alone. At 5 years of follow-up, the rates of CIN 3+ were 0.25% (0.12%–0.41%) for women negative for HPV compared with 0.83% (0.50%–1.13%) for women with negative cytology results. There was little difference in rates for CIN 3+ between women with negative results on both tests and women who were negative for HPV.

The important question is then the marginal benefit of cotesting, which is the most costly screening option. A study of 331,818 women enrolled for cotesting at Kaiser Permanente found that the risk of CIN 3+ predicted by HPV testing alone when compared with cytology was significantly higher at both 3 years (5.0% vs 3.8%; P = .046) and 5 years (7.6% vs 4.7%; P = .001).27 A negative cytology result did not decrease the risk of CIN 3 further for HPV-negative patients (3 years: 0.047% vs 0.063%, P = .6; 5 years: 0.16% vs 0.17%, P = .8). They concluded that a negative HPV test was enough reassurance for low risk of CIN 3+ and that an additional negative cytology result does not provide extra reassurance.

Furthermore, a systematic meta-analysis of 48 studies, including 8 RCTs, found that the addition of cytology to HPV testing raised the sensitivity by 2% for CIN 3 compared with HPV testing alone. This improvement in sensitivity was at the expense of considerable loss of specificity, with a ratio of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.92–0.95) for CIN 3.28 Schiffman and colleagues also assessed the relative contribution of HPV testing and cytology in detection of CIN 3 and cancer.29 The HPV component alone identified a significantly higher proportion of preinvasive and invasive disease than cytology. Only 3.5% of precancers and 5.9% of cancers were preceded by HPV-negative, cytology-positive results. Thus, cytology contributed only 5 cases per million women per year to the sensitivity of the combined test, at the cost of significantly more colposcopies. Hence, the evidence suggests that there is limited benefit of adding cytology to HPV testing.30

Continue to: Triage of a positive HPV result...

Triage of a positive HPV result

An important limitation of HPV testing is its inability to discriminate between transient and persistent infections. Referral of all HPV-positive cases to colposcopy would overburden the system with associated unnecessary procedures. Hence, a triage strategy is essential to identify clinically important infections that truly require colposcopic evaluation. The FIGURE illustrates the management of a primary HPV test result performed for screening.

HPV genotyping

One strategy for triaging a positive HPV test result is genotyping. HPV 16 and 18 have the highest risk of persistence and progression and merit immediate referral to colposcopy. In the ATHENA trial, CIN 3 was identified in 17.8% (95% CI, 14.8–20.7%) of HPV 16 positive women at baseline, and the CIR increased to 25.2% (95% CI, 21.7–28.7%) after 3 years. The 3-year CIR of CIN 3 was only 5.4% (95% CI, 4.5–6.3%) in women with HPV genotypes other than 16/18. HPV 18–positive women had a 3-year CIR that was intermediate between women with HPV 16 and women with the 12 other genotypes.6 Hence, HPV 16/18–positive cases should be referred for immediate colposcopy, and negative cases should be followed up with cytology and referred for colposcopy if the cytology is ASCUS or worse.31

In July 2020, extended genotyping was approved by the FDA with individual detection of HPV 31, 51, 52 (in addition to 16, 18, and 45) and pooled detection of 33/58, 35/39/68, and 56/59/66. One study found that individual genotypes HPV 16 and 31 carry baseline risk values for CIN 3+ (8.1% and 7.5%, respectively) that are above the 5-year risk threshold for referral to colposcopy following the ASCCP risk-based management guideline.32

Cytology

The higher specificity of cytology makes it an option for triaging HPV-positive cases, and current management guidelines recommend triage to both genotyping and cytology for all patients who are HPV positive, and especially if they are HPV positive but HPV 16/18 negative. Of note, cytology results remain more subjective than those of primary HPV testing, but the combination of initial HPV testing with reflex to cytology is a reasonable and cost effective next step.18 The VASCAR trial found higher colposcopy referrals in the HPV screening and cytology triage group compared with the cytology alone group (19.36 vs 14.54 per 1,000 women).33 The ATHENA trial investigated various triage strategies for HPV-positive cases and its impact on colposcopy referrals.6 Using HPV genotyping and reflex cytology, if HPV 16/18 was positive, colposcopy was advised, but if any of the other 12 HPV types were positive, reflex cytology was done. If reported as ASCUS or worse, colposcopy was performed; conversely, if it was normal, women were rescreened with cotesting after 1 year. Although this strategy led to a reduction in the number of colposcopies, referrals were still higher in the primary HPV arm (3,769 colposcopies per 294 cases) compared with cytology (1,934 colposcopies per 179 cases) or cotesting (3,097 colposcopies per 240 cases) in women aged 25 years.14

p16/Ki-67 Dual-Stain

Diffused p16 immunohistochemical staining, as opposed to focal staining, is associated with active HPV infection but can be present in low-grade as well as high-grade lesions.34 Ki-67 is a marker of cellular proliferation. Coexpression of p16 and Ki-67 indicates a loss of cell cycle regulation and is a hallmark of neoplastic transformation. When positive, these tests are supportive of active HPV infection and of a high-grade lesion. Incorporation of these stains to cytology alone provides additional objective reassurance to cytology, where there is much inter- and intra-observer variability. These stains can be done by laboratories using the stains alone or they can use the FDA-approved p16/Ki-67 Dual-Stain immunohistochemistry (DS), CINtec PLUS Cytology (Roche Diagnostics). However, DS is not yet formally incorporated into triage algorithms by national guidelines.

The IMPACT trial assessed the performance of DS compared with cytology in the triage of HPV-positive results, with or without HPV 16/18 genotyping.35 This was a prospective observational screening study of 35,263 women aged 25 to 65 years across 32 sites in the United States. Of the 4,927 HPV-positive patients with DS results, the sensitivity of DS for CIN 3+ was 91.9% (95% CI, 86.1%–95.4%) and 86.0% (95% CI, 77.5%–91.6%) in HPV 16/18–positive and in the 12 other genotypes, respectively. Using DS alone to triage HPV-positive results showed significantly higher sensitivity and specificity than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage of 12 “other” genotypes, and substantially higher sensitivity but lower specificity than using cytology alone. Of note, triage with DS alone would have referred significantly fewer women to colposcopy than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage for the 12 other genotypes (48.6% vs 56.0%; P< .0001).

Similarly, a retrospective analysis of the ATHENA trial cohort of HPV-positive results of 7,727 patients aged 25 years or older also demonstrated increased sensitivity of DS compared with cytology (74.9% vs 51.9%; P<.0001) and similar specificities (74.1% vs 75%; P = .3198).36 The European PALMS study, which included 27,349 women aged 18 years or older across 5 countries who underwent routine screening with HPV testing, cytology, and DS, confirmed these findings.37 The sensitivity of DS was higher than that of cytology (86.7% vs 68.5%; P<.001) for CIN 3+ with comparable specificities (95.2% vs 95.4%; P = .15).

Challenges and opportunities to improve access to primary HPV screening

The historical success of the Pap test in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer relied on individuals having access to the test. This remains true as screening transitions to primary HPV testing. Limitations of HPV-based screening include provider and patient knowledge; access to tests; cost; need for new laboratory infrastructure; need to leverage the electronic health record to record results, calculate a patient’s risk and determine next steps; and the need to re-educate patients and providers about this new model of care. The American Cancer Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are currently leading initiatives to help adopt primary HPV screening in the United States and to facilitate new care approaches.

Self-collection and independence from subjective cytology would further improve access. Multiple effectiveness studies and patient acceptability studies have shown that primary HPV screening via self-collection is effective, cost effective, and acceptable to women, especially among underscreened populations.38 Sensitivity is comparable to clinician-obtained samples with polymerase chain reaction–based HPV tests. Furthermore, newer molecular tests that detect methylated target host genes or methylated viral genome can be used to triage HPV-positive cases. Several host methylation markers that identify the specific host genes (for example, CADM1, MAL, and miR-124-2) have been shown to be more specific, reproducible, and can be used in self-collected samples as they are based on molecular methylation analysis.39 The ASCCP monitors these new developments and will incorporate promising tests and approaches once validated and FDA approved into the risk-based management guidelines. An erratum was recently published, and the risk-calculator is also available on the ASCCP website free of charge (https://app.asccp.org).40

In conclusion, transition to primary HPV testing from Pap cytology in cervical cancer screening has many challenges but also opportunities. Learning from the experience of countries that have already adopted primary HPV testing is crucial to successful implementation of this new screening paradigm.41 The evidence supporting primary HPV screening with its improved sensitivity is clear, and the existing triage options and innovations will continue to improve triage of patients with clinically important lesions as well as accessibility. With strong advocacy and sound implementation, the WHO goal of cervical cancer elimination and 70% of women being screened with a high-performance test by age 35 and again by age 45 is achievable. ●

Cervical cancer is an important global health problem with an estimated 604,127 new cases and 341,831 deaths in 2020.1 Nearly 85% of the disease burden affects individuals from low and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) set forth the goal for all countries to reach and maintain an incidence rate of below 4 per 100,000 women by 2030 as part of the Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer.

Although traditional Pap cytology has been the cornerstone of screening programs, its poor sensitivity of approximately 50% and limitations in accessibility require new strategies to achieve the elimination of cervical cancer.2 The discovery that persistent infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) is an essential step in the development of cervical cancer led to the development of diagnostic HPV tests, which have higher sensitivity than cytology (96.1% vs 53.0%) but somewhat lower specificity (90.7% vs 96.3%) for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or worse lesions.2 Initially, HPV testing was incorporated as a method to triage atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) cytology results.3 Later, the concept of cotesting with cytology emerged,4,5 and since then, several clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of primary HPV screening.6-9

In 2020, the WHO recommended HPV DNA testing as the primary screening method starting at the age of 30 years, with regular testing every 5 to 10 years, for the general population.10 Currently, primary HPV has been adopted in multiple countries, including Australia, the Netherlands, Turkey, England, and Argentina.

In the United States, there are 3 currently acceptable screening strategies: cytology, cytology plus HPV (cotesting), and primary HPV testing (TABLE). The American Cancer Society (ACS) specifically states that HPV testing alone every 5 years is preferred starting at age 25 years; cotesting every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years are also acceptable.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that cytology alone every 3 years starting at 21 years and then HPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years or cytology every 3 years starting at age 30 are all acceptable strategies.12

When applying these guidelines, it is important to note that they are intended for the screening of patients with all prior normal results with no symptoms. These routine screening guidelines do not apply to special populations, such as those with a history of abnormal results or treatment, a history of immunosuppression,13 a history of HPV-related vulvar or vaginal dysplasia,14-16 or a history of hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no prior history of cervical dysplasia.17,18 By contrast, surveillance is interval testing for those who have either an abnormal prior test result or treatment; these may be managed per risk-based estimates provided by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP).18,19 Finally, diagnosis is evaluation (which may include diagnostic cytology) of a patient with abnormal signs and/or symptoms (such as bleeding, pain, discharge, or cervical mass).

In this Update, we present the evidence for primary HPV testing, the management options for a positive result in the United States, and research that will improve uptake of primary HPV testing as well as accessibility.

Change in screening paradigm: Evidence for primary HPV testing

HPV DNA tests are multiplex assays that detect the DNA of targeted high-risk HPV types, using multiple probes, either by direct genomic detection or by amplification of a viral DNA fragment using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).20,21 Alternatively, HPV mRNA-based tests detect the expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins, a marker of viral integration.20 In examining the data from well-conducted clinical trials, 2 important observations are that different HPV assays were used and that direct comparison may not be valid. In addition, not all tests used in the studies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary HPV testing.

Continue to: FDA-approved HPV tests...

FDA-approved HPV tests

Currently, 2 tests are FDA approved for primary HPV screening. The Cobas HPV test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) was the first FDA-approved test for primary HPV screening in women aged 25 years and older.6 This test reports pooled results from 12 high-risk (hr) HPV types (31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/66/68) with reflex genotyping for HPV 16/18, and thus it provides an immediate triage option for HPV-positive women. Of note, it is also approved for cotesting. The second FDA-approved test is the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company) for primary HPV screening.22 It detects 14 hrHPV types, types 16/18/45 specifically as well as types 31/33/35/39/51/52/56/58/59/66/68.

Other HPV tests are FDA approved for cotesting and reflex testing but not for primary HPV testing. The Hybrid Capture test, or HC2 (Qiagen Inc), was the first HPV test to be approved by the FDA in 1997 for reflex testing of women with ASCUS cytology. In 2003, it was approved for cotesting along with cytology in women aged 30 years and older.20,21 In 2009, the Cervista HPV HR test (Hologic Inc) was approved for cotesting. The Aptima HPV assay (Hologic Inc), which is also approved for cotesting, is an RNA-based assay that allows detection of E6/E7 mRNA transcripts of 14 HPV types.23

Comparing HPV testing with cytology

Ronco and colleagues pooled data from 4 European randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—Swedescreen, POBASCAM, NTCC, ARTISTIC—with a total of 176,464 participants randomly assigned to HPV or cytology screening.24 Swedescreen and POBASCAM used GP5/GP6 PCR, while ARTISTIC and NTCC used HC2 for primary HPV screening. The screening interval was 3 years in all except 5 years in POBASCAM. The pooled detection rate of invasive disease was similar in the 2 arms, with pooled rate ratio for cancer detection being 0.79 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46–1.36) in the first 2.5 years, but was 0.45 (95% CI, 0.25–0.81), favoring the HPV arm, after 2.5 years. HPV testing was more effective in preventing cases of adenocarcinoma than squamous cell carcinoma (0.31 [95% CI, 0.14–0.69] vs 0.78 [95% CI, 0.49–1.25]). The authors concluded that HPV-based screening from age 30 years provided 60% to 70% better protection than cytology.

The result of the above meta-analysis was confirmed by the HPV FOCAL RCT that investigated the efficacy of HPV testing (HC2) in comparison with cytology.25 The detection rates for CIN 3 lesions supported primary HPV screening, with an absolute difference in incidence rate of 2.67/1,000 (95% CI, 0.53–4.88) at study randomization and 3.22/1,000 (95% CI, 5.12–1.48) at study exit 4 years later.

Cotesting using HPV and cytology: Marginal benefit

Dillner and colleagues were one of the first groups to report on the risk of CIN 3 based on both HPV and cytology status.26 Using pooled analysis of data from multiple countries, these investigators reported that the cumulative incidence rates (CIR) of CIN 3 after 6 years of follow-up increased consistently in HPV-positive subjects, and an HPV-positive result more accurately predicted CIN 3+ at 5 years than cytology alone. Furthermore, HPV negativity provided greater reassurance than cytology alone. At 5 years of follow-up, the rates of CIN 3+ were 0.25% (0.12%–0.41%) for women negative for HPV compared with 0.83% (0.50%–1.13%) for women with negative cytology results. There was little difference in rates for CIN 3+ between women with negative results on both tests and women who were negative for HPV.

The important question is then the marginal benefit of cotesting, which is the most costly screening option. A study of 331,818 women enrolled for cotesting at Kaiser Permanente found that the risk of CIN 3+ predicted by HPV testing alone when compared with cytology was significantly higher at both 3 years (5.0% vs 3.8%; P = .046) and 5 years (7.6% vs 4.7%; P = .001).27 A negative cytology result did not decrease the risk of CIN 3 further for HPV-negative patients (3 years: 0.047% vs 0.063%, P = .6; 5 years: 0.16% vs 0.17%, P = .8). They concluded that a negative HPV test was enough reassurance for low risk of CIN 3+ and that an additional negative cytology result does not provide extra reassurance.

Furthermore, a systematic meta-analysis of 48 studies, including 8 RCTs, found that the addition of cytology to HPV testing raised the sensitivity by 2% for CIN 3 compared with HPV testing alone. This improvement in sensitivity was at the expense of considerable loss of specificity, with a ratio of 0.93 (95% CI, 0.92–0.95) for CIN 3.28 Schiffman and colleagues also assessed the relative contribution of HPV testing and cytology in detection of CIN 3 and cancer.29 The HPV component alone identified a significantly higher proportion of preinvasive and invasive disease than cytology. Only 3.5% of precancers and 5.9% of cancers were preceded by HPV-negative, cytology-positive results. Thus, cytology contributed only 5 cases per million women per year to the sensitivity of the combined test, at the cost of significantly more colposcopies. Hence, the evidence suggests that there is limited benefit of adding cytology to HPV testing.30

Continue to: Triage of a positive HPV result...

Triage of a positive HPV result

An important limitation of HPV testing is its inability to discriminate between transient and persistent infections. Referral of all HPV-positive cases to colposcopy would overburden the system with associated unnecessary procedures. Hence, a triage strategy is essential to identify clinically important infections that truly require colposcopic evaluation. The FIGURE illustrates the management of a primary HPV test result performed for screening.

HPV genotyping

One strategy for triaging a positive HPV test result is genotyping. HPV 16 and 18 have the highest risk of persistence and progression and merit immediate referral to colposcopy. In the ATHENA trial, CIN 3 was identified in 17.8% (95% CI, 14.8–20.7%) of HPV 16 positive women at baseline, and the CIR increased to 25.2% (95% CI, 21.7–28.7%) after 3 years. The 3-year CIR of CIN 3 was only 5.4% (95% CI, 4.5–6.3%) in women with HPV genotypes other than 16/18. HPV 18–positive women had a 3-year CIR that was intermediate between women with HPV 16 and women with the 12 other genotypes.6 Hence, HPV 16/18–positive cases should be referred for immediate colposcopy, and negative cases should be followed up with cytology and referred for colposcopy if the cytology is ASCUS or worse.31

In July 2020, extended genotyping was approved by the FDA with individual detection of HPV 31, 51, 52 (in addition to 16, 18, and 45) and pooled detection of 33/58, 35/39/68, and 56/59/66. One study found that individual genotypes HPV 16 and 31 carry baseline risk values for CIN 3+ (8.1% and 7.5%, respectively) that are above the 5-year risk threshold for referral to colposcopy following the ASCCP risk-based management guideline.32

Cytology

The higher specificity of cytology makes it an option for triaging HPV-positive cases, and current management guidelines recommend triage to both genotyping and cytology for all patients who are HPV positive, and especially if they are HPV positive but HPV 16/18 negative. Of note, cytology results remain more subjective than those of primary HPV testing, but the combination of initial HPV testing with reflex to cytology is a reasonable and cost effective next step.18 The VASCAR trial found higher colposcopy referrals in the HPV screening and cytology triage group compared with the cytology alone group (19.36 vs 14.54 per 1,000 women).33 The ATHENA trial investigated various triage strategies for HPV-positive cases and its impact on colposcopy referrals.6 Using HPV genotyping and reflex cytology, if HPV 16/18 was positive, colposcopy was advised, but if any of the other 12 HPV types were positive, reflex cytology was done. If reported as ASCUS or worse, colposcopy was performed; conversely, if it was normal, women were rescreened with cotesting after 1 year. Although this strategy led to a reduction in the number of colposcopies, referrals were still higher in the primary HPV arm (3,769 colposcopies per 294 cases) compared with cytology (1,934 colposcopies per 179 cases) or cotesting (3,097 colposcopies per 240 cases) in women aged 25 years.14

p16/Ki-67 Dual-Stain

Diffused p16 immunohistochemical staining, as opposed to focal staining, is associated with active HPV infection but can be present in low-grade as well as high-grade lesions.34 Ki-67 is a marker of cellular proliferation. Coexpression of p16 and Ki-67 indicates a loss of cell cycle regulation and is a hallmark of neoplastic transformation. When positive, these tests are supportive of active HPV infection and of a high-grade lesion. Incorporation of these stains to cytology alone provides additional objective reassurance to cytology, where there is much inter- and intra-observer variability. These stains can be done by laboratories using the stains alone or they can use the FDA-approved p16/Ki-67 Dual-Stain immunohistochemistry (DS), CINtec PLUS Cytology (Roche Diagnostics). However, DS is not yet formally incorporated into triage algorithms by national guidelines.

The IMPACT trial assessed the performance of DS compared with cytology in the triage of HPV-positive results, with or without HPV 16/18 genotyping.35 This was a prospective observational screening study of 35,263 women aged 25 to 65 years across 32 sites in the United States. Of the 4,927 HPV-positive patients with DS results, the sensitivity of DS for CIN 3+ was 91.9% (95% CI, 86.1%–95.4%) and 86.0% (95% CI, 77.5%–91.6%) in HPV 16/18–positive and in the 12 other genotypes, respectively. Using DS alone to triage HPV-positive results showed significantly higher sensitivity and specificity than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage of 12 “other” genotypes, and substantially higher sensitivity but lower specificity than using cytology alone. Of note, triage with DS alone would have referred significantly fewer women to colposcopy than HPV 16/18 genotyping with cytology triage for the 12 other genotypes (48.6% vs 56.0%; P< .0001).

Similarly, a retrospective analysis of the ATHENA trial cohort of HPV-positive results of 7,727 patients aged 25 years or older also demonstrated increased sensitivity of DS compared with cytology (74.9% vs 51.9%; P<.0001) and similar specificities (74.1% vs 75%; P = .3198).36 The European PALMS study, which included 27,349 women aged 18 years or older across 5 countries who underwent routine screening with HPV testing, cytology, and DS, confirmed these findings.37 The sensitivity of DS was higher than that of cytology (86.7% vs 68.5%; P<.001) for CIN 3+ with comparable specificities (95.2% vs 95.4%; P = .15).

Challenges and opportunities to improve access to primary HPV screening

The historical success of the Pap test in reducing the incidence of cervical cancer relied on individuals having access to the test. This remains true as screening transitions to primary HPV testing. Limitations of HPV-based screening include provider and patient knowledge; access to tests; cost; need for new laboratory infrastructure; need to leverage the electronic health record to record results, calculate a patient’s risk and determine next steps; and the need to re-educate patients and providers about this new model of care. The American Cancer Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are currently leading initiatives to help adopt primary HPV screening in the United States and to facilitate new care approaches.

Self-collection and independence from subjective cytology would further improve access. Multiple effectiveness studies and patient acceptability studies have shown that primary HPV screening via self-collection is effective, cost effective, and acceptable to women, especially among underscreened populations.38 Sensitivity is comparable to clinician-obtained samples with polymerase chain reaction–based HPV tests. Furthermore, newer molecular tests that detect methylated target host genes or methylated viral genome can be used to triage HPV-positive cases. Several host methylation markers that identify the specific host genes (for example, CADM1, MAL, and miR-124-2) have been shown to be more specific, reproducible, and can be used in self-collected samples as they are based on molecular methylation analysis.39 The ASCCP monitors these new developments and will incorporate promising tests and approaches once validated and FDA approved into the risk-based management guidelines. An erratum was recently published, and the risk-calculator is also available on the ASCCP website free of charge (https://app.asccp.org).40

In conclusion, transition to primary HPV testing from Pap cytology in cervical cancer screening has many challenges but also opportunities. Learning from the experience of countries that have already adopted primary HPV testing is crucial to successful implementation of this new screening paradigm.41 The evidence supporting primary HPV screening with its improved sensitivity is clear, and the existing triage options and innovations will continue to improve triage of patients with clinically important lesions as well as accessibility. With strong advocacy and sound implementation, the WHO goal of cervical cancer elimination and 70% of women being screened with a high-performance test by age 35 and again by age 45 is achievable. ●

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71: 209-249.

- Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095-1101.

- Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346-355.

- Tota JE, Bentley J, Blake J, et al. Introduction of molecular HPV testing as the primary technology in cervical cancer screening: acting on evidence to change the current paradigm. Prev Med. 2017;98:5-14.

- Ronco G, Giorgi Rossi P. Role of HPV DNA testing in modern gynaecological practice. Best Prac Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;47:107-118.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197.

- Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579-1588.

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- Bulkmans NW, Rozendaal L, Snijders PJ, et al. POBASCAM, a population-based randomized controlled trial for implementation of high-risk HPV testing in cervical screening: design, methods and baseline data of 44,102 women. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:94-101.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention. 2nd edition. Geneva: 2021. https://www .who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030824. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. American Cancer Society; 2020. https://www.cancer .org/cancer/cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging /cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines.html. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens KD, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Moscicki AB, Flowers L, Huchko MJ, et al. Guidelines for cervical cancer screening in immunosuppressed women without HIV infection. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2019;23:87-101.

- Committee opinion no. 675. Management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e178-e182.

- Satmary W, Holschneider CH, Brunette LL, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: risk factors for recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:126-131.

- Preti M, Scurry J, Marchitelli CE, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:10511062.

- Khan MJ, Massad LS, Kinney W, et al. A common clinical dilemma: management of abnormal vaginal cytology and human papillomavirus test results. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:364-370.

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2020;24:102-131.

- Egemen D, Cheung LC, Chen X, et al. Risk estimates supporting the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2020;24:132-143.

- Bhatla N, Singla S, Awasthi D. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid testing in developed countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:209-220.

- Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Castle PE, et al. Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:516-520.

- Ejegod D, Bottari F, Pedersen H, et al. The BD Onclarity HPV assay on samples collected in SurePath medium meets the international guidelines for human papillomavirus test requirements for cervical screening. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2267-2272.

- Richardson LA, Tota J, Franco EL. Optimizing technology for cervical cancer screening in high-resource settings. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;6:343-353.

- Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: followup of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754.

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

- Arbyn M, Ronco G, Anttila A, et al. Evidence regarding human papillomavirus testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine. 2012;30(suppl 5):F88-99.

- Schiffman M, Kinney WK, et al. Relative performance of HPV and cytology components of cotesting in cervical screening. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2018;110:501-508.

- Jin XW, Lipold L, Foucher J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of primary HPV testing, cytology and co-testing as cervical cancer screening for women above age 30 years. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1338-1344.

- Tota JE, Bentley J, Blake J, et al. Approaches for triaging women who test positive for human papillomavirus in cervical cancer screening. Prev Med. 2017;98:15-20.

- Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Parvu V, et al. Stratified risk of high-grade cervical disease using onclarity HPV extended genotyping in women, ≥25 years of age, with NILM cytology. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:26-33.

- Louvanto K, Chevarie-Davis M, Ramanakumar AV, et al. HPV testing with cytology triage for cervical cancer screening in routine practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:474.e1-7.

- Keating JT, Cviko A, Riethdorf S, et al. Ki-67, cyclin E, and p16INK4 are complimentary surrogate biomarkers for human papilloma virus-related cervical neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:884-891.

- Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Clinical validation of p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology triage of HPV-positive women: results from the IMPACT trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:461-471.

- Wright TC Jr, Behrens CM, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Triaging HPV-positive women with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results from a sub-study nested into the ATHENA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:51-56.

- Ikenberg H, Bergeron C, Schmidt D, et al. Screening for cervical cancer precursors with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results of the PALMS study. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2013;105:15501557.

- Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2018;363:k4823.

- Verhoef VMJ, Bosgraaf RP, van Kemenade FJ, et al. Triage by methylation-marker testing versus cytology in women who test HPV-positive on self-collected cervicovaginal specimens (PROHTECT-3): a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:315-322.

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. Erratum: 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2021;25:330-331.

- Hall MT, Simms KT, Lew JB, et al. The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in Australia: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e19-e27.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:178-182.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71: 209-249.

- Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095-1101.

- Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346-355.

- Tota JE, Bentley J, Blake J, et al. Introduction of molecular HPV testing as the primary technology in cervical cancer screening: acting on evidence to change the current paradigm. Prev Med. 2017;98:5-14.

- Ronco G, Giorgi Rossi P. Role of HPV DNA testing in modern gynaecological practice. Best Prac Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;47:107-118.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197.

- Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579-1588.

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- Bulkmans NW, Rozendaal L, Snijders PJ, et al. POBASCAM, a population-based randomized controlled trial for implementation of high-risk HPV testing in cervical screening: design, methods and baseline data of 44,102 women. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:94-101.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention. 2nd edition. Geneva: 2021. https://www .who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030824. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. American Cancer Society; 2020. https://www.cancer .org/cancer/cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging /cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines.html. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens KD, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Moscicki AB, Flowers L, Huchko MJ, et al. Guidelines for cervical cancer screening in immunosuppressed women without HIV infection. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2019;23:87-101.

- Committee opinion no. 675. Management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e178-e182.

- Satmary W, Holschneider CH, Brunette LL, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: risk factors for recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:126-131.

- Preti M, Scurry J, Marchitelli CE, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:10511062.

- Khan MJ, Massad LS, Kinney W, et al. A common clinical dilemma: management of abnormal vaginal cytology and human papillomavirus test results. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:364-370.

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2020;24:102-131.

- Egemen D, Cheung LC, Chen X, et al. Risk estimates supporting the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2020;24:132-143.

- Bhatla N, Singla S, Awasthi D. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid testing in developed countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:209-220.

- Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Castle PE, et al. Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:516-520.

- Ejegod D, Bottari F, Pedersen H, et al. The BD Onclarity HPV assay on samples collected in SurePath medium meets the international guidelines for human papillomavirus test requirements for cervical screening. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2267-2272.

- Richardson LA, Tota J, Franco EL. Optimizing technology for cervical cancer screening in high-resource settings. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;6:343-353.

- Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: followup of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754.

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

- Arbyn M, Ronco G, Anttila A, et al. Evidence regarding human papillomavirus testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine. 2012;30(suppl 5):F88-99.

- Schiffman M, Kinney WK, et al. Relative performance of HPV and cytology components of cotesting in cervical screening. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2018;110:501-508.

- Jin XW, Lipold L, Foucher J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of primary HPV testing, cytology and co-testing as cervical cancer screening for women above age 30 years. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1338-1344.

- Tota JE, Bentley J, Blake J, et al. Approaches for triaging women who test positive for human papillomavirus in cervical cancer screening. Prev Med. 2017;98:15-20.

- Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Parvu V, et al. Stratified risk of high-grade cervical disease using onclarity HPV extended genotyping in women, ≥25 years of age, with NILM cytology. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:26-33.

- Louvanto K, Chevarie-Davis M, Ramanakumar AV, et al. HPV testing with cytology triage for cervical cancer screening in routine practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:474.e1-7.

- Keating JT, Cviko A, Riethdorf S, et al. Ki-67, cyclin E, and p16INK4 are complimentary surrogate biomarkers for human papilloma virus-related cervical neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:884-891.

- Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Clinical validation of p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology triage of HPV-positive women: results from the IMPACT trial. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:461-471.

- Wright TC Jr, Behrens CM, Ranger-Moore J, et al. Triaging HPV-positive women with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results from a sub-study nested into the ATHENA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:51-56.

- Ikenberg H, Bergeron C, Schmidt D, et al. Screening for cervical cancer precursors with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results of the PALMS study. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2013;105:15501557.

- Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2018;363:k4823.

- Verhoef VMJ, Bosgraaf RP, van Kemenade FJ, et al. Triage by methylation-marker testing versus cytology in women who test HPV-positive on self-collected cervicovaginal specimens (PROHTECT-3): a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:315-322.

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. Erratum: 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2021;25:330-331.

- Hall MT, Simms KT, Lew JB, et al. The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in Australia: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e19-e27.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:178-182.

Cervical cancer: A path to eradication

David G. Mutch, MD: The cervical cancer screening guidelines, using Pap testing, have changed significantly since the times of yearly Paps and exams. Coupled with vaccination and new management guidelines (recommending HPV testing, etc), we actually hope that we are on the way to eradicating cervical cancer from our environment.

Screening: Current recommendations

Dr. Mutch: Warner, the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)1 endorses the cervical cancer screening guidelines for several professional organizations, including the American Cancer Society (ACS),2 the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),3 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).4 What are the current screening recommendations, as these organizations have disparate views?

Warner Huh, MD: There was a time, around 2012-2013, when for the first time ever, we had significant harmonization of the guidelines between ACOG and the USPSTF and ACS. But in the last 10 years there has been an explosion of data in terms of how to best screen patients.