User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Treatment augmentation strategies for OCD: A review of 8 studies

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic, debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder that affects 1% to 3% of the population worldwide.1,2 Together, serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) and cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) are considered the first-line treatment for OCD.3 In children and adults, CBT is considered at least as effective as pharmacotherapy.4 Despite being an effective treatment, CBT continues to have barriers to its widespread use, including limited availability of trained CBT therapists, delayed clinical response, and high costs.5

Only approximately one-half of patients with OCD respond to SRI therapy, and a considerable percentage (30% to 40%) show significant residual symptoms even after multiple trials of SRIs.6-8 In addition, SRIs may have adverse effects (eg, sexual dysfunction, gastrointestinal symptoms) that impair patient adherence to these medications.9 Therefore, finding better treatment options is important for managing patients with OCD.

Augmentation strategies are recommended for patients who show partial response to SRI treatment or poor response to multiple SRIs. Augmentation typically includes incorporating additional medications with the primary drug with the goal of boosting the therapeutic efficacy of the primary drug. Typically, these additional medications have different mechanisms of action. However, there are no large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to inform treatment augmentation after first-line treatments for OCD produce suboptimal outcomes. The available evidence is predominantly based on small-scale RCTs, open-label trials, and case series.

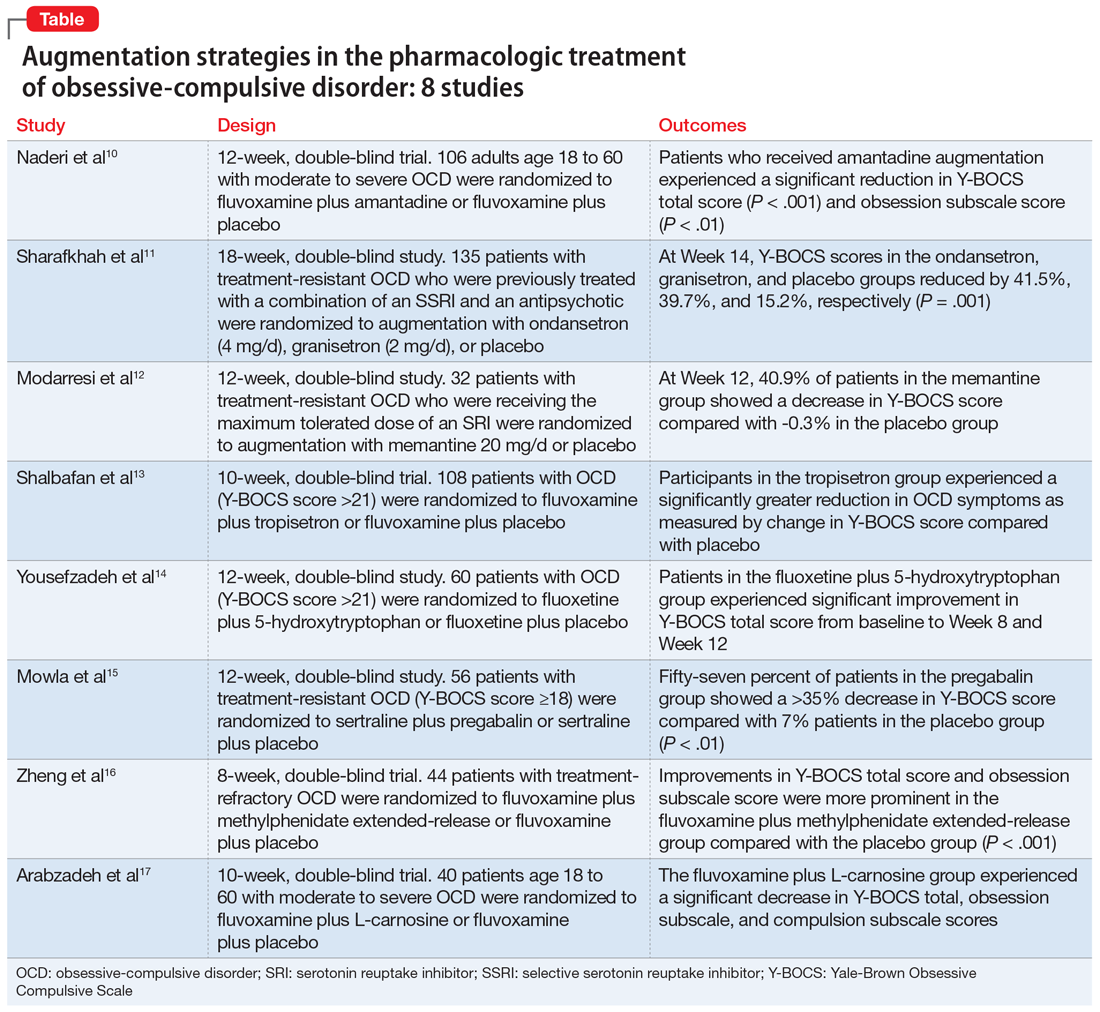

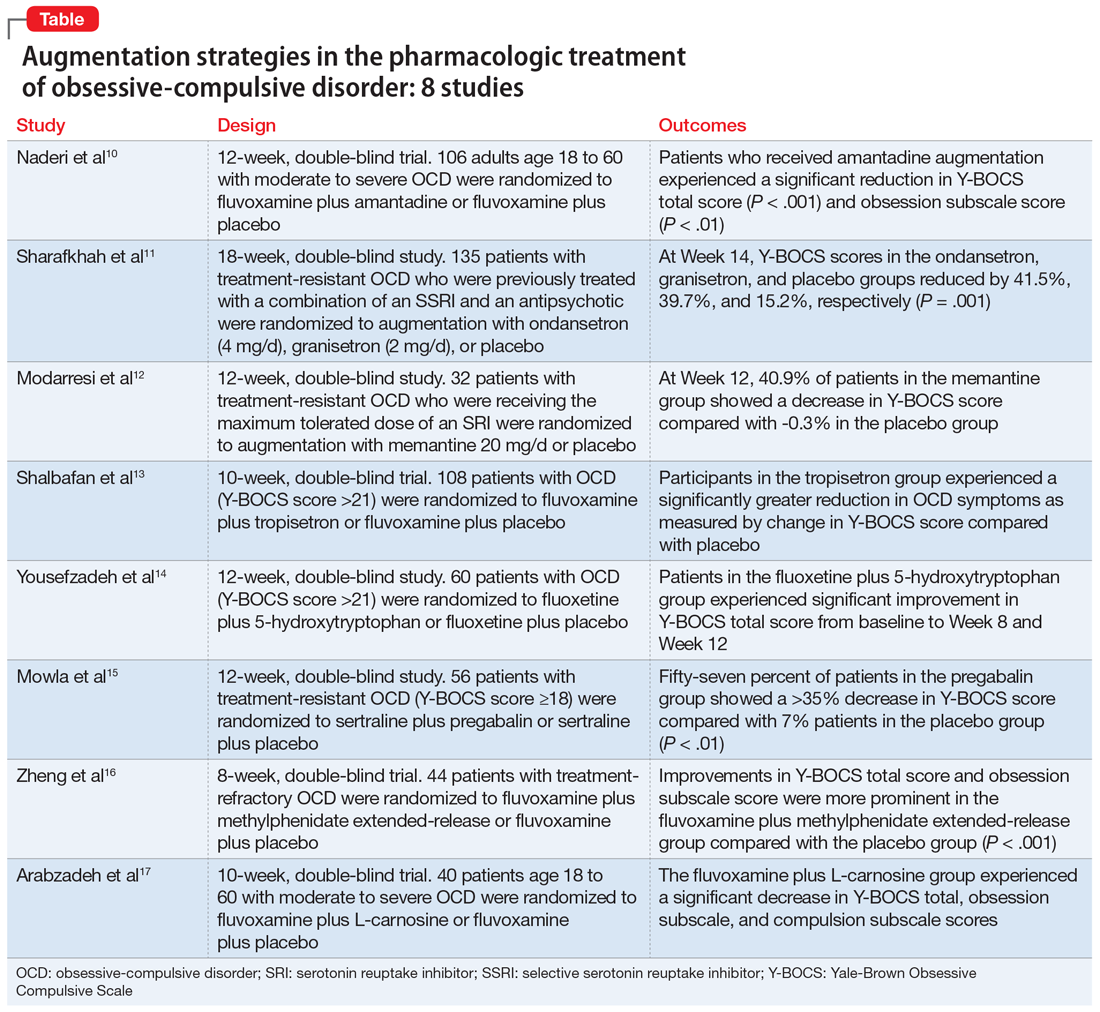

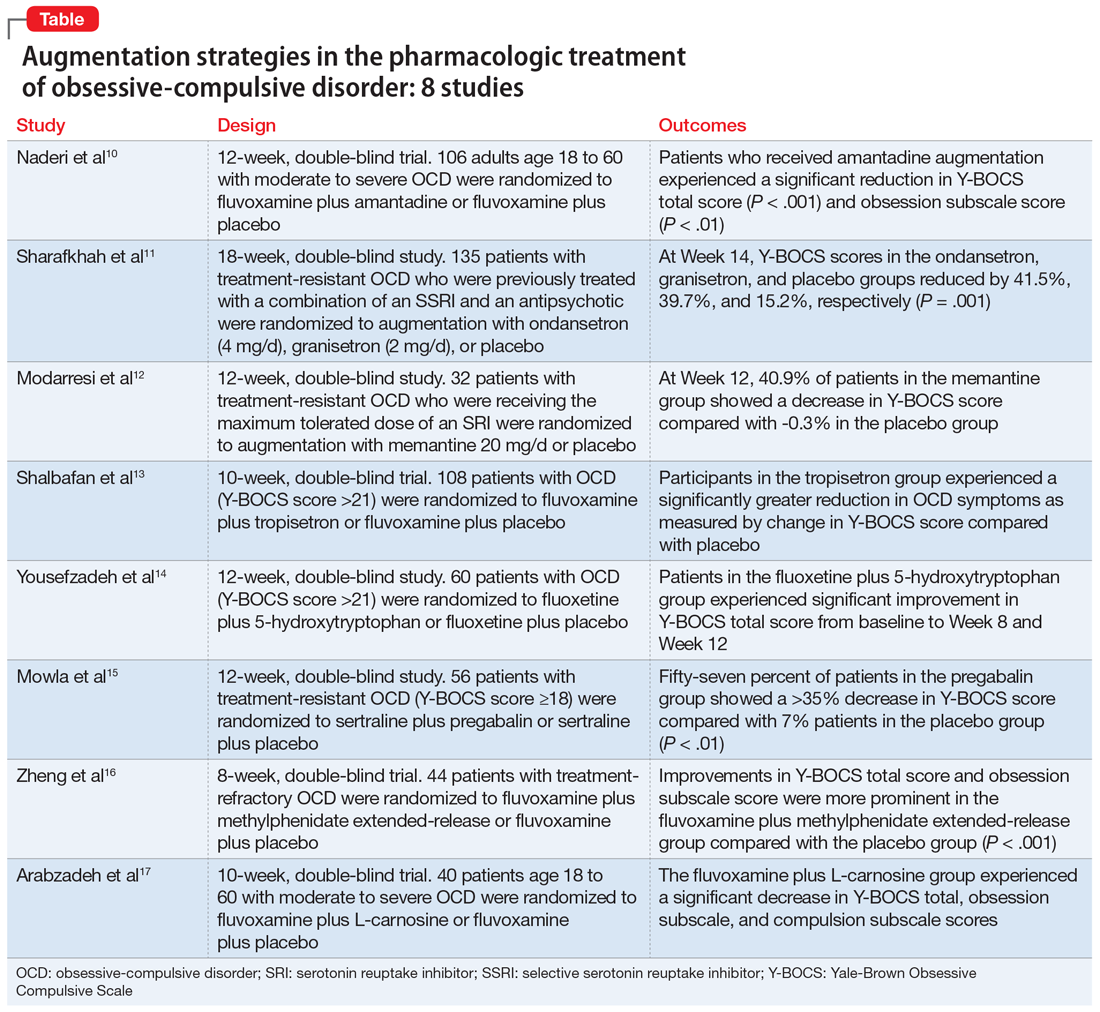

In this article, we review the evidence for treatment augmentation strategies for OCD and summarize 8 studies that show promising results (Table10-17). We focus only on pharmacologic agents and do not include other biological interventions, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area, ablative neurosurgery, or deep brain stimulation.

Continue to: Reference 1...

1. Naderi S, Faghih H , Aqamolaei A, et al. Amantadine as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe obsessivecompulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(4):169-174. doi:10.1111/ pcn.12803

Numerous studies support the role of glutamate dysregulation in the pathophysiology of OCD. Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) abnormalities play a major role in the pathophysiology of OCD as suggested by neuroimaging research studies that indicate glutamate is the fundamental neurotransmitter of the CSTC circuit. Dysregulation of glutamatergic signaling within this circuit has been linked to OCD. Patients with OCD have been found to have an increase of glutamate in the CSF. As a result, medications that affect glutamate levels can be used to treat patients with OCD who do not respond to first-line agents. In patients already taking SRIs, augmentation of glutamate-modulating medications can reduce OCD symptoms. As an uncompetitive antagonist of the N-methyl-

Naderi et al10 evaluated amantadine as augmentative therapy to fluvoxamine for treating patients with moderate to severe OCD.

Study design

- This 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of amantadine as an augmentative agent to fluvoxamine in 106 patients age 18 to 60 with moderate to severe OCD.

- Participants met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had a Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score >21. Participants were excluded if they had any substance dependence; an IQ <70; any other Axis I mental disorder; any serious cardiac, renal, or hepatic disease; had received psychotropic medications during the last 6 weeks, were pregnant or breastfeeding, or had rising liver transaminases to 3 times the upper limit of normal or higher.

- Participants received fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily plus amantadine 100 mg/d, or fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily plus placebo. All patients received fluvoxamine 100 mg/d for 28 days followed by 200 mg/d for the remainder of the trial.

- The primary outcome measure was difference in Y-BOCS total scores between the amantadine and placebo groups. The secondary outcome was the difference in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores.

Outcomes

- Patients who received amantadine augmentation experienced a significant reduction in Y-BOCS total score (P < .001) and obsession subscale score (P < .01).

- The amantadine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

- Amantadine is an effective adjuvant to fluvoxamine for reducing OCD symptoms.

Conclusion

- Ondansetron and granisetron can be beneficial as an augmentation strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

2. Sharafkhah M, Aghakarim Alamdar M, Massoudifar A, et al. Comparing the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(5):222- 233. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000267

Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered a first-line treatment when teamed with CBT and antipsychotic augmentation, symptom resolution is not always achieved, and treatment resistance is a common problem. Sharafkhah et al11 compared the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation specifically for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

Study Design

- In this 18-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 135 patients with treatment-resistant OCD who were previously treated with a combination of an SSRI and an antipsychotic received augmentation with ondansetron (n = 45, 4 mg/d), granisetron (n = 45, 2 mg/d), or placebo.

- Patients were rated using Y-BOCS every 2 weeks during phase I (intervention period), which lasted 14 weeks. After completing the intervention, patients were followed for 4 more weeks during phase II (discontinuation period).

- The aim of this study was to determine the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of ondansetron vs granisetron as augmentation for patients with treatment-resistant OCD. A secondary aim was to determine the rate of relapse of OCD symptoms after discontinuing ondansetron as compared with granisetron at 4 weeks after intervention.

Outcomes

- At Week 14, the reductions in Y-BOCS scores in the ondansetron, granisetron, and placebo groups were 41.5%, 39.7%, and 15.2%, respectively (P = .001). The reduction in Y-BOCS score in the ondansetron and granisetron groups was significantly greater than placebo at all phase I visits.

- Complete response was higher in the ondansetron group compared with the granisetron group (P = .041).

- Y-BOCS scores increased in both the ondansetron and granisetron groups during the discontinuation phase, but OCD symptoms were not significantly exacerbated.

Conclusion

- Ondansetron and granisetron can be beneficial as an augmentation strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

3. Modarresi A, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitorrefractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(6):263-269. doi:10.1055/s-0043-120268

Increased glutamate levels in CSF, glutamatergic overactivity, and polymorphisms of genes coding the NMDA receptor have been shown to contribute to the occurrence of OCD. Memantine is a noncompetitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor. Various control trials have shown augmentation with memantine 5 mg/d to 20 mg/d significantly reduced symptom severity in patients with moderate to severe OCD. Modarresi et al12 evaluated memantine as a treatment option for patients with severe OCD who did not respond to SRI monotherapy.

Study design

- This 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of memantine augmentation in 32 patients age 18 to 40 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD, had a Y-BOCS score ≥24, and no psychiatric comorbidity. Participants had not responded to ≥3 adequate trials (minimum 3 months) of SRI therapy, 1 of which was clomipramine.

- Individuals were excluded if they were undergoing CBT; had an additional anxiety disorder, mood disorder, or current drug or alcohol use disorder, or any systemic disorder; had a history of seizures; were pregnant or breastfeeding; or had a history of memantine use.

- Participants already receiving the maximum tolerated dose of an SRI received augmentation with memantine 20 mg/d or placebo.

- The primary outcome measure was change in Y-BOCS score from baseline. The secondary outcome was the number of individuals who achieved treatment response (defined as ≥35% reduction in Y-BOCS score).

Continue to: Outcomes...

Outcomes

- There was a statistically significant difference in Y-BOCS score in patients treated with memantine at Week 8 and Week 12 vs those who received placebo. By Week 8, 17.2% of patients in the memantine group showed a decrease in Y-BOCS score, compared with -0.8% patients in the placebo group. The difference became more significant by Week 12, with 40.9% in the memantine group showing a decrease in Y-BOCS score vs -0.3% in the placebo group. This resulted in 73.3% of patients achieving treatment response.

- Eight weeks of memantine augmentation was necessary to observe a significant improvement in OCD symptoms, and 12 weeks was needed for treatment response.

- The mean Y-BOCS total score decreased significantly in the memantine group from Week 4 to Week 8 (16.8%) and again from Week 8 to Week 12 (28.5%).

- The memantine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- Memantine augmentation in patients with severe OCD who do not respond to an SRI is effective and well-tolerated.

4. Shalbafan M, Malekpour F, Tadayon Najafabadi B, et al. Fluvoxamine combination therapy with tropisetron for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1407- 1414. doi:10.1177/0269881119878177

Studies have demonstrated the involvement of the amygdala, medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in OCD. Additionally, studies have also investigated the role of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate system dysregulation in the pathology of OCD.

The 5-HT3 receptors are ligand-gated ion channels found in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. Studies of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as ondansetron and granisetron have shown beneficial results in augmentation with SSRIs for patients with OCD.11 Tropisetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, is highly lipophilic and able to cross the blood brain barrier. It also has dopamine-inhibiting properties that could have benefits in OCD management. Shalbafan et al13 evaluated the efficacy of tropisetron augmentation to fluvoxamine for patients with OCD.

Study design

- In a 10-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial, 108 individuals age 18 to 60 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had a Y-BOCS score >21 received fluvoxamine plus tropisetron or fluvoxamine plus placebo. A total of 48 (44.4%) participants in each group completed the trial. Participants were evaluated using the Y-BOCS scale at baseline and at Week 4 and Week 10.

- The primary outcome was decrease in total Y-BOCS score from baseline to Week 10. The secondary outcome was the difference in change in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores between the groups.

Outcomes

- The Y-BOCS total score was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P = .975). Repeated measures analysis of variance determined a significant effect for time in both tropisetron and placebo groups (Greenhouse-Geisser F [2.72–2303.84] = 152.25, P < .001; and Greenhouse-Geisser F [1.37–1736.81] = 75.57, P < .001, respectively). At Week 10, 35 participants in the tropisetron group and 19 participants in the placebo group were complete responders.

- The baseline Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscales did not significantly differ between treatment groups.

Conclusion

- Compared with participants in the placebo group, those in the tropisetron group experienced a significantly greater reduction in OCD symptoms as measured by Y-BOCS score. More participants in the tropisetron group experienced complete response and remission.

- This study demonstrated that compared with placebo, when administered as augmentation with fluvoxamine, tropisetron can have beneficial effects for patients with OCD.

Continue to: Reference 5...

5. Yousefzadeh F, Sahebolzamani E, Sadri A, et al. 5-Hydroxytryptophan as adjuvant therapy in treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a doubleblind randomized trial with placebo control. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(5):254- 262. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000321

Nutraceuticals such as glycine, milk thistle, myoinositol, and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptophan) have been proposed as augmentation options for OCD. Yousefzadeh et al14 investigated the effectiveness of using 5-hydroxytryptophan in treating OCD.

Study design

- In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind study, 60 patients who met DSM-5 criteria for moderate to severe OCD (Y-BOCS score >21) were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine plus 5-hydroxytryptophan 100 mg twice daily or fluoxetine plus placebo.

- All patients were administered fluoxetine 20 mg/d for the first 4 weeks of the study followed by fluoxetine 60 mg/d for the remainder of the trial.

- Symptoms were assessed using the Y-BOCS at baseline, Week 4, Week 8, and Week 12.

- The primary outcome measure was the difference between the 2 groups in change in Y-BOCS total score from baseline to the end of the trial. Secondary outcome measures were the differences in the Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores from baseline to Week 12.

Outcomes

- Compared to the placebo group, the 5-hydroxytryptophan group experienced a statistically significant greater improvement in Y-BOCS total score from baseline to Week 8 (P = .002) and Week 12 (P < .001).

- General linear model repeated measure showed significant effects for time × treatment interaction on Y-BOCS total (F = 12.07, df = 2.29, P < .001), obsession subscale (F = 8.25, df = 1.91, P = .001), and compulsion subscale scores (F = 6.64, df = 2.01, P = .002).

- The 5-hydroxytryptophan group demonstrated higher partial and complete treatment response rates (P = .032 and P = .001, respectively) as determined by change in Y-BOCS total score.

- The 5-hydroxytryptophan group showed a significant improvement from baseline to Week 12 in Y-BOCS obsession subscale score (5.23 ± 2.33 vs 3.53 ± 2.13, P = .009).

- There was a significant change from baseline to the end of the trial in the Y-BOCS compulsion subscale score (3.88 ± 2.04 vs 2.30 ± 1.37, P = .002).

Conclusion

- This trial demonstrated the potential benefits of 5-hydroxytryptophan in combination with fluoxetine for patients with OCD.

6. Mowla A, Ghaedsharaf M. Pregabalin augmentation for resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):552-556. doi:10.1017/S1092852919001500

Glutamatergic dysfunction has been identified as a potential cause of OCD. Studies have found elevated levels of glutamatergic transmission in the cortical-striatal-thalamic circuit of the brain and elevated glutamate concentration in the CSF in patients with OCD. Pregabalin has multiple mechanisms of action that inhibit the release of glutamate. Mowla et al15 evaluated pregabalin as an augmentation treatment for resistant OCD.

Study design

- This 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of adjunctive pregabalin in 56 patients who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had not responded to ≥12 weeks of treatment with an adequate and stable dose of sertraline (baseline Y-BOCS score ≥18).

- Individuals who had other major psychiatric disorders, major medical problems, were pregnant, or had past substance or alcohol abuse were excluded.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive sertraline plus pregabalin (n = 28) or sertraline plus placebo (n = 28). Mean sertraline dosage was 256.5 mg/d; range was 100 mg/d to 300 mg/d. Pregabalin was started at 75 mg/d and increased by 75 mg increments weekly. The mean dosage was 185.9 mg/d; range was 75 mg/d to 225 mg/d.

- The primary outcome measure was change in Y-BOCS score. A decrease >35% in Y-BOCS score was considered a significant response rate.

Outcomes

- There was a statistically significant decrease in Y-BOCS score in patients who received pregabalin. In the pregabalin group, 57.14% of patients (n = 16) showed a >35% decrease in Y-BOCS score compared with 7.14% of patients (n = 2) in the placebo group (P < .01).

- The pregabalin group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- In patients with treatment-resistant OCD who did not respond to sertraline monotherapy, augmentation with pregabalin significantly decreases Y-BOCS scores compared with placebo.

Continue to: Reference 7...

7. Zheng H, Jia F, Han H, et al. Combined fluvoxamine and extended-release methylphenidate improved treatment response compared to fluvoxamine alone in patients with treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind, placebocontrolled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):397-404. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro. 2018.12.010

Recent evidence suggests dysregulation of serotonin and dopamine in patients with OCD. Methylphenidate is a dopamine and norepinephrine inhibitor and releaser. A limited number of studies have suggested stimulants might be useful for OCD patients. Zheng et al16 conducted a pilot trial to determine whether methylphenidate augmentation may be of benefit in the management of outpatients with OCD.

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, 44 patients (29 [66%] men, with a mean [SD] age of 24.7 [6]) with treatment-refractory OCD were randomized to receive fluvoxamine 250 mg/d plus methylphenidate extended-release (MPH-ER) 36 mg/d or fluvoxamine 250 mg/d plus placebo. The MPH-ER dose was 18 mg/d for the first 4 weeks and 36 mg/d for the rest of the trial.

- Biweekly assessments consisted of scores on the Y-BOCS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

- The primary outcomes were improvement in Y-BOCS score and the clinical response rate. Secondary outcomes included a change in score on the Y-BOCS subscales, HARS, and HAM-A. Data were analyzed with the intention-to-treat sample.

Outcomes

- Forty-one patients finished the trial. The baseline Y-BOCS total scores and subscale scores did not differ significantly between the 2 groups.

- Improvements in Y-BOCS total score and obsession subscale score were more prominent in the fluvoxamine plus MPH-ER group compared with the placebo group (P < .001).

- HDRS score decreased in both the placebo and MPH-ER groups. HAM-A scores decreased significantly in the MPH-ER plus fluvoxamine group compared with the placebo group.

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated that the combination of fluvoxamine and MPH-ER produces a higher and faster response rate than fluvoxamine plus placebo in patients with OCD.

8. Arabzadeh S, Shahhossenie M, Mesgarpour B, et al. L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine in treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(4). doi:10.1002/hup.2584

Glutamate dysregulation is implicated in the pathogenesis of OCD. Glutamate-modulating agents have been used to treat OCD. Studies have shown L-carnosine has a neuroprotective role via its modulatory effect on glutamate. Arabzadeh et al17 evaluated the efficacy of L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine for treating OCD.

Study design

- This 10-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of adjunctive L-carnosine in 40 patients age 18 to 60 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had moderate to severe OCD (Y-BOCS score ≥21).

- Individuals with any other DSM-5 major psychiatric disorders, serious medical or neurologic illness, substance dependence (other than caffeine or nicotine), mental retardation (based on clinical judgment), were pregnant or breastfeeding, had any contraindication for the use of L‐carnosine or fluvoxamine, or received any psychotropic drugs in the previous 6 weeks were excluded.

- Participants received fluvoxamine 100 mg/d for the first 4 weeks and 200 mg/d for the next 6 weeks plus either L-carnosine 500 mg twice daily or placebo. This dosage of L-carnosine was chosen because previously it had been tolerated and effective.

- The primary outcome measure was difference in Y-BOCS total scores. Secondary outcomes were differences in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores and differences in change in score on Y-BOCS total and subscale scores from baseline.

Outcomes

- The L-carnosine group experienced a significant decrease in Y-BOCS total score (P < .001), obsession subscale score (P < .01), and compulsion subscale score (P < .01).

- The group that received fluvoxamine plus L-carnosine also experienced a more complete response (P = .03).

- The L-carnosine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- L-carnosine significantly reduces OCD symptoms when used as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, et al. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(1):53-63.

3. Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley, R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):1011-1030.

4. Franklin ME, Foa EB. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:229-243.

5. Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7 Suppl):5-53.

6. Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(3):375-391.

7. Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, et al. Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(2):181-191.

8. Atmaca M. Treatment-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:127-133.

9. Barth M, Kriston L, Klostermann S, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse events: meta-regression and mediation analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(2):114-119.

10. NaderiS, Faghih H, Aqamolaei A, et al. Amantadine as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(4):169-174. doi:10.1111/pcn.12803

11. SharafkhahM, Aghakarim Alamdar M, MassoudifarA, et al. Comparing the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(5):222-233. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000267

12. ModarresiA, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(6):263-269. doi:10.1055/s-0043-12026

13. Shalbafan M, Malekpour F, Tadayon Najafabadi B, et al. Fluvoxamine combination therapy with tropisetron for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1407-1414. doi:10.1177/0269881119878177

14. Yousefzadeh F, Sahebolzamani E, Sadri A, et al. 5-Hydroxytryptophan as adjuvant therapy in treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(5):254-262. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000321

15. Mowla A, Ghaedsharaf M. Pregabalin augmentation for resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):552-556. doi:10.1017/S1092852919001500

16. Zheng H, Jia F, Han H, et al.Combined fluvoxamine and extended-release methylphenidate improved treatment response compared to fluvoxamine alone in patients with treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):397-404. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.12.010

17. Arabzadeh S, Shahhossenie M, Mesgarpour B, et al. L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine in treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(4). doi:10.1002/hup.2584

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic, debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder that affects 1% to 3% of the population worldwide.1,2 Together, serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) and cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) are considered the first-line treatment for OCD.3 In children and adults, CBT is considered at least as effective as pharmacotherapy.4 Despite being an effective treatment, CBT continues to have barriers to its widespread use, including limited availability of trained CBT therapists, delayed clinical response, and high costs.5

Only approximately one-half of patients with OCD respond to SRI therapy, and a considerable percentage (30% to 40%) show significant residual symptoms even after multiple trials of SRIs.6-8 In addition, SRIs may have adverse effects (eg, sexual dysfunction, gastrointestinal symptoms) that impair patient adherence to these medications.9 Therefore, finding better treatment options is important for managing patients with OCD.

Augmentation strategies are recommended for patients who show partial response to SRI treatment or poor response to multiple SRIs. Augmentation typically includes incorporating additional medications with the primary drug with the goal of boosting the therapeutic efficacy of the primary drug. Typically, these additional medications have different mechanisms of action. However, there are no large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to inform treatment augmentation after first-line treatments for OCD produce suboptimal outcomes. The available evidence is predominantly based on small-scale RCTs, open-label trials, and case series.

In this article, we review the evidence for treatment augmentation strategies for OCD and summarize 8 studies that show promising results (Table10-17). We focus only on pharmacologic agents and do not include other biological interventions, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area, ablative neurosurgery, or deep brain stimulation.

Continue to: Reference 1...

1. Naderi S, Faghih H , Aqamolaei A, et al. Amantadine as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe obsessivecompulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(4):169-174. doi:10.1111/ pcn.12803

Numerous studies support the role of glutamate dysregulation in the pathophysiology of OCD. Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) abnormalities play a major role in the pathophysiology of OCD as suggested by neuroimaging research studies that indicate glutamate is the fundamental neurotransmitter of the CSTC circuit. Dysregulation of glutamatergic signaling within this circuit has been linked to OCD. Patients with OCD have been found to have an increase of glutamate in the CSF. As a result, medications that affect glutamate levels can be used to treat patients with OCD who do not respond to first-line agents. In patients already taking SRIs, augmentation of glutamate-modulating medications can reduce OCD symptoms. As an uncompetitive antagonist of the N-methyl-

Naderi et al10 evaluated amantadine as augmentative therapy to fluvoxamine for treating patients with moderate to severe OCD.

Study design

- This 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of amantadine as an augmentative agent to fluvoxamine in 106 patients age 18 to 60 with moderate to severe OCD.

- Participants met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had a Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score >21. Participants were excluded if they had any substance dependence; an IQ <70; any other Axis I mental disorder; any serious cardiac, renal, or hepatic disease; had received psychotropic medications during the last 6 weeks, were pregnant or breastfeeding, or had rising liver transaminases to 3 times the upper limit of normal or higher.

- Participants received fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily plus amantadine 100 mg/d, or fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily plus placebo. All patients received fluvoxamine 100 mg/d for 28 days followed by 200 mg/d for the remainder of the trial.

- The primary outcome measure was difference in Y-BOCS total scores between the amantadine and placebo groups. The secondary outcome was the difference in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores.

Outcomes

- Patients who received amantadine augmentation experienced a significant reduction in Y-BOCS total score (P < .001) and obsession subscale score (P < .01).

- The amantadine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

- Amantadine is an effective adjuvant to fluvoxamine for reducing OCD symptoms.

Conclusion

- Ondansetron and granisetron can be beneficial as an augmentation strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

2. Sharafkhah M, Aghakarim Alamdar M, Massoudifar A, et al. Comparing the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(5):222- 233. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000267

Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered a first-line treatment when teamed with CBT and antipsychotic augmentation, symptom resolution is not always achieved, and treatment resistance is a common problem. Sharafkhah et al11 compared the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation specifically for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

Study Design

- In this 18-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 135 patients with treatment-resistant OCD who were previously treated with a combination of an SSRI and an antipsychotic received augmentation with ondansetron (n = 45, 4 mg/d), granisetron (n = 45, 2 mg/d), or placebo.

- Patients were rated using Y-BOCS every 2 weeks during phase I (intervention period), which lasted 14 weeks. After completing the intervention, patients were followed for 4 more weeks during phase II (discontinuation period).

- The aim of this study was to determine the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of ondansetron vs granisetron as augmentation for patients with treatment-resistant OCD. A secondary aim was to determine the rate of relapse of OCD symptoms after discontinuing ondansetron as compared with granisetron at 4 weeks after intervention.

Outcomes

- At Week 14, the reductions in Y-BOCS scores in the ondansetron, granisetron, and placebo groups were 41.5%, 39.7%, and 15.2%, respectively (P = .001). The reduction in Y-BOCS score in the ondansetron and granisetron groups was significantly greater than placebo at all phase I visits.

- Complete response was higher in the ondansetron group compared with the granisetron group (P = .041).

- Y-BOCS scores increased in both the ondansetron and granisetron groups during the discontinuation phase, but OCD symptoms were not significantly exacerbated.

Conclusion

- Ondansetron and granisetron can be beneficial as an augmentation strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

3. Modarresi A, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitorrefractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(6):263-269. doi:10.1055/s-0043-120268

Increased glutamate levels in CSF, glutamatergic overactivity, and polymorphisms of genes coding the NMDA receptor have been shown to contribute to the occurrence of OCD. Memantine is a noncompetitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor. Various control trials have shown augmentation with memantine 5 mg/d to 20 mg/d significantly reduced symptom severity in patients with moderate to severe OCD. Modarresi et al12 evaluated memantine as a treatment option for patients with severe OCD who did not respond to SRI monotherapy.

Study design

- This 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of memantine augmentation in 32 patients age 18 to 40 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD, had a Y-BOCS score ≥24, and no psychiatric comorbidity. Participants had not responded to ≥3 adequate trials (minimum 3 months) of SRI therapy, 1 of which was clomipramine.

- Individuals were excluded if they were undergoing CBT; had an additional anxiety disorder, mood disorder, or current drug or alcohol use disorder, or any systemic disorder; had a history of seizures; were pregnant or breastfeeding; or had a history of memantine use.

- Participants already receiving the maximum tolerated dose of an SRI received augmentation with memantine 20 mg/d or placebo.

- The primary outcome measure was change in Y-BOCS score from baseline. The secondary outcome was the number of individuals who achieved treatment response (defined as ≥35% reduction in Y-BOCS score).

Continue to: Outcomes...

Outcomes

- There was a statistically significant difference in Y-BOCS score in patients treated with memantine at Week 8 and Week 12 vs those who received placebo. By Week 8, 17.2% of patients in the memantine group showed a decrease in Y-BOCS score, compared with -0.8% patients in the placebo group. The difference became more significant by Week 12, with 40.9% in the memantine group showing a decrease in Y-BOCS score vs -0.3% in the placebo group. This resulted in 73.3% of patients achieving treatment response.

- Eight weeks of memantine augmentation was necessary to observe a significant improvement in OCD symptoms, and 12 weeks was needed for treatment response.

- The mean Y-BOCS total score decreased significantly in the memantine group from Week 4 to Week 8 (16.8%) and again from Week 8 to Week 12 (28.5%).

- The memantine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- Memantine augmentation in patients with severe OCD who do not respond to an SRI is effective and well-tolerated.

4. Shalbafan M, Malekpour F, Tadayon Najafabadi B, et al. Fluvoxamine combination therapy with tropisetron for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1407- 1414. doi:10.1177/0269881119878177

Studies have demonstrated the involvement of the amygdala, medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in OCD. Additionally, studies have also investigated the role of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate system dysregulation in the pathology of OCD.

The 5-HT3 receptors are ligand-gated ion channels found in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. Studies of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as ondansetron and granisetron have shown beneficial results in augmentation with SSRIs for patients with OCD.11 Tropisetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, is highly lipophilic and able to cross the blood brain barrier. It also has dopamine-inhibiting properties that could have benefits in OCD management. Shalbafan et al13 evaluated the efficacy of tropisetron augmentation to fluvoxamine for patients with OCD.

Study design

- In a 10-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial, 108 individuals age 18 to 60 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had a Y-BOCS score >21 received fluvoxamine plus tropisetron or fluvoxamine plus placebo. A total of 48 (44.4%) participants in each group completed the trial. Participants were evaluated using the Y-BOCS scale at baseline and at Week 4 and Week 10.

- The primary outcome was decrease in total Y-BOCS score from baseline to Week 10. The secondary outcome was the difference in change in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores between the groups.

Outcomes

- The Y-BOCS total score was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P = .975). Repeated measures analysis of variance determined a significant effect for time in both tropisetron and placebo groups (Greenhouse-Geisser F [2.72–2303.84] = 152.25, P < .001; and Greenhouse-Geisser F [1.37–1736.81] = 75.57, P < .001, respectively). At Week 10, 35 participants in the tropisetron group and 19 participants in the placebo group were complete responders.

- The baseline Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscales did not significantly differ between treatment groups.

Conclusion

- Compared with participants in the placebo group, those in the tropisetron group experienced a significantly greater reduction in OCD symptoms as measured by Y-BOCS score. More participants in the tropisetron group experienced complete response and remission.

- This study demonstrated that compared with placebo, when administered as augmentation with fluvoxamine, tropisetron can have beneficial effects for patients with OCD.

Continue to: Reference 5...

5. Yousefzadeh F, Sahebolzamani E, Sadri A, et al. 5-Hydroxytryptophan as adjuvant therapy in treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a doubleblind randomized trial with placebo control. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(5):254- 262. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000321

Nutraceuticals such as glycine, milk thistle, myoinositol, and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptophan) have been proposed as augmentation options for OCD. Yousefzadeh et al14 investigated the effectiveness of using 5-hydroxytryptophan in treating OCD.

Study design

- In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind study, 60 patients who met DSM-5 criteria for moderate to severe OCD (Y-BOCS score >21) were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine plus 5-hydroxytryptophan 100 mg twice daily or fluoxetine plus placebo.

- All patients were administered fluoxetine 20 mg/d for the first 4 weeks of the study followed by fluoxetine 60 mg/d for the remainder of the trial.

- Symptoms were assessed using the Y-BOCS at baseline, Week 4, Week 8, and Week 12.

- The primary outcome measure was the difference between the 2 groups in change in Y-BOCS total score from baseline to the end of the trial. Secondary outcome measures were the differences in the Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores from baseline to Week 12.

Outcomes

- Compared to the placebo group, the 5-hydroxytryptophan group experienced a statistically significant greater improvement in Y-BOCS total score from baseline to Week 8 (P = .002) and Week 12 (P < .001).

- General linear model repeated measure showed significant effects for time × treatment interaction on Y-BOCS total (F = 12.07, df = 2.29, P < .001), obsession subscale (F = 8.25, df = 1.91, P = .001), and compulsion subscale scores (F = 6.64, df = 2.01, P = .002).

- The 5-hydroxytryptophan group demonstrated higher partial and complete treatment response rates (P = .032 and P = .001, respectively) as determined by change in Y-BOCS total score.

- The 5-hydroxytryptophan group showed a significant improvement from baseline to Week 12 in Y-BOCS obsession subscale score (5.23 ± 2.33 vs 3.53 ± 2.13, P = .009).

- There was a significant change from baseline to the end of the trial in the Y-BOCS compulsion subscale score (3.88 ± 2.04 vs 2.30 ± 1.37, P = .002).

Conclusion

- This trial demonstrated the potential benefits of 5-hydroxytryptophan in combination with fluoxetine for patients with OCD.

6. Mowla A, Ghaedsharaf M. Pregabalin augmentation for resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):552-556. doi:10.1017/S1092852919001500

Glutamatergic dysfunction has been identified as a potential cause of OCD. Studies have found elevated levels of glutamatergic transmission in the cortical-striatal-thalamic circuit of the brain and elevated glutamate concentration in the CSF in patients with OCD. Pregabalin has multiple mechanisms of action that inhibit the release of glutamate. Mowla et al15 evaluated pregabalin as an augmentation treatment for resistant OCD.

Study design

- This 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of adjunctive pregabalin in 56 patients who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had not responded to ≥12 weeks of treatment with an adequate and stable dose of sertraline (baseline Y-BOCS score ≥18).

- Individuals who had other major psychiatric disorders, major medical problems, were pregnant, or had past substance or alcohol abuse were excluded.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive sertraline plus pregabalin (n = 28) or sertraline plus placebo (n = 28). Mean sertraline dosage was 256.5 mg/d; range was 100 mg/d to 300 mg/d. Pregabalin was started at 75 mg/d and increased by 75 mg increments weekly. The mean dosage was 185.9 mg/d; range was 75 mg/d to 225 mg/d.

- The primary outcome measure was change in Y-BOCS score. A decrease >35% in Y-BOCS score was considered a significant response rate.

Outcomes

- There was a statistically significant decrease in Y-BOCS score in patients who received pregabalin. In the pregabalin group, 57.14% of patients (n = 16) showed a >35% decrease in Y-BOCS score compared with 7.14% of patients (n = 2) in the placebo group (P < .01).

- The pregabalin group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- In patients with treatment-resistant OCD who did not respond to sertraline monotherapy, augmentation with pregabalin significantly decreases Y-BOCS scores compared with placebo.

Continue to: Reference 7...

7. Zheng H, Jia F, Han H, et al. Combined fluvoxamine and extended-release methylphenidate improved treatment response compared to fluvoxamine alone in patients with treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind, placebocontrolled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):397-404. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro. 2018.12.010

Recent evidence suggests dysregulation of serotonin and dopamine in patients with OCD. Methylphenidate is a dopamine and norepinephrine inhibitor and releaser. A limited number of studies have suggested stimulants might be useful for OCD patients. Zheng et al16 conducted a pilot trial to determine whether methylphenidate augmentation may be of benefit in the management of outpatients with OCD.

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, 44 patients (29 [66%] men, with a mean [SD] age of 24.7 [6]) with treatment-refractory OCD were randomized to receive fluvoxamine 250 mg/d plus methylphenidate extended-release (MPH-ER) 36 mg/d or fluvoxamine 250 mg/d plus placebo. The MPH-ER dose was 18 mg/d for the first 4 weeks and 36 mg/d for the rest of the trial.

- Biweekly assessments consisted of scores on the Y-BOCS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

- The primary outcomes were improvement in Y-BOCS score and the clinical response rate. Secondary outcomes included a change in score on the Y-BOCS subscales, HARS, and HAM-A. Data were analyzed with the intention-to-treat sample.

Outcomes

- Forty-one patients finished the trial. The baseline Y-BOCS total scores and subscale scores did not differ significantly between the 2 groups.

- Improvements in Y-BOCS total score and obsession subscale score were more prominent in the fluvoxamine plus MPH-ER group compared with the placebo group (P < .001).

- HDRS score decreased in both the placebo and MPH-ER groups. HAM-A scores decreased significantly in the MPH-ER plus fluvoxamine group compared with the placebo group.

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated that the combination of fluvoxamine and MPH-ER produces a higher and faster response rate than fluvoxamine plus placebo in patients with OCD.

8. Arabzadeh S, Shahhossenie M, Mesgarpour B, et al. L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine in treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(4). doi:10.1002/hup.2584

Glutamate dysregulation is implicated in the pathogenesis of OCD. Glutamate-modulating agents have been used to treat OCD. Studies have shown L-carnosine has a neuroprotective role via its modulatory effect on glutamate. Arabzadeh et al17 evaluated the efficacy of L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine for treating OCD.

Study design

- This 10-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of adjunctive L-carnosine in 40 patients age 18 to 60 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had moderate to severe OCD (Y-BOCS score ≥21).

- Individuals with any other DSM-5 major psychiatric disorders, serious medical or neurologic illness, substance dependence (other than caffeine or nicotine), mental retardation (based on clinical judgment), were pregnant or breastfeeding, had any contraindication for the use of L‐carnosine or fluvoxamine, or received any psychotropic drugs in the previous 6 weeks were excluded.

- Participants received fluvoxamine 100 mg/d for the first 4 weeks and 200 mg/d for the next 6 weeks plus either L-carnosine 500 mg twice daily or placebo. This dosage of L-carnosine was chosen because previously it had been tolerated and effective.

- The primary outcome measure was difference in Y-BOCS total scores. Secondary outcomes were differences in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores and differences in change in score on Y-BOCS total and subscale scores from baseline.

Outcomes

- The L-carnosine group experienced a significant decrease in Y-BOCS total score (P < .001), obsession subscale score (P < .01), and compulsion subscale score (P < .01).

- The group that received fluvoxamine plus L-carnosine also experienced a more complete response (P = .03).

- The L-carnosine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- L-carnosine significantly reduces OCD symptoms when used as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic, debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder that affects 1% to 3% of the population worldwide.1,2 Together, serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) and cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) are considered the first-line treatment for OCD.3 In children and adults, CBT is considered at least as effective as pharmacotherapy.4 Despite being an effective treatment, CBT continues to have barriers to its widespread use, including limited availability of trained CBT therapists, delayed clinical response, and high costs.5

Only approximately one-half of patients with OCD respond to SRI therapy, and a considerable percentage (30% to 40%) show significant residual symptoms even after multiple trials of SRIs.6-8 In addition, SRIs may have adverse effects (eg, sexual dysfunction, gastrointestinal symptoms) that impair patient adherence to these medications.9 Therefore, finding better treatment options is important for managing patients with OCD.

Augmentation strategies are recommended for patients who show partial response to SRI treatment or poor response to multiple SRIs. Augmentation typically includes incorporating additional medications with the primary drug with the goal of boosting the therapeutic efficacy of the primary drug. Typically, these additional medications have different mechanisms of action. However, there are no large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to inform treatment augmentation after first-line treatments for OCD produce suboptimal outcomes. The available evidence is predominantly based on small-scale RCTs, open-label trials, and case series.

In this article, we review the evidence for treatment augmentation strategies for OCD and summarize 8 studies that show promising results (Table10-17). We focus only on pharmacologic agents and do not include other biological interventions, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area, ablative neurosurgery, or deep brain stimulation.

Continue to: Reference 1...

1. Naderi S, Faghih H , Aqamolaei A, et al. Amantadine as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe obsessivecompulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(4):169-174. doi:10.1111/ pcn.12803

Numerous studies support the role of glutamate dysregulation in the pathophysiology of OCD. Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) abnormalities play a major role in the pathophysiology of OCD as suggested by neuroimaging research studies that indicate glutamate is the fundamental neurotransmitter of the CSTC circuit. Dysregulation of glutamatergic signaling within this circuit has been linked to OCD. Patients with OCD have been found to have an increase of glutamate in the CSF. As a result, medications that affect glutamate levels can be used to treat patients with OCD who do not respond to first-line agents. In patients already taking SRIs, augmentation of glutamate-modulating medications can reduce OCD symptoms. As an uncompetitive antagonist of the N-methyl-

Naderi et al10 evaluated amantadine as augmentative therapy to fluvoxamine for treating patients with moderate to severe OCD.

Study design

- This 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of amantadine as an augmentative agent to fluvoxamine in 106 patients age 18 to 60 with moderate to severe OCD.

- Participants met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had a Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score >21. Participants were excluded if they had any substance dependence; an IQ <70; any other Axis I mental disorder; any serious cardiac, renal, or hepatic disease; had received psychotropic medications during the last 6 weeks, were pregnant or breastfeeding, or had rising liver transaminases to 3 times the upper limit of normal or higher.

- Participants received fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily plus amantadine 100 mg/d, or fluvoxamine 100 mg twice daily plus placebo. All patients received fluvoxamine 100 mg/d for 28 days followed by 200 mg/d for the remainder of the trial.

- The primary outcome measure was difference in Y-BOCS total scores between the amantadine and placebo groups. The secondary outcome was the difference in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores.

Outcomes

- Patients who received amantadine augmentation experienced a significant reduction in Y-BOCS total score (P < .001) and obsession subscale score (P < .01).

- The amantadine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

- Amantadine is an effective adjuvant to fluvoxamine for reducing OCD symptoms.

Conclusion

- Ondansetron and granisetron can be beneficial as an augmentation strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

2. Sharafkhah M, Aghakarim Alamdar M, Massoudifar A, et al. Comparing the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(5):222- 233. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000267

Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered a first-line treatment when teamed with CBT and antipsychotic augmentation, symptom resolution is not always achieved, and treatment resistance is a common problem. Sharafkhah et al11 compared the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation specifically for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

Study Design

- In this 18-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 135 patients with treatment-resistant OCD who were previously treated with a combination of an SSRI and an antipsychotic received augmentation with ondansetron (n = 45, 4 mg/d), granisetron (n = 45, 2 mg/d), or placebo.

- Patients were rated using Y-BOCS every 2 weeks during phase I (intervention period), which lasted 14 weeks. After completing the intervention, patients were followed for 4 more weeks during phase II (discontinuation period).

- The aim of this study was to determine the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of ondansetron vs granisetron as augmentation for patients with treatment-resistant OCD. A secondary aim was to determine the rate of relapse of OCD symptoms after discontinuing ondansetron as compared with granisetron at 4 weeks after intervention.

Outcomes

- At Week 14, the reductions in Y-BOCS scores in the ondansetron, granisetron, and placebo groups were 41.5%, 39.7%, and 15.2%, respectively (P = .001). The reduction in Y-BOCS score in the ondansetron and granisetron groups was significantly greater than placebo at all phase I visits.

- Complete response was higher in the ondansetron group compared with the granisetron group (P = .041).

- Y-BOCS scores increased in both the ondansetron and granisetron groups during the discontinuation phase, but OCD symptoms were not significantly exacerbated.

Conclusion

- Ondansetron and granisetron can be beneficial as an augmentation strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD.

3. Modarresi A, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitorrefractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(6):263-269. doi:10.1055/s-0043-120268

Increased glutamate levels in CSF, glutamatergic overactivity, and polymorphisms of genes coding the NMDA receptor have been shown to contribute to the occurrence of OCD. Memantine is a noncompetitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor. Various control trials have shown augmentation with memantine 5 mg/d to 20 mg/d significantly reduced symptom severity in patients with moderate to severe OCD. Modarresi et al12 evaluated memantine as a treatment option for patients with severe OCD who did not respond to SRI monotherapy.

Study design

- This 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of memantine augmentation in 32 patients age 18 to 40 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD, had a Y-BOCS score ≥24, and no psychiatric comorbidity. Participants had not responded to ≥3 adequate trials (minimum 3 months) of SRI therapy, 1 of which was clomipramine.

- Individuals were excluded if they were undergoing CBT; had an additional anxiety disorder, mood disorder, or current drug or alcohol use disorder, or any systemic disorder; had a history of seizures; were pregnant or breastfeeding; or had a history of memantine use.

- Participants already receiving the maximum tolerated dose of an SRI received augmentation with memantine 20 mg/d or placebo.

- The primary outcome measure was change in Y-BOCS score from baseline. The secondary outcome was the number of individuals who achieved treatment response (defined as ≥35% reduction in Y-BOCS score).

Continue to: Outcomes...

Outcomes

- There was a statistically significant difference in Y-BOCS score in patients treated with memantine at Week 8 and Week 12 vs those who received placebo. By Week 8, 17.2% of patients in the memantine group showed a decrease in Y-BOCS score, compared with -0.8% patients in the placebo group. The difference became more significant by Week 12, with 40.9% in the memantine group showing a decrease in Y-BOCS score vs -0.3% in the placebo group. This resulted in 73.3% of patients achieving treatment response.

- Eight weeks of memantine augmentation was necessary to observe a significant improvement in OCD symptoms, and 12 weeks was needed for treatment response.

- The mean Y-BOCS total score decreased significantly in the memantine group from Week 4 to Week 8 (16.8%) and again from Week 8 to Week 12 (28.5%).

- The memantine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- Memantine augmentation in patients with severe OCD who do not respond to an SRI is effective and well-tolerated.

4. Shalbafan M, Malekpour F, Tadayon Najafabadi B, et al. Fluvoxamine combination therapy with tropisetron for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1407- 1414. doi:10.1177/0269881119878177

Studies have demonstrated the involvement of the amygdala, medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in OCD. Additionally, studies have also investigated the role of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate system dysregulation in the pathology of OCD.

The 5-HT3 receptors are ligand-gated ion channels found in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. Studies of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as ondansetron and granisetron have shown beneficial results in augmentation with SSRIs for patients with OCD.11 Tropisetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, is highly lipophilic and able to cross the blood brain barrier. It also has dopamine-inhibiting properties that could have benefits in OCD management. Shalbafan et al13 evaluated the efficacy of tropisetron augmentation to fluvoxamine for patients with OCD.

Study design

- In a 10-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial, 108 individuals age 18 to 60 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had a Y-BOCS score >21 received fluvoxamine plus tropisetron or fluvoxamine plus placebo. A total of 48 (44.4%) participants in each group completed the trial. Participants were evaluated using the Y-BOCS scale at baseline and at Week 4 and Week 10.

- The primary outcome was decrease in total Y-BOCS score from baseline to Week 10. The secondary outcome was the difference in change in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores between the groups.

Outcomes

- The Y-BOCS total score was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P = .975). Repeated measures analysis of variance determined a significant effect for time in both tropisetron and placebo groups (Greenhouse-Geisser F [2.72–2303.84] = 152.25, P < .001; and Greenhouse-Geisser F [1.37–1736.81] = 75.57, P < .001, respectively). At Week 10, 35 participants in the tropisetron group and 19 participants in the placebo group were complete responders.

- The baseline Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscales did not significantly differ between treatment groups.

Conclusion

- Compared with participants in the placebo group, those in the tropisetron group experienced a significantly greater reduction in OCD symptoms as measured by Y-BOCS score. More participants in the tropisetron group experienced complete response and remission.

- This study demonstrated that compared with placebo, when administered as augmentation with fluvoxamine, tropisetron can have beneficial effects for patients with OCD.

Continue to: Reference 5...

5. Yousefzadeh F, Sahebolzamani E, Sadri A, et al. 5-Hydroxytryptophan as adjuvant therapy in treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a doubleblind randomized trial with placebo control. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(5):254- 262. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000321

Nutraceuticals such as glycine, milk thistle, myoinositol, and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptophan) have been proposed as augmentation options for OCD. Yousefzadeh et al14 investigated the effectiveness of using 5-hydroxytryptophan in treating OCD.

Study design

- In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind study, 60 patients who met DSM-5 criteria for moderate to severe OCD (Y-BOCS score >21) were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine plus 5-hydroxytryptophan 100 mg twice daily or fluoxetine plus placebo.

- All patients were administered fluoxetine 20 mg/d for the first 4 weeks of the study followed by fluoxetine 60 mg/d for the remainder of the trial.

- Symptoms were assessed using the Y-BOCS at baseline, Week 4, Week 8, and Week 12.

- The primary outcome measure was the difference between the 2 groups in change in Y-BOCS total score from baseline to the end of the trial. Secondary outcome measures were the differences in the Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores from baseline to Week 12.

Outcomes

- Compared to the placebo group, the 5-hydroxytryptophan group experienced a statistically significant greater improvement in Y-BOCS total score from baseline to Week 8 (P = .002) and Week 12 (P < .001).

- General linear model repeated measure showed significant effects for time × treatment interaction on Y-BOCS total (F = 12.07, df = 2.29, P < .001), obsession subscale (F = 8.25, df = 1.91, P = .001), and compulsion subscale scores (F = 6.64, df = 2.01, P = .002).

- The 5-hydroxytryptophan group demonstrated higher partial and complete treatment response rates (P = .032 and P = .001, respectively) as determined by change in Y-BOCS total score.

- The 5-hydroxytryptophan group showed a significant improvement from baseline to Week 12 in Y-BOCS obsession subscale score (5.23 ± 2.33 vs 3.53 ± 2.13, P = .009).

- There was a significant change from baseline to the end of the trial in the Y-BOCS compulsion subscale score (3.88 ± 2.04 vs 2.30 ± 1.37, P = .002).

Conclusion

- This trial demonstrated the potential benefits of 5-hydroxytryptophan in combination with fluoxetine for patients with OCD.

6. Mowla A, Ghaedsharaf M. Pregabalin augmentation for resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):552-556. doi:10.1017/S1092852919001500

Glutamatergic dysfunction has been identified as a potential cause of OCD. Studies have found elevated levels of glutamatergic transmission in the cortical-striatal-thalamic circuit of the brain and elevated glutamate concentration in the CSF in patients with OCD. Pregabalin has multiple mechanisms of action that inhibit the release of glutamate. Mowla et al15 evaluated pregabalin as an augmentation treatment for resistant OCD.

Study design

- This 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of adjunctive pregabalin in 56 patients who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had not responded to ≥12 weeks of treatment with an adequate and stable dose of sertraline (baseline Y-BOCS score ≥18).

- Individuals who had other major psychiatric disorders, major medical problems, were pregnant, or had past substance or alcohol abuse were excluded.

- Participants were randomly assigned to receive sertraline plus pregabalin (n = 28) or sertraline plus placebo (n = 28). Mean sertraline dosage was 256.5 mg/d; range was 100 mg/d to 300 mg/d. Pregabalin was started at 75 mg/d and increased by 75 mg increments weekly. The mean dosage was 185.9 mg/d; range was 75 mg/d to 225 mg/d.

- The primary outcome measure was change in Y-BOCS score. A decrease >35% in Y-BOCS score was considered a significant response rate.

Outcomes

- There was a statistically significant decrease in Y-BOCS score in patients who received pregabalin. In the pregabalin group, 57.14% of patients (n = 16) showed a >35% decrease in Y-BOCS score compared with 7.14% of patients (n = 2) in the placebo group (P < .01).

- The pregabalin group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- In patients with treatment-resistant OCD who did not respond to sertraline monotherapy, augmentation with pregabalin significantly decreases Y-BOCS scores compared with placebo.

Continue to: Reference 7...

7. Zheng H, Jia F, Han H, et al. Combined fluvoxamine and extended-release methylphenidate improved treatment response compared to fluvoxamine alone in patients with treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind, placebocontrolled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):397-404. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro. 2018.12.010

Recent evidence suggests dysregulation of serotonin and dopamine in patients with OCD. Methylphenidate is a dopamine and norepinephrine inhibitor and releaser. A limited number of studies have suggested stimulants might be useful for OCD patients. Zheng et al16 conducted a pilot trial to determine whether methylphenidate augmentation may be of benefit in the management of outpatients with OCD.

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, 44 patients (29 [66%] men, with a mean [SD] age of 24.7 [6]) with treatment-refractory OCD were randomized to receive fluvoxamine 250 mg/d plus methylphenidate extended-release (MPH-ER) 36 mg/d or fluvoxamine 250 mg/d plus placebo. The MPH-ER dose was 18 mg/d for the first 4 weeks and 36 mg/d for the rest of the trial.

- Biweekly assessments consisted of scores on the Y-BOCS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

- The primary outcomes were improvement in Y-BOCS score and the clinical response rate. Secondary outcomes included a change in score on the Y-BOCS subscales, HARS, and HAM-A. Data were analyzed with the intention-to-treat sample.

Outcomes

- Forty-one patients finished the trial. The baseline Y-BOCS total scores and subscale scores did not differ significantly between the 2 groups.

- Improvements in Y-BOCS total score and obsession subscale score were more prominent in the fluvoxamine plus MPH-ER group compared with the placebo group (P < .001).

- HDRS score decreased in both the placebo and MPH-ER groups. HAM-A scores decreased significantly in the MPH-ER plus fluvoxamine group compared with the placebo group.

Conclusion

- This study demonstrated that the combination of fluvoxamine and MPH-ER produces a higher and faster response rate than fluvoxamine plus placebo in patients with OCD.

8. Arabzadeh S, Shahhossenie M, Mesgarpour B, et al. L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine in treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(4). doi:10.1002/hup.2584

Glutamate dysregulation is implicated in the pathogenesis of OCD. Glutamate-modulating agents have been used to treat OCD. Studies have shown L-carnosine has a neuroprotective role via its modulatory effect on glutamate. Arabzadeh et al17 evaluated the efficacy of L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine for treating OCD.

Study design

- This 10-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of adjunctive L-carnosine in 40 patients age 18 to 60 who met DSM-5 criteria for OCD and had moderate to severe OCD (Y-BOCS score ≥21).

- Individuals with any other DSM-5 major psychiatric disorders, serious medical or neurologic illness, substance dependence (other than caffeine or nicotine), mental retardation (based on clinical judgment), were pregnant or breastfeeding, had any contraindication for the use of L‐carnosine or fluvoxamine, or received any psychotropic drugs in the previous 6 weeks were excluded.

- Participants received fluvoxamine 100 mg/d for the first 4 weeks and 200 mg/d for the next 6 weeks plus either L-carnosine 500 mg twice daily or placebo. This dosage of L-carnosine was chosen because previously it had been tolerated and effective.

- The primary outcome measure was difference in Y-BOCS total scores. Secondary outcomes were differences in Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion subscale scores and differences in change in score on Y-BOCS total and subscale scores from baseline.

Outcomes

- The L-carnosine group experienced a significant decrease in Y-BOCS total score (P < .001), obsession subscale score (P < .01), and compulsion subscale score (P < .01).

- The group that received fluvoxamine plus L-carnosine also experienced a more complete response (P = .03).

- The L-carnosine group showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Conclusion

- L-carnosine significantly reduces OCD symptoms when used as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, et al. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(1):53-63.

3. Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley, R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):1011-1030.

4. Franklin ME, Foa EB. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:229-243.

5. Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7 Suppl):5-53.

6. Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(3):375-391.

7. Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, et al. Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(2):181-191.

8. Atmaca M. Treatment-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:127-133.

9. Barth M, Kriston L, Klostermann S, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse events: meta-regression and mediation analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(2):114-119.

10. NaderiS, Faghih H, Aqamolaei A, et al. Amantadine as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(4):169-174. doi:10.1111/pcn.12803

11. SharafkhahM, Aghakarim Alamdar M, MassoudifarA, et al. Comparing the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(5):222-233. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000267

12. ModarresiA, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(6):263-269. doi:10.1055/s-0043-12026

13. Shalbafan M, Malekpour F, Tadayon Najafabadi B, et al. Fluvoxamine combination therapy with tropisetron for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1407-1414. doi:10.1177/0269881119878177

14. Yousefzadeh F, Sahebolzamani E, Sadri A, et al. 5-Hydroxytryptophan as adjuvant therapy in treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(5):254-262. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000321

15. Mowla A, Ghaedsharaf M. Pregabalin augmentation for resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):552-556. doi:10.1017/S1092852919001500

16. Zheng H, Jia F, Han H, et al.Combined fluvoxamine and extended-release methylphenidate improved treatment response compared to fluvoxamine alone in patients with treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):397-404. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.12.010

17. Arabzadeh S, Shahhossenie M, Mesgarpour B, et al. L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine in treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(4). doi:10.1002/hup.2584

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, et al. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(1):53-63.

3. Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley, R, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):1011-1030.

4. Franklin ME, Foa EB. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:229-243.

5. Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7 Suppl):5-53.

6. Pittenger C, Bloch MH. Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(3):375-391.

7. Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, et al. Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(2):181-191.

8. Atmaca M. Treatment-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:127-133.

9. Barth M, Kriston L, Klostermann S, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse events: meta-regression and mediation analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(2):114-119.

10. NaderiS, Faghih H, Aqamolaei A, et al. Amantadine as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(4):169-174. doi:10.1111/pcn.12803

11. SharafkhahM, Aghakarim Alamdar M, MassoudifarA, et al. Comparing the efficacy of ondansetron and granisetron augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(5):222-233. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000267

12. ModarresiA, Sayyah M, Razooghi S, et al. Memantine augmentation improves symptoms in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51(6):263-269. doi:10.1055/s-0043-12026

13. Shalbafan M, Malekpour F, Tadayon Najafabadi B, et al. Fluvoxamine combination therapy with tropisetron for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1407-1414. doi:10.1177/0269881119878177

14. Yousefzadeh F, Sahebolzamani E, Sadri A, et al. 5-Hydroxytryptophan as adjuvant therapy in treatment of moderate to severe obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind randomized trial with placebo control. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(5):254-262. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000321

15. Mowla A, Ghaedsharaf M. Pregabalin augmentation for resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):552-556. doi:10.1017/S1092852919001500

16. Zheng H, Jia F, Han H, et al.Combined fluvoxamine and extended-release methylphenidate improved treatment response compared to fluvoxamine alone in patients with treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):397-404. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.12.010

17. Arabzadeh S, Shahhossenie M, Mesgarpour B, et al. L-carnosine as an adjuvant to fluvoxamine in treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomized double-blind study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(4). doi:10.1002/hup.2584

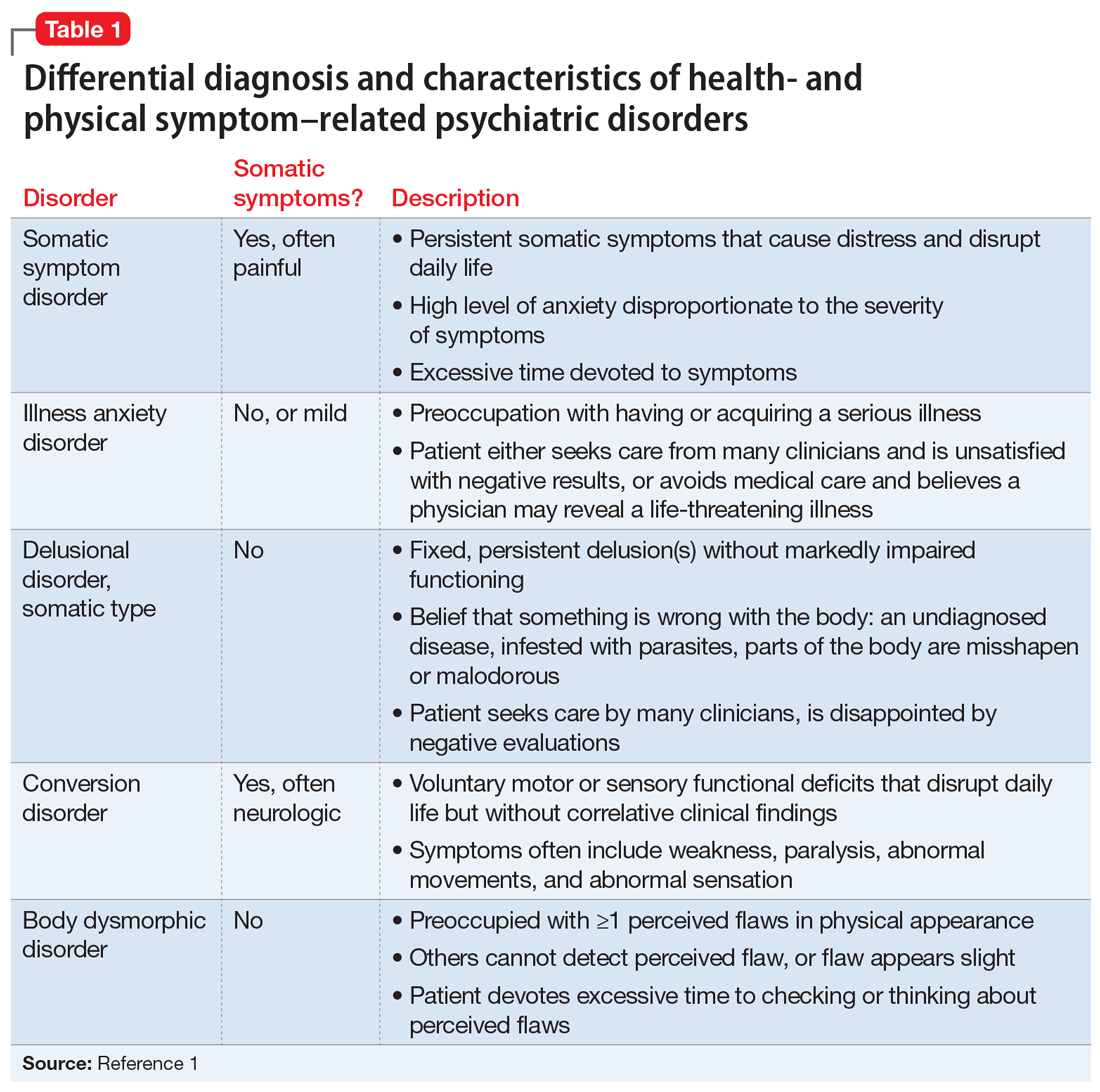

Food for thought: Dangerous weight loss in an older adult

CASE Fixated on health and nutrition

At the insistence of her daughter, Ms. L, age 75, presents to the emergency department (ED) for self-neglect and severe weight loss, with a body mass index (BMI) of 13.5 kg/m2 (normal: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). When asked why she is in the ED, Ms. L says she doesn’t know. She attributes her significant weight loss (approximately 20 pounds in the last few months) to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). She constantly worries about her esophagus. She had been diagnosed with esophageal dysphagia 7 years ago after undergoing radiofrequency ablation for esophageal cancer. Ms. L fixates on the negative effects certain foods and ingredients might have on her stomach and esophagus.