User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Schizophrenia and postmodernism: A philosophical exercise in treatment

Schizophrenia is defined as having episodes of psychosis: periods of time when one suffers from delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behaviors, disorganized speech, and negative symptoms. The concept of schizophrenia can be simplified as a detachment from reality. Patients who struggle with this illness frame their perceptions with a different set of rules and beliefs than the rest of society. These altered perceptions frequently become the basis of delusions, one of the most recognized symptoms of schizophrenia.

A patient with schizophrenia doesn’t have delusions, as much as having a belief system, which is not recognized by any other. It is not the mismatch between “objective reality” and the held belief, which qualifies the belief as delusional, so much as the mismatch with the beliefs of those around you. Heliocentrism denial, denying the knowledge that the earth rotates around the sun, is incorrect because it is not factual. However, heliocentrism denial is not a delusion because it is incorrect, but because society chooses it to be incorrect.

We’d like to invite the reader to a thought experiment. “Objective reality” can be referred to as “anything that exists as it is independent of any conscious awareness of it.”1 “Consciousness awareness” entails an observer. If we remove the concept of consciousness or observer from existence, how would we then define “objective reality,” as the very definition of “objective reality” points to the existence of an observer. One deduces that there is no way to define “objective reality” without invoking the notion of an observer or of consciousness.

It is our contention that the concept of an “objective reality” is tautological – it answers itself. This philosophical quandary helps explain why a person with schizophrenia may feel alienated by others who do not appreciate their perceived “objective reality.”

Schizophrenia and ‘objective reality’

A patient with schizophrenia enters a psychiatrist’s office and may realize that their belief is not shared by others and society. The schizophrenic patient may understand the concept of delusions as fixed and false beliefs. However, to them, it is everyone else who is delusional. They may attempt to convince you, as their provider, to switch to their side. They may provide you with evidence for their belief system. One could argue that believing them, in response, would be curative. If not only one’s psychiatrist, but society accepted the schizophrenic patient’s belief system, it would no longer be delusional, whether real or not. Objective reality requires the presence of an object, an observer, to grant its value of truth.

In a simplistic way, those were the arguments of postmodernist philosophers. Reality is tainted by its observer, in a similar way that the Heisenberg uncertainty principle teaches that there is a limit to our simultaneous understanding of position and momentum of particles. This perspective may explain why Michel Foucault, PhD, the famous French postmodernist philosopher, was so interested in psychiatry and in particular schizophrenia. Dr. Foucault was deeply concerned with society imposing its beliefs and value system on patients, and positioning itself as the ultimate arbiter of reality. He went on to postulate that the bigger difference between schizophrenic patients and psychiatrists was not who was in the correct plane of reality but who was granted by society to arbitrate the answer. If reality is a subjective construct enforced by a ruling class, who has the power to rule becomes of the utmost importance.

Intersubjectivity theory in psychoanalysis has many of its sensibilities rooted in such thought. It argues against the myth of the isolated mind. Truth, in the context of psychoanalysis, is seen as an emergent product of dialogue between the therapist/patient dyad. It is in line with the ontological shift from a logical-positivist model to the more modern, constructivist framework. In terms of its view of psychosis, “delusional ideas were understood as a form of absolution – a radical decontextualization serving vital and restorative defensive functions.”2

It is an interesting proposition to advance this theory further in contending that it is not the independent consciousness of two entities that create the intersubjective space; but rather that it is the intersubjective space that literally creates the conscious entities. Could it not be said that the subjective relationship is more fundamental than consciousness itself? As Chris Jaenicke, Dipl.-Psych., wrote, “infant research has opened our eyes to the fact that there is no unilateral action.”3

Postmodernism and psychiatry

Postmodernism and its precursor skepticism have significant histories within the field of philosophy. This article will not summarize centuries of philosophical thought. In brief, skepticism is a powerful philosophical tool that can powerfully point out the limitations of human knowledge and certainty.

As a pedagogic jest to trainees, we will often point out that none of us “really knows” our date of birth with absolute certainty. None of us were conscious enough to remember our birth, conscious enough to understand the concept of date or time, and conscious enough to know who participated in it. At a fundamental level, we chose to believe our date of birth. Similarly, while the world could be a fictionalized simulation,4 we chose to believe that it is real because it behaves in a consistent way that permits scientific study. Postmodernism and skepticism are philosophical tools that permit one to question everything but are themselves limited by the real and empiric lives we live.

Psychiatrists are empiricists. We treat real people, who suffer in a very perceptible way, and live in a very tangible world. We frown on the postmodernist perspective and do not spend much or any time studying it as trainees. However, postmodernism, despite its philosophical and practical flaws, and adjacency to antipsychiatry,5 is an essential tool for the psychiatrist. In addition to the standard treatments for schizophrenia, the psychiatrist should attempt to create a bond with someone who is disconnected from the world. Postmodernism provides us with a way of doing so.

A psychiatrist who understands and appreciates postmodernism can show a patient why at some level we cannot refute all delusions. This psychiatrist can subsequently have empathy that some of the core beliefs of a patient may always be left unanswered. The psychiatrist can appreciate that to some degree the reason why the patient’s beliefs are not true is because society has chosen for them not to be true. Additionally, the psychiatrist can acknowledge to the patient that in some ways the correctness of a delusion is less relevant than the power of society to enforce its reality on the patient. This connection in itself is partially curative as it restores the patient’s attachment to society; we now have some plane of reality, the relationship, which is the same.

Psychiatry and philosophy

However, tempting it may be to be satisfied with this approach as an end in itself; this would be dangerous. While gratifying to the patient to be seen and heard, they will over time only become further entrenched in that compromise formation of delusional beliefs. The role of the psychiatrist, once deep and meaningful rapport has been established and solidified, is to point out to the patient the limitations of the delusions’ belief system.

“I empathize that not all your delusions can be disproved. An extension of that thought is that many beliefs can’t be disproved. Society chooses to believe that aliens do not live on earth but at the same time we can’t disprove with absolute certainty that they don’t. We live in a world where attachment to others enriches our lives. If you continue to believe that aliens affect all existence around you, you will disconnect yourself from all of us. I hope that our therapy has shown you the importance of human connection and the sacrifice of your belief system.”

In the modern day, psychiatry has chosen to believe that schizophrenia is a biological disorder that requires treatment with antipsychotics. We choose to believe that this is likely true, and we think that our empirical experience has been consistent with this belief. However, we also think that patients with this illness are salient beings that deserve to have their thoughts examined and addressed in a therapeutic framework that seeks to understand and acknowledge them as worthy and intelligent individuals. Philosophy provides psychiatry with tools on how to do so.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. https://iep.utm.edu/objectiv/.

2. Stolorow, RD. The phenomenology of trauma and the absolutisms of everyday life: A personal journey. Psychoanal Psychol. 1999;16(3):464-8. doi: 10.1037/0736-9735.16.3.464.

3. Jaenicke C. “The Risk of Relatedness: Intersubjectivity Theory in Clinical Practice” Lanham, Md.: Jason Aronson, 2007.

4. Cuthbertson A. “Elon Musk cites Pong as evidence that we are already living in a simulation” The Independent. 2021 Dec 1. https://www.independent.co.uk/space/elon-musk-simulation-pong-video-game-b1972369.html.

5. Foucault M (Howard R, translator). “Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason” New York: Vintage, 1965.

Schizophrenia is defined as having episodes of psychosis: periods of time when one suffers from delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behaviors, disorganized speech, and negative symptoms. The concept of schizophrenia can be simplified as a detachment from reality. Patients who struggle with this illness frame their perceptions with a different set of rules and beliefs than the rest of society. These altered perceptions frequently become the basis of delusions, one of the most recognized symptoms of schizophrenia.

A patient with schizophrenia doesn’t have delusions, as much as having a belief system, which is not recognized by any other. It is not the mismatch between “objective reality” and the held belief, which qualifies the belief as delusional, so much as the mismatch with the beliefs of those around you. Heliocentrism denial, denying the knowledge that the earth rotates around the sun, is incorrect because it is not factual. However, heliocentrism denial is not a delusion because it is incorrect, but because society chooses it to be incorrect.

We’d like to invite the reader to a thought experiment. “Objective reality” can be referred to as “anything that exists as it is independent of any conscious awareness of it.”1 “Consciousness awareness” entails an observer. If we remove the concept of consciousness or observer from existence, how would we then define “objective reality,” as the very definition of “objective reality” points to the existence of an observer. One deduces that there is no way to define “objective reality” without invoking the notion of an observer or of consciousness.

It is our contention that the concept of an “objective reality” is tautological – it answers itself. This philosophical quandary helps explain why a person with schizophrenia may feel alienated by others who do not appreciate their perceived “objective reality.”

Schizophrenia and ‘objective reality’

A patient with schizophrenia enters a psychiatrist’s office and may realize that their belief is not shared by others and society. The schizophrenic patient may understand the concept of delusions as fixed and false beliefs. However, to them, it is everyone else who is delusional. They may attempt to convince you, as their provider, to switch to their side. They may provide you with evidence for their belief system. One could argue that believing them, in response, would be curative. If not only one’s psychiatrist, but society accepted the schizophrenic patient’s belief system, it would no longer be delusional, whether real or not. Objective reality requires the presence of an object, an observer, to grant its value of truth.

In a simplistic way, those were the arguments of postmodernist philosophers. Reality is tainted by its observer, in a similar way that the Heisenberg uncertainty principle teaches that there is a limit to our simultaneous understanding of position and momentum of particles. This perspective may explain why Michel Foucault, PhD, the famous French postmodernist philosopher, was so interested in psychiatry and in particular schizophrenia. Dr. Foucault was deeply concerned with society imposing its beliefs and value system on patients, and positioning itself as the ultimate arbiter of reality. He went on to postulate that the bigger difference between schizophrenic patients and psychiatrists was not who was in the correct plane of reality but who was granted by society to arbitrate the answer. If reality is a subjective construct enforced by a ruling class, who has the power to rule becomes of the utmost importance.

Intersubjectivity theory in psychoanalysis has many of its sensibilities rooted in such thought. It argues against the myth of the isolated mind. Truth, in the context of psychoanalysis, is seen as an emergent product of dialogue between the therapist/patient dyad. It is in line with the ontological shift from a logical-positivist model to the more modern, constructivist framework. In terms of its view of psychosis, “delusional ideas were understood as a form of absolution – a radical decontextualization serving vital and restorative defensive functions.”2

It is an interesting proposition to advance this theory further in contending that it is not the independent consciousness of two entities that create the intersubjective space; but rather that it is the intersubjective space that literally creates the conscious entities. Could it not be said that the subjective relationship is more fundamental than consciousness itself? As Chris Jaenicke, Dipl.-Psych., wrote, “infant research has opened our eyes to the fact that there is no unilateral action.”3

Postmodernism and psychiatry

Postmodernism and its precursor skepticism have significant histories within the field of philosophy. This article will not summarize centuries of philosophical thought. In brief, skepticism is a powerful philosophical tool that can powerfully point out the limitations of human knowledge and certainty.

As a pedagogic jest to trainees, we will often point out that none of us “really knows” our date of birth with absolute certainty. None of us were conscious enough to remember our birth, conscious enough to understand the concept of date or time, and conscious enough to know who participated in it. At a fundamental level, we chose to believe our date of birth. Similarly, while the world could be a fictionalized simulation,4 we chose to believe that it is real because it behaves in a consistent way that permits scientific study. Postmodernism and skepticism are philosophical tools that permit one to question everything but are themselves limited by the real and empiric lives we live.

Psychiatrists are empiricists. We treat real people, who suffer in a very perceptible way, and live in a very tangible world. We frown on the postmodernist perspective and do not spend much or any time studying it as trainees. However, postmodernism, despite its philosophical and practical flaws, and adjacency to antipsychiatry,5 is an essential tool for the psychiatrist. In addition to the standard treatments for schizophrenia, the psychiatrist should attempt to create a bond with someone who is disconnected from the world. Postmodernism provides us with a way of doing so.

A psychiatrist who understands and appreciates postmodernism can show a patient why at some level we cannot refute all delusions. This psychiatrist can subsequently have empathy that some of the core beliefs of a patient may always be left unanswered. The psychiatrist can appreciate that to some degree the reason why the patient’s beliefs are not true is because society has chosen for them not to be true. Additionally, the psychiatrist can acknowledge to the patient that in some ways the correctness of a delusion is less relevant than the power of society to enforce its reality on the patient. This connection in itself is partially curative as it restores the patient’s attachment to society; we now have some plane of reality, the relationship, which is the same.

Psychiatry and philosophy

However, tempting it may be to be satisfied with this approach as an end in itself; this would be dangerous. While gratifying to the patient to be seen and heard, they will over time only become further entrenched in that compromise formation of delusional beliefs. The role of the psychiatrist, once deep and meaningful rapport has been established and solidified, is to point out to the patient the limitations of the delusions’ belief system.

“I empathize that not all your delusions can be disproved. An extension of that thought is that many beliefs can’t be disproved. Society chooses to believe that aliens do not live on earth but at the same time we can’t disprove with absolute certainty that they don’t. We live in a world where attachment to others enriches our lives. If you continue to believe that aliens affect all existence around you, you will disconnect yourself from all of us. I hope that our therapy has shown you the importance of human connection and the sacrifice of your belief system.”

In the modern day, psychiatry has chosen to believe that schizophrenia is a biological disorder that requires treatment with antipsychotics. We choose to believe that this is likely true, and we think that our empirical experience has been consistent with this belief. However, we also think that patients with this illness are salient beings that deserve to have their thoughts examined and addressed in a therapeutic framework that seeks to understand and acknowledge them as worthy and intelligent individuals. Philosophy provides psychiatry with tools on how to do so.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. https://iep.utm.edu/objectiv/.

2. Stolorow, RD. The phenomenology of trauma and the absolutisms of everyday life: A personal journey. Psychoanal Psychol. 1999;16(3):464-8. doi: 10.1037/0736-9735.16.3.464.

3. Jaenicke C. “The Risk of Relatedness: Intersubjectivity Theory in Clinical Practice” Lanham, Md.: Jason Aronson, 2007.

4. Cuthbertson A. “Elon Musk cites Pong as evidence that we are already living in a simulation” The Independent. 2021 Dec 1. https://www.independent.co.uk/space/elon-musk-simulation-pong-video-game-b1972369.html.

5. Foucault M (Howard R, translator). “Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason” New York: Vintage, 1965.

Schizophrenia is defined as having episodes of psychosis: periods of time when one suffers from delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behaviors, disorganized speech, and negative symptoms. The concept of schizophrenia can be simplified as a detachment from reality. Patients who struggle with this illness frame their perceptions with a different set of rules and beliefs than the rest of society. These altered perceptions frequently become the basis of delusions, one of the most recognized symptoms of schizophrenia.

A patient with schizophrenia doesn’t have delusions, as much as having a belief system, which is not recognized by any other. It is not the mismatch between “objective reality” and the held belief, which qualifies the belief as delusional, so much as the mismatch with the beliefs of those around you. Heliocentrism denial, denying the knowledge that the earth rotates around the sun, is incorrect because it is not factual. However, heliocentrism denial is not a delusion because it is incorrect, but because society chooses it to be incorrect.

We’d like to invite the reader to a thought experiment. “Objective reality” can be referred to as “anything that exists as it is independent of any conscious awareness of it.”1 “Consciousness awareness” entails an observer. If we remove the concept of consciousness or observer from existence, how would we then define “objective reality,” as the very definition of “objective reality” points to the existence of an observer. One deduces that there is no way to define “objective reality” without invoking the notion of an observer or of consciousness.

It is our contention that the concept of an “objective reality” is tautological – it answers itself. This philosophical quandary helps explain why a person with schizophrenia may feel alienated by others who do not appreciate their perceived “objective reality.”

Schizophrenia and ‘objective reality’

A patient with schizophrenia enters a psychiatrist’s office and may realize that their belief is not shared by others and society. The schizophrenic patient may understand the concept of delusions as fixed and false beliefs. However, to them, it is everyone else who is delusional. They may attempt to convince you, as their provider, to switch to their side. They may provide you with evidence for their belief system. One could argue that believing them, in response, would be curative. If not only one’s psychiatrist, but society accepted the schizophrenic patient’s belief system, it would no longer be delusional, whether real or not. Objective reality requires the presence of an object, an observer, to grant its value of truth.

In a simplistic way, those were the arguments of postmodernist philosophers. Reality is tainted by its observer, in a similar way that the Heisenberg uncertainty principle teaches that there is a limit to our simultaneous understanding of position and momentum of particles. This perspective may explain why Michel Foucault, PhD, the famous French postmodernist philosopher, was so interested in psychiatry and in particular schizophrenia. Dr. Foucault was deeply concerned with society imposing its beliefs and value system on patients, and positioning itself as the ultimate arbiter of reality. He went on to postulate that the bigger difference between schizophrenic patients and psychiatrists was not who was in the correct plane of reality but who was granted by society to arbitrate the answer. If reality is a subjective construct enforced by a ruling class, who has the power to rule becomes of the utmost importance.

Intersubjectivity theory in psychoanalysis has many of its sensibilities rooted in such thought. It argues against the myth of the isolated mind. Truth, in the context of psychoanalysis, is seen as an emergent product of dialogue between the therapist/patient dyad. It is in line with the ontological shift from a logical-positivist model to the more modern, constructivist framework. In terms of its view of psychosis, “delusional ideas were understood as a form of absolution – a radical decontextualization serving vital and restorative defensive functions.”2

It is an interesting proposition to advance this theory further in contending that it is not the independent consciousness of two entities that create the intersubjective space; but rather that it is the intersubjective space that literally creates the conscious entities. Could it not be said that the subjective relationship is more fundamental than consciousness itself? As Chris Jaenicke, Dipl.-Psych., wrote, “infant research has opened our eyes to the fact that there is no unilateral action.”3

Postmodernism and psychiatry

Postmodernism and its precursor skepticism have significant histories within the field of philosophy. This article will not summarize centuries of philosophical thought. In brief, skepticism is a powerful philosophical tool that can powerfully point out the limitations of human knowledge and certainty.

As a pedagogic jest to trainees, we will often point out that none of us “really knows” our date of birth with absolute certainty. None of us were conscious enough to remember our birth, conscious enough to understand the concept of date or time, and conscious enough to know who participated in it. At a fundamental level, we chose to believe our date of birth. Similarly, while the world could be a fictionalized simulation,4 we chose to believe that it is real because it behaves in a consistent way that permits scientific study. Postmodernism and skepticism are philosophical tools that permit one to question everything but are themselves limited by the real and empiric lives we live.

Psychiatrists are empiricists. We treat real people, who suffer in a very perceptible way, and live in a very tangible world. We frown on the postmodernist perspective and do not spend much or any time studying it as trainees. However, postmodernism, despite its philosophical and practical flaws, and adjacency to antipsychiatry,5 is an essential tool for the psychiatrist. In addition to the standard treatments for schizophrenia, the psychiatrist should attempt to create a bond with someone who is disconnected from the world. Postmodernism provides us with a way of doing so.

A psychiatrist who understands and appreciates postmodernism can show a patient why at some level we cannot refute all delusions. This psychiatrist can subsequently have empathy that some of the core beliefs of a patient may always be left unanswered. The psychiatrist can appreciate that to some degree the reason why the patient’s beliefs are not true is because society has chosen for them not to be true. Additionally, the psychiatrist can acknowledge to the patient that in some ways the correctness of a delusion is less relevant than the power of society to enforce its reality on the patient. This connection in itself is partially curative as it restores the patient’s attachment to society; we now have some plane of reality, the relationship, which is the same.

Psychiatry and philosophy

However, tempting it may be to be satisfied with this approach as an end in itself; this would be dangerous. While gratifying to the patient to be seen and heard, they will over time only become further entrenched in that compromise formation of delusional beliefs. The role of the psychiatrist, once deep and meaningful rapport has been established and solidified, is to point out to the patient the limitations of the delusions’ belief system.

“I empathize that not all your delusions can be disproved. An extension of that thought is that many beliefs can’t be disproved. Society chooses to believe that aliens do not live on earth but at the same time we can’t disprove with absolute certainty that they don’t. We live in a world where attachment to others enriches our lives. If you continue to believe that aliens affect all existence around you, you will disconnect yourself from all of us. I hope that our therapy has shown you the importance of human connection and the sacrifice of your belief system.”

In the modern day, psychiatry has chosen to believe that schizophrenia is a biological disorder that requires treatment with antipsychotics. We choose to believe that this is likely true, and we think that our empirical experience has been consistent with this belief. However, we also think that patients with this illness are salient beings that deserve to have their thoughts examined and addressed in a therapeutic framework that seeks to understand and acknowledge them as worthy and intelligent individuals. Philosophy provides psychiatry with tools on how to do so.

Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. https://iep.utm.edu/objectiv/.

2. Stolorow, RD. The phenomenology of trauma and the absolutisms of everyday life: A personal journey. Psychoanal Psychol. 1999;16(3):464-8. doi: 10.1037/0736-9735.16.3.464.

3. Jaenicke C. “The Risk of Relatedness: Intersubjectivity Theory in Clinical Practice” Lanham, Md.: Jason Aronson, 2007.

4. Cuthbertson A. “Elon Musk cites Pong as evidence that we are already living in a simulation” The Independent. 2021 Dec 1. https://www.independent.co.uk/space/elon-musk-simulation-pong-video-game-b1972369.html.

5. Foucault M (Howard R, translator). “Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason” New York: Vintage, 1965.

‘Dr. Caveman’ had a leg up on amputation

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

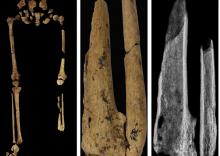

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

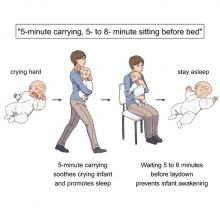

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Ketamine promising for rare condition linked to autism

Also known as Helsmoortel–Van Der Aa syndrome, ADNP syndrome is caused by mutations in the ADNP gene. Studies in animal models suggest that low-dose ketamine increases expression of ADNP and is neuroprotective.

Intrigued by the preclinical evidence, Alexander Kolevzon, MD, clinical director of the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai, New York, and colleagues treated 10 children with ADNP syndrome with a single low dose of ketamine (0.5mg/kg) infused intravenously over 40 minutes. The children ranged in ages 6-12 years.

Using parent-report instruments to assess treatment effects, ketamine was associated with “nominally significant” improvement in a variety of domains, including social behavior, attention-deficit and hyperactivity, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and sensory sensitivities.

Parent reports of improvement in these domains aligned with clinician-rated assessments based on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale.

The results also highlight the potential utility of electrophysiological measurement of auditory steady-state response and eye-tracking to track change with ketamine treatment, the researchers say.

The study was published online in Human Genetics and Genomic (HGG) Advances.

Hypothesis-generating

Ketamine was generally well tolerated. There were no clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory or cardiac monitoring, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs).

Treatment emergent AEs were all mild to moderate and no child required any interventions.

The most common AEs were elation/silliness in five children (50%), all of whom had a history of similar symptoms. Drowsiness and fatigue occurred in four children (40%) and two of them had a history of drowsiness. Aggression was likewise relatively common, reported in four children (40%), all of whom had aggression at baseline.

Decreased appetite emerged as a new AE in three children (30%), increased anxiety occurred in three children (30%), and irritability, nausea/vomiting, and restlessness each occurred in two children (20%).

The researchers caution that the findings are intended to be “hypothesis generating.”

“We are encouraged by these findings, which provide preliminary support for ketamine to help reduce negative effects of this devastating syndrome,” Dr. Kolevzon said in a news release from Mount Sinai.

Ketamine might help ease symptoms of ADNP syndrome “by increasing expression of the ADNP gene or by promoting synaptic plasticity through glutamatergic pathways,” Dr. Kolevzon told this news organization.

The next step, he said, is to get “a larger, placebo-controlled study approved for funding using repeated dosing over a longer duration of time. We are working with the FDA to get the design approved for an investigational new drug application.”

Support for the study was provided by the ADNP Kids Foundation and the Foundation for Mood Disorders. Support for mediKanren was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and National Institutes of Health through the Biomedical Data Translator Program. Dr. Kolevzon is on the scientific advisory board of Ovid Therapeutics, Ritrova Therapeutics, and Jaguar Therapeutics and consults to Acadia, Alkermes, GW Pharmaceuticals, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, Clinilabs Drug Development Corporation, and Scioto Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Also known as Helsmoortel–Van Der Aa syndrome, ADNP syndrome is caused by mutations in the ADNP gene. Studies in animal models suggest that low-dose ketamine increases expression of ADNP and is neuroprotective.

Intrigued by the preclinical evidence, Alexander Kolevzon, MD, clinical director of the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai, New York, and colleagues treated 10 children with ADNP syndrome with a single low dose of ketamine (0.5mg/kg) infused intravenously over 40 minutes. The children ranged in ages 6-12 years.

Using parent-report instruments to assess treatment effects, ketamine was associated with “nominally significant” improvement in a variety of domains, including social behavior, attention-deficit and hyperactivity, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and sensory sensitivities.

Parent reports of improvement in these domains aligned with clinician-rated assessments based on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale.

The results also highlight the potential utility of electrophysiological measurement of auditory steady-state response and eye-tracking to track change with ketamine treatment, the researchers say.

The study was published online in Human Genetics and Genomic (HGG) Advances.

Hypothesis-generating

Ketamine was generally well tolerated. There were no clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory or cardiac monitoring, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs).

Treatment emergent AEs were all mild to moderate and no child required any interventions.

The most common AEs were elation/silliness in five children (50%), all of whom had a history of similar symptoms. Drowsiness and fatigue occurred in four children (40%) and two of them had a history of drowsiness. Aggression was likewise relatively common, reported in four children (40%), all of whom had aggression at baseline.

Decreased appetite emerged as a new AE in three children (30%), increased anxiety occurred in three children (30%), and irritability, nausea/vomiting, and restlessness each occurred in two children (20%).

The researchers caution that the findings are intended to be “hypothesis generating.”

“We are encouraged by these findings, which provide preliminary support for ketamine to help reduce negative effects of this devastating syndrome,” Dr. Kolevzon said in a news release from Mount Sinai.

Ketamine might help ease symptoms of ADNP syndrome “by increasing expression of the ADNP gene or by promoting synaptic plasticity through glutamatergic pathways,” Dr. Kolevzon told this news organization.

The next step, he said, is to get “a larger, placebo-controlled study approved for funding using repeated dosing over a longer duration of time. We are working with the FDA to get the design approved for an investigational new drug application.”

Support for the study was provided by the ADNP Kids Foundation and the Foundation for Mood Disorders. Support for mediKanren was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and National Institutes of Health through the Biomedical Data Translator Program. Dr. Kolevzon is on the scientific advisory board of Ovid Therapeutics, Ritrova Therapeutics, and Jaguar Therapeutics and consults to Acadia, Alkermes, GW Pharmaceuticals, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, Clinilabs Drug Development Corporation, and Scioto Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Also known as Helsmoortel–Van Der Aa syndrome, ADNP syndrome is caused by mutations in the ADNP gene. Studies in animal models suggest that low-dose ketamine increases expression of ADNP and is neuroprotective.

Intrigued by the preclinical evidence, Alexander Kolevzon, MD, clinical director of the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai, New York, and colleagues treated 10 children with ADNP syndrome with a single low dose of ketamine (0.5mg/kg) infused intravenously over 40 minutes. The children ranged in ages 6-12 years.

Using parent-report instruments to assess treatment effects, ketamine was associated with “nominally significant” improvement in a variety of domains, including social behavior, attention-deficit and hyperactivity, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and sensory sensitivities.

Parent reports of improvement in these domains aligned with clinician-rated assessments based on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale.

The results also highlight the potential utility of electrophysiological measurement of auditory steady-state response and eye-tracking to track change with ketamine treatment, the researchers say.

The study was published online in Human Genetics and Genomic (HGG) Advances.

Hypothesis-generating

Ketamine was generally well tolerated. There were no clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory or cardiac monitoring, and there were no serious adverse events (AEs).

Treatment emergent AEs were all mild to moderate and no child required any interventions.

The most common AEs were elation/silliness in five children (50%), all of whom had a history of similar symptoms. Drowsiness and fatigue occurred in four children (40%) and two of them had a history of drowsiness. Aggression was likewise relatively common, reported in four children (40%), all of whom had aggression at baseline.

Decreased appetite emerged as a new AE in three children (30%), increased anxiety occurred in three children (30%), and irritability, nausea/vomiting, and restlessness each occurred in two children (20%).

The researchers caution that the findings are intended to be “hypothesis generating.”

“We are encouraged by these findings, which provide preliminary support for ketamine to help reduce negative effects of this devastating syndrome,” Dr. Kolevzon said in a news release from Mount Sinai.

Ketamine might help ease symptoms of ADNP syndrome “by increasing expression of the ADNP gene or by promoting synaptic plasticity through glutamatergic pathways,” Dr. Kolevzon told this news organization.

The next step, he said, is to get “a larger, placebo-controlled study approved for funding using repeated dosing over a longer duration of time. We are working with the FDA to get the design approved for an investigational new drug application.”

Support for the study was provided by the ADNP Kids Foundation and the Foundation for Mood Disorders. Support for mediKanren was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and National Institutes of Health through the Biomedical Data Translator Program. Dr. Kolevzon is on the scientific advisory board of Ovid Therapeutics, Ritrova Therapeutics, and Jaguar Therapeutics and consults to Acadia, Alkermes, GW Pharmaceuticals, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, Clinilabs Drug Development Corporation, and Scioto Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From Human Genetics and Genomic Advances

Clozapine may be best choice for cutting SUD risk in schizophrenia

results of a real-world study show.

“Our findings are in line with a recent meta-analysis showing superior efficacy of clozapine in schizophrenia and comorbid SUD and other studies pointing toward clozapine’s superiority over other antipsychotics in the treatment of individuals with schizophrenia and comorbid SUD,” the investigators, led by Jari Tiihonen MD, PhD, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, write.

“The results on polypharmacy are in line with previous results from nationwide cohorts showing a favorable outcome, compared with oral monotherapies among persons with schizophrenia in general,” they add.

The study was published online Aug. 25 in The British Journal of Psychiatry.

Research gap

Research on the effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for schizophrenia and comorbid SUD is “very sparse, and more importantly, non-existent on the prevention of the development of SUDs in patients with schizophrenia,” the researchers note.

To investigate, they analyzed data on more than 45,000 patients with schizophrenia from Finnish and Swedish national registries, with follow-up lasting 22 years in Finland and 11 years in Sweden.

In patients with schizophrenia without SUD, treatment with clozapine was associated with lowest risk for an initial SUD in both Finland (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.16-0.24) and Sweden (aHR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.24-0.50), compared with no use or use of other antipsychotics.

In Finland, aripiprazole was associated with the second lowest risk for an initial SUD (aHR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24-0.55) and antipsychotic polytherapy the third lowest risk (aHR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.42-0.53).

In Sweden, antipsychotic polytherapy was associated with second lowest risk for an initial SUD (aHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.66) and olanzapine the third lowest risk (aHR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.53-0.84).

In both countries, the risk for relapse as indicated by psychiatric hospital admission and SUD-related hospital admission were lowest for clozapine, antipsychotic polytherapy and long-acting injectables, the investigators report.

Interpret with caution

Reached for comment, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York, urged caution in interpreting the results.

“While the authors are experts in national database analyses and the study was conducted with state-of-the-art methodology, the onset of SUD analyses favoring clozapine are subject to survival bias and order effects,” Dr. Correll said.

“Since clozapine is generally used later in the illness and treatment course, after multiple other antipsychotics have been used, and since SUDs generally occur early in the illness course, most SUDs will already have arisen by the time that clozapine is considered and used,” Dr. Correll said.

“A similar potential bias exists for long-acting injectables (LAIs), as these have generally also been used late in the treatment algorithm,” he noted.

In terms of the significant reduction of SUD-related hospitalizations observed with clozapine, the “order effect” could also be relevant, Dr. Correll said, because over time, patients are less likely to be nonadherent and hospitalized and clozapine is systematically used later in life than other antipsychotics.

“Why antipsychotic polytherapy came out as the second-best treatment is much less clear. Clearly head-to-head randomized trials are needed to follow up on these interesting and intriguing naturalistic database study data,” said Dr. Correll.

This study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital. Dr. Tiihonen and three co-authors have participated in research projects funded by grants from Janssen-Cilag and Eli Lilly to their institution. Dr. Correll reports having been a consultant and/or advisor to or receiving honoraria from many companies. He has also provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka; served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva; received royalties from UpToDate; and is a stock option holder of Cardio Diagnostics, Mindpax, LB Pharma, and Quantic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

results of a real-world study show.

“Our findings are in line with a recent meta-analysis showing superior efficacy of clozapine in schizophrenia and comorbid SUD and other studies pointing toward clozapine’s superiority over other antipsychotics in the treatment of individuals with schizophrenia and comorbid SUD,” the investigators, led by Jari Tiihonen MD, PhD, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, write.

“The results on polypharmacy are in line with previous results from nationwide cohorts showing a favorable outcome, compared with oral monotherapies among persons with schizophrenia in general,” they add.

The study was published online Aug. 25 in The British Journal of Psychiatry.

Research gap

Research on the effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for schizophrenia and comorbid SUD is “very sparse, and more importantly, non-existent on the prevention of the development of SUDs in patients with schizophrenia,” the researchers note.

To investigate, they analyzed data on more than 45,000 patients with schizophrenia from Finnish and Swedish national registries, with follow-up lasting 22 years in Finland and 11 years in Sweden.

In patients with schizophrenia without SUD, treatment with clozapine was associated with lowest risk for an initial SUD in both Finland (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.16-0.24) and Sweden (aHR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.24-0.50), compared with no use or use of other antipsychotics.

In Finland, aripiprazole was associated with the second lowest risk for an initial SUD (aHR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24-0.55) and antipsychotic polytherapy the third lowest risk (aHR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.42-0.53).

In Sweden, antipsychotic polytherapy was associated with second lowest risk for an initial SUD (aHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.66) and olanzapine the third lowest risk (aHR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.53-0.84).

In both countries, the risk for relapse as indicated by psychiatric hospital admission and SUD-related hospital admission were lowest for clozapine, antipsychotic polytherapy and long-acting injectables, the investigators report.

Interpret with caution

Reached for comment, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York, urged caution in interpreting the results.

“While the authors are experts in national database analyses and the study was conducted with state-of-the-art methodology, the onset of SUD analyses favoring clozapine are subject to survival bias and order effects,” Dr. Correll said.

“Since clozapine is generally used later in the illness and treatment course, after multiple other antipsychotics have been used, and since SUDs generally occur early in the illness course, most SUDs will already have arisen by the time that clozapine is considered and used,” Dr. Correll said.

“A similar potential bias exists for long-acting injectables (LAIs), as these have generally also been used late in the treatment algorithm,” he noted.

In terms of the significant reduction of SUD-related hospitalizations observed with clozapine, the “order effect” could also be relevant, Dr. Correll said, because over time, patients are less likely to be nonadherent and hospitalized and clozapine is systematically used later in life than other antipsychotics.

“Why antipsychotic polytherapy came out as the second-best treatment is much less clear. Clearly head-to-head randomized trials are needed to follow up on these interesting and intriguing naturalistic database study data,” said Dr. Correll.

This study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital. Dr. Tiihonen and three co-authors have participated in research projects funded by grants from Janssen-Cilag and Eli Lilly to their institution. Dr. Correll reports having been a consultant and/or advisor to or receiving honoraria from many companies. He has also provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka; served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva; received royalties from UpToDate; and is a stock option holder of Cardio Diagnostics, Mindpax, LB Pharma, and Quantic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

results of a real-world study show.

“Our findings are in line with a recent meta-analysis showing superior efficacy of clozapine in schizophrenia and comorbid SUD and other studies pointing toward clozapine’s superiority over other antipsychotics in the treatment of individuals with schizophrenia and comorbid SUD,” the investigators, led by Jari Tiihonen MD, PhD, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, write.

“The results on polypharmacy are in line with previous results from nationwide cohorts showing a favorable outcome, compared with oral monotherapies among persons with schizophrenia in general,” they add.

The study was published online Aug. 25 in The British Journal of Psychiatry.

Research gap

Research on the effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for schizophrenia and comorbid SUD is “very sparse, and more importantly, non-existent on the prevention of the development of SUDs in patients with schizophrenia,” the researchers note.

To investigate, they analyzed data on more than 45,000 patients with schizophrenia from Finnish and Swedish national registries, with follow-up lasting 22 years in Finland and 11 years in Sweden.

In patients with schizophrenia without SUD, treatment with clozapine was associated with lowest risk for an initial SUD in both Finland (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.16-0.24) and Sweden (aHR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.24-0.50), compared with no use or use of other antipsychotics.

In Finland, aripiprazole was associated with the second lowest risk for an initial SUD (aHR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24-0.55) and antipsychotic polytherapy the third lowest risk (aHR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.42-0.53).

In Sweden, antipsychotic polytherapy was associated with second lowest risk for an initial SUD (aHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44-0.66) and olanzapine the third lowest risk (aHR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.53-0.84).

In both countries, the risk for relapse as indicated by psychiatric hospital admission and SUD-related hospital admission were lowest for clozapine, antipsychotic polytherapy and long-acting injectables, the investigators report.

Interpret with caution

Reached for comment, Christoph U. Correll, MD, professor of psychiatry and molecular medicine, the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York, urged caution in interpreting the results.

“While the authors are experts in national database analyses and the study was conducted with state-of-the-art methodology, the onset of SUD analyses favoring clozapine are subject to survival bias and order effects,” Dr. Correll said.

“Since clozapine is generally used later in the illness and treatment course, after multiple other antipsychotics have been used, and since SUDs generally occur early in the illness course, most SUDs will already have arisen by the time that clozapine is considered and used,” Dr. Correll said.

“A similar potential bias exists for long-acting injectables (LAIs), as these have generally also been used late in the treatment algorithm,” he noted.

In terms of the significant reduction of SUD-related hospitalizations observed with clozapine, the “order effect” could also be relevant, Dr. Correll said, because over time, patients are less likely to be nonadherent and hospitalized and clozapine is systematically used later in life than other antipsychotics.

“Why antipsychotic polytherapy came out as the second-best treatment is much less clear. Clearly head-to-head randomized trials are needed to follow up on these interesting and intriguing naturalistic database study data,” said Dr. Correll.

This study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital. Dr. Tiihonen and three co-authors have participated in research projects funded by grants from Janssen-Cilag and Eli Lilly to their institution. Dr. Correll reports having been a consultant and/or advisor to or receiving honoraria from many companies. He has also provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka; served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva; received royalties from UpToDate; and is a stock option holder of Cardio Diagnostics, Mindpax, LB Pharma, and Quantic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

Psychedelics may ease fear of death and dying

Psychedelics can produce positive changes in attitudes about death and dying – and may be a way to help ease anxiety and depression toward the end of life, new research suggests.

In a retrospective study of more than 3,000 participants,

“Individuals with existential anxiety and depression at end of life account for substantial suffering and significantly increased health care expenses from desperate and often futile seeking of intensive and expensive medical treatments,” co-investigator Roland Griffiths, PhD, Center for Psychedelics and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“The present findings, which show that both psychedelic and non–drug-occasioned experiences can produce positive and enduring changes in attitudes about death, suggest the importance of future prospective experimental and clinical observational studies to better understand mechanisms of such changes as well as their potential clinical utility in ameliorating suffering related to fear of death,” Dr. Griffiths said.

The results were published online Aug. 24 in PLOS ONE.

Direct comparisons

Both psychedelic drug experiences and near-death experiences can alter perspectives on death and dying, but there have been few direct comparisons of these phenomena, the investigators note.

In the current study, they directly compared psychedelic-occasioned and nondrug experiences, which altered individuals’ beliefs about death.

The researchers surveyed 3,192 mostly White adults from the United States, including 933 who had a natural, nondrug near-death experience and 2,259 who had psychedelic near-death experiences induced with lysergic acid diethylamide, psilocybin, ayahuasca, or N,N-dimethyltryptamine.

The psychedelic group had more men than women and tended to be younger at the time of the experience than was the nondrug group.

Nearly 90% of individuals in both groups said that they were less afraid of death than they were before their experiences.

About half of both groups said they’d encountered something they might call “God” during the experience.

Three-quarters of the psychedelic group and 85% of the nondrug group rated their experiences as among the top five most personally meaningful and spiritually significant events of their life.