User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

What are your treatment options when isotretinoin fails?

INDIANAPOLIS – – which is known to increase the drug’s bioavailability, advises James R. Treat, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“We see lots of teenagers who are on a restrictive diet,” which is “certainly one reason they could be failing isotretinoin,” Dr. Treat said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Often, patients say that they have been referred to him because they had no response to 20 mg or 30 mg per day of isotretinoin. But after a dose escalation to 60 mg per day, their acne worsened.

If the patient’s acne is worsening with a cystic flare, “tripling the dose of isotretinoin is not something that you should do,” Dr. Treat said. “You should lower the dose and consider adding steroids.” For evidence-based recommendations on managing acne fulminans, he recommended an article published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017.

Skin picking is another common reason for failure of isotretinoin, as well as with other acne therapies. These patients may have associated anxiety, which “might be a contraindication or at least something to consider before you put them on isotretinoin,” he noted.

In his experience, off-label use of N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant and cysteine prodrug, has been “extremely effective” for patients with excoriation disorder. In a randomized trial of adults 18-60 years of age, 47% patients who took 1,200-3,000 mg per day doses of N-acetylcysteine for 12 weeks reported that their skin picking was much or very much improved, compared to 19% of those who took placebo (P = .03). The authors wrote that N-acetylcysteine “increases extracellular levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens,” and that these results support the hypothesis that “pharmacologic manipulation of the glutamate system may target core symptoms of compulsive behaviors.”

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha blocker adalimumab is a reasonable option for patients with severe cystic inflammatory acne who fail isotretinoin, Dr. Treat said. In one published case, clinicians administered adalimumab 40 mg every other week for a 16-year-old male patient who received isotretinoin for moderate acne vulgaris, which caused sudden development of acne fulminans and incapacitating acute sacroiliitis with bilateral hip arthritis. Inflammatory lesions started to clear in 1 month and comedones improved by 3 months of treatment. Adalimumab was discontinued after 1 year and the patient remained clear.

“There are now multiple reports as well as some case series showing TNF-alpha agents causing clearance of acne,” said Dr. Treat, who directs the hospital’s pediatric dermatology fellowship program. A literature review of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab for treatment-resistant acne found that all agents had similar efficacy after 3-6 months of therapy. “We see this in our GI population, where TNF-alpha agents are helping their acne also,” he said. “We just have to augment it with some topical medications.”

Certain medications can drive the development of acne, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, lithium, MEK inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors, systemic steroids, and unopposed progesterone contraceptives. Some genetic conditions also predispose patients to acne, including mutations in the NCSTN gene and trisomy 13.

Dr. Treat discussed one of his patients with severe acne who had trisomy 13. The patient failed 12 months of doxycycline and amoxicillin in combination with a topical retinoid. He also failed low- and high-dose isotretinoin in combination with prednisone, as well as oral dapsone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 3 months. He was started on adalimumab, but that was stopped after he flared. The patient is now maintained on ustekinumab monthly at a dose of 45 mg.

“I’ve only had a few patients where isotretinoin truly has failed,” Dr. Treat said. He described one patient with severe acne who had a hidradenitis-like appearance in his axilla and groin. “I treated with isotretinoin very gingerly in the beginning, [but] he flared significantly. I had given him concomitant steroids from the very beginning and transitioned to multiple different therapies – all of which failed.”

Next, Dr. Treat tried a course of systemic dapsone, and the patient responded nicely. “As an anti-inflammatory agent, dapsone is very reasonable” to consider, he said. “It’s something to add to your armamentarium.”

Dr. Treat disclosed that he is a consultant for Palvella and Regeneron. He has ownership interests in Matinas Biopharma Holdings, Axsome, Sorrento, and Amarin.

INDIANAPOLIS – – which is known to increase the drug’s bioavailability, advises James R. Treat, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“We see lots of teenagers who are on a restrictive diet,” which is “certainly one reason they could be failing isotretinoin,” Dr. Treat said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Often, patients say that they have been referred to him because they had no response to 20 mg or 30 mg per day of isotretinoin. But after a dose escalation to 60 mg per day, their acne worsened.

If the patient’s acne is worsening with a cystic flare, “tripling the dose of isotretinoin is not something that you should do,” Dr. Treat said. “You should lower the dose and consider adding steroids.” For evidence-based recommendations on managing acne fulminans, he recommended an article published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017.

Skin picking is another common reason for failure of isotretinoin, as well as with other acne therapies. These patients may have associated anxiety, which “might be a contraindication or at least something to consider before you put them on isotretinoin,” he noted.

In his experience, off-label use of N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant and cysteine prodrug, has been “extremely effective” for patients with excoriation disorder. In a randomized trial of adults 18-60 years of age, 47% patients who took 1,200-3,000 mg per day doses of N-acetylcysteine for 12 weeks reported that their skin picking was much or very much improved, compared to 19% of those who took placebo (P = .03). The authors wrote that N-acetylcysteine “increases extracellular levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens,” and that these results support the hypothesis that “pharmacologic manipulation of the glutamate system may target core symptoms of compulsive behaviors.”

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha blocker adalimumab is a reasonable option for patients with severe cystic inflammatory acne who fail isotretinoin, Dr. Treat said. In one published case, clinicians administered adalimumab 40 mg every other week for a 16-year-old male patient who received isotretinoin for moderate acne vulgaris, which caused sudden development of acne fulminans and incapacitating acute sacroiliitis with bilateral hip arthritis. Inflammatory lesions started to clear in 1 month and comedones improved by 3 months of treatment. Adalimumab was discontinued after 1 year and the patient remained clear.

“There are now multiple reports as well as some case series showing TNF-alpha agents causing clearance of acne,” said Dr. Treat, who directs the hospital’s pediatric dermatology fellowship program. A literature review of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab for treatment-resistant acne found that all agents had similar efficacy after 3-6 months of therapy. “We see this in our GI population, where TNF-alpha agents are helping their acne also,” he said. “We just have to augment it with some topical medications.”

Certain medications can drive the development of acne, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, lithium, MEK inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors, systemic steroids, and unopposed progesterone contraceptives. Some genetic conditions also predispose patients to acne, including mutations in the NCSTN gene and trisomy 13.

Dr. Treat discussed one of his patients with severe acne who had trisomy 13. The patient failed 12 months of doxycycline and amoxicillin in combination with a topical retinoid. He also failed low- and high-dose isotretinoin in combination with prednisone, as well as oral dapsone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 3 months. He was started on adalimumab, but that was stopped after he flared. The patient is now maintained on ustekinumab monthly at a dose of 45 mg.

“I’ve only had a few patients where isotretinoin truly has failed,” Dr. Treat said. He described one patient with severe acne who had a hidradenitis-like appearance in his axilla and groin. “I treated with isotretinoin very gingerly in the beginning, [but] he flared significantly. I had given him concomitant steroids from the very beginning and transitioned to multiple different therapies – all of which failed.”

Next, Dr. Treat tried a course of systemic dapsone, and the patient responded nicely. “As an anti-inflammatory agent, dapsone is very reasonable” to consider, he said. “It’s something to add to your armamentarium.”

Dr. Treat disclosed that he is a consultant for Palvella and Regeneron. He has ownership interests in Matinas Biopharma Holdings, Axsome, Sorrento, and Amarin.

INDIANAPOLIS – – which is known to increase the drug’s bioavailability, advises James R. Treat, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“We see lots of teenagers who are on a restrictive diet,” which is “certainly one reason they could be failing isotretinoin,” Dr. Treat said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Often, patients say that they have been referred to him because they had no response to 20 mg or 30 mg per day of isotretinoin. But after a dose escalation to 60 mg per day, their acne worsened.

If the patient’s acne is worsening with a cystic flare, “tripling the dose of isotretinoin is not something that you should do,” Dr. Treat said. “You should lower the dose and consider adding steroids.” For evidence-based recommendations on managing acne fulminans, he recommended an article published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2017.

Skin picking is another common reason for failure of isotretinoin, as well as with other acne therapies. These patients may have associated anxiety, which “might be a contraindication or at least something to consider before you put them on isotretinoin,” he noted.

In his experience, off-label use of N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant and cysteine prodrug, has been “extremely effective” for patients with excoriation disorder. In a randomized trial of adults 18-60 years of age, 47% patients who took 1,200-3,000 mg per day doses of N-acetylcysteine for 12 weeks reported that their skin picking was much or very much improved, compared to 19% of those who took placebo (P = .03). The authors wrote that N-acetylcysteine “increases extracellular levels of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens,” and that these results support the hypothesis that “pharmacologic manipulation of the glutamate system may target core symptoms of compulsive behaviors.”

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha blocker adalimumab is a reasonable option for patients with severe cystic inflammatory acne who fail isotretinoin, Dr. Treat said. In one published case, clinicians administered adalimumab 40 mg every other week for a 16-year-old male patient who received isotretinoin for moderate acne vulgaris, which caused sudden development of acne fulminans and incapacitating acute sacroiliitis with bilateral hip arthritis. Inflammatory lesions started to clear in 1 month and comedones improved by 3 months of treatment. Adalimumab was discontinued after 1 year and the patient remained clear.

“There are now multiple reports as well as some case series showing TNF-alpha agents causing clearance of acne,” said Dr. Treat, who directs the hospital’s pediatric dermatology fellowship program. A literature review of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab for treatment-resistant acne found that all agents had similar efficacy after 3-6 months of therapy. “We see this in our GI population, where TNF-alpha agents are helping their acne also,” he said. “We just have to augment it with some topical medications.”

Certain medications can drive the development of acne, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, lithium, MEK inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors, systemic steroids, and unopposed progesterone contraceptives. Some genetic conditions also predispose patients to acne, including mutations in the NCSTN gene and trisomy 13.

Dr. Treat discussed one of his patients with severe acne who had trisomy 13. The patient failed 12 months of doxycycline and amoxicillin in combination with a topical retinoid. He also failed low- and high-dose isotretinoin in combination with prednisone, as well as oral dapsone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 3 months. He was started on adalimumab, but that was stopped after he flared. The patient is now maintained on ustekinumab monthly at a dose of 45 mg.

“I’ve only had a few patients where isotretinoin truly has failed,” Dr. Treat said. He described one patient with severe acne who had a hidradenitis-like appearance in his axilla and groin. “I treated with isotretinoin very gingerly in the beginning, [but] he flared significantly. I had given him concomitant steroids from the very beginning and transitioned to multiple different therapies – all of which failed.”

Next, Dr. Treat tried a course of systemic dapsone, and the patient responded nicely. “As an anti-inflammatory agent, dapsone is very reasonable” to consider, he said. “It’s something to add to your armamentarium.”

Dr. Treat disclosed that he is a consultant for Palvella and Regeneron. He has ownership interests in Matinas Biopharma Holdings, Axsome, Sorrento, and Amarin.

AT SPD 2022

Scientists aim to combat COVID with a shot in the nose

Scientists seeking to stay ahead of an evolving SARS-Cov-2 virus are looking at new strategies, including developing intranasal vaccines, according to speakers at a conference on July 26.

inviting researchers to provide a public update on efforts to try to keep ahead of SARS-CoV-2.

Scientists and federal officials are looking to build on the successes seen in developing the original crop of COVID vaccines, which were authorized for use in the United States less than a year after the pandemic took hold.

But emerging variants are eroding these gains. For months now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have been keeping an eye on how the level of effectiveness of COVID vaccines has waned during the rise of the Omicron strain. And there’s continual concern about how SARS-CoV-2 might evolve over time.

“Our vaccines are terrific,” Ashish K. Jha, MD, the White House’s COVID-19 response coordinator, said at the summit. “[But] we have to do better.”

Among the approaches being considered are vaccines that would be applied intranasally, with the idea that this might be able to boost the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

At the summit, Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the intranasal approach might be helpful in preventing transmission as well as reducing the burden of illness for those who are infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“We’re stopping the virus from spreading right at the border,” Dr. Iwasaki said at the summit. “This is akin to putting a guard outside of the house in order to patrol for invaders compared to putting the guards in the hallway of the building in the hope that they capture the invader.”

Dr. Iwasaki is one of the founders of Xanadu Bio, a private company created last year to focus on ways to kill SARS-CoV-2 in the nasosinus before it spreads deeper into the respiratory tract. In an editorial in Science Immunology, Dr. Iwasaki and Eric J. Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, urged greater federal investment in this approach to fighting SARS-CoV-2. (Dr. Topol is editor-in-chief of Medscape.)

Titled “Operation Nasal Vaccine – Lightning speed to counter COVID-19,” their editorial noted the “unprecedented success” seen in the rapid development of the first two mRNA shots. Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol noted that these victories had been “fueled by the $10 billion governmental investment in Operation Warp Speed.

“During the first year of the pandemic, meaningful evolution of the virus was slow-paced, without any functional consequences, but since that time we have seen a succession of important variants of concern, with increasing transmissibility and immune evasion, culminating in the Omicron lineages,” wrote Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol.

Recent developments have “spotlighted the possibility of nasal vaccines, with their allure for achieving mucosal immunity, complementing, and likely bolstering the circulating immunity achieved via intramuscular shots,” they added.

An early setback

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) have for some time been looking to vet an array of next-generation vaccine concepts, including ones that trigger mucosal immunity, the Washington Post reported in April.

At the summit on July 26, several participants, including Dr. Jha, stressed the role that public-private partnerships were key to the rapid development of the initial COVID vaccines. They said continued U.S. government support will be needed to make advances in this field.

One of the presenters, Biao He, PhD, founder and president of CyanVac and Blue Lake Biotechnology, spoke of the federal support that his efforts have received over the years to develop intranasal vaccines. His Georgia-based firm already has an experimental intranasal vaccine candidate, CVXGA1-001, in phase 1 testing (NCT04954287).

The CVXGA-001 builds on technology already used in a veterinary product, an intranasal vaccine long used to prevent kennel cough in dogs, he said at the summit.

The emerging field of experimental intranasal COVID vaccines already has had at least one setback.

The biotech firm Altimmune in June 2021 announced that it would discontinue development of its experimental intranasal AdCOVID vaccine following disappointing phase 1 results. The vaccine appeared to be well tolerated in the test, but the immunogenicity data demonstrated lower than expected results in healthy volunteers, especially in light of the responses seen to already cleared vaccines, Altimmune said in a release.

In the statement, Scot Roberts, PhD, chief scientific officer at Altimmune, noted that the study participants lacked immunity from prior infection or vaccination. “We believe that prior immunity in humans may be important for a robust immune response to intranasal dosing with AdCOVID,” he said.

At the summit, Marty Moore, PhD, cofounder and chief scientific officer for Redwood City, Calif.–based Meissa Vaccines, noted the challenges that remain ahead for intranasal COVID vaccines, while also highlighting what he sees as the potential of this approach.

Meissa also has advanced an experimental intranasal COVID vaccine as far as phase 1 testing (NCT04798001).

“No one here today can tell you that mucosal COVID vaccines work. We’re not there yet. We need clinical efficacy data to answer that question,” Dr. Moore said.

But there’s a potential for a “knockout blow to COVID, a transmission-blocking vaccine” from the intranasal approach, he said.

“The virus is mutating faster than our ability to manage vaccines and not enough people are getting boosters. These injectable vaccines do a great job of preventing severe disease, but they do little to prevent infection” from spreading, Dr. Moore said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists seeking to stay ahead of an evolving SARS-Cov-2 virus are looking at new strategies, including developing intranasal vaccines, according to speakers at a conference on July 26.

inviting researchers to provide a public update on efforts to try to keep ahead of SARS-CoV-2.

Scientists and federal officials are looking to build on the successes seen in developing the original crop of COVID vaccines, which were authorized for use in the United States less than a year after the pandemic took hold.

But emerging variants are eroding these gains. For months now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have been keeping an eye on how the level of effectiveness of COVID vaccines has waned during the rise of the Omicron strain. And there’s continual concern about how SARS-CoV-2 might evolve over time.

“Our vaccines are terrific,” Ashish K. Jha, MD, the White House’s COVID-19 response coordinator, said at the summit. “[But] we have to do better.”

Among the approaches being considered are vaccines that would be applied intranasally, with the idea that this might be able to boost the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

At the summit, Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the intranasal approach might be helpful in preventing transmission as well as reducing the burden of illness for those who are infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“We’re stopping the virus from spreading right at the border,” Dr. Iwasaki said at the summit. “This is akin to putting a guard outside of the house in order to patrol for invaders compared to putting the guards in the hallway of the building in the hope that they capture the invader.”

Dr. Iwasaki is one of the founders of Xanadu Bio, a private company created last year to focus on ways to kill SARS-CoV-2 in the nasosinus before it spreads deeper into the respiratory tract. In an editorial in Science Immunology, Dr. Iwasaki and Eric J. Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, urged greater federal investment in this approach to fighting SARS-CoV-2. (Dr. Topol is editor-in-chief of Medscape.)

Titled “Operation Nasal Vaccine – Lightning speed to counter COVID-19,” their editorial noted the “unprecedented success” seen in the rapid development of the first two mRNA shots. Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol noted that these victories had been “fueled by the $10 billion governmental investment in Operation Warp Speed.

“During the first year of the pandemic, meaningful evolution of the virus was slow-paced, without any functional consequences, but since that time we have seen a succession of important variants of concern, with increasing transmissibility and immune evasion, culminating in the Omicron lineages,” wrote Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol.

Recent developments have “spotlighted the possibility of nasal vaccines, with their allure for achieving mucosal immunity, complementing, and likely bolstering the circulating immunity achieved via intramuscular shots,” they added.

An early setback

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) have for some time been looking to vet an array of next-generation vaccine concepts, including ones that trigger mucosal immunity, the Washington Post reported in April.

At the summit on July 26, several participants, including Dr. Jha, stressed the role that public-private partnerships were key to the rapid development of the initial COVID vaccines. They said continued U.S. government support will be needed to make advances in this field.

One of the presenters, Biao He, PhD, founder and president of CyanVac and Blue Lake Biotechnology, spoke of the federal support that his efforts have received over the years to develop intranasal vaccines. His Georgia-based firm already has an experimental intranasal vaccine candidate, CVXGA1-001, in phase 1 testing (NCT04954287).

The CVXGA-001 builds on technology already used in a veterinary product, an intranasal vaccine long used to prevent kennel cough in dogs, he said at the summit.

The emerging field of experimental intranasal COVID vaccines already has had at least one setback.

The biotech firm Altimmune in June 2021 announced that it would discontinue development of its experimental intranasal AdCOVID vaccine following disappointing phase 1 results. The vaccine appeared to be well tolerated in the test, but the immunogenicity data demonstrated lower than expected results in healthy volunteers, especially in light of the responses seen to already cleared vaccines, Altimmune said in a release.

In the statement, Scot Roberts, PhD, chief scientific officer at Altimmune, noted that the study participants lacked immunity from prior infection or vaccination. “We believe that prior immunity in humans may be important for a robust immune response to intranasal dosing with AdCOVID,” he said.

At the summit, Marty Moore, PhD, cofounder and chief scientific officer for Redwood City, Calif.–based Meissa Vaccines, noted the challenges that remain ahead for intranasal COVID vaccines, while also highlighting what he sees as the potential of this approach.

Meissa also has advanced an experimental intranasal COVID vaccine as far as phase 1 testing (NCT04798001).

“No one here today can tell you that mucosal COVID vaccines work. We’re not there yet. We need clinical efficacy data to answer that question,” Dr. Moore said.

But there’s a potential for a “knockout blow to COVID, a transmission-blocking vaccine” from the intranasal approach, he said.

“The virus is mutating faster than our ability to manage vaccines and not enough people are getting boosters. These injectable vaccines do a great job of preventing severe disease, but they do little to prevent infection” from spreading, Dr. Moore said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists seeking to stay ahead of an evolving SARS-Cov-2 virus are looking at new strategies, including developing intranasal vaccines, according to speakers at a conference on July 26.

inviting researchers to provide a public update on efforts to try to keep ahead of SARS-CoV-2.

Scientists and federal officials are looking to build on the successes seen in developing the original crop of COVID vaccines, which were authorized for use in the United States less than a year after the pandemic took hold.

But emerging variants are eroding these gains. For months now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have been keeping an eye on how the level of effectiveness of COVID vaccines has waned during the rise of the Omicron strain. And there’s continual concern about how SARS-CoV-2 might evolve over time.

“Our vaccines are terrific,” Ashish K. Jha, MD, the White House’s COVID-19 response coordinator, said at the summit. “[But] we have to do better.”

Among the approaches being considered are vaccines that would be applied intranasally, with the idea that this might be able to boost the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

At the summit, Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the intranasal approach might be helpful in preventing transmission as well as reducing the burden of illness for those who are infected with SARS-CoV-2.

“We’re stopping the virus from spreading right at the border,” Dr. Iwasaki said at the summit. “This is akin to putting a guard outside of the house in order to patrol for invaders compared to putting the guards in the hallway of the building in the hope that they capture the invader.”

Dr. Iwasaki is one of the founders of Xanadu Bio, a private company created last year to focus on ways to kill SARS-CoV-2 in the nasosinus before it spreads deeper into the respiratory tract. In an editorial in Science Immunology, Dr. Iwasaki and Eric J. Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, urged greater federal investment in this approach to fighting SARS-CoV-2. (Dr. Topol is editor-in-chief of Medscape.)

Titled “Operation Nasal Vaccine – Lightning speed to counter COVID-19,” their editorial noted the “unprecedented success” seen in the rapid development of the first two mRNA shots. Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol noted that these victories had been “fueled by the $10 billion governmental investment in Operation Warp Speed.

“During the first year of the pandemic, meaningful evolution of the virus was slow-paced, without any functional consequences, but since that time we have seen a succession of important variants of concern, with increasing transmissibility and immune evasion, culminating in the Omicron lineages,” wrote Dr. Iwasaki and Dr. Topol.

Recent developments have “spotlighted the possibility of nasal vaccines, with their allure for achieving mucosal immunity, complementing, and likely bolstering the circulating immunity achieved via intramuscular shots,” they added.

An early setback

Scientists at the National Institutes of Health and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) have for some time been looking to vet an array of next-generation vaccine concepts, including ones that trigger mucosal immunity, the Washington Post reported in April.

At the summit on July 26, several participants, including Dr. Jha, stressed the role that public-private partnerships were key to the rapid development of the initial COVID vaccines. They said continued U.S. government support will be needed to make advances in this field.

One of the presenters, Biao He, PhD, founder and president of CyanVac and Blue Lake Biotechnology, spoke of the federal support that his efforts have received over the years to develop intranasal vaccines. His Georgia-based firm already has an experimental intranasal vaccine candidate, CVXGA1-001, in phase 1 testing (NCT04954287).

The CVXGA-001 builds on technology already used in a veterinary product, an intranasal vaccine long used to prevent kennel cough in dogs, he said at the summit.

The emerging field of experimental intranasal COVID vaccines already has had at least one setback.

The biotech firm Altimmune in June 2021 announced that it would discontinue development of its experimental intranasal AdCOVID vaccine following disappointing phase 1 results. The vaccine appeared to be well tolerated in the test, but the immunogenicity data demonstrated lower than expected results in healthy volunteers, especially in light of the responses seen to already cleared vaccines, Altimmune said in a release.

In the statement, Scot Roberts, PhD, chief scientific officer at Altimmune, noted that the study participants lacked immunity from prior infection or vaccination. “We believe that prior immunity in humans may be important for a robust immune response to intranasal dosing with AdCOVID,” he said.

At the summit, Marty Moore, PhD, cofounder and chief scientific officer for Redwood City, Calif.–based Meissa Vaccines, noted the challenges that remain ahead for intranasal COVID vaccines, while also highlighting what he sees as the potential of this approach.

Meissa also has advanced an experimental intranasal COVID vaccine as far as phase 1 testing (NCT04798001).

“No one here today can tell you that mucosal COVID vaccines work. We’re not there yet. We need clinical efficacy data to answer that question,” Dr. Moore said.

But there’s a potential for a “knockout blow to COVID, a transmission-blocking vaccine” from the intranasal approach, he said.

“The virus is mutating faster than our ability to manage vaccines and not enough people are getting boosters. These injectable vaccines do a great job of preventing severe disease, but they do little to prevent infection” from spreading, Dr. Moore said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exceeding exercise guidelines boosts survival, to a point

A new study suggests that going beyond current guidance on moderate and vigorous physical activity levels may add years to one’s life.

Americans are advised to do a minimum of 150-300 minutes a week of moderate exercise or 75-150 minutes a week of vigorous exercise, or an equivalent combination of both, according to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines.

Results from more than 100,000 U.S. adults followed for 30 years showed that .

Adults who reported completing four times the minimum recommended activity levels saw no clear incremental mortality benefit but also no harm, according to the study, published in the journal Circulation.

“I think we’re worried more about the lower end and people that are not even doing the minimum, but this should be reassuring to people who like to do a lot of exercise,” senior author Edward Giovannucci, MD, ScD, with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, told this news organization.

Some studies have suggested that long-term, high-intensity exercise (e.g., marathons, triathlons, and long-distance cycling) may be associated with increased risks of atrial fibrillation, coronary artery calcification, and sudden cardiac death.

A recent analysis from the Copenhagen City Heart Study showed a U-shaped association between long-term all-cause mortality and 0 to 2.5 hours and more than 10 hours of weekly, leisure-time sports activities.

Most studies suggesting harm, however, have used only one measurement of physical activity capturing a mix of people who chronically exercise at high levels and those who do it sporadically, which possibly can be harmful, Dr. Giovannucci said. “We were better able to look at consistent long-term activity and saw there was no harm.”

The study included 116,221 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study between 1988 and 2018, who completed up to 15 (median, 11) questionnaires on their health and leisure-time physical activity that were updated every 2 years.

Most were White (96%), 63% were female, and the average age and body mass index over follow-up was 66 years and 26 kg/m2. During 30 years of follow-up, there were 47,596 deaths.

‘Any effort is worthwhile’

The analysis found that individuals who met the guideline for long-term vigorous physical activity (75-150 min/week) cut their adjusted risk of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD) by a whopping 31%, from non-CVD causes by 15%, and all-causes by 19%, compared with those with no long-term vigorous activity.

Those completing two to four times the recommended minimum (150-299 min/week) had a 27%-33% lower risk of CVD mortality, 19% lower risk of non-CVD mortality, and 21%-23% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

Higher levels did not appear to further lower mortality risk. For example, 300-374 min/week of vigorous physical activity was associated with a 32% lower risk of CVD death, 18% lower risk of non-CVD death, and 22% lower risk of dying from any cause.

The analysis also found that individuals who met the guidelines for moderate physical activity had lower CVD, non-CVD, and all-cause mortality risks whether they were active 150-244 min/week (22%, 19%, and 20%, respectively) or 225-299 min/week (21%, 25%, and 20%, respectively), compared with those with almost no long-term moderate activity.

Those fitting in two to four times the recommended minimum (300-599 min/week) had a 28%-38% lower risk of CVD mortality, 25%-27% lower risk of non-CVD mortality, and 26%-31% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

The mortality benefit appeared to plateau, with 600 min/week of moderate physical activity showing associations similar to 300-599 min/week.

“The sweet spot seems to be two to four times the recommended levels but for people who are sedentary, I think one of the key messages that I give my patients is that any effort is worthwhile; that any physical activity, even less than the recommended, has some mortality reduction,” Erin Michos, MD, MHS, associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview.

Indeed, individuals who reported doing just 20-74 minutes of moderate exercise per week had a 19% lower risk of dying from any cause and a 13% lower risk of dying from CVD compared with those doing less.

Current American Heart Association (AHA) recommendations are for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic exercise, or a combination of both.

“This suggests that even more is probably better, in the range of two to four times that, so maybe we should move our targets a little bit higher, which is kind of what the Department of Health and Human Services has already done,” said Dr. Michos, who was not involved in the study.

Former AHA president Donna K. Arnett, PhD, who was not involved in the study, said in a statement that “we’ve known for a long time that moderate or intense levels of physical exercise can reduce a person’s risk of both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and mortality.

“We have also seen that getting more than 300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or more than 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical exercise each week may reduce a person’s risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease even further, so it makes sense that getting those extra minutes of exercise may also decrease mortality,” she added.

Mix and match

Dr. Giovannucci noted that the joint effects of the two types of exercise on mortality have not been studied and “there are some questions, for example, about whether doing a lot of moderate activity is sufficient or can you get more benefits by doing vigorous activity also.”

Joint analyses of both exercise intensities found that additional vigorous physical activity was associated with lower mortality among participants with insufficient (less than 300 min/week) levels of moderate exercise but not among those with at least 300 min/week of moderate exercise.

“The main message is that you can get essentially all of the benefit by just doing moderate exercise,” Dr. Giovannucci said. “There’s no magic benefit of doing vigorous [exercise]. But if someone wants to do vigorous, they can get the benefit in about half the time. So if you only have 2-3 hours a week to exercise and can do, say 2 or 3 hours of running, you can get pretty much the maximum benefit.”

Sensitivity analyses showed a consistent association between long-term leisure physical activity and mortality without adjustment for body mass index/calorie intake.

“Some people think the effect of exercise is to lower your body weight or keep it down, which could be one of the benefits, but even independent of that, you get benefits even if it has no effect on your weight,” he said. “So, definitely, that’s important.”

Dr. Michos pointed out that vigorous physical activity may seem daunting for many individuals but that moderate exercise can include activities such as brisk walking, ballroom dancing, active yoga, and recreational swimming.

“The nice thing is that you can really combine or substitute both and get just as similar mortality reductions with moderate physical activity, because a lot of patients may not want to do vigorous activity,” she said. “They don’t want to get on the treadmill; that’s too intimidating or stressful.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Michos report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study suggests that going beyond current guidance on moderate and vigorous physical activity levels may add years to one’s life.

Americans are advised to do a minimum of 150-300 minutes a week of moderate exercise or 75-150 minutes a week of vigorous exercise, or an equivalent combination of both, according to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines.

Results from more than 100,000 U.S. adults followed for 30 years showed that .

Adults who reported completing four times the minimum recommended activity levels saw no clear incremental mortality benefit but also no harm, according to the study, published in the journal Circulation.

“I think we’re worried more about the lower end and people that are not even doing the minimum, but this should be reassuring to people who like to do a lot of exercise,” senior author Edward Giovannucci, MD, ScD, with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, told this news organization.

Some studies have suggested that long-term, high-intensity exercise (e.g., marathons, triathlons, and long-distance cycling) may be associated with increased risks of atrial fibrillation, coronary artery calcification, and sudden cardiac death.

A recent analysis from the Copenhagen City Heart Study showed a U-shaped association between long-term all-cause mortality and 0 to 2.5 hours and more than 10 hours of weekly, leisure-time sports activities.

Most studies suggesting harm, however, have used only one measurement of physical activity capturing a mix of people who chronically exercise at high levels and those who do it sporadically, which possibly can be harmful, Dr. Giovannucci said. “We were better able to look at consistent long-term activity and saw there was no harm.”

The study included 116,221 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study between 1988 and 2018, who completed up to 15 (median, 11) questionnaires on their health and leisure-time physical activity that were updated every 2 years.

Most were White (96%), 63% were female, and the average age and body mass index over follow-up was 66 years and 26 kg/m2. During 30 years of follow-up, there were 47,596 deaths.

‘Any effort is worthwhile’

The analysis found that individuals who met the guideline for long-term vigorous physical activity (75-150 min/week) cut their adjusted risk of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD) by a whopping 31%, from non-CVD causes by 15%, and all-causes by 19%, compared with those with no long-term vigorous activity.

Those completing two to four times the recommended minimum (150-299 min/week) had a 27%-33% lower risk of CVD mortality, 19% lower risk of non-CVD mortality, and 21%-23% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

Higher levels did not appear to further lower mortality risk. For example, 300-374 min/week of vigorous physical activity was associated with a 32% lower risk of CVD death, 18% lower risk of non-CVD death, and 22% lower risk of dying from any cause.

The analysis also found that individuals who met the guidelines for moderate physical activity had lower CVD, non-CVD, and all-cause mortality risks whether they were active 150-244 min/week (22%, 19%, and 20%, respectively) or 225-299 min/week (21%, 25%, and 20%, respectively), compared with those with almost no long-term moderate activity.

Those fitting in two to four times the recommended minimum (300-599 min/week) had a 28%-38% lower risk of CVD mortality, 25%-27% lower risk of non-CVD mortality, and 26%-31% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

The mortality benefit appeared to plateau, with 600 min/week of moderate physical activity showing associations similar to 300-599 min/week.

“The sweet spot seems to be two to four times the recommended levels but for people who are sedentary, I think one of the key messages that I give my patients is that any effort is worthwhile; that any physical activity, even less than the recommended, has some mortality reduction,” Erin Michos, MD, MHS, associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview.

Indeed, individuals who reported doing just 20-74 minutes of moderate exercise per week had a 19% lower risk of dying from any cause and a 13% lower risk of dying from CVD compared with those doing less.

Current American Heart Association (AHA) recommendations are for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic exercise, or a combination of both.

“This suggests that even more is probably better, in the range of two to four times that, so maybe we should move our targets a little bit higher, which is kind of what the Department of Health and Human Services has already done,” said Dr. Michos, who was not involved in the study.

Former AHA president Donna K. Arnett, PhD, who was not involved in the study, said in a statement that “we’ve known for a long time that moderate or intense levels of physical exercise can reduce a person’s risk of both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and mortality.

“We have also seen that getting more than 300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or more than 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical exercise each week may reduce a person’s risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease even further, so it makes sense that getting those extra minutes of exercise may also decrease mortality,” she added.

Mix and match

Dr. Giovannucci noted that the joint effects of the two types of exercise on mortality have not been studied and “there are some questions, for example, about whether doing a lot of moderate activity is sufficient or can you get more benefits by doing vigorous activity also.”

Joint analyses of both exercise intensities found that additional vigorous physical activity was associated with lower mortality among participants with insufficient (less than 300 min/week) levels of moderate exercise but not among those with at least 300 min/week of moderate exercise.

“The main message is that you can get essentially all of the benefit by just doing moderate exercise,” Dr. Giovannucci said. “There’s no magic benefit of doing vigorous [exercise]. But if someone wants to do vigorous, they can get the benefit in about half the time. So if you only have 2-3 hours a week to exercise and can do, say 2 or 3 hours of running, you can get pretty much the maximum benefit.”

Sensitivity analyses showed a consistent association between long-term leisure physical activity and mortality without adjustment for body mass index/calorie intake.

“Some people think the effect of exercise is to lower your body weight or keep it down, which could be one of the benefits, but even independent of that, you get benefits even if it has no effect on your weight,” he said. “So, definitely, that’s important.”

Dr. Michos pointed out that vigorous physical activity may seem daunting for many individuals but that moderate exercise can include activities such as brisk walking, ballroom dancing, active yoga, and recreational swimming.

“The nice thing is that you can really combine or substitute both and get just as similar mortality reductions with moderate physical activity, because a lot of patients may not want to do vigorous activity,” she said. “They don’t want to get on the treadmill; that’s too intimidating or stressful.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Michos report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study suggests that going beyond current guidance on moderate and vigorous physical activity levels may add years to one’s life.

Americans are advised to do a minimum of 150-300 minutes a week of moderate exercise or 75-150 minutes a week of vigorous exercise, or an equivalent combination of both, according to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines.

Results from more than 100,000 U.S. adults followed for 30 years showed that .

Adults who reported completing four times the minimum recommended activity levels saw no clear incremental mortality benefit but also no harm, according to the study, published in the journal Circulation.

“I think we’re worried more about the lower end and people that are not even doing the minimum, but this should be reassuring to people who like to do a lot of exercise,” senior author Edward Giovannucci, MD, ScD, with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, told this news organization.

Some studies have suggested that long-term, high-intensity exercise (e.g., marathons, triathlons, and long-distance cycling) may be associated with increased risks of atrial fibrillation, coronary artery calcification, and sudden cardiac death.

A recent analysis from the Copenhagen City Heart Study showed a U-shaped association between long-term all-cause mortality and 0 to 2.5 hours and more than 10 hours of weekly, leisure-time sports activities.

Most studies suggesting harm, however, have used only one measurement of physical activity capturing a mix of people who chronically exercise at high levels and those who do it sporadically, which possibly can be harmful, Dr. Giovannucci said. “We were better able to look at consistent long-term activity and saw there was no harm.”

The study included 116,221 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study between 1988 and 2018, who completed up to 15 (median, 11) questionnaires on their health and leisure-time physical activity that were updated every 2 years.

Most were White (96%), 63% were female, and the average age and body mass index over follow-up was 66 years and 26 kg/m2. During 30 years of follow-up, there were 47,596 deaths.

‘Any effort is worthwhile’

The analysis found that individuals who met the guideline for long-term vigorous physical activity (75-150 min/week) cut their adjusted risk of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD) by a whopping 31%, from non-CVD causes by 15%, and all-causes by 19%, compared with those with no long-term vigorous activity.

Those completing two to four times the recommended minimum (150-299 min/week) had a 27%-33% lower risk of CVD mortality, 19% lower risk of non-CVD mortality, and 21%-23% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

Higher levels did not appear to further lower mortality risk. For example, 300-374 min/week of vigorous physical activity was associated with a 32% lower risk of CVD death, 18% lower risk of non-CVD death, and 22% lower risk of dying from any cause.

The analysis also found that individuals who met the guidelines for moderate physical activity had lower CVD, non-CVD, and all-cause mortality risks whether they were active 150-244 min/week (22%, 19%, and 20%, respectively) or 225-299 min/week (21%, 25%, and 20%, respectively), compared with those with almost no long-term moderate activity.

Those fitting in two to four times the recommended minimum (300-599 min/week) had a 28%-38% lower risk of CVD mortality, 25%-27% lower risk of non-CVD mortality, and 26%-31% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

The mortality benefit appeared to plateau, with 600 min/week of moderate physical activity showing associations similar to 300-599 min/week.

“The sweet spot seems to be two to four times the recommended levels but for people who are sedentary, I think one of the key messages that I give my patients is that any effort is worthwhile; that any physical activity, even less than the recommended, has some mortality reduction,” Erin Michos, MD, MHS, associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview.

Indeed, individuals who reported doing just 20-74 minutes of moderate exercise per week had a 19% lower risk of dying from any cause and a 13% lower risk of dying from CVD compared with those doing less.

Current American Heart Association (AHA) recommendations are for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic exercise, or a combination of both.

“This suggests that even more is probably better, in the range of two to four times that, so maybe we should move our targets a little bit higher, which is kind of what the Department of Health and Human Services has already done,” said Dr. Michos, who was not involved in the study.

Former AHA president Donna K. Arnett, PhD, who was not involved in the study, said in a statement that “we’ve known for a long time that moderate or intense levels of physical exercise can reduce a person’s risk of both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and mortality.

“We have also seen that getting more than 300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or more than 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical exercise each week may reduce a person’s risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease even further, so it makes sense that getting those extra minutes of exercise may also decrease mortality,” she added.

Mix and match

Dr. Giovannucci noted that the joint effects of the two types of exercise on mortality have not been studied and “there are some questions, for example, about whether doing a lot of moderate activity is sufficient or can you get more benefits by doing vigorous activity also.”

Joint analyses of both exercise intensities found that additional vigorous physical activity was associated with lower mortality among participants with insufficient (less than 300 min/week) levels of moderate exercise but not among those with at least 300 min/week of moderate exercise.

“The main message is that you can get essentially all of the benefit by just doing moderate exercise,” Dr. Giovannucci said. “There’s no magic benefit of doing vigorous [exercise]. But if someone wants to do vigorous, they can get the benefit in about half the time. So if you only have 2-3 hours a week to exercise and can do, say 2 or 3 hours of running, you can get pretty much the maximum benefit.”

Sensitivity analyses showed a consistent association between long-term leisure physical activity and mortality without adjustment for body mass index/calorie intake.

“Some people think the effect of exercise is to lower your body weight or keep it down, which could be one of the benefits, but even independent of that, you get benefits even if it has no effect on your weight,” he said. “So, definitely, that’s important.”

Dr. Michos pointed out that vigorous physical activity may seem daunting for many individuals but that moderate exercise can include activities such as brisk walking, ballroom dancing, active yoga, and recreational swimming.

“The nice thing is that you can really combine or substitute both and get just as similar mortality reductions with moderate physical activity, because a lot of patients may not want to do vigorous activity,” she said. “They don’t want to get on the treadmill; that’s too intimidating or stressful.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Michos report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CIRCULATION

Good news, bad news

“Children’s hospitals saw a more than 25% decline in injury-related emergency room visits during the first year of the pandemic.” There’s a headline that should soothe a nation starved for some good news. It was based on a study published in Pediatrics that reports on data collected in the Pediatric Health Information System between March 2020 and March 2021 using a 3-year period between 2017 and 2020 as a control. How could this not be good news? First, let’s not be too hasty in celebrating the good fortune of all those millions of children spared the pain and anxiety of an emergency department visit.

If you were an administrator of an emergency department attempting to match revenues with expenses, a 25% drop in visits may have hit your bottom line. Office-based pediatricians experienced a similar phenomenon when many parents quickly learned that they could ignore or self-manage minor illnesses and complaints.

A decrease in visits doesn’t necessarily mean that the conditions that drive the traffic flow in your facility have gone away. It may simply be that they are being managed somewhere else. However, it is equally likely that for some reason the pandemic created situations that made the usual illnesses and injuries that flood into emergency departments less likely to occur. And, here, other anecdotal evidence about weight gain and a decline in fitness point to the conclusion that when children are no longer in school, they settle into more sedentary and less injury-generating activities. Injuries from falling off the couch watching television or playing video games alone do occur but certainly with less frequency than the random collisions that are inevitable when scores of classmates are running around on the playground.

So while it may be tempting to view a decline in emergency department visits as a positive statistic, this pandemic should remind us to be careful about how we choose our metrics to measure the health of the community. A decline in injuries in the short term may be masking a more serious erosion in the health of the pediatric population over the long term. At times I worry that as a specialty we are so focused on injury prevention that we lose sight of the fact that being physically active comes with a risk. A risk that we may wish to minimize, but a risk we must accept if we want to encourage the physical activity that we know is so important in the bigger health picture. For example, emergency department visits caused by pedal cycles initially rose 60%, eventually settling into the 25%-30% range leading one to suspect there was a learning or relearning curve.

However, while visits for minor injuries declined 25%, those associated with firearms rose initially 22%, and then 42%, and finally over 35%. These numbers combined with significant increases in visits from suffocation, nonpedal transportation, and suicide intent make it clear that, for most children, being in school is significantly less dangerous than staying at home.

As the pandemic continues to tumble on and we are presented with future questions about whether to keep schools open or closed, I hope the results of this study and others will help school officials and their advisers step back and look beyond the simple metric of case numbers and appreciate that there are benefits to being in school that go far beyond what can be learned in class.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

“Children’s hospitals saw a more than 25% decline in injury-related emergency room visits during the first year of the pandemic.” There’s a headline that should soothe a nation starved for some good news. It was based on a study published in Pediatrics that reports on data collected in the Pediatric Health Information System between March 2020 and March 2021 using a 3-year period between 2017 and 2020 as a control. How could this not be good news? First, let’s not be too hasty in celebrating the good fortune of all those millions of children spared the pain and anxiety of an emergency department visit.

If you were an administrator of an emergency department attempting to match revenues with expenses, a 25% drop in visits may have hit your bottom line. Office-based pediatricians experienced a similar phenomenon when many parents quickly learned that they could ignore or self-manage minor illnesses and complaints.

A decrease in visits doesn’t necessarily mean that the conditions that drive the traffic flow in your facility have gone away. It may simply be that they are being managed somewhere else. However, it is equally likely that for some reason the pandemic created situations that made the usual illnesses and injuries that flood into emergency departments less likely to occur. And, here, other anecdotal evidence about weight gain and a decline in fitness point to the conclusion that when children are no longer in school, they settle into more sedentary and less injury-generating activities. Injuries from falling off the couch watching television or playing video games alone do occur but certainly with less frequency than the random collisions that are inevitable when scores of classmates are running around on the playground.

So while it may be tempting to view a decline in emergency department visits as a positive statistic, this pandemic should remind us to be careful about how we choose our metrics to measure the health of the community. A decline in injuries in the short term may be masking a more serious erosion in the health of the pediatric population over the long term. At times I worry that as a specialty we are so focused on injury prevention that we lose sight of the fact that being physically active comes with a risk. A risk that we may wish to minimize, but a risk we must accept if we want to encourage the physical activity that we know is so important in the bigger health picture. For example, emergency department visits caused by pedal cycles initially rose 60%, eventually settling into the 25%-30% range leading one to suspect there was a learning or relearning curve.

However, while visits for minor injuries declined 25%, those associated with firearms rose initially 22%, and then 42%, and finally over 35%. These numbers combined with significant increases in visits from suffocation, nonpedal transportation, and suicide intent make it clear that, for most children, being in school is significantly less dangerous than staying at home.

As the pandemic continues to tumble on and we are presented with future questions about whether to keep schools open or closed, I hope the results of this study and others will help school officials and their advisers step back and look beyond the simple metric of case numbers and appreciate that there are benefits to being in school that go far beyond what can be learned in class.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

“Children’s hospitals saw a more than 25% decline in injury-related emergency room visits during the first year of the pandemic.” There’s a headline that should soothe a nation starved for some good news. It was based on a study published in Pediatrics that reports on data collected in the Pediatric Health Information System between March 2020 and March 2021 using a 3-year period between 2017 and 2020 as a control. How could this not be good news? First, let’s not be too hasty in celebrating the good fortune of all those millions of children spared the pain and anxiety of an emergency department visit.

If you were an administrator of an emergency department attempting to match revenues with expenses, a 25% drop in visits may have hit your bottom line. Office-based pediatricians experienced a similar phenomenon when many parents quickly learned that they could ignore or self-manage minor illnesses and complaints.

A decrease in visits doesn’t necessarily mean that the conditions that drive the traffic flow in your facility have gone away. It may simply be that they are being managed somewhere else. However, it is equally likely that for some reason the pandemic created situations that made the usual illnesses and injuries that flood into emergency departments less likely to occur. And, here, other anecdotal evidence about weight gain and a decline in fitness point to the conclusion that when children are no longer in school, they settle into more sedentary and less injury-generating activities. Injuries from falling off the couch watching television or playing video games alone do occur but certainly with less frequency than the random collisions that are inevitable when scores of classmates are running around on the playground.

So while it may be tempting to view a decline in emergency department visits as a positive statistic, this pandemic should remind us to be careful about how we choose our metrics to measure the health of the community. A decline in injuries in the short term may be masking a more serious erosion in the health of the pediatric population over the long term. At times I worry that as a specialty we are so focused on injury prevention that we lose sight of the fact that being physically active comes with a risk. A risk that we may wish to minimize, but a risk we must accept if we want to encourage the physical activity that we know is so important in the bigger health picture. For example, emergency department visits caused by pedal cycles initially rose 60%, eventually settling into the 25%-30% range leading one to suspect there was a learning or relearning curve.

However, while visits for minor injuries declined 25%, those associated with firearms rose initially 22%, and then 42%, and finally over 35%. These numbers combined with significant increases in visits from suffocation, nonpedal transportation, and suicide intent make it clear that, for most children, being in school is significantly less dangerous than staying at home.

As the pandemic continues to tumble on and we are presented with future questions about whether to keep schools open or closed, I hope the results of this study and others will help school officials and their advisers step back and look beyond the simple metric of case numbers and appreciate that there are benefits to being in school that go far beyond what can be learned in class.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Children and COVID: Many parents see vaccine as the greater risk

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

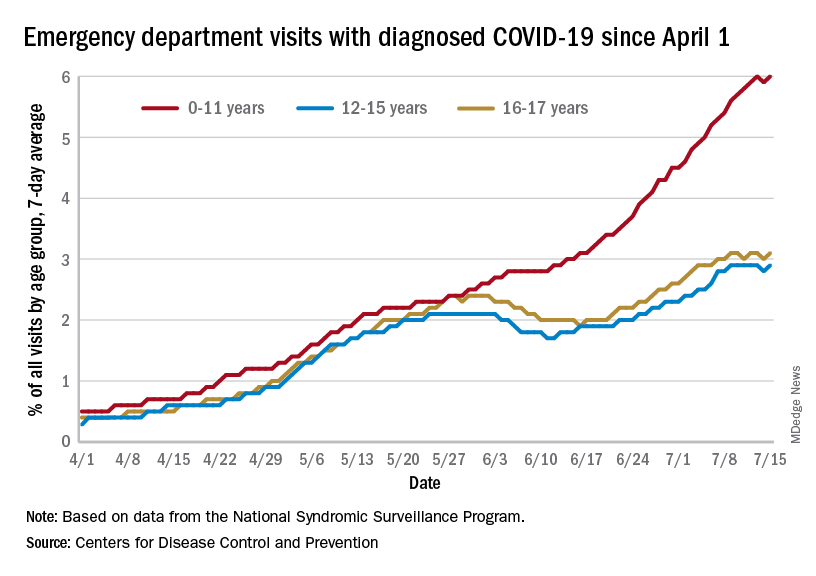

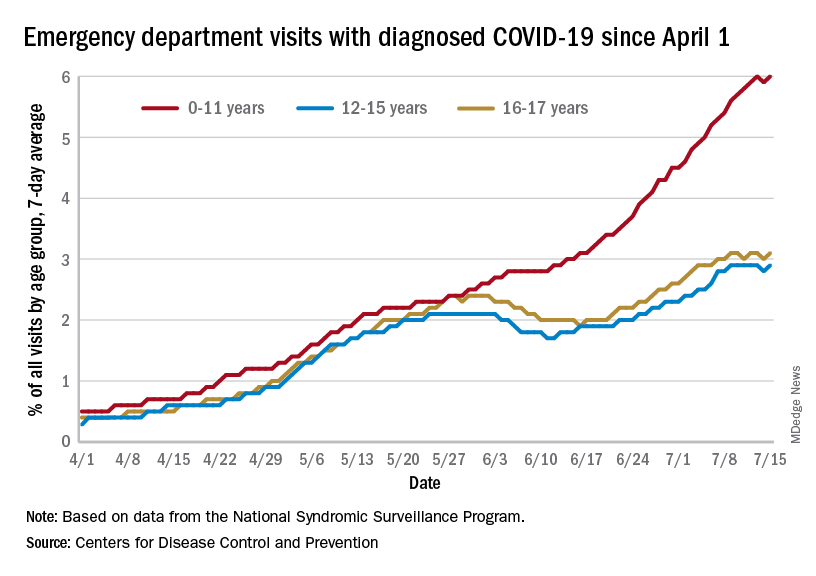

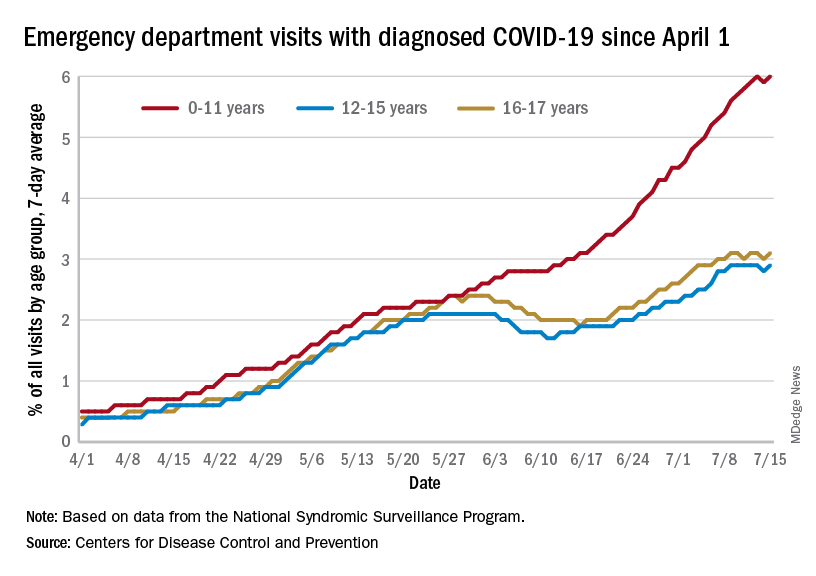

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

U.S. News issues top hospitals list, now with expanded health equity measures

For the seventh consecutive year, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., took the top spot in the annual honor roll of best hospitals, published July 26 by U.S. News & World Report.

The 2022 rankings, which marks the 33rd edition, showcase several methodology changes, including new ratings for ovarian, prostate, and uterine cancer surgeries that “provide patients ... with previously unavailable information to assist them in making a critical health care decision,” a news release from the publication explains.

said the release. Finally, a new metric called “home time” determines how successfully each hospital helps patients return home.

Mayo Clinic remains No. 1

For the 2022-2023 rankings and ratings, U.S. News compared more than 4,500 medical centers across the country in 15 specialties and 20 procedures and conditions. Of these, 493 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals as a result of their overall strong performance.