User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

How 100 years of insulin have changed pregnancy for women with type 1 diabetes

Mark B. Landon, MD: The discovery of insulin in 1921 by Dr. Frederick Banting and Dr. Charles Best and its introduction into clinical practice may well be the most significant achievement in the care of pregnant women with diabetes mellitus in the last century. Why was this advance so monumental?

Steven G. Gabbe, MD: Insulin is the single most important drug we use in taking care of diabetes in pregnancy. It is required not only by all patients with type 1 diabetes, but also by the majority of patients with type 2 diabetes. Moreover, at least a third of our patients with gestational diabetes require more than lifestyle change. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Diabetes Association recommend that insulin be considered as the first-line pharmacologic therapy.

Before insulin, the most prudent option for women who had glucose in their urine early in pregnancy, which was called “true diabetes,” was deemed to be termination of the pregnancy. The chances of surviving a pregnancy, and of having a surviving infant, were low.

Pregnancies were a rarity to begin with because most women of reproductive age died within a year or two of the onset of their illness. Moreover, most women with what we now know as type 1 diabetes were amenorrheic and infertile. In fact, before insulin, there were few cases of pregnancy complicated by diabetes reported in the literature. A summary of the world literature published in 1909 in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences reported: 66 pregnancies in 43 women; 50% maternal mortality (27% immediate; 23% in next 2 years); and a 41% pregnancy loss (Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:295-9, Cited Am J Med Sci. 1909;137:1).

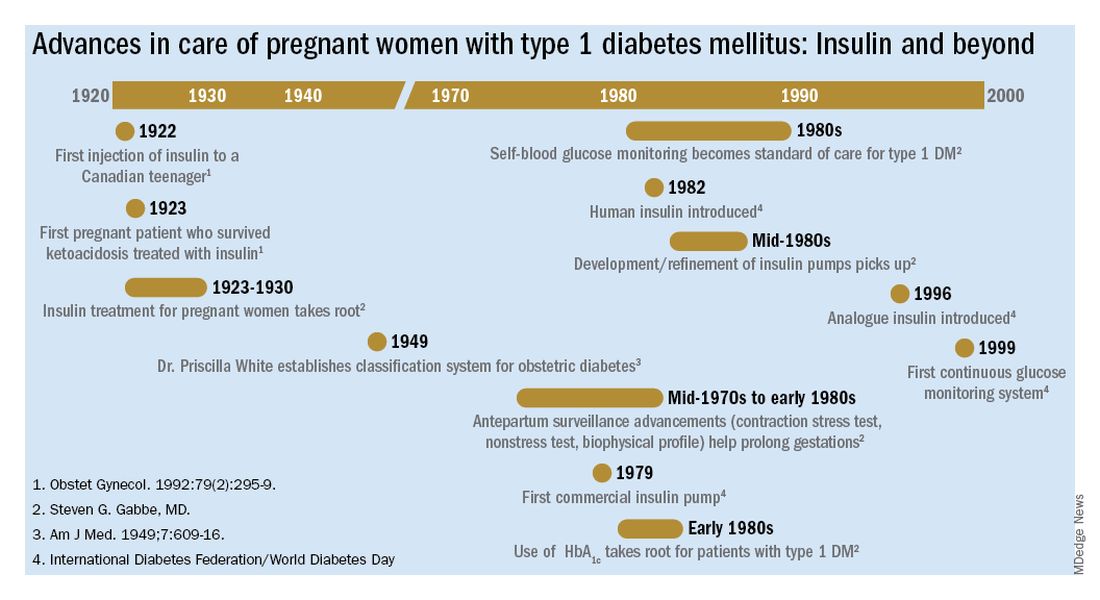

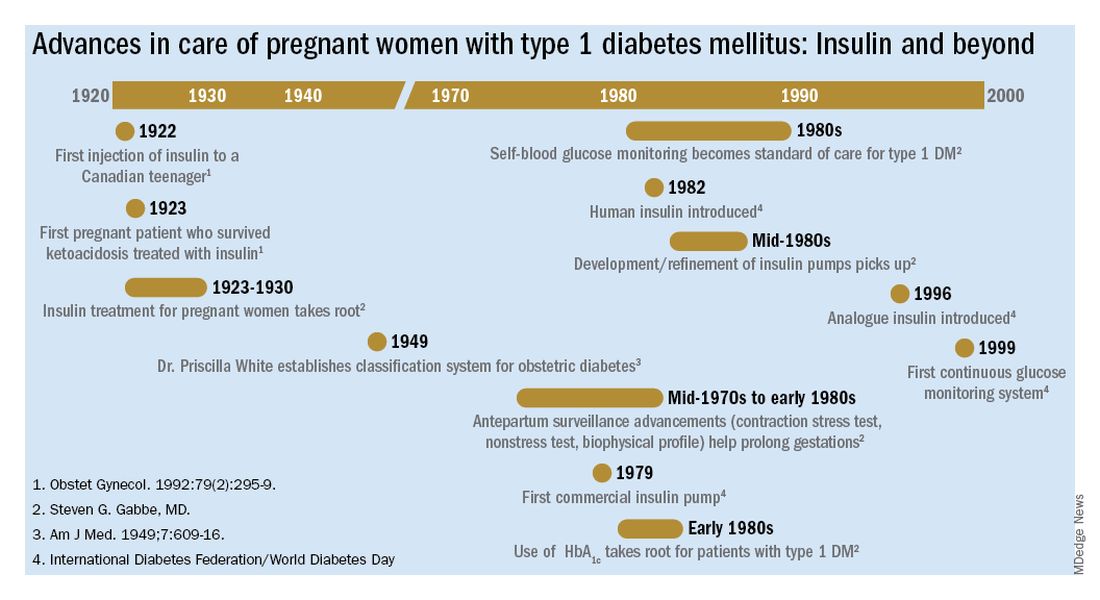

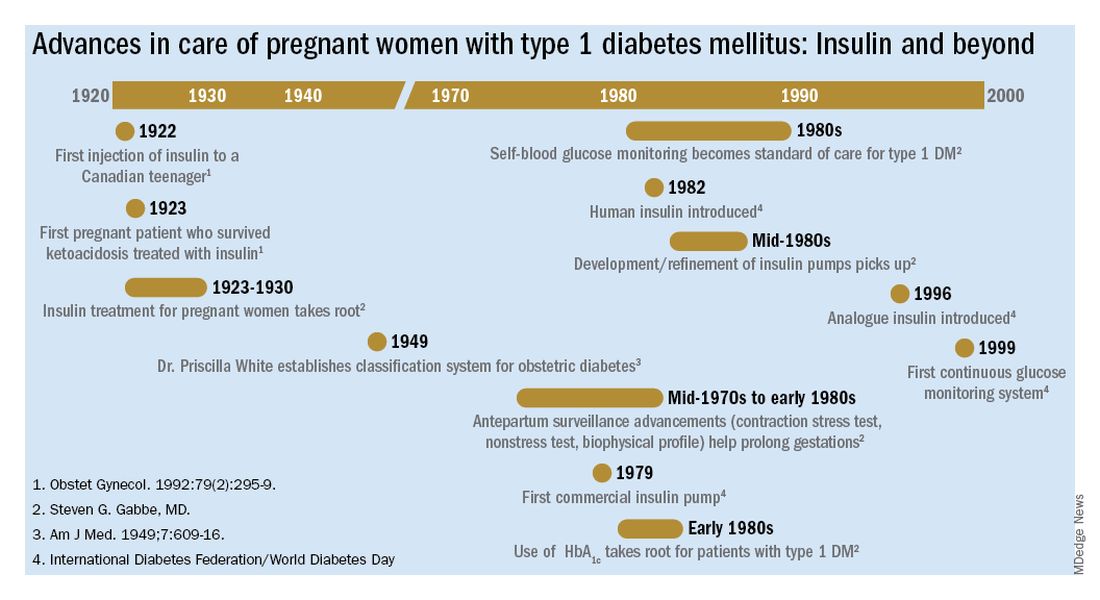

The first injection of insulin was administered in 1922 to a 13-year-old Canadian boy, and for several years the focus was on children. (Some of them had been kept alive with 450 calories/day long enough to benefit from the new treatment.)

For women with what we now know as type 1 diabetes, insulin kept them alive, restored their fertility, and enabled them to survive a pregnancy. Maternal mortality dropped dramatically, down to a few percent, once pregnant women became beneficiaries of insulin therapy.

Perinatal outcomes remained poor, however. In the early years of insulin therapy, more than half of the babies died. Some were stillbirths, which had been the primary cause of perinatal deaths in the pre-insulin era. Others were spontaneous preterm births, and still others were delivered prematurely in order to avert a stillbirth, and subsequently died.

Dr. Landon: A significant improvement in perinatal outcomes was eventually realized about two decades after insulin was introduced. By then Dr. Priscilla White of the Joslin Clinic had recorded that women who had so-called ‘normal hormonal balance’ – basically good glucose control – had very low rates of fetal demise and fetal loss compared with those who did not have good control. You had the opportunity to work alongside Dr. White. How did she achieve these results without all the tools we have today?

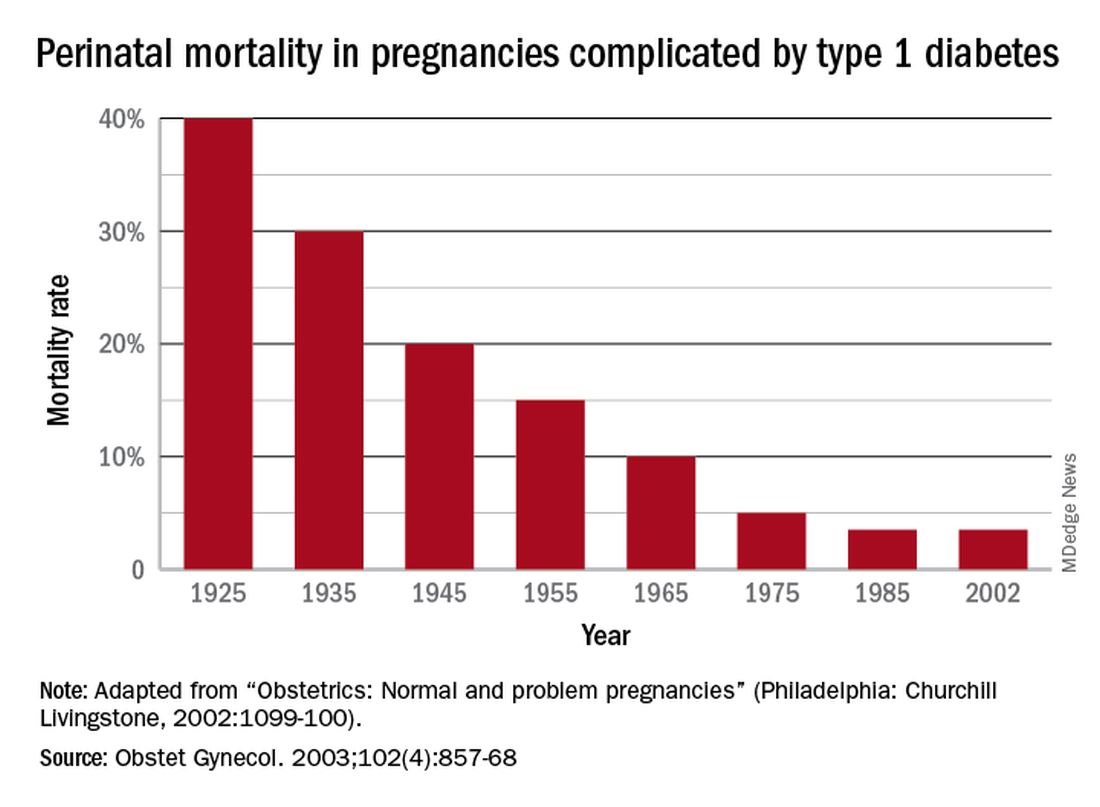

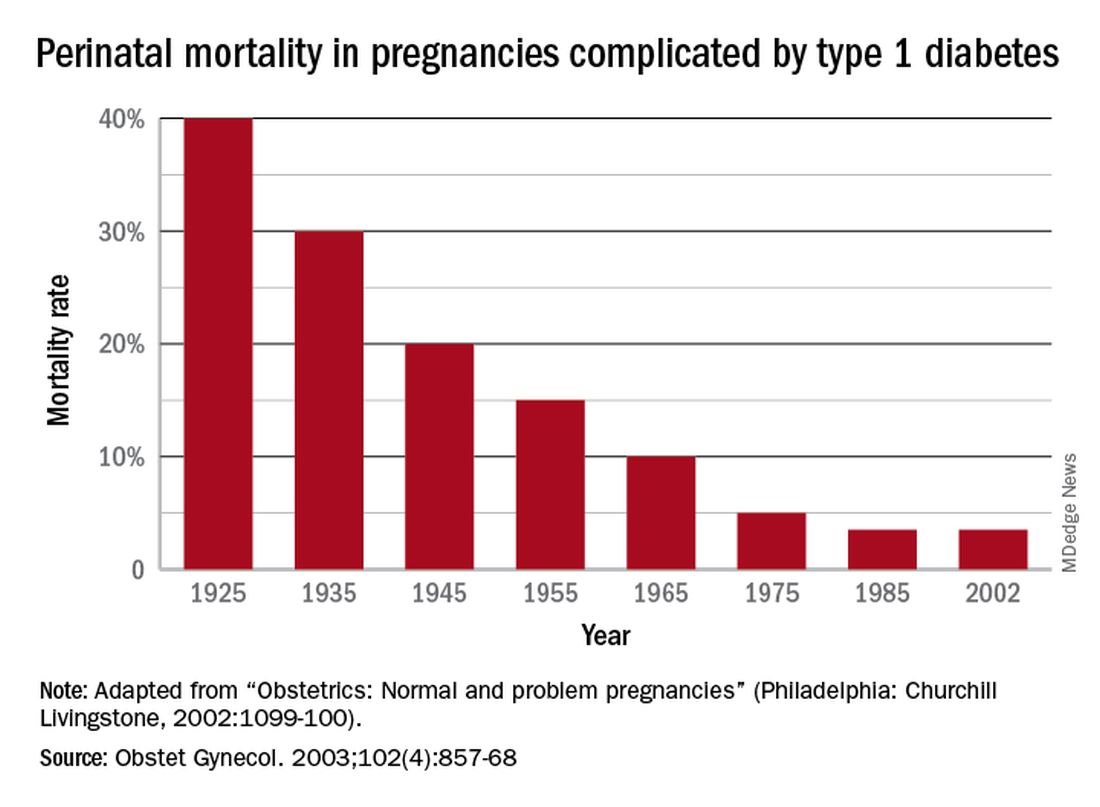

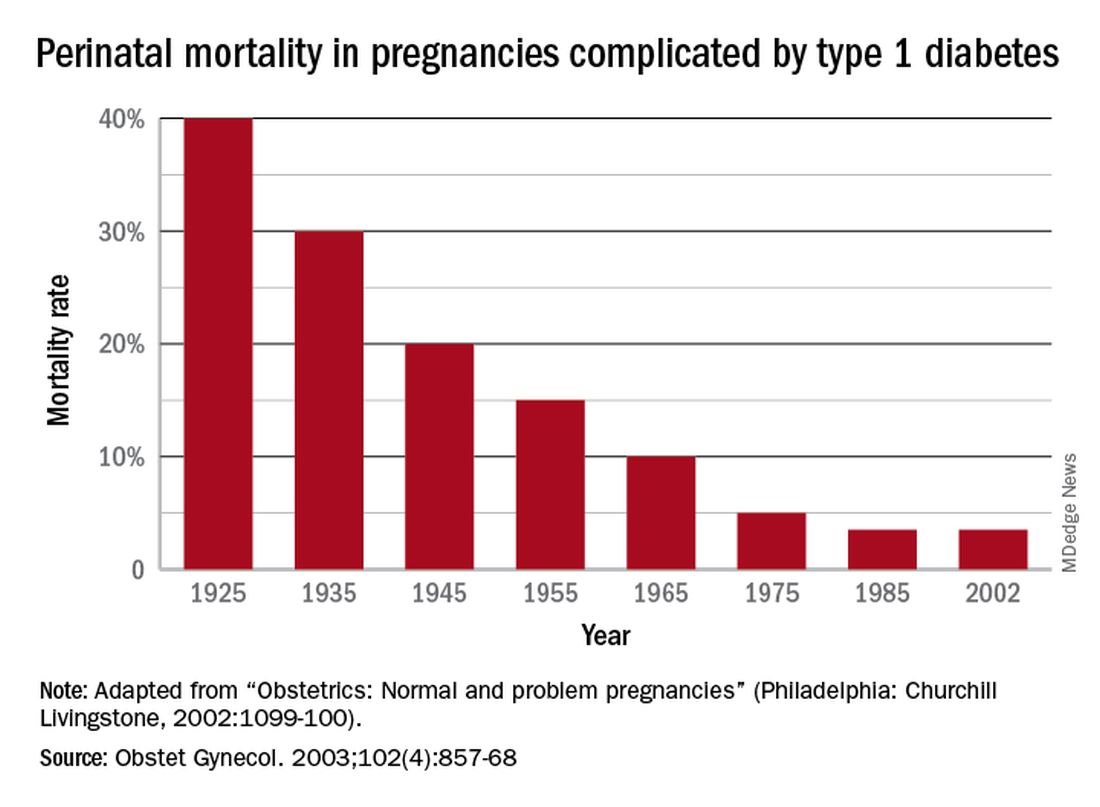

Dr. Gabbe: In 1925, the perinatal mortality in pregnancies complicated by type 1 diabetes was about 40%. By 1965 it was 10%, and when I began my residency at the Joslin Clinic and Boston Hospital for Women in 1972 it was closer to 5%

In those days we didn’t have accurate methods for dating pregnancies or assessing fetal size or well-being. We didn’t have tools to monitor blood glucose levels, and our insulins were limited to regular insulins and NPH (neutral protamine Hagedorn) as a basal insulin.

Dr. White had concluded early on, and wrote in a 1928 paper, that controlling diabetes was essential to fetal welfare and that the “high glucose content of placental blood” was probably linked to excessive fetal growth. She also wrote about the importance of “close and persistent supervision” of the patient by both an internist and obstetrician.

When I began working with her in the 1970s, her program involved antepartum visits every week or two and a team approach. Patients would be seen by Dr. White and other diabetologists, by head obstetrician Dr. Luke Gillespie, and by nurses and nutritionists. At the end of each day, after all the patients had been seen, we’d gather in Dr. White’s office and look at each patient’s single morning blood glucose measurement and the histories we’d obtained, and we’d make adjustments to their insulin regimens.

Dr. White’s solution to the problem of monitoring blood glucose was a program of hospitalization throughout pregnancy. Patients were hospitalized for a week initially to achieve blood glucose control, and then again around 20 weeks of gestation for monitoring and improvement. Hospitalizations later in the pregnancy were timed according to her classification of obstetric diabetes, which had been published in a landmark paper in 1949. In that paper Dr. Priscilla White wrote: “It is evident that age at onset of diabetes, duration, severity, and degree of maternal vascular disease all influence the fetal survival unfavorably”(Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:295-9 / Am J Med. 1949;7:609-16).

The classification system considered age of onset, duration of diabetes, need for insulin, and presence of vascular disease. Women in higher classes and at greater risk for intrauterine death were admitted at 32 weeks, while those at less risk could wait until about 34 weeks. The timing of delivery was somewhat arbitrary, but the goal was to choose a time at which the fetus could survive in the nursery and, as Dr. White had written, “before the dreaded late intrauterine accident could occur.” (In the early ’70s, approximately half of newborns admitted to [newborn intensive care unites] at 32 weeks would survive.)

We did measure estriol levels through 24-hour urine collections as a marker for fetal and placental well-being, but as we subsequently learned, a sharp drop was often too late an indicator that something was wrong.

Dr. Landon: Dr. White and others trying to manage diabetes in pregnancy during the initial decades after insulin’s discovery were indeed significantly handicapped by a lack of tools for assessing glucose control. However, the 1970s then ushered in a “Golden Era” of fetal testing. How did advances in antepartum fetal monitoring complement the use of insulin?

Dr. Gabbe: By the mid-1970s, researchers had recognized that fetal heart rate decelerations in labor signaled fetal hypoxemia, and Dr. Roger Freeman had applied these findings to the antepartum setting, pioneering development of the contraction stress test, or oxytocin stress test. The absence of late decelerations during 10 minutes of contractions meant that the fetus was unlikely to be compromised.

When the test was administered to high-risk patients at Los Angeles County Women’s Hospital, including women with diabetes, a negative result predicted that a baby would not die within the next week. The contraction stress test was a major breakthrough. It was the first biophysical test for fetal compromise and was important for pregnancies complicated by diabetes. However, it had to be done on the labor and delivery floor, it could take hours, and it might not be definitive if one couldn’t produce enough contractions.

In the mid-1970s, the nonstress test, which relied on the presence of fetal heart rate accelerations in response to fetal movement, was found to be as reliable as the contraction stress test. It became another important tool for prolonging gestation in women with type 1 diabetes.

Even more predictive and reliable was the biophysical profile described several years later. It combined the nonstress test with an assessment using real-time fetal ultrasound of fetal movements, fetal tone and breathing movements, and amniotic fluid.

So, in a relatively short period of time, antepartum surveillance progressed from the contraction stress test to the nonstress test to the biophysical profile. These advances, along with advances in neonatal intensive care, all contributed to the continued decline in perinatal mortality.

Dr. Landon: You have taught for many years that the principal benefit of these tests of fetal surveillance is not necessarily the results identifying a fetus at risk, but the reassuring normal results that allow further maturation of the fetus that is not at risk in the pregnancy complicated by type 1 diabetes.

You also taught – as I experienced some 40 years ago when training with you at the University of Pennsylvania – that hospitalization later in pregnancy allowed for valuable optimization of our patients’ insulin regimens prior to their scheduled deliveries. This optimization helped to reduce complications such as neonatal hypoglycemia.

The introduction of the first reflectance meters to the antepartum unit eliminated the need for so many blood draws. Subsequently, came portable self-monitoring blood glucose units, which I’d argue were the second greatest achievement after the introduction of insulin because they eliminated the need for routine antepartum admissions. What are your thoughts?

Dr. Gabbe: The reflectance meters as first developed were in-hospital devices. They needed frequent calibration, and readings took several minutes. Once introduced, however, there was rapid advancement in their accuracy, size, and speed of providing results.

Other important advances were the development of rapid-acting insulins and new basal insulins and, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the development of insulin pumps. At Penn, we studied an early pump that we called the “blue brick” because of its size. Today, of course, smaller and safer pumps paired with continuous glucose monitors are making an enormous difference for our patients with type 1 diabetes, providing them with much better outcomes.

Dr. Landon: A century after the discovery of insulin, congenital malformations remain a problem. We have seen a reduction overall, but recent data here and in Sweden show that the rate of malformations in pregnancy complicated by diabetes still is several-fold greater than in the general population.

The data also support what we’ve known for decades – that the level of glucose control during the periconceptual period is directly correlated with the risk of malformations. Can you speak to our efforts, which have been somewhat, but not completely, successful?

Dr. Gabbe: This is one of our remaining challenges. Malformations are now the leading cause of perinatal mortality in pregnancies involving type 1 and type 2 diabetes. We’ve seen these tragic outcomes over the years. While there were always questions about what caused malformations, our concerns focused on hyperglycemia early in pregnancy as a risk factor.

Knowing now that it is an abnormal intrauterine milieu during the period of organogenesis that leads to the malformations, we have improved by having patients come to us before pregnancy. Studies have shown that we can reduce malformations to a level comparable to the general population, or perhaps a bit higher, through intensive control as a result of prepregnancy care.

The challenge is that many obstetric patients don’t have a planned pregnancy. Our efforts to improve glucose control don’t always go the way we’d like them to. Still, considering where we’ve come from since the introduction of insulin to the modern management of diabetes in pregnancy, our progress has been truly remarkable.

Mark B. Landon, MD: The discovery of insulin in 1921 by Dr. Frederick Banting and Dr. Charles Best and its introduction into clinical practice may well be the most significant achievement in the care of pregnant women with diabetes mellitus in the last century. Why was this advance so monumental?

Steven G. Gabbe, MD: Insulin is the single most important drug we use in taking care of diabetes in pregnancy. It is required not only by all patients with type 1 diabetes, but also by the majority of patients with type 2 diabetes. Moreover, at least a third of our patients with gestational diabetes require more than lifestyle change. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Diabetes Association recommend that insulin be considered as the first-line pharmacologic therapy.

Before insulin, the most prudent option for women who had glucose in their urine early in pregnancy, which was called “true diabetes,” was deemed to be termination of the pregnancy. The chances of surviving a pregnancy, and of having a surviving infant, were low.

Pregnancies were a rarity to begin with because most women of reproductive age died within a year or two of the onset of their illness. Moreover, most women with what we now know as type 1 diabetes were amenorrheic and infertile. In fact, before insulin, there were few cases of pregnancy complicated by diabetes reported in the literature. A summary of the world literature published in 1909 in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences reported: 66 pregnancies in 43 women; 50% maternal mortality (27% immediate; 23% in next 2 years); and a 41% pregnancy loss (Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:295-9, Cited Am J Med Sci. 1909;137:1).

The first injection of insulin was administered in 1922 to a 13-year-old Canadian boy, and for several years the focus was on children. (Some of them had been kept alive with 450 calories/day long enough to benefit from the new treatment.)

For women with what we now know as type 1 diabetes, insulin kept them alive, restored their fertility, and enabled them to survive a pregnancy. Maternal mortality dropped dramatically, down to a few percent, once pregnant women became beneficiaries of insulin therapy.

Perinatal outcomes remained poor, however. In the early years of insulin therapy, more than half of the babies died. Some were stillbirths, which had been the primary cause of perinatal deaths in the pre-insulin era. Others were spontaneous preterm births, and still others were delivered prematurely in order to avert a stillbirth, and subsequently died.

Dr. Landon: A significant improvement in perinatal outcomes was eventually realized about two decades after insulin was introduced. By then Dr. Priscilla White of the Joslin Clinic had recorded that women who had so-called ‘normal hormonal balance’ – basically good glucose control – had very low rates of fetal demise and fetal loss compared with those who did not have good control. You had the opportunity to work alongside Dr. White. How did she achieve these results without all the tools we have today?

Dr. Gabbe: In 1925, the perinatal mortality in pregnancies complicated by type 1 diabetes was about 40%. By 1965 it was 10%, and when I began my residency at the Joslin Clinic and Boston Hospital for Women in 1972 it was closer to 5%

In those days we didn’t have accurate methods for dating pregnancies or assessing fetal size or well-being. We didn’t have tools to monitor blood glucose levels, and our insulins were limited to regular insulins and NPH (neutral protamine Hagedorn) as a basal insulin.

Dr. White had concluded early on, and wrote in a 1928 paper, that controlling diabetes was essential to fetal welfare and that the “high glucose content of placental blood” was probably linked to excessive fetal growth. She also wrote about the importance of “close and persistent supervision” of the patient by both an internist and obstetrician.

When I began working with her in the 1970s, her program involved antepartum visits every week or two and a team approach. Patients would be seen by Dr. White and other diabetologists, by head obstetrician Dr. Luke Gillespie, and by nurses and nutritionists. At the end of each day, after all the patients had been seen, we’d gather in Dr. White’s office and look at each patient’s single morning blood glucose measurement and the histories we’d obtained, and we’d make adjustments to their insulin regimens.

Dr. White’s solution to the problem of monitoring blood glucose was a program of hospitalization throughout pregnancy. Patients were hospitalized for a week initially to achieve blood glucose control, and then again around 20 weeks of gestation for monitoring and improvement. Hospitalizations later in the pregnancy were timed according to her classification of obstetric diabetes, which had been published in a landmark paper in 1949. In that paper Dr. Priscilla White wrote: “It is evident that age at onset of diabetes, duration, severity, and degree of maternal vascular disease all influence the fetal survival unfavorably”(Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:295-9 / Am J Med. 1949;7:609-16).

The classification system considered age of onset, duration of diabetes, need for insulin, and presence of vascular disease. Women in higher classes and at greater risk for intrauterine death were admitted at 32 weeks, while those at less risk could wait until about 34 weeks. The timing of delivery was somewhat arbitrary, but the goal was to choose a time at which the fetus could survive in the nursery and, as Dr. White had written, “before the dreaded late intrauterine accident could occur.” (In the early ’70s, approximately half of newborns admitted to [newborn intensive care unites] at 32 weeks would survive.)

We did measure estriol levels through 24-hour urine collections as a marker for fetal and placental well-being, but as we subsequently learned, a sharp drop was often too late an indicator that something was wrong.

Dr. Landon: Dr. White and others trying to manage diabetes in pregnancy during the initial decades after insulin’s discovery were indeed significantly handicapped by a lack of tools for assessing glucose control. However, the 1970s then ushered in a “Golden Era” of fetal testing. How did advances in antepartum fetal monitoring complement the use of insulin?

Dr. Gabbe: By the mid-1970s, researchers had recognized that fetal heart rate decelerations in labor signaled fetal hypoxemia, and Dr. Roger Freeman had applied these findings to the antepartum setting, pioneering development of the contraction stress test, or oxytocin stress test. The absence of late decelerations during 10 minutes of contractions meant that the fetus was unlikely to be compromised.

When the test was administered to high-risk patients at Los Angeles County Women’s Hospital, including women with diabetes, a negative result predicted that a baby would not die within the next week. The contraction stress test was a major breakthrough. It was the first biophysical test for fetal compromise and was important for pregnancies complicated by diabetes. However, it had to be done on the labor and delivery floor, it could take hours, and it might not be definitive if one couldn’t produce enough contractions.

In the mid-1970s, the nonstress test, which relied on the presence of fetal heart rate accelerations in response to fetal movement, was found to be as reliable as the contraction stress test. It became another important tool for prolonging gestation in women with type 1 diabetes.

Even more predictive and reliable was the biophysical profile described several years later. It combined the nonstress test with an assessment using real-time fetal ultrasound of fetal movements, fetal tone and breathing movements, and amniotic fluid.

So, in a relatively short period of time, antepartum surveillance progressed from the contraction stress test to the nonstress test to the biophysical profile. These advances, along with advances in neonatal intensive care, all contributed to the continued decline in perinatal mortality.

Dr. Landon: You have taught for many years that the principal benefit of these tests of fetal surveillance is not necessarily the results identifying a fetus at risk, but the reassuring normal results that allow further maturation of the fetus that is not at risk in the pregnancy complicated by type 1 diabetes.

You also taught – as I experienced some 40 years ago when training with you at the University of Pennsylvania – that hospitalization later in pregnancy allowed for valuable optimization of our patients’ insulin regimens prior to their scheduled deliveries. This optimization helped to reduce complications such as neonatal hypoglycemia.

The introduction of the first reflectance meters to the antepartum unit eliminated the need for so many blood draws. Subsequently, came portable self-monitoring blood glucose units, which I’d argue were the second greatest achievement after the introduction of insulin because they eliminated the need for routine antepartum admissions. What are your thoughts?

Dr. Gabbe: The reflectance meters as first developed were in-hospital devices. They needed frequent calibration, and readings took several minutes. Once introduced, however, there was rapid advancement in their accuracy, size, and speed of providing results.

Other important advances were the development of rapid-acting insulins and new basal insulins and, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the development of insulin pumps. At Penn, we studied an early pump that we called the “blue brick” because of its size. Today, of course, smaller and safer pumps paired with continuous glucose monitors are making an enormous difference for our patients with type 1 diabetes, providing them with much better outcomes.

Dr. Landon: A century after the discovery of insulin, congenital malformations remain a problem. We have seen a reduction overall, but recent data here and in Sweden show that the rate of malformations in pregnancy complicated by diabetes still is several-fold greater than in the general population.

The data also support what we’ve known for decades – that the level of glucose control during the periconceptual period is directly correlated with the risk of malformations. Can you speak to our efforts, which have been somewhat, but not completely, successful?

Dr. Gabbe: This is one of our remaining challenges. Malformations are now the leading cause of perinatal mortality in pregnancies involving type 1 and type 2 diabetes. We’ve seen these tragic outcomes over the years. While there were always questions about what caused malformations, our concerns focused on hyperglycemia early in pregnancy as a risk factor.

Knowing now that it is an abnormal intrauterine milieu during the period of organogenesis that leads to the malformations, we have improved by having patients come to us before pregnancy. Studies have shown that we can reduce malformations to a level comparable to the general population, or perhaps a bit higher, through intensive control as a result of prepregnancy care.

The challenge is that many obstetric patients don’t have a planned pregnancy. Our efforts to improve glucose control don’t always go the way we’d like them to. Still, considering where we’ve come from since the introduction of insulin to the modern management of diabetes in pregnancy, our progress has been truly remarkable.

Mark B. Landon, MD: The discovery of insulin in 1921 by Dr. Frederick Banting and Dr. Charles Best and its introduction into clinical practice may well be the most significant achievement in the care of pregnant women with diabetes mellitus in the last century. Why was this advance so monumental?

Steven G. Gabbe, MD: Insulin is the single most important drug we use in taking care of diabetes in pregnancy. It is required not only by all patients with type 1 diabetes, but also by the majority of patients with type 2 diabetes. Moreover, at least a third of our patients with gestational diabetes require more than lifestyle change. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Diabetes Association recommend that insulin be considered as the first-line pharmacologic therapy.

Before insulin, the most prudent option for women who had glucose in their urine early in pregnancy, which was called “true diabetes,” was deemed to be termination of the pregnancy. The chances of surviving a pregnancy, and of having a surviving infant, were low.

Pregnancies were a rarity to begin with because most women of reproductive age died within a year or two of the onset of their illness. Moreover, most women with what we now know as type 1 diabetes were amenorrheic and infertile. In fact, before insulin, there were few cases of pregnancy complicated by diabetes reported in the literature. A summary of the world literature published in 1909 in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences reported: 66 pregnancies in 43 women; 50% maternal mortality (27% immediate; 23% in next 2 years); and a 41% pregnancy loss (Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:295-9, Cited Am J Med Sci. 1909;137:1).

The first injection of insulin was administered in 1922 to a 13-year-old Canadian boy, and for several years the focus was on children. (Some of them had been kept alive with 450 calories/day long enough to benefit from the new treatment.)

For women with what we now know as type 1 diabetes, insulin kept them alive, restored their fertility, and enabled them to survive a pregnancy. Maternal mortality dropped dramatically, down to a few percent, once pregnant women became beneficiaries of insulin therapy.

Perinatal outcomes remained poor, however. In the early years of insulin therapy, more than half of the babies died. Some were stillbirths, which had been the primary cause of perinatal deaths in the pre-insulin era. Others were spontaneous preterm births, and still others were delivered prematurely in order to avert a stillbirth, and subsequently died.

Dr. Landon: A significant improvement in perinatal outcomes was eventually realized about two decades after insulin was introduced. By then Dr. Priscilla White of the Joslin Clinic had recorded that women who had so-called ‘normal hormonal balance’ – basically good glucose control – had very low rates of fetal demise and fetal loss compared with those who did not have good control. You had the opportunity to work alongside Dr. White. How did she achieve these results without all the tools we have today?

Dr. Gabbe: In 1925, the perinatal mortality in pregnancies complicated by type 1 diabetes was about 40%. By 1965 it was 10%, and when I began my residency at the Joslin Clinic and Boston Hospital for Women in 1972 it was closer to 5%

In those days we didn’t have accurate methods for dating pregnancies or assessing fetal size or well-being. We didn’t have tools to monitor blood glucose levels, and our insulins were limited to regular insulins and NPH (neutral protamine Hagedorn) as a basal insulin.

Dr. White had concluded early on, and wrote in a 1928 paper, that controlling diabetes was essential to fetal welfare and that the “high glucose content of placental blood” was probably linked to excessive fetal growth. She also wrote about the importance of “close and persistent supervision” of the patient by both an internist and obstetrician.

When I began working with her in the 1970s, her program involved antepartum visits every week or two and a team approach. Patients would be seen by Dr. White and other diabetologists, by head obstetrician Dr. Luke Gillespie, and by nurses and nutritionists. At the end of each day, after all the patients had been seen, we’d gather in Dr. White’s office and look at each patient’s single morning blood glucose measurement and the histories we’d obtained, and we’d make adjustments to their insulin regimens.

Dr. White’s solution to the problem of monitoring blood glucose was a program of hospitalization throughout pregnancy. Patients were hospitalized for a week initially to achieve blood glucose control, and then again around 20 weeks of gestation for monitoring and improvement. Hospitalizations later in the pregnancy were timed according to her classification of obstetric diabetes, which had been published in a landmark paper in 1949. In that paper Dr. Priscilla White wrote: “It is evident that age at onset of diabetes, duration, severity, and degree of maternal vascular disease all influence the fetal survival unfavorably”(Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:295-9 / Am J Med. 1949;7:609-16).

The classification system considered age of onset, duration of diabetes, need for insulin, and presence of vascular disease. Women in higher classes and at greater risk for intrauterine death were admitted at 32 weeks, while those at less risk could wait until about 34 weeks. The timing of delivery was somewhat arbitrary, but the goal was to choose a time at which the fetus could survive in the nursery and, as Dr. White had written, “before the dreaded late intrauterine accident could occur.” (In the early ’70s, approximately half of newborns admitted to [newborn intensive care unites] at 32 weeks would survive.)

We did measure estriol levels through 24-hour urine collections as a marker for fetal and placental well-being, but as we subsequently learned, a sharp drop was often too late an indicator that something was wrong.

Dr. Landon: Dr. White and others trying to manage diabetes in pregnancy during the initial decades after insulin’s discovery were indeed significantly handicapped by a lack of tools for assessing glucose control. However, the 1970s then ushered in a “Golden Era” of fetal testing. How did advances in antepartum fetal monitoring complement the use of insulin?

Dr. Gabbe: By the mid-1970s, researchers had recognized that fetal heart rate decelerations in labor signaled fetal hypoxemia, and Dr. Roger Freeman had applied these findings to the antepartum setting, pioneering development of the contraction stress test, or oxytocin stress test. The absence of late decelerations during 10 minutes of contractions meant that the fetus was unlikely to be compromised.

When the test was administered to high-risk patients at Los Angeles County Women’s Hospital, including women with diabetes, a negative result predicted that a baby would not die within the next week. The contraction stress test was a major breakthrough. It was the first biophysical test for fetal compromise and was important for pregnancies complicated by diabetes. However, it had to be done on the labor and delivery floor, it could take hours, and it might not be definitive if one couldn’t produce enough contractions.

In the mid-1970s, the nonstress test, which relied on the presence of fetal heart rate accelerations in response to fetal movement, was found to be as reliable as the contraction stress test. It became another important tool for prolonging gestation in women with type 1 diabetes.

Even more predictive and reliable was the biophysical profile described several years later. It combined the nonstress test with an assessment using real-time fetal ultrasound of fetal movements, fetal tone and breathing movements, and amniotic fluid.

So, in a relatively short period of time, antepartum surveillance progressed from the contraction stress test to the nonstress test to the biophysical profile. These advances, along with advances in neonatal intensive care, all contributed to the continued decline in perinatal mortality.

Dr. Landon: You have taught for many years that the principal benefit of these tests of fetal surveillance is not necessarily the results identifying a fetus at risk, but the reassuring normal results that allow further maturation of the fetus that is not at risk in the pregnancy complicated by type 1 diabetes.

You also taught – as I experienced some 40 years ago when training with you at the University of Pennsylvania – that hospitalization later in pregnancy allowed for valuable optimization of our patients’ insulin regimens prior to their scheduled deliveries. This optimization helped to reduce complications such as neonatal hypoglycemia.

The introduction of the first reflectance meters to the antepartum unit eliminated the need for so many blood draws. Subsequently, came portable self-monitoring blood glucose units, which I’d argue were the second greatest achievement after the introduction of insulin because they eliminated the need for routine antepartum admissions. What are your thoughts?

Dr. Gabbe: The reflectance meters as first developed were in-hospital devices. They needed frequent calibration, and readings took several minutes. Once introduced, however, there was rapid advancement in their accuracy, size, and speed of providing results.

Other important advances were the development of rapid-acting insulins and new basal insulins and, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the development of insulin pumps. At Penn, we studied an early pump that we called the “blue brick” because of its size. Today, of course, smaller and safer pumps paired with continuous glucose monitors are making an enormous difference for our patients with type 1 diabetes, providing them with much better outcomes.

Dr. Landon: A century after the discovery of insulin, congenital malformations remain a problem. We have seen a reduction overall, but recent data here and in Sweden show that the rate of malformations in pregnancy complicated by diabetes still is several-fold greater than in the general population.

The data also support what we’ve known for decades – that the level of glucose control during the periconceptual period is directly correlated with the risk of malformations. Can you speak to our efforts, which have been somewhat, but not completely, successful?

Dr. Gabbe: This is one of our remaining challenges. Malformations are now the leading cause of perinatal mortality in pregnancies involving type 1 and type 2 diabetes. We’ve seen these tragic outcomes over the years. While there were always questions about what caused malformations, our concerns focused on hyperglycemia early in pregnancy as a risk factor.

Knowing now that it is an abnormal intrauterine milieu during the period of organogenesis that leads to the malformations, we have improved by having patients come to us before pregnancy. Studies have shown that we can reduce malformations to a level comparable to the general population, or perhaps a bit higher, through intensive control as a result of prepregnancy care.

The challenge is that many obstetric patients don’t have a planned pregnancy. Our efforts to improve glucose control don’t always go the way we’d like them to. Still, considering where we’ve come from since the introduction of insulin to the modern management of diabetes in pregnancy, our progress has been truly remarkable.

Insulin in pregnancy: A look back at history for Diabetes Awareness Month

Each November, Diabetes Awareness Month, we commemorate the myriad advances that have made living with diabetes possible. This year is especially auspicious as it marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin by Frederick Banting, MD, and Charles Best, MD. The miracle of insulin cannot be overstated. In the preinsulin era, life expectancy after a diabetes diagnosis was 4-7 years for a 30-year-old patient. Within 3 years after the introduction of insulin, life expectancy after diagnosis jumped to about 17 years, a 167% increase.1

For ob.gyns. and their patients, insulin was a godsend. In the early 1920s, patients with pre-existing diabetes and pregnancy (recall that gestational diabetes mellitus would not be recognized as a unique condition until the 1960s)2 were advised to terminate the pregnancy; those who did not do so faced almost certain death for the fetus and, sometimes, themselves.3 By 1935, approximately 10 years after the introduction of insulin into practice, perinatal mortality dropped by 25%. By 1955, it had dropped by nearly 63%.4

The advent of technologies such as continuous glucose monitors, mobile phone–based health applications, and the artificial pancreas, have further transformed diabetes care.5 In addition, studies using animal models of diabetic pregnancy have revealed the molecular mechanisms responsible for hyperglycemia-induced birth defects – including alterations in lipid metabolism, excess generation of free radicals, and aberrant cell death – and uncovered potential strategies for prevention.6

To reflect on the herculean accomplishments in ob.gyn. since the discovery of insulin, we have invited two pillars of the diabetes in pregnancy research and clinical care communities: Steven G. Gabbe, MD, current professor of ob.gyn. at The Ohio State University (OSU) College of Medicine, former chair of ob.gyn. at OSU and University of Washington Medical Center, former senior vice president for health sciences and CEO of the OSU Medical Center, and former dean of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; and Mark B. Landon, MD, the Richard L. Meiling professor and chair of ob.gyn. at OSU.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Brostoff JM et al. Diabetologia. 2007;50(6):1351-3.

2. Panaitescu AM and Peltecu G. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2016;12(3):331-4.

3. Joslin EP. Boston Med Surg J 1915;173:841-9.

4. Gabbe SG and Graves CR. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):857-68.

5. Crimmins SD et al. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38(5):486-94.

6. Gabbay-Benziv R et al. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(3):481-8.

Each November, Diabetes Awareness Month, we commemorate the myriad advances that have made living with diabetes possible. This year is especially auspicious as it marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin by Frederick Banting, MD, and Charles Best, MD. The miracle of insulin cannot be overstated. In the preinsulin era, life expectancy after a diabetes diagnosis was 4-7 years for a 30-year-old patient. Within 3 years after the introduction of insulin, life expectancy after diagnosis jumped to about 17 years, a 167% increase.1

For ob.gyns. and their patients, insulin was a godsend. In the early 1920s, patients with pre-existing diabetes and pregnancy (recall that gestational diabetes mellitus would not be recognized as a unique condition until the 1960s)2 were advised to terminate the pregnancy; those who did not do so faced almost certain death for the fetus and, sometimes, themselves.3 By 1935, approximately 10 years after the introduction of insulin into practice, perinatal mortality dropped by 25%. By 1955, it had dropped by nearly 63%.4

The advent of technologies such as continuous glucose monitors, mobile phone–based health applications, and the artificial pancreas, have further transformed diabetes care.5 In addition, studies using animal models of diabetic pregnancy have revealed the molecular mechanisms responsible for hyperglycemia-induced birth defects – including alterations in lipid metabolism, excess generation of free radicals, and aberrant cell death – and uncovered potential strategies for prevention.6

To reflect on the herculean accomplishments in ob.gyn. since the discovery of insulin, we have invited two pillars of the diabetes in pregnancy research and clinical care communities: Steven G. Gabbe, MD, current professor of ob.gyn. at The Ohio State University (OSU) College of Medicine, former chair of ob.gyn. at OSU and University of Washington Medical Center, former senior vice president for health sciences and CEO of the OSU Medical Center, and former dean of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; and Mark B. Landon, MD, the Richard L. Meiling professor and chair of ob.gyn. at OSU.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Brostoff JM et al. Diabetologia. 2007;50(6):1351-3.

2. Panaitescu AM and Peltecu G. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2016;12(3):331-4.

3. Joslin EP. Boston Med Surg J 1915;173:841-9.

4. Gabbe SG and Graves CR. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):857-68.

5. Crimmins SD et al. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38(5):486-94.

6. Gabbay-Benziv R et al. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(3):481-8.

Each November, Diabetes Awareness Month, we commemorate the myriad advances that have made living with diabetes possible. This year is especially auspicious as it marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin by Frederick Banting, MD, and Charles Best, MD. The miracle of insulin cannot be overstated. In the preinsulin era, life expectancy after a diabetes diagnosis was 4-7 years for a 30-year-old patient. Within 3 years after the introduction of insulin, life expectancy after diagnosis jumped to about 17 years, a 167% increase.1

For ob.gyns. and their patients, insulin was a godsend. In the early 1920s, patients with pre-existing diabetes and pregnancy (recall that gestational diabetes mellitus would not be recognized as a unique condition until the 1960s)2 were advised to terminate the pregnancy; those who did not do so faced almost certain death for the fetus and, sometimes, themselves.3 By 1935, approximately 10 years after the introduction of insulin into practice, perinatal mortality dropped by 25%. By 1955, it had dropped by nearly 63%.4

The advent of technologies such as continuous glucose monitors, mobile phone–based health applications, and the artificial pancreas, have further transformed diabetes care.5 In addition, studies using animal models of diabetic pregnancy have revealed the molecular mechanisms responsible for hyperglycemia-induced birth defects – including alterations in lipid metabolism, excess generation of free radicals, and aberrant cell death – and uncovered potential strategies for prevention.6

To reflect on the herculean accomplishments in ob.gyn. since the discovery of insulin, we have invited two pillars of the diabetes in pregnancy research and clinical care communities: Steven G. Gabbe, MD, current professor of ob.gyn. at The Ohio State University (OSU) College of Medicine, former chair of ob.gyn. at OSU and University of Washington Medical Center, former senior vice president for health sciences and CEO of the OSU Medical Center, and former dean of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; and Mark B. Landon, MD, the Richard L. Meiling professor and chair of ob.gyn. at OSU.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Brostoff JM et al. Diabetologia. 2007;50(6):1351-3.

2. Panaitescu AM and Peltecu G. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2016;12(3):331-4.

3. Joslin EP. Boston Med Surg J 1915;173:841-9.

4. Gabbe SG and Graves CR. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):857-68.

5. Crimmins SD et al. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38(5):486-94.

6. Gabbay-Benziv R et al. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(3):481-8.

Your patient’s medication label lacks human safety information: What now?

Nearly 9 in 10 U.S. women take a medication at some point in their pregnancy, with approximately 50% of women taking at least one prescription medication.1 These medications may be prescribed without the benefit of knowledge gained through clinical trials. Knowledge is gained after market, often after multiple years, and potentially following widespread use. The situation is similar for vaccines, as was recently seen with the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. Early in the pandemic, evidence emerged that pregnancy increased the risk for severe illness from COVID-19, yet pregnant people and their providers were forced to make a difficult decision of risk/benefit with little data to guide them.

The FDA product label provides a summary and narrative of animal and human safety studies relating to pregnancy. But what if that label contains little to no information, or reports studies with conflicting results? Perhaps the product is new on the market or is infrequently used during pregnancy. Regardless, health care providers and pregnant patients still need to make decisions about medication use. The following list outlines information that can be found, and strategies to support providers and patients in making informed choices for a treatment plan.

Taking stock of the available information:

- If possible, connect with the specialist who prescribed the patient’s medication in question. They may have already assembled information regarding use of that medication in pregnancy.

- The sponsor may have published useful information from the phase 3 trials, including the outcomes of enrolled patients who inadvertently became pregnant.

- Review the animal data in the product label. Regulators require the careful selection of animal models, and this data can present a source of adjunct information regarding the medication’s effects on pregnancy, reproduction, and development. Negative results can be as revealing as positive results.

- Pharmacologic data in the label can also be informative. Although most labels have pharmacologic data based on trials in healthy nonpregnant individuals, understanding pregnancy physiology and the patient’s preexisting or pregnancy-specific condition(s) can provide insights.2 Close patient monitoring and follow-up are of key importance.

- Consider viable alternatives that may address the patient’s needs. There may be effective alternatives that have been better studied and shown to have low reproductive toxicity.

- Consider the risks to the patient as well as the developing fetus if the preexisting or pregnancy-specific condition is uncontrolled.

- Consult a teratogen specialist who can provide information to both patients and health care providers on the reproductive hazards or safety of many exposures, even those with limited data regarding use in pregnancy. For example, MotherToBaby provides a network of teratogen specialists.

Understanding perceptions of risk, decision-making, and strategies to support informed choices:

- Perceptions of risk: Each person perceives risk and benefit differently. The few studies that have attempted to investigate perception of teratogenic risk have found that many pregnant people overestimate the magnitude of teratogenic risk associated with a particular exposure.3 Alternatively, a medication’s benefit in controlling the maternal condition is often not considered sufficiently. Health care providers may have their own distorted perceptions of risk, even in the presence of evidence.

- Decision-making: Most teratogen data inherently involve uncertainty; it is rare to have completely nonconflicting data with which to make a decision. This makes decisions about whether or not to utilize a particular medication or other agent in pregnancy very difficult. For example, a patient would prefer to be told a black and white answer such as vaccines are either 100% safe or 100% harmful. However, no medical treatment is held to that standard of certainty. Even though it may be more comfortable to avoid an action and “just let things happen,” the lack of a decision is still a decision. The decision to not take medication may have risks inherent in not treating a condition and may result in adverse outcomes in the developing fetus. Lastly, presenting teratogen information often involves challenges in portraying and interpreting numerical risk. For example, when considering data presented in fraction format, patients and some health care providers may focus on the numerator or count of adverse events, while ignoring the magnitude of the denominator.

- Strategies: Health literacy “best practice” strategies are useful whether there is a lot of data or very little. These include the of use plain language and messages delivered in a clear and respectful voice, the use of visual aids, and the use effective teaching methods such as asking open-ended questions to assess understanding. Other strategies include using caution in framing information: for example, discussing a 1% increase in risk for a baby to have a medication-associated birth defect should also be presented as a 99% chance the medication will not cause a birth defect. Numeracy challenges can also be addressed by using natural numbers rather than fractions or percentages: for example, if there were 100 women in this room, one would have a baby with a birth defect after taking this medication in pregnancy, but 99 of these women would not.

In today’s medical world, shared decision-making is the preferred approach to choices. Communicating and appropriately utilizing information to make choices about medication safety in pregnancy are vital undertakings. An important provider responsibility is helping patients understand that science is built on evidence that amasses and changes over time and that it represents rich shades of gray rather than “black and white” options.

Contributing to evidence: A pregnancy exposure registry is a study that collects health information from women who take prescription medicines or vaccines when they are pregnant. Information is also collected on the neonate. This information is compared with women who have not taken medicine during pregnancy. Enrolling in a pregnancy exposure registry can help improve safety information for medication used during pregnancy and can be used to update drug labeling. Please consult the Food and Drug Administration listing below to learn if there is an ongoing registry for the patient’s medication in question. If there is and the patient is eligible, provide her with the information. If she is interested and willing, help her enroll. It’s a great step toward building the scientific evidence on medication safety in pregnancy.

For further information about health literacy, consult:

https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/meds/treatingfortwo/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/index.html

https://mothertobaby.org

The MotherToBaby web page has hundreds of fact sheets written in a way that patients can understand, and available in English and Spanish. MotherToBaby coordinates research studies on specific agents. The toll-free number is 866-626-6847.

For a listing of pregnancy registries, consult:

https://www.fda.gov/science-research/womens-health-research/pregnancy-registries

Dr. Hardy is executive director, head of pharmacoepidemiology, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. She serves as a member of Council for the Society for Birth Defects Research and Prevention (BDRP), represents the BDRP on the Coalition to Advance Maternal Therapeutics, and is a member of the North American Board for Amandla Development, South Africa. Dr. Conover is the director of Nebraska MotherToBaby. She is assistant professor at the Munroe Meyer Institute, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

References

1. Mitchell AA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):51:e1-e8.

2. Feghali M et al. Semin Perinatol 2015;39:512-9.

3. Conover EA, Polifka JE. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 2011;157:227-33.

Nearly 9 in 10 U.S. women take a medication at some point in their pregnancy, with approximately 50% of women taking at least one prescription medication.1 These medications may be prescribed without the benefit of knowledge gained through clinical trials. Knowledge is gained after market, often after multiple years, and potentially following widespread use. The situation is similar for vaccines, as was recently seen with the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. Early in the pandemic, evidence emerged that pregnancy increased the risk for severe illness from COVID-19, yet pregnant people and their providers were forced to make a difficult decision of risk/benefit with little data to guide them.

The FDA product label provides a summary and narrative of animal and human safety studies relating to pregnancy. But what if that label contains little to no information, or reports studies with conflicting results? Perhaps the product is new on the market or is infrequently used during pregnancy. Regardless, health care providers and pregnant patients still need to make decisions about medication use. The following list outlines information that can be found, and strategies to support providers and patients in making informed choices for a treatment plan.

Taking stock of the available information:

- If possible, connect with the specialist who prescribed the patient’s medication in question. They may have already assembled information regarding use of that medication in pregnancy.

- The sponsor may have published useful information from the phase 3 trials, including the outcomes of enrolled patients who inadvertently became pregnant.

- Review the animal data in the product label. Regulators require the careful selection of animal models, and this data can present a source of adjunct information regarding the medication’s effects on pregnancy, reproduction, and development. Negative results can be as revealing as positive results.

- Pharmacologic data in the label can also be informative. Although most labels have pharmacologic data based on trials in healthy nonpregnant individuals, understanding pregnancy physiology and the patient’s preexisting or pregnancy-specific condition(s) can provide insights.2 Close patient monitoring and follow-up are of key importance.

- Consider viable alternatives that may address the patient’s needs. There may be effective alternatives that have been better studied and shown to have low reproductive toxicity.

- Consider the risks to the patient as well as the developing fetus if the preexisting or pregnancy-specific condition is uncontrolled.

- Consult a teratogen specialist who can provide information to both patients and health care providers on the reproductive hazards or safety of many exposures, even those with limited data regarding use in pregnancy. For example, MotherToBaby provides a network of teratogen specialists.

Understanding perceptions of risk, decision-making, and strategies to support informed choices:

- Perceptions of risk: Each person perceives risk and benefit differently. The few studies that have attempted to investigate perception of teratogenic risk have found that many pregnant people overestimate the magnitude of teratogenic risk associated with a particular exposure.3 Alternatively, a medication’s benefit in controlling the maternal condition is often not considered sufficiently. Health care providers may have their own distorted perceptions of risk, even in the presence of evidence.

- Decision-making: Most teratogen data inherently involve uncertainty; it is rare to have completely nonconflicting data with which to make a decision. This makes decisions about whether or not to utilize a particular medication or other agent in pregnancy very difficult. For example, a patient would prefer to be told a black and white answer such as vaccines are either 100% safe or 100% harmful. However, no medical treatment is held to that standard of certainty. Even though it may be more comfortable to avoid an action and “just let things happen,” the lack of a decision is still a decision. The decision to not take medication may have risks inherent in not treating a condition and may result in adverse outcomes in the developing fetus. Lastly, presenting teratogen information often involves challenges in portraying and interpreting numerical risk. For example, when considering data presented in fraction format, patients and some health care providers may focus on the numerator or count of adverse events, while ignoring the magnitude of the denominator.

- Strategies: Health literacy “best practice” strategies are useful whether there is a lot of data or very little. These include the of use plain language and messages delivered in a clear and respectful voice, the use of visual aids, and the use effective teaching methods such as asking open-ended questions to assess understanding. Other strategies include using caution in framing information: for example, discussing a 1% increase in risk for a baby to have a medication-associated birth defect should also be presented as a 99% chance the medication will not cause a birth defect. Numeracy challenges can also be addressed by using natural numbers rather than fractions or percentages: for example, if there were 100 women in this room, one would have a baby with a birth defect after taking this medication in pregnancy, but 99 of these women would not.

In today’s medical world, shared decision-making is the preferred approach to choices. Communicating and appropriately utilizing information to make choices about medication safety in pregnancy are vital undertakings. An important provider responsibility is helping patients understand that science is built on evidence that amasses and changes over time and that it represents rich shades of gray rather than “black and white” options.

Contributing to evidence: A pregnancy exposure registry is a study that collects health information from women who take prescription medicines or vaccines when they are pregnant. Information is also collected on the neonate. This information is compared with women who have not taken medicine during pregnancy. Enrolling in a pregnancy exposure registry can help improve safety information for medication used during pregnancy and can be used to update drug labeling. Please consult the Food and Drug Administration listing below to learn if there is an ongoing registry for the patient’s medication in question. If there is and the patient is eligible, provide her with the information. If she is interested and willing, help her enroll. It’s a great step toward building the scientific evidence on medication safety in pregnancy.

For further information about health literacy, consult:

https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/meds/treatingfortwo/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/index.html

https://mothertobaby.org

The MotherToBaby web page has hundreds of fact sheets written in a way that patients can understand, and available in English and Spanish. MotherToBaby coordinates research studies on specific agents. The toll-free number is 866-626-6847.

For a listing of pregnancy registries, consult:

https://www.fda.gov/science-research/womens-health-research/pregnancy-registries

Dr. Hardy is executive director, head of pharmacoepidemiology, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. She serves as a member of Council for the Society for Birth Defects Research and Prevention (BDRP), represents the BDRP on the Coalition to Advance Maternal Therapeutics, and is a member of the North American Board for Amandla Development, South Africa. Dr. Conover is the director of Nebraska MotherToBaby. She is assistant professor at the Munroe Meyer Institute, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

References

1. Mitchell AA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):51:e1-e8.

2. Feghali M et al. Semin Perinatol 2015;39:512-9.

3. Conover EA, Polifka JE. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 2011;157:227-33.

Nearly 9 in 10 U.S. women take a medication at some point in their pregnancy, with approximately 50% of women taking at least one prescription medication.1 These medications may be prescribed without the benefit of knowledge gained through clinical trials. Knowledge is gained after market, often after multiple years, and potentially following widespread use. The situation is similar for vaccines, as was recently seen with the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. Early in the pandemic, evidence emerged that pregnancy increased the risk for severe illness from COVID-19, yet pregnant people and their providers were forced to make a difficult decision of risk/benefit with little data to guide them.

The FDA product label provides a summary and narrative of animal and human safety studies relating to pregnancy. But what if that label contains little to no information, or reports studies with conflicting results? Perhaps the product is new on the market or is infrequently used during pregnancy. Regardless, health care providers and pregnant patients still need to make decisions about medication use. The following list outlines information that can be found, and strategies to support providers and patients in making informed choices for a treatment plan.

Taking stock of the available information:

- If possible, connect with the specialist who prescribed the patient’s medication in question. They may have already assembled information regarding use of that medication in pregnancy.

- The sponsor may have published useful information from the phase 3 trials, including the outcomes of enrolled patients who inadvertently became pregnant.

- Review the animal data in the product label. Regulators require the careful selection of animal models, and this data can present a source of adjunct information regarding the medication’s effects on pregnancy, reproduction, and development. Negative results can be as revealing as positive results.

- Pharmacologic data in the label can also be informative. Although most labels have pharmacologic data based on trials in healthy nonpregnant individuals, understanding pregnancy physiology and the patient’s preexisting or pregnancy-specific condition(s) can provide insights.2 Close patient monitoring and follow-up are of key importance.

- Consider viable alternatives that may address the patient’s needs. There may be effective alternatives that have been better studied and shown to have low reproductive toxicity.

- Consider the risks to the patient as well as the developing fetus if the preexisting or pregnancy-specific condition is uncontrolled.

- Consult a teratogen specialist who can provide information to both patients and health care providers on the reproductive hazards or safety of many exposures, even those with limited data regarding use in pregnancy. For example, MotherToBaby provides a network of teratogen specialists.

Understanding perceptions of risk, decision-making, and strategies to support informed choices:

- Perceptions of risk: Each person perceives risk and benefit differently. The few studies that have attempted to investigate perception of teratogenic risk have found that many pregnant people overestimate the magnitude of teratogenic risk associated with a particular exposure.3 Alternatively, a medication’s benefit in controlling the maternal condition is often not considered sufficiently. Health care providers may have their own distorted perceptions of risk, even in the presence of evidence.

- Decision-making: Most teratogen data inherently involve uncertainty; it is rare to have completely nonconflicting data with which to make a decision. This makes decisions about whether or not to utilize a particular medication or other agent in pregnancy very difficult. For example, a patient would prefer to be told a black and white answer such as vaccines are either 100% safe or 100% harmful. However, no medical treatment is held to that standard of certainty. Even though it may be more comfortable to avoid an action and “just let things happen,” the lack of a decision is still a decision. The decision to not take medication may have risks inherent in not treating a condition and may result in adverse outcomes in the developing fetus. Lastly, presenting teratogen information often involves challenges in portraying and interpreting numerical risk. For example, when considering data presented in fraction format, patients and some health care providers may focus on the numerator or count of adverse events, while ignoring the magnitude of the denominator.

- Strategies: Health literacy “best practice” strategies are useful whether there is a lot of data or very little. These include the of use plain language and messages delivered in a clear and respectful voice, the use of visual aids, and the use effective teaching methods such as asking open-ended questions to assess understanding. Other strategies include using caution in framing information: for example, discussing a 1% increase in risk for a baby to have a medication-associated birth defect should also be presented as a 99% chance the medication will not cause a birth defect. Numeracy challenges can also be addressed by using natural numbers rather than fractions or percentages: for example, if there were 100 women in this room, one would have a baby with a birth defect after taking this medication in pregnancy, but 99 of these women would not.

In today’s medical world, shared decision-making is the preferred approach to choices. Communicating and appropriately utilizing information to make choices about medication safety in pregnancy are vital undertakings. An important provider responsibility is helping patients understand that science is built on evidence that amasses and changes over time and that it represents rich shades of gray rather than “black and white” options.

Contributing to evidence: A pregnancy exposure registry is a study that collects health information from women who take prescription medicines or vaccines when they are pregnant. Information is also collected on the neonate. This information is compared with women who have not taken medicine during pregnancy. Enrolling in a pregnancy exposure registry can help improve safety information for medication used during pregnancy and can be used to update drug labeling. Please consult the Food and Drug Administration listing below to learn if there is an ongoing registry for the patient’s medication in question. If there is and the patient is eligible, provide her with the information. If she is interested and willing, help her enroll. It’s a great step toward building the scientific evidence on medication safety in pregnancy.

For further information about health literacy, consult:

https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/meds/treatingfortwo/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/index.html

https://mothertobaby.org

The MotherToBaby web page has hundreds of fact sheets written in a way that patients can understand, and available in English and Spanish. MotherToBaby coordinates research studies on specific agents. The toll-free number is 866-626-6847.

For a listing of pregnancy registries, consult:

https://www.fda.gov/science-research/womens-health-research/pregnancy-registries

Dr. Hardy is executive director, head of pharmacoepidemiology, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. She serves as a member of Council for the Society for Birth Defects Research and Prevention (BDRP), represents the BDRP on the Coalition to Advance Maternal Therapeutics, and is a member of the North American Board for Amandla Development, South Africa. Dr. Conover is the director of Nebraska MotherToBaby. She is assistant professor at the Munroe Meyer Institute, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

References

1. Mitchell AA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):51:e1-e8.

2. Feghali M et al. Semin Perinatol 2015;39:512-9.

3. Conover EA, Polifka JE. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 2011;157:227-33.

Overview of guidelines for patients seeking gender-affirmation surgery

Gender-affirmation surgery refers to a collection of procedures by which a transgender individual physically alters characteristics to align with their gender identity. While not all patients who identify as transgender will choose to undergo surgery, the surgeries are considered medically necessary and lead to significant improvements in emotional and psychological well-being.1 With increasing insurance coverage and improved access to care, more and more patients are seeking gender-affirming surgery, and it is incumbent for providers to familiarize themselves with preoperative recommendations and requirements.

Ob.gyns. play a key role in patients seeking surgical treatment as patients may inquire about available procedures and what steps are necessary prior to scheduling a visit with the appropriate surgeon. The World Professional Association of Transgender Health has established standards of care that provide multidisciplinary, evidence-based guidance for patients seeking a variety of gender-affirming services ranging from mental health, hormone therapy, and surgery.

Basic preoperative surgical prerequisites set forth by WPATH include being a patient with well-documented gender dysphoria, being the age of majority, and having the ability to provide informed consent.1

As with any surgical candidate, it is also equally important for a patient to have well-controlled medical and psychiatric comorbidities, which should also include smoking cessation. A variety of surgical procedures are available to patients and include breast/chest surgery, genital (bottom) surgery, and nongenital surgery (facial feminization, pectoral implant placement, thyroid chondroplasty, lipofilling/liposuction, body contouring, and voice modification). Patients may choose to undergo chest/breast surgery and/or bottom surgery or forgo surgical procedures altogether.

For transmasculine patients, breast/chest surgery, otherwise known as top surgery, is the most common and desired procedure. According to a recent survey, approximately 97% of transmasculine patients had or wanted masculinizing chest surgery.2 In addition to patients meeting the basic requirements set forth by WPATH, one referral from a mental health provider specializing in gender-affirming care is also needed prior to this procedure. It is also important to note that testosterone use is no longer a needed prior to masculinizing chest surgery.

Transmasculine bottom surgery, which includes hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, vaginectomy, scrotoplasty, testicular implant placement, and/or phalloplasty have additional nuances. Compared with transmasculine individuals seeking top surgery, the number of patients who have had or desire metoidioplasty and phalloplasty is much lower, which is mainly because of the high complication rates of these procedures. In the same survey, only 4% of patients had undergone a metoidioplasty procedure and 2% of patients had undergone a phalloplasty.2

In evaluating rates of hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy, approximately 21% of transgender men underwent hysterectomy, with 58% desiring it in the future.2 Unlike patients pursuing top surgery, patients who desire any form of bottom surgery need to be on 12 months of continuous hormone therapy.1 They also must provide two letters from two different mental health providers, one of whom must have either an MD/DO or PhD. In cases in which a patient requests a hysterectomy for reasons other than gender dysphoria, such as pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding, these criteria do not apply.

For transfeminine individuals, augmentation mammoplasty is performed following 12 months of continuous hormone therapy. This is to allow maximum breast growth, which occurs approximately 2-3 months after hormone initiation and peaks at 1-2 years.3 Rates of transfeminine individuals seeking augmentation mammoplasty is similar to that of their transmasculine counterparts at 74%.2 One referral letter from a mental health provider is also needed prior to augmentation mammoplasty.

Transfeminine patients who desire bottom surgery, which can involve an orchiectomy or vaginoplasty (single-stage penile inversion, peritoneal, or colonic interposition), have the same additional requirements as transmasculine individuals seeking bottom surgery. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that 25% of transfeminine individuals had already undergone orchiectomy and 87% had either undergone or desired a vaginoplasty in the future.2 This is in stark contrast to transmasculine patients and rates of bottom surgery.

Unless there is a specific medical contraindication to hormone therapy, emphasis is placed on 12 months of continuous hormone usage. Additional emphasis is placed on patients seeking bottom surgery to live for a minimum of 12 months in their congruent gender role. This also allows patients to further explore their gender identity and make appropriate preparations for surgery.

As with any surgical procedure, obtaining informed consent and reviewing patient expectations are key. In my clinical practice, I discuss with patients that the general surgical goals are to achieve both function and good aesthetic outcome but that their results are also tailored to their individual bodies. Assessing a patient’s support system and social factors is also equally important in the preoperative planning period. As this field continues to grow, it is essential for providers to understand the evolving distinctions in surgical care to improve access to patients.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa. She has no conflicts. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc.

2. James SE et al. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender survey. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016.

3. Thomas TN. Overview of surgery for transgender patients, in “Comprehensive care for the transgender patient.” Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020. pp. 48-53.

Gender-affirmation surgery refers to a collection of procedures by which a transgender individual physically alters characteristics to align with their gender identity. While not all patients who identify as transgender will choose to undergo surgery, the surgeries are considered medically necessary and lead to significant improvements in emotional and psychological well-being.1 With increasing insurance coverage and improved access to care, more and more patients are seeking gender-affirming surgery, and it is incumbent for providers to familiarize themselves with preoperative recommendations and requirements.

Ob.gyns. play a key role in patients seeking surgical treatment as patients may inquire about available procedures and what steps are necessary prior to scheduling a visit with the appropriate surgeon. The World Professional Association of Transgender Health has established standards of care that provide multidisciplinary, evidence-based guidance for patients seeking a variety of gender-affirming services ranging from mental health, hormone therapy, and surgery.

Basic preoperative surgical prerequisites set forth by WPATH include being a patient with well-documented gender dysphoria, being the age of majority, and having the ability to provide informed consent.1

As with any surgical candidate, it is also equally important for a patient to have well-controlled medical and psychiatric comorbidities, which should also include smoking cessation. A variety of surgical procedures are available to patients and include breast/chest surgery, genital (bottom) surgery, and nongenital surgery (facial feminization, pectoral implant placement, thyroid chondroplasty, lipofilling/liposuction, body contouring, and voice modification). Patients may choose to undergo chest/breast surgery and/or bottom surgery or forgo surgical procedures altogether.

For transmasculine patients, breast/chest surgery, otherwise known as top surgery, is the most common and desired procedure. According to a recent survey, approximately 97% of transmasculine patients had or wanted masculinizing chest surgery.2 In addition to patients meeting the basic requirements set forth by WPATH, one referral from a mental health provider specializing in gender-affirming care is also needed prior to this procedure. It is also important to note that testosterone use is no longer a needed prior to masculinizing chest surgery.

Transmasculine bottom surgery, which includes hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty, vaginectomy, scrotoplasty, testicular implant placement, and/or phalloplasty have additional nuances. Compared with transmasculine individuals seeking top surgery, the number of patients who have had or desire metoidioplasty and phalloplasty is much lower, which is mainly because of the high complication rates of these procedures. In the same survey, only 4% of patients had undergone a metoidioplasty procedure and 2% of patients had undergone a phalloplasty.2

In evaluating rates of hysterectomy with or without salpingo-oophorectomy, approximately 21% of transgender men underwent hysterectomy, with 58% desiring it in the future.2 Unlike patients pursuing top surgery, patients who desire any form of bottom surgery need to be on 12 months of continuous hormone therapy.1 They also must provide two letters from two different mental health providers, one of whom must have either an MD/DO or PhD. In cases in which a patient requests a hysterectomy for reasons other than gender dysphoria, such as pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding, these criteria do not apply.

For transfeminine individuals, augmentation mammoplasty is performed following 12 months of continuous hormone therapy. This is to allow maximum breast growth, which occurs approximately 2-3 months after hormone initiation and peaks at 1-2 years.3 Rates of transfeminine individuals seeking augmentation mammoplasty is similar to that of their transmasculine counterparts at 74%.2 One referral letter from a mental health provider is also needed prior to augmentation mammoplasty.