User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Commonly used antibiotics in ObGyn practice

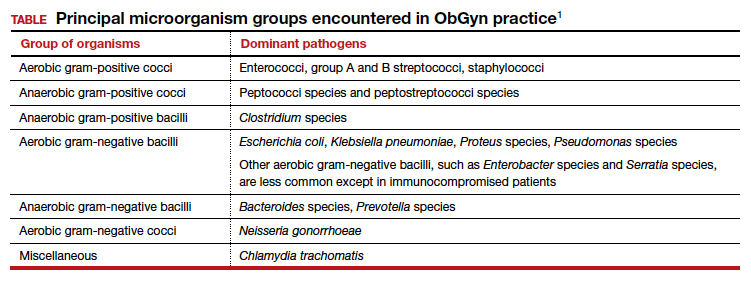

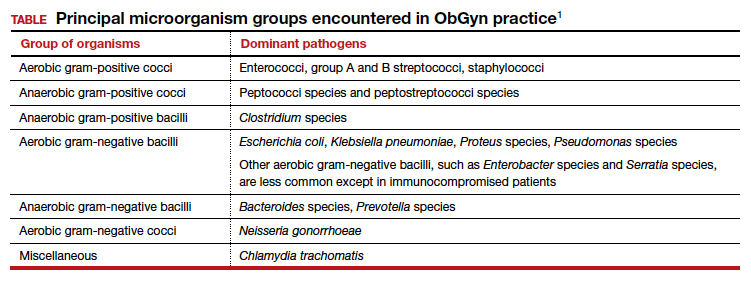

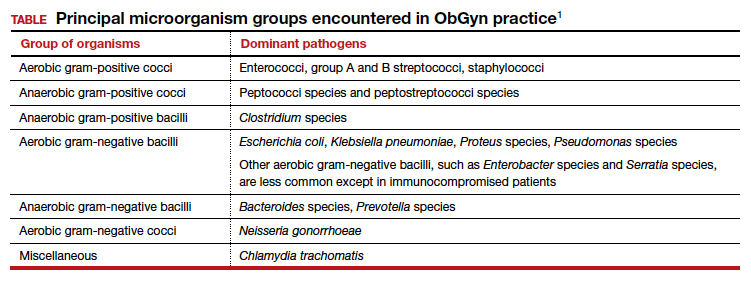

In this article, I provide a simplified, practical review of the principal antibiotics that we use on a daily basis to treat bacterial infections. The antibiotics are listed in alphabetical order, either individually or by group. I focus first on the mechanism of action and spectrum of activity of the drugs used against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE).1 I then review their principal adverse effects, relative cost (categorized as low, intermediate, and high), and the key indications for these drugs in obstetrics and gynecology. In a forthcoming 2-part companion article, I will review how to select specific antibiotics and their dosing regimens for the most commonly encountered bacterial infections in our clinical practice.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics

The aminoglycosides include amikacin, gentamicin, plazomicin, and tobramycin.2,3 The 2 agents most commonly used in our specialty are amikacin and gentamicin. The drugs may be administered intramuscularly or intravenously, and they specifically target aerobic gram-negative bacilli. They also provide coverage against staphylococci and gonococci. Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are their principal adverse effects.

Aminoglycosides are used primarily as single agents to treat pyelonephritis caused by highly resistant bacteria and in combination with agents such as clindamycin and metronidazole to treat polymicrobial infections, including chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Of all the aminoglycosides, gentamicin is clearly the least expensive.

Carbapenems

The original carbapenem widely introduced into clinical practice was imipenem-cilastatin. Imipenem, the active antibiotic, inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. Cilastatin inhibits renal dehydropeptidase I and, thereby, slows the metabolism of imipenem by the kidney. Other carbapenems include meropenem and ertapenem.

The carbapenems have the widest spectrum of activity against the pelvic pathogens of any antibiotic. They provide excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci and aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the enterococci very well.

A major adverse effect of the carbapenems is an allergic reaction, including anaphylaxis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and there is some minimal cross-sensitivity with the β-lactam antibiotics. Other important, but fortunately rare, adverse effects include neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and Clostridium difficile colitis.4

As a group, the carbapenems are relatively more expensive than most other agents. Their principal application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of serious polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis, pelvic cellulitis, and pelvic abscess, especially in patients who have a contraindication to the use of combination antibiotic regimens that include an aminoglycoside.1,2

Cephalosporins

The cephalosporins are β-lactam antibiotics that act by disrupting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. They may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. The most common adverse effects associated with these agents are an allergic reaction, which can range from a mild rash to anaphylaxis and the Stevens-Johnson syndrome; central nervous system toxicity; and antibiotic-induced diarrhea, including C difficile colitis.1,2,4

This group of antibiotics can be confusing because it includes so many agents, and their spectrum of activity varies. I find it helpful to think about the coverage of these agents as limited spectrum versus intermediate spectrum versus extended spectrum.

The limited-spectrum cephalosporin prototypes are cephalexin (oral administration) and cefazolin (parenteral administration). This group of cephalosporins provides excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci. They are excellent against staphylococci, except for MRSA. Coverage is moderate for aerobic gram-negative bacilli but only limited for anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover the enterococci. In our specialty, their principal application is for treatment of mastitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and wound infections and for prophylaxis against group B streptococcus (GBS) infection and post-cesarean infection.2,5 The cost of these drugs is relatively low.

The prototypes of the intermediate-spectrum cephalosporins are cefixime (oral) and ceftriaxone (parenteral). Both drugs have strong activity against aerobic and anaerobic streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, most aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and Treponema pallidum (principally, ceftriaxone). They are not consistently effective against staphylococci, particularly MRSA, and enterococci. Their key indications in obstetrics and gynecology are treatment of gonorrhea, syphilis (in penicillin-allergic patients), and acute pyelonephritis. Compared with the limited-spectrum cephalosporins, these antibiotics are moderately expensive.1,2

The 3 extended-spectrum cephalosporins used most commonly in our specialty are cefepime, cefotetan, and cefoxitin. These agents are administered intramuscularly and intravenously, and they provide very good coverage against aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci, with the exception of staphylococci and enterococci. They have very good coverage against most gram-negative aerobic bacilli and excellent coverage against anerobic microorganisms. Their primary application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis and pelvic cellulitis. When used in combination with doxycycline, they are valuable in treating pelvic inflammatory disease. These drugs are more expensive than the limited-spectrum or intermediate-spectrum agents. They should not be used routinely as prophylaxis for pelvic surgery.1,2,5

Continue to: Fluorinated quinolones...

Fluorinated quinolones

The fluorinated quinolones include several agents, but the 3 most commonly used in our specialty are ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin. All 3 drugs can be administered orally; ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin also are available in intravenous formulations. These drugs interfere with bacterial protein synthesis by targeting DNA gyrase, an enzyme that introduces negative supertwists into DNA and separates interlocked DNA molecules.

These drugs provide excellent coverage against gram-negative bacilli, including Haemophilus influenzae; gram-negative cocci, such as N gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Moraxella catarrhalis; and many staphylococci species. Levofloxacin, but not the other 2 drugs, provides moderate coverage against anaerobes. Ofloxacin and levofloxacin are active against chlamydia. Levofloxacin also covers the mycoplasma organisms that are responsible for atypical pneumonia.

As a group, the fluorinated quinolones are moderately expensive. The most likely adverse effects with these agents are gastrointestinal (GI) upset, headache, agitation, and sleep disturbance. Allergic reactions are rare. These drugs are of primary value in our specialty in treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, complicated UTIs, and respiratory tract infections.1,2,6

The penicillins

Penicillin

Penicillin, a β-lactam antibiotic, was one of the first antibiotics developed and employed in clinical practice. It may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Penicillin exerts its effect by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Its principal spectrum of activity is against aerobic streptococci, such as group A and B streptococcus; most anaerobic gram-positive cocci that are present in the vaginal flora; some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli; and T pallidum. Penicillin is not effective against the majority of staphylococci species, enterococci, or aerobic gram-negative bacilli, such as Escherichia coli.

Penicillin’s major adverse effect is an allergic reaction, experienced by less than 10% of recipients.7 Most reactions are mild and are characterized by a morbilliform skin rash. However, some reactions are severe and take the form of an urticarial skin eruption, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and overt anaphylaxis. The cost of both oral and parenteral penicillin formulations is very low. In obstetrics and gynecology, penicillin is used primarily for the treatment of group A and B streptococci infections, clostridial infections, and syphilis.1,2

Ampicillin and amoxicillin

The β-lactam antibiotics ampicillin and amoxicillin also act by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Amoxicillin is administered orally; ampicillin may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Their spectrum of activity includes group A and B streptococci, enterococci, most anaerobic gram-positive cocci, some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, many aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and clostridial organisms.

Like penicillin, ampicillin and amoxicillin may cause allergic reactions that range from mild rashes to anaphylaxis. Unlike the more narrow-spectrum penicillin, they may cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including C difficile colitis,4 and they may eliminate part of the normal vaginal flora and stimulate an overgrowth of yeast organisms in the vagina. The cost of ampicillin and amoxicillin is very low. These 2 agents are used primarily for treatment of group A and B streptococci infections and some UTIs, particularly those caused by enterococci.1,2

Dicloxacillin sodium

This penicillin derivative disrupts bacterial cell wall synthesis and targets primarily aerobic gram-positive cocci, particularly staphylococci species. The antibiotic is not active against MRSA. The principal adverse effects of dicloxacillin sodium are an allergic reaction and GI upset. The drug is very inexpensive.

The key application for dicloxacillin sodium in our specialty is for treatment of puerperal mastitis.1

Continue to: Extended-spectrum penicillins...

Extended-spectrum penicillins

Three interesting combination extended-spectrum penicillins are used widely in our specialty. They are ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and piperacillin/tazobactam. Ampicillin/sulbactam may be administered intramuscularly and intravenously. Piperacillin/tazobactam is administered intravenously; amoxicillin/clavulanate is administered orally.

Clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam are β-lactamase inhibitors. When added to the parent antibiotic (amoxicillin, ampicillin, and piperacillin, respectively), they significantly enhance the parent drug’s spectrum of activity. These agents interfere with bacterial cell wall synthesis. They provide excellent coverage of aerobic gram-positive cocci, including enterococci; anaerobic gram-positive cocci; anaerobic gram-negative bacilli; and aerobic gram-negative bacilli. Their principal adverse effects include allergic reactions and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. They are moderately expensive.

The principal application of ampicillin/sulbactam and piperacillin/tazobactam in our specialty is as single agents for treatment of puerperal endometritis, postoperative pelvic cellulitis, and pyelonephritis. The usual role for amoxicillin/clavulanate is for oral treatment of complicated UTIs, including pyelonephritis in early pregnancy, and for outpatient therapy of mild to moderately severe endometritis following delivery or pregnancy termination.

Macrolides, monobactams, and additional antibiotics

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic that is in the same class as erythromycin and clindamycin. In our specialty, it has largely replaced erythromycin because of its more convenient dosage schedule and its better tolerability. It inhibits bacterial protein synthesis, and it is available in both an oral and intravenous formulation.

Azithromycin has an excellent spectrum of activity against the 3 major microorganisms that cause otitis media, sinusitis, and bronchitis: Streptococcus pneumoniae, H influenzae, and M catarrhalis. It also provides excellent coverage of Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and genital mycoplasmas; in high doses it provides modest coverage against gonorrhea.8 Unlike erythromycin, it has minimal GI toxicity and is usually very well tolerated by most patients. One unusual, but very important, adverse effect of the drug is prolongation of the Q-T interval.9

Azithromycin is now available in generic form and is relatively inexpensive. As a single agent, its principal applications in our specialty are for treatment of respiratory tract infections such as otitis media, sinusitis, and acute bronchitis and for treatment of chlamydia urethritis and endocervicitis.8,10 In combination with ampicillin, azithromycin is used as prophylaxis in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), and, in combination with cefazolin, it is used for prophylaxis in patients undergoing cesarean delivery.1,2,5

Aztreonam

Aztreonam is a monobactam antibiotic. Like the cephalosporins and penicillins, aztreonam inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. It may be administered intramuscularly and intravenously, and its principal spectrum of activity is against aerobic gram-negative bacilli, which is similar to the aminoglycosides’ spectrum.

Aztreonam’s most likely adverse effects include phlebitis at the injection site, allergy, GI upset, and diarrhea. The drug is moderately expensive. In our specialty, aztreonam could be used as a single agent, in lieu of an aminoglycoside, for treatment of pyelonephritis caused by an unusually resistant organism. It also could be used in combination with clindamycin or metronidazole plus ampicillin for treatment of polymicrobial infections, such as chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic cellulitis.1,2

Continue to: Clindamycin...

Clindamycin

A macrolide antibiotic, clindamycin exerts its antibacterial effect by interfering with bacterial protein synthesis. It can be administered orally and intravenously. Its key spectrum of activity in our specialty includes GBS, staphylococci, and anaerobes. However, clindamycin is not active against enterococci or aerobic gram-negative bacilli. GI upset and antibiotic-induced diarrhea are its principal adverse effects, and clindamycin is one of the most important causes of C difficile colitis. Although it is available in a generic formulation, this drug is still relatively expensive.

Clindamycin’s principal application in our specialty is for treating staphylococcal infections, such as wound infections and mastitis. It is particularly effective against MRSA infections. When used in combination with an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin, clindamycin provides excellent treatment for chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. In fact, for many years, the combination of clindamycin plus gentamicin has been considered the gold standard for the treatment of polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic pelvic infections.1,2

Doxycycline

Doxycycline, a tetracycline, exerts its antibacterial effect by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. The drug targets a broad range of pelvic pathogens, including C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae, and it may be administered both orally and intravenously. Doxycycline’s principal adverse effects include headache, GI upset, and photosensitivity. By disrupting the normal bowel and vaginal flora, the drug also can cause diarrhea and vulvovaginal moniliasis. In addition, it can cause permanent discoloration of the teeth, and, for this reason, doxycycline should not be used in pregnant or lactating women or in young children.

Although doxycycline has been available in generic formulation for many years, it remains relatively expensive. As a single agent, its principal application in our specialty is for treatment of chlamydia infection. It may be used as prophylaxis for surgical procedures, such as hysterectomy and pregnancy terminations. In combination with an extended-spectrum cephalosporin, it also may be used to treat pelvic inflammatory disease.2,8,10

Metronidazole

Metronidazole, a nitroimidazole derivative, exerts its antibacterial effect by disrupting bacterial protein synthesis. The drug may be administered topically, orally, and intravenously. Its primary spectrum of activity is against anerobic microorganisms. It is also active against Giardia and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Metronidazole’s most common adverse effects are GI upset, a metallic taste in the mouth, and a disulfiram-like effect when taken with alcohol. The cost of oral and intravenous metronidazole is relatively low; ironically, the cost of topical metronidazole is relatively high. In our specialty, the principal applications of oral metronidazole are as a single agent for treatment of bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. When combined with ampicillin plus an aminoglycoside, intravenous metronidazole provides excellent coverage against the diverse anaerobic microorganisms that cause chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic cellulitis.1,2

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

This antibiotic combination (an antifolate and a sulfonamide) inhibits sequential steps in the synthesis of folic acid, an essential nutrient in bacterial metabolism. It is available in both an intravenous and oral formulation. TMP-SMX has a broad spectrum of activity against the aerobic gram-negative bacilli that cause UTIs in women. In addition, it provides excellent coverage against staphylococci, including MRSA; Pneumocystis jirovecii; and Toxoplasma gondii.

The medication’s principal toxicity is an allergic reaction. Some reactions are quite severe, such as the Stevens-Johnson syndrome. TMP-SMX is relatively inexpensive, particularly the oral formulation. The most common indications for TMP-SMX in our specialty are for treatment of UTIs, mastitis, and wound infections.1,2,11 In HIV-infected patients, the drug provides excellent prophylaxis against recurrent Pneumocystis and Toxoplasma infections. TMP-SMX should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been linked to several birth defects, including neural tube defects, heart defects, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia.12

Nitrofurantoin

Usually administered orally as nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals, nitrofurantoin exerts its antibacterial effect primarily by inhibiting protein synthesis. Its principal spectrum of activity is against the aerobic gram-negative bacilli, with the exception of Proteus species. Nitrofurantoin’s most common adverse effects are GI upset, headache, vertigo, drowsiness, and allergic reactions. The drug is relatively inexpensive.

Nitrofurantoin is an excellent agent for the treatment of lower UTIs.11 It is not well concentrated in the renal parenchyma or blood, however, so it should not be used to treat pyelonephritis. As a general rule, nitrofurantoin should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with eye, heart, and facial cleft defects in the fetus.12

Vancomycin

Vancomycin exerts its antibacterial effect by inhibiting cell wall synthesis. It may be administered both orally and intravenously, and it specifically targets aerobic gram-positive cocci, particularly methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Vancomycin’s most important adverse effects include GI upset, nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and severe allergic reactions, such as anaphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and exfoliative dermatitis (the “red man” syndrome). The drug is moderately expensive.13

In its oral formulation, vancomycin’s principal application in our discipline is for treating C difficile colitis. In its intravenous formulation, it is used primarily as a single agent for GBS prophylaxis in penicillin-allergic patients, and it is used in combination with other antibiotics, such as clindamycin plus gentamicin, for treating patients with deep-seated incisional (wound) infections.1,2,13,14 ●

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020: chapter 58.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetrics: making cost-effective choices. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:59-72.

- Wagenlehner FME, Cloutier DJ, Komirenko AS, et al; EPIC Study Group. Once-daily plazomicin for complicated urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:729-740.

- Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1539-1548.

- Duff P. Prevention of infection after cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:758-770.

- Hooper DC, Wolfson JS. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:384-394.

- Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019 381:2338-2351.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, et al. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1881-1890.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

- Duff P. UTIs in pregnancy: managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. OBG Manag. 2022;34(1):42-46.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, et al. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects prevalence study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:978985.

- Alvarez-Arango S, Ogunwole SM, Sequist TD, et al. Vancomycin infusion reaction—moving beyond “red man syndrome.” N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1283-1286.

- Finley TA, Duff P. Antibiotics for treatment of staphylococcal infections in the obstetric patient. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:790-803.

In this article, I provide a simplified, practical review of the principal antibiotics that we use on a daily basis to treat bacterial infections. The antibiotics are listed in alphabetical order, either individually or by group. I focus first on the mechanism of action and spectrum of activity of the drugs used against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE).1 I then review their principal adverse effects, relative cost (categorized as low, intermediate, and high), and the key indications for these drugs in obstetrics and gynecology. In a forthcoming 2-part companion article, I will review how to select specific antibiotics and their dosing regimens for the most commonly encountered bacterial infections in our clinical practice.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics

The aminoglycosides include amikacin, gentamicin, plazomicin, and tobramycin.2,3 The 2 agents most commonly used in our specialty are amikacin and gentamicin. The drugs may be administered intramuscularly or intravenously, and they specifically target aerobic gram-negative bacilli. They also provide coverage against staphylococci and gonococci. Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are their principal adverse effects.

Aminoglycosides are used primarily as single agents to treat pyelonephritis caused by highly resistant bacteria and in combination with agents such as clindamycin and metronidazole to treat polymicrobial infections, including chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Of all the aminoglycosides, gentamicin is clearly the least expensive.

Carbapenems

The original carbapenem widely introduced into clinical practice was imipenem-cilastatin. Imipenem, the active antibiotic, inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. Cilastatin inhibits renal dehydropeptidase I and, thereby, slows the metabolism of imipenem by the kidney. Other carbapenems include meropenem and ertapenem.

The carbapenems have the widest spectrum of activity against the pelvic pathogens of any antibiotic. They provide excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci and aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the enterococci very well.

A major adverse effect of the carbapenems is an allergic reaction, including anaphylaxis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and there is some minimal cross-sensitivity with the β-lactam antibiotics. Other important, but fortunately rare, adverse effects include neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and Clostridium difficile colitis.4

As a group, the carbapenems are relatively more expensive than most other agents. Their principal application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of serious polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis, pelvic cellulitis, and pelvic abscess, especially in patients who have a contraindication to the use of combination antibiotic regimens that include an aminoglycoside.1,2

Cephalosporins

The cephalosporins are β-lactam antibiotics that act by disrupting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. They may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. The most common adverse effects associated with these agents are an allergic reaction, which can range from a mild rash to anaphylaxis and the Stevens-Johnson syndrome; central nervous system toxicity; and antibiotic-induced diarrhea, including C difficile colitis.1,2,4

This group of antibiotics can be confusing because it includes so many agents, and their spectrum of activity varies. I find it helpful to think about the coverage of these agents as limited spectrum versus intermediate spectrum versus extended spectrum.

The limited-spectrum cephalosporin prototypes are cephalexin (oral administration) and cefazolin (parenteral administration). This group of cephalosporins provides excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci. They are excellent against staphylococci, except for MRSA. Coverage is moderate for aerobic gram-negative bacilli but only limited for anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover the enterococci. In our specialty, their principal application is for treatment of mastitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and wound infections and for prophylaxis against group B streptococcus (GBS) infection and post-cesarean infection.2,5 The cost of these drugs is relatively low.

The prototypes of the intermediate-spectrum cephalosporins are cefixime (oral) and ceftriaxone (parenteral). Both drugs have strong activity against aerobic and anaerobic streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, most aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and Treponema pallidum (principally, ceftriaxone). They are not consistently effective against staphylococci, particularly MRSA, and enterococci. Their key indications in obstetrics and gynecology are treatment of gonorrhea, syphilis (in penicillin-allergic patients), and acute pyelonephritis. Compared with the limited-spectrum cephalosporins, these antibiotics are moderately expensive.1,2

The 3 extended-spectrum cephalosporins used most commonly in our specialty are cefepime, cefotetan, and cefoxitin. These agents are administered intramuscularly and intravenously, and they provide very good coverage against aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci, with the exception of staphylococci and enterococci. They have very good coverage against most gram-negative aerobic bacilli and excellent coverage against anerobic microorganisms. Their primary application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis and pelvic cellulitis. When used in combination with doxycycline, they are valuable in treating pelvic inflammatory disease. These drugs are more expensive than the limited-spectrum or intermediate-spectrum agents. They should not be used routinely as prophylaxis for pelvic surgery.1,2,5

Continue to: Fluorinated quinolones...

Fluorinated quinolones

The fluorinated quinolones include several agents, but the 3 most commonly used in our specialty are ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin. All 3 drugs can be administered orally; ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin also are available in intravenous formulations. These drugs interfere with bacterial protein synthesis by targeting DNA gyrase, an enzyme that introduces negative supertwists into DNA and separates interlocked DNA molecules.

These drugs provide excellent coverage against gram-negative bacilli, including Haemophilus influenzae; gram-negative cocci, such as N gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Moraxella catarrhalis; and many staphylococci species. Levofloxacin, but not the other 2 drugs, provides moderate coverage against anaerobes. Ofloxacin and levofloxacin are active against chlamydia. Levofloxacin also covers the mycoplasma organisms that are responsible for atypical pneumonia.

As a group, the fluorinated quinolones are moderately expensive. The most likely adverse effects with these agents are gastrointestinal (GI) upset, headache, agitation, and sleep disturbance. Allergic reactions are rare. These drugs are of primary value in our specialty in treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, complicated UTIs, and respiratory tract infections.1,2,6

The penicillins

Penicillin

Penicillin, a β-lactam antibiotic, was one of the first antibiotics developed and employed in clinical practice. It may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Penicillin exerts its effect by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Its principal spectrum of activity is against aerobic streptococci, such as group A and B streptococcus; most anaerobic gram-positive cocci that are present in the vaginal flora; some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli; and T pallidum. Penicillin is not effective against the majority of staphylococci species, enterococci, or aerobic gram-negative bacilli, such as Escherichia coli.

Penicillin’s major adverse effect is an allergic reaction, experienced by less than 10% of recipients.7 Most reactions are mild and are characterized by a morbilliform skin rash. However, some reactions are severe and take the form of an urticarial skin eruption, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and overt anaphylaxis. The cost of both oral and parenteral penicillin formulations is very low. In obstetrics and gynecology, penicillin is used primarily for the treatment of group A and B streptococci infections, clostridial infections, and syphilis.1,2

Ampicillin and amoxicillin

The β-lactam antibiotics ampicillin and amoxicillin also act by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Amoxicillin is administered orally; ampicillin may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Their spectrum of activity includes group A and B streptococci, enterococci, most anaerobic gram-positive cocci, some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, many aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and clostridial organisms.

Like penicillin, ampicillin and amoxicillin may cause allergic reactions that range from mild rashes to anaphylaxis. Unlike the more narrow-spectrum penicillin, they may cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including C difficile colitis,4 and they may eliminate part of the normal vaginal flora and stimulate an overgrowth of yeast organisms in the vagina. The cost of ampicillin and amoxicillin is very low. These 2 agents are used primarily for treatment of group A and B streptococci infections and some UTIs, particularly those caused by enterococci.1,2

Dicloxacillin sodium

This penicillin derivative disrupts bacterial cell wall synthesis and targets primarily aerobic gram-positive cocci, particularly staphylococci species. The antibiotic is not active against MRSA. The principal adverse effects of dicloxacillin sodium are an allergic reaction and GI upset. The drug is very inexpensive.

The key application for dicloxacillin sodium in our specialty is for treatment of puerperal mastitis.1

Continue to: Extended-spectrum penicillins...

Extended-spectrum penicillins

Three interesting combination extended-spectrum penicillins are used widely in our specialty. They are ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and piperacillin/tazobactam. Ampicillin/sulbactam may be administered intramuscularly and intravenously. Piperacillin/tazobactam is administered intravenously; amoxicillin/clavulanate is administered orally.

Clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam are β-lactamase inhibitors. When added to the parent antibiotic (amoxicillin, ampicillin, and piperacillin, respectively), they significantly enhance the parent drug’s spectrum of activity. These agents interfere with bacterial cell wall synthesis. They provide excellent coverage of aerobic gram-positive cocci, including enterococci; anaerobic gram-positive cocci; anaerobic gram-negative bacilli; and aerobic gram-negative bacilli. Their principal adverse effects include allergic reactions and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. They are moderately expensive.

The principal application of ampicillin/sulbactam and piperacillin/tazobactam in our specialty is as single agents for treatment of puerperal endometritis, postoperative pelvic cellulitis, and pyelonephritis. The usual role for amoxicillin/clavulanate is for oral treatment of complicated UTIs, including pyelonephritis in early pregnancy, and for outpatient therapy of mild to moderately severe endometritis following delivery or pregnancy termination.

Macrolides, monobactams, and additional antibiotics

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic that is in the same class as erythromycin and clindamycin. In our specialty, it has largely replaced erythromycin because of its more convenient dosage schedule and its better tolerability. It inhibits bacterial protein synthesis, and it is available in both an oral and intravenous formulation.

Azithromycin has an excellent spectrum of activity against the 3 major microorganisms that cause otitis media, sinusitis, and bronchitis: Streptococcus pneumoniae, H influenzae, and M catarrhalis. It also provides excellent coverage of Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and genital mycoplasmas; in high doses it provides modest coverage against gonorrhea.8 Unlike erythromycin, it has minimal GI toxicity and is usually very well tolerated by most patients. One unusual, but very important, adverse effect of the drug is prolongation of the Q-T interval.9

Azithromycin is now available in generic form and is relatively inexpensive. As a single agent, its principal applications in our specialty are for treatment of respiratory tract infections such as otitis media, sinusitis, and acute bronchitis and for treatment of chlamydia urethritis and endocervicitis.8,10 In combination with ampicillin, azithromycin is used as prophylaxis in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), and, in combination with cefazolin, it is used for prophylaxis in patients undergoing cesarean delivery.1,2,5

Aztreonam

Aztreonam is a monobactam antibiotic. Like the cephalosporins and penicillins, aztreonam inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. It may be administered intramuscularly and intravenously, and its principal spectrum of activity is against aerobic gram-negative bacilli, which is similar to the aminoglycosides’ spectrum.

Aztreonam’s most likely adverse effects include phlebitis at the injection site, allergy, GI upset, and diarrhea. The drug is moderately expensive. In our specialty, aztreonam could be used as a single agent, in lieu of an aminoglycoside, for treatment of pyelonephritis caused by an unusually resistant organism. It also could be used in combination with clindamycin or metronidazole plus ampicillin for treatment of polymicrobial infections, such as chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic cellulitis.1,2

Continue to: Clindamycin...

Clindamycin

A macrolide antibiotic, clindamycin exerts its antibacterial effect by interfering with bacterial protein synthesis. It can be administered orally and intravenously. Its key spectrum of activity in our specialty includes GBS, staphylococci, and anaerobes. However, clindamycin is not active against enterococci or aerobic gram-negative bacilli. GI upset and antibiotic-induced diarrhea are its principal adverse effects, and clindamycin is one of the most important causes of C difficile colitis. Although it is available in a generic formulation, this drug is still relatively expensive.

Clindamycin’s principal application in our specialty is for treating staphylococcal infections, such as wound infections and mastitis. It is particularly effective against MRSA infections. When used in combination with an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin, clindamycin provides excellent treatment for chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. In fact, for many years, the combination of clindamycin plus gentamicin has been considered the gold standard for the treatment of polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic pelvic infections.1,2

Doxycycline

Doxycycline, a tetracycline, exerts its antibacterial effect by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. The drug targets a broad range of pelvic pathogens, including C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae, and it may be administered both orally and intravenously. Doxycycline’s principal adverse effects include headache, GI upset, and photosensitivity. By disrupting the normal bowel and vaginal flora, the drug also can cause diarrhea and vulvovaginal moniliasis. In addition, it can cause permanent discoloration of the teeth, and, for this reason, doxycycline should not be used in pregnant or lactating women or in young children.

Although doxycycline has been available in generic formulation for many years, it remains relatively expensive. As a single agent, its principal application in our specialty is for treatment of chlamydia infection. It may be used as prophylaxis for surgical procedures, such as hysterectomy and pregnancy terminations. In combination with an extended-spectrum cephalosporin, it also may be used to treat pelvic inflammatory disease.2,8,10

Metronidazole

Metronidazole, a nitroimidazole derivative, exerts its antibacterial effect by disrupting bacterial protein synthesis. The drug may be administered topically, orally, and intravenously. Its primary spectrum of activity is against anerobic microorganisms. It is also active against Giardia and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Metronidazole’s most common adverse effects are GI upset, a metallic taste in the mouth, and a disulfiram-like effect when taken with alcohol. The cost of oral and intravenous metronidazole is relatively low; ironically, the cost of topical metronidazole is relatively high. In our specialty, the principal applications of oral metronidazole are as a single agent for treatment of bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. When combined with ampicillin plus an aminoglycoside, intravenous metronidazole provides excellent coverage against the diverse anaerobic microorganisms that cause chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic cellulitis.1,2

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

This antibiotic combination (an antifolate and a sulfonamide) inhibits sequential steps in the synthesis of folic acid, an essential nutrient in bacterial metabolism. It is available in both an intravenous and oral formulation. TMP-SMX has a broad spectrum of activity against the aerobic gram-negative bacilli that cause UTIs in women. In addition, it provides excellent coverage against staphylococci, including MRSA; Pneumocystis jirovecii; and Toxoplasma gondii.

The medication’s principal toxicity is an allergic reaction. Some reactions are quite severe, such as the Stevens-Johnson syndrome. TMP-SMX is relatively inexpensive, particularly the oral formulation. The most common indications for TMP-SMX in our specialty are for treatment of UTIs, mastitis, and wound infections.1,2,11 In HIV-infected patients, the drug provides excellent prophylaxis against recurrent Pneumocystis and Toxoplasma infections. TMP-SMX should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been linked to several birth defects, including neural tube defects, heart defects, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia.12

Nitrofurantoin

Usually administered orally as nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals, nitrofurantoin exerts its antibacterial effect primarily by inhibiting protein synthesis. Its principal spectrum of activity is against the aerobic gram-negative bacilli, with the exception of Proteus species. Nitrofurantoin’s most common adverse effects are GI upset, headache, vertigo, drowsiness, and allergic reactions. The drug is relatively inexpensive.

Nitrofurantoin is an excellent agent for the treatment of lower UTIs.11 It is not well concentrated in the renal parenchyma or blood, however, so it should not be used to treat pyelonephritis. As a general rule, nitrofurantoin should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with eye, heart, and facial cleft defects in the fetus.12

Vancomycin

Vancomycin exerts its antibacterial effect by inhibiting cell wall synthesis. It may be administered both orally and intravenously, and it specifically targets aerobic gram-positive cocci, particularly methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Vancomycin’s most important adverse effects include GI upset, nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and severe allergic reactions, such as anaphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and exfoliative dermatitis (the “red man” syndrome). The drug is moderately expensive.13

In its oral formulation, vancomycin’s principal application in our discipline is for treating C difficile colitis. In its intravenous formulation, it is used primarily as a single agent for GBS prophylaxis in penicillin-allergic patients, and it is used in combination with other antibiotics, such as clindamycin plus gentamicin, for treating patients with deep-seated incisional (wound) infections.1,2,13,14 ●

In this article, I provide a simplified, practical review of the principal antibiotics that we use on a daily basis to treat bacterial infections. The antibiotics are listed in alphabetical order, either individually or by group. I focus first on the mechanism of action and spectrum of activity of the drugs used against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE).1 I then review their principal adverse effects, relative cost (categorized as low, intermediate, and high), and the key indications for these drugs in obstetrics and gynecology. In a forthcoming 2-part companion article, I will review how to select specific antibiotics and their dosing regimens for the most commonly encountered bacterial infections in our clinical practice.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics

The aminoglycosides include amikacin, gentamicin, plazomicin, and tobramycin.2,3 The 2 agents most commonly used in our specialty are amikacin and gentamicin. The drugs may be administered intramuscularly or intravenously, and they specifically target aerobic gram-negative bacilli. They also provide coverage against staphylococci and gonococci. Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are their principal adverse effects.

Aminoglycosides are used primarily as single agents to treat pyelonephritis caused by highly resistant bacteria and in combination with agents such as clindamycin and metronidazole to treat polymicrobial infections, including chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Of all the aminoglycosides, gentamicin is clearly the least expensive.

Carbapenems

The original carbapenem widely introduced into clinical practice was imipenem-cilastatin. Imipenem, the active antibiotic, inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. Cilastatin inhibits renal dehydropeptidase I and, thereby, slows the metabolism of imipenem by the kidney. Other carbapenems include meropenem and ertapenem.

The carbapenems have the widest spectrum of activity against the pelvic pathogens of any antibiotic. They provide excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci and aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the enterococci very well.

A major adverse effect of the carbapenems is an allergic reaction, including anaphylaxis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and there is some minimal cross-sensitivity with the β-lactam antibiotics. Other important, but fortunately rare, adverse effects include neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and Clostridium difficile colitis.4

As a group, the carbapenems are relatively more expensive than most other agents. Their principal application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of serious polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis, pelvic cellulitis, and pelvic abscess, especially in patients who have a contraindication to the use of combination antibiotic regimens that include an aminoglycoside.1,2

Cephalosporins

The cephalosporins are β-lactam antibiotics that act by disrupting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. They may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. The most common adverse effects associated with these agents are an allergic reaction, which can range from a mild rash to anaphylaxis and the Stevens-Johnson syndrome; central nervous system toxicity; and antibiotic-induced diarrhea, including C difficile colitis.1,2,4

This group of antibiotics can be confusing because it includes so many agents, and their spectrum of activity varies. I find it helpful to think about the coverage of these agents as limited spectrum versus intermediate spectrum versus extended spectrum.

The limited-spectrum cephalosporin prototypes are cephalexin (oral administration) and cefazolin (parenteral administration). This group of cephalosporins provides excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci. They are excellent against staphylococci, except for MRSA. Coverage is moderate for aerobic gram-negative bacilli but only limited for anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover the enterococci. In our specialty, their principal application is for treatment of mastitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and wound infections and for prophylaxis against group B streptococcus (GBS) infection and post-cesarean infection.2,5 The cost of these drugs is relatively low.

The prototypes of the intermediate-spectrum cephalosporins are cefixime (oral) and ceftriaxone (parenteral). Both drugs have strong activity against aerobic and anaerobic streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, most aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and Treponema pallidum (principally, ceftriaxone). They are not consistently effective against staphylococci, particularly MRSA, and enterococci. Their key indications in obstetrics and gynecology are treatment of gonorrhea, syphilis (in penicillin-allergic patients), and acute pyelonephritis. Compared with the limited-spectrum cephalosporins, these antibiotics are moderately expensive.1,2

The 3 extended-spectrum cephalosporins used most commonly in our specialty are cefepime, cefotetan, and cefoxitin. These agents are administered intramuscularly and intravenously, and they provide very good coverage against aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci, with the exception of staphylococci and enterococci. They have very good coverage against most gram-negative aerobic bacilli and excellent coverage against anerobic microorganisms. Their primary application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis and pelvic cellulitis. When used in combination with doxycycline, they are valuable in treating pelvic inflammatory disease. These drugs are more expensive than the limited-spectrum or intermediate-spectrum agents. They should not be used routinely as prophylaxis for pelvic surgery.1,2,5

Continue to: Fluorinated quinolones...

Fluorinated quinolones

The fluorinated quinolones include several agents, but the 3 most commonly used in our specialty are ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin. All 3 drugs can be administered orally; ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin also are available in intravenous formulations. These drugs interfere with bacterial protein synthesis by targeting DNA gyrase, an enzyme that introduces negative supertwists into DNA and separates interlocked DNA molecules.

These drugs provide excellent coverage against gram-negative bacilli, including Haemophilus influenzae; gram-negative cocci, such as N gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Moraxella catarrhalis; and many staphylococci species. Levofloxacin, but not the other 2 drugs, provides moderate coverage against anaerobes. Ofloxacin and levofloxacin are active against chlamydia. Levofloxacin also covers the mycoplasma organisms that are responsible for atypical pneumonia.

As a group, the fluorinated quinolones are moderately expensive. The most likely adverse effects with these agents are gastrointestinal (GI) upset, headache, agitation, and sleep disturbance. Allergic reactions are rare. These drugs are of primary value in our specialty in treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, complicated UTIs, and respiratory tract infections.1,2,6

The penicillins

Penicillin

Penicillin, a β-lactam antibiotic, was one of the first antibiotics developed and employed in clinical practice. It may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Penicillin exerts its effect by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Its principal spectrum of activity is against aerobic streptococci, such as group A and B streptococcus; most anaerobic gram-positive cocci that are present in the vaginal flora; some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli; and T pallidum. Penicillin is not effective against the majority of staphylococci species, enterococci, or aerobic gram-negative bacilli, such as Escherichia coli.

Penicillin’s major adverse effect is an allergic reaction, experienced by less than 10% of recipients.7 Most reactions are mild and are characterized by a morbilliform skin rash. However, some reactions are severe and take the form of an urticarial skin eruption, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and overt anaphylaxis. The cost of both oral and parenteral penicillin formulations is very low. In obstetrics and gynecology, penicillin is used primarily for the treatment of group A and B streptococci infections, clostridial infections, and syphilis.1,2

Ampicillin and amoxicillin

The β-lactam antibiotics ampicillin and amoxicillin also act by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Amoxicillin is administered orally; ampicillin may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Their spectrum of activity includes group A and B streptococci, enterococci, most anaerobic gram-positive cocci, some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, many aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and clostridial organisms.

Like penicillin, ampicillin and amoxicillin may cause allergic reactions that range from mild rashes to anaphylaxis. Unlike the more narrow-spectrum penicillin, they may cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including C difficile colitis,4 and they may eliminate part of the normal vaginal flora and stimulate an overgrowth of yeast organisms in the vagina. The cost of ampicillin and amoxicillin is very low. These 2 agents are used primarily for treatment of group A and B streptococci infections and some UTIs, particularly those caused by enterococci.1,2

Dicloxacillin sodium

This penicillin derivative disrupts bacterial cell wall synthesis and targets primarily aerobic gram-positive cocci, particularly staphylococci species. The antibiotic is not active against MRSA. The principal adverse effects of dicloxacillin sodium are an allergic reaction and GI upset. The drug is very inexpensive.

The key application for dicloxacillin sodium in our specialty is for treatment of puerperal mastitis.1

Continue to: Extended-spectrum penicillins...

Extended-spectrum penicillins

Three interesting combination extended-spectrum penicillins are used widely in our specialty. They are ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and piperacillin/tazobactam. Ampicillin/sulbactam may be administered intramuscularly and intravenously. Piperacillin/tazobactam is administered intravenously; amoxicillin/clavulanate is administered orally.

Clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam are β-lactamase inhibitors. When added to the parent antibiotic (amoxicillin, ampicillin, and piperacillin, respectively), they significantly enhance the parent drug’s spectrum of activity. These agents interfere with bacterial cell wall synthesis. They provide excellent coverage of aerobic gram-positive cocci, including enterococci; anaerobic gram-positive cocci; anaerobic gram-negative bacilli; and aerobic gram-negative bacilli. Their principal adverse effects include allergic reactions and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. They are moderately expensive.

The principal application of ampicillin/sulbactam and piperacillin/tazobactam in our specialty is as single agents for treatment of puerperal endometritis, postoperative pelvic cellulitis, and pyelonephritis. The usual role for amoxicillin/clavulanate is for oral treatment of complicated UTIs, including pyelonephritis in early pregnancy, and for outpatient therapy of mild to moderately severe endometritis following delivery or pregnancy termination.

Macrolides, monobactams, and additional antibiotics

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic that is in the same class as erythromycin and clindamycin. In our specialty, it has largely replaced erythromycin because of its more convenient dosage schedule and its better tolerability. It inhibits bacterial protein synthesis, and it is available in both an oral and intravenous formulation.

Azithromycin has an excellent spectrum of activity against the 3 major microorganisms that cause otitis media, sinusitis, and bronchitis: Streptococcus pneumoniae, H influenzae, and M catarrhalis. It also provides excellent coverage of Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and genital mycoplasmas; in high doses it provides modest coverage against gonorrhea.8 Unlike erythromycin, it has minimal GI toxicity and is usually very well tolerated by most patients. One unusual, but very important, adverse effect of the drug is prolongation of the Q-T interval.9

Azithromycin is now available in generic form and is relatively inexpensive. As a single agent, its principal applications in our specialty are for treatment of respiratory tract infections such as otitis media, sinusitis, and acute bronchitis and for treatment of chlamydia urethritis and endocervicitis.8,10 In combination with ampicillin, azithromycin is used as prophylaxis in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), and, in combination with cefazolin, it is used for prophylaxis in patients undergoing cesarean delivery.1,2,5

Aztreonam

Aztreonam is a monobactam antibiotic. Like the cephalosporins and penicillins, aztreonam inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. It may be administered intramuscularly and intravenously, and its principal spectrum of activity is against aerobic gram-negative bacilli, which is similar to the aminoglycosides’ spectrum.

Aztreonam’s most likely adverse effects include phlebitis at the injection site, allergy, GI upset, and diarrhea. The drug is moderately expensive. In our specialty, aztreonam could be used as a single agent, in lieu of an aminoglycoside, for treatment of pyelonephritis caused by an unusually resistant organism. It also could be used in combination with clindamycin or metronidazole plus ampicillin for treatment of polymicrobial infections, such as chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic cellulitis.1,2

Continue to: Clindamycin...

Clindamycin

A macrolide antibiotic, clindamycin exerts its antibacterial effect by interfering with bacterial protein synthesis. It can be administered orally and intravenously. Its key spectrum of activity in our specialty includes GBS, staphylococci, and anaerobes. However, clindamycin is not active against enterococci or aerobic gram-negative bacilli. GI upset and antibiotic-induced diarrhea are its principal adverse effects, and clindamycin is one of the most important causes of C difficile colitis. Although it is available in a generic formulation, this drug is still relatively expensive.

Clindamycin’s principal application in our specialty is for treating staphylococcal infections, such as wound infections and mastitis. It is particularly effective against MRSA infections. When used in combination with an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin, clindamycin provides excellent treatment for chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. In fact, for many years, the combination of clindamycin plus gentamicin has been considered the gold standard for the treatment of polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic pelvic infections.1,2

Doxycycline

Doxycycline, a tetracycline, exerts its antibacterial effect by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis. The drug targets a broad range of pelvic pathogens, including C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae, and it may be administered both orally and intravenously. Doxycycline’s principal adverse effects include headache, GI upset, and photosensitivity. By disrupting the normal bowel and vaginal flora, the drug also can cause diarrhea and vulvovaginal moniliasis. In addition, it can cause permanent discoloration of the teeth, and, for this reason, doxycycline should not be used in pregnant or lactating women or in young children.

Although doxycycline has been available in generic formulation for many years, it remains relatively expensive. As a single agent, its principal application in our specialty is for treatment of chlamydia infection. It may be used as prophylaxis for surgical procedures, such as hysterectomy and pregnancy terminations. In combination with an extended-spectrum cephalosporin, it also may be used to treat pelvic inflammatory disease.2,8,10

Metronidazole

Metronidazole, a nitroimidazole derivative, exerts its antibacterial effect by disrupting bacterial protein synthesis. The drug may be administered topically, orally, and intravenously. Its primary spectrum of activity is against anerobic microorganisms. It is also active against Giardia and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Metronidazole’s most common adverse effects are GI upset, a metallic taste in the mouth, and a disulfiram-like effect when taken with alcohol. The cost of oral and intravenous metronidazole is relatively low; ironically, the cost of topical metronidazole is relatively high. In our specialty, the principal applications of oral metronidazole are as a single agent for treatment of bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. When combined with ampicillin plus an aminoglycoside, intravenous metronidazole provides excellent coverage against the diverse anaerobic microorganisms that cause chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic cellulitis.1,2

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

This antibiotic combination (an antifolate and a sulfonamide) inhibits sequential steps in the synthesis of folic acid, an essential nutrient in bacterial metabolism. It is available in both an intravenous and oral formulation. TMP-SMX has a broad spectrum of activity against the aerobic gram-negative bacilli that cause UTIs in women. In addition, it provides excellent coverage against staphylococci, including MRSA; Pneumocystis jirovecii; and Toxoplasma gondii.

The medication’s principal toxicity is an allergic reaction. Some reactions are quite severe, such as the Stevens-Johnson syndrome. TMP-SMX is relatively inexpensive, particularly the oral formulation. The most common indications for TMP-SMX in our specialty are for treatment of UTIs, mastitis, and wound infections.1,2,11 In HIV-infected patients, the drug provides excellent prophylaxis against recurrent Pneumocystis and Toxoplasma infections. TMP-SMX should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been linked to several birth defects, including neural tube defects, heart defects, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia.12

Nitrofurantoin

Usually administered orally as nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals, nitrofurantoin exerts its antibacterial effect primarily by inhibiting protein synthesis. Its principal spectrum of activity is against the aerobic gram-negative bacilli, with the exception of Proteus species. Nitrofurantoin’s most common adverse effects are GI upset, headache, vertigo, drowsiness, and allergic reactions. The drug is relatively inexpensive.

Nitrofurantoin is an excellent agent for the treatment of lower UTIs.11 It is not well concentrated in the renal parenchyma or blood, however, so it should not be used to treat pyelonephritis. As a general rule, nitrofurantoin should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with eye, heart, and facial cleft defects in the fetus.12

Vancomycin

Vancomycin exerts its antibacterial effect by inhibiting cell wall synthesis. It may be administered both orally and intravenously, and it specifically targets aerobic gram-positive cocci, particularly methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Vancomycin’s most important adverse effects include GI upset, nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and severe allergic reactions, such as anaphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and exfoliative dermatitis (the “red man” syndrome). The drug is moderately expensive.13

In its oral formulation, vancomycin’s principal application in our discipline is for treating C difficile colitis. In its intravenous formulation, it is used primarily as a single agent for GBS prophylaxis in penicillin-allergic patients, and it is used in combination with other antibiotics, such as clindamycin plus gentamicin, for treating patients with deep-seated incisional (wound) infections.1,2,13,14 ●

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020: chapter 58.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetrics: making cost-effective choices. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:59-72.

- Wagenlehner FME, Cloutier DJ, Komirenko AS, et al; EPIC Study Group. Once-daily plazomicin for complicated urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:729-740.

- Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1539-1548.

- Duff P. Prevention of infection after cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:758-770.

- Hooper DC, Wolfson JS. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:384-394.

- Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019 381:2338-2351.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, et al. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1881-1890.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

- Duff P. UTIs in pregnancy: managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. OBG Manag. 2022;34(1):42-46.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, et al. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects prevalence study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:978985.

- Alvarez-Arango S, Ogunwole SM, Sequist TD, et al. Vancomycin infusion reaction—moving beyond “red man syndrome.” N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1283-1286.

- Finley TA, Duff P. Antibiotics for treatment of staphylococcal infections in the obstetric patient. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:790-803.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020: chapter 58.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetrics: making cost-effective choices. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:59-72.

- Wagenlehner FME, Cloutier DJ, Komirenko AS, et al; EPIC Study Group. Once-daily plazomicin for complicated urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:729-740.

- Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1539-1548.

- Duff P. Prevention of infection after cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:758-770.

- Hooper DC, Wolfson JS. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:384-394.

- Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019 381:2338-2351.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, et al. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1881-1890.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

- Duff P. UTIs in pregnancy: managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. OBG Manag. 2022;34(1):42-46.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, et al. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects prevalence study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:978985.

- Alvarez-Arango S, Ogunwole SM, Sequist TD, et al. Vancomycin infusion reaction—moving beyond “red man syndrome.” N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1283-1286.

- Finley TA, Duff P. Antibiotics for treatment of staphylococcal infections in the obstetric patient. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:790-803.

Can US “pattern recognition” of classic adnexal lesions reduce surgery, and even referrals for other imaging, in average-risk women?

Gupta A, Jha P, Baran TM, et al. Ovarian cancer detection in average-risk women: classic- versus nonclassic-appearing adnexal lesions at US. Radiology. 2022;212338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.212338.

Expert commentary

Gupta and colleagues conducted a multicenter, retrospective review of 970 adnexal lesions among 878 women—75% were premenopausal and 25% were postmenopausal.

Imaging details

The lesions were characterized by pattern recognition as “classic” (simple cysts, endometriomas, hemorrhagic cysts, or dermoids) or “nonclassic.” Out of 673 classic lesions, there were 4 malignancies (0.6%), of which 1 was an endometrioma and 3 were classified as simple cysts. However, out of 297 nonclassic lesions (multilocular, unilocular with solid areas or wall irregularity, or mostly solid), 32% (33/103) were malignant when vascularity was present, while 8% (16/184) were malignant when no intralesional vascularity was appreciated.

The authors pointed out that, especially because their study was retrospective, there was no standardization of scan technique or equipment employed. However, this point adds credibility to the “real world” nature of such imaging.

Other data corroborate findings

Other studies have looked at pattern recognition in efforts to optimize a conservative approach to benign masses and referral to oncology for suspected malignant masses, as described above. This was the main cornerstone of the International Consensus Conference,2 which also identified next steps for indeterminate masses, including evidence-based risk assessment algorithms and referral (to an expert imager or gynecologic oncologist). A multicenter trial in Europe3 found that ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. This occurred in a stepwise fashion with increasing accuracy directly related to the level of expertise. Shetty and colleagues4 found that pattern recognition performed better than the risk of malignancy index (sensitivities of 95% and 79%, respectively). ●

While the concept of pattern recognition for some “classic” benign ovarian masses has been around for some time, this is the first time a large United States–based study (albeit retrospective) has corroborated that when ultrasonography reveals a classic, or “almost certainly benign” finding, patients can be reassured that the lesion is benign, thereby avoiding extensive further workup. When a lesion is “nonclassic” in appearance and without any blood flow, further imaging with follow-up magnetic resonance imaging or repeat ultrasound could be considered. In women with a nonclassic lesion with blood flow, particularly in older women, referral to a gynecologic oncologic surgeon will help ensure expeditious treatment of possible ovarian cancer.

- Boll D, Geomini PM, Brölmann HA. The pre-operative assessment of the adnexal mass: the accuracy of clinical estimates versus clinical prediction rules. BJOG. 2003;110:519-523.

- Glanc P, Benacerraf B, Bourne T, et al. First International Consensus Report on adnexal masses: management recommendations. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-863. doi: 10.1002/jum.14197.

- Van Holsbeke C, Daemen A, Yazbek J, et al. Ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance and confidence when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69:160-168. doi: 10.1159/000265012.

- Shetty J, Reddy G, Pandey D. Role of sonographic grayscale pattern recognition in the diagnosis of adnexal masses. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:QC12-QC15. doi: 10.7860 /JCDR/2017/28533.10614.

Gupta A, Jha P, Baran TM, et al. Ovarian cancer detection in average-risk women: classic- versus nonclassic-appearing adnexal lesions at US. Radiology. 2022;212338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.212338.

Expert commentary

Gupta and colleagues conducted a multicenter, retrospective review of 970 adnexal lesions among 878 women—75% were premenopausal and 25% were postmenopausal.

Imaging details

The lesions were characterized by pattern recognition as “classic” (simple cysts, endometriomas, hemorrhagic cysts, or dermoids) or “nonclassic.” Out of 673 classic lesions, there were 4 malignancies (0.6%), of which 1 was an endometrioma and 3 were classified as simple cysts. However, out of 297 nonclassic lesions (multilocular, unilocular with solid areas or wall irregularity, or mostly solid), 32% (33/103) were malignant when vascularity was present, while 8% (16/184) were malignant when no intralesional vascularity was appreciated.

The authors pointed out that, especially because their study was retrospective, there was no standardization of scan technique or equipment employed. However, this point adds credibility to the “real world” nature of such imaging.

Other data corroborate findings

Other studies have looked at pattern recognition in efforts to optimize a conservative approach to benign masses and referral to oncology for suspected malignant masses, as described above. This was the main cornerstone of the International Consensus Conference,2 which also identified next steps for indeterminate masses, including evidence-based risk assessment algorithms and referral (to an expert imager or gynecologic oncologist). A multicenter trial in Europe3 found that ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. This occurred in a stepwise fashion with increasing accuracy directly related to the level of expertise. Shetty and colleagues4 found that pattern recognition performed better than the risk of malignancy index (sensitivities of 95% and 79%, respectively). ●

While the concept of pattern recognition for some “classic” benign ovarian masses has been around for some time, this is the first time a large United States–based study (albeit retrospective) has corroborated that when ultrasonography reveals a classic, or “almost certainly benign” finding, patients can be reassured that the lesion is benign, thereby avoiding extensive further workup. When a lesion is “nonclassic” in appearance and without any blood flow, further imaging with follow-up magnetic resonance imaging or repeat ultrasound could be considered. In women with a nonclassic lesion with blood flow, particularly in older women, referral to a gynecologic oncologic surgeon will help ensure expeditious treatment of possible ovarian cancer.

Gupta A, Jha P, Baran TM, et al. Ovarian cancer detection in average-risk women: classic- versus nonclassic-appearing adnexal lesions at US. Radiology. 2022;212338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.212338.

Expert commentary

Gupta and colleagues conducted a multicenter, retrospective review of 970 adnexal lesions among 878 women—75% were premenopausal and 25% were postmenopausal.

Imaging details

The lesions were characterized by pattern recognition as “classic” (simple cysts, endometriomas, hemorrhagic cysts, or dermoids) or “nonclassic.” Out of 673 classic lesions, there were 4 malignancies (0.6%), of which 1 was an endometrioma and 3 were classified as simple cysts. However, out of 297 nonclassic lesions (multilocular, unilocular with solid areas or wall irregularity, or mostly solid), 32% (33/103) were malignant when vascularity was present, while 8% (16/184) were malignant when no intralesional vascularity was appreciated.

The authors pointed out that, especially because their study was retrospective, there was no standardization of scan technique or equipment employed. However, this point adds credibility to the “real world” nature of such imaging.

Other data corroborate findings

Other studies have looked at pattern recognition in efforts to optimize a conservative approach to benign masses and referral to oncology for suspected malignant masses, as described above. This was the main cornerstone of the International Consensus Conference,2 which also identified next steps for indeterminate masses, including evidence-based risk assessment algorithms and referral (to an expert imager or gynecologic oncologist). A multicenter trial in Europe3 found that ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. This occurred in a stepwise fashion with increasing accuracy directly related to the level of expertise. Shetty and colleagues4 found that pattern recognition performed better than the risk of malignancy index (sensitivities of 95% and 79%, respectively). ●

While the concept of pattern recognition for some “classic” benign ovarian masses has been around for some time, this is the first time a large United States–based study (albeit retrospective) has corroborated that when ultrasonography reveals a classic, or “almost certainly benign” finding, patients can be reassured that the lesion is benign, thereby avoiding extensive further workup. When a lesion is “nonclassic” in appearance and without any blood flow, further imaging with follow-up magnetic resonance imaging or repeat ultrasound could be considered. In women with a nonclassic lesion with blood flow, particularly in older women, referral to a gynecologic oncologic surgeon will help ensure expeditious treatment of possible ovarian cancer.

- Boll D, Geomini PM, Brölmann HA. The pre-operative assessment of the adnexal mass: the accuracy of clinical estimates versus clinical prediction rules. BJOG. 2003;110:519-523.

- Glanc P, Benacerraf B, Bourne T, et al. First International Consensus Report on adnexal masses: management recommendations. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-863. doi: 10.1002/jum.14197.

- Van Holsbeke C, Daemen A, Yazbek J, et al. Ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance and confidence when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69:160-168. doi: 10.1159/000265012.

- Shetty J, Reddy G, Pandey D. Role of sonographic grayscale pattern recognition in the diagnosis of adnexal masses. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:QC12-QC15. doi: 10.7860 /JCDR/2017/28533.10614.

- Boll D, Geomini PM, Brölmann HA. The pre-operative assessment of the adnexal mass: the accuracy of clinical estimates versus clinical prediction rules. BJOG. 2003;110:519-523.

- Glanc P, Benacerraf B, Bourne T, et al. First International Consensus Report on adnexal masses: management recommendations. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-863. doi: 10.1002/jum.14197.

- Van Holsbeke C, Daemen A, Yazbek J, et al. Ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance and confidence when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69:160-168. doi: 10.1159/000265012.

- Shetty J, Reddy G, Pandey D. Role of sonographic grayscale pattern recognition in the diagnosis of adnexal masses. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:QC12-QC15. doi: 10.7860 /JCDR/2017/28533.10614.

Optimize detection and treatment of iron deficiency in pregnancy

During pregnancy, anemia and iron deficiency are prevalent because the fetus depletes maternal iron stores. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia are not synonymous. Effective screening for iron deficiency in the first trimester of pregnancy requires the measurement of a sensitive and specific biomarker of iron deficiency, such as ferritin. Limiting the measurement of ferritin to the subset of patients with anemia will result in missing many cases of iron deficiency. By the time iron deficiency causes anemia, a severe deficiency is present. Detecting iron deficiency in pregnancy and promptly treating the deficiency will reduce the number of women with anemia in the third trimester and at birth.

Diagnosis of anemia